Abstract

Subaqueous fan reservoirs have emerged as a pivotal focus in recent deep-water oil and gas exploration. In the Illizi Basin of Algeria, a series of submarine fan reservoirs are developed within the Devonian F4 Formation of the Z oilfield. Understanding the genesis of high-quality reservoirs (defined as those with porosity exceeding 25% and permeability greater than 1000 mD) is crucial for pinpointing high-productivity wells in deep-water submarine fan settings.

By integrating core data, thin-section analysis, grain-size data, logging data, and petrophysical property data, this study systematically classifies the depositional environments in the study area, constructs a sedimentary-logging identification template, maps the spatial distribution of lithofacies associations, identifies diagenetic types and evolution sequences, assesses reservoir quality, uncovers the origin of high-quality reservoirs and formulates a genetic model for high-quality reservoirs.

The findings show that the study area encompasses 12 rock lithofacies types and 6 lithofacies associations, with braided river channels and interchannel facies being the predominant facies. Four diagenetic processes—compaction, cementation, dissolution, and fracturing—have been identified. Compaction and cementation tend to decrease porosity and permeability, while dissolution and fracturing enhance these properties. Four diagenetic evolution sequences, namely calcite cementation, dolomite cementation, muddy cementation, and quartz cementation, are recognized. Reservoirs associated with calcite and dolomite cementation sequences generally exhibit superior properties due to more strongly developed dissolution, whereas those related to muddy and quartz cementation sequences are of poor quality. Notably, high-quality reservoirs such as LF2, LF7, and LF9 developed in braided river channel microfacies have undergone calcite cementation. These findings verify the critical interplay between depositional facies and diagenetic processes in determining reservoir quality, providing valuable insights for future exploration and production strategies in similar geological settings.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Subaqueous fans are fan bodies formed by subaqueous gravity flows1,2. Based on the differences in the sedimentary environment, subaqueous fan deposits can be classified into steep bank deposits on the shore of rift lake basins and shelf edge deposits on the continent. Many studies have been carried out on subaqueous fans onshore of the steep banks of rift lake basins in China3,4,5,6. Moreover, considerable research has been conducted on subaqueous fans on continental shelves. With the discovery of many subaqueous fan reservoirs in the offshore areas of Angola, the Niger Delta Basin7, Gulf of Mexico, and South China Sea8 by international oil companies, research on subaqueous fans at the edges of continental shelves is becoming increasingly valuable. To date, research on subaqueous fans located on continental shelf edges has focused on the distributions of sedimentary facies, the architecture of facies and the joint effects of supercritical turbidity currents and bedforms9,10,11. However, research on the origin of high-quality marine subaqueous fan reservoirs deposited on marine shelf edges has become focus in recent years. Subaqueous fan reservoirs are major petroleum reservoirs in many sedimentary basins worldwide12. Pringle et al.13 used ground-penetrating radar and other equipment to elucidate the channel architecture, connectivity and curvature of subaqueous fan reservoir outcrops in Alport Castles, England. Umar et al.14 reported the influence of diagenesis on the quality of subaqueous fan reservoirs in the Late Cretaceous Fab Formation in southern Pakistan. Marchand et al.15 revealed the influences of different sedimentary facies on reservoir quality and noted that reservoirs with channel facies are of higher quality than those with lobe facies. Zhang et al.16 used a subaqueous fan reservoir in the Niger Delta Basin as an example and displayed reservoir heterogeneity by using logging data and four-dimensional seismic data. Wang et al.17 proposed that the mechanisms underlying quality variations in submarine-fan reservoirs includes depositional fabric, lithofacies differences, and characteristics of genetic units. Bello et al.18 believed that reservoir quality is predominantly controlled by primary depositional factors. Braided fluvial fan sandstones form reservoirs with the best quality because of medium to coarse grain size and low volume of clay matrix, and nearshore sandstones form reservoirs with the lowest quality owing to their finer grain size and high clay matrix content. Diagenesis, such as low clay matrix content, mechanical compaction, and cementation, is the main factor affecting reservoir quality. Butt et al.12 indicated that sedimentological transport processes control depositional reservoir quality, which in turn determines diagenetic modification in deep-marine sandstones. Sandstones of graded bedded and channelized sandstone lithofacies deposited in the medial fan facies association form excellent quality reservoirs. Bakr et al.19 held that these variations in reservoir quality are largely controlled by sedimentation and diagenetic processes. Compaction and cementation reduced porosity and permeability by restricting the pore network, other diagenetic processes such as dissolution, fracturing, and dolomitization can enhance porosity and permeability. Zhang et al.20 considered that high-quality reservoirs in the Qiongdongnan Basin are mainly related to deposition, which is mainly controlled by factors such as high fluvial input, low sea levels, and the paleoenvironment. Diagenesis is weak and has little impact on reservoir quality. Reservoir quality is affected by both sedimentation and diagenesis, thus, it is necessary to explain the origins of the high-quality reservoirs of subaqueous fans deposited on the edge of a continental shelf through a comprehensive study of sedimentation and diagenesis.

The Z oilfield in the Illizi Basin, Algeria, was discovered in 1957 and put into production in 1960. The target zone is the F4 Formation from the Early Devonian Emsian. This zone is a layered reservoir with a gas cap and marginal water. After decades of development, the oilfield has entered the late stages of development. Li et al.21,22 presented a detailed study of sedimentary microfacies and built a geological model of a subaqueous fan reservoir. Zheng et al.23 investigated the sequence stratigraphy and direction of the F4 Formation provenance, Chen et al.24 analyzed the petrological characteristics of the F4 Formation, and Sun et al.25 described the distribution characteristics of the remaining oil of the Z oilfield. Previous studies focused mainly on the sedimentary features and distributions of sedimentary facies, but significant differences remain in reservoirs within the same sedimentary facies zone in the study area, which poses considerable challenges for adjusting development plans. Thus, it is necessary to conduct a systematic analysis of the origin of high-quality reservoirs in the study area.

