Abstract

Fracture healing is a complex biological process. This study aimed to investigate the key molecules involved in fracture healing and their potential competing endogenous RNA (ceRNA) regulatory mechanisms within the first 28 days post-fracture using bioinformatics methods. The experiment was conducted on 15 adult male SD rats, with tibia callus tissue samples collected at days 0, 3, 7, 14, and 28 (n = 3) post-fracture. RNA-Seq was used for high-throughput transcriptome sequencing, followed by differential expression analysis to identify differentially expressed genes (DEGs), long non-coding RNA (DELs), and microRNA (DEMs) at different stages. Protein-protein interaction (PPI) networks were constructed using the STRING database and visualized with Cytoscape. GO and KEGG enrichment analyses were performed to explore potential biological mechanisms. miRNA-mRNA interactions were predicted using TargetScan, miRWalk, and miRDB, while RNA22 v2 was used for lncRNA-miRNA interactions. These interactions were integrated into ceRNA networks. Finally, qRT-PCR validated key molecules within the ceRNA network. We identified 4,997 DEGs, 315 DELs, and 89 DEMs at day 3; 5,087 DEGs, 300 DELs, and 84 DEMs at day 7; 3,073 DEGs, 235 DELs, and 68 DEMs at day 14; and 2,609 DEGs, 197 DELs, and 90 DEMs at day 28. Further analysis revealed hub osteogenic genes and their ceRNA regulatory networks at each time point. The networks consisted of 2 mRNAs, 3 miRNAs, and 9 lncRNAs at day 3; 2 mRNAs, 3 miRNAs, and 8 lncRNAs at days 7 and 14; and 1 mRNA, 3 miRNAs, and 10 lncRNAs at day 28. We validated two key lncRNAs (AABR07030366.1 and AABR07057997.1) along with their interacting miRNAs and mRNAs: rno-miR-9a-5p/Col9a1 (day 3), rno-miR-181c-5p/Comp (day 7), rno-miR-423-5p/Col1a1 (day 14), and rno-miR-185-5p/Ctsk (day 28). In summary, our study leveraged bioinformatics to construct ceRNA networks involved in osteogenesis post-fracture, offering insights into their dynamic regulatory role in healing and underlying molecular mechanisms.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Fractures are among the most common traumatic injuries worldwide. While traditional treatments, such as surgery and immobilization, have been effective in promoting healing, a significant number of patients still experience slow recovery. Approximately 10–15% of fractures result in delayed healing or nonunion1, which can lead to chronic pain, functional impairment, psychological distress, and other complications2. These issues not only reduce patients’ quality of life but also place a significant burden on healthcare systems.

Although most RNA transcripts in the mammalian genome do not encode proteins, with protein-coding RNA accounting for less than 2%, increasing evidence suggests that non-coding RNA (ncRNA) plays crucial regulatory and functional roles in the body3,4. The competing endogenous RNA (ceRNA) mechanism suggests that RNAs with miRNA-binding sites can regulate each other by competing for shared miRNAs5. Long non-coding RNA (lncRNA), which have abundant miRNA-binding sites, are ideal candidates for studying ceRNA.

LncRNA can bind to and sequester microRNAs (miRNAs), forming lncRNA-miRNA complexes. This reduces the availability of miRNAs in the cytoplasm, leading to decreased miRNA-mediated degradation and inhibition of mRNA expression. In the ceRNA network, both lncRNA and mRNA compete for the same miRNA binding sites, influencing each other’s expression and function. Recent studies have confirmed the role of lncRNA-mediated ceRNA mechanisms in the regulation of fracture healing, osteoporosis, and osteoblast differentiation6,7,8.

The early phase of bone fracture healing is critical in determining the overall recovery outcome. Bone fracture healing progresses through three major stages: inflammation, endochondral bone formation, and coupled remodeling9. In a rat fracture model, intramembranous ossification initiates the earliest, providing mechanical support by day 3. This process gradually transitions to endochondral ossification, becoming the dominant mode by day 1110. Histologically, the early inflammatory phase is marked by hematoma formation, tissue necrosis, infiltration of inflammatory cells, and periosteal reactive proliferation11. By day 14, fibrous callus predominates, interspersed with areas of cartilage12. By day 21, both cartilage and woven bone can be observed along the fracture line13. Between days 21 and 28, the volume of highly mineralized bone increases as more cartilage is replaced by woven bone14. By day 28, the fracture site shows significant callus bridging the gap, though the fracture line remains visible, indicating incomplete healing15,16. During weeks 4 to 7, the amount of newly formed bone increases, bone density rises, and trabecular thickening suggests the transition from woven to lamellar bone. By weeks 7 to 8, the fracture gap is fully bridged with no residual cartilage, signaling the end of the healing process11,16,17.

Among various fracture sites, the tibia is especially prone to impaired healing due to its superficial location, limited soft tissue coverage, and inadequate blood supply18,19. These factors contribute to a higher incidence of delayed union or nonunion in tibial fractures compared to other long bones. Therefore, the tibial fracture model was chosen in this study to better replicate the clinical challenges associated with compromised bone healing. In this study, we collected tibia callus tissue samples at multiple time points (days 0, 3, 7, 14, and 28), with day 0 serving as the control group. Days 3, 7, 14, and 28 correspond to different phases of fracture healing. RNA-seq was performed to identify the most significantly DEGs, DELs, DEMs at each phase. We predicted the lncRNA-miRNA and miRNA-mRNA interactions and constructed a ceRNA regulatory network. This approach not only provides a deeper understanding of the dynamic molecular interactions throughout the healing process but also helps identify potential therapeutic targets, offering valuable insights for improving fracture treatment strategies. The overall procedure of this study is illustrated by a flowchart (Fig. 1).

