Abstract

The discharge of lead (Pb2+) from industries, which is harmful to water, human health and food chain, poses a serious risk. Due to the remarkable ability of ZnO biochar nanocomposite to remove Pb²⁺ from wastewater, it gained significant attention in environmental research. This study was conducted to determine how effectively the prepared ZnO-Biochar nanocomposite removed Pb²⁺ from wastewater. Fourier transmission infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) and scanning electron microscopy (SEM) were used to examine the functional groups and surface morphology of the ZnO-Biochar nanocomposite, respectively. The structure of ZnO-Biochar nanocomposite with rough and porous surface performed the positive association in surface adsorption of Pb²⁺ pollutant. A batch-experimentation conducted under a variety of conditions, including initial Pb²⁺ concentration (50–200 mg L⁻¹), adsorbent dosage (0.05–0.25 g), pH (2–12), and contact time (0–240 min) to evaluate the removal rates as well as adsorption capacities, within an emphasis on environmental impact. This study proves that ZnO-Biochar nanocomposite has a 90.30% removal rate for Pb²⁺. The ZnO-Biochar nanocomposite proved an impressive maximum adsorption capacity (qmax) of 79.302 mg/g, as determined through the implementation of the Langmuir model. A linear pseudo-first order and pseudo-second order model having R2 values of 0.867 and 0.899 respectively, show the best fit for the experimental data concerning Pb²⁺. Experiments conducted in this work demonstrate the exciting potential of the prepared material for promoting sustainable treatment of industrial wastewater.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The global economy, environment, and public health are at risk due to rising water pollution, which is a challenge on a global scale1. Because heavy metals are flexible, aggregate, persistent, and non-biodegradable, they pose a serious threat to the ecosystem when they contaminate land and aquatic areas2,3. This problem is exacerbated in developing countries by the rapid expansion of polluting businesses for a variety of uses, including tanneries, batteries, paper industries, mining, fertilizer, pesticides, and coke factories4. Due to the detrimental impact that heavy metals on a wide variety of living forms, scientists and engineers are particularly concerned about their removal5,6. Heavy metals have been found to come from geological, industrial, agricultural, pharmaceutical, household waste, and atmospheric sources7. Point source locations including mines, foundries, smelters, and other metal-based industrial processes are highly prevalent in terms of environmental contamination. Among all heavy metals, Pb²⁺ is a highly hazardous and garnered significant attention from environmentalists8. Lead is a bluish-gray metal that occurs naturally in trace amounts in the crust of the planet. Lead is found in the environment naturally, but human activities like burning fossil fuels, mining, and manufacturing cause significant concentrations to be released. There are several home, industrial, and agricultural uses for lead. Different industrial processes, including the production of storage batteries, glass and ceramics, mining, plating, coating, and automobiles, release Pb²⁺ into aquatic habitats. The widespread use of agricultural chemicals, including fertilizers and fungicidal sprays, is another possible cause of Pb²⁺ pollution9. The use of wastewater for irrigation is widespread worldwide, particularly in areas with limited supplies of freshwater10. The ecosystem and human health, however, could be severely harmed if such water contains lead. Moreover, lead can bio accumulate and bio-magnify in the food chain through crops, vegetables, and fruits that are ultimately consumed by people as a result of lead-contaminated irrigation effluent11,12. Pb²⁺ poisoning can also result in cancer, brain damage, severe harm to the liver, kidneys, central nervous system along with the abnormalities in the organs of living things13,14. Thus, wastewater should be properly treated in order to prevent lead and other pollutants from getting into the environment as well as the food chain. The US EPA and WHO set the highest pollution levels for Pb²⁺ in drinkable water at 15 and 50 µg L⁻¹, respectively15. As a result, several techniques for removing hazardous heavy metals from aqueous solutions while preserving environmental safety were developed, including chemical precipitation, ion exchange, membrane separation, adsorption, and electrochemical removal16. Among these, adsorption is one of the most extensively used methods. Adsorption is a physicochemical method involving the attachment of one material to another17. If there are no competing additives interfering, it offers excellent quality treated outputs, low running costs, great design, operational flexibility as well as removal efficiency18. To extract heavy metals from aqueous solutions, including arsenic (As), cadmium (Cd), nickel (Ni), mercury (Hg), chromium (Cr), zinc (Zn), and Pb, a variety of adsorbents are employed. Among these adsorbents are, carbon-based adsorbents19 bio-adsorbents20 low-cost adsorbents21 and polymeric nanosorbents22.Moreover, Pb²⁺ was extracted using a variety of adsorbents like activated carbon23 modified alginate aerogel with melamine/chitosan16, reduced graphene oxide-Fe3O49 and pea peel waste24.

