Abstract

The development of wearable electronics and the current era of big data requires the sustainable power supply of numerous distributed sensors. In this paper, we designed and experimentally studied an energy harvester based on ferrofluid sloshing. The harvester contains a horizontally positioned cylindrical vial, half-filled with a ferrofluid exposed to a magnetic field. The vial is excited by a laboratory shaker and the induced voltage in a nearby coil is measured under increasing and decreasing shaking rates. Five ferrofluid samples are involved in the study, yielding the dependence of the electromotive force on the ferrofluid magnetization of saturation. The energy harvesting by ferrofluid sloshing is investigated in various magnetic field configurations. It is found that the most effective magnetic field configuration for the energy harvesting is characterized by the field intensity perpendicular to the axis of the vial motion and gravity. The harvested electric power linearly increases with the ferrofluid magnetization of saturation. The electromotive force generated by each ferrofluid is found identical for measurements in acceleration and deceleration mode. A significant reduction in the induced voltage is observed in a stronger magnetic field. The magneto-viscous effect and partial immobilization of the ferrofluid in the stronger magnetic field is considered. The magneto-viscous effect is documented by a supplementing experiment. The results extend knowledge on energy harvesting by ferrofluid sloshing and may pave the way to applications of ferrofluid energy harvesters for mechanical excitations with changing directions in regard to the magnetic field induction.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Mechanical vibration energy generated by industrial equipment or any daily production and life usually results in huge energy waste. This fact has stimulated intensive research on exploitation of the available mechanical energy sources and turning them into essential processes for effective electricity generation1. The demand on such energy harvesting is of importance in the current era of big data, when a problem of power supply of numerous distributed sensors must be addressed. Furthermore, the development of wearable electronics characterized by miniaturization, lightweight and biocompatibility strengthens the importance of portable, ubiquitous, and sustainable power supplies. The energy required to power the wearable electronics, micro-electromechanical systems or the internet of things-based devices reaches from mW to µW2,3. An efficient way of powering such low-energy devices is based on self-powering. The self-powering technique refers to the generation of electrical power from renewable energy sources from the environment, like the abundant waste mechanical energy4.

The primary mechanisms of vibration energy transformation to electric energy are based on electrostatic induction, electromagnetic induction, and triboelectric or piezoelectric effects5. There are various active media in the developing nanogenerators, including stretchable nanocomposites6 and gas-driven nanogenerators7. In many studies, the active media are liquids due to their conformability to any container and facile response to mechanical excitations. For instance, the flow of a dielectric fluid between two dielectric films may change the capacitance and convert mechanical energy into electrical energy8. Zou et al. designed an electromagnetic walking energy harvester based on miniature water turbine9. Liang et al. developed a wearable device with liquid metal-based frictional electric nanogenerator10. Indeed, the current literature witnesses an intensive research on nanogenerators using the solid-liquid triboelectric effect11and triboelectric nanogenerators have shown extraordinary potential in the field of vibration energy harvesting12. The basic principles and future challenges of direct current triboelectric nanogenerators have been reviewed recently in ref13. Thus, it is seen that the current research results of triboelectric nanogenerator-based vibration energy harvesters are abundant, but the output effect still has great room for improvement, and further research is needed for efficient energy harvesting.

Recently, a particular research attention has been paid to ferrofluids in the role of a nanogenerator’s active medium. In general, ferrofluids are stable colloidal suspensions of magnetic nanoparticles in a liquid carrier, thus integrating excellent magnetic and fluid properties14. Within the energy harvesting research, Chen et al. proposed a solid-ferrofluid triboelectric nanogenerator for ultra-low-frequency vibration energy harvesting15. Yang et al. developed a ferrofluid-based energy harvesting device combining ferrofluids with triboelectric nanogenerator, reducing the friction thermal effects and improving the conversion efficiency16. The basic principles, design and significance of ferrofluid-based triboelectric nanogenerators were published in a recent review paper by Kulandaivel et al.2. Besides the investigation of ferrofluids in triboelectric nanogenerators, the ferrofluids are also explored for liquid sloshing piezoelectric energy harvesters17 or for multifunctional liquid robotics18. However, ferrofluids have gained recognition primarily for their great potential in electromagnetic energy harvesting systems, utilizing the basic principles of electromagnetic induction. In contrast to conventional electromagnetic generators that rely on solid moving magnets19 ferrofluids enable creation of generators of light-weight, smaller size and flexible shapes. On the one hand, ferrofluids in energy harvesting systems can be used in combination with moving solid magnets. For instance, a ferrofluid was applied in a vibration energy harvester as a lubricant and liquid spring20. In another study, a ferrofluid with low damping characteristics was applied to reduce the friction between the suspension magnet and the tube wall, effectively improving the output performance of the energy harvester21. In this way, nonlinear electromagnetic vibration energy harvesters with magnetic, mechanical, and liquid springs lubricated by ferrofluids were found out in several papers22,23,24.

