Abstract

For lightweight automotive applications, friction drilling is a choice candidate for ecofriendly drilling of aluminium matrix composites (AMCs) with green snail shell reinforcement. The present work investigates the effects of significant process variables such as spindle speed, feed rate, workpiece thickness, and drill diameter on bushing length, bushing thickness, and roundness. Higher spindle speeds and lower feed rates enhance bushing length due to controlled material flow and heat generation. However, higher spindle speeds and inappropriate feed rates resulted in decreased roundness. Microstructural examination reveals different zones across the bush formation during the friction drilling process. The head petal and tail petal regions have coarse grains in the range of 20 to 40 μm due to disrupted material flow. Surface topography of all bushing zones reflects the interconnected mechanical and thermal impacts which occur during friction drilling. Surface quality is on higher side at areas with optimal heat generation and material movement such as Upper Critical Region, and lower side at areas with excessive or insufficient deformation such as head and tail Petal Regions. The surface topography analysis at bushing zone reflects the coupled thermal and mechanical effects during friction drilling. Excessive deformation plays a crucial role in the surface quality. Poor surface quality can be observed at Head and Tail Petal Regions due to the excessive deformations. Dynamic recrystallisation produced fine grains in the order of 5 μm in the Upper Critical Region with ideal temperature and mechanical conditions. Random Forest (RF), Multilayer Perceptron (MLP), Gaussian Process Regression (GPR) and Support Vector Machine (SVM) models were employed for the prediction of distinct output responses.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

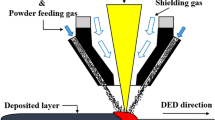

Sustainable manufacturing has been given much significance as rapid acceleration of industrialization disturbed the balance in ecological system. Thus, manufacturing sector must focus both on the growth of the particular sector and sustainability simultaneously1,2. Together, these initiatives exemplify a worldwide trend in which sustainability measures are increasingly becoming the new norm, leading to the integration of eco-principles to promote production efforts toward green manufacturing and industrialization3,4. Designing, processing and manufacturing products through substantiality measures involve interdisciplinary activities, complex systems and viable solutions. However on long run, sustainable manufacturing practices benefits the organization through accomplishing economic, environmental and societal aspects of sustainability5,6. Machining plays an inevitable part in manufacturing and contributes significantly in Gross domestic product (GDP). Apart from the contribution in economy, machining significantly influences the environment7,8. Swift machining, optimum resource deployments, smart production practices etc. assist manufacturing setup to achieve clean machining9,10. Environment concerned machining approaches have been researched by exploring the possibilities through various machining operations. One of such potential possibilities can be recognised in drilling process11,12. Various challenges/issues are associated with conventional machining practices such as waste management (chips & cutting fluid disposal), tool life, superfluous heat, resource deployments, etc13,14. Pramanik et al. investigated sustainable drilling practices for aluminum alloys with environmental concerns resulting in enhancement of machining performance15. Tooling requirements mostly met by high speed-steels for executing the drilling operations. High speed-steels normally lead to high temperature while drilling limits the tool life and dullness can be observed consequently16,17,18,19. Moreover, workpiece hardening can be found as a result of high temperature and leads to further deterioration. Due to the nature of chip generation and its flow in drilling, surface texture is affected very much within the hole region20. Twist drilling process encounters tool wear related issues. The involvement of cutting fluids is also an inevitable part which further affect the accomplishment of the sustainable machining21. Friction-drilling is a modern and novel sustainable drilling solution which work based on plastic deformation through thermo-mechanical phenomenon occurs under solid-state condition22,23. Through the synergistic combination of axial force and friction-induced heat, this method offers a promising avenue for enhancing drilling operations across diverse industrial sectors. Thermal energy is obtained by rotating the tool against workpiece with the combination of mechanical energy as tool travels downwards against the specimen perpendicularly24. The axial force with combination of frictional heat leads to the bush formation within few seconds through plastic deformation25. The synchronized application of the axial force and frictional heat initiates the rapid formation of the bushing26. Effective orientation of grains can be observed at hole region in comparison to the conventionally drilled hole. The pre-processing step called pre-drilling can be eliminated in friction-drilling27. Drilling execution time can be minimised in friction-drilling through simplifying the complexities involved in the traditional approaches. Due to the nature of friction-drilling, tapping operation can be accommodated along with drilling as a subsequent process. The clogging issue associated with chip blockage can be eliminated as material deformation takes place instead of material removal28. Due to the absence of chips, unwanted friction, chip evacuation and high torque formation can be avoided. Moreover, friction-drilling provides solution for drilling in depth holes with small diameter as there are no chip formation in this modern technique29. The present research work focuses on the sustainable machining aspects of friction-drilling on metal matrix workpiece materials. The presence of multi constituents in these composite materials deliver superior performance during high temperature applications also. Excellent thermal conductivity with the combination low thermal-expansion coefficient provides added advantages for metal matrix workpiece materials30. However, metal matrix composites exhibit hindrances during the material removal through reinforcements present in the composites31. During high depth of drilling, flank-wear is witnessed severely. Difficulties have been experienced during the machining of metal matrix workpiece materials with combination of high speed-steel drills. During the traditional drilling of these composites, there are more possibilities for burr formation32. Reinforcing materials degrade the tool material during the drilling process33. The magnitude of drilling-forces increases due to the presence of reinforcements which affect the drilled hole quality34. Reinforcement materials are potential sources in the acceleration of tool wear rate that directly have the negative impact on the tool life. Consequently, further load can be witnessed in drilling due to the deterioration of tool35. Friction-drilling provides novel and potential solutions to these concerns associated with conventional drilling approaches and provides opportunities to deploy this modern drilling process on metal matrix composites36. Besides, the processing conditions such as spindle speed, feed rate, work thickness are very crucial for the heat generation and the control of material flow. Machine learning algorithms could be effectively used for modelling the process and predicting the bushing length and other significant output responses.

