Abstract

During tunnel construction by the drilling and blasting method, the blasting stress waves may affect the mechanical response of existing tunnel lining structure. Based on the similarity theory, a mechanical response of existing tunnel lining structure by blasting model test is designed. The similar material of surrounding rock, explosives, and tunnel lining structure are determined by the similarity of physical mechanical parameters. This study investigates the mechanical response of existing tunnel lining concrete and reinforcing steel by the action of adjacent tunnel blasting. The experimental results reveal the maximum strain distribution and stress peak value of existing tunnel lining concrete and reinforcing steel affected by blasting load. Meanwhile, the equations are established between the peak particle velocity (PPV) and the strain (or stress) in tunnel lining concrete and reinforcing steel affected by adjacent tunnel blasting as well. These Eqs. (13) and (14) can be used to predict the maximum stress value of existing tunnel lining concrete and reinforcing steel by the action of blasting load. Simultaneously, these equations have been validated and adjusted by an actual engineering project field test. Thus, evaluating the stress states of tunnel lining caused by adjacent tunnel blasting is more effective. This finding is of great significance for evaluating the stress state of existing tunnel lining structure, as well as providing theoretical guidance and reference for the design of blasting parameters on adjacent tunnel construction.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

As a critical engineering structure for humans utilizing underground space, tunnels play a vital role in transportation infrastructure. However, it is inevitable to meet various complex engineering environments during the tunnel construction and operation, particularly the vibration impact of tunnel structure by adjacent tunnel blasting load. Blasting stress waves not only have a strong vibration effect on tunnel surrounding rock or soil but also may pose a threat to the safety and stability of existing tunnel lining structure1,2,3. Therefore, studying the dynamic response of adjacent tunnel lining structure by blasting load is of great significance for ensuring the safety of tunnel operation as well as promoting the rational use of underground space.

The mechanical response of tunnel structure under blasting load is an important basis for evaluating the safety and stability of tunnel. In recent years, some scholars have investigated the influence of blasting load on tunnel structure by blasting theoretical and numerical simulations, and these studies have achieved some useful results.

In studies of blasting theoretical models, some scholars have investigated the propagation and vibration attenuation law of blasting load in existing tunnel structure, such as wave equation, finite element method, and difference method4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12. These studies provide a basis for further analyzing vibration response and are valuable for predicting structural dynamic response. Such as a study13 proposed the concept of effective vibration duration by measuring blasting vibration from a subway tunnel beneath a building. Some scholars proposed suggestions for optimizing the design of damping holes by analyzing the key factors affecting blast damping from a theoretical perspective and establishing a numerical model6. This year a new study14 explored the evolution characteristics of the PPV and frequency in an existing railway tunnel. The results indicated that the influence of frequency on blasting vibration response can be quantified quantitatively by quantifying the dynamic amplification factor. Moreover, one of the most important studies15 is to consider the amplification effect of vibration diffraction and reflection, which is caused by an explosion around the tunnel by field monitoring and simulation, that proposed an equation for predicting the PPV in adjacent tunnel segment within the blasting center, which is more accurate predicting the PPV for rock tunnels.

In numerical simulation studies, some scholars studied the PPV, stress distribution, and deformation of existing tunnel lining structures under the action of blasting load by finite element and discrete element methods as well6,16,17,18,19,20. Such as a study20,21 who investigated the mechanical properties and pressure levels of tunnel structures under internal explosions by a finite element model of assembled lining structure. Moreover, in field experiments, researchers measured and simulated the vibrational response of existing tunnel lining structure by field test and model test8,11,12,15,22,23,24,25,26. Based on the on-site monitoring, some researchers18,27,28,29,30 analyzed the stress distribution characteristics and vibration propagation law and proposed the safety threshold of existing tunnel. The research findings reveal the vibration law and damage mechanism of tunnel structure by different blasting conditions, which provides a basis for optimizing construction processes and controlling structural safety during tunnel construction.

These studies show that the dynamic response of tunnel lining structure is a complex problem by blasting load, that involves the effects of many factors. In the current research results, many scholars take the PPV as an index that evaluates tunnel structural safety affected by blasting load. However, it cannot fully reflect the stress state and mechanical evolution of tunnel lining concrete and reinforcing steel. Although some research achievements have been made, there are still many challenges and problems that need further study.

This study employs a similarity model test to investigate the dynamic response of tunnel structure affected by blasting load. The research explores the strain distribution of tunnel lining concrete and reinforcing steel affected by blasting load. Simultaneously, the equations are established between the PPV and the strain (or stress) in tunnel lining concrete and reinforcing steel affected by adjacent tunnel blasting as well.

