Abstract

Current research on the progressive failure mechanisms and dynamic load transfer paths induced by localized failure in asymmetrical excavation support systems re-mains insufficient. This study, based on the “component removal method,” designs a model test for local failure of internal supports in an asymmetrically excavated foundation pit. Through refined three-dimensional numerical modeling, multi-condition comparative validation is conducted, revealing the coordinated evolution mechanism of deformation and internal force response following local support failure. Key findings demonstrate: post-failure reduction in lateral stiffness of supporting slabs induces inward dis-placements, amplifying surrounding soil settlement, with significantly greater dis-placement increments observed in deeper excavation zones compared to shallower regions; Axial force redistribution follows a proximity amplification and distal attenuation pattern, with adjacent struts experiencing force increases to 1.48 times after single strut failure, while distant struts show reductions to 0.93 times; Bending moments increase in remote support structures due to soil arching effects, reaching up to 427 N·m on the shallow side, whereas near-field structures exhibit moment reductions attributed to pronounced unloading effects from significant slab displacement; The secondary retaining wall exhibits cantilever-like behavior, with bending moments rising to 450 N·m post-failure.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

As a core discipline in underground space development, excavation engineering faces significant challenges due to intricate geological conditions and complex structural responses1. With accelerating urbanization, numerous excavation projects exhibit asymmetrical characteristics due to their specific functional requirements. This geometrical particularity complicates the stress distribution patterns of supporting members, potentially triggering localized soil instability or partial failure of retaining structures, which may ultimately lead to progressive failure of the entire excavation system.

Current research on deformation analysis of deep and large-scale excavations with symmetrical depth configurations has been extensively conducted globally. Chen, et al.2 investigated the potential of microbially induced carbonate precipitation (MICP) to enhance the shear strength of loess soil, highlighting the significance of biologically mediated approaches in improving soil properties. Cui, et al.3 employed an integrated approach combining field monitoring with numerical simulations to comparatively analyse the spatiotemporal evolution of structural forces in reinforced concrete retaining walls during ultra-deep excavations. Liu, et al.4 investigated the “corner effect” in rectangular deep excavations, systematically evaluating deformation patterns of retaining structures and adjacent building settlements, thereby optimizing strutted system designs. Yang, et al.5 explored the depth-dependent and spatial effects of various retaining schemes in soft soil regions, revealing significant spatiotemporal heterogeneity in structural deformations under unsupported excavation conditions. With increasing complexity in excavation engineering requirements, asymmetrical excavations with depth discrepancies have become prevalent in practice, where retaining structures exhibit pronounced deflection effects during excavation processes6, posing critical safety concerns. Xu, et al.7,8 addressed redundancy design issues in asymmetrical excavations through numerical analyses of peripheral soil settlements, developing depth calculation formulas for strutted retaining systems with differential excavation depths using the equivalent beam method. Their findings demonstrate that deeper excavation sides exhibit substantially greater ground settlement magnitudes and influence ranges compared to shallower sides, with soil thrust from deeper zones increasing the embedment ratio of retaining structures on shallower sides. Fan, et al.9 modified earth pressure calculations using non-limit state displacement theory, identifying significant errors in embedment ratio predictions derived from limit-state earth pressure assumptions within the equivalent beam method, particularly under large soil-structure stiffness contrasts. Kong, et al.10 conducted finite element analyses investigating the mechanical responses of asymmetrical excavation retaining systems to multiple factors, including strut positions, pile stiffness variations, and soil heterogeneity, ultimately proposing optimal embedment ratios for bilateral retaining structures under asymmetrical excavation conditions.