In this work, the F4 Formation of the Z oilfield in the Illizi Basin, Algeria, is taken as a case. On the basis of core, thin-section, logging, core porosity and permeability data, the lithofacies of subaqueous fan reservoirs in the study area are analyzed, the diagenetic types and diagenetic evolution sequence in the study area are defined, the origin of high-quality reservoirs in the study area is revealed, and a sedimentary‒diagenetic evolution model in the study area is established.

Geological background

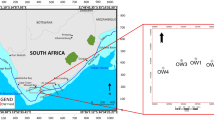

The Illizi Basin is located in the eastern part of Algeria. This basin is bounded by the Tihemboka Arch to the east, the outcrop at the edge of the Precambrian Hoggar massif to the south, the Amguid–Hassi Touareg structural axis to the west, and the Ghadames Basin to the north26 (Fig. 1a). The basement of the Illizi Basin is composed of Precambrian metamorphic rocks, which are covered by Paleozoic and Mesozoic strata. During most of the Paleozoic, the Illizi Basin and adjacent areas belonged to the continental shelf of the northern African craton (Zhang27). The seawater in the basin gradually deepened northward; the sea level of the ocean gradually rose in the early Paleozoic, whereas it gradually declined in the late Paleozoic (Ji et al.28). The sedimentary characteristics of the Paleozoic strata were inherited in the Mesozoic, and many sets of salt rocks developed due to the influence of the arid climate. The Illizi Basin experienced four main stages of tectonic evolution, including the Caledonian orogeny, the Hercynian orogeny, the Tethys rifting and the Tethys sag phase29,30.

Geographical location and structural characteristics of the study area: (a) location of the Illizi Basin and (b) top structural map of the F4 Formation of the Z oilfield (Created by CorelDRAW Graphics Suite 2020, https://www.coreldraw.com/cn/).

The Z Oilfield is located in the eastern part of the Illizi Basin. The top structure of the F4 Formation is an NNW–SNE-trending fault anticline with a length of 14 km, a width of 7 km and an area of 100 km2. Owing to the influences of multistage tectonic movements, various faults have developed in the study area. The anticline is bordered by faults to the southeast and southwest, with two nearly north‒south trending faults and three small faults in the anticline (Fig. 1b). The main pay zones of this oilfield comprise Devonian and Carboniferous strata. The Devonian strata are divided into upper–middle Devonian and lower Devonian strata, with the F2 Formation in the upper–middle Devonian and the F4 and F6 Formations in the lower Devonian. The top of the F4 Formation experienced strata erosion, and it was in unconformable contact with the F2 Formation of the Middle–Upper Devonian. The targeted F4 Formation in this study belongs to the stratum of the Devonian Emsian stage (Fig. 2), which is the most important oil- and gas-producing layer in this oilfield. During the early Devonian Emsian stage, when the F4 Formation developed, the Avalon terrane collided with the Lauya Polo plate, resulting in Hercynian tectonic movement. A passive continental margin basin formed in the northern part of North Africa, with an increase in sedimentary thickness31. The Paleo-Tethys Ocean expanded, sea levels decreased, and sediment was deposited toward the sea. With decreasing sea level, the F4 Formation developed subaqueous fan deposits in a marine environment32. The F4 Formation formed the anticline and the southwest and the southeast is bounded by faults. The source rock was from Devonian Emsian shale, the buried depth of which is 1280 m-1370 m. The seal rock is the mudstone layer of F3 Formation, The reservoir petrophysical properties are good, with an average porosity of 17.3% and an average permeability of 207.1 MD. The F4 Formation is divided into five layers, namely, I, II, III, IV and V, from bottom to top. The gross thickness of the F4 Formation ranges from 30.1 m to 92.3 m, with an average thickness of 46.37 m and an average net reservoir of 26.26 m.

Stratigraphic column of the Illizi Basin (adapted from30).

Materials and methods

Sedimentary facies identification and classification

Sedimentary facies reflect the interplay of lithofacies, biofacies, and sedimentary environments33. To delineate depositional systems in the study area, we integrated core description, logging curve analysis, and grain size distribution (Fig. 1B).

Core Analysis: 192.37 m of core from seven wells were described for lithology, color, bedding structures, and fossil content. Well Z1 provided the most comprehensive dataset due to its continuous core coverage of the F4 Formation.

Logging Curve Interpretation: Gamma-ray (GR) profiles from 7 wells were systematically correlated with core facies to establish a microfacies classification scheme. For 321 wells, key GR signatures, including bell-shaped and funnel-shaped patterns, were definitively linked to specific sedimentary facies types, such as braided channels and braided channel lateral border facies. After identifying the single-well sedimentary microfacies, their spatial distributions in the study area were mapped using the microfacies interpretation results at well locations.

Grain Size Analysis: Twenty-three samples from Wells Z1 and Z4 were analyzed following Chinese petroleum standard SY/T6312-1997. Results were used to reconstruct original depositional porosity and infer transport mechanisms.

Diagenetic analysis

To quantify diagenetic impacts on reservoir quality, we employed petrographic microscopy, scanning electron microscopy (SEM), and thin-section analysis:

Thin-Section Petrography: Sixty-four blue epoxy-impregnated thin sections from Wells Z1 and Z4 were examined under a Nikon Eclipse E600WPL microscope to characterize pore types, cementation, and compaction features.

Field emission scanning electron microscopy (FE–SEM) Analysis: Clay mineralogy and microtextures were analyzed using a Carl Zeiss Supra 55 FE–SEM at 5 kV with 30-μm grating and 40-s counting time. The types of clay minerals were identified.

Diagenetic Modeling: Using data from Well Z4, we reconstructed the diagenetic sequence and quantified porosity loss/gain, linking each diagenetic phase to porosity evolution.

Petrophysical property measurement

Porosity and permeability of 335 cylindrical samples (4 cm length × 2.5 cm diameter) parallel to the stratigraphic horizontal direction from seven wells were measured using helium porosimetry. The classification criteria for sandstone reservoirs in the Chinese petroleum industry (SY/T6285-1997) were applied to classify reservoir quality.

