Abstract

This study aimed to evaluate the impact of flight simulator training on the enhancement of perceptual-motor skills among flight cadets. Perceptual-motor skills act as a crucial link through which pilots translate their environmental perceptions into precise maneuvers, a capability that is particularly vital in dynamic and unpredictable flight environments. A total of forty cadets participated in the experiment and were randomly assigned to either the Traditional Training Group (TTG) or the Efficient Training Group (ETG). The TTG received individual training on training aircraft under the supervision of an instructor, while the ETG trained on expert aircraft using a full-scenario memory replay training system enhanced with multimodal information feedback. The simulations were conducted at the Aeronautical University simulation laboratory, configured as a self-developed Flight Skill Accelerated Training Simulator. Both groups completed eight weeks of simulated flight training, which included testing scenarios such as takeoff, flight control, landing, and carrier landing. Results indicated that the ETG outperformed the TTG in the takeoff, flight control, landing tasks, and carrier landing tasks. Furthermore, the ETG demonstrated a faster training pace across all tasks. These findings suggest that our independently developed accelerated flight skills training system can effectively expedite motor skill acquisition among flight cadets, enhance flight performance, and holds promising potential for broad application in various flight training contexts.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

As aviation technology continues to advance42,43 the demand for efficient pilot training is steadily increasing. However, traditional flight training methods are becoming increasingly inadequate1,2,3. These conventional approaches, which often rely on lengthy, repetitive practice sessions, fail to address the evolving needs of modern aviation training. A significant limitation is their focus on mechanical repetition, which can result in the cadets practicing incorrect techniques over extended periods. This not only increases training duration but also diminishes motivation and learning efficiency4,5. Moreover, traditional methods often fail to foster autonomous learning, a crucial skill in modern aviation where pilots must adapt quickly to dynamic flight environments6. As a result, these methods struggle to meet the growing demand for more agile, adaptable, and effective training approaches. Consequently, the development of more efficient and flexible training systems has become a critical priority in the field of flight education7.

Perceptual-motor refers to the process through which individuals enhance their ability to detect, recognize, and categorize environmental stimuli through experience and practice8,9,10. This theory posits that perceptual abilities are malleable and can be improved through sustained training and exposure11,12. In the context of aviation, perceptual-motor is critical, as it enables pilots to develop the necessary skills to quickly interpret and respond to dynamic and complex flight environments13,14,15,16,17,18,19. Numerous studies have shown that perceptual-motor significantly enhances pilots’ ability to perceive and react to environmental cues, thereby improving their decision-making and reducing the likelihood of flight accidents20. Integrating perceptual learning techniques into flight training programs can lead to better outcomes, particularly in high-stress, unpredictable scenarios where quick, accurate decision-making is essential21.

Multimodal information feedback technology integrates multiple sensory channels—such as visual, auditory, and tactile—to deliver comprehensive feedback, thereby enhancing users’ perception and understanding of information19. This technology aims to improve task execution by providing feedback through different sensory modalities, leading to more efficient and effective performance. In aviation training, this approach is particularly valuable as it helps pilots better perceive and respond to dynamic flight conditions22,23,24. For example, Li et al. (2020) demonstrated that overlaying terrain information on flight displays significantly enhances pilots’ ability to perceive and understand environmental data, thereby improving both operational efficiency and flight safety25. The integration of multimodal feedback technologies with perceptual learning theories offers exciting new possibilities for flight skills training, optimizing the training process, enhancing learning efficiency, and reducing the time required to master critical flight maneuvers.

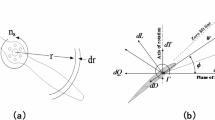

Flight skills require intricate coordination between the brain and the body, falling within the realm of perceptual-motor, as illustrated in Fig. 1. Pilots develop these skills by processing and interpreting visual, auditory, and kinesthetic cues, which are synthesized by the brain to produce accurate behavioral responses. Training emphasizes the precise control and synchronization of muscle movements, leveraging sensory feedback to fine-tune actions in response to varying flight conditions and scenarios. To effectively apply their skills, pilots must rapidly adapt and make decisions in complex, dynamic environments, ensuring optimal performance under pressure17,26.

