Abstract

Existing sparse decomposition techniques often rely on over-complete dictionaries and extensive prior knowledge, leading to slow computation and low efficiency. This paper introduces a novel sparse decomposition method, Adaptive Evolutionary Atomic Sparse Decomposition (AEA-SD). A general atom (g-atom) is designed to accommodate various typical signals, accompanied by an adaptive atom-based automatic target signal localization algorithm. To accelerate convergence, a fast sparse decomposition method based on Bat algorithm is developed, which eliminates the reliance on redundant dictionaries. The performance of AEA-SD is verified by using magnetotelluric (MT) data. Experimental results demonstrate that AEA-SD reduces CPU usage by over 30% compared to traditional algorithms and enhances signal extraction accuracy by at least 58%, 46%, and 58% in low, middle, and high frequency bands, respectively. Furthermore, the method’s adaptability makes it applicable to diverse scenarios requiring the removal of complex background noise from sensor signals.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Nonstationary signals are very common in nature1but cannot be accurately described by the Fourier transform2. In recent years, new theories and technologies for signal extraction and sparse decomposition have continued to appear, including Wavelet Decomposition (WD)3, fast overcomplete sparse decomposition4, Hilbert–Huang Transform (HHT)5, Variational Mode Decomposition (VMD)6 and deep neural networks7. In these methods, WD and HHT are the most popular methods. However, the computational efficiency of the aforementioned method is significantly reduced in complex background noise environments, leading to increased debugging costs. In complex noise environments, the efficiency of WD is higher than that of HHT and VMD. The decomposition performance of WD is strongly dependent on the selection of basis functions. HHT requires integration with a pre-decomposition method to enhance its noise resistance but incurs high computational costs. VMD exhibits relatively strong anti-noise performance; however, it necessitates combination with intelligent optimization algorithms to improve its adaptability.

Due to the excellent performance in feature signal extraction and low debugging cost, sparse decomposition has become a popular method for weak signal extraction8. In recent years, researchers have investigated sparse decomposition algorithms for images and developed sparse decomposition methods based on neural networks. These advancements have significantly enhanced the efficiency of image target recognition and classification9. However, while the sparse decomposition method based on deep learning improves the computational efficiency, its training process is not very stable and requires a relatively complex optimization process. Furthermore, in the domain of one-dimensional signal processing, there remains substantial potential for further exploration. Wang et al. combined sparrow search algorithm (SSA) with VMD to propose a signal sparse decomposition method that provides a basis for feature extraction. In this method, SSA can adaptively provide VMD modal parameters and has a strong anti-interference ability. However, the optimization results of SSA are closely related to the initial parameter settings, and there is a risk of over-decomposition10. Li et al. designed a two-channel tunable Q-factor wavelet transform (TQWT) method to extract adaptive atoms, constructed an adaptive complete dictionary, and used the Orthogonal Matching Pursuit (OMP) algorithm to obtain sparse signals, which improved the adaptability of the algorithm. In this method, the parameter optimization and adaptive dictionary construction process of the dual-channel TQWT provide higher decomposition degrees of freedom and matching ability. However, this algorithm has high requirements for computing devices, and the recognition performance of various types of fault signals still needs to be improved11. To address the limitations of traditional noise reduction methods in preserving signal features and resisting strong noise interference, Zheng et al. proposed a novel re-weighted group sparse decomposition method, which integrates group sparse theory in the frequency domain with time-domain fault characterization via two newly defined metrics—cyclic re-weighted kurtosis and re-weighted cyclic intensity (RWCI)—to enhance features of weak signals adaptively12. However, the above-mentioned sparse decomposition methods have a high dependence on prior knowledge, such as over-complete dictionaries, the number of decomposition layers, and the selection of cost functions, etc.

To enhance the decomposition speed and extraction accuracy of nonstationary signals, a general atom, g-atom is designed, and an improved matching and extraction algorithm based on sparse decomposition is proposed. A parameter initialization method in the g-atom time-frequency domain, utilizing correlation detection and envelope detection, is developed to adaptively simulate various types of noise and achieve automatic segmentation of target signals. Additionally, a sparse decomposition method based on the Bat algorithm is introduced to accelerate convergence, eliminating the reliance on redundant dictionaries inherent in traditional sparse decomposition approaches. These innovations significantly improve the efficiency and precision of nonstationary signal extraction. The performance of the proposed method is verified by magnetotelluric (MT) data. Figure 1 shows the typical MT signal, as can be seen, it has characteristics of nonstationary, weak amplitude and wide frequency band. These factors make it susceptible to strong human noise, such as power line interference, motor noise, etc.

Experimental results demonstrate that the proposed AEA-SD method outperforms current mainstream solutions by reducing CPU usage by at least 31% while achieving significant improvements in signal extraction accuracy—by at least 58%, 46%, and 58% for low, medium, and high-frequency signals, respectively. When applied to wild field measurement signals, detailed data analysis confirms the algorithm’s effectiveness in eliminating complex background noise, highlighting its practical applicability and robustness.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows: “Methods” details the implementation of the proposed algorithm. “Simulation experiments” presents simulation and experimental results using measured data, demonstrating the advantages of the proposed method. Finally, “Conclusion” concludes the study with a summary of key findings and application scenarios of proposed method.

