Abstract

This study aimed to evaluate the association between neutrophil percentage-to-albumin ratio (NPAR) and both all-cause and cardiovascular disease (CVD) mortality in patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD). Data from 7854 CKD patients aged ≥ 20 years were analyzed using the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) data from 2001 to 2018. Weighted Cox proportional hazards models, subgroup analyses, smoothed curve fitting, and Kaplan–Meier survival curves were employed to examine the association between NPAR and mortality risk. Additionally, Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves were used to compare NPAR’s predictive performance against traditional inflammatory markers. During a median follow-up of 79 months, there were 2795 all-cause deaths and 1019 CVD deaths. A U-shaped association was identified between NPAR and all-cause mortality, with an inflection point at NPAR = 12. Below this threshold, higher NPAR was associated with lower mortality risk (HR: 0.94, 95% CI 0.90–0.99); above it, increased NPAR corresponded to higher risk (HR: 1.14, 95% CI 1.12–1.16). Additionally, NPAR exhibited a positive association with CVD mortality (HR: 1.08, 95% CI 1.04–1.12). Compared to the lowest quartile, the highest NPAR quartile demonstrated significantly increased risks of all-cause mortality (HR: 2.24, 95% CI 1.88–2.66) and CVD mortality (HR: 1.91, 95% CI 1.42–2.58). ROC curve analysis demonstrated NPAR’s superior predictive capability compared to traditional inflammatory markers. NPAR exhibits significant associations with mortality outcomes in patients with CKD and surpasses traditional inflammatory markers in predicting mortality risk, highlighting its potential clinical value as a simple and cost-effective prognostic indicator.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) has become a significant global public health concern, affecting over 850 million people worldwide as of 20211. Despite progress in medical treatments, individuals with CKD still endure substantially higher risks of all-cause and cardiovascular mortality2,3,4,5. In global mortality rankings, CKD ascended from the 19th leading cause of death in 1990 to the 11th in 20191. Consequently, the early identification and management of prognostic risk factors are essential to slowing CKD progression and decreasing mortality rates.

Inflammation is highly prevalent among patients with CKD and plays a critical role in both the development and progression of the disease. This inflammatory state can be attributed to various factors, including heightened production of pro-inflammatory cytokines, oxidative stress, acidosis, chronic infections, altered adipose tissue metabolism, and intestinal dysbiosis6,7. The neutrophil percentage-to-albumin ratio (NPAR), a novel marker of systemic inflammation, has been shown to more accurately reflect the inflammatory state compared to traditional markers such as neutrophil percentage or the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR)8,9,10. Recent studies have linked NPAR with disease severity and prognosis in a range of pathological conditions. In cardiovascular diseases, elevated NPAR levels have been significantly associated with in-hospital mortality among patients with acute myocardial infarction11. Similarly, in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, NPAR has demonstrated predictive value for all-cause mortality12. Furthermore, in peritoneal dialysis patients, NPAR has been identified as an independent risk factor for poor outcomes13.

Various inflammatory markers have been extensively studied in CKD, including the systemic inflammatory response index (SIRI), NLR, and platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio (PLR)14,15. However, the prognostic value of NPAR, an emerging inflammatory marker, has not been fully elucidated in patients with CKD. To address this research gap, we analyzed data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) database to investigate the associations between NPAR and both all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in adults with CKD.

Materials and methods

Data source

This analysis utilized data from the NHANES collected between 2001 and 2018. NHANES is a major research program conducted by the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS), operating under the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Using a complex, multistage probability sampling design, this ongoing program gathers comprehensive health data from the non-institutionalized civilian U.S. population. The survey comprises detailed in-home interviews and standardized physical examinations, complemented by laboratory tests conducted at dedicated mobile examination centers (MECs). The NCHS Research Ethics Review Board approved all study procedures, and participants provided written informed consent before data collection. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki principles. Since this analysis used publicly available de-identified data, additional Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval was not necessary. Detailed NHANES methodology and datasets are accessible through the official NHANES website (https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes).

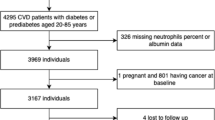

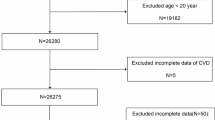

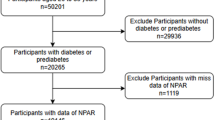

Study population

From the NHANES 2001–2018 cycles, we initially identified 91,351 participants. After excluding participants younger than 20 years (n = 41,150), 50,201 adult participants remained. Among these, we excluded participants without CKD or with indeterminate CKD status (n = 41,817), yielding 8,384 participants with confirmed CKD. Subsequently, we excluded pregnant participants (n = 70), those with missing follow-up data (n = 8), and participants lacking NPAR data (n = 452). The final analytical cohort comprised 7,854 participants (Fig. 1).