Results

Analysis of sedimentary features

Lithofacies description and interpretation

Lithofacies are rocks or rock associations that formed in a certain sedimentary environment; that is, specific rock products form in specific sedimentary facies (Table 1). Twelve lithofacies have been identified in the study area, including grayish-black mudstone facies (LF1) (Figs. 3a and 4a), mudstone conglomerate facies with massive bedding (LF2) (Fig. 3b and 4b), sand–mudstone interbedded facies (LF3) (Fig. 3c and 4c), siltstone facies with parallel bedding (LF4) (Fig. 3d and 4d), siltstone facies with wavy bedding (LF5) (Fig. 3e and 4d), siltstone facies with cross bedding (LF6) (Fig. 3f and 4d), massive siltstone facies (LF7) (Fig. 3g and 4e), fine sandstone facies with wavy bedding (LF8) (Fig. 3h and 4f), massive fine sandstone facies (LF9) (Fig. 3i and 4g), medium sandstone facies with massive bedding (LF10) (Fig. 3j and 4h), massive coarse sandstone facies (LF11) (Fig. 3k and 4i) and grain-size gradation coarse sandstone facies (LF12) (Fig. 3l and 4j). The lithofacies of well Z5 is shown in Fig. 5.

Lithofacies identification results of the F4 Formation in the Z oilfield: (a) gray‒black mudstone facies, well Z5, at a depth of 1435.25–1435.3 m; (b) mudstone conglomerate facies with massive bedding, well Z3, at a depth of 1371.45–1371.55 m; (c) sand–mudstone interbedded facies, well Z1, at a depth of 1353.33–1353.41 m; (d) siltstone facies with parallel bedding, well Z5, at a depth of 1353.87–1353.96 m; (e) siltstone facie with wavy bedding, well Z1, at a depth of 1355.33–1355.41 m; (f) siltstone facies with cross bedding, well Z5, at a depth of 1429.21–1429.29 m; (g) massive siltstone facies, well Z1, at a depth of 1352.1–1352.21 m; (h) fine sandstone facies with wavy bedding, well Z7, at a depth of 1456.27–1456.1 m; (i) massive fine sandstone facies, well Z2, at a depth of 1354.25–1354.4 m; (j) massive medium sandstone facies, well Z6, at a depth of 1462.35–1462.43 m; (k) massive coarse sandstone facies, well Z8, at a depth of 1366.33–1366.38 m; and (l) grain-size gradation coarse sandstone facies, well Z3, at a depth of 1341.15–1341.2 m.

Lithofacies associations and sedimentary microfacies

The 12 lithofacies in the study area can be divided into 6 lithofacies associations, namely, the LF2-LF7-LF1(LA1), L11-L12-L10 -LF6-LF7(LA2), LF2-LF9-LF8-LF5-LF3(LA3), LF7-LF3(LA4), LF7-LF4-LF7(LA5) and LF1-LF7-LF1(LA6) lithofacies associations. Different lithofacies associations indicate different sedimentary environments, and the corresponding sedimentary microfacies can be identified according to the characteristics of the lithofacies associations.

-

(1)

LA1 lithofacies association

This association develops LF2, LF7 and LF1 from bottom to top (Fig. 6A). LF2 is a purplish-red color and relatively thin, ranging from ten centimeters to dozens of centimeters. Purplish-red mud and gravel originate from the erosion of exposed continental shelf mudstone by water flow or the collapse of continental shelf mud. The associations are mainly developed near the bottom of the slope and are caused by debris flows or collapses. Therefore, it can be concluded that this lithofacies association is the product of slump debris flow facies.

Fig. 6 Lithofacies association of the F4 Formation in the Z oilfield: (A) lithofacies association of LF2–LF7–LF1; (B) lithofacies association of L11–L12–L10–LF2–LF6–LF7; (C) lithofacies association of LF2–LF9–LF8–LF5–LF3; (D) lithofacies association of LF7–LF3; (E) lithofacies association of LF7–LF4–LF7; and (F) lithofacies association of LF1–LF7–LF1

-

(2)

LA2 lithofacies association

This lithofacies features L11, L12, L10, LF6 and LF7 from bottom to top (Fig. 6B). The lithofacies association is a common type of F4 Formation, and its thickness varies greatly—generally, by several meters. The top and bottom of the association are in sharp contact with gray‒black mudstone or thin interbedded sand–mudstone facies. This lithofacies association indicates high-concentration debris flows or high-density particle flows, which have a certain scouring effect on the lower strata. This lithofacies association formed in the braided channel facies.

-

(3)

LA3 lithofacies association

This lithofacies association includes LF2, LF9, LF8, LF5, and LF3 from bottom to top (Fig. 6C). The change in lithofacies from bottom to top reflects a decrease in gravity flow energy and density, reflecting the transition from a high-density turbid flow to a low-density or traction current. Thus, it can be concluded that this lithofacies association indicates braided channel lateral border facies.

-

(4)

LA4 lithofacies association

The bottom of the lithofacies association is LF7, and it gradually changes to LF3 (Fig. 6D). This process mainly involves turbidity current deposition or marine flooding between channels. The lithofacies association formed in the intrachannel facies with relatively weak hydrodynamic forces.

-

(5)

LA5 lithofacies association

This lithofacies association is mainly composed of LF7, which is occasionally interbedded with LF4 (Fig. 6E). LF7 is relatively thick, reaching 1 ~ 3 m, whereas LF4 is relatively thin, ranging from several centimeters to more than ten centimeters in thickness. This lithofacies association is present in the braided channel front facies.

-

(6)

LA6 lithofacies association

This lithofacies association is mainly composed of LF1, which is sometimes interbedded with LF7 (Fig. 6F). LF1 is approximately several meters in thickness and is the product of deep-sea deposition. Occasionally, turbidity currents affect the formation of thin layer LF7. This lithofacies association is deposited in the sheet sand facies.

