Abstract

In continuous search for RANKL induced osteoclastogenesis inhibitors, twenty-six fungal isolates were obtained from ten Red Sea marine sponges collected from Egypt and the ethyl acetate fractions of their cultures’ methanol extracts were assessed in RAW264 macrophages. Active fractions were profiled via LC-MS/MS, followed by untargeted molecular networking, leading to the tentative identification of eight unreported compounds (1, A2, C1, C2, C4-C7), and thirteen known compounds. The two active fungi were identified and deposited in GenBank with accession numbers PQ423742 and PQ423748 for Aspergillus flavus and Cladosporium colombiae, respectively. Bioassay-guided isolation afforded two bisphenol diglycidic ethers, 1 and 2, and two diketopiperazines, 3 and 4 from A. flavus, while C. colombiae yielded cinnamic acid (5), two diketopiperazines (6 and 7), and altenuene (8). Structures were elucidated by NMR and mass spectroscopic analyses, which revealed 1 to be isolated for the first time from natural sources. Isolated compounds were biologically evaluated. Only 1 and 8 inhibited RANKL-induced formation of mature multinucleated osteoclasts with IC50 57.14 and 38.35 µM, respectively, without cytotoxicity against RAW264 macrophages. The ADMET properties for 1 and 8 were predicated using SwissADME and pkCMS platforms. 8 showed superior solubility and lower toxicity than compound 1.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Osteoporosis is a global health problem with high incidence among geriatric populations. This silent disease has high global preference, characterized by disturbance in osteoblast-osteoclast coupling mechanisms1,2. Osteoclastogenesis, the process by which osteoclasts are formed, is initiated when the monocyte/macrophage lineage is activated by receptor activator of nuclear factor-κB ligand (RANKL). Upon RANKL stimulation, downstream signaling pathways, including NF-κB and Mitogen-activated protein kinase are activated, leading to the upregulation of osteoclast-specific genes such as tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase (TRAP) and fusion-related enzymes. Dysregulation of osteoclast functions has been implicated in various diseases like osteoporosis and bone metastasis3. Overactivation of osteoclasts leads to excessive bone resorption, thereby reducing bone mineral density4. It is predicted that, by 2050 osteoporotic patients will be around 200 million worldwide and the economic toll will exceed 130 billion USD5. Therefore, global attention was directed to finding alternative sources for inhibiting osteoclastogenesis with potential therapeutic intervention6,7,8.

Fungal metabolites are structurally diverse and show wide spectrum of biological activities. Being easily cultivated, fungi are considered as renewable promising source to overcome the limitation of the short supply, that is a main concern in other natural resources such as plants and marine invertebrates. Aspergillus is a prolific fungal Genus able to produce a wide range of secondary metabolites. That includes alkaloids such as the antibacterial compounds pseurotin A, fumitremorgin C, and bisdethiobis(methylthio)gliotoxin, from A. terreus9antiosteoclastogenic glycosides such as taichunins J and K from A. taichungensis14peptides such as the antibacterial and cytotoxic malformin C from A. niger10polyketides such as calidiol A from A. californicus that exhibited moderate antibacterial activity against MRSA11and immunosuppressive steroids such as Aspersteroids from A. ustus12. These metabolites exhibit a broad spectrum of biological activities with significant medical, industrial, agricultural, and economic importance13. Aspergillus sp. metabolites have shown considerable biological activities against osteoclast hyperactivity such as taichunins with inhibitory activity on RANKL induced osteoclastogenesis14.

Fungal secondary metabolites possess diverse bioactivities and can modulate bone remodeling through multiple mechanisms, including antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and gene-targeting effects relevant to osteoclast differentiation and function6,15. Despite their therapeutic potential, few studies have systematically explored their role in regulating osteoclastogenesis. In this study, we employed murine RAW264 macrophages as a validated in vitro model to identify fungal-derived inhibitors of osteoclast differentiation. This strategic approach not only facilitates the discovery of new bioactive scaffolds but also addresses a critical unmet need for alternative osteoclast-targeted therapies capable of restoring bone homeostasis in osteoporosis and other bone-resorptive disorders, while avoiding the adverse effects of conventional treatments such as bone osteolysis of bisphosphonates16osteonecrosis of jaw, hypocalcemia and atypical femur fractures in case of denosumab17and cardiovascular, musculoskeletal adverse effects of parathyroid hormone (PTH) analogs, such as teriparatide and abaloparatide18. Meanwhile, SwissADME and pkCSM Web Servers were used for ADMET Evaluation of the active compounds for predicting their pharmacokinetic and safety profiles19.

Materials and methods

General experimental procedure

Optical rotations were recorded on JASCO DIP-1000 polarimeter in methanol (CH3OH)1. H- and 13C-NMR spectra were measured at field strengths 600 and 150 MHz, respectively, by Bruker Avance III 600 NMR spectrometer in deuterated chloroform-d (CDCl3) and methanol-d4 (CD3OD). Chemical shifts were referenced to the residual solvent peaks (δH 7.26 and δC 77.0, δH 3.31 and δC 49.0 for CDCl3 and CD3OD, respectively). Mass spectra were recorded on a Bruker ESI-ion trap amaZon speed system. MPLC was carried out by Biotage Isolera I system, equipped with a UV detector, while HPLC purifications were conducted on Waters 515 HPLC pump, connected to Waters 2489 UV/visible detector equipped with Pantos Unicorder U-228.

All solvents of extraction, fractionation, column chromatography, and MPLC were of analytical grade (Alpha Chemika, India), while solvents for LC-MS and HPLC purifications were of HPLC grade (Fischer, India). All salts for buffers, media constituents, and standard, as well as chemicals and solvents in the TRAP activity assay, were of fine grade (Sigma, Aldrich, India).

