Abstract

A study was carried out to evaluate the impact of different land use types on particular soil physical and chemical parameters in the Liban Jawi district, West Shewa Zone, Oromia, Ethiopia. Land use changes significantly influence soil quality by altering its physical and chemical properties, and understanding these impacts is essential for sustainable land management; however, in areas like Liban Jawi District, West Shewa Zone, Ethiopia, limited information exists on how different land use types affect soil characteristics. The three land use types: Forest lands (FL), Grazing lands (GL), and Cultivated lands (CL) were represented in the 9 soil samples collected using an auger and bulk density (BD) by core sampler for the analysis of soil properties at a depth of 0–30 cm with three replications. The analysis of soil samples was carried out in the Ambo University Chemistry laboratory. The result of the research showed that the textural classes of GL and CL were loamy sand, whereas, sandy loam in the FL. The BD recorded in the three land use types was statistically insignificant. The highest organic carbon (OC) 7.06%, Available phosphorus (Av.p) 70.7 mg/kg, Total nitrogen (TN) 0.82%, cation exchange capacity (CEC) 49.86 cmol/kg, electrical conductivity (EC) 0.08 ds/m, Calcium (Ca) 13.17 cmol/kg, Magnesium (Mg) 8.47 cmol/kg, and Potassium (K) 2.56 cmol/kg were recorded in FL, followed by GL. The study revealed a significant (P < 0.01) variation among the land use types for pH, OC, TN, Ca2+ and Na. However, land use types did not significantly affect Av. P, CEC, Mg2+, K, and EC. It is possible to conclude that soil physicochemical properties differed by land use due to the exhaustive exploitation of land resources and improper soil management systems in the area, highlighting the need for better soil management in cultivated and grassland areas. Therefore, there is a need to develop integrated soil management practices that could sustain agricultural productivity and production.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Throughout centuries, land has been intricately linked with economic growth, serving as the backbone of agricultural and industrial development1. The utilization of land reflects a complex interplay between a society’s cultural values, governance structures, and material needs on the one hand, and the inherent natural potential of the land on the other2. However, unsustainable land use has resulted in severe environmental degradation, including soil erosion, deforestation, loss of biodiversity, and reduced agricultural productivity3,4. These consequences have far-reaching impacts, threatening food security, water availability, and the livelihoods of millions who depend on natural resources5. Unsustainable practices such as overgrazing, intensive cultivation without adequate soil conservation measures, and unplanned urban expansion exacerbate ecosystem vulnerability6. Additionally, the long-term effects of these practices contribute to climate change, as deforestation and land degradation release significant amounts of greenhouse gases into the atmosphere4. Addressing these challenges requires adopting sustainable land management practices supported by effective policies, community engagement, and technological innovation3.

Globally, unsustainable land use is a critical factor contributing to soil degradation, which causes substantial changes in soil quality parameters7,8. These changes lead to a decline in soil quality and nutrient content, adversely affecting agricultural production, food security, and the livelihoods of many communities9. Approximately 1 million square kilometers of land are degraded annually, presenting serious challenges to climate stability, biodiversity conservation, and sustainable food production10. Furthermore, the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) has emphasized that the widespread degradation of land and water resources jeopardizes global food production systems. The11, report highlighted that while agricultural advancements have increased food production, they have also contributed to unsustainable land management practices, further exacerbating resource degradation.

Land use practices play a pivotal role in shaping the physicochemical characteristics of soil, with different land use types leading to notable variations12,13, resulting in significant alterations in soil properties, directly affecting soil fertility and agricultural productivity. Land use variation (forest, farming, and grazing) results in significant variations in the physicochemical properties of the soil. Land use and soil management can have a discernible impact on the soil’s characteristics and associated ideas14.The type of land use is a critical determinant of soil value and physicochemical characteristics, as it influences key factors such as organic matter content, nutrient availability, and overall soil fertility.15, emphasized that land use significantly impacts soil properties, shaping its capacity to support vegetation and agricultural productivity.

Ethiopia is known as one of the emerging economies that has historically relied heavily on agriculture. In addition, agricultural activities have been the backbone and main source of sustainability of the Ethiopian economy, which is known for its very low growth rate. In Ethiopia, land degradation remains a significant challenge. The rapidly increasing population has led to a decreasing amount of land for cultivation purposes and a very high rate of soil erosion16.17, reported that the country loses approximately 30,000 hectares of agricultural land each year to water erosion, with over 2 million hectares experiencing severe degradation annually, resulting in a 20% loss of agricultural land productivity, posing challenges to food security and rural livelihoods. Recent studies have highlighted the significant impact of land degradation on agricultural productivity, which in turn poses challenges to food security and rural livelihoods. According to,18, found that large-scale agricultural investments in Ethiopia’s Gambella region have led to a decline in food availability and access among local communities, exacerbating food insecurity.

Ethiopia’s low soil fertility has been attributed to various factors, including crop harvesting, soil erosion, poor soil quality, and limited use of organic or inorganic fertilizers19,20. This challenge is particularly evident in regions with intensive farming practices, where the land has been overexploited without adequate soil restoration measures. Changes in land use and soil management significantly affect soil organic matter stock, as deforestation and the exploitation of virgin tropical soils often lead to nutrient loss, particularly nitrogen (N), phosphorus (P), and sulfur (S), which are integral components of complex organic polymers21. Chronic deforestation, the conversion of natural forests into agroecosystems, and unchecked overgrazing have emerged as the primary drivers of soil erosion and climate change in Ethiopia22,23,24.

In recent years, the global issue of environmental degradation driven by inappropriate land use has underscored the urgent need for sustainable agricultural production systems3,21. Understanding the relationship between land use practices and soil properties is critical for developing strategies that promote the sustainable use of soil resources while enhancing crop productivity25. Specifically, detailed knowledge about the impact of different land use types on soil physicochemical properties is essential to inform evidence-based recommendations for soil management19,22. Land use changes significantly influence soil quality by altering its physical and chemical properties, and understanding these impacts is essential for sustainable land management; however, in areas like Liban Jawi District, West Shewa Zone, Ethiopia, limited information exists on how different land use types affect soil characteristics.

Despite the importance of this issue, limited studies have been conducted to evaluate the influence of land use on soil’s physicochemical properties in the study area. To address this gap, this study was undertaken to assess the effects of land use changes on selected soil physicochemical properties in the Liban Jawi district. The findings are expected to contribute to sustainable land management practices and agricultural productivity improvements in the region.

