Abstract

Breast lymphomas, though rare, present a unique spectrum of clinical and pathological characteristics. This multicenter retrospective study evaluates 92 cases from four international institutions over a ten-year period to provide a comprehensive analysis of primary breast lymphomas (PBLs), secondary breast lymphomas (SBLs), and related subtypes, including breast implant-associated lymphomas (BIA-ALCL) and intra-mammary lymph node lymphomas. Primary breast lymphomas accounted for 46.7% of cases, with a predominance of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL). Secondary breast involvement, observed in 43.5% of cases, displayed a more diverse histological distribution, with follicular lymphoma being the most common subtype. Breast implant-associated lymphomas (BIA-ALCL) constituted 6.5% of cases, exclusively involving anaplastic large cell T-cell lymphoma, ALK-negative. The study highlights significant differences in patient demographics, clinical presentation, and survival outcomes. PBLs primarily affected older patients (mean age: 68.4 years) and were associated with longer lymphoma-specific survival compared to SBLs (76.12 vs. 59.45 months; p = 0.001). Notably, survival differences were evident within histological subtypes, emphasizing the impact of disease origin on prognosis. BIA-ALCL cases were distinct in clinical features and histology, with a younger mean age (47.5 years) and frequent association with unilateral effusion. This analysis underscores the necessity for precise diagnostic and therapeutic strategies tailored to the unique biology of breast lymphomas. Future research should aim to elucidate molecular mechanisms and optimize management protocols to improve patient outcomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In the breast, carcinomas represent the most frequent malignant tumors1. Breast involvement by a lymphoma is very rare and can occur as a primary breast lymphoma (PBL) or as secondary breast lymphoma (SBL) i.e., secondary involvement of the breast by a lymphoma arisen in another primary location2. The standard definition of PBL was firstly provided by Wiseman and Liao in 1972 and required four criteria: (I) adequate histopathologic specimen, (II) presence of breast tissue and lymphoma infiltrates in close association, (III) no evidence of disseminated lymphoma at diagnosis, and (IV) no history of extra-mammary lymphoma3. Involvement of ipsilateral axillary lymph node(s) was allowed3. However, many studies have used less stringent criteria for the diagnosis of PBL, such as: (I) presentation with the dominant mass or symptom in the breast, and (II) no history of lymphoma, even if distant involvement is present on staging4,5. Special types are represented by lymphomas originating in breast implants (breast implant associated, BIA)6 and by lymphomas arising in intra-mammary lymph nodes7. Lymphomas infiltrating the breast that do not meet those criteria are classified as secondary breast lymphomas8,9.

PBLs account for < 0.5% of all malignant neoplasms of the breast and approximately 2% of all extra-nodal lymphomas10,11,12. In the USA, PBL incidence (per 1,000,000 women) increased from 0.66 (1975–1977) to 2.96 (2011–2013) with an annual percentage change (APC) of 5.3% from 1975 to 1999 and no statistically significant change thereafter13. More in detail, prevalence of PBL varies from 0.85 to 2.2% of all extra-nodal lymphomas, whereas secondary involvement of the breast by a lymphoma is more common, representing approximately 17% of all breast metastasis, which, in turn, represent only 0.5–6.6% of all breast malignancies2. It has been speculated, that the rarity of breast lymphoma may be due to the relatively low amount of lymphoid tissue within the breast14.

The pathogenesis of breast lymphomas remains incompletely understood. High post-menopausal estrogen levels15, chronic inflammation, autoimmune disease16, pregnancy and lactation17 have been proposed as possible risk factors, although the causes are still unclear. Interestingly, some PBL can occur together with a variety of breast cancers, although the pathophysiological significance of these coexistence is still unknown18.

PBL encompasses a variety of histological subtypes. More than 90% of reported cases originate from B-lymphocytes, with over half classified as diffuse large B-cell lymphomas (DLBCL). Less common B-cell subtypes include follicular lymphoma (FL), extra-nodal marginal zone lymphoma (EMZL), and Burkitt lymphoma (BL)19,20. The most common breast lymphoma of T-cell origin is anaplastic large cell lymphoma (ALCL), which has shown a rising prevalence over the past two decades21. Unlike other lymphomas, ALCL does not exclusively originate in the breast parenchyma but is typically found surrounding textured breast implants, where it is usually contained within a periprosthetic fibrous capsule13.