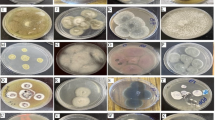

Isolation and identification of the endophytic fungal isolates

Samples of ten sponges (Table S1) were collected from Magawish Island at N 27.169714, E 33.833056 using SCUBA equipment at around 7 m depth, Red Sea, Egypt, and identified as previously reported20. The isolated fungi (Figure S1) were identified on the basis of their morphological features of fungal culture and hyphae (Figure S3). The identification of the two selected fungi, Aspergillus flavus (A. flavus) and Cladosporium colombiae (C. colombiae) isolated from Ircinia variabilis, and Hyrtios erectus, respectively (Figure S2), were confirmed by sequence analysis and data comparison from NCBI GenBank databases (Figure S4). These fungi were assigned the accession numbers PQ423742 for A. flavus and PQ423748 for C. colombiae21,22,23.

Fungal cultivation, extraction, and fractionation for screening purposes

The isolated fungi were cultured on biomalt-peptone agar medium (g/L) (biomalt 20, peptone 12.5, agar 20, seawater 50%), two plates/isolate. All cultures were incubated for 30 days at 28 °C. All solid media were extracted with CH3OH 100 mL/plate three successive times and filtered on Whatman filter paper No.1. Extracts were concentrated under vacuum at 40 °C and the resulting aqueous gummy residues were resuspended in water and partitioned with ethyl acetate (EtOAc). The obtained fractions were kept in dim light containers for further biological and chemical screening.

Evaluation of the antiosteoporosis activity

Cell culture and RANKL-induced osteoclastogenesis

EtOAc fractions of all fungal CH3OH extracts were tested for their ability to inhibit TRAP activity and the formation of multinucleated osteoclasts (MNCs) in RANKL-treated RAW264 macrophages as previously reported7,24. Briefly, RAW264 cells (RIKEN Cell Bank, Tsukuba) were cultured in MEMα medium supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum and 1% penicillin/streptomycin and incubated at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 humidified atmosphere in two 96-well plates at a density of 1000 and 6000 cells/well, for TRAP assay and MNCs staining assay, respectively. Samples were then added at a concentration of 50 and 20 µg/mL for extracts, 50, 20, and 10 µM for pure compounds, and 83 µM for the standard quercetin. Then, soluble RANKL (Santa Cruz, USA) was added at a concentration of 50 ng/mL to all wells except for negative control wells. Dimethyl sulfoxide was used as a vehicle in both negative and positive control wells.

TRAP activity assay

After four days, cells were washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and lysed with lysis buffer formed of 50 mM sodium tartrate, 50 mM sodium acetate, 150 mM potassium chloride, 0.1% Triton X-100, 1 mM sodium ascorbate, and 0.1 mM ferric chloride, pH 5.7; 100 µL/well on ice for 10 min. The resulting cell extract (20 µL) was added to 100 µL of TRAP buffer containing 2.5 mM p-nitrophenyl phosphate (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and incubated at 37 °C for 4 h. To stop the reaction, 50 µL of 0.9 M sodium hydroxide was added to the reaction mixture and the reaction product (p-nitrophenolate) was measured as the absorbance at 405 nm.

Multinucleated TRAP + ve osteoclast (MNCs) counting assay

Following a 4-day incubation period, the differentiated cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde solution (Sigma–Aldrich, USA), washed with PBS, and stained using a TRAP-staining solution, which consisted of 50 mM sodium tartrate, 45 mM sodium acetate, 0.1 mg/mL naphthol AS-MX phosphate (Sigma– Aldrich, USA), and 0.6 mg/mL fast red violet LB salt (Sigma–Aldrich, USA), pH 5.2, for 1 h or longer at room temperature. TRAP-positive cells, that stained red and contained 3 or more nuclei were determined to be multinuclear osteoclasts and were quantified in each well by counting MNCs in 8 fields/well using a light microscope8.

MTT cytotoxicity assay

After incubation of cells for one day, media was aspired and replaced with new one supplemented with treatments, whereas controls contained only DMSO. Cells were then kept at 37 °C for three days. Finally, 50 µL of 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)−2,diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) solution (150 µg/mL in medium) was added after aspiration of medium, incubated under the same conditions for 3 h. Then 200 µL of DMSO were added to each well, after removal of the reaction solution, to dissolve the formed formazan salt crystals, and optical density was measured at 570 nm with a microplate reader.

In all biological tests, experiments were performed in triplicates, results were expressed as mean ± standard deviation, and significant differences were set at p < 0.005 according to the Student’s t-test.

LC-MS/MS analysis and metabolic molecular network

LC-MS/MS conditions and parameters

To prepare the samples, 1 mg of each EtOAc fraction was dissolved in 1 mL of CH3OH (HPLC grade, Fisher, UK) and filtered through a 0.22 μm PTFE membrane (Sartorius, USA). The HPLC analysis was performed using a Shimadzu Prominence system, featuring LC-20AD pumps and an SPD-M20A DAD detector, coupled with a Bruker amaZon speed mass spectrometer. The system operated in both positive and negative ion modes within the same run. Background subtraction based on blank mobile phase run was carried out.

For each analysis, 1 µL of the prepared extract was injected into an InertSustain-C18 column (3.0 μm, 4.6 × 150 mm; GL Sciences, Japan). The elution was achieved using a gradient with two solvents: solvent A (100% water + 0.1% acetic acid) and solvent B (100% acetonitrile + 0.1% acetic acid). The gradient program was set as follows: starting with 10% B for the first minute, increasing linearly from 10 to 100% B over the next 14 min, at a flow rate of 0.4 mL/min.

The ESI source conditions included a capillary temperature of 320 °C, a source voltage of 3.5 kV, and a sheath gas flow rate of 11 L/min. Ion detection was conducted in full scan mode with range 100–2000 m/z, MS(n) ICC target and MS(n) maximum acquisition time were adjusted to 50,000 and 200 ms, respectively, with a threshold of 1000 counts and a scan rate of 6 scans per second25.

