Abstract

Wireless Sensor Networks (WSNs) are considered essential to distributed sensing in agricultural, health and industrial domains. Although WSNs have several advantages, they encounter profound cybersecurity threats owing to their processing capacities and small energy sources. In this research work, an intrusion detection framework based on deep learning is designed: a combination of Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) and Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) with an adversarial-aware optimization model. The benchmark datasets of NSL-KDD, CICIDS2017, UNSW-NB15, and CTU-13 are analyzed in a number of ways based on structure, diversity, and deep learning requirements. We propose a compound objective to optimize all of these simultaneously, maximizing detection accuracy, minimizing adversarial vulnerability and ensuring model generalizability. Synthetic oversampling with SMOTE is employed to deal with this. Cross-dataset and intra-dataset experiments are implemented when testing the proposed framework, and it outperforms in terms of robustness and transferability. Our efforts are practical in terms of the deployment of a lightweight and resilient IDS that is suitable for WSN settings.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

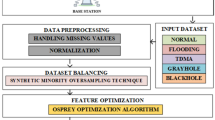

Wireless Sensor Networks (WSNs) are the new face of the Internet of Things (IoT) that allows the acquisition of environmental and system information in real time1. Be that as it may, the broad organization of WSNs likewise presents new security weaknesses, especially in the domain of physical security2,3. Physical security alludes to the protection of WSN gadgets and their related framework from unapproved access, alteration, or obliteration4. Physical security, which includes the insurance of WSN gadgets and framework from physical mischief, is an essential part of guaranteeing the trustworthiness and dependability of these networks5,6. One of the essential worries in WSN physical security is the weakness of sensor hubs to unapproved access7. These hubs are commonly little and minimal expense, making them more straightforward to think twice about compared to conventional registering gadgets. Assailants can physically alter sensor hubs to change their way of behaving, take delicate data, or even render them inoperable8. To alleviate this gamble, WSNs ought to be planned with powerful physical assurance instruments. This incorporates utilizing alter safe walled in areas9, utilizing cryptographic methods to get data transmission10, and carrying out intrusion detection systems11 to screen for unapproved access endeavors. One more significant part of WSN physical security is the insurance of the organization framework12. This incorporates the base stations, power sources, and communication channels that help the sensor hubs. Physical assaults on framework can upset network activities, compromise data protection, and even reason huge monetary losses13. Consequently, it is vital for carry out measures, for example, physical access controls, observation frameworks, and natural checking to defend basic foundation parts. Notwithstanding physical assaults, WSNs are additionally vulnerable to environmental dangers like extreme atmospheric conditions, electromagnetic interference, and catastrophic events14. These variables can harm sensor hubs and foundation, prompting network blackouts and data loss. To improve strength against ecological dangers, WSNs ought to be intended to be robust and sturdy, with fitting assurance against unforgiving circumstances15. This may involve using weatherproof enclosures, employing redundant components, and implementing backup power sources16. Figure 1 explains the process of enhancing the intrusion detection system in WSN.

Furthermore, WSN physical security ought to be viewed in regards to the general security stance of the organization. This incorporates resolving issues, for example, network access control, data encryption, and weakness the board. By taking on a far reaching way to deal with security, associations can fundamentally decrease the gamble of physical assaults on their WSNs17. Physical security is a basic part of guaranteeing the integrity and unwavering quality of Wireless Sensor Networks. By executing powerful assurance systems, associations can mitigate the risk of unapproved access, natural disasters, and other physical assaults18. An extensive way to deal with WSN physical security, joined with successful organization security rehearses, is fundamental to shielding the important data and services provided by these networks. WSNs are also extensively used in surveillance of environmental conditions, including air quality, water pollution, soil moisture19, timely detection of natural catastrophes, climatic effects, as well as pollution foci20. In the agricultural sector, they optimize precision farming through monitoring of soil conditions, plant health, and weather forecasts to ensure less water and pesticide are used21. WSNs in healthcare promote the monitoring of patients remotely, wearable, and intelligent home devices by measuring vital signs and analyzing abnormalities to help provide timely medical care22. Figure 2 shows the different types of WSN attacks.

WSNs are employed in factories and manufacturing facilities for tasks such as asset tracking, condition monitoring, and predictive maintenance. They improve efficiency, reduce downtime, and enhance safety23. WSNs play a crucial role in building smart cities by enabling intelligent infrastructure, traffic management, waste management, and energy conservation24.

Problem statement

Although deep learning has proven successful in cybersecurity, there is a large gap in how to evaluate the proper usage and applicability of the popular NSL-KDD and CICIDS2017 datasets across a variety of tasks and use cases25. These datasets are standard, hence they have problems such as obsolete attack patterns26, a large size and high resource requirements27, lack of domain applicability [40 years], class imbalance, and overfitting due to reuse28. Additionally, there are no standardized guidelines defining what to select a dataset for, and it complicates the development of robust models for specific tasks, as datasets, such as CTU-13 or UNSW-NB15, though containing a lot of information, often are neglected without a proper framework29. Most studies do not assess the cross-task transferability and end up with models that perform well within a very narrow context but fail to generalize when applied elsewhere30. These limitations present a need for a systematic, comparative approach, which compares datasets against traditional metrics but also on their generalizability, diversity, and pertinence to evolving threats31. Standardized dataset selection frameworks can form the basis for developing more resilient, scalable, and adaptive deep learning models for real-world cybersecurity problems.

Motivation and challenges in WSN security

The use of WSNs in critical infrastructure presents great difficulties in improving resource-constrained security of devices against the dynamic cyber challenges. Such challenges are low memory, constrained energy supply, decentralized control, dynamic topology, and constrained physical protection. Such limitations do not enable applicability of conventional IDS mechanisms. As such, there is a great need to develop the capability to create lightweight, real-time, and robust detection frameworks which can be run within limited modes but still deliver formidable detection rate.

Objectives

The purpose of this study is to close the gap in the comparison of the cybersecurity datasets that currently exist by investigating four common benchmarks, including NSL-KDD, CICIDS2017, UNSW-NB15, and CTU-13, on the basis of structure, size, and applicability to deep learning models. These datasets have been used extensively in the intrusion detection research, however, they are quite different in feature count, attack diversity, data granularity, class imbalance, etc. For example, NSL-KDD has only 41 features, making it lightweight but limited in expressive power; however has a limitation in terms of expressivity32, while CICIDS2017 contains 85 features and as such provides a richer representation of network traffic at the cost of higher computational load33. In this paper, we look at which dataset helps various deep learning models (CNNs, RNNs/LSTMs, and autoencoders) perform well at various metrics (accuracy, precision, recall, false positive rate). Thus, for the example of structured flow data, CNNs work well34, RNNs are more suitable for time series logs35, and autoencoders are better for cases such as CTU-13 when a significant part of the attack traffic is sparse36. Since we are dealing with imbalanced datasets, in which benign traffic greatly predominates37, we stress the necessity of performance metrics like recall and false positive rate rather than raw accuracy. The size of the dataset is related to generalizability and training efficiency, as NSL-KDD is small but can overfit, while CTU-13 and CICIDS2017 have larger traffic diversity but are expensive to process38. UNSW-NB15 provides a compromise between modern attack profiles and medium size39. The paper also discusses dataset-specific challenges including imbalanced classes (it is observed in NSL-KDD that the imbalance may results in normal traffic bias, in CTU 13 that sparse attacks impede learning and in CICIDS2017 that its large size strains the model resources40,41). This study identifies these issues and proposes practical solutions to assist both researchers and practitioners to pick and prepare suitable datasets for the effective building of intrusion detection systems based on deep learning.

Novelty and key contribution

Finally, the study will provide recommendations for selecting relevant datasets for specific cybersecurity tasks. We will offer advice for selecting datasets that meet the particular needs of a certain task, like malware classification, intrusion detection, or botnet detection, based on the results of our comparison research. For instance, we might advise CICIDS2017 for academics working on more complex intrusion detection tasks, incorporating contemporary attack patterns, or NSL-KDD for researchers searching for a lightweight dataset to test fundamental intrusion detection algorithms33,42. By offering these recommendations, we aim to help researchers and practitioners make informed decisions about which datasets to use in their work, ultimately leading to more robust and effective deep learning models for cybersecurity applications.

