Abstract

Studying the fracture properties of rocks under high temperatures is crucial for understanding the laws of crack propagation and fracture mechanisms in deep underground engineering. In this study, based on digital image correlation technique, fracture tests were conducted on heat-treated limestone specimens under monotonic (ML) and cyclic loading (CL). The fracture properties including the peak load (Pmax), normal stresses (i.e., σn and σN) considering and without considering the influence of the crack, critical mid-span deflection (δc), and critical crack mouth and tip opening displacement (CMODc and CTODc) of the specimens were calculated, and the influences of heat-treated temperature (T) and loading modes (i.e., ML and CL) on the above parameters were studied. In addition, by investigating the changes in fracture process zone (FPZ) of the specimens under CL and ML, the fracture mechanics of the specimens were obtained. The results show that whether under CL or ML, as T increases, Pmax, σn and σN all gradually decrease, while CMODc, CTODc and δc all gradually increase, indicating that the heat-treated process enhances the deformation performance of limestone, but reduces its bearing capacity. For a specimen after the heat-treated process, as the loading progresses, the FPZ length undergoes an initial increase followed by a decrease. For specimens after different high temperatures, as T increases, the fully developed FPZ length gradually increases, but the change in the fully developed FPZ width is small. This indicates that the heat-treated process can lead to an increase in the nonlinearity of limestone, but has little effect on the volume of mineral particles.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Fracture mechanics plays an important role in rock engineering, serving dual objectives: preventing crack propagation to ensure structural integrity of underground excavations (e.g., tunnels and subway stations)1 and promoting controlled fracture growth for efficient resource extraction (e.g., geothermal energy and shale gas)2,3,4. Consequently, precise characterization of rock fracture behavior is fundamental to both structural safety and resource utilization efficiency.

Sedimentary rocks—the most widely distributed rocks on the Earth’s surface—exhibit fracture properties highly susceptible to environmental factors, particularly high temperatures and cyclic loads (such as earthquakes). These perturbations are ubiquitous during subsurface operations, for instance, when developing underground resources, reservoir rocks undergo temperature changes and pose a risk of earthquakes5 which have an important impact on their mechanical properties and fracture behavior. Currently, there are still some issues in the research on the fracture characteristics of sedimentary rocks: (1) The research on fracture characteristics is mostly focused on rocks such as shale6 and sandstone7 with a single type of rock under study. However, different rocks have inconsistent constituent minerals, and there are significant differences in the fracture characteristics of different rocks under the influence of temperature6,7. (2) The loading mode is singular, with most studies concentrating on monotonic loading (ML) scenarios8,9 and the impact of cyclic loading (CL) has hardly been explored, despite its relevance to earthquakes/operational cycles.

In addition to the aforementioned research deficiencies, there are also shortcomings in the current research on fracture process zone (FPZ)—the dominant source of nonlinearity in thermally damaged rocks10,11. To understand the generation and development mechanism of nonlinearity inside rock materials, some scholars have conducted research on the evolution of the FPZ. For example, Wang and Lv12,13 studied the changes in the FPZ length of heat-treated Lu gray granite single edge-notched bending beams; Miao et al.14 investigated the changes in the FPZ length of heat-treated Beishan granite semi-circular bending specimens; Yang15 researched the changes in the FPZ of oil shale specimens under high temperatures. However, the change law of the FPZ with heat-treated temperature of different rocks studied by different scholars seems to have some differences12,13.

The possible reasons for the inconsistent patterns of FPZ changes observed by different scholars may lie in the unadvanced observation methods and insufficient observational accuracy. In recent years, numerous advanced techniques have been promoted and applied in the field of civil engineering16,17. Among them, digital image correlation (DIC) technique is commonly employed for measuring the deformation of rock materials. For example, based on the DIC, Tang et al.18 studied the deformation and failure behaviors of tuff; Ji et al.19 researched the fracture properties of semi-circular bending beams of marble and yellow sandstone; Wei et al.20 focused on studying the changes in cracks within rock-concrete materials; while Yao et al.21 investigated the relationship between the fracture properties of rock-concrete interface and loading rate. It has been confirmed that using the DIC technique to measure rock deformation is reliable, so the DIC technique was employed in this study.

Limestone is a typical sedimentary rock widely distributed across the globe; an investigation into the fracture characteristics of limestone under high temperatures and cyclic loading is imperative. In this study, focused on heat-treated limestone beams, fracture tests were conducted under ML and CL based on the DIC. Firstly, the mechanics and deformation properties of the heat-treated beams were studied. Subsequently, the changes in the FPZ were investigated after the FPZ tip and rear were identified through the application of a dynamic strain threshold and characteristic opening displacement respectively. Finally, the effects of heat-treated temperature (T) on the fully developed FPZ were analyzed.

