Abstract

The goal of this effort was to create mesoporous nanoparticles (MSNs) decorated with amine groups and loaded with liraglutide (LRT) for oral delivery. Amine-decorated MSNs were helpful for peptide entrapment and prolonged release of liraglutide, a GLP-1 analog. Liraglutide-loaded MSNs were made by using acetonitrile and water sol-gel techniques. Over the course of 24 h, the particles provided consistent drug release, with cumulative release reaching up to 90% in vitro. Differential dynamic light scattering, scanning electron microscopy (SEM), Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy, Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) analysis and differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) were used to characterize the synthesized formulation. The MTT assay was used to evaluate cell viability along with the hemolysis assay and was found to be safe. Particle size determination was performed by a zeta sizer; the size was 286 nm \(\:\pm\:17\), and the PDI and zeta potential were 0.29 and +8.89 mV, respectively. The drug entrapment efficiency was also very good at 56% ± 9%, and the drug release was more than 90.0% ± 9 within 24 h at all pH values tested. The efficacy of the particles was examined in a rat model of diabetes and contrasted with that of a group that received daily injections of liraglutide. Between 0 and 5 days after the start of treatment, lower blood sugar levels were observed in the particle treatment groups than in the injection groups. Overall, the liraglutide-loaded MSNs created in this work are effective in a rat model of diabetes, and as a result, we believe that they have great potential for clinical application.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Liraglutide (LRT) is a strong biologic medication used for the treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus. With the introduction of the medicine in the European Union in 2009 and in the United States in 2010, Novo Nordisk began marketing it as a therapy for obese people with comorbidities1,2. Produced by recombinant technology in yeast, Liraglutide is a GLP-1 counterpart with 97% sequence homology to human GLP-1 (Perry, 2011). Because of its low solubility in water, it is often injected in a solution containing sodium dihydrogen phosphate and 1,2-propanediol, and the recommended daily allowance is 1.8 mg1. Such daily injection causes significant patient discomfort, and thus, there is a need to develop a pharmaceutical strategy to extend the release period and reduce the frequency of injections. To solve this problem, scholars have explored a range of sustained release systems for proteins. A pharmacological strategy to lengthen the release duration and minimize the frequency of injections is needed since patients experience severe discomfort from such frequent injectable application. Scholars have investigated several protein sustained release techniques in an attempt to address this issue. Insulin-loaded poly (alkylcyanoacrylate) nanoparticles were successfully generated from microemulsions, and their release of the medication was prolonged for up to 36 h3,4. Insulin-loaded polymeric micelles were created and presented as effective potential carriers for insulin release in another study. Achieving effective oral administration is also challenging, particularly for peptide drugs, which have extremely low bioavailability5. Insulin-loaded polymeric micelles were prepared, which they proposed to be effective candidate carriers for insulin release6. To combat this issue, scientists have attempted to use a wide range of techniques, including micronization, complexation, lipid-based formulations, cosolvents, salt creation, solid dispersions, and nanoformulations7,8. Among the abovementioned techniques, nanocarriers are widely investigated by scientists and include drug nanocystals9,10,11, nanoemulsions12,13,14, polymeric micelles15,16, nanoparticles17,18, nanotubes17, and silica-based nanocarriers19. In the recent past, scientists have shown keen interest in mesoporous silica nanoparticles (MSNs) since they possess biocompatible features such as nontoxicity, effective cellular uptake, the possibility for drug loading, and manageable drug discharge20,21,22.

Drug delivery in the form of nanocapsules provides protection for fragile polypeptides and can shield cargo from the harsh environment of the gastrointestinal tract {Xu, 2024 #61}. Mesoporous silica nanoparticles (MSNs) are positively charged polymer materials with the ability to bypass cell pathways to some extent and can also adsorb to the surface of negatively charged epithelial cells, thereby promoting drug absorption; this makes MSNs superior to most carrier materials in oral delivery applications23. In the recent past, scientists have shown keen interest in mesoporous silica nanoparticles (MSNs) since they possess biocompatible features such as nontoxicity, effective cellular uptake, the possibility for drug loading and manageable drug discharge20,21,24. These favorable features make MSNs promising contenders for numerous uses, including drug delivery7,25.

Preparing MSNs with larger pores was a primary goal. We used a variety of tools to characterize the physicochemical features of nanoparticles, including particle size, zeta potential, polydispersity index (PDI), loading efficiency, structural confirmation, and safety. Drug release and in vitro toxicity studies were also conducted. At physiological pH, the resulting MSNs have a net negative charge. Postsynthesis grafting with amine-containing silane 3-aminopropyltriethoxysilane (APTES) was used to create cationic MSNs for the purpose of investigating the influence of the silica surface charge on protein encapsulation.

Materials and methods

Chemicals

The alkoxide precursor tetraethyl orthosilicate (TEOS 99.9%) and surfactant cetyltrimethyl-ammonium bromide (CTAB, 99.0%; Product code A0805) were both supplied by Dae-Jung Korea of Siheung-si, Korea. The chemical 3-aminopropyl triethoxysilane (APTES) (Sigma-Aldrich-281778) was also sourced from Dae-Jung Korea in Siheung-si, Korea. The 99.5% pure liraglutide (LRT) was generously supplied by Saffron Pharmaceutical Pvt. Ltd. of Faisalabad, Pakistan. The acetonitrile (98%) utilized here was supplied by Dae-Jung Chemicals of Siheung-si, Korea. All of the other chemicals were considered analytical grade.