Indeed, breast implant-associated anaplastic large T-cell lymphoma (BIA- ALCL) is more common in this context, rather than when occurring in a breast without an implant (PB-ALCL)21,22. BIA-ALCL is a rare ALK-negative lymphoma associated with macrotextured breast implants, typically diagnosed 7–10 years post-implantation. It often presents as unilateral or bilateral breast swelling with discomfort, yellowish effusion fluid, and occasionally solid masses, detectable by imaging23,24,25,26,27. While early-stage cases have excellent survival rates, advanced stages with lymph node involvement or aggressive local invasion can lead to reduced survival and, in some cases, fatal outcomes27. The pathogenesis is still not very well understood21.

Lymphomas originating in intra-mammary lymph nodes are extremely rare, even though intra-mammary lymph nodes are observed in approximately 5% of mammographic cases28,29. Few isolated case reports have been documented in the literature7,30,31.

Finally, it is important to note that virtually any lymphoma can involve the breast parenchyma in advanced stages. In such cases, it is referred to as secondary breast lymphoma (SBL), which, like PBL, can present with nonspecific manifestations such as a breast mass or B symptoms and exhibit nonspecific imaging findings2.

Each histological subtype of lymphoma involving the breast appears to exhibit unique epidemiological patterns, prognoses, and treatment needs, underscoring the importance of precise diagnosis to ensure the timely initiation of the most suitable therapy32. This is particularly critical because PBL is often clinically and radiologically mistaken for breast carcinoma, as both conditions frequently present as a painless mass and share nonspecific imaging features33.

The rarity of these tumors poses challenges in accumulating large patient cohorts, thereby limiting the ability to perform extensive clinical trials and necessitating reliance on retrospective studies and case series for guiding management34.

To date, limited data are available on the incidence, clinical and radiological presentations, histopathology, and treatment outcomes of patients diagnosed with breast lymphomas. Most of the existing information on these entities originates from small case series35,36,37,38.

In this study, we aim to provide a comprehensive clinicopathological analysis of a multicenter, international cohort of patients with breast lymphoma over a ten-year period. Moreover, we assess the frequency of PBL, SBL, BIA and lymphoma originating from intra-mammary lymph nodes and evaluate the different histologic types, as well as review the clinical and radiological features among these different subgroups.

Materials and methods

We conducted a retrospective, multicenter study across four international academic medical institutions: the Department of Pathology and Molecular Pathology of the University Hospital of Zurich (Switzerland), the Department of Pathology and Molecular Pathology of the University Hospital of Linz (Austria), the Department of Pathology of the University of Utah, Salt Lake City (USA), and the Institute of Pathological Anatomy of the University Hospital of Udine (Italy). Data collection covered a 10-year period, from January 2014 to December 2024.

At each participating institution, a board-certified pathologist reviewed institutional pathology and clinical reports to extract comprehensive information on patients diagnosed with breast lymphomas.

The study was conducted in accordance to the declaration of Helsinki and adhered to ethical standards for retrospective research according to national regulation, with approval obtained from each one of the respective institutional review boards of the four centers adhering to the study.

Ethical committee approval details of every center involved:

-

Zurich: Kantonale Ethikkommission, Kanton Zürich, Switzerland; Approval number KEK-2012-553/PB2019/001111;

-

Salt Lake City, USA; Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the University of Utah Health; Approval number IRB_00077285.

-

Linz: Ethikkommission der Medizinischen Fakultät, Johannes Kepler Universität (JKU) Linz, Austria; Approval number 1003/2025;

-

Udine: internal review board of the Department of Medical Area (University of Udine), in accordance to the dictates of the general authorization to process personal data for scientific research purposes by the Italian Data Protection Authority. Approval number 037/2019_IRB.

All patients included in the study anonymously had given their consent for the use of anonymized data for research purposes. Individual informed consent was not required for this retrospective study with anonymized data in accordance with the respective national laws.

