Abstract

This study presents a novel integration of the Water Ratio Index (WRI), Normalized Difference Chlorophyll Index (NDCI), Land Use/Land Cover (LULC) mapping, and Cellular Automata–Markov (CA–Markov) modeling with temperature fluctuations to monitor irrigated land dynamics using high-resolution (30m) satellite imagery in South Africa’s North West Province between 2016 to 2023, revealing critical challenges to agricultural sustainability and water resource management. Satellite imagery and geospatial analysis show irrigated lands concentrated in the region, which declined from 25,732 km2 to 24,322 km2, while urbanization expanded built-up areas from 4,146 to 6,581 km2, competing for arable land. The CA–Markov model predicts further agricultural loss by the year 2033, with barren land dominating (62.54%) and water bodies shrinking to 1.72%, worsening water scarcity. WRI values dropped from 0.40 in 2016 to 0.28 in 2023, reflecting increasing water stress, while temperatures rose sharply in summer, peaks up to 35.99 °C in 2023, intensifying evapotranspiration and irrigation demands. The study identifies institutional barriers such as biased subsidies, poor rural infrastructure, and climate extremes as key drivers of irrigation decline, mirroring global patterns in arid regions. The integration of the CA Markov model with WRI and temperature trends provides a robust framework for adaptive land-use planning, emphasizing stakeholder engagement and technology adoption to mitigate climate impacts and ensure food-water security in this vulnerable semi-arid region. This manuscript reflects the multi-dimensional approach to synthesizes multi-index, multi-temporal remote sensing analysis to deliver both spatial and predictive insights. This multi-model fusion bridges the gap between biophysical water availability, vegetation health, land transition trends, and future irrigation scenarios, offering a more holistic and scalable solution for water-scarce regions, driven by climate change provides critical insights into the interplay of water supply, land suitability, and climate variability, offering a foundation for adaptive strategies that support food security, livelihoods, and environmental sustainability in vulnerable regions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Agriculture irrigation, being one of the most crucial elements of the agricultural sector, helps to provide food security, economic development, and environmental stability on a global scale. The Earth’s system can be described as a complex web of interconnections, wherein irrigation methods profoundly impact the natural processes related to climate and environment1. Emphasizes that the Earth’s whole system must be considered while investigating the consequences of irrigation, which manifest as impacts on ecosystems, water cycles, and climate. Irrigation has historically progressed through distinct phases, shaping land use and water management strategies over time, dynamically simulate the complex relationships between urban expansion patterns and surface heat island formation while quantifying their cumulative impacts on irrigated agricultural systems and water sustainability2,3,4,5. Numerous studies have investigated the environmental impacts of irrigation, particularly its role in altering groundwater systems, exacerbating contamination risks, and exploring potential remediation approaches6,7,8. However, the North West Province of South Africa faces a critical water scarcity, coupled with climate change, making it a critical region for understanding and implementing sustainable irrigation practices. Agricultural irrigation is essential for food security and economic stability, yet in water-scarce areas like the North West Province, challenges such as climate variability and inefficient practices threaten the long-term sustainability of agriculture9.

Qadir et al. emphasize the intricacies of using wastewater in developing countries as they show how a broader approach should be used to deal with health and environmental risks while making profitable use of wastewater reuse10. In the North West Province of South Africa, the classification and management of irrigation water is critical for agricultural sustainability11. Meireles et al. have developed a new irrigation water classification framework subdivided into water quality components and availability to develop water management approaches tailored to specific issues12. With the world rapidly changing, irrigation becomes increasingly essential for the continuity of agriculture by making resource availability possible. Innovative tools such as Python and Google Earth Engine for land classification compromise dominant abilities to monitor land use changes that directly impact on irrigation planning and water resource management13,14. According to15irrigation is a key determinant of agricultural sustainability under changing climate conditions, highlighting the critical role of water quality and availability in sustaining agricultural productivity. Although water supply management and groundwater remediation techniques address technical and environmental issues, irrigation challenges also involve socio-economic and governance aspects16,17. The implementation of water-saving irrigation methods, including the advent of new technologies, offers greater possibilities, although achieving optimal deployment remains challenging. Predictive models like ANN, Random Forest, and Logistic Regression help assess groundwater contamination risks to support better water management18,19,20,21. Land Use/Land Cover (LULC) change, Water and Ratio Index (WRI) all dynamically interact with each other in terms of their effect on irrigated land systems, especially in situations of increasing agricultural demand and climate variability. Urbanization, agricultural expansion, and deforestation key drivers of land use and land cover (LULC) transformations significantly alter hydrological processes, leading to reduced water availability, groundwater contamination, decreased soil moisture retention, and lower irrigation efficiency22,23. Forecasting future LULC scenarios and effects on irrigated land sustainability can be predicted using the predictive modeling based on Cellular Automata (CA) and Artificial Neural Networks (ANN) machine learning algorithm24. The Northwest Africa’s rapidly urbanizing landscapes face critical environmental challenges as rising temperatures accelerate vegetation cover loss, intensify urban heat island (UHI) effects, and amplify carbon emissions25,26. A critical Water Ratio Index (WRI) data to quantify water stress as the balance between water supply and water demand to sustain irrigated agriculture27.

Speziale et al. used the modelling tools to explain the changes in groundwater levels caused by irrigation, which pose challenges in managing both surface and subsurface water resources28. At the national level, the context-specific issues and chances of agricultural irrigation vary in different regions. The fast-changing agricultural sector in China, with its high-tech farming and water resource management techniques, has severely changed the irrigation systems. Zhu et al. evaluate the evolution of irrigated agriculture in China and highlight the importance of sustainable water practices that provide farmers with water for their crops and preserve ecosystems29. Likewise, in Spain, the result of irrigation modernization is both social and ecological. Berbel et al., tested the impact of irrigation modernization from 2002 to 2015, which involved the change in crop water use efficiency, productivity, and land use patterns, among other factors and suggests the DSS for irrigation management in agriculture which is useful in water distribution activities and leads to higher water use efficiency and crop production30. It is the process of adoption of DSS systems that determines the level at which the irrigation management is improved and the amount of water that is available per unit of surface area28,30. Abduraimova et al., pointed to the list of water-saving technologies, which can be used for erosion control from irrigation, and there was a discussion about the possibility of using new technologies for soil degradation and water loss minimization in irrigated areas31. Soil, water, and climate elements are the local indicators of the complex system of interactions that create the particular trends of irrigation agriculture in a specific region. In the North West Province of South Africa, an area which is marked by water shortage and where climate change has become a serious problem, the effectiveness of irrigation systems is a key factor. Speelman et al., have been exploring the level of water efficiency in small-scale irrigation schemes, aiming at finding what determines water productivity and livelihood outlooks in the North West Province32. Groundwater geochemical characterization and drinking and irrigation suitability in Venter’s drop are appraised from the North West Province, emphasizing water quality management in agricultural sustainability. Another thing soil and water degradation in South Africa demands is putting together land and water management techniques to prevent soil erosion, salinization, and pollution risks33. Regardless of extensive global research on irrigation, the spatiotemporal mapping of irrigated areas in the North West Province from 2016 to 2023 remains limited, creating a knowledge gap that this study seeks to address.