The MS/MS data were converted from Bruker’s “.d” files to mzML format using MSConvert, part of the ProteoWizard suite (https://www.proteowizard.org). The processed data were then uploaded to the Global Natural Products Social Molecular Networking (GNPS) platform for further analysis.

Molecular network

Molecular networks for two EtOAc fractions were created using the GNPS platform (http://gnps.ucsd.edu). In accordance with the default GNPS networking parameters, a mass tolerance of 0.2 Da was applied for precursor ions and 0.05 Da for fragment ions. For network creation, a minimum of six matching MS fragments between two consensus MS/MS spectra was required, and the similarity threshold (cosine score) for connecting nodes was set at 0.7. The resulting network was saved as a GraphML file and visualized using Cytoscape 3.7.1 software, employing a force-directed layout.

Large-scale culture and extraction

A. flavus and C. colombiae were selected based on bioassay results and cultured on biomalt-peptone agar medium (g/L) to fill 160 petri dishes (100 mm x 15 mm) for each fungus (25 mL medium/petri dish). After inoculation (30 days/28 °C), each fungal culture was extracted with CH3OH, filtrated, and concentrated under pressure (40 °C). The obtained residues were dissolved in water (H2O), partitioned with EtOAc to be concentrated using Rota evaporator, and afforded 580 and 586 mg of EtOAc fractions for A. flavus and C. colombiae, respectively.

Isolation of fungal metabolites

For A. flavus, EtOAc fraction (580 mg) was processed using MPLC (SNAP Ultra®, 10 g, Biotage Japan Ltd.) with a gradient system (0–10% CH3OH/CH2Cl2 for 8 column volumes, then, 10–100% CH3OH/CH2Cl2 for 5 column volumes, and finally washed with CH3OH for 5 column volumes at 36 mL/min) to produce six fractions (Frs. V1-V6). Fr. V5 (99.1 mg) underwent further separation using octadecylsilane (ODS) reverse-phase open column chromatography using gradient elution systems of CH3OH/H2O at 40%, 70%, and 100% resulting in six subfractions (Frs. X1-X6). Fr. X3 (16.1 mg) was subsequently purified by HPLC (Inertsil ODS-P column, 20 × 250 mm) with 70% CH3OH/water to isolate compounds 1 (4.5 mg) and 2 (1.3 mg). Fr. V2 (45.2 mg) was refined through preparative HPLC (Inertsil Diol, GL Sciences Inc., 20 × 250 mm) eluted with CH2Cl2/CH3OH 50:1 to obtain compounds 3 (11.5 mg) and 4 (4.6 mg).

EtOAc fraction of C. colombiae (586 mg) was manipulated by MPLC (SNAP Ultra®, 25 g, Biotage Japan Ltd.) with a gradient system (0–5% CH3OH/CH2Cl2 for 13 column volumes, then, 5-100% CH3OH/CH2Cl2 for 3.5 column volumes, and finally washed with CH3OH for 3.5 column volumes at 75 mL/min) to give six fractions (Frs. Y1-Y6). Fr. Y3 (8.88 mg) was purified via ODS HPLC (Inertsil ODS-P column, 20 × 250 mm) with 50% CH3OH/H2O to provide compounds 5 (9.9 mg), 6 (5.38 mg), and 7 (2.36 mg). Fr. Y5 (110.47 mg) was loaded to an ODS open column, eluted with 50% CH3OH/H2O then CH3OH, resulting in two subfractions (Frs. Z1 and Z2). Upon purification of Fr. Z1 (34.18 mg) by ODS HPLC (Inertsil ODS-P column, 20 × 250 mm) with 50% CH3OH/H2O, 8 (5.90 mg) was obtained.

Prediction of ADMET parameters

For active compounds, the physicochemical and drug-likeness characters were obtained using SwissADME web server (http://www.swissadme.ch/), while ADMET properties were predicated using pkCMS web server (http://biosig.unimelb.edu.au/pkcsm/prediction). These analyses provided insights into essential parameters in early drug development26.

Results and discussion

LC-MS/MS analysis and metabolic molecular network

Ten fungal species were isolated from ten Red Sea Egyptian marine sponges (Table S1, Figure S1). Their EtOAc fractions, obtained from the crude CH3OH extracts of corresponding cultures, were tested for their ability to inhibit the formation of osteoclasts from RANKL-treated RAW264 macrophages. The EtOAc fractions of two fungal isolate cultures significantly exhibited potent antiosteoporosis activity, as they completely inhibited the TRAP activity in RANKL-stimulated RAW264 cells at 50 µg/mL, with an IC50 of 24.83 µg/mL for Aspergillus flavus and 17.18 µg/mL for Cladosporium colombiae. Metabolomic profiles of the two bioactive fractions were monitored by LC-MS/MS analysis (Figure S5a, Table S2), followed by untargeted molecular networking for dereplication of the secondary metabolites within the chemical space of each extract (Fig. 1). This process resulted in the tentative identification of eighteen compounds, which are primarily classified as bisphenols, diketopiperazines (DKPs), and pyrrolidine alkaloids.

Bisphenols

The generated molecular networks of A. flavus extract (Fig. 1) revealed a distinct cluster (A) of bisphenol compounds characterized by a bisphenol diglycidic ether structure. In detail, the node at m/z 377.1 corresponds to 2,2-bis‐[4‐(2,3‐dihydroxy-propoxy)phenyl]propane (compound A1), exhibiting an MS/MS spectrum (Figure S5b) with a base peak at m/z 209 resulting from the characteristic loss of 168 amu, attributed to a glyceryl phenol moiety27. Similarly, compound 2 (m/z 391.1) shows a similar fragmentation pattern, featuring a neutral loss of 182 amu corresponding to a methyl glyceryl phenol moiety, resulting in a base peak at m/z 223, and was identified as 2‐[4‐(2-hydroxy-3‐methoxy-propoxy) phenyl]‐2‐[4‐(2,3-dihydroxy propoxy) phenyl] propane (Fig. 1, S5b). Consequently, compounds 1 (m/z 405.31) and A2 (m/z 450.53 as ammonia adduct) were determined to be 2,2‐bis‐[4‐(2‐hydroxy-3-methoxy-propoxy)phenyl]propane, and 2-[4-(2-hydroxy-3-methoxy-propoxy)phenyl]−2-[4-(2-hydroxy-3-propoxy-propoxy)phenyl]propane (Fig. 1, S5b).