Materials and methods

Description of the study area

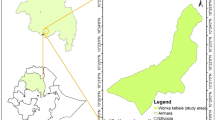

The study was conducted in Liben Jawi District, which is found in West Shewa Zone Oromia, Ethiopia (Fig. 1). It is one of the 22 Districts of West Shewa Zone. The land size of the District is 31,900 0.55 ha, and it is located 161 km from the capital city, Addis Ababa, toward the west of the country. The geographical location of the site is between latitudes 9° 2′0′′ and 9° 24′30′′ N and longitudes 37° 26′00′′ E and 37° 39′05′′ E26,27.

The districts of Liben Jawi have a bi-modal and irregular distribution, featuring a brief rainy season from February to April and a lengthy one from June to September. The average annual rainfall in these areas is between 900 and 1800 mm28. The district’s climate is classified as highland, mid-highland, and lowland, making up 6.6%, 73.3%, and 20% of the total area, respectively. Temperatures range from 16 to 28 °C at the highest and lowest points.

According to a report from the Liben Jawi District Agriculture and Rural Development Office (2014), clay minerals make up 36.25% of the district’s soil, red and black soil 34.37%, and mixed or brown soil 29.38%.

In the study area, the small size of farms and limited grazing land make fallow lands uncommon, according to26. This unavailability of fallow land has led to continuous cultivation, reducing soil fertility and increasing soil erosion. The predominant agricultural practice, along with cattle rearing, is rain-fed subsistence farming. The major rainy season is the time when the dominant crops- wheat, linseed, barley, and faba beans- are cultivated. Another crucial component of the farming system is livestock production. Most farm households raise small livestock, such as Goat, Poultry, Horses, and primarily oxen. Land use in the study area comprises cultivated land, grazing land, forest land, and other land types in varying percentages (Table 1).

The differences in climate, soil type, and human activities resulted in various vegetation types. The major types of soil in the district are loam soil (48%), clay soil (27%), and mixed soil type (25%). Many indigenous tree species are found in the area but with very limited abundance. They are found on some farmer’s farmlands, around churches, homesteads, and as community woodlots. Natural vegetation is very much degraded.

Cordia africana (Waddessa), Juniperus procera (Gaattiraa Oromo), Croton Microstachyus (Bakkaniisa), Prunus africana (Hoomii), Hagenia abyssinica (Heexoo), Accacia albida (Laaftoo), Acacia gumifera (Imalaa), Olea africana (Ejersa), and Podocarpus falcats (Birbisa) are some of the substantial indigenous tree species that have survived in the area. Furthermore, significant exotic trees, including Cupressus lusitania (Gatira faranji), Gravilia robusta (Muka baar), Eucalyptus camaldulesis (Baargamoo dima), and Eucalyptus globules (Baargamoo adi) are frequently seen in the region.

The 2011 National Population Census Report states that the total population of the district is 95,290, 48,750(51.16%) male and 46,540 (48. %) female28. Most of those who reside in the study area are Oromo ethnic, and they speak Afaan Oromo. A sizable portion of the community can also communicate in Amharic.

The method of farming and livelihood It is said that Liben Jawi District has a decent chance of producing agricultural goods. The timely commencement, volume, duration, and distribution of rainfall are crucial to agriculture. Every year, major crops such as cereals, pulses, and oil crops are grown in decreasing order of area coverage (WMO). The primary food sources and revenue for sustaining the study area are livestock-rearing land use systems and rain-fed agriculture mixed cropping.

No planting is done in February or April since crops are planted and harvested between September and January. Eragrositis tef (Tef), Triticum aestivum (Wheat), Sorghum bicolor (Sorghum), Hordeum vulgar (Barley), Vicia faba (Faba beans), and Zea mays L (Maize) are the main cereal crops that are grown.

Only the oxen plow and the conventional tillage method are used for farming. There aren’t many people working every day. During busy times like harvesting, weeding, and soil tilling, landless farmers might sell their labor. The Liben Jawi District relies heavily on agriculture, which is primarily rain-fed and has low yield.

The District Office of Livestock reports that there are 77,461 cattle; 48,652 goats and sheep; 13,428 mules, horses, and donkeys; and 54,133 hens in total. In addition to providing family income, cattle in the study region are utilized to make organic fertilizer from their manure. The main sources of income for the local inhabitants are agriculture and animal husbandry26.

The Liben Sukateli micro watershed study area is situated in the Liben Jawi district, in the Liben Gamo kebele, a tributary of the Gamoo River. It has a total area of hectares, of which 400 ha are used for agriculture, 108 ha for grazing, 66.6 ha for bushland and Rukruki forest, 180 ha for homesteading, and 32.4 ha for other uses. Clay, sand, and loam are the three main soil types found in the research region. The altitude has an average of 2000 m above sea level and varies from 1100 to 2900 m above sea level.

Methods

Soil sampling and sample size determination

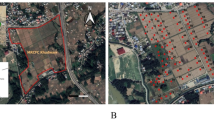

This study employed a randomized complete block design to collect soil samples from three representative land use types: Forest, Cultivated, and Grazing. From each land use category, 1 kg of soil was collected to analyze selected physical and chemical properties. The study area was divided into topographic classes: Upstream, Midstream, and Downstream. Soil samples were taken from each land use type at three different elevations, with three replications, resulting in twenty-seven samples.

Sampling points were chosen to ensure representativeness. Soil samples were collected using a Zigzag plot design, with a depth of 30 cm in a 20 m × 20 m area. Four 1 m × 1 m “X” samples were taken to a depth of 30 cm and then composited by mixing soils from the four corners and the center of each plot to create a representative sample for each plot (Fig. 2).

Using an auger and core sampler, soil samples were taken directly from the designated areas of three different land use types and placed in a sampling bag. Additionally, the altitude and latitude separation between the sampling locations are provided by the GPS receiver. The GPS reading’s x-ordinate point was X = 37489454 Y = 8957363. The region was divided according to the topographic class of the soil (from upstream, downstream, and the medium section of the land). Three land units for each land use (3LU * 3 replication* 1 depth and 3 replications) were chosen from the identified land use types.

Soil sample preparation

Soil sample preparation and analysis were done in the plant science laboratory and chemistry department of Ambo University. Each land use type’s representative site provided composite topsoil (0–30 cm) samples, which were then tagged, air-dried, crushed, and run through a 2 mm screen for examination. The sampling date was recorded on the sampling bags. After being oven-dried at 105℃, the soil samples were coarsely crushed and passed through a 2 mm sieve.