In particular, the proposed framework proposes a set of new mechanisms that would improve the performance, stability, and generalized of deep learning in WSN-based security systems. Previous work has studied cross-dataset generalization analysis on isolated dataset evaluation or rather in a more isolated evaluation setup of any individual chosen model architecture, while our work embodies a holistic approach in which we jointly consider cross dataset generalization analysis, adversarial defense strategies, as well as a mathematically justified optimization framework. The major contribution in this work include:

-

A primary cross-dataset generalization metric that can measure models’ performances on different datasets to overcome the transferability test in real-world WSN cybersecurity.

-

An overall optimization criterion that is a combination of accuracy, adversarial resilience against small perturbations in the data, and applicability to data that have not been used for training.

-

Combination of adversarial training, feature hardening, and detection techniques to enhance the high-level resistance solutions against the WSNs evasion attacks.

-

This paper contains the evaluation of multiple deep learning models, including CNN, RNN, LSTM, etc., in real and synthetic datasets such as NSL-KDD, CICIDS2017, UNSW-NB15, and CTU-13.

-

Application of SMOTE during preprocessing to increase the data variety and overcome the class imbalance problem which is not typically analyzed in most IDS systems, as well as threat simulation.

-

Scalable and expandable architecture to decide how to structure the core of the application and let the system learn in real-time for unknown threats in sensor networks with limited resources.

The rest of this paper is structured as follows: “Literature review” reviews related work of deep learning models and cybersecurity datasets. Section “The proposed famework” describes the proposed framework, which consists of data processing, model training, and adversary defense strategies. Section “Experimental setup” details the experimental setup and evaluation metrics. Section “Result and discussion” presents and analyses the results over different models and datasets. Section “Conclusion and future work” concludes the study and provides research directions for future.

Literature review

The decentralized architecture and limited resources make Wireless Sensor Networks (WSNs) prone to a large number of threats on their security. Some typical attacks are Sybil attack, a malicious node creates several fake identities, and uses it to work against routing protocols; sinkhole attack, the malicious node lures the other nodes to the location and misreports the existence of the optimum routes to the network; wormhole attack, the colluding attackers still develop a low-latency communication route to use in tunneling packets and manipulating network topology; blackhole attack, the malicious node intentionally discards any sent packet towards it; selective forwarding, specific packets are dropped by selective forwarding to disorder the communication indirect These threats have led to a number of defense mechanisms that have been suggested and these include trust-based routing, cryptographic authentication and lightweight encryption protocols. Anomaly detection in machine learning frameworks have emerged in the recent past as one of the frameworks which learn the dynamics of attack patterns. Nonetheless, a significant number of such countermeasures are either resource-consuming or even fail to keep up with the changing threats thus necessitating the use of lightweight, generalizable and data driven solutions such as the one suggested in the present study.

Deep learning (DL) is a key component of the complex security systems that have been developed in response to the sharp rise in cyberattacks. Advanced persistent threats (APTs), ransomware, and distributed denial-of-service (DDoS) assaults are among the growing concerns that have forced the cybersecurity community to embrace more resourceful and independent strategies. Traditional rule-based systems and conventional machine learning algorithms, while useful, often struggle to keep pace with the evolving nature of cyber threats. In contrast, deep learning models offer the ability to automatically extract features from raw data, enabling them to detect patterns and anomalies within complex, high-dimensional datasets43. Deep learning has thus been widely used in cybersecurity applications such as threat intelligence, malware categorisation, intrusion detection systems (IDS), and phishing detection. Deep learning models like Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) and Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) are being utilised more often in intrusion detection to spot unusual activity in network data. By identifying previously undiscovered attack patterns, these models frequently outperform conventional techniques in the detection of a wide range of attack types, such as port scans, SQL injections, and brute force attacks44. Malware classification is another critical application where deep learning excels. By leveraging large datasets of labeled malware samples, deep learning models can categorize malware families with high accuracy, even when the malware obfuscates its code to evade detection45. Similar to this, deep learning models in threat intelligence may extract valuable insights and real-time alerts from massive amounts of unstructured data, like social media feeds and security logs46. Despite these advancements, the effectiveness of deep learning models in cybersecurity heavily depends on the quality, diversity, and representativeness of the training datasets used. Quality refers to the accuracy and cleanliness of the data. Datasets with noisy or mislabeled data can mislead the learning process, causing models to make incorrect predictions or fail to generalize to new situations. For instance, a dataset that incorrectly classifies legitimate traffic as malicious (or vice versa) during the training process of an intrusion detection system (IDS) may produce a large number of false positives or false negatives, significantly reducing the utility of the model47.

Diversity is also another important element. The tactics, methods, and procedures (TTPs) of cyberattacks vary significantly, and a dataset that concentrates too much on a single attack type may not expose users to enough of the range of risks they may face in real-world settings. A model that has only been trained on DoS attack traffic, for example, might not be able to identify more covert attacks like privilege escalation or data exfiltration. Therefore, datasets must contain a broad spectrum of attack types, including both traditional attacks (e.g., viruses, worms) and modern threats (e.g., APTs, fileless malware)48. Lastly, representativeness is essential to the functioning of the model. Deep learning models need datasets that are as similar to real-world situations as possible. Numerous open datasets, such as UNSW-NB15 and NSL-KDD, are made to mimic network traffic in regulated settings49. Although these datasets are helpful for benchmarking, WSN researchers50 note that they frequently fail to depict the entire complexity of real-world networks, which includes the existence of encrypted traffic, valid abnormalities, and fluctuating traffic patterns throughout the day. Moreover, some datasets are artificially generated, which can lead to overfitting if the model learns to detect patterns specific to the dataset rather than generalizable attack patterns26. Lack of standardized and up-to-date datasets that properly depict the current danger landscape is a major difficulty in this field. Cybersecurity is a constantly evolving field, with attackers continuously developing new methods to evade detection. As a result, models trained on outdated datasets may be unable to detect the latest threats. For example, the KDD99 dataset, although one of the most frequently used in research, is considered outdated due to its focus on attacks that were prevalent in the late 1990s. Modern datasets like CICIDS2017 and CSE-CIC-IDS2018 attempt to address this issue by including a wider range of contemporary attack types, such as ransomware and botnets, but even these datasets can become obsolete as new threats emerge51.

A further issue is that a lot of datasets are imbalanced, which means that a disproportionate amount of normal (or benign) traffic samples are present in comparison to malicious samples. This may distort the process of training models, leading deep learning models to ignore uncommon but important attack patterns in favour of regular traffic. Although methods like cost-sensitive learning and oversampling of minority classes have been suggested to address this problem, they are not always effective, especially in situations where there is a great degree of imbalance52. The presence of adversarial attacks is another factor that complicates the application of deep learning in cybersecurity. The creation of intentionally misleading inputs for deep learning models is known as an adversarial attack. For instance, to avoid detection, attackers can modify malware code or subtly alter network traffic by adding perturbations that are undetectable to human analysts but successful in deceiving machine learning models53. Models trained on poorly designed datasets are especially vulnerable to adversarial attacks, as they may learn to rely on superficial features rather than robust patterns that are resistant to manipulation. Cybersecurity researchers must carefully choose datasets that not only offer a representative sample of real-world traffic but also take into account the varied and ever-evolving nature of cyber threats in order to reduce these difficulties. Expanding the range of threats in a dataset and strengthening models can be achieved by data augmentation, which involves creating synthetic data to supplement existing data54. Additionally, the development of continual learning systems, which can update their knowledge base as new attacks emerge, offers a promising avenue for enhancing the adaptability of deep learning models in cybersecurity55. In conclusion, With references to31,39, deep learning models, including CNNs and RNNs, have shown more effectiveness compared to classical ML models, such as SVM and the Random Forest, in particular threat detection tasks.. Poorly constructed datasets can lead to models that are overly specialized, prone to adversarial attacks, or incapable of generalizing to new threats. As the threat landscape continues to evolve, the need for up-to-date, comprehensive, and representative datasets will become even more critical. Researchers and practitioners must continue to explore innovative approaches for dataset construction and model training to ensure that deep learning remains a viable solution for securing digital infrastructures in the face of increasingly sophisticated cyberattacks.