Methods

Adaptive construction of feature-based atoms

Sparse decomposition has emerged as a promising approach to attain a more adaptable and succinct signal decomposition. This method aims to represent the signal with minimal atoms from a predetermined redundant dictionary through the Matching Pursuit (MP) algorithm13. Using novel evaluation on criteria and basis pursuit, OMP algorithm14 and time-frequency spectrum segmentation methods15 are also belonged to over-complete dictionary-based methods.

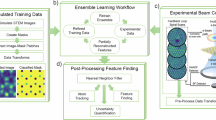

As mentioned above, sparse decomposition usually requires an over-complete dictionary to be constructed in advance16. This immutable dictionary cannot effectively describe complex and changeable signals due to its insufficient flexibility17. Researchers have proposed adaptive learning methods to train the dictionary, for example, the Focal Undetermined System Solver18, the Method of Optimal Directions19, the low-rank decomposition20, and the genetic algorithm optimized resonance-based signal sparse decomposition21. These algorithms rely heavily on reasonable default parameters, resulting in high computational complexity, insufficient adaptation and not suitable for one-dimensional signal processing. In this work, based on the analysis of different interference signals, a redundant atom dictionary is constructed to reproduce the noise. Then the matching pursuit algorithm optimized by the bat algorithm is used to optimize the parameters to achieve effective signal extraction. The overall algorithm process is shown in Fig. 2.

The method proposed in this paper consists of two parts: general atom construction and adaptive evolution. The general atom construction part includes the construction principle of general atom that match various typical noises, as well as the initialization method of the target signal location algorithm based on correlation detection and envelope analysis. The adaptive evolution section introduces the signal adaptive sparse decomposition algorithm based on the redundant atom dictionary and the general atom adaptive matching evolutionary algorithm, which improves the matching efficiency of general atom for the target signal.

General atom for typical interference signals

When utilizing sensors for measurements, the nonstationary signals obtained are readily influenced by intricate noise factors, this paper designed a general atom to simulate the interferences, denoted as the “g-atom”, which is formulated as follows:

where t is the sampling time; d1 and d2 are the bilateral attenuation factors, when their values increase, it will lead to an increase in the signal attenuation rate; τ1 and τ2 are bilateral effective oscillation times, determine the effective interval lengths of the curve on the left and right sides of t0; t0 is the bilateral demarcation time, determines the position of the curve relative to the origin point; f is the frequency; Φ is the phase; and ε is the bilateral scaling coefficient, which is used to control the amplitude of the curve in the right interval of t0, typically ε = 1. Figure 3 illustrates the time domain waveform of the g-atom when the parameters are altered.

When d1 = d2 = 0 and ε = 1, the g-atom exhibits behavior consistent with a standard sine wave (Fig. 3a); when ε = 1, τ1 = τ2 ≠ 0, and d increases, the g-atom behaves as a bilateral oscillating decay signal, which match the characteristics of spike discharge signals, and show sinusoidal damping oscillations at high frequencies (Fig. 3b,h). Low-frequency g-atom behaves as a triangle-like wave (Fig. 3f); when τ2 = 0, the g-atom shows characteristics of stimulated oscillation (Fig. 3c,d); when τ1 = 0, the g-atom shows characteristics of unilateral damped oscillation (Fig. 3g); and when ε between 0 and 1, f is low enough, the g atom exhibits a charge-discharge triangular wave (Fig. 3e).

The aforementioned analysis indicates that the proposed g-atoms are very flexible, and can be made to closely match typical testing signals by parameter adjustment. The parameter acquisition methods for g-atom parameters are described as follows.

Target data location and segmentation algorithm

In this paper, time domain parameters of g-atom are initialized by segmentation method based on correlation detection technology. A coherent delay signal detection model was constructed by using the envelopes and peak gradients of the cross-correlation function as eigenvalues to fragment the target signals automatically.

Let the original sampling sequence x(t) be composed of two parts, x(t) = xn(t) + s0(t), where xn(t) represents a nonstationary signal and s0(t) is the target signal in x(t), leads to the following expression:

where Ai, fi, and Φi are the amplitude, frequency, and phase of the main frequency component of the target signal respectively, and [ti1 ti2] is the occurrence period of the target signal, which satisfies ti1<ti2<T (T is the total sampling time).

Since the target signals are unknown, the standard sinusoidal atom \({\overset{\lower0.5em\hbox{$\smash{\scriptscriptstyle\frown}$}}{s} _i}\left( t \right)\) is constructed firstly, the estimated parameters \(\left[ {\begin{array}{*{20}{c}} {{{\overset{\lower0.5em\hbox{$\smash{\scriptscriptstyle\frown}$}}{A} }_i}}&{{{\overset{\lower0.5em\hbox{$\smash{\scriptscriptstyle\frown}$}}{f} }_i}}&{{{\overset{\lower0.5em\hbox{$\smash{\scriptscriptstyle\frown}$}}{\phi } }_i}} \end{array}} \right]\) of the target signals in x(t) are preliminarily determined by STFT, then \({\overset{\lower0.5em\hbox{$\smash{\scriptscriptstyle\frown}$}}{s} _i}\left( t \right)=\sin \left( {2\pi {{\overset{\lower0.5em\hbox{$\smash{\scriptscriptstyle\frown}$}}{f} }_i}t+{{\overset{\lower0.5em\hbox{$\smash{\scriptscriptstyle\frown}$}}{\phi } }_i}} \right),0 \leqslant t \leqslant fs/{f_i}\) .

