Abstract

Counties represent a crucial spatial unit for achieving integrated urban-rural development and coordinated regional development. Promoting new urbanization(NU) at the county level in special-type regions such as revolutionary old base areas is an important pathway to realizing this goal. From the perspective of the Main Functional Zoning framework, this study selects 617 counties across 12 revolutionary old base areas in China as research units. An evaluation index system for new urbanization is constructed, and methods such as the Dagum Gini coefficient and geodetector are employed to reveal the spatial patterns and dynamic changes in county-level new urbanization from 2010 to 2020, as well as to explore the main influencing factors behind its spatial differentiation.The results indicate: (1) From 2010 to 2020, the level of new urbanization in county areas of revolutionary old base areas continued to rise, with an average annual growth rate of 8.59%. Counties with high urbanization levels were mainly concentrated in the Taihang Revolutionary Old Base Area, the Yimeng Revolutionary Old Base Area, and the Hailufeng Revolutionary Old Base Area. Additionally, urban districts and county-level cities with better development foundations also exhibited relatively higher urbanization indices.(2)From the perspective of Main Functional Zones, in both 2010 and 2020, the level of new urbanization followed the order key development zones > major grain-producing areas > key ecological function zones. However, the growth rate showed the opposite trend. The relative disparities between different Main Functional Zones have narrowed over time.(3) Natural conditions, human capital, socio-economic factors, policy support, and locational factors jointly shape the spatial pattern of new urbanization in revolutionary old base areas. Among these, socio-economic factors—represented by indicators such as rural residents’ disposable income and per capita GDP—as well as human capital, play a dominant role, with significant differences observed across various Main Functional Zones.This study offers theoretical insights and policy implications for promoting differentiated and distinctive new urbanization pathways in county areas of revolutionary old base regions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Since the reform and opening up, with the rapid development of the economy and society, China’s level of urbanization has continuously increased. By the end of 2023, the urbanization rate of the resident population had reached 66.16%, indicating that China has entered the middle-to-late stages of urbanization.1 In 2022, the General Office of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China and the General Office of the State Council issued the “Opinions on Promoting Urbanization Construction with Counties as Important Carriers,” emphasizing that counties are key supports for the integration of urban and rural areas, and play a significant role in promoting NU and building a new type of industrial-agricultural and urban-rural relationship.2 However, from a regional perspective, the level of urbanization in central and western China still lags behind that of the eastern region. The urbanization level in underdeveloped areas, particularly revolutionary old areas, is far behind the national average, making these regions the focus and challenge for achieving high-quality NU.3,4 Revolutionary old areas, due to their location at the intersection of multiple provinces, lie in transitional regions across different urban agglomerations, have the potential for NU.5,6,7 The implementation of a series of revitalization policies, such as the “Opinions of the State Council on Supporting the Revitalization and Development of Revolutionary Old Areas in the New Era,” has provided external opportunities for the NU construction in revolutionary old areas.8,9 In this context, in-depth research on the spatiotemporal evolution and driving mechanisms of NU in revolutionary old areas is of great significance for promoting high-quality revitalization and coordinated development of urban and rural areas.

Since the Chinese government first proposed NU strategy in 2013, scholars at home and abroad have made substantial achievements in the connotation of urbanization10 indicator systems11 spatial patterns12 and influencing factors.13 Early views on urbanization focused on the transfer of agricultural populations to non-agricultural industries and urban areas, emphasizing the continuous increase in urban population and the expansion of urban built space.14 On one hand, the continuous advancement of urbanization has led to economic growth and steady improvement in people’s livelihoods, injecting strong internal momentum into the modernization of China.15 On the other hand, excessive pursuit of population and spatial urbanization has also led to issues such as deteriorating living environments, low spatial utilization efficiency, and urban-rural dualism.16 To address these issues, the Chinese government and academia have timely proposed the concept of NU. Fang Chuanglin believes that high-quality development in NU consists of five dimensions: harmony between people and land, efficiency and low carbon, ecological protection, innovation and conservation, and smart and safe development.10 Additionally, scholars have further expanded the connotation of NU from perspectives such as people-oriented, green and environmental protection, and shared prosperity.17,18 Overall, scholars have explained the connotation of NU from multiple dimensions and perspectives, emphasizing people-oriented NU and the integration of urban and rural areas.

Consistent with the development of the connotation of urbanization, the evaluation indicator system has evolved from a single indicator to a multi-dimensional one, continuously incorporating indicators with contemporary characteristics. Specifically, the early urbanization indicators focused on population urbanization, with the urbanization rate being the core indicator for assessing the level of urbanization.3,19 With the proposal of the concept of NU, scholars have constructed a multi-dimensional evaluation indicator system from perspectives such as high-quality development, people-oriented, ecological civilization, and regional characteristics.20 For example, Ou Jinfeng and other scholars constructed a high-quality development evaluation indicator system for NU from five dimensions: economic development, infrastructure, urban-rural integration, green and low carbon, and innovation.21 Additionally, some scholars have added urban-rural integration indicators to reflect the interactive and integrated relationship between NU and rural revitalization in the new era.22 Overall, the evaluation systems constructed by scholars are diverse, and the selected indicators vary, but they all cover economic, social, and environmental dimensions to ensure that the indicator system can comprehensively measure the level of NU.23,24,25,26

In empirical research, the spatial patterns and driving factors of NU at different regions and spatial scales are hot topics. Scholars have analyzed the spatial patterns of NU at the national, basin, and city cluster levels using provinces27,28,29 cities30,31,32 and other basic units.33,34,35,36,37 Additionally, some scholars have divided the counties across the country into three types from a circle perspective: counties radiated by large metropolitan areas, counties with potential in city clusters, and counties in the gaps of city clusters, to evaluate the spatial patterns of county-level urbanization at the national scale.38 However, this approach has neglected the comprehensive impact of natural environment and socio-economic factors. As an important territorial spatial planning program, the Main Functional Zoning scheme classifies counties into four main functional types based on regional resource and environmental carrying capacity, as well as taking into account current development status and future potential. Through the implementation of differentiated spatial policies, it aims to achieve high-quality coordinated development of the economic, social, and environmental systems. Due to significant differences in socioeconomic foundations and future development potential among various main functional zones, the Main Functional Zoning plan will reinforce these disparities, exerting certain impacts on population and industrial agglomeration, ecological conservation, and other aspects, thereby leading to spatial variations in the pattern of NU39 however, few studies have explored the spatial differentiation and influencing factors of new urbanization from this perspective.

