Abstract

Studies show that athletes have better trust behaviors than ordinary college students, likely due to their long-term sports training. However, the impact of sports training may vary with the team-based nature of the sports. It’s still unclear whether there are differences in interpersonal trust behaviors and neural mechanisms among athletes from different types of teams. This study compared the differences in these aspects between athletes from cooperative-competitive teams and those from competitive-cooperative teams. Our study recruited 48 athletes dyads. 24 dyads were from team sports (e.g., basketball, soccer) and were grouped into the cooperative-competitive group (cooperation group), since their training involved more cooperation than competition, including 12 male and 12 female dyads. The other 24 dyads, from individual sports (e.g., athletics, tennis), formed the competitive-cooperative group (competitive group), as their training was more competitive than cooperative, and also included 12 male and 12 female dyads. A two-factor experimental design was used. During trust-game tasks, interpersonal trust behaviors and prefrontal interpersonal neural synchronization (INS) changes were monitored in real time via functional Near-infrared Spectroscopy (fNIRS) hyperscanning. Behaviorally, the cooperation group showed more investment behaviors in trust games than the competition group. In brain data, during investment decisions, female athletes in the cooperation group had stronger left frontal lobe INS than those in the competition group. Also, in the competition group, female athletes showed stronger left dorsolateral prefrontal INS during investment decisions than male athletes. The study indicates that team type and sex significantly affect athletes’ interpersonal trust behaviors, along with specific brain area INS changes. It offers a new angle for research on sports training and trust behavior, filling a gap in the field.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Trust is a psychological state in which individuals are willing to entrust their resources to others and take on the corresponding risks when facing social uncertainty1. As a key element in the evolution of human society, trust plays a pivotal role in social development. In the field of psychology, the evaluation of interpersonal trust is often conducted through trust-game tasks2.Trust-building theories emphasize that individuals can gradually establish deep trust relationships through long-term interaction and information exchange. Attachment theory points out that stable and positive interaction patterns help form secure attachment relationships, promoting trust development3. Social exchange theory further explains that trust is based on reciprocal behavior, resource exchange relationships and is gradually established through long-term positive communication and reciprocal actions4. It can be seen that interpersonal trust is gradually formed through long-term positive interactions.

Interpersonal trust is crucial in sports and significantly impacts team performance5. Theoretical analyses have shown that long-term sports training is essential for athletes to build mutual trust6. Furthermore, cross-sectional studies have found that athletes exhibit better interpersonal trust than college students, indicating a potential link between long-term sports training and enhanced trust behaviors in athletes7. However, long-term sports training can be influenced by the type of team athletes are in. For example, sports like basketball and volleyball focus more on team-collaboration tactics and less on individual competition during training, while sports like track-and-field and boxing center more on individual skill development and less on team-cooperation tactics. Since in reality, athletes are never in a purely individual or team-based training state, with competition and cooperation always co-existing, only their proportions differ. Thus, teams can’t be simply classified as team or individual sports. Based on the interplay of cooperation and competition in sports training and theory of cooperation and competition8, this study divides team types into cooperative-competitive and competitive-cooperative teams8,9. Cooperative-competitive teams, formed via functional integration of members, feature interdependence, close collaboration, stable interaction, and frequent positive communication, and are common in sports like basketball, soccer and volleyball10. Competitive-cooperative teams are built on a parallel member structure. Member relationships are relatively independent, individuals can accomplish team goals on their own, and the need for cooperation is less intense, which can be seen in athletics, tennis, boxing, etc11.

At present, few in-depth studies in the academia focus on the differences in trust behaviors among athletes from different team types. Most sports researchers concentrate on team cohesion and trust behaviors in single team sports. For instance, Huang et al.12 studied Chinese volleyball teams, explored the characteristics of team cohesion, and offered cultivation suggestions. Fei13 measured and analyzed team cohesion and trust levels in China’s National Volleyball League teams and found a high correlation between these levels and team strength, sports performance. Zhang14 studied 8 Chinese college basketball teams and discovered that an evaluation system based on team cohesion is highly effective for predicting team performance. Dou15 examined team efficiency of high-level collective ball sports teams in Chinese universities and found that these teams have strong team trust. These studies have laid a solid theoretical foundation for research on the relationship between team sports and interpersonal trust. However, existing studies have limitations as they fail to consider that athletes in individual sports also experience team atmosphere and cooperation demands. Thus, it is necessary to classify team types into cooperative-competitive and competitive-cooperative teams, and investigate the differences in trust behaviors between these two types. Previous research has confirmed that long-term sports training can shape trust behaviors. Given that cooperative-competitive team training emphasizes athlete interaction and cooperation, this study hypothesizes that athletes in cooperative-competitive teams have stronger interpersonal trust levels than those in competitive-cooperative teams.

