Abstract

Nondestructive characterization of elastic constants for laminated composites is critical for certifying manufactured composites before their use in various engineering applications. This paper presents an ultrasonic guided wave-based inversion approach, which leverages (i) noncontact laser Doppler vibrometry, (ii) frequency-wavenumber analysis, as well as (iii) an inversion algorithm with a unique objective function based on Legendre orthogonal polynomial expansion (LOPE) and genetic algorithm (GA) optimization, for determining the elastic constants of laminated composites. To implement this approach, laser vibrometry is used to acquire time–space wavefields of guided waves. The wavefields are then transformed into frequency-wavenumber spectra via multi-dimensional Fourier transform, unveiling the frequency-wavenumber relations in different directions, which are subsequently processed by our LOPE-based inversion algorithm. Particularly, this algorithm allows for robustly determining multiple elastic constants without requiring guided wave mode identification. Additionally, it is a generalized approach applicable to laminated composites with various anisotropic lamina properties and layups.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

With the merits of high strength-to-weight ratio, corrosion resistance, and durability, carbon fiber reinforced polymer (CFRP) composites are increasingly used in civil, aerospace, marine, and automobile structures1,2. In practice, the mechanical properties of manufactured composites often exhibit batch-to-batch variations due to inevitable differences in resin curing, fiber misalignment, porosity, and other factors3,4,5,6. Studies have shown that fiber kinking can reduce the elastic modulus of unidirectional composites by approximately 15–25%3. Gutkin et al. revealed that localized fiber misalignment can cause a 30–50% reduction in compressive strength and shift the failure mode to shear-dominated mechanisms4. Hsiao et al. further reported that out-of-plane fiber waviness leads to a reduction in compressive fatigue life by more than 40%5. In addition to fiber misalignment, Stamopoulos et al. found that each 1% increase in porosity results in a 2–3% decrease in interlaminar shear strength6. Moreover, the mechanical properties may degrade due to complex service conditions, such as off-nominal loading, temperature fluctuations, and chemical exposure7,8,9. Hamzat et al. investigated stress distribution, damage evolution, and failure criteria of CFRP materials subjected to tensile, flexural, impact, and compressive loading7. Yang et al. reported that the tensile strength and elongation of CFRP plates at 90 °C decreased by approximately 90% compared to specimens tested at 10 °C8. Li et al. found that the marine environments significantly reduce the tensile strength and elastic modulus of CFRP in the fiber direction, with further degradation observed as temperature increases9. Therefore, nondestructive methods that can characterize the elasticity matrix are critical for both the quality control of composites during production and the assessment of material degradation after service. The measured elasticity matrix is also useful for further evaluating the structural stiffness, as well as modeling and evaluating the mechanical behaviors of the entire composite structures10,11.

Among various nondestructive evaluation techniques for composites, such as methods based on ultrasonic bulk waves12, ultrasonic guided waves10,11, electromechanical impedance13, infrared imaging14, optical fiber sensing15, and microwaves16, the ultrasonic guided wave-based methods have garnered increasing interest in recent years because of their multiple appealing features such as long propagation distances and high sensitivity to various types of defects such as fiber breaking, matrix cracking, and internal delamination. Moreover, guided waves are sensitive to the changes in elastic constants, as their characteristic equation and dispersion relations (e.g., wavenumber versus frequency relations for different modes) solved from the characteristic equation depend on the material’s elastic constants. This feature leads to multiple approaches for solving an inverse problem, i.e., using experimentally acquired guided wave signals to determine the material’s elastic constants.

While solving such inverse problems for laminated composites still requires more attention, studies on using guided waves to characterize material properties of isotropic specimens can be traced back decades. Xu and Mal17 introduced an inversion scheme to determine the material properties of adhesive bonds using guided wave phase velocities. Karim et al.18 developed an inversion approach for evaluating the elastic properties of an adhesive layer between aluminum plates. Rogers19 presented a least square-based method to analyze guided wave phase velocities to determine the elastic properties of different isotropic materials including aluminum, steel, and glass. Leveraging the acoustic microscopy-based measurement of high-order Lamb waves and dispersion analysis, Lyu et al.20 developed an inversion method for identifying elastic properties and demonstrated their method by evaluating a 380 μm thick submerged aluminum plate.

For anisotropic laminated CFRP composites, the increase of independent elastic unknowns expands the domain dimension for solving the inverse problem, and this brings great challenges to nondestructively characterizing the elastic constants of composites. The approaches for solving such complex inverse problems rely on a good understanding of their related forward models. For example, the traditional Thomson-Haskell model and its modifications21,22,23, which consider anisotropic elastic properties, can be used to construct objective functions of the inverse problems. Based on a modified Thomson-Haskell model, Hosten et al.24 established an inversion approach to evaluate the elastic properties of glass/carbon fibers reinforced epoxy matrix composites. Vishnuvardhan et al.25 characterized the elastic constants of orthotropic plates by using a single-transmitter-multiple-receiver array to measure guided wave velocities and then applying a GA-based inversion approach. Recently, Bochud et al.26 presented a real-time method for the assessment of an anisotropic plate’s elastic constants by using a multi-element linear array to acquire guided waves and then solving the inverse problem. Their method formulated an objective function based on the characteristic equation to account for different guided wave modes. To address the challenge of solving the inverse problems for complex waveguides with arbitrary cross-sections or anisotropic material properties, Cui et al.27 present a method using the semi-analytical finite element (SAFE) method to obtain phase velocity dispersion curves for different cases and then identifying the dispersion curves that matched the data of a simulation-based pseudo-experiment for verification. Sun et al.28 alternatively utilized the Legendre orthogonal polynomial expansion (LOPE)-based forward model to calculate the phase velocity dispersion curves for functional graded materials and then identified the best-matching dispersion curves for their pseudo-experimental data. In addition to characterizing the elastic constants, Li et al.29 solved the inverse problem for characterizing the initial stress in a CFRP composite by introducing a deep neural network-based guided wave analysis method.