On the other hand, utilization of sloshing motion of ferrofluids has led to development of electromagnetic energy harvesters without solid moving magnets. Bibo et al. proposed an electromagnetic micro-power generator utilizing the sloshing of a ferrofluid column in an excited tank to transform mechanical motions directly into electricity25. The principle consists in the sloshing of the magnetized ferrofluid resulting in changes of orientational order of the magnetic dipoles, so creating time-varying magnetic flux. Subsequently, this flux induces an electromotive force in a coil near the container. In such ferrofluid-based energy harvester devices, permanent magnets are not moving but in a fixed positions adjacent the ferrofluid container to magnetize the ferrofluid, and the coil may be wound on a ferromagnetic yoke26. Alazemi et al. optimized the container’s dimensions and the ferrofluid level such that the modal frequencies of the sloshing ferrofluid were nearly commensurate27. In another study, they developed a theoretical nonlinear model governing the electro-magneto-hydrodynamics of the ferrofluid-based energy harvester28. By using perturbation methods, they obtained an approximate analytical solution of the model involving primary resonance excitation of the first mode and a two-to-one internal resonance between the first two modes. In a paper by Liu et al., the developed computational model solves the coupled Maxwell’s equations and Navier-Stokes equations for the dynamic behavior of the magnetic field and the fluid motion29. The numerical results demonstrated that the basic mechanism responsible for the time-varying magnetic flux in the coils is the changing magnetization of the sloshing ferrofluid. The parametric study and performance analysis revealed several parameters affecting the induced electromotive force30. For instance, the higher magnetic field intensity leads to a greater electromotive force, but extremely high fields immobilize the ferrofluid in the tank. It was proven that the electromotive force changes significantly with magnetic field distribution and ferrofluid susceptibility.

The advantages of using sloshing ferrofluids instead of a permanent magnet consist in the ferrofluid’s shape-conformability, light weight and ability to response a broad range of mechanical excitations. However, even though the computational modeling and analysis in the reported papers were validated against experimental results, one should admit that such experiments are rare and there is a lack of the experimental verification of several parameters determining the electromotive force. The above referenced experiments on energy harvesting from sloshing of ferrofluids were performed on one ferrofluid sample with a given nanoparticle concentration. In our study, we involve five ferrofluid samples with different nanoparticle concentrations. This enables us to obtain the dependence of the electromotive force on the ferrofluid magnetization of saturation empirically. We also study the electromagnetic induction by ferrofluid sloshing in various magnetic field configurations. Unlike the published experiments, our ferrofluid sloshing is excited by a laboratory shaker and the induced voltage is studied under both, increasing and decreasing shaking rates (frequency). In this way we can verify if the ferrofluid-based harvester is dependent on the running direction or no. Moreover, in order to follow the environmental requirements, we prepared the ferrofluid for this study on biodegradable transformer oil. Thus, our ferrofluid energy harvester does not pose a risk in a case of the device leakage or ferrofluid spill. The paper is organized as follows. In Sect. "Materials and methodology", we present fundamental characterization of the ferrofluids employed in the study and we describe an experimental setup of the ferrofluid-based energy harvester. Section "Theoretical background" provides a basic and brief theoretical background selected for this study. In Sect. "Results and discussion", we present and discuss the obtained results. Finally, the conclusions are drawn in Sect. "Conclusion".

Materials and methodology

Ferrofluids employed in the energy harvesting study are prepared on readily biodegradable transformer oil Shell Diala S5 BD. The oil has relatively low density (816 kg/m3 at 20 °C), viscosity (7.4 mm2/s at 40 °C), and interfacial tension (48 mNm), as stated by the manufacturer. Besides its biodegradable nature, the given values of the three quantities motivates us to use the oil for this study, as they play decisive role in the liquid sloshing dynamics30. The magnetic nanoparticles for the ferrofluid preparation were synthesized by the well-known chemical co-precipitation method with easy-to-control reaction conditions31. The reaction principle is based on the following reaction equation: Fe2+ + 2Fe3+ + 8OH− → Fe3O4↓ + 4H2O. The precipitated nanoparticles were sterically functionalized by oleic acid C17H33COOH (80–82 °C), to ensure hydrophobicity of their surfaces. The functionalized nanoparticles were dispersed in the carrier oil32. Five ferrofluid samples with different nanoparticle concentrations were prepared in this way. The basic characteristics of the ferrofluids are listed in the Table 1.

The initial magnetic susceptibility was measured by AC susceptometer Imego Dynomag (SE) at room temperature (295 K) and frequencies ranging from 1 Hz up to 250 kHz. The real susceptibility values taken at 10 Hz are presented in Table 1. A vibration sample magnetometer installed on a cryogen-free superconducting magnet from Cryogenic Limited (UK) was employed to measure magnetization of the ferrofluids. The ferrofluid magnetic mass fraction was determined as a ratio of the ferrofluid magnetization of saturation to the magnetization of saturation of the powder nanoparticles (73 Am2/kg). Dynamic viscosity measurements were conducted using MCR-502 rheometer from Physica Anton Paar GmbH (AUT). We have applied the superposition of Langevin fitting functions on the magnetization curves33 and the size distribution presented in Fig. 1 has been obtained. Note, the presented sizes reflect the sizes of the magnetic cores without dead layers and surfactants. The mean magnetic diameter of nanoparticles dispersed in the ferrofluids is 11.2 nm. Dynamic light scattering method (Malvern Zetasizer Nano ZS instrument, UK) found the average hydrodynamic nanoparticle diameter of 14.5 nm.