Mirror neurons play a crucial role in the restructuring of brain circuits through an internal imitation mechanism. They encode motor information as action memories within the brain through observation and learning. When actions are observed, mirror neurons activate corresponding regions responsible for executing these stored movements, effectively linking the observer to the performer. This mechanism facilitates the execution, imitation, and learning of motor skills by enabling individuals to learn through observation, enhancing both skill acquisition and performance27,28,29,30,31.

Directly providing correct behavioral templates—specifically, the standard actions of expert pilots—can significantly reduce the number of corrective attempts and associated costs, thereby reinforcing the correct learning pathway. In this study, we developed a flight skills acceleration training system aimed at expediting the learning process. This system integrates perceptual learning theory with multimodal information feedback technology. It records videos and action data of expert pilots demonstrating standard procedures in typical flight scenarios. These recordings are then used as accurate behavioral templates for novice cadets. The templates serve as practical examples that effectively guide the training process, enhancing skill acquisition and performance.

To evaluate the effectiveness of this approach, 40 flight cadets were randomly assigned to either the traditional training group or the efficient training group. The traditional training group received theoretical instruction followed by practice with flight simulators. In contrast, the efficient training group utilized the flight skills acceleration training system, where they were initially exposed to the standard actions of expert pilots before engaging in theoretical instruction and simulator practice. Both groups completed an 8-week simulated flight training program, during which their flight skill performance were compared and analyzed.

Methods

Participants

We recruited 40 male flight cadets aged between 18 and 25 years from the Aeronautical University. All participants were right-handed, had normal vision (either uncorrected or corrected), and were free from any physical or mental disorders. The cadets were randomly assigned to one of two groups: the traditional training group (n = 20) and the efficient training group (n = 20). Prior to the experiment, all participants were informed about the study’s purpose and signed an informed consent form. A sensitivity analysis conducted using G*Power software indicated that, with a power level of 0.95 (1 - β), a significance level of 0.05 (α), and a correlation coefficient (r) of 0.5 between repeated measures, the detected effect size (f) for a 2 × 8 repeated-measures ANOVA was greater than 0.1932. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and received approval from the Ethics Committee of Sports Science at Beijing Sport University (Approval Number: 2023076 H).

Experimental design and procedure

A mixed double-blind experimental design was employed, incorporating a 2 (training method: traditional training, efficiency training) × 8 (measurement times: baseline and seven post-training flight task assessments) framework. In this design, the training method acts as a between-subjects factor, while the measurement times serve as a within-subjects factor.

The stimulus materials consisted of four flight tasks from DCS World Steam Edition (https://store.steampowered.com/app/223750/DCS_World_Steam_Edition/). Developed by the Russian company Eagle Dynamics, Digital Combat Simulator (DCS) World is a sophisticated flight simulation software that offers an immersive flying experience through detailed simulations of flight control, aerodynamic performance, avionics systems, and damage management. The platform’s high level of realism accurately reflects the behavior of various aircraft models under different flight conditions. Additionally, it features intricate sound simulations and complex damage models, which provide comprehensive emergency handling training for cadets in extreme scenarios. Two aircraft models were utilized in this experiment: the Su-25T Frogfoot attack aircraft and the Su-33 Flanker-D fighter jet.

The simulated flight training tasks were categorized into four distinct categories: takeoff, flight control, landing, and carrier landing (see Fig. 2a). The difficulty of these tasks was divided into three levels: A, B, and C.

Level A tasks encompass takeoff and flight control, which involve specific operations, including: (1) activating the onboard power supply, checking instruments, initiating engine start, adjusting flaps, taxiing, aligning with the runway, and accelerating for takeoff; (2) flying from point A to point Z while navigating through designated waypoints, controlling flight altitude and speed, adjusting heading, and maneuvering through specified guide frames.