Statistical and laboratory analysis

Soil laboratory analysis

The soil samples have been delivered to Ambo University’s chemistry department in sampling bags to ascertain specific physical and chemical characteristics. The Ambo University Chemistry Laboratory examined the soil’s chemical characteristics, while the Ambo University Plant Science Laboratory examined its texture. The goal is to examine how different land use patterns impact soil property variability.

The following are the various techniques used to analyze the physicochemical characteristics of soil for each parameter.

To ascertain the moisture content, the field samples were first weighed, then dried for 24 h at 105 °C, and finally weighed once more29.

where; A is the soil’s weight after air drying, and B is the soil’s weight after oven drying, expressed in grams plus tin weight.

SOC is calculated by measuring a known quantity of 1N K2Cr2O7 solution, adding it to a known mass of soil in the presence of concentrated H2SO4 to kill the organic matter, and then titrating the excess with ferrous ammonium sulfate solution. A diphenylamine indicator is then used to identify the initial occurrence of unoxidized ferrous iron. Soil Wet combustion or dichromate oxidation was used to measure the amount of organic carbon30.

The following formula was then used to calculate the percentage of organic carbon:

A pH meter and an EC meter were used to measure the pH and electrical conductivity (EC) of a 1:5 soil water suspension31,32. The amount of available phosphorus (AvP) was calculated using the Olsen method. Soil organic carbon (SOC) was measured using the Walkley–Black method of wet digestion. The amount of SOM was calculated by multiplying SOC by 1.724, assuming that 58% of SOM is SOC33.

This study solely evaluated SOM based on assumptions and focused on SOC because it is used to assess soil quality. Soil samples were digested using the Kjeldahl equipment, and the total nitrogen content of the soil was calculated based on the amount of ammonia trapped34.

where N is the air-dried sample’s weight (g), mcf is a moisture correction factor, Vb and Vs are the sample’s and blank’s respective volumes (ml) of ferrous sulfate solution, and S is the ferrous sulfate solution’s normality (from blank titration).

Titrimetric techniques were used to quantify the amount of organic matter in the soil, and its contents could be calculated by multiplying the organic carbon content by 1.72430. Potassium dichromate in a sulfuric acid solution was used to oxidize soil organic materials under normal circumstances.

where 1.724 is the empirical factor, which is obtained by dividing 100 by 58, and %OC in the organic matter.

The sodium acetate method was employed to determine the cation exchange capacity (CEC). Five grams of soil is treated with ethanol and sodium acetate, and extraction is conducted using ammonium acetate solutions. The quantity of sodium (Na+) in the ammonium acetate extract is detected by a flame photometer for the determination of the soil’s CEC29. The bulk density and soil organic carbon (SOC) data are used to compute the soil carbon stocks (SCS) for every land use at a soil depth of 30 cm.

The total nitrogen content in the soil was determined using the Kjeldahl method, as described by34. This process involved oxidizing organic matter in the soil by treating it with concentrated sulfuric acid, which converted nitrogen present in organic compounds into ammonium sulfate. During distillation with sodium hydroxide (NaOH), ammonium ions (NH4⁺) were released and subsequently trapped by an acid solution. Boric acid was used to capture the released ammonium ions, and the final quantification was performed through back-titration with 0.02N sulfuric acid (H2SO4).

Total Nitrogen was calculated as

where a is the amount of H2SO4 needed for sample titration, and b is the amount of H2SO4 needed for blank titration S is the weight of the air-dried sample in grams N is Normality of H2SO4 (0.1N), nitrogen weight in grams (0.0014), and moisture correction factor (mcf).

A spectrophotometer was used to measure the amount of available phosphorous using the Olsen method, as explained by35.

where; a is mg/l P in the sample extract, b is mg/l P in black, s is sample weight in grams (5 g), mcf is moisture correction factor and 100 is ml of extracting solution.

Available Potassium was established by the flame photometer approach36,37. Available K was determined by;

where a is the flame reading (concentration of sample), b is the flame reading of blank, df is the dilution factor, mcf is the moisture correction factor, and S is the weight of air-dry soil.

Statistical analysis

The laboratory data were summarized using descriptive statistics, such as frequency distribution, mean, percentage, standard deviation, and cross-tabulation. SPSS 21 software was used for the analysis of quantitative data obtained from structured survey questionnaires. The statistical package SPSS v.21 was employed to evaluate the physicochemical characteristics of the soil. P < 0.05 would be considered significant for the mean values of the one-way ANOVA of soil parameters under the three land use categories.

A comparison was also made between the average values of each soil parameter and the benchmark established by other writers.

Results and discussions

Effects of land use types and slope to soil physical properties

Textural class

The study’s findings showed that the Cultivated land (CL) and Grazing land (GL) had loamy sand soils, while clay soils are found in forest land (FL) (Table 2). The variations in parent material, long-term land use changes, and soil formation throughout time could all contribute to the variations in textural class among land uses.38 found that land uses may have indirectly contributed to changes in soil textural class, particularly in the surface layers, as a result of long-term particle removal through pedogenic processes like weathering, deposition, transformation, and translocation.

These processes are controlled by management practices and can change soil texture. The current study was conducted concurrently with their findings. The 0–30 cm soil layer from which the samples were taken is dominated by the sand textural class.

In this study, there is high percentage of clay CL and lower in FL and middle in GL when it compared , whereas the quantities of sand and silt contents were not a uniform trend in all land uses did not showed trend uniformly across all land uses. Soil from CL had the highest silt concentration, while soil from FL had the lowest, followed by GL. The clay fractions showed a highly significant (p < 0.0070**) difference between land uses, whereas the sand and silt fractions showed a significant (p > 0.05) difference between land uses.

The soils of the GL had the highest mean sand fraction (27.3%), followed by the FL (22%), and the CL soils (18.70%), when taking into account the three land uses (Table 2).

The present result also revealed that there is no significant (P > 0.001) variation on the bulk density of soil slope gradient at an upper position of all three land used types.