This study aims to assess hydrological stress patterns through an integrated analysis of the Water Ratio Index, Digital Elevation Models, and temperature extremes, examining their combined effects on irrigation viability and groundwater depletion. It seeks to analyze the spatiotemporal dynamics of irrigated lands by quantifying LULC changes using satellite imagery, with a particular focus on the reduction of agricultural land. Additionally, the study aims to quantify projected land-use changes by analyzing the outcomes of the Cellular Automata-Markov (CA-Markov) model and to develop policy recommendations for sustainable land–water management by translating these model projections into targeted interventions that balance urban growth with irrigation needs.

Materials and methods

Study area

The North West Province of South Africa, located in the northern part of the country, covers an area of 104,882 km2 and shares borders with Botswana, Gauteng, Limpopo, Free State, and Northern Cape, as shown in (Fig. 1). The diversity of topography symbolizes the province. It has flat plains, gently rolling hills, and mountains. The altitude of the mountains is between 1,000 and 2,000 m above sea level. The climate of the North West Province is mostly slightly arid to arid, with cold summers and little winter. The yearly precipitation fluctuates across the province, with the average annual rainfall being 360–700 mm. The study area is nothing short of a farmland of agricultural significance, with agriculture being the prime economic activity in the region. The fundamental farming operations consist of the cultivation of crops (including livestock farming and horticulture) and irrigation systems built to use surface water, underground water, and rainwater harvesting34.

The North West Province is well-known for its crops, including maize, sorghum, sunflower, and fruits and vegetables, among others. Irrigation is pivotal in agriculture and livelihood continuity, especially in locations with low rainfall and erratic rain patterns35. The North West Province also accommodates various ecosystems composed of grassland, savannah, and bushveld, home to various wild animals. With the regions irrigated being a vital socioeconomic factor and being very much exposed to the effects of climate change, it is necessary to understand the complexity of the irrigated areas to guide water resource management, agricultural planning, and environmental conservation36. The region needs approaches that balance agricultural activities, protect land from mining, and help adapt to climate change to address its landscape degradation and Safeguard access to fresh water.

The geographical location of North West Province, South Africa (created in ArcGIS 10.4; https://desktop.arcgis.com).

Data collection

The temperature data for the research period from 2016 to 2023 was obtained from the South African Weather Service (SAWS). First, visit their official website https://www.weathersa.co.zaand navigate to the Climate Data or Historical Weather Sect38.. These datasets provide temperature data with an accuracy of ± 0.5 °C, reported in degrees Celsius (°C). To calculate the Water Ratio Index (WRI) from the Landsat 8–9 imagery, begin by accessing USGS Earth Explorer https://earthexplorer.usgs.gov39. The high-resolution Digital Elevation Model (DEM) of the North West Province was sourced from the Shuttle Radar Topography Mission (SRTM) at a resolution of 30 m or the Advanced Spaceborne Thermal Emission and Reflection Radiometer (ASTER)40which offers a similar resolution. The elevation data has an accuracy of ± 16 m (SRTM) and ± 10 m (ASTER).

Irrigated/non-irrigated land mapping

The classification of irrigated, non-irrigated, and other land types using the Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI) relies on distinct ranges that reflect vegetation health and moisture levels. Typically, NDVI values range from − 1 to + 1, with higher values indicating denser and healthier vegetation, often associated with irrigated areas, while lower values suggest sparse vegetation or non-vegetated surfaces41. The NDVI is often preferred over the SAVI and TVDI for broad vegetation monitoring since it’s simple, can be applied widely, and is highly related to plant health42. Even though both SAVI and TVDI analyses are used for soil issues and thermal data, NDVI is used more widely for larger studies because it only relies on Red and NIR, making it possible for all to use and save valuable time. Irrigated land is characterized by NDVI values greater than 0.4, indicating active, well-watered vegetation43,44while non-irrigated (rainfed) land falls within the range of 0.2 to 0.4, reflecting moderate vegetation primarily sustained by rainfall45. Other land types, including bare soil, urban areas, or water bodies, exhibit NDVI values below 0.2, with negative values often corresponding to water46,47. The NDVI is calculated using the formula shown in Eq. (1). Additionally, auxiliary data such as agricultural census data or irrigation infrastructure maps could be integrated to refine the model. Moreover, the Modified Vegetation Condition Index (MVCI) can also be calculated to assess the vegetation condition further, as shown in Eq. (2):

where: NIR = Near-Infrared Band, Red = Red Band.

where: NIR = Near-Infrared Band, Red = Red Band, Blue = Blue band.

Water ratio index (WRI) calculation

The Water Ratio Index (WRI) assesses vegetation water content, impacting irrigated land by monitoring crop health and water stress. The WRI results are better than the Normalized Difference Water Index (NDWI) in water body detection due to its enhanced sensitivity to moisture content and reduced susceptibility to soil and vegetation interference48. High WRI indicates well-watered vegetation, while low values suggest water stress. The methodology involves preprocessing Landsat data (atmospheric correction, radiometric calibration), extracting band values, and applying the WRI formula49. This index helps optimize irrigation, improve water use efficiency, and support sustainable agricultural practices by providing spatially explicit water status maps. The WRI is calculated using the following Eq. 3.

where: Green = Green Band, Red = Red Band, NIR = Near Infrared, SWIR = Shortwave Infrared.

Temperature analysis

The temperature analysis was completed for this research by looking at high-temperature and low-temperature trends from 2016 to 2023 with time-series data collected from the South African Weather Service (SAWS) meteorological stations. The monthly temperature change graphs were developed to identify seasonal patterns and long-term trends. The graph show the rise in maximum temperatures during the summer months, which is a clear indication of heatwaves and hot conditions, which may lead to water stress for crops. In contrast, the line graphs illustrated changes in minimum temperatures, which were shown to be colder in the winter, and may thus affect crop growth and irrigation schedules. Through the analysis of temperature data during the study period, it was observed that the climate factors that impact the irrigated areas and agricultural practices in the North West Province of South Africa.