Diketopiperazines (DKPs)

The fragmentation patterns of diketopiperazines (DKPs) (Table S2, Figure S5c) provide critical insights into their structural identification, particularly through the detection of specific ions such as m/z 120, corresponding to the phenylalanyl moiety, and m/z 136, corresponding to the tyrosyl moiety. By analyzing these ions alongside the m/z values and molecular formulas of the parent ions, the two amino acids constituting the DKP compounds can be deduced. For example, the parent ion with m/z 261.0 (C14H16N2O3, Rt 1.9) exhibits a fragment at m/z 136, indicating the presence of a tyrosyl moiety, suggesting the structure is cyclo(prolyl-tyrosyl) (B1)28. Similarly, the parent ion with m/z 311.1 (C18H18N2O3) shows fragments at m/z 136 (tyrosyl) and m/z 120 (phenylalanyl), pointing to the structure cyclo(phenylalanyl-tyrosyl) (B2)28.

Other observed fragments result from the loss of a carbonyl group (CO, −28), as seen in the fragmentation patterns. For instance, the parent ion with m/z 295.1 (C18H18N2O2) loses a CO group to yield a fragment at m/z 267, consistent with the structure cyclo(phenylalanyl-phenylalanyl) (B5)29. Similarly, the parent ions with m/z 261.0 (C14H16N2O3, Rt 2.1) and m/z 245.0 (C14H16N2O2) lose CO to produce fragments at m/z 233 and 216, respectively, indicating the structures cyclo(hydroxyprolyl-phenylalanyl) (3) and cyclo(prolyl-phenylalanyl) (7)30,31. Additionally, the parent ion with m/z 261.1 (C15H20N2O2, Rt 4.6) shows fragments at m/z 120 (phenylalanyl) and 233, suggesting the structure cyclo(leucyl-phenylalanyl) (B4)29. These patterns highlight how the loss of CO, along with the detection of specific ions, aids in the structural elucidation of DKPs.

Pyrrolidine alkaloids

The molecular network (Fig. 1, cluster C) showed various nodes with parent ions at m/z 304.3 (compound C3), 332.3 (C5), 360.3 (C6), and 388.4 (C7), and base peaks at m/z 212, 240, 268 and 296, respectively (Figure S5d, Table S2). These resulted from the neutral loss of a benzyl moiety (92 amu), and suggestive of benzyl-hydroxy-pyrrolidine moiety with a long alkyl substituent32. Notably, all the aforementioned nodes exhibit a 28 amu increase, both in the parent and fragment ions after the neutral loss of the benzyl moiety. This pattern suggests that each compound is two methylenes larger than the previous one, and their structures have been proposed as 2-benzyl-3-hydroxy-5-nonyl-pyrrolidine (C3), 2-benzyl-3-hydroxy-5-undecyl-pyrrolidine (C5), 2-benzyl-3-hydroxy-5-tridecyl-pyrrolidine (C6), and 2-benzyl-3-hydroxy-5-pentadecyl-pyrrolidine (C7).

Fukuda and co-workers revealed the biosynthetic pathway of preussin B, a similar alkyl-hydroxy-pyrrolidine metabolite33. They proved that such metabolites were formed by the condensation of phenylalanine amino acid with a polyketide chain, followed by Claisen-type intramolecular cyclization, reduction, and malonate-based side chain elongation (Fig. 2). Such metabolic pathway explains the two-carbon extension pattern of metabolites. Furthermore, the incorporation of amino acids in the biosynthetic pathway (Fig. 2) explains the structures of other nodes displaying parent ions at m/z 343.3 and 399.3 in the same cluster (C), with base peaks at m/z 240 and 296, respectively. These fragment ions result from the neutral loss of 103 amu, corresponding to the side chain of the amino acid arginine (Figure S5d). Consequently, the structures of such compounds could be tentatively suggested as 2-(3-diaminomethyl-aminopropyl)−3-hydroxy-5-undecyl-pyrrolidine (C1), and 2-(3-diaminomethyl-aminopropyl)−3-hydroxy-5-pentadecyl-pyrrolidine (C4) (Figure S5d, Table S2). Apart from cluster C, a singleton node (m/z 371.3) exhibited similar fragmentation patterns as previously discussed and was annotated as 2-(3-diaminomethyl-aminopropyl)−3-hydroxy-5-tridecyl-pyrrolidine (C2), respectively (Fig. 1).

The proposed structures of 1, A2, C1-C2, and C4-C7 were suggested based on available MS/MS data and biosynthetic similarities in other fungal species, have not yet been reported in natural products literature to date and require further isolation and detailed structure elucidation for the confirmation of their structures and configurations.

Molecular network established using LC-MS/MS data of the EtOAc fractions of A. flavus (red) and C. colombiae (green) in the positive ion mode. Each node is displayed as a pie chart to reflect the relative abundance of each molecular ion in the analyzed samples. Cluster A: bisphenols, cluster B: DKPs, and cluster C: pyrrolidine alkaloids.

Isolation of fungal metabolites

EtOAc fractions of the selected fungal extracts were subjected to bioassay-guided purification leading to the isolation of a new natural metabolite 1, alongside seven previously known compounds 2–8. Notably, four of these compounds were detected in the LC-MS/MS analysis conducted in this study (Fig. 1, Table S2). The aim of the isolation process is to identify and characterize the key bioactive compounds within the bioactive EtOAc fractions of the two fungi, which may be responsible for the observed antiosteoporosis activity, thereby facilitating the development of targeted therapeutic agents.