The heavy metals in the wastewater can be removed through biochar, and it can help in wastewater handling, mitigation of water contamination, and sequestration of carbon as well25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32. Several studies investigated the use of biochar produced from a range of feed-stocks, including rice husk, pinewood, wood bark, cottonwood, and sugar cane bagasse, under various pyrolytic conditions in order to remove heavy metals including Cd, Pb, Ni, As, Hg, and Cr33,34,35,36. The process by which biochar adsorbs heavy metals from wastewater involves numerous mechanisms including metal precipitation, metal reduction followed by adsorption, cation exchange between metals and alkaline metals on the biochar surface, metal complexation with functional groups and π electron-rich domains of the charcoal37.

Given its benefits, which include availability, ease of use, resistance to substances that corrode, as well as significant inclination towards metal ions employed in wastewater treatment, it appears promising to use zinc oxide (ZnO) as adsorbents to remove various elements from wastewater38. Zinc oxide has good quantum efficiency and semi-conductive qualities because of its toxicity-free, thermally stable, porous micro-/nano-structure, strong adsorption capacity, broad band gap energy of 3.37 eV, high electron mobility, and exciton binding energy of 60 meV39.

A combination of biochar and nanomaterials has been produced by modifying through various processes, enhancing porosity, growing the amount of functional groups, and raising the surface-to-volume ratio for improving adsorption capacity40. Biochar injected with ZnO nanoparticles is a risk-free option for wastewater treatment. The application of ZnO-Biochar composites for the treatment of wastewater has shown encouraging results. Biosorption was used by Li et al.39 to purify maize stover, and then the residue was slightly pyrolyzed to produce nano-ZnO/ZnS-modified biochar. The resultant product’s porosity and roughness (SBET = 397.4 m2/g) significantly exceeded those of pure biochar (SBET = 102.9 m2/g). Nitric acid-functionalized charcoal was combined with zinc acetate dehydrate, a ZnO predecessor, in ethanol. After undergoing solvothermal treatment, a zinc-biochar composite was produced by nitrogen pyrolysis. This method yielded a material with a water contact angle of around 151°−156° by synthesizing ZnO nanoparticles with a wide size distribution and bonding them to a hydrophobic charcoal matrix17. In the literature, effective heavy metal removal utilizing ZnO nanoparticles and nanocomposites was documented41,42. However, a small number of research examined the Pb²⁺ adsorption capability and removal method onto ZnO-Biochar nanocomposite. This study has developed new composite material by combining ZnO with Biochar and comparing and examining the application of ZnO-Biochar nanocomposite for adsorption of Pb²⁺ from polluted water. It was looked at how Pb²⁺ removal was affected by pH, adsorbent dosages, contact time, and starting concentrations. Before as well as after the adsorption procedure, SEM and FTIR spectra were conducted to clarify the mechanisms involved. Pseudo-first order (PFO) and pseudo-second order (PSO) analysis was performed on the experiment results. Then, in order to identify the suitable isotherms for characterizing the behavior of Pb²⁺ adsorption on metal oxides, the equilibrium data were examined by employing a variety of isotherm models including Langmuir, Freundlich, as well as Tempkin.

Material and method

Chemicals, material and equipment

All reagents/chemicals of analytical grade were used in current research work and purchased from Sigma-Aldrich-Chemical-Co. (USA) and Merck-(Germany).To prepare the contaminated solution, lead nitrate (Pb (NO3)2) (CAS#10099-74-8, Sigma Aldrich) was utilized. In order to prevent Pb²⁺ from precipitating due to hydrolysis, 1.58 g of lead nitrate is dissolved in 1000 mL of deionized water containing 10% (v/v) of hydrochloric acid (HCl, CAS#7647-01-0, Sigma Aldrich) for a duration of 24 h. This yields a 1000 mg L−1 stock solution. By reducing the strength of this mixture as needed to obtain desired Pb²⁺ working solutions, other standard solutions were created.