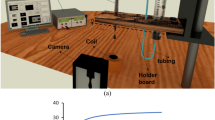

In order to investigate the vibration energy harvesting by the prepared ferrofluids, we constructed an experimental setup according to a block diagram in Fig. 2. The setup consists of a laboratory open-air shaker JEIO TECH, model OS-2000 (ROK) generating harmonic lateral motion with an amplitude of 10 mm and a speed range from 5 RPM to 500 RPM (revolutions per minute). Thus, the maximal frequency of the shaker motion is approx. 8 Hz (500 RPM). To employ the electromagnetic induction principle in the energy harvesting from the shaker, a copper coil is embedded in a polyethylene foam fixed on the shaker platform. The length of the coil is 31 mm and it is wound on a Teflon former. The number of turns (windings) is 600. The diameter of the copper wire is 0.75 mm. In the coil center there is a hollow with a diameter of 15.5 mm. Induction of the coil at 1 kHz frequency is 47 mH and the DC resistance is 10 Ω at room temperature. The investigated ferrofluids are poured into a glass cylindrical vial with the length of 47 mm and diameter of 14.8 mm. The half-filled vial, containing 2.5 ml of the ferrofluid, is fixed horizontally in the coil center. In this way, the shaker driving platform gives harmonic excitations to the vial resulting in the ferrofluid sloshing dynamics. To keep the ferrofluid magnetized during the mechanical excitation, a permanent Neodymium magnet with dimensions of 40 × 24 × 9 mm is attached to the coil. The magnet is magnetized across its thickness (9 mm), and its remanence and coercivity are 1.25 T and 939 kA/m, respectively. The coil terminals are connected to an input of a digital storage oscilloscope (DSO) GW INSTEK GDS 2304 A (TW) enabling sensitive measurements of the induced voltage (electromotive force). The shaker and data acquisition from the oscilloscope are controlled by a software developed in VEE Pro 9.33, Keysight Technologies (USA). Before performing the experiments with the ferrofluids, we ran a testing experiment with the empty coil hole without any ferrofluid. It was found out that the movement of the platform carrying the coil and magnet does not induce any additional voltage. Then, the ferrofluid samples were inserted in the coil. We applied a measurement sequence starting in an idle position of the shaker. Then, the shaker speed was set to 10 RPM. The average, maximum and minimum RMS (root-mean-square) voltage values were calculated from 10 consecutive values recorded at the set speed. In the next steps, the speed was increasing up to 500 RPM with the step of 10 RPM, executing 10 vibrations at each settled speed and recording the voltage values. After executing the measurements at the maximal speed, the sequence continued in a decreasing regime in 10 RPM steps, back to the idle shaker position. The recorded data were finally statistically processed. The vibration energy harvesting experiments were conducted in a temperature-controlled laboratory with a stable ambient temperature of 23 °C.

The block diagram in Fig. 2 shows just one experimental configuration, when a single magnet is attached to the bottom of the horizontally lying vial, generating the magnetic field perpendicular to gravity and parallel with the axis of the vial motion. A simulated distribution of magnetic field lines acting on the vial in this configuration is presented in Fig. 3e. In addition to this configuration, the results will be presented also for four other configurations: the single magnet on the top of the horizontal vial providing the field intensity perpendicular to the axis of the vial motion and parallel with gravity (Fig. 3a); two magnets, one located at the bottom wall, one on the top wall of the vial, generating the field intensity perpendicular to the axis of the vial motion and parallel with gravity (Fig. 3b); two magnets on the side walls (left and right), generating the field intensity perpendicular to both, the axis of the vial motion and gravity (Fig. 3c); the single magnet attached to the vial side wall, providing the field intensity perpendicular to the axis of the vial motion and gravity (Fig. 3d). The simulations have been performed by using Finite Element Method by means of Agros Suite platform34. In the two-magnets configuration, the magnets are oriented in the attractive state (north facing south). The magnetic field induction in the center of the coil hole in the configurations with the single magnet is 15 mT. The two magnets generate the field of 34 mT in the center of the coil, which is 35 mm apart from the attached magnet. These values were found experimentally by using a handheld gaussmeter HGM09s (MAGSYS, DE).

Finite element method simulation of the static magnetic field generated by the permanent magnets attached to the coil surrounding the vial. The vectors v, G, B denotes the velocity of the vial motion, gravitational force and magnetic field induction, respectively. The rectangle with the black dot mark represents the permanent magnet, while the dot marks the north pole. The other rectangle represents the ferrofluid cross-section exposed to the magnetic field. In (a), the single magnet is on the top of the horizontal vial providing the field intensity perpendicular to the vial motion and parallel with gravity. In (b), one magnet is located at the bottom, one on the top wall of the vial, generating the field intensity perpendicular to the vial motion and parallel with gravity. In (c), two magnets are attached to the side walls, generating the field intensity perpendicular to both, the vial motion and gravity. In (d), the single magnet is attached to the vial side wall, providing the field intensity perpendicular to the vial motion and gravity. In (e), the single magnet is attached to the bottom of the horizontal vial, generating the magnetic field parallel to the vial motion and perpendicular to gravity.

Theoretical background

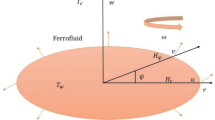

Theoretical considerations on sloshing dynamics of ferrofluids are often restricted to ferrofluids in an upright cylindrical container subjected to sinusoidal lateral excitation \(\:x\left(t\right)={X}_{0}\text{sin}{\omega\:}t\), with \(\:{X}_{0}\) denoting the excitation amplitude and \(\:{\omega\:}t\) denoting the phase angle35. The fluid field equations of ferrofluids in moving containers are the same as for nonmagnetic liquids except that the unsteady Bernoulli equation has an additional term due to the magnetic field. For irrotational, inviscid, and incompressible flow, a velocity potential function \(\:\Phi \:\) exists and satisfies the continuity equation:

where the radial distance \(\:r,\) the azimuthal angle \(\:\theta\:\), and the height \(\:z\) constitute the cylindrical coordinate system. The unsteady Bernoulli equation can be then written as

where \(\:p\) is the pressure, \(\:\rho\:\) is the ferrofluid density, g is the gravitational acceleration, z is the vertical height, \(\:{\mu\:}_{0}\) is the magnetic permeability of vacuum, H is the magnetic field intensity, M is the magnetization, \(\:{X}_{0}\)is the excitation amplitude and \(\:{\omega\:}\) is the excitation frequency. With this form of Bernoulli equation, it is assumed that the surface perturbations and velocities are small. Based on the ferrofluids physical properties, container dimensions and maximal velocities in our experiments, one can find Reynolds numbers ranging from 705 (FF1) to 434 (FF5). Thus, laminar ferrofluid flow is expected, allowing us to consider the Bernoulli equation. In low magnetic fields, when magnetization increases linearly with magnetic field, and if the magnetization and magnetic field are assumed to be parallel, the magnetic term takes the form

where \(\:{\chi\:}_{m}\) is the ferrofluid magnetic susceptibility. The magnetic field H(z) may be approximated by the following expression

with \(\:{H}_{0}\) denoting the magnetic field intensity at the bottom of the tank, \(\:z=-h\), and \(\:\alpha\:\) is a constant determined from experimental measurements. The kinematic and dynamic free surface boundary conditions are, respectively,

