Abstract

The synthesis of metal complexes (MCs) by green tea dye ligands improves environmental impact and reduces costs. The result of the current work establishes the production of metal complexes with huge amount and is an attempt from laboratory scales into commercial extent. This study investigates the application of green chemistry in producing PVA-based composites incorporating metal complexes, leading to enhanced light-matter interactions. The FTIR approach established that green tea dye (GTD) is enriched with ligands containing NH/OH, C = C, and C = O functional groups, which capture Pb2+ metal ions and form Pb-metal complexes. The FTIR indicates the peaks at 1404 and 1545 cm−¹ associated with the symmetric and asymmetric stretching of the carboxylate group (COO−) anion of the Pb(CH3COO)2 salt, while their disappearance in Pb-metal complexes (PbMC), establishing the coordination interactions among Pb2+ ions and polyphenol GTD ligands. It was found that integrating PVA solution with washed PbMC solution using a casting method is a novel green methodology for delivering PVA-based composites. The structural and optical properties of PVA: PbMC composites have been examined using XRD, FTIR, SEM and (UV-Vis) spectroscopy. The XRD pattern has confirmed that the semi-crystalline PVA film is transformed into an amorphous material in PVA/PbMC films. The FTIR spectra of the films demonstrated a significant interaction between polar PVA and PbMCs. The FESEM is a method employed to examine the morphological properties of materials, clarifying their surface structure, form, and texture. UV-Vis was used to study a wide range of optical parameters, including the dispersion energy (Eo and Ed), zero-frequency refractive index (no), oscillator wavelength, and strength (λo, So), which were determined using the Wemple–DiDomenico (WD) single oscillator model. An increase in Urbach tail (Eu) energy, linear and nonlinear refractive indices, and dielectric constant of polymer films, in addition to a reduction in energy gap Eg from (6.17 to 1.56 eV), was reported, with various models yielding matching outcomes. The absorption spectrum fitting (ASF) utilizing Tauc’s models optically determined the physics of the type of transition electrons from the filled valence band (VB) to the empty conduction band (CB). The linear and nonlinear susceptibilities, χ(1), and χ(3), were enhanced by PbMC doping. The acquired values qualify our synthesized materials for use in light-emitting diodes and image sensors. The film quality coefficient figure of merit (FOM), sheet resistance (Rs), and thermal emission (εTh) have been discovered as functions of wavelength. Examining the PVA/PbMC films suggested they may be suitable for optoelectronic devices, solar cell radiation monitoring, and several other applications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The continuous search for novel ligands that can effectively bind Pb(II) is a key focus of research.

The broad and complex coordination chemistry of Pb(II) is attributed to its substantial size coupled with a 6s2 electron pair, which may either stay inert or exhibit stereactivity1. Lead has been classified as one of the most toxic elements to human health. It is present in the environment as a result of insufficient disposal. It has been reported that lead is everywhere in the atmosphere, aquatic environments, soil, animal tissue, and plant matter2. In this research, the Pb is captured by some polyphenol ligands to decrease toxicity. Metal ions present significant environmental hazards since they can pollute aquatic environments, resulting in permanent and/or fatal risks to plants, animals, and humans. Human health risks may arise from some bioaccumulative metals with a long half-life (T1/2), even at low doses3. The captured polyphenols by central metal Pb are extracted in (GTD). GT leaf includes tea saponins, polyphenols, amino acids, caffeine, and tannins, with around 10–30% and 2–4% (w/w) polyphenols and caffeine, respectively. Tea polyphenols contain catechins, flavanones, glycosides, phenolic acids, flavanols, and the aglycones of plant colors. They are soluble in water, ethanol, methanol, acetone, and other solvents4. The composition of solution of GT is chemically defined by the presence of polyphenolic catechins, namely: (-) (EGCG) epigallocatechin-3-gallate, (-) (EGC) epigallocatechin, (-) (ECG) epicatechin-3-gallate, (-) (EC) epicatechin approximately 59%, 19%, 136% ad 6.4%of the toal of catechins5. The physical properties of polyphenols encompass their solubility, light absorption, molecular weight, melting point, and optical variation in ethanol6. Polyphenol ligands function as Lewis bases, resulting in significantly elevated metal-binding stability constants with Lewis acids, such as Pb2+, to introduce lead metal complexes (PbMCs)7. Ligands are typically classified as bases with electron-donating groups, specifically oxygen or nitrogen functionalities, including hydroxyl, carboxylate, or amine moieties8. Green method complexation with metal ions occurs when polyphenols contain two structurally similar rings, with a particular ring mainly interacting with transition metal ions by donating a pair of electrons9. An essential ligand can occupy the unoccupied d orbitals of transition metal ions to create a very stable and soluble metal complex. Besides establishing coordination bonds, chelation entails the creation of stable rings, as the metal-ligand link (including d orbitals) imposes fewer geometrical limitations than C-C or C-N bonds8.

Incorporating the Pb metal complexes into a polar polymer matrix permits the properties of PbMCs and polymers to be shared. Polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) is a crucial polymer utilized in the industry. It possesses the advantage of superior performance in film production. It is a water-soluble polymer with controlled flexibility, comprising up to 99% hydroxyl groups in its primary molecular chain. The easy processing characteristics, eco-friendly attributes, economical nature, and plentiful functional groups render PVA a favored material in the formation of networks in both physically and chemically compounded substances10,11. PVA’s structure comprises a carbon backbone chain with hydroxyl groups (OH) interacting with PbMCs. The hydroxyl groups can facilitate hydrogen bonding, hence assisting in creating a polymer composite12,13. The novelty of the doping of PVA by metal complexes is described in this research. This finding also suggests that the impact enhances the linear and nonlinearity of the optical parameters and may play a more crucial role in the optical properties, especially optical energy band gap Eg and refractive indexes n, than the traditional techniques such as polymer electrolyte, nanoparticle doping, polymer blending, and other doping. Understanding the fundamental optical properties of polymers may enhance device performance and facilitate further advancements. The analyzed optical characteristics of polymer materials encompass absorption, reflection, emission properties, and fundamental optoelectronic device functionality14. In the experiment conducted by Bhargav et al.15, an effort has been made to describe polymer electrolytes composed of (PVA) complexed with Sodium Iodide (NaI) salt at various weight percentages. They noted that the direct and indirect band gap values for pure PVA were measured at 5.4 and 4.90 eV, while the values for doped films were 4.90 and 4.40 eV, respectively. Krishnakumar and Shanmugam16 investigated PVA and PEG glycol doped with Pb(NO3)2 salt, and they indicated the complex synthesis of the polymer electrolyte (polymer with salt) with Pb(NO3)2. The results demonstrated that the Eg values dropped from 6.13 to 5.03 eV. Arulmozhi and Mythili17 synthesized lead oxide (PbO) nanoparticles utilizing Pb(II) acetate as the source. They noted the Eg of PVA polymer decreases from 3.88 to 3.80 eV (0.08 eV), demonstrating that the band gap increases when particle size decreases. Based on previous research, Brza and Khayal’s paper, it is evident that metal complexes significantly reduce the energy band gap (Eg) of PVA polymers. These complexes have been shown to have a greater impact on PVA’s band structure than Pb salts and Pb nanoparticles, highlighting their novelty and potential in modifying the polymer’s optical properties. Donyaa et al.18 synthesized and examined the optical spectroscopy of PVA/iron polymer nanocomposites. The observations of the PVA/iron oxide polymer nanocomposites exhibited a red shift in the absorption edge corresponding to the iron oxide content, with the bandgap energy (Eg) decreasing from 5.5 to 3.28 eV. The bandgap energy (Eg) is significant and closely associated with various properties and parameters. Several optical characteristics directly linked to Eg in PVA composites, such as optical absorption, figure of merit, Urbach energy, and oscillation parameters, also enhance the dielectric constant and refractive index, making this material suitable for optoelectronic applications. Furthermore, Zyoud et al.19 studied the optical properties of PVA/PVP-blend polymers with various amounts of (PB-Nd+ 3). They found that the indirect bandgaps for the chosen composites were estimated to decrease from 5.6 to 4.82 eV, whereas the direct energy gaps decreased from 6.09 to 5.83 eV with increasing dopant ratios.