Distribution characteristics of sedimentary microfacies

According to the logging curve identification features for different sedimentary microfacies, logging curve identification charts are established (Fig. 7). The slump debris flow microfacies logging curves are box shaped and have many serrations. The braided channel microfacies logging curve is typically box shaped, the braided channel lateral border microfacies logging curve is bell shaped, the braided intrachannel microfacies logging curve is low-amplitude-finger shaped, the braided channel front microfacies logging curve is funnel shaped, and the sheet sand microfacies logging curve is finger shaped. The deep-sea mudstone logging curve is straight with a low GR value. The spontaneous potential (SP) is similar to that of the GR curve.

Braided channel microfacies and braided channel lateral border microfacies are the main microfacies in the study area, with high sand contents and good planar reservoir connectivity (Figs. 8 and 9).

Distributions of sedimentary facies in different layers of the F4 Formation in the Z oilfield; planar distribution of sedimentary microfacies in (a) layer I in the F4 Formation of the Z oilfield; (b) layer II in the F4 Formation of the Z oilfield; (c) layer III in the F4 Formation of the Z oilfield; (d) layer IV in the F4 Formation of the Z oilfield; and (e) layer V in the F4 Formation of the Z oilfield.

Analysis of diagenesis

Previous studies have proposed a calculation method for determining the influences of different types of diagenesis on the original pore spaces of sandstone reservoirs36,37,38, and the relevant formulas are as follows:

where \(\Phi\) is the original porosity, \({\text{S}}_{0}\) is the Trask sorting coefficient, and P25 and P75 are the particle sizes of 25% and 75%, respectively, on the probability accumulation curve, \(\Phi_{1}\) is the residual porosity, a is the compaction factor (equal to 0.00040), h is the sample burial depth (equal to 1000 m), \(\Phi_{2}\) is the porosity reduced by cementation, \({\text{M}}_{\text{c}}\) is the dissolution porosity of cementation in the thin section, M is the total porosity of the thin section, σ is the cementation content, \(\Phi_{3}\) is the increased porosity due to dissolution, and \({\text{M}}_{\text{d}}\) is the dissolution porosity of the thin section.

Many previous studies on porosity have shown that the porosity of original sediments is related mainly to rock grain size. Notably, the porosity of original sediments is the basis for studying porosity evolution. Therefore, we perform a quantitative analysis of the porosity evolution of samples with different rock grain sizes. The grain size analysis of 23 samples, including siltstone, medium sandstone and fine sandstone samples, is performed in the study area, providing a reliable basis for the subsequent quantitative analysis of porosity.

Compaction

Compaction is a process in which sediments discharge pore water under the influences of overlying formation pressure and hydrostatic pressure, arranging clastic grains tightly together. Compaction is an important diagenetic type in the F4 Formation of the Z oilfield. The compaction intensity is exponentially related to the burial depth. Compaction occurs in all lithofacies and is a common geological phenomenon. Here, the main burial depth of the target layer is approximately 1000 m, and the study area is supported mainly by particles, with point contact, line contact, and occasional concave–convex contact between particles. Grain cracks can be observed in the thin sections (Fig. 10A and B). Moreover, compaction reduces the original pore space in the study area.

Diagenesis of the F4 Formation in the Z oilfield of the Illizi Basin: (a) Well Z4, at a depth of 1407.98 m, with point contact or line contact between particles, LF4; (b) Well Z4, at a depth of 1403.96 m, with concave–convex contact between grains and grain cracks, LF7; (c) Well Z4, at a depth of 1400.43 m, with particles cemented by clay, LF7; (d) Well Z4, at a depth of 1409.34 m, with particles cemented by clay, LF12; (e) Well Z4, at a depth of 1407.36 m, with point contact or line contact between particles, LF2; (f) Well Z4, at a depth of 1409.78 m, filled with page-like kaolinite between grains, LF11; (g) Well Z4, at a depth of 1434.70 m, with dolomite cementation among grains, LF6; (h) Well Z4, at a depth of 1442.05 m, with siderite cementation among grains, LF3; (i) Well Z4, at a depth of 1400.07 m, with quartz secondary outgrowth among grains, LF6; (j) Well Z4, at a depth of 1432.90 m, with primary intergranular pores developed among the grains, LF10; (k) Well Z4, at a depth of 1410.26 m, with secondary intergranular dissolved pores developed between particles, LF9; and (l) Well Z4, at a depth of 1436.10 m, with the structural fractures developed, LF8.

On the basis of formulas (1 ~ 5), the original porosities of the siltstone, medium sandstone and fine sandstone are 0.3054, 0.3550 and 0.3826, respectively, and the porosities of these three kinds of sandstone reduced by compaction are 0.1007, 0.1170 and 0.1262, respectively (Table 2). Siltstone is dominant in the study area, followed by fine sandstone; thus, the porosity reduced by compaction in the study area is between 0.1007 and 0.1170.

Cementation

Cementation is another important diagenetic process in the study area. The primary pores between particles in the study area are filled with cement, greatly reducing the original pore space between particles. Many stages of cementation, including clay cementation, carbonate cementation and quartz cementation, have been observed in the study area. The porosities of the siltstone, medium sandstone and fine sandstone in the study area reduced by cementation are 0.0936, 0.1007 and 0.1047, respectively (Table 2).Clay cementation is the main cementation type in the study area that occurs mainly in the form of kaolinite, which fills the space between grains in a page-like manner (Fig. 10C, D and E). The carbonate cement types in the study area are mainly calcite and dolomite, which were formed by seawater precipitation in a marine sedimentary environment. Two stages of calcite cementation can be observed in the study area. In the first stage, calcite cementation is fibrous and covers the surfaces of particles in a thin film, which is the product of the seawater hyporheic zone39 (Fig. 10F). In the second stage, calcite cementation results in syntaxial overgrowth, which is the product of the freshwater hyporheic zone in the early stage of diagenesis39 (Fig. 10F). The dolomite in the study area is mainly fine crystalline dolomite, and the dolomite has a xenomorphic texture. The dolomite fills in the intergranular pores, which leads to a significant decrease in the primary porosity, and dissolved pores can be seen in the dolomite cement (Fig. 10G). The siderite in the study area has developed into micropowder crystals, which are evenly distributed in the clay strip, reducing the porosity and permeability of the reservoir in the study area to some extent (Fig. 10H). The secondary outgrowth of quartz is less developed in the study area, and it fills the pore throat, which has little effect on the reservoir porosity but reduces the reservoir permeability in the study area (Fig. 10I).