The other boundary conditions are at the sidewalls and bottom of the tank, where the normal component of the fluid vanishes. For more detailed theory of the ferrofluid liquid sloshing dynamics see the reference35.

In the horizontally excited upright cylindrical containers, the ferrofluids oscillate with rotational movement around the central axis of the cylindrical container. The ferrofluid surface displacement increases with increasing excitation frequency until it reaches resonance at which the free surface forms a collapse wave. Further increase of the excitation frequency causes a decrease in the free surface displacement. It was found that magnetic field shifts the resonance frequency to values higher than those in the absence of the magnetic field due to the associated increase in the effective gravity35,36. Moreover, in non-uniform magnetic fields, the sloshing constitutes a nonlinear response up to the third order perturbation in the vicinity of the first resonant frequency37. What makes our experiment more difficult for theoretical consideration is the horizontal position of the cylindrical vial. We chose that position with the aim to form the larger free ferrofluid surface area with the smaller ferrofluid volume. It is proven that the ferrofluid height does not play a crucial role in the induced voltage but the free surface does25. The greater the free surface, the greater the number of magnetic dipoles undergoing the sloshing and contributing to the time varying magnetic flux. However, horizontal cylinders partially filled with liquid are difficult to analyze to determine the free-liquid natural frequencies and mode shapes. The difficulty is associated with the fact that the walls are not straight and parallel to the axis of symmetry35. Various approaches were presented to solve the problem with restrictions. The natural frequency of the first transverse mode of liquid free surface in a half-filled horizontal cylinder can be determined by an energy approach35. In this approach, the kinetic energy of the fluid free surface experiencing small oscillations is

where R is the radius of the cylinder. The potential energy is given as follows

with \(\:\phi\:\) denoting the angle between the ferrofluid free surface and the horizontal. From this approach, equating the maximum kinetic energy to the maximum potential energy, and assuming sinusoidal oscillations, gives the first natural frequency

Following this simple restricted approach and substituting the radius of our cylinder (7.4 mm) in Eq. (9), leads the first natural frequency approx. 288 Hz. Taking into account that even though the real conditions with energy losses would cause lower resonant frequency, and that magnetic field shifts the resonance frequency to higher values, it seems to be not real to reach the resonance in our half-filled horizontal vial with the magnetized ferrofluid and with the available maximum frequency of the employed shaker (approx. 8 Hz, or 500 RPM).

The basic principle of the energy harvesting from the sloshing ferrofluids is then based on the Faraday’s law of electromagnetic induction. The sloshing of the magnetized ferrofluid generates a change in the magnetic flux, which induces a back electromotive force in the coil surrounding the ferrofluid vial. The magnetic flux ϕ passing through a given area, A, is defined as follows

where \(\:\alpha\:\) is the angle between the magnetic field lines and the normal to the area formed by the coil loop. Based on the Lenz’s law, the induced voltage known as the back electromotive force (emf) is proportional to the change of the flux and can be written as

with N denoting the numbers of the coil turns. It is therefore evident that, for a constant coil area, the electromotive force can be induced whether by changing the magnitude of the field B with time, or by varying the angle between the dipoles and the area vector A. The former is achieved by the bulk motion of the dipoles inside the vial, while the later can occur when the sloshing motion of the ferrofluid forces the dipoles to change their orientation27. More detailed theoretical description of the electromagnetic energy harvesting by ferrofluid sloshing, which can be a base for numerical simulations, was published in referenced publications28,30.

Results and discussion

It is evident from the theoretical consideration that the ferrofluid magnetization is a crucial property determining the vibration energy harvesting performance. The knowledge on the magnetization curves is therefore of high importance. In Fig. 4a, the isothermal magnetization curves measured on the studied ferrofluids are presented. In the low-field area, the curves exhibit a steep increase in magnetization with increasing magnetic field, reflecting the high initial magnetic susceptibility of the ferrofluids. The onset of the shoulder in the magnetization curves followed by the saturation reveals the state of the highest magnetic susceptibility of the ferrofluids. The low-field zoomed area in Fig. 4b shows that the state of the highest susceptibility occurs in magnetic fields close to those generated in our energy harvester setup (15 and 34 mT). It is also clear that the curves exhibit zero coercivity and remanence – the behavior characteristic for a superparamagnetic state of the nanoparticles. Any magnetic interactions and structural changes in the magnetic fields are therefore excluded. The different levels of the saturated magnetizations reflect the nanoparticle concentrations or the magnetic mass fractions present in the ferrofluids. The calculated magnetic mass fractions are presented in the bar graph of Fig. 4c.

The various magnetic mass fractions are also reflected in the different levels of the AC magnetic volume susceptibility spectra presented in Fig. 5. It is evident that the low-frequency real magnetic susceptibility increases with the magnetic mass fraction from 0.45 up 1.1. At low frequencies, the real susceptibility spectra exhibit quasi constant behavior with a slight decrease near the high-frequency limit. This is accompanied with near-zero imaginary susceptibility spectra. The behavior is associated with the well-relaxed magnetic moments of the ferrofluid nanoparticles when exposed to the low-frequency AC magnetic field (up to 10 kHz). Owing to the nanoparticle size, the mechanisms of the magnetic relaxations can follow the magnetic field frequencies with low magnetic losses38.