The Machine learning (ML) is a transformative technology with many uses in sustainable manufacturing and can provide multiple benefits when implemented. A lot of work has been done towards the improvement of cutting operation using ML approaches primarily for the objectives of increasing the efficiency and classification of different aspects37.One of the categories of ML is the supervised learning in which the training dataset is already classified in order to test and make conclusions with an algorithm. Ross et al.38 highlight that the ML models such as multilayer perceptron (MLP) that identifies non-linear relations and random forest (RF) can be used to predict and classify machining results. In another study, supervised learning systems have been employed by Karabacak et al.37 to predict tool wear using cutting conditions as well as the characteristics of the tool involved in machining. Similarly, supervised learning methods were adopted by Elangovan et al.39 to analyze the effects of cutting parameters and material properties on roughness estimation in machining process. Flegner et al.40 discussed that in machining, clustering algorithms are used for analyzing the vibration signals and aid in definition of different regimes of machining for the improvement of the process. In the present works, machine learning techniques have been engaged in the predictions of bushing length, thickness and roundness against the significant input parameters namely drill rotating speed and feed-rate. The experimental data are effective resources for the application of machine learning approaches. Green-reinforcements are strengthening the sustainability aspects by providing competent composite materials for structural applications. Bio-wastes and industrials wastes are leading contributors for green-reinforcements. Snail-shells are one of such potential contributors41. Snail-shells have been incorporated as hybrid reinforcements along with glass fiber as a part of sustainable initiative, and potential possibilities are explored through successful experiment by producing composites with recycled polypropylene42. The present research work has considered such potential possibilities in the aspects of sustainable machining and carried out the research on the combination of friction-drilling and metal matrix composites. Garden snail-shell (Theba pisana) is deployed as natural reinforcements in the present work. Friction-drilling was experimented already on aluminium-silicon carbide particulates based metal-matrix composites and quality hole formation increases the possibilities of the application of this modern technology on metal-matrix based composites43. Other than synthetic reinforcements, metal-matrix composites have been experimented with plants, minerals44 and animals based natural reinforcements in the context of cost effectiveness, mechanical property enhancements and sustainability45. This new method for improving the mechanical and tribological qualities of aluminium matrix composites (AMCs) made by aluminium as matrix material with green reinforcement of snail shell. Snail shells are a sustainable reinforcement material is a naturally occurring waste product that is widely accessible and biodegradable. Envisaging applications in high-strength, low-density aerospace structural parts as well as lightweight automotive components, friction drilling of snail shell reinforced aluminium matrix composites is integrated with machine learning predictions in the present work.

Materials and methods

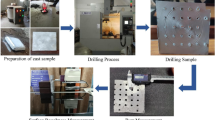

In the present experimental research, snail-shell particulates (20% by weight) reinforced aluminium-matrix composite is selected as base workpiece material for friction-drilling. The weight% of the inclusion of snail-shell particulates are finalised through experimenting and exploring mechanical properties with different percentages of snail-shell reinforcements. The stir-casted composite specimen (Fig. 1) is machined down into 1 mm, 2 mm and 3 mm thin plates for friction-drilling.

Friction-drill tool is produced with OHNS (Oil-Hardened Non-Shrinking Steel) tool steel material. This tool material is known for its great durability, exceptional wear resistance, front-line maintenance, etc. A conventional milling machine is utilized in the present research work for executing the friction-drilling. The specimen holding platform is customised to accommodate the thin aluminium-based metal-matrix composite specimen. The holding platform enables the friction-drilling tool to approach the bottom side of the specimen to accomplish the entire process cycle. The fixing of the friction-drill tool is similar to the conventional milling tool fixing where tool holding spindle holds the tool firmly. The tool is fixed such a way that the friction drill part approaches the specimen first followed by the tapping part. The execution of the friction-drilling operation remains same as conventional drilling in most steps. However, the end results vary according to the tool geometry as the material formation can be witnessed as a result of plastic-deformation whereas the material removal happens in the conventional process.

Friction-drill tool penetrates the aluminium-based metal-matrix composite specimen during the downward travel of the tool. Axial-drilling force and torque are the prime source behind the initial infiltration. Later, the material formation takes place due to the frictional heat generation through the friction between tool and specimen. The plain profile of friction-drill part of the tool is the prime reason behind the bush formation as exhibited in Fig. 1. The friction-drill tool was held by the spindle of the machine similar to conventional milling tools. The process parameters spindle speed (200 rpm, 300 rpm and 400 rpm), feed rate (0.0021 mm/rev, 0.0045 mm/rev and 0.0086 mm/rev) and plate thickness to tool diameter ratio (0.07, 0.14 and 0.22) were considered in the full factorial experimental design. Each parameter was tested at three levels. 27 combinations were performed, determined through preliminary trials to optimize bush and thread formation. Table 1 shows the input process parameters along with their respective levels used for this study. The coded values of input process parameters are given in Table 2. Friction drill M16 - Ø 14.9 used with a rounded tip to initiate contact and generate heat through friction and it has a 90° conical angle and it does not have a nose radius in the conventional sense.

Results and discussion

In friction drilling, frictional heat generated by a conical tool allows it to penetrate a workpiece. It subsequently results in the formation of a bushing, that extends the hole length due to plastic deformation of the material. During initial contact the rotating friction drill comes in contact with the surface of the work piece. Localized heat generated between the workpiece and the tool softens the material. Because of plastic deformation, the tool penetrates further, resulting like bushing-like extended structure. The material begins to flow upward around the tool and downward beneath the surface. Because of frictional heating, distinct zones are developed which are characterized by material softening and microstructural changes. The mechanism of bushing formation during friction drilling of snail shell-reinforced aluminium matrix composites could be comprehended by observing at the microstructural changes across different regions of bush (Fig. 2). Zonal regions, designated A through E, reveal distinctive features that resulted as a consequence of coupled mechanical and thermal effects occurred during the friction drilling process.

Microstructural analysis of bushing zones

Friction drilling produces an increase in heat due to high rotational speeds of the tool that causes snail shell-reinforced aluminium matrix composite to soften. As evidenced by the formation of bushing and plastic deformation, different areas have remarkably different microstructure and surface properties (Fig. 3). As it can be seen from the SEM micrographs and segmentation boundary images, there are microstructural alternation from one zone to another along five different zones.