Dissolution

The dissolution pores in the study area are mainly developed in calcite or dolomite cementation, which illustrates that burial dissolution developed and occurred later than cementation (Fig. 10K). The degree of dissolution is relatively low, and the area ratio of dissolved pores is only approximately 3 ~ 4%, which somewhat improves the reservoir porosity.

Fracturing

Fracturing is not well developed in the study area. High-angle structural fractures that formed under the influence of tectonic movement are occasionally observed in cores and thin sections (Fig. 10L). Although there are few fractures, those can greatly improve reservoir permeability. Because the structural fractures in the study area are relatively undeveloped, the overall improvement in reservoir permeability caused by fracturing is relatively limited.

Diagenesis processes

The diagenetic processes in the study area can be divided into four sequence types: clay cementation, calcite cementation, dolomite cementation and quartz cementation (Fig. 11). The calcite and dolomite cementation sequences are collectively called carbonate cementation sequences. The clay cementation sequence mainly proceeds through the following diagenetic evolution stages: the sediments undergo compaction after the original sediment deposition, forming point contacts, line contacts and concave–convex contacts; clay cementation and siderite cementation develop in the early diagenetic stage; and dissolution and fracturing occur in the late diagenetic stage. Because clay sediments are slow to dissolve, almost no dissolution can be observed (Fig. 11A). The calcite cementation sequence mainly experiences the following diagenetic evolution stages: the first period of calcite development occurs in the syngenetic diagenesis stage after the original sediments are deposited; the sediments experience compaction, forming point contacts, line contacts and concave–convex contacts; and the second period of calcite cementation develops in the early diagenesis stage, followed by fracturing and dissolution in the late diagenesis stage. There is obvious dissolution in the fractures in the study area, indicating that dissolution occurs later than fracturing (Fig. 11B). The dolomite cementation sequence mainly undergoes the following diagenetic evolution stages: the sediments undergo compaction after the original sediment deposition, forming points, lines and concave–convex contacts, and dolomite cementation develops in the early diagenetic stage, followed by fracturing and dissolution in the late diagenetic stage (Fig. 11C). The quartz cementation sequence mainly experiences the following diagenetic evolution stages: after the original sediment deposition, the sediments experience compaction, forming points, lines and concave–convex contacts; quartz cementation and siderite cementation develop in order in the early diagenetic stage, whereas fracturing develops in the late diagenetic stage (Fig. 11D).

The main factor affecting the diagenetic differentiation of rocks is the influence of sedimentation. The influence of sedimentation on the diagenetic evolution sequence includes the rock composition and rock texture. The impact of the rock composition on the diagenetic evolution sequence is mainly from the clay content, and the influence of the rock texture on the diagenetic evolution sequence is mainly from the rock grain size. With a high clay content and small original sediment grain size, clay cement develops more easily; otherwise, carbonate cement develops more easily40. The study area is dominated by clay cementation and carbonate cementation, whereas quartz cementation develops only in the local zone. On the basis of the clay content interpreted from logging data, the clay contents of different lithofacies in the study area are defined. Combined with the identification results of cementation type from thin sections, the lithofacies with clay contents greater than 15% in the study area develop clay cementation (Fig. 12). The clay contents of LF1, LF3, LF5, LF8 and LF12 are greater than 15%, and the sediment grain sizes are fine and dominated by clay cementation (Table 2). Carbonate cementation has developed in lithofacies with shale contents less than 15%. The clay contents of LF9, LF10 and LF11 are lower than 15%, and the grain sizes of the sediments are relatively large, thus, these lithofacies are mainly composed of carbonate cementation (Table 3). The clay contents of some samples from LF2, LF4, LF6 and LF7 are lower than 15%, while the clay contents of other samples from these lithofacies are higher than 15%. The sediment grain sizes are relatively moderate. Therefore, both clay cementation and carbonate cementation may develop in these lithofacies. The type of cementation that develops depends on the clay content of specific samples.

Pore types and reservoir classification

By observing the thin sections in the study area, the primary and secondary pore types are studied. The primary pores are mainly intergranular pores (Fig. 10J), whereas the secondary pores are mainly intergranular dissolved pores formed by dissolution (Fig. 10K).