The relatively high values of the ferrofluids’ initial magnetic susceptibility give the assumption of the required ferrofluid magnetization under the action of the magnetic field from the permanent magnet in the energy harvester setup (Fig. 2). Based on Fig. 4(b), the ferrofluid magnetizations in the permanent magnet’s field may achieve the magnetizations from around 5 Am2/kg (FF1) to 12 Am2/kg (FF5). With this magnetization state, the vial containing the ferrofluid is exposed to the harmonic lateral motion with the controlled frequency. The resulting generated electromotive force (induced voltage) measured by the oscilloscope is presented in Fig. 6, as obtained for each magnetic field configuration. The left axis in the graphs represent the mean voltage values, which were calculated from the measured voltage values over 10 vibrations at a settled frequency. The x-axis represents the speed with increasing and decreasing values and the maximal speed in the middle. In this way, we present the induced voltage in the acceleration and deceleration mode in the same graphs. Figure 6a shows the dependence of the induced mean voltage on the shaker’s platform speed for a configuration with the single magnet on the top of the horizontal vial. For FF1, one can observe a rather smooth increase in the mean voltage with the increasing speed. At the maximal speed of 500 rpm, the mean voltage induced by FF1 reaches its maximum 1.63 mV. A similar mean voltage curve has been obtained during the deceleration from 500 to 0 rpm. With FF2, one also observes the increase in the mean voltage with the increasing speed. However, a turning point at 270 rpm is observed in the mean voltage curves during both, acceleration and deceleration mode. From that point, the mean voltage curve exhibits sharper rise with the increasing speed. Then, the maximal speed of the vial filled with FF2 yields the peak in the induced mean voltage of 2.25 mV. Similar mean voltage-speed dependences are found for FF3 and FF4 with the voltage maxima of 2.62 mV and 2.67 mV, respectively. With FF5, the mean voltage curve exhibits a local maximum at 180 rpm, observable in both, acceleration and deceleration mode. At 270 rpm, the mean voltage again steeply increases and at the maximal speed it reaches 3.01 mV.

The calculated mean voltage vs. vibrating platform speed. The vertical lines across the symbols are the error bars. The magnetic field configurations are as follows: the single magnet on the top of the horizontal vial providing the field intensity perpendicular to the axis of the vial motion and parallel with gravity (a), two magnets, one located at the bottom wall, one on the top wall of the vial, generating the field intensity perpendicular to the axis of the vial motion and parallel with gravity (b), two magnets on the side walls (one on the left and one on the right), generating the field intensity perpendicular to both, the axis of the vial motion and gravity (c), the single magnet attached to the vial side wall, providing the field intensity perpendicular to the axis of the vial motion and gravity (d), the single magnet attached to the bottom of the horizontal vial, generating the magnetic field parallel to the axis of the vial motion and perpendicular to gravity (e).

The graph in Fig. 6b shows the generated mean voltage in dependence on the speed of the vial with two magnets, one located at the bottom wall, and one on the top wall. The observed curve profiles exhibit more moderate increase with the speed, as compared to the previous case. In addition, the turning points resulting in the mean voltage jump and the maximal mean voltage value are found at higher speeds. While FF1 curve profile does not show an unambiguous turning point, for FF2, FF3, FF4, and FF5 it is clearly detected at 410, 410, 450, and 470 rpm, respectively. The maximal mean voltage values obtained for the particular ferrofluids at the maximal speed are 0.45, 0.56, 0.71, 0.69, and 0.77 mV, respectively.

In Fig. 6c, much narrower curve profiles with a reluctant mean voltage increase are found for the magnetic field generated by the two magnets placed on the side walls (one on the left and one on the right). The mean voltage increases smoothly following an exponential-like behavior for each ferrofluid without any turning points. The maximal mean voltages reached at the maximal speed are 0.32, 0.35, 0.38, 0.4, 0.43 mV for FF1, FF2, FF3, FF4, and FF5, respectively.

On the other hand, with the single magnet attached to the vial side wall, one finds a remarkably wider mean voltage-speed window, as presented in Fig. 6d. The curve profiles exhibit the turning points followed by a steep increase already at the speed of 80 rpm. Then, the increasing curve is accompanied with a shoulder appearing at 150 rpm for FF1, 180 rpm for FF2 and FF3, 200 rpm for FF4, and 210 rpm for FF5.

The slightest differences in the induced mean voltage by the various ferrofluids are found in the magnetic field generated by the single magnet attached to the bottom of the horizontal vial, as presented in Fig. 6e. The graph shows a continuous exponential-like increase in the mean voltage with increasing speed for all ferrofluids. However, in this magnetic field configuration, the maximal induced voltage doesn’t follow the ferrofluid magnetic mass fraction, as it does in the previous cases, but the maximal value of 0.72 mV is found for FF1 with the lowest magnetic mass fraction. With the higher magnetic mass fractions of FF2, FF3, FF4, and FF5, we have obtained lower mean voltages with the values 0.71, 0.62, 0.69, and 0.62 mV, respectively.

It is evident from Fig. 6 that the dependence of the mean induced voltage on the speed is identical for measurements in acceleration and deceleration mode and this behavior holds for each magnetic field configuration and each ferrofluid. It can be therefore deduced that the magnetized ferrofluid sloshing does not induce any nanoparticle interaction and aggregation, which could certainly influence the induced voltage. Finally, it is supposed that the occurred local maxima (sharp jumps in the mean voltage) are associated with an internal resonance between two vibration modes34.