The following clinical and pathological data were collected from patient records: age at diagnosis, histological classification, distinction between PBL, SBL, or involvement of intra-mammary lymph nodes by lymphoma, clinical presentation and radiological findings. The distinction between PBL and SBL was determined based on clinical records. More in detail, a case has been classified as PBL if a newly diagnosed lymphoma presented with a predominant breast mass at the time of diagnosis in a patient without a history of lymphoma. In cases where staging information was incomplete (e.g., for patients referred from peripheral hospitals with limited clinical documentation), the distinction between primary and secondary breast lymphoma was made based on the classification provided by the referring physician in the clinical form submitted to the pathology department.

Where accessible, survival data, including survival status and overall survival in months, were recorded.

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize baseline characteristics, including mean age, the distribution of primary versus secondary lymphomas, and radiological features. Categorical variables were expressed as frequencies and percentages, while continuous variables were reported as means (± standard deviation) or medians with interquartile ranges, depending on the data distribution.

Comparative analyses were conducted as follows:

Age comparison between PBL and SBL was performed using the Mann-Whitney U test. This choice followed confirmation of non-normal distribution in both groups using the Shapiro-Wilk test (p = 0.021 for PBL; p < 0.001 for secondary involvement).

Breast involvement side (laterality) and lymphoma type (primary vs. secondary) were analyzed using the Chi-square test for categorical comparisons.

Histological subtypes and survival analysis: Kaplan-Meier survival analysis was employed to estimate lymphoma-specific survival curves, and log-rank tests were used to assess differences among histological subtypes.

All statistical analyses were conducted using Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS V29.0.1.1 (IBM Corp, Armonk, New York, URL: IBM SPSS Statistics). A p-value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant for all tests.

Results

A total of 92 cases meeting the inclusion criteria were identified. Of these, 43 cases (46.7%) were classified as PBL, 40 cases (43.5%) represented secondary involvement of the breast by a lymphoma originating from an extra-mammary site, 3 cases (3.3%) involved lymphomas of intra-mammary lymph nodes, and 6 cases (6.5%) were lymphomas associated with breast implants. The mean age at diagnosis was 64.2 years (range: 18–96; standard deviation: 16.2). Eight patients (8.7%) were male, and 84 (91.3%) were female.

The most common associated comorbidities identified in this cohort were arterial hypertension (20.7%), dyslipidemia and/or hypercholesterolemia (7.6%), and obesity (4.3%). Notably, 18 patients (19.6%) were diagnosed with at least one other malignancy. The most frequent malignancies included invasive breast carcinoma (10 cases, 10.9%) and non-melanoma skin cancer, such as basal cell carcinoma or squamous cell carcinoma (5 cases, 5.4%). Of note, one patient (1.1%) presented with three metachronous malignancies in addition to breast lymphoma: small cell lung carcinoma, multifocal cutaneous basal cell carcinoma, and invasive breast carcinoma. Survival data were available for 63 patients (68.5%). For detailed information on the study cohort, refer to Table 1.

There was a significant difference in the age at diagnosis between patients with PBL and SBL. Patients with PBL were significantly older than those with secondary breast involvement (p = 0.038). There was no statistically significant correlation between the site of presentation and the type of breast lymphoma (primary, secondary, or implant-associated; p = 0.32).

Primary breast lymphomas

PBLs were defined as cases in which the disease initially presented, and the dominant mass was located in the breast in patients without previous history of lymphoma. Mean age at diagnosis was 68.4 years. The most common histological subtypes were diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, NOS (DLBCL; 30 cases, 69.8%) and extra-nodal marginal zone lymphoma (EMZL; 8 cases, 18.6%). Most cases were identified as palpable breast masses reported by patients (38 cases, 88.4%), with a smaller number discovered incidentally during imaging for routine screening or follow-up (3 cases, 7.0%). In the radiology-based risk assessment, imaging findings were most commonly categorized as suspicious for malignancy (BI-RADS 4; 8 cases, 18.6%). In 3 cases (7.0%), lesions were classified as highly suggestive of malignancy, with two cases assigned a BI-RADS 5 score on sonography and one case on MRI.

