Abstract

High air pollution and sound in Dhaka pose major health risks, yet limited high-resolution data hinders epidemiologic assessments and interventions. We measured fine particulate matter (PM₂.₅), black carbon (BC), and sound (dBA) at 70 locations across Dhaka during the 2023 dry (Jan–Mar) and wet (Jul–Sep) seasons, with continuous monitoring at 8 fixed sites and short-term sampling at 62 rotating sites (3 days/season). Over 1.7 million minutes of PM2.5 and 1.2 million minutes of sound were collected, enabling detailed spatial (land use features) and temporal (seasonal, weekly, daily, and diurnal) analyses. Air pollution was four times higher in the dry season, with commercial/industrial areas and transportation corridors having the highest levels, particularly at night. Sound levels varied less temporally, and were highest in transportation corridors, mixed-use areas, and commercial hubs. Air pollution and sound across the city exceeded international guidelines. These findings provide critical evidence to inform targeted policy and interventions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cities drive economic growth and innovation, but the influx of people, traffic, and industry can place enormous pressure on local environments1,2. Dhaka, Bangladesh (pop. 24.7 million)3, is one of the world’s most densely populated and fastest-growing megacity, with some of the highest recorded levels of air pollution and noise4. Ambient fine particulate matter (PM2.5) in Dhaka is 12–18 times higher than the World Health Organization’s (WHO) guideline (5 µg/m3)5, with annual averages ranging from 63.6 to 91.9 µg/m3 between 2010 and 20196. The few studies of environmental noise report levels from 57 to 110 dBA7,8,9, often exceeding the highest permissible area-based noise guidelines for Bangladesh (75 dBA in daytime and 70 dBA in nighttime in industrial areas)10 and the WHO European Region (54 dBA for railway noise)11.

Health consequences of air pollution and noise are well-established. Exposure to air pollution increases risk of early mortality12 and the development of cardio-respiratory diseases13, several types of cancer14, and neurological disorders15. Epidemiologic studies in North America and Europe associated transportation noise with sleep disturbance, annoyance, impaired neuro-cognitive functioning, and cardiovascular diseases16. Dhaka’s high levels of air pollution and noise likely pose large population health risks. However, limited high-resolution data prevent epidemiologic studies and health risk assessments, and poses a barrier for identifying and monitoring local emissions hotspots and for designing and evaluating mitigation strategies17. All of which were effectively used to inform air quality mitigation strategies in North America, Europe, and other parts of Asia. Thus, there is a significant unmet need to undertake rigorous scientific research on community air quality and noise to support public health policy and regulatory decisions.

We conducted a comprehensive field campaign, measuring seasonal air pollution and sound across 70 diverse locations that captured the city’s diversity of land use and environmental conditions. To our knowledge, this represents the most spatially-resolved empirical study of air pollution and sounds levels in Dhaka to date. Our findings aim to inform ongoing and future environmental assessments, city planning initiatives, and policy solutions tailored to Dhaka’s specific context and pollution sources.

Study setting

Dhaka is the political capital and economic hub of Bangladesh and is experiencing rapid, often unplanned, growth to absorb its estimated 1500 to 2000 daily migrants18. The Dhaka metropolitan area covers ~ 306 km2 and is among the world’s most densely populated urban areas, with an estimated population density of 27,599 persons/km2 in 201519 and an anticipated population increase to 35 million by 205018. The city’s tropical monsoon climate is characterized by seasonal increases in rainfall that impact air pollution levels and sources. The months of November to March are generally referred to as the “dry season”, as rainfall is at its lowest, where air quality is impacted by brick kiln operations and regional air pollution in addition to local sources like traffic, construction, and industry that also contribute to environmental sound. The months of May to September are considered the “wet season”, where regional and brick kiln pollution decrease but local sources persist4,20.

Results

We captured 1,720,945 min of real-time PM2.5 data during 1,193 24-h measurement days across 297 sensor deployments (fixed = 173; rotating = 124) over 124 unique sampling days. Thirty-four sensor deployments (11%) did not achieve within 10 h of target duration (fixed = 33; rotating = 1), mostly due to battery failure or, in one instance, monitor theft. These issues resulted in 76 missed 24-h measurement-days. Gravimetric (filter-based) PM2.5 and black carbon (BC) measurements were obtained for 1,170 24-h measurement-days (97% completion), with 62 missing due to battery failure, filter overloading, or monitor theft. There were no instances of simultaneous sensor and gravimetric monitors failure.

We also recorded 1,192,527 min of sound data during 814 24-h measurement-days over 121 unique sampling days. Of the 193 attempted deployments, 179 (93%) achieved within 10 h of the sampling targets. Missing data (n = 46 24-h measurement days) resulted from battery or sensor failure. Two rotating site deployments failed completely and were excluded from the analysis.

