Abstract

Microplastics (MPs) and nanoplastics (NPs) have emerged as major environmental pollutants due to their persistence, widespread distribution, and ability to interact with organic contaminants, including antibiotics. This study employs molecular dynamics (MD) simulations to investigate the adsorption mechanisms of three commonly used antibiotics—ciprofloxacin, amoxicillin, and tetracycline—on two types of non-biodegradable microplastics: polypropylene (PP) and polystyrene (PS). Furthermore, the impact of microplastic aging, simulated by introducing oxidized and hydrophilic functional groups, on adsorption efficiency and interaction mechanisms has been explored. The total interaction energy of ciprofloxacin on polystyrene increased from − 121.57 kJ/mol (pristine) to -242.04 kJ/mol (aged), while the number of adsorbed molecules doubled from 5 to 10. Similarly, amoxicillin adsorption on aged polypropylene increased from 4 to 6 molecules, with total adsorption energy increasing from − 52.14 kJ/mol to -93.43 kJ/mol. Polystyrene microplastics demonstrated stronger adsorption than polypropylene, particularly for aromatic antibiotics like ciprofloxacin, where π-π interactions dominate. The Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD), Radial Distribution Function (RDF), and Mean Squared Displacement (MSD) analyses further confirm the stability and persistence of these interactions. Additionally, the hydrogen bond analysis highlights the role of microplastic aging in facilitating stronger antibiotic binding. These findings suggest that aged microplastics act as potent carriers of antibiotics, potentially prolonging their environmental persistence and influencing microbial resistance patterns. The results reveal that, aged microplastics exhibit significantly higher antibiotic adsorption due to increased surface roughness and enhanced electrostatic interactions. By providing molecular-level insights into MP-antibiotic interactions, this study contributes to the broader understanding of emerging pollutants.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Plastics, recognized as one of the most significant inventions of the 20th century, are valued for their lightweight nature, strong chemical stability, outstanding impact resistance, and cost-effectiveness1,2,3. These qualities have led to their widespread use across diverse sectors, including commerce, industry, agriculture, aerospace, and everyday life4. In 1950, global plastic production was around 2 million tons per year5 but according to recent estimates, global plastic production exceeded 460 million metric tons in 2024 (https://iucn.org), emphasizing the persistent increase in plastic manufacturing and the urgent need to address the environmental impacts of microplastic pollution.

By 2050, global plastic production is projected to reach 33 billion tons6. However, approximately 65% of plastics are unsuitable for recycling7. Leading to the widespread release of a significant amount into the natural environment8,9.

Additionally, due to the COVID-19 pandemic, approximately 5.8 billion face masks— a potential source of microplastics—are used once and discarded daily, with 2.4 billion ending up in landfills10. Plastics degrade slowly over time, gradually breaking down into microplastics ( particles smaller than 5 mm in diameter) and even nanoplastics (particles less than 0.1–1 μm)11.

The most frequently detected microplastics include polyethylene (PE) and polystyrene (PS), followed by polypropylene (PP), polyvinyl chloride (PVC), polyethylene terephthalate (PET), polyamide (PA), and polyvinyl alcohol (PVA)12. Due to their slow degradation, microplastics accumulate and remain in the environment for extended periods, where they can interact with living organisms13.

Microplastics (MPs) and nanoplastics (NPs) have emerged as major environmental concerns due to their widespread distribution across ecosystems and their ability to transport and accumulate organic pollutants such as pesticides, pharmaceuticals, and industrial chemicals. Many of these pollutants pose risks to aquatic life and can bioaccumulate in the food chain. The adsorption of organic pollutants onto microplastics is a complex process influenced by various factors, including the physicochemical properties of both the plastics and the contaminants. Understanding this interaction is essential for evaluating the environmental impact of microplastics and developing effective mitigation strategies, highlighting the importance of studying them14.

In addition, the discovery of antibiotics was a major milestone in human efforts to prevent diseases and treat secondary infections. Their use has expanded beyond human medicine to include disease prevention in animals, protection against bacterial crop damage, and applications in aquaculture as growth enhancers and prophylactics15,16,17,18. However, this extensive usage has also led to the emergence of antibiotic pollutants, raising significant global concerns due to their widespread negative impact on public health and the environment19,20.

Microplastics can adsorb, accumulate, and transport pollutants such as organic contaminants, metals, and microorganisms21 due to their large surface area and high hydrophobicity, increasing their potential toxicity in aquatic ecosystems22,23. Furthermore, the interaction between MPs and these pollutants can lead to bioaccumulation through the food chain, ultimately posing risks to human health24. Among various emerging contaminants, antibiotics have drawn significant attention due to their accumulation, as they can promote the development, spread, and persistence of antibiotic-resistant bacteria and resistance genes25,26.

Microplastics undergo different aging processes, such as biodegradation, physical wear, and chemical oxidation27. Numerous studies have shown that the aging process can alter the surface structure28. Aged microplastics exhibit different toxic effects compared to pristine MPs due to changes in their morphology and chemical composition. Aging typically reduces the size of MPs, making them smaller and more easily ingested due to biological size constraints29,30,31.