Methods

Animals

Fifteen adult male Sprague-Dawley (SD) rats, aged 6 to 8 weeks and weighing 250–300 g, were obtained from Beijing Vital River Laboratory Animal Technology Co., Ltd. The animals were randomly assigned to five groups (n = 3 per group) and housed under a 12-hour light/dark cycle with unrestricted access to food and water. This study’s experimental procedures were approved by the Animal Ethics Committee of Peking University People’s Hospital (Approval No. 2024PHE029).

Operation and tissue sampling

Rats were anesthetized using 2.5% isoflurane with oxygen (RWD, China). A 2 cm incision was made at the tibial tuberosity, and a dental drill was used to create a hole 5 mm above the tibial tuberosity. Then, an intramedullary pin with a 0.8 mm diameter (Yutong, China) was inserted into the bone marrow cavity. The tibia was fractured 5 mm below the tibial tuberosity using three-point bending pliers, ensuring the intramedullary pin remained intact and the wound was sutured layer by layer. Postoperative verification of intramedullary pin placement accuracy and fracture was performed using the DR-60 A X-ray imaging system (SHINOVA, China). The rats were humanely euthanized via CO2 inhalation at days 0, 3, 7, 14, and 28 after the operation. Animals were placed in a transparent, gradually filled euthanasia chamber connected to a regulated compressed CO2 source, remaining in the chamber for at least 2 min after cessation of breathing and apparent loss of consciousness. Bone callus tissue within 2 mm of the fracture line was collected from the injured limb for further analysis.

RNA extraction and sample detection

Callus samples were immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen within 3 min post-excision, then the frozen tissue was pulverized and dissolved in TRIzol (Invitrogen, USA) for RNA extraction. After mixing the TRIzol solution, it was incubated for 5 min. Chloroform was then added, thoroughly mixed, and incubated for an additional 3 min. The mixture was centrifuged at 12,000 rpm for 15 min at 4 °C. The upper aqueous phase was carefully transferred. An equal volume of isopropanol was added to the aqueous phase. After mixing, it was incubated at room temperature for 10 min. The solution was centrifuged again at 12,000 rpm for 10 min at 4 °C. The supernatant was discarded, and 1 mL of 75% ethanol at 4 °C was added. It was centrifuged at 7,500 rpm for 5 min at 4 °C. The RNA was dried at room temperature for 30 min and then dissolved in RNase-free water (Invitrogen, USA). The RNA solution was stored at -80 °C. Quality control was performed to ensure RNA integrity, including assessing degradation and contamination by agarose gel electrophoresis, determining purity (OD260/280) using Nanodrop, quantifying concentration with Qubit 2.0, and evaluating RNA integrity with the Agilent 2100 (Agilent Technologies, USA). The small RNA-seq and LncRNA-seq quality test results are shown in supplementary file 1.

Library construction and sequencing

After confirming sample quality, we first proceeded with mRNA and lncRNA library construction and sequencing. Ribosomal RNA was removed from the total RNA, and the remaining RNA was fragmented into 250–300 bp segments. These RNA fragments served as templates for synthesizing the first strand of cDNA using random oligonucleotide primers. The second strand of cDNA was then synthesized using dNTPs (dUTP, dATP, dGTP, and dCTP). The resulting double-stranded cDNA underwent end repair, addition of an A-tail, and sequencing adapter ligation. AMPure XP beads were used to select cDNA fragments approximately 350–400 bp in length. The second cDNA strand containing U was degraded using USER enzyme, followed by PCR amplification to complete the library preparation. Once the library was constructed, it was quantified using Qubit 2.0 and diluted to a concentration of 1.5 ng/µl. The insert size was checked using the Agilent 2100 to ensure library quality. After passing quality control, libraries were pooled based on effective concentration and required data output for high-throughput sequencing using Illumina PE150 (Illumina, USA).

Then, the miRNA library was prepared using the Small RNA Sample Pre Kit. Total RNA served as the starting material, and adaptors were ligated to both ends of the small RNA. Reverse transcription was then performed to synthesize cDNA. This was followed by PCR amplification and separation of target DNA fragments using PAGE gel electrophoresis. The desired DNA bands were excised and purified to construct the cDNA library. After library construction, initial quantification was performed with a Qubit 2.0 fluorometer, and the library was diluted to a concentration of 1 ng/µL. The insert size of the library was then assessed using Agilent 2100 bioanalyzer. Finally, libraries were pooled according to their effective concentrations and sequencing data requirements, followed by sequencing by Illumina SE50.

Comparison and quantification of RNA

The filtered data files were aligned to the reference genome for mRNA and lncRNA identification using BWA v0.7.17. The reference genome was obtained from the comprehensive database (rattus_norvegicus_Ensembl_97). After alignment, the resulting SAM files were converted into BAM format using SAMtools v1.16.1, followed by sorting and indexing of the read sequences. Subsequently, featureCounts v2.0.1 was used to count the read assignments to specific features, with SAM/BAM files and annotated files containing chromosomal coordinates as inputs.

For small RNA sequencing data and miRNA identification, SPORTS v1.1 was employed. Adapter sequences were removed, and sequences outside the defined length range or containing non-canonical bases (ATUCG) were discarded to produce clean reads. These processed reads were mapped sequentially to reference genomes and databases such as miRBase.

Screening of DEGs, DELs, DEMs

Raw read counts were obtained from RNA-Seq data and analyzed using DESeq2 v.1.34.0, and differential expression analysis was performed based on a negative binomial distribution model. To control for multiple testing, the Benjamini-Hochberg false discovery rate (FDR) correction was applied, with an adjusted p-value threshold of < 0.05 considered statistically significant. Given the large number of DEGs identified, more stringent criteria were applied to ensure the accuracy of DEG selection, with p-value < 0.01 and |fold change (FC)| ≥ 2 used as thresholds. For differentially expressed lncRNAs (DELs) and differentially expressed miRNAs (DEMs), the selection criteria were set as p-value < 0.05 and |FC| ≥ 2. The whole lists of DEGs, DELs, DEMs are accessed in supplementary file 2–4.

