Abstract

With the growing demand for highly secure medical data transmission, this research introduces a fused cryptography framework that integrates mathematical quantum computing operations with advanced classical encryption techniques. The proposed method incorporates quantum principles, including quantum walks, quantum-based cyclic shift operators, quantum XOR operations, and quantum key image generation with classical methods such as bit-plane extraction and hyperchaotic system-based scrambling. A hyperchaotic map generates random key sequences to produce both a spatial domain random image and a quantum key image. The medical image is first decomposed into eight bit-planes, and only the high-information bit-planes (HIBPs) undergo encryption to optimize computational efficiency. HIBPs are scrambled using multilayer, block-wise, and diagonal permutations based on the chaotic sequences. Quantum encryption is then applied, starting with novel enhanced quantum representation encoding, followed by Baker map-based scrambling and quantum XOR diffusion to secure the final ciphertext. Extensive experiments, including entropy evaluation, noise attack resilience, clipping attack robustness, and correlation analysis, confirm the superior security and performance of the proposed method. Notably, the algorithm achieves near-ideal results, such as an entropy of 7.9999, a correlation coefficient of 0.0001, 98% plaintext recovery after 30% noise corruption, and 96% recovery after 25% ciphertext clipping, demonstrating its robustness for secure medical data transmission.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Quantum cryptography provides unique advantages, such as superposition and entanglement, which enable the detection of any eavesdropping attempts on transmitted data1,2. This makes quantum cryptography significantly secure and ensures the integrity and confidentiality of sensitive information, such as medical data, with a level of protection far beyond the capabilities of classical encryption techniques3. However, the practical deployment of quantum systems still faces technical and infrastructural challenges. To address these limitations and leverage the strengths of both quantum and classical approaches, fusion cryptography, a technique that combines traditional cryptographic algorithms with quantum-based mechanisms has emerged as a promising solution.

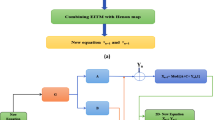

Moreover, the wireless transmission of digital medical data has experienced significant growth. Therefore, the demand for securely transmission of digital data has greatly increased4. For instance, in the Internet of Things (IoT) environment, where digital devices are interconnected, securing sensitive information exchanged between these IoT devices is crucial5,6. Particularly when dealing with medical data, it become more important to transmit such kind of information in a secure manner7,8. The classical encryption frameworks such as Blowfish9, and ElGamal10, and Advanced Encryption Standard (AES)11 provide significant security to the digital data. However, such encryption frameworks creates significant challenges in terms of computational complexity due to the multiple encryption rounds. Moreover, these encryption schemes are also susceptible to quantum cyberattacks. Quantum computing and encryption have the potential to solve complicated challenges and can provide robust security compared to classical encryption methods12,13. A generalized hybrid quantum cryptographic framework is illustrated in Fig. 1, which shows how the medical image undergoes both classical and quantum encryption processes to ensure robust security of the medical data.

Quantum computing leverages quantum mechanics concepts, including superposition, quantum tunnelling, and entanglement for the processing of digital data in different ways14. A qubit is the basic unit of quantum information that can exist simultaneously in multiple states. This enables quantum computers to perform multiple calculations simultaneously with high speed and efficiency. This capability of quantum computing also creates significant threats for current classical encryption methods, such as RSA and ECC. Such classical encryption schemes are also vulnerable to quantum cyberattacks. Quantum cyberattacks can recover plaintext information from the ciphertext message in a very short time15. The shift from classical to quantum computing poses a dual-sided challenge for the existing encryption methods: (i) quantum computing offers high potential for advancements across various cybersecurity fields, and (ii) it threatens the existing cryptographic techniques. This necessities the development of such an encryption framework that can withstand quantum-level attacks.

In image encryption, ensuring digital data security is of utmost importance16. For instance, medical imaging not only involves sensitive personal data but also requires strict compliance. Therefore, there is a need for robust encryption techniques that can secure digital images against classical as well as quantum cyberattacks. This can be achieved by developing hybrid encryption frameworks that combines the strengths of both classical and quantum encryption frameworks. Contemporary encryption methods must balance computational efficiency and robust security17,18,19. They must also be capable of protecting digital images against different cyberattacks. This is especially crucial in telemedicine, where fast processing and access to encrypted medical images are necessary.

The integration of quantum properties, such as quantum walks20, quantum XOR operations21, and quantum cyclic shift operators22 provides a significant level of security for digital data. Quantum walks can introduce a high level of unpredictability between image pixels. However, quantum XOR and cyclic operations add an extra layer of security. This makes it difficult for any unauthorised access to recover the original data without the correct quantum keys. Quantum walks also exhibit behaviour different from their classical counterparts in the encryption process. This property is used in encryption to achieve high levels of randomness and complexity. Additionally, quantum XOR operations enable the mixing of quantum states, which further enhances data security23,24. Quantum cyclic shift can cyclically shift the state of a qubit, which also ensures that the encryption scheme is resistant to quantum as well as classical cyberattacks.

This research proposes a hybrid cryptographic framework that merges quantum walk and cyclic operations with traditional cryptographic methods, including bit-plane extraction, chaos, and diffusion-permutation operations. Chaos theory has tremendous encryption properties, such as inherent unpredictability, and generates complex key sequences. By incorporating hyperchaotic maps (HCM) to produce random sequences, the proposed method ensures that the permutation and diffusion operations provide high randomness in the ciphertext image pixels. It also provides high entropy values and a low correlation between the encrypted images. Overall, this combination of quantum and classical methods aims to create a robust encryption framework that is capable of resisting quantum attacks.

Organization of the paper

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows: Section “Related work” provides the literature fo the existing methods and their associated challenges. Section “Preliminaries” is devoted to the preliminary concepts necessary for designing the cryptographic framework. Section “Proposed encryption framework” provides the development process of the proposed framework. Section “Experimental results and analysis” presents the experimental results of the proposed cryptosystem and compares them with existing ones. Finally, Section “Conclusion” provides the conclusion of the paper.

Related work

In recent years, several advanced techniques, such as permutation-based, quantum-based, and bit-plane extraction-based methods, have been proposed for encrypting plaintext images with low latency25,26. These approaches aim to enhance efficiency by reducing the computational overhead and speeding up the encryption process, making them well-suited for real-time applications. However, despite their improved processing speed, these techniques can sometimes compromise security by introducing vulnerabilities or reducing the overall complexity of the encryption, making them more susceptible to attacks. For instance, in27, Zhang et al. proposed a quantum-based image encryption scheme that uses quantum image correlation. This method uses quantum state superposition to modify the pixel values. Moreover, the image splits into binary sub-images. Later on, these sub-images are encrypted with quantum rotation28, and random phase29 operations. The combined encrypted sub-images form the final ciphertext image. The large key space of the proposed scheme helps resist brute-force attacks. However, their algorithm is vulnerable to quantum- attacks due to errors in quantum hardware, which compromise its security. In30, Akhshani et al. proposed an image encryption scheme based on the quantum logistic map, leveraging its chaotic properties similar to classical systems. Their security and performance analyses show the method is efficient and secure. The study also suggests exploring other quantum maps for cryptography and security applications. In31, Liu et al. introduced a third-level image encryption scheme in the domain of cryptography using the chaotic Arnold and logistic maps32,33. The encryption process consists of block permutation and bit-level scrambling. At the first stage, the classical image undergoes quantum encoding. Next, quantum operations are applied to scramble the image blocks, where the positions of qubits are altered using dynamic parameters. This approach addressed periodic defects that may arise during the encryption process. By manipulating the qubit states in this manner, their proposed method ensures a significant level of security and unpredictability, which makes it more resistant to potential attacks. Moreover, bit-level permutation scrambles the order of the bit planes based on a random sequence. Their proposed algorithm is vulnerable to cyberattacks due to the weaknesses in the logistic map34. In35, Liu et al. presented a quantum-based image encryption scheme incorporating bit-plane scrambling. The algorithm represents the plaintext image with a quantum model. First, the quantum transform scrambles the image pixels. The diffusion is created in the scrambled image shift and XOR operations. Their proposed algorithm has issues when quantum computing is used to attack the ciphertext data.