Zone A: head petal region

The surface was examined using scanning electron microscopy, which revealed a mixture of long and irregular particles. This suggests that there was a large amount of plastic deformation at the location where the tool was inserted. A small number of cracks may be observed on the surface of the bushing as a result of the significant amounts of material displacement. An examination of the border segmentation reveals that the particle does not appear to be dispersed uniformly. Poor material displacement is considered as a consequence of the minimum initial impact of the tool, which leaves material to be extruded without complete compaction. This ultimately results in poor material displacement. During the process of inserting the instrument, the Head Petal Region is subjected to a significant amount of shear pressure. This causes the surface to become rough and causes the particles to break apart as a result of the rapid movement of the material under the influence of high temperatures and mechanical deformation. In Zone A, elongated and coarse grains are found because of severe plastic deformation. The average grain size is about 20 μm.

Zone B: thorax region

When compared to Zone A, the micrograph reveals that the surface homogeneity has been enhanced. It has been seen that the deformation patterns have become smoother, and there are fewer cracks, which is an indication of enhanced material flow. The segmented image emphasises particles that are smaller and more evenly scattered throughout the image. It can be observed that the particles are gradually aligning themselves, which is indicative of regulated plastic deformation. During the Thorax Region, the material that has been softened experiences a flow that is smoother and more uniform as the heat generation becomes more stable. This leads to a refined particle structure and a reduction in the number of cracks3. In Zone B, partially refined grains with an average diameter of about 12 μm could be seen. Grains are aligned due to favorable heat flow conditions.

Zone C: upper critical region

This region displays relatively smooth surface features with minimal defects. Uniform material flow and elongated particle structures are observed, which correlate with the thermal softening. The boundary segmentation shows highly aligned particles with consistent size. Minimal particle fragmentation occurs due to optimized thermal conditions. The Upper Critical Region benefits from optimal heat-softening effects, enabling smooth plastic deformation. The particle structure indicates significant material flow with minimal defects, contributing to a better surface finish. In Zone C, a fine with an average diameter of about 5 μm could be seen. Equiaxed grains are formed due to dynamic recrystallization and steady-state heat conditions.

Zone D: lower critical region

In this area, it is observed more surface discontinuities, and an increase in the bushing height and a decrease in bushing thickness. Some cracking does start to initiate, despite the fact, the particles are experiencing elongation. Segmented image shows that the particles are of different sizes compared to the particles in Zone C. Thermal softening occurs, which leads to a partial material flow Transition implies the initiation of heat loss in the lower critical field ranges. However, the thermal effects diminish and only partial material solidification and localized defects persist. In Zone D, elongated grains with an average diameter of about 14 μm could be seen. Coarser are formed due to partial recrystallization and some heat dissipation.

Zone E: tail petal region

In this area, the surface is rough and there is surface tearing. Large particles and some fragmented particles are visible in the segmented image. It displays that particles are dispersed in a random way and there is incomplete plastic flow. There is disruption to the flow of material due to rapid cooling and immediate solidification as the tool exits out. In Zone E, because of immediate cooling, much coarser grains with an average diameter of about 24 μm could be seen. Grains are irregular in shape because of disrupted heat flow conditions and quick dissipation.

Table 3 provides a detailed analysis of the microhardness distribution across different zones of a bushing formed during friction drilling of a snail shell reinforced aluminium matrix composite.

Surface characteristics of bushing

The evaluation of 3D topography along with the surface properties is crucial for understanding the quality of drilled holes. In friction drilling of aluminum, a bushing formed because of the frictional heat generated by a rotating, conical tool pressed against the aluminum workpiece. As the tool penetrates, it softens and displaces the material without cutting. This leads to the formation of several distinct zones within the bushing. This involves a high-resolution analysis of the material surface in both 2D and 3D formats, along with a roughness profile. Bushing wall height variations are seen in a 2D color-coded surface map. Heights are color-coded, with peaks in reds and oranges and valleys in blues and greens. This 2D map shows regions exposed to heat that are identified as “HAZ” (Heat-Affected Zones) where property changes are experienced by high temperature. Light green, dark green, light blue, dark blue, light red, dark red, and red spectrum variations, corresponding to differences in spectral colour intensities, suggest an uneven material flow and some rough surface, which is likely due to the interaction between the tool and the reinforced particles. The 3D Surface Topography Map is a more comprehensive, three-dimensional view of the surface topography. The height differences use the same colour gradient scale, with peaks in red and valleys in blue. It assists with identifying particular high peaks on the bushing wall surface. These peaks are probably due to the abrasive characteristics of the particles composing the snail shell, which interact with the tool when drilling. HAZ is indicated in this image, where heat has softened the aluminum matrix surrounding the reinforcement particles, leading to roughness and inhomogeneity in material flows. Those peaks and valleys in this zone are formed as a result of the coupled thermal and mechanical phenomenon that contributes to the roughness. The surface roughness profile consists of positive values representing peaks and negative values indicating valleys. Periodic peaks and valleys could be attributed to the non-uniform distribution of snail shell particles, microstructural changes within the HAZ and non-uniform heat distribution and cooling rates. Surface roughness is crucial in friction-drilled bushings, since it affects the mechanical properties, such as wear resistance and the ability to form strong connections with fasteners.

The 2D and 3D surface roughness maps (Fig. 4a) for Zone A of the Head Petal Region show the red for peaks and yellow-green for valleys. These variations indicate surface irregularities due to limited material flow and extrusion during tool entry. HAZ appears with darker areas closer to the peaks. The red peaks correspond to the regions of severe plastic deformation, while the green-yellow valleys show the zones with poor material flow. Material has been strongly pushed upwards in the region with red peaks, and valley-like yellow and green regions indicate incomplete material flow. Surface roughness in the range of 15–20 μm is observed in the surface roughness profile.

Surface roughness is lesser in the Thorax Region (Zone B) in comparison with Zone A, and smoother textures are uniformly spread out as yellow-green regions (Fig. 4b). The 3D peak red regions are relatively lower, indicating better material flow and reduced surface roughness. Here HAZ are the transition zones where the material is subject to less heat and deformation. Increased plasticity due to stabilized heat generation reduces the peaks and valleys, and the balance between the mechanical and thermal effects promote a more homogeneous structure. The improved uniformity shows a reduced number of peaks and valleys in the surface roughness profile, with roughness in the range of 8–12 μm.