Preparation of liraglutide-loaded MSNs

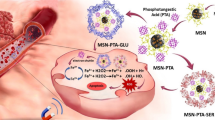

Modifications were made to the sol-gel technique in an oil/water phase as reported by Nandiyanto et al.26,27 with a few minor changes. To begin, a 100 mL solution of deionized water and acetonitrile was prepared by dissolving 500 mg of cetyltrimethylammonium bromide (CTAB) in a 1:1 volume ratio. Under constant stirring at 1500 revolutions per minute (rpm), the solution was heated to 35 °C and kept at that temperature. By adding 0.5 M potassium hydroxide (KOH) solution dropwise, the mixture’s pH was brought to around 9.0. An inert environment was maintained and homogenization was aided by continually bubbling nitrogen gas through the solution during the procedure. Then, while stirring continuously, 5 mL of tetraethyl orthosilicate (TEOS) was added dropwise until the liquid was clear and homogenous. With the addition of TEOS, the condensation and hydrolysis reactions were set in motion. The solution became opaque within a few minutes (15 minuts), which signifies that silica nanoparticles had nucleated and were growing, as well as that the silica gel network had formed. The mixture was allowed to react further under a nitrogen atmosphere to complete the condensation process after the white gel appeared. A 0.2 µ membrane filter was employed to remove large aggregates and any unreacted components from the resulting gel. Following the filtering process, the gel was extensively rinsed with deionized water to remove any remaining surfactant or by-products. After letting the solid material air dry for 24 h at room temperature, it was milled into a fine powder. The dry powder was subjected to a 6-hour calcination process in a muffle furnace set at 500 °C in order to eliminate the surfactant template (CTAB). Mesoporous silica nanoparticles (MSN) were the official name for the finished product.

To accomplish amino functionalization, 3-aminopropyltriethoxysilane (APTES) was used. The three-necked flask was placed in a dry nitrogen atmosphere, and 50 mL of MSNs (2 mg/mL) was added. Subsequently, 2.0 mL of aqueous APTES solution (100 µL/mL) was injected into the aqueous MSN suspension, and the mixture was refluxed at 77 °C under nitrogen with magnetic stirring for 24 h. The final product was dried at 90 °C for 12 h after being filtered and washed three times with ethanol. It was decided to use the same stirring and soaking adsorption process for LRT loading that has previously been published28,29. LRT was dissolved in methanol to produce a 1 mg/mL concentrated solution. Then, a 1:1 (w/w) drug-silica mixture of MSNs and LRT was created. After being steeped for three days, this liquid was mixed for three hours. After that, the surface-bound LRT was washed off the particles by filtering them through a membrane filter (0.1 micron size) and washing them three times in 100 ml of methanol. The samples were air-dried overnight at room temperature before being vacuum-dried at 50 °C. These laden particles were termed MSN-LRT. We have shown full process in Fig. 1 for loading and preparation.

Drug-entrapment efficiency and drug loading

One hundred milligrams of particles were mixed with 100 mL of methanol for one hour to assess the MSN concentration. In this methid we have centrifuged the solution for 10 min and collected the supernatant for HPLC method. HPLC (Shimadzu LC 20 A, 1000 pump, 2500 UV‒VIS detector (Japan) and Agela C18 column (250 mm X 4.6 mm X 5 m)) was used to extract LRT, and the amount of LRT was measured at 272 nm by computing the area under the curve. The mobile phase was composed of ammonium acetate buffer, methanol and acetonitrile at a ratio of 20:40:40 (%v/v), and its flow rate was maintained at 1.0 mL/min. Twenty microliters of analyte was injected three times, and the peaks produced were compared to those of the standard. It was determined how much drug to use and how effective it was by (1) (2).

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM)

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images were taken with a VEGA3 microscope (VEGA3, TESCAN Country) to examine the morphology of MSN-LRT. To transmit the MSN-LRT from each sample, clean glass capillaries were used. After drying and gold plating the samples, micrographs were obtained at various positions on the grid. Atomic force microscopy (AFM) was also used to observe the roughness of the particle surface30,31.

Size and zeta potential measurements

To determine the particle size and zeta potential of MSN-LRT, a Zetasizer Nano ZS (Malvern, MALM1127001, UK) was used. Water was used as the dispersion in the preparation of suspensions at a concentration of 100 mg/mL. When adjusting the pH, only a few drops of 0.1 M HCL were needed. All readings were taken at room temperature (25 °C)32,33.

Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR)

With the use of an FTIR spectrometer (Nicolet IS7ATR-FTIR spectrometer, Thermo Scientific, USA), spectra of LRT, blank, and MSN-LRT were collected. (Lee, Lo, Mou, & Yang, 2008) FTIR spectra were collected at a resolution of 2 cm− 1 spanning the range of 500–4000 cm− 134,35.

Nitrogen – adsorption/desorption

The surface area, pore volume and size of MSN-LRT were calculated by N2 adsorption/desorption analysis (Micromeritics Gemini VII 2390 surface area analyzer V1.03 (V1.03 t)) operating at – 196.15 °C. Both samples were degassed at 200 °C for 24 h prior to analysis. The Barrett–Joyner–Halenda (BJH) model was applied to determine the pore size and pore volume distribution from desorption isotherms. The specific surface area (SSA) was calculated through the Brunauer‒Emmett‒Teller (BET) method using adsorption data at relative pressure (p/p°)36.