Temporal patterns exposure

Average PM2.5 and BC concentrations were approximately four times higher in the dry season than the wet season (PM2.5: 195 versus 54 µg/m3; BC: 13.5 versus 2.9 µg/m3), though BC/PM2.5 ratios were relatively consistent (7.0% and 5.8% in dry and wet seasons, respectively) (Table 1). All sites exceeded the WHO health-motivated 24-h PM2.5 guideline of 15 µg/m5. PM2.5 levels varied modestly by day of the week. In both seasons, concentrations were generally lower on Thursday (last day of the work week in Bangladesh) and higher on Sundays and Monday (beginning of the work week) (Supplementary Fig. 1; Supplementary Table 2).

The median sound level (LAeq) across sites was 63.0 dBA (IQR: 10.3; range: 50.5, 84.0), exceeding Dhaka’s residential noise guideline (55 dBA) but below its industrial zone guideline (75 dBA) for daytime (Table 2; Supplementary Table 4)10. Only 1.9% of daytime and 2.7% of nighttime measurement minutes were below the WHO European guidelines for traffic noise (53 dBA daytime; 45 dBA nighttime)11. Based on fixed site data, sound levels were similar across seasons and there was less than 1 dBA variation in average sound across days of the week (Supplementary Fig. 2; Supplementary Table 5).

Diurnal patterns for air pollution and sound were distinct and generally consistent across land use categories (Fig. 1). Average PM2.5 levels were higher at night than during the day in the dry season (216 versus 180 µg/m3), while in the wet season, day and nighttime levels were similar (56 versus 52 µg/m3). However, at commercial and industrial sites, nighttime PM2.5 remained elevated in the wet season (Table 1), largely driven by the very high nighttime PM2.5 levels at the industrial (fixed) site of Shyampur (wet season nighttime mean of 491 µg/m3 versus daytime mean of 389 µg/m3). Sound followed an inverse pattern, with higher median levels during the day (65 dBA; IQR: 10.6) than at night (60 dBA; IQR: 12.0) (Table 2). We observed distinct peaks in sound levels that corresponded with calls to prayer (Supplementary Fig. 3).

The intermittency ratio (IR), a measure of the disruptiveness of sound events compared with background levels, showed little difference on average between day and night (medians of 47.9 verses 48.4% for day and nighttime respectively) (Table 2). However, site-specific variation was substantial: at 13 sites, daytime IR exceeding nighttime IR by > 5% (range: 5.5 to 34.6%), while at 36 sites, nighttime IR was > 5% higher (range: 6.6 to 38.5%). These findings suggest that the diurnal IR patterns depend on site-specific characteristics. Generally, transportation and residential sites had higher nighttime IRs, while green, blue, and open (GBO) spaces had higher daytime IRs. These patterns were consistent across different IR threshold in sensitivity analyses (Supplementary Table 6; Supplementary Note 7).

Diurnal patterns of (A) average air pollution by season and (B) sound in Dhaka. Air pollution data show the temporally-adjusted hourly mean PM2.5 (µg/m3) by season and land use category. Sound data show the median LAeq for each hour of the day by land use category. Fifteen-minute rolling average values are provided in Supplementary Fig. 3.

Spatial patterns

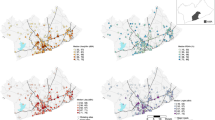

Sound levels were highest in the urban core, whereas PM2.5 concentrations peaked in peripheral industrial zones, especially in southern Dhaka (Fig. 2). Estimated annual PM2.5 ranged from 81 to 453 µg/m3 and BC from 2.9 to 14.5 µg/m3. The Shyampur fixed site, located in an informal settlement near an industrial area, recorded the highest PM2.5 (range of daily means: 73 to 1128 µg/m3). BC levels were also high in Shyampur (dry/wet season averages of 21.5/7.6 µg/m3), though less extreme than PM2.5.

Air pollution and sound were higher in transportation, commercial, and industrial zones, and lower in residential and GBO sites (Table 1; Fig. 3). We observed more notable differences in PM2.5 by land use type in the wet season (p-value = 0.007) than dry season (p-value = 0.29). Median LAeq ranged from 51 to 84 dBA across sites (median: 63) (Table 2; Supplementary Table 3). Mixed-use sites had the highest median LAeq (73 dBA), followed by transportation corridors (70 dBA), commercial and industrial sites (65 dBA), residential areas (61 dBA), and GBOs (55 dBA) (p-value ≤ 0.001) (Table 2). According to Bangladesh’s land use-specific Noise Pollution Control Rules, 84% of residential sites exceeded daytime limits, and all residential sites exceeded nighttime limits. In commercial/industrial areas, 7% exceeded daytime and 27% exceeded nighttime limits, while all mixed-use sites exceeded both day and nighttime limits by 1–59% (Supplementary Table 4)10.

IR values also varied by land use (p-value = 0.002). Residential and GBO sites, which had the lowest average sound levels, exhibited the highest IRs (medians: 61.3% and 68.2%, respectively) compared with other land use categories (range of medians: 35.3–49.2%) (Table 2). The IR values were lower at fixed sites than at rotating sites, despite similar average sound levels. This discrepancy may reflect the underrepresentation of fixed monitors in higher IR land use types, such as residential (n = 1) and GBO zones (n = 2).