Recent advances in cognitive neuroscience have provided reliable technical support for exploring the neural mechanisms of interpersonal trust in athletes. Functional Near-infrared Spectroscopy (fNIRS) has become an effective tool for this purpose due to its cost-efficiency, ease of use, and high tolerance to motion artifacts16,17. Its hyperscanning technique can monitor interpersonal interactions in real-time and assess interaction quality by analyzing interpersonal neural synchronization18,19. Evidence from hyperscanning studies indicates that the prefrontal cortex is a key brain region for competition and cooperation20,21. Research has found that compared with competition, cooperation leads to better INS in the prefrontal cortex, and male groups show stronger INS than female groups after cooperation22. In the field of interpersonal trust, hyperscanning studies have revealed that the prefrontal cortex (PFC) plays a crucial role in trust decisions and cooperative interactions, as it is vital for understanding others’ intentions and emotions23. For example, Wu et al.24 used trust-game tasks and fNIRS hyperscanning technology and found that individuals from one-child families exhibit less reciprocal and cooperative behavior and lower INS in the medial prefrontal cortex. Similarly, Cheng et al.25 found that the social identity of interacting agents affects interpersonal trust behavior and that INS in the right dorsolateral prefrontal cortex can predict investment performance. These studies highlight the central role of the prefrontal cortex in interpersonal trust.

A recent cross-sectional fNIRS hyperscanning study explored the link between sports and interpersonal trust. Using a trust-game task and fNIRS hyperscanning technology, it compared trust behaviors between athletes and college students. Results showed athletes had better interpersonal trust behaviors than college students, with stronger INS in the left frontal lobe and left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex; Male athletes also had better trust behaviors and stronger INS in left dorsolateral prefrontal than females7. This suggests athletes’ trust behavior advantage may relate to enhanced prefrontal INS, with sex differences involved. However, research on sports and interpersonal trust is still in its early stages, with many gaps to fill, especially regarding the neural mechanisms of interpersonal trust behaviors in different team-type athletes. Based on prior studies, this study hypothesizes that cooperative-competitive team athletes have better prefrontal neural activities in trust decisions than competitive-cooperative team athletes, and male athletes have better trust decisions and INS.

In summary, this study used fNIRS hyperscanning to monitor real-time INS in the prefrontal cortex of athletes from different team types during a trust-game task. A two-factor experimental design tested the hypothesis that team type and sex significantly affect athletes’ interpersonal trust behaviors and INS in specific prefrontal areas.

Materials and methods

Participants

This study successfully recruited 96 college athletes from a university in China (for detailed information, see Table 1). The sample had a balanced sex distribution, with ages ranging from 18 to 23 (mean: 20.12 ± 1.28). All athletes were certified as national first-or second-tier athletes under China’s Sports Law, with 5–16 years of training (mean: 8.99 ± 3.23). The recruited athletes included: basketball (6 males, 4 females), football (6 males, 6 females), volleyball (8 males, 8 females), gymnastics (4 male, 6 females), tennis (4 males), table tennis (10 females), badminton (8 males, 6 females), track and field (8 males, 8 females), and boxing (4 males).

Athletes of the same sport and sex were paired (e.g., female table tennis-female table tennis, male volleyball-male volleyball). 24 dyads of athletes (12 male and 12 female dyads) were assigned to the cooperation-competition group, and another 24 dyads (12 male and 12 female dyads) to the competition-cooperation group. To facilitate further discussion, the cooperation-competition group and competition-cooperation group are respectively abbreviated as the “cooperation group” and “competition group” in this paper. All dyads were fully informed about the experimental procedure and tasks, and signed consent forms. The study was approved by the Human Ethics Committee of East China Normal University (HR 449–2020). All participants signed an informed consent form before the experiment. Confirm that all experiments were conducted in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Experimental procedure

Upon arriving at the laboratory, each dyad first completed a demographic questionnaire (covering age, sex, year of experience, and skill level) and other relevant questionnaires (see “Questionnaires”). This ensured basic homogeneity across groups. The experimenter then explained the experimental procedure and tasks. Once both participants were familiar with the tasks, the experiment began.

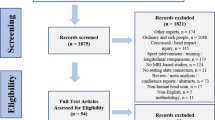

The dyads sat opposite each other at a table, each with a 23.8-inch computer screen. This setup isolated their lines of sight to eliminate potential social interaction effects. They then put on near-infrared electrode caps and rested for 1 min to relax. Next, they performed the trust-game task2, an experimental economics task measuring interpersonal trust. After the task, the experimenter helped remove the fNIRS caps, thanked the dyads, and informed them the experiment was over. They then left the laboratory (see Fig. 1).

Trust game task

In this study, the trust game task2 was implemented through Experimenter’s Prime2.0 software(E-prime 2.0) programming.