Level B tasks concentrate on landing, requiring cadets to successfully land the aircraft using three navigation modes: route flying, return to base, and landing.

Level C tasks focus on carrier landings, where cadets must learn to land the Su-33 on a carrier. This process includes entering the HUD landing mode, adjusting flight speed, lowering the landing gear, and executing a go-around if necessary.

The simulations were conducted at the Aeronautical University simulation laboratory, which was configured as a self-developed Flight Skill Accelerated Training Simulator (see Fig. 2b). The novel training system we developed is grounded in the theory of perceptual-motor skills and integrates full-scenario memory replay training technology, enhanced with multimodal feedback. This system enables cadets to autonomously and repeatedly view expert flight videos, stimulating the cognitive processes of the nervous system and facilitating the reproduction of movements. Through this repetition, the system fosters conditioned reflexes, thereby accelerating the transition of motor skills into the automated phase. During simulated flights, cadets can replicate the expert’s perspective and movements, providing a genuine ‘hands-on’ teaching experience. This repetitive training is instrumental in forming muscle memory, which, in turn, expedites the acquisition of motor skills (see Fig. 3).

Multisensory Feedback-Integrated Full-Scenario Memory Replay Training System. This system comprises the following components: ① Flight Simulation: This includes both traditional flight training aircraft and specialized aircraft designed for efficient training. ② Multi-channel Audio-Visual Acquisition Module: This module records the standard movements of expert pilots using audio and multi-angle video, providing both visual and auditory feedback for training purposes. ③ Control Component Kinematic Parameter Acquisition Module: This component collects data on standard maneuver control from expert pilots, offering tactile feedback during training. ④ Electronic Control System and ⑤ Motion Replication: Together, these elements achieve comprehensive audio and video integration, as well as the reproduction of control component motions.

The formal experiment lasted eight weeks and was organized into three distinct phases. Each group participated in 0.5 h of simulation training per session, with a consistent instructor overseeing the entire process to ensure standardized scoring (see Table 1). This arrangement guaranteed that all participants received equal training time on the flight simulator.

The Traditional Training Group (TTG) followed a conventional training method consisting of three phases. In Phase 1, the instructor taught key technical points and demonstrated task movements on the simulator, emphasizing conceptual knowledge derived from the textbook. Phase 2 involved cadets participating in simulator training, during which the instructor provided real-time corrections, hands-on guidance, and immediate feedback. Finally, in Phase 3, cadets conducted simulator training independently.

In contrast, the Efficient Training Group (ETG) implemented a comprehensive memory replay training approach utilizing multimodal feedback. Phase 1 involved cadets initially viewing expert operation videos and replicating the expert’s actions on the training simulator. Subsequently, the instructor taught and clarified key movement points. This phase provided a more realistic and engaging experience for the neural pathways, as cadets observed the video and executed precise movements, thereby enhancing learning transfer. In Phase 2, cadets replicated expert actions on the training simulator while concurrently performing their own tasks, with the instructor providing real-time corrections and feedback. Phase 3 allowed cadets to independently practice on the simulator, recording their own practice videos for comparison and error analysis against the expert’s videos, and receiving timely feedback. Through repeated practice, they gradually mastered the necessary skills.

Data analysis and processing

Initially, descriptive statistics were conducted to assess the performance of the two groups across four flight tasks. Subsequently, independent samples t-tests were performed to evaluate the baseline differences between the groups. Finally, a 2 (training method: traditional training vs. efficient training) × 8 (measurement time: baseline and performance after seven training sessions) repeated measures ANOVA was employed to analyze the post-training evaluation scores. The data were analyzed using SPSS version 27.0 (released in 2020, IBM Corporation). In cases where sphericity was violated, the Greenhouse-Geisser correction was applied to adjust the degrees of freedom and p-values. Post-hoc comparisons were carried out using the Bonferroni method, with significance set at p < 0.05.