Definition of CKD

CKD was defined by either of the following criteria16,17,18,19,20: (a) an estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) of less than 60 mL/min/1.73 m2 or (b) an albumin-to-creatinine ratio (ACR) exceeding 30 mg/g. The eGFR was calculated using the Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration (CKD-EPI) equation21: GFR = 141 × min(Scr/k,1)α × max(Scr/k,1)−1.209 × 0.993Age × 1.018 [if female] × 1.159 [if black], where Scr represents serum creatinine (mg/dL), k is 0.7 for females and 0.9 for males, α is -0.329 for females and -0.411 for males, min refers to the smaller value between Scr/k and 1, while max refers to the larger value between Scr/k and 1. The ACR (mg/g) was calculated by dividing urinary albumin (mg/dL) by urine creatinine (g/dL)22.

Exposure variable

White blood cell counts were determined using an automated hematology analyzer (Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA, USA), while the neutrophil percentage was measured using the Coulter VCS system, a reliable method for differential white blood cell analysis. The NPAR was calculated as follows: NPAR = Neutrophil percentage (%) × 100/Albumin (g/dL).

Outcome measures

Mortality data were obtained by linking the NHANES cohort with the National Death Index (NDI) database (https://ftp.cdc.gov/pub/Health_Statistics/NCHS/datalinkage/linked_mortality/). All-cause mortality was defined as death from any documented cause. Cardiovascular disease (CVD) mortality was defined as deaths attributed to cardiovascular or cerebrovascular conditions, identified using the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision (ICD-10) codes. The specific codes used for CVD mortality included I00-I09, I11, I13, I20-I51, and I60-I69. The follow-up period extended from the initial participation date until either the date of death or December 31, 2019, which marked the most recent update of the NDI database.

Covariates

Covariates were selected based on a change in the effect estimate exceeding 10% and guidance from prior literature14,23,24. The selected covariates included age, gender, race, education level, poverty-to-income ratio (PIR), marital status, body mass index (BMI), smoking status, alcohol consumption, hypertension, diabetes, fasting blood glucose (FBG), glycated hemoglobin (HbA1C), aspartate transaminase (AST), alanine transaminase (ALT), total cholesterol, triglycerides, history of CVD, and self-reported history of dialysis in the past 12 months.

Age was recorded in years and categorized into three groups25: 20–40 years, 40–60 years, and ≥ 60 years. Race was classified into five categories: Mexican American, Other Hispanic, Non-Hispanic White, Non-Hispanic Black, and Other Race. Education level was divided into three groups: less than high school, high school or equivalent, and college or above. Marital status was grouped into two categories: “married or living with a partner” and “unmarried”, with the latter including individuals who were never married, separated, divorced, or widowed. BMI was calculated as weight divided by height squared (kg/m2) and categorized into thin (< 18.0 kg/m2), normal weight (18–25.0 kg/m2), overweight (25.0–30.0 kg/m2), and obesity (≥ 30.0 kg/m2). PIR was classified into low (PIR < 1.3), medium (PIR 1.3–3.5), and high (PIR ≥ 3.5). Smoking status was categorized into never smokers (fewer than 100 cigarettes in a lifetime), former smokers (more than 100 cigarettes but had quit), and current smokers (over 100 cigarettes and currently smoking)26. Alcohol consumption was divided into four groups based on the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) guidelines: none, moderate (≤ 1 drink/day for women, 1–2 drinks/day for men), heavy (2–3 drinks/day for women, 3–4 drinks/day for men), and binge (≥ 4 drinks/day for women, ≥ 5 drinks/day for men). Hypertension was identified through self-reported high blood pressure, use of antihypertensive medications, or measured blood pressure readings of systolic BP ≥ 140 mmHg and/or diastolic BP ≥ 90 mmHg. Diabetes was determined by self-reported diagnosis, diabetes medication use, insulin therapy, FBG ≥ 7.0 mmol/L, or HbA1C ≥ 6.5%27,28. Participants were classified as having CVD if they reported a history of congestive heart failure, coronary heart disease, angina pectoris, heart attack, or stroke.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed in accordance with the NHANES analytical guidelines29, incorporating sampling weights, stratification, and clustering to account for the complex, multi-stage, and stratified sampling design, thereby ensuring nationally representative estimates. Study participants were categorized into quartiles based on NPAR values. Survey-weighted linear regression was used to compare continuous variables among groups, with results presented as weighted means ± standard errors (SE). Categorical variables were analyzed using chi-square tests and expressed as unweighted frequencies with corresponding percentages.