With key features such as high spatial resolution, great flexibility in moving excitation and sensing locations, and noncontact ability to generate and receive guided waves, laser-based technologies are gaining increasing attention30,31,32. An increasing number of studies have been leveraging laser technologies not only for fundamental investigations of elastic wave propagation and wave-defect interaction but also for application studies on detecting various types of defects such as cracks, delamination, and corrosion33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43. Ambroziński et al.34 showed that scanning points from a laser Doppler vibrometer (LDV) could efficiently form phased arrays with different configurations to detect defects in plate-like structures. Kudela et al.35 devised a hybrid system that combined a piezoelectric transducer and a scanning LDV to capture wavefields and detect delamination damage in composites. Hudson et al.36 combined an air-coupled transducer and a scanning LDV to establish a fully non-contact system for evaluating voids in composites. Yu and Tian37 leveraged a scanning LDV to capture the time–space wavefields of Lamb waves, enabling the analysis of wavenumber changes for crack detection. Moll et al.38 investigated a high-density circular array for detecting cracks of various orientations in an aluminum plate by employing a hybrid setup that utilized a piezoelectric transducer and a scanning LDV for Lamb wave generation and acquisition, respectively. Radzieński et al.39 demonstrated the potential of a hybrid system integrating piezoelectric transducers and a scanning LDV for identifying defects in various types of composite plates. To overcome the time-consuming nature of full-field laser scanning of large areas with high spatial sampling rates, Jeon et al.40 presented a compressive sensing-based, full-field laser scanning approach that could reduce the number of required laser scanning points. Ullah et al.41 proposed a deep learning-based super-resolution method to enhance the efficiency of scanning LDV-based wavefield acquisition. Gao et al.42 leveraged laser ultrasonics to measure Lamb wave velocities at a series of frequencies, and by finding the theoretical dispersion curves matching the experimental data, they determined the thickness and Young’s modulus of a metal plate.

Despite aforementioned studies on laser technologies for ultrasonic guided wave-based nondestructive evaluation, this paper presents a guided wave-based inversion approach, which leverages noncontact laser Doppler vibrometry, frequency-wavenumber analysis, and a unique LOPE-based inversion algorithm, for enabling elastic constants determination for laminated composites. To develop our inversion algorithm, the LOPE is used to formulate a forward model that can use lamina material properties and layups of laminated composites to calculate the frequency-wavenumber dispersion relations of guided waves propagating in different directions of composites. Then, the LOPE-based forward model is used to establish a LOPE-based objective function that can be solved by multi-objective optimization algorithms, such as GA, which is known for its robustness in solving multi-parameter inverse problems. It is worth noting that the LOPE-based inversion algorithm allows for robustly determining multiple elastic constants without requiring guided wave mode identification. Moreover, the algorithm is a generalized approach applicable to laminated composites with various anisotropic lamina properties and layups. In addition, the elastic constants characterization approach proposed in this study, combining laser vibrometry with LOPE-based inversion, provides an alternative framework that does not rely on finite element discretization. This contrasts with prior methods44,45,46, which first discretize composite structures using finite elements and subsequently employ the SAFE method to construct forward models for dispersion curve computation and to define objective functions for inversion.

To implement our elastic constants characterization approach, a piezoelectric transducer bonded on a laminated composite plate generates omnidirectional guided waves, and an LDV acquires a time–space wavefield of the generated guided waves in our approach. Through the multi-dimensional Fourier transform, the acquired time–space wavefield is transformed into a frequency-wavenumber spectrum, which contains the frequency-wavenumber dispersion relations for guided waves propagating in different directions of the laminated composite plate. The experimentally acquired frequency-wavenumber relations are further used to inversely determine the composite’s elastic constants with the help of our LOPE-based inversion algorithm. To validate our inversion approach, we performed both a simulation-based pseudo-experiment and a laser vibrometry experiment. Frequency-wavenumber spectra corresponding to simulated and experimental wavefields were used as inputs of the inversion algorithm to determine the elastic constants. The results demonstrate the effectiveness of our approach for precisely determining the elastic constants of laminated composites.

Results

Inversion framework for determining elastic constants

To determine the elastic constants of laminated composites, this study presents an inversion framework. First, a time–space wavefield of omnidirectional guided waves is acquired using laser Doppler vibrometry. Next, the time–space wavefield is transformed into a frequency-wavenumber spectrum. From this spectrum, the main frequency-wavenumber components for different wave propagation directions can be identified. Finally, an inversion algorithm uses the experimental frequency-wavenumber relations as inputs to determine the elastic constants. The inversion algorithm takes advantage of a LOPE-based forward model, which uses material properties to determine frequency-wavenumber dispersion relations, and the GA optimization. Particularly, our inversion algorithm doesn’t need to perform mode identification and can directly use experimentally obtained frequency-wavenumber relations for different guided wave modes as inputs.

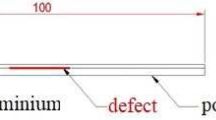

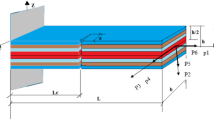

The guided wave characteristic equation can be used to obtain guided wave frequency-wavenumber dispersion relations based on the waveguide properties (e.g., elasticity matrix, density, lamina thickness, and layup). The derivation of a guided wave characteristic equation leveraging LOPE is presented below. Figure 1 shows a schematic of a laminated composite plate composed of unidirectional fiber reinforced polymer laminae with different orientations in a Cartesian coordinate system \({o-x}_{1}{x}_{2}{x}_{3}\), i.e., a global coordinate system with the origin \(o\) set at a point on the plate’s top surface. The Cartesian coordinate system \({o}{\prime}-{x}_{1}{\prime}{x}_{2}{\prime}{x}_{3}{\prime}\) is a local system for showing the principal symmetry axes of a lamina. Note that \({x}_{3}{\prime}\) and \({x}_{3}\) axes are in the same direction.

A schematic of a laminated CFRP composite plate. The Cartesian coordinate system \({o-x}_{1}{x}_{2}{x}_{3}\) is a global coordinate system for the composite plate. The Cartesian coordinate system \({o}{\prime}-{x}_{1}{\prime}{x}_{2}{\prime}{x}_{3}{\prime}\) is a local system showing the crystallographic axes of a lamina. \({x}_{3}{\prime}\) and \({x}_{3}\) axes are in the same direction.

