Abstract

Gaining insight into the mechanisms of zoonotic disease transmission in both animal and human populations is essential for implementing effective measures to control the disease spread and mitigate its impact. This paper employs an evolutionary game theory framework to analyze the intricate dynamics of Monkeypox (mpox) epidemics across diverse networks, including scale-free and random regular networks with four network settings (BA-BA, ER-ER, BA-ER, and ER-BA) in both humans and animals. We investigate how individual behaviors and interactions influence the spread of diseases in different populations by combining network structures with evolutionary game dynamics. The results of our research reveal complex patterns, including the emergence of super-spreaders who transmit the disease to numerous others and the impact of the network structure on the disease’s persistence and transmission. Furthermore, we demonstrate the practicality of this method in clarifying crucial elements that drive the spatial and temporal expansion of mpox, providing a valuable understanding of the efficacy of focused intervention strategies. Our work emphasizes the importance of multidisciplinary approaches in understanding the complex dynamics of infectious diseases and informing public health responses.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Mpox, a disease transmitted between animals and humans, has become a significant public health concern due to its rapid spread in both animal and human populations. Two epidemics in monkey populations that resembled mpox primarily led to its initial identification in 19581. Since January 2022, the World Health Organization (WHO) has received reports of mpox epidemics from many countries. As of June 15, 2022, there had been 2103 confirmed cases with laboratory evidence and one death1,2. Recently, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared the mpox virus a public health emergency of international concern, as it has expanded to areas outside its usual zones, raising concerns about its potential to spread further and the need for effective public health measures3. Therefore, gaining insight into the intricacies of mpox transmission throughout diverse networks of hosts is vital for implementing efficient disease control and preventive measures.

A significant number of deterministic studies have been carried out to demonstrate the utility of mathematical and computational modeling in understanding the intricate dynamics of mpox. Among these studies, Bankuru et al.4 proposed that mpox is controllable and might be eradicated with vaccination in a scenario characterized by a semi-endemic equilibrium in their model. Nevertheless, vaccination alone cannot eliminate mpox in a population already in an endemic state. Idisi et al.5 proposed a novel compartmentalized mathematical model to investigate the influence of heightened awareness on managing and reducing mpox illness. The model presented in6 was combined with numerical simulations, which conclusively showed that the planned actions successfully eliminated sick individuals from both human and monkey populations during the study period. Allehiany et al.7 provided a mathematical model for analyzing the monkeypox illness within the context of the documented cases of the mpox epidemic in the US. Riaz8 and Focosi et al.9 thoroughly investigated mpox, including its outbreak and medical manifestation, epidemiology, pathological development, vaccinations, and treatments for the human mpox virus. Elsonbaty et al.10 provided an innovative model that accurately replicates the transmission of the monkeypox virus, incorporating the impact of interactions between human and rodent populations, as well as previously unaccounted factors such as poor immunization and nonlinear incidence rates. Ola11 stated that, unlike the transmission of the monkeypox virus, spectral illnesses have symptoms similar to mpox. Peter et al.12 conducted a cost-effectiveness study to inform the public about the most cost-effective method among various combinations of disease control measures. They recommended implementing preventive strategies for transmission from rodents to humans as the most economical and effective strategy compared to other competing methods. Maruotti et al.13 forecasted the number of illnesses that went unnoticed during the mpox epidemic. Damon14 analyzed the mpox virus and its appearance in human cultures. According to Islam et al.15, the mpox outbreaks may be stopped without fear and shame. Instead, disease awareness and preventive activities are sufficient to prevent the spread of mpox. Peter et al.16 and Qurashi et al.17 argued that segregating persons with illnesses from the general population is advantageous in mitigating the spread of the disease. However, the indisputable fact is that conventional epidemiological models mentioned above often fail to incorporate the intricacies of host relationships and behavioral dynamics that influence the transmission of diseases. This paper employs the framework of evolutionary game theory and network science to elucidate the intricate dynamics of mpox epidemics in both animal and human populations. Our goal is to understand how the structure of heterogeneous contact networks, namely, Barabási-Albert (BA) scale-free and Erdős–Rényi (ER) random regular heterogeneous networks, affects the transmission dynamics and changes the evolutionary strategies of hosts in response to epidemics in four different network settings: BA-BA, ER-ER, BA-ER, and ER-BA in human and animal populations.

Evolutionary game theory (EGT) is a valuable tool for analyzing the transmission dynamics of infectious diseases18,19,20,21. It achieves this by examining the strategic interactions between various types of hosts (such as vulnerable, infected, or recovered) within a population. This methodology enables us to simulate not only the direct spread of the virus but also the deliberate choices made by individuals, such as vaccination22,23,24,25, the practice of non-pharmaceutical interventions26,27, and seeking medical care28. Within the framework of evolutionary game theory, people’s perceptions of self-protective actions can effectively mitigate the spread of infectious diseases in social dilemma scenarios29,30,31. Glaubitz and Fu32 demonstrate that adherence to each non-pharmaceutical intervention (NPI) can be markedly dynamic and context-dependent during an active epidemic, as individuals may favor one measure over another or opt for inaction, resulting in complex temporal fluctuations in NPI adoption. Fu et al.33 propose an evolutionary game-theoretic framework to address attaining extensive immunity, examining the influence of individual imitation behavior and population structure on vaccination. Chen and Fu34 investigate how the dynamics of social imitation in vaccination are influenced by an imperfect vaccine that provides only partial protection against the illness to comprehend the perplexing issues surrounding vaccine compliance. In addition, most epidemic models based on EGT consider the intrinsic costs, rewards, and risks associated with infection to determine the most appropriate intervention options35,36. Using the EGT framework, Augsburger et al.4,37 argued that voluntary vaccination can not effectively halt the monkeypox epidemic. Ullah and Kabir38 asserted that implementing rigorous quarantine procedures and safeguarding both people and animals were effective in reducing the occurrence of disease outbreaks. These efforts not only significantly reduced the spread of the illness but also deferred the peak of the epidemic. However, no studies have been conducted on combining pharmaceutical interventions, namely, vaccination and treatment strategies, with EGT settings and heterogeneous network mechanisms. For the first time, by utilizing heterogeneous network science principles, such as scale-free and random regular networks, we can effectively analyze the various patterns of host connectivity and the diversity in host behavior, which is crucial for comprehending the disease system’s resilience and identifying potential intervention strategies.

Networks in tangible occurrences interconnect populations from various civilizations or groups, as the world encompasses a wide range of social interactions. Nodes represent individual entities within social networks, while edges depict the relationships or linkages between entities. Due to the non-uniformity of network structures, the transmission of infections on networks varies significantly across different groups. When a disease spreads across physical networks, the transmission dynamics exhibit various physical characteristics, including variable infection rates, degrees of closeness, and the frequency of contacts. Models can be categorized into distinct types of dynamic networks, such as regular networks, random networks, and scale-free networks, depending on their network structures. Considering these characteristics, Barnes39 established social networks in an anthropological study that examined the social dimensions of relationships between central nodes in a network in 1954. In 1985, Klovdahl40 used social network analysis (SNA) for the first application in epidemiological models. Then, in the same context, many researchers have studied how epidemic diseases spread in physical networks, specifically Barabasi-Albert scale-free (BA-SF) networks41,42,43,44,45. BA-SF networks, characterized by power-law distributions, represent the reported number of heterosexual partners in various populations46,47,48. Wang et al.49 examined the dynamics of an epidemic-spreading model with drug-resistant variation on scale-free networks. Ullah et al.50 proposed a new method to tackle urgent and unforeseen problems by developing a modified epidemic model that focuses on vaccination and lockdown measures, considering the global pervasiveness of a highly transmissible respiratory disease across diverse networks. Kabir et al.51 investigated the unaware-aware (UA) epidemic model in heterogeneous networks to examine how disseminating knowledge within the spatial structure of the vaccination game influences epidemic dynamics. Kuga and Tanimoto52 investigated a mathematical model of the vaccination game that incorporates spatial structure and the distribution of connections among people in BA-SF and Erdős-Rényi (ER) random complex networks. Meng et al.53 developed an evolutionary game model to examine the disparity between mandated and voluntary vaccination methods on heterogeneous networks. Hota and Sundaram54 investigated decentralized protection solutions for controlling susceptible-infected-susceptible outbreaks on networks, examining a population game model in which nodes decide whether to vaccinate themselves. Fukuda et al.55 employed a framework based on evolutionary game theory with social networks to investigate the social issue of risk assessment in epidemiology and the decision to be vaccinated.