Compound 1 was isolated as an optically inactive colorless solid \(\:{\left[{\upalpha\:}\right]}_{\text{D}}^{25}\) +0.01 (c 2.7, MeOH), its molecular formula C23H32O6, was deduced from HRESI-MS m/z 427.2095 [M + Na]+ calculated for C23H32O6Na.

13C-NMR spectrum (Table 1, Figure S6b) showed only 10 resonances indicating the presence of overlapped signals1. H-NMR (Table 1, Figure S6a) and HSQC (Figure S6d) spectra revealed the presence of six protons’ singlet [δH 1.62 (s), δC 32.0, (C-6 and 6’)], two singlet methoxy groups, four ortho-coupled methines, four oxymethylenes, and two oxymethines.

Molecular formula together with signal integration and chemical shift distribution provided evidence that 1 is dimeric in nature. HMBC (Table 1, Figure S6e) from H-2, H-2’, H-3, and H3’ to C-1 and C-4 together with the chemical and magnetic equivalence of H-2/H-2’ and H-3/H-3’ established the p-substituted ring system of 1. The chemical shift of C-1 at δC 156.3 suggested the phenolic nature of C-1. On the other hand, COSY correlations (Figure S6c) established the spin system H-7/H-8/H-9 of the glycerol moiety, and the HMBC cross peak from H2−7 to C-1 confirmed the connection of the glyceryl moiety to C-1, while the HMBC from H3−10 to C-9 suggested the methoxylation of C-9.

The methyl singlet H3−6 (δH 1.62) showed HMBC to the aliphatic quaternary carbon (δC 41.66, C-5), and the aromatic quaternary carbons (δC 143.50, C-4). This confirmed the para substitution of the bisphenol via C-5. The methyl singlet also showed an HMBC correlation to an attached carbon, indicating the overlap of gem-dimethyl groups. The aliphatic moiety at C-1 was confirmed by HMBC correlations of methylene protons (δH 3.99) to C-1, and the other methylene carbon (δC 73.44, C-9). Moreover, methylene protons (δH 3.56) showed HMBC correlations to oxy methine (δC 68.80, C-8), and oxy methyl (δC 59.24, C-10). On the basis of these data, the structure was confirmed as a dimeric compound, and by comparing the obtained data with the available literature, compound 1 (Fig. 4; Table 1) was assigned 2,2-bis‐[4‐(2‐hydroxy-3-methoxy-propoxy)phenyl]propane, characterized by dimethyl substitution at the terminal hydroxyl groups on both sides, unlike the other bisphenol derivatives. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report of this compound as a naturally occurring metabolite.

Compound 2 (Fig. 4) was isolated as a colorless solid whose chemical formula C22H30O6 was deduced from ESI-MS m/z 413.34 [M + Na]+1. H-NMR and 13C-NMR spectra (Figures S7a, S7b) were very similar to that of 1 and matched with the reported spectra of 2-[4‐(2-hydroxy-3-methoxy-propoxy)phenyl]‐2‐[4‐(2,3-dihydroxy-propoxy)phenyl]propane34.

Other isolated compounds (Fig. 4) were identified by comparison of their spectral data with previously reported compounds and were revealed to be 3S*,6S*,8R*-cyclo(trans−8-hydroxyprolyl-phenylalanyl) (3)30,313S*,6S*,8R*-cyclo(trans−8-hydroxyprolyl-leucyl) (4)35trans-cinnamic acid (5)363S*,6S*-cyclo(prolyl-leucyl) (6)353S*,6S*-cyclo(prolyl-phenylalanyl) (7)35and altenuene (8)37 (Figs. 4, S8).

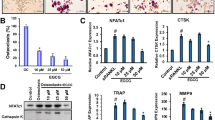

Evaluation of the antiosteoporosis activity of the isolated compounds

All isolated compounds were tested for their ability to inhibit osteoclastogenesis upon stimulation of RANKL-induced differentiation of RAW264 cells with the formation of MNCs. Compounds 1 (2,2-bis‐[4‐(2‐hydroxy-3-methoxy-propoxy)phenyl]propane) and 8 (altenuene) significantly inhibited the formation of MNCs, with IC50 values 57.14 and 38.35 µM, respectively, with no toxic effect against RAW264 macrophages at the highest tested concentration (Fig. 5). Other compounds showed no inhibition against RANKL-induced formation of MNCs from RAW264 macrophages.

Compound 1 has the bisphenol skeleton, which is related to bisphenol A as the simplest member of such structural family. Some studies discussed the effect of bisphenol A on bone metabolism as it mimics endogenous estrogen, inhibits osteoblast, and leads to bone loss38,39. Bisphenol compounds exert both estrogenic agonism, via binding to ERα and ERβ and antiandrogenic activity. Both properties that can influence bone remodeling. For example, BPAF binds ERα with nanomolar affinity and functions as a full agonist, upregulating genes such as Runx2 and osteocalcin, which promote osteoblast differentiation and bone formation40. Conversely, these compounds antagonize the androgen receptor (AR), blocking AR-mediated transcriptional programs that normally support osteoblast proliferation and inhibit osteoclastogenesis41. Because androgens, and AR signaling contribute to bone mass maintenance in both sexes, antiandrogenic bisphenols may counterbalance their estrogenic benefits, especially in men or premenopausal women.

As the aliphatic chain substituting the glyceryl residue increases, the amelioration of dexamethasone-induced osteoporosis is increased, such as in the case of bisphenol A diglycidyl ether42. Such observation supports the difference in activity between 1 and 2, where increasing the degree of methylation in 1 rendered it more active than 2. This observation can offer an additional perspective for developing more active semisynthetic derivatives of bisphenol diglycidic acid ethers based on the structure-activity relationship deduced from 1 to 2.