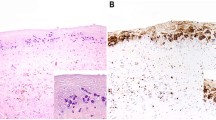

The mean lymphoma-specific survival time for primary DLBCL NOS was 42.55 months, for primary EMZL was 92.71 months, and for primary breast lymphomas overall was 76.12 months. For additional details on primary breast lymphomas, refer to Table 2. Representative histology images are shown in Fig. 1.

Histology of a representative case of primary breast diffuse large B-cell lymphoma NOS (DLBCL, NOS). The patient presented with a painless mass on palpation, sonographic classification was BIRADS 4. (A) H&E: Biopsy specimen shows a diffuse infiltration by atypical lymphocytes involving the breast glands. (B) At higher magnification, neoplastic cells demonstrate highly pleomorphic nuclei with nucleoli and increased mitotic activity. (C) Immunohistochemistry for CD20 shows intense membranous staining in the neoplastic cells, which were also positive for CD79a and PAX5 and negative for CD3, CD5, CD23 (not shown here). FISH for the MYC gene rearrangement was negative. (D) Ki67 demonstrates a high proliferation index of 80–90%.

Secondary breast lymphomas

Secondary breast lymphomas were defined as cases in which a new breast mass in a patient with a known history of lymphoma was histologically proven to represent the same lymphoma, or where the initial presentation or dominant mass was located outside the breast. Mean age at diagnosis was 61.9 years. The most common histological subtypes in this group were follicular lymphoma (15 cases, 37.5%) and EMZL (8 cases, 20.0%). Secondary breast involvement was often detected as a palpable breast mass reported by patients (14 cases, 35.0%) or as a metabolically active lesion identified during PET staging (6 cases, 15.0%). Sonography-based risk assessment, where available, included BIRADS-3 (1 case, 2.5%) and BIRADS-4 (3 cases, 7.5%).

The mean lymphoma-specific survival time for secondary breast involvement by follicular lymphoma was 84.6 months, and for secondary EMZL, it was 85.7 months. For further details on lymphomas with secondary involvement of the breast, refer to Table 3.

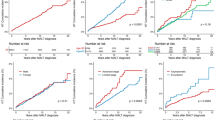

Comparison of lymphoma-specific survival

A statistically significant difference in lymphoma-specific survival was observed between patients with primary DLBCL NOS and those with secondary DLBCL NOS (42.55 vs. 27.33 months; Log-rank test p = 0.015), as well as between patients with primary EMZL and secondary EMZL (92.71 vs. 85.67 months; Log-rank test p = 0.039). Overall, patients with PBLs had significantly better lymphoma-specific survival compared to those with secondary breast involvement (76.12 vs. 59.45 months; Log-rank test p = 0.001). Kaplan-Meier survival curves for the most frequent breast lymphomas, as well as for all PBL combined and SBL combined, are presented in Fig. 2.

Breast-implant associated lymphomas

Mean age of presentation of patients with BIA- breast lymphomas was 47.5 The most common clinical presentation was fluid accumulation around the implant (unilateral effusion, classically referred as seroma) observed in 3 cases (50%). Other presentations included implant deformity (1 case, 16.7%) and implant rupture (1 case, 16.7%). Axillary lymphadenopathy was present in 2 cases (33.3%). All cases were histologically classified as anaplastic large cell T-cell lymphoma, ALK-negative (100%). For further details, refer to Table 4. Representative histology images are shown in Fig. 3.

Morphology of a cellblock of fluid accumulated around a breast implant in a patient with implant-associated anaplastic large cell lymphoma, ALK-negative. (A) H&E-stained section contains numerous atypical cells with eosinophilic cytoplasm and horseshoe-shaped nuclei, consistent with “hallmark cells”. (B) Immunohistochemistry for CD30 demonstrates a strong positivity (cytoplasmic and “Golgi-pattern” in all atypical cells C) Analysis of TCR demonstrates a monoclonal peak.