Weighted Cox proportional hazards regression models were used to evaluate the association of NPAR with all-cause and CVD mortality. Hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated to quantify the strength of these associations. Three models were constructed to account for potential confounders. Model 1 was unadjusted and served as the crude model. Model 2 was adjusted for age, gender, and race. Model 3, the fully adjusted model, included adjustments for age, gender, race, education level, poverty-income ratio (PIR), marital status, BMI, smoking status, alcohol consumption, hypertension, diabetes, AST, ALT, total cholesterol, and triglycerides. Subgroup analyses were conducted to assess the consistency of the associations between NPAR and mortality outcomes across various subgroups, using the same weighted Cox regression model with full adjustment (Model 3). Interaction analyses were performed to determine whether the associations between NPAR and mortality risk varied across subgroup variables, with statistical significance evaluated by interaction P-values. Fully adjusted smoothed curve fitting was performed to explore potential non-linear associations between NPAR and both all-cause and CVD mortality, with threshold effect analyses conducted to identify potential inflection points in these associations. Kaplan–Meier survival curves were generated to compare survival probabilities among different NPAR quartiles for both all-cause and CVD mortality, with differences assessed using the log-rank test. Time-dependent receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves were constructed to evaluate and compare the predictive performance of different inflammatory markers, including NPAR, systemic immune-inflammation index (SII), NLR, PLR, and lymphocyte-to-monocyte ratio (LMR), for both all-cause and CVD mortality. The area under the ROC curve (AUC) was calculated to assess the discriminative ability of each marker.

In the main analysis, subjects with missing values were excluded (complete-case analysis). To ensure the robustness of the results, a sensitivity analysis was performed to address missing data. For categorical variables, missing values were coded as a separate category to retain them in the analysis. For continuous variables, where missing data accounted for less than 1% of the dataset, missing values were imputed using the median. The sensitivity analysis revealed no significant differences between the results derived from the pre-imputation and post-imputation datasets, confirming the reliability of the findings.

All statistical analyses were performed utilizing Empower Stats (http://www.empowerstats.com, X&Y Solutions, Inc, CA, USA) and R software (version 4.4.0; https://www.R-project.org), a two-tailed p value under 0.05 was regarded as statistically significant.

Results

Characteristics of the participants

The study population comprised 7,854 participants, who were stratified into four quartiles based on NPAR values (Q1: 0.2–12.9, Q2: 12.9–14.7, Q3: 14.7–16.4, Q4: 16.4–59.7). The baseline demographic characteristics, clinical parameters, and laboratory measurements across NPAR quartiles are summarized in Table 1. Most variables demonstrated significant differences across quartiles, with the exception of gender, education level, and dialysis status. Participants in the highest quartile (Q4) were characterized by older age, predominantly Non-Hispanic White ethnicity, and higher prevalence of obesity. A progressive increase in NPAR values was associated with a higher burden of chronic conditions, including hypertension, diabetes, and CVD. Renal function showed a consistent pattern of deterioration across quartiles, evidenced by declining eGFR and increasing ACR. Among metabolic parameters, higher NPAR quartiles were associated with elevated FBG and HbA1C levels, accompanied by reduced serum albumin and total cholesterol concentrations.

Association of NPAR with all-cause and CVD mortality

The median follow-up duration was 79 months. During this period, 2,795 all-cause deaths and 1,019 CVD deaths were recorded among the 7,854 participants. To investigate the association between NPAR and mortality outcomes, three progressive models were constructed, with results presented as HRs and 95% CIs in Table 2. In the fully adjusted model (Model 3), NPAR as a continuous variable was associated with a 12% higher risk of all-cause mortality for every unit increase (HR: 1.12, 95% CI 1.10–1.15, P < 0.001) and an 8% higher risk of CVD mortality (HR: 1.08, 95% CI 1.04–1.12, P < 0.001). When analyzed by quartiles, participants in the highest NPAR quartile (Q4) showed a 2.24-fold increased risk of all-cause mortality (HR: 2.24, 95% CI 1.88–2.66, P < 0.001) and a 1.91-fold increased risk of CVD mortality (HR: 1.91, 95% CI 1.42–2.58, P < 0.001) compared to those in the lowest quartile (Q1). Notably, the trends across NPAR quartiles were statistically significant (P for trend < 0.001). A sensitivity analysis conducted with the imputed dataset yielded similar associations between NPAR and all-cause mortality, as shown in Table S1.

To explore the potential nonlinear association between NPAR and mortality outcomes, we conducted smooth curve fitting analyses. As shown in Fig. 2, after full adjustment for confounding factors, the smooth curve fitting revealed distinct nonlinear associations of NPAR with both all-cause mortality (Fig. 2A) and CVD mortality (Fig. 2B). For all-cause mortality, the curve exhibited a U-shaped pattern, with mortality risk initially decreasing at lower NPAR values, followed by a progressive increase at higher levels. The association between NPAR and CVD mortality displayed a more complex pattern, characterized by a relatively gradual increase throughout the NPAR range. The two-piecewise Cox regression analysis identified a threshold effect in the association between NPAR and all-cause mortality, with an inflection point at NPAR = 12 (Table 3). Below this threshold (NPAR < 12), higher NPAR levels were associated with lower risk of all-cause mortality (HR: 0.94, 95% CI 0.90–0.99, P = 0.036), whereas above this threshold (NPAR > 12), higher NPAR values were linked to increased risks (HR: 1.14, 95% CI 1.12–1.16, P < 0.001). When reanalyzing the threshold effect of NPAR on all-cause mortality using imputed data, the findings remained qualitatively consistent (Table S2). For CVD mortality, given that the log likelihood ratio test was not significant (P = 0.064), a linear model was more appropriate, revealing a positive association between NPAR and CVD mortality (HR: 1.08, 95% CI 1.04–1.12, P < 0.001).