Synthesis of Biochar based nanocomposites

Biochar based nanocomposite was synthesized by adding 10 g of sieved biochar to 250 mL conical flask. 0.1 g of required ZnO nanoparticles was prepared by dissolving it in 100 mL of DI water. The solution then added into the 250 mL conical flask containing biochar. The solution was vigorously stirred to ensure proper mixing, and then left overnight in an orbital shaker. The conical flask was removed after 12 h and given another 12 h to settle. After the nanocomposites had settled, the supernatant was extracted. The obtained composite was dried and grounded into fine powder form43.

Characterization

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) imaging was utilized to evaluate the physical morphology and structure of the synthesized ZnO-Biochar nanocomposite (Hitachi S-3000 N, Hitachi Scientific Instruments, Tokyo, Japan). Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) was used to classify the functional groups on biochar in the wavelength range of 4000 cm−1 to 300 cm−1 (using KBr pellet method with 0.4 cm−1 resolution in Perkin Elmer’s instrument).

Adsorption experiment

A number of batches were used in the adsorption tests, and in every batch, a particular parameter that influences the adsorption process was evaluated in order to find its ideal value within the measured range. The solution’s pH, the adsorbent dose, the duration of contact, and the initial Pb²⁺ concentration were the variables that investigated. By utilizing 0.1 M of hydrochloric acid (HCl, CAS#7647-01-0, Sigma Aldrich) and NaOH (CAS# 1310-73-, Sigma Aldrich) to change the solution pH between pH 2 and 12, the impact of pH was examined. The tested range of adsorbent dose was 0.05–0.25 g L⁻¹. Through a range of contact time, from 0 to 240 min, the impact of contact time was examined. Between 50 and 200 mg L⁻¹, the outcomes of the initial Pb²⁺ concentration were investigated. Solution flasks shaken at 125 rpm for every batch to make sure the mixture reached equilibrium, or maximal adsorption capacity. After centrifuging and filtration, UV Vis. spectroscopy (UV 1700, Shimadzu, Japan) analysis of the solution for adsorption/removal efficiency were performed for each batch. The filter paper (Whitman number 45.) used to screen out supernatent. Equations (1) and (2), respectively, can be utilized to get the adsorption capacity and the adsorption percentage44.

where Ci: initial concentration (mg L⁻¹); Ce: final concentration (mg L⁻¹); v: working solution volume (L); m: adsorbent quantity (g L⁻¹);

Statistical analysis

All the Model fitting was performed with Origin Lab Pro 10.5 (USA). The data presented in the bar plots is average of three replicates ± standard error shown in the form of error bars.

Result and discussion

Characterization

Using the SEM test, the morphology of the adsorbent’s surface was investigated; SEM images revealed changes in the adsorbents’ morphology both before to and after the adsorption process (see Fig. 1a & b). The SEM images (Fig. 1a) exhibited that ZnO-Biochar nanocomposite display rough, uneven surfaces with porous apertures prior to the adsorption process. After the adsorption process (Fig. 1b) the porous openings on ZnO-Biochar nanocomposite sites were occupied. The comparative assessment of the SEM images of ZnO-Biochar nanocomposite before as well as after Pb²⁺ adsorbed indicates that adsorption took place and shows a distinct change in the morphology. The structure of ZnO-Biochar nanocomposite with rough and porous surface performed the positive association in surface sorption of Pb²⁺ pollutant.

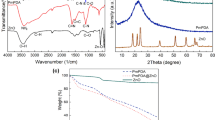

To identify functional groups fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy used with scan range between 4000 and 300 cm−1 using KBr pellet method. The FTIR spectra of ZnO-Biochar nanocomposite before as well as after adsorption process are presented in Fig. 2a & b. Pre-adsorption spectroscopy reveals that ZnO-Biochar nanocomposite has many infrared absorption peaks at different wavenumbers. The carbonaceous composition of ZnO-Biochar nanocomposite is shown by the presence of an absorption peak at 2919.78 cm−1, which is characteristic of C-H stretching vibrations in organic molecules. In addition, the peaks at 2850.5 cm−1 and 2355.38 cm−1 are indicative of aliphatic C-H bonds, while the signal at 2319.11 cm−1 might be due to carbonyl or nitrile groups. The chemical content and structure of ZnO Biochar nanocomposite may be deduced from its spectral absorption at 1923.01 cm−1, 1598.77 cm−1, 1387.94 cm−1, 1116.56 cm−1, 874.64 cm−1, and 384.11 cm−1, where each band represents a different functional group or vibration within the biochar structure45.