Spatial variation in average air pollution (A), sound (B), and their combination (C) in Dhaka. The mean PM2.5 concentrations are the mean average of temporally-adjusted site means from both seasons. The LAeq (B) represents the site median. The bivariate map (C) assigns each site into one of nine combined pollution categories based on PM2.5 and sound tertiles. Identified hotspots for PM2.5 and sound are also labelled. Tertiles were calculated from quantiles with breaks at 33.33% and 66.66%.

Site-averaged PM2.5 and sound levels were weak-to-moderately correlated (Spearman rdry=0.35; rwet=0.54) (Supplementary Fig. 4). Identified co-hotspots included the Shyampur informal settlement (PM2.5: 453 µg/m3; sound: 65 dBA), the mixed-use sites at Kuril (PM2.5: 103 µg/m3; sound: 81 dBA) and Nilkhet (PM2.5: 131 µg/m3; sound: 74 dBA), and a transportation corridor in Rajlokkhi (PM2.5: 124 µg/m3; sound: 84 dBA) (Fig. 2).

Discussion

Dhaka, a rapidly growing megacity of over 24 million people, experiences high levels of air pollution and noise that pose serious public health risks. Yet, there is limited city-wide evidence on the levels, patterns, and sources to support effective management strategies7,21. At most monitoring sites in this city-wide study, both air pollution and nighttime sound levels exceeded national and international guidelines. Air pollution was markedly higher during the nighttime, in the dry season, and in commercial and industrial areas. In contrast, sound levels exhibited less temporal variability but were highest in commercial markets and transportation corridors. We did not observe a strong overall correlation between sound and air pollution, highlighting the need for tailored mitigation strategies, though traffic may offer a shared point of intervention.

Air pollution peaked during the dry season, consistent with prior studies in Dhaka, and largely attributed to transboundary pollution from Nepal and India, unfavorable meteorological conditions (lower wind speeds, reduced mixing layer height, and minimal rainfall), and local sources such as brick kilns and biomass burning4,20,22,23,24. In contrast, sound remained consistently high year-round, with sources being exclusively local, including traffic, construction, commercial activities, and daily calls to prayer.

We observed minimal variation in air pollution or sound across different days of the week. This aligns with a prior study in Dhaka suggesting that weekend delivery truck traffic offsets reductions in commuter traffic20. Such patterns resemble those observed in other rapidly urbanizing cities like Accra25,26, but differ from cities in North American and European, where levels of sound27,28 and air pollution29,30 are generally higher on weekdays due to structured workweek commuting.

Nighttime PM2.5 levels were consistently elevated, a finding consistent with previous studies in Dhaka20,24 and other cities31. This is likely due to the formation of a shallow and stable nocturnal boundary layer that limits vertical dispersion and traps pollutants near the surface31. This pattern persisted in the wet season but was less pronounced due to rainfall and improved dispersion conditions24.

Elevated nighttime sound, which can worsen sleep quality and quantity32, also showed distinct peaks that aligned with daily calls to prayer. In Dhaka, these are broadcasted through loudspeakers installed on mosque minarets. Similar findings were reported in urban Ghana26 and Cameroon33, where religious soundscapes also contributed to sound. The median IR at rotating sites in our study (median: 50%, IQR: 30) were similar to those in a similar citywide study in Accra, Ghana (median: 53%, IQR: 16)26, though the range of values was larger in our study. Similar trends were observed by site type, with higher IRs at residential sites, likely due to the lower levels of background sound and more sporadic nature of sound sources in these areas. Though our study did not investigate health impacts, previous studies suggest that continuous and intermittent noise may impact health through different mechanisms, with the former activating the sympathetic nervous system and oxidative stress and the latter disrupting sleep and activating stress response34,35.

Our observed BC/PM2.5 ratios were lower than those reported in Nairobi, Mumbai, and Rio de Janeiro but comparable to levels in Delhi, Seoul, Mexico City, and numerous cities in Europe and North America36. The lower ratios in our study might reflect the influence of regional pollution. BC, a carbonaceous pollutant emitted from incomplete combustion and contributor to climate warming37, comprised a larger share of PM2.5 in the dry season and in commercial and mixed-use areas. Elevated BC/PM2.5 ratios at some GBO sites in the dry season likely reflect the impact of nearby brick kilns and biomass burning38, while the decline in these ratios in the wet season aligns with reduced activity of these sources.

An informal (slum) settlement (Shyampur), located in an industrial area in southern Dhaka, emerged as an air pollution hotspot. This site was located near steel re-rolling mills and other small-scale industry and had high air pollution throughout the study period. Shyampur represents an important focal point for future intervention given its persistently high levels of air pollution and large local population of over 184,000 residents39. Mitigation strategies such as stricter emissions controls and the modernization of polluting industries should be considered alongside targeted public health measures for this extremely vulnerable area of Dhaka.