Similarity theory

A set of similar theories has been developed to study the relationship between individuality and commonality, or between general and specific phenomena that play a role in scientific research. Similarity theory is primarily used to guide model experiments, determining the levels and degrees of similarity between the “model” and the “prototype”. Among these, the First and Second Principles of Similarity Theory are the most representative.

The first principle of similarity theory

If the variables between N phenomena can undergo similar transformations, then these N phenomena are considered similar phenomena, Meanwhile, these N phenomena follow the Eq. (1) ref.31.

The second principle of similarity theory

The Second Principle of Similarity Theory (Sedov, L.I., 2018), known as the \(\pi\)-Theorem, is expressed for the independent and dependent variables of a given phenomenon by the Eq. (2) to (6).

In the above equation, \(k\) as physical quantities have independent dimension, while the remaining physical quantities have derived dimension. By the second similarity transformation, the equation can be converted into a function of dimensionless similarity criteria among \(\pi_{1} ,\pi_{2} , \cdot \cdot \cdot ,\pi_{n - k}\), as the Eq. (3).

where, \(\pi_{1} ,\pi_{2} , \cdot \cdot \cdot ,\pi_{n - k}\) are similar criteria.

In similarity model testing, the prototype (P) and the model (M) are phenomena that are like each other, and their relationship of equations is also identical, as the Eq. (4).

For phenomena that are like each other, the similar criteria remain constant at corresponding points and times. Therefore, follow the Eq. (5).

This research takes the maximum single charge quantity in tunnel blasting, the depth and distance from the blasting center, the physical properties of rock mass, and the PPV as the main factors affecting tunnel lining concrete stress and steel stress. The relationship between the relevant parameters of the tunnel blasting dynamics similarity model is expressed as the Eq. (6).

where, \({\text{Q}}\) is the maximum single charge quantity, \({\text{H}}\) is the blasting center depth from the free surface, \({\text{R}}\) is the blasting center distance, \({\text{C}}_{\text{p}}\) is the longitudinal wave velocity of the rock mass, \({\text{E}}\) is the elastic modulus of rock mass, \(\mu\) is Poisson’s ratio, \(\rho\) is the density of rock mass, \({\text{v}}\) is vibration velocity, \(\sigma_{s}\) is concrete stress and \(\sigma_{R}\) is steel stress.

Mechanical parameter similarity ratio

The experimental model conforms to both static similarity and dynamic similarity. Similar materials are assumed to be elastic continuous media in modeling tests of blasting. According to the theory of elasticity, the dynamic characteristic as the Eq. (7) ref.32.

where, R is the loading matrix, M is the quality matrix, a is the acceleration matrix, C is the damping matrix, v is the velocity matrix, K is the stiffness matrix; u is the displacement matrix.

Tunnel blasting is a complex dynamic process, where the surrounding rock plays a role in transmitting the blasting loads. Therefore, the mechanical parameters of the surrounding rock material are a crucial factor. Material parameters as key indicators and their dynamic characteristics as the Eq. (8).

where, σ is stress, MPa; u is displacement, m; l is length, m; v is velocity, m/s; g is gravitational acceleration, m/s2; ρ is density, g/cm3; E is elastic modulus, Pa; T is time, s; \(\omega\) is frequency, Hz.

The geometric and density similarity ratios to construct the experimental model are determined by tunnel lining and surrounding rock conditions. Take the length and mass as fundamental dimensions, and the material parameters similarity ratio determined by the Similarity Theory, which can be expressed as the Eq. (9).

Moreover, the damping similarity ratio as the Eq. (10).

The similar model and tunnel engineering background are in the same gravitational acceleration, with a similarity ratio of 1. According to the First and Second Principles of Similarity Theory, and considering the experimental conditions, the geometric similarity ratio \({\text{C}}_{\text{L}}\) is 25, and the density similarity ratio \(C_{\gamma }\) is 1, if physical and mechanical parameters are similar within the elastic range. By the similarity criteria, the similarity ratios of various physical and mechanical parameters between the prototype and model are shown in Table 1.

Self-similar model

Similar materials

In this investigation, gravel is used as the aggregate, cement as the binding material, besides soil and river sand are employed to adjust the similar material density33. The optimal mechanical parameters of the materials are obtained by tests on a universal testing machine, as shown in Table 2. The material physical and mechanical parameters of the surrounding rock model and the prototype are shown in Table 3.