On the basis of the porosity‒permeability relationships of lithofacies with different depositions and diageneses, the petrophysical characteristics of lithofacies with different depositions and diageneses are analyzed by applying the standard Chinese Petroleum Conventional Sandstone Reservoir Classification and Evaluation (SY/T6285-1997) (Fig. 13). This standard divides the reservoir into 5 types, including I (POR ≥ 25 and PERM ≥ 1000mD), II (POR ≥ 20 and PERM ≥ 100mD), III (POR ≥ 15 and PERM ≥ 10mD), IV (POR ≥ 10 and PERM ≥ 1mD), V (POR < 10 or PERM < 1 mD). The type I reservoirs in the study area are less developed and include mainly LF2, LF7 and LF9, which are braided channel microfacies with low clay contents in the original sediments and with coarse grain sizes. The subsequent diagenetic evolution is dominated by carbonate cementation, with intergranular pores and intergranular dissolved pores (Table 3). The production can reach 320 m3/d in the layer IV of well Z4. The type II reservoirs in the study area are well developed, including LF7, LF9, LF6 and LF8, which mainly consist of braided channel microfacies and braided channel lateral border microfacies. The clay content is low, and the grain size of the original sediment is coarse. The subsequent diagenetic evolution results in both carbonate cementation and clay cementation, with intergranular pores and intergranular dissolved pores (Table 3). The production can reach 200 m3/d in the layer III of well Z2. The type III reservoirs in the study area are well developed and include LF7, LF3, LF6, LF2 and LF4, which are mainly braided channel microfacies, braided channel lateral border microfacies and braided channel front microfacies, respectively. The original sediment has a high clay content and relatively fine grain size, and the subsequent diagenetic evolution is dominated by clay cementation, which mainly involves the development of intergranular pores (Table 3). The production can reach 70m3/d in the layer II of well Z5. The type IV reservoirs are well developed and mainly consist of LF7, LF9, LF5 and LF2, which are braided channel lateral border microfacies, braided channel front microfacies, interchannel microfacies and slump debris flow microfacies, respectively. The original sediment has a high clay content and relatively fine grain size, and the subsequent diagenetic evolution is dominated by clay cementation, which mainly involves the development of intergranular pores (Table 3). The production can reach 20m3/d in the layer I of well Z1. The type V reservoirs are well developed and mainly consist of LF5, LF1 and LF12, which are composed of sheet sand microfacies, interchannel microfacies and channel lateral border microfacies. The original sediment has a high clay content and relatively fine grain size, and the subsequent diagenetic evolution is dominated by clay cementation, which mainly involves the development of intergranular pores (Table 4).

Discussion

Origin of high-quality reservoirs

High-quality reservoirs refer to type I and type II reservoirs, which usually have high oil production levels. The formation of high-quality reservoirs in the study area is influenced by both sedimentary processes and diagenesis. Sedimentation not only controls the original porosity of sediments but also determines the type of diagenetic evolution sequence to be developed later, which is the most critical factor for the formation of high-quality reservoirs. Diagenesis transforms the original porosity of sediments, which is a secondary factor contributing to the formation of high-quality reservoirs in the study area. The initial porosity of the original sediments in braided channels with strong hydrodynamic forces is high, resulting in carbonate cementation and the formation of high-quality reservoirs in the study area. The braided channel lateral border and slump debris flow facies with strong hydrodynamic forces have high initial porosities and are dominated by clay cementation, forming subhigh-quality reservoirs in the study area. The hydrodynamic force of the braided channel front is weak, and the initial porosity of the sediment is low. Although the subsequent cementation is primarily carbonate, the reservoir petrophysical properties are poor. Interchannel facies and sheet sand microfacies have weak original sedimentary hydrodynamic forces, small initial sediment porosities, primarily clay cementation development and poor reservoir petrophysical properties, making it difficult for reservoirs to form.

Sedimentary diagenetic evolution model

On the basis of the comprehensive analysis of sedimentary diagenesis in the study area, a sedimentary diagenetic evolution model is established. During deposition in the study area, the provenance is from the southeast and southwest23, and two stages of subaqueous fan deposition develop22 (Fig. 14A). The hydrodynamic forces in different depositional areas significantly differ, resulting in sedimentary differentiation. Rocks with different colors, compositions, and grain sizes, among other features, are deposited in different areas. Owing to the influences of irregular factors such as earthquakes, LA1 develops on slopes with relatively poor sorting characteristics, which are indicative of slump debris flow. LA2 develops in a braided channel with a low clay content and coarse sediment grain size. The LA3 lithofacies association develops on the lateral border of the braided channel, and its clay content is higher than that of the channel. FA4 occurs in the intrachannel channel, with a clay content that is higher than that of the lateral border of the braided channel. FA5 develops in the braided channel front and is mainly composed of fine siltstone; it has a relatively low clay content (Fig. 14B and C).

Sedimentary diagenetic evolution model of the F4 Formation in the Z oilfield: (a) macroscopic sedimentary characteristics of the F4 Formation in the Z oilfield; (b) development characteristics of a single fan in the F4 Formation in the Z oilfield; (c) profiles of different positions of a single fan in the F4 Formation in the Z oilfield; and (d) diagenetic evolution characteristics of the F4 Formation in the Z oilfield.

In the synsedimentary marine diagenesis stage41,42, LA2 and LA5 are dominated by calcite cementation and dolomite cementation, with quartz cementation developing locally, whereas other lithofacies associations mainly develop clay cementation (Fig. 14D). In the synsedimentary marine diagenesis stage, due to the influence of compaction, sediments begin to experience point contacts, line contacts and even concave–convex contacts. In the early stage of diagenesis, calcite cementation occurs in the second stage, dolomite cementation and clay cementation begin to occur, and siderite cementation develops in the clay cementation zone. In the late diagenetic stage, dissolution occurs, which leads to calcite cementation and dolomite cementation easily dissolving and forming dissolution pores. However, clay cementation and quartz cementation are relatively difficult to dissolve, thus, the influence of dissolution is almost undetectable. Because of the influence of tectonic movements, structural fractures subsequently develop locally in the study area.

Conclusion

In the study area, on the basis of core, thin-section, grain size, logging and petrophysical property data, the lithofacies types and characteristics of subaqueous fan reservoirs were analyzed, the diagenetic types and evolutionary sequences were defined, the origins of high-quality reservoirs were revealed, and a sedimentary diagenetic evolutionary model was established.

-

1.

There were 12 lithofacies in the study area, including gray‒black mudstone facies (LF1), mudstone conglomerate facies with massive bedding (LF2), interbedded sand‒mudstone facies (LF3), siltstone facies with parallel bedding (LF4), siltstone facies with wavy bedding (LF5), cross-bedded siltstone facies (LF6), massive siltstone facies (LF7), wavy bedding fine sandstone facies (LF8), massive fine sandstone facies (LF9), massive bedding medium sandstone facies (LF10), massive/coarse sandstone facies (LF11) and grain-size graded coarse sandstone facies (LF12).

-

2.

Six kinds of lithofacies associations and corresponding sedimentary facies developed in the study area. A sedimentary facies identification chart was established to depict the spatial development characteristics of the sedimentary facies in the study area. The study area was mainly composed of braided channel sedimentary facies and lateral border facies.