Based on the information provided, most studies have focused on enhancing the optical properties of polymers by employing traditional methods or nanoparticles. However, in this study, we introduced a new method to improve the optical properties of PVA because the interactions between PbMCs and PVA can alter the material properties and change the band structure, which opens the door to adjusting the composite’s characteristics. Transmittance, absorbance, index of refraction (n), merit figure, surface resistance, Eg, optical and electrical conductivity, and nonlinear optical parameters are among the optical properties studied and interpreted for the synthesized composites. Modern, large-scale electrical and optoelectronic devices are also made using doped films. This research is novel from the viewpoint of green synthesis of Pb metal complexes and their combination with PVA polymer to deliver PVA-based composites with enhanced light-matter interactions. The current study’s findings demonstrate that green-synthesized metal complexes are capable of modulating the optical band gap of water-soluble polymers. The synthesis of PbMC is considered environmentally beneficial and aligns with the principles of green chemistry. The synthesis by this method serves as an alternative source, facilitating a quicker synthesis process than the traditional synthesis. An alternating method for synthesizing metal complexes involves utilizing bioresources, such as plants (GT). “Green” synthesis is characterized by low toxicity and is safe for both human health and the environment, making it the optimal method for acquiring metal complexes. Another advantage of our method is that it is low-cost and can prepare a larger amount in a shorter time. Polymer composites with small optical Eg are crucial for various applications, including photonics and optoelectronics. This study makes a balance between the research and environment, ascribing to the fact that green tea dye is nontoxic and could be used to capture a toxic heavy metal ion such as pb2+ and change it to the metal complex, which is a solid material and can be separated from the solution due to its precipitation properties as a solid. Thus, this study employs a green methodology to purify water resources from heavy metal ions that exist as dissolved ions in water. Batoola and Saleh20 elimination of toxic metals from wastewater in engineered wetlands as a green method; the catalytic role of substrates and chelators. Vraspir and Butler21 examined the creation of metal complexes, wherein several significant trace metal ions, such as iron, cobalt, nickel, copper, zinc, and cadmium, are complexed by organic ligands in seawater, therefore illuminating the speciation of these metal ions in the ocean. They demonstrated that free metal is more hazardous than the complexed metal, as the former is considered more bioavailable. Consequently, the elevated level of complexation may reduce toxicity. On the other hand, using these metal complexes to fabricate polymer composites is an original research methodology that minimizes cost and time. This work opens new field for research and establish green inorganic chemistry. The results shown in this work satisfy that less than minutes inorganic metal complexes can be produces and thus saving of time and cost.

Experimental synthesis of Pb metal complex and films Preparation and sample characterization

The solvent casting method has been used to fabricate PVA-PbMCs composite films.

The PVA solution, functioning as the host material, was prepared by carefully 4 g of pure PVA powder (average molecular weight = 17000–18000 g/mol) with 200 mL of distilled water at 90 °C, followed by stirring with a magnetic stirrer for approximately 2 h to achieve a transparent, homogeneous solution.

The green tea (GT) purity powder had been purchased at a local market in London; approximately 24 g of the dry GT sample was dissolved in 800 mL of distilled water (D.W.), yielding the green tea dye (GTD) at around 95 °C. The GTD solution was filtered using Whatman paper, 41 with a pore dimension of 20 μm (cat. no. 1441), and the residues were suspended in subsequent quantities of solvent for re-extraction. The procedure was carried out three times. The compounds of GTD consists of caffeine, (–)-(EGC), (–)-(EC), (–)-(EGCG), and (–)-(ECG) based on literature and shown in Scheme 1. Pb2+ central ions were synthesized from lead acetate Pb(CH3COO)2. 10 g of Pb(CH3COO)2 was dissolved in 200 mL of (D.W.) and stirred with a magnetic agitator for approximately one hour to achieve a clear solution. Lead metal complexes have been produced by combining lead acetate solution with extracted GTD. At 70 °C, the GTD was stirred, and lead acetate was incorporated into the GTD. PbMCs were synthesized using cations Pb2+ from salt and polyphenols (PPHs) in GTD. The video in the supplementary materials shows that, instantaneously and within less than a minute, the metal complex starts to form. The separation of metal complexes and their precipitation, as shown in the supplementary materials, establishes that tea dyes are crucial in delivering a high quantity of metal complexes. The complex concoction was allowed to cool until it reached ambient temperature. Following multiple washes with DW, the complexes were isolated in 100 mL of the solvent to yield lead metal complexes (PbMCs). The PbMCs and PVA polar polymer material were synthesized by combining the two components and stirring for one hour at ambient temperature. The production of PVA/PbMCs was confirmed when the initially clear PVA polymer solution transitioned to a light brown color. The samples were designated PVPbMC0, PVPbMC1, PVPbMC2, and PVPbMC3, indicating 50 mL of PVA mixed with 0 mL, 9 mL, 18 mL, and 36 mL of a solution (PbMCs) as shown in Schematic 2 and Table 1. Films were produced at ambient temperature following the evaporation of the solution in desiccated Petri dishes. Subsequently, the films were placed in a silica gel desiccator for further desiccation before the characterization phase.

The structure, interaction, morphology, and optical characterization of pure polar (PVA) and composite films (PVA/PbMCs) have been investigated using XRD, FTIR, FESEM and UV–Vis spectroscopy; the range and the model of the characteristic techniques are illustrated in Table 2.

Results and discussions

XRD analysis

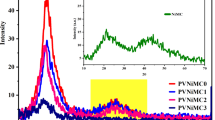

Figure 1 illustrates the XRD patterns of the polar PVA and PVA/PbMCs composite films. An increase in PbMCs concentration resulted in modifying the PVA characteristic peak. The peaks at 2θ = 19.2°, and 41.3° are attributed to the PVA polymer22. The distinctive peak of PVA (2θ = 19.2°) broadens assigned to the (101) crystallographic plane, and its intensity decreases as the concentration of PbMCs in the PVA matrix increases; Le et al. also reported a similar behavior of XRD spectra of PVA, which was doped by Ni nanoparticles23,24. This verifies a reduction in PVA crystallinity. The phenomenon arises from forming hydrogen bonds between the surfaces of PbMCs and the hydroxyl groups in PVA macromolecules, thereby decreasing the interactions among polymer chains within the macromolecules. Consequently, it disturbs the polymer structure and reduces the crystallinity of PVA25. The primary source of the structure intermediate between crystalline and amorphous orders is the inter-macromolecular interactions among the molecules in the PVA matrix through hydrogen bonding, which induces a partial ordering of the chains26. The XRD pattern of powdered PbMCs, illustrated in the inset of Fig. 1, exhibited peaks at 2θ = 27.7° and 44°. In pure polar PVA, there is no peak at 2θ = 27.7°. However, this peak is strongly observed in composite PVA/PbMC samples, indicating a strong interaction between polar PVA and PbMCs. No strong peaks at 2θ = 44° corresponding to PVA/PbMC were found; however, a light, intense peak was observed at 2θ = 41.3° due to reflections from the (220) plane. It signifies the amorphous nature of composite samples. These observations validate that the current polymer composite is amorphous. However, incorporating PbMCs into the PVA system steadily reduces the strength of this peak, indicating a decrease in crystallinity within the complex16,27. No new peaks have been identified in the complex films, but amorphocity was increased28. This signifies a thorough interaction between the metal complex and the polymer matrix, confirming that no new phase has emerged in the synthesized polymer system29. Patel et al. obtained the same outcomes for lead sulfide (PbS) nanoparticles in a 1:1 combination of polyvinyl pyrrolidone (PVP) and (PVA)27.

FTIR spectroscopy studies

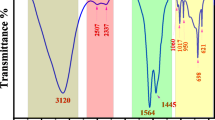

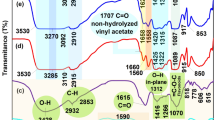

Figure 2a shows the FTIR of the Pb(CH3COO)2. The principal absorbance peaks of lead acetate are observed at 2930–2976 cm− 1 and 1020 cm− 1, which correspond to C-H and C-O stretching, respectively. The peak at 669 cm− 1 strongly indicates a characteristic metal–oxide bond attributable to the Pb-O stretching30. The peak at 1545 cm− 1 for Pb(CH3COO)2 salt was attributed to the COO anion stretching vibration31. The band identified at 3458 cm− 1 matches the stretching vibrations of OH. The C = C bond corresponds to a peak at 2330 cm− 1. The OH bending vibration in adsorbed water exhibits a prominent peak at approximately 1404 cm− 132. The FT-IR spectrum range of the GTD sample is presented in Fig. 2b. Table 3 presents the vibrational band assignments for the significant peaks and the identified chemical compounds. The transmittance (%) of the chosen vibrational bands obtained from the FTIR spectrum of the GTD sample is displayed in Table 3. The 3415, 2925, and 1630 cm− 1 bands may match the OH, C–H bond stretching in, and C = O, respectively33,34,35. The PbMC FTIR spectrum analysis reveals distinct bands indicative of the primary functional groups involved in Pb(II) loading. Upon comparing Fig. 2a with b, it is evident that the PbMCs exhibit alterations in the locations and intensities of some peaks. Upon synthesizing PbMCs, the stretching band at 3458 cm− 1, associated with lead acetate, and 3415 cm− 1, related to GTD, shifts to 3403 cm− 1 and exhibits broadening36. The stretching bands of salt and GTD at 1545 and 1630 cm− 1(C = O in the –COO − group) shifted to 1610 cm− 1(Fig. 2c). The vibrational bands associated with lead salt and GTD at 1020 and 1043 cm − 1 (indicative of C-O) shift to 1063 cm− 1, with peak intensity and broadening alterations, as shown in Table 3. The alteration in wavenumber indicates a variation in the energy of the functional group, confirming the participation of carboxyl, hydroxyl, and particularly NH groups in creating a lead metal complex37,38. Schematic 3 illustrates the proposed interaction between polar PVA and PbMC, resulting from the interaction between the hydroxyl groups of PVA and the hydrogen or amine groups of PbMC.