Results

Descriptive statistics

Table 2 summarizes the descriptive statistics for the traditional training group (TTG, n = 20) and the efficient training group (ETG, n = 20) across four flight tasks: takeoff, flight control, landing, and carrier landing. These statistics are presented at baseline and at seven post-training test points, with data expressed as mean ± standard deviation.

Baseline differences

The independent samples t-test results indicated no significant differences in flight performance between the TTG and the ETG at baseline across all tasks (see Fig. 4; Table 3): takeoff (t(38) = −1.05, 95% CI [−3.40, 1.08], p = 0.30, Cohen’s d = −0.33), flight control (t(38) = −1.15, 95% CI [−5.23, 1.44], p = 0.26, Cohen’s d = −0.36), landing (t(38) = 0.74, 95% CI [−2.28, 4.89], p = 0.47, Cohen’s d = 0.23), and carrier landing (t(38) = −0.39, 95% CI [−3.14, 2.12], p = 0.70, Cohen’s d = −0.12).

Repeated measures ANOVA

Takeoff task

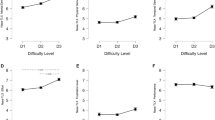

The results of the analysis of variance (ANOVA) for the takeoff task revealed significant main effects for training method (F (1, 38) = 8.59, p = 0.006, η² = 0.18, 95% CI [0.035, 0.362]), measurement time (F (3.01, 114.44) = 140.69, p < 0.001, η² = 0.79, 95% CI [0.753, 0.813]), and a significant interaction between training method and measurement time (F (3.01, 114.44) = 2.59, p = 0.05, η² = 0.06, 95% CI [0.007, 0.095]). Post-hoc comparisons indicated that, The ETG showed significant differences at all time (Ps < 0.04), except for test 1 and 2, as well as test 5 and 3, and test 5 and 4 (Ps > 0.06). For the TTG, no significant differences were observed between the baseline and test 1, baseline and test 2, test 1 and 2, test 5 and 3, 4, 6, 7, and between test 6 and 7 (Ps > 0.08), while significant differences were found at all other time points(Ps < 0.001). These results suggest that, compared to the TTG, the ETG is able to improve takeoff performance more rapidly and overcome the training plateau (see Fig. 5).

Flight control task

The results of the analysis of variance (ANOVA) for the flight control task revealed significant main effects for training method (F (1, 38) = 6.33, p = 0.02, η² = 0.14, 95% CI [0.016, 0.318]), measurement time (F (2.74, 104.28) = 152.45, p < 0.001, η² = 0.80, 95% CI [0.768, 0.825]), and a significant interaction between training method and measurement time (F (2.74, 104.28) = 4.58, p = 0.006, η² = 0.11, 95% CI [0.039, 0.151]). Post-hoc comparisons indicated that, The ETG showed significant differences at all time (Ps < 0.047), except for test 2 and 3, as well as test 4 and 5, where no significant differences were observed (Ps > 0.05). For the TTG, no significant differences were found between the baseline and test 1, baseline and test 2, and test 4 and 5 (Ps > 0.45), while significant differences were observed at all other time (Ps < 0.006). These results suggest that, compared to the TTG, the ETG achieved a rapid improvement in flight control performance after the first training session, whereas the TTG only showed a significant difference from baseline after the third training session (see Fig. 6).

Landing task results

The results of the analysis of variance (ANOVA) for the landing Task revealed significant main effects for training method (F (1, 38) = 20.05, p <0.001, η² = 0.35, 95% CI [0.151, 0.511]), measurement time (F (3.20, 121.75) = 108.55, p < 0.001, η² = 0.74, 95% CI [0.699, 0.772]), and no significant interaction between training method and measurement time (F (3.20, 121.75) = 1.30, p = 0.28, η² = 0.03, 95% CI [0.000, 0.051]). These results suggest that as flight task difficulty increased, both groups showed slower performance improvements (see Fig. 7).

