Abstract

The antioxidant properties of medicinal plants are often assessed using chemical assays; however, electrochemical techniques like cyclic voltammetry offer complementary insights. This study explores the antioxidant potential of crude ethanol extracts and solvent fractions from Ipomoea aquatica and Colocasia esculenta using both DPPH radical scavenging assay and electrochemical cyclic voltammetry. Phytochemical screening identified key secondary metabolites in both plants. Antioxidant activity was quantified using the DPPH assay, and electrochemical behavior was assessed by cyclic voltammetry to detect redox-active compounds. Phytochemical analysis revealed flavonoids, phenols, tannins, reducing sugars, and glycosides in both plants, while C. esculenta also contained terpenoids, alkaloids, and xanthoprotein. The DPPH assay showed IC50 values ranging from 41.80 to 188.15 µg/mL for I. aquatica and 35.55–170.84 µg/mL for C. esculenta. Cyclic voltammetry revealed characteristic electron transfer peaks, especially in Fraction 2 of I. aquatica and Fraction 3 of C. esculenta, indicating the presence of effective electron-donating antioxidants. Cyclic voltammetry successfully complemented traditional DPPH assays, offering a more nuanced understanding of antioxidant profiles. The combined approach highlights the potential application of these plants in food and pharmaceutical formulations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In recent years, interest in disease prevention has increased, especially concerning the impact of free radicals. The field of free radical biology and medicine is advancing rapidly due to its significant relevance to health, disease, and overall well-being1. The discovery of free radicals’ dates back over a century when it became apparent that these molecules played a key role in oxidation reactions involving organic compounds. In the 1950s, free radicals were identified in biological systems, and it was suggested that they contributed to several human health issues2.

The overproduction of free radicals, commonly known as oxidative stress (OS), has been connected to cell death and is linked to variety of chronic and degenerative disease. These conditions are a result of the overproduction of reactive oxygen and nitrogen species3. The body has its own natural defenses against free radicals in the form of antioxidants, which can be endogenous (produced within the body) or exogenous (obtained from external sources), or a combination of both. Endogenous antioxidants include enzymes like superoxide dismutase (SOD), catalase (CAT), glutathione peroxidase (GPx), and glutathione reductase (GRx), as well as non-enzymes such as lipoic acid, glutathione, L-arginine, uric acid, bilirubin, and various antioxidant nutrients4. Exogenous antioxidants, on the other hand, include substances like vitamin E, vitamin C, trace elements (selenium, copper, zinc, manganese), and phytochemicals such as isoflavones, polyphenols, and flavonoids, which must be obtained through the diet5.

Both endogenous and exogenous antioxidants are effective at neutralizing free radicals by donating electrons to reactive oxygen species (ROS), thereby reducing oxidative stress and the oxidation of cellular molecules6. Studies have also shown that endogenous and exogenous antioxidants can interact actively; for example, oral administration of vitamin E to humans has been found to significantly increase red blood cell glutathione levels, potentially through the stimulation of glutathione synthetase activity.

Antioxidants play a crucial role in delaying or preventing the oxidation of proteins, carbohydrates, lipids, and DNA, safeguarding cells from damage caused by free radicals. They disrupt the chain reaction initiated by free radicals by interacting with them before they can cause substantial harm to important molecules. Consequently, antioxidants themselves become oxidized and may need to be replenished or regenerated. Antioxidant enzymes present within cells facilitate the breakdown of various free radical species. Additionally, transition metal binding proteins help prevent the interaction of transition metals, such as iron and copper, with hydrogen peroxide and superoxide, thereby preventing the generation of highly reactive hydroxyl radicals7.

Recent research has shown that natural antioxidants can serve as effective therapeutic agents against ROS, potentially preventing conditions associated with oxidative stress8. Previous studies have also indicated that polyphenols, which are widely distributed in medicinal plants, vegetables, and fruits, possess strong scavenging abilities against oxygen and nitrogen radicals9.

Numerous spectrophotometric methods have been employed to assess the in vitro antioxidant activity, including ABTS (3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid), DPPH (1,1-diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl), and ORAC (Oxygen radical absorbance capacity), which measure the ability of antioxidants to scavenge radicals. Additionally, methods like FRAP (Ferric reducing antioxidant power), CUPRAC (Cupric reducing antioxidant capacity), and CERAC (Cerium reducing antioxidant capacity) evaluate the antioxidant’s capacity to reduce metals, while TBARS (Thiobarbituric acid reactive substances) assess lipid peroxidation inhibition10.