At the same time, the altered properties of microplastics due to aging can influence their interactions with environmental pollutants32,33which in turn impacts their ingestion by organisms and the associated risks34. These transformations complicate our understanding of how microplastics interact with antibiotics in real-world scenarios, underscoring the importance of studying both pristine and aged microplastics.

Gao et al. discuss various laboratory simulations of microplastic aging, highlighting the formation of oxygen-containing functional groups such as hydroxyl and carbonyl groups. They also investigate how these changes affect the physicochemical properties of microplastics and their interactions with environmental pollutants35. Liu et al. also explore the role of reactive oxygen species in the aging process of microplastics, leading to the introduction of functional groups like hydroxyl and carbonyl on the polymer surface. The research provides insights into how these chemical modifications influence the environmental behavior of aged microplastics36. As well as Chelomin et al. investigate the toxicological effects of aged microplastics, focusing on the increased presence of oxygen-containing functional groups such as carbonyl and carboxyl groups. Their study discusses how these chemical changes enhance the adsorption capacity of microplastics for various pollutants, thereby influencing their environmental impact37.

Batch adsorption experiments are commonly conducted to determine the adsorption behavior of pollutants and the capacity of various plastic materials, involving the addition of a known pollutant concentration to a specified amount of plastic. However, these experiments can be inefficient. This study explores an alternative theoretical approach, highlighting molecular dynamics (MD) as a valuable tool for examining adsorbent-adsorbate interactions at the molecular level. MD not only provides detailed insights into these interactions but also offers a visual representation of the adsorption process. These approaches are relatively cost-effective and have the potential to minimize reliance on wasteful and unsustainable experimental methods.

MD predicts how each atom in a molecular system moves over time by utilizing a physical model that describes interatomic and intermolecular interactions. Crucially, MD simulations offer valuable insights into the specific interactions between adsorbents and adsorbates, providing a detailed and fundamental understanding of the adsorption process38.

This study seeks to address these gaps by leveraging molecular dynamics simulations to investigate:

-

1.

The adsorption mechanisms of widely used antibiotics (e.g., ciprofloxacin, amoxicillin, and tetracycline) on non-biodegradable microplastics (e.g. polypropylene, and polystyrene).

-

2.

The influence of environmental aging on the adsorption efficiency and interaction mechanisms by introducing oxidized and hydrophilic functional groups to microplastic surfaces.

This study offers practical relevance by elucidating the adsorption mechanisms of widely used antibiotics onto environmentally abundant microplastics under realistic conditions, including oxidative aging. These insights enhance our understanding of how microplastics contribute to the transport and persistence of pharmaceutical contaminants in aquatic systems, supporting environmental risk assessment and informing future monitoring or remediation efforts.

This article can be a practical guide for researchers, such as the research conducted by Razanajatovo et al.39who investigated the uptake and excretion of selected drugs by polyethylene microplastics. They evaluated how pharmaceuticals like sulfamethoxazole (SMX), propranolol (PRP), and sertraline (SER) interact with polyethylene (PE) microplastics in water. These researchers found that the sorption percentages of these pharmaceuticals on PE microplastics decreased in the order: of SER (28.61%) > PRP (21.61%) > SMX (15.31%). The sorption kinetics were well-fitted with the pseudo-second-order model, and both the linear and the Freundlich models described the sorption isotherm. Desorption studies revealed that 8% of PRP and 4% of SER were released from the microplastics within 48 h, while the sorption of SMX was irreversible. These findings suggest that pharmaceuticals like PRP and SER may pose risks of bioaccumulation in aquatic organisms via ingestion of microplastics.

By providing molecular-level insights into these interactions, this study aims to enhance our understanding of the compounded environmental risks posed by antibiotics and aged microplastics. Molecular dynamics modeling of microplastic-antibiotic interactions is limited by simplified force fields, computational constraints on system size and simulation time, and the inability to fully replicate environmental complexity (e.g., varying ionic strength, pH, and other contaminants). Additionally, MD simulations often overlook factors such as the dynamic flexibility of polymer chains, electrostatic interactions with environmental ions, and competition between multiple pollutants. These limitations should be acknowledged, and future work should aim to incorporate these factors to provide for a more comprehensive understanding of real-world interactions.

Computational method

Microplastic and antibiotic models

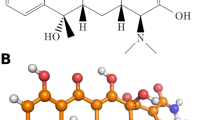

In this study, molecular dynamics simulations were conducted to investigate the adsorption behavior of antibiotics onto microplastics. Two types of microplastics, polypropylene and polystyrene, were selected, along with three antibiotics: amoxicillin, tetracycline, and ciprofloxacin. (see Fig. 1)

Polypropylene and polystyrene were selected because they rank among the most widely produced and frequently detected microplastics globally. PP constitutes roughly 19% of annual virgin plastic production and PS about 8%, together representing significant of total polymer output40. Environmental surveys consistently find PP and PS as dominant microplastic types in aquatic ecosystems. PP appears in approximately 25% of marine microplastic studies, and PS in around 16%, highlighting their pervasive presence in aquatic systems41. Their differing chemical structures also allow for comparative analysis of adsorption behavior on nonpolar PP and aromatic PS surfaces. Amoxicillin, tetracycline, and ciprofloxacin are commonly used antibiotics that are frequently detected in surface waters, due to incomplete metabolism and wastewater discharge, with 30–90% of the ingested doses being excreted unchanged42. For example, amoxicillin exhibits an excretion rate of 43–75% in humans43while ciprofloxacin is excreted approximately 50–70% unchanged in the urine, with an additional ~ 10–15% excreted as metabolites44. Their diverse molecular structures and functional groups make them representative models for studying a range of antibiotic-microplastic interactions.