Analysis of four network settings, BA-BA, ER-ER, BA-ER, and ER-BA, is crucial to understanding the mpox disease transmission mechanism in human and animal populations. The Barabási-Albert (BA) scale-free model in human networks can elucidate the rapid dissemination of mpox inside densely populated or highly interacting groups, which is crucial for formulating successful public health measures and for rodent populations can illustrate the possibility for disease survival and dissemination in natural reservoirs, where some species exhibit a higher frequency of contact within their population, thereby affecting zoonotic transmission to humans.

Examining mpox infectious diseases reveals that comparing Erdős-Rényi (ER) random networks between humans and rodents offers insights into the differential transmission of the disease between species with unique interaction patterns. Understanding the networks of mpox, which infect both people and animals, particularly rats, as reservoirs, is essential. In a random network of people, links represent social or physical interactions that facilitate the transmission of information. In rodents, connections indicate interactions such as nesting, grooming, or foraging, which vary in frequency and intensity. Analyzing mpox dissemination within these Erdős-Rényi (ER) random networks helps identify possible species-specific transmission hazards and control measures. This comparison enables researchers to predict cross-species spillover occurrences and formulate targeted strategies for both human and rodent populations to mitigate mpox epidemics.

The Barabási-Albert (BA) scale-free and the Erdős-Rényi (ER) random network models are essential frameworks for analyzing the transmission dynamics of diseases, especially in the context of human and rodent hosts. In the case of mpox, a zoonotic disease, these network models elucidate the disparities in connection and transmission potential across species. A Barabási-Albert (BA) scale-free network, often used to model human social systems, is distinguished by a limited number of highly linked nodes (hubs) and many nodes with fewer connections. This framework illustrates scenarios such as metropolitan areas, healthcare facilities, or digital communities, where specific individuals or organizations act as super-spreaders during an epidemic. Nonetheless, the Barabási-Albert (BA) scale-free network also pertains to particular rodent species, especially social ones such as rats, which establish organized hierarchies of dominating individuals within their colonies.

In contrast, the Erdős-Rényi (ER) random network posits a more uniform distribution of connections. It has been employed to model sparsely connected human populations (e.g., rural or low-density communities) and solitary or weakly social rodents, such as mice, whose interactions are more random and diffuse. Our analysis examines all combinations of both networks for human and rodent populations, encompassing the spectrum of potential structural connections and evaluating the impact of discrepancies in contact topology on cross-species disease dynamics. Analyzing mpox transmission on Barabási-Albert (BA) scale-free and Erdős-Rényi (ER) random networks enables researchers to model and forecast the disease’s dynamics in humans and rodents, providing insights into species-specific control strategies. Specifically, targeting high-connectivity hubs can prove more effective in human populations. In contrast, broader measures can be necessary for rodent populations. This differentiation is crucial for developing treatments that prevent cross-species transmission and effectively control epidemics in each host category.

The Erdos–Renyi (ER) random network model, often used to depict human social interactions, posits that any pair of persons has an equal likelihood of being interconnected, which replicates the transmission of illnesses across extensive, diverse human groups whose linkages are mostly arbitrary. The Barabási-Albert (BA) scale-free network model, often employed to depict social structures in rodent populations, incorporates highly connected “hubs” or nodes with numerous connections, thereby facilitating the comprehension of transmission in populations characterized by uneven connectivity, such as rodent colonies. For mpox, which transmits between humans and rodents, employing both Erdos–Renyi (ER) random and Barabási-Albert (BA) scale-free network models is essential: the Erdos–Renyi (ER) random network model elucidates the potential for swift, unpredictable outbreaks in human populations, whereas the Barabási-Albert (BA) scale-free network model clarifies the persistence and dissemination of the disease within and among rodent communities. This dual-network methodology enables researchers to enhance their comprehension and forecasting of the zoonotic transmission routes of mpox, facilitating effective monitoring and control measures across species.

This sophisticated methodology can help policymakers understand the intricate dynamics of mpox epidemics in animals and humans, combining evolutionary game theory with scale-free and random regular heterogeneous networks (four network settings: BA-BA, ER-ER, BA-ER, and ER-BA) in both humans and animals. The evolutionary game theoretical modeling technique accurately captures the adaptive behaviors of both the infection and the hosts, which enables a more realistic depiction of the dynamic interaction between the virus and the population. Meanwhile, incorporating scale-free and random regular heterogeneous networks enhances the model’s accuracy by considering the diversity in contact patterns and community transmission paths. This paradigm enables policymakers to investigate how the structure of a network influences the transmission of mpox, how changes in behavior can impact the course of the epidemic, and the effectiveness of control measures.

In the present study, we propose a new network model, referred to as \({S}^{h}{V}^{h}{E}^{h}{I}^{h}{T}^{h}{R}^{h}{S}^{r}{E}^{r}{I}^{r}\), which incorporates the evolutionary game theory in different types of heterogeneous networks to investigate the transmission dynamics of mpox involving both human and animal hosts. Recent data have indicated that rodents (such as squirrels and rats) are among the most common animals that harbor the mpox virus. Hence, we will consider human and rodent populations in our model.

Epidemic model on heterogeneous networks

Degree distribution

In order to examine the effect of a diverse population network on the spread of mpox epidemics in a vaccination and treatment game, we use the \({S}^{h}{V}^{h}{E}^{h}{I}^{h}{T}^{h}{R}^{h}{S}^{r}{E}^{r}{I}^{r}\) model on a network with general connectivity \(P(k)\) and a finite average degree value of \(\langle k\rangle =\sum kP(k)\). We will test different values of \(\langle k\rangle\) in our numerical simulation. Within a network, each network link symbolizes the interconnections between two people. Two distinct and widely recognized spatial structures are examined: the Poisson degree distribution and the power law degree distribution. These structures are associated with the Erdős-Rényi (ER) random56 and the Barabasi-Albert (BA) scale-free57 networks, respectively. The Poisson degree distribution, denoted by \(P(k)\), is defined as \(P\left(k\right)=\frac{exp\left(-\langle k\rangle \right){<k>}^{k}}{k!}\). On the other hand, the power law degree distribution is represented as \(P(k)\sim {k}^{-\gamma }(2<\gamma <3)\).

Network model

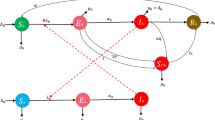

In the construction of infectious disease compartment models, individuals are often categorized into susceptible \((S)\), exposed \((E)\), infected \((I)\), and recovered \((R)\) groups. Classical infectious disease models encompass several architectures, including the SIR, SIS, and SEIR models. Current work is SEIR-based \({S}^{h}{V}^{h}{E}^{h}{I}^{h}{T}^{h}{R}^{h}{S}^{r}{E}^{r}{I}^{r}\) model for defining the mpox epidemic in heterogeneous network settings, individuals in the human population \({N}^{h}(t)\) are categorized as susceptible \(({S}_{k}^{h}(t))\), vaccinated \(({V}_{k}^{h}(t))\), exposed \(({E}_{k}^{h}(t))\), infected \(({I}_{k}^{h}(t))\), treated \(({T}_{k}^{h}(t))\), and recovered \(({R}_{k}^{h}(t))\), and the density of rodent populations \({N}^{r}(t)\) are categorized as susceptible \(({S}_{k}^{r}(t))\), exposed \(({E}_{k}^{r}(t))\), and infected \(({I}_{k}^{r}(t))\), with degree \(k\) in the network at the time \(t\) (Fig. 1). Thus, the mpox heterogeneous network epidemic model is described as follows:

If a link connects to a site of degree \(k\), and the probability that it does so is proportional to the degree of distribution \(kP\left( k \right)\)58,59 for uncorrelated complex degree networks, then \({\Theta }_{\text{h}}\left(t\right)\) and \({\Theta }_{\text{r}}\left(t\right)\) are represented as

where \(P(k) > 0,\) the degree distribution of the network satisfies the normalized equality \(\sum_{k=1}^{n}P\left(k\right)=1,\) \(<k>=\sum_{k=1}^{n}kP\left(k\right)\) symbolizes the average degree of the network and \(<{k}^{2}>=\sum_{k=1}^{n}{k}^{2}P\left(k\right)\) symbolizes the second moment. The likelihood that any edge of the network contains the infected person is equivalent to the ratio of the number of edges linked to infected people to the total number of edges in the network.