Retaining structures in excavations are classified as temporary structures with inherently low safety margins, exhibiting significant contingencies and uncertainties. Multiple documented cases globally11,12 demonstrate that localized support instability can trigger the catastrophic collapse of entire excavation systems, resulting in substantial economic losses and casualties. Consequently, progressive failure mechanisms induced by partial support component failures have garnered increasing research attention. Cheng, et al.13 employed explicit finite difference methods, discrete element modelling, and physical testing to analyze earth pressure redistribution and structural load variations following localized support failures. Zheng, et al.14,15,16 conducted comprehensive simulations and experimental studies on strut-pile systems, cantilever walls with spatial effects, and anchor-failure scenarios, elucidating the progressive collapse mechanisms under localized structural damage. Cheng, et al.17,18 performed comparative analyses using finite difference modelling and scaled tests to investigate mechanical responses during cantilever pile failures, establishing empirical correlations between load transfer coefficients and pile safety factors. Choosrithong, et al.19 implemented 3D parametric finite element modelling of a marine clay excavation, evaluating diaphragm wall integrity under single-strut failure conditions in soft soil environments. Yang, et al.20 utilized a visualized half-model test integrated with digital image correlation (DIC) techniques to reveal the progressive failure mechanisms of the foundation under combined vertical and horizontal (V-H) loading conditions for caisson foundations. Cheng, et al.21 developed discrete element models to investigate multi-level support collapse mechanisms, proposing dynamic redundant bracing systems to temporarily reinforce vulnerable excavation zones and enhance global resistance against progressive failure.

Currently, extensive research has been conducted by domestic and international scholars on the deformation characteristics of asymmetrically excavated foundation pits and the failure of local support structures in deep excavations with uniform excavation depths. However, studies on the holistic dynamic failure process induced by local support failures in asymmetrical excavations remain scarce. Only a limited number of researchers, such as Huanwei Wei22, have investigated the response of integrated support systems under local component failures in asymmetric excavations. While they proposed a design methodology enhancing structural redundancy by amplifying reinforcement moments of retaining piles considering progressive collapse, the progressive failure mechanisms and dynamic load transfer pathways remain insufficiently elucidated. This study focuses on asymmetric excavation pits and investigates the mechanical response of retaining structures and the evolution of soil failure under local support component failure. By integrating physical modelling and numerical simulations, cross-validated for accuracy, the research examines the effects of these failures on soil settlement at the pit edge, top displacement of the retaining structure, axial forces in the supports, and bending moments in the retaining structure. These findings aim to provide constructive guidance for the design and management of similar future engineering projects, offering practical insights for engineers.

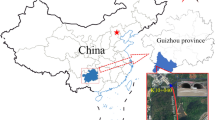

Overview of model experiments

This study employed a steel model box for the laboratory model tests. The box measures 1.1 m in length, 0.9 m in width, and 1.2 m in height. To ensure adequate structural strength and rigidity, three sides of the model box are fabricated from 10 mm thick steel plates. In contrast the fourth side is made of 19 mm thick high-strength tempered glass, allowing for visual observation of the soil layer thickness and soil behaviour during testing.

Fujian standard sand was used as the test soil. During the preparation stage, the specific physical parameters of the sand were determined through laboratory testing, as summarized in Table 1. Taking into account both the operability and mechanical properties of support materials in laboratory model testing, PVC pipes with a diameter of 20 mm, a wall thickness of 2 mm, and an elastic modulus of 3.44 × 109 Pa were selected to simulate the internal support system of the foundation pit. PVC plates with a thickness of 5 mm were used to simulate the retaining piles, and tensile tests conducted prior to the experiment yielded an elastic modulus of 3.14 × 109 Pa for the plates.

Considering the limitations of scaled model tests and the boundary effects inherent in laboratory experiments, the excavation depth on the deeper side of the foundation pit in this study was set to 500 mm, while the shallower side was excavated to a depth of 300 mm. The embedded depth of the primary and secondary retaining plates on the deeper side was 300 mm, whereas the embedded depth of the retaining plates on the shallower side was 500 mm. All retaining plates were first installed by embedding and then filled with soil in layers. A single row of internal supports was installed at the top of both side walls, with a horizontal spacing of 250 mm and a length of 300 mm. These supports were sequentially labeled as Supports 1, 2, 3, and 4, starting from the side nearest to the glass panel. A schematic diagram of the model setup is shown in Fig. 1.