Firstly, the structures of the pristine microplastic molecules were modeled using polymer chains of polypropylene and polystyrene with 50 repeating units. In this study, 50 repeating units were used to model each microplastic chain, providing a representative nanoscale segment (~ 12.5–13.5 nm) that captures essential surface and structural features. While ensuring that the polymer chains are long enough to represent the bulk properties of polypropylene and polystyrene. This chain length provides a realistic surface for adsorption interactions without significantly increasing simulation time. This enables accurate computational analysis of adsorption. (See Fig. 2.)

Aged microplastics were generated by introducing hydroxyl (-OH) and carbonyl (-C = O) functional groups to the polymer surface to mimic oxidative aging. The aging of microplastics can introduce other oxygen-containing functional groups such as carboxyl (-COOH), epoxy (-C-O-C-), and peroxide (-O-O-) groups. However, hydroxyl and carbonyl groups were selected in this study because they are among the most commonly observed and chemically stable products of oxidative degradation. They also have a significant influence on surface polarity and adsorption behavior.

The force field parameters, as well as the structural details of the antibiotics ciprofloxacin, tetracycline, amoxicillin, and polymer chains of polypropylene, and polystyrene, were sourced from the SwissParam website.

Simulation setup

For the polypropylene simulations, six simulation boxes with dimensions of 15 × 15 × 15 nm3 were utilized. Three of these boxes contained pristine PP microplastics, each simulated with 10 molecules of one of the three antibiotics. The remaining three boxes contained aged PP microplastics, each interacting with 10 molecules of amoxicillin, tetracycline, or ciprofloxacin. The details are presented in Table 1. To prevent unintended interactions, antibiotic molecules were randomly distributed around the PP microplastics at a distance of 2 nm. Similarly, six simulation boxes with dimensions of 14 × 10 × 10 nm3 were used for the polystyrene microplastic simulations. Three boxes contained pristine PS microplastics, each simulated with 10 molecules of one of the three antibiotics, while the other three contained aged PS microplastics with 10 molecules of the same antibiotics. As with the PP simulations, antibiotic molecules were randomly positioned around the PS microplastics at an approximate distance of 2 nm to avoid unwanted interactions. (see Fig. 3)

(A) The structure of Amoxicillin, Tetracycline, and Ciprofloxacin. (B) The structure of polypropylene and aged polypropylene, polystyrene, and aged polystyrene. (C) The initial snapshot of the simulation boxes for tetracycline drug, (a) polypropylene with tetracycline pollutant molecules; (b) aged polypropylene with tetracycline pollutant molecules; (c) polystyrene with tetracycline pollutant molecules; (d) aged polystyrene with tetracycline pollutant molecules.

The TIP3P water model was employed to represent the biological environment. To maintain charge neutrality and simulate natural conditions, sodium and chloride ions were added to the system.

Energy minimization was conducted using the steepest descent algorithm, followed by equilibration in the NVT and NPT ensembles at 300 K and 1 bar for 200 ps. Electrostatic interactions were computed using the particle-mesh Ewald (PME) method, with a cutoff radius of 1.4 nm for short-range interactions. The system temperature was maintained at 300 K using a Nosé–Hoover thermostat to mimic environmental conditions, while pressure regulation at 1 bar was achieved using the Parrinello–Rahman barostat.

To preserve bond constraints, the LINCS algorithm was applied. Production simulations were carried out for 105 ns with a 2 fs time step using GROMACS 2022.1. Molecular visualization and analysis were performed using VMD software, facilitating the inspection of molecular interactions and aiding in the interpretation of simulation results.

Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD), Radial Distribution Functions (RDF), Mean Squared Displacement (MSD), and the number of hydrogen bonds (HB) were analyzed to evaluate the simulation results.

RMSD is a measure of the deviation between the current position of atoms in a system and a reference structure over time. RDF of the pollutant/adsorbent system was examined to assess the interactions between antibiotic molecules and microplastics. This function ( \(\:{g}_{ij}\left(r\right)\) ) serves as a crucial measure of the likelihood of pollutants being positioned at specific distances from the microplastic surface, as determined by Eq. (1)45:

\(\:{\rho\:}_{j}\left(r\right)\) represents the average density of molecule j at a distance r from molecule i. Additionally, \(\:{\rho\:}_{j}\:\)corresponds to the density of molecule j, averaged over all spherical shells surrounding molecule i up to rmax.

To determine the diffusivity of antibiotic molecules adsorbed onto microplastics in various systems, MSD is initially estimated using the following Eq. (2)46,47.

Here, \(\:{({r}_{i}\left(\varDelta\:t\right)-{r}_{i}\left(0\right))}^{2}\:\)is the distance traveled by center of mass of the particle i over some time interval of length.

