Abstract

Infectious bone defect is a condition where infection and bone defect occur simultaneously. The simultaneous achievement of effective antimicrobial management and enhanced bone regeneration continues to present a major hurdle in musculoskeletal therapeutics. To address these limitations, we have developed a novel osteoconductive material, this material (PDA@Mg-MOF-LEV) consists of Magnesium-based metal-organic frameworks (Mg-MOF) particles loaded with the antibiotic levofloxacin (LEV) and coated with polydopamine (PDA), which integrates photothermal therapy with antibiotic delivery to combat bacterial drug resistance and facilitate bone tissue regeneration. Under near-infrared (NIR) irradiation, PDA@Mg-MOF-LEV particles demonstrate superior antibacterial efficacy and enhanced osteogenic potential. Drug release studies indicate that NIR irradiation significantly increases LEV release by 337% and Mg ions release by 196% compared to standard conditions. Furthermore, in vitro antibacterial assays confirm that NIR irradiation markedly enhances the antibacterial activity of PDA@Mg-MOF-LEV particles, achieving inhibition rates of 97.5 ± 1.45% against Escherichia coli (E. coli) and 98.5 ± 2.27% against Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus). The photothermal therapy mediated by NIR irradiation not only enhances antibacterial efficacy but also directly stimulates osteogenic differentiation and calcium deposition in mBMSCs, positioning PDA@Mg-MOF-LEV as a multi-modal therapeutic platform for infective osteogenesis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In the realm of orthopedic medicine, the management of extensive osseous defects precipitated by infections remains a formidable clinical challenge1,2,3. The employment of osteoconductive materials for repairing these defects represents an emerging therapeutic strategy4,5. However, the majority of conventional bone repair materials are deficient in antimicrobial properties, making them prone to bacterial colonization post-implantation. Furthermore, many of these materials are biologically inert, exhibiting limited osteoinductive potential, which hampers the restoration and regeneration of infected bone defects6,7. Due to poor blood supply in bone defect regions, systemic antibiotics rarely reach the bactericidal level required at the infection site. To prevent postoperative infection, doctors often administer high - dose antibiotics8. But this risks severe toxicity and upsurges in antibiotic resistance. So, developing bone repair materials that can eliminate bacteria, control infection, and facilitate bone regeneration is critically important for infected bone defect treatment9,10.

The advancement of material science has led to the emergence of various materials, including MXene, carbon dots, metal oxides, and metal-organic frameworks (MOF), in the treatment and repair of bone infections11,12. MOF constitute a family of crystalline porous materials with tunable periodic dimensional architectures (1D-3D), formed through coordination between metal clusters and polydentate organic linkers. Their structural merits—including unsaturated metal sites, programmable porosity, and exceptional surface areas—endow enhanced drug-loading capacity and controlled release kinetics for antimicrobials in osseous environments13. Particularly, Magnesium-based metal-organic frameworks (Mg-MOF) particles emerge as emerging bioceramic carriers, demonstrating dual therapeutic superiority: (i) excellent biocompatibility, and (ii) Mg ions-mediated upregulation of osteogenic gene expression (e.g., RUNX2, OCN) critical for infected bone regeneration.

At the site of bone infection, the presence of bacterial biofilms makes bacteria more tolerant to antibiotics, disinfectants, and the host immune system. This weakens the effect of drug - laden particles and makes treatment more complex and challenging14. Photothermal therapy (PTT), as an innovative antimicrobial modality, offers the benefits of ease of clinical application, strong controllability, and non-invasiveness15[,16. PTT operates on the principle of physical antimicrobial action, utilizing near-infrared (NIR) light to excite photothermal materials, converting light energy into heat energy that elevates local temperatures17. This process leads to protein denaturation, intracellular protein leakage, and ultimately, the thermal ablation of cancer cells or bacterial demise. Importantly, this heating mechanism is effective against both planktonic bacteria and biofilms, inactivating microorganisms without the concern for drug resistance18. The development of Mg-MOF drug-laden particles with photothermal properties is expected to tackle the two problems of bacterial drug resistance and bone tissue regeneration in infected bone defects.

In this study, the synthesis of the Mg-MOF particles was performed by the antibiotic levofloxacin (LEV), and polydopamine (PDA) coating applied to the Mg-MOF-LEV particles to obtain the PDA@Mg-MOF-LEV particles (Fig. 1A). NIR irradiation of PDA@Mg-MOF-LEV particles not only accelerated LEV release but also generated heat that disrupted surrounding bacterial biofilms, enhancing the bactericidal effect of antibiotics. Additionally, the thermal effect increased the release rate of magnesium ions, further augmenting the osteogenic differentiation and mineralization of mouse bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells (mBMSCs) induced by PDA@Mg-MOF-LEV particles (Fig. 1B). The study’s findings underscore the promising antimicrobial and osteoanabolic effects of PDA@Mg-MOF-LEV particles, highlighting their potential in the repair of infected bone defects.

Materials and methods

Materials

Magnesium chloride hexahydrate (MgCl2•6H2O, 99%), gallic acid (99%), levofloxacin (LEV, 98%), dopamine (DA, 98%), potassium hydroxide (KOH, 99%), and sodium hydroxide were purchased from Shanghai Aladdin Biochemical Technology Co., Ltd., The DAPI/PI staining kit, CCK-8 assay kit, and AM/PI universal immunofluorescence reagent kit were obtained from Wuhan Yakein Biotechnology Co., Ltd. DMEM was sourced from Beijing Sofibio Technology Co., Ltd., while fetal bovine serum was acquired from American Trade Biological Technology Co., Ltd. Mouse bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells (mBMSCs) purchased from Wuhan Pronosel Life Science & Technology Co., Ltd. All the chemicals are ready to use without further purification.

Preparation of PDA@Mg-MOF-LEV particles

Firstly, 2 g of MgCl₂•6 H₂O and 7.6 g of gallic acid were mixed in a beaker containing 100 mL of deionized water, and stirred magnetically (300 rpm for 30 min at 20 °C). Then, an aqueous KOH solution (10 M) was added until the pH reached 10, as monitored by a pH meter. The mixture was transferred to a hydrothermal synthesis reactor and heated at 120 °C for 24 h. After cooling to room temperature, light-gray Mg-MOF particles were obtained via ultrahigh-speed centrifugation (10,000 rpm for 10 min at 20 °C). These particles were washed three times with deionized water and dried at 60 °C[ 19[,20.