Electroanalytical method- cyclic voltammetry is employed to gauge the effectiveness of antioxidants in addition to the conventional free-radical scavenging approach. When evaluating antioxidant performance, cyclic voltammetry (CV), an efficient, uncomplicated, and cost-effective electrochemical technique, can serve as a viable alternative to traditional spectrophotometric methods. This study suggests that the overall antioxidant capacity is determined by two parameters: the peak anodic current (Ip.a.), which is directly related to sample’s concentration and strength, and the peak anodic potential (Ep.a.), which characterizes the antioxidant properties. When conducting cyclic voltammetry on organic solvent extracts from various seasonal vegetables’ leafy portions at different scan rates11observed peak anodic current in the extract serves as an indicator of antioxidant capacity, with the magnitude of the current reflecting the strength of the antioxidant. This is because cyclic voltammetry has the capability to define the electrochemical behavior of certain compounds based on their oxidation/reduction potential12. Blood plasma, vegetable oils, milk, orange juice, wines, and winemaking byproducts have all been successfully tested for their antioxidant capacity using CV, and it has also been utilized to correlate the analytical response to the phenolic content13. Therefore, it can be anticipated that cyclic voltammetry will be an easy tool for identifying antioxidants and calculating the antioxidant activity of meals and therapeutic plants.

In conclusion, this study explores the assessment of antioxidant activity through cyclic voltammetry and compares the results with those obtained from conventional screening techniques. The utilization of anodic current as an alternative to IC50 for evaluating antioxidant potency showcases the innovative capabilities of cyclic voltammetry in this context. Furthermore, the study employs column chromatography14 to fractionate compounds from extracts based on their polarity, followed by another cyclic voltammetric screening approach to pinpoint and isolate the specific compound responsible for antioxidant activity within different extract fractions. This research offers a multifaceted approach to investigating antioxidants, promising valuable insights for both analytical methods and compound isolation techniques.

Materials and methods

Chemicals and reagents

Ethanol (96%, Korea), methanol (analytical grade, Mark Life Sciences Private Limited, India), ethyl acetate (Mark Life Sciences Private Limited, India), n-Hexane (Daejung Chemicals & Metals Co. Ltd., South Korea), acetonitrile (CH3CN), chloroform (Duksan Pure Chemicals, Korea), acetone (Pallav Chemicals & Solvents Pvt. Ltd., India), ascorbic acid, 2,2 diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH, Sigma-Aldrich), Ferrocene (Fc, 98%, Sigma-Aldrich) were utilized as procured from the manufacturer. Tetrabutylammonium hexafluorophosphate ([n-Bu4N][PF6], Sigma-Aldrich) was procured from Sigma-Aldrich and subjected to recrystallization using hot ethanol15. Acetonitrile was selected as the solvent for cyclic voltammetry due to its wide electrochemical stability window, low viscosity, and excellent ability to dissolve both analytes and supporting electrolytes, ensuring reliable ion transport and minimal background interference.

Preparation of crude extract

The leafy vegetables Ipomoea aquatica and Colocasia esculenta were obtained from a vegetable market in Khulna, Bangladesh. These plant specimens underwent meticulous scrutiny and validation through the Plant Specimen Database Program and Publication at the Bangladesh National Herbarium, resulting in their authentication with specific accession numbers: 87,328 for I. aquatica (authenticated on 10 November 2022)16 and 60,834 for C. esculenta (authenticated on 12 October 2016)17. To obtain extracts, cold maceration method was utilized which are reported in various studies18,19,20,21,22we employed 300 g of powdered plant materials in 1000 mL of ethanol over a 10-day period, with periodic shaking. This was followed by filtration through cloth and filter paper, and the resulting solution was evaporated to achieve dryness.

Fractionation by column chromatography

In the context of our research, crude extracts derived from I. aquatica and C. esculenta underwent column chromatography14 for the purpose of fractionation. Separately, 1 gram of I. aquatica crude extract and 2 g of C. esculenta crude extract were employed. Apply the concentrated sample solution, prepared by dissolving it in chloroform (CHCl3), onto the top of the silica gel column. The initial phase of column chromatography utilized a nonpolar solvent system of n-hexane and ethyl acetate in a 90:10 ratio to elute the initial fractions. To progressively increase the polarity and achieve better separation of compounds, a gradient elution was subsequently applied using n-hexane: ethyl acetate mixtures in ratios of 85:15, 80:20, 75:25, 70:30, and 65:35. This systematic adjustment of solvent polarity facilitated effective fractionation of the crude extract. The yields of the resulting fractions varied, ranging from 40 to 70 mg, depending on the specific fraction collected. Notably, the chemical constituents found within the ethanolic extracts of both I. aquatica and C. esculenta were predominantly nonpolar in nature. The fractions were collected, designating the first fraction as “Fraction 1” and sequentially numbering the subsequent fractions. The crude extracts and their corresponding fractions were placed in airtight glass vials, covered with aluminum foil to minimize light exposure, and subsequently stored at 4 °C in a refrigerator until further analysis.

Phytochemical screening

The obtained crude extracts underwent qualitative phytochemical tests to identify the presence of primary phytochemical classes. The screening procedure adhered to established methodologies as described in relevant research literature23,24,25,26,27.