Although no single site was an extreme sound hotspot, several mixed-use areas and transportation corridors consistently recorded high sound levels. Kuril, a major transportation hub with new flyover infrastructure, had high levels of sound but low air pollution relative to other sites in the city. This likely reflects higher vehicle volume combined with improved traffic flow and nearby open space dispersed that helped disperse air pollution. Nilkhet, a dense commercial hub, experienced constant sound levels from heavy pedestrian activity and traffic congestion, including cars, rickshaws, motorcycles, and delivery trucks that navigate its narrow roads and contribute to both sound levels and air pollution. Rajlokkhi, located along the eight-lane Dhaka-Mymensingh highway, recorded the highest sound levels. This major traffic artery sees continuous daytime congestion. Nighttime traffic volume is lower, but high-speed freight trucks and long-haul buses continue to dominate the roadway, sustaining elevated sound levels.

Dhaka’s poor air quality has drawn substantial public attention, prompting several policy and regulatory efforts, including a 2022 ban on two-stroke vehicles and the 2010 Clean Air and Sustainable Environment project which promoted cleaner brick kiln technologies and changes to intersection infrastructure to improve traffic flow23. The spatial variation in PM2.5 in our study suggests that mitigating local sources could yield measurable benefits to air pollution and can inform policy solutions that targeted Dhaka’s urban context. For example, stricter vehicle emissions standards, expanding low-emission zones, and continued investment in public transit could help mitigate the high levels of pollution measured in transportation, commercial, and industrial sites in our study.

Noise pollution has only recently gained policy attention in Dhaka. Bangladesh established noise limits for different land use types in 2006, though there is limited evidence of their enforcement40. In October 2024, the interim government launched a campaign to raise public awareness about noise and phased in a ban on vehicle honking in Dhaka with penalties for the use of horns, aiming to transform the city into a “quiet zone” in 202541. Enforcement remains a challenge42, however traffic control does present a feasible entry point for integrated mitigation. Our findings support enforcement and possible expansion of these measures, including speed control, traffic management, and public transit improvements that can reduce both noise and air pollution.

This study has several limitations to consider in future work. First, long-term continuous pollution monitoring at all sites was not possible due to logistic and equipment constraints. Although we applied temporal adjustments to account for variation in pollution concentrations, we may have over- or under-estimated the ‘true’ season-specific averages at rotating sites. We found the mean RMSE across fixed sites by season when comparing three-day temporally-adjusted measurements with the seasonal mean was 22.3 µg/m³ (dry) and 6.4 µg/m³ (wet). Second, diurnal PM2.5 trends were measured using light-scattering sensors, which are less accurate at high concentrations43. While we found no evidence of non-linearity in sensor-gravimetric comparisons, some measurement error is inevitable. However, any inaccuracies are unlikely to materially affect our conclusions. Third, sound measurements at the rotating sites were limited to three days in the wet season. Although fixed-site data showed no clear seasonal or weekly differences across varied urban sites, we may have missed seasonal patterns at some rotating sites that are relevant to policy. Fourth, battery failures led to some data loss, mainly at fixed sites on the fifth day of measurement. As measurements spanned entire seasons and failures occurred at different days and times throughout, the impact of these missed days on the seasonal mean is likely minimal. Fifth, our source assessments for PM2.5 and sound relied on BC components, land use characteristics and expert judgement rather than chemical speciation or sound recordings; an aligned study is addressing these gaps for future publication. Future research could examine the long-term impacts of environmental interventions, investigate how socioeconomic and infrastructural disparities affect exposures, and quantify the health impacts of PM2.5 and environmental sound.

Dhaka is a rapidly expanding megacity that is grappling with severe air pollution and noise. This study is one of very few to quantitatively assess the intersection of air pollution and sound and their spatiotemporal distributions, which are understudied in Global South cities2. Our measurements indicate that all neighborhoods in Dhaka could benefit from intervention and point to traffic-related policies as a promising entry point for city-wide interventions. We also identified hyper-local hotspots like Shyampur, where industrial emissions drive extreme air pollution, and parts of northern Dhaka where dense traffic and commercial activities contribute to high levels of both air pollution and sound. Our study illustrates an approach for municipalities to prioritize areas for interventions for different health-damaging pollutants and reduce their impacts on this megacity’s large and growing population. It also demonstrates the potential for such environmental data platforms to address questions important in the quest for healthier cities.

Methods

Study design

We conducted measurement campaigns from January 18 to March 17 (dry season) and from July 22 to September 24 (wet season) in 2023. In each campaign, air pollution was measured continuously at eight ‘fixed’ sites and for three consecutive days at 62 ‘rotating’ sites. Sound was continuously monitored at fixed sites in the dry season and expanded to all sites in the wet season. This study followed a similar approach to an environmental campaign in Accra, Ghana44.

Site selection and land use classification

The fixed sites were selected to represent Dhaka’s diverse of environmental features that likely contribute to varying levels of air pollution and sound. The rotating sites were selected via stratified random sampling, where potential locations were randomly distributed throughout Dhaka across strata of land use and population density (Fig. 4).

Location of sampling sites, major roads, and land use categories in Dhaka, Bangladesh. Land use categories were adapted from the World Bank land use/land cover dataset (2017) used for initial site selection. The additional category of ‘mixed-use’ used in the analysis was defined for specific sites prior to data collection.