Lymphomas of intra-mammary lymph nodes

Mean age at diagnosis of patients with lymphoma of intra-mammary lymph nodes was 62.7 years (range: 54–69 years). Clinical presentations varied and included a palpable finding (1 case, 33.3%), and discovery during routine echography (1 case, 33.3%). Radiological risk assessment was available for two patients: one case was classified as BIRADS-2 (being suspicious for fibroadenoma), and another as BIRADS-4. Histologically, the lymphomas were classified as follicular lymphoma (2 cases, 66.7%) and lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma (1 case, 33.3%). For further details, refer to Table 5.

Discussion

In this study, we provide insights into the clinical and pathological characteristics of lymphomas involving the breast, emphasizing the diversity of their presentation and histological subtypes. To the best of our knowledge, this represents the largest multicentric cohort documented to date and the second-largest study worldwide on breast lymphomas, following the 2008 study by Talwalkar et al., which included 106 cases19.

We identified nearly equal proportions of PBLs (46.7%) and SBLs (43.5%). Notably, the relatively small proportion of BIA lymphomas (6.5%) and lymphomas of intra-mammary lymph nodes (3.3%) highlights the rarity of these entities. The predominance of female patients (91.4%) aligns with the female predilection seen in breast pathology, although eight male cases (8.6%) underscore the importance of considering breast lymphoma in this demographic as well. The mean age of diagnosis, 64.2 years, reflects a broad age range (18–96), emphasizing that breast lymphoma can occur in both younger and older populations.

Arterial hypertension emerged as the most common comorbidity in this cohort (20.7%), consistent with its prevalence in the general population of this age group39. Interestingly, 19.6% of patients were diagnosed with another malignancy, suggesting potential shared risk factors or heightened cancer surveillance among these individuals. Invasive breast carcinoma was the most frequently co-occurring malignancy, followed by non-melanoma skin cancers. The rare instance of a patient with three metachronous malignancies further illustrates the complexity of cancer predisposition in some individuals. However, further studies are needed to understand the role of potential risk factors and the biological and prognostic significance of cases of lymphoma associated with an additional malignant tumor. Only a few studies, in form of single case reports, have reported this association, whose significance remains to be further explored18,40,41,42,43.

The significant age difference between patients with PBL and SBL (p = 0.038) is an important finding, suggesting that primary disease tends to occur later in life. The predominance of DLBCL in PBL cases (69.8%) aligns with previous reports, while secondary lymphomas displayed a more varied histological distribution, with follicular lymphoma and EMZL being the most common subtypes. Our findings regarding the frequency of the various histological subtypes of PBLs are indeed consistent with those reported in the larger cohorts identified in the literature9,12,13,19,20.

The initial clinical presentation of PBL cases was predominantly seen as palpable breast masses (88.4%), while secondary lymphomas were often detected incidentally during imaging or staging. Radiologically, suspicious findings (BI-RADS 4 or 5) were observed in available PBL cases, reflecting a high likelihood of malignancy. However, given the overlap in imaging characteristics between breast lymphomas, triple-negative breast cancers, and certain benign lesions such as fibroadenomas44, imaging findings alone may be non-specific. Furthermore, radiological data were available for only a subset of patients, limiting definitive conclusions.

Survival outcomes demonstrated significant differences between primary and secondary breast lymphomas, with PBL cases showing longer lymphoma-specific survival (76.12 vs. 59.45 months, p = 0.001). Within specific histological subtypes, primary DLBCL NOS and EMZL had better lymphoma-specific survival outcomes compared to their secondary counterparts. However, these data should be interpreted with caution, as the presence of lymphoma with secondary involvement of the breast inherently indicates an advanced stage and, consequently, a poorer prognosis. Moreover, the cohort analyzed in this study is too small and contains incomplete survival, therapeutical and staging data, making impossible to compare the survival of PBL with that of lymphomas secondarily involving the breast while controlling for stage and histological subtype. This represents a major limitation of our study and highlights the need for larger studies and meta-analyses.

BIA lymphomas were distinct in their presentation and histology. All cases were ALCL, ALK-negative, consistent with the known association between breast implants and this rare lymphoma subtype. The relatively younger mean age at diagnosis (47.5 years) and clinical presentation with fluid accumulation (50%) further distinguish this group from other breast lymphomas.