Protein–protein interaction (PPI) network and hub osteogenic genes

The protein-protein interaction (PPI) data of DEGs set were obtained from the STRING database v.12.0. In the PPI analysis, we applied 0.4 as the interaction score threshold, interactions with a score greater than threshold were selected as inclusion criteria. And we excluded the disconnected nodes from the final analysis. Then, the PPI data downloaded from STRING were imported into Cytoscape v.3.10.2 software. The CytoHubba plugin was installed in Cytoscape, and the maximum clique centrality (MCC) scores were selected as the criterion for hub genes screening. Compared to degree scores, the MCC scores provide a more accurate representation of a gene’s central role within a protein-protein interaction (PPI) network, as it accounts for the density of connections between the gene and its neighboring nodes. A higher MCC score indicates that the gene is positioned at the center of multiple large clusters, reflecting its high connectivity and significance within the network. At each time point, the top 5% DEGs ranked by MCC scores were identified as hub genes. To further refine our analysis, we selected the top 20 hub genes at each time point and visualized them using STRING. From these, we identified the hub genes most involved in the top five significantly enriched Gene Ontology Biological Processes directly related to osteogenesis. These genes were designated as the hub osteogenic genes for the respective time points. Finally, PPI networks were constructed to visualize the interactions between hub genes and hub osteogenic genes.

Kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes (KEGG) and gene ontology (GO) analysis

Functional enrichment analysis for hub genes was performed using the clusterProfiler package (v.4.2.2) in R and the rat gene information was annotated through the org.Rn.eg.db database (v.3.14.0). The background gene set used for enrichment analysis included all annotated genes in Rattus norvegicus provided by the org.Rn.eg.db annotation package. GO analysis was then conducted, covering three key categories: Biological Processes (BP), Molecular Functions (MF), and Cellular Components (CC). For each time point, the top 10 most significantly enriched terms were selected for further clustering analysis. We also performed pathway enrichment analysis using the KEGG. Enriched pathways with p-value < 0.05 at each time point were chosen for clustering. To control for multiple testing, the FDR correction was applied, and terms or pathways with an adjusted p-value < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. All enrichment results were visualized using the ggplot2 package in R to ensure a clear presentation.

RNA-RNA interaction and ceRNA network construction

TargetScan, miRWalk, and miRDB were chosen for miRNA-mRNA interaction prediction because they are among the most widely used and complementary resources. By intersecting predictions from all three platforms, we aimed to reduce false positives and ensure higher confidence in the identified miRNA-mRNA pairs. Only miRNAs that were predicted to target hub osteogenic genes by all three platforms and had a context + + score percentile greater than 90 in TargetScan were selected for further analysis (supplementary file 5). Next, the miRNA intersection was compared with all downregulated DEMs identified at the corresponding time point to predict potential miRNA-mRNA interactions. Given that most of the identified DELs have not been systematically studied, we selected the RNA22 v2 platform to predict miRNA-lncRNA interactions. This tool offers the advantage of first identifying potential miRNA binding sites within the RNA sequence and then determining the corresponding miRNAs. Its predictive performance has been demonstrated to be reliable20. We then input the selected miRNAs along with the top 10 upregulated DELs from the same time point, ranked by log2FC, into the RNA22 v2 platform. Using a p-value threshold of < 0.01, we filtered the results to identify potential miRNA-lncRNA interactions. Finally, the predicted interactions were imported into Cytoscape to construct the complete ceRNA network.

Quantitative real-time PCR

Total RNA was extracted, and its purity and integrity were assessed using a NanoDrop 2000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) and an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies, USA). Only RNA samples with an A260/A280 ratio between 1.8 and 2.0 and an RNA integrity number (RIN) of 7 or higher were used for further analysis. The RNA solution was gradually thawed on ice prior to use.

qRT-PCR reactions were performed using the HiScript II One Step qRT-PCR SYBR Green Kit (Vazyme, China) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Each reaction mixture was prepared in a final volume of 20 µl, containing as follows: 10 µl of 2× One Step SYBR Green, 1 µl of One Step SYBR Green Enzyme Mix, 0.4 µl each of forward and reverse primers (10 µM), 500ng of template RNA, and RNase-free water. The qRT-PCR reaction was carried out using the Bio-Rad iQTM5 system (Bio-Rad, Canada) with the following thermal cycling conditions: reverse transcription at 50 °C for 15 min, initial denaturation at 95 °C for 3 min, followed by 40 cycles of amplification consisting of 95 °C for 10 s, 60 °C for 30 s, and 72 °C for 30 s. GAPDH was used as the internal control for lncRNA and mRNA, while U6 served as the internal control for miRNA. Relative gene expression was calculated using the 2-ΔΔCt method. All primer sequences used in this study are listed in the supplementary file 6.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses and visualizations were conducted using GraphPad Prism 9.5 (GraphPad Software, USA). Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation, and comparisons were made using Student’s t-test, while comparisons involving multiple groups were analyzed using one-way or two-way ANOVA followed by post hoc tests when necessary. A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All experiments were repeated at least three times to ensure reproducibility.

Result

Fracture model construction and validation

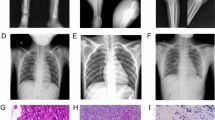

This section describes the process of constructing the fracture model and its validation through imaging techniques. The tibia was first exposed, and a hole was drilled above the tibial tuberosity to reach the medullary cavity. An intramedullary pin was then inserted to stabilize the bone (Fig. 2A). Following the induction of the fracture, the excess length of the pin was trimmed, followed by suturing the wound in layers (Fig. 2B). Postoperative X-ray imaging was performed to confirm the correct of the intramedullary pin placement and to validate the success of the fracture model (Fig. 2C).