Each site was assigned a land use classification based on available land use data45, visual inspection of satellite and street-view images, and investigator knowledge. The resulting five categories encompass a broad range of anticipated sound and air pollution levels: (1) residential, (2) commercial and industrial, (3) green, blue, and open (GBO) spaces, (4) transportation corridor, and (5) mixed-use. Residential areas included both planned communities and informal settlements. Commercial and industrial areas were a combined category because of the frequent overlap in those activities. Commercial areas had a high density of office complexes, restaurants, and retail stores, whereas industrial zones had more manufacturing, factories, and warehouses. GBO areas were less developed environments primarily characterized by empty plots and/or natural elements such as parks, agricultural land, or waterways. Transportation corridors were areas of high vehicular traffic or train operations. Mixed-use areas were characterized by a combination of activities without a dominant single category (e.g., equal proportions of commercial and residential activities in the same area). The final classification yielded 19 residential sites (1 fixed, 18 rotating), 16 commercial and/or industrial sites (3 fixed, 13 rotating), 8 green, blue, and open spaces (2 fixed, 6 rotating), 18 transportation corridor sites (2 fixed, 16 rotating), and 9 mixed-use rotating sites.

Real-time and gravimetric measurement of PM2.5

We measured PM2.5 using co-located gravimetric and sensor-based monitors housed in waterproof enclosure at 3–5 m above ground level. Gravimetric and sensor-based monitors were replaced every 5 days at the fixed sites. Gravimetric measurements were collected using Ultrasonic Personal Aerosol Samplers (UPAS v2, Access Sensor Technologies, USA), attached to an external battery (V50 USB Battery Pack, Voltaic). They sampled air at 1.0 L/min46 with a 50% duty cycle, the internal pump would run and then rest in 15 s alternating intervals, to conserve battery power and prevent filter overloading. Monitors housed 37 mm polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) filters (2 μm pore size). Airflow was calibrated pre-deployment and measured post-sampling, with all post-sampling flow rates within 5% of the target. Filter samples and blanks (16%, n = 49) were stored in sealed Petri dishes and at −18 °C before shipment for gravimetric analysis.

Continuous PM2.5 measurements (1 min resolution) were collected using laser-based sensors (Plantower PMS7003, Zefan, Inc., China) with a counting frequency of 98% for particles > 0.5 μm diameter47. The sensors were powered by an external battery and were previously deployed in a range of environmental conditions25,48,49. To account for known biases in optical, sensor-based measurements, we applied a season-specific correction models using co-located gravimetric reference data over a wide range of representative concentrations (300 µg/m3 and 150 µg/m3 in dry and wet seasons respectively)50,51. We examined potential non-linearity in the optical-gravimetric relationship using correlation plots and fitting statistical splines for each season. As no evidence of non-linearity was observed, we proceeded with season-specific linear regression models (Supplementary Note 1). On average, sensors underestimated gravimetric PM2.5 by 36% in the dry season and 2% in the wet season. A separate correction factor was applied to the Shyampur fixed site due to its higher pollutant range. The gravimetric-corrected sensor data were used for analysis.

Filter analysis for mass and BC

Filters were analyzed for their mass and BC before and after sampling at the Colorado State University Automated Air Analysis Facility (AIRLIFT). Post-sampling, filters were cold chain transported to Colorado and stored in a −20 °C freezer. Prior to mass analysis, filters were conditioned (21–22 °C, 30–34% RH) for at least 24 h, discharged with a polonium source for at least 15 s, and weighed on a microbalance (Mettler Toledo Inc., XS3DU, USA, 1 µg resolution). Filters were weighed in triplicate until the difference between three consecutive weights was < 3 µg52. Sampled PM2.5 mass was the difference between pre- and post-sampling filter mass. Sampled mass values were blank-corrected using the median value of the field blank filters (2 µg dry season, 4 µg wet season), and concentrations were calculated by dividing the blank-corrected mass by the sampled air volume (Supplementary Note 2).

BC was quantified using an optical transmissometer (SootScan OT21, Magee Scientific, USA) where the difference between in pre- versus post-sampling light attenuation on each filter was converted to mass surface loading using a mass absorption cross section of 16.6 m2/g for an 880 nm channel optical BC53. We calculated the BC concentrations by subtracting the median field blank values (2.03 dry season, 0.15 wet season), converting the optical measurements to mass, multiplying the surface loadings by the sampled surface area of the filters (8.6 cm2), and dividing by the sampled volume of air (Supplementary Note 2).