An interesting finding in our cohort is that the mean survival of BIA-ALCL cases was 36.4 months (see Fig. 2), which is significantly lower than the average reported in the literature. Previous studies indicate a generally favorable prognosis, with a median survival of 12 years24. This discrepancy can be explained in several ways. First, with only five cases, it is not possible to draw broad conclusions, and this represents a major limitation of our study. Moreover, although data on tumor stage are not available, it is important to consider that patients treated and evaluated in academic centers may represent more advanced or complex cases, potentially with multiple comorbidities. Additionally, variability in survival among BIA-ALCL cases has been documented in the literature, as shown in a recent meta-analysis45. Therefore, we believe that further studies with larger sample sizes are necessary to make more reliable statements about survival outcomes in patients with BIA-ALCL.

The rare cases of intra-mammary lymph node lymphomas presented unique diagnostic challenges. The varied clinical presentations, from palpable masses to incidental findings on imaging, underscore the need for a high index of suspicion. Histologically, follicular lymphoma was the most common subtype in this group.

This study highlights the heterogeneity of breast lymphomas in terms of clinical presentation, histology, and prognosis. The findings underscore the importance of thorough diagnostic evaluation, including histological and radiological assessment, to guide accurate classification and management.

The main strength of this study lies in the relatively large cohort size for these uncommon entities, its multicentric and international nature, as well as its holistic approach, encompassing a comprehensive description of histopathological, clinical, and lymphoma-specific survival characteristics. The primary limitation is the fragmentary nature of the clinical and radiological information, which was not available for all patients with histological examinations. This limitation arises from the fact that many patients included in the study were not entirely followed through the whole onco-hematological process from diagnosis to therapy and follow-up at the reference centers where the histopathological examination was performed.

Future research should aim to further elucidate the biological and molecular mechanisms underlying these differences to improve outcomes for patients with breast lymphomas. Additionally, the relatively high frequency of co-existing malignancies in this cohort suggests the potential benefit of comprehensive cancer surveillance in patients diagnosed with breast lymphoma.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Arnold, M. et al. Current and future burden of breast cancer: global statistics for 2020 and 2040. Breast 66, 15–23 (2022).

Surov, A. et al. Primary and secondary breast lymphoma: prevalence, clinical signs and radiological features. Br. J. Radiol. 85 (1014), e195–205 (2012).

Wiseman, C. & Liao, K. T. Primary lymphoma of the breast. Cancer 29 (6), 1705–1712 (1972).

Hugh, J. C., Jackson, F. I., Hanson, J. & Poppema, S. Primary breast lymphoma. An immunohistologic study of 20 new cases. Cancer 66 (12), 2602–2611 (1990).

Brustein, S., Filippa, D. A., Kimmel, M., Lieberman, P. H. & Rosen, P. P. Malignant lymphoma of the breast. A study of 53 patients. Ann. Surg. 205 (2), 144–150 (1987).

Julien, L. A., Michel, R. P. & Auger, M. Breast implant-associated anaplastic large cell lymphoma and effusions: A review with emphasis on the role of cytopathology. Cancer Cytopathol. 128 (7), 440–451 (2020).

Venizelos, I. D., Tatsiou, Z. A., Vakalopoulou, S., Mandala, E. & Garipidou, V. Primary non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma arising in an intramammary lymph node. Leuk. Lymphoma. 46 (3), 451–455 (2005).

Raj, S. D. et al. Primary and secondary breast lymphoma: clinical, pathologic, and multimodality imaging review. Radiographics 39 (3), 610–625 (2019).

Domchek, S. M., Hecht, J. L., Fleming, M. D., Pinkus, G. S. & Canellos, G. P. Lymphomas of the breast: primary and secondary involvement. Cancer 94 (1), 6–13 (2002).

Sabate, J. M. et al. Lymphoma of the breast: clinical and radiologic features with pathologic correlation in 28 patients. Breast J. 8 (5), 294–304 (2002).

Freeman, C., Berg, J. W. & Cutler, S. J. Occurrence and prognosis of extranodal lymphomas. Cancer 29 (1), 252–260 (1972).

Bobrow, L. G. et al. Breast lymphomas: a clinicopathologic review. Hum. Pathol. 24 (3), 274–278 (1993).