On the other hand, 8 isolated from C. colombiae exhibited significant inhibition of MNCs formation (Fig. 5). Altenuene (8) is a benzochromenone derivative first isolated from Alternaria tenuis43. It has potential antioxidant activity that could be attributed to its dibenzo-α-pyrone function44. Its ability to reduce oxidative stress can explain several of its activities such as anti-inflammatory activities37,45. Meanwhile, oxidative stress is directly linked to osteoclastogenesis in several ways, it can upregulate RANKL expression with the downregulation of osteoprotegerin46,47. This can increase osteoclast differentiation and activity. Moreover, oxidative stress can induce apoptosis of osteocytes and osteoblasts which will generate additional amounts of RANKL, promoting osteoclastogenesis48. Therefore, the antioxidant properties of altenuene (8) are believed to be the key activity explaining its anti-osteoclastogeneic potential.

(a) Effects of compounds 1 and 8 on RANKL-induced osteoclast differentiation of RAW 264 cells. RAW 264 cells were treated with RANKL (50 ng/mL) in the presence or absence of 1 or 8 at the indicated concentrations and cultured for 4 days. The cells were stained using a TRAP-staining solution, and the number of TRAP-positive multinuclear (> 3 nuclei) cells was counted. Experiments were performed in triplicate, error bars stand for standard deviation, and asterisks show significant differences at p < 0.005 according to the Student’s t-test. (b) TRAP-stained RAW 264 cells incubated with 50 ng/mL RANKL in the presence or absence of 2 or 8 (20 µM). The Scale bar represents 200 nm.

ADMET prediction

For the two active compounds (1,8), (Table S3a, Figure S9) both compounds fall within the favorable range defined by Lipinski’s Rule of Five, and neither compound shows any rule violations, indicating a high probability of good oral bioavailability and cell membrane permeability. Also, both values comply with drug-likeness criteria (HBA < 10, HBD < 5), supporting the potential for adequate membrane permeability. Compound 1 has a significantly lower water solubility (log S = −4.42) compared to compound 8 (log S = −2.23), which may pose challenges for formulation and absorption, especially for oral delivery. Both compounds have values remain below the 140 Ų threshold associated with good intestinal absorption26.

ADMET properties

In terms of Caco-2 cell permeability (Table S3b), compound 1 exhibits superior performance (1.307 log Papp) over compound 8 (0.809), suggesting more efficient transcellular absorption. This is further confirmed by intestinal absorption predictions: compound 1 shows 95.08% absorption compared to 73.31% for compound 8. Regarding blood-brain barrier (BBB) and CNS permeability, both compounds show negative log BB values (< −0.3), suggesting limited penetration into the central nervous system. This is a favorable trait for peripheral drug targets, minimizing potential CNS side effects. In terms of metabolism, compound 1 is predicted to inhibit CYP3A4, a key metabolic enzyme, which may increase the risk of drug-drug interactions. Compound 8 shows no inhibition of major cytochrome P450 enzymes, indicating a lower metabolic liability.

Clearance predictions show slightly higher total clearance (log ml/min/kg) for compound 8 (0.605) than for compound 1 (0.58), suggesting faster systemic elimination. Both compounds are predicted to be non-mutagenic (negative Ames test) and non-hepatotoxic, indicating an acceptable safety profile. However, compound 1 demonstrates a higher acute oral toxicity (LD₅₀ = 2.485 mol/kg) compared to compound 8 (LD₅₀ = 2.212 mol/kg), which could imply a narrower therapeutic window and necessitates caution in dose selection26.

Conclusion

This study highlights the promising potential of sponge-derived fungi as a rich source of bioactive compounds with therapeutic applications. The identification of two fungal isolates, A. flavus and C. colombiae, underscores the importance of marine ecosystems in uncovering novel microbial resources for drug discovery. Utilizing LC-MS/MS and molecular network, eight new naturally occurring compounds (1, A2, C1, C2, C4-C7) were tentatively identified. Through bioassay-guided isolation and structural elucidation, two bioactive compounds (1 and 8) were discovered, demonstrating significant anti-osteoclastogenic activity by inhibiting RANKL-induced multinucleated osteoclast formation with IC50 values 57.14 and 38.35 µM, respectively. This suggests their potential as therapeutic candidates for the treatment of osteoporosis. Notably, based on our knowledge, this is the first report describing the anti-osteoclastogenesis of 1 and 8. ADMET properties revealed that compound 1 demonstrates excellent predicted absorption and permeability, but poor solubility and potential CYP3A4 inhibition could limit its bioavailability and safety. While Compound 8 exhibits a better balance of solubility, safety, and metabolic stability, making it a more promising lead compound for further development as an oral drug candidate.

This study not only expands our understanding of the chemical diversity within fungi but also paves the way for the development of novel anti-osteoporotic therapies. However, further mechanistic studies are essential to elucidate the inhibitory mechanisms of these metabolites. Such insights will facilitate a comprehensive structure-activity relationship analysis and enable the development of derivatives with improved pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic properties.

Data availability

All materials and data are available free of charge in the manuscript and supplementary material. The datasets generated for large subunit ribosomal RNA partial sequence analysis during the current study are available in the GenBank repository, with accession numbers PQ423742 for A. flavus (Aspergillus flavus isolate B8-5 large subunit ribosomal RNA gene, part - Nucleotide - NCBI) and PQ423748 for C. colombiae (Cladosporium colombiae isolate A7-1 large subunit ribosomal RNA gene, - Nucleotide - NCBI).GenBank is a member repository of INSDC (International Nucleotide Sequence Database Collaboration).

References

Boyle, W. J., Simonet, W. S. & Lacey, D. L. Osteoclast differentiation and activation. Nature 423, 337–342 (2003).

Li, S., Xue, S. & Li, Z. Osteoporosis: emerging targets on the classical signaling pathways of bone formation. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 973, 176574 (2024).

Jiang, T. et al. Role and regulation of transcription factors in osteoclastogenesis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24, 16175 (2023).

Valentin, G. et al. Socio-economic inequalities in fragility fracture outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prognostic observational studies. Osteoporos. Int. 31, 31–42 (2020).