Cross-correlation function is applied to determine the time when the target sine wave s0i appears in sequence x(t). According to the definition, the cross-correlation function between x(t) and \({\overset{\lower0.5em\hbox{$\smash{\scriptscriptstyle\frown}$}}{s} _i}\left( t \right)\) is:

where ‘*’ means convolution, xn is the nonstationary component and is uncorrelated with \({\overset{\lower0.5em\hbox{$\smash{\scriptscriptstyle\frown}$}}{s} _i}\left( t \right)\); \(\tilde {s}\) is the signal component with weak correlation with \({\overset{\lower0.5em\hbox{$\smash{\scriptscriptstyle\frown}$}}{s} _i}\left( t \right)\). Therefore, the first term of Eq. (3) is approximately 0, leading to:

According to Eq. (4), the envelope period of \({R_{x{{\overset{\lower0.5em\hbox{$\smash{\scriptscriptstyle\frown}$}}{s} }_i}}}(t)\) is [− t1−1, t2 + 1].

The above is the principle of correlation detection and positioning algorithm, the calculation process is shown in Fig. 4.

In measurement procedure, since the first term in Eq. (3) is not absolutely equal to 0, the maximum peak gradient is used as the characteristic parameter, and the envelope gradient \(\Delta\)p of the cross-correlation function is:

where Penv(i) represents the i-th point value of the envelope, and the maximum peak gradient of the cross-correlation function appears at i = L1.

The soft threshold method is employed to extract the cross-correlation envelope, with the optimal envelope range determined using Eq. (6):

In Eq. (6), \(A_{{thr{e_s}}}^{+}\) and \(A_{{thr{e_s}}}^{ - }\) are the soft thresholds of the upper and lower effective envelopes respectively; λ is related to the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR), \(\lambda \in \left( {0,1} \right)\), when the SNR is smaller, x tends more towards 1; [lp1 lp2] and [ln1 ln2] are respectively the upper and lower effective envelope window ranges. The target signal data segment range is defined as specified in Eq. (7):

In Eq. (7), nshift is the offset factor, \(\left\lfloor {} \right\rfloor\) means to round down, [l1 l2] is the boundary of the effective envelope window. The maximum values are employed to ensure the complete extraction of the target signal segment.

Therefore, the initial position L0 and the length L of the target signal s0i in sequence x can be preliminarily determined by using the above correlation detection and positioning algorithm, so that the interference sample Ei(t) of original observation sequence can be obtained.

Parameter initialization algorithm for g-atom

In this stage, apply Hilbert transform to interference sample Ei(t) in original sequence x(t) can obtain more accurate interference component parameter and provide frequency domain parameters for g-atoms.

h(t) is a shock response.

Then construct the following parsing signal Z(t):

The instant frequency of Ei(t) is calculated by Eq. (10):

ϕ(t) is the phase function:

The time parameters are determined by the maximum Amax and the two adjacent sub-maxima (\(\begin{array}{*{20}{c}} {A_{{{{\hbox{max} }^ - }}}^{l}}&{A_{{{{\hbox{max} }^ - }}}^{r}} \end{array}\)), among them, \(A_{{{{\hbox{max} }^ - }}}^{l} \ll A_{{{{\hbox{max} }^ - }}}^{r}\) represents unilateral attenuation oscillation, \(A_{{{{\hbox{max} }^ - }}}^{l} \gg A_{{{{\hbox{max} }^ - }}}^{r}\) represents unilateral excited oscillation, and \(A_{{{{\hbox{max} }^ - }}}^{l} \approx A_{{{{\hbox{max} }^ - }}}^{r}\) represents bilateral oscillation:

In which fs is the sampling rate, L2 = L + L1. According to Eq. (12), the attenuation factors d1 and d2 are determined by the log ratios of Amax and \(\begin{array}{*{20}{c}} {A_{{{{\hbox{max} }^ - }}}^{l}}&{,A_{{{{\hbox{max} }^ - }}}^{r}} \end{array}\), and ε is determined by the ratio of \(A_{{{{\hbox{max} }^ - }}}^{l}\) and \(A_{{{{\hbox{max} }^ - }}}^{r}\).

Finally, the general atom was obtained with the frequency parameters f, ϕ, d1, d2 and time information t0, τ1, τ2, ε, \(par{a^0}=\left[ {\begin{array}{*{20}{c}} f&\phi &{\begin{array}{*{20}{c}} {{d_1}}&{{d_2}} \end{array}}&{t_{0}^{{}}}&{\tau _{1}^{{}}}&{\tau _{2}^{{}}}&\varepsilon \end{array}} \right]\) as the reference.