In-vitro antioxidant activity by DPPH free radical scavenging

Qualitative assay

The solutions of both the crude extracts and their respective fractions underwent qualitative TLC plate testing. In this procedure, ethanolic solutions of the samples, in addition to a standard ascorbic acid solution, were applied as spots on pre-coated silica gel TLC plates. These plates were subsequently developed in solvent systems with varying polarities, specifically: a polar system (n-hexane: Ethyl acetate, 3:1), a medium polar system (CHCl3: CH3OH, 5:1), and a non-polar system (CHCl3: CH3OH: H2O, 40:10:1). This allowed for the separation of polar and non-polar components within the extracts. The plates were air-dried at room temperature and then sprayed with a 0.02% solution of 1,1-diphenyl-2-picryl hydrazyl (DPPH) in ethanol. Over the course of 10 min, any bleaching of the DPPH may be observed as bands. Notably, a change in color from yellow against a purple background to deep pink indicated the presence of antioxidants in the chromatogram28.

Quantitative assay

The evaluation of the antioxidant capacity of the samples was based on their ability to scavenge the stable 2,2-diphenyl-1-picryl hydrazyl (DPPH) free radical by donating electrons. In this process, the samples undergo oxidation, while the DPPH radical is reduced.

Initially, 16 Eppendorf tubes were used to prepare aliquots at eight different concentrations (16, 32, 64, 128, 256, 512, 1024, and 2048 µg/mL) for both plant extracts. Additionally, another set of 10 Eppendorf tubes was employed to create aliquots with 10 different concentrations (1, 2, 4, 8, 16, 32, 64, 128, 256, and 512 µg/mL) for ascorbic acid, the standard. In both cases, methanol was used as the solvent. DPPH was accurately weighed and then dissolved in methanol to achieve a solution with a concentration of 0.007886% (w/v), ensuring complete dissolution using a sonicator.

In each well of the microplate, 100µL of various concentrations of plant extracts and ascorbic acid were dispensed, followed by the addition of 100µL of DPPH in methanol to each well, resulting in a total volume of 200µL. A blank solution was prepared by mixing 100µL of methanol with 100µL of DPPH. After thorough mixing, the microplate was left at room temperature for 30 min, and the absorbance was measured at 517 nm using a UV spectrometer. This entire procedure was repeated three times, and the average absorbance for each concentration was calculated. Similarly, selective fractions obtained through column chromatography, based on qualitative results, were subjected to UV absorbance measurements at various concentrations, mirroring the process for the crude extracts. % scavenged or % radical scavenging activity (% RSA)29 were calculated as-.

% scavenging or %RSA \(\:=\left(\frac{{\text{A}\text{b}\text{s}}_{\text{c}\text{o}\text{n}\text{t}\text{r}\text{o}\text{l}}-{\text{A}\text{b}\text{s}}_{\text{s}\text{a}\text{m}\text{p}\text{l}\text{e}}}{{\text{A}\text{b}\text{s}}_{\text{c}\text{o}\text{n}\text{t}\text{o}\text{r}\text{l}}}\right)\times\:100\)

IC50 was determined from % inhibition versus log concentration graph. The IC50 value represents the sample concentration needed to neutralize 50% of the DPPH free radicals30. % RSA value represents at certain sample concentration29.

Determination of antioxidant activity by cyclic voltammetry

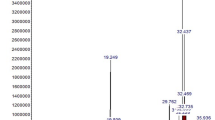

Electrochemical measurements were conducted using a Metrohm potentiostat. Cyclic voltammetric measurements were performed within a single-compartment cell utilizing a conventional three-electrode system. This three-electrode system comprised either a glassy carbon (GC) or gold (Au) working electrode, a pseudo-reference electrode made of silver (Ag) wire, and an auxiliary electrode composed of platinum wire. Prior to each measurement, the working electrode underwent a process of polishing using an aqueous Al2O3 slurry, followed by sequential rinses with water and acetone. The potential of the silver quasi-reference electrode was calibrated using the ferrocene oxidation (Fc0/+) process recommended by IUPAC31. The reversible formal potential (\(\:{E}^{0}\)) of ferrocene (Fc0/+) is theoretically expected to be 0 V, but it appears at 0.585 V (see Fig. 1) due to limitations in the experimental setup and possible manual errors. As with the adjustment made for ferrocene (Fc0/+), all cyclic voltammograms obtained from crude extracts and their fractions will be corrected by subtracting 0.585 V.

The plant extract and fraction solutions were prepared by dissolving them in acetonitrile (CH3CN), with ascorbic acid serving as the standard. A 0.10 M solution of [n-Bu4N][PF6] was employed as the supporting electrolyte. Cyclic voltammograms were registered at room temperature with a scan rate of 0.050 Vs-1. This traditional method of conducting cyclic voltammetry has been employed and documented in numerous prior research articles32,33,34,35,36,37.

Results

Phytochemical screening

In this study, an extensive examination of the phytochemical composition within the ethanol extracts of I. aquatica and C. esculenta was conducted with the objective of detecting and characterizing the presence of bioactive substances. The phytochemical analysis of the crude extracts unveiled a range of compounds. Specifically, I. aquatica was found to contain reducing sugars, glycosides, phenols, tannins, and flavonoids, while C. esculenta exhibited a more diverse profile encompassing reducing sugars, glycosides, phenols, tannins, flavonoids, terpenoids, alkaloids, and xanthoproteins.