DEM analysis

The digital elevation model (DEM) analysis in this research was carried out by looking into the topographic attributes within the area of study. High-resolution DEM data, collected from reliable sources such as SRTM and ASTER, were used to represent the terrain, expressed by slopes, elevations, and drainage patterns. DEM analysis showed that there are places with a high level of irrigation potential, mainly on the plain or in the valley, which are suitable for efficiently using water resources. However, places with sharp slopes or complex terrain were singled out as possible obstacles to irrigation infrastructure50. The DEM data is combined with other spatial data, e.g., land cover and hydrological information, providing a clear picture of where the best areas to grow crops with irrigation are, and how the province’s topography may affect water management practices in the North West Province of South Africa.

Assessment of LULC classification and accuracy assessment

In addition, the use of hybrid classification leads to better outcomes compared with using unsupervised or supervised learning methods. Every image was examined by giving signatures to each pixel and sorting the catchment into 6 categories using DN values for Bushland woody, open space, agricultural land, Forest land, water bodies, and Built-up land. For every LULC type, samples were formed by placing polygons around regions of that LULC type to avoid confusing them with other kinds of land use. In total, there were fifty-six spectral signatures found, and six of these matched specific categories in land use and land cover51. Then, the maximum likelihood classification (MLC) algorithm was applied to the image, and during classification, the analyst picked out a few of the pixels.

The area shifts between LULC classes during the study were displayed as a transition matrix using ArcGIS Desktop 10.4. In mixed pixels, the results were improved by analyzing the images and adjusting them continually with the aid of topography maps and high-quality aerial or satellite imagery52. The study compared the ground data with the results from remotely sensed data to test their accuracy. The stratified method on LULC maps stands for different classes. The results were established with graphs and compared to the ground truth data, using a minimum of 60 pixels per type to determine accuracy. Both the error matrix and non-parametric Kappa statistics were used to summarize the data. You can see the methodological framework for this study in Fig. 2.

CA Markov model

Many complex systems have been explored using CA mathematical models. The status of each cell in California is determined by its neighbors’ status and by a specified set of instructions. People use CA to represent both physical, biological, and social systems in nature, as well as artificial systems53. This analysis allows us to follow the automaton’s behavior and predict what it might do in the future. With it, we can make predictions about future behavior and discover recurring trends in the actions of the system54,55.

The model uses the ways grid size, cellular space, neighborhood, and transition rules interact with each other. The model for a cellular automaton using the Markov technique can be expressed as:

At time t, the state vector is p(t), and when we look ahead, we have p(t + 1); and T contains the transition probabilities. It defines the probability of going from one current state to any of the future states. The state vector p(t) represents each cell’s state in the grid at time t, and it has a column form. Every number in the vector shows the value for that cell on the grid, and the sum of all the numbers must equal 1. Suppose there are only three possible states for cells (0, 1, and 2). In such a case, the state vector would need three entries, showing the proportions of each state among all cells.

A transition matrix T is always formed as a square matrix of the same size as the number of possible states. Every value in the matrix shows the likelihood of going from one current state to another future state. This important value represents the possibility that a system will move from state i to state j. The projection onto the matrix T updates the state vector as time moves on, according to p(t + 1) = T ∗ p(t). Using the initial state vector p (0), the equation allows you to get the state vector p (t + 1) from p (t). To study how the cellular automata behave, we look at the state vector as time increases indefinitely. In certain cases, the whole set of cells will reach an equilibrium condition and stay there, each cell type being represented by a steady-state value (Al-sharif and Pradhan, 2014). The steady-state vector can be calculated by solving the equation p = T ∗ p, where p is the steady-state vector56,57.

Results and discussion

The research outcomes have significantly contributed to understanding the relationship between irrigated lands, Water Ratio Index, Land Use Land Cover changes, and temperature in the North West Province, South Africa, from 2016 to 2023. Analysis through satellite imagery and land use classification revealed distinct spatial variations between irrigated and non-irrigated areas, with most irrigated lands situated on flat slopes and in river valleys, where water distribution is more manageable. The extremely important policy, socioeconomic and institutional factors that are often left out of the equation, preventing a contextual understanding of the micro decision making in irrigation and in circumstances such as those in South Africa’s North West Province, where water governance is playing a decisive role in the making of decisions on how to allocate resource58. It has been proven that agricultural subsidies, for example, the Comprehensive Agricultural Support Programme (CASP) in South Africa, have biased adoption of irrigation to smallholder farmers in Sub-Saharan Africa59 while inadequate rural infrastructure, including prevalent power and water delivery systems has hindered efficient irrigation60. The institutional and socioeconomic barriers we identify are echoed in findings from other water-scarce regions (Wichelns, 2015) and must be included in any truly robust analysis of agricultural water use. Attending to these dimensions would make the study consistent with global research on irrigation governance and increase its policy relevance for the sustainable management of irrigation in arid and semi-arid areas.

Temporal analysis of temperature trends uncovered seasonal cycles characterized by extreme heat in summer and cold conditions in winter. Furthermore, integrating temperature data with land cover and hydrological information provided a more holistic perspective on the factors influencing irrigated areas and water resource management in the region. The findings underscore the necessity for developing water adaptation strategies and climate-resilient agricultural practices to mitigate the impacts of climate change on irrigated agriculture in the North West Province. Lastly, the data obtained offer valuable insights into the variability of irrigation and temperature, forming a foundation for the sustainable management of water resources and agricultural development in the region.

Classifications of land use land cover

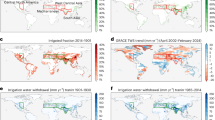

The Land Use and Land Cover (LULC) changes in the North West Province of South Africa significantly impact irrigated land (see Fig. 3), which falls under the broader Agriculture class covering 25,732 km2 in the year 2013 and 24,322 km2 in the year 2023 (see Table 2). Built-up Land 4,146 km2 in 2013 and 6,581 km2 in the year 2023 have been expanded by urbanization and mining activities which compete with arable lands due to the reduction of arable areas for irrigation. Furthermore, Barren Land which contain 62,929 km2 in 2013 and 63,152 km2 consisting essentially of arid and mining degraded zones also contracts the irrigated area due to less fertile soil availability (see Table 2). Though Forest Land which contain 9,244 km2 8,102 km2, and Water Bodies 2,098 km2, 1,992 km2 in the year 2013 and 2023, support ecosystem stability, large climate variability and water scarcity limit irrigation efficiency.

Land use land cover maps of North West Province of South Africa (created in ArcGIS 10.4; https://desktop.arcgis.com).