Susceptible persons are at risk of becoming infected, and people enter the susceptible compartment at a rate \({\Lambda }_{h}\). Susceptible people participate in vaccination programs at the rate \(x\) and become vaccinated, with the vaccine efficacy rate \(1-\eta\). Susceptible individuals contact infected humans at a rate \({\beta }_{hh}\) or infected rodents at the rate \({\beta }_{rh}\) and enter the exposed compartment. After the incubation period \({\alpha }_{h}\), exposed people become infected (and infectious). Infected humans enter the treatment and recovered classes at the rates \({\gamma }_{h}\) and \(\tau ,\) respectively. Treated individuals recover at the rate \(\delta\) and enter the recovered class. \({\mu }_{h}\) and \({\mu }_{r}\) are the natural death rates of human and rodent hosts, respectively. At the rate \({\Lambda }_{r}\) rodents enter the susceptible rodent class and come in touch with infected humans at the rate \({\beta }_{hr}\) or infected rodents at the rate \({\beta }_{rr}\) and become exposed. After the incubation period \({\alpha }_{r}\), exposed rodents become infected and subsequently recover at the rate \({\gamma }_{r}\). The symbol \(\sigma\) represents the likelihood of transmission from humans to animals. If \(\sigma =0\), there is no possibility of transmission from a human to a rodent. Additionally, \(\left(1-{p}_{h}\right)\) and \(\left(1-{p}_{r}\right)\) represents the awareness or protection levels from infected humans and rodents, respectively. More details are listed in Table 1.

Behavioral dynamics

Behavioral dynamics significantly influence the propagation and control of an mpox epidemic. The response of individuals and groups at risk of infection, including their compliance with preventive measures such as vaccination, social distancing, hygiene practices, as well as personal awareness and protection, and treatment, directly influences the course of the epidemic. For successful intervention in mpox, it is crucial to understand the elements that impact human behavior, such as risk perception, cultural norms, and faith in public health discourse. The dissemination of false or misleading information and the negative perception of mpox may impede the effectiveness of outbreak control measures, as it can result in resistance towards vaccination and other preventive actions. Hence, public health policies need to focus not only on the treatment dimensions of the condition but also on the psychological and social elements that impact behavior, which entails ensuring that communication is unambiguous, culturally attuned, and fosters trust among affected communities. Therefore, we propose the concept of behavioral game dynamics in the context of evolutionary game theory60,61,62. This concept will focus on two parameters from our model, which are now both regarded as time-dependent: (1) the changing rate at which individuals transition from being susceptible \(({S}_{k}^{h}(t))\) to vaccinated \(({V}_{k}^{h}(t))\), denoted as \(x(t)\); and (2) the changing rate at which infected humans \(({I}_{k}^{h}(t))\) get treatment \(({T}_{k}^{h}(t))\), denoted by \(\tau (t)\). The term “individual control” describes this pace that changes over time. The subsequent behavioral dynamical equations of vaccination and treatment are defined in the following manner:

Here, \(m\) is the individual’s effort rate and \({C}_{V},{C}_{T} \text{and} {C}_{I}(=1)\) are the costs of vaccination, treatment, and disease, respectively, where \(0\le {C}_{V}\le 1, 0\le {C}_{T}\le 1.\) A person’s situation throughout an epidemic determines their expenses and affects their final social payoff, determining whether they gain or lose.

The expression in Eq. (12), \(\left(-{C}_{V}{\sum }_{k}{V}_{k}^{h}+{\sum }_{k}{I}_{k}^{h}\right)\) is intended to represent an individual’s risk trade-off while deciding between cooperation and defection. The sign of this expression (positive or negative) determines whether vaccination is chosen. When the cost of vaccination increases, the related term (\(-{C}_{V}{\sum }_{k}{V}_{k}^{h}\)) is adversely affected. In addition, if a select number of affluent individuals decide against vaccination, it would have a detrimental effect, leading to free riding and impeding the attainment of herd immunity. Conversely, if the likelihood of individuals becoming sick increases due to variables such as a large proportion of infected individuals, the outcome would be favorable, resulting in an upsurge in the vaccination rate.

In Eq. (13), the term \(\left(-{C}_{T}{\sum }_{k}{T}_{k}^{h}+{\sum }_{k}{I}_{k}^{h}+\omega \left(\frac{1}{{\gamma }_{h}}-\frac{1}{\delta }\right)+{T}_{a}\right)\) represents the trade-off between the benefits and costs of treatment options, where \({T}_{a}\) is the availability of treatment resources. It illustrates the extent to which receiving treatment is more advantageous than not receiving treatment in terms of the duration of the condition. Increasing the accelerated recovery rate \(\delta\) relative to the standard recovery rate \(\gamma\) allows patients to experience quick recovery from the disease. Specifically, \(\frac{1}{\delta }\) denotes the mean recovery duration while receiving treatment, whereas \(\frac{1}{\gamma }\) indicates the mean recovery duration without assistance. If the difference between \(\frac{1}{{\gamma }_{h}}\) and \(\frac{1}{\delta }\) is significantly larger than zero; it indicates that the utility of the treatment is very high. In this case, prioritizing treatment is recommended, and a positive sign suggests a preference for treatment. Therefore, \(\left(\frac{1}{{\gamma }_{h}}-\frac{1}{\delta }\right)\) indicates a greater inclination among affected individuals to get treatment rather than take no action.

Results and discussion

We have described in the previous section our mpox epidemic model \(({S}_{k}^{h}{V}_{k}^{h}{E}_{k}^{h}{I}_{k}^{h}{T}_{k}^{h}{R}_{k}^{h}{S}_{k}^{r}{E}_{k}^{r}{I}_{k}^{r})\) with heterogeneous networks to study the intricate dynamics of mpox disease, including vaccination and treatment games, in human and rodent populations. Due to the complexity of the model, we will rely on extensive numerical simulations to illustrate the rich dynamics of heterogeneous networks incorporating pharmaceutical and non-pharmaceutical interventions that mitigate the risk of viral outbreaks. We will demonstrate the application of our models by analyzing two different average degrees, namely \(\langle k\rangle =8\) and \(\langle k\rangle =16\), with four combinations of networks, including BA-BA, ER-ER, BA-ER, and ER-BA in human and rodent populations. We will demonstrate the overall dynamics of the mpox disease using line graph trajectory (Figs. 2, 3, 4, 5 and 6, Appendix A1–A3) and 2D phase diagrams (Figs. 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13 and 14). Below, we provide details of our numerical results. For ease of presentation, we have scaled the population sizes for humans and rodents to 1 so that the value of each compartment represents a percentage of the associated total population. To simplify the simulation results, we make the assumption \({\beta }_{rh}={\beta }_{hh}\) and \({\beta }_{hr}={\beta }_{rr}\) (symmetric), Asymmetric for Fig. 5, and did not consider human and rodent populations’ birth and death rates because our study is concerned with a relatively short time frame, the natural birth and death of humans and rodents may be neglected.

Impact of vaccine efficacy \((\eta =\text{0.1,0.5,0.9})\) on infected, vaccinated, treated, and recovered humans without EGT framework when the average degree \(\langle k\rangle =8\) (solid), and \(\langle k\rangle =16\) (dotted). The parameter settings are as follows: \({\beta }_{hh}=0.8333,{\beta }_{rr}=0.5,x=0.01,{\alpha }_{h}=0.125,{\alpha }_{r}=0.1,\sigma =0.0,{p}_{h}={p}_{r}=0.3,{\gamma }_{h}=0.05,{\gamma }_{r}=0.2,\tau =0.1,\delta =0.1.\)

Impact of the human-rodent protection rate \(({p}_{a}=\text{0.1,0.5,0.9})\) on infected, vaccinated, treated, and recovered humans with the EGT framework when the average degree \(\langle k\rangle =8\) (solid), and \(\langle k\rangle =16\) (dotted). The parameter settings are as follows: \(\begin{gathered} \beta _{{hh}} = 0.8333,\beta _{{rr}} = 0.5,\eta = 0.5,\alpha _{h} = 0.125,\alpha _{r} = 0.1,\sigma = 0.0,p_{h} = 0.0, \hfill \\ \gamma _{h} = 0.05,\gamma _{r} = 0.2,\delta = 0.1,\omega = 0.01,C_{V} = 0.5,C_{T} = 0.5,T_{a} = 0.0. \hfill \\ \end{gathered}\)

Impact of the human-to-animal transmission rate \((\sigma =\text{0.1,0.5,1.0})\) on infected, vaccinated, treated, and recovered humans with the EGT framework when the average degree \(\langle k\rangle =8\) (solid), and \(\langle k\rangle =16\) (dotted). The parameter settings are as follows: \(\begin{gathered} \beta _{{hh}} = 0.8333,\beta _{{rr}} = 0.5,\alpha _{h} = 0.125,\alpha _{r} = 0.1,p_{h} = 0.0,p_{r} = 0.0,\gamma _{h} = 0.05, \hfill \\ \gamma _{r} = 0.2,\delta = 0.1,\omega = 0.01,C_{V} = 0.5,C_{T} = 0.5,T_{a} = 0.0. \hfill \\ \end{gathered}\)