Experiment

DIC technique

The DIC technique is an optical measurement technique, which has the advantages of simple data acquisition, low requirements of measurement environment and simple specimen surface treatment, etc. The DIC measurement system consists of two primary components: hardware and software. The former mainly includes light sources, cameras and computers, etc., as shown in Fig. 1.

When using the DIC post-processing software to calculate the specimen deformation, the software first identifies all of the subsets of the speckle image, and derives the grayscale characteristic value of each subset. Subsequently, it performs correlation calculations on the subsets between the reference and deformation images, and obtains the specimen displacement based on the calculation results. Once the displacement is obtained, the strain can be obtained by using the Cauchy equation. In the present research, VIC-2D served as the tool for computing the specimen deformation, utilizing zero-normalized sum of squared difference coefficient as the correlation function22. The area of interest for the analysis is about 50 mm × 50 mm. The camera resolution and acquisition rate are 4872 × 3248 pixels and 0.2 Hz, respectively.

Test preparation

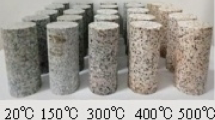

The limestone utilized in the tests originated from Hebei province, China, with the largest mineral particle size about 107 µm23. The elemental composition of the limestone mainly includes calcium (23%) and magnesium (0.2%). According to the order of chemical affinity and the ratio of molecular weights24,25 dolomite accounts for 2.26% of calcite23.

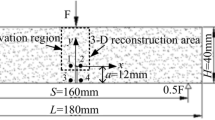

To determine the mode I fracture properties of quasi-brittle materials, the ISRM recommended four shapes of specimens26,27,28. In addition, the ASTM recommended two shapes of specimens29. To cooperate with the use of DIC equipment and better observe the fracture characteristics of the specimen surface, the single edge-notched bending specimens were selected here for the fracture mechanics test of limestone.

When making the heat-treated limestone beams, the dimensions of the beams meet the requirements of ASTM30 and the length, width and height (L × B× H) are selected as 220 mm, 25 mm and 50 mm, respectively. The initial crack length (a0) and span (S) are selected as 15 mm and 200 mm, respectively. When using a sand-line cutting machine to make the initial crack, the diameter of the sand-line is selected as 0.3 mm, and the thickness of the initial crack is controlled within 1 mm. Table 1 displays the prepared specimens.

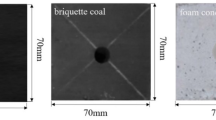

After the specimens had been cut to the specified dimensions, an oven was used to heat the specimens, as depicted in Fig. 2. First, a heating rate of 1 ℃/min was applied to the specimen, after which a target temperature was maintained for 2 h to ensure uniform temperature inside and outside the specimen. Subsequently, the specimen was cooled down to room temperature (25 ℃) in the oven. In the present research, seven target temperatures were selected, ranging from 25 ℃ to 475 ℃, as shown in Table 1. For each combination of target temperature and loading mode, three specimens were tested (see Table 1). Notably, 475 ℃ was set as the highest heat-treatment temperature (T) because obvious cracks were seen on specimens heated to this temperature. After the heat-treated process, a layer of speckles was sprayed onto the specimen surface for compatibility with the DIC. The resultant speckle pattern is illustrated in Fig. 3.

Test process

Before conducting the fracture tests of the heat-treated limestone beams, two LVDTs were positioned on either side of the crack mouth to record mid-span deflection (δ). Simultaneously, a clip gauge was installed at the crack mouth to quantify crack mouth opening displacement (CMOD). Furthermore, a DIC camera (the technical specifications of the camera are shown in Table 2) was set up facing the specimen to capture its surface deformation. Auxiliary lighting sources were positioned on both sides of the camera to guarantee optimal clarity and saturation of the specimen surface, thereby facilitating better analysis of the taken speckle images. When conducting the fracture tests, a 50 kN MTS was used to load the specimens (see Fig. 4). When conducting the ML tests, the specimens were loaded with a speed of 0.1 mm/min. When conducting the CL tests, they were loaded at the same rate but unloaded at 0.1 kN/min.

Results and discussion

Validation of the DIC technique

Figure 5 displays the relationships between the specimen loading time (t) and CMOD of ML-325-2 and CL-325-2 specimens. The changes in the CMOD can be roughly divided into 3 stages under ML: (1) Slow development stage. In the early stage of loading, the CMOD development is relatively slow, so the specimen is in an elastic state. (2) Development rate increase stage. When microcracks begin to appear in the specimen, the transition from elasticity to plasticity occurs locally in the specimen, and the CMOD development rate gradually accelerates. (3) Rapid development stage. At the beginning of this stage, cracks in the specimen begin to develop unstably, and the CMOD development rate remains basically unchanged (see Fig. 5a). Regardless of whether under ML or CL, the CMOD-t curves obtained through the clip gauge are basically consistent with those calculated by the DIC (see Fig. 5a and b), indicating that the application of the DIC for measuring the deformation of the specimen surface is both precise and practicable.