The finest surface texture is observed in Zone C in the Upper Critical Region (Fig. 4c), where the light green and blue areas are predominant on the maps. Even in their deepest valleys or tallest red peaks, they show less surface irregularities and even material flow and minimum irregularities in the surface. Heating Affected zones are homogenously dispersed, promoting the desired thermal and mechanical conditions. The blue-green regions show low particle fragmentation and perfect microstructure alignments. The Upper Critical Region experiences a steady heat input that results in ideal circumstances for softening and controlled flow of material. The maps show uniform material flow (green and blue) with minimal deformation or tearing. The surface is the smoothest with the roughness value in the range of 3–5 μm.

Surface roughness slightly increases, with little red spots signifying localized peaks and yellow and green areas predominating in the local critical region (Fig. 4d). As thermal softening decreases, the surface changes from the homogeneity of Zone C to a more uneven structure. The roughness maps show a decrease in the intensity of colour transitions in the heat-affected zones. In the roughness maps, the green areas represent smoother regions, whereas the yellow areas represent areas of incomplete and partial material flow. Coarser grains and slightly rougher surface textures are the result of dynamic recrystallization being limited by reduced thermal softening. The change from green to yellow areas demonstrates how heat dissipation affects material flow. The roughness profile indicates increased roughness in comparison to Zone C with surface roughness in the range of 6–10 μm.

In the roughness maps of the tail petal region, high surface roughness brought on by disturbed material flow is noticeable with red peaks and yellow troughs (Fig. 4e). Significant surface irregularities caused by rapid cooling and material tearing are highlighted by the lack of consistent green or blue regions. Red spots correspond to areas of significant material extrusion and tearing; on the other hand, yellow valleys show partially disrupted material displacement. Rapid cooling and uneven deformation result from the sudden withdrawal of the tool, leading to disruption of the flow of material. Subsequently, it results in high surface roughness and coarse grains that are marked by the red peaks and yellow troughs with the surface roughness in the range of 15–25 μm.

The surface roughness values across different bushing zones in different values is presented in Table 4.

Effect on bushing length

Higher spindle speeds generate more heat that softens the aluminium matrix more effectively. This is increased friction causes the spindle to generate more heat. This, in turn, makes it possible to have a controlled flow of material along with the reinforcements45. As a consequence of this, the material that has been softened is more easily displaced and extruded, which ultimately results in longer bushing length that is more noticeable and longer. When feed rates are lower, there is more time for the tool to come in contact with the material. This eventually raises the amount of heat produced resulting in uniform and longer bushing length. Higher feed rates lead to inadequate heating and incomplete material flow. The tool moves quickly through the material, reducing the extent of extrusion and shortening the bushing length. Workpieces that are thicker more quantity of material is extruded and displaced, which ultimately results in a longer bushing length. When workpieces are thinner, there is less material available for extrusion, which results in shorter bushing length. Larger drill diameters help to achieve longer bushings by displacing more material. Smaller diameters, shortens bushing length. However, offers greater precision in bushing quality and wall thickness as revealed in Fig. 5.

Effect on bushing thickness

Increased spindle speeds produce greater heat because of more friction. It results in the aluminium matrix becoming more workable. Because of that, the material is able to flow around the tool with more ease, resulting in a thinner bushing. This is because the material is displaced outward rather than accumulated around the hole. Lower spindle speeds produce less heat, the aluminium continues to maintain its relatively high level of stiffness. Because of the decreased plastic deformation, the material comes together to form a longer bushing. The longer the tool-material interaction at lower feed rates, results in more amount of heat generation and leads to more plastic deformation as shown in Fig. 6. Because of this prolonged heating, the material tends to flow outward rather than upwards. This ultimately results in a thinner bushing. Higher feed rates limit the amount of heat generation, which in turn limits the flow of aluminium material. There is less plastic deformation, resulting in accumulation of material around the edge of the hole. This tends to increase in the thickness of the bushing. Working with thicker workpieces allows for a greater displacement of material during the friction drilling process. Because of the availability of more material around the hole, it results in typically thicker bushings. This occurs when sufficient heat is not produced and there is an incomplete partial material flow. On the other hand, thinner workpieces have less material for displacement around the circumference of the hole, resulting in reduced bushing thickness. When larger drill diameters penetrate, they displace more material, and this displacement can lead to the formation of a thicker bushing. Other parameters, such as feed rate or spindle speed, do not provide enough heat, and this thickening effect is more significant for larger diameters. Smaller drill diameters displace less material than larger drill diameters. Because of the availability of more material around the hole, it results in typically thicker bushings. This occurs when sufficient heat is not produced and there is an incomplete partial material flow. On the other hand, thinner workpieces have less material for displacement around the circumference of the hole, resulting in reduced bushing thickness. When larger drill diameters penetrate, they displace more material, and this displacement can lead to the formation of a thicker bushing. Other parameters, such as feed rate or spindle speed, do not provide enough heat and this thickening effect is more significant for larger diameters. Smaller drill diameters displace less material than larger drill diameters. In most cases, this leads to a thinner bushing, when combined with higher spindle speeds and lower feed rates.

Effect on roundness

When the spindle speed is raised, there is more heat generation due to the friction between the tool and the workpiece. This heat makes softens the material and it undergoes plastic deformation. Figure 7 reveals that higher spindle speed cause uneven plastic flow, eventually resulting in decrease of the roundness values. When the spindle speed is lower, there is insufficient heat generation because of poor material flow and there is deterioration in roundness.

Lower feed rates however yield longer time for heating and softening of the material. This leads to a better roundness achieved from the material deformation. Higher feed rates lead to intermittent tool-material contacts which result in uneven deformation of the material and thus may result in reduced roundness of the product. At this very low feed rates the large amount of heat developed can be harmful on hole geometry and roundness. Drilling of thicker workpieces takes more time and more heat generation. When heat generation is not sufficient, it deteriorates the roundness of material due to uneven deformation. Larger drills necessitate increased energy to produce adequate heat over an increased contact area. Suboptimal spindle speed and feed rate may lead to uneven deformation, adversely affecting the roundness. Reducing the drill diameter generates heat rapidly due to increased friction, frequently resulting in enhanced roundness. Conversely, excessive heat may induce local deformation, drastically affecting roundness.