In-vitro antioxidant activity by DPPH free radical scavenging

Figure 2 presented the thin-layer chromatograms for the crude extracts of I. aquatica, C. esculenta, and the standard ascorbic acid in three distinct solvent systems: non-polar, medium polar, and polar. In this assessment, a pale-yellow color against a purple background was observed, with ascorbic acid exhibiting significant antioxidant activity across all solvent systems, with a more pronounced effect in non-polar and medium-polar environments. Similarly, the free-radical scavenging capability of the crude extracts was notably enhanced in non-polar and medium-polar environments. This qualitative analysis was also employed for the fractions obtained from two crude extracts of I. aquatica and C. esculenta.

Further quantitative assessment of antioxidant activity through DPPH free radical scavenging was conducted on crude extracts and specific fractions, including fraction 1 (n-hexane: Ethyl acetate, 90:10), fraction 2 (n-hexane: Ethyl acetate, 85:15), fraction 3 (n-hexane: Ethyl acetate, 85:15), and fraction 8 (n-hexane: Ethyl acetate, 65:35) of I. aquatica, as well as fraction 1 (n-hexane: Ethyl acetate, 90:10), fraction 2 (n-hexane: Ethyl acetate, 85:15), and fraction 3 (n-hexane: Ethyl acetate, 80:20) of C. esculenta. These specific fractions were selected based on their promising results in the qualitative antioxidant assay.

In the quantitative evaluation (see Table 1) of in-vitro antioxidant potential through DPPH free-radical scavenging, it was observed that fraction 2 of the I. aquatica extract exhibited significant antioxidant capability, with an IC50 value of 41.80 µg/mL, though slightly less potent than the standard ascorbic acid with an IC50 value of 14.79 µg/mL. On the other hand, fraction 1 and fraction 3 of the I. aquatica extract demonstrated moderate antioxidant potential, having IC50 values of 80.29 and 86.19 µg/mL, respectively. Fraction 8, however, showed relatively insignificant antioxidant capacity, with an IC50 value of 153.41 µg/mL while, the crude extract itself displayed the lowest IC50 value of 188.15 µg/mL within the I. aquatica extract and its fractions.

Conversely, generally more robust results were observed for extracts of C. esculenta and its respective fractions (1, 2, and 3), exhibiting IC50 values of 170.84, 35.55, 45.81, and 92.32 µg/mL, respectively.

The percent radical scavenging activity (%RSA) at 512 µg/mL is also presented in (Table 1). The highest %RSA was observed for the standard ascorbic acid (93.92%), which corresponds to the lowest IC50 value (14.79 µg/mL), while the lowest %RSA was recorded for the crude extract of I. aquatica (64.49%), which had the highest IC50 (188.15 µg/mL). All other samples followed this inverse relationship trend between %RSA and IC50 values.

Antioxidant activity by cyclic voltammetry

Like the quantitative antioxidant assay employing free-radical scavenging, the same extracts and their fractions underwent cyclic voltammetric analysis to investigate potential electron transfer events.

Figure 3 displays cyclic voltammograms obtained at a GC electrode, depicting the oxidation of ascorbic acid in CH3CN (0.10 M [n-Bu4N][PF6]) at a scan rate of 0.050 Vs− 1. This voltammogram reveals an irreversible oxidation process, occurring at approximately + 0.545 V vs. Fc0/+, with no concurrent reduction process upon reversing the potential direction.

In the electrochemical system, when electrochemically reactive species within the reaction medium donate electrons (or electron), they become oxidized, and the working electrode consumes the available free electron(s). In contrast, during the electrochemical reduction process, the electrode supplies the necessary electrons. For instance, in the case of ascorbic acid, it donates two electrons, undergoes oxidation, and the released electrons are taken up by the glassy carbon (GC) working electrode (see Fig. 4).

Henceforth, in the discussion of results, the forward potential scan will be specifically emphasized for the representation of the oxidation peak if there is any electron transfer taking place during the experiment for the crude extracts and their fractions obtained through column chromatography.

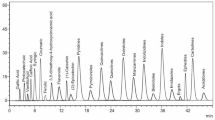

Figure 5 illustrates forward scan voltammograms using both glassy carbon (GC) and gold (Au) electrodes for the crude extract of I. aquatica. The crude extract displayed electron transfer events at approximately + 0.215 V vs. Fc0/+ and + 0.490 V vs. Fc0/+ with both GC and Au electrodes, with a more pronounced effect observed with the Au electrode.

Figure 6a demonstrates that fraction 1, obtained from the crude extract of I. aquatica, exhibited electron transfer related to oxidation within a potential range of + 0.350 to + 0.450 V vs. Fc0/+ for both electrodes, which falls between the two electron transfer events observed in the crude extract (Fig. 5).

Fraction 2, derived from the crude extract of I. aquatica, as depicted in Fig. 6b, showed a single oxidation process at the same potential region as fraction 1 for both working electrodes. Notably, the GC electrode had a more pronounced effect in this process, which displayed well-defined electron transfer characteristics.

However, fraction 3 and 8 (as seen in Fig. 6c and d) did not exhibit any electron transfer events within the experimental potential range.