Figure 3 demonstrates the physicochemical characterization of the materials by FTIR, aimed at explaining the interactions between the PVA polymer and PbMCs. The primary distinctions between the Pure polar PVA and PVA/PbMC spectra show as decreased intensity and larger bands. The influential bands signify the contributions from the vibrations of PVA groups and PbMC. In contrast, the bands at 3302 and 1555 cm− 1 correspond to the stretching of OH and NH in amide II, respectively. The PVA/PbMC samples exhibit an evident band at 3292 and 1565 cm− 1, indicating that the PbMC interacted with the PVA polar polymer through functional groups OH and C = C backbone39,40. All FTIR bands of the samples are presented in Fig. 3a–d related to PVPbMC0, PVPbMC1, PVPbMC2 and PVPbMC3 respectively and Table 3.

FESEM morphological analysis

FESEM investigation was used to predict the physical characteristics and surface roughness, including shape, size, and surface morphology, such as the presence of voids and pores41. Figure 4 illustrates the FESEM results for pure PVA and its composites inserted with metal complexes. It can be seen that pure PVA doesn’t exhibit any cracks, while the PVA films including various amounts of metal complexes show some pores and aggregate particles. The denser network on the PVA surface at 1 kx magnification could be ascribed to many PVA nano-fibers or folded filaments of PVA. The aggregated particles of the composite samples exhibited no cracks or agglomerations and were denser and more compact compared to those of the pure PVA matrix. The white networks that appeared on PVA surfaces could be ascribed to pure PVA nano-fibers. During the casting process and solvent evaporation, PVA fibers will be produced and appear on the PVA film surface, especially at high magnification, as seen at 3 kX magnification. Shah eta la42, also observed such nano-fibers for PVA composites inserted with CNT and ZnO and prepared by electrospinning and solution casting techniques, respectively. Mollá and Compa43, established that the technology of electrospinning will deliver PVA fibers with nano-sizes in the range of 200 –300 nm for images captured on an area of about 10 μm. The results of the present work indicate that low-molecular-weight PVA, obtained by the casting approach, will also deliver PVA nano-fibers. In our previous work44,45, we did not observed such nano-fibers for PVA. This may be related to the fact that in our earlier study, low magnification was used during sample investigation, whereas in this work, high magnification was employed. It is evident that with an increase in the amount of Pb-metal complexes, the PVA fibers are disrupted, and particles of large size appear. Moreover, the pores with large sizes appeared at high concentrations of metal complexes. The well-dispersed metal complexes and rupture of PVA nano-fibers are evidence of a good interaction between the PVA host chain segments and the inserted Pb-metal complexes.

The FESEM image for (a, a*) PVPbMC0, (b, b*) PVPbMC1, (c, c*) PVPbMC2 and (d, d*) PVPbMC3 films. The letters a, b, c and d represent the FESEM images at 1 kx magnification for the pure PVA and PVA composite films, while a*, b*, c*, and d* represent the FESEM images at 3 kx magnifications for the same films.

Study the band structure of films by UV–Vis spectroscopy

Absorption, transmittance, and absorption coefficient versus wavelength

The UV–Vis spectra exhibited a gradual alteration in absorbance and transmittance upon the addition of PbMC, resulting in the dispersion of the metal complex, which led to increased light absorption and decreased reflection, as shown in Fig. 5(a-b). The absorption bands suggest a decreased energy band gap between the π and π* bonding and antibonding molecular orbitals resulting from incorporating PbMC into the PVA matrix. The energy gap plays a crucial role in solar cells and optoelectronic fabrication, while polymeric composites are suitable for addressing optical limitations in photonic devices and laser stop power. The composite’s UV-Vis spectra exhibited a red shift (to high λ) in the optical Eg compared to pure polar PVA, dependent upon the filler concentration. Effective ultraviolet and visible spectra absorption indicate potential applications in filters and solar cells46. In the visible spectrum, pure PVA exhibits transparency. In composite samples, the absorption coefficient (α) values exhibit substantial variation at wavelengths ranging from 500 to 700 nm (visible domain). Additionally, an evident absorption band at λ = 673 nm suggests that the PVA/PbMC sample is suitable for application as a photocatalytic material and photovoltaic solar cell47, as illustrated in Fig. 5c. That clears the layer formed by intermolecular hydrogen interactions between the PVA matrix chains and the PbMC molecules. In the high wavelength range, the resulting films exhibit opacity. The optical absorption of light occurs in the visible wavelength band, resulting in strong electronegativity in PVA/PbMC samples48. The rise in electronegativity enhances the absorption of our samples49. Kirchoff’s law expresses the optical energy equilibrium, or the conservation of total energy, concerning the intensities of transmitted, absorbed, and reflected light, ignoring scattering effects. Using Eq. (2), we have plotted the rise of (α) versus (λ) as a function of sample thickness (d), which is shown in Fig. 5c. The absorption coefficient (α) dramatically reduces in pure PVA before the visible range, but in PVA/PbMC samples, it gradually decreases versus (λ)47,50.

Refractive index and dispersion characteristics

According to Snell’s law, in the visible range, the propagation of light through a substance results in a distortion of its velocity. This ratio varies with the speed of light and produces the optical constant known as the refractive index (N). This (N) represents a fingerprint of a polymeric substance. The value of (N) represents a complicated refractive index defined by14.

Where k is the coefficient of extinction, defined as \(\:(k=\frac{\alpha\:\lambda\:}{4\pi\:})\). The (k), denotes the attenuation of the electric field component of waves as they traverse through materials51. Figure 6a illustrates the refractive index of pure polymer PVA and different concentrations of metal complexes of PbMCs. The optical refractive index is derived from (R). This is the fundamental characteristic of the material, exhibiting dispersion across all wavelengths of light. The refractive index of an optical material signifies the electronic and molecular polarization of the electromagnetic (EM) field of light. These graphs illustrate the variation in the refractive index. The refractive index remains very low and stable across all samples at high wavelengths; however, it may increase with rising photon energy. Typically, an increase in doping concentration results in a corresponding rise in the refractive index. Subsequently, electronic and molecular polarization and dispersion are significantly elevated, but the wavelength is lower52.

Dispersion of the refractive index is a critical component in optical materials. It is a vital component in optical communication and the fabrication of devices for optical dispersion. The dispersion index of refraction in the typical dispersion zone has been examined utilizing the model of a single oscillator established by the Wemple and DiDomenico (WD) theory. A parameter known as dispersion-energy Ed was proposed, linking the coordination number to the charge distribution within each unit cell. Ed is closely connected to chemical bonding. They also established another parameter, the single-oscillator parameter Eo, which is related to the oscillator’s energy. The (n) at a given frequency can be expressed concerning the Ed and the Eo53.

Equation (5) indicates that the values of Ed and Eo can be derived from the slope and intercept of the linear region segment of the (n2 − 1)− 1 plot against (ℎv)², as illustrated in Fig. 6b. The WD model (Ed) quantifies the intensity of interband optical transitions. The charge and coordination number distribution in each unit cell of the material is involvedly connected to this characteristic. It is significantly linked to the nature of the material’s chemical bonding properties. Examining Ed enables researchers to gain significant insights into the material’s optical properties and the characteristics of its natural chemical bonding, thereby enhancing knowledge of its n dispersion within the standard spectral range. In this approach, the Eo value correlates with the (Eg); the Eo values were seen to be near the optical band gaps (Eo~Eg), and the single oscillator energy represents an average energy gap as shown in Schematic 4b, as noted in numerous publications54. The Seller or Cauchy formulations for (n) depend on the (λ), which are entirely mathematical fittings as indicated in Eq. 5b, where λo represents the average oscillator position, and So signifies the average oscillator strength55. The parameters can be obtained from the (n2-1)− 1 graph against λ−2, as depicted in Fig. 6c. The slope that provides a straight line corresponds to 1/So, and \(\:{\lambda\:}_{o}=\left(\frac{1}{\sqrt{{(S}_{o\:\times\:intercept}}}\right)\). The values of So and λo are documented in Table 4. The So value increased with the rising PbMC content in the composite films, whereas the λo value increased and shifted to the visible range. The interband transition strength moments M− 1 and M− 3 can be derived from the single-effective oscillator and dispersion energy utilizing Eq. (6)14. Table 4 presents the values of Eo, Ed, M− 1, and M− 3 for the existing composites.

Urbach energy tail study

The physical properties of the synthesized polymer will be predicted through Urbach energy, which correlates with the absorption coefficient (α) via the Urbach formula56.

Here, αo is a constant. Eu represents the Urbach energy tail, which explains the disorder inside the system by quantifying the breadth of the tail of localized energy states in the optical Eg. The feeling of mobility is subject to variations in the Eu for the doped polymer. The particle fillers create an extra defect state within the polymer matrix. Typically, a rise in defect concentration increases the density of localized states57. The relationship between (lnα) and incident photon energy (hv) is illustrated in Fig. 7. The values of Eu can be ascertained by the reciprocal of the slope, as presented in Table 4. It is noticeable that with a high PbMC dopant, the Eu rises. The increased level of Eu signifies a growth in the amorphous region and confirms the rise of trapped states within the optical energy band gap, which is affected by decreasing Eg.