Hu et al.36 introduced quantum encryption with a modified image representation. The encryption procedure involves Arnold transformation based scrambling and quantum transforms based on the wavelets, which are used to decompose the original image. Further scrambling of wavelet coefficients is performed. This algorithm may be vulnerable to quantum attacks on wavelet transforms and scrambling operations. Also, it is suspectable if any reversible operations are improperly implemented. In37, Alawida et al. introduced an image encryption algorithm utilizing chaotic theory for enhanced security. The authors employed logistic chaotic map to generate key random sequences38,39. Their method combines permutation operation, XORing, and hashing operations40. These operations produces eight-bit numbers for permutation and successfully encrypting images of various sizes. However, it is vulnerable to cryptanalysis targeting the chaotic map and permutation operations. Moreover, highly reliance on XORing and hashing operations create risks if the initial seed values are not properly chosen. In41, Masood et al., proposed a lightweight cryptosystem leverges Henon map42, and Chen’s system43. They evaluated its efficiency through various analyses and experimental results demonstrated its effectiveness. However, the reliance of the system on lightweight design makes it vulnerable to differential cyber attacks. In44, Shaukat et al. reviewed chaos theory applications in image encryption. Their review highlighted the key benefits of incorporating chaotic systems. They also emphasized how chaotic systems contribute to increased randomness and complexity, which makes it more challenging to decrypt the original data. Chaotic systems, known for their pseudo-random behavior, provide an excellent foundation for creating encryption methods that are both highly secure and difficult to predict. The authors used multiple chaotic maps to generate random numbers for scrambling image pixels. They also identified several promising future directions for the improvement of chaos-based encryption techniques. These directions included incorporating more complex chaotic systems, enhancing key generation methods, and exploring hybrid approaches that combine chaos theory with other cryptographic techniques, such as quantum cryptography or deep learning-based models. Furthermore, the review addressed some of the vulnerabilities found in existing chaos-based cryptosystems. For instance, the security of these systems can be compromised if the chaotic maps used are predictable or if the key space is too small. To overcome these challenges, the authors suggested potential solutions such as improving the initialization parameters of the chaotic systems and integrating multiple layers of encryption for added robustness. This comprehensive review provided valuable insights into the potential and challenges of chaos-based encryption and laid the groundwork for future advancements in the field.

In45, Fan et al. proposed a quantum image encryption method using the Fisher–Yates algorithm and Logistic mapping to scramble coordinate and color qubits, followed by an XOR with a scrambled key image. The scheme provides strong security and linear complexity but has two vulnerabilities: reliance on the classical Logistic map, which may lack sufficient randomness in quantum contexts, and complex key management that risks desynchronization or leakage without secure distribution like QKD. In46, Verma et al. presented a quantum image encryption method using Fisher–Yates and Logistic mapping, offering strong security and linear complexity. It relies on classical chaotic systems that may lack quantum-level randomness and involves complex key management prone to leakage without QKD. It also enhances this with a 3D-BNM chaotic map, SHA-256, and qubit-level scrambling. While effective, it uses classical hashing, which is vulnerable to quantum attacks and depends on complex quantum operations that may be error-prone on current quantum hardware. In47, Li et al. proposed a holographic encryption scheme that integrates Lorenz systems48,49 for encrypting images. Their algorithm converts the plaintext image into a hologram as the initial step. Hologram is a process that enables the transformation of the image into a form that appears random and unintelligible. Once the hologram is generated, the algorithm decomposes the bit-planes, a step that isolates different levels of pixel information. To enhance the security further, Arnold scrambling is applied to the bit-planes, which effectively rearranges the pixel positions in a pseudo-random manner, making it difficult to trace the original structure of the image. In addition to the scrambling process, the encryption scheme uses an XOR operation to create diffusion, which spreads the pixel values across the image. This diffusion step ensures that changes in one part of the image influence the entire image, further enhancing the encryption’s resistance to attacks. The combination of holographic transformation, bit-plane decomposition, Arnold scrambling, and XOR-based diffusion results in a highly secure encryption process that obscures the original image content. However, the proposed framework has a notable vulnerability: If the hyperchaotic Lorenz system’s initial values are not carefully chosen from within the chaotic range, the encryption scheme may lose its effectiveness. This could lead to predictable patterns, which makes it easier for attackers to identify and exploit vulnerabilities. Moreover, improper initialization could lead to predictable or repeatable patterns in the encryption process. This sensitivity to initial values emphasizes the importance of choosing appropriate chaotic parameters.

In50, Shafique et al. proposed a cryptographic system that stands out by focusing on bit-level diffusion and permutation operations. Rather than directly manipulating the image pixels, their scheme applies these operations to individual bit-planes. Bit-level permutation enhances encryption complexity. The bit-plane approach allows for a finer level of control over the encryption process. This approach also ensures that the encrypted image appears highly randomized, significantly masking the original information. However, in51, Wen et al. analyzed the cryptographic strength of the scheme proposed in50 and successfully broke its security, revealing its vulnerabilities. Their analysis demonstrated that the encryption, while initially promising, could be compromised through specific attacks that exploit weaknesses in the bit-level operations. Based on their findings, the authors recommended a few improvements specifically targeting the weak areas in its design to strengthen its overall security. In52, Tang et al. introduced an encryption framework using bit-plane methodology, which combined it with a technique known as bit-block swapping53. In this approach, the image is divided into smaller bit-blocks, and the blocks are then permuted in a manner that is controlled by chaotic sequences. The permutation process is based on chaotic maps, which ensures that the rearrangement of the image blocks appears highly randomized. Additionally, the framework uses a controlled matrix to create diffusion in the final encrypted image, which also further enhances its resistance to potential attacks. However, similar to previous schemes, the encryption method introduced by Tang et al. is vulnerable to attacks that target the chaotic map and XOR operations. If the chaotic sequences are not sufficiently complex or if weaknesses exist in the XOR-based diffusion process, attackers may be able to break the encryption and retrieve the original image. This highlights the importance of carefully designing the chaotic systems and diffusion mechanisms to prevent potential cryptanalysis. The summary of the existing encryption works is given in Table 1.

Contributions of the paper

As discussed in Section “Related work”, the existing cryptographic schemes face several challenges and vulnerabilities. To overcome these vulnerabilities, the following are the contributions made in the proposed research.

-

A fused cryptogtaphic approach is proposed that integrates quantum principles with classical methods. This approach generates random key sequences using a hyperchaotic map (HCM) for both spatial domain random image and quantum key image generation. Classical encryption methods, such as bit-plane extraction and chaos theory, are also utilized to enhance security.

-

The proposed framework employs multiple permutation techniques, such as multilayer, block-wise, and diagonal, instead of using a single permutation technique. The disadvantages of using a single permutation operation are given in51. The multiple permutation operations are applied only on high information bit-planes (HIBPs) of the plaintext image. These permutations change both the bit positions and corresponding pixel values, introducing maximum randomness into the encrypted image. Another advantage of considering only HIBPs for encryption is that it significantly reduces computational overhead.

-

Incorporates a quantum encryption phase using the NEQR model for initial representation, followed by quantum XOR operation and block scrambling with the Baker map, and further row and column scrambling using index-order methods.

-

This paper advances the state-of-the-art in quantum-enhanced encryption methodologies for digital color images. By combining quantum principles with classical encryption techniques, it contributes to the creation of robust and high-performance encryption methods capable of resisting emerging security threats.

-

The resilience of the proposed encryption framework is demonstrated against various types of attacks such as noise addition, brute force attack, and clipping attack, which shows the high recovery rates of the plaintext image even under adverse conditions.

Preliminaries

This section provided a brief preliminary knowledge that is required to develop the proposed encryption framework.

6D Hyper chaotic map

A 6D hyperchaotic map (6DHCM)40 is a chaotic system that can be used for multi purposes such as the generation of random sequences, key generation, and key random image generation. The mathematical expression of 6DHCM is given in Eq. (1).

where \(\xi _1, \xi _2, \xi _3, \xi _4, \xi _5\) and \(\xi _6\) play vital roles in determining the behaviour of the system, such as whether it exhibits chaotic and bifurcation ehavior. Here’s a summary of how these constants influence the system:

-

\(\xi _1\): This influences the rate of change of the system in certain variables. High values can increase the system’s sensitivity to initial conditions.

-

\(\xi _2\): Associated with damping and can affect the stability of periodic orbits. Large values can promote transitions to chaos by destabilising the periodic orbits.

-

\(\xi _3\): Control the nonlinearity strength in the system. Moderate to high values can lead to complicated behaviours such as bifurcations, where small changes in \(\xi _3\) can shift the system from periodic to chaotic dynamics.

-

\(\xi _4\): This Influences coupling strengths between different dimensions in the system.

-

\(\xi _5\): Related to secondary coupling terms. This parameter can fine-tune the behavior of the system. Even small values of \(\xi _5\) can introduce additional degrees of freedom that push the system into hyperchaotic systems.

With the specific values given \(\xi _1 = 11\), - \(\xi _2 = 75\), \(\xi _3 = 4\), - \(\xi _4 = 0.3\), - \(\xi _5 = 0.2\). For the initial condition (0.3, 0.42, 0.62, 0.34, 0.39, 0.41), the 6DHCM exhibit chaotic behavior.