Influenced by a combination of factors including natural environment, socio-economic development stages, policies, and locational conditions, the factors affecting urbanization development levels and their driving mechanisms exhibit significant diversity, complexity, and regional differences.24 Scholars have utilized various methods such as correlation analysis, obstacle degree models, multiple regression models, geographical detector methods, and spatial econometric models to select factors like natural environment, socio-economic conditions, location, and policy support.12,21,24,28,29 These methods aim to reveal the intrinsic mechanisms and external driving forces behind the spatial patterns of urbanization. Results indicate that natural factors play a fundamental role in the quality of regional urbanization, characterized by stability and long-term effects. Meanwhile, economic development levels, industrial structures, human capital, and geographic locations significantly impact the urbanization patterns of regions and show clear spatiotemporal variations.12,24,40

In summary, research on new urbanization is still in the exploratory stage and has the following shortcomings: From the perspective of research subjects, existing studies mostly focus on the entire country or key economic regions. However, as new urbanization enters its later phase, underdeveloped areas—particularly revolutionary old base areas—have become new growth poles. Yet, existing literature pays relatively limited attention to counties in these underdeveloped regions, especially those in revolutionary old base areas. From the research perspective, most studies analyze regional differences at the national level, the four major regions, or the eight economic zones, while in-depth analysis from the perspective of Main Functional Zoning regarding spatial and influencing factor heterogeneity remains insufficient.Therefore, this study aims to address the following questions: Under the context of territorial space regulation, what is the development quality of new urbanization in counties of revolutionary old base areas? How do development gaps vary across different functional zones? And what are the key factors driving spatial differentiation?

Based on this, this study constructs an evaluation index system to assess the level of new urbanization in revolutionary old base areas and conducts an assessment. The geographical detector model is employed to analyze the spatiotemporal effects of various factors on counties with different main functions. This research aims to provide theoretical and practical references for promoting high-quality new urbanization and facilitating coordinated urban-rural and regional development in underdeveloped areas represented by revolutionary old base areas.

Materials and methods

Study area

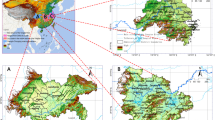

As typical underdeveloped regions, revolutionary base areas have long been the focus of attention and policy support from the central government of China.41 According to the “Opinions on Supporting the Revitalization and Development of Revolutionary Old Areas in the New Era,” issued by the State Council in 2021, there are 12 designated revolutionary old areas: the Former Central Soviet Areas of Gan, Min, and Yue (Jiangxi, Fujian, and Guangdong, GMY), the Dabie Mountain Revolutionary Base Are (DBM), the Shaanxi-Gansu-Ningxia Revolutionary Base Area (SGN), the Sichuan-Shaanxi Revolutionary Base Area (CS), the Zuo-You River Revolutionary Base Area (ZYR), the Taihang Mountain Revolutionary Base Area (THM), the Hunan-Jiangxi Border Revolutionary Base Area (XGB), the Hailufeng Revolutionary Base Area (HLF), the Qiongya Revolutionary Base Area (QY), the Yimeng Mountain Revolutionary Base Area (YMM), the Zhejiang-Southwest Revolutionary Base Area (ZXN), and the Hunan-Hubei-Chongqing-Guizhou Revolutionary Base Area (XEYQ). These areas span across 20 provinces (autonomous regions and municipalities) and include a total of 617 counties.

Under the support of policies for the revitalization of revolutionary old areas, these regions have experienced rapid socio-economic development. Data from the seventh national census show that the average urbanization rate of the 12 revolutionary old areas was only 51.60% in 2020, which is 12.29% points lower than the national average urbanization rate of 63.89%. Moreover, significant spatial disparities exist among the revolutionary old areas. For instance, the urbanization rates of the Zhejiang-Southwest Revolutionary Base Area and the Hailufeng Revolutionary Base Area were relatively high at 57.53% and 57.37%, respectively, while the Zuo-You River Revolutionary Base Area had a much lower rate of 40.62%.

The Main Functional Zones is a crucial territorial spatial planning initiative in China that classifies counties into four main functional types based on their resource and environmental carrying capacities, while also considering current development status and future potential. This scheme plays a leading role in promoting high-quality economic and social development in the country.Referring to the Main Functional Zones plans of relevant provinces associated with revolutionary old base areas in China and the State Council’s approval in September 2016 regarding the inclusion of additional counties (cities, districts, banners) into national key ecological function zones, this study categorizes the research area into three types according to development methods: Key Development Zones, Restricted Development Zones (including Major Grain-Producing Areas and Key Ecological Function Zones), and Prohibited Development Zones. It is noted that revolutionary old base areas do not include any Optimized Development Zone counties. Given that prohibited development zones are sporadically distributed at the county level assessment unit and appear as isolated points, they are excluded from this analysis. Additionally, the distinctions between national and provincial levels within Key Development Zones and Restricted Development Zones are not further detailed.

In the context of new urbanization, Key Development Zones serve as pivotal growth poles for regional high-quality development due to their favorable natural conditions, locational advantages, and strong socio-economic foundations. These zones can accommodate industrial transfers from more developed regions and attract population migrations from restricted development zones, making them the primary battlegrounds for new urbanization efforts. Major grain-producing areas, characterized by superior agricultural production conditions, play a crucial role in ensuring arable land and food security. Meanwhile, key ecological function zones shoulder significant responsibilities for regional and national ecological security. Both types of zones require guided management of population concentration and migration to avoid over-exploitation and promote sustainable development.

In terms of main functional zones, the study area encompasses 176 key development zones, 196 major agricultural product zones, and 245 key ecological function zones. The majority of these zones are categorized as restricted development areas.42 As of the end of 2020, the permanent resident urbanization rates in key development zones, major agricultural product zones, and key ecological function zones were 65.73%, 45.92%, and 46.04%, respectively. The per capita GDPs were 65,269 yuan, 47,616 yuan, and 41,966 yuan, respectively, and the forest coverage rates were 72.41%, 78.03%, and 79.77%, respectively. These figures highlight the significant imbalances in urbanization development levels across different functional zones (Figure1).

Spatial Pattern of the Main Functional Zones in the Revolutionary Base Areas.The map vector data is sourced from the Chinese Standard Map Service System (http://bzdt.ch.mnr.gov.cn/). The drawing review number is GS (2024) 0650. Map was drawn by authors, using ArcGIS 10.8 (Environmental Systems Research Institute, USA. https://www.esri.com/).