Smooth curves fitting. (A) The smooth curve fitting between NPAR and the probability of all-cause mortality. (B) The smooth curve fitting between NPAR and the probability of CVD mortality. The continuous red line indicates the smooth curve fitting the variables, while the blue dashed lines show the 95% confidence intervals from the fit. Adjusted for: age, gender, race, education level, PIR, marital status, BMI, smoking status, alcohol consumption, hypertension, diabetes, AST, ALT, total cholesterol, and triglycerides. Abbreviations: NPAR: neutrophil percentage-to-albumin ratio; CVD: cardiovascular disease; HR: hazard ratio; CI confidence interval; PIR: poverty-income ratio; AST: aspartate transaminase; ALT: alanine transaminase.

To visualize the mortality risk across different NPAR levels over time, Kaplan–Meier survival analyses were performed (Fig. 3). For all-cause mortality (Fig. 3A), individuals in the highest quartile (Q4) exhibited the poorest survival outcomes compared to those in lower quartiles, with a statistically significant difference (log-rank P < 0.001). A similar trend was observed for CVD mortality (Fig. 3B), where higher NPAR levels were associated with a marked decline in survival over the follow-up period (log-rank P < 0.001).

Subgroup analysis and interaction analysis

For subgroup analyses, we employed three BMI categories (< 25.0, 25.0–30.0, ≥ 30.0 kg/m2) rather than four because the thin group (BMI < 18.0 kg/m2) constituted fewer than 2% of participants in each NPAR quartile, restricting statistical power for meaningful comparisons. Subgroup and interaction analyses were conducted using the fully adjusted model (Model 3) to evaluate the robustness of the association between NPAR and mortality in various populations (Fig. 4). For all-cause mortality (Fig. 4A), the association between NPAR and mortality risk was consistent across most subgroups, with no significant interactions observed for gender, BMI, PIR, hypertension, smoking status, or alcohol consumption (P for interaction > 0.05). However, significant interactions were identified for age (P for interaction = 0.035) and diabetes (P for interaction = 0.001), where the mortality risk associated with NPAR appeared more pronounced among individuals aged ≥ 40 years and those with diabetes. In the case of CVD mortality (Fig. 4B), the association remained robust across subgroups, and no significant interactions were detected across examined variables (P for interaction > 0.05). It is noteworthy that in individuals younger than 40 years, the HR could not be accurately estimated due to the limited number of events.

Forest plots of subgroup analysis. (A) Subgroup analysis for the association between NPAR and all-cause mortality. (B) Subgroup analysis for the association between NPAR and CVD mortality. Age, gender, race, education level, PIR, marital status, BMI, smoking status, alcohol consumption, hypertension, diabetes, AST, ALT, total cholesterol, and triglycerides were all adjusted except the stratification variable.

ROC analysis of the predictive value of inflammatory markers for all‑cause and CVD mortality in CKD patients

Time-dependent ROC curve analyses were conducted to assess the predictive performance of various inflammatory markers, including NPAR, SII, NLR, PLR, and LMR, for mortality outcomes in CKD patients (Fig. 5). For all-cause mortality (Fig. 5A), NPAR exhibited the highest discriminative ability (AUC = 0.602), followed by NLR (AUC = 0.598), while the other markers demonstrated lower predictive capabilities (SII: AUC = 0.533, PLR: AUC = 0.518, LMR: AUC = 0.350). Similarly, for CVD mortality (Fig. 5B), NPAR maintained superior performance (AUC = 0.568) compared to NLR (AUC = 0.551), SII (AUC = 0.505), PLR (AUC = 0.518), and LMR (AUC = 0.437). These findings indicate that NPAR outperforms other inflammatory markers in predicting both all-cause and CVD mortality among CKD patients.

The time-dependent ROC curves for evaluating the predictive performance of NPAR, SII, NLR, PLR, and LMR in CKD patients. (A) ROC curves for predicting all-cause mortality. (B) ROC curves for predicting CVD mortality. Abbreviations: ROC: receiver operating characteristic; SII: systemic immune-inflammation index; NLR: neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio; PLR: platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio; LMR: lymphocyte-to-monocyte ratio.

Discussion

This study examined the association between NPAR and prognosis in CKD patients using data from the NHANES database (2001–2018). In this large cohort of 7,854 CKD patients with a median follow-up of 79 months and comprehensive mortality documentation, a U-shaped association was observed between NPAR and all-cause mortality after full adjustment for confounders. Specifically, when NPAR was below 12, higher NPAR levels were associated with lower risk of all-cause mortality, whereas above this threshold, higher NPAR values were linked to increased mortality risk. For cardiovascular outcomes, each unit increase in NPAR was associated with an 8% higher risk of cardiovascular mortality. Compared to the lowest quartile, patients in the highest NPAR quartile exhibited a 2.24-fold increased risk of all-cause mortality and a 1.91-fold increased risk of cardiovascular mortality. Importantly, NPAR demonstrated superior predictive capability for all-cause and CVD mortality in CKD patients when compared to traditional inflammatory markers.