Impact of asymmetric transmission rate on infected, vaccinated, treated, recovered humans and infected rodents with the EGT framework when the average degree \(\langle k\rangle =8\) (solid), and \(\langle k\rangle =16\) (dotted). The parameter settings are as follows: \(\begin{gathered} \beta _{{rh}} = 1.0,\beta _{{hh}} = 0.8,\beta _{{rr}} = 0.7,\beta _{{hr}} = 0.3,\alpha _{h} = 0.125,\alpha _{r} = 0.1,p_{h} = 0.2,p_{r} = 0.3, \hfill \\ \gamma _{h} = 0.05,\gamma _{r} = 0.2,\delta = 0.1,\omega = 0.01,C_{V} = 0.5,C_{T} = 0.5,T_{a} = 0.0. \hfill \\ \end{gathered}\)

Impact of vaccine efficacy, vaccination, and treatment cost \((\left(\eta ,{C}_{V}, {C}_{T}\right)=\left(\text{0.1,0.9,0.9}\right),\left(\text{0.5,0.5,0.5}\right),\left(\text{0.9,0.9,0.9}\right),\left(\text{0.9,0.1,0.1}\right))\) on infected, vaccinated, treated, and recovered humans without the EGT framework when the average degree \(\langle k\rangle =8\) (solid), and \(\langle k\rangle =16\) (dotted). The parameter settings are as follows: \(\begin{gathered} \beta _{{hh}} = 0.8333,\beta _{{rr}} = 0.5,\alpha _{h} = 0.125,\alpha _{r} = 0.1,\sigma = 0.0,p_{h} = p_{r} = 0.3, \hfill \\ \gamma _{h} = 0.05,\gamma _{r} = 0.2,\delta = 0.1,\omega = 0.01,m = 0.1,T_{a} = 0.3. \hfill \\ \end{gathered}\)

(Panel A–D): The 2D heat maps of the final epidemic size (FES) showed the relationship between the protection against animal transmission \({(p}_{r})\) and the human–human transmission rate \(({\beta }_{h})\) in four different network panels: (A) BA(h)-BA(r), (B) ER(h)-BA(r), (C) BA(h)-ER(r), and (D) ER(h)-ER(r), where the number of average degree connection is \(<k>= 8\). The parameter settings are as follows: \(\begin{gathered} \beta _{{hh}} = 0.8333,\beta _{{rr}} = 0.5,\alpha _{h} = 0.125,\alpha _{r} = 0.1,\sigma = 0.5,p_{h} = 0.5,p_{r} = 0.0, \hfill \\ \gamma _{h} = 1/15,\gamma _{r} = 0.2,\delta = 0.1,\omega = 0.05,m = 0.1,C_{V} = 0.5,C_{T} = 0.5,T_{a} = 0.3. \hfill \\ \end{gathered}\)

(Panel A–D): The 2D heat maps of the final epidemic size (FES) showed the relationship between the protection against animal transmission \({(p}_{r})\) and the human–human transmission rate \(({\beta }_{h})\) in four different network panels: (A) BA(h)-BA(r), (B) ER(h)-BA(r), (C) BA(h)-ER(r), and (D) ER(h)-ER(r), where the number of average degree connection is \(<k>= 16\). The parameter settings are as follows: \(\begin{gathered} \beta _{{hh}} = 0.8333,\beta _{{rr}} = 0.5,\alpha _{h} = 0.125,\alpha _{r} = 0.1,\sigma = 0.5,p_{h} = 0.5,p_{r} = 0.0, \hfill \\ \gamma _{h} = 1/15,\gamma _{r} = 0.2,\delta = 0.1,\omega = 0.05,m = 0.1,C_{V} = 0.5,C_{T} = 0.5,T_{a} = 0.3. \hfill \\ \end{gathered}\)

(Panel A–D): The 2D heat maps of vaccine coverage (VC) showed the relationship between the protection against animal transmission \({(p}_{r})\) and the human–human transmission rate \(({\beta }_{h})\) in four different network panels: (A) BA(h)-BA(r), (B) ER(h)-BA(r), (C) BA(h)-ER(r), and (D) ER(h)-ER(r), where the number of average degree connection is \(<k>= 8\). The parameter settings are as follows: \(\begin{gathered} \beta _{{hh}} = 0.8333,\beta _{{rr}} = 0.5,\alpha _{h} = 0.125,\alpha _{r} = 0.1,\sigma = 0.5,p_{h} = 0.5,p_{r} = 0.0, \hfill \\ \gamma _{h} = 1/15,\gamma _{r} = 0.2,\delta = 0.1,\omega = 0.05,m = 0.1,C_{V} = 0.5,C_{T} = 0.5,T_{a} = 0.3. \hfill \\ \end{gathered}\)

(Panel A–D): The 2D heat maps of vaccine coverage (VC) showed the relationship between the protection against animal transmission \({(p}_{r})\) and the human–human transmission rate \(({\beta }_{h})\) in four different network panels: (A) BA(h)-BA(r), (B) ER(h)-BA(r), (C) BA(h)-ER(r), and (D) ER(h)-ER(r), where the number of average degree connection is \(<k>= 16\). The parameter settings are as follows: \(\begin{gathered} \beta _{{hh}} = 0.8333,\beta _{{rr}} = 0.5,\alpha _{h} = 0.125,\alpha _{r} = 0.1,\sigma = 0.5,p_{h} = 0.5,p_{r} = 0.0, \hfill \\ \gamma _{h} = 1/15,\gamma _{r} = 0.2,\delta = 0.1,\omega = 0.05,m = 0.1,C_{V} = 0.5,C_{T} = 0.5,T_{a} = 0.3. \hfill \\ \end{gathered}\)

(Panel A–D): The 2D heat maps of the portion of treated individuals (PTI) showed the relationship between the protection against animal transmission \({(p}_{r})\) and the human–human transmission rate \(({\beta }_{h})\) in four different network panels: (A) BA(h)-BA(r), (B) ER(h)-BA(r), (C) BA(h)-ER(r), and (D) ER(h)-ER(r), where the number of average degree connection is \(<k>= 8\). The parameter settings are as follows: \(\begin{gathered} \beta _{{hh}} = 0.8333,\beta _{{rr}} = 0.5,\alpha _{h} = 0.125,\alpha _{r} = 0.1,\sigma = 0.5,p_{h} = 0.5,p_{r} = 0.0, \hfill \\ \gamma _{h} = 1/15,\gamma _{r} = 0.2,\delta = 0.1,\omega = 0.05,m = 0.1,C_{V} = 0.5,C_{T} = 0.5,T_{a} = 0.3. \hfill \\ \end{gathered}\)

(Panel A–D): The 2D heat maps of the portion of treated individuals (PTI) showed the relationship between the protection against animal transmission \({(p}_{r})\) and the human–human transmission rate \(({\beta }_{h})\) in four different network panels: (A) BA(h)-BA(r), (B) ER(h)-BA(r), (C) BA(h)-ER(r), and (D) ER(h)-ER(r), where the number of average degree connection is \(<k>= 16\). The parameter settings are as follows: \(\begin{gathered} \beta _{{hh}} = 0.8333,\beta _{{rr}} = 0.5,\alpha _{h} = 0.125,\alpha _{r} = 0.1,\sigma = 0.5,p_{h} = 0.5,p_{r} = 0.0, \hfill \\ \gamma _{h} = 1/15,\gamma _{r} = 0.2,\delta = 0.1,\omega = 0.05,m = 0.1,C_{V} = 0.5,C_{T} = 0.5,T_{a} = 0.3. \hfill \\ \end{gathered}\)

(Panel A–D): The 2D heat maps of the average social payoff (ASP) showed the relationship between the protection against animal transmission \({(p}_{r})\) and the human–human transmission rate \(({\beta }_{h})\) in four different network panels: (A) BA(h)-BA(r), (B) ER(h)-BA(r), (C) BA(h)-ER(r), and (D) ER(h)-ER(r), where the number of average degree connection is \(<k>= 8\). The parameter settings are as follows: \(\begin{gathered} \beta _{{hh}} = 0.8333,\beta _{{rr}} = 0.5,\alpha _{h} = 0.125,\alpha _{r} = 0.1,\sigma = 0.5,p_{h} = 0.5,p_{r} = 0.0, \hfill \\ \gamma _{h} = 1/15,\gamma _{r} = 0.2,\delta = 0.1,\omega = 0.05,m = 0.1,C_{V} = 0.5,C_{T} = 0.5,T_{a} = 0.3. \hfill \\ \end{gathered}\)