Deep learning has transformed cybersecurity by offering more precise and scalable methods for threat detection and prevention. Because they can analyse massive volumes of data in real time, techniques including autoencoders, Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks, and Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) have been widely used for cybersecurity tasks56. CNNs are especially good at spotting network intrusions, although LSTM models operate better with time-series data, including traffic log abnormalities56. These models are effective, but the datasets that are used to train them have a significant impact on how well they perform. Datasets in Cybersecurity Having access to high-quality datasets is essential for creating deep learning models that work. Several benchmark datasets have been widely used in cybersecurity research. The NSL-KDD dataset is an improvement over the older KDD Cup 1999 dataset, addressing issues such as redundant records and providing a more balanced representation of network traffic49. The CICIDS2017 dataset, generated by simulating real-world attack scenarios, provides a more contemporary dataset with a variety of attack types33. UNSW-NB15 combines synthetic attacks with real network traffic, offering a dataset that is both comprehensive and scalable49. The CTU-13 dataset, focused on botnet traffic, is useful for detecting botnet-based attacks, which are becoming increasingly prevalent29. Every dataset has advantages and disadvantages that vary based on the task at hand. While CICIDS2017 better reflects current attack patterns but can be computationally expensive to analyse due to its size, NSL-KDD, for instance, is appropriate for basic intrusion detection but lacks diversity in recent attack types57. Prior Comparative Studies Several studies have attempted to compare datasets in cybersecurity, but most focus on classical machine learning methods rather than deep learning. For instance,58 compared several datasets for intrusion detection using traditional classifiers like Random Forests and Support Vector Machines. Although informative, their work does not extend to modern deep learning architectures, which can capture more complex data relationships. Additionally, previous studies have not systematically evaluated these datasets in terms of specific performance metrics like false positive rates or scalability59.

Apart from the classic scenarios used for benchmarking and the standard deep learning approaches, more recently, the studies have progressed towards the development of new techniques to improve threat detection in resource-limited settings. For instance, He et al. then introduce60, a federated learning architecture that is optimized for WSNs, to leverage data privacy within the network as well as to decentralize learning over nodes. Finally,61 explores another direction in which they apply graph based neural networks to detect cross node attack propagation in IoT infrastructures and achieve better performance compared to practice.62 addresses the problem of intrusion detection using hierarchical architectures of lightweight CNN models with feature pruning for embedded WSN devices.63 further evaluated transformer-based models for network anomaly detection, interestingly results show impressive network anomaly detection capability for stealthy attacks like low-rate DDoS. This is unlike traditional dataset such as NSL-KDD and CICIDS2017 for IDS where they are in the structure of environment for the IDS training, but in research of64 they propose the use of generating realistic data in the form of synthetic data using GANS (Generative Adversarial Networks)to augment minority attack classes and avoid over fitting. Such emerging methodologies emphasize the importance of not just picking various datasets but also boosting the functionality of the dedicated data-forwarding architecture and embracing architectural advancements that tackle the real-world deployment difficulties of WSNs and IoT.

Table 1 gives a comparative overview of the literature of recent intrusion detection based on deep learning to Wireless Sensor Networks (WSNs) until the year 2025. Currently, techniques that have been tested in the surveyed works are conventional deep neural networks (DNN), long short-term memory (LSTM) autoencoders, hybrid CNN-GAN, federated learning and ensemble techniques 65. Remarkably, such models as LSTM-based IDS or Transformer-based structures already have high rates of the anomalies detection in large datasets tested, such as UNSW-NB15 or Kitsune, and this shows prospects of correct detection of anomalies. Nonetheless, these solutions are also plagued with serious drawbacks, which include: high complexity computationally, overfitting risks, non-generalization over concept drift and inefficient consumption of energy, which are particularly important problems when the WSNs are resource limited. Other works have tried to overcome them, with lightweight frameworks or privacy-preserving frameworks, like federated self-supervised learning or online adaptive ensembles. Still, the majority of strategies are limited by the scalability or deployment challenge, so the requirement in robust, flexible, and computationally efficient solutions can further be justified, which also defines the design goals of our proposed framework.

The proposed famework

The proposed framework outlines a comprehensive approach for assessing and improving the state of deep learning solutions in cybersecurity with special emphasis to dataset assessment and improvement, model robustness in applying deep learning in adversarial contexts, and optimisation of scalable training strategies to advance cybersecurity solutions. There is also a focus on choosing a variety of datasets with a focus on some NSL-KDD, CICIDS2017, UNSW-NB15, CTU-13 datasets that reflect both traditional and modern attack types and contain both synthetic and real data. Transformations include standardization or scaling of features for efficient convergence, class weighting to address imbalanced classes through SMOTE, and generation of data variation through simulation of emerging threats on dataset. The structure uses CNNs in spatial data and RNNs, LSTM in time series; uses autoencoders for anomalies; employs hyperparameter adjustment through grid search or Bayesian; and addresses overfitting via dropout. The framework combines adversarial training as a regularization step, the incorporation of adversarial examples, feature hardening to isolate robust patterns, and inclusion of measures to detect adversarial inputs during deployment. The model evaluation criteria, including accuracy, precision, recall, false positive rate, F1 score, and computation cost, gives a broad evaluation on system’s performance. Benchmarking includes assessment in standard datasets, validation across datasets to evaluate on its ability to generalize and perform well in different scenarios, and lastly, evaluation based on real and realistic scenarios for cybersecurity threats such as Distributed Denial of Service and botnet. It also includes nding ways for enhancing the framework’s adaptability to learn new attack behaviors or data streams representing real-world conditions for the purposes of scalability and robustness in proactively responding to emerging types of cyber threats.

The flowchart in Fig. 3 reveals a detailed security model and improved deep learning models for intrusion detection and threat prevention. It begins with the selection of datasets which are relevant to analyzing cybersecurity through network traffic and a variety of attacks. Several techniques are applied to this selected data, such as SMOTE (Synthetic Minority Over-sampling Technique) to manage the imbalanced dataset, and scaling is also applied to normalize feature values for fast model convergence. The model training phase involves CNN, RNN, and LSTM techniques to train and construct the models, and involves hyperparameter tuning adjustments to optimize them. To further increase security, adversarial defense mechanisms and feature hardening techniques are incorporated in order to render the models robust to evasion attacks and adversarial inputs. The trained models contain high-efficiency parameters, including accuracy, preciseness, and recall in order to guarantee threat identification. The generalizability of the results is then evaluated by benchmarking and comparing the results to other publicly available datasets. They are then used for real-time cybersecurity monitoring to make it easier to learn more as new threats arise. Feedback is a closed-loop process that allows the datasets selected and the model that is built to remain up to date by feeding monitoring data back into the system. This structure guarantees a systematic, diverse, and robust protection measure against emergent cyber threats due to its efficacious nature in opposition to traditional ones.

Mathematical modeling of proposed framework

Suppose we are given a set of datasets \(\mathcal {D} = \{D_1, D_2, \dots , D_n\}\) where each dataset \(D_i = \{(x_k, y_k)\}_{k=1}^{N_i}\) contains \(N_i\) samples \(x_k \in {\mathbb {R}}^m\) along with labels \(y_k\). The goal of the framework is to maximize the utility \(J\) by maximizing performance (\(P\)), by minimizing adversarial vulnerability (\(A\)), and by improving generalizability (\(G\)). This is expressed mathematically as:

\(\alpha , \beta , \gamma\) are weight coefficients that balance contributions from each component so as to provide an effective and robust solution for the issues encountered by the applications in cybersecurity. The objective function which is a combination of accuracy, robustness, and generalizability is defined in Eq. (1) with weighting factors, \(\alpha\), \(\beta\), and \(\gamma\).

The performance \(P\) is calculated as a weighted sum of the key metrics – accuracy, precision, and recall are evaluated across all datasets and models. The mathematical expression for \(P\) is given as:

And here, \(n\) is the total number of datasets, \(p\) is the total number of models and \(\omega _{\text {acc}}, \omega _{\text {prec}}, \omega _{\text {rec}}\) hyperparameters that define the relative importance of accuracy, precision and recall. The robustness is assessed with and without the adversarial perturbation of the model, as demonstrated in Eq. (2). These weights are always used to balance the contributions of each metric to the aggregate performance, being flexible to specify different values of each metric according to the requirements of the application. The accuracy of a model \(M_j\) on dataset \(D_i\) is computed as:

where \(\text {TP}, \text {TN}, \text {FP}, \text {FN}\) represent the true positives, true negatives, false positives, and false negatives, respectively.