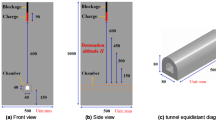

Tunnel lining structure

The equivalent tunnel cross-section of the tunnel lining concrete model is scaled at a ratio of 25:1, as shown in Fig. 1. Considering the effects of concrete and reinforcing steel, the C30 concrete has been used as both the lining material and the prototype in the experiment. The research focuses on the strain distribution and stress peak value of concrete and reinforcing steel in tunnel secondary lining. The tunnel secondary lining thickness is 40 cm comes from an engineering background, and the experimental model tunnel lining thickness is 1.6 cm reduced by a ratio of 25:1. For the experiment, the reinforcing steel is simplified by the model dimensions taking the hot rolled plain bars, with a transverse spacing of 15 cm, and a nominal diameter of 6 mm and a length of 60 cm. Longitudinal reinforcing steel are placed at the arch crown (point 3), arch waist (points 2 and 4), arch foot (points 1 and 5), and arch bottom (point 6), respectively. Strain monitoring points are set at the intersections of the transverse and longitudinal reinforcing steel, with strain gauges installed at these points (parameters: 120-3AA; Sensitivity: 2.0 mV/V; Resistance: 120Ω), as shown in Fig. 2.

Equivalent explosives

The experimental explosive is black powder. Experimental analysis of TNT and black powder equivalent values indicates that the overpressure and charge of both TNT and black powder follow a similar linear relationship, the effective of TNT is twice as much black powder within the explosive charge of 500 g.

From the aspect of overpressure on an explosion shock wave, the equivalent value of black powder is approximately 0.5 times TNT34. The overpressure curves of TNT and black powder are shown in Fig. 3. According to the explosive charge of the engineering background (Zhongliangshan Tunnel), using the principles of geometric similarity and equivalent explosion, the TNT equivalent is calculated to be 4 g, and the weight of a single black powder charge is 8 g.

TNT and black powder overpressure graph34.

Model test

Model parameters

By Similarity Theory calculations, the dimensions of the model test in length, width, and height are 140, 60 and 45 cm, respectively. The distance between existing tunnel and excavated tunnel is 25 cm, and the blasting is located at the center of the tunnel excavation in a section 30 cm from the model surface (Z = 0 plane). The distance from the tunnel to the edges on both sides is 15 cm, and the distance from the nearest measuring point 2 to the blasting center is 46 cm. Polyurethane fills the side boundaries to reduce reflections of the blasting stress waves35, as shown in Fig. 4.

Measurement points

Strain gauges are arranged at the tunnel vault, the arch waist, and the arch toot points on the tunnel lining concrete and reinforcing steel in the model. The measuring points of lining concrete and reinforcing steel are indicated by C and S respectively. Six reinforcing steel are arranged longitudinally, with six measuring points (1 to 6) in each section, as shown in Fig. 5. One section is set up every 15 cm in the tunnel’s circumferential direction, with a total of 5 measuring points (A to E) on each section, as shown in Fig. 6.

In the calculation of stress for measuring points of lining concrete and reinforcing steel, the correction formula for wire resistance is considered as the Eq. (11).

where, \(\sigma\) is Measuring point stress, MPa; \({\text{E}}\) is Elastic modulus, MPa; \({\text{r}}_{\text{e}}\) is wire resistance, Ω; \({\text{R}}_{\text{g}}\) is strain gauge resistance, 120Ω; \(\varepsilon_{i}\) is test strain value.

Data acquisition

The experiment used a dynamic strain data acquisition instrument (type, DH8303N) and blasting vibration meter (type, TC-4850) to collect data on the strain and the PPV of tunnel lining structure measuring points, as shown in Fig. 7.

Experimental process

This experiment investigates the mechanical response of existing tunnel structure approach tunnel blasting. The main experimental steps are as follows.

Firstly, construct the reinforcing steel cage and attach strain gauges to the positions. Place the reinforcing steel into the mold, and make the concrete into a tunnel shape, then attach the strain gauges to the corresponding positions.

Secondly, fill the inner walls of the surrounding rock mold with polyurethane, according to the specified ratio, preparing similar rock materials into shape. Simultaneously, testing similar materials in the same batch to determine the mechanical parameters of materials. Drilling blasting holes in the tunnel face and charging the equivalent number of explosives in this experiment.

Thirdly, connect the strain gauge wires to the data acquisition instrument and link the data acquisition instrument to the computer. Fix the vibration velocity sensors at corresponding positions on the lining and connect wires to the blasting vibrometer. Conduct blasting tests and data collection.