Machine learning

ML is an AI field that allow the system to make predictions. The supervised, unsupervised, and reinforcement learning key types solve the different tasks46,47. Schematic of ML workflow follows input data acquisition and data cleaning to remove inconsistencies, missing values, and outliers and a high-quality data set. This is followed by feature engineering where selected relevant features and transform them such that they describe good patterns within the data to maximize the prediction performance as exhibited in Fig. 8. The engineered features are then learned upon by learning algorithms, and the model trained is compiled from the learning algorithms to identify patterns and relationships through the data. In order to validate model effectiveness and generalize the model, a separate data subset that is not used to fit model is set aside solely for performance evaluation. Now the model is trained and evaluated over the test data in terms of metric such as accuracy, precision, recall on how predictive and practically relevant the model is.

Algorithms used

Multilayer perceptron

The MLP is one of the foundation neural network48,49 models in supervised learning application has been used in classification and regression tasks as shown in Fig. 9. The network is composed of an input layer, several (or one) hidden layers which feed into an output layer of interconnected neurons weighted to affect signal strength across connections. MLPs introduce nonlinearity into the sum by applying an activation function, like ReLU, sigmoid, or tanh to each neuron. Algebraic methods are applied during training to an MLP, which attempts to adjust weights iteratively, minimizing error from predictions. In this study, the following hyperparameters were used: two hidden layers with 64 and 128 neurons, ReLU activation function, a learning rate of 0.0001, batch size of 32, and trained over 50 epochs. However, this process is highly dependent on a few hyper parameters such as the number of hidden layers, number of neurons per layer, and the learning rate & etc., which are all optimized so to achieve better performance. But when it comes to data, the models are highly adaptable and it has been applied to image recognition, natural language processing, and financial forecasting, among others, because it model complex relationships between the data. In particular, is a valuable benchmark model of choice in research, as it is reliable and interpretable, and serves as a source against which to compare more advanced deep learning methods.

Gaussian process regression

The GPR is a popular non parametric, probabilistic model for regression tasks because of its flexibility and its capacity to provide uncertainty estimates50. The GPR models consider a Gaussian distribution over functions, representing a prior distribution over these functions that describe their characteristics as displayed in Fig. 9. The main components of GPR are its use of a kernel (or covariance) function that determines the smoothness, periodicity, etc., of the predicted function and the similarity between the input data points. In this work, the Radial Basis Function (RBF) and Matern kernels were explored. Hyperparameters such as kernel type, length-scale (optimized via maximum likelihood estimation), and noise level (set based on data variance) were used to tune the model. GPR forms a posterior distribution based on the prior and the observed data, and additionally is able make predictions for new points with confidence intervals. The key ability to quantify uncertainty of GPR, makes it particularly useful when the reliance on the prediction reliability is the critical factor, as in scientific experiments or complex engineering tasks. While GPR is computationally expensive for big datasets, its related regression remains a powerful interpretable and robust choice when high quality predictions and uncertainty are needed in research.

Support vector machines

SVM is one of the most powerful supervised learning algorithms widely used for classification as well as regression task51. SVM works by trying to find the optimum hyper plane(s) which maximize the margin separating the data points of the different classes enhancing models generalization capability (Fig. 9). SVM implicitly transforms its data to a higher dimensional space where it is linearly separable using a kernel trick, in cases that the data are not linearly separable. There are a variety of popular kernel functions, such as linear, polynomial and radial basis function (RBF) which are selected according to the data distribution as well as the problem requirements. In this study, the RBF kernel was employed with the following hyperparameters: regularization parameter (C) = 1.0, kernel coefficient (gamma) = ‘scale’ (i.e., 1 / number of features), and epsilon = 0.1 to define the insensitive loss margin. Support vectors are critical, for they are the data points furthest away from the hyperplane and in which define the margin. SVM is robust to high dimensional data, performs quite well in the situation of limited samples, and is quite resistant to overfitting. SVM, as it is highly versatile and effective at dealing with complex decision boundaries, is also useful in applications for textual classification and image recognition, in bioinformatics and many others—SVM is thus a very used ML tool for work on research and applied ML.

Random forest

RF is an ensemble ML model, known particularly for its high robustness and accuracy in both classification and regression27. RF extends decision tree algorithm by building a large number of decision trees during training and each decision tree is built on a random subset of training data known as bootstrap aggregation or bagging. RF achieves better generalizability by aggregating (average for regression and vote for classification) outputs of multiple trees thereby reducing the chances of the overfitting (Fig. 9). Moreover, each tree in the forest is trained on a different random sample, and only a subset of features is considered in deciding to split at any given node (further reducing variance), while also making the model capable of handling high dimensional data and complex interaction structures amongst variables. In this study, the following hyperparameters were employed: number of trees = 100, maximum depth = None, minimum samples per split = 2, max_features = ‘auto’, and a fixed random_state to ensure reproducibility. The ease of use of RF is driven by its minimal tuning of hyper parameters, like the number of trees or the number of features considered per split. These qualities make RF popular on its own but also serve as strong baselines on complex predictive tasks, such as bioinformatics and finance, image analysis, and others.

Prediction with ML models

Analyses on the basis of prediction have been carried out by comparison among the measured values (i.e. actual data), and the predicted values (i.e. model output) in order to check the performance of different ML models, especially on how much the predictions of each model have been to the true values. In this research work training split of 80% and testing split of 20% is used. Ideally, these points should lie along a 45-degree line, or line of perfect prediction, where points of prediction exactly match those of measurement. The RF model showed an excellent alignment of its points being close together when following this line in both training and testing phases. The clustering is tight suggesting that there is a strong correlation between the measured and predicted values and therefore the RF model has with high accuracy captured the underlying patterns in the data. Figure 10 exposed that fit matched better than the other models, including MLP, SVM and GPR, in which points scattered away from the line more profoundly, particularly during testing. Thus, demonstrates the RF model’s performance is robust and reliable, and reliable enough to infer the RF model’s accuracy when predicting on new, unseen data.