(https://support.pstnet.com/hc/en-us/categories/204131827-E-Prime-2-x). It included a 30-s rest before the experiment and 12 game rounds. To prevent dyads from predicting the number of rounds, the exact number wasn’t disclosed.

Each round of the trust game is divided into three stages (see Fig. 2): the investment stage, the return stage, and the outcome stage. In the investment stage, investors were shown a prompt screen with an initial fund of 10 yuan (the actual amount varied randomly). They had to decide how much (0–10 yuan) to invest in the trustee. Meanwhile, trustees were shown a screen to wait for the investor’s decision. After the decision, there was a 1-second delay with a blank black screen. Then, in the feedback stage, the screen displayed each participant’s currency units for 2 s. In the return stage, trustees were informed of their money (three times the investment) and decided how much to return. Investors saw a screen waiting for the trustee’s decision. Finally, in the outcome stage, a 2-s screen showed each dyad’s total money after the decisions.

After each round, earnings were reset, and the next round started with the same initial fund. Results of each round were automatically recorded. After 12 rounds, researchers calculated each participant’s total earnings and allocated actual rewards proportionally.

Questionnaires

Profile of mood states scale (POMS)

Compiled by DM Mc Nair in198426 and revised by Professor Bili Zhu from East China Normal University27. The POMS has a reliability of 0.60–0.82, averaging 0.71. It contains 40 items rated on a 0–4 scale, with six subscales: Tension, Anger, Fatigue, Depression, Vigor, and Confusion, plus a Self-Esteem subscale. The mood score is calculated as: Total Mood Score = Sum of five negative mood scores-Sum of two positive mood scores + 100 (range 100–200). Participants with scores above 120 indicating poor mental health were excluded. This study used it to filter out participants with poor pre-experiment mood states.

Interpersonal trust scale (ITS)

Developed by Rotter JB in 196728, the ITS has 25 items rated on a 1–5 Likert scale (from “Strongly Agree” to “Strongly Disagree”). stronger scores indicate stronger trust. With a split-half reliability of 0.76 and good construct validity, it shows no sex differences and good discriminant validity. This study applied it to assess dyads’ pre-experiment interpersonal trust levels.

Cooperative and competitive personality scale (CCPS)

Compiled by Xie Xiaofei and Yu Yuanyuan in 200629, the CCPS consists of 23 items divided into cooperation and competition subscales. The cooperation subscale covers reciprocity, acceptability, and willingness to socialize (13 items), while the competition subscale includes self-growth, rivalry, and over-competition (10 items). Stronger scores signify better personality traits. The cooperation and competition subscales have reliabilities of 0.85 and 0.71, respectively, and good construct validity via confirmatory factor analysis. In this study, participants with extreme cooperation or competition scores (top and bottom 27%) were excluded to ensure no significant differences in these tendencies across groups and prevent impacts on experimental results.

fNIRS equipment

Brain activity data during the experiment were collected using a Hitachi ETG-7100 optical topography system. It measured changes in oxygenated and deoxygenated hemoglobin concentrations with 695 nm and 830 nm light waves at a 10 Hz sampling frequency to ensure data accuracy and continuity.

The fNIRS electrode cap’s probes were placed on participants’ foreheads, covering the prefrontal cortex. The probes included 8 emitters and 7 detectors spaced 3 cm apart, forming 22 measurement channels (see Fig. 3). Using the 10–20 International System for positioning, the center detector of the central probe was located at the Fpz site. The probe layout was aligned along the midline from the nasion to the inion for accurate measurement. The specific spatial locations of the channels were determined using the virtual localization tool from Jichi Medical University (available online at http://www.jichi.ac.jp/brainlab/virtual_registration/Result3x5_E.html). Moreover, channel coordinates were mapped onto the Montreal Neurological Institute (MNI) space using the NIRS-SPM software, thereby determining the exact anatomical locations of each channel (see Supplementary Table S1).

fNIRS preprocessed

Data were preprocessed in the Matlab (2014a) environment. Given that oxygenated hemoglobin (Hbo) is more sensitive to task stimulation, only Hbo was analyzed in this study. The PCA algorithm was applied to eliminate global components unrelated to the task30. Wavelet transform coherence (WTC)31, which measures the cross-correlation of two time-series varying with frequency and time, was used. Based on prior studies20,32,33, this study also used WTC to transform Hbo signals from corresponding channels of the two participants, generating a time-frequency coherence map. Visual inspection found stronger synchrony in the 0.010–0.019 Hz band (51.2–102.4 s) (see Fig. 4A). Previous research has proven that low-frequency oscillations (usually in the 0.01–0.10 Hz range) are more reliable intra-neuronal synchronization markers than high-frequency ones34.