Data resource

To scientifically assess the level of NU and its influencing factors in the 12 revolutionary base areas, the primary indicator data for this study are sourced from the following five components:①Data on socioeconomic indicators were sourced from the China County-Level Statistical Yearbook 2011, China County-Level Statistical Yearbook 2021 statistical yearbooks of various provinces (municipalities, autonomous regions), prefectural-level city statistical yearbooks, and statistical bulletins on national economy and social development of cities, counties (cities, districts).②Population data were obtained from the sixth and seventh population census bulletins at the county level, the County-Level Data Compilation of China’s 2010 Population Census, and the China Population Census Yearbook 2020.③Land use data were sourced from the 30 m*30m land use datasets published by Wuhan University.④PM2.5 data were collected from the official website of the Center for International Earth Science Information Network (CIESIN) at Columbia University.⑤Data on elevation, slope, and terrain roughness were derived from Digital Elevation Model (DEM) data.

For some missing data, substitute values were calculated using the average value of the city area, the mean of adjacent years, or linear interpolation methods to ensure completeness and accuracy of the dataset. This multi-source approach ensures a comprehensive evaluation of the NU levels and their influencing factors in the revolutionary base areas.

Methods

Construction of indicator system

Constructing a multi-dimensional comprehensive indicator system is the mainstream approach for measuring NU. Traditional urbanization focuses on quantitative aspects such as population, economic, and spatial urbanization, while new urbanization centers on the development philosophy of “people-centered” growth. It balances quantitative expansion with qualitative improvement, emphasizing high-quality transformation in multiple areas including economic development, industrial agglomeration, improvement of living environments, optimization of public services, and enhancement of social security systems. The ultimate goal is to promote coordinated urban-rural and regional development and achieve synergistic progress across population, economy, society, space, ecology, and urban-rural relations.Given that there is no unified standard for NU indicators in existing research, this study takes the high-quality development concept as its guiding principle. It bases its framework on national policy documents such as the “National NU Plan (2021–2035)”, the “14th Five-Year Plan for NU Implementation Plan”, the “Five-Year Action Plan for Deeply Implementing People-Oriented NU Strategy”, the “Opinions on Promoting Urbanization Construction with Counties as Important Carriers”, and the “Outline of the 14th Five-Year Plan for National Economic and Social Development and Long-Term Goals for 2035”. Additionally, it incorporates provincial NU plans and the national standard document “Evaluation Index System for County-Level Urbanization Development Level of NU”. By referencing academic research on NU at national28 provincial21 municipal37 and county levels32,36 and using the coding process of grounded theory, an evaluation index system for NU in counties of revolutionary old areas was constructed.43 Considering the characteristics of the research area, a final evaluation index system covering six criterion layers—population, space, economy, society, ecology, and urban-rural integration—and 21 index layers was established for assessing the level of NU in counties of revolutionary old areas (Table 1).

Specifically, Population Urbanization is one of the most typical dimensions of new urbanization. Population agglomeration leads to increases in population density and demand, which in turn promotes employment in secondary and tertiary industries. It is evaluated using population density, the rate of permanent urban population, and the proportion of employed persons in secondary and tertiary industries. Economic Urbanization provides the material foundation for new urbanization. Urbanization facilitates the agglomeration of economic factors, enhancing unit economic output through economies of scale and promoting industrial upgrading toward secondary and tertiary industries. It is assessed using per capita fiscal revenue, per capita GDP, disposable income of urban residents, the proportion of secondary and tertiary industries, and economic vitality. Social Urbanization reflects the people-centered philosophy of new urbanization and plays a key role in promoting shared prosperity and equal access to basic public services between urban and rural residents. It is measured by per capita retail sales of consumer goods, per capita savings deposits, number of hospital beds per 10,000 people, average housing area per capita, and average years of education. Spatial Urbanization refers to the continuous expansion of urban landscapes and development scope across regions, reflecting development intensity and output per unit of land. It is evaluated using per capita urban construction land area, territorial development intensity, and economic density.Ecological Urbanization serves as a crucial guarantee for sustainable urbanization. A sound ecological environment has a direct impact on urban residents’ production and lifestyle. It is assessed using PM2.5 concentration, forest coverage rate, and CO₂ emissions per unit of GDP.Urban-Rural Integration highlights the critical role of counties as bridges connecting new urbanization and rural revitalization. One of the goals of Chinese modernization is achieving coordinated urban-rural and regional development, which is measured here using the urban-rural disparity coefficient and the county-level urban-rural Gini coefficient.

The range method was used to standardize these indicators, and the entropy weight method was applied for weight calculation, with specific formulas referenced from relevant literature.11 This detailed index system allows for a thorough assessment of the NU level in revolutionary old area counties, providing a solid foundation for further analysis and policy recommendations.

Dagum Gini coefficient decomposition method

The Dagum Gini Coefficient Decomposition Method is a commonly used approach for measuring regional disparities. It distinguishes itself by decomposing regional differences into within-group differences, between-group differences, and transvariation density, allowing for an accurate identification of the contribution of inter-regional gaps to overall disparity. Given its capability to provide detailed insights into the sources of inequality, this method is widely applied in various studies. In this study, the Dagum Gini Coefficient method is employed to measure the regional differences in NU among the 12 revolutionary base areas and the three major functional zones. The calculation formula for the Dagum Gini Coefficient is referenced from relevant literature.45

Geographical detector

The Geographical Detector, proposed by scholars such as Wang Jinfeng, is a spatial model designed to identify interactions among factors. It is widely used due to its advantages, including immunity to multicollinearity and endogeneity issues, and the lack of a requirement for normally distributed data. The fundamental principle of the geographical detector is that if stratification is generated by an independent variable X, then the explanatory power of X on the dependent variable Y is stronger; conversely, it is weaker. By adopting the geographical detector model, this study selects 12 indicators from aspects such as natural environment, socio-economic factors, policy support, human capital, and locational conditions. These indicators are used to explore the spatial differentiation mechanisms of NU, thereby identifying how external factors influence regional variations in NU.46

Results

Overall spatial pattern characteristics

New urbanization spatial pattern in 2010

In 2010, the comprehensive index of new urbanization across the 12 revolutionary base areas in China was 0.1080. Influenced by resource development and regional socio-economic development levels, the indices for the THM, YMM and HLF were relatively high, at 0.1788, 0.1755, and 0.1639, respectively. Additionally, the indices for the ZXN and DBM also exceeded the average level. Conversely, the indices for the CS, XEYQ, and ZYR were relatively low, at 0.0790, 0.0761, and 0.0625, respectively.Overall, there are significant differences in the development indices of new urbanization among various revolutionary base areas. For instance, the new urbanization index of the THM is approximately 2.86 times that of the lowest value found in the ZYR (Table 2). On a county-level scale, the spatial distribution of new urbanization development indices shows marked disparities. High-value counties are scarce and scattered mainly in the southern part of the THM, while low-value regions are more densely distributed and concentrated in areas such as the ZYR, CS, XEYQ, and SGN. Moreover, important aggregation areas include the western part of the GMY, the middle provincial boundary region of the DBM, and the northern and southern ends of the THM (Figure 2).