As the material properties of a composite with N laminae may change in the x3-direction, the density \(\rho\) and elastic constants \({c}_{IJ}^{G}\) (with I, J = 1, 2, 3, ⋯, 6) of the elasticity matrix \({C}^{G}\) are depth-dependent. Hence, they can be mathematically expressed as functions of \({x}_{3}\),

where \({\rho }^{n}\) and \({c}_{IJ}^{G,n}\) \(\left(n=\text{1,2},3,\cdots ,N\right)\) are the density and elastic constants of the nth lamina. The elasticity matrix \({C}^{G,n}\) for the nth lamina in the global coordinate system \({o-x}_{1}{x}_{2}{x}_{3}\) can be obtained through the transformation of the lamina’s elasticity matrix \(C\) for the local coordinate system \({o}{\prime}-{x}_{1}{\prime}{x}_{2}{\prime}{x}_{3}{\prime}\) using a matrix rotation process as

where

and

with c12 = c13, c22 = c33, and c55 = c66. \(\text{X}\left({\varphi }_{n}\right)\) in Eq. (3) is a transformation matrix. The symbol ‘T’ denotes transpose operation. \({\varphi }_{n}\left(n=\text{1,2},3,\cdots ,N\right)\) is the angle from \({x}_{1}\) to \({x}_{1}{\prime}\) axes for the nth lamina, as illustrated in Fig. 1. Note that Eqs. (1) and (2) use a rectangular window function expressed as

where the depth \({d}_{n}\) equals to \(\sum_{1}^{n}{h}_{n}\). \({h}_{n}\) is the thickness of the nth lamina. Through the introduction of the rectangular window function, the variations of material properties in the composite’s thickness direction can be considered, and the properties become zero in regions outside the top and bottom surfaces of the composite plate. Moreover, the stress-free boundary conditions of the top and bottom surfaces are satisfied automatically.

The derivation of the guided wave characteristic equation needs to fuse the equation of motion, stress–strain constitutive equation, strain–displacement relation, and general wave displacement solution. Without considering the body force, the equation of motion for an elastic material can be expressed as47,48,49:

where \({\sigma }_{ij}\) (i, j = 1, 2, 3) and \({u}_{i}\) are stress tensor and displacement components. The stress–strain relation for a laminated composite can be written in the following form47,48,49:

where \({\varepsilon }_{ij}\) is the strain tensor component. With the small deformation assumption, the relationship between strain and displacement is47,48,49:

For guided waves propagating in the \({x}_{1}\)-direction, the general harmonic solutions of wave displacements \({u}_{1}\), \({u}_{2}\) and \({u}_{3}\) in \({x}_{1}\)-, \({x}_{2}\)-, and \({x}_{3}\)-directions can be expressed as49,50:

where \(k\) is the wavenumber, \(\omega\) is the angular frequency, and \({U}_{i}\left({x}_{3}\right)\) represent the wave mode shape displacement in the direction of \({x}_{i}\). In this study, the function \({U}_{i}\left({x}_{3}\right)\) is expanded using complete and orthogonal Legendre polynomials as

where \({p}_{m}^{i}(i=\text{1,2},3)\) is the expansion coefficient, and \({Q}_{m}({x}_{3})\) is a normalized mth-order Legendre polynomial

where \({P}_{m}({x}_{3})\) represents the mth-order Legendre polynomial, and \({d}_{N}\) is the composite plate’s thickness. Although the order \(m\) can run from 0 to \(\infty\), in practice, the order m is truncated at a finite value M that can be determined through convergence analysis49,50.

Substituting Eqs. (7–9) into Eq. (6), multiplying the derived equations by \({Q}_{j}^{*}({x}_{3})\) (j = 1, 2, 3, ⋯, M), and then integrating the equations over \({x}_{3}\) from 0 to \({d}_{N}\), we can obtain the following equation set

where \({A}_{\alpha \beta }^{j,m}\) \((\alpha ,\beta =\text{1,2},3)\) and \({B}_{m}^{j}\) are coefficients. The non-zero solutions of Eq. (14) can only exist when the determinant of the coefficient matrix for \({p}_{m}^{i}\) equals zero, expressed as

where \(\mathbf{\varphi }\) and \(\mathbf{h}\) are vectors with all the lamina angles and thicknesses, respectively. This formula is the LOPE-based characteristic equation for guided waves propagating in the \({x}_{1}\)-direction, i.e., the \(\theta\)= 0º direction in the global system \({o-x}_{1}{x}_{2}{x}_{3}\). For guided waves propagating in a direction of \(\theta\) ≠ 0º, by changing the transformation matrix in Eq. (3) to \(\text{X}\left({\varphi }_{n}-\theta \right)\), we can obtain the characteristic equation with \(\theta\) as an input, expressed as

By solving the characteristic equation using a numerical root-finding strategy with the lamina’s elasticity matrix C, density ρ, layup angle \(\mathbf{\varphi }\), and thickness \(\mathbf{h}\) as inputs, we can obtain the wavenumber-frequency dispersion relationships for guided waves propagating in the \(\theta\)-direction51. This LOPE-based forward model has been validated, and its solved guided wave dispersion relations agree well with those obtained using the global matrix method. Interested readers are referred to reference52 for more details.

When solving the characteristic equation, the truncation order M is critical, as M affects the accuracy using Legendre polynomials to approximate the guided wave mode shape displacements expressed by Eqs. (10–12), thus affecting the accuracy of dispersion curve solving. Typically, a convergence analysis needs to be performed to determine the truncation order M that leads to sufficient accuracy. An example study is performed to show the convergence with respect to the increase of M, by solving the dispersion curves for a 3-ply T300/914 (see Table 1 for lamina material properties) composite plate with a layup of [0]3. Figure 2 shows phase velocities of S0 and A0 modes propagating in the \(\theta\)=0° direction at five different frequencies including 200, 250, 300, 350, and 400 kHz. With the increase of the truncation order M from 2 to 10, the phase velocity for each mode asymptotically converges to a constant velocity. Moreover, by comparing Fig. 2a and b, it can be found that the A0 mode converges slower than the S0 mode, indicating mode-dependent convergence. Based on the convergence analysis results in Fig. 2, a truncation order M = 7 is selected for obtaining guided wave dispersion curves with sufficient accuracy. It is also used for the GA optimization-based inversion method presented below.

Through laser Doppler vibrometry-based time–space wavefield acquisition and multi-dimensional Fourier transform37, the experimental frequency-wavenumber relations (i.e., a collection of Q vectors denoted as \({\{[{\omega }_{q}^{in},{k}_{q}^{in},{\theta }_{q}^{in}]\}}_{Q}\)) for guided waves propagating in different directions can be obtained. There should exist theoretical frequency-wavenumber relations that best match the experimental data, and the composite’s lamina elasticity matrix Copt used for solving the best matching theoretical relations can be considered as the inversion result. The inverse problem of using experimentally obtained data \({\{[{\omega }_{q}^{in},{k}_{q}^{in},{\theta }_{q}^{in}]\}}_{Q}\) to determine the lamina elasticity matrix Copt can mathematically be described by

Here, the objective function is based on forward model, i.e., Eq. (16) describing the guided wave dispersion relation, derived by the LOPE method. Different from solving the frequency-wavenumber-direction relations using the forward model in Eq. (16), the LOPE-based inverse problem described in Eq. (17) is to find the optimal lamina elasticity matrix Copt such that \(\sum_{q=1}^{Q}{F}_{obj}\left({\omega }_{q}^{in},{k}_{q}^{in},{\theta }_{q}^{in}|{m}^{in},C,{\rho }^{in},{\mathbf{\varphi }}^{in},{\mathbf{h}}^{in}\right)\) is minimized, where \({\omega }_{q}^{in}\), \({k}_{q}^{in}\), \({\theta }_{q}^{in}\), \({\rho }^{in}\), \({\mathbf{\varphi }}^{in}\), and \({\mathbf{h}}^{in}\) are inputs for this objective function.