Carrier landing task results

The results of the analysis of variance (ANOVA) for the carrier landing task revealed significant main effects for training method (F (1, 38) = 10.47, p = 0.003, η² = 0.22, 95% CI [0.053, 0.394]), measurement time (F (5.41, 205.42) = 149.64, p < 0.001, η² = 0.80, 95% CI [0.765, 0.822]), and a significant interaction between training method and measurement time (F (5.41, 205.42) = 2.36, p = 0.04, η² = 0.06, 95% CI [0.004, 0.888]). Post-hoc comparisons indicated that, The ETG showed significant differences at all time (Ps < 0.006), except for test 3 and 4, 5, test 4 and 5, and test 6 and 7, where no significant differences were observed (Ps > 0.05). For the TTG, no significant differences were found between test 2 and 3, 4, test 3 and 4, 5, test 4 and 5, and test 6 and 7 (Ps > 0.05), while significant differences were observed at all other time (Ps < 0.018). These results suggest that the TTG is experiencing a plateau in carrier landing performance, making rapid improvement difficult, while the ETG shows significant enhancement in performance (see Fig. 8).

Discussion

This study evaluated the effectiveness of a flight skills acceleration training system using perceptual-motor skills theory and multimodal feedback technology. The results demonstrated that the Efficient Training Group (ETG) significantly outperformed the Traditional Training Group (TTG) across all flight tasks, including takeoff, flight control, landing, and carrier landing. Additionally, the ETG displayed a faster improvement rate across all tasks, indicating that the training system accelerates skill acquisition more effectively than traditional methods.

The proposed flight skills acceleration training system presents significant advancements over traditional flight training methods, which often rely on prolonged, repetitive practice with limited feedback. While conventional flight simulators primarily provide visual feedback, our system integrates multimodal feedback (visual, auditory, and tactile), which has been shown to enhance learning outcomes by engaging multiple sensory pathways23. A key innovation in our system is the use of expert-level templates, where cadets observe and replicate expert flight actions through expert flight videos and motion data reproduction. This fosters autonomous learning, contrasting with traditional methods that heavily depend on instructor-led corrections, thereby slowing progress24. This approach has been demonstrated to improve the efficiency and speed of skill acquisition33. Furthermore, traditional flight simulators are constrained by time and safety concerns, limiting the amount of real-world scenario exposure. In contrast, our system allows cadets to engage in repeated practice across a variety of flight tasks in a safe, controlled environment, thus optimizing training efficiency and accelerating skill acquisition. In conclusion, by combining perceptual learning theory with multimodal feedback technology, our system provides a flexible and adaptive training platform that addresses the limitations of conventional methods. It significantly enhances training outcomes, particularly for complex flight tasks. Future research should focus on further refining the system and evaluating its long-term impact on pilot performance.

The integration of visual, auditory, and tactile feedback in the efficient training group enables cadets to acquire complex skills, such as takeoff and landing, more rapidly and enhances their sensitivity to environmental changes23,34. By engaging with expert-standard actions and undergoing repeated practice, cadets in the efficient training group reinforce correct learning pathways, sharpen their perceptual acuity, and reduce the time spent on self-exploration and error correction. This approach optimizes the extraction and processing of critical task-related information, minimizes redundant distractions, and allows cadets to focus on the most essential aspects of each task. Furthermore, this efficient training method fosters conditioned reflexes for specific perceptual-motor combinations, reduces reliance on external feedback, and ultimately improves overall task efficiency35.

As training progresses, the processing of skills transitions from conscious to unconscious levels, reducing cognitive load and allowing cadets to focus on more complex tasks36. This shift enhances efficiency, accelerating skill acquisition37,38. Furthermore, the system improves skill transferability, enabling cadets to quickly apply learned skills to similar but distinct tasks, thereby further accelerating the mastery of complex skills4. However, A key finding of this study was the plateau effect, where performance improvements slowed in complex tasks such as landing and carrier landing. While the flight skills acceleration training system significantly accelerated learning in basic tasks, it appears that more advanced tasks, requiring higher cognitive and motor coordination, led to slower progress as cadets approached expert-level performance. This plateau effect is common in skill acquisition, where early improvements are rapid, but further progress requires more refined skills39. Drawing from years of teaching experience, the instructor has identified carrier landing as a highly complex and difficult task, ere progress tends to be slow and often plateaus. Due to the numerous unpredictable factors involved, cadets must undergo repeated practice to stabilize both their performance and skill. Addressing this challenge will be a key focus for future improvements.