Load-displacement curves

The P-CMOD curves of the heat-treated limestone beams under CL and ML are presented in Fig. 6. As T increases, the slope of the pre-peak P-CMOD curve gradually decreases, indicating that the heat-treated process would reduce the stiffness of the specimen. Furthermore, the load decreasing rate after the peak gradually slows down, indicating that the ductility of the specimen would be influenced by the heat-treated process.

The change in the area under the P-CMOD curve (AP−CMOD) as T increases is shown in Fig. 7. Under ML, when T ≤ 325 ℃, as T increases, AP−CMOD gradually increases, indicating that the increase in the deformation performance caused by the heat-treated process is more significant than the decrease in bearing capacity. When T ≥ 325 ℃, AP−CMOD seems to decrease, indicating that the decrease in bearing capacity is more significant than the increase in the deformation performance. In general, when T ≤ 475 ℃, the heat-treated process increases the fracture energy of the specimens (see Fig. 7a). Under CL, as T increases, AP−CMOD first increases and then decreases (see Fig. 7b), which is consistent with that under monotonic loading.

The change pattern of AP−CMOD distinctly indicates that the thermal damage process of limestone involves a two-stage competitive mechanism. When T is relatively low, the frictional energy dissipation among microcracks is significantly enhanced, causing the improvement in the material’s deformation capacity to outweigh the extent of bearing capacity loss. When T is relatively high, the thermal stress generated by rock expansion and the disintegration effect of calcite will lead to bearing capacity degradation becoming the dominant factor, thereby triggering the attenuation of fracture energy.

Peak load and normal stresses

Figure 8 displays the relationship between Pmax and T. Pmax exhibits a decrease as T increases under ML (see Fig. 8a), indicating that the specimen would be damaged during the heat-treated process. When T increases from 25 ℃ to 475 ℃, the Pmax decreases from 1.165 kN to 0.381 kN. A consistent conclusion was obtained by Yin et al.32 when they studied the influence of T on Pmax of granite semi-circular bending specimens. They pointed out that when T increases from 25 ℃ to 800 ℃, the Pmax of granite decreases from 1.708 kN to 0.152 kN.

Under CL, as T increases, Pmax gradually decreases (see Fig. 8b), which is consistent with that under monotonic loading. When T increases from 25 ℃ to 475 ℃, the Pmax decreases from about 1.21 kN to 0.39 kN.

After the peak loads of the specimens are known, normal stresses (i.e., σn and σN) considering and without considering the influence of the crack can be calculated:

Where α0 is the crack to height ratio, α0 = a0/H. As T increases, the changes in σN and σn under ML and CL are shown in Fig. 9. As T increases, both σN and σn gradually decrease. When T increases from 25 ℃ to 475 ℃, the σN decreases from 5.59 MPa to 1.83 MPa under ML, while it decreases from 5.81 MPa to 1.85 MPa under CL. The observed variation patterns of peak load and nominal stresses with temperature can be attributed to the following factors: (1) Dehydration occurring within the temperature range of 25℃–250℃ weakens the intergranular bonding force. (2) Thermal expansion disparities between 250℃–400℃ trigger the formation of microcracks. (3) Calcite decomposition at temperatures exceeding 400℃ results in structural collapse.

Deformation behaviors

The effect of T on critical CMOD (CMODc) is shown in Fig. 10. Under ML, as T increases, CMODc gradually increases (see Fig. 10a), indicating that the heat-treated process can enhance both the plastic deformation capability and the ductile behavior of limestone materials. When T increases from 25 ℃ to 475 ℃, the CMODc experiences an increase, ranging from about 0.0120 mm to 0.0482 mm. A similar phenomenon has been discovered by Wang12Lv13 and Yin et al.32 when they studied the fracture properties of granite. Under CL, CMODc varies with T in a manner consistent with that observed under monotonic loading, and as T increases from 25 ℃ to 475 ℃, the CMODc experiences an increase, ranging from about 0.0117 mm to 0.0530 mm (see Fig. 10b).

Figure 11 displays the effect of T on critical CTOD (CTODc). As T increases, CTODc gradually increases under both CL and ML. A similar phenomenon has been discovered by Wang12Lv13 and Yin et al.32 when they studied the fracture properties of heat-treated granite. When T is 25 ℃, the CTODc is 0.0033 mm under ML and 0.0028 mm under CL. When T is 475 ℃, the CTODc is 0.0293 mm under ML and 0.0237 mm under CL.