A phase plot is used to visualise dynamic systems that exhibit complicated behaviors. Both 2D and 3D phase plots can represent the trajectory of a 6-dimensional hyperchaotic system. These plots are used to observe the motion of variables in the 6D hyperchaotic map. Figure 2a–f illustrate the 2D and 3D phase plots, respectively, based on the 6D hyperchaotic map.

A phase plot is used to visualize the behavior of dynamic systems, especially those that exhibit complex and chaotic dynamics. These plots provide a way to represent how a system evolves over time by showing the trajectory of its variables within a defined space. For systems with higher dimensions, such as a 6-dimensional hyperchaotic system, both 2D and 3D phase plots can effectively illustrate the system’s trajectory, helping to capture its intricate motion and underlying patterns.

In particular, phase plots are valuable for observing the motion of variables in the context of the 6D hyperchaotic map, as they reveal the system’s evolution and allow for the identification of complex behaviors such as periodicity, chaos, and bifurcations. The 2D phase plot offers a simplified view of the system’s dynamics by projecting the motion onto two axes, while the 3D phase plot provides a more comprehensive visualization, allowing for a clearer representation of the system’s trajectory in three-dimensional space.

Figure 2a–d present the 2D phase plots, which depict how the system’s variables interact in a two-dimensional space, while Fig. 2e,f show the 3D phase plots, offering a more detailed representation of the system’s trajectory and its chaotic nature in a three-dimensional space. Both sets of plots show the behavior of the 6D hyperchaotic system, revealing the complexity and unpredictability inherent in its dynamics.

Apart from the phase plotts, Lyapunov exponents for 6DHCM system are also computed using a numerical algorithm based on Orthogonal–Triangular decomposition with a fourth-order Runge–Kutta (RK4) integrator.

The system parameters are set to: \(\xi _1 = 35\), \(\xi _2 = 90\), \(\xi _3 = 2\), \(\xi _4 = 0.1\), \(\xi _5 = 0.1\), \(\xi _6 = 0.05\), \(\omega _1 = 5\), \(\omega _2 = 5\). With the initial condition \((1.1, -1.2, 0.9, -0.8, 1.5, -1.0)\), and a step size of \(dt = 0.005\) over 1000 iterations, the computed Lyapunov exponents are as follows:

These results shows that the system has two positive Lyapunov exponents (\(\lambda _1 > 0\) and \(\lambda _2 > 0\)), a hallmark of hyperchaotic dynamics. The existence of multiple directions of exponential divergence in the system’s phase space is a strong indicator of its complexity and unpredictability. For 6DHCM, the calculation of the six Lyapunov exponents helps validate the chaotic behavior, and it shows the system is hyperchaotic as displayed in Fig. 3.

Bit-layer extraction

While encryption can be performed directly on image pixels, several researchers have stated that bit-level encryption is more robust than pixel-level encryption54,55,56. In this research, a bit layer extraction method is used to decompose the plaintext image into its corresponding eight-bit layers. Each bit layer contains varying amounts of the informaiton of the plaintext image. For instance, the lower bit layers contain the least amount of plaintext information, as shown in Fig. 4. Specifically, Fig. 4a,b displays the plaintext color X-ray images along with their corresponding R components. Figure 4c–f illustrates that the higher bit planes retain most of the plaintext information, whereas Fig. 4g–j demonstrates that the lower bit planes contain minimal information from the original image.

Equation (2) can be used to calculate the percentage amount of plaintext information that is present in each bit layer57. Table 2 represents the amount of information present in each bit layer.

Quantum image representation

In contrast to the flexible representation model of quantum image (FRQI)58 representation model, the novel enhanced quantum image representation (NEQR)59 model diverges by encoding grayscale information without utilizing individual qubits. Instead, NEQR employs quantum superposition states for storage. In NEQR, grayscale and pixel position data are encoded separately using entangled sequences of quantum states. This approach enables NEQR images to be stored in quantum systems through entanglement between sequences dedicated to grayscale and pixel position information, presenting a unique method of quantum representation compared to FRQI.

In the NEQR model, each color component’s size a \(2^t \times 2^t\) can be represented using \(2^m + q\) qubits. Among these, \(2^m\) bits encode pixel position information, while q bits encode color information. For instance, if a grayscale image G has gray values ranging from 0 to 255, its NEQR representation can be expressed using Eq. (3).

The pixel position a \(|zy\rangle\) is encrypted as \(|p_{zy}\rangle = |p_8^{zy} p_7^{zy} \cdots p_1^{zy} p_1^{zy}\rangle\). In this context, the coordinates are represented as \(|zy\rangle = |z\rangle |y\rangle = |z_{t-1} z_{t-2} \cdots z_0\rangle \otimes |y_{t-1} y_{t-2} \cdots y_0\rangle\), where the symbol \(\otimes\) denotes the tensor product.

Each pixel in the image has color information stored across multiple channels (e.g., R, G, B). Let’s denote the color channels as \(c\) (where \(c = 1,2, \text {and}, 3\) for R, G, and B components, respectively). If each color channel is represented with \(q\) bits (where \(q\) can vary based on the bit depth of each channel), Eq. (3) can be written as:

For a \(2^t \times 2^t\) color component, i.e. \(\begin{bmatrix} 00010000& \quad 00100000\\ 11111111& 10000000\end{bmatrix}\) which consists of two pairs of pixels, is split into four parts; the NEQR model assigns coordinate and color values to each part. This example is represented quantum mechanically in Eq. (5).

Figure 5 depicts the setup of the NEQR quantum circuit.

Baker map

The Baker map (BM) operates by repeatedly extending horizontally and bending vertically within continuous plane regions, gradually altering the position information of all pixels60. This classical map is mathematically defined by Eq. (6).

After transformation, \(\upsilon '\) and \(\varpi '\) represent the new coordinate information resulting from the classic BM. This map divides a square into equal left and right blocks, which are subsequently transformed into upper and lower blocks.

The ith segment can be described as [\(m_j, m_j + w_j\)], and the mapping of the complete region is given by Eq. (7).

The classic Baker map transforms61 coordinate information \(\upsilon ', \varpi '\) from \(\upsilon , \varpi\) after a transformation. It evenly divides a square into left and right sections, then converts them into upper and lower sections.

Each sub-interval \(j\) can be denoted as [\(m_j, m_j + w_j\)], and the whole region mapping is expressed using Eq. (8):

Proposed encryption framework

In this section, the encryption framework designed to protect color images is presented. The process begins by breaking down the original image into its eight-bit layers. Next, only the HIBPs are permuted using key streams \(\beta _1, \beta _2, \beta _3, \beta _4, \beta _5, \beta _6\), which are generated through the 6DHCM. Finally, quantum operations are applied to the intermediate-encoded image, producing the fully encoded image. Figure 6 presents the block diagram that illustrates the proposed method.

The detailed steps of the proposed encryption framework are provided in the following subsections.

Key generation process

Assume the color plain image \(P_c\) has dimensions \(A \times B\), and the image sub-bands have dimensions \(a \times b\). While the algorithm extracts color components (R, G, B) from the input image \(I_O\) to influence parameter updates via Eqs. (9)–(19), it is important to clarify that this step does not constitute the entire key generation process. Prior to any image-dependent updates, the system is initialized with independent control parameters and initial conditions selected randomly from the chaotic range of the 6DHCM, each drawn from a key space of approximately \(10^{14}\) possible values. These independently chosen parameters form the actual cryptographic key and are not derived from the plaintext. Therefore, the scheme retains resistance to known-plaintext attacks, as the image merely modulates the dynamics without determining the secret key itself. Eleven key streams are generated using the following steps:

where \(\xi _1, \xi _2, \xi _3, \omega _1, \omega _2\) are the 6DHCM parameters, \(\oplus\) and & denote bitwise XOR and AND operations, respectively. The floor function \(\left\lfloor \cdot \right\rfloor\) is used to ensure valid indexing boundaries for sub-image regions.

Where, \(\xi _1, \xi _2, \xi _3, \omega _1, \omega _2\) are the 6DHCM paramters, \(\oplus\), and & are the bitwise Xor and AND operators, respectively.

Utilize the updated parameters \(\hat{\xi _1}, \hat{\xi _2}, \hat{\xi _3}, \hat{\omega _1}, \hat{\omega _2}\) and initial conditions \(\hat{\beta _1}(0), \ldots , \hat{\beta _6}(0)\) to iterate the 6DHCM system [Eq. (1)] for \(T + A \times B\) times, where \(T\) is a sufficiently large number (e.g., 999) to discard the transient behavior.