Limitations & future work

However, this study has several limitations. First, the sample size was relatively small, consisting of only 40 cadets, which may have limited the generalizability of the results40,41. Additionally, gender differences were not considered in the analysis, which could potentially influence the results, as research has shown that male and female cadets may exhibit differences in learning styles, performance, and response to training methods. Future studies should include a larger, more diverse sample and explore the potential impact of gender on training outcomes.

Moreover, while this study focused on perceptual-motor learning and multimodal feedback, other personalized training methods, such as those based on virtual reality (VR) and artificial intelligence (AI), hold significant promise. VR technology can create highly immersive flight environments, allowing cadets to perform tasks in fully simulated spaces and experience complex and extreme flight scenarios, thereby enhancing their ability to handle diverse situations42. AI, on the other hand, can adapt training systems in real-time based on cadet performance, offering personalized content by analyzing operational habits, error types, and learning curves (Smith & Roberts, 2020). Future research should explore the integration of these technologies into the current system43.

This study focused on an 8-week short-term training period, so the long-term effects and stability of the system remain uncertain. Expanding the sample size and extending the study duration in future studies would provide further insights into the effectiveness and long-term applicability of this system.

Despite these limitations, the findings of this study provide valuable insights for optimizing flight skills training. By further enhancing and refining the system, pilot training institutions can improve cadet skill development, increase training efficiency, and reduce costs.

Conclusion

This study successfully demonstrated the effectiveness of a flight skills acceleration training system that combines perceptual-motor theory with multimodal feedback technology. The results indicate that the ETG, which used this system, exhibited faster learning and significantly better performance in takeoff, flight control, landing, and carrier landing tasks compared to the traditional training group. These findings highlight the potential of integrating multimodal feedback in flight training systems to accelerate skill acquisition, optimize training efficiency, and enhance cadet performance.

The innovative nature of this training system provides valuable insights into the future of flight training, suggesting that further advancements in perceptual-motor learning and multimodal feedback can lead to more efficient, flexible, and adaptive training approaches. Future work should aim to refine the system, expand its application to other flight tasks, and investigate its impact on real-world flight performance.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Allerton, D. J. & Lammertse, P. Lessons learnt and lessons missed from flight simulation. Eur. J. Dent. Educ. https://doi.org/10.1111/eje.12919 (2023).

Hays, R. T., Jacobs, J. W., Prince, C. & Salas, E. Flight simulator training effectiveness: A Meta-Analysis. Military Psychol. 4 (2), 63–74. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327876mp0402_1 (1992).

Wang, L., Gao, S., Hong, R. & Jiang, Y. Effects of age and flight exposure on flight safety performance: evidence from a large cross-sectional pilot sample. Saf. Sci. 165, 106199. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssci.2023.106199 (2023).

Ericsson, K. A., Krampe, R. T. & Tesch-Römer, C. The role of deliberate practice in the acquisition of expert performance. Psychol. Rev. 100 (3), 363–406. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.100.3.363 (1993).

Garris, R., Ahlers, R., Driskell, J. E. & Games Motivation, and learning: A research and practice model. Simul. Gaming. 33 (4), 441–467. https://doi.org/10.1177/1046878102238607 (2002).

Dinçer, N. Elevating aviation education: A comprehensive examination of technology’s role in modern flight training. J. Aviat. 7 (2), 317–323. https://doi.org/10.30518/jav.1279718 (2023).

Rizvi, S. A. Q. et al. Exploring technology acceptance of flight simulation training devices and augmented reality in general aviation pilot training. Sci. Rep. 15, 2302. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-85448-7 (2025).

Gibson, J. J. & Gibson, E. J. Perceptual learning; differentiation or enrichment? Psychol. Rev. 62 (1), 32–41. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0048826 (1955).