To solve Eq. (17), the GA based on probabilistic optimization is adopted. GA is an optimization method that searches for the optimal solution by simulating the natural selection and genetic mechanisms described in Darwin’s theory of biological evolution. Particularly, it is suitable for finding optimal solutions of discontinuous functions, can automatically adjust the search direction, and has inherent implicit parallelism. Moreover, it is capable of escaping local optima, enabling it to capture the global optimum in a multi-dimensional search space53,54,55. GA optimization is typically carried out through a series of processes, including binary encoding, fitness evaluation, probabilistic crossover, and mutation. The key GA parameters used in this study are listed in Table 2. Due to the inherent randomness of GA, it is preferable to perform multiple GA runs and use the averaged inversion results. Additional details about the GA approach can be found in references53,54,55. The GA optimization is performed in MatlabR2021a installed on a computing platform with an Intel i5-8300 h CPU (2.3–4.0 GHz, 16G RAM). To solve the inverse problem for the CFRP composites used in this study, the convergence to a global solution can be achieved in 40 evolutions.

To validate the inversion approach, we conducted both finite element simulation-based pseudo-experiments and a laser vibrometry experiment to acquire time–space wavefields u3(t, x1, x2) of guided waves in laminates with different layups, layer counts, and material properties. The pseudo-experiments were performed for unidirectional [0]3, unidirectional [0]4, cross-ply [0/90]s, and complex 8-ply [0/45/90/45]s laminates. The laser vibrometry experiment was conducted on an 8-ply [0/45/90/45]s laminate. Details of the laser vibrometry experiment are provided in the Materials and Methods section and Fig. 3. From the acquired time–space wavefields of guided waves, vectors \([{\omega }_{q}^{in},{k}_{q}^{in},{\theta }_{q}^{in}] (q=\text{1,2},3,\cdots ,Q)\) were obtained through wavefield processing (see Materials and Methods and Fig. 4 for details) and then used as inputs for the inverse approach for determining the lamina’s elastic constants. The inversion results are compared to their corresponding specific values (i.e., input elastic constants for the finite element simulation, as well as specific properties of laser-scanned composites) for analyzing the effectiveness of the inversion approach.

Validation with pseudo-experimental data

When using the pseudo-experimental data for the unidirectional [0]3 laminate as the input of the inverse problem, the obtained lamina elastic constants (c11, c12 = c13, c22 = c33, c23, c44, and c55 = c66) at different generations of the GA optimization are plotted in Fig. 5. Comparing the plots for different elastic constants, it is obvious that the speeds for finding their global optima using the GA approach are different for different elastic constants. The optimization process in Fig. 5 has 3 stages. Before the 10th generation, the GA performs randomization-based solution searching to efficiently cover a large searching space, and the GA solutions of elastic constants at this stage lack clear convergence trends. At the second stage from the 11th to the 34th generation, the GA solutions gradually show convergence trends. Note that Fig. 5 also reveals that the convergence rates for different elastic constants are different. At the third stage after the 35th generation, the GA solutions of all the elastic constants show clear convergence, indicating that the global optimal solutions of the lamina’s elastic constants are found. To obtain the results in Fig. 5, only the fundamental A0 mode was used. The input dataset of the inverse algorithm considers N = 7 frequencies and M = 2 wave propagation directions (75º and 130º). The wavenumbers for all the frequency-direction combinations are extracted from the spectrum SD(f, k, θ), and this leads to Q = 14 input vectors \([{\omega }_{q}^{in},{k}_{q}^{in},{\theta }_{q}^{in}]\), where are then used as the inputs of the inverse problem described in Eq. (17) for determining elastic constants.

Table 3 gives the inversion results with absolute and relative errors for the 3-ply unidirectional [0]3 laminate. It can be found that the inversion results are close to the input elastic constants used for the finite element simulation. All the relative errors are smaller than 4%, indicating that our inversion approach, which fuses the guided wave characteristic equation, frequency-wavenumber analysis, and GA optimization, can determine the lamina elastic constants with good accuracies for the FE-modeled laminated CFRP composites. Tables 4 and 5 present the inversion results of our proposed method for unidirectional [0]4 and cross-ply symmetric [0/90]S laminates, respectively. These results fairly match those of an existing method in reference44, demonstrating the capability of our approach for the inverse determination of multiple elastic constants. It is worth noting that, compared to the method in reference44, our approach circumvents the need for explicit identification of the measured guided wave modes from the acquired wave signals. Instead, it directly utilizes frequency–wavenumber pairs, making the method easier to use and more robust for practical inversion scenarios. Additionally, the inversion results in Table 6 (middle column) for a thicker 8-ply CFRP composite with a more complex layup [0/45/90/45]s also show good agreement with the simulation’s input elastic constants. The results of these four different composites validate the effectiveness of our approach in determining the elastic constants of composites with varying configurations, such as different layer counts and layup sequences.

The size of the input frequency-wavenumber dataset affects the convergence speed and accuracy of the inversion approach. To investigate this, we used different numbers of input frequency-wavenumber pairs (ranging from 10 to 16) obtained from the numerical data of the finite element simulation. From the inversion results in Table 7, it can be found that with the increase of data size from 10 to 16, the mean error decreases from 5.29 to 3.66%. When the data sizes are 10 and 12, the relative error for the component c12 exceeds 10%. When increasing the data size to 14 and 16, the relative error falls below 10%. Therefore, a data size of 14 or more is recommended for the 8-ply [0/45/90/45]s CFRP composite. Note that this recommended data size may vary for composites with different configurations, such as layups and layer counts. This is because our inversion method uses the LOPE-based guided wave characteristic equation, which is related to the composite’s parameters, such as layup and lamina count. Additionally, the frequency range of the input dataset can also impact inversion performance, since guided waves exhibit dispersive behavior with nonlinear frequency–wavenumber relationships, unlike bulk elastic waves with linear frequency-wavenumber relations. In future work, we will continue to investigate the effects of composite configurations and input data selection on the performance of the inversion approach.