Both the crude extract of C. esculenta and its fractions underwent identical electrochemical experiments, using the same working electrodes and potential range as previously described. In the case of the crude extract, a single oxidation process was observed, as shown in Fig. 7a, occurring at approximately + 0.490 V vs. Fc0/+ when the Au electrode was used among the working electrodes.

However, fraction 1, as seen in Fig. 7b, no electrochemical response was detected with either electrode, while fraction 2 (as shown in Fig. 7c) exhibited insignificant electron transfer events with both electrodes, occurring at a lower potential than the electron transfer event of the crude extract. In contrast, with both electrodes, fraction 3 displayed a distinct oxidation process (depicted in Fig. 7d) at around + 0.365 V vs. Fc0/+.

Discussion

Phytochemical analysis plays a crucial role in plant-focused research by facilitating the identification and investigation of bioactive components present in plant extracts. Nature offers a diverse array of secondary metabolites that are recognized for their pharmacological activities, contributing to a broad spectrum of biological effects like antioxidant activity. This makes these plants valuable in the realms of traditional medicine, phytotherapy, and aromatherapy. This assessment process provides valuable insights into the chemical constituents found within extracts of I. aquatica and C. esculenta, encompassing glycosides, reducing sugars, tannins, flavonoids, steroids, and more.

In our qualitative Thin-Layer Chromatography (TLC) analysis, we utilized a straightforward approach to evaluate the antioxidant potential of different plant extracts and their fractions obtained through column chromatography. The process involved applying the plant extracts and a standard ascorbic acid solution to separate TLC plates, which were then subjected to TLC separation. After developing and drying the TLC plates, we assessed the antioxidant activity by spraying a DPPH solution over the spots corresponding to the plant extracts, their fractions, and ascorbic acid on the plates. DPPH changes color from purple to pale yellow or colorless when it encounters an antioxidant, indicating its ability to neutralize free radicals. The extent of this color change on the TLC plates provided a qualitative measure of the antioxidant activity, with a more pronounced shift indicating stronger antioxidant effects.

Extracts of both I. aquatica and C. esculenta, along with selected fractions obtained from these extracts, exhibited free radical scavenging properties, evident as the appearance of yellow spots against a purple TLC plate background. This observation prompted us to proceed with a quantitative evaluation of their antioxidant activity. Now, as we transition to the quantitative antioxidant activity test, these yellow spots provide the basis for further investigation, allowing us to determine and compare the extent of the antioxidant effects among different plant extracts and their respective fractions.

The DPPH free radical scavenging test38 plays a crucial role in investigating the antioxidant potential of the examined extracts and their selected fractions, shedding light on their capacity to counteract harmful radicals and contribute to managing oxidative stress.

During this evaluation, an unpaired electron present in the antioxidants interacts with a radical scavenger, such as DPPH, leading to the oxidation of the former and the simultaneous reduction of the free radical. As a result, the DPPH solution undergoes a decolorization process, the extent of which is reliant on the antioxidative strength of the extracts. This decolorization becomes more pronounced with sample concentrations and varying sample types. The visual manifestation of this process is a transition from a deep violet color to a pale-yellow shade.

Furthermore, the degree of reduction in absorbance measurement serves as an indicator of the extracts’ scavenging activity against free radicals39. It is important to note that this method not only helps in gauging antioxidant capacity but also provides an empirical basis for assessing and comparing the antioxidant potential among different extracts and their concentrations.

Among the various samples, including the crude extract and fractions of I. aquatica, it was evident that fraction 2 exhibited the highest level of free radical scavenging activity, with an IC50 of 41.80 µg/mL. In contrast, the crude extract displayed the lowest scavenging activity, with an IC50 of 188.15 µg/mL. On the other hand, when considering the crude extract and fractions of C. esculenta, it was fractions 1 and 2 that demonstrated promising antioxidant activity, with IC50 values ranging from approximately 35 to 46 µg/mL. For reference, the standard ascorbic acid showed an IC50 value of 14.79 µg/mL. Previous studies on other species within the Ipomoea genus (e.g., Ipomoea carnea, Ipomoea batatas) and the Colocasia genus (e.g., Colocasia fallax, Colocasia affinis) have also reported varying degrees of antioxidant activity40,41,42,43. These findings suggest that antioxidant potential may vary significantly not only between genera but also among different species and solvent fractions within the same plant.

The variance in scavenging potential among these different extracts and fractions can be attributed to the varying quantities of antioxidative compounds, such as flavonoids, tannins and phenolic compounds present within these extracts. Phenolic compounds are recognized for their remarkable antioxidant properties attributed to their distinctive redox characteristics. These compounds can act as reducing agents, hydrogen donors, and quenchers of singlet oxygen, and they can even chelate metallic ions. Studies by Kim and Lim44 (2016) emphasize the correlation between the overall antioxidant capacity of a sample and the total phenolic content in its extracts. Additionally, research by Yi-Zhong Cai et al.45. (2006) has shed light on the relationship between the scavenging efficiency of phenolic compounds against DPPH radicals and their specific chemical structures.