Throughout the simulation, the particle diffusion coefficient (Di) can be determined using Einstein’s equation, as presented in Eq. (3).

Based on geometric criteria, HB analysis evaluates the potential number of HBs formed between donor and acceptor molecules48.

Result and discussion

Adsorption behavior and structural insights

To evaluate the adsorption of antibiotics onto microplastics, the initial and final simulation snapshots were analyzed. The final simulation snapshots are shown in Figs. 4 and 5. In the initial configurations, antibiotic molecules were randomly distributed around the microplastic surfaces at a distance of 2 nm, ensuring no pre-adsorption interactions. Over the course of the simulation, significant changes in molecular positioning and interactions were observed, providing insight into the adsorption process.

Final snapshots revealed that a varying number of antibiotic molecules had successfully adsorbed onto the microplastic surfaces, with differences observed between pristine and aged microplastics. In particular, aged microplastics showed higher adsorption due to surface roughness, altered hydrophobicity, and functional group interactions. The number of adsorbed molecules for each antibiotic type is summarized in Table S1.

These findings highlight the impact of microplastic aging on antibiotic adsorption and provide atomic-level insights into pollutant accumulation in environmental systems.

The increased antibiotic uptake on aged microplastics compared to pristine microplastics is consistent with the findings of Stapleton et al. In their experimental research, Stapleton et al. concluded that the weathering of microplastics increases their antibiotic uptake capacity by 171%49.

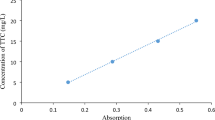

Interaction energies

The interaction energy of the van der Waals (vdW) forces between antibiotic molecules and microplastic versus time of simulation is evaluated using the “gmx energy” module of the GROMACS software software and presented in Fig. 6.

VdW interactions between the microplastics with drug pollutant molecules as a function of time. (a) The polypropylene with drug pollutant molecules; (b) the aged polypropylene with drug pollutant molecules; (c) the polystyrene with drug pollutant molecules; (d) the aged polystyrene with drug pollutant molecules.

Furthermore, the average vdW interaction energy and electrostatic interaction energy of the simulated systems are shown in Fig. 7 and Table S1. To enhance clarity in analyzing the adsorption energies, these energies are presented in a heatmap diagram shown in Fig. 7.

As expected, the aging of microplastics significantly enhances adsorption for all three antibiotics. This is evident from the total interaction energies, which are consistently more negative for aged microplastics compared to their pristine counterparts. This enhancement is likely due to:

-

• Increased surface roughness from oxidative and hydrolytic degradation, creating more binding sites.

-

• Introduction of polar functional groups on the microplastic surface, leading to stronger electrostatic interactions with antibiotic molecules.

To simulate the effects of oxidative and hydrolytic degradation on the surface properties of microplastics, structural and chemical modifications, which represent increased surface roughness and bonding site availability, commonly observed in aged plastics, were modeled by introducing randomly distributed functional groups (e.g., -OH, -COOH, and C = O) on the polymer surface.

The total adsorption energy of amoxicillin on polypropylene decreases from − 52.14 kJ/mol (pristine) to -93.43 kJ/mol (aged), with the number of adsorbed molecules increasing from 4 to 6.

The total interaction energy of ciprofloxacin on polystyrene drops dramatically from − 121.57 kJ/mol (pristine) to -242.04 kJ/mol (aged), and the number of adsorbed molecules doubles from 5 to 10.

Van der Waals interactions dominate across all systems, especially for polystyrene, where total energies are significantly influenced by vdW forces.

Electrostatic interactions play a secondary role, except in aged microplastics, where they become more pronounced due to surface oxidation.

In pristine polystyrene, ciprofloxacin has an electrostatic energy of + 4.08 kJ/mol, indicating weak electrostatic repulsion. However, in aged polystyrene, this energy shifts to -28.41 kJ/mol, signifying stronger electrostatic binding.

Amoxicillin adsorption is highest on aged PS (-147.18 kJ/mol, 8 molecules), suggesting a strong affinity due to hydrogen bonding and π-π interactions. Tetracycline adsorption is more significant on polystyrene than polypropylene, possibly due to its aromatic structure engaging in π-π interactions with PS. Ciprofloxacin is the most strongly adsorbed antibiotic, especially on aged PS (-242.04 kJ/mol, 10 molecules). This could be due to ciprofloxacin’s amphiphilic nature, enabling it to interact both via hydrophobic forces and electrostatic attraction. Polystyrene shows stronger adsorption than polypropylene, particularly for aged microplastics. This is due to greater hydrophobicity and π-π interactions with aromatic antibiotics. Polypropylene, while less adsorptive overall, still binds antibiotics efficiently upon aging, likely due to increased polarity and surface roughness.

Aging-induced oxidative and hydrolytic processes introduce oxygen-bearing functional groups (–OH, –COOH) on microplastic surfaces, increasing local polarity and surface electronegativity. These chemical modifications elevate hydrogen-bonding capacity and dipole–dipole interaction potential, even if the net surface charge becomes more negative. Specifically, amphiphilic antibiotics such as ciprofloxacin and amoxicillin possess both cationic (–NH3+) and anionic (–COO−) moieties. As a result, the aged microplastic surfaces facilitate strong electrostatic attraction and hydrogen bonding with these antibiotics, which outweighs any simple charge-based repulsion. Consequently, after aging, the observed electrostatic interaction energies become more negative, reflecting enhanced binding strength from these newly formed polar–polar interactions.