Thomas, A., Link, B. K., Altekruse, S., Romitti, P. A. & Schroeder, M. C. Primary breast lymphoma in the united states: 1975–2013. J Natl. Cancer Inst 109(6). (2017).

Ha, K. Y., Wang, J. C. & Gill, J. I. Lymphoma in the breast. Proc. (Bayl Univ. Med. Cent). 26 (2), 146–148 (2013).

Teras, L. R., Patel, A. V., Hildebrand, J. S. & Gapstur, S. M. Postmenopausal unopposed Estrogen and Estrogen plus progestin use and risk of non-Hodgkin lymphoma in the American cancer society cancer prevention Study-II cohort. Leuk. Lymphoma. 54 (4), 720–725 (2013).

Shen, F., Li, G., Jiang, H., Zhao, S. & Qi, F. Primary breast diffuse large B-cell lymphoma in a patient with systemic lupus erythematosus: A case report and review of the literature. Med. (Baltim). 99 (33), e21736 (2020).

Yin, Y., Ye, M., Chen, L. & Chen, H. Giant primary breast diffuse large B-cell lymphoma during pregnancy and lactation. Breast J. 25 (5), 996–997 (2019).

Mirkheshti, N. & Mohebtash, M. A rare case of bilateral breast lobular carcinoma coexisting with primary breast follicular lymphoma. J. Community Hosp. Intern. Med. Perspect. 9 (2), 155–158 (2019).

Talwalkar, S. S. et al. Lymphomas involving the breast: a study of 106 cases comparing localized and disseminated neoplasms. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 32 (9), 1299–1309 (2008).

Shao, Y. B., Sun, X. F., He, Y. N., Liu, C. J. & Liu, H. Clinicopathological features of Thirty patients with primary breast lymphoma and review of the literature. Med. Oncol. 32 (2), 448 (2015).

James, E. R., Miranda, R. N. & Turner, S. D. Primary lymphomas of the breast: A review. JPRAS Open. 32, 127–143 (2022).

Bergsten, T. M. et al. Non-implant associated primary cutaneous anaplastic large cell lymphoma of the breast. J. Surg. Case Rep. 2019 (5), rjz139 (2019).

Loch-Wilkinson, A. et al. Breast Implant-Associated anaplastic large cell lymphoma in Australia and new zealand: High-Surface-Area textured implants are associated with increased risk. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 140 (4), 645–654 (2017).

Miranda, R. N. et al. Breast implant-associated anaplastic large-cell lymphoma: long-term follow-up of 60 patients. J. Clin. Oncol. 32 (2), 114–120 (2014).

Mehta-Shah, N., Clemens, M. W. & Horwitz, S. M. How I treat breast implant-associated anaplastic large cell lymphoma. Blood 132 (18), 1889–1898 (2018).

Ferrufino-Schmidt, M. C. et al. Clinicopathologic features and prognostic impact of lymph node involvement in patients with breast Implant-associated anaplastic large cell lymphoma. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 42 (3), 293–305 (2018).

Marques-Piubelli, M. L., Medeiros, L. J., Stewart, J. & Miranda, R. N. Breast Implant-Associated anaplastic large cell lymphoma: updates in diagnosis and specimen handling. Surg. Pathol. Clin. 16 (2), 347–360 (2023).

Bitencourt, A. G. et al. Intramammary lymph nodes: normal and abnormal multimodality imaging features. Br. J. Radiol. 92 (1103), 20190517 (2019).

Meyer, J. E., Ferraro, F. A., Frenna, T. H., DiPiro, P. J. & Denison, C. M. Mammographic appearance of normal intramammary lymph nodes in an atypical location. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 161 (4), 779–780 (1993).

Caimi, F., Menozzi, C. & Freschi, M. [Intramammary lymph node localization of malignant non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Description of a case]. Radiol. Med. 78 (3), 266–268 (1989).

Zack, J. R., Trevisan, S. G. & Gupta, M. Primary breast lymphoma originating in a benign intramammary lymph node. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 177 (1), 177–178 (2001).

Hu, S. et al. Primary breast diffuse large B-cell lymphoma in the rituximab era: therapeutic strategies and patterns of failure. Cancer Sci. 109 (12), 3943–3952 (2018).