Our findings align with several previous studies that have confirmed a significant association between inflammatory indicators and prognosis in CKD patients. Chen et al15. in a large-scale prospective study (n = 6,880) based on the NHANES database (1999–2018), demonstrated that multiple inflammatory indicators, including SII, NLR, PLR, and LMR, were significantly associated with all-cause mortality risk in CKD patients. Similarly, Lai et al30. through a multicenter longitudinal study conducted across five Chinese tertiary hospitals, reported that elevated SII levels were significantly linked to an increased risk of all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in CKD patients. In comparison, our study incorporated more comprehensive clinical endpoints, not only examining all-cause mortality but also assessing key prognostic indicators such as cardiovascular events, thereby offering a broader prognostic evaluation. Moreover, accumulating evidence highlights the crucial role of inflammation in the development and progression of CKD, influencing not only renal function but also being closely linked to the onset of CVD7,31,32,33. The inflammatory response exacerbates kidney damage through multiple pathways31,34,35,36,37, including the activation of inflammasomes, the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines, and interactions with oxidative stress, collectively contributing to a complex pathophysiological network.

Notably, our study was the first to systematically evaluate the predictive value of NPAR, a novel inflammatory indicator, in CKD patients. ROC curve analyses demonstrated that NPAR exhibited superior discriminative ability compared to other inflammatory markers (SII, NLR, PLR, and LMR), despite its overall predictive performance being modest (AUC = 0.602 for all-cause mortality and 0.568 for CVD mortality). This modest performance likely reflects the multifactorial nature of mortality risk in CKD patients, where factors beyond inflammation play a significant role. Despite modest AUC values, our analyses demonstrated significant clinical utility for NPAR through clearly defined thresholds. Our threshold effect analysis identified a critical inflection point at NPAR = 12, above which mortality risk markedly increased. This inflection point constitutes a potential screening parameter for initial risk stratification. Furthermore, our quartile analysis established a pronounced dose–response relationship, with NPAR values exceeding 14.7 (Q3 threshold) functioning as an intermediate reference for identifying high-risk CKD patients, while values above 16.4 (Q4 threshold) indicate substantially elevated risk necessitating intensified monitoring. The concordance between these analytical approaches reinforces the clinical validity of these proposed thresholds. Clinicians should interpret these values within the comprehensive clinical context and integrate them with established risk indicators. NPAR’s computational efficiency from standard hematological parameters enhances its implementation across diverse clinical settings, although further validation in varied populations would optimize these thresholds and establish whether NPAR-guided interventions improve outcomes in high-risk CKD patients.

Through smooth curve fitting and threshold effect analysis, our study identified a significant U-shaped association between NPAR and all-cause mortality risk, suggesting that both high and low NPAR levels are indicative of poor prognosis. The biological basis for this finding may be attributed to the fact that elevated NPAR reflects an excessive inflammatory response, which may accelerate organ dysfunction through mechanisms such as oxidative stress, endothelial dysfunction, and fibrosis8,31,38. Elevated NPAR levels correlate with increased mortality risk through harmful interactions between inflammation and hypoalbuminemia. The heightened neutrophil percentage indicates systemic inflammation severity, while hypoalbuminemia in CKD patients represents both malnutrition and persistent inflammatory conditions39. Inflammatory processes inhibit albumin synthesis, reducing serum levels, while diminished albumin further intensifies inflammatory damage through compromised antioxidant capacity40,41. This inflammation-hypoalbuminemia cycle substantially increases mortality risk. Conversely, low NPAR values present distinct pathophysiological challenges. Although reduced neutrophil percentages typically suggest lessened inflammatory burden, extremely low levels may signal compromised immune defenses, potentially increasing infection susceptibility42. This immune dysfunction, combined with CKD’s complex pathophysiology, helps explain why both NPAR extremes associate with unfavorable outcomes. However, the precise mechanism underlying this relationship warrants further basic research for clarification. Importantly, our study is the first to demonstrate that NPAR exhibits superior prognostic ability compared to traditional inflammatory indicators (e.g., SII, NLR, PLR, and LMR) in CKD patients. This advantage likely stems from NPAR’s unique biological characteristics. As a ratio of neutrophil percentage to albumin, NPAR not only reflects systemic inflammation43, but also incorporates albumin as an indicator of nutritional condition, providing a more comprehensive representation of the pathophysiological state in CKD patients. In contrast, other inflammatory markers primarily focus on the ratios between immune cells and may fail to adequately account for nutritional status, which is a critical prognostic factor. This combined assessment of inflammation and nutrition enables NPAR to more accurately predict prognosis in CKD patients.