Differential expression analysis

The volcano plots revealed significant changes in expression at each time point compared to the control group (Fig. 3A). For DEGs, there were 2,111 upregulated and 2,886 downregulated genes at day 3, 2,332 upregulated and 2,755 downregulated at day 7, 1,779 upregulated and 1,924 downregulated at day 14, 1,413 upregulated and 1,196 downregulated at day 28. For DELs, there were 132 upregulated and 183 downregulated lncRNAs at day 3, 130 upregulated and 170 downregulated at day 7, 129 upregulated and 106 downregulated at day 14, and 120 upregulated and 77 downregulated at day 28. For DEMs, there were 45 upregulated and 44 downregulated miRNAs at day 3, 44 upregulated and 40 downregulated at day 7, 32 upregulated and 36 downregulated at day 14, and 51 upregulated and 39 downregulated at day 28. The clustering heatmap highlighted the dynamic changes in expression profiles over the course of fracture healing (Fig. 3B). Venn maps identified the overlapping upregulated DEGs, DELs and downregulated DEMs across the four time points, revealing commonalities in their expression patterns (Fig. 3C). These results underscore the distinct expression patterns underlying different phases of the healing process. Our findings revealed that during the 28-day healing period in rats, the overall number of DEGs, DELs, and DEMs generally decreased over time. The expression profiles across different phases were closely interconnected. Most of these molecules were differentially expressed at two or more time points.

PPI network of hub genes and hub osteogenic genes

To reveal the interaction of proteins and capture the participation of hub genes in key biological processes across different time points, we made the PPI network analysis. Figure 4 shows the gene nodes and their interactions within the PPI networks of hub genes. At day 3, the network contained 61 nodes and 254 edges; at day 7, 55 nodes and 248 edges; at day 14, 42 nodes and 148 edges; and at day 28, 55 nodes and 153 edges. We next screened the hub osteogenic genes and visually highlighted their involvement in the top five GO-BP items directly related to osteogenesis at each time point (Fig. 5). At day 3, the top five items were “bone mineralization”, “endochondral bone morphogenesis”, “bone morphogenesis”, “chondrocyte differentiation”, and “cartilage development”. Col3a1 and Col9a1 were identified as hub osteogenic genes. At day 7, the top five items included “positive regulation of chondrocyte proliferation”, “growth plate cartilage development”, “chondrocyte proliferation”, “cartilage condensation”, and “chondrocyte development”. Hub osteogenic genes at this phase were Sox9 and Comp. At day 14, the top five items were “chondroblast differentiation”, “intramembranous ossification”, “growth plate cartilage development”, “Cartilage condensation”, and “Endochondral ossification”. Col2a1, Col1a1, and Mmp13 were the hub osteogenic genes. At day 28, the top five items included “chondroblast differentiation”, “intramembranous ossification”, “negative regulation of cartilage development”, “endochondral bone morphogenesis”, and “chondrocyte differentiation”. Gdf5, Acan, and Ctsk were the hub osteogenic genes.

PPI networks of hub genes at each time point. (A) PPI network at day 3. (B) PPI network at day 7. (C) PPI network at day 14. (D) PPI network at day 28. The size and color of the gene nodes represent the degree of interaction between each gene and others in the network. Larger circles and colors closer to red indicate a higher level of interaction, while smaller circles and colors closer to blue signify lower interaction levels.

Identification of the hub osteogenic genes at four time points. (A) Hub osteogenic genes at day 3. (B) Hub osteogenic genes at day 7. (C) Hub osteogenic genes at day 14. (D) Hub osteogenic genes at day 28. Genes participating in top five GO-BP items directly related to osteogenesis at each time point were marked with distinct colors in the networks. The more colors a gene marked with, the more items it was involved in.

Functional enrichment analysis

According to the GO analysis, the top 10 enriched terms at each time point were displayed (Fig. 6). Extracellular matrix and collagen-related terms were significantly enriched across all four time points. In addition, “lymphocyte and leukocyte proliferation” as well as “chemorepellent activity” were predominantly enriched at day 3. From day 3 to day 7, terms such as “the regulation of cell adhesion”, “cargo receptor activity”, and “scavenger receptor activity” were enriched. Between day 7 and day 28, terms including “connective tissue development”, “bone development”, and “ossification” were enriched, while “cartilage development” and “growth factor binding” were mostly enriched between days 14 and 28. The term “bone mineralization” was enriched by day 28. KEGG21 analysis further illustrated the pathways varied with time (Fig. 7). Among the enriched pathways, “ECM-receptor interaction” and ‘protein digestion and absorption” were most significantly enriched throughout the healing process.

CeRNA networks

We identified hub osteogenic genes and their predicted miRNA-mRNA interactions. At day 3, rno-miR-29a-3p with Col3a1, rno-miR-9a-5p with Col9a1, and rno-miR-150-3p with Col9a1. At day 7, rno-miR-30c-5p with Sox9, rno-miR-181c-5p with Comp, and rno-miR-361-3p with Comp. At day 14, rno-miR-128-3p with Mmp13, rno-miR-150-5p with Col1a1, and rno-miR-423-5p with Col1a1. At day 28, the interactions consisted of rno-miR-191a-3p, rno-miR-185-5p, and rno-miR-15b-3p, all targeting Ctsk. Then, we predicted lncRNA-miRNA interactions by cross-referencing the identified miRNAs with the top 10 DELs ranked by log2FC for each time point (Table 1). The two consistently upregulated lncRNAs across all four time points were AABR07030366.1 and AABR07057997.1, with their most significant predicted miRNA targets shown in Table 2. Comprehensive predictions of lncRNA-miRNA interactions are provided in supplementary files 7–10. Based on predicted interactions, we constructed ceRNA regulatory networks, integrating the identified lncRNA, miRNA, and mRNA interactions in different phases (Fig. 8).