The target signal positioning algorithm based on correlation detection method is shown in Fig. 5.

Adaptive evolutionary algorithm-based sparse decomposition

Signal can be represented by sparse decomposition by a specific combination of certain atoms in the dictionary22. If all possible combinations are calculated, the optimal combination would be obtained precisely. Exhausting all possible combinations in a huge dictionary is nearly impossible. Instead, a suboptimal solution can be obtained by identifying the combination with the fewest atoms and the smallest extraction error. This approach significantly reduces computational complexity, prompting the use of the matching pursuit (MP) algorithm to achieve this goal.

Set the length of signal x(t) to N. The matrix D consists of a set of vectors \(\{ {g_1},{g_2}, \ldots ,{g_n}\}\) in Hilbert space \(\mathbb{\Gamma}\). Each vector represents a normalized atom of length N, the normalized result is \(\left\| g \right\|_{2}^{2}=1\).

Let the 0-th residual ξ0 = x, the MP algorithm selects an atom that best matches x from the dictionary matrix D each time, satisfying Eq. (13):

ibest denotes the index of the optimal atom in D.

Next, x is decomposed into a sparse approximation \(\overset{\lower0.5em\hbox{$\smash{\scriptscriptstyle\frown}$}}{x}\) and a residual ξ2:

The algorithm iteratively selects the optimal atom for ξ2, continuing until x is approximately represented as the sum of the selected atoms:

The MP-based algorithms cannot obtain the best results at one time and requires multiple iterations to converge for its non-orthogonality. Take OMP algorithm as an example, it orthogonalizes all selected atoms at each iteration23. While the OMP algorithm reduces the number of iterations, each iteration requires calculating the inner product between the current residual and all atoms in the dictionary, leading to suboptimal performance.

Adaptive evolutionary algorithm of matched g-atoms

To enhance system performance, the Bat Algorithm (BA) is utilized to train the g-atom for matching the target signal. Leveraging its unique search mechanism and adaptability, the BA transforms the process into a global optimization problem, effectively eliminating the need for a massive redundant dictionary and addressing the high computational cost and inefficiencies of traditional MP-based algorithms. Compared with methods such as Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) and Genetic Algorithm (GA), this method has better convergence and accuracy in dealing with nonlinear and multimodal problems. Compared with GA, the number of its parameters is relatively small, and the parameter adjustment of BA is relatively easy. In practical applications, the appropriate parameter combination can be determined more quickly according to the characteristics of the problem, thereby reducing the time cost of algorithm debugging. And during the search process, the relationship between the optimization of the objective function and the satisfaction of constraint conditions can be well balanced. Furthermore, when the objective function or constraint conditions of the optimization problem change over time, BA can quickly adjust its search strategy and track the new optimal solution. The new method is called AEA-SD described in Table 1:

Some parameters in initialization part are shown below:

-

①

Nite: maximum number of iterations, Nite=50;

-

②

σ: optimal threshold, depends on the ℓ-2 norm of the original segment signals;

-

③

n: current iteration, starting from 0;

-

④

ξn: residual of the n-th iteration, ξ0 = x;

-

⑤

Fitnbest: best fitness of the n-th iteration, Fit0best = 1e6;

-

⑥

Pba: initial parameter vector for adaptive evolutionary algorithm on the matched atom. In this study, Npop=30, Ngen=50, R=1.2, f0=0.8, A0=0.8, r0=0.8 Pnj.

In the output section, the system ends up giving three parameters: the sparse signal s = x-ξn, the matched dictionary \(D=\left[ {\begin{array}{*{20}{c}} {g_{{best}}^{1}}&{g_{{best}}^{2}}&{...}&{g_{{best}}^{n}} \end{array}} \right]\), and the corresponding decomposition coefficients \(A=\left[ {\begin{array}{*{20}{c}} {a_{{best}}^{1}}&{a_{{best}}^{2}}&{...}&{a_{{best}}^{n}} \end{array}} \right]\).

In this case, some key parameters of the adaptive evolutionary algorithm based on BA are described as follows:

-

(1)

Parameter initialization Pba = [Npop Ngen R m ξn q f0 A0 r0 Pnj]:

-

①

Npop: bat population, it increases as the search space expands.

-

②

Ngen: the largest generation.

-

③

R: redundancy, ensures the diversity of parameters.

-

④

m: current iteration, m = 1.

-

⑤

ξn: residual of the n-th generation and ξ0 = x.

-

⑥

q: search space dimension (q = 8).

-

⑦

f0: frequency coefficient, \({f_0}=\{ {f_i}^{0}|i=1,2, \ldots ,q\}\)

-

⑧

A0: acoustic loudness \({A_0}=\{ {A_i}^{0}|i=1,2, \ldots ,q\}\), the threshold for accepting inferior solutions.

-

⑨

r0: pulse emission frequency, \({r_0}=\{ r_{i}^{0}|i=1,2, \ldots ,q\}\), control the global search capability.

-

⑩

\(P_{j}^{{{n_m}}}\): location of the j-th bat in the n-th generation.