Experimental data analysis

Strain and stress analysis

The tunnel lining concrete and reinforcing steel experiences internal stress from temperature and shrinkage. If there is a significant strain difference between the lining concrete and reinforcing steel, then the influence of blasting stress waves can lead to relative slippage, and finally the lining concrete and reinforcing steel will exfoliate each other. In this experiment, the charge weight of black powder for each single detonation is 8 g. By data analysis of the strain in the lining concrete and reinforcing steel at each measuring point under the action of blasting loads, as shown in Fig. 8.

The maximum strain diagram of lining concrete and reinforcing steel in tunnel’s longitudinal direction: (a) Surveying lines C1 and S1 on the left arch foot; (b) Surveying lines C2 and S2 on the right arch waist; (c) Surveying lines C3 and S3 on tunnel vault; (d) Surveying lines C4 and S4 on the left arch waist; (e) Surveying lines C5 and S5 on the right arch foot; (f) Surveying lines C6 and S6 on tunnel floor.

From the data analysis of Fig. 8. The maximum strain for tunnel lining concrete and reinforcing steel is observed at surveying lines C2 and S2 on the right arch waist near the blasting side, with the lining concrete and reinforcing steel strain values of 85.7 and 17.2µε, respectively. The maximum strain difference at this point is 68.5µε. On the other side, the minimum strain for tunnel lining concrete and reinforcing steel is observed at surveying lines C5 and S5 on the left arch waist, with the lining concrete and reinforcing steel strain values of 9.5 and 4.1µε, respectively.

To analyze the tunnel lining strain and stress distribution along the tunnel’s longitudinal by blasting loads. The stress variation diagrams of the lining concrete and reinforcing steel along the tunnel’s longitudinal (Z-axis) were derived from the test data analysis, as shown in Fig. 9. The measured strain was converted to stress, revealing the stress distribution along the tunnel’s longitudinal, as shown in Fig. 10.

From analysis of Figs. 9 and 10, the strain distribution in tunnel lining concrete and reinforcing steel is similar, with section C and blasting center located at the same tunnel section (Z = 0 plane), and the maximum strain at each measuring point is observed at section C. Based on the relationship between strain and stress, the maximum strain of lining concrete and reinforcing steel is located at measuring points C2 and S2 on the right arch waist, with values of 2.6 and 3.6 MPa, respectively. Meanwhile, the minimum strain of lining concrete and reinforcing steel is located at measuring points C4 and S4 on the left arch waist, with values of 1.1 and 1.2 MPa, respectively. The results show that the strain attenuation trend of the tunnel’s longitudinal lining concrete is consistent with that of the reinforcing steel under blasting loads, with the “space effect” significantly influencing the attenuation of blasting stress waves.

Along the tunnel’s longitudinal axis, the strain in both the lining concrete and reinforcing steel decreases as it moves away from the section near the blasting center, showing a distribution pattern with higher values in the middle and lower values on the sides. The strain attenuation rates differ at various measuring points influenced by the “spatial effect”. The smaller strain differences at each point of the reinforcing steel measuring line at the left arch foot suggest that the stress (or strain) of the reinforcing steel is significantly influenced by structural freedom. Testing indicates that the blasting load’s attenuation rate differs between the arch foot and tunnel vault, with the tunnel vault experiencing a greater attenuation than the arch foot along the tunnel’s longitudinal direction.

The stress values for each measuring point will be calculated via the experimental strain data and the stress variation envelope diagrams for each tunnel section. Furthermore, the stress variation distribution for the tunnel’s circumferential lining concrete and reinforcing steel will be determined in tunnel sections A to E, as shown in Fig. 11.