Anish, R. J. & Nair, A. Osteoporosis management-current and future perspectives–A systemic review. J. Orthop. 53, 101–113 (2024).

El-Desoky, A. H. & Tsukamoto, S. Marine natural products that inhibit osteoclastogenesis and promote osteoblast differentiation. J. Nat. Med. 76, 575–583 (2022).

El-Desoky, A. H. et al. Ceylonamides A–F, nitrogenous spongian diterpenes that inhibit RANKL-Induced osteoclastogenesis, from the marine sponge Spongia ceylonensis. J. Nat. Prod. 79, 1922–1928. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jnatprod.6b00158 (2016).

El-Beih, A. A. et al. New inhibitors of RANKL-induced osteoclastogenesis from the marine sponge Siphonochalina siphonella. Fitoterapia 128, 43–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fitote.2018.05.001 (2018).

Xu, L. L., Cao, F., Tian, S. S. & Zhu, H. J. Alkaloids and polyketides from the soil fungus Aspergillus terreus and their antibacterial activities. Chem. Nat. Compd. 53, 1212–1215 (2017).

Varoglu, M. & Crews, P. Biosynthetically diverse compounds from a saltwater culture of sponge-derived Aspergillus Niger. J. Nat. Prod. 63, 41–43 (2000).

Guo, Y. et al. Taxonomy driven discovery of polyketides from Aspergillus Californicus. J. Nat. Prod. 84, 979–985 (2021).

Liu, L. et al. Aspersteroids A–C, three rearranged ergostane-type steroids from Aspergillus Ustus NRRL 275. Org. Lett. 23, 9620–9624 (2021).

Domingos, L. T. S. et al. Secondary metabolites diversity of Aspergillus Unguis and their bioactivities: A potential target to be explored. Biomolecules 12, 1820 (2022).

El-Desoky, A. H. et al. Taichunins E–T, isopimarane diterpenes and a 20-nor-isopimarane, from Aspergillus taichungensis (IBT 19404): structures and inhibitory effects on RANKL-induced formation of multinuclear osteoclasts. J. Nat. Prod. 84, 2475–2485 (2021).

Hu, H. C. et al. Secondary metabolites and bioactivities of Aspergillus ochraceopetaliformis isolated from Anthurium Brownii. Acs Omega. 5, 20991–20999 (2020).

Pichler, K. et al. Bisphosphonates in multicentric osteolysis, nodulosis and arthropathy (MONA) spectrum disorder–an alternative therapeutic approach. Sci. Rep. 6, 34017 (2016).

Lewiecki, E. M. Safety and tolerability of denosumab for the treatment of postmenopausal osteoporosis. Drug Healthc. Patient Saf. 3, 79–91 (2011).

Ponnapakkam, T., Katikaneni, R., Sakon, J., Stratford, R. & Gensure, R. Treating osteoporosis by targeting parathyroid hormone to bone. Drug Discovery Today. 19, 204–208 (2014).

Abd El-Razek, M. H. et al. Anti-inflammatory Pregnene steroids from the oleo-gum resin of Commiphora mukul: in-vitro and in-silico studies. Phytochem. Lett. 64, 106–116 (2024).

Morrow, C. C. et al. Molecular phylogenies support homoplasy of multiple morphological characters used in the taxonomy of heteroscleromorpha (Porifera: Demospongiae). Integr. Comp. Biol. 53, 428–446 (2013).

Sayed, M. A. E., El-Rahman, T., El-Diwany, M. A. A., Sayed, S. M. & A. I. & Biodiversity and bioactivity of red sea sponge associated endophytic fungi. Int. J. Adv. Res. Eng. Appl. Sci. 5, 1–15 (2016).

Keral, N., Shivashankar, M. & Manmohan, M. Evaluation of cultural conditions on the growth of marine fungi and their antimicrobial activity. Res. J. Life Sci. Bioinform Pharm. Chem. Sci. 5, 307–319 (2019).

Selim, K. A., El-Beih, A. A. & Abdel-Rahman, T. M. El-Diwany, A. I. Biological evaluation of endophytic fungus, Chaetomium globosum JN711454, as potential candidate for improving drug discovery. Cell Biochem. Biophys. 68, 67–82 (2014).

Tsukamoto, S. et al. Halenaquinone inhibits RANKL-induced osteoclastogenesis. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 24, 5315–5317. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bmcl.2014.09.043 (2014).

Essa, A. F. et al. Integration of LC/MS, NMR and molecular Docking for profiling of bioactive diterpenes from Euphorbia mauritanica L. with in vitro Anti-SARS‐CoV‐2 activity. Chem. Biodivers. 20, e202200918 (2023).

Egbuna, C., Patrick-Iwuanyanwu, K. C., Onyeike, E. N., Khan, J. & Alshehri, B. FMS-like tyrosine kinase-3 (FLT3) inhibitors with better binding affinity and ADMET properties than Sorafenib and gilteritinib against acute myeloid leukemia: in Silico studies. J. Biomol. Struct. Dynamics. 40, 12248–12259 (2022).

Majedi, S. M. & Lai, E. P. Mass spectrometric analysis of bisphenol A desorption from Titania nanoparticles: ammonium acetate, fluoride, formate, and hydroxide as chemical desorption agents. Methods Protocols. 1, 26 (2018).

Furtado, N. A. J. C. et al. Fragmentation of diketopiperazines from Aspergillus fumigatus by electrospray ionization tandem mass spectrometry (ESI-MS/MS). J. Mass Spectrom. 42, 1279–1286. https://doi.org/10.1002/jms.1166 (2007).

Jia, J. et al. 2,5-Diketopiperazines: A review of source, synthesis, bioactivity, structure, and MS fragmentation. Curr. Med. Chem. 30, 1060–1085. https://doi.org/10.2174/0929867329666220801143650 (2023).