In Fig. 7a, we plot the dependence of the maximal mean voltage (the maxima found in Fig. 6) on the magnetization of saturation of the ferrofluids under various magnetic field configurations. It is evident that the mean voltage maximum follows a linear increase with increasing magnetization of saturation for magnetic field configurations (a), (b), (c), (d), while a slight decrease is observed for the field configuration (e). Based on the maximal mean voltage values, we have calculated the maximal mean power generated by the magnetized ferrofluid sloshing according to the following formula

where R is 50 Ω resistance of the resistor connected in series with the copper coil. The calculated maximal mean power in dependence on the ferrofluid magnetization of saturation is presented in Fig. 7b. We have applied a linear fitting function \(\:y=a+bx\) on the presented data, and found an intercept and a slope of the plotted mean power—magnetization of saturation dependence. The obtained parameters are presented in Table 2. The fitting confirms the negative slope of the behavior in the magnetic field configuration E, and the positive slope in all other configurations. According to Fig. 7, it is evident that the most effective magnetic field configuration is the one with the single magnet attached to the vial side wall, providing the field intensity perpendicular to the axis of the vial motion and gravity (D). In this case, the maximal mean power achieved with the ferrofluid FF5 is 232.56 nW. With the single magnet on the top of the horizontal vial generating the field intensity perpendicular to the axis of the vial motion and parallel with gravity (A), the maximal mean power with FF5 is 181.68 nW. Remarkably lower mean power was generated in the field of the two magnets located at the bottom and the top wall of the vial, generating the field intensity perpendicular to the axis of the vial motion and parallel with gravity (B). In this case, the maximal mean power with FF5 is 11.91 nW. The lowest effectivity is found in the field of magnets attached to the side walls with the field intensity perpendicular to both, the axis of the vial motion and gravity (C). The maximal mean power achieved in this case with FF5 is 3.15 nW. Finally, the magnetic field from the single magnet attached to the bottom of the horizontal vial, generating the magnetic field parallel to the axis of the vial motion and perpendicular to gravity (E) is the only case when the maximal mean power (10.43 nW) was achieved with the ferrofluid of the lowest magnetization of saturation FF1, as the higher magnetizations cause the decrease in the mean power.

The maximal mean voltage (a) and maximal mean power with a 50 Ω load (b) dependence on the ferrofluid magnetization of saturation. The lines represent the fitting function \(\:y=a+bx\). The legend A, B, C, D, E refers to the magnetic field configurations explained in the caption of Fig. 6a–e.

It is therefore found that the most effective magnetic field configuration for the vibrational ferrofluid energy harvesting is the one with the single magnet attached to the vial side wall, providing the field intensity perpendicular to the axis of the vial motion and gravity (D). Under these conditions, the widest mean voltage-speed window and the highest mean power are observed with all ferrofluid samples. The wide voltage-speed window reflects the wide response range of excitation frequencies with an apparent modal frequency occurring above 150 rpm (Fig. 6d). The continuous increase in the mean voltage—frequency response implies a large number of closely spaced modal frequencies of the ferrofluids in the lying vial. Under the set magnetic field configuration, the magnetic field interacts with the magnetic moments of the nanoparticles and orients them along the field intensity vector. Then, the ferrofluid sloshing due to the lateral vial motion directed perpendicularly to the field intensity forces the magnetic moments to fluctuate around the field intensity vector, so creating the time-varying magnetic flux and inducing the voltage in the coil. Very similar quantitative performance of the energy harvesting with slightly narrower mean voltage-speed window is achieved in the magnetic field configuration with the single magnet on the top of the horizontal vial (Fig. 6a). In this case the ferrofluids are also exposed to the field of 15 mT acting perpendicularly to the vial motion. It is clear that the perpendicular arrangement of the oriented magnetic moments and the direction of the mechanical motion create right conditions for magnetic moments harmonic oscillation. Thus, the magnetic field orientation is a crucial parameter determining the energy harvesting performance. Moreover, the different magnetic field configurations provide different demagnetizing effects, which can have non-negligible impact on the total ferrofluid magnetization and finally on the voltage generation. The local magnetic field in the vial differs from the applied magnetic field by a demagnetizing field of the polarized ferrofluid. As the demagnetizing effects are shape-dependent, one admits that in configurations with the field intensity perpendicular to the vial and the sloshing motion, the demagnetizing effects are certainly stronger than in the configuration with the field acting along the vial. Then, the total magnetic field induction (or field intensity) determines the performance too. Under the stronger magnetic field generated by the two magnets, acting perpendicular to the axis of the vial motion and parallel or perpendicular to gravity (B or C), we observe remarkably lower energy harvesting performance (Fig. 6b and c). The mean voltage-speed windows are narrower and distinguished modal frequencies are seen for the former case (field parallel with gravity) appearing around 410 rpm. The narrow mean voltage-speed window and significantly lower mean power generated by the ferrofluids in theses magnetic fields are associated with the reduced ferrofluid sloshing ability. It is due to the stronger magnetic interactions of the magnetic moments with the field, resulting in the well-known magneto-viscous effect39. As a result, higher kinetic energy achieved at higher motion speeds is required to deflect the ferrofluid surface. One order of magnitude lower mean voltage induced in the field of the two magnets implies a smaller time change in the magnetic flux due to the smaller oscillation range of the magnetic moments hindered by the stronger magnetic interactions with the magnetic field. Similarly, the energy harvesting effect becomes weak when the ferrofluids are attracted to the single magnet attached to the bottom of the vial. In this case, the most effective energy harvesting is achieved with the ferrofluid of the lowest magnetization of saturation FF1. The induced maximal mean voltage decreases with the higher magnetizations of saturation. This effect is caused by the stronger magnetic interaction between the magnet and ferrofluids, leading to a greater measure of immobilization of the ferrofluid. On the other hand, when the ferrofluid is attached to the bottom of the horizontally lying vial (the case shown in Fig. 2), a smaller free surface undergoing sloshing is available. One understands, that the mechanical excitation of the smaller free area (ferrofluid surface) of magnetic moments provides smaller magnetic flux change.