Aging significantly enhances the adsorption capacity of microplastics, making them more potent carriers of antibiotic contaminants. Polystyrene microplastics pose a greater environmental risk due to their stronger adsorption tendencies, potentially leading to the prolonged persistence of antibiotics in aquatic environments. Antibiotic-specific interactions highlight the importance of molecular structure in determining adsorption behavior, with ciprofloxacin showing the strongest binding.

These findings suggest that microplastic pollution may act as an effective vector for antibiotic transport, possibly influencing microbial resistance patterns in aquatic ecosystems. Further experimental validation and studies on desorption kinetics would be valuable to understand the long-term fate of these contaminants.

Root mean square deviation (RMSD)

The RMSD analysis plots for the investigated systems are displayed in Fig. 8. These plots demonstrate the structural stability of the molecular systems throughout the adsorption process. After the initial adsorption, in 20 ns, RMSD stabilization was observed. This suggests that the adsorption has reached equilibrium. The antibiotics have settled onto the microplastic surface with less movement because they have become more adsorbed and stable. This stability suggests that these antibiotics could persist longer in the environment, especially in aquatic systems where microplastics are prevalent. Persistent antibiotics can lead to prolonged exposure for aquatic organisms and contribute to the accumulation of these contaminants in food webs50,51.

In summary, RMSD trends provide critical insights into how antibiotics interact with microplastics, influencing their environmental persistence, mobility, and potential to contribute to antibiotic resistance. These findings highlight the importance of addressing pharmaceutical pollution in environmental management strategies to protect ecosystems and public health.

Radial distribution functions (RDF)

According to our obtained results in Fig. 9, the RDF peaks indicate the preferred interaction distances between the antibiotics and the microplastic surfaces. A sharp, high peak at small r (~ 4–6 Å) suggests strong molecular attraction, such as hydrogen bonding or electrostatic interactions. Broader or lower peaks indicate weaker adsorption or more dispersed interactions. The RDF plots of all studied systems exhibit peaks between 4 and 6 Å, with varying intensities that indicate different interactions between pollutant molecules and microplastics.

Polystyrene generally exhibits higher RDF peaks for ciprofloxacin and tetracycline compared to amoxicillin. This suggests that π-π interactions play a major role in adsorption for these two drugs, as PS has aromatic rings that can engage in π-π stacking with aromatic rings in ciprofloxacin and tetracycline. Amoxicillin, which has weaker aromaticity, shows a less pronounced preference for PS but may still interact through hydrogen bonding.

Polypropylene is a non-polar material with mainly hydrophobic interactions. The RDF peaks for PP suggest that adsorption is weaker compared to PS, especially for tetracycline and ciprofloxacin. The adsorption of amoxicillin on PP is still significant due to its amphiphilic nature, enabling some hydrophobic affinity.

These insights indicate that microplastic composition significantly affects the environmental fate of antibiotic contaminants, with PS showing a higher tendency to adsorb pharmaceutical pollutants via π-π and hydrogen bonding interactions.

The mean squared displacement (MSD)

The Mean Squared Displacement is a key metric used in molecular dynamics simulations to quantify the mobility of molecules over time. A higher MSD suggests greater molecular diffusion (lower adsorption), while a lower MSD indicates restricted movement, implying stronger adsorption onto the microplastic surface. It is evident from Fig. 10 that: Ciprofloxacin exhibits lower MSD on both aged microplastics than on pristine microplastics, particularly on aged polystyrene.

This suggests stronger adsorption due to π-π interactions between the aromatic rings in ciprofloxacin and the benzene rings in aged microplastics. Likewise, amoxicillin shows relatively higher MSD than ciprofloxacin, implying weaker adsorption and tetracycline’s MSD falls between amoxicillin and ciprofloxacin, suggesting moderate adsorption strength.

Therefore ciprofloxacin is more likely to accumulate on aged microplastics, leading to long-term environmental persistence.

Amoxicillin and tetracycline exhibit greater mobility, suggesting they may desorb more easily and remain bioavailable in aquatic systems.

Understanding these interactions helps in predicting antibiotic transport in marine environments, influencing risk assessments for microplastic pollution.

The MSD plots and the diffusion coefficients presented in Table 2 indicate that antibiotics tend to exhibit lower MSD on polystyrene than on polypropylene. This indicates that polystyrene has a stronger affinity for antibiotic molecules, likely due to π-π stacking with aromatic drug structures. Polypropylene lacks aromatic rings, leading to weaker interactions and allowing greater antibiotic mobility.

The number of hydrogen bonds (HB)

In molecular dynamics simulations, hydrogen bond analysis is a crucial tool for examining the dynamics of these interactions over time, offering valuable insights into the structural stability of molecular systems. In this study, the hydrogen bonds formed between antibiotic molecules and microplastics were analyzed, with the results presented in Fig. 11. The findings indicate that pristine microplastics do not form hydrogen bonds with antibiotic molecules. However, aged microplastics, which possess polar functional groups such as hydroxyl and carboxyl groups on their surface (as seen in polystyrene and polypropylene), can establish hydrogen bonds with antibiotic molecules.