-

①

The initial location of the bat colony is randomly generated by Eq. (19):

where λj is the random number between − 1 and 1, obey Gaussian distribution simultaneously.

-

(2)

Create Npop real-time flexible atoms \(g_{j}^{{{n_m}}}\) according to the bat group position \(P_{j}^{{{n_m}}}\):

-

(3)

Update the residual:

where \(c_{j}^{{{n_m}}}\) is the normalization coefficient of atom \(g_{j}^{{{n_m}}}\), \(\left\| {c_{j}^{{{n_m}}} * g_{j}^{{{n_m}}}} \right\|=1\), and \(a_{j}^{{{n_m}}}\) is the corresponding decomposition coefficient.

-

(4)

Determine the best matching atom \(g_{{best}}^{{{n_m}}}\) using the fitness function. This paper takes the ℓ-2 norm of the residual \(\xi _{{n+1}}^{{}}\) as the fitness function to improve the conventional fitness function in sparse decomposition, leads to:

A smaller fitness indicates that the effective signal component in the residual sequence is smaller, and the signal-to-noise separation is higher. Therefore, the current global optimal individual bat position \(P_{{best}}^{{{n_m}}}\) and \(g_{{best}}^{{{n_m}}}\) are determined and saved according to Eq. (23):

-

(5)

Update the velocity and position of the individual bat:

where r1 is a random number between 0 and 1; fj, \(v_{j}^{{{n_{m+1}}}}\) and \(P_{j}^{{{n_m}}}\) is the search frequency, velocity and position of j-th bat respectively; the superscript represents the n-th generation at m-th and (m + 1)-th iteration respectively.

-

(6)

Randomly generate a number r2j between 0 and 1 for each bat, then update the bat position by Eq. (25):

where λrj is a random number satisfying λrj∈ [− 0.3 0.3] and Ānm is the mean loudness of the bat population. \(P_{j}^{{{n_m}}}\) and \(P_{j}^{{{n_{m+1}}}}\) denote the positions of the j-th bat at the m-th and (m + 1)-th iterations.

-

(7)

Update the fitness function:

-

(8)

Add a random disturbance r3j to each bat and update their position:

-

(9)

Update the fitness and the pulse emission frequency by Eq. (28):

where λ ∈ (0,1), γ > 0, when \(n \to \infty\), \(A_{j}^{{{n_m}}} \to 0\), \(r_{j}^{{{n_m}}} \to {r_0}\).

-

(10)

Find the current matching atom based on the location of the optimal bat individual by Eq. (23).

-

(11)

Determine whether the algorithm satisfies the iteration termination condition and execute step (5) if not.

The random perturbation probability r2j and r3j of the ideal position of the bats in step (6) and (8) can effectively avoid the iterative result becomes a local optimal solution24which helps to find the global optimal solution fast. For easy comprehension, the overall flowchart of AEA-SD is shown in Fig. 6.

In the experimental section, the root mean square error (RMSE) and the mean absolute error (MAE) will be used to evaluate the effect of signal decomposition. Their calculation formulas are as follows:

In which n represents sample number, yi represents the true value of i-th sample, xi represents the processed value of i-th sample.

Simulation experiments

To validate the performance of the proposed method, a nonstationary signal xi was constructed, featuring a sampling rate of 1200 Hz and a duration of 10 s. The signal is defined as x = s + ns, where s represents the nonstationary target signal located at random positions, and ns is background noise following a Gaussian distribution. For a comprehensive evaluation and discussion, six common target signals widely used in MT methods were selected for comparative experiments.

Take s1 and s5 as examples, the segmentation results are shown in Fig. 7. In Fig. 7, L1 and L2 denote start and end points of the target segments, L denotes the segmentation length. The length of ŝ1 and ŝ5, are 3.01s and 4.38 s respectively, the target signals were well segmented.

The effectiveness of the proposed segmentation method was evaluated using simulated signals with varying signal-to-noise ratios (SNRs) and frequencies, as shown in Fig. 8. Figure 8a reveals that segmentation accuracy improves with increasing SNRs across four signal types. For square and Dirichlet signals, accuracy approaches 100% when the SNR exceeds − 10 dB, while pulse and oscillation signals achieve over 70% accuracy at SNRs above 2 dB. Figure 8b indicates that signal frequency has minimal influence on the segmentation accuracy of square signals, except at very low frequencies where reduced correlation intensity leads to significant accuracy decline. Overall, the method demonstrates robust segmentation performance, provided the signal frequency is not excessively low and the signal is not entirely masked by background noise.

In Sparse decomposition validation part, using SD based on MP25, OMP26, CoSaMP27 and Sparsity Adaptive MP (SAMP)28 with fixed redundant dictionary were introduced to verify the validation of AEA-SD. For each method, the preset parameters were all the same for the six signals. The same redundant dictionary D with size of 701,136*1200 was built using Gabor atoms by parameter discretization.

To balance computing speed and accuracy, the data length per column of the dictionary D was set equal to the sampling frequency (fs) rather than the full signal length, to prevent excessive memory consumption and ensure compatibility with standard computing resources.