Precision measures the proportion of correctly identified positive instances among all instances predicted as positive, and it is defined as:

Recall, also known as sensitivity, quantifies the proportion of actual positive instances that are correctly identified by the model. It is expressed as:

From the confusion matrix, we get \(\text {TP}, \text {TN}, \text {FP}, \text {FN}\) metrics, which represent a detailed description of model performance in terms of the prediction types – correct and incorrect. The performance measure \(P\) has been aggregated across all datasets and models in order to give a thorough evaluation of how well the framework performs in all scenarios. Including the weights \(\omega _{\text {acc}}, \omega _{\text {prec}}, \omega _{\text {rec}}\) assures that the performance is measured in ways consistent with particular performance goals, e.g., by maximizing recall or sacrificing it in favor of a balanced tradeoff between precision and recall respectively for anomaly detection applications, or for intrusion detection systems. With this formulation, the framework can be made adaptable and scalable so that it remains robust and also effective for different datasets and model architectures.

A measures the adversarial vulnerability of a model, which is defined as the robustness of a model against small perturbations \(\epsilon\) applied to the input data \(x\) in a way that cajoles the model into making a silly prediction. Mathematically, \(A\) is expressed as:

here \(p\) is the overall number of models and \(n\) denote the number of total datasets and \({\mathbb {E}}_{x \sim D_i}\) represents the expectation taken over dataset \(D_i\). The model \(M_j\) misclassifies \(x + \epsilon\) if and only if the indicator function \({\mathbb {I}}\) returns 1. It assumes that the adversarial perturbation \(\epsilon\) is a vector that satisfies the constraint of \(\Vert \epsilon \Vert \le \delta\) the maximum allowable perturbation magnitude. For instance, \(\Vert \cdot \Vert _2\) norm is often used to measure how large the perturbation is. They can take advantage of the model’s vulnerability to perturbations in terms of very weak or superficial features. In all our adversarial experiment tests, we fix \(\delta = 0.05\) in accordance with prior suggestions of sensitivity tests in the adversarial learning corpus of literature. This value makes these models undetectable during a human check and, at the same time, influences their predictions. To confirm this setup, the mean decline in accuracy across datasets due to adversarial input injection was also measured, which also showed a predictable trade-off between performance and robustness. Adversarial perturbations are often generated using methods like the Fast Gradient Sign Method (FGSM), which computes \(\epsilon\) as:

It is done under the condition that \(\mathcal {L}\) is a function of the model, for example, cross-entropy, and \(\nabla _x \mathcal {L}\) is the gradient of the loss concerning the input \(x\). This technique generates distortions that are most lethal to the signal, thus ‘fooling’ the model. Measuring adversarial vulnerability reveals some of the models’ shortcomings and lays a starting point for enhancing model robustness. This becomes important, especially in cybersecurity, where the threat actors are always predisposing inputs that would not trigger any alarm. In order to measure the adversarial vulnerability, we used Fast Gradient Sign Method (FGSM) that has been executed through CleverHans v4.0.0 and TensorFlow v2.11 libraries. In every dataset, the test set size (15% of all the samples) has been used to create the same number of adversarial examples. The results presented in this paper used a perturbation bound, based on the \(L_{\infty }\)-norm, of \(\delta = 0.05\), which enforced after being used in an experiment, the catastrophic prevention of changes that would be noticeable, subjectively by a human tester. Feature scaling was done with normalized input vectors against which FGSM attack was used, and all other predictions were compared to calculate the adversarial vulnerability term A in the objective function.

Generalizability \(G\) quantifies the effectiveness of models to work on other datasets after training on another set of data. This is an essential consideration for cybersecurity applications since models confront different situations and continually emerging threats. Generalizability also allows us to predict high levels of accuracy for a model trained on one data set \(D_i\) depicting good performance when challenged with other different data sets \(D_j\), where \(i \ne j\). Mathematically, \(G\) is expressed as:

Here, \(n\) is the total number of datasets, \(p\) is the total number of models and \(\text {Accuracy}_{M_k}(D_j \mid D_i)\) is the accuracy of the model \(M_k\) when it is trained on dataset \(D_i\) and tested in dataset \(D_j\). (This formulation simply gives an average of the performance of all models by considering all the possible train-test data splits.). Such notation for example \(D_j \mid D_i\) means that the model \(M_k\) is trained on dataset \(D_i\) and evaluated on \(D_j\). Big values of \(\text {Accuracy}_{M_k}(D_j \mid D_i)\) in turn suggest the presence of related information generalization, which means the model which has learned non-sensitive or transferable features. Generalizability analysis between datasets is important because, in real-world uses of cybersecurity systems, environments are diverse and constantly changing. For example, a model learnt on one network environment can be required to switch to an environment with a different pattern. Generalization demonstrates how well the model is capable of addressing such variations without the need for new training. This metric becomes especially important when the datasets are dissimilar regarding the types of attacks, traffic patterns or features. High generalization ensures that the model does not fit a certain predetermined data set and instead can be used in ordinary, realistic exercises.

The optimization problem is subject to three primary constraints: training time, computational resources, and adversarial robustness. These constraints ensure that the models operate within practical limits while maintaining their effectiveness and robustness against adversarial attacks. The training time constraint ensures that the time required to train a model \(M_j\) on a dataset \(D_i\) does not exceed a predefined maximum allowable time \(T_{\text {max}}\). This can be expressed as:

Here, \(T(M_j, D_i)\) is the training time of model \(M_j\) on the dataset \(D_i\). This constraint is important for the practical application of these algorithms because training time must be kept to a minimum due to the availability of resources or operational time constraints. The resource bound makes sure that the computational resources used in training and inference are below a certain limit of resources \(R_{\text {max}}\). This is given as:

where \(R(M_j, D_i)\) are the computational resource consumption like memory, CPU, or GPU used when training model \(M_j\) on data set \(D_i\). This constraint is useful for tweaking models for deployment on environments that are impoverished in terms of computational resources, for instance on edge devices or on the mobile platform. The adversarial robustness constraint insulates for adversarial perturbation \(\epsilon\), which is added to the input data \(x\), from a maximum permissible bound \(\delta\). This is represented as:

Where \(\Vert \epsilon \Vert\) is some norm of the perturbation vector (e.g. the \(\Vert \cdot \Vert _2\)-norm). This constraint ensures that the used perturbations in adversarial scenarios make practical sense and do not surpass a certain limit which serves as the evaluation’s integrity. Altogether, these constraints keep the overall optimization problem solvable and implementable while trying to capture the essence of performance, resource usage, and robustness in real-world cyber-security scenarios.

The final optimization problem consolidates the objectives of maximizing performance, minimizing adversarial vulnerability, and enhancing generalizability. It combines the metrics into a single objective function \(J\), while adhering to constraints on training time, computational resources, and adversarial robustness. This ensures that the solution is practical, scalable, and robust for real-world cybersecurity applications. The weights \(\alpha\), \(\beta\), and \(\gamma\) in the resulting objective function were tuned empirically (via a grid search algorithm) and so as to maximize the performance of the trained model on the validation set subject to the constraints of using the available resources. These parameters regulate the relative weighting of performance, adversarial robustness and generalizability in the composite objective \(J\). The stability of the sensitivity analysis has also been checked, such that modification of a parameter maintains other parameters constant and determines the approximate variation in objective value \(J\) in ensuring that the optimization is not unduly weighted to any one metric. The objective function is designed as:

where \(\alpha , \beta , \gamma\) are weight coefficients, assigned to embrace a performance measure, adversarial robustness and generalizability, respectively. Accuracy, Precision, Recall are standard evaluationcriteria of how the model is functioning to respond to the dataset. The indicator function \({\mathbb {I}}(M_j(x + \epsilon ) \ne y)\) denotes the fact that the model \(M_j\) incorrectly classifies the input vector \(x + \epsilon\) . Lastly, \(\text {Accuracy}_{M_k}(D_j \mid D_i)\) measures the cross dataset performability of a model built from dataset \(D_i\) and tested on dataset \(D_j\). This formulation provides a comprehensive and balanced approach to optimizing deep learning models for cybersecurity tasks, making it adaptable to diverse datasets and dynamic threat environments.