In vitro cell viability studies

In this study, we used HEPG2 cell line that were grown at the University of Lahore and received from the American Type Culture Collection in Manassas. At 37 °C in a humidified environment of 95% oxygen and 5% carbon dioxide, the cells were grown in DMEM supplemented with 10% bovine serum albumin (BSA). One day before incubation with MSNs, the cells were seeded at a density close to confluence. The MTT (3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide) test was used to quantify the mitochondrial activity of succinate dehydrogenase as an indicator of cell viability/proliferation. Each well was given 15 \(\:\mu\:l\) of MTT (5 mg/ml) in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and incubated at 37 °C for 24 h. After this, different concentrations of MSN-LRT (50, 100, 150, 200 and 400 \(\:\mu\:\)g/mL) were added to the cell media. Once the formazan crystals were formed, the media containing the MTT were removed, and the absorbance at 570 nm was measured. Using this approach, we were able to calculate the cell viability as a percentage (3):

In vitro hemolytic activity

A standard protocol for the hemolysis experiment was followed37,38. Rat blood was combined by gentle inversion of the tube and centrifuged at 4000 for 15 min. (Rat were purchased form university of Lahore animal section). After centrifuging at 4000 for 15 min, the plasma supernatant was discarded, and the erythrocytes were removed four times by suspending them in normal saline (0.9%). The 12-well plates utilized had flat bottoms. Pipetting was used to gently combine the MSN-LRT at concentrations of 50, 100, 150, and 200 mg/ml. The wells used as negative controls contained normal saline (NaCl 0.9%) (not shown in the graph), while the wells used as positive controls contained Triton-X 100 (0.1%)39. Spectrophotometric analysis at 540 nm was used to quantify the concentration of hemoglobin in the supernatant38. The experiment was performed in triplicate. The percent hemolysis was calculated by the following formula (4). All experimental protocols were approved by the RLCP Ethical Review Board IRB No (RLCP/101/2024), and they were carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki World Medical Association.

In vitro release study

In vitro studies of MSN-LRT and pure LRT were performed using the dialysis membrane technique. The MSN-LRT equivalent of 10 mg of LRT was diluted in 5 ml of distilled water and placed inside a dialysis bag (Spectrum Medical Industries, Houston, Texas, USA). By stapling the sack, a pouch was made. The dialysis bag was then placed in 500 ml of medium that was stirred at 50 rpm and maintained at 37 °C, and phosphate buffer with pH values of 7.4, 5.5, and 0.1 M HCl with a pH value of 1.2 was added for various periods. At regular intervals of up to 24 h, we removed 2.0 ml samples and replaced them with fresh medium of the same volume. The same method was adopted to study the pure LRT material (10 mg). The resulting filtrate was collected via a 0.45 \(\:\mu\:\) pore size filter and utilized for HPLC analysis after being diluted40. The percentage release was calculated by following Eq. (5)41,42:

Where:

-

Ct = Drug concentration at the current time point (e.g., in µg/mL).

-

V = Total volume of the release medium.

-

Ci = Drug concentration at previous sampling points.

-

Vs = Volume of the sample withdrawn at each time point.

-

Wtotal= Total amount of drug initially loaded (in µg or mg).

-

n = Number of samples taken up to time t.

Blood sugar measurement

On days 0, 1 and 5, we measured the glucose levels. After fasting for 12 h before each measurement, the rats were gavaged with 5 mL of brown sugar water containing 10% (w/v) brown sugar. Over a 6-hour period, blood glucose levels were monitored by taking readings from the tail vein at regular intervals. Other investigations have also followed a similar procedure. In this study, we compared MSN-LRT with LRT injection, which is available on the market.

Enzymatic degradation study

Stability analysis in the presence of pepsin and pancreatin was performed, and the results were compared between native LRT and MSN-LRT. Two milliliters of simulated gastric fluid (SGF; 3.2 g of pepsin, two grams of sodium chloride, seven milliliters of hydrochloric acid, mixed and diluted with water to one liter, pH = 1.2) or simulated intestinal fluid (SIF; ten grams of pancreatin, six and a half grams of potassium phosphate, mixed and adjusted with 0.2 N sodium hydroxide and diluted with water to one liter, pH = 6. Test Solutions (United States Pharmacopeia 42, National Formulary 42, 2012) were used to ensure that the SGF and SIF met all the requirements. Both the SGFsp and SIFsp native LRT stabilities were evaluated using the same methods. For 2 h, 750 L samples were taken at regular intervals, and then an equivalent volume of ice-cold reagent (0.1 M NaOH for SGF or 0.1 M HCl for SIF) was added to halt the enzymatic process. To determine the residual LRT, we centrifuged the samples at 16,500 g and 4 °C for 10 min and then examined the supernatant using HPLC. All the incubations were performed in triplicate. The LRT recoveries of the withdrawn wsamples were determined via the following Eq. (6):

Physical stability and microbial assessment

Accelerated stability experiments were conducted for 6 months on the prepared MSN-LRT (40 \(\:\pm\:\)2 °C/75 \(\:\pm\:\)5% RH) (Table 2). In the first, third, and sixth months, we ran a battery of physicochemical tests, such as drug entrapment, in vitro testing, and microbiological evaluations.

Analytical statistics

The statistical analysis was conducted in GraphPad Prism v.5 using one-way ANOVA and Tukey’s test. The data are presented as the mean and standard deviation (SD). A P value less than 0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance.