Goldstone, R. L. Perceptual learning. Ann. Rev. Psychol. 49, 585–612. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.49.1.585 (1998).

Watanabe, T. & Sasaki, Y. Perceptual learning: toward a comprehensive theory. Annual Rev. Psychol. 66, 197–221. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-010814-015214 (2015).

Ahissar, M. & Hochstein, S. The reverse hierarchy theory of visual perceptual learning. Trends Cogn. Sci. 8 (10), 457–464. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2004.08.011 (2004).

Frank, S. M. et al. A behavioral training protocol using visual perceptual learning to improve a visual skill. STAR. Protoc. 2 (1), 100240. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.xpro.2020.100240 (2021).

Casner, S. M. & Schooler, J. W. Vigilance impossible: diligence, distraction, and daydreaming all lead to failures in a practical monitoring task. Conscious. Cogn. 35, 33–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.concog.2015.04.019 (2015).

Gopher, D., Well, M. & Bareket, T. Transfer of skill from a computer game trainer to flight. Hum. Factors. 36 (3), 387–405. https://doi.org/10.1177/001872089403600301 (1994).

Kellman, P. J. & Kaiser, M. K. Perceptual learning modules in flight training. Proc. Hum. Factors Ergon. Soc. Annual Meeting. 38 (18), 1183–1187. https://doi.org/10.1177/154193129403801808 (1994).

Schneider, W. & Fisk, A. D. Attention theory and mechanisms for skilled performance. Adv. Psychol. 12, 119–143. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0166-4115(08)61989-5 (1983).

Wickens, C. D., Goh, J., Helleberg, J., Horrey, W. J. & Talleur, D. A. Attentional models of multitask pilot performance using advanced display technology. Hum. Factors. 45 (3), 360–380. https://doi.org/10.1518/hfes.45.3.360.27250 (2003).

Wiggins, M. W. & O’Hare, D. Expertise in aeronautical weather-related decision making: A cross-sectional analysis of general aviation pilots. J. Experimental Psychology: Appl. 1, 305–320. https://doi.org/10.1037/1076-898X.1.4.305 (1995).

Cornelio, P., Velasco, C. & Obrist, M. Multisensory integration as per technological advances: A review. Front. NeuroSci. 15, 652611. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2021.652611 (2021).

Thomay, C. et al. Modeling Behavior, Perception, and Cognition of Pilots in a Real-time Training Assistance Application. In Proceedings of the 16th International Conference on PErvasive Technologies Related to Assistive Environments (PETRA ‘23). Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, 106–112. https://doi.org/10.1145/3594806.3594809 (2023).

Masi, G., Amprimo, G., Ferraris, C. & Priano, L. Stress and workload assessment in Aviation—A narrative review. Sensors 23 (7), 3556. https://doi.org/10.3390/s23073556 (2023).

Van Erp, J. B. F. & Van Veen, H. A. H. C. Vibrotactile in-vehicle navigation system. Transp. Res. Part. F: Traffic Psychol. Behav. 7 (4), 247–256. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trf.2004.09.003 (2004).

Dunn, M. J. M., Molesworth, B. R. C., Koo, T. & Lodewijks, G. Effects of auditory and visual feedback on remote pilot manual flying performance. Ergonomics 63 (11), 1380–1393. https://doi.org/10.1080/00140139.2020.1792561 (2020).

Li, T. & Lajoie, S. Predicting aviation training performance with multimodal affective inferences. Int. J. Train. Dev. 25, 301–315. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijtd.12232 (2021).

Li, W. C., Horn, A., Sun, Z., Zhang, J. & Braithwaite, G. Augmented visualization cues on primary flight display facilitating pilot’s monitoring performance. Int. J. Hum. Comput. Stud. 135, 102377. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhcs.2019.102377 (2020).