Spatial pattern of new urbanization level in revolutionary old areas in 2010 and 2020.The map vector data is sourced from the Chinese Standard Map Service System (http://bzdt.ch.mnr.gov.cn/). The drawing review number is GS (2024) 0650. Maps were drawn by authors, using ArcGIS 10.8 (Environmental Systems Research Institute, USA. https://www.esri.com/).

New urbanization spatial pattern in 2020

In 2020, the comprehensive index of new urbanization across the revolutionary old areas reached 0.1866. The indices for the THM, YMM, and HLF Area remained relatively high at 0.2669, 0.2636, and 0.2506, respectively, all above the average level. This pattern is consistent with that observed in 2010. Conversely, XEYQ, CS, and ZYR had relatively low indices, at 0.1583, 0.1518, and 0.1284, respectively.Compared to 2010, the new urbanization index of the THM was approximately 2.08 times that of the ZYR. This indicates a noticeable reduction in the disparity of new urbanization levels among different revolutionary old areas (Table 2). From the perspective of the spatial pattern of new urbanization at the county level, significant changes have occurred by 2020. High-value regions have continued to expand spatially. Counties with high values are now distributed not only in the THM but also in the GMY, YMM, and XEYQ. Low-value counties remain concentrated in the ZYR, CS, XEYQ, and SGN. However, the degree of spatial clustering has decreased (Figure2).

This evolution suggests that while disparities still exist, there has been some convergence in the levels of new urbanization across different revolutionary old areas. The expansion of high-value regions and the reduced concentration of low-value regions indicate progress towards more balanced regional development. These findings provide valuable insights for policymakers aiming to further promote equitable and sustainable urbanization across these historically significant yet underdeveloped regions.

Evolution of the spatial pattern of new urbanization from 2010 to 2020

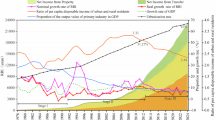

①From 2010 to 2020, the new urbanization index for revolutionary base areas increased from 0.1080 to 0.1866, with an average annual growth rate of 8.59%. The fastest-growing regions were the ZYR, XEYQ, and CS, with annual growth rates reaching 11.36%, 11.01%, and 10.07%, respectively. In contrast, regions that had already achieved relatively high levels of development, such as the THM, YMM, and HLF, experienced lower growth rates, ranging between 5% and 6% annually (Table 2). ②A correlation analysis between the new urbanization level in 2010 and the change rate of new urbanization from 2010 to 2020 revealed a correlation coefficient of −0.6439 (P < 0.01). This indicates that new urbanization exhibits a “low-fast, high-slow” development convergence characteristic, where regions with initially lower levels of urbanization tend to grow faster.③Areas with rapid increases in the urbanization index were mainly concentrated in the border regions of Guangxi, Guizhou, and Yunnan within the northern part of the ZYR, and the southern part of the XEYQ. Additionally, there were scattered high-value counties in the CS and the SGN. Low-value counties tended to cluster in the THM and YMM. It can be observed that revolutionary base areas with higher quality urbanization grew at a slower pace, while those with lower initial urbanization levels are currently experiencing a phase of rapid improvement (Figure 3).

Spatial pattern of growth rate of new urbanization level in revolutionary old areas in 2010 and 2020.The map vector data is sourced from the Chinese Standard Map Service System (http://bzdt.ch.mnr.gov.cn/). The drawing review number is GS (2024) 0650. Map was drawn by authors, using ArcGIS 10.8 (Environmental Systems Research Institute, USA. https://www.esri.com/).

Characteristics of main functional zones

The document “Opinions on Promoting Urbanization Construction with County Towns as Important Carriers” clearly states that counties should be classified into different types to achieve the goal of differentiated new urbanization development. At the same time, the 20th National Congress of the Communist Party of China clearly pointed out the deepening of the implementation of the main functional zone strategy and the construction of a national spatial pattern with complementary advantages and high-quality development.47,48 In this context, as the spatial integration point of the two strategies of new urbanization and main functional zones, how to follow the positioning of county main functions and achieve the development path of county-level characteristic urbanization is the key to promoting the high-quality development of new urbanization.49 Therefore, this paper will divide the research area into three types: key development zones, main agricultural product production zones, and key ecological function zones.

Spatial pattern of new urbanization in main functional zones

From the perspective of the Main Functional Zoning, its spatial distribution generally maintains a characteristic of “high in the east and low in the west.“And the new urbanization index shows that key development zones > major agricultural product production areas > key ecological function zones. However, the development speed is in the order: key ecological function zones > major agricultural product production areas > key development zones. The absolute gap in development has increased, but the relative gap continues to narrow. In 2010, the new urbanization index for key development zones was 0.1597, while for major agricultural product production areas and key ecological function zones, it was 0.0973 and 0.0798, respectively, approximately 60.90% and 49.94% of that of key development zones. By 2020, the ranking of new urbanization levels among functional zones remained unchanged, but the absolute gap between the functional zones’ new urbanization levels had slightly decreased. In 2020, the new urbanization level for key development zones was 0.2551, while for major agricultural product production areas and key ecological function zones, it was 0.1722 and 0.1495, respectively, approximately 67.50% and 58.60% of that of key development zones. Over the decade, these percentages increased by 6.60% and 8.66%, respectively (Table 3; Figure 4).