Amoxicillin is a polar molecule containing multiple hydroxyl and amino groups, allowing it to form hydrogen bonds with aged microplastics. The analysis reveals that amoxicillin exhibits a higher number of hydrogen bonds compared to the other antibiotics, suggesting stronger electrostatic interactions, which align with the electrostatic energy results presented in the energy analysis section. In contrast, tetracycline forms fewer hydrogen bonds than amoxicillin and ciprofloxacin, indicating weaker electrostatic interactions with aged microplastic surfaces. As a fluoroquinolone, ciprofloxacin possesses a distinct set of functional groups compared to amoxicillin and tetracycline, which may influence its interaction with microplastics.

The number of hydrogen bonds formed by each antibiotic varies between polypropylene and polystyrene due to differences in their surface propertie. These findings further support the notion that structural variations among antibiotics significantly influence their adsorption and diffusion behavior on microplastic surfaces.

The findings of this study offer important insights into the environmental behavior and fate of antibiotic pollutants in the presence of microplastics. Our molecular dynamics simulations reveal that aged polypropylene and polystyrene microplastics exhibit significantly enhanced adsorption capacities for widely used antibiotics such as ciprofloxacin, amoxicillin, and tetracycline. This enhancement is primarily due to aging-induced surface modifications—specifically, the introduction of polar oxygen-containing functional groups (e.g., hydroxyl, carbonyl)—as well as increased surface roughness. These changes lead to stronger van der Waals interactions, more favorable electrostatic attractions, and the formation of hydrogen bonds between the antibiotic molecules and the microplastic surfaces.

From an environmental standpoint, these results are particularly relevant. The increased adsorption of antibiotics onto aged microplastics suggests that these particles can serve as persistent carriers or reservoirs for pharmaceutical contaminants in aquatic environments. Unlike free-floating antibiotic molecules, which may degrade or be diluted over time, antibiotic-laden microplastics can remain in the water column or settle in sediments, potentially protecting the adsorbed compounds from immediate degradation. This prolonged environmental residence time increases the likelihood of chronic exposure for aquatic organisms—even at sub-inhibitory concentrations—which could disrupt microbial community dynamics, interfere with biological processes, and contribute to the selection and proliferation of antibiotic-resistant bacteria and resistance genes.

Moreover, microplastics can be ingested by a wide range of aquatic organisms, from plankton to fish, providing a direct pathway for antibiotic-contaminated particles to enter and move up the food web. This bioaccumulation potential raises further concerns about indirect human exposure through seafood consumption and the broader ecological consequences of microplastic-associated pollutants.

These findings highlight the dual role of microplastics in aquatic environments: not only as persistent physical pollutants but also as chemical vectors that may exacerbate the environmental and public health risks associated with pharmaceutical contamination. Given the scale of global plastic production and the increasing prevalence of microplastics in natural ecosystems, the potential for microplastic-mediated transport and persistence of antibiotics represents a critical issue for environmental risk assessment. We therefore emphasize the need for interdisciplinary efforts to further investigate the combined impact of microplastics and pharmaceutical contaminants. Understanding their synergistic behavior is essential for developing informed strategies aimed at pollution control, regulatory oversight, and long-term ecological protection.

Conclusion

This study provides molecular-level insights into the adsorption mechanisms of three widely used antibiotics, ciprofloxacin, amoxicillin, and tetracycline, on pristine and aged microplastics, specifically polypropylene and polystyrene. Findings indicate that aging significantly enhances antibiotic adsorption, with total interaction energy values nearly doubling in some cases. For instance, the adsorption energy of ciprofloxacin on aged polystyrene increased from − 121.57 kJ/mol to -242.04 kJ/mol, while the number of adsorbed molecules rose from 5 to 10. Similarly, aged polypropylene demonstrated increased amoxicillin adsorption, from 4 to 6 molecules, with interaction energy increasing from − 52.14 kJ/mol to -93.43 kJ/mol. The presence of oxidized functional groups on aged MPs enhances electrostatic interactions, hydrogen bonding, and π-π stacking, making them more effective carriers of antibiotics in aquatic environments. Given that global plastic production exceeded 400 million metric tons in 2022 and plastic degradation continuously generates secondary MPs, their role in antibiotic transport and persistence in ecosystems cannot be overlooked. These results emphasize the urgent need for improved waste management strategies, further experimental validation, and regulatory policies to mitigate the environmental and public health risks associated with microplastic pollution and antibiotic resistance.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Ivleva, N. P., Wiesheu, A. C. & Niessner, R. Microplastic in aquatic ecosystems. Angew Chemie Int. Ed. 56, 1720–1739 (2017).

Jo, S. Y. et al. A shortcut to carbon-neutral bioplastic production: recent advances in microbial production of polyhydroxyalkanoates from C1 resources. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 192, 978–998 (2021).

Fan, J. et al. Occurrence and distribution of microplastics in surface water and sediments in china’s inland water systems: a critical review. J. Clean. Prod. 331, 129968 (2022).

