Abstract

Based on the theory of chaotic modulation, the influence of the control parameters of impingement jets on the stability of the system has been studied. The range of the simulation control parameters is determined through trial calculation. The influence of the main control parameters of the nonlinear system on the stability of pressure and pressure gradient trajectories has been studied numerically. The fluctuation curves of the damping force, recovery force, and kinetic energy and potential energy have been further studied. The results show that the main control parameters affect the waveform of the self-excited oscillation and the energy conversion of the impingement jet system. When the control parameters take specific values, the nonlinear system bifurcates and a regular periodic solution can be obtained. The results suggest the values of the control parameters that form a clear synergistic effect, which facilitates the conversion utilization of self-excited oscillation energy, and in which a stable oscillation can be formed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Jet impingement is a flow phenomenon with both engineering applications and theoretical research prospects. Jet impingement heat transfer is utilized in many engineering applications such as gas turbine internal cooling of stationary and rotating parts, cooling of high-power electronics, thermal management in metal processing, and glass tempering1. However, the jet impingement process generally has high energy consumption and low efficiency2,3. To reduce the energy consumption of jet equipment, scholars have designed various new types of jet devices based on the principal knowledge of fluid mechanics. Xu et al.4 proposed a new swirler to excite the swirling jet to achieve the uniform and efficient impingement cooling, that is, the inner wall of a circular hole is provided with four spiral grooves similar to the conventional circular hole with internal threads. Husain5 proposes a novel hybrid design of a heat sink based on micro-channel, -pillar, and -jet impingement. A prototype of a PVT solar water collector installed with a jet impingement and compound parabolic collector has been designed by Jaaz6. Youn et al.7 explored the heat transfer characteristics of jet array impingement with effusion holes and provided basic data for the design of a gas-turbine casing cooling system.

In addition to improving the equipment design, other researchers have studied the mechanism of the impact jet and the relationship between the control parameters in the jet process. Moosavian et al.3 experimentally studied the behavior of liquid nitrogen jets and dual-like jet impingement of liquid nitrogen discharged from needle injectors. By changing the velocities of the liquid jets, they obtained optimal pressure and temperature properties for the fully developed impingement jet. Jet impingement is considered to be an effective technique to enhance the heat transfer rate1, and it has many applications on the scientific and industrial horizons8. Matheswaran et al.9 studied jet impingement applications in solar systems. Singh et al.10 and Lim et al.11 investigated jet impingement applications in aerospace technology, and Li et al.12 investigated the air-impingement jet drying applied in drying preserved figs.

In the impact jet system, the working medium is a fast-flowing fluid, and there are many nonlinear factors in the system. Jun Li et al.13 introduced the concept of the chaos interval by chaotic mapping, and the CIMPSO algorithm is proposed to optimize the multi-objective rotor system model with nonlinear variables. The self-excited oscillation of a large aspect ratio planar jet impinging on a flat plate was investigated by Arthurs and Ziada14, Cui et al.15 investigated the bubble dynamics and pressure oscillations of a one-dimensional confined jet array impingement boiling of highly subcooled water on a smooth silicon wafer surface under periodical heat fluxes. Eman et al.16 studied the nonlinear vibrations of a cantilever beam model and the dynamic analysis of several resonances controlled by the proportional-derivative (PD) control. Hossain et al.9 evaluated the effects of the exit nozzle configuration of a fluidic oscillator on the flow field and impingement heat transfer performance downstream on a flat plate. They provided the relationship between the jet oscillation frequency and the nozzle configurations.

By controlling the parameters of pressure and flow to change the fluid injection mode, the fluid appears in an unsteady state, which can enhance the impact force of the fluid jet process. This is more economical than simply increasing the continuous jet pressure or flow. The periodic oscillations of parameters, such as pressure, are an autonomous system. This is because the self-excited oscillation does not bear the oscillation produced under the action of periodic external forces, does not contain time in the differential equation, and is reflected in a limit ring in the phase plane.

According to our investigation, it can be seen that the current research on impact jets mainly focuses on the specific nozzle experiment or variation of the control parameters of the jet process. There are relatively few studies on the topic of the chaos modulation mechanism of the jet impingement process and its influence on the energy conversion during the jet process. In this study, the influence of the control parameters of the impingement jet on the stability of the system has been studied based on the theory of chaotic modulation. The influence of system control parameters on the stability of pressure and pressure gradient trajectories has been studied, as well as the fluctuation curves of the damping force, recovery force, kinetic energy, and potential energy.