Validation with laser vibrometry data

In addition to using simulation data for validating our inversion approach, we also used laser vibrometry data for an 8-ply [0/45/90/45]s CFRP composite plate (see Materials and Methods for experimental details). The LDV acquired time–space wavefield u3(t, x1, x2) in the scanning area is transformed to a frequency-space wavefield U3(f, x1, x2), by applying one-dimensional Fourier transform to reveal the frequency information. From the frequency-space wavefield in Fig. 6a, it can be seen that the generated guided waves have noncircular wavefronts indicating different phase velocities in different directions of the laminated CFRP composite. By further applying two-dimensional Fourier transform to change x1- and x2-axes to k1- and k2-axes, the frequency-space wavefield is transformed to a frequency-wavenumber spectrum S(f, k1, k2) in Fig. 6b. This spectrum shows tilted-oval-like high-intensity regions at different frequencies, revealing the main frequency-wavenumber components of guided waves generated in the CFRP composite plate. From this spectrum, we can identify the wavenumber that has the maximum spectrum intensity for a specific frequency and a specific wave propagation direction, as illustrated in Fig. 6b. Accordingly, for a series of frequencies fn (n = 1, 2, 3, ⋯, N) and a series of propagation directions θm (m = 1, 2, 3, ⋯, M), there are a total of \(Q=MN\) wavenumbers kn,m. Then we can further obtain vectors \([{\omega }_{q}^{in},{k}_{q}^{in},{\theta }_{q}^{in}] (q=\text{1,2},3,\cdots ,Q)\) using relations \({k}_{q=\left(n-1\right)M+m}^{in}={k}_{n,m}\), \({\omega }_{q=\left(n-1\right)M+m}^{in}={2\pi f}_{n}\), and \({\theta }_{q=\left(n-1\right)M+m}^{in}={\theta }_{m}\). In this study, we considered the fundamental A0 mode, N = 7 frequencies including 80, 90, 100, 110, 120, 130, and 140 kHz, as well as M = 2 propagation directions including 75º and 130º. The corresponding \(Q\)=14 vectors are used as inputs for the inversion problem in Eq. (17) for determining the lamina elastic constants for the 8-ply CFRP composite.

Results of the inversion approach when using the laser vibrometry data. (a) Frequency-space wavefield U3(f, x1, x2) obtained through one-dimensional Fourier transform of the experimentally acquired time–space wavefield u3(f, x1, x2). (b) Frequency-wavenumber spectrum S(f, k1, k2) obtained through two-dimensional Fourier transform of the frequency-space wavefield U3(f, x1, x2). The red solid curves are wavenumber contours obtained by solving the LOPE-based guided wave characteristic equation with elastic constants determined through our inversion approach, i.e., elastic constants at the last generation of the GA optimization. (c) Determined elastic constants for different generations of the GA optimization.

Figure 6c shows the calculated lamina elastic constants (c11, c12 = c13, c22 = c33, c23, c44, and c55 = c66) at different generations of the GA optimization. It can be seen that the elastic constants gradually converge during the GA optimization process from the 1st to the 40th generation. To evaluate the accuracy of our inversion approach, Table 6 compares the lamina elastic constants determined by our inversion approach to the specified properties of the CFRP lamina. The elastic constant c11 has a specific value of 132 GPa, while the GA-determined result using the experimental guided wave data is 129.91 GPa, yielding an absolute error of 2.09 GPa and a relative error of 1.58%. We also calculated the absolute and relative errors for other elastic constants. The relative errors for c12 = c13, c22 = c33, c23, c44, and c55 = c66 are 8.25, 1.20, 12.39, 1.03, and 5.63%, respectively, indicating a reasonable level of accuracy. Note that the average error of the inversion using experimental data is 5.01%, which is slightly higher than the 3.89% average error obtained from the inversion using numerical data. This difference may be attributed to experimental uncertainties and signal noise. Overall, the inversion results in Table 6 validate the effectiveness of our inverse method, which leverages the guided wave characteristic equation, GA optimization, noncontact laser vibrometry, and frequency-wavenumber analysis, for determining multiple elastic constants of anisotropic composites.

Discussion

Characterizing the elastic constants of laminated composites nondestructively is critical for material certification after manufacturing and degradation evaluation after service. This study presents a guided wave-based inversion approach for determining the 6 elastic constants (including c11, c12 = c13, c22 = c33, c23, c44, and c55 = c66) of the fiber-reinforced polymer lamina in a laminated composite. Our approach takes advantage of multiple key techniques, including noncontact laser Doppler vibrometry for acquiring the time–space wavefield of ultrasonic guided waves, frequency-wavenumber analysis for extracting main frequency-wavenumber components from the experimental data, as well as an inversion algorithm that fuses a generalized LOPE-based asymptotic objective function and GA optimization. Differing from previous studies45,46, which discretized the composites using finite elements, formulated SAFE-based forward models for dispersion curve solving, and then established SAFE-based inversion algorithms, our LOPE-based inversion algorithm is an alternative route bypassing finite element discretization.

This study’s elastic constants characterization approach offers multiple appealing features. First, our LOPE-based inversion algorithm, which uses a unique LOPE-based asymptotic objective function, is a generalized approach applicable to laminated composites with various anisotropic lamina properties and layups. Second, compared to previous methods using piezoelectric sensor arrays attached to the specimen surface25,26, our approach uses noncontact laser Doppler vibrometry, allowing for freely customizing the sensing locations for acquiring guided waves, achieving high spatial sampling resolutions to meet the Nyquist sampling requirement for high-frequency small-wavelength guided waves, as well as performing two-dimensional scanning to obtain a full time–space wavefield of omnidirectional guide waves. Third, our approach uses the full time–space wavefield (e.g., u3(t, x1, x2)) and leverages frequency-wavenumber analysis to reveal the frequency-wavenumber spectrum S(f, k1, k2). However, if only acquiring and using guided waves propagating in one direction (e.g., u3(t, x1)), the energy skew effect37,51 of guided waves in anisotropic composites can introduce errors in extracting the frequency-wavenumber information. Fourth, our inversion approach directly utilizes a set of frequency–wavenumber pairs as input, without requiring explicit identification of the guided wave modes present in the acquired signals. In addition, as the GA method is based on probabilistic optimization, it is suitable for discontinuous objective functions and allows for adaptive adjustment of search direction to robustly obtain the global optima for multiple elastic constants.