Before the experiments, the target segmentation was extended to both sides to obtain the sequence to be proposed \({\tilde {x}_i}\left( {1 \times {L_n}} \right)={x_i}\left( {L_{1}^{\prime }:L_{2}^{\prime }} \right)={x_i}\left( {L_{1}^{{}}-\Delta {l_1}:L_{2}^{{}}+\Delta {l_2}} \right)\), where Ln=kd*fs and kd is an integer. During the sparse decomposition, \({\tilde {x}_i}\) was divide into kd sections \({\tilde {x}_i}^{j},j=1,2,...,{k_d}\) and the above SP methods were conducted to \({\tilde {x}_i}^{j}\) and obtained \({\overset{\lower0.5em\hbox{$\smash{\scriptscriptstyle\frown}$}}{s} _i}^{j}\). Finally, the extracted signals were gained by:

For AEA-SD, the original sequence xi was proposed as a whole based on the parameters obtained above. The key parameters were set as follows:

Figure 9 shows the evolutionary process of the first generation. The volumes of the blue balls represent the fitness values, with smaller being better. The parameters keep moving towards the actual values trained by the adaptive evolutionary algorithm. During optimization, the fitness decreases, and the location marked by the red ball represents the optimal solution.

The signal extraction results obtained by the 5 methods were shown in Fig. 10. Panel (a) displayed the extracted signals and the target signal and panel (b) showed corresponding deviation curves.

As shown in Fig. 10, the efficiency and extraction quality of each method varied across different signal types. For square and triangular signals, under-decomposition issues were observed with the MP and OMP methods, indicating their limitations in effectively handling signals with complex spectra. In contrast, the SAMP method exhibited over-decomposition for dual-frequency and Plustran signals due to its requirement to select a fixed number of atoms in each iteration.

The CoSaMP method performed well only for Dirichlet signals, while showing significant errors for other signal types. This limitation stems from the preset signal sparse value, which lacks adaptability to diverse target signals. Although improved results might be achievable through extensive parameter optimization, such trial-and-error processes are computationally intensive and impractical for large-scale data processing.

A quantitative analysis of the experimental results is shown in Table 2; Fig. 11.

Table 2; Fig. 11a reveal that the matching pursuit time for AEA-SD was moderate among the tested methods. However, the total elapsed time for the first four methods was significantly longer due to the extensive dictionary building process. The proposed method demonstrates a clear improvement in efficiency by eliminating redundant dictionary construction. Additionally, as shown in Fig. 11b, AEA-SD achieved results closer to the ideal, evidenced by its minimal variance.

Simulation data analysis

In this part, the MT measured data is used to verify the performance of AEA-SD, MT signals are affected by electromagnetic interference from various sources. These interferences are not isolated phenomena but occur as a superposition of multiple sources. During simulations, such typical interference signals are modeled as background noise to accurately represent real-world conditions.

The signal shown in Fig. 12 represents a superimposed interference signal with a sampling rate of 24,000 Hz and a duration of 10 s. The simulation results are presented in Fig. 12. Panel (a) illustrates the time-domain waveforms of the original simulation signal and the self-intercepted signal. Panel (b) shows the time-domain waveform of the processed signal. Panel (c) depicts the evolution of the bat population in three dimensions during the optimization process of the Bat algorithm, with the ball diameter indicating the degree of adaptation. Finally, Panel (d) presents the frequency-domain curves of both the original signal and the residual signal.

Measured data experiment

In order to verify the performance of the method described in this study, the field measurement data of V8 MT system developed by Phoenix Company in Canada are used for testing experiments. The system consists of a transmitter, a receiver, two transmitting electrodes and six measuring electrodes. The measurement system is shown in Fig. 13. The main sources of interference are power frequency interference near the test site, signal tower interference, vehicle noise, etc.

During the experiment, the field measured data in the frequency band range of 0.01 ~ 9600 Hz is processed. The results are shown in Fig. 14, in which four curves are respectively two-channel orthogonal electric field data (Ex, Ey) and two-channel orthogonal magnetic field data (Hx, Hy).

It can be seen that the long-period square wave, triangular wave, pulse interference, sinusoidal interference and other interference signals in the original data can be effectively removed by AEA-SD.

The comparative processing results of MT measured data are presented in Fig. 15. Among them, the AEA-SD demonstrated the best performance. The apparent resistivity curve in the YX direction, obtained using the MP algorithm, exhibited a significant downward trend in the low-frequency band. However, after interference removal with the AEA-SD algorithm, this downward trend was effectively suppressed. Additionally, the MP algorithm introduced noticeable distortions in the apparent resistivity curve within the 1–10 Hz bandwidth. In contrast, the AEA-SD algorithm produced a smoother, more continuous resistivity curve with relatively stable values. Furthermore, in the high-frequency band above 1 kHz, the apparent resistivity curve in the XY direction processed by the MP algorithm showed a marked decline, which was significantly improved by the AEA-SD algorithm.