Axial force sensors (AFS) were symmetrically installed along the internal struts to monitor the performance of the model, while displacement meters (DPM) were arranged at equal intervals on the ground surface. Additionally, linear variable differential transformers (LVDT) were affixed to the top of the retaining plates to monitor soil deformation around the excavation. Strain gauges (SG) were uniformly installed on the retaining plates with a vertical spacing of 150 mm and a horizontal spacing of 250 mm to monitor bending moments. The strain gauges on the deep-side retaining plate, secondary retaining plate, and shallow-side retaining plate were designated as SG1, SG2, and SG3, respectively. SG3 was installed at the same positions as SG1. The detailed layout of the monitoring instruments is also shown in Fig. 1. Specific testing conditions are listed in Table 2.

Analysis of test results

Analysis of displacement and settlement data

The variations in dial gauge and displacement meter readings are presented in Fig. 2. According to Working Condition 1, no significant ground settlement or lateral displacement of the retaining plates was observed when excavation reached the strut elevation. Upon excavation to the elevation corresponding to the shallow side, both retaining plates exhibited inward lateral displacement, accompanied by minor settlement of the surrounding soil. As excavation proceeded to the design depth on the deep side, active earth pressure on the deep-side retaining plate increased, causing further inward movement of the soil on that side. The excavation depth on the shallow side remained unchanged, but the load from the deep-side retaining plate was transferred through the internal struts, resulting in outward displacement at the top of the shallow-side retaining plate. Following the failure of Strut No. 1, the excavation remained relatively stable. However, under Working Condition 5, when Struts No. 1 and No. 2 failed simultaneously, the Displacement Meters 1 and 2 readings in the failure zone showed marked changes, with displacements decreasing by approximately 7 mm and 9 mm, respectively. After Struts No. 1, 2, and 3 failed, significant influence on the surrounding soil was observed, with settlements at the corresponding displacement monitoring points increasing by 18 mm and 29 mm, respectively. At monitoring points 5 and 6, which were located farther from the failed components, the increase in soil displacement was comparatively smaller, at approximately 6 mm and 4 mm, respectively. These observations can be attributed to the substantial reduction in lateral stiffness of the retaining plates following strut failure. The plates’ inward displacement led to the adjacent soil’s settlement. The deep-side retaining plate experienced larger displacements and greater associated settlements due to its relatively shallow embedment depth.

Analysis of strut axial force data

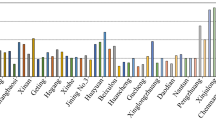

As shown in Fig. 3, the axial forces of the struts under different working conditions are illustrated. For Strut No. 2, the axial force continued to increase prior to failure, reaching a peak value of 62.98 N after the failure of Strut No. 1. The axial force in Strut No. 3 peaked at 70.24 N following the failure of Strut No. 2. Strut No. 4 reached a maximum axial force of 93.18 N after the failure of Strut No. 3. Based on the variation in the axial forces of the remaining struts after localized strut failures, it was observed that the failure of adjacent struts leads to an increase in the axial force of the remaining struts. In contrast, the failure of non-adjacent struts tends to cause a decrease in the axial force. To quantitatively analyze the variation in axial force due to strut failure, according to the research of Goch et al23, a load transfer coefficient (as listed in Table 3) is introduced to evaluate the influence of localized strut failure on both adjacent and non-adjacent struts. Let \({N}_{pre}\) represent the internal axial force in a non-failed strut before the failure, \({N}_{post}\) represent the axial force in the same strut after the failure, and \({N}_{fail}\) represent the axial force in the failed strut immediately prior to failure. The load transfer coefficient is defined by the following equation:

As shown by the coefficients in Table 3, all struts’ axial force variations were relatively consistent before excavation reached the final depth. Under Working Conditions 1, 2, and 3, the average load transfer coefficients of the four struts were 2.92, 5.58, and 1.65, respectively. After the failure of Strut No. 1, the axial force in Strut No. 2 increased to 1.48 times its original value. Meanwhile, the axial force in Strut No. 3 decreased to 0.93 times its initial value, and Strut No. 4 exhibited minimal change, reaching 1.03 times its original force. Following the failure of both Struts No. 1 and No. 2, the axial force in Strut No. 3 increased to 1.86 times its pre-failure value, while the axial force in Strut No. 4 decreased to 0.86 times its original value. In Working Condition 6, after three struts (No. 1, 2, and 3) failed, the remaining strut—Strut No. 4—experienced an increase in axial force to 2.11 times its initial value. These results indicate that when a strut fails, the load it originally carried is redistributed to the adjacent struts, causing an increase in their axial forces. As the number of failed struts increases, the redistributed load on the remaining struts becomes larger, leading to more pronounced increases in axial forces. This, in turn, elevates the risk of progressive failure due to insufficient load-bearing capacity of the remaining struts.

Analysis of bending moment data

In the test results, bending moments are defined as positive when the inner side of the retaining structure (facing the excavation) is under tension. For ease of interpretation, the bending moment measurements on both sides of the retaining plates are plotted separately, with the top two and bottom two rows of monitoring points displayed. The variations in bending moments at different measuring points on the deep-side retaining plate under various working conditions are shown in Fig. 4. From the initial stage through Working Condition 3, the positive bending moments above the excavation level increased, while the negative bending moments below the excavation level also increased. The deformation pattern of the retaining plate exhibited an “S” shape. After the failure of Strut No. 1, the bending moments at measuring points 1 and 5—located near the failure zone—decreased, with point 1 showing the most significant reduction. This is attributed to the loss of the moment-resisting effect provided by the failed strut.

Additionally, the inward displacement of the retaining plate induced an unloading effect, leading to a decrease in bending moment. In other areas, the bending moment increased due to the soil arching effect caused by local soil instability, which increased earth pressure behind the wall. Consequently, the inner side of the retaining plate experienced greater tensile stress above the excavation level and greater compressive stress below, resulting in an overall increase in bending moment. Although the unloading effect from lateral displacement also existed in these regions, the soil arching effect was dominant. Under Working Condition 6, after the simultaneous failure of Struts No. 1, 2, and 3, the lateral stiffness of the retaining plate was significantly reduced. The plate exhibited substantial inward displacement, which triggered a pronounced unloading effect, leading to an overall reduction in bending moment above the excavation level.

The bending moment variations at different measuring points on the shallow-side retaining plate under various working conditions are shown in Fig. 5. Due to the relatively greater embedment depth of the shallow-side plate, the inward lateral displacement following strut failure primarily occurred at the top of the plate and was significantly smaller than that of the deep-side plate. As a result, the stress state near the strut failure zone resembled that of a cantilevered pile. The tension side of the plate gradually shifted from the inner to the outer face, leading to a reversal in the bending moment. As shown in Fig. 5(a), after the failure of Strut No. 1, the bending moment at measuring point 1 changed from 306 N·m to –38 N·m, and at point 2 from 62 N·m to –131 N·m. As the number of failed struts increased, the soil arching effect became increasingly prominent, resulting in larger increments in the bending moment. Under Working Condition 6, the bending moment at point 1 increased by 427 N·m compared to that in Working Condition 4. In Fig. 5(b), a decrease in bending moment is observed below the excavation surface when the excavation reaches the final depth. This is due to the reduction in passive earth pressure in the shallow-side passive zone, which weakens the resistance of the soil and leads to a decline in the bending moment.

Prior to Working Condition 3 (pre-excavation to deep-side base elevation), monitoring points on the secondary retaining panel remained essentially undeformed with bending moments approximating zero (Fig. 6). A significant bending moment surge occurred during the transition from shallow-side elevation excavation to base formation, during which all monitoring points exhibited bending moment increments of varying magnitudes, with Monitoring Point 4 demonstrating a maximum increase of approximately 450 N·m. At base excavation completion, the mechanical behaviour of the secondary retaining panel became analogous to that of cantilever piles. Throughout subsequent Working Conditions 4–6, post-failure degradation of lateral stiffness in bilateral panels permitted inward displacement of the shallow-side panel. This kinematic response imposed additional stresses on active zone soils adjacent to the secondary panel, amplifying active earth pressures and consequently elevating bending moments in the secondary retaining structure.