The findings of our study hold significant clinical implications. Firstly, we validated NPAR as a simple, cost-effective, and readily available prognostic tool, derived from routinely measured parameters (neutrophil count and albumin) without incurring additional testing costs. Secondly, the discovery of a U-shaped association between NPAR and all-cause mortality risk offers valuable guidance for clinical practice, emphasizing the need for close monitoring of CKD patients with either high or low NPAR levels. The identified optimal threshold (NPAR = 12) provides an objective criterion for risk stratification, enabling clinicians to efficiently identify high-risk patients. Thirdly, NPAR exhibits superior prognostic capability compared to traditional inflammatory markers, largely due to its unique ability to reflect both inflammatory and nutritional status. This dual-role characteristic offers new perspectives for enhancing prognostic assessment in CKD patients. Looking forward, further prospective studies are necessary to validate the predictive value of NPAR, evaluate its role in clinical monitoring and intervention decision-making, and explore the feasibility of NPAR-guided individualized treatment strategies.

Nevertheless, several limitations of this study should be acknowledged. First, as an observational study based on the NHANES database, we could only establish associations between NPAR and mortality risk rather than causal relationships. Second, although multiple known confounders were adjusted for, unmeasured confounding factors may still have influenced our results. Third, NPAR levels were measured only once at baseline, which does not capture the dynamic changes of this indicator over time. Fourth, data availability limitations in the NHANES database prevented us from comparing NPAR with conventional inflammatory markers such as CRP, ESR, and ferritin. CRP measurements were absent from the 2011–2014 cycles, ESR was not assessed during our study timeframe, and ferritin data contained substantial demographic limitations. This constraint hindered direct comparisons between NPAR and these established inflammatory indicators, which would have provided valuable clinical context for our findings. Fifth, since the NHANES database represents only the non-institutionalized U.S. population, caution is warranted when generalizing our findings to other ethnic groups and populations. Therefore, additional research is warranted, specifically: (1) longitudinal investigations with sequential NPAR measurements to monitor its temporal evolution; and (2) multinational validation studies evaluating whether NPAR-guided therapeutic strategies targeting inflammatory processes and nutritional parameters can enhance clinical outcomes across diverse CKD populations. These strategic approaches would address the principal limitations identified in our current analysis while advancing the clinical utility of NPAR assessment.

Conclusion

Our study revealed a significant non-linear association between NPAR and all-cause mortality risk, as well as a positive association with CVD mortality risk in CKD patients. As a simple and cost-effective indicator, NPAR demonstrated superior predictive performance compared to traditional inflammatory markers for mortality in CKD patients, offering a valuable reference for clinical risk stratification and individualized treatment decisions. We recommend clinicians incorporate NPAR into standard CKD evaluation protocols to identify high-risk patients who warrant intensified surveillance and early therapeutic intervention.

Data availability

All data used in this study are publicly available through the official NHANES website (https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes).

Abbreviations

- NPAR:

-

Neutrophil percentage-to-albumin ratio

- CVD:

-

Cardiovascular disease

- CKD:

-

Chronic kidney disease

- NHANES:

-

National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey

- eGFR:

-

Estimated glomerular filtration rate

- ACR:

-

Albumin-to-creatinine ratio

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- PIR:

-

Poverty-to-income ratio

- FBG:

-

Fasting blood glucose

- HbA1C:

-

Glycated hemoglobin

- AST:

-

Aspartate transaminase

- ALT:

-

Alanine transaminase

- SII:

-

Systemic immune-inflammation index

- NLR:

-

Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio

- PLR:

-

Platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio

- LMR:

-

Lymphocyte-to-monocyte ratio

- ROC:

-

Receiver operating characteristic

- AUC:

-

Area under the ROC curve

- SE:

-

Standard error

- HR:

-

Hazard ratio

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

References

KDIGO 2024 Clinical Practice Guideline for the Evaluation and Management of Chronic Kidney Disease. Kidney Int. 105, S117-s314 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.kint.2023.10.018

Ladhani, M., Craig, J. C., Irving, M., Clayton, P. A. & Wong, G. Obesity and the risk of cardiovascular and all-cause mortality in chronic kidney disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Nephrol. Dial Transpl. 32, 439–449. https://doi.org/10.1093/ndt/gfw075 (2017).

Jankowski, J., Floege, J., Fliser, D., Böhm, M. & Marx, N. Cardiovascular disease in chronic kidney disease: Pathophysiological insights and therapeutic options. Circulation 143, 1157–1172. https://doi.org/10.1161/circulationaha.120.050686 (2021).

Li, X. & Lindholm, B. Cardiovascular risk prediction in chronic kidney disease. Am. J. Nephrol. 53, 730–739. https://doi.org/10.1159/000528560 (2022).

Lim, Y. J., Sidor, N. A., Tonial, N. C., Che, A. & Urquhart, B. L. Uremic toxins in the progression of chronic kidney disease and cardiovascular disease: mechanisms and therapeutic targets. Toxins Basel https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins13020142 (2021).