Process the output chaotic sequences using Eq. (20):

Here, \(\Omega\) is a scaling constant, and \(\text {Unique}(\cdot )\) ensures that each key byte value appears only once.

The pseudocode for generating the key streams is outlined in Algorithm 1, which details how the chaotic map parameters are updated at each step.

It is important to note that the chaotic map parameters \(\xi _1, \xi _2, \xi _3, \omega _1, \omega _2\) and initial conditions \(\beta _1(0), \ldots , \beta _6(0)\) are secret keys that are securely shared between the sender and receiver and are not derived from the plaintext image. In the proposed scheme, the plaintext image is only used to apply minor perturbations to these initial secret parameters. This technique introduces image-dependence to increase confusion and diffusion properties to enhance the resistance against statistical and differential attacks.

Importantly, this design does not expose the core key material, and as such, the scheme is inherently resistant to known-plaintext attacks. Even if an attacker has access to both the original plaintext and its corresponding ciphertext, they cannot reconstruct or reverse-engineer the chaotic map’s initial conditions or parameters, since the transformation relies on secret values that are never revealed or computable from the plaintext alone. Further details regarding the secrecy and sensitivity of the initial conditions and secret keys are provided in Section “Key sensitivity analysis”.

Scrambling phase

Once the secret keys are generated, the bit planes from the color components are extracted, and scrambling operations are applied at the bit level on these extracted bit layers.

The scrambling operation in the proposed encryption framework consists of three major stages: (i) multi-layer rearrangement, (ii) multi-round shuffling, and (iii) diagonal rearrangement.

Multi-layer rearrangement:

In the multi-layer scrambling technique, multiple permutation operations are performed on each individual layer of the image. This provides a higher level of security. In this research, each bit layer is treated as an independent layer, which allows for a more granular approach to encryption. A random sequence is assigned to each bit layer to achieve the scrambling effect and to ensure that the structure of each layer is thoroughly mixed. This method results in more complex and random pixel arrangements across the image. Compared to a single-layer permutation approach, where the entire image undergoes a single scrambling operation, this approach greatly improves the encryption complexity. The additional layers of permutations make the system more robust, as they introduce more variables and combinations. There are three layers of permutation: row-wise, column-wise, and block-wise permutation layers applied to each individual bit layer.

Different random sequences are used for scrambling purposes in each layer to enhance security more effectively than using identical sequences across all layers. The detailed step-by-step permutation process is as follows:

Let a random sequence \(\beta ^{\prime }_1\) be \([2\ 4\ 1\ 3]\), and the R component (\(I_R\)) is: \(I_R\) = \(\begin{bmatrix} 234 & 15 & 93 & 115 \\ 193 & 5 & 98 & 180 \\ 201 & 108 & 74 & 61 \\ 19 & 49 & 191 & 246 \\ \end{bmatrix}\)

The binary version of \(I_R\) is: \(I_{R_b}\) = \(\begin{bmatrix} 11101010 & 00001111 & 01011101 & 01110011 \\ 11000001 & 00000101 & 01100010 & 10110100 \\ 11001001 & 01101100 & 01001010 & 00111101 \\ 00010011 & 00110001 & 10111111 & 11110110 \\ \end{bmatrix}\). Eight bit layers are extracted from \(I_{R_b}\). The extracted bit layers are as follows:

Layer-1 scrambling (Row-wise): Using the random sequence \(\beta _1 = [2\ 4\ 1\ 3]\), we perform row permutation on each bit layer. The permuted bit layers are:

Layer-2 scrambling (Column-wise): Now, using \(\beta _2 = [3\ 2\ 1\ 4]\), we apply column-wise scrambling to the result of Layer-1. The scrambled bit layers become:

Layer-3 scrambling (Block-wise): Before this step, inverse the binary layers back to form a single grayscale matrix \(I_{ps}\): \(I_{ps}\) = \(\begin{bmatrix} 98 & 5 & 193 & 180 \\ 255 & 49 & 19 & 246 \\ 95 & 13 & 232 & 49 \\ 72 & 110 & 203 & 63 \\ \end{bmatrix}\)

Divide \(I_{ps}\) into \(2 \times 2\) blocks: Block-1 = \(\begin{bmatrix} 98 & 5 \\ 255 & 49 \end{bmatrix}\), Block-2 = \(\begin{bmatrix} 193 & 180 \\ 19 & 246 \end{bmatrix}\), Block-3 = \(\begin{bmatrix} 95 & 13 \\ 72 & 110 \end{bmatrix}\), Block-4 = \(\begin{bmatrix} 232 & 49 \\ 203 & 63 \end{bmatrix}\)

Let the block permutation sequence be \(\beta _3 = [2\ 4\ 1\ 3]\). Then, the rearranged matrix \(I_{ML}\) is: \(I_{ML}\) = \(\begin{bmatrix} 193 & 180 & 232 & 49 \\ 19 & 246 & 203 & 63 \\ 98 & 5 & 95 & 13 \\ 255 & 49 & 72 & 110 \\ \end{bmatrix}\)

Multi-round shuffling

In this phase, the output \(I_{ML}\) undergoes multi-round shuffling. Let the random sequence be \(\beta _4 = [1\ 4\ 3\ 2]\). The generated matrices are:

Iterative rearrangement

This stage performs multiple permutations using different sequences. Let \(\beta _5 = [2\ 1\ 4\ 3]\) and \(\beta _6 = [4\ 1\ 2\ 3]\). Apply them sequentially on \(MRSI_3\).

The same scrambling process is applied to the G and B components independently.

Quantum operations-based encryption

The initiation of the quantum state involves utilizing the NEQR model to show the \(F_{pi}\) dimensions of \(2^m \times 2^m\). For non-square images, zero padding is applied. The color channels are processed separately, which allows the algorithm to perform the process and achieve the same results in greyscale images. Each color channel of the color image can be stated accordingly, as represented in Eq. (21).

The pixel information at the positionn \(|zy\rangle\) is encoded as \(|F_{pi_{zy}}\rangle = |F_{pi_{8zy}} F_{pi_{7zy}} \ldots F_{pi_{2zy}} F_{pi_{1zy}}\rangle\). The coordinates are represented as \(|zy\rangle = |z\rangle |y\rangle\) \(= |z_{m-1} z_{m-2}\) \(\ldots z_0 \rangle\) \(|y_{m-1}\) \(y_{m-2}\) \(\ldots y_0\rangle\).

Pixel scrambling is achieved using the 6DHCM. The image in the NEQR model has a size of \(2^m \times 2^m\), with \(M = 2^m\) and \(m_j = 2\). Based on the bakers maping expression from Eq. (8) in Section “Baker map”, the discrete quantum Baker mapping is obtained using Eq. (22).

where y, and z lies in the range \(M_i \le y < M_j + 2^{q_j}\), and \(0 \le z < M\), respectively \(M_i = 2^{q_1 + 2^{q_2}, \cdots 2^{q_j}}, M_0 = 0\).

The Baker map’s scrambling performance depends on control parameters and initial conditions. In62, it is indicated that complex parameter settings increase circuit complexity. However, simple settings result in short cycles. For \(m_1 = \frac{M}{4}\), \(m_2 = \frac{M}{4}\), and \(m_3 = \frac{M}{2}\), the Baker map achieves an ideal balance of permutation effect and the complexity of the circuit. The binary nature of the baker map for such parameters can be expressed using Eq. (23).

The qubit conversion is attained using \(\varrho _{m-1}\) as the control bit. This is the swap gate in the domain of quantum control. The specific quantum circuit for the discrete quantum Baker permutation is illustrated in Fig. 7. By iterating the quantum image \(|I_c\rangle\) through the Baker map multiple times (\(n\) iterations), the permuted image \(|I^{\prime }_c\rangle\) is obtained. Subsequently, the grayscale information of the pixel at that position \(|zy\rangle\) is encoded as \(\big | F^{\prime }_{pi_{zy}} \big \rangle = \big | F^{'8}_{pi_{zy}}, F^{'7}_{pi_{zy}}, \cdots F^{'2}_{pi_{zy}}, F^{'1}_{pi_{zy}} \big \rangle\).

Rotate \(|I^{\prime }_c\rangle\) perpendicular counterclockwise to obtain \(|I^{\prime \prime }_c\rangle\). The robust security and the feasibility of the random rotation of qubits are proved in63. Rotating the image perpendicularly and applying additional permutation effectively reduces the image pixel correlation. Image rotation generates a new image by applying a quantum process as given in Algorithm 2 that employs two horizontal and one vertical rotation to NEQR images. The rotation matrix \(\textbf{R}_{mat}\) is expressed in Eq. (24).

where \(\zeta\) is the angle of rotation.