Real ɛr and imaginary ɛi components of optical dielectric function (ODF)

The real and imaginary parts of ODF are important to study because they can be used to determine the density of localized states and relaxation time, respectively. Permittivity, often referred to as the dielectric constant, is a fundamental dielectric property that significantly influences material properties. This is associated with several properties, including polarizability, dielectric susceptibility, relaxation time, molecular radius, wave impedance, molar dispersity, specificity, and specific refraction. Using Maxwell’s equation for electromagnetic radiation (ε=n2), When written as58.

The complex dielectric constants ε*, and εr, εi represent the real and imaginary dielectric constants with components written as

The εr contributes to the dispersion and the density of states (DOS), whereas εi component quantifies the wave’s dissipative rate within the medium. ε∞ denotes the lattice zero dielectric constant or dielectric constant at the high frequency, N represents the concentration of the number of free charge carriers, m* indicates the effective mass of the electron charge carrier, εo signifies the free space permittivity (8.854 × 10− 12 F/m), and c refers to the vacuum speed of light. The additional characteristics obtained from the εi component of the dielectric include the time between two succussive collections is relaxation time (τ), plasma frequency (ωp), mobility (µopt), and resistivity (ρopt) related to optical parameters. The acquired values of εr are graphed as a function of λ2, as illustrated in Fig. 8a. The relationship between εr and λ2 is linear for extended wavelengths. Generalizing the linear segment of this relationship to zero λ (high frequency) yields the value of ε∞. From the slopes of the line regions, the values of density of states (N/m*) within the forbidden energy band gap for the examined samples were computed following the fundamental part of Eq. (9). The values of ε∞ and N/m* are presented in Table 5. The real and imaginary components exhibit a consistent pattern, with the values of the real component surpassing those of the imaginary component because it depends mainly on n259.

The structures identified in the optical spectra arise from transitions between occupied and unoccupied electronic energy levels. The examination of εi curves from Fig. 8b reveals the exponential zone. This range establishes the threshold for optical transitions between the HOMO and the LOMO bands. This is referred to as the important absorption edge. Beyond these points, the curves exhibit a plateau characteristic. The quantity of transitions from the VB to the CB influences the εi curve constant60. Both components of the dielectric constant (εr and εi) can be utilized to predict a composite’s overall optical band structure. The variation in the dielectric constant of the PVA composites may be employed in the design of optical communication devices. When a sample is exposed to incoming EM waves, its internal charges undergo a time-dependent force. In the domain of reduced incident energy, the sample’s polar molecules cannot track the field’s oscillation due to inertia. Figure 8b from the slope, it is easy to determine (τ) demonstrates that the PbMC in polar PVA results in an increase in ωp, µopt, and Nc due to the introduction of a greater (DOS) in the band gap region of the composite samples; nevertheless, ρopt decreases as optical conductivity rises61. Figure 8(a and b) clearly illustrates a significant asymmetry between pure polar PVA and composite PVA/PbMC in terms of εr and εi values across the spectral range; pure PVA displays in the high-frequency region, whereas the composite displays in the low-frequency region, attributable to the absorption edge and reduced band gap in PVA/PbMC. In general, the real and imaginary dielectric constants, εr and εi, are dynamic and crucial properties that characterize any material. Their values are essential for the fabrication of various optoelectronic devices, especially in selecting materials suitable for printed electronic circuit boards62.

Optical band gap study and types of electron transition

The Eg is a crucial parameter that identifies the device performance in solar cells, which is related to the conversion of sunlight into energy. In this section, various optical parameters and their derivatives have been utilized to estimate the Eg value. Upon absorption of sunlight, multiple types of electronic transitions may occur, depending on the material’s band alignment. In a crystalline material, it is essential to consider an infinite array of atomic potentials organized on an infinite periodic lattice to accurately identify and distinguish the energy levels in contrast to individual atoms or molecules63. This section employs many methods, including the first derivative of reflectance, absorbance, optical absorption coefficient, dielectric loss, loss tangent curves, and so on as functions of (λ)64.

Another complex quantity is the interband transition strength (J*), which is related algebraically to many optical parameters, including refractive index (n), permittivity (ε), and optical conductivity (σ* = σr + iσi). Furthermore, the Kramers–Kronig (KK) dispersion relations define the correlation between any optical property’s real and imaginary components. The J* is directly related to the interband transition probability and is measured in (g.cm− 3). For calculating simplicity, we set the pre-factor \(\:\left(\frac{4\pi\:{m}^{2}}{{e}^{2}{h}^{2}}\right)\) in Eq. (13), has a value (8.289 10− 6 g.cm− 3.eV− 2). Consequently, the (J) unit is (eV²). Figure 9(a and b) displays the J values of polar PVA and composites PVA/PbMC, as discovered from εr and εi. This parameter is crucial as it enables the identification of the energy range in which electrons absorb hv to transition from HOMO to LOMO, given the value of J65. The skin depth (δ) of polar PVA and composite films is a crucial characteristic linked to photon absorption by the films. δ is influenced by the energy of incident photons and the conductivity of films, where (δ = 1/α), with α being the absorption coefficient shown in Fig. 9c.

The absorption edge values for polar pure PVA doped with different concentrations of PbMC spectra are presented in Fig. 10a; Table 6. The collected and evaluated absorbance coefficient results demonstrate the significant effect of doping PVA with metal complexes. The incorporation of PbMC resulted in a decrease in the (α) values of the projected composite films at lower energy levels. Consequently, it also influenced the Eg values. The second method illustrated in Fig. 10b is the εi versus hv to determine Eg if the polar PVA and PVA/PbMC films. This optical dielectric is directly related to the index of refraction by Maxwell’s equation (ε=n2), and the index of refraction value also relates to the reduction in the Eg. These extensive results serve as the new optoelectronic applications19. The shift of the dielectric constant with photon energy suggests that some good interactions occur between polar polymer and PbMC. These interactions are evident in the imaginary components of the dielectric constant, leading to the creation of an exponential region in the dielectric spectra to determine Eg, which is contingent upon the type of material66. From Eq. (2), we may also choose the Eg of PVA with metal complexes by analyzing the first derivative of (A, α, and R) relative to the incident photon energy (hv)67. There is more agreement with the Eg results from the two previous methods. Figure 10(c, d, and e) illustrates that the minimum and maximum peak locations match the absorption band edge.

The complex optical conductivity (σ* = σr + iσi) is associated with the value (ε*), where \(\:\omega\:\) denotes the angular frequency, and ɛo represents the dielectric constant of free space.

Figure 10f illustrates (σopt) as a function of photon energy. The (σopt) rises with increased energy. The enhancement of optical conductivity results from electrons energized by photon energy. The optical conductivity of the complexes varies due to the coordinated formation of the complex. The optical conductivity does not exhibit any discernible trend concerning the atomic number of ions in the complexes. Furthermore, the (α) can be utilized to determine the optical conductivity68,69. Given the known σopt, one can readily determine the electrical conductivity (σe) as a function of photon energy, as shown in Fig. 10g, hv. Adding PbMC has significantly enhanced the dielectric constant and raised the σopt. The elevated σopt at high photon energies (or high frequency) results from the extensive light absorbance of sample films and may also be attributed to electrons activated by hv. After some mathematical modifications in Eq. (2), except (dA/dλ, and α) vs. hv, we also determine Eg from the curves of ln(A) against hv for polar PVA and PVA/PbMC samples as shown in Fig. 10h; Table 6. σe was identified as the predominant mechanism throughout the visible spectrum, significantly decreasing until the hv lower 1.5 eV. The σopt is predominant at photon energies over approximately 1.5 eV, suggesting that high-level doping may produce excitation, enhancing both wave and electron conduction in the visible spectrum70.

The study of solid structures and defects involves analyzing the dielectric loss tangent, which is computed using values of the dielectric constant. The dielectric parameter (tan δ), the dissipation factor, signifies the phase difference resulting from the energy dissipated by charge mobility in the EM field71. It is defined as the ratio of the εi component to the εr of the dielectric constant. Moreover, the quality factor (Q-factor) is the inverse of the (tan δ) and indicates the oscillation quality or vibrational resilience. Therefore, (tan δ) and (Q-factor) are defined as:

Figures 10i and j) illustrate the tan δ and Q-factor dependency on hv for polar PVA and composite PVA/PbMC films. The tan δ exhibits higher levels at high hv for all examined samples, correlating with increased metal complex concentration. At low hv values (~ 2 eV), the dissipation factor approaches zero, exhibiting a continuous dependency as illustrated in Fig. 10i. Conversely, as illustrated in Fig. 10j, the Q-factor of these composite films in the visible spectrum is almost zero. Furthermore, an increase in PbMC results in a reduction in the value Eg72.