Results and discussion

Drug encapsulation and loading

After extracting LRT from MSN (ethanol and freshly prepared pH 7.4 phosphate buffer (USP), 30:70), the LRT-MSN was dissolved in buffer until all the LRT was dissolved, and then the mixture was sonicated for 15 min at room temperature. Using HPLC with a maximum wavelength of 272 nm, the quantity of LRT was determined by diluting the produced solution with the mobile phase (Fig. 2). The percentage of entrapped drugs was calculated by dividing the sample and standard values43. Our prior research detailed how we created MSN particles via the sol-gel technique. This method provided a good yield of silica particles, which were loaded with LRT (encapsulation efficiency of 56 \(\:\pm\:9\)%). These particles were subsequently used for further in vitro and in vivo characterization. We have also determined drug loading by using same HPLC method and found 46 \(\:\pm\:7\)%).

Microscopic analysis of MSN-LRT

Scanning electron microscopy was used to examine the morphology of the MSN-LRT particles. Figure 1A shows SEM images of MSN-LRT, which were subsequently validated by DLS findings (Fig. 3) to be spherical and uniform in size. SEM was used to confirm the mesoporous, organized structure of MSN-LRT. These pictures show the 2D hexagonal structure in an organized fashion (Fig. 4A). Chaing et al. generated MSNs in aqueous solution and reported the effects of the silica source, pH and reaction time on the structure and size. Chiang et al. (2011) reported that at high pH (up to 13), uniformly sized particles with an ordered structure were produced, while at low pH (9.5), nonordered particles were produced. Under basic circumstances, however, we obtained ordered particles at pH 9 by switching to a solvent composition of water to acetonitrile in a 1:1 ratio. The roughness of the particle surfaces was also measured using atomic force microscopy (AFM) (Fig. 4B)44. The particles appear to have a rough surface, which is indicative of the porous and loaded nature of the MSN-LRT particles45.

Dynamic light scattering

DLS was used to analyze the particle size, size distribution, and zeta potential of MSN-LRT, as described by Powers et al. (2006)46. The average particle size of MSN-LRT was 286 nm \(\:\pm\:17\), and its PDI and zeta potential were 0.29 and +8.89 mV, respectively (Fig. 3). Our SEM results, as described above, are supported by the fact that the PDI of the drug-loaded particles was low, indicating that they were all of similar size. The zeta potential also helps to determine the surface charge, stability and likely cellular contact with LRT-loaded particles. Cationic nanocarriers react more quickly with biological membranes than their negatively charged counterparts. In addition, particles with a charge are less likely to aggregate, which increases their stability. Thus, MSN-LRT is well suited for drug administration with little toxicity to biological membranes because of its optimal size, PDI, and charge. The zeta potential also helps to determine the surface charge, stability and likely cellular contact with LRT-loaded particles47 and further substantiates our SEM results, as mentioned in the above section.

FT-IR study

FT-IR investigations provided information concerning the identification of several chemical groups. The FT-IR spectra of the samples (LRT, MSNs and MSN-LRT) are displayed in Fig. 5. The spectral bands at 1053.78, 797.97, 3396.49, and 1636.88 cm-1 were identified as silicate absorption bands in MSNs. Si silicate absorption bands were observed at 962.07 cm-1, and Si-O-Si bending was observed at 1053.78 cm-148,49. Because of the wider peak at 3396.49 cm-1, silanol (Si-OH) symmetric stretching was identified50. LRT was also indicated by distinctive peaks at 1639.20 and 3530.09 cm-1 owing to N-H bending vibrations and for amides I and II, respectively. MSN-LRT was characterized by an FTIR spectrum with a distinctive peak at 1053 cm-1 due to Si-O-Si bending. The presence of the drug in the produced MSN-LRT was also indicated by distinctive peaks at 1637.20, 1507.89, and 1438.09 cm-1 owing to N-H bending vibrations, C = C-C aromatic ring stretching, and C-H asymmetric stretching, respectively.

Nitrogen adsorption/desorption studies

The surface area and pore size distribution of MSN-LRT were computed using the nitrogen adsorption technique and the Barrett‒Joyner‒Halenda (BJH) model, respectively. The specific surface area (BSSA) was determined using the Brunauer‒Emmett‒Teller (BET) method51. Furthermore, this high BSSA and pore volume indicate the potential of this material to host drug molecules for various drug delivery applications. The mesoporous nature of MSNs was demonstrated by their BSSA of 692.7 m2/g and pore size of 5.9 nm prior to drug loading (Figure not shown). The high BSSA and pore volume further suggest that it might host therapeutic molecules for use in a variety of drug delivery systems. As shown in Fig. 6, after BSSA loading, the pore size and surface area decreased to 571.8 m2/g and 4.9 nm, respectively. This reduction was ascribed to the loading of LRT in the pores. Our results are supported by a large body of research; for example, Zhang et al. (2010) loaded telmisartan in silica-based nanoparticles and reported a decrease in pore size and BSSA52.

DSC studies

The entrapment of LRT into MSN particles was studied using DSC. DSC analysis was also used to verify whether crystalline medication was present. Because the medication crystallizes in the pores, its concentration may be determined by measuring the decrease in the melting point. If the medication in the pores is in a noncrystalline condition, no melting point depression may be identified. If the drug in the pores is in a noncrystalline state, no melting point depression can be detected52,53,54. Figure 7 shows that the endothermic peak in the DSC curve of MSNs occurs at 35 °C, which is consistent with the inherent melting points of MSNs after dehydration and the removal of water. No other peak was observed at 250 °C, which indicates that stable MSNs were produced.