-

3.

There were four diagenetic types in the study area, namely, compaction, cementation, dissolution and fracturing, and four diagenetic sequence evolutions, namely, clay cementation, calcite cementation, dolomite cementation and quartz cementation sequences. LA2 and LA5 were dominated by carbonate cementation, whereas other lithofacies associations were dominated by clay cementation.

-

4.

The origin of high-quality reservoirs in the study area was affected by both sedimentary processes and diagenesis. Sedimentation not only affected the original porosity of sediments but also controlled the evolutionary sequence of diagenesis, which was determined to be the most critical factor affecting the formation of high-quality reservoirs. Diagenesis transformed the original porosity of sediments and was a secondary factor influencing the formation of high-quality reservoirs. The high-quality reservoirs in the study area were distributed mainly in channels that were cemented by carbonate and had strong hydrodynamic forces.

Data availability

Yes, we have research data to declare. All the data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

References

Saito, T. & Ito, M. Deposition of sheet-like turbidite packets and migration of channel-overbank systems on a sandy submarine fan: an example from the Late Miocene-Early Pliocene forearc basin Boso Peninsula, Japan. Sedimen. Geol. 149(4), 265–277 (2002).

Zhang, X. Sedimentary characteristics and models of offshore underwater fans in terrestrial faulted lake basins—Taking the Tainan Depression in the Haita Basin as an Example. West-China Explor. Eng. 26(12), 61–64 (2014).

Cao, L. et al. Sedimentary types and depositional models of glutenite bodiesin Manite Depression Erlian Basin, China. J. Chengdu Univ. Technol. (Science & technology edition) 49(4), 491–501 (2022).

Liu, H. et al. Sedimentary process simulation and exploration implication of glutenite body instepped fault -ramp zone: a case study of the upper submember of Member 4of Shahejie Formation in Shengtuo area of dongying sag. Acta Petrolei Sinica 43(9), 1269–1294 (2022).

Yang, B. et al. Sediment transport mechanism and development characteristics of subaqueous fan in the northern steep slope zone of Lijin sag. J. China Univ. Petrol. (Edition of Natural Science) 46(2), 25–37 (2022).

Pang, X., Wang, G., Zhao, M., Wang, Q. & Zhang, X. The reservoir characteristics and their controlling factors of the sublacustrine fan in the Paleogene Dongying Formation Bohai Sea, China. J. Palaeogeogr. 13(1), 127–148 (2024).

Mitchell, W. H., Whittaker, A. C., Mayall, M. & Lonergan, L. New models for submarine channel deposits on structurally complex slopes: Examples from The Niger Delta system. Marine Petrol. Geol. 129, 105040 (2021).

Hansen, L. A. et al. Genesis and character of thin-bedded turbidites associated with submarine channels. Marine Petrol. Geol. 67, 852–879 (2015).

Hage, S. et al. How to recognize crescentic bedforms formed by supercritical turbidity currents in the geologic record: Insights from active submarine channels. Geology 46(6), 563–566 (2018).

Lang, J., Brandes, C. & Winsemann, J. Erosion and deposition by supercritical density flows during channel avulsion and backfilling: Field examples from coarse-grained deepwater channel-levée complexes (Sandino Forearc Basin, southern Central America. Sed. Geol. 349, 79–102 (2017).

Shanmugam, G., Deep-water processes and facies models: Implications for sandstone petroleum reservoirs. In Handbook of Petroleum Exploration and Production. Elsevier Science, 1–496, (2006).

Butt, M. N. et al. Depositional and diagenetic controls on the reservoir quality of Early Miocene syn-rift deep-marine sandstones, NW Saudi Arabia. J. Asian Earth Sci. 259(105880), 1–20 (2024).

Pringle, J. K., Westerman, A. R., Clark, J. D., Drinkwater, N. J. & Gardiner, A. R. 3D high-resolution digital models of outcrop analogue study sites to constrain reservoir model uncertainty: an example from Alport Castles Derbyshire, UK. Petrol. Geosci. 10(4), 343–352 (2004).

Umar, M., Friis, H., Khan, A. S., Kassi, A. M. & Kasi, A. K. The effects of diagenesis on the reservoir characters in sandstones of the Late Cretaceous Pab Formation Kirthar Fold Belt, southern Pakistan. J. Asian Earth Sci. 40(2), 622–635 (2011).

Marchand, A. M., Apps, G., Li, W. & Rotzien, J. R. Depositional processes and impact on reservoir quality in deepwater Paleogene reservoirs US Gulf of Mexico. AAPG Bull. 99(9), 1635–1648 (2015).

Zhang, J. et al. Application of 4-D monitoring to understand reservoir heterogeneity controls on fluid flow during the development of a submarine channel system. AAPG Bull. 20, 299–315 (2018).

Wang, M. et al. Quality variations and controlling factors of deepwater submarine-fan reservoirs Rovuma Basin, East Africa. Petrol. Explor. Develop. 49(3), 560–571 (2022).

Bello, A. M. et al. Impact of depositional and diagenetic controls on reservoir quality of syn-rift sedimentary systems: An example from Oligocene-Miocene Al Wajh Formation, northwest Saudi Arabia. Sed. Geol. 446(106342), 1–12 (2023).

Bakr A. K. Stratigraphic and Diagenetic Controls on Asl Reservoir in Downthrown Side, October Field, Gulf of Suez: Implications for Reservoir Quality, SPE, D031S031R007, (2024).

Zhang, J. et al. Sedimentary geochemical and reservoir characteristics of the Quaternary submarine fan in the Qiongdongnan basin. Deep Sea Res. Part I Oceanogr. Res. Papers 215, 104429 (2025).

Li, S. Sedimentary microfacies modelling for submarine fan in Zarzaitine Oilfield. Fault-block oil&gas 14(3), 31–33 (2007).

Li, S., Deng, H., Wu, X. & Zhang, H. Sedimentary characteristics and evolution of Lower Devonian in Zarzaitine Oilfield Eastern Algeria. Pet. Explor. Dev. 33(3), 383–387 (2006).