Pang, W. et al. Optimization of degradation behavior and conditions for the protease K of polylactic acid films by simulation. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 253, 127496 (2023).

Zhang, X. et al. Aging properties of polyethylene and polylactic acid microplastics and their adsorption behavior of cd (II) and cr (VI) in aquatic environments. Chemosphere 363, 142833 (2024).

Sharma, M. D., Elanjickal, A. I., Mankar, J. S. & Krupadam, R. J. Assessment of cancer risk of microplastics enriched with polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons. J. Hazard. Mater. 398, 122994 (2020).

Eriksen, M. K., Damgaard, A., Boldrin, A. & Astrup, T. F. Quality assessment and circularity potential of recovery systems for household plastic waste. J. Ind. Ecol. 23, 156–168 (2019).

Yuan, S., Zhang, H. & Yuan, S. Understanding the transformations of nanoplastic onto phospholipid bilayers: mechanism, microscopic interaction and cytotoxicity assessment. Sci. Total Environ. 859, 160388 (2023).

Tekman, M. B. et al. Tying up loose ends of microplastic pollution in the arctic: distribution from the sea surface through the water column to deep-sea sediments at the HAUSGARTEN observatory. Environ. Sci. \& Technol. 54, 4079–4090 (2020).

Rahman, M. M., Sultan, M. B. & Alam, M. Microplastics and adsorbed micropollutants as emerging contaminants in landfill: A mini review. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sci. \& Heal. 31, 100420 (2023).

Huang, W. et al. Insights into adsorption behavior and mechanism of Cu (II) onto biodegradable and conventional microplastics: effect of aging process and environmental factors. Environ. Pollut. 342, 123061 (2024).

Arienzo, M., Ferrara, L. & Trifuoggi, M. The dual role of microplastics in marine environment: sink and vectors of pollutants. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 9, 642 (2021).

Mart\’\in, J., Santos, J. L., Aparicio, I. & Alonso, E. Microplastics and associated emerging contaminants in the environment: analysis, sorption mechanisms and effects of co-exposure. Trends Environ. Anal. Chem. 35, e00170 (2022).

Hossain, M. M., Banerjee, A., Chatterjee, M., Roy, K. & Cronin, M. T. D. QSPR and q-RASPR predictions of the adsorption capacity of polyethylene, polypropylene and polystyrene microplastics for various organic pollutants in diverse aqueous environments. Environ. Sci. Nano. 11, 4196–4210 (2024).

González-Pleiter, M. et al. Toxicity of five antibiotics and their mixtures towards photosynthetic aquatic organisms: implications for environmental risk assessment. Water Res. 47, 2050–2064 (2013).

Binh, V. N., Dang, N., Anh, N. T. K. & Thai, P. K. others. Antibiotics in the aquatic environment of vietnam: sources, concentrations, risk and control strategy. Chemosphere 197, 438–450 (2018).

Yi, X., Lin, C., Ong, E. J. L., Wang, M. & Zhou, Z. Occurrence and distribution of trace levels of antibiotics in surface waters and soils driven by non-point source pollution and anthropogenic pressure. Chemosphere 216, 213–223 (2019).

Kovalakova, P. et al. Occurrence and toxicity of antibiotics in the aquatic environment: A review. Chemosphere 251, 126351 (2020).

Venu, V., Nishil, B., Kashyap, A., Sonkar, V. & Thatikonda, S. Phytotoxic effects of Tetracycline and its removal using Canna indica in a hydroponic system. Bull. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 111, 4 (2023).

Sonkar, V., Venu, V., Nishil, B. & Thatikonda, S. Review on antibiotic pollution dynamics: insights to occurrence, environmental behaviour, ecotoxicity, and management strategies. Environ. Sci. Pollut Res. 31, 51164–51196 (2024).

Yu, F., Yang, C., Zhu, Z., Bai, X. & Ma, J. Adsorption behavior of organic pollutants and metals on micro/nanoplastics in the aquatic environment. Sci. Total Environ. 694, 133643 (2019).

Wang, Z. et al. Research progresses of microplastic pollution in freshwater systems. Sci. Total Environ. 795, 148888 (2021).

Li, C., Busquets, R. & Campos, L. C. Assessment of microplastics in freshwater systems: A review. Sci. Total Environ. 707, 135578 (2020).

Chen, Q. et al. Quantitative investigation of the mechanisms of microplastics and nanoplastics toward zebrafish larvae locomotor activity. Sci. Total Environ. 584, 1022–1031 (2017).

Lu, J., Zhang, Y. & Wu, J. Continental-scale spatio-temporal distribution of antibiotic resistance genes in coastal waters along coastline of China. Chemosphere 247, 125908 (2020).

Wang, L., Yang, H., Guo, M., Wang, Z. & Zheng, X. Adsorption of antibiotics on different microplastics (MPs): behavior and mechanism. Sci. Total Environ. 863, 161022 (2023).

Zha, F., Shang, M., Ouyang, Z. & Guo, X. The aging behaviors and release of microplastics: A review. Gondwana Res. 108, 60–71 (2022).

Liu, P. et al. Review of the artificially-accelerated aging technology and ecological risk of microplastics. Sci. Total Environ. 768, 144969 (2021).