Flavonoids possess the ability to counteract superoxide, hydroxyl, and peroxyl radicals, thus influencing various stages in processes like the arachidonate cascade involving lipoxygenase and cyclooxygenase-246. Tannins, on the other hand, are recognized as aqueous polyphenols with a notable capacity to scavenge free radicals47. This diversity in antioxidative compounds contributes to the variations in the observed free radical scavenging activities among the tested extracts.

In the cyclic voltammetric assay, the standard ascorbic acid displayed a well-defined and irreversible two-electron transfer process associated with oxidation, allowing these electrons to scavenge and reduce free radicals such as DPPH. Similarly, for extracts and fractions displaying antioxidant potential, it’s anticipated that they involve electron transfer events linked to oxidation, with some presenting well-defined processes indicating strong antioxidant potential.

Crude extracts of I. aquatica and C. esculenta showed a single electron transfer event related to oxidation. These electron transfer capabilities suggest that specific fractions of these extracts can contribute electrons for the scavenging of free radicals.

In the case of I. aquatica, fraction 1 and fraction 2 displayed a single electron transfer event, with fraction 2 exhibiting a well-defined process. This observation aligns with the lower IC50 value in the DPPH free radical scavenging assay for fraction 2. Similarly, the lower IC50 value of 153.41 for fraction 8 can be attributed to its lack of an electrochemical response. In C. esculenta, fractions 2 and 3 showed clear electron transfer signals in cyclic voltammetry, with fraction 2 exhibiting a well-defined redox process. In contrast, fraction 1 displayed strong DPPH free radical scavenging activity (IC50 = 35.55 µg/mL) but no electrochemical response. This discrepancy likely arises because some antioxidants act through mechanisms such as hydrogen atom transfer or metal ion chelation, which do not produce redox peaks at the electrode surface. While DPPH assays detect antioxidant activity via multiple pathways, cyclic voltammetry specifically reflects compounds capable of direct electron transfer, explaining the absence of voltammetric signals in certain active fractions.

However, some variation was observed in the voltammograms with the Au electrode. For instance, the crude extract of C. esculenta demonstrated a single electron transfer event with the Au electrode, whereas no response was seen with the GC electrode. The distinct voltammetric responses observed on Au and GC electrodes likely arise from differences in their surface chemistry and how analytes interact with them. GC, with its mix of sp2 and sp3 hybridized carbon, tends to support planar π–π interactions, favoring adsorption of aromatic compounds. In contrast, Au surface can promote adsorption through aromatic or thiol interactions. These variations in molecular orientation and binding at the electrode interface influence electron transfer efficiency and signal intensity, providing a reasonable explanation for the distinct electrochemical profiles recorded on Au versus GC48.

The electrochemical analysis of various extracts and their fractions revealed the occurrence of electron transfer processes in some fractions of both extracts, as well as in the crude extracts. It was expected that samples with strong scavenging capabilities would exhibit efficient electron transfer processes characterized by higher anodic current32. This would enable a correlation between the electrochemical findings and the results obtained from the DPPH scavenging assay, a common method for assessing antioxidant activity.

However, it’s essential to note that the cyclic voltammetric test, despite providing valuable insights, is inherently qualitative. Therefore, a direct quantitative correlation with the DPPH assay results was not feasible. Nevertheless, the cyclic voltammetric sensing results support the notion that electron transfer processes, specifically oxidation, occur in various fractions as well as in the crude extracts. This electron transfer is a vital mechanism by which these samples can effectively scavenge free radicals.

Conclusion

In conclusion, our research focused on phytochemical analysis to identify chemical components associated with free radical scavenging. We employed qualitative Thin-Layer Chromatography (TLC) to assess antioxidant potential, observing color shifts confirming free radical neutralization. Quantitative evaluation revealed varying scavenging properties among plant extracts and fractions, with certain extracts demonstrating strong antioxidant activity. Cyclic voltammetric assay supported these findings, highlighting electron transfer mechanisms related to oxidation. While direct quantitative correlations were limited, our results collectively emphasize the diverse antioxidant potential of plant extracts, contributing to a comprehensive understanding of their antioxidative properties and their potential applications in addressing oxidative stress and related health issues.

Data availability

Data is provided in the supplementary information files.

References

Phaniendra, A., Jestadi, D. B. & Periyasamy, L. Free radicals properties, sources, targets, and their implication in various diseases. Indian J. Clin. Biochem. 30 11–26 https://doi.org/10.1007/s12291-014-0446-0 (2015).

Di Meo, S. & Venditti, P. Evolution of the knowledge of free radicals and other oxidants. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 1–32 (2020).

Kehrer, J. P. & Klotz, L. O. Free radicals and related reactive species as mediators of tissue injury and disease: implications for health. Crit. Rev. Toxicol. 45, 765–798 (2015).

Mousa, Z. et al. in (Tat, S. S. eds) vol. 10 11–22 (IntechOpen, 2019).

Willcox, J. K., Ash, S. L. & Catignani, G. L. Antioxidants and prevention of chronic disease. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 44, 275–295 (2004).

Lobo, V., Patil, A., Phatak, A. & Chandra, N. Free radicals, antioxidants and functional foods: impact on human health. Pharmacogn Rev. 4, 118 (2010).