Adsorption modifies the ZnO-Biochar composite FTIR spectra significantly, with new peaks appearing at different wave-numbers. Adsorption-induced changes may lessen the strength of the peak at 349.82 cm−1, which is associated to mineral content. Interactions with adsorbates may cause shifts in the C-H stretching vibrations peak at 2919.78 cm−146. The peaks at 2850.5 cm−1, 2355.38 cm−1, and 2319.11 cm−1 may shift in strength due to adsorption processes, indicating changes in aliphatic C-H and other functional groups. The structural changes and chemical interactions that take place during the adsorption process, as revealed by the shifts or alterations in the peaks at 1923.01 cm−1, 1598.77 cm−1, 1387.94 cm−1, 1116.56 cm−1, 874.64 cm−1, and 384.11 cm−1, shed light on the efficacy of ZnO-Biochar as an adsorbent for particular contaminants.

Adsorption mechanisms

Adsorption is a process that has three controlling steps: (1) film diffusion is the process by which the adsorbate moves from the bulk liquid to the surrounding film of the adsorbent; (2) surface adsorption is the process by which the adsorbate moves from the film to the adsorbent surface.; and (3) the adsorbate moving to the internal active sites, which is called intraparticle diffusion47.

Using the experimental data from the SEM as well as FTIR results, the adsorption mechanism was examined. The adsorption process was identified as physisorption (Pb2+ ion attached on surface active sites through Vander Wal forces) because it obeyed the linear Langmuir model. Following kinetic modelling, the nonlinear pseudo-second-order model showed highest R2 value, which indicated that chemisorption was the reaction at play, explained by chemical equations in 3.3.2 section briefly. This was confirmed by the chemical bonding of Pb2+ species with surface functional groups on nanocomposite. Kinetic as well as isotherm modelling exhibited the combined chemisorption and physisorption processes occurred simultaneously. A notable alteration in the FTIR spectra was observed by comparing the pre- and post-adsorption FTIR spectra of the hexagonal ZnO-Biochar nanocomposite. After Pb²⁺ was adsorbed, the majority of the adsorption peaks underwent strength changes.

Adsorption studies

Effect of contact time

With an ideal pH of 5.5 and an adsorbent dose of 0.05 g, respectively, and 250 mL of contaminated solution, this group of studies was carried out at various contact time, specifically 0, 30, 60, 90, 120, 150, 180, 210, and 240 min. At a steady agitation speed of 125 rpm, the starting Pb²⁺ concentration was 100 mg L−1. After measuring the resultant Pb²⁺ concentration values, Eq. (1) used to determine the adsorption %. As shown in Fig. 3a, the highest removal efficiencies for ZnO-Biochar nanocomposite were 96.17% at a contact time of 120 min. It is evident that the first phase of Pb²⁺ adsorption was swift, followed by a gradual increase over time that reached nearly constant levels after 150 min. This phenomenon can be clarified by the first stage of adsorption having a great accessibility of free adsorption sites, which is followed by a rise in repulsive forces because of the adsorbed ions, increasing the difficulty of access to the remaining sites48,49. This conduct may be elucidated by the fact that there is a larger concentration of pollutant per mass of adsorbent, which could limit adsorption.

Effect of pH solution

The pH is one of the most crucial factors in the adsorption process because it can alter the properties of the metal in solution and the load on the surface of the active sites50.When heavy metal ions are present in an aqueous solution, pH influences various reactions, including dissociation, hydrolysis, complexation, and precipitation. Furthermore, pH has an impact on the availability and speciation of ions, which directly impacts the capacity for biosorption51. Since it influences metal ion speciation, the biosorbent’s surface chemistry, and adsorption efficiency, the pH of the biosorption process is crucial. Both the chemistry of the hazardous metals in the solution and the site dissociation of the biomass surface are significantly impacted by pH52. Six different pH values were studied, namely 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, and 12, with an initial adsorbent mass of 0.05 g and 250 mL of contaminated solution. It was investigated how the initial pH of the solution affected the amount of Pb²⁺ separate by adsorption. The mixture was continuously stirred at 125 rpm for 120 min. After measuring the final Pb²⁺ concentration values, Eq. (3.1) was used to determine the adsorption %. Figure 3b illustrates the optimal removal efficiency of 94.66% for ZnO-Biochar nanocomposite at a pH of 5.5, which is in line with previous research findings6,49,53. When the starting pH of the solution rose from pH 3.0- pH 7.0 for the adsorbent utilized, the adsorption % increased. The metal ions’ electrostatic attraction (ion exchange) with the adsorbent surface most likely increased as the adsorbent surface got more negatively charged. The rise in the percentage of adsorption can be explained by Pb2+, Pb(OH)+, as well as Pb(OH)2 interacting with the functional groups on the adsorbent surface through hydrogen bonding or ion exchange54 as shown in Fig. 3b and the following reactions:

Ion exchange mechanism:

Hydrogen bonding:

The development of soluble hydroxyl complexes in ZnO-Biochar nanocomposite was found to cause a decline in the adsorption percentage at higher pH values (7.0–9.0). More Pb2+ cations can be adsorbed because surface of the adsorbent becomes less positively charged as the pH of the solution rises. A pH of 5.5 is ideal for the batches that come after. The adsorption efficiency decreases below this ideal value due to struggle between Pb2+ ions and H3O+, whereas higher pH levels cause lead species to hydrolyze, promoting precipitation and inhibiting quantitative adsorption. The plenty of active sites for attachment of Pb2+ on the surface of ZnO-Biochar nanocomposite may be to blame as the pollutant species must interact with active sites on the sorbent surface55. The adsorption capacity of Pb2+ eventually decreases, however, since all of the adsorption sites on the combined sorbent are already occupied.

Effect of adsorbent dosage

Various adsorbent concentrations (0.05, 0.01, 0.15, 0.20, and 0.25 g) were used in this batch of trials, along with 250 mL of the contaminated solution, all at the ideal starting pH value. Shaking the initial Pb²⁺ concentration for 120 min at 125 rpm was the constant speed of stirring. After measuring the final Pb²⁺ concentration, the adsorption % was computed using Eq. (1). According to Fig. 3c, the highest removal effectiveness of 95.27% for ZnO-Biochar nanocomposite was obtained at a similar adsorbent dosage of 0.05 g. With an increase in adsorbent dosages from 0.05 to 0.25 g for each adsorbent utilized, the adsorption percentage upsurges. According to these results, the adsorption process has more active binding sites when the adsorbent dose is increased from 0.05 to 0.25 g56,57. The decrease in molecular competition for active binding sites results in an increase of Pb²⁺ ions adsorbed onto the adsorbent’s surface. For use in the ensuing batches, the best dose was found to be 0.05 g.

Effect of initial concentration of pb²⁺

Several starting Pb²⁺ concentrations (mg L⁻¹) were used in this batch, along with the ideal pH and adsorbent dosage that were discovered from earlier batches using 250 mL of tainted solution. The mixture was continuously stirred at 125 rpm for 120 min. Equation (1) was utilized to compute the adsorption % after the final Pb²⁺ concentration values were measured. Figure 3d illustrates that at an initial concentration of 100 mg L⁻¹ for adsorbent, the maximum removal efficiency for ZnO-Biochar nanocomposite was 96.17%. According to the findings, there is a positive correlation among the initial Pb²⁺ concentration as well as the percentage of Pb²⁺ removal through adsorption up to a certain point. Once the initial Pb²⁺ concentration reaches 150 mg L−1, the percentage of Pb²⁺ elimination starts to decrease. This may be explained as follows: for a given quantity of adsorbent, the high initial Pb²⁺ concentration results in an excess of accessible particles on the adsorbent surface in relation to the active binding site, which lowers the percentage of Pb²⁺ removal by adsorption.