Our inverse approach has been successfully validated with simulation-based pseudo-experimental data for composites with different configurations, including unidirectional [0]3, unidirectional [0]4, cross-ply [0/90]s, and complex 8-ply [0/45/90/45]s laminates. It has also been demonstrated with laser vibrometry data for an 8-ply [0/45/90/45]s composite. The lamina elastic constants determined by our inverse approach agree with their benchmark values with reasonable errors, validating the effectiveness of our guided wave-based inverse approach for the nondestructive characterization of anisotropic lamina’s elastic constants, for laminated composites with different layups and layer counts. Given this success, our work is still subject to multiple limitations. First, the accuracy of measuring guided waves through laser vibrometry is influenced by the material’s optical properties (e.g., optical reflection and diffraction properties). Second, the used LOPE model is based on the assumptions of uniform fiber distribution and ideal lamina interface, thereby not considering the commonly existing uneven fiber distribution and potential interlaminar defects in actual laminated materials. Additionally, service conditions such as temperature and humidity, which could induce changes in guided wave signals7,8,9,56, are not considered in this study. In future work, we plan to conduct both numerical and experimental studies to evaluate whether our approach can be applied to characterize materials in various environmental conditions. We also plan to develop software with a user-friendly graphical interface for the LOPE-based inversion method, so that researchers and engineers without extensive computational backgrounds can quickly adopt it. We expect this study to inspire researchers and engineers to develop future noncontact, nondestructive characterization techniques for anisotropic materials for civil, aerospace, marine, and automobile applications.

Materials and methods

Finite element modeling-based pseudo-experiment

To validate our inversion approach for determining elastic constants, finite element simulation using ABAQUS was performed to obtain pseudo-experimental data, which was used as the input for the inverse problem in Eq. (17). The finite element model is for a laminated CFRP (T300/914 with properties in Table 1) composite plate with dimensions of 500 mm × 500 mm × 0.9 mm and a layup of [0]3. In-phase (or out-of-phase) out-of-plane point loads are applied to the plate’s top and bottom surface nodes at the same in-plane position for generating the antisymmetric A0 mode (or the symmetric S0 mode). The excitation signal is a 5-cycle 260 kHz tone burst modulated by a Hanning window. To reduce boundary reflections, our model includes an absorbing layer with gradient Rayleigh damping coefficients and a width twice the wavelength of the generated guided waves. More details about how to design an absorbing layer can be found in a previous study57.

To simulate guided waves with the numerical model, an explicit dynamic analysis is performed. The element length \(l\) is set to 0.5 mm to ensure a minimum of eight elements per wavelength for sufficient simulation accuracy. The simulation uses a fixed time step of 0.029 \(\mu s\), smaller than \(0.8l/{c}_{max}\) where \({c}_{max}\) is the largest possible wave speed, for ensuring the stability of explicit marching57,58. Through the explicit dynamic analysis, guided waves in the composite plate are simulated, and then the out-of-plane displacement signals at a series of surface nodes (with a spatial sampling resolution of 0.5 mm) are extracted to obtain a time–space wavefield denoted as u3(t, x1, x2). From this wavefield, the frequency-wavenumber information of the generated guided waves is further obtained, and this information can be used as the input for the inverse problem described by Eq. (17).

Laser doppler vibrometry experiment

To validate our inversion approach, a laser vibrometry experiment was performed to obtain experimental data. Figure 3 shows a schematic of the experimental setup. A piezoelectric wafer (PZT wafer) with a diameter of 7 mm and a thickness of 0.2 mm is surface bonded at the center of an 8-ply CFRP composite plate with a layup of [0/45/90/45]s and dimensions of 610 mm × 610 mm × 2.54 mm. For guided wave generation, the PZT wafer’s excitation signal is a 3-cycle tone burst with a center frequency of 120 kHz, generated by a function generator (model: Tektronix 3022C) and then boosted to 30 V by a voltage amplifier (model: HSA 4052). A laser Doppler vibrometer (model: ViboFlex, Polytec) is used to acquire the out-of-plane displacement signals of the generated guided waves. The laser vibrometer’s frequency bandwidth is set to 1 MHz, its displacement sensing range is set to 20 nm, and the acquired guided wave signal is filtered by a high-pass filter to remove noises below 8 kHz. The laser beam from the LDV is perpendicular to the composite plate for acquiring only the out-of-plane displacement component, based on the Doppler effect. Moreover, the LDV laser head is installed on a high-resolution, three-dimensional (3D) linear motion stage for automatically moving the laser spot to different positions, for acquiring guided waves at a series of points on a two-dimensional grid in a confined scanning area (45 mm \(\times\) 45 mm). The center of the scanning area coincides with the PZT wafer’s center. The spatial sampling resolutions in the x1 and x2 directions are both 0.1 mm. Through point-by-point measurements using the LDV for all the scanning points, our approach can acquire a time–space wavefield u3(t, x1, x2), which contains the out-of-plane displacement signals of guided waves acquired at all the scanning points.

Wavefield processing

Figure 4 illustrates the procedures for processing the experimentally or numerically acquired time–space wavefield u3(t, x1, x2) to obtain inputs for the inverse problem described in Eq. (17). First, using the multi-dimensional Fourier transform, the time–space wavefield u3(t, x1, x2) is transformed to a frequency-wavenumber spectrum denoted as S(f, k1, k2). More details of the transformation from the time–space domain to the frequency-wavenumber domain can be found in previous studies37,59,60,61. Second, the spectrum S(f, k1, k2) is changed to a representation SD(f, k, θ), which is a function of frequency f, wavenumber k, and wave propagation direction θ, by using the relation SD(f, k, θ) = S(f, k1 = kcosθ, k2 = ksinθ). In the spectrum SD(f, k, θ), regions with high intensities can reveal the frequency-wavenumber components of guided waves propagating in different directions. Third, by identifying all the high-intensity regions, we can obtain \({\{[{\omega }_{q}^{in}=2\pi {f}_{q}^{in},{k}_{q}^{in},{\theta }_{q}^{in}]\}}_{Q}\), a collection of vectors \([{\omega }_{q}^{in},{k}_{q}^{in},{\theta }_{q}^{in}] (q=\text{1,2},3,\cdots ,Q)\). This collection of vectors can be used as the input for the inverse problem described in Eq. (17) for inversely determining the elastic constants of the composite material.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article. Further information is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Goh, G. D., Yap, Y. L., Agarwala, S. & Yeong, W. Y. Recent progress in additive manufacturing of fiber reinforced polymer composite. Adv. Mater. Technol. 4(1), 1800271 (2019).

Hwang, D. & Cho, D. Fiber aspect ratio effect on mechanical and thermal properties of carbon fiber/ABS composites via extrusion and long fiber thermoplastic processes. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 80, 335–344 (2019).