Evaluation metrics

The predictive performance of four ML models (MLP, GPR, SVM, and RF) was evaluated using R-squared (R²), Mean Absolute Error (MAE), Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE), Relative Absolute Error (RAE), and Root Relative Squared Error (RRSE) in bushing thickness.

MLP showed great predictive accuracy during training, giving an R² of 0.9884, MAE of 0.0489 and RMSE of 0.0633, with excellent precision. RF equally performed well, with R² of 0.9875 and slightly lower MAE (0.0353) and RMSE (found to be 0.0656), while maintained the small relative error (RAE of 0.12774 and RRSE of 0.18876). Although only accurate with an R² above 0.8974, GPR had higher errors (MAE = 0.09, RMSE = 0.1656) and SVM performed similarly with an R² of 0.9007. In testing, the models GPR and SVM outperformed other models with R² values of 0.9964 and 0.9921, respectively and RF had R² of 0.9632. Testing out MLP’s performance resulted in an R² of 0.922, higher errors (MAE of 0.3188 and RMSE of 0.448), and a sign that MLP was overfitting while training. The results highlight that while MLP and RF models proved highly effective on the training data, GPR and SVM showed much better generalization performance on the testing set, since the latter models showed robustness and ability to work with new data (Fig. 11).

During training, for bushing length, RF was the most accurate model with R² = 0.9954, and MAE 0.1508 and RMSE 0.2457. Besides, in training stage, MLP performed very well with R² of 0.9868 but yielded higher MAE of 0.2988 than RF. However, GPR exhibited R² of 0.8223 and relatively higher errors were not as suitable for training accuracy. RF was tested again which once again had superior performance, with an R² of 0.9847, MAE of 0.3, and RMSE of 0.3. This showed very strong generalization performance and predictive accuracy on prediction data never seen before. Testing also yielded good performance with SVM (R² value = 0.969) and GPR (R² value = 0.9636), although with higher error rates than RF. However, RF was the best model in both training and testing phases; it had good accuracy and reliability making it the best candidate for robust prediction.

During training, the roundness was best predicted by RF, with an R² of 0.9892, an MAE of 0.0018, RMSE of 0.0021, signifying its ability to capture underlying data patterns. In terms of training performance, SVM also performed well with R² of 0.92, and MAE of 0.0038, but not as robust as RF. The RF performed exceptionally well during our testing with an R² value of 0.9234, an MAE of 0.0032, and an RMSE of 0.0036, indicating it is adept at generalization on unseen the data. GPR also showed good generalization with an R² of 0.8377 and the lowest MAE of 0.0029 in testing, though RF maintained a lower RMSE and higher overall R². Thus, RF was the most accurate model during training and testing, therefore the best choice for reliable and accurate prediction in this study.

Conclusions

The current study exhibits the significance of processing conditions of friction drilling of AMCs such as spindle speed, feed rate, workpiece thickness, and drill diameter in development of the bushing length, thickness, and roundness.

-

Aluminium matrix is softened and longer bushing lengths are formed due to controlled material flow and extrusion caused by higher spindle speeds. Consequently, aluminium matrix is softened and longer bushing lengths are formed. Uniform and longer bushings are delivered by Lower feed rates. Longer tool-material interaction and generation of more heat ensure superior bushings in terms of length and uniformity. However higher feed rates minimize heat generation resulting in partial material flow and shorter bushings.

-

With improper feed rate and spindle speed, excess material comes out while using larger drill diameters and result in thicker bushings. While, thinner workpieces result in thinner bushings due to insufficient material supply and displacement.

-

Excessive heat produced by higher spindle speeds, causes uneven plastic deformation and a decrease in roundness values. Longer tool-material interaction at lower feed rates, improves roundness due to uniform material deformation.

-

The evolution of microstructural changes across the bushing zones is observed in the SEM micrographs and particle analysis. Both the Head and Tail Petal Regions experienced disruption of material flow and have rough surfaces and fragmented particles. However, the Upper Critical Region, experienced perfect mechanical and thermal conditions resulting with its smooth and aligned microstructures. Microstructural characteristic are essential inputs for optimization of friction drilling parameters and enhancement of surface quality and minimising flaws.

-

Different zones in the bushing indicates the interlinked thermal and mechanical effects during the process of friction drilling. In both Head Petal and Tail Petal Regions, significant plastic deformation took place, and coarse grains in the range of 20–40 μm are observed. Dynamic recrystallization ensured the finest grains in the Upper Critical Region (Zone C).

-

The extensive impact of mechanical and thermal effects during the drilling process is demonstrated by the examination of surface topography throughout the bushing zones in the friction drilling of snail shell-reinforced aluminum matrix composites. Head Petal Region (Zone A) has the maximum surface roughness of 20 μm, with deep valleys and abrupt peaks, as a result of significant plastic deformation and insufficient material flow during the tool’s first contact. Particle fragmentation and uneven surface texturing are the results of inadequate thermal softening and material flow interruption. The fine surface texture with the lowest roughness in the range of 3–5 μm that has few peaks and shallow troughs is found in the Upper Critical Region (Zone C). The optimum surface quality is achieved across this zone because of homogeneous material flow and dynamic recrystallization.

-

In this work, distinct ML models (MLP, RF, SVM, and GPR) were employed for prediction. Each model responds differently in the testing and training phase when predicting the responses (Bushing length, Bushing thickness, and Roundness).

-

Friction drilling of Aluminium matrix composites (AMCs) with green reinforcement of snail shell opens possibilities of various high strength and lightweight structural materials deployed in automotive applications. Also, open gate ways for novel sustainable composites in various engineering deployments.

-

Bush formation is a critical affair and challenge in AMCs. Hence, the quality optimization of processing conditions assists in tackling challenges.

-

Robust bush formations can be realised though advanced temperature monitoring systems and studies.

-

Elaborated future research, establish platforms for AMCs with different sustainable reinforcements for friction drilling.

Data availability

The datasets used and analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Hariyani, D. et al. Drivers and motives for sustainable manufacturing system. Innov. Green. Dev. 2, 100031. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.igd.2022.100031 (2023).