Evolution of development patterns in main functional zones

From the perspective of development speed, its spatial distribution pattern is opposite to that of new urbanization, showing a “high in the west and low in the east” characteristic.From 2010 to 2020, the annual growth rate of the new urbanization index for key development zones was 7.02%, only 82% of the average. In contrast, major agricultural product production areas and key ecological function zones showed high-speed growth trends, at 1.02 and 1.12 times the average, respectively. In 2010, the permanent resident urbanization rates for key development zones, major agricultural product production areas, and key ecological function zones were 53.98%, 31.62%, and 31.57%, respectively. By 2020, these figures had risen to 65.56%, 45.92%, and 46.04%, respectively, representing increases of 11.57%, 14.29%, and 14.47% over the decade. It can be seen that although the new urbanization levels of major agricultural product production areas and key ecological function zones are relatively low, their growth rates are faster. In contrast, key development zones, having entered a later stage of urbanization, exhibit relatively slower growth rates (Table 3; Figure 4).

Spatial pattern of new urbanization levels in various functional zones of revolutionary old areas from 2010 to 2020.The map vector data is sourced from the Chinese Standard Map Service System (http://bzdt.ch.mnr.gov.cn/). The drawing review number is GS (2024) 0650. Maps were drawn by authors, using ArcGIS 10.8 (Environmental Systems Research Institute, USA. https://www.esri.com/).

Regional disparities in new urbanization development

Based on the new urbanization data of 617 counties within revolutionary old areas for the years 2010 and 2020, the Dagum Gini coefficient method was used to measure regional disparities. The analysis was further broken down according to the 12 revolutionary old areas and main functional zones to reveal the sources of these disparities.

Overall, the Dagum Gini coefficient shows a decreasing trend, falling from 0.2790 in 2010 to 0.2020 in 2020. This indicates that the regional disparities in new urbanization are narrowing, suggesting a “low-fast, high-slow” convergence characteristic among county-level new urbanization levels during the study period.

Analysis of Each Revolutionary Old Area. The overall disparity, intra-regional disparity, and hyper-density in new urbanization all show varying degrees of decline, with the inter-regional disparity decreasing by 0.0610 over the decade, the largest drop.During the study period, the inter-regional Dagum Gini coefficient consistently exceeded both the intra-regional and hyper-density Dagum Gini coefficients, indicating that the overall regional disparity in new urbanization among revolutionary old areas is primarily due to inter-regional disparities.In terms of contribution rates, the contributions of intra-regional disparity, inter-regional disparity, and hyper-density to the overall disparity are ranked as follows: inter-regional disparity > hyper-density > intra-regional disparity. This further confirms that regional disparities are mainly caused by differences in new urbanization levels between regions, while intra-regional disparities are relatively small, indicating that the differences in new urbanization levels within each revolutionary old area have a minimal impact on overall regional disparity (Table 4).

Perspective of Main Functional Zones. Inter-regional disparities still dominate, highlighting the importance of narrowing these gaps as a key path to achieving high-quality new urbanization across various main functional zones.Regarding contribution rates, the contributions of intra-regional disparity and hyper-density to the overall disparity have continued to shrink, whereas the inter-regional disparity has shown an expanding trend, increasing by 2.91% over the decade. This further confirms that significant disparities between functional zones are a major obstacle to achieving new urbanization goals.The contributions of different components to overall disparity are ranked as follows: inter-regional disparity > intra-regional disparity > hyper-density. The disparities in urbanization levels within each functional zone cannot be overlooked in terms of their contribution to overall disparity, while the contribution of hyper-density is relatively small, indicating that cross-overlapping issues between different regions have a minor impact on overall regional disparity (Table 4).

Mechanisms of differentiation in new urbanization

In order to scientifically assess the impact of external factors on the new urbanization, this paper selects twelve indicators from aspects including natural environment, human capital, economic and social development, policy support, and location factors. These indicators include average slope (X1), elevation (X2), terrain relief degree (X3), human capital (X4), industrialization level (X5), per capita GDP (X6), disposable income of rural residents (X7), per capita fiscal expenditure (X8), The main functional zone strategy (X9) (with 1 assigned for key development zones, 2 for agricultural production zones, and 3 for key ecological function zones), distance to prefecture-level cities (X10), distance to provincial capitals (X11), and provincial boundary factor (X12) (with 1 assigned for provincial boundaries and 2 for non-provincial boundaries) to evaluate the influence of external factors on the new urbanization.19,24,28,29

The natural environment serves as the foundation for regional development, and factors such as slope, elevation, and terrain relief are key geographical indicators that significantly influence the spatial construction of new urbanization at the county level. Favorable geographical conditions often facilitate population agglomeration and support more effective spatial development.19 As China’s economy and society enter a stage of high-quality development, highly skilled talents tend to prefer settling in cities, thereby promoting population urbanization. Industrialization and per capita GDP mutually reinforce urbanization; the industrial and economic advancement of counties can attract labor force migration and thus enhance the level of population urbanization.24 With the continuous increase in disposable income among rural residents, there is a stronger material foundation to support rural populations in moving to cities and establishing stable lives. Per capita fiscal expenditure reflects, to some extent, the level of public services and infrastructure in a region, playing a safeguarding role in the process of new urbanization.24,28 Meanwhile, the main function zones provide directional guidance for county-level development and directly impact the level of urbanization. The distance to prefecture-level cities and provincial capitals is considered to evaluate the influence of external growth poles on counties in old revolutionary base areas. Generally speaking, due to relatively lagging socio-economic development in these areas, high-quality resources often experience severe outflow, and this phenomenon tends to be more pronounced the closer these counties are to core growth poles. Moreover, many old revolutionary base areas are located in border regions between provinces, which may have adverse effects on new urbanization.

Overall impact

Using the geographical detector method, we conducted a spatial detection analysis between the aforementioned factors and the comprehensive score of new urbanization, and calculated the direction of each factor’s influence through correlation coefficients. The average magnitude of influencing factors on the spatial pattern of new urbanization in the old revolutionary base areas from 2010 to 2020 was ranked as follows: X7 > X6 > X4 > X9 > X10 > X3 > X2 > X1 > X12 > X11 > X5 > X8. This indicates that natural environment, human capital, economic and social development, policy support, and location factors jointly shape the spatial pattern of new urbanization in these areas. However, socio-economic factors, human capital, and location factors play a dominant role, while natural and policy support factors have relatively weaker impacts. In terms of the direction of influence, natural and location factors tend to hinder the evolution of the new urbanization spatial pattern, whereas human capital, socio-economic factors, and policy support exert significant positive driving forces (Table 5).