Experimental validation of key genes in the ceRNA network

To further validate our findings, we performed qRT-PCR on key molecules in the ceRNA network. We selected two lncRNAs that were significantly upregulated at all time points, AABR07030366.1 and AABR07057997.1. Additionally, miRNA and mRNA that were predicted to have ceRNA interactions with the two lncRNAs at different time points were also examined. Specifically, at day 3, rno-miR-9a-5p and Col9a1; at day 7, rno-miR-181c-5p and Comp; at day 14, rno-miR-423-5p and Col1a1; and at day 28, rno-miR-185-5p and Ctsk were analyzed. The qRT-PCR results confirmed that the expression of AABR07030366.1 and AABR07057997.1 increased in the callus at all time points post-fracture (Fig. 9A and B). Furthermore, at day 3, rno-miR-9a-5p expression decreased while Col9a1 expression increased; at day 7, rno-miR-181c-5p expression decreased while Comp expression increased; at day 14, rno-miR-423-5p expression decreased while Col1a1 expression increased; and at day 28, rno-miR-185-5p expression decreased while Ctsk expression increased (Fig. 9C and D).

Molecular experiments validation of key molecule through qRT-PCR. (A) Expression changes of AABR07030366.1 at four time points. (B) Expression changes of AABR07057997.1 at four time points. (C) Expression changes of selected miRNA at four time points. (D) Expression changes of selected mRNA at four time points. Statistical analysis was conducted by Student’s t-test. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001.

Discussion

Fractures are typically caused by traumatic events, such as falls, collisions, and traffic accidents. Although bone tissue possesses a remarkable regenerative capacity, the healing can be compromised under certain conditions. Factors including inadequate stabilization, failed surgical interventions, infections, and malnutrition are common impediments to proper healing22. Fracture healing is a prolonged biological process that may take up to two years at the histological level. However, the early post-fracture period plays a crucial role in functional recovery and radiological consolidation23. Previous transcriptomic studies have characterized the transcriptional features of callus tissue during fracture healing, mainly focusing on mRNA expression24,25,26 or mRNA-miRNA regulatory interactions27,28. In contrast, research on lncRNA regulation in fracture healing has predominantly examined specific lncRNA-miRNA interactions. For instance, lncRNA KCNQ1OT1 accelerates fracture healing through the miR-701-3p/FGFR3 axis29. LncRNA MAGI2-AS promotes healing by targeting miR-223-3p30. Conversely, lncRNA SNHG1 inhibits tibial fracture healing by regulating the miR-181a-5p/PTEN axis31. In this study, we performed high-throughput sequencing analysis of callus tissue at different early time points in a rat tibial fracture model. Our aim was to investigate a potentially complex and dynamic molecular mechanism involving lncRNA, miRNA, and hub osteogenic genes during fracture healing.

We conducted GO and KEGG enrichment analyses to investigate the roles of hub genes at different phases of fracture healing. The results show consistent and significant enrichment of extracellular matrix organization and collagen metabolism across all four time points. Collagen is the most abundant protein in the ECM of mammals, forming the essential organic component of the bone matrix. Bone ECM consists of inorganic elements, primarily calcium-deficient apatite, and organic components, primarily collagen. ECM metabolism is activated during bone development and orthopedic disorders, interacting dynamically with osteoblasts and osteoclasts to regulate bone formation32,33,34.

At day 3, immune and inflammatory responses were most prominent. Enriched processes and pathways related to lymphocytes, leukocytes, chemokines, and advanced glycation end products (AGEs) were observed. AGEs, products of excessive sugar-protein binding, interact with the AGE receptor (RAGE) to activate NF-κB and promote inflammation35. The interaction between inflammatory cells and mesenchymal stem cells is crucial for bone repair and remodeling36. Enrichment of axon guidance and distal axon suggests active axonal development. Studies show that early nerve innervation at the fracture site precedes angiogenesis, ossification, and mineralization, with TrkA signaling in sensory nerves playing a key role in fracture repair37. By day 7, connective tissue development, bone development, and ossification were enriched and persisted through day 28. In the Cellular Components category, apical plasma membrane was significantly enriched. It plays a key role in the ion exchange crucial for bone metabolism, with osteoblasts and osteoclasts modulating pH through proteins on their apical membranes, aiding bone remodeling38,39. By day 14, pathways related to cartilage development, osteoclast differentiation, and relaxin signaling were significantly enriched. Relaxin has been shown to enhance BMP2-induced osteoblast differentiation40. By day 28, bone mineralization and skeletal system morphogenesis were enriched, indicating that the healing process had transitioned from initial bridging and repair at the injury site to the maturation and remodeling of new bone. Comparing functional enrichment results with distinct phases of fracture healing, we observed a strong correlation between enriched pathways and the key stages of bone repair. Specifically, day 3 aligns with the inflammatory phase, while days 7, 14, and 28 correspond to the early, mid, and late phases of endochondral bone formation, respectively. This pattern underscores the sequential and coordinated biological processes driving fracture healing.