(Panel A–D): The 2D heat maps of the average social payoff (ASP) showed the relationship between the protection against animal transmission \({(p}_{r})\) and the human–human transmission rate \(({\beta }_{h})\) in four different network panels: (A) BA(h)-BA(r), (B) ER(h)-BA(r), (C) BA(h)-ER(r), and (D) ER(h)-ER(r), where the number of average degree connection is \(<k>= 16\). The parameter settings are as follows: \(\begin{gathered} \beta _{{hh}} = 0.8333,\beta _{{rr}} = 0.5,\alpha _{h} = 0.125,\alpha _{r} = 0.1,\sigma = 0.5,p_{h} = 0.5,p_{r} = 0.0, \hfill \\ \gamma _{h} = 1/15,\gamma _{r} = 0.2,\delta = 0.1,\omega = 0.05,m = 0.1,C_{V} = 0.5,C_{T} = 0.5,T_{a} = 0.3. \hfill \\ \end{gathered}\)

Figure 2 illustrates the impact of vaccine efficacy \(\eta =\text{0.1,0.5,0.9}\) on infected, vaccinated, treated, and recovered humans without the EGT framework when the average degree \(\langle k\rangle =8\), and \(\langle k\rangle =16\). Firstly, due to the increasing vaccine efficacy rate, the population curve of infected, treated, and recovered individuals shows a declining trend, whereas the vaccinated curve reveals an increasing trend and an anticipated payoff. When \(\langle k\rangle =8\) and the human and rodent populations both maintain the BA-SF network, we see the highest infected curve (solid red line), followed by ER(h)-BA(r) (solid black line), BA(h)-ER(r) (solid green line), and ER(h)-ER(r) (solid blue line). It is worth mentioning that the disease curve shows the lowest final epidemic size (FES) when both populations maintain the ER(h)-ER(r) setting among the four different settings, whereas reverse scenarios appear for \(\langle k\rangle =16\), which has happened owing to the network structure. We know that the Barabási-Albert (BA) scale-free network has hubs, which act like super-spreaders; as a result, the highest epidemic curve is revealed when both populations follow the Barabási-Albert (BA) scale-free network. Therefore, when society maintains this network setting, it faces difficulty maintaining the Barabási-Albert (BA) scale-free network setting interaction of human and rodent populations. In addition, the Erdos–Renyi (ER) random network lacks such types of hubs, and the lowest epidemic curve is observed when both populations follow this network. When \(\langle k\rangle =16\), the hub’s existence has vanished, and we witness the high epidemic curve (blue dotted line) when both populations follow the ER network, as it follows the poison degree distribution. In subfigure \(a(i)\), we observe that when vaccine efficacy is low \((\eta =0.1)\), BA(h)-ER(r) (solid green line) and ER(h)-BA(r) (solid black line) network settings representing disease curves are coexisting with each other. Then, due to the increasing rate of \((\eta =\text{0.5,0.9})\), in all network settings, the disease curves are separately visible. The scenarios for vaccinated, treated, and related curves illustrate recovered populations. In the case of people who recover, most individuals who follow the BA(h)-BA(r) setting have recovered from the mpox disease quickly. Another exciting outcome is the curves of the infected, treated, and recovered, quickly reaching the pinnacle point and diminishing quickly from society at the earliest time when \(\langle k\rangle =16\), with opposite scenarios for the vaccination curve. In real-world phenomena, when the average number of connections is high, more people rapidly become infected with the disease. We know that many men have multiple thinking, motivating them to participate in vaccination programs. For this reason, the curve for the vaccinated people shows the opposite outcome, an expected result. On top of that, no change exists in the outcome of the infected animal (Fig. 2, subfigure \({(e}^{-*}\))).

Figure 3 illustrates the impact of the human-rodent protection rate on the dynamics of mpox disease in human society. A higher human-rodent protection rate significantly reduces the expansion of mpox, a viral zoonotic disease transferred from animals to people. Effective interventions to protect people from rodent exposure, such as enhanced sanitation, rodent control programs, and public health instruction, can dramatically lower the risk of mpox transmission (Fig. 3, panel a(-*)). Since rodents are possible reservoirs for the virus, minimizing their contact with people reduces the chance of zoonotic spillover incidents. High protection rates \(({p}_{r}=0.9)\) assist in limiting outbreaks, decreasing human cases (Fig. 3, subfigure \(a(iii)\)), and preventing the virus from getting a foothold in new populations. Consequently, strengthening human-rodent protection defends individual health and supports more significant public health efforts to reduce mpox epidemics and avoid future occurrences. Furthermore, in all subfigures of Fig. 3, it is crystal clear that all network settings work impeccably for average degree connections \(\langle k\rangle =8\), and \(\langle k\rangle =16\). Due to the increasing rate of \({p}_{r},\) fewer people are infected with mpox disease, and more are participating in the vaccination program. As a result, treated and recovered curves exhibit dwindling characteristics, as expected. Figure 3 illustrates the result of mpox disease dynamics for a medium level of the cost of vaccination (\({C}_{V}=0.5\)), treatment \(({C}_{T}=0.5)\), and efficacy of the vaccine \((\eta =0.5)\). If the cost of vaccination and treatment is low and vaccine efficacy is high, we could achieve a disease-free society.

Figure 4 represents the intricate dynamics of the mpox disease when it transmits from human to rodent populations for average degree connections \(\langle k\rangle =8\), and \(\langle k\rangle =16\) in the combination of heterogeneous networks, Barabási-Albert (BA) scale-free and Erdős-Rényi (ER) random networks. The transmission rate of mpox from humans to animals is crucial in comprehending the disease’s dissemination and persistence. Particularly in areas where wildlife or domestic animals interact closely with individuals who are sick, the transmission of mpox from people to animals can establish new reservoirs for the virus, thereby augmenting the likelihood of future outbreaks via zoonotic spillback. This reservoir hampers eradication attempts, necessitating consideration of human and animal populations in containment techniques. The zoonotic cycle complicates outbreak containment, as infected animals can retain and reintroduce the virus to human populations, even after a decline in human cases. The danger is especially alarming in regions with significant biodiversity or intense human-animal interactions, as the virus can adapt or disseminate across multiple animal species, thereby increasing the likelihood of recurring outbreaks. Thus, monitoring and regulating human-to-animal transmission is crucial for mitigating the long-term public health consequences of mpox. Figure 4, panel (a-*) reveals that for the increasing rate of human-to-animal transmission \(\sigma\), more people are infected with mpox disease, as infected animals demonstrate an increasing outcome (panel (e-*)), which leads to a hazardous situation in society. When many people are infected with mpox disease, they have to take treatment (panel (c-*)) to recover from the disease, even if vaccination programs are continuing. People thus face a dilemma (panel (c-*)) about participating in vaccination programs.

Figure 5 depicts the temporal dynamics of mpox transmission characterized by asymmetric cross-species transmission probabilities: a high animal-to-human rate (\({\beta }_{rh}=1.0\)), moderate human-to-human (\({\beta }_{hh}=0.8\)) and animal-to-animal (\({\beta }_{rr}=0.7\)), and a low human-to-animal transmission rate (\({\beta }_{hr}=0.3\)). Each subplot juxtaposes four human-animal network combinations, BA(h)-BA(r), ER(h)-BA(r), BA(h)-ER(r), and ER(h)-ER(r), across two average connectivity levels (\(\langle k\rangle\)= 8 and 16), denoted by solid and dotted lines, respectively.

Panel (a) exemplifies the human infection curves, which exhibit a pronounced epidemic peak attributable to the elevated \({\beta }_{rh}\) value. The ER(h)-ER(r) combination (solid and dotted blue) yields the earliest and most pronounced peak in both connectivity scenarios, indicating that homogeneous networks facilitate a more rapid and coordinated dissemination. Conversely, BA(h)-BA(r) (solid and dotted red) exhibits a more gradual increase and a somewhat smaller peak attributable to hub-based delay effects, whereby initial infections stay confined before spreading to central nodes. Enhanced connectedness (\(\langle k\rangle =16\)) leads to earlier and more severe breakouts across all network types, aligning with increased exposure potential.