Figure 12 displays the relationship between T and critical δ (δc). As T increases, δc gradually increases under both CL and ML. Wang12 found a similar phenomenon when investigating the fracture properties of granite. When T is 25 ℃, the δc is 0.0194 mm under ML and 0.0159 mm under CL. When T is 475 ℃, the δc is 0.0737 mm under ML and 0.0725 mm under CL.

When T is within the range of 25℃ to 250℃, the evaporation of free water and adsorbed water weakens the capillary forces and van der Waals forces between minerals, thereby reducing the bonding strength at grain boundaries and making microcracks more prone to propagation and opening. Consequently, within this temperature range, CMODc, CTODc and δc all gradually increase with rising temperature. When T rises to the range of 250℃ to 400℃, differences in the thermal expansion coefficients between calcite (the primary mineral in limestone) and impurity minerals (such as quartz and clay) generate thermal stresses at grain boundaries, inducing the formation of microcracks. Therefore, within this temperature interval, CMODc, CTODc and δc also gradually increase as the temperature rises. When T exceeds 400℃, calcite begins to decompose, generating gas pore pressure, which accelerates crack propagation. Thus, at temperatures above 400℃, CMODc, CTODc and δc continue to gradually increase with rising temperature.

Effect of loading modes on fracture properties

K-Means clustering algorithm is a typical distance-based clustering algorithm that has wide applications in unsupervised learning33. K represents the number of clusters. The basic idea of the algorithm is as follows: After the value of K is determined, K data points are randomly selected from the dataset as the initial cluster centers. Then, the distances from other data points to these initial cluster centers are calculated, and each data point is assigned to the cluster with the nearest cluster center. Next, the cluster center of each cluster (i.e., the mean of all data points within that cluster) is recalculated, and the process is repeated until the cluster centers no longer change or a preset number of iterations is reached.

The K-Means clustering algorithm was used to analyze the influence of loading modes on the fracture properties here. When using the algorithm, four feature variables were selected, namely ΔCMODc, ΔCTODc, Δδc and ΔPmax, respectively. These can be calculated as follows:

Where Y represents the fracture parameters; Ῡ represents the average value of Y at a certain temperature. Based on the test results, the four calculated feature variables are shown in Table 3.

The computational results of the K-Means clustering algorithm are presented in Table 3. It can be observed that the loading modes and the value of K are not uniform; specifically, Loading Mode 1 corresponds to both cases where K = 1 and K = 2. This indicates that the influence of loading modes on fracture characteristics is not significant.

Evolution of the FPZ

Boundary of the FPZ

For the purpose of observing the development of the FPZ in the limestone beams, determining the rear, tip and boundary of the FPZ is the first step. Since the strain field, derived from the gradient of directly measured displacement through numerical smoothing techniques34 exhibits lower accuracy compared to the displacement field, the latter was chosen for assessing the FPZ width.

When the filter size is taken as the minimum value (5 px), and the step size is taken as 7 px, 9 px, 11 px, 14 px and 21 px respectively, the displacement jumps of the line M1N1 (which is located above the initial crack tip and see Fig. 13) of ML-400-2 beam at the peak is plotted in Fig. 14. Obviously, the step size exhibits negligible influence on the horizontal displacement jump (Δw) of the specimen, and on the position of the left (x1) and right (x2) points of the displacement jump. Consequently, it is reasonable to assume that the FPZ is located between points x1 and x2, and its width (wFPZ) is equal to Δx = x2 -x135.

When the filter size and step size are taken as 5 px and 9 px respectively, the strain along the horizontal line M1N1 (see Fig. 13) of ML-400-2 beam at the peak is shown in Fig. 15. Obviously, the width of the strain concentration zone (SCZ) is 1.928 mm, and the error with the wFPZ (1.636 mm) is only 0.292 mm. Because the error is small, it can be considered that the FPZ is located within the region enveloped by strain ε1 (corresponding to point x1)35. Due to the smaller filter is not sufficient to remove the influence of noise, the strain ε1 at point x1 may change slightly at different loading points. To accurately determine the boundary of the FPZ, the ε1 value at point x1 at each loading point needs to be calculated.

When the specimen starts to crack, the FPZ rear is at the initial crack tip; as the loading continues, the FPZ rear would develop upwards. Therefore, the steps for determining the boundary of the FPZ are as follows:

(1) Extracting the horizontal displacement of points on the line M1N1 (see Fig. 13) and determining the values of x1 and x2.

(2) Extracting the horizontal strain of the line M1N1 (see Fig. 13) and determining the strain ε1 at point x1.