Next, the pellets were immersed in an aqueous LEV solution (10 mg/mL) and stirred magnetically for six hours before high-speed centrifugation (10,000 rpm for 10 min at 20 °C). The supernatant was collected to measure absorbance at 294 nm using a microplate reader; drug loading capacity was calculated as previously described. The Mg-MOF-LEV particles were washed three times with deionized water and lyophilized overnight.

To prepare PDA@Mg-MOF-LEV particles, we combined 500 mg each of DA and Mg-MOF-LEV particles in 100 mL of deionized water while stirring magnetically for one hour. NaOH was added to adjust the pH to approximately ten before stirring continued for another twenty-four hours. The resulting precipitate was collected via high-speed centrifugation (10,000 rpm for 10 min at 20 °C), rinsed three times with deionized water and ethanol respectively, followed by freeze-drying to yield PDA@Mg-MOF-LEV particles.

Structural and morphological characterization of sample particles

The surface morphology and structure of Mg-MOF, Mg-MOF-LEV, and PDA@Mg-MOF-LEV samples were analyzed using scanning electron microscopy (SEM). X-ray diffraction (XRD) and Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy were employed to characterize the chemical composition of LEV, Mg-MOF, Mg-MOF-LEV, DA, and PDA@Mg-MOF-LEV. The nitrogen adsorption-desorption isotherms of Mg-MOF and Mg-MOF-LEV were measured with a porosity analyzer, enabling calculation of specific surface area via the BET method and pore size distribution via the BJH method.

Evaluation of photothermal properties of PDA@Mg-MOF-LEV particles

PDA@Mg-MOF-LEV particles were immersed in phosphate buffered saline (PBS, pH7.4), then irradiated with an NIR laser source (808 nm, 2.0 W cm−2) for 10 min while temperature values were recorded every 30 s. The photothermal cycling tests were performed to evaluate the stability of the composite scaffolds, and the photothermal images were captured using infrared thermography.

Mg ions and LEV release assay of PDA@Mg-MOF-LEV particles cumulative release assay of Mg ions and LEV

Place 100 mg of PDA@Mg-MOF-LEV particles in 10 mL of PBS (pH 7.4) and let the solution sit undisturbed at room temperature for 84 h. During this period, centrifuge the solution every 12 h (2500 rpm, 5 min), collect 10 mL of the supernatant, and then add 10 mL of fresh PBS to continue the soaking process. Repeat this until the experiment ends. Measure the LEV release in the collected supernatant using HPLC and determine the Mg ion concentration using ICP.

Photothermal intervention release detection of Mg ions and LEV

Weigh 100 mg of PDA@Mg-MOF-LEV particles and immerse them in 10 mL of PBS (pH 7.4). Continuously stir the solution at room temperature at 100 rpm. For the PDA@Mg-MOF-LEV + NIR group, start NIR (808 nm, 2.0 W cm−2) laser irradiation at the 10-minute mark. During the experiment, centrifuge the soaking solution every 10 min (2500 rpm, 5 min), then remove 1 mL of the supernatant and add 1 mL of fresh PBS to the beaker to maintain a constant solution volume. Repeat this until the experiment ends. Use HPLC to measure the LEV release in the collected supernatants and ICP to determine the Mg ion concentration.

In vitro antibacterial experiments

Experimental bacterial selection and setup of experimental groups

Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus), a typical Gram-positive bacterium, and Escherichia coli (E. coli), a representative Gram-negative bacterium, were selected as model organisms in this study to evaluate the antibacterial activity of certain particles. The experimental design comprised five groups: Control, Mg-MOF, Mg-MOF-LEV, PDA@Mg-MOF-LEV, and PDA@Mg-MOF-LEV + NIR.

Bacterial Staining with DAPI/PI

In the initial stage of the experiment, all group samples were subjected to a rigorous disinfection process. This procedure consisted of two main steps. First, the samples were immersed in 75% ethanol for a duration of 30 min. This was followed by exposure to ultraviolet (UV) irradiation for an additional 30 min. Following disinfection, 20 mg of the sterilized samples were carefully introduced into 2 mL of bacterial suspension containing either S. aureus or E. coli at a concentration of 1 × 10^8 CFU/mL. The samples were then co-cultured with the bacteria for a period of 12 h under appropriate conditions to allow for interaction between the samples and the bacteria. The Control group was co-cultured with a PBS solution and bacterial suspension, while the PDA@Mg-MOF-LEV + NIR group was subjected to NIR (808 nm, 2.0 W cm−2) laser irradiation for 10 min. Post co-culture, samples were centrifuged to isolate bacteria, which were then diluted. A staining solution (0.1 µL PI, 0.1 µL DAPI, and 100 µL detection buffer) was added to 1 mL of the bacterial solution and incubated for 30 min in the dark. After centrifugation to remove the staining solution, bacteria were washed three times with PBS. The stained bacteria were then transferred to a glass slide for observation under an inverted fluorescence microscope (CKX53, Olympus).

Colony count analysis

Following sterilization, 20 mg of samples were added to 2 mL of S. aureus or E. coli suspension (1 × 10^8 CFU/mL) for a 12-hour co-culture. The Control group was co-cultured with PBS and bacterial suspension, and the PDA@Mg-MOF-LEV + NIR group received NIR (808 nm, 2.0 W cm−2) laser irradiation for 10 min. After centrifugation, the supernatant was removed and 1 mL of PBS was diluted, subsequently the dilution solution was applied evenly in the culture plate and the colony number was observed after 12 h incubation in the bacterial incubator. Plate colony photos were collected with a camera to collect data and record the number of colonies. Finally, we calculated the antibacterial rate according to the following formula (Eq. 1):

where CFU Control was represents the number of viable bacteria in the control group. This serves as the baseline for comparison, CFU Experimental: was represents the number of viable bacteria remaining after treatment with the different groups.