Kinetic studies

Adsorption kinetics can be used to forecast how quickly Pb²⁺ ions will be absorbed from the water. Pseudo-first order (PFO) and pseudo-second order (PSO) mathematical models were employed to fit the adsorption rate using Pb²⁺ adsorption data at various contact times. Table 1 below expresses the PFO model and PSO model equation.

here t denotes time, qt refers to the amount adsorbed t time (mg/g), qe represents the equilibrium adsorption capacity (mg/g), K1 is a constant of pseudo-first-order kinetic model and K2 is a constant of pseudo-second-order kinetic model. The slope of the linear plot of ln (qe-qt) vs. t (Fig. 4a) was used to obtain K1, and the slope of the linear plot of t/qt vs. t (Fig. 4b) was used to calculate the values of K2 and qe. With a correlation coefficient (R2 of 0.89925 against the adsorption findings, the PSO model outperformed the PFO model (R2 = 0.867), indicating that the PSO model offers the most precise explanation of the adsorption process’ kinetics. This additionally proved that the rate-limiting step in the reaction was chemisorption59,60 as shown in Fig. 4a & b. Table 2 provides a summary of these models’ kinetic parameters.

Equilibrium isotherms

The equilibrium relationship among the solid phase as well as the concentration of the liquid phase solution is known as an isotherm. Adsorption isotherms are useful for examining an adsorbent’s suitability for pollutant extraction, and they may also be used to check the maximal adsorption capacity through a variety of mathematical formulas such as Langmuir61 Freundlich62 Tempkin63.

These are the isotherms that are most frequently employed to characterize systems of solid-liquid adsorption. Mathematical forms of models given in Table 3.

In the above equations, qmax(mg/g) is the adsorbent’s maximal monolayer adsorption ability; KL (L/mg) Langmuir constant linked to the attraction between a adsorbent and an adsorbate; and RL stands for separation factor; Kf (mg/g or L/mg) Freundlich constant which quantifies adsorption strength; and n (dimensionless) stands for Freundlich parameter. AT Tempkin equilibrium binding constant (L/g), bT Tempkin constant, R stands for universal gas constant (8.314 J/mol/K), and T stands for temperature (298 K).

Figure 5a-c show the experimental results shown using the linearized form of the aforementioned isotherm models. Regarding the circumstances under which adsorption occurs, each isotherm makes particular assumptions. Although Langmuir isotherm supposes maximum limiting adsorption at a given number of available sites on surface, with the same energy available at all adsorption sites, Freundlich model adsorption supposes that adsorption occurs on a heterogeneous surface through multilayer adsorption processes65,66. The Tempkin isotherm makes the assumption that when the adsorbent’s surface is covered, the adsorption heat drops linearly. We calculated the conforming correlation coefficients (R2 for every absorbent. Tempkin constant BT (10.408 J/mol) is positive, indicating that the adsorption process is exothermic67. This means that heat is released during the adsorption of Pb ions onto the ZnO-Biochar nanocomposite.The Tempkin isotherm constant KT (2.147 L/mg) represents the binding energy between the adsorbent and the adsorbate. The higher the value of KT, the stronger the binding energy. The linear Langmuir model for Pb²⁺ has the highest R2 value of 0.95 and provides the greatest match to the data (Fig. 5a). Because of the uniform dispersal of active sites on the surfaces of the biochar sample, it is possible that the interactions between Pb²⁺ as well as the adsorbents are primarily associated to mono-layer adsorption, as indicated by the Langmuir model’s prediction of the maximum adsorption (qmax) for Pb²⁺ of 79.30 (Table 4).

Regeneratiin studies of ZnO-BC nanocomposite

The regeneration capability of an adsorbent is a significant characteristic, as the prepared adsorbent exhibited high efficiency in adsorbing Pb²⁺. Figure 6 compares the desorption efficiencies of two reagents, revealing that 0.1 M NaOH outperformed 0.1 M HCl, achieving a desorption efficiency of 76.278%. As a result, 0.1 M NaOH was chosen as the desorbing agent, enabling the nanocomposite to be reused for subsequent adsorption cycles. Figure 7 displays the regeneration cycles of the ZnO-Biochar composite after desorption with 0.1 M NaOH for Pb²⁺ removal from a 100 mL solution. The nanocomposite was reused over five cycles, with its adsorption efficiency declining from 84.565% in the first cycle to 54.055% by the fifth cycle. These findings underscore the excellent re-usability of the ZnO-Biochar nanocomposite. The desorption efficiency was calculated using Eq. 5 (Figs. 6 and 7).

In the given equation, Vd stands for the volume of the desorbing agent (mL), Cd refers to the pollutant concentration after desorption (mg L⁻¹), and Ci and Ce represent the initial and equilibrium concentrations of the pollutant after adsorption (mg L⁻¹) respectively.