(3) Setting i horizontal lines MiNi (i = 1, 2, ……, n) along the direction parallel to the initial crack (see Fig. 13). Determining the FPZ rear according to the Δw of the line MiNi (y = yi): If the Δw of the line M1N1 (y = y1) is less than or equal to characteristic opening displacement (ws), the FPZ rear is at the initial crack tip. Otherwise, if the Δw of the line MiNi (y = yi) reaches the ws, the FPZ rear develops to that position. The ws can be calculated according to the tensile softening curve.

(4) Calculating the SCZ enveloped by the strain ε1, and the SCZ located above the FPZ rear can be regarded as the FPZ range, and the vertical distance measured from the FPZ rear to its tip is equal to the FPZ length (lFPZ).

Taking ML-100-2 beam as an example, when the FPZ rear is at the initial crack tip, Fig. 16 displays the changes in the FPZ. Obviously, as the loading continues, the lFPZ increases gradually.

When the FPZ rear develops upwards, Fig. 17 displays the evolution of the FPZ. Obviously, the lFPZ gradually decreases as the loading proceeds. By analyzing the development of the FPZ, it is found that when the Δw at the initial crack tip reaches the ws (about 24.41 × 10−3 mm), the fully developed FPZ is obtained.

Development process of the FPZ

Figure 18 displays the P-lFPZ and lFPZ-t curves of ML-400-2 beam to investigate the changes in the FPZ length under ML. Notably, the P-lFPZ curve under ML comprises 4 segments, namely OA, AB, BC and CD segments36. In the OA segment, the specimen deformation is small, and the load is less than the crack initiated load. In the AB segment, due to the generation and aggregation of microcracks, the FPZ begins to form and steadily develops. In the BC segment, as the main crack develops, the lFPZ increases progressively, but the load that the specimen can withstand gradually diminishes. In the CD segment, due to boundary effect16,37 the lFPZ gradually decreases. At the Pmax, the lFPZ is about 6.95 mm (see Fig. 18a). At the post-peak 57.17% Pmax, the FPZ length reaches its maximum value (lmFPZ, about 20.29 mm).

The lFPZ-t curve, similar to the P-lFPZ curve, also consists of 4 stages, as illustrated in Fig. 18b. Point A is the crack initiated point, before which the lFPZ is close to zero. After the crack initiation, the lFPZ begins to grow steadily. After the peak point B, the crack propagation speed significantly accelerates and begins to propagate unstable. At point C, the FPZ reaches its maximum value.

Length of the FPZ

Figure 19 displays the relationship between lmFPZ and T. Obviously, the dispersion of the lmFPZ is relatively large, which may be due to different pores and defects inside different specimens. In addition, due to the mechanical response of the material is not very sensitive to the change in the ws, the selection of which may also lead to discrete problems. In general, as T increases, lmFPZ gradually increases. The reason lies in the fact that a series of physicochemical changes occur in the limestone during the heating process: when T is within the range of 25℃ to 250℃, the moisture (comprising free water and adsorbed water) within the specimen undergoes evaporation, consequently weakening the bonding strength at the grain boundaries; when T is between 250℃ and 400℃, minerals exhibit uneven expansion; and when T exceeds 400℃, minerals undergo phase transformation. These changes all lead to an expansion of the fracture zone at the initial crack tip, thereby causing lmFPZ to gradually increase. This phenomenon is in line with the findings of the previous research12,38 which focused on the change patterns of heat-treated rocks.

Width of the FPZ

The relationship between the fully developed FPZ width (wmFPZ) and T is shown in Fig. 20. Obviously, the dispersion of the wmFPZ is relatively large, which may be due to different pores and defects inside different specimens. Some scholars consider that wmFPZ is related to the maximum particle size (dmax)39,40,41. For example, Bazant39 found wmFPZ is approximately 3dmax. Zhou et al.40 found that wmFPZ is less than 3dmax; Skarżyński et al.41 found that wmFPZ of sand concrete (dmax ≈ 3 mm) and crushed concrete (dmax ≈ 8 mm) varied from 3.5 mm to 5.5 mm. For limestone, its mineral grain size distribution constitutes a natural scale constraint, and wmFPZ is mainly dominated by the characteristic grain size. As T increases, the wmFPZ of limestone beams shows a gradually increasing trend, but the magnitude of this change is relatively small. The reason is that when limestone is exposed to a high-temperature environment, mineral particles undergo expansion. However, since the degree of expansion of mineral particles induced by high temperature is not significant, despite the temperature rise, the wmFPZ only experiences a certain degree of increase, and this increase is not prominent.