Fdhila, F., Vázquez, V., Sánchez, J. L. & Riguera, R. DD-Diketopiperazines: antibiotics active against Vibrio a nguillarum isolated from marine Bacteria associated with cultures of Pecten m Aximus. J. Nat. Prod. 66, 1299–1301 (2003).

Jiang, Z. et al. Two diketopiperazines and one halogenated phenol from cultures of the marine bacterium, Pseudoalteromonas luteoviolacea. Nat. Prod. Lett. 14, 435–440 (2000).

Buttachon, S. et al. Bis-Indolyl benzenoids, Hydroxypyrrolidine derivatives and other constituents from cultures of the marine Sponge-Associated fungus Aspergillus Candidus KUFA0062. Mar. Drugs. 16, 119 (2018).

Fukuda, T., Sudoh, Y., Tsuchiya, Y., Okuda, T. & Igarashi, Y. Isolation and biosynthesis of Preussin B, a pyrrolidine alkaloid from simplicillium lanosoniveum. J. Nat. Prod. 77, 813–817. https://doi.org/10.1021/np400910r (2014).

Zhang, C. et al. Platensimycin and Platencin congeners from Streptomyces platensis. J. Nat. Prod. 74, 329–340. https://doi.org/10.1021/np100635f (2011).

Sawadsitang, S., Suwannasai, N., Mongkolthanaruk, W., Ahmadi, P. & McCloskey, S. A new amino amidine derivative from the wood-decaying fungus xylaria cf. cubensis SWUF08-86. Nat. Prod. Res. 32, 2260–2267 (2018).

Hanai, K., Kuwae, A., Takai, T., Senda, H. & Kunimoto, K. K. A comparative vibrational and NMR study of cis-cinnamic acid polymorphs and trans-cinnamic acid. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 57, 513–519 (2001).

Elbermawi, A. et al. Anti-diabetic activities of phenolic compounds of Alternaria sp., an endophyte isolated from the leaves of desert plants growing in Egypt. RSC Adv. 12, 24935–24945 (2022).

Karunarathne, W. A. H. M., Choi, Y. H., Park, S. R., Lee, C. M. & Kim, G. Y. Bisphenol A inhibits osteogenic activity and causes bone resorption via the activation of retinoic acid-related orphan receptor α. J. Hazard. Mater. 438, 129458 (2022).

Thent, Z. C., Froemming, G. R. A. & Muid, S. Bisphenol A exposure disturbs the bone metabolism: an evolving interest towards an old culprit. Life Sci. 198, 1–7 (2018).

Matsushima, A., Liu, X., Okada, H., Shimohigashi, M. & Shimohigashi, Y. Bisphenol AF is a full agonist for the Estrogen receptor ERα but a highly specific antagonist for ERβ. Environ. Health Perspect. 118, 1267–1272 (2010).

Chin, K. Y., Pang, K. L. & Mark-Lee, W. F. A review on the effects of bisphenol A and its derivatives on skeletal health. Int. J. Med. Sci. 15, 1043 (2018).

Wang, Y., Pan, Z. & Chen, F. Inhibition of PPARγ by bisphenol A diglycidyl ether ameliorates dexamethasone-induced osteoporosis in a mouse model. J. Int. Med. Res. 47, 6268–6277 (2019).

Pero, R. W., Owens, R. G., Dale, S. W. & Harvan, D. Isolation and indentification of a new toxin, altenuene, from the fungus Alternaria tenuis. Biochim. Et Biophys. Acta (BBA) - Gen. Subj. 230, 170–179. https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-4165(71)90064-X (1971).

Bialonska, D., Kasimsetty, S. G., Khan, S. I., Ferreira, D. & Urolithins Intestinal microbial metabolites of pomegranate ellagitannins, exhibit potent antioxidant activity in a Cell-Based assay. J. Agric. Food Chem. 57, 10181–10186. https://doi.org/10.1021/jf9025794 (2009).

Bhagat, J. et al. Cholinesterase inhibitor (Altenuene) from an endophytic fungus Alternaria alternata: optimization, purification and characterization. J. Appl. Microbiol. 121, 1015–1025 (2016).

Kimball, J. S., Johnson, J. P. & Carlson, D. A. Oxidative stress and osteoporosis. JBJS 103, 1451–1461. https://doi.org/10.2106/jbjs.20.00989 (2021).

Domazetovic, V., Marcucci, G., Iantomasi, T., Brandi, M. L. & Vincenzini, M. T. Oxidative stress in bone remodeling: role of antioxidants. Clin. Cases Mineral. Bone Metabolism: Official J. Italian Soc. Osteoporos. Mineral. Metabolism Skeletal Dis. 14, 209–216. https://doi.org/10.11138/ccmbm/2017.14.1.209 (2017).

Zhu, C. et al. Autophagy in bone remodeling: A regulator of oxidative stress. Front. Endocrinol. 13 https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2022.898634 (2022).

Acknowledgements

“This paper is based upon work supported by Science, Technology & Innovation Funding. Authority (STDF), Egypt under grant No: 50741”.

Funding

Open access funding provided by The Science, Technology & Innovation Funding Authority (STDF) in cooperation with The Egyptian Knowledge Bank (EKB).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: A.A.E., A.A.E.-B and A.H.E.-D.; Methodology: A.A.E., A.A.E.-B and A.H.E.-D.; Investigation: A.A.E., A.A.E.-B and A.H.E.-D.; Data Curation: A.A.E., A.A.E.-B, A.H.E.-D. and A.M.O., Writing—Original Draft: A.A.E.-B and A.H.E.-D.; Writing—Review & Editing: A.A.E.B., A.M.O. and A.M.E.-F; Supervision: A.A.E.-B and A.M.E.-F.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Elgahamy, A.A., El-Desoky, A.H., Otify, A.M. et al. Molecular networking derived from untargeted LC-MS/MS analysis to discover inhibitors of RANKL-induced osteoclastogenesis from Egyptian marine sponge-associated fungi. Sci Rep 15, 27137 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-12456-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-12456-y