The CA-Markov model framework to assess and predict how Land Use Land Cover (LULC) changes and index-based agricultural drought vulnerability jointly impact irrigated lands, combining multi-temporal satellite data61,62. As shown in Fig. 3 presents a detailed map explaining the distribution of land cover across the region, classified into five categories. The LULC maps shows that Barren Land, occupying 60.37% of the total area in the year 2013 and 60.63% in the year 2023 (see Table 2), is the most dominant land cover type, highlighting the extensive presence of non-vegetative regions, which may indicate land degradation or arid conditions. Agriculture Land, which covers 24.68% of the area in the year 2013 and 23.35% in the year 2023, is primarily concentrated in the central and southern parts of the region, reflecting the region’s heavy reliance on agriculture63,64.

Forest Land, accounting for 8.86% and 7.77% of the land cover in 2013 and 2023, is mainly located in the northern and eastern parts, which highly impact on irrigated land and emphasizes the need for conservation efforts to maintain ecological balance and biodiversity. Built-up Land, representing 3.97% and 6.31% of the area, indicates the extent of urbanization, while Water Bodies, covering only 2.01%, and 1.91% highlight the limited surface water resources in the region (see Table 2). Due to the dominance of rainfed agriculture in the province, irrigated land is already short and LULC shifts such as encroachment of urban areas, degradation of soil and the depletion of water resource, are threatening its sustainability (see Table 1). A key economic driver of many economies is mining activities that compete for water resources with agriculture, exacerbating pressure on irrigated systems65. In addition, the proportion of Water Bodies is relatively small, indicating dependence on a limited number of water sources and therefore increased vulnerability to droughts and water over-extraction for irrigation. If LULC trends persist, irrigated agriculture could suffer diminished productivity and farmers will be driven to adopt more water efficient responses or simply abandon cultivation in marginal areas66. Built-up Land, representing 2.65% of the area, indicates the extent of urbanization, while Water Bodies, covering only 0.35%, highlight the limited surface water resources in the region. Conservation strategies should be prioritized for the forested regions to protect biodiversity and enhance carbon sequestration, which is vital for mitigating climate change67. Additionally, as urbanization is likely to increase, careful urban planning should be employed to minimize the environmental impact of built-up areas, mainly to preserve the limited water resources. These recommendations are essential for fostering sustainable development while balancing the need for economic growth with environmental preservation.

Prediction of LULC based on integrated CA MARKOV model

The CA-Markov model predicts LULC changes for 2033, indicating a significant impact on irrigated land and water ratio index (see Fig. 4). This figure shows the built-up land is expected to increase, encroaching on agricultural land and water bodies, leading to a decline in agriculture area from 22,311 km2 (see Table 3). Forest land may also face threats, decreasing from 5,319 km2. Water bodies, crucial for irrigation, might shrink, affecting the water ratio index. Barren land, covering 65,137 km2, may remain stable or increase due to land degradation (see Table 3). The predicted changes will likely alter the hydrological cycle, groundwater recharge, and surface runoff, exacerbating water scarcity and affecting agricultural productivity68.

The CA-Markov model’s predictions suggest a need for sustainable land-use planning and water management practices to mitigate these impacts and ensure environmental sustainability69. Effective management strategies can help balance the competing demands on land and water resources, protecting agricultural productivity and ecosystem services. By analyzing the predicted changes, policymakers can develop targeted interventions to minimize the adverse effects on irrigated land and water resources.

CA-Markov model-based LULC simulation map of the North West Province of South Africa (created in ArcGIS 10.4; https://desktop.arcgis.com).

Assessment of digital elevation model

Figure 5 illustrates the influence of Digital Elevation Model (DEM), Flow Direction, Flow Accumulation maps are essential for comprehending hydrological processes, and their effects on irrigated land and Water Ratio Index (see Fig. 5). DEM are critical for mapping terrain features, slope gradients, and watershed delineation, which directly affect irrigation efficiency and water distribution. In high-elevation areas which contain 1,788 m (see Fig. 6), steep slopes and increased runoff reduce water retention, limiting irrigation potential. Conversely, lower elevations, which contain 920 m, may face waterlogging or salinization due to poor drainage (see Fig. 5a), further diminishing arable land suitability. The region’s topography is depicted by the DEM, which highlights elevation changes that affect irrigation potential and water flow patterns70. Irrigable lands are further reduced by land-use changes like urbanization and deforestation, which interfere with natural hydrological cycles. In the Lancing-Mekong Basin, deforestation decreased soil moisture and irrigation expansion raised evapotranspiration but depleted groundwater, resulting in complicated trade-offs in water availability. By combining high-resolution DEM with sophisticated hydrological models, these problems can be lessened, and irrigation planning and water consumption can be maximized. Water movement across the landscape is depicted on the Flow Direction map (see Fig. 5b), which also identifies natural drainage channels that are crucial for effective irrigation planning and water resource management.

Digital elevation, flow direction, and flow accumulation analysis of the North West Province, South Africa (created in ArcGIS 10.4; https://desktop.arcgis.com).

The red color showed 1788 m, the highest elevation value on the map, whereas the valleys and low at 920 m are shown by the dark blue color71. The Flow Accumulation map (see Fig. 5c), on the other hand, shows locations where water converges, identifying possible waterlogging zones or places with high irrigation appropriateness because of greater moisture availability. Collectively, these analyses show how the hydrological dynamics and geography of the province impact irrigated agriculture, with higher elevations needing artificial irrigation systems while low-lying areas probably benefit from natural water storage. The results highlight how crucial it is to include geospatial data into agricultural planning in order to maximize crop output, reduce the risk of flooding, and optimize water consumption across the diverse landscapes of the North West Province. Stakeholders may create focused irrigation plans that complement the region’s natural water flow patterns by utilizing this information, guaranteeing sustainable land usage and better agricultural results.

Elevation map of the North West Province, South Africa (created in Origin Pro 2024; https://www.originlab.com).

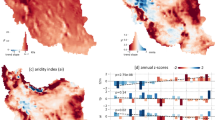

Assessment of water radio index

Figure 7 shows the Water Ratio Index (WRI) maps, which demonstrations the levels of water availability and suitability for irrigation across the North West Province of South Africa for the period 2016 to 2023, depicts the data comprehensively (see Fig. 7). The color scheme in these maps range from dark blue show the high WRI to parrot shows the low values, with intermediate shades of blue, sea green, green, and yellow representing decent water availability (see Fig. 7). This figure shows the spatial distribution of the WRI values, which serve to evaluate the temporal changes and patterns in the water resource dynamics during the specified eight year period.

Water Ratio Index maps for the years: (a) 2016, (b) 2017, (c) 2018, (d) 2019, (e) 2020, (f) 2021, (g) 2022, (h) 2023. (created in ArcGIS 10.4; https://desktop.arcgis.com).