Crystal Violet staining for biofilm assessment

Crystal violet staining was employed to evaluate the particles’ ability to inhibit biofilm formation. Sterilized samples (20 mg) were added to 96-well plates, followed by 100 µL of either S. aureus or E. coli suspension (1 × 108 CFU/mL) for a 24-hour co-culture. The Control group was co-cultured with PBS and bacterial suspension, and the PDA@Mg-MOF-LEV + NIR group was irradiated with a NIR (808 nm, 2.0 W cm−2) laser for 10 min. After staining with crystal violet for 60 min in the dark, the biofilm’s staining was observed under a microscope, and the samples’ destructive effect on the biofilm was assessed. For quantitative analysis of biofilm staining, the stained biofilms of each group samples were washed into centrifuge tubes using glacial acetic acid, and then the absorbance of the wash solution at 570 nm was subsequently collected using a microplate reader.

In vitro cell experiments

Preparation of cell culture medium and Osteogenic induction solution

In this experiment, mBMSCs were selected as the experimental cell type for this study. And the cell culture medium was composed of 10% premium-grade fetal bovine serum, 89% high-glucose DMEM, and 1% penicillin-streptomycin (PS). For the alkaline phosphatase (ALP) and alizarin red s (ARS) experiments, an osteogenic induction solution was utilized. This solution included ascorbic acid, β-glycerophosphate, and dexamethasone at concentrations of 50 µg/mL, 10 mM, and 10 nM respectively.

Preparation of particle extracts

Five experimental groups were established: control, Mg-MOF, Mg-MOF-LEV, PDA@Mg-MOF-LEV, and PDA@Mg-MOF-LEV + NIR. The preparation of the Mg-MOF extract is as follows: After sterilization, 200 mg of Mg-MOF was soaked in a centrifuge tube containing 10 mL of cell culture medium and then transferred to a cell culture incubator for 24 h of undisturbed incubation. After the incubation, the centrifuge tube was centrifuged at 1500 rpm for 5 min, and the supernatant, used as the particulate extract, was collected for subsequent cell culture. The pellet extraction procedures for the Mg-MOF-LEV and PDA@Mg-MOF-LEV groups were identical to that of the Mg-MOF group. For the control group, we only took 10 mL of cell culture medium (composed of 10% premium fetal bovine serum, 89% high - glucose DMEM, and 1% penicillin - streptomycin), placed it in a cell incubator, and let it sit undisturbed for 24 h without any additional treatment or interference. After 24 h, the culture medium was directly collected and used for the cell culture of the control group. In the preparation of extracts for the PDA@Mg-MOF-LEV + NIR group, particles were subjected to NIR (808 nm, 2.0 W cm−2) intervention for ten minutes during their preparation; all other steps followed the protocol used for obtaining extracts from the Mg-MOF group.

Biocompatibility test

First, each well of a 96 - well cell culture plate was filled with 150 µL of cell suspension at 10,000 cells/mL. After a 24-hour incubation period, the culture medium was replaced with fresh pellet extraction solution to continue the cultivation process. Then, at 24 - and 72 - hour intervals, cells were stained with a live/dead assay kit and observed under a fluorescence microscope to evaluate morphology, with green and red fluorescence indicating live and dead cells respectively.

Cell proliferation analysis

Each well of a 96 - well cell culture plate was filled with 150 µL of cell suspension (10,000 cells/mL). After 24 h of initial culture, the medium was replaced with fresh particulate extract to support further cell growth. To assess cell proliferation at 24–72 h post - treatment, a CCK − 8 assay was used. The steps were as follows: 10% CCK − 8 solution was added to the culture medium, followed by a 1 - hour reaction. The reaction mixture was then transferred into an automatic enzyme labeling instrument for measurement reader for measurement; absorbance (OD) values were recorded at a wavelength of 450 nm.

ALP and ARS staining

Each well of a 6 - well cell culture plate was filled with 3 mL of cell suspension (10,000 cells/mL). After 24 - hour incubation for cell attachment, the medium was replaced with fresh particulate extract and osteogenic induction solution to continue cell culture. Following 14 days of incubation, the medium was aspirated from the wells, and a fixation solution was added to each well for 30 min to fix the cells. Post-fixation, the cells were rinsed with PBS solution (pH 7.4) to remove the fixative. Next, 500 µL of either Alizarin Red S (ARS) or Alkaline Phosphatase (ALP) staining solution was applied to the wells for a staining period of 60 min. Finally, after the staining procedure, the staining solution was aspirated, and any residual dye was washed away using PBS solution (pH 7.4). The results from the ARS and ALP staining were then observed under a microscope. And the experimental results of each group were subjected to data extraction and analysis using ImageJ Version 1.54.

Immunofluorescence staining

In a 24 - well cell culture plate, 1 mL of cell suspension (10,000 cells/mL) was added and incubated for 24 h. After 24 h, the initial culture medium was replaced with particulate extract from each group, and cultured for another day. On day 3, the particulate extract was removed from the 24 - well plate, and immunofluorescence staining was carried out. Cells were fixed, permeabilized, and blocked, then incubated with primary and secondary antibodies in turn. Finally, antibody fluorescence was detected with a fluorescence microscope to analyze the location and expression level of the target protein. And the experimental results of each group were subjected to data extraction and analysis using ImageJ Version 1.54. For detailed procedures, please refer to this article21.

qRT-PCR

In addition to the aforementioned experiments, this study employed quantitative real-time PCR technology to assess the expression of osteogenesis-related genes in mBMSCs. At the start, mBMSCs were cultured for 7 days under identical conditions. Then, mRNA was extracted from cells using column - purification. Subsequently, the extracted mRNA was converted into cDNA using the TakaraBrisript First - Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit. This study used a SYBR Green kit for qRT - PCR detection and the 2 - ΔΔCt method to measure the relative expression of mRNA.

Statistical analysis

In this experiment, we used a statistically standard expression for all the collected quantitative data, namely that each set of data was presented in the form of mean ± standard deviation (mean ± SD). To ensure the reliability of our findings, each in vitro study was conducted with three replicate groups, with each group being tested three times. The statistical analysis of the data was performed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with the aid of SPSS software, version 25.0. The significance of differences in the numerical data was set at a threshold of p < 0.05.