Uenaka, N. et al. Primary breast lymphoma initially diagnosed as invasive ductal carcinoma: A case report. Clin. Case Rep. 9 (6), e04189 (2021).

Yhim, H. Y. et al. First-Line treatment for primary breast diffuse large B-Cell lymphoma using immunochemotherapy and central nervous system prophylaxis: A multicenter phase 2 trial. Cancers (Basel) 12(8). (2020).

Sakhri, S. et al. Primary breast lymphoma: a case series and review of the literature. J. Med. Case Rep. 17 (1), 290 (2023).

Shahid, N., Abbi, K. K., Hameed, K. & Mohamed, I. Indolent breast lymphomas: A case series and review of literature. World J. Oncol. 4 (3), 173–175 (2013).

Wadhwa, A. & Senebouttarath, K. Primary lymphoma of the breast: A case series. Radiol. Case Rep. 13 (4), 815–821 (2018).

Al Battah, A. H. et al. Diffuse large B-Cell breast lymphoma: A case series. Clin. Med. Insights Blood Disord. 10, 1179545X17725034 (2017).

Lacruz, M. E. et al. Prevalence and incidence of hypertension in the general adult population: results of the CARLA-Cohort study. Med. (Baltim). 94 (22), e952 (2015).

Tamaoki, M. et al. A rare case of non-invasive ductal carcinoma of the breast coexisting with follicular lymphoma: A case report with a review of the literature. Oncol. Lett. 7 (4), 1001–1006 (2014).

Woo, E. J., Baugh, A. D. & Ching, K. Synchronous presentation of invasive ductal carcinoma and mantle cell lymphoma: a diagnostic challenge in menopausal patients. J Surg. Case Rep 2016(1) (2016)

Liu, W., Zhu, H. & Zhou, X. Synchronous bilateral non-Hodgkin’s diffuse large B-cell lymphoma of the breast and left breast invasive ductal carcinoma: a case report and review of literature. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Pathol. 7 (10), 7042–7048 (2014).

Ho, C. W., Mantoo, S., Lim, C. H. & Wong, C. Y. Synchronous invasive ductal carcinoma and intravascular large B-cell lymphoma of the breast: a case report and review of the literature. World J. Surg. Oncol. 12, 88 (2014).

Clauser, P., Bazzocchi, M., Marcon, M., Londero, V. & Zuiani, C. Results of Short-Term Follow-Up in BI-RADS 3 and 4a breast lesions with a histological diagnosis of fibroadenoma at percutaneous needle biopsy. Breast Care (Basel). 12 (4), 238–242 (2017).

Sharma, K., Gilmour, A., Jones, G., O’Donoghue, J. M. & Clemens, M. W. A systematic review of outcomes following breast Implant-Associated anaplastic large cell lymphoma (BIA-ALCL). JPRAS Open. 34, 178–188 (2022).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the Department of Medical Oncology and Hematology of the University Hospital Zurich, Switzerland, for the excellent interdisciplinary cooperation.

Funding

As the study involved only the analysis of existing clinical and pathological data and no additional tissue-based investigations were performed, no funding was required.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

U.M. and Z.V. designed the study. U.M. wrote the main manuscript and text. U.M., A.R., C.G., N.F. and M.O. collected clinical and pathological data. All authors contributed to study design, conception, interpretation of clinical and pathological data and reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Approval from the institutional review board of each participating institution was obtained (see Materials and Methods).

Individual informed consent was not required for this retrospective study with anonymized data, in accordance with the respective national laws (Swiss Human Research Act HRA, Art. 34; Austrian Research Organization Act (Forschungsorganisationsgesetz–FOG § 2 d); Italian Data Protection Authority (Legislative Decree no. 196/2003, as amended by Legislative Decree 101/2018), and in accordance with EU GDPR (Art. 9); U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) regulations, 45 CFR 46.104(d)(4).

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Maccio, U., Rets, A., Grosse, C. et al. Clinical and pathological features of lymphomas in the breast: a comprehensive multicentric study. Sci Rep 15, 29032 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-13214-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-13214-w