In the diffusion phase, a 2D pixel planes of color channels are diffused individually. Initially, the random sequences \(\{ y'_i \}\), \(\{ z'_i \}\) are optimized. These sequences are interleaved means that the values from \(\{ y'_i \}\) and \(\{ z'_i \}\) are alternately combined. For instance, the resulting mixed sequence starts with the first value from \(\{ y'_i \}\), followed by the first value from \(\{ z'_i \}\), and continues alternately until the last value. This process generates a new key sequence as given in Eq. (25).

The sequence \(\big [ S_j\big ]\) is transformed into integer numbers that produce a new sequence \(\big [S'_j\big ]\). This transformed sequence \(\big [S'_j\big ]\) is then utilized for subsequent XOR operations.

Now, transform \(\Big [ S^{\prime }_{j}\Big ]\) into its binary Version of qubit sequence using Eq. (27).

where \(\Big |S^{'L}_{j}\Big \rangle \in \{ |0\rangle , |1\rangle \}\)

The final step involves performing XOR operations between the modified image \(|I^{\prime \prime }_c\rangle\) and a binary qubit sequence \(| S^{\prime }_{j}\rangle\) to produce the final enciphertext image \(|E'\rangle\). Equation (28) illustrates the implementation process of this XOR operation.

The images encrypted using the proposed framework are presented in Fig. 9. It is clear that the plaintext information is entirely concealed, with no visible details. This confirms the capability of the proposed hybrid quantum encryption scheme to effectively secure plaintext data.

Experimental results and analysis

The proposed cryptosystem is evaluated through several analyses, including lossless analysis, computational complexity analysis, and correlation analysis. Furthermore, the encryption’s robustness is evaluated against attacks, including noise, brute force attack, and clipping attack. For testing purpose, different sizes of plaintextimages,s such as \(256 \times 256 \times 3\), and \(512 \times 512 \times 3\) are considered. Furthermore, for a fair analysis, the comparable existing schemes are implemented on the same platform for consistency. All algorithms and comparative schemes are implemented and executed on a standardized platform to ensure fairness and consistency in performance evaluation. Specifically, the implementations are developed using MATLAB 2022a running on a Windows 11 (64-bit) operating system. The hardware platform consisted of an Intel Core i7-9700K CPU @ 3.60 GHz with 16 GB RAM, without GPU acceleration. All experiments are performed under these conditions to maintain uniformity across different schemes.

The parameter evaluation values in this study are determined by calculating the averages of the R, G, and B components. For instance, if the entropy values for encrypted color channels are 7.9979, 7.9984, and 7.9987, respectively, their average would be calculated as 7.9983. Similar calculations are applied to calculate the statistical values for other parameters.

Algorithm test

The proposed cryptosystem is applied to four color images, each with a size of \(256 \times 256 \times 3\), for testing purposes. To improve clarity and better illustrate the proposed encryption process, Fig. 8 displays the encrypted images at intermediate stages after each major operation. Specifically, Fig. 8b,e,h,k show the intermediate encrypted images generated by the triple permutation process, while Fig. 8c,d,i,j present the intermediate encrypted images produced by the quantum encryption module. As observed from Fig. 8, no discernible information is visible in any of the intermediate encrypted images.

Moreover, Fig. 9 illustrates the final encrypted results for each plaintext image, displaying the individually final encrypted R, G, and B color components, as well as the final encrypted color image created by combining these components. The ciphertext images shown in Fig. 9 reveal no meaningful information. This makes it difficult to extract plaintext data. Therefore, it reduces the risk of information leakage. Moreover, the decrypted images (Fig. 9f,l,r,x) closely resemble the originals.

Test université de montréal 01 (TestU01)

To evaluate the statistical quality of the sequences generated by 6DHCM, the output bitstreams are subjected to the comprehensive TestU01 suite64. A bitstream of length \(10^8\) bits is generated from the 6DHCM output by quantizing the floating-point chaotic outputs. This bitstream is tested against three TestU01 batteries: SmallCrush, Crush, and BigCrush.

The results in Table 3 indicate that the 6DHCM sequences pass nearly all the stringent tests, with p values uniformly distributed within the acceptable range \([0.01, 0.99]\). No statistically significant deviations from randomness are detected.

Justification of using tripled permutation design

The decision to use a triple permutation design is driven by the need to maximize confusion and diffusion, which are two fundamental principles in secure cryptographic systems as defined by Claude Shannon. While a single permutation can provide a basic level of obfuscation, it is insufficient to prevent various forms of cryptanalysis such as statistical attacks, differential cryptanalysis, and known-plaintext attacks. Multiple layers of permutation exponentially increase the complexity and resistance against such attacks. In the case of a single permutation, patterns in plaintext (especially repetitive blocks or low-entropy regions) are likely to survive the transformation to some extent, which can be exploited by an attacker. In contrast, cascading multiple permutations ensures that even minor changes in input lead to highly non-linear and unpredictable outputs, a property known as the avalanche effect.

The tripled permutation design is tested using NIST randomness tests. The single permutation design failed the block frequency and runs tests due to residual patterns. The triple permutation passed all 15 NIST tests, indicating near-ideal randomness and unpredictability.

NIST randomness test analysis

The proposed algorithm is evaluated using the NIST Statistical Test Suite (SP800-22) to assess the randomness and unpredictability of output sequences generated from 6DHCM. The suite comprises 15 well-established tests designed to detect various non-random patterns and biases in binary sequences. These tests include Frequency (Monobit), Block Frequency, Runs, Longest Run of Ones, Rank, FFT, Non-overlapping Template Matching, Overlapping Template Matching, Universal Statistical, Approximate Entropy, Serial, Cumulative Sums, Random Excursions, Random Excursions Variant, among others. Table 4 presents a comparison of the test results between single and triple permutation designs. It is clear from the Table that the triple permutation consistently passes all tests, whereas the single permutation fails critical ones related to block frequency and run lengths.

Single permutation design: The output ciphertext generated using a single permutation failed key tests such as the block frequency and runs tests. These failures indicate residual patterns and predictable structures remain in the ciphertext, rendering it vulnerable to statistical attacks. The other tests yielded mixed results with some borderline p values, suggesting only partial randomness.

Triple permutation design: The ciphertext resulting from the triple permutation design successfully passed all 15 NIST tests, with p values well above the significance threshold (typically 0.01). This shows that the output is statistically indistinguishable from a truly random sequence, which provides strong evidence for the proposed algorithm’s enhanced security and robustness against statistical cryptanalysis.

Lossless analysis

To gauge whether the encryption framework is lossless or lossy, two parameters can be used: Peak Signal-to-Noise Ratio (PSNR) and Mean Square Error (MSE). For an efficient and lossless encryption framework, a high MSE value and a low PSNR value are always required. The relationship between MSE and PSNR is given in Eq. (29)65.

For a lossless encryption framework, the MSE value between the plaintext and the decrypted images must be zero. According to Eq. (29), this implies a PSNR value of \(\infty\). Table 5 presents the lossless analysis. The statistical values in Table 5 demonstrate that the pixel values are exactly identical after decryption. This indicates that the proposed encryption framework is lossless and capable of recovering 100% of the plaintext information. In contrast, existing comparable schemes exhibit MSE and PSNR values that are neither zero nor infinity. This indicates that these existing encryption schemes are not lossless. Although the PSNR values are not excessively high shows that the information of the plaintext image can be visualized in the decrypted image; these algorithms are not capable of recovering the exact pixel values.

Histogram analysis

The histogram provides the pixel distribution information, which is crucial for the scheme’s evaluation66. A robust encryption scheme aims for a ciphertext image histogram that is uniform, flat, and distinct from the plaintext image histogram.

Figures 10 and 11 illustrate the pixel distribution in the histograms of various images, which indicates that the encrypted images display a nearly uniform pixel distribution. Moreover, such histograms are completely different from the plaintext components histograms.

Histogram variance

Variance is a parameter that can be used to evaluate the pixel uniformity or consistency in the histogram of ciphertext images. These parameters provide the statistical values to measure the uniformity for the pixels in the histogram. It can be calculated using Eq. (30)67.

In the context of image encryption, achieving robustness involves minimizing variance in the pixel stream \(M = \{ m_1, m_2\) \(, m_3, \ldots , m_{256} \}\), where \(m_i\) denotes the pixel value at the ith position, and \(E(M) = \frac{1}{256} \sum _{i=1}^{256} m_i\). Table 6 presents a comparison of the variance values for the encoded images, showing that the histogram variance values of the proposed cryptosystem are consistently lower than those of the existing encryption methods.