Results and discussion

SEM analysis

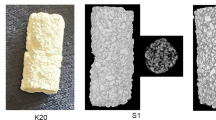

Mg-MOF has garnered significant attention due to its high specific surface area, substantial porosity, and tunable chemical functionality. Owing to its unique coordination characteristics, Mg-MOF particles belonging to the hexagonal crystal system readily adopt various morphologies during synthesis, including stalk-like, spindle-like, shell-like, and square shapes22. The synthesized sample particles’ microstructure was analyzed via SEM. As shown in Fig. 2A-C, the Mg-MOF particles mainly display a stalk-like morphology, consistent with prior researchers’ descriptions23. Furthermore, the morphology of Mg-MOF-LEV particles is largely consistent with that of Mg-MOF particles, indicating that the incorporation of LEV does not compromise the structural integrity of Mg-MOF. In contrast, PDA@Mg-MOF-LEV particles manifest as tightly clustered aggregates where PDA effectively consolidates numerous individual particles.

(A) SEM images of Mg-MOF particle. (B) SEM images of Mg-MOF-LEV particle. (C) SEM images of PDA@Mg-MOF-LEV particle. (D) XRD pattern of Mg-MOF, Mg-MOF-LEV and PDA@Mg-MOF-LEV particles. (E) FTIR spectra of LEV, Mg-MOF, Mg-MOF-LEV and PDA@Mg-MOF-LEV particles. (F) N2 adsorption-desorption isotherms of Mg-MOF and Mg-MOF-LEV particles.

XRD analysis

To gain deeper insights into the chemical composition of the synthesized sample particles, XRD analyses were performed on each sample group. As shown in Fig. 2D, the XRD pattern of Mg-MOF has sharp diffraction peaks at 2θ of 11.8° and 18.1°, attributed to the (300) and (510) crystal planes24,25. These peaks are in agreement with previously reported data. Additionally, LEV exhibits sharp characteristic peaks at 2θ values of 6.5°, 9.7°, 13.1°, 15.7°, 19.3°, 19.9°, and 26.6°, confirming its crystalline nature26. However, it is noteworthy that the diffraction peak associated with LEV is present in the XRD pattern of Mg-MOF-LEV samples. This could be attributed to LEV being encapsulated within the Mg-MOF framework or its relatively low concentration. Furthermore, the LEV-related diffraction peaks are undetectable in the XRD spectra of the PDA@Mg-MOF-LEV particles. This alteration is likely a result of the coating effect of PDA on Mg-MOF-LEV. Moreover, the XRD spectra of PDA did not show any obvious characteristic peaks, completely without the intensity of the diffraction peaks associated with LEV in the XRD spectra of the PDA@Mg-MOF-LEV sample. This change may be a result of the coating effect of PDA on Mg-MOF-LEV.

FTIR analysis

In this study, FTIR was employed to investigate component interactions within PDA@Mg-MOF-LEV particles. As shown in Fig. 2E, the levofloxacin spectrum reveals characteristic peaks indicative of C-F stretching vibrations at 1250 cm⁻¹, C = O stretching vibrations at 1620 cm⁻¹, and O-H stretching vibrations at 3433 cm⁻¹. The spectrum for Mg-MOF indicates an observable peak related to Mg-O vibrations at 581 cm⁻¹26. In contrast, within MG-MOF-LEV particle spectra there is a shift in this vibration from 581 cm⁻¹ to 592 cm⁻¹, alongside confirmation of levofloxacin’s C = O stretching vibration appearing at approximately 1620 cm⁻¹27. This shift in magnesium oxide vibrational frequency coupled with new appearances confirms successful loading of LEV into Mg-MOF-LEV structures. The characteristic peaks of PDA FTIR spectra did not intersect with the Mg-MOF-LEV characteristic peaks, while the spectra obtained in the PDA@Mg-MOF-LEV sample belonging to the Mg-MOF-LEV particles disappeared, a phenomenon may be related to the encapsulation of PDA.

BET analysis

The specific surface area and average pore size of the Mg-MOF particles were 65.487 m²g−1 and 15.18 nm, respectively, which were measured by the BET method (Fig. 2F). The porous structure and large specific surface area are conducive to efficient drug loading28,29. After the LEV loading was completed, the specific surface area and average pore size of the Mg-MOF-LEV particles were 17.647 m²g−1 and 5.01 nm, which showed a significant decrease compared to the Mg-MOF particles, indicating that the LEV drug loading was successful. Based on the decrease in the LEV concentration in the solution, we calculated the drug loading ratio of LEV to be 43.07%.

Photothermal performance analysis

Figure 3A illustrates the schematic representation of NIR laser intervention on PDA@Mg-MOF-LEV particles in this study. Figure 3B presents the thermal imaging results following NIR intervention across all groups. The findings indicate that the photothermal performance of the Control, Mg-MOF, and Mg-MOF-LEV groups is suboptimal, whereas the PDA@Mg-MOF-LEV group demonstrates exceptional photothermal efficacy, achieving a temperature of 50.9 °C after 15 min of NIR irradiation. Additionally, Fig. 3C depicts the temperature rise and cooling curves for PDA@Mg-MOF-LEV particles as observed through thermal imaging. The data reveal that both temperature rise and cooling curves exhibit a progressively smooth trend. Furthermore, an assessment of the photothermal stability of PDA@Mg-MOF-LEV particles was conducted (Fig. 3D). Notably, their temperature rise curve remained stable after four cycles of NIR laser exposure, underscoring their robust photothermal stability.

(A) Schematic diagram of the NIR intervention. (B) The real-time temperature variations of Control, Mg-MOF, Mg-MOF-LEV and PDA@Mg-MOF-LEV groups with NIR intervention for 15 min. (C) The heating up and cooling down irradiation curve of Mg-MOF-LEV particle under 808 nm NIR laser (2.0 W cm−2) irradiation. (D) Cyclic irradiation curve of PDA@Mg-MOF-LEV particle under 808 nm NIR laser (2.0 W cm−2) irradiation for four on/off cycles.