It can be concluded from Fig. 11: On the one hand, the reinforcing steel stress at each measuring point exceeds that of the lining concrete in tunnel’s longitudinal lines 2, 3, 5, and 6, with the highest difference of 1.3 MPa observed at measuring point No. 2 on Section D. Conversely, the reinforcing steel stress is lower than the lining concrete along tunnel’s longitudinal lines 1 and 4, except at measuring point No. 4 on Section C, with the maximum difference of 0.4 MPa observed at measuring point No. 1 on Section E. The experiment indicates that tunnel lining steel is more responsive to blasting loads than the lining concrete. On the other hand, the experiment reveals a strain and stress difference between the tunnel lining concrete and the reinforcing steel affected by blasting loads, which means the deformation is inconsistent. This phenomenon results in a tangential stress component at the interface between the lining concrete and reinforcing steel, primarily causing slippage (or separation) of the two. Finally, the tunnel lining structure experiences stress concentration affected by blasting loads as well, evident at the points closest to the blasting side in measuring line 2 on the model, particularly at the second measuring point on sections C and D. The lack of coordinated deformation leads to cracks at the interface between the concrete and reinforcing steel by the action of adjacent tunnel blasting loads, which cracks may further widen by repeated blasting loads. Furthermore, the stress concentration can increase the stress several times at the crack’s edge by Saint–Venant’s principle, tunnel lining penetrates cracks will be formed by the action of repeated blasting loads, which will eventually threaten the safety and stability of tunnel structure.

Vibration velocity analysis

The PPV is a crucial indicator for assessing the impact of blasting vibrations on structural safety. It reflects the peak particle acceleration experienced by the structure at the instant of blasting loads. Therefore, it is essential to control the PPV of the tunnel structure below the safety threshold to ensure tunnel structural integrity. Focuses on the measuring point along line 2, which exhibits the highest strain response on the blasting side. The vibration velocity data was collected by blasting the vibration monitor, including analyzing the Vx, Vy, and Vz of the X, Y, and Z directions. The time-history curve of the vibration velocity at measuring point 2 in Section C, as shown in Fig. 12.

It can be assumed that the blasting vibration velocities of lining concrete and reinforcing steel are equal within a small region at corresponding measuring points in the tunnel lining structure during the blasting experiment. The PPV of measuring point 2 in Section C is concentrated between 0.015 and 0.03 s, after which it gradually decreases, as shown in Fig. 10. The PPV in the X, Y, and Z directions are 1.03 cm/s, 1.07 cm/s, and 0.46 cm/s, respectively. Therefore, the resultant sum vector velocity in these three directions is 1.28 cm/s.

Analysis of the blasting vibration velocity data from line 2 has yielded the PPV curve for each of its measuring points, as illustrated in Fig. 12. The PPV curves for each measurement point on line 2 were obtained by analyzing the PPV of experimental data, as shown in Fig. 13.

From Fig. 13, it can be observed that the PPV in the X, Y, and Z directions along line 2 decreases as it moves away from the section Z plane (the blasting center section). Comparing the PPV trends between the completed support section (Z < 0) and the unexcavated section (Z > 0) of line 2 in the model test, it reveals that the tunnel’s PPV is not significantly affected by the “spatial effect”.

Establish the equations relating vibration velocity to strain

When it comes to strain testing of lining structures affected by blasting loads presents certain challenges during tunnel construction. Some scholars both domestically and internationally evaluate the safety of tunnel lining structure adopt the PPV and the particle vibration frequency (PVF). However, the PPV and the PVF cannot accurately reflect the stress state of tunnel lining structures by the action of blast loads. Therefore, we focused on measuring line 2 to further investigate the relationship between the PPV and the maximum strain, which showed the maximum response on the blasting side and the sum vector velocity of measuring points and their corresponding strain values were analyzed. The relationship curves between the sum vector velocity and strain (stress) were obtained from the experimental data, as shown in Fig. 14.

From Fig. 14, by performing correlation analysis of the data from the reinforcing steel measuring point on line 2, which had the maximum strain response on the blasting side, the relationships between the PPV and the maximum strain of both the lining concrete and reinforcing steel were derived as follows.

where, \(V\) is the PPV, cm/s; \({\text{R}}_{1}^{2}\) and \({\text{R}}_{2}^{2}\) is the correlation coefficient.

The Eqs. (12) and (13) can be converted into the relationships between the PPV and the maximum stress of both the lining concrete and reinforcing steel were derived as follows.

where, \({\text{E}}_{\text{R}}\) is dynamic elastic modulus of concrete, \({\text{E}}_{\text{c}}\) is dynamic elastic modulus of reinforcing steel, GPa.

The curve fitting analysis of the data in Fig. 14 shows that the correlation coefficient of the lining concrete and reinforcing steel are 0.958 and 0.965, respectively, by the relationship between the PPV and the maximum strain. This means the correlation coefficient is closer to 1, the higher degree of correlation. Therefore, the strain values for the tunnel lining concrete and reinforcing steel can be calculated by Eqs. (14) and (15) during tunnel construction. This is more scientific to evaluate the stress state of the tunnel lining structure affected by blasting loads.