At the glass transition temperature (Tg), an endothermic peak appears at approximately 85 °C, which is due to its melting point. Another curve was shown near 200 °C, which is due to the full degradation of the peptides. In contrast, an endothermic peak, while faint and wide, develops in MSN-LRT at 125 °C, indicating that the drug is entrapped in a noncrystalline form within MSNs and is protected. It has been hypothesized that the partial amorphization of the MSN-LRT medication is due to its contact with the surface of the mesoporous nanoparticles, which are rich in groups of silica56,57. Moreover, the results indicated that LRT was entrapped within the MSN pores and was present in its genuine form.

In vitro studies

We examined the solubility characteristics of pure LRT and MSN-LRT in a USP buffer solution at pH 1.2, 5.5 and 7.4. MSN-LRT (equivalent to 10 mg of LRT) was dispersed in 900 mL of buffer to evaluate its in vitro release characteristics. After 24 h, the MSN-LRT sample was withdrawn.

Within 6 h, these MSNs-LRT released 18% (at pH 1.2), 19% (at pH 5.5) and 20% (at pH 7.4) of the medicine, and after 9–10 h, they released more than 40% of the drug. As shown in Fig. 8, MSNs serve as carriers and improve the dissolution profile of LRT in all types of release media. Several factors, including (a) the drug’s interaction with the carrier, (b) the presence of the drug in confined channels, and (c) the large surface area and pore size, contribute to the improved solubility and controlled release of the LRT. More than 90.0 \(\:\pm\:6\:\)% LRT was released from the MSNs over 24 h at all pH values tested. On the other hand, pure LRT was degraded at acidic pH, and Fig. 9 shows the release rate of LRT under acidic conditions over 5 h; after this, no absorbance was found due to peptide degradation in the acidic environment. The release profile of MSN-LRT was controlled in an acidic environment due to its protection. Only a few drugs are released from MSNs, and they are available in acidic environments. After 5 h, less than 20% of the LRT was released from the MSNs, and after 9 h, it reached 45%. Most of the literature reviews indicate that 2 h is the time in the stomach for drug availability, after which the drug will move toward the intestinal area where the pH is quite different from that of the stomach. Pure LRT was destroyed in acidic condition and due to its solubility in basic pH we can observed release rate in Fig. 9. In 5.5 pH and 7.4 pH pure LRT was dissolved within 5 h about 90%.

The particle size of LRT molecules is too large to trap peptides. It has been shown that reducing the particle size to the nanoscale range accelerates and controls the peptide release profile and improves the dissolution rate. Furthermore, the amorphous drug integrated in the pore channels had much smaller particle sizes (in the nanometer range) than did the pure crystalline drug. It has been proven that reducing the drug particle size to the nanoscale range more strongly controls drug release and, hence, improves the dissolution rate56.

In vitro cell viability studies

Researchers investigated whether 186 nm MSN-LRT was cytotoxic to human cell lines (Hep G2). Source is University of Lahore and received from the American Type Culture Collection in Manassas. The MTT test was used to determine the cell viability of the MSN-LRT. Over the course of 24 h, the cell line was exposed to MSN-LRT at a range of concentrations (50, 100, 150, 200, and 400 \(\:\mu\:g\)/ml). After the exposed MSN-LRT had been incubated for 24 h, 10 \(\:\mu\:l\) of MTT reagent was added to each well, and the plates were returned to the incubator for another 2 h. The positive and negative controls are also shown in the graph, which indicates significant results. The plates were examined using a bioreader at 570 nm after the incubation period ended. The results demonstrated that MSN-LRT was preserved and that the viability of the cell lines decreased proportionately with increasing concentrations of MSN-LRT, which indicated that this effect was dose dependent. At least 50 \(\:\mu\:g\)/ml was the lowest concentration, and 400 \(\:\mu\:g/\)ml was the highest concentration at which the cell viability was 89% and 55%, respectively, which is more than 50% viability. Figure 10 shows the cytotoxicity at various concentrations. High levels of cell viability were demonstrated by MSN-LRT in this study.

Hemolysis investigations

The compatibility of the MSN-LRT Nano formulation with blood was investigated through hemolytic analyses. The results of hemolytic analyses (Fig. 11) showed that MSN did not cause hemolysis after its administration at concentrations of 50, 100, 150, 200 and 400 \(\:\mu\:\)g/mL− 1, but negligible hemolysis was noted even at high concentrations, i.e., 400 mg mL− 1, and blood cells exhibited considerable tolerance to the complex. The results of the present study demonstrated that cell viability depended upon the concentration and that the cells were alive after incubation with MSN-LRT, which confirms blood compatibility.

In vivo blood glucose levels

For clinical use, it is crucial to determine the hypoglycemic impact of the ingestion of MSN-LRT. Therefore, we administered a series of in vivo tests in which rats were gavaged with sugar, and blood samples were obtained from the tail vein at regular intervals. Five days after the initial MSN-LRT treatment and injection, further experiments were conducted. All patterns were consistent across time periods, with a sharp increase in glucose levels between 0 and 1 h postsugar gavage for all groups. All metrics indicate a fairly similar capacity to reduce blood glucose levels across the MSN-LRT- and injection-treated groups. At 5 days into the dosing schedule, it appears that the injectable therapy lowered glucose levels somewhat quicker than the MSN-LRT, although the difference was not statistically significant. Changes in postgavage glucose levels were statistically identical between the MSN-LRT and injection groups on days 0, 1 and 5.