Mg ions and LEV release detection

The average release concentrations of Mg and LEV from PDA@Mg-MOF-LEV particles are illustrated in Fig. 4A-B. Initial experimental results indicated a high release of Mg ions and LEV during the first two days, followed by a gradual stabilization, demonstrating sustained release behavior throughout the testing period. Figure 4C-D show the cumulative release curves for Mg ions and LEV, which gradually flattened. After a 7-day soak, the release amounts reached 1065 µg/mL for Mg ions and 2145 µg/mL for LEV, respectively.

(A-B) The release amount of Mg icons and LEV from the PDA@Mg-MOF-LEV particle at different time points. (C-D) The cumulative release amount of Mg icons and LEV from the PDA@Mg-MOF-LEV particle. (E-F) The release amount of Mg icons and LEV from the PDA@Mg-MOF-LEV particle under 808 nm NIR laser (2.0 W cm−2) irradiation.

The real-time effects of NIR laser irradiation on Mg ions and LEV release are depicted in Fig. 4E-F. Without NIR intervention, the release rates were relatively slow; after 60 min of in vitro soaking, Mg ion concentrations were 30.7 µg/mL, and LEV concentrations were 79.8 µg/mL. In contrast, NIR laser intervention significantly increased these release rates, with Mg ion concentrations reaching 57.7 µg/mL and LEV concentrations reaching 141.5 µg/mL at 60 min. These results suggest that NIR laser control over the release behavior of PDA@Mg-MOF-LEV particles is effective.

Antibacterial activity

S aureus is the main pathogen in bone defect infections30. Levofloxacin, a preferred antibiotic, effectively inhibits or kills this bacterium, curbing infection spread31. In recent years, treatments for bone defects with infection have evolved, featuring surgical, antibiotic, tissue engineering, and biomaterial approaches. Surgery, like debridement and bone resection, removes infected and necrotic tissue32. Antibiotics, especially LEV, are essential in treatment, with selection based on sensitivity tests and long-term use as needed. Tissue engineering and biomaterials, such as antimicrobial peptide hydrogels, offer new treatment options, preventing infection and promoting bone regeneration33. Additionally, research is ongoing into treatments targeting the biofilm formed by S. aureus during infections, including biofilm-disrupting drugs and materials to boost antibiotic efficacy34. Despite progress, challenges like persistent infections, biofilm formation, and antibiotic resistance remain. Thus, integrating multiple treatments and tailoring solutions to individual patients is crucial for improving treatment outcomes.

To assess the antibacterial effects of PDA@Mg-MOF-LEV particles under NIR irradiation, bacterial colony counts were evaluated using the DAPI staining method and agar diffusion method post-treatment for each group. Figure 5A shows that no dead bacteria were observed in the Control and Mg-MOF groups, indicating no antibacterial effect from Mg-MOF. However, dead bacteria were observed in the Mg-MOF-LEV, PDA@Mg-MOF-LEV, and PDA@Mg-MOF-LEV + NIR groups, with the highest number in the PDA@Mg-MOF-LEV + NIR group.

As shown in Fig. 6A, the number of bacterial colonies on the agar plate for the Mg-MOF group was similar to the Control group, showing no antibacterial effects. However, the Mg-MOF-LEV and PDA@Mg-MOF-LEV groups showed significantly fewer bacterial colonies than the Mg-MOF group, though some colonies remained. In contrast, the PDA@Mg-MOF-LEV + NIR group showed almost no bacterial colonies, indicating a significant antibacterial effect. Figure 6B reveals that for both E. coli and S. aureus, the antibacterial rate of the Mg-MOF group did not exceed 5%. The antibacterial rates in the Mg-MOF-LEV and PDA@Mg-MOF-LEV groups, containing LEV, were significantly enhanced to approximately 85%, due to LEV’s potent antibacterial properties. The PDA@Mg-MOF-LEV + NIR group’s antibacterial rate further increased to 98.5 ± 2.27% for S. aureus and 97.5 ± 1.45% for E. coli, indicating a synergistic lethal effect between LEV and the photothermal action of NIR irradiation on bacteria.

The synergistic antibacterial action of LEV and the photothermal effect exhibited by PDA@Mg-MOF-LEV particles might be attributed to the fact that under the induction of NIR laser, PDA generates a local high-temperature effect that disrupts the integrity of the bacterial biofilm and disturbs the physiological functions of biological macromolecules, thereby causing bacterial death. More importantly, as the biofilm is a major contributing factor for bacterial drug resistance, disrupting its integrity has an enhancing effect on the antibacterial efficacy of antibiotics. Therefore, we investigated the disruptive effect of PDA@Mg-MOF-LEV particles + NIR intervention on bacterial biofilms. As shown in Fig. 6C-D, the crystal violet staining results revealed that the Control and Mg-MOF groups maintained a clear and intact biofilm structure, with the dense biofilm remaining undamaged. The biofilms in the Mg-MOF-LEV and PDA@Mg-MOF-LEV groups were also hardly disrupted, presenting a relatively intact structure. Nevertheless, after 10 min of near-infrared light irradiation, it could be observed that the biofilms of both S. aureus and E. coli in the PDA@Mg-MOF-LEV + NIR group were significantly disrupted, resulting in a considerable loss of biomass. Thus, photothermal therapy demonstrates excellent functionality in eliminating bacterial biofilms.

Cell viability of mBMSCs

The biocompatibility of bone repair materials is highly necessary for evaluating their further therapeutic applications in the clinical setting. In this experiment, we cultivated mBMSCs with the extractive liquids of particles prepared under different conditions and utilized live/dead fluorescence staining to assess the cytocompatibility of each group of particles (Fig. 7A). On the 3 days of cultivation, each group of cells exhibited a favorable growth morphology, with almost no dead cells being identified, suggesting that all groups demonstrated excellent biocompatibility. Moreover, compared with the Control group, the quantity of mBMSCs in the remaining groups increased, and the increase was most pronounced in the PDA@Mg-MOF-LEV group.