Proposed algorithm for cybersecurity solutions

The algorithm 1 begins its process by setting critical parameters (\(\alpha , \beta , \gamma\)) to optimize security performance as well as system reliability and overall model adaptability. Preprocessing steps include standardizing features while implementing SMOTE for class balance management and new cyber threat insertion to strengthen datasets’ overall robustness. Preprocessed datasets create inputs for model training through the combination of hyperparameter tuning techniques (Grid Search or Bayesian) and regularization techniques (dropouts). The evaluation framework determines model performance through accuracy computation and FPR assessment together with precision recall along with F1-score. Moreover, adversary resistance testing is evaluated by creating adversarial examples and measuring model robustness to those perturbations (including FGSM). The framework determines scalable models by performing cross-dataset tests to measure universal model applicability. The optimization step achieves maximum outcome by using \(J = \alpha P - \beta A + \gamma G\) as an objective function which combines model performance metrics with adversarial vulnerability measures alongside generalizability analysis. The real-time deployment of this framework demonstrates its effectiveness against cybersecurity risks, particularly DDoS and botnet attacks.

The first sub-algorithm 2 step applies three principal preprocessing techniques, which combine standardization/scaling procedures with SMOTE implementation and emerging threat simulation for developing trained datasets effectively. The second sub-algorithm 3 evaluates model performance by extracting confusion matrix metrics to measure adversarial vulnerability through generated adversarial examples (e.g. FGSM) and ensures robust evaluation criteria. These algorithms form an integrated pipeline that develops and optimizes cybersecurity solutions that simultaneously deliver secure deployment together with adaptability. The flow chart ofthe proposed algorithm is given in Fig. 4

Experimental setup

To accelerate and speed up training, the trials were run on a computer with an NVIDIA GPU installed. 70% of the datasets were used for training, 15% for validation, and 15% for testing. Feature normalization and redundant data reduction were two preprocessing procedures. The deep learning models were implemented and trained using TensorFlow and Keras, with grid search being used to optimize the hyperparameters. Table 2 summarizes the key characteristics of each dataset:

NSL-KDD Dataset In order to address a number of problems, including duplicate records and the over-representation of particular classes, the KDD Cup 1999 dataset was refined to form the NSL-KDD dataset49. By today’s standards, it is a relatively tiny and compact dataset with 125,973 samples and 41 characteristics. Four major categories comprise the attack types provided in NSL-KDD: DoS (Denial of Service), R2L (Remote to Local), U2R (User to Root), and Probe. These attack categories, which concentrate on conventional cyberthreats that were common in the late 1990s and early 2000s, are somewhat elementary. The features in NSL-KDD are mostly low-level attributes derived from TCP/IP headers and include information such as protocol type, service, flag, source bytes, and destination bytes. The dataset’s compact size makes it computationally efficient to work with, but it does not fully represent modern attack patterns or network behaviors, which limits its applicability in contemporary cybersecurity research. Since NSL-KDD is largely synthetic, the traffic patterns it contains do not always reflect the complexity and variability of real-world network traffic. NSL-KDD is light and energy-saving, and therefore it can be used by low-resource nodes in WSN. But its simulation and state-of-the-art attack profiles, and lack of time-series data, diminish its utility in the real-world latency-sensitive WSN deployments. It is not a good model to generalize to contemporary threats, but it does well in prototyping. We conducted a pairwise statistical test on the Accuracy and F1-Score values on the five independent runs based on the Student s t -test. In the case of CNN vs. LSTM in CICIDS2017, the F1-Score difference was also significant (\(p < 0.01\)) and it proves that CNN can outpredict LSTM. Figure 4 above does the same tests on CTU-13, and found SVM and Logistic Regression to be nearly identical in their behavior over sparse attacks (\(p = 0.28\)).

CICIDS2017 Dataset With 3,119,345 samples and 85 characteristics, the CICIDS2017 dataset is far larger and more detailed than NSL-KDD. It is intended to mimic real-world network traffic33. There are 15 attack types in the dataset, including both classic and contemporary attack types, including DoS/DDoS, Brute Force, Heartbleed, Web Attacks, Infiltration, and Botnet. The focus of CICIDS2017 is on simulating various attack scenarios over several days by utilising actual network settings and traffic patterns. The features in CICIDS2017 are more comprehensive than those in NSL-KDD and include both flow-level and packet-level attributes. These features cover various aspects of network traffic, such as flow duration, total Fwd/Rev packets, average packet size, and Fwd IAT mean, providing a richer context for deep learning models to identify both volumetric and subtle attacks. The real nature of the data makes CICIDS2017 highly relevant for modern intrusion detection systems (IDS), but the dataset’s large size can pose computational challenges, especially for resource-constrained environments. CICIDS2017 provides realistic, varied attack scenarios but it is large and, therefore, has significant memory and energy requirements because of its features. Direct implementation on the usual WSN nodes is not viable, and it needs offloading or model compression to be implemented on the edge, despite its potential in modelling the modern threats.

UNSW-NB15 Dataset The UNSW-NB15 dataset contains 2,540,044 samples and 49 features, positioning it between NSL-KDD and CICIDS2017 in terms of both size and complexity49. The dataset was generated using a hybrid approach, combining real network traffic with synthetic attack traffic. UNSW-NB15 represents 9 different attack types, including Fuzzers, Analysis, Backdoors, DoS, Exploits, Generic, Reconnaissance, Shellcode, and Worms. These attack types cover both traditional and modern threats, making the dataset a good candidate for evaluating a variety of intrusion detection methods. The features in UNSW-NB15 strike a balance between the simplicity of NSL-KDD and the detail of CICIDS2017. Key features include attributes like service, state, sload, dload, stcpb, and dtcpb, which provide insights into the behavior of the traffic at both the flow and session levels. The combination of real and synthetic data makes UNSW-NB15 more versatile and representative of real-world conditions than purely synthetic datasets like NSL-KDD, but it also requires careful preprocessing to avoid overfitting to the synthetic components. UNSW-NB15 has trade-offs between realism and scalability, moderate resource requirements, and thus can be used in fog-enabled WSNs. Its hybrid traffic and its manageable scale allow implementation with little performance optimization, which creates a sensible compromise between model performance and the possibility of deployment.

CTU-13 Dataset One way that the CTU-13 dataset differs from the others is that it is nearly entirely dedicated to botnet traffic. It has 16 characteristics and a large 12,392,796 samples29. The dataset consists of real traffic that was recorded in a controlled setting after botnets were incorporated into regular traffic patterns. This dataset offers a wealth of information about botnet communication protocols, infection patterns, and attack strategies, making it very helpful for researchers researching botnet behaviours and detection techniques. CTU-13 features are somewhat simpler than those of CICIDS2017 and UNSW-NB15. They include attributes such as source IP, destination IP, source port, destination port, protocol, and timestamp. While this simplicity allows for efficient data processing, it also limits the dataset’s applicability to more general cybersecurity tasks, such as intrusion detection or advanced threat hunting. However, for studies focused specifically on botnet detection, the real-world traffic in CTU-13 provides valuable insights into the behavior of these sophisticated threats. Although CTU-13 contains plenty of botnet exhibits, the database is data sparse and consumes a lot of memory. Its rank temporal resolution and unbalancing do not allow it to be richly useful in real-time low-resource WSN scenarios, but it is better designated to be simulated rather than applied in practice.