Mathematical model of the jet network

Mathematical model of the jet network based on the RLC oscillatory loop

Fluid network theory is a new branch of applied science for the study of the transmission and transient change of fluid in pipelines developed on the basis of fluid mechanics combined with electrical network theory. According to the principle of equivalence, the pressure difference in the fluid network is equivalent to voltage, the flow rate is equivalent to current, and the flow resistance, flow inductance, and flow capacity in the fluid network are equivalent to the resistance, inductance, and capacitor in the electrical network.

The jet problem is regarded as an RLC loop composed of basic jet network parameters such as flow capacity, flow resistance, and flow inductance. Combined with electrical network theory, the simulation relationship between these two networks could be established. Flow resistance, flow inductance, and flow capacity in the fluid network are only related to the structure of the fluid network system and the nature of the fluid.

In a system of mass flow, the parameters of each jet network can be calculated using the following calculation methods.

Flow resistance represents the viscous resistance to the fluid flow, and it only represents the size of the pressure difference per unit flow: \(\:R=(\nu\:\sqrt{\zeta\:}\))/(ACf), where v is the average fluid velocity in m/s, ζ is the nozzle local resistance coefficient, A is the nozzle cross-sectional area in m2and Cf is the nozzle flow coefficient. In the linear case, the flow resistance can also be written as follows:

where µ is the fluid viscosity coefficient, l is the tube length, D0 is the pipe diameter, and ρ is the density in kg/m3. The flow inductance (L) is written as: \(\:L=4{l}_{0}/\left(\pi\:{D}_{0}^{2}\right)\), which indicates the degree of pressure change caused by a fluid mass’ acceleration or deceleration due to inertia in m−1. Here, D0 and l0 indicate the length and diameter of the front pipe, respectively, in m.

The flow capacity (C) is written as: \(\:C=\pi\:{D}^{2}{L}_{z}/\left(4{a}^{2}\right)\), which reflects the ratio of mass change to pressure change of the fluid in the oscillation cavity. Here, D is the diameter of the oscillation cavity, and Lz is the disturbance wave speed of the fluid in the oscillation cavity in m/s.

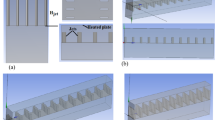

Figure 1b is based on the jet equivalent line network model established in Fig. 1a. Using the fluid node law and the fluid loop law, the jet network model shown in Fig. 1b is established by the following pressure and flow equations:

where QL is the input flow, Q is the output flow, QC is the flow through the capacitance, R is the resistance coefficient, P is the outlet pressure, and P0 is the incoming pressure.

The flow resistance characteristic of the nozzle is given by

where a and b are both constants.

According to Eqs. (1)–(3), the following relationship can be obtained:

Changing Eq. (4) with variables, standardizing it with x = αP, and ordering the variables give.

\({\alpha ^{\text{2}}}= - \frac{{3aL}}{{bL+RC}}\), \(\beta = - \frac{{RC+bL}}{{LC}}\), \({\xi ^{\text{2}}}=\frac{{Rb+1}}{{LC}}\), \(\varepsilon = - \frac{{{R^2}C+bRL}}{{3{L^2}C}}\),

\(\:f\text{cos}\omega\:t=\frac{{P}_{0}}{LC}\sqrt{\frac{-3aL}{RC+bL}}\).

Then, Eq. (4) can be written as follows:

This equation is a nonho mogeneous nonlinear differential equation with the nozzle outlet pressure as the variable. The variations in the nozzle outlet pressure, which takes the form of an unsteady water jet, can be determined from the solution to this equation. This equation belongs to the dynamic form of equations for general oscillation systems, namely the Liénard equation, which is a van der Pol–Duffing type:

where f(x) indicates the damping force, and g(x) indicates the recovery force of the system and where the system has a stable limit cycle when the following conditions are established:

-

(1)

f (x) is an even function, f (0) < 0, g (x) is an odd function, and xg (x) > 0 (x = 0); β > 0, \(\xi > - \varepsilon \left| x \right|\);

-

(2)

Both f (x) and g (x) are the analytic functions of x;

-

(3)

When x→±∞, \(F(x)=\int {f(x)} dx\)→±∞;

-

(4)

F (x) = 0 has a unique positive root x = a, and F (x) increases monotonically when x > a.