In vitro osteogenic activity of mBMSCs cultured with extracts from different groups. (A) Live-dead fluorescence assay at 72 h. (B) CCK-8 proliferation test 24 h and 72 h. (C) ALP staining at 7 days. (D) Quantitative analysis of ALP staining results using ImageJ software. (E) ARS staining at 21 days. (F) Quantitative analysis of ARS staining results using ImageJ software. (*p < 0.05).

Additionally, we employed the CCK-8 method to evaluate the impact of each group on the cellular proliferation of mBMSCs. As depicted in Fig. 7B, on the first day, there was no significant disparity in the cellular proliferation trend among all groups. However, as the cell culture period was extended to the third day, in contrast to the Control group, the mBMSCs in the Mg-MOF, Mg-MOF-LEV, and PDA@Mg-MOF-LEV groups all manifested a proliferation trend (p < 0.05). Moreover, under the intervention of NIR, the increase trend in the PDA@Mg-MOF-LEV + NIR group was the most prominent (p < 0.05). The experimental results indicate that the Mg ions released by the PDA@Mg-MOF-LEV + NIR particles possess the ability to promote cellular proliferation. Furthermore, under the intervention of NIR, due to the increased release of Mg ions, the promotion effect on cellular proliferation is further enhanced.

Osteogenic differentiation capacity of mBMSCs

Mg ions have been shown to influence not only the proliferation of BMSCs but also to promote their osteogenic differentiation capacity. The concentration of Mg ions is crucial, as previous research has established a close relationship between Mg ion impact on osteoblasts and their concentration35. High concentrations of Mg ions can be toxic to osteoblasts, affecting bone formation rates and hindering bone tissue regeneration36. The proposed mechanism involves Mg ions, as Ca ion antagonists, competing with Ca ions for channels, disrupting the Ca ion balance across cell membranes, and thus impacting the proliferation, differentiation, and mineralization of human BMSCs37. However, at appropriate concentrations, Mg ions can enhance osteoblast activity and new bone formation38. Additionally, appropriate Mg ion concentrations have been found to promote the expression of osteogenic markers39.

Building on these findings, we investigated the effects of Mg-MOF-LEV particles on the osteogenic differentiation of mBMSCs. ALP staining, a classical method for assessing early osteogenic differentiation, was used to evaluate the impact of bone repair materials on mBMSC osteogenesis40,41,42. Figure 7C-D show that after 7 days, mBMSCs in the Mg-MOF, Mg-MOF-LEV, and PDA@Mg-MOF-LEV groups exhibited higher ALP activity than the Control group (p < 0.05). However, semi-quantitative analysis revealed no significant difference in ALP activity increase among the three groups (p > 0.05). Notably, the PDA@Mg-MOF-LEV + NIR group displayed the strongest ALP activity, with a significant increase compared to the other groups, and this enhancement was statistically significant (p < 0.05).

ARS staining is a commonly employed staining method that is widely utilized in the research of osteoblast differentiation, bone cells, or tissue pathophysiology43,44. By virtue of the chromogenic reaction between alizarin red and extracellular calcium nodules to generate a deep red compound, we can assess the late osteogenic differentiation of cells. As shown in Fig. 7E-F, after culturing mBMSCs with the extractive liquids of each group of particles for 21 days, red calcium deposits emerged in all groups. Notably, compared with the Control group, the red calcium deposits in the Mg-MOF, Mg-MOF-LEV, and PDA@Mg-MOF-LEV groups significantly increased (p < 0.05), indicating that Mg ions can effectively promote the calcification of the cytosol matrix of mBMSCs. Furthermore, the quantity and area of red calcium deposits in the PDA@Mg-MOF-LEV + NIR group were the highest among all experimental groups (p < 0.05), suggesting that the intervention of NIR promotes osteogenic mineralization of cells.

IF is an analytical method that uses antibodies marked with fluorescent labels to detect and localize specific antigens within cells45,46. In this study, we used IF to assess BMP-2 expression in mBMSCs. As shown in Fig. 8A-B, the green fluorescence intensity in the Mg-MOF, Mg-MOF-LEV, and PDA@Mg-MOF-LEV groups was significantly higher compared to the Control group. As depicted in Fig. 8A-B, the green fluorescence intensity and coverage area of the PDA@Mg-MOF-LEV + NIR group were the highest among all groups, with a statistically significant difference (p < 0.05). These results are in line with those of other osteogenic experiments. Collectively, they demonstrate that PDA@Mg-MOF-LEV particles can significantly enhance cellular activity and promote osteogenic differentiation. Moreover, appropriate NIR intervention can further augment this effect.

To assess the impact of different particulate extracts on mBMSC osteogenic differentiation, we analyzed multiple osteogenesis - related genes via qRT-PCR. As shown in Fig. 8C-E, compared with the control group, the expression levels of osteogenesis - related genes (ALP, BMP-2, RUNX2) in the PDA@Mg-MOF-LEV + NIR group were significantly elevated (p < 0.05). These results, consistent with other osteogenic experiments, indicate that PDA@Mg-MOF-LEV particles can markedly enhance mBMSC osteogenic differentiation, and NIR irradiation further strengthens this effect, possibly due to increased expression of key osteogenic genes.

Research focus and future prospects

All in all, PDA@Mg-MOF-LEV particles are promising biomaterials for repairing infectious bone defects with notable clinical potential. PDA, a high-performance photothermal agent, generates local high temperatures under NIR irradiation, triggering controlled LEV release from PDA@Mg-MOF-LEV particles. This dual photothermal-chemical approach not only directly damages bacterial membranes but also enhances LEV penetration and restores antibiotic sensitivity in resistant bacteria, boosting the antibacterial efficacy of PDA@Mg-MOF-LEV particles. Moreover, these particles effectively combat resistant bacterial infections through combined photothermal-drug synergy and biofilm clearance. Their design aligns with current trends in photothermal-chemical combination therapy research and holds significant promise for clinical application.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the authors have successfully developed PDA@Mg-MOF-LEV nanoparticles that exhibit remarkable antibacterial and osteogenic properties for the treatment of infected bone defects. These nanoparticles were synthesized by incorporating LEV into Mg-MOF during its formation and subsequently coating them with a layer of PDA, which imparts both PTT effects and antibiotic functionality. The findings demonstrate that PDA@Mg-MOF-LEV nanoparticles facilitate a sustained release of LEV, exhibiting significant antibacterial activity. Furthermore, under NIR irradiation, the LEV release rate from these nanoparticles is enhanced, while they also display excellent photothermal characteristics. This results in an effective disruption of bacterial biofilms and augments their antibacterial efficacy. Additionally, PDA@Mg-MOF-LEV nanoparticles show favorable cytocompatibility with BMSCs, and NIR irradiation further accelerates magnesium ion release from the particles, thereby enhancing the osteogenic potential.