The index initiated in the year 2016 with a highest value of 0.399601 and a low of − 0.228852, indicating a relatively wide range of water-related conditions. However, by the year 2017, the high value slightly decreased to 0.370423, while the low dropped further to − 0.310497, suggesting increasing hydrological variability or stress. A minor rebound occurred in 2018, with the high rising to 0.381924 and the low improving to − 0.258741, before a sharp decline in 2019, where the high fell to 0.36276 and the low plummeted to − 0.44208, marking the most extreme negative value in the dataset likely reflecting severe drought or water scarcity events (see Fig. 8). In the year 2020, the value of WRI, like to 0.356562 (depicted in dark blue), was the highest, indicating regions with enough water resources for irrigation. By contrast, the smallest value of WRI in the year 2020 is − 0.289942, which the parrot signifies, implies the areas suffering from water stress or scarcity. Spatial variability in water availability is depicted on the map, with some regions having high WRI values and others potentially facing water scarcity or restrictions (see Fig. 8), while 2021 recorded further declines in the high value is 0.331436 but a slight recovery in the low value is − 0.240494.

Similar to the case of the other variables, one can trace the same pattern of spatial variation where the alterations in the WRI values reflect the changes in precipitation, evapotranspiration, and soil moisture levels across the province. The areas at a high elevation or close to the water bodies will have greater WRI values, whereas the regions with steep slopes or remote from the water will be less than others. By the year 2022, the high value of WRI stabilizes and rises to 0.308123, while the lowest value decreases to − 0.302191 (see Fig. 8). The map shows the daily variation in the availability of water resources, which is a function of climate variables, land utilization, and water management72. In water resources, the temporal changes in water availability are paramount for informing the management strategies and dealing with water stress challenges that affect agriculture and general livelihoods. Likewise, the year 2023, the high value reached its lowest point 0.281436, though the low value stabilized at − 0. 240,494 (see Fig. 8). The map exposes fluctuations of WRI values over time, showing that an adaptive water management policy is essential for water resource management owing to the ever-changing water resource problems in North West Province. By studying these WRI maps throughout the eight years, decision-makers can be advantageous as they can understand how water availability has been changing over time and space; this will guide the decision-making on sustainable water resource management and agricultural development in the area.

Assessment of seasonal temperature fluctuations

The monthly temperature change in the North West Province of South Africa between 2016 and 2023 shows illustrate fluctuating high and low temperatures across different months, revealing notable variations over the years (See. Figure 9). The figure gives a clear picture of how to perform an in-depth analysis of the seasonal temperature changes and fluctuations during the given period. The following rows give temperature data from 2016 to 2017, 2018–2019, 2020–2021, and 2022–2023, allowing the comparison between different periods. Figure 9a shows the graphs of the temperature variation for the North West province of South Africa in 2016 to 2017. This graph was helpful implement for understanding the seasonal changes in temperature for the region. The graph contains a blue line illustrating the low temperature values for the whole year and a red line representing the high temperature values (see Fig. 9a). To begin with, the January graph demonstrates a high temperature of 26.01 °C and a low temperature of 20.23 °C. During the end of this month and as the year progresses into February, temperatures remain relatively high, the highest being 28.6 °C and the low being 18.1 °C. Unlike February, temperature decreases slightly in March as high are 27.21 °C and lows are 15.81 °C. In the region of the North West Province of South Africa, the April and May temperatures drop to even lower degrees, ranging from 26.44 °C to 24.21 °C in April and 13.91 °C to 11.05 °C in May. The month June, July, and August, which are our winter months, produce low temperatures. June has highs of 22.01 °C and lows of 10.01 °C, July has highs of 20.22 °C and lows of 10.71 °C, and August has highs of 21.32 °C. While spring starts in September and October, temperatures start to rise again, reaching 23.21 °C and 24.55 °C in highs and 14.44 °C and 15.91 °C in lows. November also witnessed an increase in temperature, with a high of 26.45 °C, while in December, the temperature reached the maximum summer level of 29.21 °C. Overall, 2016–2017 displayed moderate temperatures with minimal extremes. The 2018–2019 period saw higher daytime temperatures but colder nights, indicating greater variability (see Fig. 9b). January’s high surged to 30.01 °C, while the low dropped to 20.23 °C, marking a 10 °C difference. The graph of temperature variation for the North West province of South Africa from 2020 to 2021 describes the seasonal variations in temperature across the region. A clear illustration of the yearly climatic changes is provided by graphically depicting the temperature values on the vertical axis and the months of the year along the horizontal axis. The blue line graph clearly shows the low temperature values recorded in each of the months, while the orange line graph illustrates the highest temperature readings. The graph shows the maximum range of 32.01 °C and minimum range of 21.22 °C in January. There is a slight decrease in temperatures during February and March. The highs are 31.03 degrees Celsius in February and 30.22 degrees in March, while the lows are 20.03 degrees in February and 18.55 degrees in March. April and May are when the weather becomes cooler in the year. During this season, the temperatures might range from 27.22 to 15.09 degrees Celsius in April and from 13.05 to 26.21 °C in May. In the winter months of June, July, and August, temperatures further decrease, with June having highs of 23.22 °C and lows of 13.05 °C, July having highs of 21.01 °C and lows of 12.09 °C, and August having highs of 22.22 °C Fall also has its beauty. However, it does not last as long as Spring or Winter. Sometimes, by late September and early October, temperatures begin to rise again, reaching highs of 24.41 °C in September and 27.22 °C in October. The temperature variation graph shows the seasonal changes and their temperature amounts. November shows the highest of 29.22 °C, while December shows the lowest overall.

The 2020–2021 data showed further warming in highs, with January reaching 32.01 °C (high) and 21.22 °C (low), a notable increase from previous years (see Fig. 9c). The month of February showed high temperature was 31.03 °C and low was 20.03 °C, continuing the upward trend. The month March (30.22 °C high, 18.55 °C low) and April (27.22 °C high, 17.22 °C low) maintained warmer conditions, though nights remained cooler than in 2016–2017. May (26.21 °C high, 15.09 °C low) and June (23.22 °C high, 13.05 °C low) saw slightly lower highs but still colder nights compared to earlier years. July and August recorded modest highs (21.01 °C and 22.22 °C) but maintained cool lows (12.09 °C and 14.44 °C) (see Fig. 9c). September and October warmed again (24.41 °C and 27.22 °C highs), with lows rising slightly (16.9 °C and 17.21 °C). November (29.22 °C high, 20.22 °C low) and December (31.21 °C high, 22.87 °C low) ended the year with record-high temperatures, suggesting a clear warming trend.