The Mott and Davis model can clarify the reduction in Eg values by adding doping, which relates the extent of disorder and defects in an amorphous solid to the density of localized states (DOS) near a band gap. Incorporating additional electropositive or electronegative metal complexes is anticipated to raise the density of states (DOS)73. Higher amounts of these localized states have been demonstrated to reduce Eg values in unblemished PVA/PbMC structures. It confirms the rise of trapped states within the optical energy band gap, which is affected by the decrease in Eg and is illustrated in Schematic 4.

We determined the Eg from different methods with the approximate results from the preview sections. To evaluate these approaches in terms of sensitivity, the methods εi, Eedge, da/dλ, dα/dλ, and dR/dλ exhibit more sensitivity to determine Eg, but εi, Eedge easier but σop, σe, ln(A), and tan(δ) demonstrate a lesser degree of sensitivity, although Q-fac is noted. Method of minor to moderate strength. Hence, we determined the types of electron transition in the pure polar PVA and PVA/PbMC films; in one composite sample, one or two transitions might occur. The Eg value was caused by the transition states from the filled VBs to the CBs. Tauc’s equation can determine these types of transitions.

B is a constant, and γ is a practical value equal to a unique set; 1/2, 3/2, 2, and 3 signify the kind of electronic transition in the study films. These values define allowed and forbidden direct and indirect electron transitions. Furthermore, a novel equation was utilized to calculate the energy Eg values19. From Eqs. (2) and (19), we get another conjunction of Tauc’s equation called absorption spectrum fitting (ASF), and it is a function only on the (λ). This novel calculation depends on independent of film thickness. The (ASF) investigation was conducted following the subsequent relation Eg, determination by (ASF) method, and structural properties of different19,74.

Thus, the Eg, can be calculated from the λg parameter, and the value of λg can be calculated by generalizing the region of (A/λ)1/γ vs. (1/λ) curve at (A/λ)1/γ = 0. The optical Eg of values are shown in Table 7. The variation of (A/λ)1/γ vs. (1/λ) was plotted for the current samples, as shown in Fig. 11. The experimental result of the ASF is that the ASF obeys an equation similar to Eq. (19). The recognized Eg values with kind of transitions are presented in Table 7; Fig. 11. To identify the types of electron transitions, compare the ASF results with the εi results; the transition value in the ASF technique that closely aligns with the εi result indicates that this kind of transition occurs in this composite film, for instance, the (A/λ)2 in the ASF Eg value for the pure PVA (PVPbMC0) sample is comparable to the Eg value of εi, representing that a direct allowed transition occurs in pure polar PVA when exposed by light. The Eg results show the formation of defects in the composite samples. Furthermore, the reduced values were associated with charge transfer formation, attributed to the trap levels observed during the transition from HUMO to LUMO on the PVA/PbMC, lowering the energy necessary for electron transition. This explains that an increase in doping percentage increases localized states within the forbidden gap, reducing the Eg values26. The findings indicated a significant dispersion of the polar PVA doped with PbMC composite films. Prior reports on the Eg confirmed the suitability of the fabricated films for solar cell and optoelectronic applications19,75,76. Furthermore, the results of the current study can be compared to those reported in the literature, as presented in Table 8. The comparison establishes that green synthesized metal complexes are a novel methodology to modify the optical properties of PVA.

ASF plots between (A/λ)1/γ and (1/λ) for (a) direct allowed (A/λ)2, (b) direct forbidden (A/λ)2/3, (c) indirect allowed (A/λ)1/2, and (d) indirect forbidden (A/λ)1/3 electrons transition upon exposure to photons with hv energy, demonstrating behavior consistent with Tauc’s equation for polar PVA and composite PVA/PbMC films.

Study of the nonlinear optical characteristics of pure Polar PVA and pva/pbmc composite films

The nonlinear optical (NLO) characteristics of polymer composites are primarily determined by the composite’s composition and the attributes of the parent polymers. Nonlinear optics has numerous applications in photonics, telecommunications, capacity planning, and optical computing. PVA is extensively utilized in several nonlinear optical (NLO) application components. PVA doped with Pb metal complexes is predicted to exhibit elevated nonlinear constants. The linear optical susceptibility χ(1) (from Eo and Ed)of a nonlinear medium can be to drive 3rd susceptibility χ(3). The χ(3) magnitude is determined by exposing samples to high energy (hv) and inducing polarizability (P). The (P) at standard light intensity is a nonlinear function directly proportional to the electric field (E) raised to a high power, represented from the following in Ed and Eo or related to n49,83,84.

Figure 12b illustrates χ(3) results as a function of λ. The results indicate that doping PbMCs significantly enhanced the 3rd nonlinear optical susceptibility of the composite samples. For higher wavelengths (800–1100 nm), the susceptibility of composite films displays a plateau behavior, whereas pure PVA shows a plateau from 400 to 1100 nm; this may relate to the change in the degree of crystallinity49. Local structural modifications may affect the medium’s polarization, altering the 3rd susceptibility due to UV exposure85.

The characteristics of 3rd order susceptibility can be ascribed to the similar form of the nonlinear index of refraction n(2). n(2) can be estimated from the following with n(2), n(1) represented nonlinear and linear refractive indexes70. The two nonlinear n(2) and χ(3) parameters are derived by integrating Miller’s rule with parameters from the single oscillator WD model86.

The value of n2 was derived based on the Tichy and Ticha relationship, which combines Miller’s well-known rule and the static refractive index calculated using the WD model71. The optical linear/nonlinear parameters of (PVA) films are enhanced by doping with PbMC. In keeping with the results, significant attention has been directed towards the substance’s possible application in nonlinear optical (NLO) devices19, particularly in the manufacture of nonlinear data storage, optical switches, and directional connectors87. The (NLO) parameters are shown in Table 9. Another method for calculating n(2), by Fournier and Snitzer, is based on the linear index of refraction and WD parameters (Eo, Ed), as seen in the subsequent relation, where N is the density of polarizable residents, calculated by using two new parameters density and molar volume values71.

Tichý demonstrated that by employing Miller’s rule and the linear index of refraction (n), a straightforward relationship is proposed for estimating the χ(3) and the n(2). This relationship demonstrates a good agreement between the computed and experimental χ(3) and n(2) values for over 90 glassy oxides and 22 optical crystals, respectively88. The nonlinear refractive index can also be determined using the semi-empirical relation proposed by Tichy et al. \(\:\left[{n}^{\left(2\right)}\cong\:\frac{1.26\times\:{10}^{-9}}{{E}_{g}^{4}}\right]\), where B = 1.26 × 10−9 [esu (eV)4]. By substituting the value of Eg, we derive n(2) for both the PVA and PVA/PbMC films, as presented in Table 9, demonstrating strong concordance with existing literature85. The values of χ(1), χ(3), and n(2), derived from the experimental data extrapolated to zero wavelength, demonstrate conformity with the existing experimental results as shown in Fig. 12(a-c)89. Flexible optoelectronic devices, such as organic light-emitting diodes and solar cells, can benefit from doped PVA in the visible spectrum due to its linear and nonlinear optical characteristics90,91.

Optoelectronic parameters study

In addition, we investigated two parameters: the surface energy loss function (SELF) to clarify the optical transitions of electrons in the PVA/PbMC composite film. Another parameter is a volume energy loss function (VELF), which defines electron transitions within bulk materials at both high and low wavelengths. OR, in other words, the chance that fast electrons will dissipate energy while traversing the material and its surface is characterized as the VELF and the SELF. The two functions are associated with the εr and εi through the following relationships.

Figure 13(a and b) illustrates that the highest peaks for both VELF and SELF spectra of composite materials were shifted to lower photon energy, approximately 2.5 eV, compared to polar PVA at 5.75 eV. Interestingly, the values of VELF and SELF exhibited a significant increase, confirming the findings derived from the dielectric section on dielectric constants. Conversely, the volume energy loss function exceeds the surface energy loss function (VELF > SELF) for all input photon energies across all PbMC concentrations. Thus, the energy dissipation of free charge carriers moving through composite films exceeds that on the surface92, consequently, the excitation of plasma frequency in the bulk composite sheets exceeds that at the surface93. PVA/PbMC films and flexible substrates can be employed in various applications, such as nonlinear optics with a specified band gap, electrical devices, and flexible optoelectronics94 .