The use of a dataset to deep learning models is highly dependent on its size and feature richness. For example, CICIDS2017 offers a richer data environment for complicated deep learning models like Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) and Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), which thrive on large datasets with detailed characteristics, because of its larger feature set and real traffic. The flow-level information in the dataset can help these algorithms identify more covert infiltration efforts as well as volumetric attacks (like DDoS)33. But because of its vastness, the dataset might need a lot of processing power to train and test models, which would make it less appropriate for settings with low hardware. In contrast, NSL-KDD is well-suited for initial proof-of-concept studies or for researchers with limited computational resources, given its smaller size and relatively simple feature set. However, its synthetic nature and outdated attack types make it less applicable for real-world cybersecurity tasks today. Models trained on NSL-KDD may perform well in controlled environments but may not generalize effectively to modern networks or novel attack vectors49. UNSW-NB15 offers a balance between size and feature complexity, making it a good candidate for training deep learning models that need to generalize across multiple attack types while remaining computationally feasible. Its hybrid approach–combining real traffic with synthetic attacks–allows for a more balanced evaluation of IDS systems, although the presence of synthetic data still necessitates careful model validation to ensure generalization beyond the dataset49. Finally, CTU-13, with its focus on botnet detection, is ideal for specialized deep-learning models targeting botnet behaviors. The dataset’s large size and real traffic provide a rich source of data for training models to detect botnets, but its narrow scope may limit its usefulness for broader cybersecurity tasks29.

Table 3 discuss the suitability matrix of different dataset.

Result and discussion

In terms of accuracy, the CNN model did the best on CICIDS2017, scoring 95.7%, whereas it only scored 89.2% on NSL-KDD. With time-series data such as UNSW-NB15, LSTMs outperformed with an accuracy of 92.3%. On the other hand, the complexity of botnet traffic in the CTU-13 dataset was a difficulty to all models, with the highest accuracy only reaching 78.4%. The bar chart in Fig. 5 illustrates the performance comparison of different datasets–NSL-KDD, CICIDS2017, UNSW-NB15, and CTU-13–across five key evaluation metrics: The metrics used are: Accuracy, Precision, Recall, F1-Score, False Positive Rate (FPR). For all five classifiers, CICIDS2017 always presents the highest performance in terms of Precision, approximately 88% and F1-Score closely below 95% which shows that the CICIDS2017 has good ability for the classification. The outcome of the experiment is moderate, the Accuracy about 70% and the Recall is about 75%, that means balanced detection. The results of the UNSW-NB15 dataset are lower and have fluctuations of around 65% in features like Precision and F1-Score which indicates that it becomes tough to differentiate the attacks clearly. The CTU-13 dataset also retains higher values of Precision approximated to 75% and FPR approximated to 85% meaning good detection capability though with false alarms. Here, the focus is on the performance of the given dataset with a focus on the lesson that choice of dataset is a critical component of model assessment.

The confidence intervals in Table 4 indicate consistent results with various training runs, particularly at the bigger and more varied CICIDS2017 dataset.

In order to measure the quality of the SMOTE-based preprocessing operation sparing solution, we performed an ablation study by comparing how the CNN model performed on the NSL-KDD dataset with and without SMOTE. The findings indicate that the F1-Score and Recall, which are highly important with respect to intrusion detection in the imbalanced cases, have improved significantly.

As per the Table 5 the increase in F1-Score (+6.8%), proves that the incorporation of SMOTE into our preprocessing pipeline was justified by the improvement in dealing with minority classes.

The bar chart in Fig. 6 presents a comparative analysis of Accuracy, Precision, Recall, F1-Score, and False Positive Rate (FPR) for four datasets: We test our model on NSL-KDD, CICIDS2017, UNSW-NB15, and CTU-13 datasets using an Ensemble Model. It is assessed for the CICIDS2017 dataset that the highest level of performance refers to Accuracy with 88% as well as F1-Score with 92%, which proves its further classification potential. The NSL-KDD dataset keeps up the accuracy here with Accuracy at 82% and Recall has a high detection rate at 90%. Alternative UNSW-NB15 is not as outstanding but the performance is reasonable getting to 80% Accuracy coupled with 85% F1-Score proving the model’s consistency in its predictions. On the other hand, the dataset of CTU-13 has a higher FPR about 94%, it has more false alarms while has accuracy 78% and precisions about 70%. This analysis shows that the Ensemble Model can work on different datasets with high accuracy although revisions are desirable to increase recall and decrease false positive outcomes.

The bar chart in Fig. 7 shown below presents a comparison of the Accuracy, Precision, Recall, F1-Score, and False Positive Rate (FPR), derived by testing an algorithm K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN) on four datasets; namely NSL-KDD, CICIDS2017, UNSW-NB15, and CTU-13. Among all the datasets, UNSW-NB15 has the best Accuracy (90%) followed by CTU-13 ( 85%). For Precision, only UNSW-NB15 with 85% shows a higher classification while NSL-KDD with 60% show lower effectiveness in categorizing true positive instances. For Recall, CICIDS2017 has the highest value 88%, followed by UNSW-NB15 at 90% ,which demonstrates that they strongly identify the actual threats while CTU-13 has the lowest at around 75%. F1-Score combining Precision and Recall is the highest at UNSW-NB15 at about 92% and lowest at NSL-KIDD at 78%. Last but not the least, the FPR values comment that CTU-13 dataset has higher false positive ratio, which is approximately at 85% while NSL-KDD at around 65%. As for the result evaluation, this analysis reveals that KNN attains a high level of accuracy of UNSW-NB15 while confronts problems in precision and appearing false positive in others datasets.

The bar chart of Fig. 8 depicted the Accuracy, Precision, Recall, F1-Score and FPR of LSTM using four datasets namely NSL-KDD, CICIDS2017, UNSW-NB15 and CTU-13. Maximum Accuracy of approximately 92% was observed for the CTU-13 dataset, while the minimum (64%) was observed for NSL-KDD dataset, which shows large difference in the detection characteristics. During Precision, CTU-13 has the highest score of 90%, while NSL-KDD scored the lowest of 65% indicating that it.Worse from this perspective because it was least accurate in classifying the positive instances. NSL-KDD and UNSW-NB15 achieve high Recall scores (85%) in order to detect more actual threats while CICIDS2017 has the lowest Recall (70%). Since F1-Score is the trade off between Precision and Recall, it stays high for UNSW-NB15 at about 88% and low for CICIDS2017 at 68% . At the end, false positive rates show that UNSW-NB15 (95%) has the highest FPR while CICIDS2017 (70%) has low FPR that make make it more effective in avoiding false positives. The results show that LSTM renders high selectivity on CTU-13 as compared to NSL-KDD owing to lower precision.

The bar chart of figur 9 above shows Accuracy, Precision, Recall, F1-Score, and FPR based on four datasets, including NSL-KDD, CICIDS2017, UNSW-NB15, and CTU-13 using Logistic Regression model. Accuracy of the classifiers are quite moderate where CICIDS2017 attains the highest Accuracy (87%) and CTU-13 is the second one (78%) Whereas NSL-KDD attains the minimum one (68%). NSL-KDD set has the highest level of precision (72%) compared to UNSW-NB15 (74%) indicating higher reliability in identifying true positives, CTU-13 (59%) and NSL-KDD (59%) have the least. It is noticed that the highest Recall value has been recorded for NSL-KDD (92%) implying better detection of actual attacks while the lowest Recall (65%) has been observed for UNSW-NB15 implying missed out attacks. Both Precision and Recall just inversely relate with each other, hence, F1-Score remains highest for CICIDS2017 (88%) while the F1-Score for UNSW-NB15 remains low (66%). The FPR is again higher for NSL-KDD (85%) which classifies more as false positives, while CICIDS2017 shows the lowest (65%) FPR which represents better precision. They test different classifiers; however, they find that the logistic regression algorithm yields the best results on the CICIDS2017 dataset, while it provides one of the worst results on the NSL-KDD dataset due to the high false positive ratings.

The bar chart at Fig. 10 presents the findings of Accuracy, Precision, Recall, F1-Score, and the False Positive Rate for Naïve Bayes model on datasets of NSL-KDD, CICIDS2017, UNSW-NB15, and CTU-13. The CTU-13 dataset has the best Accuracy (85%), then UNSW-NB15 (82%), otherwise, NSL-KDD (72%) has less accuracy, marking a moderate classification. CTU-13 appear to have the lowest percentage of false positive (87%) while NSL-KDD has the highest percentage of misclassified instances (65%). NSL-KDD has the first recall rates closest to 95% meaning most threats are likely to be depicted, while CICIDS2017 has the worst recall rates of the lot 68% meaning attacks are likely to be missed. F1-Score is at its best for UNSW-NB15 (83%) and at its low for CICIDS2017 (69%) which explains an unequal Precision/Recall balance. Finally, FPR values also shows that NSL-KDD dataset (93%) gives highest false positive rate compared to others results while CICIDS2017(72%) better in suppressing false positives. That is why these results show that: Increasing the proportion of normal network traffic in a set, while Naïve Bayes has high recall for NSL-KDD, it has low precision and numerous FPs in practical use.