This is because GL is susceptible to the percolation of clay and silt fraction resulting in the downward through percolation, while grasses are remove animals losing protecton. This study is in line with17, who reported the presence of higher sand fractions in GL than in other nearby natural FL and CL uses. Compared to soil under pasture and FL, the CL had a higher clay concentration. This can be the result of the silt particles becoming clay-sized as a result of extensive and ongoing farming. In a similar vein, the cultivated land’s subsurface soil has more clay than its topsoil. This demonstrates the increased clay transfer from surface soil brought on by extensive and ongoing cropping. This is corroborated by17, who hypothesizes that erosion’s selective removal of clay from the surface may be the cause of the low clay content in the surface soil of farmed fields19. Because diverse land use systems and management approaches influence the physical features of the soil, they also found that soils of the same region with the same soil type and textural class but distinct land use systems differed in a few other soil physical parameters.

Though the HL recorded the greatest mean value (11.62%), the mean clay concentration in the surface layer (0–30 cm) was lower in CL (8.43%) and lowest in GL (5.00%) (Table 2). The lowest clay in GL surface layers and lower in CL may be caused by tillage activities in CL, erosion that removes clay from the surface selectively, weathering, and other pedogenetic processes that change clay minerals into other minerals.

This is consistent with the earlier research conducted in the Abobo region of western Ethiopia by17.

Bulk densities

The bulk densities of soils across the different land use types revealed important insights into soil compaction and porosity. Fl has the lowest BD at 0.83 g/cm3, indicating a relatively loose and porous soil structure. This lower BD is typical of undisturbed FL, which tends to have more OM, greater pore space, and less compaction. It allows for better water infiltration, root growth, and aeration.

Grassland soils have a BD of 1.15 g/cm3, which is higher than FL but still within a range that suggests moderate compaction. GL soils are often exposed to grazing and other land uses, which can increase soil density, though they still retain sufficient porosity for healthy plant growth. The CL has the highest BD at 1.55 g/cm3, reflecting significant compaction due to agricultural activities such as plowing, tilling, and machinery use. Higher BD in CL soils indicates reduced pore space, leading to poor water infiltration, reduced root penetration, and potential soil erosion. This compaction can negatively impact soil health and crop productivity, requiring management practices like conservation tillage or organic amendments to improve soil structure. The progressive increase in BD from FL to CL highlights the impacts of land use on soil compaction, with natural ecosystems like forests maintaining better soil structure than areas under intensive agricultural use (Table 2).

The primary causes of the FL having the lowest soil BD may be the higher clay content and less soil disturbance beneath FL. The enhanced BD of soil in CL may be caused by plowing in agricultural soils, which tends to diminish the quantity of Organic Matter (OM) in that soil by animal trafficking and exposes the soil surface to direct raindrop hits. This outcome is in line with that of39, who found that at a soil depth of 0–20 cm, the highest BD was found under CL in comparison to the nearby pasture and FL. The current findings indicated that the slope gradient had a minor effect on soil bulk density (P > 0.001), so direct bulk density for FL, GL and CL is shown without slope (Table 2)”.

This study is consistent with40,41, who also proposed that, at a soil depth of 0–30 cm, the BD of CL was greater than that of nearby GL and forest fields. Ironically, at soil levels of 0–10 cm, 20–30 cm, and 30–40 cm,42 also discovered a greater BD in the GL than in the nearby bare land and rehabilitated land.

In most cases, the BD values found in this investigation close to fall between the limits predicted by43 for most mineral soils (1.1 to 1.4 g cm−3). Given that the BD of this study area was within the anticipated range, the water movement and aeration within the soil structure are in a favorable state that promotes plant growth and controls the quantity and variety of soil microbes, which in turn provide a variety of uses in agricultural operations.

Effects of land uses on selected soil chemical properties

pH H2O (1:2.5) and electrical conductivity

The solubility and availability of nutrients in the soil are impacted by the pH of the soil, according to the findings of31. The primary regulators of soil pH are exchange reactions between the surfaces of soil particles and soil solution.

The result of the study revealed that a lower soil pH value (5.24) was recorded in the CL; this would be responsible for the relatively lower Soil Organic Carbon (SOC) consistency. This is in agreement with31, who reported that soil pH determines the availability of nutrients and their solubility in the soil. The primary regulators of soil pH are exchange reactions between the surfaces of soil particles and soil solution.

The analysis of GLM results indicated that the soils pH-H2 O and EC were not significantly affected at the upper and lower slope gradient of land use types (P > 0.01) but only significant at the middle layer and mean recorded at three land use types showing as condition acidic (5.80).

In general, the mean pH-H2O values of the soil under the FL, GL, and CL were 6.06, 6.12, and 5.24, respectively (Table 3).

According to Murphy (1968), Soil pH levels are categorized as 6.1–6.5 as slightly acidic (moderately alkaline), 5.1–5.5 as strong acids, 5.6–6.0 as moderately acidic, and below 5.0 as very strong acids. According to the aforementioned category system, the research area’s FL and GL oils were classified as moderately to slightly acidic, whereas the CL were classified as having a very acidic pH. The CL had the lowest mean soil response value when compared to the other nearby land use types. The reason for this could be because agricultural fields are depleting basic cations.

This is in harmony with the study results of44, who reported that CL had the lowest pH of soil when compared to nearby FL and GL. These study results were also supported by the findings of41, who showed that at a soil depth of 0–30 cm, the soil reaction was lower under CL than under FL and grazing pastures. The cropland’s low pH values were acidic, which may have been caused by high rates of inorganic fertilizer applications (such as ammonium fertilizers), frequent tillage, and a lack of organic matter due to erosion and/or aluminum toxicity. According to the report of45, low soil pH prevents the soil’s CEC by altering the surface charge of colloids, or the smallest clay particles, and SOM. Because nutrients are weekly absorbed and may, therefore, seep out, low CEC indicates that the soil will contain fewer exchangeable cations needed as crop nutrients.

The types of land use and slope classifications had no discernible effects on the EC values of the soils (P > 0.01). The FL, GL, and CL had the highest (0.08 dS m-1), lowest (0.02 dS m), and 0.03 dS /m) EC among the soils, respectively, when taking into account the mean registered land use categories (Table 3). Given the low BD of the GL, the loss of base-forming cations due to significant water percolation may be the cause of the lowest EC value beneath it.

The result of this study is also consistent with46, who discovered that at 0–30 cm of soil depth, GL had poorer EC than nearby CL, bushlands, and bushed grasslands. The EC values assessed under all land use types in the study region showed that the concentration of soluble salts is below the levels at which the growth and productivity of the majority of crops are affected, as per47 standard classification of EC values. This indicates that the research area has a favorable precipitation-to-evaporation ratio, suggesting that salinity is unlikely to pose a significant constraint on plant growth and agricultural productivity.