Conclusion

In this study, focused on the heat-treated limestone beams, fracture tests were conducted employing the DIC technique. The effects of loading modes and heat-treated temperature (T) on the fracture properties of the specimens were investigated. Furthermore, the fracture mechanics of the specimens were analyzed by investigating the development of the FPZ. The main conclusions are as follows:

-

(1)

Regardless of whether under monotonic or cyclic loading, as T increases, the Pmax gradually decreases, while critical CMOD, CTOD and δ all gradually increase. The occurrence of this phenomenon is mainly attributed to the different physicochemical changes taking place inside the specimen within various temperature ranges. When T is between 25 °C and 250 °C, under the influence of high temperature, the free water and adsorbed water within the specimen evaporate, a process that weakens the capillary forces and van der Waals forces between mineral particles. When T ranges from 250 °C to 400 °C, uneven expansion occurs among different mineral particles, leading to the formation of microcracks. And when T exceeds 400 °C, calcite decomposes, and the resulting pore pressure accelerates the propagation of cracks.

-

(2)

K-Means clustering algorithm was used to investigate the influence of loading modes on the fracture properties, and the results showed that there is no significant effect of loading modes on the fracture properties. This indicates that the fracture response of limestone is dominated by thermal damage rather than load path.

-

(3)

Regardless of whether under monotonic or cyclic loading, as T increases, the area under the P-CMOD curve (AP−CMOD) first increases and then decreases. This phenomenon distinctly indicates that the thermal damage process of limestone involves a two-stage competitive mechanism. When T is relatively low, the frictional energy dissipation among microcracks is significantly enhanced, causing the improvement in the material’s deformation capacity to outweigh the extent of bearing capacity loss. When T is relatively high, the thermal stress generated by rock expansion and the disintegration effect of calcite will lead to bearing capacity degradation becoming the dominant factor, thereby triggering the attenuation of fracture energy.

-

(4)

As the loading progresses, the FPZ length (lFPZ) undergoes an initial increase, followed by a decrease. The initial increases of lFPZ reflects the nucleation of microcracks and the accumulation of distributed damage; while the subsequent decrease in lFPZ marks the propagation of the main crack and the onset of strain localization-induced instability. When the FPZ rear starts to move upwards, the fully developed FPZ is obtained.

-

(5)

As T increases, the maximum lFPZ gradually increases, indicating that the heat-treated process can lead to an increase in the nonlinearity of limestone. Conversely, as T increases, the change in the fully developed FPZ width is small, indicating that the heat-treated process has a slight influence on the size of mineral particles.

Limitations and future research problems

This study has several limitations that warrant discussion:

-

(1)

The conclusions were drawn based on limestone, which may limit the generalizability to rocks with different lithologies (e.g., sandstone, granite).

-

(2)

While the fracture properties were investigated using specimens of a single dimension that complied with ASTM recommendations, the scale effects on fracture characteristics were not systematically evaluated.

-

(3)

Although the DIC technique enabled non-contact full-field displacement measurements, its spatial resolution was constrained by camera pixel density and ambient lighting conditions, potentially introducing measurement uncertainties in microscale crack localization.

Future research should address these limitations through the following approaches:

-

(1)

Expand the material database to include diverse rock types for developing universal fracture criteria.

-

(2)

Conduct multi-scale experimental campaigns that integrate macroscopic mechanical testing with microscopic observations (e.g., scanning electron microscopy) to elucidate the coupling mechanisms between thermal damage evolution and mineral grain interactions.

-

(3)

Develop hybrid monitoring systems by combining DIC with complementary techniques such as acoustic emission or infrared thermal imaging to enhance crack propagation tracking capabilities at multiple scales.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- H :

-

Height of specimen

- L :

-

Length of specimen

- B :

-

Width of specimen

- S :

-

Span of specimen

- a 0 :

-

Initial crack length

- T :

-

Heat-treated temperature

- P :

-

Applied load

- P max :

-

Peak load

- δ :

-

Mid-span deflection

- σ n :

-

Normal stress considering the influence of the crack

- σ N :

-

Normal stress without considering the influence of the crack

- t :

-

Loading time

- l FPZ :

-

Length of FPZ

- w FPZ :

-

Width of FPZ

- l mFPZ :

-

Length of the fully developed FPZ

- w mFPZ :

-

Width of the fully developed FPZ

- α 0 :

-

Crack to height ratio

- A P−CMOD :

-

Area under the P-CMOD curve

- CMODc :

-

Critical CMOD

- δ c :

-

Critical mid-span deflection

- CTODc :

-

Critical CTOD

- d max :

-

Maximum particle size

- Δw :

-

Horizontal displacement jumpz

- w s :

-

Characteristic opening displacement

- FPZ:

-

Fracture process zone

- DIC:

-

Digital image correlation

- ML:

-

Monotonic loading

- CL:

-

Cyclic loading

- CMOD :

-

Crack mouth opening displacement

- CTOD:

-

Crack tip opening displacement

- SCZ:

-

Strain concentration zone

References

Zhou, L., Zhu, Z., Dong, Y. & Niu, C. Investigation of dynamic fracture properties of multi-crack tunnel samples under impact loads. Theor. Appl. Fract. Mec. 109, 102733 (2020).