Application

Engineering background

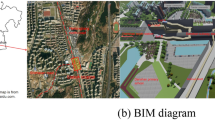

The new Zhongliang Mountain Tunnel is being constructed by an approach to existing tunnel. The newly built tunnel is more than 3200 m which belongs to the super long highway tunnel crossing the mountain, and the maximum burial depth is 280 m. The newly built tunnel is located at a distance (D1) of 25 to 68 m from the existing tunnel on the right side, and the left side is located at a distance (D2) of 31 to 53 m from existing tunnel left line. The newly built tunnel was constructed by the drilling and blasting method, and once the newly built tunnel was completed, it would form a four-tube highway tunnel with eight lanes in two directions. The plane relative position diagram of the newly built tunnel and existing tunnel, as shown in Fig. 15.

The newly built tunnel and existing tunnel plane’s relative position. Baidu Maps. (2025). Satellite image of Zhongliang Mountain Tunnel on the Chengdu-Chongqing Expressway. Retrieved April 6, 2025, from https://map.baidu.com.

Measuring point layout

The secondary lining of existing tunnel is made of C30 concrete. The strain of the reinforcing steel cannot be monitored in field tests due to the requirement of preserving the integrity of existing tunnel lining structure. Therefore, the PPV and surface strain of the lining structure were monitored instead. The surface strain and the PPV data of tunnel lining structure were collected by dynamic signal data acquisition instrument (DH8303N) and wireless remote transmission blasting seismometer (TC-4850N). The measuring points were placed 1.5 m above the arch foot closest to the explosion center, and the vibration monitoring points (M1 to M5) and strain measuring points (H1 to H5) are arranged every 15 m along the tunnel’s longitudinal direction, with the following specifications, type of strain gauge is 120-3AA, sensitivity of 2.0 mV/V, and resistance of 120 Ω, as shown in Fig. 16.

Data analysis

The impact of existing tunnel lining structure was assessed by measuring the PPV and surface stress caused by the blasting loads of newly built tunnels. The maximum calculation and experimental stress data on the surface of existing tunnel lining were calculated by formula (14), as shown in Fig. 17.

It can be observed that from Fig. 17, the PPV is 1.13 cm/s at measuring point M3 on existing tunnel lining caused by blasting loads of the newly built tunnel. The relationship between the PPV and the surface stress can be calculated by formula (14), and the maximum surface stress at measuring point M3 is calculated to be 2.0 MPa. Meanwhile, the experimental surface stress was 1.52 MPa calculated by the relationship between stress and strain at the same point. The maximum error value at measuring point M3 is 0.48 MPa. This discrepancy may be due to boundary effects in the model test and the sensitivity of the strain gauges on existing tunnel lining.

However, by analyzing the changing trend, it is evident that the calculated values of the surface stress on existing tunnel lining are consistent with experimental values. Accordingly, it is necessary to introduce a correction factor \(\alpha\) to Formula (14) to show a good fit with experimental test values. The calculated values of Formula (14) fit well with experimental values when the correction factor \(\alpha\) is 0.25 by data analysis. This study indicates that the fitted equation proposed in this paper can be used to effectively predict the surface stress of tunnel lining caused by the blasting loads of tunnel construction.

Conclusions and discussion

This study designed a model experiment to investigate the mechanical response of existing tunnel lining structures affected by blasting loads on adjacent tunnel construction based on the Similarity Theory. Analysis of the experimental results obtained the following conclusions.

-

1.

The strain difference between tunnel lining concrete and steel reinforcement under blast loads is a critical factor leading to debonding. Experiment shows that the maximum strain difference is 68.5uε, which was converted to a maximum stress difference is 1.1 MPa. Due to the “spatial effect” of existing tunnels, the scattering of explosive stress waves intensified the wave attenuation during propagation, which resulted in weakened stresses on the non-blast side.

-

2.

The experimental results indicate that the strain differences between the reinforcing steel on the tunnel floor and the arch feet are relatively lower are influenced by the degrees of structural freedom. And the attenuation rate on the tunnel vault is greater than the tunnel floor along the tunnel’s longitudinal direction. Consequently, it is crucial to monitor stress changes of existing tunnel lining structure on the blasting side.

-

3.

The stress distribution of lining concrete and reinforcing steel in tunnels’ circumferential direction was obtained by experimental analysis. Which indicate that the stress envelope exhibits a consistent trend for both the lining concrete and reinforcing steel. However, there are noticeable differences between the stresses or strains of existing tunnel lining structures affected by blasting loads resulting in tangential stress at the contact surface, which is the primary factor causing slippage and exfoliation phenomenon.