Sound level data collection and processing

We measured A-weighted sound levels (dBA) using three sound level meters models with type 1 digital MEMS microphones (NSRT_mk3, NSRT_mk4, and NS110; Convergence Instruments, Montreal, Canada) that were factory-calibrated and co-located before each campaign to ensure their precision and accuracy (Supplementary Note 3). Sound monitors were deployed at the same locations as air pollution devices and programmed to continuously capture sound (dBA) at one-minute intervals for three days at rotating sites (wet season only) or continuously at fixed sites (both seasons). Dry season measurements were limited to fixed sites due to equipment availability. We did not observe any systematic differences in seasonal sound levels at fixed sites (Supplementary Note 4), and thus combined the data from both seasons for statistical analysis. We describe our results as “sound” rather than “noise” to recognize that auditory experiences in Dhaka encompass both desired and undesired or unpleasant sound.

Statistical analysis

Continuous data from fixed sites showed that air pollution decreased over time in the dry season and was slightly higher in August in the wet season (Supplementary Note 4), which compromises the comparability of the raw rotating site data that were collected at different times. We therefore applied a weekly-specific temporal adjustment factor (TAF) to the gravimetric-corrected PM2.5 and BC values25, calculated as the ratio of weekly mean PM2.5 or BC at fixed sites and the US embassy monitor (www.airnow.gov), for PM2.5, to the seasonal mean (excluding Shyampur) (Supplementary Note 5). We calculated season-specific means and standard deviations of temporally-adjusted PM2.5 and BC, using the TAF, for each site. These seasonal values were then averaged to estimate an annual means and standard deviations.

The following sound metrics were calculated for each site:

-

A-weighted equivalent continuous daily sound levels (LAeq (dBA)).

-

A-weighted equivalent continuous daytime sound levels between 6:00 and 20:59 h (Lday (dBA)).

-

A-weighted equivalent continuous nighttime sound levels between 21:00 and 5:59 h (Lnight (dBA)).

-

Daily intermittency ratio (IR (%)) (calculation in Supplementary Note 6).

-

Daytime intermittency ratio between 6:00 and 20:59 h (IRday (%)).

-

Nighttime intermittency ratio between 21:00 and 5:59 h (IRnight (%)).

The equivalent continuous sound level (LAeq) represents the average sound pressure level over time, capturing total sound energy54. We calculated overall LAeq and LAeq for daytime and nighttime hours to capture within-day variation. The IR measures the disruptiveness of sound events relative to continuous background levels, which LAeq does not measure. A high IR (%) indicates a high percentage of sound energy is distinct enough from the background levels to qualify as an “event”55. For the main analysis, we defined a sound event using a cut-off of + 4 dBA above the site-specific LAeq (overall, daytime, or nighttime), accounting for Dhaka’s high background sound levels. Sensitivity analyses evaluated lower (+ 3 dBA) and higher (+ 5 dBA) cut-off values (Supplementary Table 6; Supplementary Note 7). Summary statistics were based on median values due to the non-linear decibel scale.

We retained all air pollution and sound measurements that captured at least 24 h of measurement. The temporal analysis consisted of seasonal, weekly (for TAF), daily, and diurnal variations in air pollution and sound, and the spatial analysis consisted of summary statistics across sites and by land use type. We estimated the differences in mean air pollution and median sound by season and day of the week using linear regression models with site-specific cluster-robust standard errors56. A Spearman correlation matrix was calculated to evaluate the relationship between site averaged air (PM2.5, BC, BC/PM2.5 ratio) and sound (LAeq, IR) measures. Kruskal-Wallis rank sum tests were used to examine the differences by land use types.

All analyses were conducted in R (version 4.4.1).

Data availability

The site data used in this study is available online [https://github.com/mlee725/Spatiotemporal-patterns-in-air-pollution-and-sound-in-Dhaka-Bangladesh]. Additional data may be requested from corresponding authors for research purposes.

References

Marlier, M. E., Jina, A. S., Kinney, P. L. & DeFries, R. S. Extreme air pollution in global megacities. Curr. Clim. Change Rep. 2 (1), 15–27 (2016).

Chen, Y., Hansell, A. L., Clark, S. N. & Cai, Y. S. Environmental noise and health in low-middle-income-countries: A systematic review of epidemiological evidence. Environ. Pollut. 316 (2023).

World Urbanization Prospects: The 2018 Revision, Online Edition [Internet]. [cited March 10, 2025]. (2018).

Pavel, M. R. S. et al. 2003–2019) air quality, climate variables, and human health consequences in dhaka, Bangladesh. Front. Sustain. Cities. 3, 681759 (2021).

World Health Organization. World Health Organization Global Air Quality Guidelines: Particulate Matter (PM2.5 and PM10), Ozone, Nitrogen Dioxide, Sulfur Dioxide and Carbon Monoxide (World Health Organization, 2021).

Health Effects Institute Air quality and health. In Cities: A State of Global Air Report 2022 (Health Effects Institute, 2022).

Quader, M. A. et al. Evaluation of noise pollution impact on health in Dhaka City. Bangladesh Front. Public. Health. 12, 1477684 (2024).

Dey, A. R., Kabir, N. & Effroymson, D. Noise Pollution in Dhaka: Current Situation and Suggestions for Action (Work for a better Bangladesh, 2004).

Aletta, F. Listening to cities: from noisy environments to positive soundscapes. Frontiers 2022: Noise, Blazes and Mismatches. 7–22. (2022).