Study of kirchhoff’s functions and quality of samples by FOM

This section covers two significant characteristics influenced by λ or hv, which can be deduced from the observed optical parameters. The initial parameter is the optical surface resistance (Rs) as a function of λ. To compare the optical behavior and electrical behavior properties of polar PVA and doped PVA films, after we measured the transmittance in the previews section, we also showed the sheet resistance (Rs) for all samples, as shown in Fig. 14(a). The sheet resistance of the composite films decreased and shifted to a high wavelength (visible region) upon doping with PbMC. This improvement might be related to the transfer of electrons between polar PVA and PbMC, introducing a new bonding between polymer and metal complexes and decreasing hydrogen bonding between polymer chains. This suggests that our composite films possess a significantly enhanced electron concentration, as seen by a low sheet resistance95. On the other hand, (Rs) is inversely related to (T), showed in Fig. 5b. In general, pure PVA insulator has high Rs, but by incorporation with PbMC, the Rs decrease from 39 × 10− 7 to 2.9 × 10− 7 Ω/sq due to an increase in the (DOS) in the Eg of composite films96. And the Rs inversely proportional to n

The second parameter is thermal emissivity εth; the thermal emission rate from the film’s surface correlates with the rate of light beams incident upon its interface. The temperature, the observation direction, and the surface properties of the substance determine thermal emission. The film’s sheet resistance, Rs, and the εth produced by electron excitation from incident photons on the film’s surface denote these qualities. The Rs and εth are two critical functions that must be discovered to understand their correlation with the refractive index and transmittance of the examined films. The two elements are designated as the surface functions (Kirchhoff’s functions), derived from Eqs. (29) and (30). As the wavelength grows, Kirchhoff’s functions rise, but they diminish with an increase in the film’s thickness. The behavior of these functions is inversely correlated with the linear refractive index67. Consequently, the thermal emission can be characterized as variable. Figure 14(a and b) illustrates that sheet resistance and thermal emissivity rise with increasing wavelength. Conversely, similar numbers rise with heightened doping levels. This behavior is associated with the transmittance, absorption coefficient, and light refraction angle within the films97,98.

This research proposes utilizing a figure-of-merit diagram characterized by the Haacke equation, illustrated in Fig. 14c, to determine the composition of the PVA/PbMC composite for flexible optoelectronic devices, targeting specific requirements for optical transmittance, sheet resistance, and cost. This graphic examines the relationship between optical transmittance, sheet resistance, film thickness, and PbMC concentration99. Consequently, this figure-of-merit diagram is generated using the established optimized by the wavelength in Fig. 14c100. Haacke proposed utilizing the figure of merit, which indicates a balance between T and Rs. He demonstrated that in specific, well-defined situations, \(\:{\varvec{\phi\:}}_{\varvec{f}\varvec{i}\varvec{l}\varvec{m}}\) can be derived from fundamental material parameters; however, a higher \(\:{\varvec{\phi\:}}_{\varvec{f}\varvec{i}\varvec{l}\varvec{m}}\:\)generally signifies better quality. This approach highlights the significance of optical transparency, as sheet resistance can fluctuate over a broader spectrum for a film to qualify as an effective, transparent conducting material101.

The value of \(\:{\varvec{\phi\:}}_{\varvec{f}\varvec{i}\varvec{l}\varvec{m}}\) initially increases with rising PbMC content and shifts to a higher wavelength. Additionally, the merit figure for polar PVA has three peaks at 229, 277, and 325 nm, achieving a maximum value of (12 × 105 Ω/sq). Nonetheless, composite films have a unique peak at an intensity of approximately (14 × 105 Ω/sq). While sheet resistance decreases with rising PbMCs, the heightened concentration is justifiable. This results in enhanced optical absorption, as evidenced by a decrease in optical transmittance, which decreases from 0.95 to 0.78, as illustrated in Fig. 5b. A higher \(\:{{\upphi\:}}_{\text{f}\text{i}\text{l}\text{m}}\) correlates with improved quality in transparent conductive films. The left hand side of the peak of the \(\:{{\upphi\:}}_{\text{f}\text{i}\text{l}\text{m}}\) spectra are those photons that have sufficient energy to transfer the electron from the VB to the CB, while the right hand side of the \(\:{{\upphi\:}}_{\text{f}\text{i}\text{l}\text{m}}\) spectra show the photons which their energy are not adequate to boost the electrons to cross the optical band gap of the host material. Low-Eg films indicate that PVA combined with PbMCs can achieve a superior balance between transmission and sheet resistance, exhibiting superior optical and electrical properties. These results indicated a good interaction between polar PVA and metal complex PbMCs. We can also determine the Eg of pure PVA and composite films from the maximum wavelengths from the figure of merit, and this figure indicates the quality of composite films to show that the electrons in LOMO have enough energy to reach HOMO96. It is a significant known figure of merit because it relates to optical properties (transmittance T) and electrical properties (sheet resistance Rs).

This study studied the structural and optical properties of the PVA/PbMC composite. The modification in the structures of composite films of polar PVA, changing from a semi-crystalline phase to an amorphous phase, enhances optical conduction mainly due to the transfer of electrons from a low energy (HOMO) state to a high energy state (LOMO) when electrons absorb sufficient energy in composite samples, potentially rising localized states. The FTIR analysis of the GT and Pb(CH3COO)2 functional groups was carried out following the synthesis of PbMC. The alteration in the broadening and shift to low frequency seen in the IR characterizations of PVA/PbMC films was associated with a good interaction between PVA and PbMC. Utilizing UV-Vi’s spectroscopy, we assessed various optical parameters, including the linear and nonlinear indices of refraction, dielectric function, relaxation time, dispersive energy, optical energy band gap, linear and nonlinear susceptibility, sheet resistance, thermal emissivity, and merit figure of polar PVA and PVA/PbMC films across a wide spectral range from 190 to 1100 nm. Data indicate a significant enhancement of PVA following doping with PbMC. To compare our study with previous works, we have created a table that explains the impact of metal complex synthesized using the green technique on the band structure of the polar PVA matrix.

Conclusions

Facile synthesized composite films were produced based on polar PVA doped with Pb metal complexes via the casting technique. XRD of the composite samples shows an increasing degree of disorder. This disorder is due to the good dispersal of PbMC in the polymer matrix, and its attributes might be due to reduced hydrogen H bonding in polar PVA and good H bonding produced between the OH group of PVA and PbMC. The FTIR study verifies the synthesis of PbMC, as indicated by the absence of 2CH3COO in the lead metal complex and the coordination formed between Pb2+ and polyphenols, rather than acetate. FT-IR spectrum analysis of pure PVA and composite PVA films confirmed the shifts in the locations of specific functional groups to lower frequencies and alterations in transition intensity resulting from the presence of the dopant PbMC in the polymer. From FESEM, the aggregated particles of the composite samples exhibited no cracks or agglomerations and were denser and more compact compared to those of the pure PVA matrix. The main focus of this study is on the reduced optical energy band gap, which can be computed using ten distinct methodologies with the same outcome. The Eg decreases significantly from 6.17 to 1.56 eV due to the constructive interaction between OH and PbMC functional groups. Furthermore, incorporating Tauc’s equation for determining the type of electron transitions, this alteration might come from an increase in Urbach tail energy from 0.28 to 0.65 eV. From the WD single oscillator model, we derive several parameters. Ed, Eo, and no, Eo represents the average energy band gap of polar PVA and PVA/PbMC composite films, which reduces from 5.75 eV to 2.07 eV, so supporting the reduction of Eg. Reducing Eg may enhance light absorption, the refractive index, the average oscillator position λo, and the average oscillator strength So. The interband transition intensity moments M− 1 and M− 3 can be obtained from the single Ed, Eo effective oscillator of the WD model. Furthermore, the Kramers–Kronig (KK) dispersion relations delineate the relationship between any optical property’s real and imaginary components interband transition strength (J*). The J value indicates notable absorption occurs by electrons after at photon energies hv of 5.5 eV and 1.5 eV for polar PVA and PVA/PbMC composite films, respectively. The additional parameters enhanced from the real and imaginary components of the dielectric constant include the density of state (N/m*), relaxation time (τ), plasma frequency (ωp), optical mobility (µopt), and optical resistivity (ρopt) by PbMC doping. The nonlinear parameters 3rd order susceptibility, χ(3), and the index of refraction n(2) were computed using Miller’s formula, with their values influenced by doping. Finally, we interconnect the optical and electrical parameters from sheet resistance Rs and the figure of merit FOM. These enhancements of optical parameters might also be useful in optical communications, stopping laser power, designing dispersion devices, optical waveguides, solar cells, and optoelectronic devices.

Data availability

Data will be available from the corresponding author upon request.

References

Mahmoudi, G., Seth, S. K., Riera, A. B., Zubkov, F. I. & Frontera, A. Novel Pb(II) complexes: X-ray structures, Hirshfeld surface analysis and DFT calculations. Cryst. (Basel). 10, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst10070568 (2020).

Shooto, N. D. et al. Fabrication, evaluation and adsorption of lead ions from aqueous solution. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 2016;11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s11671-016-1631-2

Santos, T. J. et al. Computational study of the interaction of heavy metal ions, Cd(II), Hg(II), and Pb(II) on lignin matrices. J. Mol. Graph Model. 111, 108080. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmgm.2021.108080 (2022).

Pan, X., Niu, G. & Liu, H. Microwave-assisted extraction of tea polyphenols and tea caffeine from green tea leaves. Chem. Eng. Process. 42, 129–133. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0255-2701(02)00037-5 (2003).

Lee, M. J. et al. Delivery of tea polyphenols to the oral cavity by green tea leaves and black tea extract. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 13, 132–137. https://doi.org/10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-03-0040 (2004).

Pasrija, D. & Anandharamakrishnan, C. Techniques for extraction of green tea polyphenols: A review. Food Bioproc Tech. 8, 935–950. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11947-015-1479-y (2015).