Korkmaz, M. E. et al. Implementation of green cooling/lubrication strategies in metal cutting industries: A state of the Art towards sustainable future and challenges. Sustain. Mater. Technol. 36, e00641. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.susmat.2023.e00641 (2023).

Onifade, M. et al. Advancing toward sustainability: the emergence of green mining technologies and practices. Green. Smart Min. Eng. 1, 157–174. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gsme.2024.05.005 (2024).

Surya, M. Optimization of machining parameters while turning AISI316 stainless steel using response surface methodology. Sci. Rep. 14, 30083. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-78657-z (2024).

Bose, S., Mandal, N. & Nandi, T. Selection and experimentation of the best hybrid green composite using advanced MCDM methods for clean sustainable energy recovery: A novel approach. Int. J. Math. Eng. Manag Sci. 5, 556–566. https://doi.org/10.33889/IJMEMS.2020.5.3.046 (2020).

Khashay, M. et al. Elevated temperature and pressure performance of water based drilling mud with green synthesized zinc oxide nanoparticles and biodegradable polymer. Sci. Rep. 15, 11930. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-96900-z (2025).

Sakao, T. et al. Implementing circular economy activities in manufacturing for environmental sustainability. CIRP Ann. 73, 457–481. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cirp.2024.06.002 (2024).

Tolcha, M. A., Lemu, H. G. & Adugna, Y. W. Optimizing economics of machining for LM25Al/VC composite material using analytical modeling, deep neural network and GRA coupled with RSM. Sci. Rep. 15, 10215. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-95446-4 (2025).

Lakshmanan, R. et al. The convergence of lean management and additive manufacturing: case of manufacturing industries. Clean. Eng. Technol. 13, 100620. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clet.2023.100620 (2023).

Manikanta, J. E. et al. Analysis of machining performance in turning with trihybrid nanofluids and minimum quantity lubrication. Sci. Rep. 15, 12194. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-97039-7 (2025).

Soori, M. et al. Sustainable CNC machining operations, a review. Sustain. Oper. Comput. 5, 73–87. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.susoc.2024.01.001 (2024).

Li, D. et al. Influence of drilling incidence angle on the drilling force distribution of pneumatic impactor. Sci. Rep. 15, 2098. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-86071-2 (2025).

Du, X. et al. Probing the tribology and drilling performance of high performance cutting fluid on inconel 690 Superalloy by minimum quantity lubrication technology. Alex Eng. J. 88, 58–67. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aej.2024.01.002 (2024).

Sankaranarayanan, R. et al. Bio-coolants for sustainable friction drilling process: A machine learning approach to temperature reduction. RINENG 26, 104959. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rineng.2025.104959 (2025).

Pramanik, A. et al. Sustainability in drilling of aluminum alloy. Clean. Mater. 3, 100048. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clema.2022.100048 (2022).

Teimouri, R., Amini, S., Lotfi, M. & Alinaghian, M. Sustainable drilling process of 1045 steel plates regarding minimum energy consumption and desired work quality. Int. J. Light Mater. Manuf. 2, 397–406. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijlmm.2019.04.011 (2019).

Hamzawy, N. et al. Investigation of Temperature Variation During Friction Drilling of 6082 and 7075 Al-Alloys. In: Tomsett, A. (eds) Light Metals 2020: The Minerals, Metals & Materials Series. 471–477 (Springer, Cham, 2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-36408-3_67

Abdalkareem, A. et al. Thermal management of Friction-Drilled A356 aluminum alloy: A study of preheating and drilling parameters. J. Manuf. Mater. Process. 8, 251. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmmp8060251 (2024).

Khedr, M. et al. Improved mechanical behavior of friction stir drilled 6082 aluminum alloy via T6 treatment. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 31, 2774–2785. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmrt.2024.06.189 (2024).

Ke, F., Ni, J. & Stephenson, D. A. Continuous chip formation in drilling. Int. J. Mach. Tools Manuf. 45, 1652–1658. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijmachtools.2005.03.011 (2005).

Kumar, R. & Jesudoss Hynes, N. R. Thermal drilling processing on sheet metals: A review. Int. J. Light Mater. Manuf. 2, 193–205. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijlmm.2019.08.003 (2019).

Dehghan, S., Soury, E. & Ismail, M. I. S. b. A comparative study on machining and tool performance in friction drilling of difficult-to-machine materials AISI304, Ti-6Al-4V, Inconel718. J. Manuf. Process. 61, 128–152. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmapro.2020.10.078 (2021).

Albarbary, Y. E. et al. The effect of pre-drilling on the characteristics of friction drilled A356 cast aluminum alloy. J. Manuf. Process. 82, 646–656. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmapro.2022.08.040 (2022).

Hynes, N. R. J. et al. Decision tree approach based green flow-drilling of hybrid aluminium matrix composites using eco-friendly coolants. J. Manuf. Process. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmapro.2022.05.050 (2022).

Selvaraj, R. M. & Hynes, N. R. J. A review of process parameters in friction drilling on joining of steels. Arch. Mater. Sci. Eng. 119, 12–20. https://doi.org/10.5604/01.3001.0016.3149 (2023).

Vanhove, H., Ozden, E. & Duflou, J. R. An experimental study on bushing formation during friction drilling of titanium grade 2 for medical applications. J. Manuf. Mater. Process. 7, 220. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmmp7060220 (2023).

Sankaranarayanan, R. et al. Random decision forest based sustainable green machining using citrullus lanatus extract as bio-cutting fluid. J. Manuf. Process. 68, 1814–1823. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmapro.2021.07.014 (2021).

Basavarajappa, S., Chandramohan, G. & Davim, J. P. Some studies on drilling of hybrid metal matrix composites based on Taguchi techniques. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 196, 332–338. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmatprotec.2007.05.043 (2008).

Aamir, M. et al. A review: drilling performance and hole quality of aluminium alloys for aerospace applications. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 9, 12484–12500. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmrt.2020.09.003 (2020).

Lostado-Lorza, R., Corral-Bobadilla, M., Íñiguez-Macedo, S. & Somovilla-Gómez, F. Characterization, LCA and FEA for an efficient ecodesign of novel stainless steel woven wire mesh reinforced recycled aluminum alloy matrix composite. J. Clean. Prod. 411 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2023.137380 (2023).