The temperature variation graph for the North West province of South Africa in 2022–2023, as shown in (Fig. 9d) displays the temperature fluctuation observed across the region through an annual cycle. The graph, which has the vertical axis representing temperature values and the horizontal axis representing the months of the year, offers a detailed look at the climatic changes that can be witnessed over the year. The blue line graph shows the lowest temperature values for each month, and the orange line shows the highest temperature value for a month. The graph, which starts from January, shows a peak of 35.99 °C and a minimum of 23.22 °C (see Fig. 9d). Towards the end of January and throughout February, temperatures remain comparatively high, with February recording highs of 33.21 °C and lows of 21.34 degrees Celsius, while March has highs of 30.03 °C and lows of 19.24 °C. The transition from warm weather to cooler temperatures happens in April and May, with temperatures ranging between 28.09 and 14.32 °C in April and 26.31 and 12.35 °C in May. The winter months of June, July, and August have more decreases in temperature, with June having highs of 23.44 °C and lows of 12.35 °C, July with highs of 22.31 °C and lows of 12.33 °C, and August with highs of 24.22 °C, when the spring season shows up in September and October, the temperatures begin to rise again reaching the maximum temperature of 25.41 °C in September and 27.25 °C in October. However, for November, a sharp decrease in temperature occurs, with highs of only 20.25 °C, in contrast to the return of warm weather in December, with the highest temperatures reaching 32.22 °C.

Assessment of temporal changes in irrigated land

The Temporal Changes in Irrigated Land analysis is shown in Fig. 10. The trends in irrigated land over an 8-year period show both high and low values that indicate fluctuations in irrigation extent and efficiency. The data reveals a consistent decline in irrigated land, with the high values decreasing from 0.80045 in 2016 to 0.28162 in 2023, while the low values, though fluctuating, remain negative throughout the period, reaching − 0.2578361 in 2023 (see Fig. 10). This downward trend suggests a reduction in both the availability and productivity of irrigated land, which can be attributed to multiple environmental, economic, and policy-related factors. In the year 2016, the high value of irrigated land is 0.80045 suggests relatively stable irrigation coverage, while the low value − 0.42553 indicates early signs of water stress or inefficiency.

By the year 2017, the high value drops to 0.72174, signaling reduced irrigation expansion, while the low value worsens slightly − 0.438712, reflecting growing water scarcity or mismanagement. The trend continues in the year 2018, with the high value falling further to 0.6578371 and the low value plunging to − 0.63172 the lowest in the dataset likely due to severe drought or groundwater depletion. In the year 2019 shows a slight improvement in low values which is − 0.348819, possibly from better rainfall or temporary conservation measures, but the high value 0.616912 keeps declining, indicating long-term irrigation challenges. In the year 2020, both high value 0.59127 and low − 0.41521 values remain subdued, as the COVID-19 pandemic may have disrupted farming inputs and labor. The most dramatic drop occurs in 2021, with the high value collapsing to 0.33146 and the low value hitting − 0.517212, likely due to compounding climate extremes (e.g., droughts or floods) and economic disruptions. By the year 2022 sees a minor recovery in the high value 0.37161, but the low value − 0.43851 stays negative, suggesting persistent inefficiencies. In the year 2023, the high value reaches its lowest point 0.28162, though the low value improves slightly − 0.2578361, hinting at partial adaptation efforts.

Changes and variability in irrigated areas: (a) 2016, (b) 2017, (c) 2018, (d) 2019, (e) 2020, (f) 2021, (g) 2022, (h) 2023. (Is created in ArcGIS 10.4; https://desktop.arcgis.com).

One of the primary reasons for this decline is climate change, which has led to irregular rainfall patterns, prolonged droughts, and reduced water availability in many agricultural regions. As freshwater sources diminish, farmers struggle to maintain irrigation systems, leading to abandoned fields or reduced crop yields. Additionally, over-extraction of groundwater for irrigation has depleted aquifers, particularly in heavily farmed areas, making water access even more challenging. Competition for water resources from urbanization, industry, and domestic use further exacerbates the problem, leaving less water available for agriculture. These maps are essential for tracking changes in agricultural land use and supporting the decision-making processes related to water management and sustainable agriculture in the North West Province.

Conclusion

This study assesses the interactions between irrigated lands, the Water Ratio Index (WRI), Land Use/Land Cover (LULC) changes, and temperature fluctuations in South Africa’s North West Province from 2016 to 2023. It highlights critical challenges to agricultural sustainability and water resource management, demonstrating the value of geospatial tools like WRI and CA-Markov for monitoring land and water dynamics. This study contributes to the literature by integrating multiple geospatial indices and modeling techniques, which provide a more holistic and scalable solution to understanding irrigated land dynamics, a gap that has not been fully addressed in previous research. The results show a significant reduction in agricultural land and an increase in water stress, as evidenced by declining WRI values and rising temperatures. This study offers new insights into the interaction between water availability, vegetation health, and land-use changes in semi-arid regions. Furthermore, the use of the CA-Markov model projects future land transformations, indicating a continued decline in agricultural land and increasing competition from urbanization and mining. In terms of theoretical and managerial implications, the study underscores the importance of integrated water management and the adoption of climate-smart agricultural practices to mitigate the effects of water scarcity and climate change. It also highlights the need for forest conservation, improved infrastructure, and regulation of mining water use to support sustainable irrigation systems. The findings suggest that policymakers must address skewed subsidies and poor governance to improve agricultural water management in the region.

Limitations: This study relied on remote sensing and modeling data, which may not fully capture localized ground realities or socio-economic changes. Future research should incorporate field validation, socio-economic surveys, and dynamic climate forecasts to improve the accuracy of the predictions.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- AMSR:

-

Advanced microwave scanning radiometer

- ASTER:

-

Advanced spaceborne thermal emission and reflection radiometer

- CA-Markov:

-

Cellular Automata-Markov chain model

- DEM:

-

Digital Elevation Model

- DSS:

-

Decision support system

- LULC:

-

Land Use Land Cover

- MVCI:

-

Modified vegetation condition index

- NDVI:

-

Normalized difference vegetation index

- SRTM:

-

Shuttle radar topography mission

- TRMM:

-

Tropical rainfall measuring mission

- WRI:

-

Water ratio index

References

Iqbal, J. et al. Assessment of landcover impacts on the groundwater quality using hydrogeochemical and geospatial techniques. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. (2023).

Turral, H., Svendsen, M. & Faures, J. M. Investing in irrigation: reviewing the past and looking to the future. Agric. Water Manage. 97 (4), 551–560 (2010).

Al Kafy, A., Dey, N. N., Saha, M., Altuwaijri, H. A., Fattah, M. A., Rahaman, Z. A.,… Rahaman, S. N. (2024). Leveraging machine learning algorithms in dynamic modeling of urban expansion, surface heat islands, and carbon storage for sustainable environmental management in coastal ecosystems. Journal of Environmental Management, 370, 122427.