Zheng, W., Wu, X. & Deng, H. Stratigraphy and facies distribution of lower Devonian F 4 Unit in Zarzaitine Oilfield Illizi Basin, Algeria. Earth Sci. 37(1), 181–190 (2012).

Chen, L. Petrological characteristic study of F4 reservoir in Zarzaitine Oilfield. Inner Mongolia Petrochem. Ind. 11, 133–136 (2009).

Sun, G. Enhanced Oil Recovery Technology Research and Application of F4 Reservoir in Zarzaitine Oilfield in Algeria 1–43 (China University of Geosciences, 2013).

Baouche, R., Sen, S., Sadaoui, M., Boutaleb, K. & Ganguli, S. S. Characterization of pore pressure, fracture pressure, shear failure and its implications for drilling, wellbore stability and completion design–a case study from the Takouazet field, Illizi Basin, Algeria. Mar. Pet. Geol. 120, 104510 (2020).

Zhang, Z. et al. Early Paleozoic lithofacies palaeogeography evolution characteristicsof ghadames basin in North Africa. J. Palaeogeogr. 26(1), 1–13 (2024).

Ji, C. Sequence Stratigraphy and Sedimentary Facies Analysis in F4 of Zarzaitine Oil Field 1–73 (China University of Geosciences, 2011).

Di Giulio, A. et al. Diagenetic history vs. thermal evolution of Paleozoic and Triassic reservoir rocks in the Ghadames-Illizi Basin (Algeria-Tunisia-Libya). Mar. Pet. Geol. 127, 104979 (2021).

English, K. L., Redfern, J., Corcoran, D. V., English, J. M. & Cherif, R. Y. Constraining burial history and petroleum charge in exhumed basins: New insights from the Illizi Basin Algeria. AAPG Bull. 100(4), 623–655 (2016).

Boote, D. R., Clark-Lowes, D. D. & Traut, M. W. Palaeozoic Petroleum Systems of North Africa 7–68 (Geological Society London Special Publications, 1998).

Galeazzi, S., Point, O., Haddadi, N., Mather, J. & Druesne, D. Regional geology and petroleum systems of the Illizi-Berkine area of the Algerian Saharan Platform: An overview. Mar. Pet. Geol. 27(1), 143–178 (2010).

Nichols, G. Sedimentology and stratigraphy 1–77 (John Wiley & Sons, 2009).

Jamil, M. et al. Facies analysis and distribution of Late Palaeogene deep-water massive sandstones in submarine-fan lobes, NW Borneo. Geol. J. 57(11), 4489–4507 (2022).

Zhang, C. et al. Deposystem architectures and lithofacies of a submarine fan-dominated deep sea succession in an orogen: A case study from the Upper Triassic Langjiexue Group of southern Tibet. J. Asian Earth Sci. 111, 222–243 (2015).

Beard, D. C. & Weyl, P. K. Influence of texture on porosity and permeability of unconsolidated sand. AAPG Bull. 57, 349–369 (1973).

Han, G. et al. Quantitative study on diagenetic characteristics and pore evolution of middle-deep tight sandstone reservoirs: a case study of the second Member of Kongdian Formation in Nanpi slope, Cangdong sag. J. Palaeogeogr. 25(4), 945–958 (2023).

Yu, J. et al. Diagenesis and diagenetic facies of upper Wuerhe formation in the Shawan sag. Geoscience 36(04), 1095–1104 (2022).

Peter, A., Scholle, Dana, S., Ulmer-Scholle. A color guide to the petrography of carbonate rocks: grains, textures, porosity, diagenesis. Tulsa, Oklahoma. AAPG Memoir 77, (2003).

Zhu, N., 2019. Diagenetic Differences and Genetic Mechanisms of Triassic Baikouquan Formation Reservoirs from Circum-Mahu Depression. China University of Petroleum (EastChina), 1–75.

Ronchi, P., Ortenzi, A., Borromeo, O., Claps, M. & Zempolich, W. G. Depositional setting and diagenetic processes and their impact on the reservoir quality in the late Visean-Bashkirian Kashagan carbonate platform Pre-Caspian Basin Kazakhstan. AAPG Bull. 94(9), 1313–1348 (2010).

Wang, H. et al. Control of depositional and diagenetic processes on the reservoir properties of the Mishrif Formation in the AD oilfield, Central Mesopotamian Basin, Iraq. Mar. Pet. Geol. 132, 105202 (2021).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Major Science and Technology Project, Enrichment Patterns and Key Exploration & Development Technologies of Global Deepwater Oil and Gas Resources (2024ZD1406501) and CNPC Research on Key Technologies for Overseas Deepwater Oil and Gas Field Exploration and Development Projects (2023-SC-01-03) and CNPC Basic and Prospective Key Scientific and Technological Project (2021DJ24). The authors would like to thank the anonymous reviewers for their comments and very helpful suggestions.

Funding

CNPC Basic and Prospective Key Scientific and Technological Project, 2021DJ24, National Major Science and Technology Project, Enrichment Patterns and Key Exploration & Development Technologies of Global Deepwater Oil and Gas Resources, 2024ZD1406501, CNPC Research on Key Technologies for Overseas Deepwater Oil and Gas Field Exploration and Development Projects,2023-SC-01-03

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Changhai Li and Weiqiang Li analyzed the results. Changhai Li conducted the experiment(s). Changhai Li wrote the main manuscript text. Hui min Ye, Qiang Zhu, Xuejun Shan, and Shengli Wang prepared Figs. 1, 2 and 12. Ziyu Zhang improved the language and prepared Fig. 5. Xianjie Zhou, Zixin Xue and Rongtu Ma prepared Figs. 5, 6 and 7. All the authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, C., Li, W., Ye, H.m. et al. Controls of reservoir quality for submarine fan of F4 Formation in the Z oilfield, Illizi Basin, Algeria. Sci Rep 15, 28457 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-12570-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-12570-x