Government of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh - Ministry of Environment and Forest. Noise Pollution Control Rules. (2006).

World Health Organization. Environmental noise guidelines for the European Region: Executive summary. (2018).

Vohra, K. et al. Rapid rise in premature mortality due to anthropogenic air pollution in fast-growing tropical cities from 2005 to 2018. Sci. Adv. 8 (14), eabm4435 (2022).

Cosselman, K. E., Navas-Acien, A. & Kaufman, J. D. Environmental factors in cardiovascular disease. Nat. Reviews Cardiol. 12 (11), 627–642 (2015).

Ciabattini, M., Rizzello, E., Lucaroni, F., Palombi, L. & Boffetta, P. Systematic review and meta-analysis of recent high-quality studies on exposure to particulate matter and risk of lung cancer. Environ. Res. 196, 110440 (2021).

Thompson, R. et al. Air pollution and human cognition: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci. Total Environ. ;859. (2023).

Sheppard, A., Ralli, M., Gilardi, A. & Salvi, R. Occupational noise: auditory and Non-Auditory consequences. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 17, 23 (2020).

Pramanik, M. M. A. & Stathakis, D. Forecasting urban sprawl in Dhaka City of Bangladesh. Environ. Plan. 43 (4), 756–771 (2016).

Institute for Economics & Peace. Ecological Threat Report 2023: Analysing Ecological Threats, Resilience & Peace. Sydney November (2023).

Ahmad, S. et al. Housing adequacy in delhi, Dhaka and karachi: strategies for promoting sustainable and inclusive housing. Cities 160, 105779 (2025).

Rahman, M. M., Mahamud, S. & Thurston, G. D. Recent Spatial gradients and time trends in dhaka, bangladesh, air pollution and their human health implications. J. Air Waste Manag. Assoc. 69 (4), 478–501 (2019).

Ahmed, F., Bayazid, A. Z. M., Islam, M. M., Rahaman, M. Z. & Al Muntasir, M. F. The terrible air pollution in Dhaka City is getting worse. GSC Adv. Res. Rev. 19, 42–52 (2024).

Rana, M. M., Sulaiman, N., Sivertsen, B., Khan, M. F. & Nasreen, S. Trends in atmospheric particulate matter in dhaka, bangladesh, and the vicinity. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 23 (17), 17393–17403 (2016).

Begum, B. A. & Hopke, P. K. Ambient air quality in Dhaka Bangladesh over two decades: impacts of policy on air quality. Aerosol Air Qual. Res. 18 (7), 1910–1920 (2024).

Sarwar, G. et al. Characterizing variations in ambient PM2.5 concentrations at the U.S. Embassy in dhaka, Bangladesh using observations and the CMAQ modeling system. Atmos. Environ. ;296. (2023).

Alli, A. S. et al. Spatial-temporal patterns of ambient fine particulate matter (PM2.5) and black carbon (BC) pollution in Accra. Environ. Res. Lett. 16(7) (2021).

Clark, S. N. et al. Space-time characterization of community noise and sound sources in accra, Ghana. Sci. Rep. 11(1) (2021).

Kheirbek, I. et al. Spatial variation in environmental noise and air pollution in new York City. J. Urban Health: Bull. New. York Acad. Med. 91 (3), 415–431 (2014).

Neitzel, R. L., Svensson, E. B., Sayler, S. K. & Ann-Christin, J. A comparison of occupational and nonoccupational noise exposures in Sweden. Noise Health. 16 (72), 270–278 (2014).

Elansky, N. F., Shilkin, A. V., Ponomarev, N. A., Semutnikova, E. G. & Zakharova, P. V. Weekly patterns and weekend effects of air pollution in the Moscow megacity. Atmos. Environ. 224.

Jones, A. M., Yin, J. & Harrison, R. M. The weekday–weekend difference and the Estimation of the non-vehicle contributions to the urban increment of airborne particulate matter. Atmos. Environ. 42 (19), 4467–4479 (2008).

Manning, M. I., Martin, R. V., Hasenkopf, C., Flasher, J. & Li, C. Diurnal patterns in global fine particulate matter concentration. Environ. Sci. Technol. Lett. 5 (11), 687–691 (2018).

Sarker, M. R., Hossain, S. A. & Khatun, A. Effect of Noise on Human Psychology in Public Spaces of Dhaka City. (2019).

Mathieu Juliot Mpabe, B. Regulations of noise pollution emitted by revival churches and the well-being of neighboring populations in Cameroon. Environmental Economics [Internet]. ; 11(1):[82–95 pp.]. (2020). Available from: https://doi.org/10.21511/ee.11(1).2020.08

Sørensen, M. et al. Health position paper and redox perspectives-Disease burden by transportation noise. Redox Biol. 69, 102995 (2024).

Eriksson, C., Pershagen, G. & Nilsson, M. Biological Mechanisms Related To Cardiovascular and Metabolic Effects by Environmental Noise. In: World Health Organization (Regional Office for Europe, 2018).