Soil organic carbon

The amount of SOC in this study was significantly (P < 0.05) impacted by slope gradient and land-use change (Table 4). Through the breakdown of plant and animal waste, root exudates, living and dead microbes, and soil biota, SOC enters the soil. Plant nutrition, biological activity in the soil, and soil fertility status are all significantly impacted by SOM38.48 state that the SOC is very high in forest areas and lower in both GL and CL.

The amount of SOC varies greatly depending on the land use scheme. The concentration of SOC was found to be 7.06, 2.57, and 2.78% in FL, GL, and CL, respectively, and was found to be in the order of Forest > cultivated land > Grassland (Table 4). It could be attributed to improved aeration that promoted the mineralization of SOC or owing to the little or no return of plant residues and manures into the soils.

The modification of FL ecosystems to other types of land cover may result in a decline in soil organic carbon (SOC), due to variations in soil moisture content (SMC) and temperature regimes, as well as the succession of plant species with varying amounts and quality of biomass returned to the soil8. According to49, SOM was reduced by 48.8% as a result of deforestation and subsequent cultivation. Furthermore, because macro-aggregates are disturbed when FL is turned into CL, it is recognized that this degrades the physical characteristics of the soil and increases the land’s vulnerability to erosion50. According to51, SOC is a significant indicator for determining the potential productivity of soil. The relative presence of higher SOC in FL soils could be due to a relatively better return of biomass for decomposition from plant leaves. This outcome is comparable to that of52, who found that SOC exhibits notable variance in slope gradient and land use change.

Soil organic matter (SOM)

The result of the study revealed that there is a high amount of SOM in FL 12.8%, followed by CL 4.79%. There is no significant (0.05) along the land uses. Because soil erosion and decomposition were more active in CL than in FL, the faster decline in SOM levels in CL might be explained by these processes’ accelerated rates53. Water and soil were deposited on FL as a result of land management techniques like poorly designed terracing and cutoff drainage that were used on CL. Topsoil removal on the CL is also made easier by the region’s farming system, which mainly relies on traditional methods. This study is in agreement with54, who reported that SOM demonstrates a strong response to land use, land use change, and land degradation. Thus, the high SOM in FL is potentially the highest reservoir for the plant’s essential nutrients, nitrogen, phosphorus, and sulfur55. Additionally, SOM improves soil aggregation and the structure of forest land soils while raising soil water-holding capacity and CEC.

Available phosphorus (AP)

All 3 land use systems had higher amounts of AP, with average values of 70.7, 33.34, and 26.51 mg kg−1 in CL, FL, and GL, respectively. There is a relatively higher concentration of AP 70.7 mg kg−1 contained in the natural FL than other land use regimes due to high OM, which releases phosphorus during its mineralization. As soil depth increased, AP declined throughout all forms of land usage. This could be because the amount of clay increases and the amount of organic matter decreases with increasing soil depth.

The results of the General Linear Model (GLM) test analysis demonstrated that while the available phosphorus (AP) of the study area varied significantly across all slope categories, land use patterns had no discernible effect (P > 0.01) on it. This suggests that topographic variations play a more dominant role in AP distribution than land use itself, which is consistent with findings from previous studies56. The highest mean AP value was recorded in forest land compared to cultivated and grazing land (Table 4). This is likely due to the accumulation of organic matter and minimal soil disturbance in forest ecosystems, which enhance phosphorus retention and mineralization57.

Generally speaking, variations in available P concentrations in soils may be associated with differences in soil weathering intensity and disturbance under different land use types. In undisturbed forested soils, organic phosphorus mineralization through microbial activity provides a steady supply of available P, while in agricultural and grazing lands, soil degradation and erosion contribute to P depletion58. When considering the main effects of land use types, the available P was highest in forest land (70.7 mg kg⁻1) and lowest in grazed and cultivated land (33.34 mg kg−1) (Table 4). These findings align with59, who also observed that forest land exhibited higher available P compared to adjacent grassland and cultivated soils, reinforcing the notion that natural ecosystems play a critical role in maintaining soil nutrient status.

One possible explanation for the relatively large amount of available P in the forest land is that the high amount of OM causes organic phosphorus to be released, increasing the amount of P that is available beneath the forest land. Forest land provided greater accessible P than grass and cultivated land at a soil depth of 0–30 cm40. Additionally,41 discovered that forest land had more available P at different soil layers than cultivated and grazed areas.

Comparing the various land use types in the study area, the forest had the most accessible P, followed by cultivated land and grass. The P reduction effects in the land may be due to the absence of nitrogen phosphorous sulfur (NPS) and diammonium phosphate (DAP) fertilizer application on the cultivated soils in the studied region. Although cultivated land displayed lower in available P content from the forestland and grass land, which is possible due to crop mining, crop residue clearance, and erosion, however the available P levels of the soils of the study area under all land uses were typically high.

Basic exchangeable cations

Exchangeable calcium (Ca) levels were significantly (P < 0.05) impacted by land use and slope gradient (Table 5). Different management techniques, land utility methods, and other imbalances proportionate to soil texture and OM may be the cause of the large difference in exchangeable calcium. According to Table 5, the average exchangeable calcium values in CL, GL, and FL were 6.10, 7.17, and 13.17 cmol kg−1, respectively.

All slope categories of the land-used type had a substantial impact on both Ca and Mg when taking into account the slope gradient of the three land-used types. However, the impact of land use on exchangeable Mg concentration was negligible (P > 0.05). FL, GL, and CL were found to have mean exchangeable Mg values of 8.47, 3.58, and 2.93 cmol kg−1, respectively. The influence of intensive cultivation and a bountiful crop yield with little to no input utilization may be the cause of the lowest values found in the farmed area.

Different types of land use had no significant effect on exchangeable K content (P = 0.05). The forestland had the highest exchangeable K content (2.56 cmol/kg), followed by the cultivated land (2.21 cmol/kg) and the cultivated land (2.05 cmol/kg) (Table 5).

The findings of this study showed that high K was found in tropical soils with high pH, and the highest content in the FL was associated with its high pH value. Generally speaking, the lower K levels in the CL compared to other land uses may be caused by ongoing losses in the plant components that are harvested. These elements, together with the use of fertilizers that produce acid, have also been taken into account in earlier research as significant determinants of K distribution in soil systems, primarily contributing to its depletion, particularly in tropical soils.