Suo, Y., Zhao, Y-J., Fu, X-F., He, W-Y. & Pan, Z-J. Study on fracture propagation behavior of deep high-temperature shale gas based on the modified MERR criterion. Theor. Appl. Fract. Mec. 131, 104352 (2024).

Ren, L. et al. Characterization of anisotropic fracture properties of silurian longmaxi shale. Rock. Mech. Rock. Eng. 54, 665–678 (2021).

Li, Y. et al. Experimental study on fracture properties of heat-treated granite in I-II mixed mode suffered from water and liquid nitrogen cooling methods. Eng. Fract. Mech. 311, 110570 (2024).

Zhou, W. et al. Managing induced seismicity risks from enhanced geothermal systems: A good practice guideline. Reviews Geophysics ;62(4): (2024). e2024RG000849.

Suo, Y. et al. The investigation of impact of temperature on mixed-mode fracture toughness of shale by semi-circular Bend test. JOURNAL PETROLEUM Sci. ENGINEERING ;217. (2022).

Yuan, S., Sun, Q., Li, P., Geng, J. & Zhang, H. Fracture properties and dynamic failure of three-point bending of yellow sandstone after subjected to high-temperature conditions. Eng. Fract. Mech. 265, 108366 (2022).

Tang, T., Shi, X., Zhu, X. & Li, L. Experimental study on the effect of bedding on the fracture process zone of shale. Energies 15 (17), 6359 (2022).

Li, C. et al. Anisotropic fracture evolution and size effect of the fracture process zone in laminated shales derived from digital image correlation. Rock Mech. Rock. Eng : 1–22. (2024).

Fu, S., Li, H. & Li, X. Research on the range of fracture process zone of granite based on DIC and acoustic emission. Chin. J. Rock. Mech. Eng. 41 (12), 2497–2508 (2022).

Shen, J., Chen, H., Lu, Z., Zeng, G. & Tang, Y. Research progress in fracture mechanics of graphite for nuclear engineering. Chin. J. Appl. Mech. 40 (06), 1213–1238 (2023).

Wang, X. in Fracture Mechanics Characteristics of Granite after Natural Cooling at High Temperature. (eds Wang, X.) (north university of china, 2019).

Lv, Q. Study on Fracture Characteristics of Lu Gray Granite after High Temperature Water Cooling (north university of china, 2019).

Miao, S., Pan, P. Z., Yu, P., Zhao, S. & Shao, C. Fracture analysis of Beishan granite after high-temperature treatment using digital image correlation. Eng. Fract. Mech. 225 (1–2), 106847 (2019).

Yang, S. Study on Microstructure Evolution and Mechanical Response of Oil Shale Under Real time High Temperature (taiyuan university of technology, 2021).

Fan, B., Qiao, Y. & Hu, S. An experimental investigation on FPZ evolution of concrete at different low temperatures by means of 3D-DIC. Theor. Appl. Fract. Mec. 108, 102575 (2020).

Huang, X., Chen, H., Liu, Y., Xiao, J. & Wang, Q. Study on and comparative analysis of concrete fracture properties using ESPI and DIC technologies. Chin. J. Appl. Mech. 35 (05), 1131–1138 (2018).

Tang, Y., Okubo, S., Xu, J. & Peng, S. Experimental study on damage behavior of rock in Compression–Tension cycle test using 3D digital image correlation. Rock Mech. Rock. Eng (2018).

Ji, W., Pan, P., Miao, S., Su, F. & Du, M. Fracture characteristics of two types of rocks based on digital image correlatio. Rock. Soil. Mech. 37 (8), 7 (2016).

Dong, W., Wu, Z., Zhou, X., Wang, N. & Kastiukas, G. An experimental study on crack propagation at rock-concrete interface using digital image correlation technique. Eng. Fract. Mech. 171, 50–63 (2017).

Yao, J., Dong, W. & Zhong, H. Rate-dependency of tensile fracture properties of rock-concrete interface. Eng. Mech. 39 (12), 108–119 (2022).

Pan, B., Xie, H. & Wang, Z. Equivalence of digital image correlation criteria for pattern matching. Appl. Opt. 49 (28), 5501–5509 (2010).

Liu, D., Chen, H. & Su, R. K. L. Effects of heat-treatment on physical and mechanical properties of limestone. Constr. Build. Mater. 411, 134183 (2024).

ChengDong, L. et al. Geochemical characteristics of calcite and dolomite in sandstone of Dongying sinking, Shandong province, China. Procedia Earth Planet. Sci. 7, 504–507 (2013).