In the realm of MT measurement, error analysis is employed to quantitatively validate the performance of the proposed algorithm since there is no precise value for comparison. In this paper, the average errors of low frequency band (10− 3 Hz ~ 100 Hz), medium frequency band (100 Hz ~ 102 Hz), and high frequency band (102 Hz ~ 104 Hz) of the apparent resistivity data processed by the three methods are analyzed respectively, including ROHxy and ROHyx directions. The results are shown in Table 3.

The above experimental results show that the method described in this study effectively removed most kinds of typical largescale interferences in the measured data of the MT method, and at the same time preserve the useful information. The downward trend of the apparent resistivity curve in the low and high frequency bands was effectively suppressed, the distortion part was effectively improved, and the overall shape of the curve was more stable.

Owing to the superior signal decomposition capability and robustness of the VMD algorithm, researchers have focused on optimizing VMD for signal analysis in recent years, among which the PSO algorithm has been one of the most widely adopted approaches29,30. To verify the signal decomposition ability of the proposed method in other scenarios, the data collected on the turntable using the ADXRS649 gyroscope were processed. In this experiment, the noise mainly consists of the null bias and random walk of the gyroscope, presented in the form of Gaussian noise, and the relatively weak power supply noise, presented in the form of transient interference. The experimental equipment is shown in Fig. 16. For comparison, the non-sparse decomposition method PSO-VMD was introduced. The gyroscope signals with diagonal rates of 60 degrees per second and 90 degrees per second were processed using the AEA-SD and PSO-VMD algorithms respectively, and the results are shown in Table 4; Fig. 17.

It can be seen from Table 4 that AEA-SD has the smallest root mean square error, proving that this method has good performance in other signal decomposition fields. From Fig. 17, it can be seen that the signal processed by the AEA-SD algorithm is the closest to the theoretical value, and has fewer jumps compared with the PSO-VMD algorithm, and has better stability experience in the time domain. Compared with the measured data, it has less noise and a smoother waveform.

Conclusion

This paper proposes an innovative sparse decomposition method, AEA-SD, which incorporates a general g-atom and a novel time-frequency domain parameter initialization approach based on correlation and envelope detection. This method effectively adapts to complex noise present in measurement signals. Additionally, an adaptive sparse decomposition method is proposed, which eliminates the need for large redundant dictionaries. The method efficiently extracts nonstationary signals from background noise without conventional redundant dictionary, while preserving the target signal components. The proposed method significantly enhances algorithm convergence speed and reduces hardware requirements, offering a robust solution for signal extraction in noisy environments.

Through simulation experiments, the proposed AEA-SD method demonstrates a significant reduction in computing resource usage and CPU utilization. Compared with the traditional sparse decomposition algorithms and optimized methods such as BatOMP algorithm, it improves by at least 31% and 58% respectively, make it possible to process data on mobile computers with poor performance (without high-performance GPUs and high-power power supplies), rather than high-performance workstations. In addition, AEA-SD delivers enhanced decomposition accuracy within similar computational times, in the case of the Gabor dictionary, when processing the same signal, the accuracy of AEA-SD has improved by 47% compared to the BatOMP algorithm.

The measured data experiment results demonstrate that the data curves obtained using the AEA-SD method are significantly smoother, indicating its strong robustness, particularly in high-frequency data processing. The analysis reveals that AEA-SD improves extraction accuracy by 58%, 46%, and 58% for low, medium, and high-frequency signals, respectively. Moreover, the adaptability of AEA-SD makes it a powerful tool for data analysis in various fields, particularly in environments with strong interference, offering significant potential for broader applications. Experiment shows that in the process of gyroscope measurement signals, the signal extraction accuracy of the proposed method has increased by 41.05% and 38.66% compared with other methods.

Data availability

The datasets used and analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Zhang, C. X. et al. Precise calibration of projectile-borne MEMS gyroscopes based on the EWMA-DD method. IEEE Sens. J. 24, 32321–32333. https://doi.org/10.1109/jsen.2024.3453893 (2024).

Li, X. L., Wang, N., Gao, D. Z. & Li, Q. A sound field separation and reconstruction technique based on reciprocity theorem and fourier transform. Chin. Phys. Lett. 35, 114301 (2018).

Wolf, G., Mallat, S. & Shamma, S. Rigid motion model for audio source separation. IEEE Trans. Signal Process. 64, 1822–1831 (2015).

Mohimani, H., Babaie-Zadeh, M. & Jutten, C. A fast approach for overcomplete sparse decomposition based on smoothed $\ell ^{0}$ norm. IEEE Trans. Signal Process. 57, 289–301. https://doi.org/10.1109/TSP.2008.2007606 (2009).

Huang, N. E. In Hilbert–Huang Transform and its Applications, 1–26 (World Scientific, 2014).

Eriksen, T. & Rehman, N. Data-driven nonstationary signal decomposition approaches: a comparative analysis. Sci. Rep. 13, 1798. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-28390-w (2023).

Song, Q. et al. A deep learning method based on multi-scale fusion for noise-resistant coal-gangue recognition. Sci. Rep. 15, 101. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-83604-z (2025).

Ge, S. & Zhou, S. Nonstationary signal extraction based on BatOMP sparse decomposition technique. Sci. Rep. 11, 17869. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-97431-z (2021).