Overall, the findings indicate that mean soil exchangeable Na varied considerably with land use types (P < 0.01) and that the upper layer of the samples’ slope had a considerable impact whereas the middle and lower layers had no effect (Table 5). The lowest element in the exchange complex was the concentration of exchangeable Na+.

The mean soil exchangeable Na+ concentrations were 0.58 cmol/kg and 0.39 cmol/kg in soils under the forest land use system and 0.55 cmol/kg in soils under the agriculture land use system. This could be because the low pH of the soil beneath the crops would cause the exchangeable bases to become immobile, lowering soil base saturation and possibly eventually leading to the depletion of soil exchangeable bases.

Cation exchange capacity (CEC)

GLM results showed that the land use categories had a significant (P < 0.00) influence on the soils’ cation exchange capacity (CEC) in the research area. According to Table 4, the CEC mean values in croplands, grazing, and forests were 26.26, 27.61, and 49.86 cmol kg-1, respectively. According to this study’s findings, the cation exchange capacity (CEC) of forest land was somewhat greater than that of the three nearby land use groups. This observation aligns with previous research indicating that forest soils generally exhibit higher CEC due to their richer organic matter (OM) content60. Organic matter plays a crucial role in soil CEC by providing negatively charged sites that facilitate cation retention48. The reduction in CEC values observed in agricultural land use is primarily attributed to the decrease in OM content. Intensive agricultural practices, such as continuous cropping and excessive tillage, accelerate organic matter decomposition and lead to soil degradation23. Moreover, the removal of vegetation cover in agricultural systems contributes to soil erosion and the loss of organic matter, further diminishing the soil’s ability to retain essential nutrients61.

The proportions and/or kinds of the two primary colloidal materials, clay, and humus, define the CEC of soil. Compared to clay particles, organic matter offers more negatively charged surfaces, which makes it more significant in soil exchange activities. This outcome supports the findings of62, which proposed that the CEC of soil was higher in Forest land than in nearby Agricultural and Grazing areas. Furthermore, the CEC value of the soil under cultivated, grazed, and forest land was in the range of high rate, while it was classified as very high under the Forest land63.

Conclusion and recommendations

Soil physicochemical properties were significantly affected by land use types. BD was lowest in FL use type, whereas EC, OC, SOM, Av. P, Tot. N, CEC, and exchangeable were found to be higher in FL, followed by decreasing order in GL and CL. Only PH was higher in GL. The higher values of soil properties in forest land (FL) are due to minimal disturbance and continuous organic matter input, which enhance soil fertility and structure, resulting in lower bulk density. Grassland (GL) has moderate input, while cultivated land (CL) is more disturbed, leading to nutrient loss and compaction. The higher pH in GL may result from lower organic acid input compared to FL. In contrast to this, the cases of GL and agricultural land were registered in dissimilar trends in each other’s land use types. The findings of the study demonstrated that the type of land use had a substantial impact on soil pH, base cation (Na+) concentrations, and CEC. Significant alterations in the chemical characteristics of soils were observed in this study as a result of the conversion of native FL to CL. Significant variations were found in the pH, OC, TN, Ca, Na, and K of soils taken from three different land-use types in the Liben Jawi.

Most crop plants’ growth is restricted, which eventually results in a drop in crop productivity and yields. Additionally, agriculture on steep slopes and marginal regions has been brought about by population pressure. The study’s findings provide proof of notable alterations in the soil quality within the study area. The soils of the farmed area after removal or destruction had a detrimental impact on the majority of the criteria. In the forest to cultivated soils, PH and OM drastically decreased from 6.4 to 5.6 and from 8.1 to 3.8%, respectively. The farmed land’s soil has a moderate acidity level. In contrast, the ratios of carbon–nitrogen, exchangeable sodium, and EC were not significantly affected by changes in land use (P > 0.05). The total nitrogen in forestland soils decreased from 0.4 to 0.19 when compared to soils on cultivated land.

From the forest to the cultivated land soils, land use successions decreased the Cation exchange capacity and percent base saturation levels from 75 to 35 and 99 to 62.6%, respectively. As anticipated, the soils in the forest and the cultivated land had the highest and lowest N values, respectively. This has significant effects on soil deterioration and agricultural output, which eventually lead to decreased soil fertility and land productivity.

The overall amount of nutrients accessible to plants as exchangeable cations is dependent on soil CEC, which is also important for soil fertility since it changes the pH of soils by influencing the extent to which H and Al ions occupy the exchange complex. In contrast, the cultivated land had the highest accessible P level (4.40 mg kg−1) when compared to the other nearby land use systems. This could be because inorganic P fertilizer was applied to the crop fields. These differences in the physicochemical characteristics of the soil between land use types show how precarious the region’s sustainable crop production is.

As a result, to maintain sustainable agricultural production, issues in the watershed must be resolved. This can be done by developing appropriate management strategies, which will help Ethiopians overcome many of the obstacles they face in the areas of crop and livestock production as well as in their attempts to manage natural resources for sustainable development. The carbon-to-nitrogen (C:N) ratio did not differ significantly among land use types and therefore should not be emphasized in the conclusions.

Based on these findings, the following specific recommendations are proposed to improve and sustain soil fertility and agricultural productivity in the region.

To address the significant decline in soil fertility and productivity resulting from land-use changes in the Liben Jawi area, it is essential to implement sustainable land-use planning and management practices. This entails encouraging reforestation initiatives, soil conservation practices, and the application of organic soil amendments to enhance the nutritional content and soil structure, especially in farmed areas. In addition, integrated watershed management should be prioritized to prevent soil erosion on marginal lands and steep slopes.

Increased awareness and knowledge about soil properties among farmers will aid in designing and applying appropriate land-use strategies, ultimately ensuring sustainable agricultural production and natural resource management for long-term development in the region.

Data availability

The authors declare that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the pape.