Zhang, W. L. & Chao Effects of mineral content on limestone properties with exposure to different temperatures. Journal Petroleum Sci. & Engineering ;188. (2020).

Wei, M. D., Dai, F., Liu, Y., Xu, N. W. & Zhao, T. An experimental and theoretical comparison of CCNBD and CCNSCB specimens for determining mode I fracture toughness of rocks. Fatigue Fract. Eng. M. 41 (5), 1002–1018 (2018).

Kuruppu, M. D., Obara, Y., Ayatollahi, M. R., Chong, K. & Funatsu, T. ISRM-suggested method for determining the mode I static fracture toughness using semi-circular Bend specimen. Rock. Mech. Rock. Eng. 47, 267–274 (2014).

Fowell, R., Hudson, J., Xu, C., Chen, J. & Zhao, X. in Suggested Method for Determining Mode I Fracture Toughness Using Cracked Chevron Notched Brazilian Disc (CCNBD) Specimens. (eds Fowell, R., Hudson, J., Xu, C., Chen, J. & Zhao, X.) (Elsevier, 2007).

Ayatollahi, M., Bahrami, B., Mirzaei, A. & Yahya, M. Y. Effects of support friction on mode I stress intensity factor and fracture toughness in SENB testing. Theor. Appl. Fract. Mec. 103, 102288 (2019).

Inernational, A. Standard test methods for plane-strain fracture toughness and strain energy release rate of plastic materials. ASTM D 5045–5099. (2007).

Liu, D., Chen, H., Su, R. K. L., Chen, L. & Liang, K. Influence of initial crack length on fracture properties of limestone using DIC technique. Constr. Build. Mater. 403, 133020 (2023).

Yin, T., Wu, Y., Li, Q., Wang, C. & Wu, B. Determination of double-K fracture toughness parameters of thermally treated granite using Notched semi-circular bending specimen. Eng. Fract. Mech. 226, 106865 (2020).

Sun, X., Wan, L. & Jiang, X. Effective categorization of joints by K-means and cluster analysis its verification by fisher distribution. Rock Soil. Mech ;29. (2008).

Pan, B., Qian, K., Xie, H., Asundi, A. & TOPICAL, R. E. V. I. E. W. Two-dimensional digital image correlation for in-plane displacement and strain measurement: a review. Meas. Sci. Technol. -MEAS SCI. TECHNOL. 20, 062001 (2009).

Dutler, N., Nejati, M., Valley, B., Amann, F. & Molinari, G. On the link between fracture toughness, tensile strength, and fracture process zone in anisotropic rocks. Eng. Fract. Mech. 201, 56–79 (2018).

Chen, H. & Liu, D. Fracture process zone of high-strength concrete under monotonic and Cyclic loading. Eng Fract. Mech (2023).

Tang, Y. & Chen, H. Characterizations on fracture process zone of plain concrete. J. Civil Eng. Manage. 25 (8), 819–830 (2019).

Feng, Y., Su, H., Yu, L., Wu, C. & Wang, H. Mixed mode I-II fracture mechanism of sandstone samples after thermal treatment: insights from optical monitoring and thermal analysis. Theor. Appl. Fract. Mec. 125, 103883 (2023).

Baant, Z. P. & Oh, B. H. Crack band theory for fracture of concrete. Mater. Struct. 16 (3), 155–177 (1983).

Zhou, H. M. Mesoscale modelling of size effect on the evolution of fracture process zone in concrete. Eng Fract. Mech ;245(1). (2021).

Skarżyński, Ł., Syroka, E. & Tejchman, J. Measurements and calculations of the width of the fracture process zones on the surface of Notched concrete beams. Strain 47 (s1), e319–e332 (2009).

Acknowledgements

The work described in this paper is supported by the Innovation Exploration and Academic New Talent Program at Guizhou University of Finance and Economics (2024XSXMB05), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 52278251), Natural Science Foundation project of Guizhou Province (Qiankehe MS[2025] 048) and Guizhou Province Academician Innovation Team Workstation for Disaster Remote Sensing Prevention and Control (Qiankehe Platform KXJZ [2024] 006).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Dengkai Liu: Investigation, Validation, Formal analysis, Visualization, Writing - Original Draft, Funding acquisition Hongniao Chen: Conceptualization, Supervision, Funding acquisition, Writing - Review & Editing Yu Guo: Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing - Review & Editing, Funding acquisition Junying Rao: Supervision, Writing - Review & Editing Jinlin Liu: Supervision, Writing - Review & Editing Yinxiang Wang: Investigation, Writing - Review & Editing.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, D., Chen, H., Guo, Y. et al. Effects of loading modes and temperature on fracture properties of limestone. Sci Rep 15, 27697 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-12988-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-12988-3