Zhao, X., Wang, T. & Zhou, L. Dose-response analysis of systemic immune-inflammation index and risk of chronic kidney disease. Int. J. Surg. 110, 1843–1845. https://doi.org/10.1097/js9.0000000000001007 (2024).

Mihai, S. et al. Inflammation-related mechanisms in chronic kidney disease prediction, progression, and outcome. J. Immunol. Res. 2018, 2180373. https://doi.org/10.1155/2018/2180373 (2018).

Kurkiewicz, K., Gąsior, M. & Szyguła-Jurkiewicz, B. E. Markers of malnutrition, inflammation, and tissue remodeling are associated with 1-year outcomes in patients with advanced heart failure. Pol. Arch. Intern. Med. https://doi.org/10.20452/pamw.16411 (2023).

Liu, C. F. & Chien, L. W. Predictive role of neutrophil-percentage-to-albumin ratio (NPAR) in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and advanced liver fibrosis in nondiabetic US adults: Evidence from NHANES 2017–2018. Nutrients https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15081892 (2023).

Hu, Z. et al. The neutrophil-to-albumin ratio as a new predictor of all-cause mortality in patients with heart failure. J. Inflamm. Res. 15, 701–713. https://doi.org/10.2147/jir.S349996 (2022).

Cui, H., Ding, X., Li, W., Chen, H. & Li, H. The neutrophil percentage to albumin ratio as a new predictor of in-hospital mortality in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. Med. Sci. Monit. 25, 7845–7852. https://doi.org/10.12659/msm.917987 (2019).

Lan, C. C., Su, W. L., Yang, M. C., Chen, S. Y. & Wu, Y. K. Predictive role of neutrophil-percentage-to-albumin, neutrophil-to-lymphocyte and eosinophil-to-lymphocyte ratios for mortality in patients with COPD: Evidence from NHANES 2011–2018. Respirology 28, 1136–1146. https://doi.org/10.1111/resp.14589 (2023).

Xu, M., Huan, J., Zhu, L., Xu, J. & Song, K. The neutrophil percentage-to-albumin ratio is an independent risk factor for poor prognosis in peritoneal dialysis patients. Ren. Fail. 46, 2294149. https://doi.org/10.1080/0886022x.2023.2294149 (2024).

Gu, L. et al. Systemic Inflammatory Response Index (SIRI) is associated with all-cause mortality and cardiovascular mortality in population with chronic kidney disease: evidence from NHANES (2001–2018). Front. Immunol. 15, 1338025. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2024.1338025 (2024).

Chen, Y. et al. Association between systemic inflammatory indicators with the survival of chronic kidney disease: A prospective study based on NHANES. Front. Immunol. 15, 1365591. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2024.1365591 (2024).

Webster, A. C., Nagler, E. V., Morton, R. L. & Masson, P. Chronic kidney disease. Lancet 389, 1238–1252. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(16)32064-5 (2017).

Chen, T. K., Knicely, D. H. & Grams, M. E. Chronic kidney disease diagnosis and management: A review. JAMA 322, 1294–1304. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2019.14745 (2019).

Matsushita, K. et al. Epidemiology and risk of cardiovascular disease in populations with chronic kidney disease. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 18, 696–707. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41581-022-00616-6 (2022).

KDIGO 2021 Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Glomerular Diseases. Kidney Int. 100, S1–s276 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.kint.2021.05.021

KDIGO 2017 Clinical Practice Guideline Update for the Diagnosis, Evaluation, Prevention, and Treatment of Chronic Kidney Disease-Mineral and Bone Disorder (CKD-MBD). Kidney Int. Suppl. (2011) 7, 1–59 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.kisu.2017.04.001

Levey, A. S. et al. A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Ann. Intern. Med. 150, 604–612. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-150-9-200905050-00006 (2009).

Murphy, D. et al. Trends in prevalence of chronic kidney disease in the United States. Ann. Intern. Med. 165, 473–481. https://doi.org/10.7326/m16-0273 (2016).

Yan, L. J., Zhang, F. R., Ma, C. S. & Zheng, Y. Higher dietary inflammatory index is associated with increased all-cause mortality in adults with chronic kidney disease. Front. Nutr. 9, 883838. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnut.2022.883838 (2022).

Guo, M. et al. Association between dietary inflammatory index and chronic kidney disease in middle-aged and elderly populations. Front. Nutr. 11, 1335074. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnut.2024.1335074 (2024).

Kang, H., Lee, J. P. & Choi, K. Exposure to phthalates and environmental phenols in association with chronic kidney disease (CKD) among the general US population participating in multi-cycle NHANES (2005–2016). Sci. Total Environ. 791, 148343. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.148343 (2021).

Kanagasabai, T. & Ardern, C. I. Contribution of inflammation, oxidative stress, and antioxidants to the relationship between sleep duration and cardiometabolic health. Sleep 38, 1905–1912. https://doi.org/10.5665/sleep.5238 (2015).