Maximum deviation

The maximum deviation measures the algorithm’s effectiveness in securing the image. Larger differences in pixel values show that the encryption algorithm provides stronger security by concealing the original data more effectively. This difference can be mathematically expressed as71:

In this context, \(M\) represents the gray levels, and \(G_T\) denotes the amplitude of the difference histogram at index \(T\). A higher \(M_D\) indicates a larger difference between the ciphertext and plaintext, suggesting greater encryption effectiveness. Table 7 shows the maximum deviation results for both the proposed and existing algorithms, where it can be seen that the proposed encryption system outperforms the existing schemes.

Entropy surface map

An entropy surface map is a visualization that displays how entropy values vary across different regions of an image. In this context, entropy represents the level of randomness or unpredictability in pixel values within a specific region. This type of map is used to understand the distribution of encrypted and unencrypted regions in an image. In this work, the entropy surface map for the color images is created by calculating the local entropy in sliding windows across the image. For this analysis, the sliding window size is kept at \(4 \times 4\) pixels to ensure a fine-grained resolution of entropy values across the image. The local entropy for each window is computed, and these values are then used to generate the entropy surface map.

Figure 12 illustrates the entropy surface map for both plaintext and encrypted images. For a plaintext image (Fig. 12a–d), the entropy surface map reveals clear patterns due to the inherent structure and regularity of the image content. These predictable patterns result in low entropy values, typically close to 0, because the pixel values in these regions are highly structured and repetitive. As shown in Fig. 12, the entropy map of a plaintext image displays distinct low-entropy regions, which makes it easier for attackers to identify patterns that could be exploited in cryptanalysis. The presence of these low-entropy regions indicates that the image content is not well-obscured, making it vulnerable to various attack methods.

In contrast, Fig. 12e–h shows the entropy surface map of an encrypted image. Using the proposed encryption framework, the image undergoes transformations that randomize its content. This randomness is clearly reflected in the entropy surface map, where the image exhibits a much higher and uniform entropy distribution across the entire image. The entropy values in the encrypted image are significantly higher than the entropy values of the plaintext images. This indicates that the image has been effectively scrambled. The pixel values are now distributed in a way that appears completely random, and the entropy map shows a consistent, high-entropy pattern throughout the image. This high entropy demonstrates that the image is securely encrypted, with no predictable patterns remaining, thus significantly increasing its resistance to cryptanalysis and other cyberattacks.

3D gradient analysis

3D gradient analysis is a method used to evaluate the changes in pixel intensities across an image in three-dimensional space, accounting for the spatial dimensions and color channels. This analysis determines how the pixel values of an image change with respect to horizontal (x-axis), vertical (y-axis), and color channels (z-axis). By computing the gradients, we can assess how the pixel intensities change both spatially and in terms of color, which is crucial for understanding the effectiveness of image encryption algorithms.

In this work, the gradient is computed in two spatial dimensions (horizontal and vertical), and the third dimension corresponds to the gradient magnitude of each color channel (Red, Green, Blue). The gradients are calculated using finite differences:

-

Horizontal gradient (x-direction): The horizontal gradient for pixel \((\alpha ,\beta )\) in the image is computed by taking the difference between the pixel and its right neighbor, as shown in Eq. (32).

$$\begin{aligned} G_x(\alpha ,\beta ) = I(\alpha ,\beta +1) - I(\alpha ,\beta ) \end{aligned}$$(32)where \(I(\alpha ,\beta )\) is the pixel intensity at position \((\alpha ,\beta )\) in the image.

Vertical gradient (y-direction): Similarly, the vertical gradient for pixel \((\alpha ,\beta )\) is determined by the difference between the pixel and its lower neighbor, as expressed in Eq. (33):

$$\begin{aligned} G_y(\alpha ,\beta ) = I(\alpha +1,\beta ) - I(\alpha ,\beta ) \end{aligned}$$(33)Gradient magnitude: The gradient magnitude at each pixel is computed by combining the horizontal and vertical gradients using Eq. (34):

$$\begin{aligned} G_m(\alpha ,\beta ) = \sqrt{G_x(\alpha ,\beta )^2 + G_y(\alpha ,\beta )^2} \end{aligned}$$(34)This magnitude represents how much the pixel intensity is changing in both directions (horizontal and vertical).

Color channel gradient: The gradient calculation is performed independently for each color channel. For each color channel, the gradients in both spatial dimensions are calculated using Eq. (35).

$$\begin{aligned} \nabla I_{RGB}(\alpha ,\beta ) = \left( \frac{\partial I_{RGB}(\alpha ,\beta )}{\partial x}, \frac{\partial I_{RGB}(\alpha ,\beta )}{\partial y} \right) \end{aligned}$$(35)where \(G_x^{RGB}(\alpha ,\beta )\) is the horizontal gradient, \(G_y^{RGB}(\alpha ,\beta )\) is the vertical gradient, and \(G_m^{RGB}(\alpha ,\beta )\) is the gradient magnitude, combining both horizontal and vertical gradients.

The gradient magnitudes are then visualized in 3D space, where the x and y axes correspond to the column and row indices of the image, respectively, and the z-axis corresponds to the gradient magnitude for each color channel. The 3D surface plot or vector field helps visualize how the pixel intensities vary across the entire image and can reveal whether the image content has been randomized (as expected in an encrypted image).

Figure 13 illustrates the results of the 3D Gradient Analysis for both plaintext and encrypted images. In the case of plaintext images (Fig. 13a–c), the gradient analysis reveals smooth, predictable transitions in pixel values across the image, especially in regions with uniform or continuous color gradients. These smooth transitions indicate a lack of randomness in the image, making it easier for attackers to detect patterns for cryptanalysis.

In contrast, the encrypted image (Fig. 13d–f) shows randomized and irregular gradients. This suggests that the encryption algorithm has effectively scrambled the pixel values. The absence of smooth transitions and predictable gradients in the encrypted image indicates that the proposed encryption scheme can effectively conceal the image content, making it resistant to cryptanalysis and other types of attacks.

Computational complexity analysis

Time analysis is essential alongside security assessment to evaluate encryption algorithm performance. An 8GB RAM platform is used to measure computational time, with the MATLAB “tic toc” command used to calculate the encryption and decryption processing times. The tic-toc function calculates the processing time of the encryption algorithms as follows:

where \(F_t\) is the elapsed time, \(E_t\), and \(S_t\) are the current system time when the tic and toc functions are called, respectively. To convert this to seconds (since MATLAB typically returns time in seconds), Eq. (37) is divided by \(10^{6}\), and it becomes:

The processing times, shown in Table 8, indicate that the proposed scheme is more suitable for real-time applications than the existing schemes.

The computational complexity and execution times presented in Table 8 are based on classical simulations of the proposed quantum-inspired encryption scheme. Due to the current limitations of practical quantum hardware, all quantum operations are simulated on a classical system for evaluation purposes. As such, these results reflect classical performance benchmarks rather than actual quantum execution times.

Clipping and noise attack analysis

Attackers often add noise to encrypted images to disrupt decryption. A resilient encryption scheme must withstand such noise attacks72. In this test, 5% pixels are altered with random noise in the encrypted image, which is then decrypted. Figure 14 shows that despite the noisy encrypted image, the plaintext content is still clearly visible, even though the exact pixel values are not fully restored.

Attackers frequently attempt to introduce noise into encrypted images as a means of interfering with the decryption process. A strong and resilient encryption scheme must be able to withstand such noise attacks and still provide accurate decryption results. In this particular test, 5% of the pixels in the encrypted image are altered with salt-and-pepper noise, which randomly replaces pixel values with either black or white, simulating the impact of noise on the encrypted data. The noisy encrypted image is then subjected to decryption using the proposed algorithm.

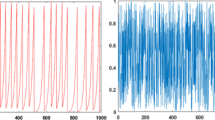

Attackers may also attempt to compromise the decryption process by clipping sections of the encrypted images. This clipping can alter or remove parts of the image, which makes it difficult to recover the original content during the decryption process. However, the proposed encryption scheme is designed to maintain the integrity of the image, even in the presence of such clipping attacks. To test the proposed encryption framework’s resistance to clipping attacks, about 18.20% of the ciphertext image was removed, and these clipped images were then decrypted. Figure 14e,f show the decryption results from noisy and clipped encrypted images, indicating that most of the plaintext content remains visible. Figure 14g,h compare our method with another encryption technique using the same chest X-ray image, demonstrating our framework’s superior ability to reconstruct plaintext information. Statistical analyses in Table 9 further show a slight improvement of our method over the referenced encryption scheme. Moreover, for multiple image analyses involving noise and cropping attacks, the corresponding noise and cropping curves are presented in Fig. 15. It is evident from the analysis that a significant amount of information can still be recovered, even as the levels of noise and cropping increase.