If the above conditions are met, then β > 0. The kinetic energy of the system is given by \(T=\frac{1}{2}{\left( {\frac{{dx}}{{dt}}} \right)^2}\), and the potential energy of the system is given by \(U=\int {g(x)} dx\). Then, Eq. (6) becomes

To examine the balance point, we let

According to Eq. (9), the following equation is obtained:

The roots of this equation are

where.

\({\omega _1}=\frac{{ - 1+\sqrt 3 i}}{2}\), \({\omega _2}=\frac{{ - 1 - \sqrt 3 i}}{2}\), \(p=\frac{{{\xi ^2}}}{\varepsilon }\), \(q= - \frac{f}{\varepsilon }\).

In Eq. (10), when \(\Delta =\frac{{{q^2}}}{4}+\frac{{{p^3}}}{{27}}={\text{0}}\), i.e., when \({f^2}\varepsilon = - \frac{{4{\xi ^6}}}{{27}}\), Eq. (10) has three real roots, among which there is a double root.

\({x_{1,1}}=\sqrt[{\text{3}}]{{\frac{{{\text{4}}f}}{\varepsilon }}},{x_{1,2}}={x_{1,3}}= - \sqrt[{\text{3}}]{{\frac{f}{{2\varepsilon }}}}\)

The equilibrium point (\(\sqrt[{\text{3}}]{{\frac{{{\text{4}}f}}{\varepsilon }}}\), 0,0) examines the stability of system (8). The characteristic equation of the corresponding Jacobi matrix is found to be as follows:

Solving this equation, we obtain three different real roots:

where\(b= - \beta (1+\frac{{4{\xi ^2}}}{{3\varepsilon }})\) and \(\Delta ={\beta ^2}{(1+\frac{{4{\xi ^2}}}{{3\varepsilon }})^2}+12{\xi ^2}\). ξ2 > 0 implies that λ2 > 0, λ3 < 0, and since \({\zeta _{\text{0}}}=\mathop {\hbox{max} }\limits_{{i=1:3}} \left\{ {\operatorname{Re} {\lambda _i}} \right\}>0\), the zero-solution of the nonlinear system (14) is unstable. According to the Hartman-Grobman theorem, the singularity x0 (\(\sqrt[{\text{3}}]{{\frac{{{\text{4}}f}}{\varepsilon }}}\), 0,0) is a hyperbolic singularity of the nonlinear system (8), i.e., the degenerate singularity. Using a similar method, the stability of system (8) at (\(- \sqrt[{\text{3}}]{{\frac{f}{{2\varepsilon }}}}\), 0,0) could be investigated using the Jacobi matrix of that point. The three solutions of the corresponding characteristic equation of the Jacobi matrix are as follows:

According to the Hartman-Grobman theorem, the singularity (\(- \sqrt[{\text{3}}]{{\frac{f}{{2\varepsilon }}}}\), 0,0) is also the degenerate singularity of the nonlinear system (8). Further analyzing the solution, \(\varepsilon <0\)and when \({\xi ^{\text{2}}}> - 3\varepsilon\) and \({\lambda _3}<0\), \({\zeta _{\text{0}}}=\mathop {\hbox{max} }\limits_{{i=1:3}} \left\{ {\operatorname{Re} {\lambda _i}} \right\}=0\). At this point, the stability of the nonlinear system zero solution is uncertain, and periodic oscillations may occur. Through the above analysis, the value range and the stability of the control parameters are summarized: when β > 0, \({f^2}\varepsilon = - \frac{{4{\xi ^6}}}{{27}}\),\(\varepsilon <0\), and \({\xi ^{\text{2}}}> - 3\varepsilon\), system (8) may exit self-excited oscillations.

Control parameter selection for the simulation scheme

According to the value range of the previous control parameters and their influence on the solution, the parameters in the numerical calculation are shown in Table 1. In the process of trial calculation, it is found that the values of ε and β have a significant influence on the results. Therefore, these two parameters are taken as the main parameters, and the reasonable values of other parameters are taken according to the above study. In the process of trial calculation, we also found that when the value of ε is less than − 1, no numerical solution can be obtained regardless of how the value of β is adjusted. So, we take the values of ε as − 0.1, − 0.01, − 0.001, and − 0.0001. The frequency ω = 4 was selected as a reference scaling factor to standardize the dimensionless analysis. According our computing tests, lower ω (e.g., ω < 2) system exhibits slower oscillations but requires longer stabilization times, while higher ω (e.g., ω > 6) system induces high-frequency noise, obscuring limit cycle formation.