Jensen, H. M. & Christoffersen, J. Kink band formation in fiber reinforced materials. J. Mech. Phys. Solids 45(7), 1121–1136 (1997).

Gutkin, R., Pinho, S. T., Robinson, P. & Curtis, P. T. On the transition from shear-driven fibre compressive failure to fibre kinking in notched CFRP laminates under longitudinal compression. Compos. Sci. Technol. 70(8), 1223–1231 (2010).

Hsiao, H. M., Daniel, I. M. & Wooh, S. C. Effect of fiber waviness on the compressive behavior of thick composites. Am Soc Mech Eng, AMD 196, 141–159 (1994).

Stamopoulos, A. G., Tserpes, K. I., Prucha, P. & Vavrik, D. Evaluation of porosity effects on the mechanical properties of carbon fiber-reinforced plastic unidirectional laminates by X-ray computed tomography and mechanical testing. J. Compos. Mater. 50(15), 2087–2098 (2016).

Hamzat, A. K., Murad, M. S., Adediran, I. A., Asmatulu, E. & Asmatulu, R. Fiber-reinforced composites for aerospace, energy, and marine applications: An insight into failure mechanisms under chemical, thermal, oxidative, and mechanical load conditions. Adv. Compos. Hybrid Mater. 8(1), 1–57 (2025).

Yang, Y., Jiang, Y., Liang, H., Yin, X. & Huang, Y. Study on tensile properties of CFRP plates under elevated temperature exposure. Materials 12(12), 1995 (2019).

Li, X., Zhang, X., Chen, J., Huang, L. & Lyu, Y. Effect of marine environment on the mechanical properties degradation and long-term creep failure of CFRP. Mater. Today Commun. 31, 103834 (2022).

Mei, H. & Giurgiutiu, V. Guided wave excitation and propagation in damped composite plates. Struct. Health. Monit. 18(3), 690–714 (2019).

Gresil, M. & Giurgiutiu, V. Prediction of attenuated guided waves propagation in carbon fiber composites using Rayleigh damping model. J. Intell. Mater. Syst. Struct. 26(16), 2151–2169 (2015).

Balasubramaniam, K. & Rao, N. S. Inversion of composite material elastic constants from ultrasonic bulk wave phase velocity data using genetic algorithms. Compos. B 29(2), 171–180 (1998).

Pitchford, C., Grisso, B.L. & Inman, D.J Impedance-based structural health monitoring of wind turbine blades. In Health Monitoring of Structural and Biological Systems 2007, SPIE 6532: 508–518. (2007)

Jumel, J., Taillade, F. & Lepoutre, F. Microscopic thermo-elastic properties characterization by photothermal microscopy. In AIP Conference Proceedings, American Institute of Physics 615(1): 1110-1117 (2002)

Krebber, K., Habel, W., Gutmann, T. & Schram, C. Fiber Bragg grating sensors for monitoring of wind turbine blades. In 17th International Conference on Optical Fibre Sensors, SPIE 5855: 1036–1039 (2005).

Kharkovsky, S. & Zoughi, R. Microwave and millimeter wave nondestructive testing and evaluation: Overview and recent advances. IEEE Instrum. Meas. Mag. 10(2), 26–38 (2007).

Xu, P. C., Mal, A. K. & Bar-Cohen, Y. Inversion of leaky Lamb wave data to determine cohesive properties of bonds. Int. J. Eng. Sci. 28(4), 331–346 (1990).

Karim, M. R., Mal, A. K. & Bar-Cohen, Y. Inversion of leaky Lamb wave data by simplex algorithm. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 88(1), 482–491 (1990).

Rogers, W. P. Elastic property measurement using Rayleigh-Lamb waves. Res. Nondestr. Eval. 6(4), 185–208 (1995).

Lyu, Y. et al. Elastic properties inversion of an isotropic plate by hybrid particle swarm-based-simulated annealing optimization technique from leaky lamb wave measurements using acoustic microscopy. J. Nondestr. Eval. 33(4), 651–662 (2014).

Schmidt, H. & Jensen, F. B. A full wave solution for propagation in multilayered viscoelastic media with application to Gaussian beam reflection at fluid–solid interfaces. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 77(3), 813–825 (1985).

Nayfeh, A. H. The general problem of elastic wave propagation in multilayered anisotropic media. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 89(4), 1521–1531 (1991).

Hosten, B. & Castaings, M. Transfer matrix of multilayered absorbing and anisotropic media. Measurements and simulations of ultrasonic wave propagation through composite materials. J Acoust Soc Am. 94(3), 1488–1495 (1993).

Hosten, B., Castaings, M., Tretout, H. & Voillaume, H. Identification of composite materials elastic moduli from Lamb wave velocities measured with single sided, contactless ultrasonic method. In AIP Conference Proceedings, American Institute of Physics 557(1): 1023-1030 (2001)

Vishnuvardhan, J., Krishnamurthy, C. V. & Balasubramaniam, K. Genetic algorithm based reconstruction of the elastic moduli of orthotropic plates using anultrasonic guided wave single-transmitter-multiple-receiver SHM array. Smart Mater. Struct. 16(5), 1639 (2007).

Bochud, N., Laurent, J., Bruno, F., Royer, D. & Prada, C. Towards real-time assessment of anisotropic plate properties using elastic guided waves. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 143(2), 1138–1147 (2018).

Cui, R. & di Scalea, F. L. On the identification of the elastic properties of composites by ultrasonic guided waves and optimization algorithm. Compos. Struct. 223, 110969 (2019).

Sun, K., Hong, K., Yuan, L., Shen, Z. & Ni, X. Inversion of functional graded materials elastic properties from ultrasonic lamb wave phase velocity data using genetic algorithm. J. Nondestr. Eval. 33, 34–42 (2014).

Li, X., Liu, H., Chen, X., Lyu, Y. & Liu, Z. Inverse of initial stress in carbon fiber reinforced polymer laminates using lamb waves and deep neural network. Ultrasonics 132, 107005 (2023).

Rothberg, S. J. et al. An international review of laser Doppler vibrometry: Making light work of vibration measurement. Opt. Lasers Eng. 99, 11–22 (2017).

Staszewski, W. J., Lee, B. C. & Traynor, R. Fatigue crack detection in metallic structures with Lamb waves and 3D laser vibrometry. Meas. Sci. Technol. 18(3), 727 (2007).

Majhi, S., Mukherjee, A., George, N. V., Karaganov, V. & Uy, B. Corrosion monitoring in steel bars using Laser ultrasonic guided waves and advanced signal processing. Mech. Syst. Signal. Process. 149, 107176 (2021).