Panel (b) illustrates the vaccinated human population, which expands rapidly in ER(h)-ER(r) due to accelerated transmission, facilitating a swifter response. A higher degree (\(\langle k\rangle =16\)) increases vaccination across all contexts. Notably, BA(h)-ER(r) and BA(h)-BA(r) exhibit a slower vaccination rate, indicating a lag in the dissemination of infection throughout the human network.

Panel (c) shows treated human cases, which reflect the patterns of infection. The ER(h)-ER(r) situation again results in the most expedited and severe need for treatment. Treatment curves exhibit increased height and reduced width at \(\langle k\rangle =16\), indicating that higher connection density condenses the epidemic into a more concise temporal framework.

Panel (d) depicts cumulative recovery. All scenarios converge on comparable end levels; however, recovery transpires more rapidly in ER-based networks, indicative of earlier infection and treatment. BA(h)-based networks, especially at lower \(\langle k\rangle\), demonstrate a protracted convergence to optimal recovery owing to postponed epidemic timing.

Ultimately, panel (e) illustrates the dynamics of infected animals. Notwithstanding the comparatively modest \({\beta }_{hr}=0.3\), animals undergo substantial infection surges propelled by the feedback mechanism from human epidemics. BA(r)-based topologies exhibit marginally earlier and elevated peaks, aligning with central nodes that enhance intra-reservoir transmission.

Finally, Fig. 5 underscores the substantial influence of network topology and asymmetric transmission on the magnitude, timing, and public health responses to outbreaks. Intense animal-to-human transmission necessitates prioritizing reservoir monitoring and control, whereas network-informed treatments (such as targeting hubs in BA(h)) are crucial for mitigating delayed but significant human outbreaks.

Figure 6 depicts the consequence of mpox disease dynamics in the presence of both the vaccination and treatment games, more precisely, cost-effective analysis of mpox in the combination of heterogeneous network settings (average degree \(\langle k\rangle =8\), and \(\langle k\rangle =16\)). It is well-known that the effectiveness of vaccines and the related expenses of vaccination and treatment are essential in reducing the transmission of mpox. Higher vaccination effectiveness (\(\eta =0.9\)) and lower cost of vaccination and treatment (\({C}_{V}=0.1, {C}_{T}=0.1\)) can significantly decrease infection rates by conferring protection to a substantial population segment, thereby reducing transmission and averting outbreaks (subfigure \(a(iv)\)). If the effectiveness of vaccines outweighs the cost, people will be more motivated to participate in vaccination programs (subfigure \(b(iv)\)). As a result, fewer people need to take treatment (subfigure \(c(iv)\)), and the recovered curve shows dwindling outcomes (subfigure \(d(iv)\)). On top of that, in the case of high vaccination effectiveness and higher cost of vaccination, people may also participate in vaccination programs (subfigure \(b(iii)\)). Furthermore, vaccination initiatives need significant financial resources to develop, distribute, and deliver vaccines. The expenses associated with treating those already infected must also be considered, since they affect healthcare systems and social burdens. Therefore, efficient vaccination strategies can reduce the need for expensive treatment by preventing severe instances, while understanding vaccine effectiveness helps policymakers optimize budget allocation. Ultimately, reconciling vaccine effectiveness with budgetary considerations enables a comprehensive strategy for controlling mpox, particularly in resource-constrained countries and regions where healthcare support is limited.

Now, in Fig. 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13 and 14, we demonstrate the final epidemic size (FES) (subfigure 7–8), vaccination coverage (VC) (subfigure 9–10), portion of treated individuals (PTI) (subfigure 11–12), and average social payoff (ASP) (subfigure 13–14) of our proposed mpox models through 2D heat maps at equilibrium \((t\to \infty )\) in the four combinations of heterogenous network settings (average degree \(\langle k\rangle =8\), and \(\langle k\rangle =16\)) to enhance intuitive comprehension of the relationship between the mpox epidemic propagation and heterogeneous network environments. The x-axis and y-axis represent protection against animal transmission \({(p}_{r})\) and the human–human transmission rate \(({\beta }_{h})\), respectively. According to Fig. 7, mpox disease spreads faster among the four network settings when human and rodent populations follow the Barabási-Albert (BA) scale-free network setting to complete their daily activities, with an average degree 〈k〉 = \(8\). When humans follow the Erdős-Rényi (ER) random network and the rodent population maintains a Barabási-Albert (BA) scale-free network, mpox disease spreads faster, but less so than in panel A. The disease spreading rate is so low in panels C and D compared to panels A and B. The disease-spreading rate is lowest among the four heterogeneous network settings when human and rodent populations maintain an Erdős-Rényi (ER) random network framework, since there is no hub structure in an Erdős-Rényi (ER) random network, whereas the Barabási-Albert (BA) scale-free network has this. Due to the hub characteristics of the Barabási-Albert (BA) scale-free network, the disease spreads faster than in the Erdős-Rényi (ER) random network; more precisely, when rodent populations follow the Barabási-Albert (BA) scale-free network, the disease spreads remarkably quickly. In addition, when the average degree \(\langle k\rangle =16\), there is no hub structure in Barabási-Albert (BA) scale-free and Erdős-Rényi (ER) random networks. As a result, we observed less FES in Fig. 8, panels A and B, compared to panels C and D. In panel A, both human and rodent populations maintain the Barabási-Albert (BA) scale-free network, while panel B maintains the ER(h) and BA(r) settings.

On the other hand, when vaccine efficacy \((\eta =0.1)\) and personal protection against mpox-infected individuals \(({p}_{h}=0.1)\) is low; the mpox disease spreads in society so quickly, and humans face a hazardous situation (Fig. 7, panel A, subfigure \(a(i)\)). Few people participate in vaccination programs (Fig. 9, panel A, subfigure \(a(i)\)), and a significant number of infected individuals (Fig. 14, panel A, subfigure \(a(i)\)) need treatment to recover from mpox disease. In addition, the situation would not significantly improve even with a higher value of \({p}_{h}=0.9\) due to the lower vaccine efficacy (Fig. 7, panel A, subfigure \(a(iii)\)). A dramatic change (Fig. 7, panel A, subfigure \(a\left(ii\right) \text{and} a(iv)\)) happens when the vaccine efficacy is much higher \((\eta =0.9)\), which is also true for Fig. 7, panels B, C, and D. According to the 2D heat map of Fig. 7, panels C and D, the mpox disease almost dies out, and disease is only seen in the upper-left corner of subfigure \(c\left(ii\right) \text{and} c(iv)\)) due to the lower rate of personal protection against animal transmission \({(p}_{r})\) and the higher human–human transmission rate \(({\beta }_{h})\). In that case, many humans receive the mpox vaccination (Fig. 9, panels A–D), and due to higher vaccination coverage, the disease has almost vanished from the infected region, dramatically reducing PTI (Fig. 11, panels A–D). In addition, a worse scenario compared to Figs. 7, 9, 11, panel A-D is shown when the average degree \(\langle k\rangle =16\) (Figs. 8, 10, 12, panel A–D).

Now, it is time to concentrate on the average social payoff (ASP) analysis illustrated in Fig. 13 and 14 of our proposed mpox model, as such types of analysis improve the utility and relevance of epidemic modeling by offering a thorough framework for assessing, contrasting, and refining intervention options within complex social systems. Realistically, when the cost of vaccination and treatment is high, it directly impacts the FES. In such conditions, people face a dilemma about participating in a vaccination program and receiving treatment. To depict the ASP diagram of our model, we consider the medium value of vaccination and treatment costs (\({{C}_{V}=0.5 \text{and} C}_{T}=0.5)\). According to Fig. 13, panels A-D, subfigure \(a(i)\), many people are in a dilemma condition and do not participate in the vaccination program, resulting in higher FES and PTI and lower VC and ASP. The analogous result is displayed in Fig. 14 with even worse consequence scenarios for the average degree \(\langle k\rangle =16\). Therefore, if policymakers can provide effective and low-cost vaccination and treatment, the disease scenario will change dramatically, allowing people to lead healthier and happier lives. Otherwise, it could lead to a treacherous scenario for our society.

Conclusion

This research work offers a novel approach toward a thorough understanding of the complex dynamics of the mpox epidemics, using the evolutionary game theory framework with the combination of Barabási-Albert (BA) scale-free and Erdős-Rényi (ER) random networks (four network settings with BA-BA, ER-ER, BA-ER, and ER-BA in humans and animals). In addition, our EGT methodology, which integrates the adaptive actions of individuals according to their perceived risk of infection, elucidates the essential function of strategic decision-making in disease control. By modeling interactions between animal (rodent) and human populations, we successfully elucidated the rich dynamics of disease spread across different networks, emphasizing the distinct transmission patterns arising from diverse structures. We also represented the effects of symmetric and asymmetric cross-species transmission on mpox dynamics.