By separately detecting the q-values of each factor’s determining power on new urbanization in 2010 and 2020, we found that natural conditions remained largely stable, indicating the foundational role of the natural environment in shaping the spatial pattern of new urbanization. Meanwhile, the influence of socio-economic factors declined somewhat, reflecting the multi-dimensional complexity involved in promoting high-quality new urbanization in the old revolutionary base areas.Specifically:① The q-values of slope (X1), elevation (X2), and terrain relief degree (X3) remained at a low level between 0.09 and 0.22, with negative directional effects. As many old revolutionary base areas are located in provincial border regions with relatively harsh geographical conditions, the cost of urban construction is relatively high, which to some extent constrains the improvement of new urbanization levels.② Disposable income of rural residents (X7) showed the highest q-value and a positive direction of influence, indicating that it is the leading factor shaping the spatial pattern of new urbanization in these areas. To promote high-quality new urbanization in the old revolutionary base areas, it is essential to steadily enhance the flow of urban-rural factors and explore a path of integrated urban-rural development.③ Per capita GDP (X6), human capital (X4), key function zone policy (X9), and distance to prefecture-level cities (X10) also had relatively strong influences. Among them, per capita GDP, human capital, and key function zone policy exhibited positive directions, suggesting that promoting economic growth, increasing regional talent pools, and implementing China’s main function zone strategy can effectively facilitate high-quality new urbanization. This indirectly confirms the necessity of analyzing new urbanization from the perspective ofmain function zones. In contrast, distance to prefecture-level cities had a negative effect, indicating that the “siphon effect” of core growth poles within prefecture-level cities intensifies the outflow of advantageous resources, thereby hindering regional development.④ Industrialization level (X5), per capita fiscal expenditure (X8), distance to provincial capitals (X11), and whether located in a provincial boundary area (X12) had relatively weak impacts, suggesting that they are secondary factors in the evolution of the spatial pattern of urbanization (Table 5).

Influence mechanisms in main functional zones

Due to the significant differences in the quality of new urbanization development across various function zones, this paper further analyzes the varying degrees of influence of each factor on counties within different function zones. Since the main function zone policy itself does not exhibit heterogeneity among categories, it is excluded from this analysis.① Slope, elevation, and terrain relief degree exert a consistently significant negative impact on the quality of new urbanization development across all three types of function zones, with relatively stable magnitudes of influence.② Human capital significantly influences counties in both key development zones and key ecological function zones, indicating its promoting role in new urbanization at the county level in these areas. However, its driving effect has slightly declined over time.③ Industrialization levels have promoted new urbanization in all three types of function zones in both 2010 and 2020, but the influence has shown a notable downward trend. This suggests that the industrial structure in old revolutionary base areas is evolving toward higher levels, and the traditional model of relying on industrialization to drive urbanization quality is becoming unsustainable.④ Per capita GDP and rural residents’ disposable income have played a dominant role in influencing new urbanization in all three function zones in both years, although their influence has been gradually weakening. Given that new urbanization encompasses multiple dimensions—economic, social, and ecological—this indicates the need to pay increasing attention to non-economic factors to achieve people-centered, high-quality urbanization.⑤ Per capita fiscal expenditure has had a significant impact on counties in all three function zones in both 2010 and 2020, with its influence continuously strengthening. Since 2012, a series of policies implemented by the central government targeting old revolutionary base areas have significantly contributed to their high-quality revitalization and development.⑥ Among the distance-related factors (to prefecture-level cities and provincial capitals), only distance to prefecture-level cities has shown significant influence. This suggests that, due to their relative distance from provincial core development zones, county-level development in old revolutionary base areas is more susceptible to the influence of municipal-level growth centers. This effect is particularly pronounced in key development zones and key ecological function zones.⑦ The provincial boundary factor has exerted a slight but consistent constraining effect overall, except for 2010 when its influence on agricultural production zones was not significant. This highlights the need for increased attention to the development of new urbanization in counties located at provincial boundaries (Table 6).

In summary, natural environmental factors impose a certain and relatively stable constraint on new urbanization development across the three main function zones. In contrast, socio-economic factors demonstrate a more pronounced influence, with significant variations in driving forces across different function zones.

Conclusions

-

1.

The new urbanization level in revolutionary old areas has seen a significant increase, from 0.1080 to 0.1866. Notably, regions such as the THM, YMM, and HLF have relatively higher indices.From the perspective of main functional zones, the levels of new urbanization follow this order: key development zones > major agricultural product production areas > key ecological function zones.There is a “low-fast, high-slow” convergence trend where regions with initially lower development quality are catching up faster compared to those with better initial conditions.

-

2.

The overall disparity in new urbanization levels within revolutionary old areas has been continuously decreasing. The primary cause of regional disparities lies in the differences in new urbanization levels between different revolutionary old areas.This suggests that narrowing the gap in new urbanization levels among various revolutionary old areas is crucial for promoting high-quality urbanization.For main functional zones, while the contribution rates of intra-regional disparities and hyper-density to overall disparities have been shrinking, the inter-regional disparities are expanding. This indicates that significant differences between functional zones pose a major obstacle to achieving new urbanization goals.

-

3.

Natural environment, human capital, socio-economic conditions, policy support, and locational factors collectively shape the spatial patterns of new urbanization in revolutionary old areas. Among these, socio-economic factors (such as rural residents’ disposable income and per capita GDP) and human capital play dominant roles.From the perspective of main functional zones, natural environmental factors impose certain constraints on new urbanization development and remain relatively stable across all three types of functional zones. In contrast, socio-economic factors exert more pronounced effects, with significant variations in driving forces across different functional zones.

Discussion

Actively promoting new urbanization strategies centered around county seats is a crucial pathway for facilitating coordinated development between urban and rural areas. Compared to previous studies, this paper makes several contributions: Firstly, While many studies have concentrated on national scales or economically significant regions11,21 this research zeroes in on revolutionary old areas, which are underdeveloped. The findings indicate that despite the relatively low quality of new urbanization in these areas, their rate of development surpasses the national average. This suggests that underdeveloped regions, represented by revolutionary old areas, will be critical growth points for achieving higher-quality new urbanization goals in China.3 Secondly, from a research perspective, Previous studies have categorized counties into metropolitan-radiated counties, potential cluster counties, and gap cluster counties based on a hierarchical perspective, assessing the quality of new urbanization development.38 However, this “hierarchical” approach mainly considers location factors at a national scale without adequately addressing natural and socio-economic factors. In contrast, focusing on main functional zones offers a more comprehensive understanding of spatial patterns and provides a more nuanced view tailored to different types of regions.49 Finally, in terms of influencing factors, the study finds that natural factors still play a foundational role in new urbanization.19 Nevertheless, socio-economic factors exert a more pronounced effect, varying significantly across different main functional zones.24 This indicates the necessity for differentiated approaches to promote high-quality new urbanization in each zone. Additionally, counties located at provincial borders often lag behind in new urbanization due to their geographic position12 making them an area of particular concern for future research.