Xu, R. & Cao, S . Modeling Pilot Flight Performance in a Cognitive Architecture: Model Demonstration. Proc. Hum. F. Ergon. Soc. Annu. Meet. 65(1), 1254–1258.. https://doi.org/10.1177/1071181321651008(2021)

Buccino, G. et al. Action observation activates premotor and parietal areas in a somatotopic manner: an fMRI study. Eur. J. Neurosci. 13 (2), 400–404 (2001).

Cattaneo, L. & Rizzolatti, G. The mirror neuron system. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 66 (5), 557–560. https://doi.org/10.1001/archneurol.2009.41 (2009).

Fogassi, L. et al. Parietal lobe: from action organization to intention Understanding. Science 308 (5722), 662–667. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1106138 (2005).

Iacoboni, M. Neural mechanisms of imitation. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 15 (6), 632–637. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conb.2005.10.010 (2005).

Keysers, C. & Gazzola, V. Expanding the mirror: vicarious activity for actions, emotions, and sensations. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 19 (6), 666–671. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conb.2009.10.006 (2009).

Faul, F. et al. G*Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav. Res. Methods. 39, 175–191. https://doi.org/10.3758/BF03193146 (2007).

Broadbent, D. P., Causer, J., Williams, A. M. & Ford, P. R. Perceptual-cognitive skill training and its transfer to expert performance in the field: future research directions. Eur. J. Sport Sci. 15 (4), 322–331. https://doi.org/10.1080/17461391.2014.957727 (2015).

Pool, D. M., Harder, G. A. & van Paassen, M. M. Effects of simulator motion feedback on training of Skill-Based control. Behav. J. Guidance Control Dyn. 39 (4), 889–902 (2016).

Carpenter, S. K. et al. Using spacing to enhance diverse forms of learning: review of recent research and implications for instruction. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 24, 369–378. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-012-9205-z (2012).

Furley, P., Wood, G. & Working Memory Attentional control, and expertise in sports: A review of current literature and directions for future research. J. Appl. Res. Memory Cognition. 5 (4), 415–425. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jarmac.2016.05.001 (2016).

VanLehn, K. Cognitive skill acquisition. Ann. Rev. Psychol. 47, 513–539. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.47.1.513 (1996).

Sweller, J. Working Memory, long-term memory and instructional design.J. Appl. Res. Mem. Cognit. 5(4), 360–367. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jarmac.2015.12.002(2016)

Hodges, N. J. & Williams, A. M. (eds). Skill Acquisition in Sport: Research, Theory and Practice (3rd ed.) (Routledge, 2019). https://doi.org/10.4324/9781351189750

Button, K. S. et al. Power failure: why small sample size undermines the reliability of neuroscience. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 14 (5), 365–376. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn3475 (2013).

Faber, J. & Fonseca, L. M. How sample size influences research outcomes. Dent. Press. J. Orthod. 19 (4), 27–29. https://doi.org/10.1590/2176-9451.19.4.027-029 (2014).

Pan, X. & Hamilton, A. F. d. C. Why and how to use virtual reality to study human social interaction: the challenges of exploring a new research landscape. Br. J. Psychol. 109 (3), 395–417. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjop.12290 (2018).

Källström, J., Granlund, R. & Heintz, F. Design of simulation-based pilot training systems using machine learning agents. Aeronaut. J. 126 (1300), 907–931. https://doi.org/10.1017/aer.2022.8 (2022).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

YZ: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Data curation, Visualization, Writing - original draft.JC: Software development, Formal analysis, Algorithm optimization, Technical validation.XZ: Statistical analysis, Neuroergonomic data processing, Result verification,.YS: Perceptual learning framework design, Experimental paradigm development, Flight skill assessment criteria, Device calibration.WF: Supervision, Funding acquisition, Project administration, Writing - review & editing (corresponding author).

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, Y., Chen, J., Zhong, X. et al. Evaluating the effectiveness of flight simulator training on developing perceptual-motor skills among flight cadets: a pilot study. Sci Rep 15, 28062 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-12929-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-12929-0

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

The effects of different neck training methods on the neck function of aviation cadets

Scientific Reports (2026)