Chaos modulation mechanism of an unsteady constant jet

Since there are no effective analytical solutions for nonlinear equations, a numerical method to solve the system of Eq. (8) has been used in this study. Cui et al.17 studied on the limit cycles, period-doubling, and quasi-periodic solutions of the forced Van der Pol-Duffing oscillator. The solutions of the nonlinear equations are generally divided into the categories of a stable stationary solution, a divergent solution, and an oscillatory solution. The oscillatory solution includes periodic solutions and chaotic solutions. For the Eq. (5) obtained by the network model of a nonstationary water jet, we are most concerned about the conditions for the existence of periodic and chaotic solutions. Periodic solutions correspond to stable limit cycles. The periodic/chaotic oscillatory solutions are used to calculate the values of some parameters and carry out qualitative analysis.

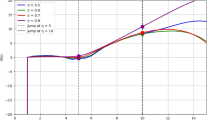

Figure 2 shows the numerical solutions under the control parameters in Table 1, including the pressure and pressure gradient variations with time, and also the relationship between the three. As shown in Fig. 2, the four cases A1, B1, C1, and D1 represent when β = 10, ε equals − 0.1, − 0.01, − 0.001, and − 0.0001, respectively. The four cases all present limit cycles of a similar shape. When ε is − 0.1, see (A1) in Fig. 2, the limit cycle trajectory converges, its shape is regular, and the pressure variation spectrum has longer periods. When ε is − 0.01 and − 0.001, see (B1) and (C1) in Fig. 2, the pressure spectrum has a shorter period, chaos emerges near the attractors of the limit cycle trajectories, and the trajectories become loose. When ε is − 0.0001, see (D1) in Fig. 2, the pressure spectrum period becomes shorter, there is chaos disappearance near the attractors of the limit cycle, and is replaced by a small limit cycle. It can be seen that when other values are certain, ε mainly affects the frequency of the pressure change and the change law within each cycle, and it has no effect on the phase, pressure amplitude, and time domain of the limit cycle. Similarly, from the calculation results of A2, B2, C2, and D2 in Fig. 2, we find that when β = 1, ε takes − 0.1, − 0.01, and − 0.001 In this regime, the oscillation period decreases as ε increases and the range of the limit cycle gradually increases. When ε equals − 0.0001, the limit cycle exhibits stable, periodic solutions. According the classification of the oscillations18all the solutions belong to quasiperiodic or periodic oscillation.

Based on the numerical results of the two groups, the analysis results of the nonlinear system (8) are reasonable. According to the results of the analysis, the periodic or chaotic solutions can be obtained. When β equals 10, the nonlinear system bifurcates, and the regular periodic solution can be obtained. When β equals 1 and ε equals − 0.0001, the system trends toward a stable periodic solution.

Figure 3 compares the variation of pressure over time for all the cases simulated in this study. It is clear that in terms of the value of β (1 or 10), the period of oscillation decreases with increasing ε in the calculated range, and a change in ε and β does not affect the pressure amplitude. When β is 10, the oscillation curve is relatively regular, but when β is 1 and ε is − 0.1, − 0.01, and − 0.001, the oscillation curve is regular but chaotic. When the absolute value of ε decreases to − 0.0001, the oscillation is stable with a constant amplitude and has a regular period.

Energy analysis

To analyze the influence of the control parameters further, we also analyze the damping force f(x)\(\frac{{dx}}{{dt}}\), recovery force g (x), kinetic energy (T), and potential energy (U) in Eq. (5) from the perspective of system energy conversion. Unlike classical van der Pol-Duffing studies17,19, this work studied the energy conversion here. As mentioned above, the self-excited oscillation requires the system to have negative damping and real resilience. In the case of negative damping, the total energy of the system increases, the resilience increases, and the amplitude increases. In the case of positive damping, the system energy dissipates, the recovery force decreases, and the amplitude decreases. The two forces of damping and recovery alternating up and down form the self-excited oscillation.