Data availability

All the data used and/or analyzed in this study can be obtained from the corresponding author upon request.

References

Wang, X. et al. Activated allograft combined with induced membrane technique for the reconstruction of infected segmental bone defects. Sci. Rep. 14, 12587. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-63202-9 (2024).

Yang, X. et al. Management of infected bone defects of the femoral shaft by masquelet technique: sequential internal fixation and nail with plate augmentation. BMC Musculoskelet. DISORDERS. 25, 552. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12891-024-07681-x (2024).

Jiang, X. et al. Antibiotic-loaded bone cement fixation technique combined with bilateral pectoralis major muscle flaps tension-free management for sternal infection after midline sternotomy. J. Cardiothorac. Surg.19, 289. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13019-024-02749-0 (2024).

Hu, X. L. et al. 3D printed multifunctional biomimetic bone scaffold combined with TP-Mg nanoparticles for the infectious bone defects repair. Small 20, 2403681. https://doi.org/10.1002/smll.202403681 (2024).

Xia, D. M. et al. The effect of pore size on cell behavior in mesoporous bioglass scaffolds for bone regeneration. Appl Mater Today. 29, 101607. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmt.2022.101607 (2022).

Wu, Y. T. et al. Photothermal sensitive nanocomposite hydrogel for infectious bone defects. Bone Res.13(1), 22. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41413-024-00377-x (2025).

Huang, L. et al. Advancements in GelMA bioactive hydrogels: Strategies for infection control and bone tissue regeneration. Theranostics15, 460–493. https://doi.org/10.7150/thno.103725 (2025).

Ghaseminejad-Raeini, A. et al. Antibiotic-coated intramedullary nailing managing long bone infected non-unions: a meta-analysis of comparative studies. Antibiotics-Basel 13, https://doi.org/6910.3390/ antibiotics13010069 (2024).

Xiong, W. et al. Cofe2O4 nanoparticles coated with mesoporous silica and loaded with naringin and levofloxacin for repair of infectious bone defects. ACS Appl. Nano Mater.7, 21936–21950 (2024).

Keremu, A. et al. 3D printed PLGA scaffold with nano- hydroxyapatite carrying linezolid for treatment of infected bone defects. Biomed. Pharmacother. 172, 116228. https://doi.org/11622810.1016/ j.biopha.2024.116228 (2024).

Chandra, D. K., Kumar, A. & Mahapatra, C. Ultrasonic synthesis of Ag@CNT-Based metal-organic framework (MOF) for enhanced synergetic antimicrobial activity against. Jom -Us. 76, 5626–5642. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11837-024-06714-z (2024).

Chandra, D. K., Kumar, A. & Mahapatra, C. Smart nano-hybrid metal-organic frameworks: Revolutionizing advancements, applications, and challenges in biomedical therapeutics and diagnostics. Hybrid Adv9, 100406. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hybadv.2025.100406 (2025).

Bigham, A. et al. MOFs and MOF-Based composites as next-generation materials for wound healing and dressings. Small 20 (30), e2311903. https://doi.org/10.1002/smll.202311903 (2024).

Song, T. Y., Duperthuy, M. & Wai, S. N. Sub-optimal treatment of bacterial biofilms. Antibiotics5, 23. https://doi.org/10.3390/Antibiotics5020023 (2016).

Liu, H. et al. Nanomaterials-based photothermal therapies for antibacterial applications. Mater. Des. 233 https://doi.org/10.1016/ j.matdes.2023.112231 (2023).

Liu, D. K. et al. Nano Sim@ZIF8@PDA modified injectable temperature sensitive nanocomposite hydrogel for photothermal/drug therapy for peri-implantitis. Carbohyd Polym. 354, 123327. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.carbpol.2025.123327 (2025).

Naskar, A. & Kim, K. S. Friends against the foe: Synergistic photothermal and photodynamic therapy against bacterial infections. Pharmaceutics15, 1116. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics15041116 (2023).

He, W. et al. Highly efficient photothermal nanoparticles for the rapid eradication of bacterial biofilms. Nanoscale13, 13610–13616. https://doi.org/10.1039/d1nr03471e (2021).

Wang, B. et al. Regulating the release of Mg-MOF from degradable bone cement by coating Mg-MOF with oxidized dextran/gelatin. New J. Chem.47, 18591–18602. https://doi.org/10.1039/d3nj02993j (2023).

Wang, B. et al. Multifunctional magnesium-organic framework doped biodegradable bone cement for antibacterial growth, inflammatory regulation and osteogenic differentiation. J. Mater. Chem. B11, 2872–2885. https://doi.org/10.1039/d2tb02705d (2023).

Xiong, W. et al. Direct osteogenesis and Immunomodulation dual function sustained release of naringin from the polymer scaffold. J Mater Chem B. 11, 10896–10907. https://doi.org/10.1039/d3tb01555f (2023).

Bao, Z. B., Yu, L. A., Ren, Q. L., Lu, X. Y. & Deng, S. G. Adsorption of CO and CH on a magnesium-based metal organic framework. J. Colloid Interf Sci. 353, 549–556. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcis.2010 (2011). 09.065.

Ge, Y. et al. An Mg-MOFs based multifunctional medicine for the treatment of osteoporotic pain. Materials Science and Engineering: C129, 112386. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.msec.2021.112386 (2021).

Xie, S. et al. MOF-74-M (M = Mn, co, ni, zn, mnco, mnni, and MnZn) for low-temperature NH3-SCR and in situ DRIFTS study reaction mechanism. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces12, 48476–48485. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsami.0c11035 (2020).