Santos-Sanchez, N. F., Salas-Coronado, R., Villanueva-Canongo, C. & Hernandez-Carlos, B. Antioxidant compounds and their antioxidant mechanism. in Antioxidants (ed Shalaby, E.) vol 5 1–29 (IntechOpen, London, UK, (2019).

Sharifi-Rad, M. et al. Lifestyle, oxidative stress, and antioxidants: back and forth in the pathophysiology of chronic diseases. Front. Physiol. 11, (2020).

Pandey, K. B. & Rizvi, S. I. Plant polyphenols as dietary antioxidants in human health and disease. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2, 270–278 (2009).

Munteanu, I. G. & Apetrei, C. Analytical methods used in determining antioxidant activity: A review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22, 3380 (2021).

Ziyatdinova, G. & Kalmykova, A. Electrochemical characterization of the antioxidant properties of medicinal plants and products: A review. Molecules 28, 2308 (2023).

Chevion, S., Roberts, M. A. & Chevion, M. The use of Cyclic voltammetry for the evaluation of antioxidant capacity. Free Radic Biol. Med. 28, 860–870 (2000).

Hernanz-Vila, D., jara-Pelacios, M. J., Escudero-Gilete, M. L. & Heredia, F. J. Applications of voltammetric analysis to wine products. in Applications of the Voltammetry (eds Stoytcheva, M. & Zlatev, R.) 109 (IntechOpen, London, UK, (2017).

Coskun, O. Separation tecniques: CHROMATOGRAPHY. North. Clin. Istanb. https://doi.org/10.14744/nci.2016.32757 (2016).

Sawyer, D. T., Sobkowiak, A. & Robert, J. Jr. Electrochemistry for Chemists (John Wiley & Sons, 1995).

Ipomoea aquatica Forssk | Plant Specimen Database Program & Publication. https://plantsp-eflora.bnh.gov.bd/specimen/details?id=13770&name=Ipomoea%20aquatica%20Forssk

Colocasia esculenta (L. ) Schott | Plant Specimen Database Program & Publication. https://plantsp-eflora.bnh.gov.bd/specimen/details?id=6046&name=Colocasia%20esculenta%20%20(L.)%20Schott.

Hossain, M. L., Monjur-Al-Hossain, A. S. M., Sarkar, K. K., Hossin, A. & Rahman Md. A. Phytochemical screening and the evaluation of the antioxidant, total phenolic content and analgesic properties of the plant Pandanus foetidus (Family: Pandanaceae). Int. Res. J. Pharm. 4, 170–172 (2013).

Khushi, S. et al. Phytochemical and Pharmacological screening of Enhydra fluctuans Lour. Khulna Univ. Stud. 19–26 https://doi.org/10.53808/KUS.2016.13.1.1501-L (2022).

Ullah Mishuk, A. et al. Assessment of phytochemical and Pharmacological activities of the ethanol extracts of Xanthium indicum. IJPSR 3, 4811–4817 (2012).

Bachhar, V. et al. In-Vitro Antimicrobial, Antidiabetic and Anticancer Activities of Calyptocarpus Vialis Extract and its Integration with Computational Studies. ChemistrySelect 9, (2024).

Joshi, V. et al. Rheological and anticorrosion study of Piper Chaba extract and coating for mild steel in 2 M H2SO4. Colloids Surf. Physicochem Eng. Asp. 708, 135989 (2025).

Harborne, J. Phytochemical methods: a guide to modern techniques of plant analysis. in Methods of Plant Analysis 1–36 (Dordrecht: Springer, Netherlands, (1984).

Parekh, P. & Chanda, S. Phytochemicals screening of some plants from Western region of India. Plant. Arch. 8, 557–562 (2008).

Shah, V. K. & Rahman, M. A. Antioxidative and animal model-based Pharmacological properties evaluation of leaves of Trema cannabina Lour. Bioscience Bioeng. Commun. 4, 152–161 (2022).

Sofowora, A. Medicinal Plants and Traditional Medicine in Africa (Spectrum Books, 1993).

Trease, G. E. & Evans, W. C. Pharmacognosy (Baillière Tindall, 1989).

Gu, H. F. et al. Structural features and antioxidant activity of tannin from persimmon pulp. Food Res. Int. 41, 208–217 (2008).

Amarowicz, R., Pegg, R. B., Rahimi-Moghaddam, P., Barl, B. & Weil, J. A. Free-radical scavenging capacity and antioxidant activity of selected plant species from the Canadian prairies. Food Chem. 84, 551–562 (2004).

Jain, V., Verma, S. K., Katewa, S. S., Anandjiwala, S. & Sing, B. Free radical scavenging property of Bombax ceiba linn. Root. Res. J. Med. Plant. 5, 462–470 (2011).

Gritzner, G. & Kuta, J. Recommendations on reporting electrode potentials in nonaqueous solvents (Recommendations 1983). Pure Appl. Chem. 56, 461–466 (1984).

Amidi, S., Mojab, F., Bayandori Moghaddam, A., Tabib, K. & Kobarfard, F. A simple electrochemical method for the rapid Estimation of antioxidant potentials of some selected medicinal plants. Iran. J. Pharm. Res. 11, 117–121 (2012).