Figure 4 shows the variation in the spectra of the damping force (f ξ) and the recovery force (fg). Figure 4 shows that for the first three groups, A1, B1, and C1 (i.e., β = 10, ε = −0.1, − 0.01, − 0.001, respectively), the vibrational waveforms of the damping force and the recovery force are almost completely symmetrically complementary about the zero axis, and the two energies are fully converted. For case D1 (β = 10, ε = − 0.0001), the vibration trend of the damping force and the recovery force remains symmetric, but the damping force appears as a small peak. The vibrational waveforms of the damping force and the recovery force are not completely symmetric, which suggests that the energy is not fully converted at this time. For the latter four cases, A2, B2, C2, and D2 (i.e., β = 1, ε = −0.1, − 0.01, − 0.001, and − 0.0001, respectively), only case D2 shows a complementary relationship between the vibrational waveform of the damping force and the recovery force, which the symmetry indicates energy conservation. The remaining three cases are more chaotic and fail to present a more regular correspondence. Combining the results of the previous study, A2, B2, and C2 all showed irregular oscillations, and there are no stable periodic solutions, while D2 reached a stable oscillation, with a stable, periodic solution. This indicates that the complementarity nature of the damping force and the recovery force in case D2 is conducive to the full utilization and conversion of the system energy to form a stable self-excited oscillatory jet. Additionally, combined with Fig. 3, it is obvious that the damping force curves of A1, B1, C1, and D1 in Fig. 4 mutate with the pressure oscillation, and it is this large mutation of damping over a short time frame that powers the pressure to sustain self-excitation oscillations. However, in these four cases, resilience was consistently stable in amplitude without amplification mutation. For the four cases, A2, B2, C2, and D2, there are also no mutation effects of amplification. The amplitude range of both the damping force and the recovery force is small, and the recovery force is greater than the damping force.

From the above analysis, it is inferred that when β = 10, it is easier for the system to form a clear synergy, which is conducive to the conversion and utilization of self-excited oscillation energy. Meanwhile, when β = 1, only when the algebraic value of ε is large (− 0.0001) can a stable oscillation be formed. As the ε value decreases, the oscillation synergistic effect becomes worse, so that sufficient energy conversion and utilization cannot happen.

For the kinetic energy (T) and potential energy (U) change curves in Fig. 4, when β = 10, the kinetic energy changes at the same frequency with the oscillation period, all four groups showed periodic amplification, and the potential energy fluctuates periodically in a small range of the same frequency with recovery force. When β = 1, there are no regular oscillations formed for any of the cases A2, B2, and C2. This chaotic, non-cooperative oscillation results in energy consumption, but it also leads to a narrow amplitude range of kinetic energy. Only for the case D2, i.e., when β = 1 and ε = − 0.0001, does a periodic cooperative oscillation form, the kinetic energy regularly fluctuates in equal amplitude with small periods, the amplitude is relatively large, and the equilibrium points of kinetic energy and potential energy both move up to positions greater than 0.

Conclusions

Based on the theory of chaotic modulation, the influence of the control parameters of jet impingement on the stability of the system has been studied. The range of simulation control parameters is determined through trial calculation. The influence of different control parameters (β and ε) of the nonlinear system on the stability of pressure and pressure gradient trajectories has been obtained. The fluctuation curves of the damping force, recovery force, kinetic energy, and potential energy have been further studied. The results show that the control parameters β and ε affect the waveform of the self-excited oscillation and the energy conversion of the impingement jet system. When β = 10, this nonlinear system bifurcates, and a regular periodic solution can be obtained. When β = 1, the system trends toward a stable periodic solution at ε equals − 0.0001. When other values are certain, ε primarily affects the frequency of the pressure change and the change law within each cycle and nearly has no effect on the phase, pressure amplitude, and time domain of the limit cycles. When β = 10, it is easier to form a clear synergistic effect, which facilitates the conversion utilization of the self-excited oscillation energy. When β = 1, a stable oscillation can be formed only when ε is − 0.0001. While ξ and ω were held constant in this study for parametric isolation, they serve as secondary control parameters influencing damping characteristics (ξ) and oscillation scaling (ω). Systematic variation of these parameters will be pursued in future work to quantify their synergistic effects with β and ε on energy conversion efficiency. In the future studies, according to the influence of the two important control parameters β and ε on the jet process and energy conversion, the flow resistance, flow inductance, and flow capacity should be adjusted to achieve the ideal state of jet impingement. Also, PIV/High-speed imaging could be conducted to visualize flow structures during self-excited oscillations to correlate with pressure spectra.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Ekkad, S. V. & Singh, P. A. Modern review on jet impingement heat transfer methods. J. Heat. Transfer-Trans. ASME. 143 (6), 064001 (2021).