We identified hub osteogenic genes at distinct phases of bone healing: Col3a1 and Col9a1 during the inflammatory phase, Sox9 and Comp during early endochondral ossification, Col2a1, Col1a1, and Mmp13 in the mid-phase, and Gdf5, while Acan, and Ctsk in the late phase. Collagen proteins, including Col1a1 and Col2a1, are crucial for the structural integrity of bone and cartilage ECM. They also facilitating mineral deposition a key process in bone formation. Mutations in these proteins can reduce bone density and increase fragility41,42,43. Sox9, Comp, and Acan are cartilage-specific. Sox9, a transcription factor, regulates the TGF-β and BMP signaling pathways, which are vital for maintaining the health of growth plates and articular cartilage44. Matrix proteins Comp and Acan contribute significantly to cartilage ECM stability45,46. Gdf5 enhances cell adhesion and promotes mesenchymal condensation. It also upregulating the expression of other chondrogenic genes47. Mmp13 degrades collagens I, II, III, and X, while Ctsk, expressed in osteoclasts, degrades the bone matrix during resorption. Together, they play a critical role in bone remodeling48,49. In summary, hub osteogenic genes include collagen and non-collagen proteins essential for ECM construction. Transcription factors and growth factors that control chondrocyte differentiation. Proteases mediate bone matrix degradation. They collaboratively regulate the process of fracture healing.

The classical ceRNA mechanism of lncRNA relies on their competitive binding to miRNAs, thereby alleviating the inhibitory effect of miRNA on mRNA and enhancing mRNA expression. Based on this, we selected up-regulated DELs, DEGs along with down-regulated DEMs to predict interactions and construct the ceRNA regulatory network. In this network, day 3 included 2 mRNAs, 3 miRNAs, and 9 lncRNAs; day 7 included 2 mRNAs, 3 miRNAs, and 8 lncRNAs; day 14 included 2 mRNAs, 3 miRNAs, and 8 lncRNAs; and day 28 included 1 mRNA, 3 miRNAs, and 10 lncRNAs. We further validated our findings using qRT-PCR, which confirmed that the key lncRNAs AABR07030366.1 and AABR07057997.1 were significantly upregulated at all time points. Additionally, the expression patterns of the validated miRNAs and mRNAs at each time point were also consistent with the sequencing results.

Previous studies have established that part of miRNA within the ceRNA network plays a negative regulatory role in osteogenesis. For example, miR-29a-3p, miR-128-3p, miR-150-5p, and miR-185-5p inhibit the osteogenic differentiation of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells50,51,52,53, miR-361-3p promotes the progression of osteoarthritis54, miR-30c-5p induces bone developmental defects55, and miR-423-5p triggers cartilage degeneration in intervertebral discs56. Notably, miR-181c-5p, miR-150-5p, and miR-423-5p have been shown to be downregulated in early fracture callus28, a finding consistent with our results. However, compared to humans and mice, lncRNA-related studies in rats remain limited, and many lncRNAs in ceRNA networks remain largely unexplored. Their specific mechanisms in bone fracture healing have yet to be elucidated. In this study, we identified two lncRNAs, AABR07030366.1 and AABR07057997.1, which were significantly upregulated in early fracture callus. Throughout the healing process, they dynamically regulate gene expression by interacting with different miRNAs, playing a key role in early-stage fracture repair. Additionally, other lncRNA in the network showed significant upregulation at specific phases, suggesting their involvement in the distinct process of fracture healing. We envision that future interventions could be tailored to specific stages of fracture healing by targeting distinct molecular mechanisms. For example, introducing lncRNAs that engages in ceRNA interactions with hub osteogenic genes at a given stage may enable more precise and effective therapeutic strategies.

Despite the insights gained from this study, several limitations should be acknowledged. First, the sample size in this study is not large enough, a larger sample size is needed for the follow-up analysis. Second, species-specific differences may limit the direct applicability of our findings to human fracture healing. Further validation in human samples is necessary to confirm their clinical relevance. Finally, while we established a ceRNA network and identified key lncRNAs with dynamic expression patterns, their precise mechanisms of action in osteogenic regulation remain unclear. Additional experimental validation, such as gene silencing or overexpression studies, is needed to elucidate their roles in bone healing.

Conclusion

This study conducted high-throughput sequencing of local fracture tissues in rats at multiple time points, revealing the dynamic transcriptomic changes during the early stages of fracture healing. We identified mRNA, lncRNA, and miRNA critical to different healing phases and, through the construction of ceRNA networks, uncovered novel regulatory molecules and their interactions. These findings enhance our understanding of the dynamic mechanisms of fracture healing and provide potential targets for stage-specific therapeutic interventions to improve fracture healing outcomes.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are available in the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) repository, Accession is GSE262132.

References

Cheng, C. & Shoback, D. Mechanisms underlying normal fracture healing and risk factors for delayed healing. Curr. Osteoporos. Rep. 17, 36–47. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11914-019-00501-5 (2019).

Brinker, M. R., Trivedi, A. & O’Connor, D. P. Debilitating effects of femoral nonunion on Health-Related quality of life. J. Orthop. Trauma. 31, e37–e42. https://doi.org/10.1097/BOT.0000000000000736 (2017).

Deogharia, M. & Gurha, P. The guiding principles of noncoding RNA function. WIREs RNA. 13. https://doi.org/10.1002/wrna.1704 (2021).

The expanding world of noncoding RNA biology. Nat. Cell. Biol. 24, 1447–1447. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41556-022-01016-5 (2022).

Tay, Y., Rinn, J. & Pandolfi, P. P. The multilayered complexity of CeRNA crosstalk and competition. Nature 505, 344–352. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature12986 (2014).

Xiong, Y. et al. The LncRNA Rhno1/miR-6979-5p/BMP2 Axis modulates osteoblast differentiation. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 16, 1604–1615. https://doi.org/10.7150/ijbs.38930 (2020).

Su, C., Wang, H., Xu, L., Zhang, Y. & Li, Y. MALAT1/miR-320a in bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells function May shed light on mechanisms underlying osteoporosis. Arch. Med. Sci. 18, 1638–1649. https://doi.org/10.5114/aoms/105838 (2022).

Chen, S. et al. Long noncoding RNA NORAD promotes fracture healing through interacting with osteoblast differentiation via targeting miR-26a. Biomed. Res. Int. 2023, 9950037. https://doi.org/10.1155/2023/9950037 (2023).