Conclusions

This study used a ZnO-Biochar nanocomposite to do a thorough investigation of Pb²⁺ removal by adsorption. SEM and FTIR analysis were utilized to evaluate the morphological and functional groups of the adsorbent. The SEM pictures demonstrated how permeable the pores were on ZnO-Biochar nanocomposite’s surfaces. Adsorption was verified by modifications in the morphologies of the adsorbents before and after experimentation. Studies were conducted on the effects of solution pH, adsorbent dosage, contact time, as well as the initial concentrations on the efficacy of adsorption and removal. Separate batch tests were used to determine the ideal values for these parameters. The best conditions for ZnO-Biochar nanocomposite, the adsorbent under consideration, were at pH 5.5, which gave the removal efficiency of 94.66%. Moreover, the highest removal efficiency of 96.17% was obtained at an initial concentration of 100 mg L⁻¹ for a contact time of 120 min, while the adsorbent dosage of 0.05 g gave a removal effectiveness of 95.27%. Following the application of the adsorbent’s ideal values for the researched adsorption parameters, the adsorption kinetics were examined using a variety of models, including PFO and PSO, with PSO providing the best match for the adsorption of lead with an R2 value of 0.89925. The adsorption isotherms were also examined at equilibrium. The outcome demonstrated that the ZnO-Biochar nanocomposite’s adsorption of Pb²⁺ was best characterized by the Langmuir isotherm model, which had an R2 value of 0.9564. In summary, ZnO-Biochar nanocomposite is the most effective material for adsorptive lead removal from aqueous solutions under the ideal circumstances used in this investigation.

Future perspectives

An effective adsorbent material has been developed and described in this work. The experimental results showed a high level of adsorption efficiency. This study can be used as a good filtration system for industrial wastewater treatment. Because of metal ions’ competition with regard to adsorption sites in actual contaminated waters, the presence of several metal pollutants may reduce the adsorption of a single metal element relative to the others. Investigations involving the competitive adsorption of different metals must be taken into consideration to assess the genuine adsorption behavior of the nanoadsorbents.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Schwarzenbach, R. P., Egli, T., Hofstetter, T. B., Von Gunten, U. & Wehrli, B. Global water pollution and human health. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 35, 109–136 (2010).

Forghani, M., Azizi, A., Livani, M. J. & Kafshgari, L. A. Adsorption of lead (II) and chromium (VI) from aqueous environment onto metal-organic framework MIL-100 (Fe): synthesis, kinetics, equilibrium and thermodynamics. J. Solid State Chem. 291, 121636 (2020).

Mousavi, S. V. et al. A novel cyanopropylsilane-functionalized titanium oxide magnetic nanoparticle for the adsorption of nickel and lead ions from industrial wastewater: equilibrium, kinetic and thermodynamic studies. Microchem. J. 145, 914–920 (2019).

Elawwad, A., Naguib, A. & Abdel-Halim, H. Modeling of phenol and cyanide removal in a full-scale coke-oven wastewater treatment plant. Desalination Water Treat. 57, 25181–25193 (2016).

Mahmud, H., Hosseini, S. & Yahya, R. Polymer adsorbent for the removal of lead ions from aqueous solution. Int. J. Tech. Res. Appl. 11, 04–08 (2014).

Mohammadi, S. Z., Karimi, M. A., Afzali, D. & Mansouri, F. Removal of Pb (II) from aqueous solutions using activated carbon from Sea-buckthorn stones by chemical activation. Desalination 262, 86–93 (2010).

He, Z. L., Yang, X. E. & Stoffella, P. J. Trace elements in agroecosystems and impacts on the environment. J. Trace Elem. Med Biol. 19, 125–140 (2005).

Raza, H. Z. et al. Calcium oxide nanoparticles mitigate lead stress in Abelmoschus esculentus though improving the key antioxidative enzymes, nutritional content and modulation of stress markers. Plant. Physiol. Biochem. 206, 108171. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.plaphy.2023.108171 (2024).

Ghorbani, M., Seyedin, O. & Aghamohammadhassan, M. Adsorptive removal of lead (II) ion from water and wastewater media using carbon-based nanomaterials as unique sorbents: A review. J. Environ. Manage. 254, 109814 (2020).

Bixio, D. et al. Wastewater reuse in Europe. Desalination 187, 89–101 (2006).