Numerical simulation results and verification

Numerical model parameters

Following the methodology established by Goh et al23, when modelling sheet pile wall-supported excavations in Plaxis finite element software, the wall thickness can be arbitrarily assigned while maintaining equivalence to actual engineering conditions through preservation of the moment of inertia (\(I\)) and cross-sectional area (\(A\)). A dimensionless scaling factor (S) is introduced to modulate the elastic modulus (\(E\)) of the structural elements, enabling simulation of retaining piles with varying stiffness characteristics:

In this model, \(EI\) represents the stiffness of the retaining plate, \({\gamma }_{\varpi }\) represents the unit weight of groundwater, and \({h}_{avg}\) represents the spacing between the supports. A soil hardening (HS) model, which effectively reflects the stress path changes during the excavation process24, was used to simulate the asymmetric excavation of the foundation pit under localized strut failure. Based on the parameter calibration studies of the soil hardening model by Chen et al.25,26, and taking into account the loading characteristics of the asymmetrically excavated foundation pit, the HS model parameters adopted in this study are presented in Table 4.

Plate elements were used to model the retaining piles and beam elements were employed to simulate the internal struts. The soil’s material properties, excavation, support sequences, and strut failure conditions were kept consistent with those in the laboratory model tests. To simulate the localized failure of internal supports in an asymmetrical excavation, the method of sequential removal of structural elements was employed to progressively destroy the internal supports in one direction. Since the failure of one support significantly affects the adjacent supports in the horizontal direction27, the numerical model in this study assumes that the internal supports fail in the sequence illustrated in Fig. 7.

Structural internal force

Analysis of the laboratory model test results indicates that, due to the relatively high safety redundancy of the foundation pit support system, the failure of a single horizontal strut has a limited impact on the overall stability of the excavation28. However, when three struts fail simultaneously, a continuous plastic zone develops in the soil on the deeper excavation side, extending from the bottom of the pit to the ground surface, ultimately leading to global instability of the foundation pit. Therefore, the condition involving the failure of two struts is selected as a representative working case for analysing the mechanical response of the retaining structure.

Figure 8 illustrates the axial force variation curves of the remaining functional struts (Struts 3 and 4) in the retaining system under the simultaneous failure of Struts 1 and 2 during asymmetric excavation. From Working Conditions 1 to 3, it can be observed that with increasing excavation depth, the axial forces in the horizontal support system increase uniformly and linearly. When Strut 1 fails (Working Condition 4), stress redistribution occurs in the surrounding soil, reducing axial forces in Struts 3 and 4, which are located farther from the failure zone. When both Struts 1 and 2 fail, localized tensile stress concentration develops in parts of the soil, causing a significant surge in axial forces in adjacent struts, while in areas farther from the failure zone, the deformation of the retaining plates and the release of discrete soil stress result in a general trend of increasing axial forces near the failure and decreasing axial forces farther away. The axial force contour plots of the retaining structure further reveal that regions of high axial force are concentrated at the ends and contact interfaces of struts adjacent to the failed components, indicating a clear stress concentration zone. This observation provides additional evidence that localized failure induces spatially heterogeneous and nonlinear responses in the overall stability of the supporting system.