Cole, M. & Galloway, T. S. Ingestion of nanoplastics and microplastics by Pacific oyster larvae. Environ. Sci. \& Technol. 49, 14625–14632 (2015).

Fueser, H., Mueller, M. T., Weiss, L., Höss, S. & Traunspurger, W. Ingestion of microplastics by nematodes depends on feeding strategy and buccal cavity size. Environ. Pollut. 255, 113227 (2019).

Jin, Y. et al. Polystyrene microplastics induce microbiota dysbiosis and inflammation in the gut of adult zebrafish. Environ. Pollut. 235, 322–329 (2018).

Liu, P. et al. Effect of weathering on environmental behavior of microplastics: properties, sorption and potential risks. Chemosphere 242, 125193 (2020).

Sun, Y. et al. Laboratory simulation of microplastics weathering and its adsorption behaviors in an aqueous environment: a systematic review. Environ. Pollut. 265, 114864 (2020).

Botterell, Z. L. R. et al. Bioavailability and effects of microplastics on marine zooplankton: A review. Environ. Pollut. 245, 98–110 (2019).

Gao, Y. et al. A comprehensive review of microplastic aging: laboratory simulations, physicochemical properties, adsorption mechanisms, and environmental impacts. Sci. Total Environ. 957, 177427 (2024).

Liu, S. et al. Reactive oxygen species-induced microplastics aging: implications for environmental fate and ecological impact. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 173, 117648 (2024).

Chelomin, V. P. et al. New insights into the mechanisms of toxicity of aging microplastics. Toxics 12, 726 (2024).

Townsend, P. A. Adsorption in action: molecular dynamics as a tool to study adsorption at the surface of fine plastic particles in aquatic environments. ACS Omega. 9, 5142–5156 (2024).

Razanajatovo, R. M., Ding, J., Zhang, S., Jiang, H. & Zou, H. Sorption and desorption of selected pharmaceuticals by polyethylene microplastics. Mar. Pollut Bull. 136, 516–523 (2018).

Espinosa, C., Esteban, M. Á. & Cuesta, A. Microplastics in aquatic environments and their toxicological implications for fish. Toxicol Asp this Sci. Conundrum 113 (2016).

Mutuku, J., Yanotti, M. & Tocock, M. & Hatton MacDonald, D. The abundance of microplastics in the world’s oceans: a systematic review. in Oceans 5, 398–428 (2024).

Zhou, X., Cuasquer, G. J. P., Li, Z., Mang, H. P. & Lv, Y. Occurrence of typical antibiotics, representative antibiotic-resistant bacteria, and genes in fresh and stored source-separated human urine. Environ. Int. 146, 106280 (2021).

Aranda, F. L. & Rivas, B. L. Removal of amoxicillin through different methods, emphasizing removal by biopolymers and its derivatives. An overview. J. Chil. Chem. Soc. 67, 5643–5655 (2022).

Höffken, G., Lode, H., Prinzing, C., Borner, K. & Koeppe, P. Pharmacokinetics of Ciprofloxacin after oral and parenteral administration. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 27, 375–379 (1985).

Gao, B. H., Qi, H., Jiang, D. H., Ren, Y. T. & He, M. J. Efficient equation-solving integral equation method based on the radiation distribution factor for calculating radiative transfer in 3D anisotropic scattering medium. J. Quant. Spectrosc. Radiat. Transf. 275, 107886 (2021).

Pei, J. et al. Molecular dynamic simulations and experimental study on pBAMO-b-GAP copolymer/energetic plasticizer mixed systems. FirePhysChem 2, 67–71 (2022).

Hunter, M. A., Demir, B., Petersen, C. F. & Searles, D. J. New framework for computing a general local self-diffusion coefficient using statistical mechanics. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 18, 3357–3363 (2022).

Najafi rad, Z., Farzad, F. & Razavi, L. Surface functionalization of graphene nanosheet with Poly (l-histidine) and its application in drug delivery: covalent vs non-covalent approaches. Sci. Rep. 12, 19046 (2022).

Stapleton, M. J., Ansari, A. J. & Hai, F. I. Antibiotic sorption onto microplastics in water: A critical review of the factors, mechanisms and implications. Water Res. 233, 119790 (2023).

Polianciuc, S. I., Gurz\uau, A. E., Kiss, B., \cStefan, M. G. & Loghin, F. Antibiotics in the environment: causes and consequences. Med. Pharm. Rep. 93, 231 (2020).

Fernandes, J. P., Almeida, C. M. R., Salgado, M. A., Carvalho, M. F. & Mucha, A. P. Pharmaceutical compounds in aquatic environments—occurrence, fate and bioremediation prospective. Toxics 9, 257 (2021).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A. Sedigheh Abdollahi: Devised the computational protocol and prepared the model systems, performed all calculations, analyzed the data, and wrote and edited the original and the revised manuscript.B. Heidar Raissi: Supervision. Reviewing- Editing, edited the original and the revised version of the manuscript. C. Farzaneh Farzad: Reviewing-Editing, edited the original and the revised version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Abdollahi, S., Raissi, H. & Farzad, F. The role of microplastics as vectors of antibiotic contaminants via a molecular simulation approach. Sci Rep 15, 27007 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-12799-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-12799-6