Selvan, C. P. et al. Optimization of stir casting and drilling process parameters of hybrid composites. J. Alloy Metall. Syst. 3, 100023. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jalmes.2023.100023 (2023).

Saini, D. K. & Jha, P. K. Fabrication of aluminum metal matrix composite through continuous casting route: A review and future directions. J. Manuf. Process. 96, 138–160. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmapro.2023.04.041 (2023).

Hynes, N. R. J. et al. A comparative study of the mechanical and tribological behaviours of different aluminium matrix–ceramic composites. J. Brazilian Soc. Mech. Sci. Eng. 41 https://doi.org/10.1007/s40430-019-1831-7 (2019).

Xu, J. et al. A critical review addressing conventional twist drilling mechanisms and quality of cfrp/ti stacks. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 24, 6614–6651. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmrt.2023.04.226 (2023).

Dehghan, S. et al. A novel approach to friction drilling process: experimental and numerical study on friction drill joining of dissimilar materials AISI304/AL6061. Met. (Basel). 12, 920. https://doi.org/10.3390/met12060920 (2022).

Ross, N. S. et al. Measuring surface characteristics in sustainable machining of titanium alloys using deep Learning-Based image processing. IEEE Sens. J. 23, 13629–13639. https://doi.org/10.1109/JSEN.2023.3269529 (2023).

Karabacak, Y. E. Intelligent milling tool wear Estimation based on machine learning algorithms. J. Mech. Sci. Technol. 38, 835–850. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12206-024-0131-z (2024).

Ross, N. S. et al. Enhancing surface quality and tool life in SLM-machined components with Dual-MQL approach. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 31, 1837–1852. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmrt.2024.06.183 (2024).

Elangovan, M. et al. Machine learning approach to the prediction of surface roughness using statistical features of vibration signal acquired in turning. Procedia Comput. Sci. 50, 282–288. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.procs.2015.04.047 (2015).

Flegner, P. et al. Application of cluster analysis for classification of vibration signals from drilling stand aggregates. Appl. Sci. 13, 6337. https://doi.org/10.3390/app13106337 (2023).

Seetharaman, S. et al. Mechanical properties of sustainable metal matrix composites: A review on the role of green reinforcements and processing methods. Technol 10, 32. https://doi.org/10.3390/technologies10010032 (2022).

Oladele, I. O. et al. Sustainable composites reinforced with glass fiber and bio-derived calcium carbonate in recycled polypropylene. Hybrid. Adv. 8, 100357. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hybadv.2024.100357 (2025).

Hirianiah, C. S. R. A., Harishanad, K. S. & Noronha, N. P. A review on hot extrusion of metal matrix composites. Int. J. Eng. Sci. 1, 1–35 (2012).

Fajdek-Bieda, A. & Wróblewska, A. The use of natural minerals as reinforcements in Mineral-Reinforced polymers: A review of current developments and prospects. Poly (Basel). 16, 2505. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym16172505 (2024).

Seetharaman, S. et al. Mechanical properties of sustainable metal matrix composites: A review on the role of green reinforcements and processing methods. Technologies 10, 32. https://doi.org/10.3390/technologies10010032 (2022).

Ross, N. S. et al. Carbon emissions and overall sustainability assessment in eco-friendly machining of Monel-400 alloy. Sustain. Mater. Technol. 37 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.susmat.2023.e00675 (2023).

Presciuttini, A. et al. Machine learning applications on IoT data in manufacturing operations and their interpretability implications: A systematic literature review. J. Manuf. Syst. 74, 477–486. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmsy.2024.04.012 (2024).

Anburaj, R., Pradeep Kumar, M., Navin Kumar, B. & Ross, N. S. Enhancing machining performance of inconel 625 through cryogenic cooling in face milling-EDAS optimization and AI prediction. Mater. Manuf. Process. 40, 1365–1377. https://doi.org/10.1080/10426914.2025.2507078 (2025).

Boukredera, F. D. et al. Enhancing the drilling efficiency through the application of machine learning and optimization algorithm. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 1, 107035. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engappai.2023.107035 (2023).

Cica, D., Sredanovic, B., Tesic, S. & Kramar, D. Predictive modeling of turning operations under different cooling/lubricating conditions for sustainable manufacturing with machine learning techniques. Appl. Comput. Inf. 20, 162–180. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aci.2020.02.001 (2024).

Selvanayaki, M., Vijaya, M. S. & Jamuna, K. S. and SK Supervised Learning Approach for Predicting the Quality of Cotton Using WEKA. In: Das, V.V., et al. (eds) Inform Process and Manag: BAIP 2010–Commun in Comp and Inform Sci. 70. (Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, 2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-12214-9_61

Acknowledgements

The author Rajesh Jesudoss Hynes Navasingh, gratefully acknowledges the award of the Ulam NAWA Postdoctoral Fellowship of the Polish National Agency for Academic Exchange programme, Contract Agreement No. BPN/ULM/2022/1/00133/U/00001. The authors extend their acknowledgement to the financial support of the European Union under the REFRESH-Research Excellence For REgion Sustainability and High-tech Industries project number CZ.10.03.01/00/22_003/0000048 via the Operational Programme Just Transition.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: Rajesh Jesudoss Hynes Navasingh; Investigation: Rajesh Jesudoss Hynes Navasingh and R. Sankaranarayanan; Methodology: R. Sankaranarayanan, Priyanka Mishra, Jebasingh Jeremiah Rajesh; Data Analysis: Priyanka Mishra and Jebasingh Jeremiah Rajesh; Supervision: Rajesh Jesudoss Hynes Navasingh and J. Angela Jennifa Sujana; Writing – original draft, Rajesh Jesudoss Hynes Navasingh, R. Sankaranarayanan and Priyanka Mishra; Writing – review & editing, J. Angela Jennifa Sujana and Jana Petru. Funding—Jana Petru.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Navasingh, R.J.H., Sankaranarayanan, R., Mishra, P. et al. Evaluating microstructural and machine learning predictive models for friction drilling of sustainable snail shell reinforced aluminium matrix composites. Sci Rep 15, 28336 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-12555-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-12555-w