To accurately identify the frequency range closely related to interpersonal trust, paired t tests were performed on the average data of each channel during the trust-game and rest periods across the entire frequency range33. The analysis focused on the 0.001–0.10 Hz band. After FDR correction (p < 0.05), significant task-related increases in INS were found in the 0.010–0.017 Hz band (60–100-s period) (see Fig. 4B), which matched the visual-inspection results, covered the decision-making time (20 s) of a game round, and avoided high frequency (e.g., cardiac, ~ 0.7–4 Hz) and low-frequency (e.g., respiratory, 0.2–0.3 Hz) noise21.

The difference between the INS during the trust-game task and during the initial rest period was calculated and averaged to represent the increase in synchrony32. These values were fisher z-transformed for further analysis. Single-sample t tests (with FDR correction) were conducted to identify channels with significant increases in INS, which were then selected as regions of interest. Finally, the results were visualized into 3D brain mapping images using the xjview toolbox.

(http://www.alivelearn.net/xjview8/) and the BrainNet Viewer toolbox.

Time-frequency plots. A Wavelet Transform Coherence (WTC) spectrum of HbO signals from channel 20 of the experimental group. stronger synchrony, coded in red, is in the task frequency band (0.010–0.019 Hz). B Paired t test plot for task vs. rest across 0.01–0.1 Hz. It shows stronger INS during tasks than rest at 0.010–0.017 Hz, covering the decision-making duration.

To ensure that the observed INS was due to the “interactive cognitive tasks” between participants rather than just “similar cognitive tasks”, this study used a Permutation Test to validate the synchrony’s credibility. This method differentiated actual interactive effects from accidental synchronization due to task-condition similarities, enhancing the study’s accuracy and reliability. For details on the test process and results, see Figure S1 in the supplementary materials. The test involved scrambling real participant dyads and randomly forming new dyads without true interaction to calculate inter-brain synchrony metrics. Conducted 1,000 times to generate a normal distribution, the test compared the mean values of these random dyads with the original dyads for each channel (p < 0.05). This process was applied to all channels.

Data analysis

Behavioral data

To estimate the required sample size for this study, G-Power 3.1 software was used for an a-priori analysis. Given the 2 (sex: female, male) × 2 (group: cooperation, competition) two-way factorial design, F-test-ANOVA is used. Following Cohen’s guidelines, the effect size (d) is set at 0.50, indicating a medium effect size. The statistical power was set at 0.80 (an 80% chance of correctly rejecting a false null hypothesis), and the significance level at 0.05 (a 5% risk of a Type I error). With 1 degree of freedom for the numerator and 4 groups, the total sample size calculated was 34.

Trust was assessed using investment and return rates as behavioral indicators. The investment rate, calculated as (Amount invested / Initial amount) × 100%, reflects the proportion of the initial amount invested. The return rate, calculated as (Amount returned / Triple the investment) × 100%35, indicates the proportion of the tripled investment amount returned to the investor.

Data accuracy and reliability were ensured by removing outliers beyond three standard deviations and replacing them with the dataset mean. After preprocessing, a 2 (sex: female, male)×2(group: cooperation, competition) two-way ANOVA was conducted using SPSS 23.0 to analyze the effects of sex and group on trust behaviors of athletes from different team types, with a significance level set at p < 0.05.

Brain data

After preprocessing the brain data, a 2(sex: female, male)×2(group: cooperation, competition) two-way ANOVA was conducted using SPSS 23.0 to analyze the effects of sex and group on trust behaviors and INS in athletes from different team types, with a significance level of p < 0.05. Additionally, Pearson correlation analysis was used to explore the correlation between behavioral performance and INS.

Results

Descriptive statistical results

To understand participants’ personal circumstances, this study collected data on year of experience, age, athletic level, mood state scores, interpersonal trust scores, competition cores, and cooperation scores for each group, as detailed in Table 1.

To control group differences and ensure data quality, a 2(sex: female, male)×2(group: cooperation, competition) two-way ANOVA was performed on the questionnaire data. The results, summarized in Table 2, revealed a significant main effect of group on interpersonal trust (p < 0.05).

Further post-hoc analysis on the interpersonal trust metric showed no significant group differences for males (p = 0.119) but a marginally significant difference for females (p = 0.057), with female athletes in the cooperative group exhibiting stronger interpersonal trust than those in the competitive group. Additionally, no significant sex differences in interpersonal trust were found within either the competitive group (p = 0.194) or the cooperative group (p = 0.139).

Behavioral results

A 2(sex: female, male)×2(group: cooperation, competition) two-way ANOVA was conducted on investment and return rates. As shown in Table 3, a significant group main effect was found only for investment rates (p = 0.001), while sex and sex-group interaction effects were non-significant (p > 0.05). For return rates, no main or interaction effects reached significance (p > 0.05).