Enzymatic degradation study

After 2 h of incubation in SGF or SIF, only 3.92 \(\:\pm\:0.78\)% and 4.56 \(\:\pm\:0.89\)%, respectively, of the free LRT was recovered. This is obvious because peptides can break within enzymes, which is why it is difficult for peptides to cross the GIT. Incubation of LRT for 2 h in SIF resulted in full degradation (95.5\(\:\pm\:2.37\%\)), whereas incubation for 2 h in SGF resulted in only 3.92\(\:\pm\:\)0.55% recovery (Fig. 12). However, after 2 h of incubation in SGF and SIF, 93.97%, 1.59% and 89.45%, respectively, of LRT was stable when encapsulated within MSN particles. It has been suggested that MSNs can be used to encapsulate peptide medicines because of their stability and resistance to degradation. The encapsulation of LRT in MSN nanosystems could successfully protect the peptide from the harsh environment of the simulated conditions of the stomach with sustained release.

In vivo pharmacokinetics

The pharmacokinetic characteristics of both pure LRT and MSN-LRT, including the Cmax (ng/mL), tmax (Hrs), t1/2 (Hrs), AUC (0-t) (ng/mL.h), and z (l/h), were determined. From plasma levels in albino rats, a noncompartmental pharmacokinetic study was performed using the PK-Solver program. The values of several pharmacokinetic parameters of LRT and MSN-LRT are reported in Table 1; Fig. 13. These findings demonstrated an increase in the bioavailability of the medicine in the plasma of rats. This MSN-LRT formulation showed a controlled release pattern of LRT. MSN-LRT had a half-life (t1/2) for elimination of 13.10 \(\:\pm\:0.22\) (p 0.05), while the half-life for the pure medication was 9.96\(\:\pm\:\) 0.15. The concentration of MSN-LRT in the plasma increased over time, as shown in Fig. 12. The MSN-LRT group had a greater Cmax than the LRT group. Pure LRT was shown to have a lower AUC0-t value than MSN-LRT (400.50 \(\:\pm\:\) 4.49 ng/mL/h). MSN-LRT was also observed to have a greater AUC0-inf than LRT (290.28 \(\:\pm\:4.83\:\)ng/mL/h). These findings revealed that the improved bioavailability of the MSN-LRT formulation was the consequence of an improvement in drug solubility caused by amorphous loading in the carrier system.

Physical stability and microbial assessment

The total aerobic microbial count (TAMC) and stability of the MSN-LRT formulation were subsequently examined. For oral administration, MSN-LRT was designed with a limited microbial load, as required by the USP Pharmacopoeia. Six months of stability testing was conducted on MSN-LRT by maintaining it at 40 degrees Celsius in a stability chamber. All aspects of MSN-LRT, as well as their presentation, encapsulation, and testing, were evaluated on day one, after three months, and after six months. A patient-ready formulation of MSN-LRT requires full compliance with USP 4358. The test encapsulation and stability of the formulation were both determined to be quite high. A color shift or other anomaly did not occur throughout the assay, which showed a success rate of 90–110%. There was little to no change in encapsulation stability throughout that time frame.

The microbiological parameters of MSN-LRT were also checked. TAMC, TYMC, Staphylococcus, and Pseudomonas were examined in MSN-LRT for up to six months. To prepare the plates, Sabouraud dextrose agar and nutrient agar were used, as described by Ballal, N. V., et al.58. The plates were incubated in Memmert incubators for 72 h at TAMC and for seven days at different temperatures (32 \(^\circ\text{C}\:\pm\:2\:\) and 22\(^\circ\text{C}\:\pm\:2\:\)). The results shown in Table 2 are quite satisfactory until the 6th month.

Conclusion

The successful development of MSNs for increasing the oral bioavailability and dissolution of LRT was accomplished in the present investigation. Compared to the pure medication, the generated MSNs considerably accelerated the dissolution rate of LRT. The pores may foster the formation of LRT noncrystalline rock, which has a high disintegration rate in the medium and can be destroyed in the stomach due to the acidic environment. The entrapment of LRT in its amorphous form greatly impacted the pore size and pore volume. Both formats have similar first-order release profiles. Based on the results of the in vivo pharmacokinetic investigation, MSN-LRT is superior to pure LRT in terms of bioavailability. In the MTT experiment, MSN-LRT was found to be more biocompatible with HEP G2 cells than was the control. All of these findings point to the promise of MSNs as a new framework for less-than-ideal peptide medicines, and the results of these studies validate their major utility.

ARRIVE guidelines

The experimentation was conducted in accordance with applicable laws, and ARRIVE guidelines.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

References

Wu, J. et al. Liraglutide-loaded Poly (lactic-co-glycolic acid) microspheres: Preparation and in vivo evaluation. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 92, 28–38 (2016).

Pandey, A. & Goyal, A. K. Liraglutide innovations: a comprehensive review of patents (2014–2024). Pharm. Patent Analyst. 13 (1–3), 73–89 (2024).

Perry, C. M. Liraglutide Drugs, 71(17): 2347–2373. (2011).

Aimaretti, G. Liraglutide: a once-daily human glucagon-like peptide-1 analogue. J. Endocrinol. Investig. 32 (8), 701–703 (2009).

Graf, A., Rades, T. & Hook, S. M. Oral insulin delivery using nanoparticles based on microemulsions with different structure-types: optimisation and in vivo evaluation. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 37 (1), 53–61 (2009).

Jiang, G. et al. Preparation of multi-responsive micelles for controlled release of insulin. Colloid Polym. Sci. 293 (1), 209–215 (2015).

Leuner, C. & Dressman, J. Improving drug solubility for oral delivery using solid dispersions. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 50 (1), 47–60 (2000).

Bai, A. et al. Development of a Tin oxide carrier with mesoporous structure for improving the dissolution rate and oral relative bioavailability of Fenofibrate. Drug. Des. Devel. Ther. 12, p2129 (2018).