Hu, J. Q., Chen, Y., Zhang, H. & Chen, Z. X. Controlled syntheses of Mg-MOF-74 nanorods for drug delivery. J. Solid State Chem.294, 121853. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jssc.2020.121853 (2021).

Schnabel, J., Ettlinger, R. & Bunzen, H. Zn-MOF-74 as pH-responsive drug-delivery system of arsenic trioxide. Chemnanomat6, 1229–1236. https://doi.org/10.1002/cnma.202000221 (2020).

Puppi, D., Piras, A. M., Pirosa, A., Sandreschi, S. & Chiellini, F. Levofloxacin-loaded star poly(ε-caprolactone) scaffolds by additive manufacturing. J. Mater. Sci. : Mater. Med.2744. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10856-015-5658-1 (2016).

Feng, Y. F. et al. Antibodies@MOFs: An in vitro protective coating for preparation and storage of biopharmaceuticals. Adv. Mater.31(2), 1805148. https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.201805148 (2019).

Freund, R., Lächelt, U., Gruber, T., Rühle, B. & Wuttke, S. Multifunctional efficiency: Extending the concept of atom economy to functional nanomaterials. ACS Nano12, 2094–2105. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsnano.8b00932 (2018).

bdulrehman, T. et al. Advances in the targeted theragnostics of osteomyelitis caused by. Arch. Microbiol. 206 https://doi.org/28810. 1007/s00203-024-04015-2 (2024).

Senneville, E. et al. Safety of prolonged high-dose Levofloxacin therapy for bone infections. J Chemotherapy. 19, 688–693. https://doi.org/10.1179/joc.2007.19.6.688 (2007).

Jensen, L. K., Hartmann, K. T., Witzmann, F., Asbach, P. & Stewart, P. S. Bone infection evolution. Injury 55, 111826. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.injury.2024.111826 (2024).

Hu, B. H. et al. Supramolecular hydrogels for antimicrobial therapy. Chem. Soc. Rev.47(18), 6917–6929. https://doi.org/10.1039/c8cs00128f (2018).

Ferreira, M. et al. Levofloxacin-loaded bone cement delivery system: highly effective against intracellular bacteria and biofilms. Int J Pharmaceut. 532, 241–248. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpharm.2017.08.089 (2017).

Gu, Y. F. et al. Three-dimensional printed Mg-doped β-TCP bone tissue engineering scaffolds: effects of magnesium ion concentration on osteogenesis and angiogenesis. Tissue Eng. Regen Med. 16, 415–429. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13770-019-00192-0 (2019).

Liang, L. X. et al. Stimulation of and osteogenesis by Ti-Mg alloys with the sustained-release function of magnesium ions. Colloid Surf. B. 197, 111360. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.colsurfb.2020.111360 (2021).

Hung, C., Chaya, A., Liu, K., Verdelis, K. & Sfeir, C. The role of magnesium ions in bone regeneration involves the canonical Wnt signaling pathway. Acta Biomater. 98, 246–255. https://doi.org/10.1016 /j.actbio.2019.06.001 (2019).

Chen, Z., Zhang, W., Wang, M., Backman, L. J. & Chen, J. Effects of zinc, magnesium, and iron ions on bone tissue engineering. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng.8, 2321–2335. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsbiomaterials.2c00368 (2022).

Zhang, X. et al. A novel magnesium ion-incorporating dual- crosslinked hydrogel to improve bone scaffold-mediated osteogenesis and angiogenesis. Materials Science and Engineering: C121, 111868. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.msec.2021.111868 (2021).

Zhao, Y. N. et al. Construction of macroporous magnesium phosphate-based bone cement with sustained drug release. Mater Design. 200, 109466. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matdes.2021.109466 (2021).

Qian, G. W. et al. Enhancing bone scaffold interfacial reinforcement through in situ growth of metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) on strontium carbonate: achieving high strength and osteoimmunomodulation. J Colloid Interf Sci. 655, 43–57. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcis.2023.10.133 (2024).

An, J. et al. Natural products for treatment of osteoporosis: The effects and mechanisms on promoting osteoblast-mediated bone formation. Life Sci.147, 46–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lfs.2016.01.024 (2016).

Li, M. M., Zhao, P. Z., Wang, J. W., Zhang, X. C. & Li, J. Functional antimicrobial peptide-loaded 3D scaffolds for infected bone defect treatment with AI and multidimensional printing. Mater Horiz. 12, 20–36. https://doi.org/10.1039/d4mh01124d (2025).

Liu, Q. et al. Recent advances of Osterix transcription factor in osteoblast differentiation and bone formation. Front. Cell Dev. Biol.8, 601224. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcell.2020.601224 (2020).

Castanheira, E. J. et al. 3D-printed injectable nanocomposite cryogel scaffolds for bone tissue regeneration. Mater Today Nano. 28, 100519. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mtnano.2024.100519 (2024).

Zheng, Y. Y. et al. A programmed surface on polyetheretherketone for sequentially dictating osteoimmunomodulation and bone regeneration to achieve ameliorative osseointegration under osteoporotic conditions. Bioact Mater 14, 364–376. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bioactmat.2022 (2022).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82074183); Natural Science Foundation of Zhejiang Province (No. LZ22H270002); Zhejiang Province Traditional Chinese Medicine Technology Plan Traditional Chinese Medicine Modernization Special Fund (No. 2020ZX009).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Wei Xiong, Yuxiang Zhou and Yuyi Li contributed equally to this work. Conceptualization and writing—original draf preparation, Wei Xiong; Methodology and validation, Yuxiang Zhou; Software and formal analysis, Yifeng Yuan and Kang Liu; Investigation and resources, Xudong Huang, Jingkun Li and Zechen Zhang; Data curation and supervision, Yuyi Li; Writing—review and editing, Xiaolin Shi and Miao’er Li.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Xiong, W., Zhou, Y., Li, Y. et al. In vitro assessment of the osteogenic and antibacterial capabilities of Mg-MOF particles with encapsulated Levofloxacin within polydopamine. Sci Rep 15, 26828 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-13056-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-13056-6