Post-hoc tests for the group main effect on investment rates found (see Fig. 5A) significant differences in both male (t(22) = 8.97, p = 0.007, Cohen’s d = 1.87, 95% CI [0.06, 0.35]) and female groups (t(22) = 9.26, p = 0.006, Cohen’s d = 1.93, 95% CI [0.07, 0.38]). Specifically, the cooperative group had a stronger investment rate than the competitive group, with male cooperative group at 0.86 ± 0.14 versus male competitive group at 0.66 ± 0.19, and female cooperative group at 0.81 ± 0.21 versus female competitive group at 0.59 ± 0.15.

A 2 (sex: female, male)×2 (group: cooperation, competition)×3 (phase: phase one, phase two, phase three) three-way ANOVA was conducted on investment and return rates, with sex, group, and phase (early: rounds 1–4; middle: rounds 5–8; late: rounds 9–12) as factors. As shown in Table 4, significant main effects of phase and group were found only for investment rates (p < 0.05). For return rates, no main or interaction effects were significant (p > 0.05).

Post-hoc tests on investment rates revealed significant differences in the female competitive group (see Fig. 5B): between stages 1 (0.61 ± 0.21) and 2 (0.70 ± 0.23) (p = 0.020, 95% CI [-0.16, -0.02]), and stages 1 and 3 (0.71 ± 0.23) (p = 0.010, 95% CI [-0.17, -0.03]), with later stages showing stronger rates. No difference was found between stages 2 and 3 (p > 0.05). In the male competitive group, a significant difference was observed between stages 1 (0.61 ± 0.22) and 3 (0.74 ± 0.24) (p = 0.022, 95% CI [-0.24, -0.02]), with stage 3 having a stronger rate. These results indicate that investment behavior in the competitive group is influenced by the number of rounds, with investment rates increasing as rounds progress. No such stage effect was found in the cooperative group.

Brain results

In this study, a one-sample t-test (FDR correction) of the INS in all channels of the investment process revealed significant differences in the male competitive group in channel 3 and channel 16 (p < 0.05), and in the female competitive group in channel 7 and channel 11 (p < 0.05). There was no significant difference (p < 0.05) in all channels within the male and female cooperative groups (Supplementary Material Table S2).

To understand the INS during trust decision-making in different categories of male and female athletes, a 2 (sex: female; male) x 2 (group: cooperative; competitive) two-way ANOVA was performed on the channels with significant differences (Supplementary Material Table S3, S4). The results showed a critically significant main effect of group on channel 11 (F(1, 22) = 3.09, p = 0.093, η2 = 0.12), and a critically significant interaction effect of group × sex on channel 11 (F(1, 22) = 3.48, p = 0.075, η2 = 0.14); a significant main effect of sex on channel 16 (F(1, 22) = 5.61, p = 0.027, η2 = 0.21). No significant main or interaction effects were found on the other channels (p > 0.05).

A further simple effects analysis of channel 11 found that the group differences were mainly in the female group (see Fig. 6A, t(22) = 9.43, p = 0.006, Cohen’s d = 1.97, 95% CI [0.05, 0.24]), with female cooperative athletes having significantly stronger INS (0.002 ± 0.11) than female competitive athletes (-0.142 ± 0.13) on channel 11 (left frontal lobe, see Fig. 6B). Further post-hoc testing of channel 16 revealed that sex differences were mainly in the competitive group (see Fig. 6C, t(22) =6.01, p = 0.023, Cohen’s d = 1.25, 95% CI [-0.27, -0.02]), with female competitive athletes having significantly stronger INS (-0.02 ± 0.15) than male competitive athletes (-0.17 ± 0.18) on channel 16 (left dorsolateral prefrontal, see Fig. 6B).

Further, to understand whether the increase in INS during investment increased with rounds, we averaged the 12 rounds of INS into three phases: early (rounds one to four), middle (rounds five to eight), and late (rounds nine to twelve). A significant sex × stage interaction effect was found only on channel 16 (F(1, 22) = 4.37, p = 0.026, η2 = 0.29). No significant main or interaction effects were found on the other channels (p > 0.05). Further simple effects analyses of the interaction effects revealed significant stage differences in the male cooperative group (see Fig. 6D), specifically a significant difference (p = 0.015, 95% CI [0.02, 0.18]) between the second stage (-0.04 ± 0.10) and the third stage (-0.14 ± 0.16), with the second stage INS being significantly stronger than the third stage. Summarizing the results above, it can be found that the INS in the cooperative group during the investment process is affected by the number of rounds. In the mid-term stage, the INS significantly increases, while in the later stage, the INS decreases.

Brain data results. A Comparison of INS indicators in CH11 under different conditions; B incremental F-value plot of INS for CH11 and CH16 (corrected by FDR); C comparison of INS indicators in CH16 under different conditions; D changes in INS of CH16 under different stages. The error line is the standard error. “” Means p < 0.05.