The bar chart presented in Fig. 11 shows Comparison in terms of Accuracy, Precision, Recall, F1-Score and False Positive Rate for NSL-KDD, CICIDS2017, UNSW-NB15 and CTU-13 datasets using RNN model. CICIDS2017 has the maximum Accuracy of (89%), second is UNSW-NB15(88%) while NSL-KDD has comparatively low Accuracy (62%); which signal a set back in classification efficiency. The highest was obtained for UNSW-NB15 (92% ) confirming good learning of positive instances while NSL-KDD was much lower at (67% ) showing a high misclassification. Finally, recall is strongest for UNSW-NB15 which is at approximately 94% which means that CICIDS2017 performance in instance did capture actual threats, although there is a slightly lower recall at approximately 83%. Here, F1-Score remains highest for UNSW-NB15 (90%) and lowest for NSL-KDD (74%) which shows relative imbalanced trade off between Precision and Recall. Finally, the FPR reveals that CTU-13 (88%) has more fake positives than the others, while CICIDS2017 (75%) has the least, fewer false alerts. These results show that RNN has the high classification accuracy especially for UNSW-NB15 while the model exhibits lower generality especially on NSL-KDD.

The bar chart in Fig. 12 gives the Accuracy, Precision, Recall, F1-Score, and False Positive Rate (FPR) of each of the four data sets NSL-KDD, CICIDS2017, UNSW-NB15, and CTU-13 datasets using the Support Vector Machine (SVM) model. The measured Accuracy shows that SVM has the best performance on CICIDS2017 with Accuracy of 89%, second by NSL-KDD (85%) and the lowest on CTU-13 (63%) proofing that the structured dataset like CICIDS2017 is more suitable for SVM. Accuracy is most notable in CICIDS2017 (0.91 meaning that it has a high capability of endorsing the positive samples’, while UNSW-NB15 is lowest at 0.66 meaning that there are more cases of misclassification. The best result is achieved by UNSW-NB15 with the recall of 0.92, which describes most of the actual threats, whereas, the lowest result is offered by CTU-13 (0.65), which is the highest number of missed attacks. The F1-Score remains highest for CICIDS2017 at 88% for the worst of CTU-13 at 67% shows a poor compromise between precision and recall. Finally, the analysis of FPR values gives information that UNSW-NB15 class is the most contaminated with false positive, equal to 94%, while CICIDS2017 class is the least contaminated with false positive, only 73%. These results point toward the fact that SVM works best for CICIDS2017 at the same time, it suffer from False Positive and Recall issues in UNSW-NB15 and CTU-13 datasets.

The Accuracy, Precision, Recall, F1-Score and FPR of Decision Tree model on four datasets such as NSL-KDD, CICIDS2017, UNSW-NB15 and CTU-13 have been depicted through bar chart in Fig. 13. The Accuracy metric illustrates the highest percentage of 92% of the UNSW-NB15 dataset but lags behind in the CICIDS2017 with 65% of efficiency, showing differences in response toward the detection of datasets. The highest precision value is identified in CICIDS2017 (85%), which presenting the capability of good positive instance detection while the lowest precision is identified in UNSW-NB15 (62%) indicating the possibility of misclassification. Recall is highest in NSL-KDD (90% optimized for threat detection) and CTU-13 has slightly lower percentage (78%). The F1-Score significantly ordered as UNSW-NB15 with the highest score of 91% and the CICIDS2017 with the minimum score of 70% indicate the skewness of the trade-off between Precision and Recall. Last but not least, FPR values demonstrate that NSL-KDD (94%) has a higher tendency of false alarm while CICIDS2017 has 72% in False Positive detection. These findings indicate that Decision Tree has good accuracy on UNSW-NB15; however, it encounters issues with precision and handling of false positives on all the other sets.

The heatmap in Fig. 14 presents the generalizability performance of various machine learning models–Tree, Logistic Regression, Naïve Bayes, SVM, KNN, Ensemble, CNN, RNN, and LSTM–evaluated across four datasets: NSL-KDD, CICIDS2017, UNSW-NB15, and CTU-13. The Decision Tree model is sensitive to all three indicators: accuracy, precision, and recall; achieving the highest performance on UNSW-NB15 (94.6%) yet underperforms on CICIDS2017 with 52.0%. all the nine Data Sets, Logistic Regression gives the highest accuracy on CTU-13 as 94.3% while the least generalization rate to NSL-KDD as 50.8%. Naïve Bayes yields moderate outcomes where its highest generality is on UNSW-NB15 at a 74.4% but lower generality on NSL-KDD at a 58.0%. SVM gets a good average, its best percentage on CICIDS2017 datasets with 85.0% and the least on UNSW-NB15 datasets with a 72.6% percentage. KNN has very high accuracy values on CTU-13 dataset, which is 93.9% and low accuracy on UNSW-NB15 dataset which is 66.5%. The Ensemble model is average on different datasets, achieving the highest percent of 74.6% on UNSW-NB15, and the lowest at 50.8% on CICIDS2017. According to the figures shown above, the performance of CNN demonstrates its impressing adaptability to three datasets of CICIDS2017 (85.0%), UNSW-NB15 (94.0%), and poor performance in NSL-KDD (54.5%). It is observed that, the proposed RNN has achieved the highest accuracy of 82.1% on NSL-KDD dataset and low accuracy of only 59.1% on UNSW-NB15 dataset. LSTM generalizes best to the CTU-13 scenario with an average detection rate of 81.5% while its detection to the CICIDS2017 scenario is 51.9%. This heatmap shows that there is a difference of generated models generalization between various datasets however some models like CNN and Decision Tree are suitable for structured datasets while LSTM and Logistic regression for CTU-13 real-attack scenario.

As Table 6 summarizes, the suggested CNN+RNN model with SMOTE preprocessing and adversarial robust optimization has led to high performance in accordance with standard performance measures compared to other intrusion detection methods in the literature. In particular, the model demonstrated the highest accuracy of 97.4% and the F1-score of 96.1%, surpassing the outcomes of models using Transformers (Kulkarni et al., 2025) and GAN-enhanced frameworks (Kale et al., 2022). This affirms the effectiveness of our ensemble an optimization strategy in generalizing the capture of intrusion patterns that are also complex.

The cross-dataset test shows that models, especially CNNs, do not generalize well on other datasets, and the accuracy drops significantly when they are trained on NSL-KDD and tested to the point where the accuracy decreases sharply to 54.5% compared to 85.0% with in-distribution datasets such as CICIDS2017. This loss in performance is mostly attributed to the fact NSL-KDD is artificial and outdated compared to real-world data such as CTU-13, and it does not contain the temporal and contextual complexity that such data does or the CNNs have overfitted on low-level inputs that do not transfer well. In the same fashion, it is possible to see overfitting in models trained on smaller or imbalanced datasets as when high recall is frequently paired with an out-of-proportion false positive rate, as is true in 85% FPR on NSL-KDD when Naive Bayes was used. In order to overcome these generalization and sensitivity challenges, techniques, including dropout tuning, batch normalization, and transfer learning on more labelled data, e.g., CICIDS2017, will help. Also, there are domain adaptation techniques such as domain adversarial neural networks (DANN) and meta-learning techniques that can make models more robust and adaptive to diverse and changing WSN conditions, which makes them perform better in real-world diverse and evolving cybersecurity practice.