Kemppainen, S. M., Fernandes Silva, L., Lankinen, M. A., Schwab, U. & Laakso, M. Metabolite signature of physical activity and the risk of type 2 diabetes in 7271 men. Metabolites https://doi.org/10.3390/metabo12010069 (2022).

Qiu, Z. et al. Associations of serum carotenoids with risk of cardiovascular mortality among individuals with type 2 diabetes: results from NHANES. Diabetes Care 45, 1453–1461. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc21-2371 (2022).

Johnson, C. L. et al. National health and nutrition examination survey: Analytic guidelines, 1999–2010. Vital. Health Stat. 2, 1–24 (2013).

Lai, W. et al. Elevated systemic immune inflammation level increases the risk of total and cause-specific mortality among patients with chronic kidney disease: a large multi-center longitudinal study. Inflamm. Res. 72, 149–158. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00011-022-01659-y (2023).

Stenvinkel, P. et al. Chronic inflammation in chronic kidney disease progression: Role of Nrf2. Kidney Int. Rep. 6, 1775–1787. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ekir.2021.04.023 (2021).

Fu, Y., Xiang, Y., Li, H., Chen, A. & Dong, Z. Inflammation in kidney repair: Mechanism and therapeutic potential. Pharmacol. Ther. 237, 108240. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pharmthera.2022.108240 (2022).

Li, H. et al. Causal effects of systemic inflammatory regulators on chronic kidney diseases and renal function: A bidirectional Mendelian randomization study. Front. Immunol. 14, 1229636. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2023.1229636 (2023).

Bruce, A. T. et al. Selected renal cells modulate disease progression in rodent models of chronic kidney disease via NF-κB and TGF-β1 pathways. Regen. Med. 10, 815–839. https://doi.org/10.2217/rme.15.43 (2015).

Schnaper, H. W. The tubulointerstitial pathophysiology of progressive kidney disease. Adv. Chronic Kidney Dis. 24, 107–116. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.ackd.2016.11.011 (2017).

Xiang, D. M. et al. Chronic kidney disease promotes chronic inflammation in visceral white adipose tissue. Am. J. Physiol. Ren. Physiol. 312, F689-f701. https://doi.org/10.1152/ajprenal.00584.2016 (2017).

Islamuddin, M. & Qin, X. Renal macrophages and NLRP3 inflammasomes in kidney diseases and therapeutics. Cell Death Discov. 10, 229. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41420-024-01996-3 (2024).

He, X., Dai, F., Zhang, X. & Pan, J. The neutrophil percentage-to-albumin ratio is related to the occurrence of diabetic retinopathy. J. Clin. Lab. Anal. 36, e24334. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcla.24334 (2022).

Alves, F. C. et al. The higher mortality associated with low serum albumin is dependent on systemic inflammation in end-stage kidney disease. PLoS ONE 13, e0190410. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0190410 (2018).

Biswas, S. K. Does the interdependence between oxidative stress and inflammation explain the antioxidant paradox?. Oxid. Med. Cell Longev. 2016, 5698931. https://doi.org/10.1155/2016/5698931 (2016).

Sitar, M. E., Aydin, S. & Cakatay, U. Human serum albumin and its relation with oxidative stress. Clin Lab 59, 945–952 (2013).

Kolaczkowska, E. & Kubes, P. Neutrophil recruitment and function in health and inflammation. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 13, 159–175. https://doi.org/10.1038/nri3399 (2013).

Sugimoto, M. A., Sousa, L. P., Pinho, V., Perretti, M. & Teixeira, M. M. Resolution of Inflammation: What Controls Its Onset?. Front. Immunol. 7, 160. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2016.00160 (2016).

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the research team at the National Center for Health Statistics of the CDC and extend our appreciation to all subjects who participated in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey.

Funding

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.L. and Y.G. wrote the main manuscript text. P.Y. conceived and supervised the study. All authors contributed to data analysis and interpretation.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This study analyzed data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) collected between 2001 and 2018. All NHANES protocols and procedures were approved by the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) Research Ethics Review Board, and the survey was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki principles. The NHANES program employs a complex, multistage probability sampling design to collect comprehensive health data from the non-institutionalized civilian U.S. population through detailed in-home interviews, standardized physical examinations, and laboratory tests conducted at mobile examination centers (MECs). All NHANES participants provided written informed consent before data collection. As this analysis utilized publicly available de-identified data from the NHANES database (https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes), additional Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval was not required for the current study.

Consent to participate

Written informed consent was obtained from all participants during the original NHANES data collection process. No additional consent was required for this secondary analysis of de-identified, publicly available data.

Consent for publication

Not applicable, as this study used anonymous, publicly available data with no individually identifiable information.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, M., Gou, Y. & Yang, P. Neutrophil percentage-to-albumin ratio is associated with all cause and cardiovascular disease mortality in chronic kidney disease based on NHANES 2001–2018. Sci Rep 15, 26546 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-12272-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-12272-4