Kirago, L., Gatari, M. J., Gustafsson, Ö. & Andersson, A. Black carbon emissions from traffic contribute substantially to air pollution in Nairobi, Kenya. Commun. Earth Environ. 3(1). (2022).

Debnath, S. et al. Black carbon emissions and its impact on the monsoon rainfall patterns over the Indian subcontinent: Insights into localized warming effects. Atmos. Environ.: X. 22 (2024).

Guttikunda, S. K., Begum, B. A. & Wadud, Z. Particulate pollution from brick kiln clusters in the greater Dhaka region. Bangladesh Air Qual. Atmos. Health: Int. J. 6 (2), 357–365 (2013).

Statistics, B. Population and housing census 2011. Dhaka: BBS. 4, 574 (2012).

Karim, M. E., Taher, M. A. & Karim, M. A. Noise pollution in Dhaka and the constitutional right to life. Australian J. Asian Law [Internet]. 21 (2), 67–84 (2021). pp.].

Silent Zone area launched at airport to combat noise pollution. Dhaka Tribune. Oct 1, 2024. (2024).

Hasan, R. A. Decibels and dilemmas: Tackling Dhaka’s noise pollution crisis. Dly. Star. 18, (2024).

Malings, C. et al. Fine particle mass monitoring with low-cost sensors: corrections and long-term performance evaluation. Aerosol Sci. Technol. 54 (2), 160–174 (2020).

Clark, S. N. et al. High-resolution Spatiotemporal measurement of air and environmental noise pollution in Sub-Saharan African cities: pathways to equitable health cities study protocol for accra, Ghana. BMJ Open. 10 (8), e035798 (2020).

World Bank Group. Dhaka (Bangladesh) - Land Use / Land Cover Maps (ESA EO4SD-Urban). (2020).

Volckens, J. et al. Development and evaluation of an ultrasonic personal aerosol sampler. Indoor Air. 27 (2), 409–416 (2017).

Bulot, F. M. et al. Long-term field comparison of multiple low-cost particulate matter sensors in an outdoor urban environment. Sci. Rep. 9 (1), 7497 (2019).

Levy Zamora, M. et al. Field and laboratory evaluations of the low-cost plantower particulate matter sensor. Environ. Sci. Technol. 53 (2), 838–849 (2018).

Li, X. et al. Socioeconomic and demographic associations with wintertime air pollution exposures at household, community, and district scales in rural Beijing, China. Environ. Sci. Technol. 56 (12), 8308–8318 (2022).

Sayahi, T., Butterfield, A. & Kelly, K. Long-term field evaluation of the plantower PMS low-cost particulate matter sensors. Environ. Pollut. 245, 932–940 (2019).

Le, S. et al. Calibration of Low-Cost sensor data for ambient PM2. 5 monitoring across urban and rural settings in South central Uganda. Atmos. Pollut. Res. 102580. (2025).

L’Orange, C., Neymark, G., Carter, E. & Volckens, J. A High-throughput, robotic system for analysis of aerosol sampling filters. Aerosol Air Qual. Res. ;21(11) (2021).

Ahmed, T. et al. Measurement of black carbon (BC) by an optical method and a thermal-optical method: intercomparison for four sites. Atmos. Environ. 43 (40), 6305–6311 (2009).

Majidi, F. & Khosravi, Y. Abedi k-D. Determination of the equivalent continuous sound level (Leq) in industrial indoor space using GIS-based noise mapping. J. Hum. Environ. Health Promotion. 5 (2), 50–55 (2019).

Wunderli, J. M. et al. Intermittency ratio: A metric reflecting short-term Temporal variations of transportation noise exposure. J. Expo. Sci. Environ. Epidemiol. 26 (6), 575–585 (2016).

Pustejovsky, J. E. & Tipton, E. Small-sample methods for cluster-robust variance Estimation and hypothesis testing in fixed effects models. J. Bus. Econ. Stat. 36 (4), 672–683 (2018).

Acknowledgements

We thank the field staff and communities in Dhaka for assistance with data collection. This work is supported by a Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC) Discovery Grant [RGPIN-2022-05380] and the Pathways to Equitable Healthy Cities grant from the Wellcome Trust [209376/Z/17/Z]. The funders had no role in the study design, collection, analysis, interpretation of data, or writing of the manuscript. For the purpose of Open Access, the author has applied a CC BY public copyright license to any Author Accepted Manuscript version arising from this submission.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Z.Q. and J. B. provided funding and equipment for this study. A.R.B. ran the field sampling campaign with help from M.L., R.H.K., B.B., Z.Q. and J. B. M.L., L.R., and J.B. wrote the main manuscript text with input from A.R.B. M.L. and L.R. prepared all figures and tables and ran data cleaning and analysis. L.R. was involved with initial drafts of the manuscript with M.L. taking over later work. All authors reviewed the manuscript and provided input on study design and analysis methods.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lee, M., Bayazid, A.R., Rosenthal, L. et al. Spatiotemporal patterns in air pollution and sound in Dhaka, Bangladesh. Sci Rep 15, 32852 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-12815-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-12815-9