In order to confirm the novelties and performance of our proposed framework, we used ablation experiments, that bias out specific components of the framework. This can be confirmed by a reduction of 4.3 per cent in F1-score when the adversarial training module was removed (Table 7) and thus such a module is essential to achieve greater robustness. In the same way, the recall was poor without SMOTE because of wrong proportions between classes. In comparison to the literature, the proposed framework is the first, which exploits the following pipeline: (i) balancing the number of classes with SMOTE, (ii) deep spatio-temporal feature learning with CNN-RNN fusion, and (iii) deep model regularization with adversarial defense. This integration allows high accuracy combined with flexibility in energy-limited, latency-sensitive WSNs settings; both features that are not simultaneously considered in previous literature. Further in order to confirm our findings we conducted a paired t-tests to evaluate our frameworks F1- score against a number of recent intrusion detection methods. Based on Table 8, our model improves significantly, and all of its p-values lie less than 0.05. These findings testify that the obtained performance improvements are not merely random and caused by the variance in the datasets.

Conclusion and future work

The paper gives a comprehensive outline of Wireless Sensor Network (WSN) Security through employing the various deep learning techniques for intrusion and threats detection and prevention and compares four common cybersecurity datasets; NSL-KDD CICIDS2017, UNSW-NB15 and CTU-13 to determine their efficacy in deep learning based security models. The analyses suggest that CICIDS2017 is the most comprehensive dataset owing to genuine network traffic, the wide range of attacks, and its enormous scale, which makes the dataset suitable for modern IDSs despite high computational complexity. Even though NSL-KDD is easy to manage, it is both outdated and synthetic in nature, which does not make it very useful for examining modern network traffic, while UNSW-NB15, which is a mixture of both real and synthetic traffic, is a very good middle ground, making it a prime candidate for a wide spectrum of different cybersecurity uses. CTU-13 is particularly important in analyzing botnet activity and not very useful for intrusion detection in general. The study also assesses Deep Learning Models as CNN delivered high sensitivity on CICIDS2017 at 95.7% but low performance on NSL KDD while LSTM performed well with 92.3% accuracy on temporal data sets such as UNSW NB15 but low figure on structured data set. Decision Tree turned out be best on UNSW NB15 at 94.6% while SVM provided high result on CICIDS2017 Moreover, we observed that both KNN and Logistic Regression models had higher false positives rates and that Naïve Bayes achieved high recall of NSL-KDD but was accompanied by low precision and high false positives. To address this problem, the study formulates a mathematical framework for maximizing deep learning cybersecurity solutions while arguing that choosing the right dataset for cybersecurity model training is crucial and that no dataset is perfect for all tasks.

Future directions of this research focus on several important directions in developing WSN security and deep learning-based cybersecurity. Dynamic dataset generation is a critical component for building new cybersecurity datasets that can mimic actual network traffic, present today’s more sophisticated attacks, and newly emerging threats such as fileless malware, and ransomware among other which are also ever changing, and growing datasets, that are dynamically updated with real time threat intelligence. Some of the future work includes further investigation using a hybrid deep learning model of CNN and RNN, as well as utilizing other Transformer-based models such as BERT for cybersecurity logs as part of enhanced detection accuracy. To develop adversarial defense mechanisms, future work must apply newer forms of adversarial training to teach deep learning models to be impermeable to evasion attacks as well as apply feature hardening approaches to investigate adversarial inputs prior to classification. The main and most important approach to WSN security through edge computing to solve the problem of AI models’ inability to be applied to resource-constrained environments at real time is to implement AI models, specially developed for lightweight devices. To enhance the generalization of the model and to reduce the dependence on a single set of data, two novel directions can be incorporated: cross-dataset learning and transfer learning. To enhance the distributed and private intrusion detection, federated learning can also be applied. In order to make deep learning based cybersecurity models more interpretable, there are different XAI (Explainable AI) methods that can be applied to significantly improve the explainability and traceability of the implemented solutions. Moreover, real-world deployment and evaluation of these models for different WSN environments in real cybersecurity scenarios will ensure the practical efficacy of WSNs along with building and standardizing benchmarking evaluative frameworks for different cybersecurity datasets and models. With respect to these future directions, the cybersecurity community can advance WSN security, apply deep learning approaches in practice, and design stronger and more robust threat detection against future generations of cyber threats. To assist reproducibility and enable standardized benchmarking of intrusion detection in Wireless Sensor Networks, we suggest creating hybrid datasets, which use the strengths of consolidated benchmarks such as NSL-KDD, CICIDS2017, CTU-13, and UNSW-NB15. The proposed sets of data must contain realistic and various attack patterns, annotation of energy consumption profiles of every sample as well as history of time that signify real-life event sequences. Not only would this benchmark likely reflect current threat environments but also support the restrictions that will be imposed by WSN environments, most notably resource constraints and latency-sensitivity of operation. By potentially closing the gap (in a temporally rich and energy-efficient way) between the synthetic network traffic and the real one, it will become possible to develop more reliable assessments of the deep learning models used to provide security to WSNs.

Data availability

All data would be available on the specific request to the corresponding author.

References

Bajaj, K., Sharma, B. & Singh, R. Integration of wsn with iot applications: a vision, architecture, and future challenges. In: Integration of WSN and IoT for Smart Cities, pp. 79–102 (2020).

Jebur, T. K. Securing wireless sensor networks, types of attacks, and detection/prevention techniques, an educational perspective. ASEAN J. Sci. Eng. Educ. 4(1), 43–50 (2024).

Ivanov, A. Security in wireless sensor networks. In 6th International Conference on Governance and Strategic Management (ICGSM) “ESG Standards and Securing Strategic Industries” (2024).

Kumar, Sunil, et al. An optimized intelligent computational security model for interconnected blockchain-IoT system & cities. Ad Hoc Networks 151, 103299 (2023).

Tripathi, K., Agarwal, D. & Krishen, K. An integration approach of an iot and cyber-physical system for security perspective. In Handbook of Research of Internet of Things and Cyber-Physical Systems, pp. 187–218 (Apple Academic Press, 2022).

Alturki, N. et al. An intelligent framework for cyber–physical satellite system and iot-aided aerial vehicle security threat detection. Sensors 23(16), 7154 (2023).

Patel, Ankit D., et al. Security trends in internet-of-things for ambient assistive living: a review. Recent Advances in Computer Science and Communications (Formerly: Recent Patents on Computer Science). 17(7), 18–46 (2024).

Sikder, A. K. et al. A survey on sensor-based threats and attacks to smart devices and applications. IEEE Commun. Surveys Tutor. 23(2), 1125–1159 (2021).

García, A.C., et al. New Building Management Systems for Smart Cities: A Brief Analysis of Their Potential. Manuscript (2025).

Sirajuddin, M. et al. A secure framework based on hybrid cryptographic scheme and trusted routing to enhance the qos of a wsn. Eng. Technol. Appl. Sci. Res. 14(4), 15711–15716 (2024).

Anyaso, K., Peters, N. O. & Akinboro, S. Transforming animal tracking frameworks using wireless sensors and machine learning algorithms. World J. Adv. Res. Rev. 24(1), 996–1008 (2024).

Pandey, Vivek Kumar, et al. An Efficient and Robust Framework for IoT Security using Machine Learning Techniques. Proc. Comp. Sci.. 258, 118–124 (2025).

Gangwani, P., Perez-Pons, A. & Upadhyay, H. Evaluating trust management frameworks for wireless sensor networks. Sensors 24(9), 2852 (2024).

Mitra, A. & Das, S. Leveraging ai-enabled wsns for environmental monitoring. In Wireless Ad-hoc and Sensor Networks: Architecture, Protocols, and Applications, p. 214 (2024).

Kuppuchamy, S.K., et al. Journey of computational intelligence in sustainable computing and optimization techniques: An introduction. In Computational Intelligence in Sustainable Computing and Optimization, pp. 1–51 (Morgan Kaufmann, 2025).

Fahmy, H. M. A. Wsns applications. In Concepts, Applications, Experimentation and Analysis of Wireless Sensor Networks, pp. 67–242 (Springer, 2023).

Aqeel, I. Enhancing security and energy efficiency in wireless sensor networks for iot applications. J. Electr. Syst. 20(3s), 807–816 (2024).

Moslehi, M. Exploring Coverage and Security Challenges in Wireless Sensor Networks: A Survey. Available at SSRN 5084663 (2024).

Akram, Junaid, et al. Galtrust: Generative adverserial learning-based framework for trust management in spatial crowdsourcing drone services. IEEE Transactions on Consumer Electronics. 70(3), 6196–6207 (2024) .