This study also has its limitations: Classification of Counties: According to the “Opinions on Promoting Urban Construction with County Seats as Important Carriers,” counties can be classified into five categories: counties near large cities, specialized function counties, agricultural product-producing counties, key ecological function counties, and depopulating counties. This study does not yet integrate these classifications, suggesting a need for further exploration into methods and indicators for categorizing counties and aligning the four types of functional zones with the five county types.

Data availability

The datasets used and analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Yang, X. J. China’s rapid urbanization. Science 342, 310. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.342.6156.310-a (2013).

Liu, Y. S. Research on the urban-rural integration and rural revitalization in the new era in China. Acta Geogr. Sin. 73, 637–650. https://doi.org/10.11821/dlxb201804004 (2018).

Liu, Y. S. & Yang, R. Y.C.Pattern evolution and optimal paths of County urbanization in China. Acta Geogr. Sin. 77, 2937–2953. https://doi.org/10.11821/dlxb202212001 (2022).

Liu, Y. S. Characteristics and formation mechanism of the County urbanization in China. Acta Geogr. Sin. 67, 1011–1020. https://doi.org/10.11821/xb201208001 (2012).

Ding, J. J. Revitalization of old revolutionary base areas: challenges, opportunities and Pathways---- based on a 5D analytical framework. China Econ. 19, 55–84 (2024).

Zhang, M. L. Review and governance enlightenment of the state preference policy to the old revolutionary areas.chin. Publ Admin. 36, 92–96 (2020).

Cao, X. S. J.B.Spatial heterogeneity analysis of regional economic development and driving factors in china’s provincial border counties. Acta Geogr. Sin. 73, 1065–1075. https://doi.org/10.11821/dlxb201806006 (2018).

Gong, B. L., Zhang, Q. Z. & Yuan, L. R. The policy innovation and effect evaluation of the revitalization and development in old revolutionary base areas.j.manag.world.38, 26–43. https://doi.org/10.19744/j.cnki.11-1235/f.2022.0111(2022).

Deng, X. Z., Liang, L., Wu, F. & Wang, Z. B. S,J.Chinese balanced regional development strategy from the perspective of development geography. Acta Geogr. Sin. 76, 261–276. https://doi.org/10.11821/dlxb202102002 (2021).

Fang, C. L.Basic rules and key paths for high-quality development of the new urbanization in China. Geogr. Res. 38, 13–22. https://doi.org/10.11821/dlyj020180445 (2019).

Wang, J. W., Wang, Q. X. & Lu, D. D. Spatio-temporal coupling pattern and its influencing factors of digital economy, tourism economy and new urbanization: A case study of Yangtze river delta region. Geogr. Res. 43, 3301–3326. https://doi.org/10.11821/dlyj020231126 (2024).

Liu, H. L., Zhang, L. P., Wang, W. Q., Zhang, Y. & Wang, Z. L. ,F.&Guo,X.J.Spatial structure and factors influencing County urbanization of inter-provincial border areas in China. Acta Geogr. Sin. 78, 1408–1426. https://doi.org/10.11821/dlxb202306006 (2023).

Yang, Y. & Yao, Y. Study on Spatial pattern and coupling of County traffic superiority degree and new-type urbanization level in Guizhou Province. China Sci. Rep. 15:7634 https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-86346-8 (2025).

Brown, D. L. & Cromartie, J. B. L.J.Micropolitan areas and the measurement of American urbanization.popul.res. Policy Rev. 23, 399–418. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:POPU.0000040044.72272.16 (2004).

Nagendra, H., Bai, X. & Brondizio, E. S. S.The urban South and the predicament of global sustainability. Nat. Sustain. 1, 341–349. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-018-0101-5 (2018).

Shan, Z. R. Planning Strategies and Misun-An analysisof the concept, goals,derstandings of new urbanization. Urban Plann. Forum. 57, 16–22. (2013).

Zheng, X. J. et al. &Ye,Y.M.People-centered new urbanization.city plan. Rev 47, 55–60 (2023).

Chen, M. X., Zhou, Y. & Tang, Q. Y.New-type urbanization, well-being of residents, and the response of land Spatial planning.j. Nat. Resour. 35, 1273–1287. https://doi.org/10.31497/zrzyxb.20200602 (2020).

Wang, J. & Li, Y. R. Spatial pattern and influencing factors of urbanization development in China at County level: A quantitative analysis based on 2000 and 2010 census data. Acta Geogr. Sin. 71, 621–636. (2016).

Zhao, Z., Peng, P. Y., Zhang, F. & Wang, J. Y. The impact of the urbanization process on agricultural technical efficiency in Northeast china.sustainability.14, 12144 (2022). https://doi.org/10.3390/SU141912144

Ou, J. F., Xu, C. J. & Chen, D. High-quality development of new urbanization in Guangdong Province:Spatio-temporal evolution,influencing factors. Econ. Geogr. 43, 78–87. https://doi.org/10.15957/j.cnki.jjdl.2023.03.009 (2023).

Zhang, N. & Coordination Driving factors of new urbanization and water environment in Yangtze river economic belt.resour. Environ. Yangtze Basin. 33, 572–583. https://doi.org/10.11870/CJLyzyyhj202403010 (2024).

Li, T. N., Liu, Y. B., Ou, Y. X. & Wei G.E.Sustainable development of urban agglomerations around lakes in china: achieving SDGs byregulating ecosystem service supply and demand through New-type urbanization. Habitat Int.153. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.habitatint.2024.103206 (2024).

Tian, M. & Tian, Y. C. D.Spatiotemporal evolution and mechanism of multidimensional coordinated County urbanization on the Qinghai-Tibet plateau. Acta Geogr. Sin. 79, 1940–1960. https://doi.org/10.11821/dlxb202408004 (2024).

Ou, Y. X., Tang, L. & Wei, X. Y.Spatial interaction between urbanization and ecosystem services in Chinese urban agglomerations. Land. Use Policy 109, 105587https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2021.105587 (2021).