Einhorn, T. A. & Gerstenfeld, L. C. Fracture healing: mechanisms and interventions. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 11, 45–54. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrrheum.2014.164 (2015).

Rundle, C. H. et al. Microarray analysis of gene expression during the inflammation and endochondral bone formation stages of rat femur fracture repair. Bone 38, 521–529. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bone.2005.09.015 (2006).

Yu, M. D., Su, B. H. & Zhang, X. X. Morphologic and molecular alteration during tibia fracture healing in rat. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 22, 1233–1240. https://doi.org/10.26355/eurrev_201803_14463 (2018).

Erener, T. et al. Investigation of the effect of Ghrelin on bone fracture healing in rats. Clin. Exp. Pharmacol. Physiol. 48, 1382–1390. https://doi.org/10.1111/1440-1681.13544 (2021).

Kerimoglu, G., Yulug, E., Kerimoglu, S. & Citlak, A. Effects of leptin on fracture healing in rat tibia. Eklem Hastalik Cerrahisi. 24, 102–107. https://doi.org/10.5606/ehc.2013.23 (2013).

Dejea, H. et al. Multi-scale characterization of the spatio-temporal interplay between elemental composition, mineral deposition and remodelling in bone fracture healing. Acta Biomater. 167, 135–146. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actbio.2023.06.031 (2023).

Kluter, T. et al. Rivaroxaban does not impair fracture healing in a rat femur fracture model: an experimental study. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 16, 79. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12891-015-0502-9 (2015).

Danoff, J. R., Auregan, J. C., Coyle, R. M., Burky, R. E. & Rosenwasser, M. P. Augmentation of fracture healing using soft callus. J. Orthop. Trauma. 30, 113–118. https://doi.org/10.1097/BOT.0000000000000481 (2016).

Woloszyk, A. et al. Fracture hematoma micro-architecture influences transcriptional profile and plays a crucial role in determining bone healing outcomes. Biomater. Adv. 139, 213027. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bioadv.2022.213027 (2022).

McMillan, T. E. & Johnstone, A. J. Technical considerations to avoid delayed and non-union. Injury 48 (Suppl 1), S64-S68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.injury.2017.04.019 (2017).

Tian, R. et al. Prevalence and influencing factors of nonunion in patients with tibial fracture: systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Orthop. Surg. Res. 15, 377. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13018-020-01904-2 (2020).

Miranda, K. C. et al. A pattern-based method for the identification of MicroRNA binding sites and their corresponding heteroduplexes. Cell 126, 1203–1217. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2006.07.031 (2006).

Kanehisa, M., Furumichi, M., Sato, Y., Matsuura, Y. & Ishiguro-Watanabe, M. KEGG: biological systems database as a model of the real world. Nucleic Acids Res. 53, D672–D677. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkae909 (2025).

Wildemann, B. et al. Non-union bone fractures. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers. 7, 57. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41572-021-00289-8 (2021).

Mick, P. & Fischer, C. Delayed fracture healing. Semin Musculoskelet. Radiol. 26, 329–337. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0041-1740380 (2022).

Coates, B. A. et al. Transcriptional profiling of intramembranous and endochondral ossification after fracture in mice. Bone 127, 577–591. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bone.2019.07.022 (2019).

Hauser, M., Siegrist, M., Keller, I. & Hofstetter, W. Healing of fractures in osteoporotic bones in mice treated with bisphosphonates - A transcriptome analysis. Bone 112, 107–119. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bone.2018.04.017 (2018).

Jiang, W., Caruana, D. L., Back, J. & Lee, F. Y. Unique Spatial Transcriptomic Profiling of the Murine Femoral Fracture Callus: A Preliminary Report. Cells 13. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells13060522 (2024).

Li, X., Zhong, Z., Ma, E. & Wu, X. Identification of MiRNA regulatory networks and candidate markers for fracture healing in mice. Comput. Math. Methods Med. 2021, 2866475. https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/2866475 (2021).

Bourgery, M. et al. Multiple targets identified with genome wide profiling of small RNA and mRNA expression are linked to fracture healing in mice. Bone Rep. 15, 101115. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bonr.2021.101115 (2021).

Chen, L. et al. LncRNA KCNQ1OT1 accelerates fracture healing via modulating miR-701-3p/FGFR3 axis. FASEB J. 34, 5208–5222. https://doi.org/10.1096/fj.201901864RR (2020).

Dong, Z. et al. LncRNA MAGI2-AS3 promotes fracture healing through downregulation of miR-223-3p. J. Orthop. Surg. Res. 19, 370. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13018-024-04850-5 (2024).

Guo, X., Zhang, J., Han, X. & Wang, G. LncRNA SNHG1 delayed fracture healing via modulating miR-181a-5p/PTEN Axis. J. Invest. Surg. 35, 1304–1312. https://doi.org/10.1080/08941939.2022.2048926 (2022).

Okazaki, K. & Sandell, L. J. Extracellular matrix gene regulation. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 123–128. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.blo.0000144478.51284.f3 (2004).

Alcorta-Sevillano, N., Macias, I., Infante, A. & Rodriguez, C. I. Deciphering the Relevance of Bone ECM Signaling. Cells 9. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells9122630 (2020).

Nyman, J. S. & Makowski, A. J. The contribution of the extracellular matrix to the fracture resistance of bone. Curr. Osteoporos. Rep. 10, 169–177. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11914-012-0101-8 (2012).

Wang, S. et al. Huanglian ointment alleviates eczema by maintaining the balance of c-Jun and JunB and inhibiting AGE-RAGE-mediated pro-inflammation signaling pathway. Phytomedicine 105, 154372. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.phymed.2022.154372 (2022).

Loi, F. et al. Inflammation, fracture and bone repair. Bone 86, 119–130. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bone.2016.02.020 (2016).