Since the questionnaire revealed varying interpersonal trust levels among athletes from different team types, this study further conducted Pearson correlation analyses between the interpersonal trust levels and athletes’ behavioral (total and per-round investment rates) and neural (overall and per-round INS) indicators. Results (see Appendix Tables S6-S7) showed no significant correlations between these metrics across groups (p > 0.05).

There was a significant correlation between the INS and the interpersonal trust levels across different investment stages. Specifically (see Appendix Tables S8–S11): In stage one, the interpersonal trust levels in the female-competitive group was positively correlated with INS in channel 11 (left frontal lobe, r = 0.551, p = 0.063) and channel 16 (left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, r = 0.644, p = 0.024). In stage two, the interpersonal trust levels in the male-cooperative group was positively correlated with INS in channel 11 (r = 0.643, p = 0.024) and channel 16 (r = 0.630, p = 0.028). In stage three, the interpersonal trust levels in the male-cooperative group was positively correlated with INS in channel 11 (r = 0.665, p = 0.018) and channel 16 (r = 0.608, p = 0.036). As can be seen from this, the higher interpersonal trust level, the stronger INS when athletes make investment decisions.

Discussion

This study combined trust-game tasks and fNIRS hyperscanning to evaluate how team types and sex factors affect athletes’ trust behaviors and related neural mechanisms. It found that cooperative-team athletes had significantly stronger investment rates than competitive-team athletes, with no marked sex differences. In terms of neural activity, cooperative-team athletes showed much stronger INS in the left frontal lobe during investments than competitive type athletes, and this was more evident in females. Also, in competitive-team athletes, females had stronger INS in the left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex during investment decisions than males. These findings offer new insights into how team types and sex influence athletes’ trust behaviors and neural mechanisms.

Research on athlete trust behaviors in sports training contexts is limited. Gao Sanfou (2003) highlighted interdependence among members as key for team trust formation. Zhang Changzheng and Li Huazhu36 viewed trust as built through interpersonal and social interactions. Dou Haibo15 found high team trust in collective ball sports at Chinese universities. These studies show positive team interactions foster trust. This study further explores trust differences between athletes in cooperative-competitive and competitive-cooperative teams. Results indicate cooperative-competitive team athletes show stronger trust behaviors, aligning with previous findings. The stronger trust in cooperative-competitive teams may stem from their greater emphasis on cooperation and interdependence, fostering a trusting atmosphere. In contrast, competitive-cooperative teams focus more on individual comparison and competition, potentially weakening trust. This study offers new insights into sports training’s impact on trust, emphasizing the role of team type and training environment.

This study analyzed investment behavior across three stages and found that in the competitive-cooperative team, investment rates increased with rounds as athletes adjusted trust based on interactions, aligning with the “gradual trust-building model.” In contrast, the cooperative-competitive team showed no stage effect, likely due to the high initial trust from consistent team goals and close cooperation. These findings confirm a link between sports training and trust behavior, offering insights into how different team types and sex factors affect interpersonal trust. The study enriches the understanding of how sports training influences trust and provides valuable references for related research and practices.

Wang et al.7 used trust-game tasks and fNIRS to explore trust behavior differences between athletes and college students. They found athletes have better interpersonal trust, with stronger INS in the left frontal lobe and left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex. Male athletes also showed stronger trust behaviors and left dorsolateral prefrontal INS than females. This study offers new approaches to understanding the sports-trust relationship. In our study, using the same methods, we found in the female cooperative group, left frontal lobe INS during investment decisions was stronger than in the female competitive group. And in the female competitive group, left dorsolateral prefrontal INS was stronger than in the male competitive group. These results indicate that INS varies in athletes of different team types and sexs during interpersonal trust processes. Our findings align with previous results, highlighting the key role of the left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex in sex differences of trust behaviors in the competitive group. Notably, we found the left frontal lobe is crucial for sex differences in the female athletic group. The left frontal lobe is essential for positive emotion regulation37,38, cognitive control39, and socio-emotional behavior40. Its enhanced INS may indicate more active emotional and cognitive interactions in cooperative-group athletes during trust processes. The left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex plays a key role in decision-making, cognitive and emotional regulation41,42. The stronger INS in this region in females in the competitive group might be related to their strategy adjustment and decision-making process in trust-game experiments. This finding was consistent with previous research results. Croson43 reported females are more risk-averse and cooperative in economic behaviors. Buchan44 observed stronger trust in females than males in trust-game experiments. Niederle45 found females tend to avoid competitive settings more than males. Our results confirm the sex difference in trust behaviors, with females showing stronger trust and lower competitiveness. Additionally, significant correlations were found between trust questionnaire metrics and INS. As interpersonal trust increases, so does INS during investment decisions. This confirms INS as a key neural metric for interpersonal trust. It is a reliable indicator of social interaction quality, linked to information transmission32, joint attention19, intention sharing46, and social decision-making47. In summary, our study provides new evidence for the neural mechanisms underlying trust behaviors in athletes of different team types and sexs. It enriches our understanding of how sports training impacts interpersonal trust and offers a foundation for future research.