Characteristic deformations in asymmetric foundation pit excavations

The excavation face remained rectangular before reaching the shallow side excavation surface, and the retaining structures were symmetrically arranged. Under these conditions, the surrounding soil exhibited similar stress characteristics, resulting in uniform settlement. Due to active earth pressure, the deflection profile of the retaining wall showed a convex pattern towards the excavation face, with the maximum deflection occurring at the interface between the excavation base and the retaining wall29. Figure 9 illustrates the isosurface characteristics of deformation induced by asymmetric excavation of the foundation pit. Positive values are observed along the positive directions of the coordinate axes, while negative values appear along the opposite directions. With further excavation toward the deeper side, the embedment depth of the retaining structure on the deep side gradually became less than that on the shallow side, and the earth pressure on the deep side increased significantly, indicating a clear trend of horizontal soil movement toward the excavation. The maximum soil displacement on the deep side reached 14.77 mm, compared to only 6.4 mm on the shallow side, indicating significant asymmetry in soil deformation on both sides of the excavation. This observation further confirms the accuracy of the deformation characteristics observed under Working Condition 3 in the laboratory model test. Beneath the excavated area, a distinct “depression” shape formed by displacement contours can be observed, indicating localized inward and downward deformation of the soil mass, characteristic of a typical “arching collapse” mechanism. This deformation pattern reveals that, without adequate support, the plastic zone in the deep-side soil rapidly expands and forms a sliding surface, leading to a significant increase in the deformation of the surrounding soil. Due to the lateral restraint provided by the horizontal struts, soil displacement was relatively small at the strut locations. However, in areas farther away from the struts, particularly where flexible or low stiffness retaining structures were used, the soil control effectiveness significantly decreased, resulting in more severe soil failure. After the original stress equilibrium was disturbed, the soil experienced a pronounced unloading effect.

Shear failure characteristics

The formation and evolution of shear failure zones in the surrounding soil under various working conditions of the asymmetrical excavation are illustrated in Fig. 10. The dimensionless constant \(\gamma\) represents the tangent of the soil particle displacement angle, where a larger value of \(\gamma\) indicates more severe shear failure of the soil in the excavation. The process begins with the disruption of geostatic equilibrium during excavation to the deeper side, as shown in Fig. 10(a). The removal of soil induces an unloading effect, reducing confining pressure and triggering plastic deformation in the deeper soil layers. This is driven by the additional active earth pressure on the deep retaining wall, which has undergone significant shear failure up to a value of 0.015. The resulting shear strain concentration indicates the onset of a potential sliding trend in the deeper zone.

With the introduction of strut failure, the process is exacerbated due to the reduced lateral stiffness of the support system. Figure 10(b) illustrates the formation of an irregular elliptical shear slip zone near the failure region, where the dimensionless constant \(\gamma\) equals 0.01, attributed to weakened soil constraints and inward displacement of the retaining wall. This displacement amplifies shear stresses at the soil-structure interface, promoting upward propagation of the failure zone. As shown in Fig. 10(c), the concurrent failure of two struts results in the coalescence of plastic zones, forming a continuous failure band. This is driven by stress redistribution, where adjacent struts experience increased axial forces, such as Strut No. 3 increases to 1.86 times its pre-failure value, and localized tensile stress concentrations develop in the soil. Finally, as illustrated in Fig. 10(d), under Condition 6, a wedge-shaped sliding zone forms, extending from the pit bottom to the ground surface. The severe reduction in lateral support causes scattered shear strain distribution, with plastic failure emerging on the shallower side due to stress transfer through the secondary retaining wall. The progressive failure induced by local support collapse in asymmetrical excavations exhibits a spatial development trend—propagating from local to global and from the deeper to the shallower side.

Conclusion

This study employed a combination of physical model tests and numerical simulations to investigate the mechanical response of an asymmetrically excavated foundation pit under localized support failure. The "component removal method" was adopted to simulate the progressive failure process of internal supports. The main conclusions are as follows:

-

(1)

Excavation to the deeper side’s design depth of 500 mm significantly increased active earth pressure, causing inward displacement of the deep-side retaining wall, with maximum soil displacement reaching 14.77 mm compared to 6.4 mm on the shallow side. Strut failure reduced lateral stiffness, amplifying inward wall movements and soil settlements, particularly on the deep side due to its shallower 300 mm embedment, with settlements increasing by up to 29 mm after three struts failed.

-

(2)

Localized strut failure triggered a “proximity amplification and distal attenuation” pattern in axial force redistribution. After Strut No. 1’s failure, Strut No. 2’s axial force increased by 1.48 times to 62.98 N, while Strut No. 3’s decreased to 0.93 times. With three struts failed, Strut No. 4’s axial force surged 2.11 times to 93.18 N. This highlights the spatial heterogeneity and nonlinear nature of the structural response regarding overall stability.