Our simulated results across several scenarios indicate that reducing the average connectedness in human contact networks (\(\langle k\rangle =8\)) significantly reduces the peak and transmission of mpox infections. Barabási-Albert (BA) scale-free networks, distinguished by hubs, facilitate more rapid and severe epidemics than Erdős-Rényi (ER) random networks. Consequently, public health initiatives must focus on curtailing super-spreader occurrences and minimizing high-frequency encounters, particularly in urban and highly interconnected environments. Enhancing vaccination effectiveness (\(\eta\)), as seen in Figs. 2 and 6, consistently results in decreased infections and expedited recovery rates. Encouraging individual protective behavior (\({p}_{h}\)) against infected humans, particularly when adoption is prevalent (\({p}_{h}=0.9\)), substantially aids in flattening the infection curve. Moreover, enhanced treatment accessibility (increased \({T}_{a}\)) and expedited recovery rates (decreased \({\delta }^{-1}\)) contribute to alleviating the effects of mpox disease. Therefore, an integrated approach that encompasses high vaccination effectiveness, behavioral incentives for safeguarding, prompt treatment availability, and focused treatments in highly interconnected hubs is crucial for efficiently administering human mpox.

Rodents serve as a continual zoonotic reservoir for mpox, with their network structure crucial for disease persistence and spillover. Therefore, the rodent network is crucial for maintaining and transmitting mpox infections to humans, particularly through cross-species contact. Our results demonstrate that networks exhibiting a higher average degree (\(\langle k\rangle =16\)) and Barabási-Albert (BA) scale-free network-type structures among the rodent population are associated with increased infection rates in rodents and humans. Effective rodent control should interrupt high-contact patterns by diminishing rodent population density and interactions in hotspots, especially in areas prone to human-rodent contact. Enhancing rodent-specific protective behaviors (\({p}_{r}\)), via enhanced cleanliness, pest management, and public knowledge, substantially reduces the infection reservoir, as seen in Fig. 3. As diseased animals exhibit analogous epidemic trajectories to humans (e.g., Figs. 4 and 5), mitigating animal diseases indirectly improves human health. Thus, comprehensive rodent control strategies, including environmental sanitation, reducing access to food and waste, and targeted actions in areas with high rodent populations, are essential for disrupting the zoonotic transmission cycle of mpox.

We recognize several limitations: the model assumes static network topologies, excludes individual-level behavioral variability, and relies on mean-field ordinary differential equation dynamics. These simplifications can overlook limited correlation effects and stochastic variations. Future research should include agent-based simulations to corroborate the mean-field findings and investigate temporal networks or geographical dynamics. Furthermore, including empirical contact data and examining species-specific intervention options enhances policy relevance. Our results highlight the significance of network-informed techniques in controlling zoonotic outbreaks, such as mpox, and provide a basis for more focused and practical interventions.

In recapitulation, this study offers valuable insights into the relationship between network topologies and behavioral responses, which influence the progression of mpox epidemics. Policymakers and public health authorities could utilize these insights to design more targeted treatments, focusing on high-risk nodes in scale-free networks or employing more comprehensive strategies in uniform network structures.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

About MPOX | MPOX | Poxvirus | CDC. https://www.cdc.gov/poxvirus/monkeypox/about/index.html (n.d.).

World Health Organization: WHO. Monkeypox. https://www.who.int/health-topics/monkeypox#tab=tab_1 (2019).

WHO declares the mpox virus a public health emergency of international concern. UN News. https://news.un.org/en/story/2024/08/1153176 (2024).

Bankuru, S. V. et al. A game-theoretic model of Monkeypox to assess vaccination strategies. PeerJ 8, e9272. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.9272 (2020).

Idisi, O. I. et al. A new compartmentalized epidemic model to analytically study the impact of awareness on the control and mitigation of the monkeypox disease. Healthc. Anal. 4, 100267. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.health.2023.100267 (2023).

Usman, S. & Adamu, I. I. Modeling the transmission dynamics of the monkeypox virus infection with treatment and vaccination interventions. J. Appl. Math. Phys. 05(12), 2335–2353. https://doi.org/10.4236/jamp.2017.512191 (2017).

Allehiany, F., DarAssi, M. H., Ahmad, I., Khan, M. A. & Tag-Eldin, E. M. Mathematical Modeling and backward bifurcation in monkeypox disease under real observed data. Res. Phys. 50, 106557. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rinp.2023.106557 (2023).

Riaz, A. Monkeypox and its Outbreak. Pak. Biomed. J. https://doi.org/10.54393/pbmj.v5i8.792 (2022).

Focosi, D., Novazzi, F., Baj, A. & Maggi, F. Monkeypox: An international epidemic. Rev. Med. Virol. 32(6), e2392. https://doi.org/10.1002/rmv.2392 (2022).

Elsonbaty, A., Adel, W., Aldurayhim, A. & El-Mesady, A. Mathematical modeling and analysis of a novel monkeypox virus spread integrating imperfect vaccination and nonlinear incidence rates. Ain Shams Eng. J. 15(3), 102451. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asej.2023.102451 (2024).

Ola, P. Monkeypox is the manifestation of spectral diseases and not of monkeypox virus transmission. https://doi.org/10.31219/osf.io/k3ayb (2022).

Peter, O. J., Madubueze, C. E., Ojo, M. M., Oguntolu, F. A. & Ayoola, T. A. Modeling and optimal control of Monkeypox with cost-effective strategies. Model. Earth Syst. Environ. 9(2), 1989–2007. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40808-022-01607-z (2022).

Maruotti, A., Böhning, D., Rocchetti, I. & Ciccozzi, M. Estimating the undetected infections in the Monkeypox outbreak. J. Med. Virol. 95(1), e28099. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmv.28099 (2022).

Damon, I. K. (2014). Monkeypox virus: Insights on its emergence in human populations. In ASM Press eBooks (pp. 85–97). https://doi.org/10.1128/9781555815585.ch5

Islam, M. R., Hasan, M., Rahman, M. S. & Rahman, M. A. Monkeypox outbreak—No panic and stigma; Only awareness and preventive measures can halt the pandemic turn of this epidemic infection. Int. J. Health Plann. Manag. 37(5), 3008–3011. https://doi.org/10.1002/hpm.3539 (2022).

Peter, O. J. et al. Transmission dynamics of Monkeypox virus: A mathematical modeling approach. Model. Earth Syst. Environ. 8(3), 3423–3434. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40808-021-01313-2 (2021).

Qurashi, M. A., Rashid, S., Alshehri, A., Jarad, F. & Safdar, F. New numerical dynamics of the fractional monkeypox virus model transmission pertaining to nonsingular kernels. Math. Biosci. Eng. 20(1), 402–436. https://doi.org/10.3934/mbe.2023019 (2022).

Tanimoto, J. Fundamentals of Evolutionary Game Theory and its Applications, in Evolutionary Economics and Social Complexity Science (Springer, 2015).

Tanimoto, J. Sociophysics Approach to Epidemics in Evolutionary Economics and Social Complexity Science (Springer, 2021).

Tuite, A. R. et al. Cholera Epidemic in Haiti, 2010: Using a transmission model to explain spatial spread of disease and identify optimal control interventions. Ann. Intern. Med. 154(9), 593. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-154-9-201105030-00334 (2011).

Shim, E., Grefenstette, J. J., Albert, S. M., Cakouros, B. E. & Burke, D. S. A game dynamic model for vaccine skeptics and vaccine believers: Measles as an example. J. Theor. Biol. 295, 194–203. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtbi.2011.11.005 (2012).

Kuga, K. & Tanimoto, J. Which is more effective for suppressing an infectious disease: Imperfect vaccination or defense against contagion?. J. Stat. Mech. Theory Exp. 2018(2), 023407. https://doi.org/10.1088/1742-5468/aaac3c (2018).

Bauch, C. T. & Bhattacharyya, S. Evolutionary game theory and social learning can determine how vaccine scares unfold. PLOS Comput. Biol. 8(4), e1002452. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1002452 (2012).

Bhattacharyya, S., Bauch, C. T. & Breban, R. Role of word-of-mouth for programs of voluntary vaccination: A game-theoretic approach. Math. Biosci. 269, 130–134. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mbs.2015.08.023 (2015).

Ullah, M. S., Higazy, M. & Kabir, K. A. Dynamic analysis of mean-field and fractional-order epidemic vaccination strategies by evolutionary game approach. Chaos Solitons Fractals 162, 112431. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chaos.2022.112431 (2022).