This study offers new insights into the relationship between sports training and interpersonal trust, yet its design has certain limitations. Firstly, the study assigned fixed roles to participants in the behavioral experiment, which may have restricted a comprehensive understanding of trust situations. To explore the dynamic changes in trust behavior more thoroughly, future research could allow participants to switch between the roles of “investor” and “trustee” in different rounds. Secondly, the cross-sectional design of this study can only reveal the correlation between sports training and interpersonal trust, not causality. Therefore, future research could employ a randomized controlled trial with sports intervention to investigate the impact of sports training on trust behavior. This would provide more rigorous empirical support for the relationship between sports and interpersonal trust.

Conclusion

This study used trust-game tasks and fNIRS hyperscanning to explore how team types and sex factors affect athletes’ trust behaviors and INS. It found that cooperative-competitive athletes showed better trust behaviors than competitive-cooperative ones, which may be linked to enhanced INS in the left frontal lobe. Also, in competitive-cooperative athletes, females had stronger INS during trust decisions than males, mainly in the left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex. The study indicates that team type and sex significantly affect athletes’ interpersonal trust behaviors, accompanied by changes in INS in specific brain regions.

Data availability

All datasets generated for this study are included in the manuscript and/or the supplementary file.

References

Mayer, R. C., Davis, J. H. & Schoon, F. D. An integrative model of organizational trust. Acad. Manage. Rev. 20 (3), 709–734 (1995).

Berg, J., Dickhaut, J. & McCabe, K. Trust, reciprocity, and social-history. Games Econ. Behav. 10 (1), 122–142 (1995).

Bond, S. Attachment in adulthood: structure, dynamics, and Change. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 197 (2), 144–145 (2009).

Kuo, F. & Yu, C. An exploratory study of trust dynamics in work-oriented virtual teams. J. Comput. Med. Commun. 14 (4), 823–854 (2009).

Xie, C. A Study on the Influence of Team Interaction of Adolescent Football Players on Team effectiveness (Liaoning Normal University, 2018).

Jones, K. Trust in sport. J. Philos. Sport. 28 (1), 96–102 (2001).

Wang, H. et al. A study of trust behavior and its neural basis in athletes under long-term exercise training. Neurosci. Lett. 805, 137127 (2023).

Chen, Z., Qin, X. & Vogel, D. Is Cooperation a panacea? The effect of cooperative response to task conflict on team performance. Syst. Res. Behav. Sci. 29 (2), 163–178 (2012).

Dong, C. et al. Competition and cooperation: a study on sports team conflict in China. J. Shenyang Univ. Phys. Educ. 34 (04), 1–6 (2015).

Zhou, Y. et al. The development of shared mental models in 3-person football teams and their relationship with team performance. J. Sports Sci. 24(10), 49–53 (2006).

Timmerman, T. A. Racial diversity, age diversity, interdependence, and team performance. Small Group. Res. 31 (5), 592–606 (2000).

Huang, S. A study on cultivating modern team cohesion in volleyball. J. Guangzhou Univ. Phys. Educ. 30 (03), 118–120 (2010).

Fei, Z. A study on team trust and cohesion in China’s top volleyball teams (Shenyang University of Physical Education, 2013).

Zhang, K. Construction and Evaluation of Team Cohesion in high-level College Basketball Teams (Shandong University of Science and Technology, 2011).

Dou, H. A Study on Team Efficacy in high-level Collective Ball Sports in Chinese universities (Beijing Sport University, 2014).

Ohdaira, M. et al. F NIRS-based analysis of brain activation with knee extension induced by functional electrical stimulation. World congress on medical physics and biomedical engineering, Vols 1 and 2, 2015, 51: 1137–1141 (2015).

Tang, H. et al. Interpersonal brain synchronization in the right temporo-parietal junction during face-to-face economic exchange. Soc. Cognit. Affect. Neurosci. 11 (1), 23–32 (2016).

Montague, P. R. et al. Hyperscanning: simultaneous fMRI during linked social interactions. Neuroimage 16 (4), 1159–1164 (2002).

Hasson, U. et al. Brain-to-brain coupling: a mechanism for creating and sharing a social world. Trends Cogn. Sci. 16 (2), 114–121 (2012).

Pan, Y. et al. Cooperation in lovers: an fNIRS-based hyperscanning study. Hum. Brain. Mapp. 38 (2), 831–841 (2017).

Xue, H., Lu, K. & Hao, N. Cooperation makes two less-creative individuals turn into a highly-creative pair. Neuroimage 172, 527–537 (2018).

Li, Y. A Study on the Neural Mechanisms of Cooperation and competition (Southwest University, 2018).

Rizzolatti, G. & Craighero, L. The mirror-neuron system. Annual Rev. Neurosci. 27, 169–192 (2004).