Hilgemann, M. & Costa Bassetto, V. Tatsuo kubota, L. Electrochemical approaches employed for sensing the antioxidant capacity exhibited by vegetal extracts: A review. Comb. Chem. High. Throughput Screen. 16, 98–108 (2013).

Li, J. et al. Impact of Sp 2 carbon edge effects on the Electron-Transfer kinetics of the ferrocene/ferricenium process at a Boron-Doped diamond electrode in an ionic liquid. J. Phys. Chem. C. 123, 17397–17406 (2019).

Rahman, M. A., Gundry, L., Ueda, T., Bond, A. M. & Zhang, J. Electrode material dependence, ion pairing, and progressive increase in complexity of the α-[S 2 W 18 O 62 ] 4–/5–/6–/7–/8–/9–/10– reduction processes in acetonitrile containing [ n -Bu 4 N][PF 6 ] as the supporting electrolyte. J. Phys. Chem. C. 124, 16032–16047 (2020).

Rahman, M. A. et al. Electrode kinetics, and mechanistic nuances associated with the voltammetric reduction of dissolved [ n-Bu4N]4[PW11O39{Sn(C6H4)CC(C6H4)(N3C4H10)}] and a Surface-Confined diazonium derivative. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 3, 3991–4006 (2020). Thermodynamics.

Rahman, M. A. et al. Modelling limitations encountered in the thermodynamic and electrode kinetic parameterization of the α-[S2W18O62]4–/5–/6 – processes at glassy carbon and metal electrodes. J. Electroanal. Chem. 872, 113786 (2020).

Kedare, S. B. & Singh, R. P. Genesis and development of DPPH method of antioxidant assay. J. Food Sci. Technol. 48, 412–422 (2011).

Ayoola, G. et al. Phytochemical screening and antioxidant activities of some selected medicinal plants used for malaria therapy in Southwestern Nigeria. Tropical J. Pharm. Res. 7, (2008).

Ali Ghasemzadeh. Polyphenolic content and their antioxidant activity in leaf extract of sweet potato (Ipomoea batatas). J. Med. Plants Res. 6, (2012).

Somasundaram, A., Ambiga, S. & Jeyaraj, M. Evaluation of in Vitro Antioxidant Activity of Ipomoea Carnea Jacq. Int. J. Curr. Microbiol. App. Sci. vol. 4 http://www.ijcmas.com (2015).

Mondal, M. et al. Phytochemical screening and evaluation of Pharmacological activity of leaf methanolic extract of Colocasia affinis Schott. Clin. Phytoscience. 5, 8 (2019).

Zilani, M. N. H. et al. Analgesic and antioxidant activities of Colocasia fallax. Orient. Pharm. Exp. Med. 16, 131–137 (2016).

Kim, S. M. & Lim, S. T. Enhanced antioxidant activity of rice Bran extract by carbohydrase treatment. J. Cereal Sci. 68, 116–121 (2016).

Cai, Y. Z., Sun, M., Xing, J., Luo, Q. & Corke, H. Structure–radical scavenging activity relationships of phenolic compounds from traditional Chinese medicinal plants. Life Sci. 78, 2872–2888 (2006).

Alanko, J. et al. Modulation of arachidonic acid metabolism by phenols: relation to their structure and antioxidant/prooxidant properties. Free Radic Biol. Med. 26, 193–201 (1999).

Koleckar, V. et al. Condensed and hydrolysable tannins as antioxidants influencing the health. Mini-Reviews Med. Chem. 8, 436–447 (2008).

Shayani-jam, H. Electrochemical study of adsorption and electrooxidation of 4,4′-biphenol on the glassy carbon electrode: determination of the orientation of adsorbed molecules. Monatsh Chem. 150, 183–192 (2019).

Acknowledgements

The authors express their gratitude to Sumon Chakrabarty, Associate Professor of Chemistry, Khulna University, for providing access to the Chemistry lab for conducting electrochemical experiments. The authors also thank the RIC at Khulna University for their logistical support. The assistance of Md. Abdullah Al Shafi, one of the master’s students, is also gratefully acknowledged.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Omeo Sultana Anu developed the experimental design, conducted the experiments, and drafted the main manuscript. Sabbir Ahmed provided laboratory assistance during the experiments. Md. Tariqul Islam and Vikash Kumar Shah contributed to the preparation and refinement of the manuscript. Md. Iqbal Ahmed assisted in interpreting the results and further supported manuscript preparation. The corresponding author, Md. Anisur Rahman conceptualized the research, supervised the master’s student Omeo Sultana Anu, analyzed and interpreted the results, prepared the figures, and finalized the manuscript for submission.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Anu, O.S., Ahmed, S., Islam, M.T. et al. Comparative investigation of free radical scavenging and cyclic voltammetric analyses to evaluate the antioxidant potential of selective green vegetables extracts. Sci Rep 15, 31919 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-12731-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-12731-y

) and Au (

) and Au ( ) electrodes.

) electrodes.

) and Au (

) and Au ( ) electrodes.

) electrodes.

) and Au (

) and Au ( ) electrodes.

) electrodes.