Zhang, W. et al. Health risk assessment during in situ remediation of cr (VI)-Contaminated groundwater by permeable reactive barriers: A Field-Scale study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 19 (20), p13079 (2022).

Almulhim, A. I., Al Kafy, A., Ferdous, M. N., Fattah, M. A. & Morshed, S. R. Harnessing urban analytics and machine learning for sustainable urban development: A multidimensional framework for modeling environmental impacts of urbanization in Saudi Arabia. J. Environ. Manage. 357, 120705 (2024).

Jat Baloch, M. Y. et al. Arsenic removal from groundwater using iron pyrite: influence factors and removal mechanism. J. Earth Sci. 34 (3), 857–867 (2023).

Khalid, W. et al. Groundwater contamination and risk assessment in greater palm springs. Water 15 (17), 3099 (2023).

Hussein, E. E. et al. Machine learning algorithms for predicting the water quality index. Water 15, 20 (2023).

Mothupi, L. W. Towards the development of an integrated governance mechanisms for recurrent drought in the North West Province, Republic of South Africa. (2020).

Qadir, M. et al. The challenges of wastewater irrigation in developing countries. Agric. Water Manage. 97 (4), 561–568 (2010).

Botlhoko, G. J. Factors associated with the revitalisation of smallholder irrigation schemes among farmers in the North West Province, South Africa. (2017).

Meireles, A. C. M. et al. A new proposal of the classification of irrigation water. Revista Ciência Agronômica. 41, 349–357 (2010).

Jat Baloch, M. Y. et al. Hydrogeochemical mechanism associated with land use land cover indices using geospatial, remote sensing techniques, and health risks model. Sustainability 14 (24), 16768 (2022).

Nigar, A. et al. Comparison of machine and deep learning algorithms using Google Earth engine and python for land classifications. Front. Environ. Sci. 12, 1378443 (2024).

Jat Baloch, M. Y. et al. Shallow groundwater quality assessment and its suitability analysis for drinking and irrigation purposes. Water 13 (23), 3361 (2021).

Jat Baloch, M. Y. et al. Effects of arsenic toxicity on the environment and its remediation techniques: A review. J. Water Environ. Technol. 18 (5), 275–289 (2020).

Tariq, A. et al. Spatio-temporal variation of seasonal heat islands mapping of Pakistan during 2000–2019, using day-time and night-time land surface temperatures MODIS and meteorological stations data. Soc. Environ. 8, 100779 (2022).

Tariq, A. et al. Terrestrial and groundwater storage characteristics and their quantification in the chitral (Pakistan) and Kabul (Afghanistan) river basins using GRACE/GRACE-FO satellite data. Groundw. Sustain. Dev. 23, 100990 (2023).

Jat Baloch, M. Y. et al. Groundwater contamination, fate, and transport of fluoride and nitrate in Western jilin, china: implications for water quality and health risks. Environ. Chem. Ecotoxicol. 7, 1189–1202 (2025).

Iqbal, J. et al. Hydrogeochemistry and prediction of arsenic contamination in groundwater of vehari, pakistan: comparison of artificial neural network, random forest and logistic regression models. Environ. Geochem. Health. 46 (1), 14 (2024).

Jat Baloch, M. Y. et al. Utilization of sewage sludge to manage saline-alkali soil and increase crop production: is it safe or not?. Environ. Technol. Innov. 8, 103266 (2023).

AlDousari, A. E. et al. Modelling the impacts of land use/land cover changing pattern on urban thermal characteristics in Kuwait. Sustain. Cities Soc. 86, 104107 (2022).

Iqbal, J. et al. Groundwater fluoride and nitrate contamination and associated human health risk assessment in south Punjab, Pakistan. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. p. 1–20 (2023).

Sonet, M. S., Hasan, M. Y., Kafy, A. A. & Shobnom, N. Spatiotemporal analysis of urban expansion, land use dynamics, and thermal characteristics in a rapidly growing megacity using remote sensing and machine learning techniques. Theoret. Appl. Climatol. 156 (2), 79 (2025).

Rahaman, Z. A. et al. Assessing the impacts of vegetation cover loss on surface temperature, urban heat Island and carbon emission in Penang city, Malaysia. Build. Environ. 222, 109335 (2022).

Saha, M. et al. Modelling microscale impacts assessment of urban expansion on seasonal surface urban heat island intensity using neural network algorithms. Energy Build. 275, 112452 (2022).

Hatami, A., Farokhzadeh, B. & Bazrafshan, O. Water footprint and stress index assessment in mediterranean agriculture. Environ. Monit. Assess. 197 (3), 301 (2025).

Speziale, P. et al. Protein-based biofilm matrices in Staphylococci. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 4, 171 (2014).

Zhu, Q., Sarkis, J. & Lai, K. Institutional-based antecedents and performance outcomes of internal and external green supply chain management practices. J. Purchasing Supply Manage. 19 (2), 106–117 (2013).

Berbel, J. et al. Analysis of irrigation water tariffs and taxes in Europe. Water Policy. 21 (4), 806–825 (2019).

Abduraimova, K. Contagion and tail risk in complex financial networks. J. Banking Finance. 143, 106560 (2022).

Speelman, S. Water use efficiency and influence of management policies, analysis for the small-scale irrigation sector in South Africa (Ghent University, 2009).

Du Preez, C. & Van Huyssteen, C. Threats to soil and water resources in South Africa. Environ. Res. 183, 109015 (2020).

Sandham, L. A. & Pretorius, H. M. A review of EIA report quality in the North West Province of South Africa. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 28 (4–5), 229–240 (2008).

Botai, C. M. et al. Characteristics of droughts in South africa: A case study of free state and North West provinces. Water 8 (10), 439 (2016).

Thorn, M. et al. What drives human–carnivore conflict in the North West Province of South africa?? Biol. Conserv. 150 (1), 23–32 (2012).

Meque, A. et al. Numerical weather prediction and climate modelling: challenges and opportunities for improving climate services delivery in Southern Africa. Clim. Serv. 23, 100243 (2021).

Parida, B. R. et al. Comparative assessment of satellite-based models through Planetscope and landsat-8 for determining physico-chemical water quality parameters in Varuna River (India). Appl. Water Sci. 15(3), 55 (2025).

Farr, T. G. et al. The shuttle radar topography mission. Rev. Geophys. 45, 2 (2007).

Abrams, M. et al. The aster global dem. Photogram. Eng. Remote Sens. 76 (4), 344–348 (2010).

Ali, A. et al. Examining the landscape transformation and temperature dynamics in Pakistan. Sci. Rep. 15 (1), 2575 (2025).