Wu, S. et al. The only-child effect in the neural and behavioral signatures of trust revealed by fNIRS hyperscanning. Brain Cogn. 149, 104658 (2021).

Cheng, X. et al. Integration of social status and trust through interpersonal brain synchronization. Neuroimage 246, 118725 (2022).

Svrakic, D. M., Przybeck, T. R. & Cloninger, C. R. Mood states and personality-traits. J. Affect. Disord. 24 (4), 217–226 (1992).

Zhu, B. An introduction to the POMS scale and its short-form Chinese norms. J. Tianjin Univ. Sport 10(01), 35–37 (1995).

Rotter, J. B. A new scale for the measurement of interpersonal trust. J. Pers. 35 (4), 651–665 (1967).

Xie, X. et al. Measurement of personality tendencies in Cooperation and competition. Acta Physiol. Sin. 38(01), 116–125 (2006).

Zhang, X., Noah, J. A. & Hirsch, J. Separation of the global and local components in functional near-infrared spectroscopy signals using principal component Spatial filtering. Neurophotonics 3(1), 015004 (2016).

Grinsted, A., Moore, J. C. & Jevrejeva, S. Application of the cross wavelet transform and wavelet coherence to geophysical time series. Nonlinear Process. Geophys. 11 (5–6), 561–566 (2004).

Cui, X., Bryant, D. M. & Reiss, A. L. NIRS-based hyperscanning reveals increased interpersonal coherence in superior frontal cortex during cooperation. Neuroimage 59 (3), 2430–2437 (2012).

Nozawa, T. et al. Interpersonal frontopolar neural synchronization in group communication: an exploration toward fNIRS hyperscanning of natural interactions. Neuroimage 133, 484–497 (2016).

Achard, S. et al. A resilient, low-frequency, small-world human brain functional network with highly connected association cortical hubs. J. Neurosci. 26 (1), 63–72 (2006).

Burks, S. V., Carpenter, J. P. & Verhoogen, E. Playing both roles in the trust game. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 51 (2), 195–216 (2003).

Zhang, C. & Li, H. A study on the dynamic evolution model of team trust forms. Sci. Technol. Prog. Policy 23(11), 179–182 (2006).

Davidson, R. J. What does the prefrontal cortex do in affect: perspectives on frontal EEG asymmetry research. Biol. Psychol. 67 (1–2), 219–233 (2004).

Ochsner, K. N. & Gross, J. J. The cognitive control of emotion. Trends Cogn. Sci. 9 (5), 242–249 (2005).

Miller, E. K. & Cohen, J. D. An integrative theory of prefrontal cortex function. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 24, 167–202 (2001).

Volman, I. et al. Endogenous testosterone modulates Prefrontal-Amygdala connectivity during social emotional Behavior. Cereb. Cortex. 21 (10), 2282–2290 (2011).

Nejati, V., Salehinejad, M. A. & Nitsche, M. A. Interaction of the left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (l-DLPFC) and right orbitofrontal cortex (OFC) in hot and cold executive functions: evidence from transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS). Neuroscience 369, 109–123 (2018).

Buhle, J. T. et al. Cognitive reappraisal of emotion: a meta-analysis of human neuroimaging studies. Cereb. Cortex. 24 (11), 2981–2990 (2014).

Croson, R. & Gneezy, U. Gender differences in preferences. J. Econ. Lit. 47 (2), 448–474 (2009).

Buchan, N. R., Croson, R. T. A. & Solnick, S. Trust and gender: an examination of behavior and beliefs in the investment game. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 68 (3–4), 466–476 (2008).

Niederle, M. & Vesterlund, L. Do women shy away from competition? Do men compete too much? Quart. J. Econ. 122 (3), 1067–1101 (2007).

Fishburn, F. A. et al. Putting our heads together: interpersonal neural synchronization as a biological mechanism for shared intentionality. Soc. Cognit. Affect. Neurosci. 13 (8), 841–849 (2018).

Yang, J. et al. Within-group synchronization in the prefrontal cortex associates with intergroup conflict. Nat. Neurosci. 23 (6), 754 (2020).

Funding

The study was funded by the Innovative Experiment Development in Open Laboratories or Internship Bases, East China Normal University, China.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

HuilingWang: investigation, datacuration, writing, review and editing, conceptualization, methodology, software, validation, formal analysis, investigation, data curation . Yisong Cong: formal analysis, data curation.Changjiang Liu: resources, writing—review and editing, funding acquisition.Lin Li: Conceptualization; validation, formal analysis, resources, writing—review and editing, visualization, supervision.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, H., Cong, Y., Liu, C. et al. An fNIRS hyperscanning study on the influence of team type and sex on athletes’ interpersonal trust and neural mechanisms. Sci Rep 15, 28456 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-12565-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-12565-8