Abbreviations

- AvP:

-

Available phosphorus

- BD:

-

Bulk density

- CEC:

-

Cat ion exchangeable capacity

- CSA:

-

Central Statistical Agency

- Cm:

-

Centimeter

- EEA:

-

European Environment Agency

- EC:

-

Electrical conductivities

- EPA:

-

Environmental protection authority

- EXB:

-

Exchangeable bases

- FAO:

-

Food and Agricultural Organization

- GLM:

-

General linear model

- GDP:

-

Gross domestic product

- GPS:

-

Geographic position system

- IBIDEM:

-

The same as that

- LJDANRO:

-

Liban Jawi District Agricultural and Natural Resource Office

- OC:

-

Organic carbon

- SOM:

-

Soil organic matter

- IUSS :

-

International union soil sciences

- NRCS:

-

Natural Resources and Conservation Society

- Tot. N:

-

Total nitrogen

References

Habtamu, A. Land Use/Land covers change and Impacts of Jatropha on Soil Fertility: The Case of Mieso and Bati Districts, Ethiopia (M.Sc. Thesis) Haramaya University, Ethiopia, 11–30 (2011).

Behailu, A. Land Use and Land Cover Analysis and Modeling in South Western Ethiopia: The Case of Selected Resettlement Kebeles in GimboWoreda. MSc Thesis, Addis Ababa University, Addis Ababa (2010).

FAO. The State of the World’s Land and Water Resources for Food and Agriculture: Managing Systems at Risk. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (2017).

IPCC. Climate Change and Land: An IPCC Special Report on Climate Change, Desertification, Land Degradation, Sustainable Land Management, Food Security, and Greenhouse Gas Fluxes in Terrestrial Ecosystems. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (2019).

World Bank. Transforming Agricultural Land Management to Combat Climate Change. The World Bank Group (2021).

UNEP. Global Environmental Outlook 6: Healthy Planet, Healthy People. United Nations Environment Programme (2020).

Liu, Y., Wu, K. & Cao, H. Land-use change and its driving factors in Henan province from 1995 to 2015. Arab. J. Geosci. 15(3), 247 (2022).

Offiong, R. A. & Iwara, A. I. Quantifying the stock of soil organic carbon using multiple regression model in a fallow vegetation, Southern Nigeria. Ethiop. J. Environ. Stud. Manag. 5(2), 166–172 (2012).

Kebebew, S., Bedadi, B., Erkossa, T., Yimer, F. & Wogi, L. Effect of different land-use types on soil properties in Cheha District, South-Central Ethiopia. Sustainability 14, 1323 (2022).

Bai, Z., Zhang, X., & De Jong, R. Land degradation expanding by 1 million sq km annually. The Guardian. Retrieved from theguardian.com (2024).

FAO. Scarcity and degradation of land and water: Growing threat to food security. Retrieved from https://www.fao.org/home/eng (2021).

Yimer, F., Belay, T. & Getachew, H. Influence of land-use types and topographic slopes on the physico-chemical properties of soils in the Ageza watershed, Northwestern Ethiopia. Front. Soil Sci. https://doi.org/10.3389/fsoil.2024.1463315 (2024).

Alemayehu, W., Woldemariam, A. & Tadele, M. Dynamics of soil physical and chemical properties under different land use types and altitudinal gradients in the Sala Watershed, South Ethiopia. Int. J. Agron. https://doi.org/10.1155/2024/7389265 (2024).

Attanda, M. Impact of land use effect on chemical and physical soil characteristics in Colline department of Benin. Centre National d´Agro-Pédologie/Institut National des Recherches Agricoles du Bénin01 B.P. 988 Cotonou Béninigue_attanda@yahoo.fr. (2008).

Esmaeil, S., Mousa, A., Isa, J. & Elham, S. Land use management response on carbon sequestration and soil properties (case study: Kalpoush Plain, Golestan province). Int. J. Agric.: Res. Rev. 3(2), 299–304 (2013).

Abera, B. Factors Influencing the adoption of soil conservation practices in Northwestern Ethiopia. Discussion Papers No. 37.Institute of Rural Development 229–235 (University of Goettingn, German, 2023).

Teshome, Y., Heluf, G., Kibebew, K. & Sheleme, B. Impacts of land use on selected physicochemical properties of soils of Abobo Area, Western Ethiopia. Agric., For. Fisheries 2(5), 177–183 (2013).

Guyalo, A. K., Alemu, E. A. & Degaga, D. T. Impact of large-scale agricultural investments on the food security status of local community in Gambella region, Ethiopia. Agric. Food Secur. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40066-022-00381-6 (2022).

Achalu, G., Heluf, K. K. & Abi, T. Status of selected physicochemical properties of soils under different land use systems of Western Oromia, Ethiopia. J. Biodiv. Environ. Sci. 2(3), 57–71 (2012).

Tadesse, G., Belay, K. & Abebe, Y. The impact of land use changes on soil erosion and soil fertility in Ethiopia. Land Degrad. Dev. 24(1), 1–9 (2013).

Lal, R. Soil carbon sequestration impacts on global climate change and food security. Science 304(5677), 1623–1627 (2004).

Gete, Z., Yohannes, F., & Mitiku, H. Soil Erosion and Conservation in Ethiopia: A Research Review (National Soil Resources Institute, 2006).

Lal, R. Sustainable Intensification to Advance Food Security and Enhance Climate Resilience in Africa (Springer International Publishing, 2015)

Lal, R. Regenerative agriculture for soil carbon sequestration and climate adaptation. J. Soil Water Conserv. 75(5), 123A-129A (2020).

Hurni, H., Giger, M. & Liniger, H. Promoting sustainable land management in developing countries: The case of Ethiopia. Environ. Manage. 56(1), 24–36 (2015).

LJDANRO (Liban Jawi District Agricultural and Natural Resource Office), (2019) (unpublished).

Belay, B., Regasa, T. & Mammo, S. Woody plant species composition, structure, and regeneration status of ruruki forest of Liban Jawi District, West Shewa Zone, Oromia Regional State, Ethiopia. BMC Ecol. Evolut. 25(1), 1–12 (2025).

Central Statistical Agency (CSA). Population Projection of Ethiopia for All Regions at Woreda Level from 2014–2017 (Addis Ababa, Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia, 2013).

Sertsu, S., & Bekele, T. Procedures for Soil and Plant Analysis. National Soil Research Center, Ethiopian Agricultural Research Organization (Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 2000).

Walkley, A. & Black, I. A. An examination of the Degtjareff method for determining soil organic matter and a proposed modification of the chromic acid titration method. Soil Sci. 37(1), 29–38 (1934).

Baruah, T. C., & Bathakur, P. C. A Textbook of Soil Analysis (Vikas Publishing House, 1997).

Jackson, M. L. Soil Chemical Analysis: Advanced Course. Published by the author, (University of Wisconsin, 1973).