Xue, J. & Su, B. Significant remote sensing vegetation indices: A review of developments and applications. J. Sens. 2017 (1), 1353691 (2017).

Xie, Y., Sha, Z. & Yu, M. Remote sensing imagery in vegetation mapping: a review. J. Plant. Ecol. 1 (1), 9–23 (2008).

Ozdogan, M., Yang, Y., Allez, G. & Cervantes, C. Remote sensing of irrigated agriculture: opportunities and challenges. Remote Sens. 2 (9), 2274–2304 (2010).

Biradar, C. M. et al. A global map of rainfed cropland areas (GMRCA) at the end of last millennium using remote sensing. Int. J. Appl. Earth Observ. Geoinf. 11(2), 114–129 (2009).

Tucker, C. J. Red and photographic infrared linear combinations for monitoring vegetation. Remote Sens. Environ. 8 (2), 127–150 (1979).

Huete, A. et al. Overview of the radiometric and biophysical performance of the MODIS vegetation indices. Remote Sens. Environ. 83 (1–2), 195–213 (2002).

Laonamsai, J. et al. Utilizing NDWI, MNDWI, SAVI, WRI, and AWEI for estimating erosion and deposition in Ping river in Thailand. Hydrology 10 (3), 70 (2023).

Sethi, R. R. et al. Exploring hydrological and environmental transformations by tank structures in odisha using sentinel-2 data. (2025).

Polidori, L., Hage, E. & M Digital elevation model quality assessment methods: A critical review. Remote Sens. 12 (21), 3522 (2020).

Gao, J. & Liu, Y. Determination of land degradation causes in Tongyu county, Northeast China via land cover change detection. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 12 (1), 9–16 (2010).

Harris, P. M. & Ventura, S. J. The integration of geographic data with remotely sensed imagery to improve classification in an urban area. Photogram. Eng. Remote Sens. 61 (8), 993–998 (1995).

Zhou, L., Dang, X., Sun, Q. & Wang, S. Multi-scenario simulation of urban land change in Shanghai by random forest and CA-Markov model. Sustain. Cities Soc. 55, 102045 (2020).

Muller, M. R. & Middleton, J. A Markov model of land-use change dynamics in the Niagara Region, Ontario, Canada. Landsc. Ecol. 9, 151–157 (1994).

Tariq, A. et al. Land surface temperature relation with normalized satellite indices for the Estimation of spatio-temporal trends in temperature among various land use land cover classes of an arid Potohar region using Landsat data. Environ. Earth Sci. 79, 1–15 (2020).

Al-sharif, A. A. & Pradhan, B. Monitoring and predicting land use change in Tripoli metropolitan City using an integrated Markov chain and cellular automata models in GIS. Arab. J. Geosci. 7, 4291–4301 (2014).

Sejati, A. W., Buchori, I. & Rudiarto, I. The spatio-temporal trends of urban growth and surface urban heat Islands over two decades in the Semarang metropolitan region. Sustain. Cities Soc. 46, 101432 (2019).

Bosch, H. J. & Gupta, J. Access to and ownership of water in Anglophone Africa and a case study in South Africa. Water Altern. 13, 2 (2020).

Li, M. Multiple-Season Farming and Resilience: Linking Agriculture Food Security and Nutrition (McGill University, 2023).

Wichelns, D. Water productivity and water footprints are not helpful in determining optimal water allocations or efficient management strategies. Water Int. 40 (7), 1059–1070 (2015).

Kafy, A. A. et al. Assessment and prediction of index based agricultural drought vulnerability using machine learning algorithms. Sci. Total Environ. 867, 161394 (2023).

Kafy, A. A. & Altuwaijri, H. A. Eco-climatological modeling approach for exploring spatiotemporal dynamics of ecosystem service values in response to land use and land cover changes in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 155(11), 9497–9516 (2024).

Digra, M., Dhir, R. & Sharma, N. Land use land cover classification of remote sensing images based on the deep learning approaches: a statistical analysis and review. Arab. J. Geosci. 15 (10), 1003 (2022).

Awad, M. Google earth engine (GEE) cloud computing based crop classification using radar, optical images and support vector machine algorithm (SVM). IEEE.

Jeyavathana, R. B. Land use and land cover classification using landsat-8 multispectral remote sensing images and long short-term memory-recurrent neural network (AIP Publishing, 2024).

Magidi, J. et al. Application of the random forest classifier to map irrigated areas using Google Earth engine. Remote Sens. 13 (5), 876 (2021).

Praticò, S. et al. Machine learning classification of mediterranean forest habitats in Google Earth engine based on seasonal sentinel-2 time-series and input image composition optimisation. Remote Sens. 13 (4), 586 (2021).

Kumar, C. P. Climate change and its impact on groundwater resources. Int. J. Eng. Sci. 1 (5), 43–60 (2012).

Kafy, A. A. et al. Predicting the impacts of land use/land cover changes on seasonal urban thermal characteristics using machine learning algorithms. Build. Environ. 217, 109066 (2022).

Wu, S., Li, J. & Huang, G. H. A study on DEM-derived primary topographic attributes for hydrologic applications: sensitivity to elevation data resolution. Appl. Geogr. 28 (3), 210–223 (2008).

Mekonnen, E. N. et al. Geospatially-based land use/land cover dynamics detection, central Ethiopian rift Valley. GeoJournal 88(3), 3399–3417 (2023).

Peden, S. et al. Prediction of water content of eucalyptus leaves using 2.4 GHz radio wave. J. Electromagn. Anal. Appl. (2021).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the Deanship of Graduate Studies and Scientific Research, Taif University for funding this work.

Funding

This work is funded and supported by the Deanship of Graduate Studies and Scientific Research, Taif University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Awais Ali: Writing—original draft, formal analysis, and visualization; Muhammad Yousuf Jat Baloch: Supervision, methodology, conceptualization, and writing—review and editing; Muhammad Naveed: Data curation, formal analysis, and validation; Anam Nigar: Investigation, writing—original draft, and visualization; Abdulrahman Seraj Almalki: Conceptualization, methodology, and formal analysis; Ayesha Ghulam Rasool, and Meseret Abeje Gedfew: Methodology, investigation, data curation and review; Ahmed A. Arafat: Formal analysis, resources, Review and editing.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Conflict of interest

Authors stated that no conflict of Interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ali, A., Jat Baloch, M.Y., Naveed, M. et al. Advanced satellite-based remote sensing and data analytics for precision water resource management and agricultural optimization. Sci Rep 15, 27527 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-13167-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-13167-0

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Deep Learning and Remote Sensing for Crop Yield Prediction and Decision Support

Water Resources Management (2026)

-

The use of satellite images for limnological research in Poland

Acta Geophysica (2026)