Alam, M., Kabir, K. M. A. & Tanimoto, J. Based on mathematical epidemiology and evolutionary game theory, which is more effective: Quarantine or isolation policy?. J. Stat. Mech. Theory Exp. 2020(3), 033502. https://doi.org/10.1088/1742-5468/ab75ea (2020).

Kabir, K. M. A., Risa, T. & Tanimoto, J. Prosocial behavior of wearing a mask during an epidemic: an evolutionary explanation. Sci. Rep. 11(1), 12621. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-92094-2 (2021).

Zobayer, A., Ullah, M. S. & Ariful Kabir, K. M. A cyclic behavioral modeling aspect to understand the effects of vaccination and treatment on epidemic transmission dynamics. Sci. Rep. 13(1), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-35188-3 (2023).

Arefin, M. R., Masaki, T., Kabir, K. M. A. & Tanimoto, J. Interplay between cost and effectiveness in influenza vaccine uptake: A vaccination game approach. Proc. R. Soc. Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 475(2232), 20190608. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspa.2019.0608 (2019).

Kabir, K. M. A. & Tanimoto, J. Modelling and analysing the coexistence of dual dilemmas in the proactive vaccination game and retroactive treatment game in epidemic viral dynamics. Proc. R. Soc. Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 475(2232), 20190484. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspa.2019.0484 (2019).

Kabir, K. M. A., Jusup, M. & Tanimoto, J. Behavioral incentives in a vaccination-dilemma setting with optional treatment. Phys. Rev. E 100(6), 062402. https://doi.org/10.1103/physreve.100.062402 (2019).

Glaubitz, A. & Fu, F. Social dilemma of non-pharmaceutical interventions: Determinants of dynamic compliance and behavioral shifts. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 121(50), e2407308121. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2407308121 (2024).

Fu, F., Rosenbloom, D. I., Wang, L. & Nowak, M. A. Imitation dynamics of vaccination behaviour on social networks. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 278(1702), 42–49. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2010.1107 (2010).

Chen, X. & Fu, F. Imperfect vaccine and hysteresis. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 286(1894), 20182406. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2018.2406 (2019).

Chang, S. L., Piraveenan, M., Pattison, P. & Prokopenko, M. Game theoretic modelling of infectious disease dynamics and intervention methods: A review. J. Biol. Dyn. 14(1), 57–89. https://doi.org/10.1080/17513758.2020.1720322 (2020).

Kabir, K. A. Impact of human cooperation on vaccination behaviors. Heliyon 9(6), e16748. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e16748 (2023).

Augsburger, I. B., Galanthay, G. K., Tarosky, J. H., Rychtář, J. & Taylor, D. Voluntary vaccination may not stop monkeypox outbreak: A game-theoretic model. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 16(12), e0010970. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0010970 (2022).

Ullah, M. S. & Kabir, K. A. Behavioral game of quarantine during the monkeypox epidemic: Analysis of deterministic and fractional order approach. Heliyon 10(5), e26998. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e26998 (2024).

Barnes, J. A. Class and committees in a Norwegian island parish. Hum. Relat. 7(1), 39–58. https://doi.org/10.1177/001872675400700102 (1954).

Klovdahl, A. S. Social networks and the spread of infectious diseases: The AIDS example. Soc. Sci. Med. 21(11), 1203–1216. https://doi.org/10.1016/0277-9536(85)90269-2 (1985).

Moreno, Y., Pastor-Satorras, R. & Vespignani, A. Epidemic outbreaks in complex heterogeneous networks. Eur. Phys. J. B 26(4), 521–529. https://doi.org/10.1140/epjb/e20020122 (2002).

Zhang, H. & Fu, X. Spreading of epidemics on scale-free networks with nonlinear infectivity. Nonlinear Anal. 70(9), 3273–3278. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.na.2008.04.031 (2009).

Zhang, J. & Sun, J. Stability analysis of an SIS epidemic model with a feedback mechanism on networks. Physica A 394, 24–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physa.2013.09.058 (2014).

Wang, Z. et al. Statistical physics of vaccination. Phys. Rep. 664, 1–113. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physrep.2016.10.006 (2016).

Zhang, J. & Jin, Z. The analysis of an epidemic model on networks. Appl. Math. Comput. 217(17), 7053–7064. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amc.2010.09.063 (2011).

Callaway, D. S., Newman, M. E. J., Strogatz, S. H. & Watts, D. J. Network Robustness and Fragility: Percolation on random graphs. Phys. Rev. Lett. 85(25), 5468–5471. https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevlett.85.5468 (2000).

Boguñá, M., Pastor-Satorras, R. & Vespignani, A. Absence of epidemic threshold in scale-free networks with degree correlations. Phys. Rev. Lett. 90(2), 028701. https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevlett.90.028701 (2003).

Liljeros, F., Edling, C. R., Amaral, L. A. N., Stanley, H. E. & Aberg, Y. The web of human sexual contacts. Nature 411(6840), 907–908. https://doi.org/10.1038/35082140 (2001).

Wan, C., Li, T., Zhang, W. & Dong, J. Dynamics of epidemic spreading model with drug-resistant variation on scale-free networks. Physica A 493, 17–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physa.2017.10.027 (2018).

Ullah, M. S., Kamrujjaman, M. & Kabir, K. M. A. Understanding the relationship between stay-at-home measures and vaccine shortages: A conventional, heterogeneous, and fractional dynamic approach. J. Health Popul. Nutr. 43(1), 32. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41043-024-00505-7 (2024).

Kabir, K. A., Kuga, K. & Tanimoto, J. The impact of information spreading on epidemic vaccination game dynamics in a heterogeneous complex network- A theoretical approach. Chaos Solitons Fractals 132, 109548. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chaos.2019.109548 (2020).

Kuga, K. & Tanimoto, J. Impact of imperfect vaccination and defense against contagion on vaccination behavior in complex networks. J. Stat. Mech: Theory Exp. 2018(11), 113402. https://doi.org/10.1088/1742-5468/aae84f (2018).

Meng, X., Cai, Z., Si, S. & Duan, D. Analysis of epidemic vaccination strategies on heterogeneous networks: Based on the SEIRV model and evolutionary game. Appl. Math. Comput. 403, 126172. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amc.2021.126172 (2021).

Hota, A. R. & Sundaram, S. Game-theoretic vaccination against networked SIS epidemics and impacts of human decision-making. IEEE Trans. Control Netw. Syst. 6(4), 1461–1472. https://doi.org/10.1109/tcns.2019.2897904 (2019).

Fukuda, E. et al. Risk assessment for infectious disease and its impact on voluntary vaccination behavior in social networks. Chaos Solitons Fractals 68, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chaos.2014.07.004 (2014).

Erdős, P. & Rényi, A. On random graphs. Publ. Math. 6(1), 290–297 (1959).

BarabáSi, A. & Albert, R. Emergence of scaling in random networks. Science 286(5439), 509–512. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.286.5439.509 (1999).

Pastor-Satorras, R. & Vespignani, A. Epidemic spreading in Scale-Free networks. Phys. Rev. Lett. 86(14), 3200–3203. https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevlett.86.3200 (2001).

Pastor-Satorras, R. & Vespignani, A. Epidemic dynamics in finite-size scale-free networks. Phys. Rev. E 65(3), 035108. https://doi.org/10.1103/physreve.65.035108 (2002).

Pennisi, E. On the origin of cooperation. Science 325(5945), 1196–1199. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.325_1196 (2009).

Kabir, K. M. A. & Tanimoto, J. Cost-efficiency analysis of voluntary vaccination against n-serovar diseases using antibody-dependent enhancement: A game approach. J. Theor. Biol. 503, 110379. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtbi.2020.110379 (2020).

Tori, R. & Tanimoto, J. A study on the prosocial behavior of wearing a mask and self-quarantining to prevent the spread of diseases underpinned by evolutionary game theory. Chaos Solitons Fractals 158, 112030. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chaos.2022.112030 (2022).

Acknowledgements

The National Institutes of Health partially supported J.W. under grant number 1R15GM152943. The authors thank the two anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments, which have significantly improved the quality of the original manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Validation, Formal analysis, Investigation: Writing-original draft preparation: M.S.U.; Writing-review and editing: M.S.U. and J.W.; Supervision: Jin Wang. All authors have read and agreed to the submitted version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ullah, M.S., Wang, J. Revealing the complex dynamics of monkeypox epidemics in heterogeneous networks by the evolutionary game theory. Sci Rep 15, 29889 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-13220-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-13220-y