Li, Z. et al. Fracture repair requires TrkA signaling by skeletal sensory nerves. J. Clin. Invest. 129, 5137–5150. https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI128428 (2019).

Blair, H. C. et al. Support of bone mineral deposition by regulation of pH. Am. J. Physiol. Cell. Physiol. 315, C587–C597. https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpcell.00056.2018 (2018).

Baron, R. Molecular mechanisms of bone resorption by the osteoclast. Anat. Rec. 224, 317–324. https://doi.org/10.1002/ar.1092240220 (1989).

Moon, J. S. et al. Relaxin augments BMP-2-induced osteoblast differentiation and bone formation. J. Bone Min. Res. 29, 1586–1596. https://doi.org/10.1002/jbmr.2197 (2014).

Selvaraj, V., Sekaran, S., Dhanasekaran, A. & Warrier, S. Type 1 collagen: synthesis, structure and key functions in bone mineralization. Differentiation 136, 100757. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.diff.2024.100757 (2024).

Marini, J. C. et al. Osteogenesis imperfecta. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers. 3, 17052. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrdp.2017.52 (2017).

Eyre, D. Collagen of articular cartilage. Arthritis Res. 4, 30–35. https://doi.org/10.1186/ar380 (2002).

Haseeb, A. et al. SOX9 keeps growth plates and articular cartilage healthy by inhibiting chondrocyte dedifferentiation/osteoblastic redifferentiation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 118 https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2019152118 (2021).

Cui, J. & Zhang, J. Cartilage oligomeric matrix protein, diseases, and therapeutic opportunities. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23 https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms23169253 (2022).

Hodax, J. K. et al. Aggrecan is required for chondrocyte differentiation in ATDC5 chondroprogenitor cells. PLoS One. 14, e0218399. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0218399 (2019).

Sun, K., Guo, J., Yao, X., Guo, Z. & Guo, F. Growth differentiation factor 5 in cartilage and osteoarthritis: A possible therapeutic candidate. Cell. Prolif. 54, e12998. https://doi.org/10.1111/cpr.12998 (2021).

S, S., et al. Matrix metalloproteinase-13: A special focus on its regulation by signaling cascades and MicroRNAs in bone. Int J. Biol. Macromol 109, 338–349. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2017.12.091 (2018).

Gao, L. H., Li, S. S., Yue, H. & Zhang, Z. L. Associations of serum cathepsin K and polymorphisms in CTSK gene with bone mineral density and bone metabolism markers in postmenopausal Chinese women. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne). 11, 48. https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2020.00048 (2020).

Wang, C. et al. MiR-29a-3p inhibits proliferation and osteogenic differentiation of human bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells via targeting FOXO3 and repressing Wnt/beta-Catenin signaling in Steroid-Associated osteonecrosis. Int. J. Stem Cells. 15, 324–333. https://doi.org/10.15283/ijsc21147 (2022).

Zhang, W. et al. Mechanisms of miR–128–3p in inhibiting osteoblast differentiation from bone marrow–derived mesenchymal stromal cells. Mol. Med. Rep. 22, 5041–5052. https://doi.org/10.3892/mmr.2020.11600 (2020).

Qi, J. L., Zhang, Z. D., Dong, Z., Shan, T. & Yin, Z. S. mir-150-5p inhibits the osteogenic differentiation of bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells by targeting Irisin to regulate the p38/MAPK signaling pathway. J. Orthop. Surg. Res. 19, 190. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13018-024-04671-6 (2024).

Zhang, J., Xu, N., Yu, C., Miao, K. & Wang, Q. LncRNA PART1/miR-185-5p/RUNX3 feedback loop modulates osteogenic differentiation of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells. Autoimmunity 54, 422–429. https://doi.org/10.1080/08916934.2021.1966771 (2021).

Wang, C. et al. The role of circrna derived from RUNX2 in the serum of osteoarthritis and its clinical value. J. Clin. Lab. Anal. 35, e23858. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcla.23858 (2021).

Wang, W. et al. Toxicity mechanisms regulating bone differentiation and development defects following abnormal expressions of miR-30c targeted by triclosan in zebrafish. Sci. Total Environ. 850, 158040. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.158040 (2022).

Xu, H. et al. MiR-423-5p regulates cells apoptosis and extracellular matrix degradation via Nucleotide-Binding, Leucine-Rich repeat containing X1 (NLRX1) in Interleukin 1 beta (IL-1beta)-Induced human nucleus pulposus cells. Med. Sci. Monit. 26, e922497. https://doi.org/10.12659/MSM.922497 (2020).

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank the members of the research group for their hard work.

Funding

This study was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of Beijing of China [grant number 7192215] and the National Natural Science Foundation of China [grant number 82072162].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.G.: Writing - review & editing, Writing - original draft, Data curation, Visualization. S.W.: Writing - review & editing, Data curation. S.Y.: Data curation, Visualization, Validation. X.G.: Data curation. J.D.: Data curation. C.H.: Data curation. X.Z.: Data curation. Q.L.: Supervision, Data curation. X.Y.: Supervision, Funding acquisition, Data curation. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

The experimental scheme has passed the animal ethics requirements of Peking University People’s Hospital (2024PHE029). All animal experiments were performed strictly according to the requirements of the Animal Ethics Procedures and Guidelines of the People’s Republic of China and in accordance with ARRIVE guidelines.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Guo, S., Wang, S., Yuan, S. et al. Construction of dynamic ceRNA regulatory networks in osteogenesis during fracture healing based on transcriptomic analysis. Sci Rep 15, 26946 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-12505-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-12505-6

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Upregulation of lncRNA SSTR5-AS1 promotes osteoblast differentiation and reduces apoptosis

Journal of Orthopaedic Surgery and Research (2025)