Correlation

The correlation between pixel values in an image indicates the degree of similarity or dissimilarity in their intensity levels. A higher difference between pixel values signifies a lower correlation. Mathematically, this relationship can be represented using Eq. (38).

Mathematically, the expression for calculating the correlation between image pixels can be represented using Eq. (39).

where \(Cov(\Omega , \phi )\) is the The covariance between the pixel values \(\Omega , \phi\). \(\rho\) is an index representing the current pixel value in the summation. E(m) is the expected value (mean) of the pixel values. \(m_w\) is the pixel value m at position w, and \(h_s\) is thr highest pixel value at position s.

In plaintext images, pixel values usually have high correlation due to the visible content. In ciphertext images, however, pixel correlation should be low to ensure that the content remains concealed. Minimizing pixel correlation in ciphertext images is crucial to prevent any visualization of the encrypted content.

Table 10 provides a comparison of the proposed and the existing encryption schemes in terms of correlation analysis. The values presented in Table 10 indicate that the proposed scheme achieves lower correlation values compared to the existing schemes.

In addition to statistical analysis, scatter plots serve as a valuable tool for visually evaluating pixel correlation within images. To further assess the correlation, scatter diagrams for the plaintext images (Baboon and X-ray) and their respective ciphertext images are shown in Fig. 16. In Fig. 16, the red dots are tightly clustered, indicating a high degree of pixel correlation, which is characteristic of the original, unencrypted images. On the other hand, the red dots are widely dispersed, which suggests a significant reduction in pixel correlation due to the encryption process. This reduction in correlation makes it significantly more difficult for attackers to extract any useful information from the ciphertext. By disrupting the inherent pixel relationships, the encryption ensures that even if the ciphertext is intercepted, the lack of predictable patterns or correlations prevents the unauthorized recovery of the original data. As a result, the security of the encrypted image is considerably strengthened, and further protects the sensitive information from decryption attempts.

Entropy

Entropy (\(S_n\)) is used to assess the strength of the visual data. A higher level of randomness in an image results in a greater entropy value, as described in Eq. (40).

The entropy calculation can be performed using the formula presented in Eq. (41).

Here, \(N\) refers to the total number of unique pixels, and \(P_i\) is the probability of each pixel’s occurrence.

All images analyzed in the experiments are eight-bit images. Therefore, each encrypted image ideally approaches or approximates an entropy value of 8. Table 11 demonstrates that the entropy values from the proposed encryption scheme closely approach 8.

Key sensitivity analysis

The security strength of an encryption algorithm is also influenced by the sensitivity of its keys. Even a minor change in the security keys can lead to a significant variation in the resulting ciphertext images. This high sensitivity ensures that any slight modification in the key values produces an entirely different encrypted output. This makes it exceedingly difficult for attackers to decrypt the data without the exact key. Consequently, the robustness of the encryption is enhanced, as unauthorized parties would struggle to break the cipher even with small variations in their attempts.

To demonstrate the key sensitivity of the proposed encryption algorithm, a small change (\(\Delta = 10^{-14}\)) is applied to the original security keys (\(\beta _1, \beta _2, \beta _3, \xi _1, \xi _2, \cdots , \xi _6, \omega _1\), and \(\omega _2\)). After a minor change is made to the original secrete keys, the modified can be represented as: \(\beta ^{*}_1 = \beta _1 + \Delta\), \(\beta ^{*}_2 = \beta _2 + \Delta\), \(\beta ^{*}_3 = \beta _3 + \Delta\), \(\xi ^{*}_1 = \xi _1 + \Delta\), \(\xi ^{*}_2 = \xi _2 + \Delta , \ldots , \xi ^{*}_6 = \xi _6 + \Delta\), \(\omega ^{*}_1 = \omega _1 + \Delta\), and \(\omega ^{*}_2 = \omega _2 + \Delta\). The altered keys are subsequently employed to decrypt the plaintext image. Figure 17 presents the key sensitivity analysis of the proposed cryptosystem. Specifically, Fig. 17a displays the original plaintext image, while Fig. 17b shows its corresponding ciphertext. Figure 17c,d illustrate the decrypted images using an incorrect and the correct secret key, respectively. As demonstrated, even a minor alteration in the secret key leads to a failed decryption which highlights the system’s strong key sensitivity.

Key space analysis

Key space analysis assesses the resistance of a cryptosystem against brute-force attacks by evaluating the total number of possible key combinations. A secure encryption scheme must have a sufficiently large key space such that it is computationally infeasible for an attacker to exhaustively search all possible keys. According to Alvarez and Li75, a minimum key space of \(10^{100} \approx 2^{332}\) is recommended to ensure resilience against brute-force attacks.

In the proposed encryption framework, a total of 11 independent security keys are utilized: \(\beta _1, \beta _2, \beta _3, \xi _1, \xi _2, \dots , \xi _6, \omega _1,\) and \(\omega _2\). Each key is assumed to have a precision of \(10^{-14}\), implying that it can take \(10^{14}\) different values. Therefore, for each key: \(\text {the key space per key} = 10^{14}\). Therefore, the total key space becomes: \(\text {Total key space} = (10^{14})^{11} = 10^{154}\). To express this in terms of binary entropy (as required in cryptography), convert the decimal key space to bits according to Eq. (42).

Thus, the total key space is approximately \(2^{650}\). This value is significantly greater than the recommended threshold of \(2^{332}\), which shows that the proposed encryption system possesses a sufficiently large key space to resist brute-force attacks.

Quantum attack analysis with statistical justification

To evaluate the resistance of the proposed encryption system against quantum attacks, the performance of the proposed system under quantum computing scenarios is analzyed, particularly considering Grover’s and Shor’s algorithms, as well as quantum-aided differential and brute-force attacks. Moreover, empirical results are also used from classical cryptographic metrics (key sensitivity and maximum deviation) to support our quantum-resistance claims.

Resistance to Grover’s algorithm

Grover’s algorithm allows a quantum adversary to perform a brute-force key search with quadratic speedup, reducing the complexity from \(O(2^n)\) to \(O(2^{n/2})\), where O is the asymptotic upper bound of an algorithm’s complexity. From the key space analysis, the total key space of the proposed scheme is approximately \(\approx 2^{650}\) as mentioned in Section “Key space analysis”. Thus, even with Grover’s advantage, the effective key search complexity becomes: \(2^{650/2} = 2^{325}\).

This value is significantly above the post-quantum security benchmark of \(2^{128}\), which shows that the proposed system provides strong resistance against quantum brute-force attacks.

Key sensitivity as quantum oracle obfuscation

In quantum cryptanalysis, adversaries may exploit oracles by querying in superposition to extract patterns. However, the key sensitivity analysis (Section “Key sensitivity analysis”) shows that even a minimal change (\(\Delta = 10^{-14}\)) in any security parameter results in complete decryption failure.

A decrypted image using a perturbed key set (e.g., \(\beta _1 + \Delta\)) leads to visual and statistical corruption (see Fig. 17c). This ensures a flat key landscape under quantum queries, which provides a strong resistance to Grover-amplified oracle-based attacks.

Quantum differential attack resilience

Quantum differential cryptanalysis leverages entangled queries to reduce the number of plaintext-ciphertext pairs required. However, the proposed algorithm exhibits strong resistance to such attacks due to high ciphertext entropy and structural obfuscation.

Supporting Evidence: The MD results in Table 7 consistently show that the proposed method produces ciphertexts with significantly larger differences compared to existing techniques. For instance:

-

Quantum image: MD = 26793 (Proposed), vs. 25989 (27)

-

Circuit image: MD = 26318 (Proposed), vs. 25968 (68)

Higher MD values indicate better encryption strength and disruption of pixel correlations, which reduces vulnerability to any structural quantum cryptanalytic strategy.

Summary of quantum security strength

A brief overview of the quantum attack analysis performed to demonstrate the proposed encryption system’s resistance to quantum attacks is presented in Table 12.

The combination of a large key space, extreme key sensitivity, and high statistical deviation results indicates that the proposed algorithm provides effective resistance against a wide range of quantum attack models.