Li, Z. et al. Lift augmentation potential of the circulation control wing driven by sweeping jets. AIAA J. 60 (8), 4677–4698 (2022).

Moosavian, D., Ghassemi, H. & Mostofizadeh, A. Experimental study of atomization of liquid nitrogen jet impingement. J. Braz. Soc. Mech. Sci. Eng. 45, 302 (2023).

Xu, L. et al. Flow and heat transfer characteristics of a swirling impinging jet issuing from a threaded nozzle. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 25, 100970 (2021).

Husain, A., Ariz, M., Al-Rawahi, N. Z. H. & Ansari, M. Z. Thermal performance analysis of a hybrid micro-channel, -pillar and -jet impingement heat sink. Appl. Therm. Eng. 102, 989–1000 (2016).

Jaaz, A. H. et al. Outdoor performance analysis of a photovoltaic thermal (PVT) collector with jet impingement and compound parabolic concentrator (CPC). Materials. 10 (8), 888 (2017).

Youn, J. S., Choi, W. W. & Kim, S. M. Numerical investigation of jet array impingement cooling with effusion holes. Appl. Therm. Eng. 197, 117347 (2021).

Hussain, L. et al. Heat transfer augmentation through different jet impingement techniques: A state-of-the-art review. Energies. 14, 6458 (2021).

Matheswaran, M. M. et al. A case study on thermo-hydraulic performance of jet plate solar air heater using response surface methodology. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 34, 101983 (2022).

Singh, A. K., Kumar, S. & Singh, K. Experimental and numerical study on the combined jet impingement and film cooling of an Aero-Engine afterburner section. Aerospace. 10 (7), 589 (2023).

Lim, H. D., New, T., Mariani, R. & Cui, Y. Effects of bevelled nozzles on standoff impingements in supersonic impinging jets. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 94, 105371 (2019).

Li, W. et al. Air-impingement jet drying at high temperature and air velocity enhanced the dehydration efficiency, Quercetin content, and antiradical properties of Fig slices. Int. Food Res. J. 29 (4), 947–958 (2022).

Li, J. et al. Optimal design to control rotor shaft vibrations and thermal management on a supercritical CO2 microturbine. Mech. Ind. 22, 22 (2021).

Arthurs, D. & Ziada, S. Effect of nozzle thickness on the self-excited impinging planar jet. J. Fluids Struct. 44, 1–16 (2014).

Cui, Y. F., Xu, J. Y., Zhan, K. J., Cui, F. L. & Hong, F. J. Bubble dynamics and pressure Oscillation in highly subcooled water jet array impingement boiling under periodical heat flux. Int. Commun. Heat Mass Transf. 126, 105476 (2021).

Eman Desoky, M. & Kamel, A. K. Primary, super harmonic and subharmonic resonances control of an oscillatory cantilever beam excited transversely at its free end. Afrika Matematika. 36–91 (2025).

Cui, J., Zhang, W., Liu, Z. & Sun, J. On the limit cycles, period-doubling, and quasi-periodic solutions of the forced Van der Pol-Duffing oscillator. Numer. Algorithms. 78, 1217–1231 (2018).

Kundu, P. K. & Chatterjee, S. Nonlinear feedback synthesis and control of periodic, quasiperiodic, chaotic and hyper-chaotic oscillations in mechanical systems. Nonlinear Dyn. 111 (12), 11559–11591 (2023).

Shukla, A. K., Ramamohan, T. R. & Srinivas, S. A new analytical approach for limit cycles and quasi-periodic solutions of nonlinear oscillators: the example of the forced Van der pol duffing oscillator. Phys. Scr. 89(7), 075202 (2014).

Acknowledgements

We thank LetPub (https://www.letpub.com) for its linguistic assistance during the preparation of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

X.M.Z. wrote the main manuscript text and G.J.Z. prepared Figs. 1, 2 and 3. X.L. and H.W. did the numerical caculation and completed the revision and the responses of the manuscript. H.W. is also the funder of this study. All of the authors reviewed and confirm the revisied manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, X., Li, X., Wang, H. et al. Development mechanism and parameter control of jet impingement based on chaotic modulation. Sci Rep 15, 28163 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-12841-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-12841-7