Nelson, D. W., & Sommers, L. E. Total Carbon, Organic Carbon, and Organic Matter. in Methods of Soil Analysis: Part 2—Chemical and Microbiological Properties 539–579 (American Society of Agronomy, Inc., 1982).

Bremner, J. M. Nitrogen-Total. in Methods of Soil Analysis. Part 3. Chemical Methods (ed D. L. Sparks) 1085–1121. (Soil Science Society of America, 1996).

Olsen, S. R., & Sommers, L. E. Phosphorus. in Methods of Soil Analysis: Part 2 – Chemical and Microbiological Properties 403–430. (American Society of Agronomy, Inc., 1982)

Chapman, H. D. Cation exchange capacity. in Methods of Soil Analysis: Part 2—Chemical and Microbiological Properties 891–901. (American Society of Agronomy, 1965).

Rowell, D. L. Soil Science: Methods and Applications. (Longman Scientific & Technical, 1994).

Brady, N. and Weil, R. The Nature and Properties of Soil, 14th edn (Upper Saddle River, Prentice Hall, NJ, 2008).

Yitbarek, M., Kassa, H. & Abebe, M. Effects of land use and land management on soil properties in the highlands of Ethiopia. Ethiop. J. Nat. Resour. 15(1), 35–54 (2013).

Abad, M., Rodriguez, A. & Martin, M. Effects of agricultural management on soil quality indicators in Mediterranean agroecosystems. Geoderma 218–219, 112–122 (2014).

Takele, L., Chimdi, A. & Abebaw, A. Dynamics of Soil fertility as i nfluenced by different land use systems and soil depth in West Showa zone, Gindeberet district, Ethiopia. Agric., For. Fisheries 3(6), 489–494 (2014).

Lelisa, A. & Abebaw, D. Effects of land use change on soil properties and crop productivity in the central highlands of Ethiopia. J. Soil Sci. Environ. Manag. 7(8), 128–134 (2016).

Gupta, P. K. Handbook of soil, fertilizer and manure 431 (Anis offset Press, New Delhi, 2000).

Bore, G. & Bedadi, B. Impacts of land use types on selected soil physico-chemical properties of Loma Woreda, Dawuro Zone, Southern Ethiopia. Sci. Technol. Arts Res. J. 4(4), 40–48 (2015).

McCauley, A., Cook, S. & Vance, G. Soil quality and crop production in the northern Great Plains. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 69(3), 808–819 (2005).

Mesele, S., Gebrekidan, H., Gizachew, L. & Layne, C. Changes in land cover and soil conditions for the Yabelo district of the Borana plateau, 1973–2003 4 (University of California, Davis, 2006).

Landon, J. Booker tropical soil manual: A handbook for soil survey and agricultural land evaluation in the tropics and subtropics 530 (John Wiley & Sons. Inc., New York, USA, 1991).

Hazelton, P., & Murphy, B. Interpreting Soil Test Results: What Do All the Numbers Mean? (CSIRO Publishing, 2016).

Evrendilek, F., Celik, I. & Kilic, C. Changes in soil organic carbon and other physical soil properties along adjacent Mediterranean forest, grassland, and cropland ecosystems in Turkey. J. Arid Environ. 59, 743–752 (2004).

Çelik, I. Land use effects on organic matter and physical properties of soil in a southern Mediterranean highland of Turkey. Soil Tillage Res. 83, 270–277 (2005).

Shukla, M. K., Lal, R. & Ebinger, M. Determining soil quality indicators by factor analysis. Soil Tillage Res. 87, 194–204 (2006).

Seifu, W., Elias, E., Gebresamuel, G. & Khanal, S. Impact of land use type and altitudinal gradient on topsoil organic carbon and nitrogen stocks in the semi-arid watershed of northern Ethiopia. Heliyon 7(4), e06770 (2021).

Abegaz, A., Winowiecki, A. A., Vågen, T.-G., Langan, S. & Smith, J. U. Spatial and temporal dynamics of soil organic carbon in landscapes of the upper Blue Nile Basin of the. Agr. Ecosyst. Environ. 218, 190–208 (2016).

Vågen, T.-G., Winowiecki, L. A., Abegaz, A. & Hadgu, K. M. Landsat-based approaches for mapping of land degradation prevalence and soil functional properties in Ethiopia. Remote Sens. Environ. 134, 266–275 (2013).

Zeng, D. H., Hu, Y. L., Chang, S. X. & Fan, Z. P. Land cover change effects on soil chemical and biological properties after planting Mongolian pine in sandy lands in Keerqin, northeastern China. Plant Soil 317, 121–133 (2009).

Yang, X., Zhang, X. & Fang, H. Phosphorus fractions and availability in a paddy soil as influenced by land use changes. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 82(1), 112–121 (2018).

Tiessen, H. & Moir, J. O. Phosphorus forms and availability in tropical soils. Nutr. Cycl. Agroecosyst. 81(3), 257–270 (2008).

Shen, J. et al. Phosphorus dynamics: From soil to plant. Plant Physiol. 156(3), 997–1005 (2011).

Chemada, F., Tesfaye, B. & Fekadu, D. Effects of land use change on soil properties and fertility in the central highlands of Ethiopia. J. Soil Sci. Environ. Manag. 8(5), 104–113 (2017).

Brady, N. C., & Weil, R. R. The Nature and Properties of Soils 15th edn (Pearson, 2016).

Six, J., Conant, R. T., Paul, E. A. & Paustian, K. Stabilization mechanisms of soil organic matter: Implications for C-saturation of soils. Plant Soil 241(2), 155–176 (2002).

Ahukaemere, C., Ndukwu, B. & Agim, L. Soil quality and soil degradation as influenced by agricultural land use types in the humid environment. Int. J. Forest, Soil Erosion. 2(4), 23–28 (2012).

Thomas, G. W. Exchangeable cations. In Methods of Soil Analysis: Part 2—Chemical and Microbiological Properties 159–166 (American Society of Agronomy, Inc., 1982)

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge all individuals or organizations who provided assistance or support during the research work.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.A .collected data, K.F. wrote the 1st draft Manuscript, S.M. supervised the data collection and edited the manuscript,

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

The authors have complied with all ethical standards while writing the article and conducting the research.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Abile, H., Fituma, K. & mammo, S. Impact of land use types on selected soil physicochemical parameters in the case of Liben Jawi district, Ethiopia. Sci Rep 15, 27944 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-12784-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-12784-z