In order to prove the magneto-viscous behavior of the studied ferrofluids, we have conducted measurements of viscosity in the magnetic fields present in the energy harvesting experiments, i.e. 15 mT, 34 mT and in addition in the field of 54 mT. The measurements were performed using a rotational rheometer MCR 502 from Anton Paar with a magnetorheological cell (MRD 170/1T) and a TwinGap measuring system (TG16/MRD/TI), consisting of two parallel plates with a diameter of 16 mm, separated by a gap of 0.328 mm. The viscosity of the ferrofluids and the base oil were determined in the shear rate range from 10 to 1000 s− 1 at room temperature (− 23 °C). The magnetic field is oriented perpendicularly to the measuring gap and the viscosity flow curves were recorded at a constant magnetic field. The obtained results are presented in Fig. 8.

It is evident from Fig. 8a that the ferrofluids and the base oil exhibit Newtonian behavior, as their viscosity is independent on the applied shear rate. Upon application of the magnetic field on the ferrofluid samples, the magneto-viscous behavior and shear thinning effect are observed, see Fig. 8b–f. The action of 15 mT and 34 mT field on FF1 causes the increase in the ferrofluid viscosity by about 28% and 107%, respectively, as determined at shear rate of 17 s− 1. A similar magneto-viscous effect is observed for ferrofluids of higher magnetization of saturation. The viscosity of FF2 increases by 43% and 143% upon application of 15 mT and 34 mT field, respectively. 44% and 124% increase in viscosity are found for FF3. 55% increase in viscosity is detected for FF4 and FF5 under the action of 15 mT, while 105% and 91% viscosity increase exhibit FF4 and FF5 in 34 mT magnetic field.

Conclusion

Five ferrofluid samples with different magnetizations of saturation and magnetic susceptibilities were subjected to vibrational energy harvesting study. Electrical voltage induction by the sloshing of the ferrofluids in the moving horizontal vial was investigated under various magnetic field configurations. Based on the conducted experiments it is found that the most effective energy harvesting is achieved in the magnetic field of 15 mT generated by the single magnet attached to the vial side wall, providing the field intensity perpendicular to the axis of the vial motion and gravity. The maximal mean power achieved with the ferrofluid FF5 is 232.56 nW. In conversion, it is 0.4 nW per single coil turn and 93 nW per milliliter of the ferrofluid. The increasing magnetization of saturation yields the increase in the harvested power except of the ferrofluid sloshing in the magnetic field from the single magnet attached to the bottom of the horizontal vial, when the opposite effect is observed. The dependence of the mean induced voltage on the vial oscillation frequency is identical for measurements in acceleration and deceleration mode and this behavior holds for each magnetic field configuration and each ferrofluid. The obtained energy harvesting results may be considered when designing future ferrofluid vibration energy harvesters for various mechanical excitations with changing directions of motion in regard to the magnetic field induction.

Data availability

Data sets generated during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Ali, A. et al. Recent progress in energy harvesting systems for wearable technology. Energy Strateg. Rev. 49, 101124 (2023).

Kulandaivel, A. et al. Advances in ferrofluid-based triboelectric nanogenerators: Design, performance, and prospects for energy harvesting applications. Nano Energy 120, 109110 (2024).

Cao, X. et al. Multidiscipline applications of triboelectric nanogenerators for the intelligent era of internet of things. Nano-Micro Lett. 15, 1–41 (2022).

Jia, S. Z. Waste energy harvesting in sustainable manufacturing. Sustain. Manuf. Process. 2023, 231–256. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-323-99990-8.00014-X (2023).

Xu, C., Song, Y., Han, M. & Zhang, H. Portable and wearable self-powered systems based on emerging energy harvesting technology. Microsyst. Nanoeng. 7, 1–14 (2021).

Kim, H. et al. A molybdenum-disulfide nanocomposite film-based stretchable triboelectric nanogenerator for wearable biomechanical energy harvesting and self-powered human motion monitoring. Chem. Eng. J. 491, 151980 (2024).

Li, C. et al. Gas-driven triboelectric nanogenerator for mechanical energy harvesting and displacement monitoring. Nano Energy 126, 109681 (2024).

Yang, R., Yang, M., Fan, P., Lu, T. & Wang, T. A new flexible electrostatic generator using dielectric fluid. J. Appl. Phys. 134, 105001 (2023).

Zou, J. et al. A walking energy harvesting device based on miniature water turbine. J. Appl. Phys. 135, 25002 (2024).

Liang, S. et al. Liquid metal flexible wearable triboelectric nanogenerator device for human energy harvesting. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 141, e55092 (2024).

Yuan, Z. & Guo, L. Recent advances in solid–liquid triboelectric nanogenerator technologies, affecting factors, and applications. Sci. Rep. 14, 1–22 (2024).

Wang, X. et al. Mechanical vibration energy harvesting and vibration monitoring based on triboelectric nanogenerators. Energy Technol. 12, 2300931 (2024).

Shan, C., Li, K., Cheng, Y. & Hu, C. Harvesting environment mechanical energy by direct current triboelectric nanogenerators. Nano-Micro Lett. 15, 1–24 (2023).

Rosensweig, R. E. Ferrohydrodynamics (Dover Publications, New York, 2013).