-

4.

The relationship between the PPV and stress both lining concrete and reinforcing steel were established by experiment, with correlation coefficients were 0.958 and 0.965, respectively, as shown in Eqs. (13) and (14). By field experiment, the equations can effectively predict the stress of tunnel lining with the correction factor \(\alpha\) is 0.25.

Data availability

Data will be made available on request. Please contact Dr. Bin Zhang at 2020007@cqust.edu.cn for access to the data.

References

Du, H. et al. Numerical investigation on damage characteristics of surrounding rocks in the deep underground tunnel subjected to full-face smooth blasting. Sci. Rep. 15, 14659. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-98544-5 (2025).

He, B. et al. A deep dive into tunnel blasting studies between 2000 and 2023-a systematic review. Tunn. Undergr. Sp. Technol. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tust.2024.105727 (2024).

Liu, C. et al. Experimental investigation on damage development and failure mechanism of shield tunnel lining under internal blast considering stratum-structure interaction. Undergr. Sp. 21, 81–99. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.undsp.2024.07.004 (2025).

Duan, J. et al. Study on stress wave propagation and failure characteristics of key parts in tunnel under blasting load. Sci. Rep. 14, 29034. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-80223-6 (2024).

Ge, L. et al. Research on blasting damage to tunnel surrounding rock based on acoustic full waveform signal analysis. Sci. Rep. 15, 7174. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-92003-x (2025).

Guan, X. et al. Vibration response and failure modes analysis of the temporary support structure under blasting excavation of tunnels. Eng. Fail. Anal. 136, 106188. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engfailanal.2022.106188 (2022).

Li, T. et al. Analysis of the characteristics of blasting seismic wave induced by explosive blasting with different coupling medium. Sci. Rep. 15, 6721. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-86682-9 (2025).

Li, Y. et al. Experimental study of the dynamic responses of surrounding jointed rock masses and adjacent underground openings and induced ground vibrations subjected to underground explosion. Tunn. Undergr. Sp. Technol. 135, 105060. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tust.2023.105060 (2023).

Zhao, D. et al. Numerical investigations on dynamic responses of subway segmental tunnel lining structures under internal blasts. Tunn. Undergr. Sp. Technol. 135, 105058. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tust.2023.105058 (2023).

Zhao, R., Tao, M., Wu, C., Wang, S. & Zhu, J. Spallation damage of underground openings caused by excavation disturbance of adjacent tunnels. Tunn. Undergr. Sp. Technol. 132, 104892. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tust.2022.104892 (2023).

Zhou, J., Shu, P., Zhang, B., Deng, B. & Wu, Y. A finite element analysis of tunnel lining demolition by blasting for subway tunnel expansion. Appl. Sci. https://doi.org/10.3390/app12199564 (2022).

Zhang, B. et al. Mechanism and application of blasting technology using phase-difference vibration mitigation on adjacent railway tunnel. Shock Vib. https://doi.org/10.1155/2022/3836086 (2022).

He, R., Jiang, N., Li, D. W. & Qi, J. F. Dynamic response characteristic of building structure under blasting vibration of underneath tunnel. Shock Vib. 2022(1), 9980665. https://doi.org/10.1155/2022/9980665 (2022).

Zhao, Y., Shan, R. & Wang, H. Blasting vibration effect and safety evaluation method of railway cross tunnels. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 145, 105588. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tust.2024.105588 (2024).

Wang, X., Li, J., Zhao, X. & Liang, Y. Propagation characteristics and prediction of blast-induced vibration on closely spaced rock tunnels. Tunn. Undergr. Sp. Technol. 123, 104416. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tust.2022.104416 (2022).

Dang, V. K. et al. Impact of blasting at tunnel face on an existing adjacent tunnel. Int. J. Geomate 15, 22–31. https://doi.org/10.21660/2018.47.04640 (2018).

Guan, X., Wang, X., Zhu, Z., Zhang, L. & Fu, H. Ground vibration test and dynamic response of horseshoe-shaped pipeline during tunnel blasting excavation in pebbly Sandy soil. Geotech. Geol. Eng. 38, 3725–3736. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10706-020-01249-x (2020).

Guan, X., Yao, Y., Yang, N., Xu, H. & Xin, B. Analysis of factors influencing vibration reduction and design optimization of damping holes in adjacent tunnel blasting. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 19, e02448. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cscm.2023.e02448 (2023).