Sampath, S. & Sohn, H. Non-contact microcrack detection via nonlinear Lamb wave mixing and laser line arrays. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 237, 107769 (2023).

Ambroziński, Ł, Stepinski, T. & Uhl, T. Efficient tool for designing 2D phased arrays in lamb waves imaging of isotropic structures. J. Intell. Mater. Syst. Struct. 26(17), 2283–2294 (2015).

Kudela, P., Wandowski, T., Malinowski, P. & Ostachowicz, W. Application of scanning laser Doppler vibrometry for delamination detection in composite structures. Opt. Lasers Eng. 99, 46–57 (2017).

Hudson, T. B., Hou, T. H., Grimsley, B. W. & Yuan, F. G. Imaging of local porosity/voids using a fully non-contact air-coupled transducer and laser Doppler vibrometer system. Struct. Health Monit. 16(2), 164–173 (2017).

Yu, L. & Tian, Z. Lamb wave structural health monitoring using a hybrid PZT-laser vibrometer approach. Struct. Health Monit. 12(5–6), 469–483 (2013).

Moll, J., De Marchi, L., Kexel, C. & Marzani, A. High resolution defect imaging in guided waves inspections by dispersion compensation and nonlinear data fusion. Acta Acust. Acust. 103(6), 941–949 (2017).

Radzieński, M., Kudela, P., Marzani, A., De Marchi, L. & Ostachowicz, W. Damage identification in various types of composite plates using guided waves excited by a piezoelectric transducer and measured by a laser vibrometer. Sensors 19(9), 1958 (2019).

Jeon, J. Y., Miao, Y., Park, G. & Flynn, E. Compressive laser scanning with full steady state wavefield for structural damage detection. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 169, 108626 (2022).

Ullah, S., Kudela, P. & Ostachowicz, W. A deep learning based super-resolution approach for the reconstruction of full wavefields of lamb waves. In 50th Annual Review of Progress in Quantitative Nondestructive Evaluation, American Society of Mechanical Engineers 87202: V001T04A002 (2023).

Gao, W., Glorieux, C. & Thoen, J. Laser ultrasonic study of Lamb waves: Determination of the thickness and velocities of a thin plate. Int. J. Eng. Sci. 41(2), 219–228 (2003).

Rizzo, P. & Enshaeian, A. Challenges in bridge health monitoring: A review. Sensors 21(13), 4336 (2021).

Eremin, A. A., Glushkov, E. V., Glushkova, N. V. & Lammering, R. Evaluation of effective elastic properties of layered composite fiber-reinforced plastic plates by piezoelectrically induced guided waves and laser Doppler vibrometry. Compos. Struct. 125, 449–458 (2015).

Kudela, P., Radzienski, M., Fiborek, P. & Wandowski, T. Elastic constants identification of fibre-reinforced composites by using guided wave dispersion curves and genetic algorithm for improved simulations. Compos. Struct. 272, 114178 (2021).

Orta, A. H., Kersemans, M., Roozen, N. B. & Van Den Abeele, K. Characterization of the full complex-valued stiffness tensor of orthotropic viscoelastic plates using 3D guided wavefield data. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 191, 110146 (2023).

Rose, J. L. Ultrasonic guided waves in solid media (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2014).

Nayfeh, A. H. & Chimenti, D. Free wave propagation in plates of general anisotropic media. J. Appl. Mech. 56(4), 881–886 (1989).

He, C., Liu, H., Liu, Z. & Wu, B. The propagation of coupled Lamb waves in multilayered arbitrary anisotropic composite laminates. J. Sound Vib. 332(26), 7243–7256 (2013).

Liu, H., Liu, S., Chen, X., Lyu, Y. & Liu, Z. Coupled Lamb waves propagation along the direction of non-principal symmetry axes in pre-stressed anisotropic composite lamina. Wave Motion 97, 102591 (2020).

Wang, L. & Yuan, F. G. Group velocity and characteristic wave curves of Lamb waves in composites: Modeling and experiments. Compos. Sci. Technol. 67(7–8), 1370–1384 (2007).

Liu, H. et al. Investigation of viscoelastic guided wave properties in anisotropic laminated composites using a Legendre orthogonal polynomials expansion-assisted viscoelastodynamic model. Polymers 16(12), 1638 (2024).

Goldberg, D. E. Genetic algorithm in search, optimization, and machine learning (Addison-Wesley, Boston, 1989).

Sivanandam, S. N. & Deepa, S. N. Introduction to genetic algorithms (Springer, Berlin, 2008).

Whitley, D. A genetic algorithm tutorial. Stat. Comput. 4, 65–85 (1994).

Croxford, A. J., Moll, J., Wilcox, P. D. & Michaels, J. E. Efficient temperature compensation strategies for guided wave structural health monitoring. Ultrasonics 50(4–5), 517–528 (2010).

Liu, H., Chen, X., Michaels, J. E., Michaels, T. E. & He, C. Incremental scattering of the A0 Lamb wave mode from a notch emanating from a through-hole. Ultrasonics 91, 220–230 (2019).

Lowe, M. J. S., Alleyne, D. N. & Cawley, P. The mode conversion of a guided wave by a part-circumferential notch in a pipe. J. Appl. Mech. 65(3), 649–656 (1998).

Alleyne, D. & Cawley, P. A two-dimensional Fourier transform method for the measurement of propagating multimode signals. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 89(3), 1159–1168 (1991).

Tao, C., Zhang, C., Ji, H. & Qiu, J. Fatigue damage characterization for composite laminates using deep learning and laser ultrasonic. Compos. B 216, 108816 (2021).

Marzani, A. & De Marchi, L. Characterization of the elastic moduli in composite plates via dispersive guided waves data and genetic algorithms. J. Intell. Mater. Syst. Struct. 24(17), 2135–2147 (2013).

Funding

H. L. acknowledges the support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 52175513, 51705325).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.L. conceived the idea and performed simulations and experiments. L.W. and X.L. contributed to the finite element simulations. Z.T. and C.Q. contributed to the laser vibrometry experiment. H.L., L.W., and X.L. analyzed the data. H.L., L.S., Z.L, and Z.T. wrote the paper. All authors reviewed the manuscript. Z.L. and Z.T. supervised the study.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

All the authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, H., Wang, L., Li, X. et al. Elastic constants identification for laminated composites using laser doppler vibrometry and an inversion method based on legendre orthogonal polynomial expansion. Sci Rep 15, 27578 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-12700-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-12700-5