Perron, N. R. & Brumaghim, J. L. A review of the antioxidant mechanisms of polyphenol compounds related to iron binding. Cell. Biochem. Biophys. 53, 75–100. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12013-009-9043-x (2009).

Lakey-Beitia, J., Burillo, A. M., La Penna, G., Hegde, M. L. & Rao, K. S. Polyphenols as potential metal chelation compounds against alzheimer’s disease. J. Alzheimer’s Disease. 82, S335–S357. https://doi.org/10.3233/JAD-200185 (2021).

Navarro, R. E., Santacruz, H. & Inoue, M. Complexation of Epigallocatechin gallate (a green tea extract, egcg) with Mn 2+: nuclear spin relaxation by the paramagnetic ion. J. Inorg. Biochem. 99, 584–588. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2004.11.013 (2005).

Su, Y. et al. Ferric ions modified Polyvinyl alcohol for enhanced molecular structure and mechanical performance. Materials 13, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma13061412 (2020).

Nagarkar, R. & Patel, J. Acta scientific pharmaceutical sciences. Polyvinyl Alcohol: Compr. Study. 3, 2581–5423 (2019).

Bhargav, P. B., Mohan, V. M., Sharma, A. K. & Rao, V. V. R. N. Investigations on electrical properties of (PVA:NaF) polymer electrolytes for electrochemical cell applications. Curr. Appl. Phys. 9, 165–171. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cap.2008.01.006 (2009).

Polu, A. R. & Kumar, R. Preparation and characterization of Pva based solid polymer electrolytes for electrochemical cell applications. Chin. J. Polym. Sci. (English Edition). 31, 641–648. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10118-013-1246-3 (2013).

Alias Zabidi, A. M. et al. Optical Characterization and Properties of Polymeric Materials for Optoelectronic and Photonic M. K. Harun Faculty of Applied Sciences, Universiti Teknologi MARA 40450 Shah Alam, Selangor D. E. Int J Appl Sci Technol ;3:11–38. (2013).

Bhargav, P. B., Mohan, V. M., Sharma, A. K. & Rao, V. V. R. N. Structural, electrical and optical characterization of pure and doped Poly (vinyl alcohol) (PVA) Polymer electrolyte films. Int. J. Polym. Mater. Polym. Biomaterials. 56, 579–591. https://doi.org/10.1080/00914030600972790 (2007).

Krishnakumar, V. & Shanmugam, G. Electrical and optical properties of pure and Pb 2 + ion doped PVA - PEG polymer composite electrolyte films. Ionics (Kiel). 18, 403–411. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11581-011-0643-2 (2012).

Arulmozhi, K. T. & Mythili, N. Studies on the chemical synthesis and characterization of lead oxide nanoparticles with different organic capping agents. AIP Adv. 3 https://doi.org/10.1063/1.4858419 (2013).

Donya, H., Taha, T. A., Alruwaili, A., Tomsah, I. B. I. & Ibrahim, M. Micro-structure and optical spectroscopy of pva/iron oxide polymer nanocomposites. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 9, 9189–9194. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmrt.2020.06.040 (2020).

Zyoud, S. H. et al. Structural, optical, and electrical investigations of Nd2O3-Doped PVA/PVP polymeric composites for electronic and optoelectronic applications. Polym. (Basel). 15. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym15061351 (2023).

Batool, A. & Saleh, T. A. Removal of toxic metals from wastewater in constructed wetlands as a green technology; catalyst role of substrates and chelators. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 189, 109924. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoenv.2019.109924 (2020).

Vraspir, J. M. & Butler, A. Chemistry of marine ligands and siderophores. Ann. Rev. Mar. Sci. 1, 43–63. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.marine.010908.163712 (2009).

Heiba, Z. K., El-Naggar, A. M., Kamal, A. M., Lakshminarayana, G. & Mohamed, M. B. Optical, structural, and dielectric characteristics of flexible PVA/PEG/ZnMn2O4/CuCo2O4/x wt % Melanin blended polymer composites. J. Macromolecular Sci. Part. B: Phys. 64, 641–662. https://doi.org/10.1080/00222348.2024.2362532 (2024).

Li, J., Lee, K. & Gopalan, A. I. One-Step Preparation of nickel Nanoparticle-Based magnetic Poly (Vinyl Alcohol) gels 2019.

Popescu, M. C., Dogaru, B. I., Goanta, M. & Timpu, D. Structural and morphological evaluation of CNC reinforced pva/starch biodegradable films. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 116, 385–393. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2018.05.036 (2018).

Soliman, T. S., Vshivkov, S. A. & Elkalashy, S. I. Structural, linear and nonlinear optical properties of Ni nanoparticles – Polyvinyl alcohol nanocomposite films for optoelectronic applications. Opt. Mater. (Amst). 107, 110037. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.optmat.2020.110037 (2020).

Elhosiny Ali, H. & Khairy, Y. Microstructure and optical properties of Ni2 + doped PVA for optoelectronic devices. Phys. B Condens. Matter. 570, 41–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physb.2019.05.050 (2019).

Patel, M. H., Chaudhuri, T. K., Shripathi, T., Deshpande, U. & Patel, V. K. Influence of pb + 2-thiourea complex concentration on the structural, optical, thermal and electrical properties of pbs/pvp-pva nanocomposite films. J. Polym. Res. 25, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10965-017-1402-5 (2018).

Heiba, Z. K., Mohamed, M. B. & Badawi, A. Impact of nano CoFe1.75Er0.25O4 loading ratios on the dielectric and radiation shielding properties of Polyvinyl chloride polymer. J. Macromolecular Sci. Part. B: Phys. 64, 747–762. https://doi.org/10.1080/00222348.2025.2452022 (2025).

Hema, M. et al. XRD and ac impedance spectroscopic study on PVA based polymer electrolyte doped with NH4X (X = Cl, br, I). J. Non Cryst. Solids. 355, 84–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnoncrysol.2008.10.009 (2009).

Tangboriboon, N., Pakdeewanishsukho, K., Jamieson, A., Sirivat, A. & Wongkasemjit, S. Electrical properties of a novel lead alkoxide precursor: lead glycolate. Mater. Chem. Phys. 98, 138–143. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matchemphys.2005.09.034 (2006).

Zhang, Z. et al. Enhanced efficiency and stability of Sky blue perovskite Light-Emitting diodes via introducing lead acetate. Molecules 29, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules29112425 (2024).

Salih, A. A., Abad, W. K., Fadaam, S. A. & Hussein, B. H. Fabrication of lead oxide nanoparticles by green synthesis method for photovoltaic applications. Dig. J. Nanomater Biostruct. 18, 1225–1233. https://doi.org/10.15251/DJNB.2023.184.1225 (2023).

Senthilkumar, S. R., Thirumal, S., Arulmozhi, K. T. & Mythili, N. FT-IR analysis and correlation studies on the antioxidant activity, total phenolics and total flavonoids of Indian commercial teas (Camellia sinensis L.) - A novel approach. Int. Res. J. Biol. Sci. 6, 1–7 (2018).

Li, X. et al. Rapid determination of chlorophyll and pheophytin in green tea using fourier transform infrared spectroscopy. Molecules 23 https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules23051010 (2018).

Farag, O. F., El-Sayed, A. S. A. & AbdelFattah, E. M. One step synthesis of ag nanoparticles incorporated PVA nanocomposite via plasma reduction route. Sci. Rep. 15, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-03700-6 (2025).

Dana, S. & Muhammad1, Dara, M. Aziz2 SBA. The impact of green chemistry to synthesize pva/cobalt metal complexes (CoMCs) composites with enhanced optical behavior. Opt. Mater. (Amst) 2024:100201. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.optmat.2024.116448

Soliman, A. M. et al. Removal of Pb(II) ions from aqueous solutions by sulphuric acid-treated palm tree leaves. J. Taiwan. Inst. Chem. Eng. 58, 264–273. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtice.2015.05.035 (2016).

Arulmozhi, K. T. & Mythili, N. Studies on the chemical synthesis and characterization of lead oxide nanoparticles with different organic capping agents. AIP Adv. 3, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.4858419 (2013).

Santos, A. M. N. et al. Physically cross-linked gels of PVA with natural polymers as matrices for Manuka honey release in wound-care applications. Materials 2019;12. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma12040559

Aziza, S., Attia, S., Gelfer, S. & Paz Tal, O. Heavy metal ions incorporated within strippable PVA-TTA polymeric matrix detected by colorimetry and vibrational spectroscopies. Results Mater. 18, 100399. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rinma.2023.100399 (2023).

Abdel-Kader, M. H., Mohamed, M. B., Alharby, T. & Ibrahim, R. M. UV-Irradiation effects on the structural, optical and electrical characteristics of soft blended polymeric materials loaded with Multi-Walled carbon nanotubes (MWCNTs). J. Macromolecular Sci. Part. B: Phys. 64, 531–554. https://doi.org/10.1080/00222348.2024.2357916 (2025).

Shah, S. A. et al. Effect of carbon nanotubes and zinc oxide on electrical and mechanical properties of Polyvinyl alcohol matrix composite by electrospinning method. Sci. Rep. 14, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-79477-x (2024).