De Waard, H., Hinrichs, W. & Frijlink, H. A novel bottom–up process to produce drug nanocrystals: controlled crystallization during freeze-drying. J. Controlled Release. 128 (2), 179–183 (2008).

Li, W. et al. Preparation and in vitro/in vivo evaluation of Revaprazan hydrochloride nanosuspension. Int. J. Pharm. 408 (1), 157–162 (2011).

Wang, Y. et al. In vitro and in vivo evaluation of Silybin nanosuspensions for oral and intravenous delivery. Nanotechnology 21 (15), 155104 (2010).

Bali, V., Ali, M. & Ali, J. Novel nanoemulsion for minimizing variations in bioavailability of Ezetimibe. J. Drug Target. 18 (7), 506–519 (2010).

Silva, A. et al. Development of topical nanoemulsions containing the isoflavone genistein. Die Pharmazie-An Int. J. Pharm. Sci. 64 (1), 32–35 (2009).

Tagne, J. B. et al. A nanoemulsion formulation of Tamoxifen increases its efficacy in a breast cancer cell line. Mol. Pharm. 5 (2), 280–286 (2008).

Khemtong, C. et al. In vivo off-resonance saturation magnetic resonance imaging of αvβ3-targeted superparamagnetic nanoparticles. Cancer Res. 69 (4), 1651–1658 (2009).

Kim, T. H. et al. The delivery of doxorubicin to 3-D multicellular spheroids and tumors in a murine xenograft model using tumor-penetrating triblock polymeric micelles. Biomaterials 31 (28), 7386–7397 (2010).

Hughes, G. A. Nanostructure-mediated drug delivery, in Nanomedicine in Cancer. Pan Stanford. pp. 47–72. (2017).

Hans, M. & Lowman, A. Biodegradable nanoparticles for drug delivery and targeting. Curr. Opin. Solid State Mater. Sci. 6 (4), 319–327 (2002).

Bharti, C. et al. Mesoporous silica nanoparticles in target drug delivery system: A review. Int. J. Pharm. Invest. 5 (3), 124 (2015).

Maggini, L. et al. Breakable mesoporous silica nanoparticles for targeted drug delivery. Nanoscale 8 (13), 7240–7247 (2016).

Lin, W. et al. In vitro toxicity of silica nanoparticles in human lung cancer cells. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmcol. 217 (3), 252–259 (2006).

Bourang, S. et al. Application of nanoparticles in breast cancer treatment: a systematic review. Naunyn. Schmiedebergs Arch. Pharmacol. 397 (9), 6459–6505 (2024).

Tyagi, P., Pechenov, S. & Subramony, J. A. Oral peptide delivery: translational challenges due to physiological effects. J. Controlled Release. 287, 167–176 (2018).

Zhang, Y., Huang, C. & Xiong, R. Advanced materials for intracellular delivery of plant cells: strategies, mechanisms and applications. Mater. Sci. Engineering: R: Rep. 160, 100821 (2024).

Colilla, M., González, B. & Vallet-Regí, M. Mesoporous silica nanoparticles for the design of smart delivery nanodevices. Biomaterials Sci. 1 (2), 114–134 (2013).

Hench, L. L. & West, J. K. The sol-gel process. Chem. Rev. 90 (1), 33–72 (1990).

Ganesh, M. et al. Development of Duloxetine hydrochloride loaded mesoporous silica nanoparticles: characterizations and in vitro evaluation. AAPS PharmSciTech. 16 (4), 944–951 (2015).

Tu, J. et al. Mesoporous silica nanoparticles with large pores for the encapsulation and release of proteins. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 8 (47), 32211–32219 (2016).

Mehmood, Y. et al. Developing nanosuspension loaded with azelastine for potential nasal drug delivery: determination of Proinflammatory Interleukin IL-4 MRNA expression and industrial Scale-Up strategy. ACS Omega. 8 (26), 23812–23824 (2023).

Mehmood, Y. et al. Control synthesis of mesoporous silica microparticles: optimization and in vitro cytotoxicity studies. Pak. J. Pharm. Sci. 36 (3), 915–920 (2023).

Mehmood, Y. et al. Remdesivir nanosuspension for potential nasal drug delivery: determination of pro-inflammatory Interleukin IL-4 mRNA expression and industrial scale-up strategy. J. Nanopart. Res. 25 (7), 129 (2023).

Mehmood, Y. et al. Biopolymer based film loaded with cholecalciferol: A novel technique to enhance nutritional supplement absorbance. Pak. J. Pharm. Sci., 36. (2023).

Lee, C. H. et al. Synthesis and characterization of positive-charge functionalized mesoporous silica nanoparticles for oral drug delivery of an anti‐inflammatory drug. Adv. Funct. Mater. 18 (20), 3283–3292 (2008).

Mehmood, Y. et al. Amikacin-loaded Chitosan hydrogel film cross-linked with folic acid for wound healing application. Gels 9 (7), 551 (2023).

Zhao, Z. et al. Development of novel core-shell dual-mesoporous silica nanoparticles for the production of high bioavailable controlled-release Fenofibrate tablets. Drug Dev. Ind. Pharm. 42 (2), 199–208 (2016).

Nemmar, A. et al. Interaction of diesel exhaust particles with human, rat and mouse erythrocytes in vitro. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 29 (1–2), 163–170 (2012).

Lu, S. et al. Efficacy of simple short-term in vitro assays for predicting the potential of metal oxide nanoparticles to cause pulmonary inflammation. Environ. Health Perspect. 117 (2), 241–247 (2008).