-

(3)

Strut failure reduced earth pressure near failed struts but increased it in distant regions, with pressure increments proportional to the number of failed struts. Active earth pressure behind the secondary retaining wall also rose post-failure.

-

(4)

Near failed struts, inward wall displacement induced stress relief, reducing bending moments, e.g., a significant drop at deep-side monitoring point 1 after Strut No. 1’s failure. Conversely, soil arching in distant regions increased earth pressure, elevating bending moments. After three struts failed, reduced lateral stiffness caused substantial inward movement, lowering bending moments above the excavation face due to unloading effects.

-

(5)

On the shallow side, with a 500 mm embedment, strut failure shifted wall tension from the excavation side to the outer face, reversing bending moments — for example, bending moments at point 1 changed from 306 N·m to –38 N·m after Strut No. 1’s failure.. Increased strut failures amplified soil arching, raising bending moments by up to 427 N·m at point 1 under Condition 6. Below the excavation surface, reduced passive earth resistance decreased bending moments.

-

(6)

The secondary retaining wall exhibited cantilever-pile-like behaviour. Post-failure , reduced lateral stiffness and inward shallow-side wall movement increased active earth pressure, elevating bending moments, with a maximum increment of 450 N·m at monitoring point 4.

These findings elucidate the coupled deformation-internal force responses and load transfer pathways in asymmetrical excavations, providing valuable insights for enhancing structural redundancy and safety in similar engineering projects.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and the datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Ou, C. Y., Liao, J. T. & Lin, H. D. Performance of diaphragm wall constructed using top-down method. J. Geotech. Geoenviron. Eng. 124, 798 (1998).

Chen, Y., Zhang, R., Zi, J., Han, J. & Liu, K. Evaluation of the treatment variables on the shear strength of loess treated by microbial induced carbonate precipitation. J. Mt. Sci. 22(3), 1075–1086. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11629-024-9100-3 (2025).

Cui, Z., Li, Q. & Wang, J. Mechanical performance of composite retaining and protection structure for super large and deep foundation excavations. J. Civil Eng. Manag. 25, 431–440. https://doi.org/10.3846/jcem.2019.9873 (2019).

Liu, L. et al. Design optimization of the soil nail wall-retaining pile-anchor cable supporting system in a large-scale deep foundation pit. Acta Geotech. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11440-021-01154-4 (2021).

Yang, T. et al. Analysis of the deformation law of deep and large foundation pits in soft soil areas. Front. Earth Sci. https://doi.org/10.3389/feart.2022.828354 (2022).

Zheng, Z. C. & Zeng, D. Y. Deformation of asymmetric foundation pit caused by staged dewatering and excavation. Chin. J. Geotech. Eng. 35, 550–554 (2013).

Xu, C. J. et al. Deformation characteristic analysis of foundation pit under asymmetric excavation condition. Yantu Lixue/Rock Soil Mech. 35, 1929–1934. https://doi.org/10.2307/1571996 (2014).

Xu, C. J. et al. Analytical solutions of calculating length of retaining structures of foundation pit under asymmetric excavation. Rock Soil Mech. 38, 2306–2312. https://doi.org/10.16285/j.rsm.2017.08.019 (2017).

Fan, X. et al. Analytical solution for rigid retaining structure under asymmetric excavation in cohesionless soil. J. Shanghai Jiao Tong Univ. 54, 397–405. https://doi.org/10.16183/j.cnki.jsjtu.2020.04.008 (2020).

Kong, Y. et al. Optimal design of double-braced supporting structure in asymmetric excavation. Tunnel Constr. https://doi.org/10.3973/j.issn.2096-4498.2023.S1.041 (2023).

Zhang, L. J. Accident analysis for“08.11.15”foundation pit collapse of Xianghu Station of Hangzhou metro. Chin. J. Geotech. Eng. 32, 338–342 (2010).

Xiao-chun, X. & Jin-rong, Y. Causation analysis of the collapse on Singapore MRT circle line lot C824 (Part II) ——— critical design errors in temporary retaining system. Mod. Tunnell. Technol. 46, 28–34. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1009-6582.2009.06.004 (2009).