Mollá, S. & Compañ, V. Polyvinyl alcohol nanofiber reinforced Nafion membranes for fuel cell applications. J. Memb. Sci. 372, 191–200. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.memsci.2011.02.001 (2011).

Marf, A. S., Abdullah, R. M. & Aziz, S. B. Structural, morphological, electrical and electrochemical properties of PVA: CS-based proton-conducting polymer blend electrolytes. Membr. (Basel). 10. https://doi.org/10.3390/membranes10040071 (2020).

Brza, M. A., Aziz, S. B., Anuar, H. & Ali, F. Structural, ion transport parameter and electrochemical properties of plasticized polymer composite electrolyte based on PVA: A novel approach to fabricate high performance EDLC devices. Polym. Test. 91, 106813. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.POLYMERTESTING.2020.106813 (2020).

Bulinski, M. Metal doped PVA films for opto-electronics-optical and electronic properties, an overview. Molecules 26 https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules26102886 (2021).

Rejaiba, O. et al. Investigation study of optical and dielectric parameters using absorption and diffuse reflectance spectroscopy method on La0.57Nd0.1Sr0.13Ag0.2 MnO3 perovskite for optoelectronic application. 54. (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11082-022-03633-8

Alanazi, T. I., Alenazi, R. A. & El Sayed, A. M. Tuning the band gap, optical, mechanical, and electrical features of a bio-blend by Cr2O3/V2O5 nanofillers for optoelectronics and energy applications. Sci. Rep. 14, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-62643-6 (2024).

El-Zaidia, E. F. M., Ali, H. A. M., Hamdalla, T. A., Darwish, A. A. A. & Hanafy, T. A. Optical linearity and bandgap analysis of erythrosine B doped in Polyvinyl alcohol films. Opt. Mater. (Amst). 100. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.optmat.2020.109661 (2020).

Muhammed, D. S. et al. Optical dielectric loss as a novel approach to specify the types of electron transition: XRD and UV-vis as a non-destructive techniques for structural and optical characterization of Peo based nanocomposites. Materials 13, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma13132979 (2020).

El-naggar, A. M. et al. Effect of tetrapropylammonium iodide doping amounts on the structural, electric and optical characteristics of the PVA/PVP. J. Macromolecular Sci. Part. B: Phys. 63, 75–94. https://doi.org/10.1080/00222348.2023.2253516 (2024).

Gnana Kiran, M., Krishna Jyothi, N., Samatha, K., Rao, M. P. & Prasad, V. B. V. N. Studies on optical properties of Pva based complex polymer electrolyte. Rasayan J. Chem. 14, 760–767. https://doi.org/10.31788/RJC.2021.1425964 (2021).

Ghanipour, M. & Dorranian, D. Effect of Ag-Nanoparticles doped in Polyvinyl alcohol on the structural and optical properties of PVA films. J. Nanomater. 2013 https://doi.org/10.1155/2013/897043 (2013).

Aziz, D. M. et al. Spectroscopic study of wemple-didomenico empirical formula and Taucs model to determine the optical band gap of dye-doped polymer based on chitosan: common poppy dye as a novel approach to reduce the optical band gap of biopolymer. Spectrochim Acta Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 325, 125142. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.saa.2024.125142 (2025).

Habubi, N. F. et al. Dispersion parameters of Polyvinyl alcohol films doped with Fe. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2018;1003. https://doi.org/10.1088/1742-6596/1003/1/012094

Alghamdi, H. M. & Rajeh, A. Synthesis and improved optical, electrical, and dielectric properties of PEO/PVA/CuCo2O4 nanocomposites. Sci. Rep. 14, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-69982-4 (2024).

Algarni, M. M. Ali1 I.S. Yahia1 3. The structure analysis and optical performance of PVA films doped with Fe3+-metal for UV- limiter, and optoelectronics. Materials Research Express 15459124171 on 09/06/2019 at 22:26 :0–14. (2019). https://doi.org/10.1088/2053-1591/ab2668

Mamand, D. M. et al. Optical band gap modulation in functionalized Chitosan biopolymer hybrids using absorption and derivative spectrum fitting methods: A spectroscopic analysis. Sci. Rep. 15, 3162. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-87353-5 (2025).

Abdel-Aziz, M. M., Yahia, I. S., Wahab, L. A., Fadel, M. & Afifi, M. A. Determination and analysis of dispersive optical constant of TiO 2 and Ti 2 O 3 thin films. Appl. Surf. Sci. 252, 8163–8170. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsusc.2005.10.040 (2006).

Sakhya, A. P., Dutta, A., Shannigrahi, S. & Sinha, T. Electronic structure, optical dielectric constant and born effective charge of EuAlO3. J. Phys. Chem. Solids. 88, 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpcs.2015.09.004 (2016).

Aslam, M., Kalyar, M. A. & Raza, Z. A. Fabrication of nano-CuO-loaded PVA composite films with enhanced optomechanical properties. Polym. Bull. 78, 1551–1571. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00289-020-03173-9 (2021).

Heiba, Z. K., El-naggar, A. M., Kamal, A. M., Aldhafiri, A. M. & Mohamed, M. B. Influence of polyaniline on the structural, linear/nonlinear optical, and dielectric characteristics of Poly(Vinyl Chloride/Poly (Ethylene Oxide) Blends. J. Macromolecular Sci. Part. B: Phys. 63, 343–360. https://doi.org/10.1080/00222348.2023.2270269 (2024).

Sangiorgi, N., Aversa, L., Tatti, R., Verucchi, R. & Sanson, A. Spectrophotometric method for optical band gap and electronic transitions determination of semiconductor materials. Opt. Mater. (Amst). 64, 18–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.optmat.2016.11.014 (2017).

Mamand, D. M. et al. Enhanced optical properties of Chitosan polymer doped with orange Peel dye investigated via UV-Vis and FTIR analysis. Sci. Rep. 15, 3232. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-87425-6 (2025).

French, R. H. Origins and applications of London dispersion forces and Hamaker constants in ceramics. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 83, 2117–2146. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1151-2916.2000.tb01527.x (2000).

Badran, H. A., Al-Mudhaffer, M. F., Hassan, Q. M. A. & Al-Ahmad, A. Y. Study of the linear optical properties and surface energy loss of 5’,5-dibromo-o-cresolsulfophthalein thin films. Chalcogenide Lett. 9, 483–493 (2012).

Qasem, A., Mostafa, M. S., Yakout, H. A., Mahmoud, M. & Shaaban, E. R. Determination of optical bandgap energy and optical characteristics of Cd30Se50S20 thin film at various thicknesses. Opt. Laser Technol. 148, 107770. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.optlastec.2021.107770 (2022).

Ghanipour, M. & Dorranian, D. Effect of Ag-nanoparticles doped in Polyvinyl alcohol on the structural and optical properties of PVA films. J. Nanomaterials. 2013 (897043), 1–10 (2013). n.d.

Rashidian, M. & Dorranian, D. Low-intensity UV effects on optical constants of PMMA film. J. Theoretical Appl. Phys. 8 https://doi.org/10.1007/s40094-014-0121-0 (2014).

Boulahlib, S., Dib, K., Özacar, M. & Bessekhouad, Y. Optical, dielectric, and transport properties of Ag-doped ZnO prepared by Aloe Vera assisted method. Opt. Mater. (Amst). 113. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.optmat.2021.110889 (2021).

Abbady, G., Qasem, A. & Abd-Elnaiem, A. M. Optical parameters and electronic properties for the transition of the amorphous-crystalline phase in Ge20Te80 thin films. J. Alloys Compd. 842, 155705. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jallcom.2020.155705 (2020).

Hassanien, A. S. & Sharma, I. Dielectric properties, optoelectrical parameters and electronic polarizability of thermally evaporated a-Pb-Se-Ge thin films. Phys. B Condens. Matter. 622, 413330. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physb.2021.413330 (2021).

Muiva, C. M., Mwabora, J. M., Sathiaraj, T. S. & King, J. G. Optical properties of amorphous Se90-XIn10SbXthin film alloys. J. Alloys Compd. 689, 432–438. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jallcom.2016.07.299 (2016).

Souri, D. & Shomalian, K. Band gap determination by absorption spectrum fitting method (ASF) and structural properties of different compositions of (60-x) V2O5-40TeO2-xSb2O3 glasses. J. Non Cryst. Solids. 355, 1597–1601. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnoncrysol.2009.06.003 (2009).

, E. N. MH,, E. M. AM,, T. BM &, M. A. H. M Fabrication and characterization of Eco-Friendly thin films as potential optical absorbers for efficient Multi-Functional Opto-(Electronic) and solar cell applications. Materials 16 https://doi.org/10.3390/ma16093475 (2023).

Muhammad, D. S., Aziz, D. M. & Aziz, S. B. Zinc metal complexes synthesized by a green method as a new approach to alter the structural and optical characteristics of PVA: new field for polymer composite fabrication with controlled optical band gap. RSC Adv. 14, 26362–26387. https://doi.org/10.1039/d4ra04228j (2024).