Zhou, Y., Chen, M. & Tang, Z. Z.Urbanization, land use change, and carbon emissions: quantitative assessments for city-level carbon emissions in Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei region. Sustainable Cities Soc. Sustain. Cities Soc. 66, 102701. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scs.2020.102701 (2021).

Wei, H., Xue, D., Huang, J. & Liu, M. Identification of coupling relationship between ecosystem services and urbanization for supporting ecological management: A case study on areas along the yellow river of Henan Province. Remote Sens. 14, 2277. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs14092277 (2022).

Zou, C., Zhu, J. & Lou, K. Coupling coordination and Spatiotemporal heterogeneity between urbanization and ecological environment in Shaanxi province, China. Ecol. Indic. 141, 109152.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2022.109152 (2022).

Zhang, D. & Lu, Y. Y.Spatial association effect of haze pollution in Cheng-Yu urban agglomeration. Sci. Rep. 10, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-66665-8 (2020).

Liu, H. & Zhang, Y. Evaluation on spatio-temporal development and interaction of intensive urban land use and urbanization: case studies of the cities in the Bohai rim region. Geogr. Res. 30, 1805–1817. (2011).

Chen, T., Feng, Z. & Zhao, H. Identification of ecosystem service bundles and driving factors in Beijing and its surrounding areas. Sci. Total Environ. 711 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.134687 (2020).

Ma, L., Chen, M. & Fang, F. Research on the Spatiotemporal variation of rural-urban transformation and its driving mechanisms in underdeveloped regions: Gansu Province in Western China as an example.sustain. Cities Soc. 50, 101675. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scs.2019.101675 (2019).

Fang, C. & Ren, Y. Analysis of emergy-based metabolic efficiency and environmental pressure on the local coupling and telecoupling between urbanization and the eco-environment in the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei urban agglomeration.sci. China Earth Sci. 60, 1083–1097. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11430-016-9038-6 (2017).

Deng, C. et al. How trade-offs between ecological construction and urbanization expansion affect ecosystem services.ecol.indic.122. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2020.107253 (2021).

Ding, T., Chen, J. & Fang, Z. J.Assessment of coordinative relationship between comprehensive ecosystem service and urbanization:a case study of Yangtze river delta urban agglomerations. China Ecol. Indic. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2021.108454 (2021).

Zhang, H., Deng, W., Zhang, S. & Peng, L. Impacts of urbanization on ecosystem services in the Chengdu-Chongqing urban agglomeration: changes and trade-offs. Ecol. Indic. 139 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2022.108920 (2022).

Zhou, Y., Kong, Y. & Wang, H. F.The impact of population urbanization lag on eco-efficiency: A panel quantile approach. J. Clean. Prod. 244, 118664. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.118664 (2020).

Shen, M. R. & Li, Y. China’s County-Level urbanization in the perspective of metropolitan regions and City agglomeration: Spatial types and characteristics.urban Plann. Forum 68, 91–100. https://doi.org/10.16361/j.upf.202403012 (2024).

Fan, J. Theory,strategy and path of china’s regional coordinated development during 15th Five-Year plan period.bull. Chin. Acad. Sci. 39, 605–619. https://doi.org/10.16418/j.issn.1000-3045.20240321003 (2024).

Lu, X. H., Ke, N. & Kuang, B. Features and influencing factors of difference in land urbanization level of central china.econ. Geogr.39, 192–198 .https://doi.org/10.15957/j.cnki.jjdl.2019.04.023 (2019).

Yao, S. B. et al. Assessing the impact of the National revitalization plan for old revolutionary base areas on green development. Sci. Rep. 14, 25506. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-77509-0 (2024).

Huang, Y. M. & Fu, X. AndInfluence mechanism of County High-Quality development levelfrom the perspectiveof main functions:a case Studyofthe former central Soviet areainjiangxi,fujian and guangdong.geogr.geoinform.sci.40, 124–133 .https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1672-0504.2024.04.018 (2024).

Huang, Y. M., Fu, X. & Cao, X. S. W.Construction and comprehensive evaluation of High-Quality development index system of counties in old revolutionary base areas based on grounded theory. Trop. Geogr. 43, 2191–2202. https://doi.org/10.13284/j.cnki.rddl.003765 (2023).

Liu, L. C. & Sun, Z. X. Zhang,Q.Dynamics of developmental vitality and equilibria of counties in China based on nighttime lights data. Acta Geogr. Sin. 78, 811–823. https://doi.org/10.11821/dlxb202304003 (2023).

Hao, J. X. & Zhang, Y. L.H.Research on a multidimensional dynamic environmental assessment: based on the PSR analysis framework and Bootstrap-DEA model, in the yellow river basin. China Land. 13, 2063–2063. https://doi.org/10.3390/land13122063 (2024).

Wang, J. F. Geodetector:Principle and prospective. Acta Geogr. Sin. 72, 116–134. https://doi.org/10.11821/dlxb201701010 (2017).

Qi, W., Fan, J. & Li, J. M. Y.Strategic priorities of china’s urbanized areas during 15th Five-Year plan period.bulletin of. Chin. Acad. Sci. 39, 651–662. https://doi.org/10.16418/j.issn.1000-3045.20240319006 (2024).

Tang, Y. X. et al. Z.J.Analysis of the Spatiotemporal evolution of carbon budget and carbon compensation zoning in the core area of the Yangtze river delta. Urban Agglomeration Land. 13, 747–747. https://doi.org/10.3390/land13060747 (2024).

Fan, J. Improving the institutional system of major functional zones: A discussion from the perspective of economic geography. Econ. Geogr. 44, 1–7. https://doi.org/10.15957/j.cnki.jjdl.2024.08.001 (2024).

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China(42561031);Youth Fund for Humanities and Social Sciences Research of the Ministry of Education (24YJC790069); General Project of Jiangxi Provincial Natural Science Foundation (20232BAB203063); Key Project of Science and Technology Research of Jiangxi Provincial Department of Education (GJJ210802); Key Project of Prosperous Philosophy and Social Sciences Research at Jiangxi University of Science and Technology (24FZZXLQ04).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

F. had the original idea for the study, was responsible for data collecting and data analysis, and wrote the first draft. H. was responsible for providing theoretical support and revising the paper. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Fu, X., Huang, Y. Research on the dynamic changes and influencing factors of the new urbanization level in Counties of China’s revolutionary old areas. Sci Rep 15, 31680 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-12654-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-12654-8