Cheng, X. S. et al. Mechanism of progressive collapse induced by partial failure of cantilever contiguous retaining piles. Chin. J. Geotech. Eng. 37, 1249–1263. https://doi.org/10.11779/CJGE201507011 (2015).

Zheng, D. C. Influence of space effect on progressive collapse in excavations retained by cantilever piles. J. Tianjin Univ. 49, 1016–1026. https://doi.org/10.11784/tdxbz201601012 (2016).

Zheng, L. Y. & Cheng, L. X. Experimental study on influences of local failure on steel-strutted pile retaining system of deep excavations. Chin. J. Geotech. Eng. 41, 1390–1399. https://doi.org/10.11779/CJGE201908002 (2019).

Zheng, G. et al. Mechanism and control of progressive collapse of tied-back excavations induced by local anchor failure. Acta Geotech. Int. J. Geoeng. 19, 763–781. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11440-023-01930-4 (2024).

Cheng, X. S. et al. Study of the progressive collapse mechanism of excavations retained by cantilever contiguous piles. Eng. Fail. Anal. 71, 72–89. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engfailanal.2016.06.011 (2017).

Cheng, X. S. et al. Experimental study of the progressive collapse mechanism of excavations retained by cantilever piles. Can. Geotech. J. 54, 574–587. https://doi.org/10.1139/cgj-2016-0284 (2017).

Choosrithong, K. Numerical investigation of sequential strut failure on performance of deep excavations in soft soil. Int. J. Geomech. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)GM.1943-5622.0001695 (2020).

Chen, Y. et al. Experimental and analytical study on the bearing capacity of caisson foundation subjected to V-H combined load. Mar. Georesour. Geotechnol. https://doi.org/10.1080/1064119X.2025.2466787 (2025).

Cheng, X. et al. Study on the mechanism and countermeasures of progressive collapse in deep excavation retained by multilayer struts. Structures https://doi.org/10.1016/j.istruc.2023.105837 (2024).

Wei, W. T. Influence of local component failure on retaining system under asymmetric excavation. J. Hohai Univ. 50, 92–100. https://doi.org/10.3876/j.issn.1000-1980.2022.06.012 (2022).

Goh, A. T. C., Fan, Z., Hanlong, L. & Dong, Z. Numerical analysis on strut responses due to one-strut failure for braced excavation in clays. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Symposium on Asia Urban Geoengineering 560–574 (Springer, 2018).

Schanz, T., Vermeer, P. A. & Bonnier, P. G. The hardening soil model: Formulation and verification. In Beyond 2000 in Computational Geotechnics 281–296 (Routledge, 2019).

Cao, M. et al. Experimental study of hardening small strain model parameters for strata typical of zhengzhou and their application in foundation pit engineering. Buildings https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings13112784 (2023).

Ge, Y. M. & Li, Z. M. Influence of deep foundation pit excavation on surrounding environment: a case study in Nanjing, China. Acta Geophys. 73(1), 495–516. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11600-024-01425-0 (2025).

Yi, F. et al. Progressive collapse analysis and robustness evaluation of a propped excavation failed due to inappropriate strut removal. Acta Geotech. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11440-023-01929-x (2023).

Wan, Q. et al. Automated inverse design of asymmetric excavation retaining structures using multiobjective optimization. J. Rock Mech. Geotech. Eng. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrmge.2024.11.058 (2025).

Hong, L. et al. System reliability-based robust design of deep foundation pit considering multiple failure modes. Geosci. Front. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gsf.2023.101761 (2024).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

1-J.C.: Writing – Original draft; Model test; Software. 2-F.S.: Formal analysis; Data Curation; Visualization. 3-H.W.: Review & editing; Conceptualization; Supervision. 4-X.Z.: Methodology; Validation. 5-F.L.: Conceptualization; Numerical simulation; Methodology; Review.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chong, J., Su, F., Wei, H. et al. Progressive failure mechanisms and dynamic load redistribution in asymmetric excavation with partial bracing collapse. Sci Rep 15, 27359 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-12855-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-12855-1