Chen, Y. et al. Characteristic of solid-ferrofluid triboelectric nanogenerator for ultra-low-frequency vibration energy harvesting. Nano Energy 111, 108395 (2023).

Yang, X., Chen, Y., Zhang, Y. & Yang, W. Effect of magnetic field on output performance of magnetic liquid vibration energy harvester. COMPEL Int J. Comput. Math. Electr. Electron. Eng. 42, 38–47 (2023).

Jing, D. et al. Design and test of liquid sloshing piezoelectric energy harvester. Adv. Mech. Eng. 16, 168 (2024).

Chen, J. et al. The exploration of multifunctional liquid robotics with ferrofluids: Fabrication, control, operation and sensing. Nano Energy 131, 110169 (2024).

El-hami, M. et al. Design and fabrication of a new vibration-based electromechanical power generator. Sens Actuators A Phys. 92, 335–342 (2001).

Yu, J. et al. Electromagnetic vibration energy harvester using magnetic fluid as lubricant and liquid spring. Energy Convers. Manag. 286, 117030 (2023).

Zhang, X., Li, G., Wang, W. & Su, S. Study on the energy conversion mechanism and working characteristics of a new energy harvester with magnetic liquid. Sens. Actuators A Phys. 359, 114409 (2023).

Yu, J. et al. A nonlinear electromagnetic vibration energy harvester lubricated by magnetic fluid for low-frequency vibration. Appl. Phys. Lett. 123, 043901 (2023).

Wang, Y. et al. Vibration energy harvester with low resonant frequency based on flexible coil and liquid spring. Appl. Phys. Lett. 109, 203901 (2016).

Wu, S., Luk, P. C. K., Li, C., Zhao, X. & Jiao, Z. Investigation of an electromagnetic wearable resonance kinetic energy harvester with ferrofluid. IEEE Trans. Magn. 53, 1–6 (2017).

Bibo, A., Masana, R., King, A., Li, G. & Daqaq, M. F. Electromagnetic ferrofluid-based energy harvester. Phys. Lett. A 376, 2163–2166 (2012).

Oh, D. W., Sohn, D. Y., Byun, D. G. & Kim, Y. S. Analysis of electromotive force characteristics and device implementation for ferrofluid based energy harvesting system. In 2014 17th International Conference on Electrical Machines and Systems ICEMS 2014 2033–2038 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1109/ICEMS.2014.7013820

Alazemi, S. F., Bibo, A. & Daqaq, M. F. A ferrofluid-based energy harvester: An experimental investigation involving internally-resonant sloshing modes. Eur. Phys. J. Spec. Top. 224, 2993–3004 (2015).

Alazmi, S., Xu, Y. & Daqaq, M. F. Harvesting energy from the sloshing motion of ferrofluids in an externally excited container: Analytical modeling and experimental validation. Phys. Fluids 28, 77101 (2016).

Liu, Q., Alazemi, S. F., Daqaq, M. F. & Li, G. A ferrofluid based energy harvester: Computational modeling, analysis, and experimental validation. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 449, 105–118 (2018).

Liu, Q., Daqaq, M. F. & Li, G. Performance Analysis of a ferrofluid-based electromagnetic energy harvester. IEEE Trans. Magn. 54, 1–14 (2018).

Vékás, L., Bica, D. & Avdeev, M. V. Magnetic nanoparticles and concentrated magnetic nanofluids: Synthesis, properties and some applications. China Particuol 5, 43–49 (2007).

Paulovičová, K. et al. Nanofluid based on new generation transformer oil: Synthesis and flow properties. Acta Phys. Pol. A 137, 908–910 (2020).

Rozynek, Z. et al. Structuring from nanoparticles in oil-based ferrofluids. Eur. Phys. J. E 34, 1–8 (2011).

Karban, P., Pánek, D. & Kaska, J. Open-source platform for simulation of physical fields: Agros. J. Comput. Appl. Math. 465, 116589 (2025).

Ibrahim, R. A. Liquid sloshing dynamics: Theory and applications. Liq. Sloshing Dyn. 9780521838856, 1–948 (2005).

Sawada, T., Ohira, Y. & Houda, H. Sloshing motion of a magnetic fluid in a cylindrical container due to horizontal oscillation. Energy Convers. Manag. 43, 299–308 (2002).

Sawada, T., Tanahashi, T. & Kikura, H. Kinematic characteristics of magnetic fluid sloshing in a rectangular container subject to non-uniform magnetic fields. Exp. Fluids 26, 215–221 (1999).

Rajnak, M. et al. Dynamic magnetic response of ferrofluids under a static electric field. Phys. Fluids 33, 82006 (2021).

Odenbach, S. & Thurm, S. Magnetoviscous Effects in Ferrofluids 185–201 (Springer, Cham, 2002). https://doi.org/10.1007/3-540-45646-5_10.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the Slovak Academy of Sciences and Ministry of Education and Slovak Research and Development Agency for funding this research.

Funding

This research was funded by Slovak Academy of Sciences and Ministry of Education in the framework of projects VEGA 2/0029/24, VEGA 1/0380/24, VEGA 1/0353/22, and Slovak Research and Development Agency under the contract No. APVV-22-0115.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.R. wrote the main manuscript text, conducted and analyzed magnetic measurements and co-constructed the energy harvester, J.K. co-constructed the energy harvester, conducted the energy harvesting experiment and prepared the graphs, K. P. prepared the ferrofluids and conducted viscosity measurements, J. T. conducted viscosity measurements and prepared the viscosity graphs, J.K. and R.C. validated the experimental analysis. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Rajnak, M., Kurimsky, J., Paulovicova, K. et al. Vibration energy harvesting by ferrofluids in external magnetic fields. Sci Rep 15, 26701 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-12490-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-12490-w