Zubair, M. et al. GC/MS profiling, in vitro antioxidant, antimicrobial and haemolytic activities of Smilax macrophylla leaves. Arab. J. Chem. 10, S1460–S1468 (2017).

Zhang, Y. et al. DDSolver: an add-in program for modeling and comparison of drug dissolution profiles. AAPS J. 12 (3), 263–271 (2010).

Barkat, K. et al. Development and characterization of pH-responsive polyethylene glycol‐co‐poly (methacrylic acid) polymeric network system for colon target delivery of oxaliplatin: its acute oral toxicity study. Adv. Polym. Technol. 37 (6), 1806–1822 (2018).

Khalid, I. et al. Preparation and characterization of alginate-PVA-based semi-IPN: controlled release pH-responsive composites. Polym. Bull. 75 (3), 1075–1099 (2018).

Barkat, K. et al. Oxaliplatin-loaded crosslinked polymeric network of chondroitin sulfate‐co‐poly (methacrylic acid) for colorectal cancer: its toxicological evaluation. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 134 (38), 45312 (2017).

Chiang, Y. D. et al. Controlling particle size and structural properties of mesoporous silica nanoparticles using the Taguchi method. J. Phys. Chem. C. 115 (27), 13158–13165 (2011).

Morsi, R. E. & Mohamed, R. S. Nanostructured Mesoporous Silica: Influence of the Preparation Conditions on the physical-surface Properties for Efficient Organic Dye Uptake5p. 172021 (Royal Society open science, 2018). 3.

Powers, K. W. et al. Research strategies for safety evaluation of nanomaterials. Part VI. Characterization of nanoscale particles for toxicological evaluation. Toxicol. Sci. 90 (2), 296–303 (2006).

Masarudin, M. J. et al. Factors determining the stability, size distribution, and cellular accumulation of small, monodisperse Chitosan nanoparticles as candidate vectors for anticancer drug delivery: application to the passive encapsulation of [14 C]-doxorubicin. Nanatechnol. Sci. Appl. 8, 67 (2015).

Sevimli, F. & Yılmaz, A. Surface functionalization of SBA-15 particles for amoxicillin delivery. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 158, 281–291 (2012).

Liu, F. et al. Outside-in Stepwise functionalization of mesoporous silica nanocarriers for matrix type sustained release of fluoroquinolone drugs. J. Mater. Chem. B. 3 (10), 2206–2214 (2015).

Beganskienė, A. et al. FTIR, TEM and NMR investigations of Stöber silica nanoparticles. Mater. Sci. (Medžiagotyra). 10, 287–290 (2004).

Narayan, R. et al. Mesoporous silica nanoparticles: A comprehensive review on synthesis and recent advances. Pharmaceutics 10 (3), 118 (2018).

Zhang, Y. et al. Spherical mesoporous silica nanoparticles for loading and release of the poorly water-soluble drug Telmisartan. J. Controlled Release. 145 (3), 257–263 (2010).

Salonen, J. et al. Mesoporous silicon microparticles for oral drug delivery: loading and release of five model drugs. J. Controlled Release. 108 (2–3), 362–374 (2005).

Heikkilä, T. et al. Mesoporous silica material TUD-1 as a drug delivery system. Int. J. Pharm. 331 (1), 133–138 (2007).

Johnsen, H. M. et al. Stable snow lantern-like aggregates of silicon nanoparticles suitable as a drug delivery platform. Nanoscale 16 (20), 9899–9910 (2024).

Maleki, A. & Hamidi, M. Dissolution enhancement of a model poorly water-soluble drug, atorvastatin, with ordered mesoporous silica: comparison of MSF with SBA-15 as drug carriers. Expert Opin. Drug Deliv. 13 (2), 171–181 (2016).

Liu, S. et al. Porous nanomaterials for biosensing and related biological application in in vitro/vivo usability. Mater. Adv. 5 (2), 453–474 (2024).

Adriaensen, G. F., Lim, K. H., & Fokkens, W. J. (2017, August). Safety and efficacy of a bioabsorbable fluticasone propionate–eluting sinus dressing in postoperative management of endoscopic sinus surgery: a randomized clinical trial. In International forum of allergy & rhinology 7 (8), 813-820.

Ballal, N. et al. Susceptibility of Candida albicans and Enterococcus faecalis to chitosan, chlorhexidine gluconate and their combination in vitro. Australian Endodontic J. 35 (1), 29–33 (2009).

Acknowledgements

The authors extend their appreciation to the Deanship of Research and Graduate Studies at King Khalid University for funding this work through Large Research Project under grant number (RGP2/329/46) .

Funding

This was funded by Deanship of Research and Graduate Studies at King Khalid University through Large Research Project under grant number (RGP2/329/46).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, original draft writing, reviewing, and editing: Yasir Mehmood, Hira Shahid, Rida Siddique, Mohammed H AL Mughram. Formal analysis, investigations, funding acquisition, reviewing, and editing: Umar Farooq, Syeda Momena Rizvi, Mohammad N. Uddin. Resources, data validation, data curation, and supervision: Mohsin Kazi, Mohammed Bourhia, Fakhreldeen Dabiellil.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All experimental protocols were approved by the RLCP Ethical Review Board of Riphah International University Faisalabad, PO. Box 38000, Pakistan with IRB No (RLCP/101/2024), and they were carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki World Medical Association.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Mehmood, Y., Shahid, H., Siddique, R. et al. Design and fabrication of a mesoporous silica scaffold for oral delivery of peptides. Sci Rep 15, 29520 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-12728-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-12728-7