Conclusion

The proposed research presents a new quantum-integrated cryptographic framework that combines fused cryptographic techniques to improve both the efficiency and security of digital data. There are several vulnerabilities related to weak security, high computational overhead mentioned in this research. Based on the existing encryption schemes vulnerabilities, multiple encryption methods such as quantum principles like quantum XOR operations, quantum random numbers, and quantum key image generation are integrated with the classical encryption techniques like bit-plane extraction, multiple permutations, and chaos theory. By integrating such cryptography methods, the proposed framework achieves robust encryption capabilities. The experimental results provide demonstrate strong statistical metrics such as high entropy values, minimal correlation, and resilience against noise and clipping attacks. These findings show the effectiveness of the proposed hybrid approach in protecting sensitive image data against cyberattacks. However, the proposed algorithm has a few limitations. While the proposed encryption system improves computational efficiency by encrypting only high-information bit-planes, the overall system still involves multiple processing stages such as chaotic permutation, quantum encoding, and scrambling, which can lead to increased time complexity compared to lightweight schemes. Second, the reliance on classical simulation of quantum components (e.g., NEQR and quantum walks) means the current implementation is not yet deployable on true quantum hardware. Third, the proposed method is primarily designed for image data, and its scalability to video streams or large-scale datasets has not yet been validated. Moreover, owing to the current limitations of available quantum hardware, all quantum operations in this study are evaluated through classical simulations. The performance on future quantum platforms is expected to differ and is an open area for further investigation.

In the future, we aim to address these limitations by incorporating advanced quantum operations such as quantum entanglement and teleportation, which may enable more efficient and hardware-native encryption strategies. Additionally, to further reduce the computational load, we plan to integrate Discrete Wavelet Transform (DWT) with the current framework, enabling selective frequency-domain encryption and improved speed-performance trade-offs.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Subramani, S. & Svn, S. K. Review of security methods based on classical cryptography and quantum cryptography. Cybern. Syst. 56, 302–320 (2025).

Vasani, V., Prateek, K., Amin, R., Maity, S. & Dwivedi, A. D. Embracing the quantum frontier: Investigating quantum communication, cryptography, applications and future directions. J. Ind. Inf. Integr. 100594 (2024).

Robert, W. et al. A comprehensive review on cryptographic techniques for securing internet of medical things: A state-of-the-art, applications, security attacks, mitigation measures, and future research direction. Mesopotamian J. Artif. Intell. Healthcare 2024, 135–169 (2024).

Sharma, P., Namasudra, S., Crespo, R. G., Parra-Fuente, J. & Trivedi, M. C. Ehdhe: Enhancing security of healthcare documents in iot-enabled digital healthcare ecosystems using blockchain. Inf. Sci. 629, 703–718 (2023).

Ahmed, S. & Khan, M. Securing the internet of things (IoT): A comprehensive study on the intersection of cybersecurity, privacy, and connectivity in the iot ecosystem. AI IoT Fourth Ind. Revolut. Rev. 13, 1–17 (2023).

Bader, J. & Michala, A. L. Searchable encryption with access control in industrial internet of things (IIoT). Wirel. Commun. Mob. Comput. 2021, 5555362 (2021).

Hussain, I., Anees, A., AlKhaldi, A. H., Algarni, A. & Aslam, M. Construction of chaotic quantum magnets and matrix Lorenz systems s-boxes and their applications. Chin. J. Phys. 56, 1609–1621 (2018).

Zaid, B. et al. Toward secure and resilient networks: a zero-trust security framework with quantum fingerprinting for devices accessing network. Mathematics 11, 2653 (2023).

Khatri-Valmik, M. N. & Kshirsagar, V. Blowfish algorithm. IOSR J. Comput. Eng. (IOSR-JCE) 16, 80–83 (2014).

Tsiounis, Y. & Yung, M. On the security of elgamal based encryption. In International Workshop on Public Key Cryptography, 117–134 (Springer, 1998).

Selent, D. Advanced encryption standard. Rivier Acad. J. 6, 1–14 (2010).

Wang, J., Geng, Y.-C., Han, L. & Liu, J.-Q. Quantum image encryption algorithm based on quantum key image. Int. J. Theor. Phys. 58, 308–322 (2019).

Kuang, R. & Perepechaenko, M. Quantum encryption with quantum permutation pad in IBMQ systems. EPJ Quantum Technol. 9, 26 (2022).

Hua, T., Chen, J., Pei, D., Zhang, W. & Zhou, N. Quantum image encryption algorithm based on image correlation decomposition. Int. J. Theor. Phys. 54, 526–537 (2015).

Alwakeel, A. M. An overview of fog computing and edge computing security and privacy issues. Sensors 21, 8226 (2021).

Hussain, I., Anees, A. & Al-Maadeed, T. A. A novel encryption algorithm using multiple semifield s-boxes based on permutation of symmetric group. Comput. Appl. Math. 42, 80 (2023).

Ghaffari, A. Image encryption-compression method via encryption based sparse decomposition. Multimedia Tools Appl. 83, 19129–19160 (2024).

Kumar, R., Kumar, P., Aloqaily, M. & Aljuhani, A. Deep-learning-based blockchain for secure zero touch networks. IEEE Commun. Mag. 61, 96–102 (2022).

Kumar, Y. & Guleria, V. Mixed-multiple image encryption algorithm using RSA cryptosystem with fractional discrete cosine transform and 2d-Arnold transform. Multimedia Tools Appl. 83, 38055–38081 (2024).

Hao, W., Zhang, T., Chen, X. & Zhou, X. A hybrid neqr image encryption cryptosystem using two-dimensional quantum walks and quantum coding. Signal Process. 205, 108890 (2023).

Song, X.-H., Wang, H.-Q., Venegas-Andraca, S. E. & Abd El-Latif, A. A. Quantum video encryption based on qubit-planes controlled-xor operations and improved logistic map. Physica A 537, 122660 (2020).

Chen, Z., Yan, Y., Pan, J. & Zhu, H. Cyclic shift-based mqir image encryption scheme. Quantum Inf. Process. 21, 175 (2022).

Hu, M., Li, J. & Di, X. Quantum image encryption scheme based on 2d s ine 2-l ogistic chaotic map. Nonlinear Dyn. 111, 2815–2839 (2023).

Arfaoui, S., Alshehri, M. G. & Ben Mabrouk, A. A quantum wavelet uncertainty principle. Fractal Fractional 6, 8 (2021).

Bezerra, J. I. M., Machado, G., Molter, A., Soares, R. I. & Camargo, V. A novel simultaneous permutation-diffusion image encryption scheme based on a discrete space map. Chaos Solitons Fractals 168, 113160 (2023).

Wen, H., Huang, Y. & Lin, Y. High-quality color image compression-encryption using chaos and block permutation. J. King Saud Univ. Comput. Inf. Sci. 35, 101660 (2023).

Zhang, J. et al. Quantum image encryption based on quantum image decomposition. Int. J. Theor. Phys. 60, 2930–2942 (2021).

Ovalle-Magallanes, E., Alvarado-Carrillo, D. E., Avina-Cervantes, J. G., Cruz-Aceves, I. & Ruiz-Pinales, J. Quantum angle encoding with learnable rotation applied to quantum-classical convolutional neural networks. Appl. Soft Comput. 141, 110307 (2023).

Al-Maadeed, T. A., Hussain, I., Anees, A. & Mustafa, M. T. A image encryption algorithm based on chaotic Lorenz system and novel primitive polynomial s-boxes. Multimedia Tools Appl. 80, 24801–24822 (2021).

Akhshani, A., Akhavan, A., Lim, S.-C. & Hassan, Z. An image encryption scheme based on quantum logistic map. Commun. Nonlinear Sci. Numer. Simul. 17, 4653–4661 (2012).

Liu, X., Xiao, D. & Liu, C. Three-level quantum image encryption based on Arnold transform and logistic map. Quantum Inf. Process. 20, 1–22 (2021).

Joshi, A. B., Kumar, D., Gaffar, A. & Mishra, D. Triple color image encryption based on 2d multiple parameter fractional discrete Fourier transform and 3D Arnold transform. Opt. Lasers Eng. 133, 106139 (2020).

Anees, A., Siddiqui, A. M. & Ahmed, F. Chaotic substitution for highly autocorrelated data in encryption algorithm. Commun. Nonlinear Sci. Numer. Simul. 19, 3106–3118 (2014).

Han, J. et al. Performance of logistic regression and support vector machines for seismic vulnerability assessment and mapping: A case study of the 12 september 2016 ml5. 8 gyeongju earthquake, south korea. Sustainability 11, 7038 (2019).

Liu, X., Xiao, D. & Liu, C. Quantum image encryption algorithm based on bit-plane permutation and sine logistic map. Quantum Inf. Process. 19, 239 (2020).

Hu, W.-W., Zhou, R.-G., Luo, J., Jiang, S.-X. & Luo, G.-F. Quantum image encryption algorithm based on Arnold scrambling and wavelet transforms. Quantum Inf. Process. 19, 1–29 (2020).

Alawida, M. A novel chaos-based permutation for image encryption. J. King Saud Univ. Computer Inf. Sci. 35, 101595 (2023).