Alonso-Monsalve, S. et al. Deep-learning-based decomposition of overlapping-sparse images: application at the vertex of simulated neutrino interactions. Commun. Phys. 7, 173. https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-024-01669-8 (2024).

Wang, X. et al. Fault diagnosis method of rolling bearing based on SSA-VMD and RCMDE. Sci. Rep. 14, 30637. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-81262-9 (2024).

Li, J., Wang, H. & Song, L. A novel sparse feature extraction method based on sparse signal via dual-channel self-adaptive TQWT. Chin. J. Aeronaut. 34, 157–169. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cja.2020.06.013 (2021).

Zheng, X., Cheng, J., Nie, Y. & Yang, Y. A new noise reduction method based on re-weighted group sparse decomposition and its application in gear fault feature detection. Meas. Sci. Technol. 34, 095022 (2023).

Dymarski, P., Moreau, N. & Richard, G. Greedy sparse decompositions: a comparative study. EURASIP J. Adv. Signal Process. 2011, 1–16 (2011).

Wen, H. et al. Exploiting high-quality reconstruction image encryption strategy by optimized orthogonal compressive sensing. Sci. Rep. 14, 8805. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-59277-z (2024).

Yan, B., Wang, B., Zhou, F., Li, W. & Xu, B. Sparse decomposition method based on time–frequency spectrum segmentation for fault signals in rotating machinery. ISA Trans. 83, 142–153 (2018).

Zhu, J. & xiaolu, L. Electrocardiograph signal denoising based on sparse decomposition. Healthc. Technol. Lett. 4, 134–137 (2017).

Hu, J., Niu, K., Wang, Y., Zhang, Y. & Liu, X. Research on deep unfolding network reconstruction method based on scalable sampling of transient signals. Sci. Rep. 14, 27733. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-79466-0 (2024).

Majumdar & A. %J signal processing letters, I. FOCUSS based Schatten-p norm minimization for Real-Time reconstruction of dynamic contrast enhanced MRI. 19, 315–318 (2012).

Hosseini, M. & Riahi, M. A. Using input-adaptive dictionaries trained by the method O. O.timal directions to estimate the permeability model O. a reservoir. 165, 16–28 (2019).

Xu, C. Spectral weighted sparse unmixing based on adaptive total variation and low-rank constraints. Sci. Rep. 14, 23705. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-70395-6 (2024).

Li, Q. & Liang, S. Y. Weak crack detection for gearbox using sparse denoising and decomposition method. IEEE Sens. J. 19, 2243–2253. https://doi.org/10.1109/JSEN.2018.2884227 (2019).

Niu, Y. & Wang, B. Hyperspectral anomaly detection based on Low-Rank representation and learned dictionary. Remote Sens. 8, 289 (2016).

Zhang, M., Gao, Y., Sun, C. & Blumenstein, M. A robust matching pursuit algorithm using information theoretic learning. Pattern Recogn. 107, 107415 (2020).

Gandomi, A. H., Yang, X. S., Alavi, A. H. & Talatahari, S. Bat algorithm for constrained optimization tasks. 22, 1239–1255 (2013).

Mallat, S. G. & Zhang, Z. Matching pursuits with time-frequency dictionaries. IEEE Trans. Signal Process. 41, 3397–3415 (1993).

Cai, T. T. & Wang, L. Orthogonal matching pursuit for sparse signal recovery with noise. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory. 57, 4680–4688 (2011).

Davenport, M. A., Needell, W. & Theory, M. B. Signal space cosamp for sparse recovery with redundant dictionaries. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory. 59, 6820–6829 (2013).

Kong, G., Zong, Z., Yang, J. & Chen, J. Sparsity adaptive matching pursuit and spectrum line interpolation method for measuring radial and axial error motions of spindle rotation. Measurement. 182, 109470 (2021).

Chen, H. A vibration signal processing method based on SE-PSO-VMD for ultrasonic machining. Syst. Soft Comput. 6, 200081. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sasc.2024.200081 (2024).

Zhou, F., Yang, X., Shen, J. & Liu, W. Fault diagnosis of hydraulic pumps using PSO-VMD and refined composite multiscale fluctuation dispersion entropy. Shock Vib. 2020, 8840676 (2020).

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (41904080), and the Key Research and Development (R&D) Projects of Shanxi Province (201903D121118), and in part by Shanxi Provincial Basic Research Program (202103021224186).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Software: S.G. and Z.G.; Data analysis: Z.G., C.Z. and S.G.; Investigation: J.L., K.F. and S.G.; Methodology: S.G., Z.G. and X.Z.; Resources: S.G. and K.F.; Supervision: J.L. and S.G.; Validation: K.F., S.G. and X.Z.; Writing—original draft: Z.G., J.G. and S.G.; Writing—review & editing: G.Z., K.F., X.Z., C.Z. and J.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ge, S., Gao, Z., Li, J. et al. Novel sparse decomposition with adaptive evolutionary atoms for nonstationary signal extraction. Sci Rep 15, 39744 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-12849-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-12849-z