Xia, J., Wang, B., Guo, X. & Xie, Z. Vibration response and safety control for blasting vibration of the existing tunnel with defects. Undergr. Sp. 15, 76–89. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.undsp.2023.08.011 (2024).

Zhao, Y. Research on vibration effect of tunnel blasting based on an improved Hilbert-Huang transform. Environ. Earth Sci. 80, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12665-021-09506-9 (2021).

Luo, H., Tao, M., Hong, Z., Xiang, G. & Wu, C. Analysis of the dynamic response and damage characteristic for the tunnel under near-field blasts and far-field earthquakes. Undergr. Sp. 21, 331–351. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.undsp.2024.09.003 (2025).

Fu, H., Kong, H. & Wu, J. Experimental study on the stability of surrounding rock in tunnel blasting construction. Stavební Obz. Civ. Eng. J. 27, 72–87. https://doi.org/10.14311/cei.2018.01.0007 (2018).

Iwano, K., Hashiba, K., Nagae, J. & Fukui, K. Reduction of tunnel blasting induced ground vibrations using advanced electronic detonators. Tunn. Undergr. Sp. Technol. 105, 103556. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tust.2020.103556 (2020).

Shan, R., Zhao, Y., Wang, H., Liu, Z. & Qin, H. Blasting vibration response and safety control of mountain tunnel. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10064-023-03199-z (2023).

Xu, M. et al. Influence of the spatial distribution of underground tunnel group on its blasting vibration response. Undergr. Sp. 10, 248–268. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.undsp.2022.10.006 (2023).

Zhao, Y., Shan, R. L., Wang, H. L. & Xin, B. Y. Vibration response and evaluation system of cross-tunnel blasting. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10064-022-02911-9 (2022).

Chu, H., Yang, X., Li, S. & Liang, W. Experimental investigation of the propagation and attenuation rule of blasting vibration wave parameters based on the damage accumulation effect. Shock Vib. https://doi.org/10.1155/2018/2493149 (2018).

Yu, J. et al. Vibration response characteristics of adjacent tunnels under different blasting schemes. Shock. Vib. 2021, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/5121296 (2021).

Zhang, Z., Shi, X., Qiu, X. & Ouyang, J. On-site tests investigating the effects of blasting vibration amplitude on the dynamic response of thin spray-on liner. Tunn. Undergr. Sp. Technol. 145, 105620. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tust.2024.105620 (2024).

Zhang, Z. et al. Dynamic response and safety control of civil air defense tunnel under excavation blasting of subway tunnel. Tunn. Undergr. Sp. Technol. 112, 103879. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tust.2021.103879 (2021).

Sedov, L. I. Similarity and Dimensional Methods in Mechanics (CRC Press, 2018).

Wu, Z., Wu, H. J. & Han, F. Elasticity (Beijing Institute of Technology Press, 2017).

Gong, J. & Chen, S. Orthogonal test on the ratio of similar materials in tunnel blasting mechanical mode. J. Huaqiao Univ. (Nat. Sci. Ed.) 41, 164–170 (2020).

Chen, J. & Cai, X. Experimental analysis of TNT equivalent value of black powder. Criminal Tech. https://doi.org/10.16467/j.1008-3650.2003.s1.074 (2003).

Du, X. et al. Study on energy absorption of paper honeycomb sandwich tube filled by polyethylene foam under axial loading. Sci. Rep. 14, 22460. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-73351-6 (2024).

Funding

This work was supported by the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (No. 2023MD734186), the Natural Science Foundation of Chongqing (2024NSCQ-LZX0138/2023NSCQ-MSX0197), the Chongqing Municipal Education Commission Science and Technology Fund (No. KJQN202501522). Chongqing Natural Science Foundation General Project (No. CSTB2023NSCQ-MSX0208, CSTB2022NSCQ-MSX0518). State Key Laboratory of Mountain Bridge and Tunnel Engineering Open Foundation (No. SKLBT-2110).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Bin Zhang: writing—original draft, conceptualization, funding acquisition, writing—review and editing. Chen Li: software, data curation, writing—review and editing. Jianlin Li: investigation, data curation, formal analysis. Ruizhe He: data curation, formal analysis. Xuefu Zhang: resources, supervision. Xiaogang Li: project administration, supervision. Zijian Wang: resources, investigation. Yi Wu: formal analysis, investigation.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, B., Li, C., Li, J. et al. Experimental study on dynamic response of existing tunnel lining structure by adjacent tunnel blasting load. Sci Rep 15, 28473 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-12687-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-12687-z