Khan, A. H. A. et al. Reduced growth response of ornamental plant Nicotiana Alata L. upon selected heavy metals uptake, with co-application of Ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid. Chemosphere 241, 125006 (2020).

Shah, A. A. et al. Fullerenol nanoparticles and AMF application for optimization of brassica Napus L. resilience to lead toxicity through physio-biochemical and antioxidative modulations. Sci. Rep. 14, 30992. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-82086-3 (2024).

Mehdinia, A., Heydari, S. & Jabbari, A. Synthesis and characterization of reduced graphene oxide-Fe3O4@ polydopamine and application for adsorption of lead ions: isotherm and kinetic studies. Mater. Chem. Phys. 239, 121964 (2020).

Yang, H. et al. Efficient and rapid removal of Pb2 + from water by magnetic Fe3O4@ MnO2 core-shell Nanoflower attached to carbon microtube: adsorption behavior and process study. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 563, 218–228 (2020).

Mahmud, H. N. M. E. & Huq, A. O. Binti yahya, R. The removal of heavy metal ions from wastewater/aqueous solution using polypyrrole-based adsorbents: a review. RSC Adv. 6, 14778–14791 (2016).

Zhang, Y. et al. Production of activated carbons from four wastes via one-step activation and their applications in Pb2 + adsorption: insight of Ash content. Chemosphere 245, 125587 (2020).

Wang, Y. Y., Liu, Y. X., Lu, H. H., Yang, R. Q. & Yang, S. M. Competitive adsorption of Pb (II), Cu (II), and Zn (II) ions onto hydroxyapatite-biochar nanocomposite in aqueous solutions. J. Solid State Chem. 261, 53–61 (2018).

El Ouardi, M. et al. Efficient removal of p-nitrophenol from water using montmorillonite clay: insights into the adsorption mechanism, process optimization, and regeneration. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 26, 19615–19631 (2019).

Al-Khaldi, F. A. et al. Adsorptive removal of cadmium (II) ions from liquid phase using acid modified carbon-based adsorbents. J. Mol. Liq. 204, 255–263 (2015).

Bilal, M., Ihsanullah, I., Younas, M. & Shah, M. U. H. Recent advances in applications of low-cost adsorbents for the removal of heavy metals from water: A critical review. Sep. Purif. Technol. 278, 119510 (2021).

Uddin, M. K. A review on the adsorption of heavy metals by clay minerals, with special focus on the past decade. Chem. Eng. J. 308, 438–462 (2017).

Ge, F., Li, M. M., Ye, H. & Zhao, B. X. Effective removal of heavy metal ions Cd2+, Zn2+, Pb2+, Cu2 + from aqueous solution by polymer-modified magnetic nanoparticles. J. Hazard. Mater. 211, 366–372 (2012).

Thabede, P. M., Shooto, N. D. & Naidoo, E. B. Removal of methylene blue dye and lead ions from aqueous solution using activated carbon from black Cumin seeds. S. Afr. J. Chem. Eng. 33, 39–50 (2020).

Novoseltseva, V., Yankovych, H., Kovalenko, O., Václavíková, M. & Melnyk, I. Production of high-performance lead (II) ions adsorbents from pea peels waste as a sustainable resource. Waste Manag. Res. 39, 584–593 (2021).

Mansoor, S. et al. Biochar as a tool for effective management of drought and heavy metal toxicity. Chemosphere 271, 129458 (2021).

Qiu, B. et al. Biochar as a low-cost adsorbent for aqueous heavy metal removal: A review. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrol. 155, 105081 (2021).

Li, Y., Yu, H., Liu, L. & Yu, H. Application of co-pyrolysis Biochar for the adsorption and immobilization of heavy metals in contaminated environmental substrates. J. Hazard. Mater. 420, 126655 (2021).

Kumar, P. S., Gayathri, R. & Rathi, B. S. A review on adsorptive separation of toxic metals from aquatic system using Biochar produced from agro-waste. Chemosphere 285, 131438 (2021).

Boraah, N., Chakma, S. & Kaushal, P. Attributes of wood Biochar as an efficient adsorbent for remediating heavy metals and emerging contaminants from water: a critical review and bibliometric analysis. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 10, 107825 (2022).

Liu, M. et al. A critical review of biochar-based materials for the remediation of heavy metal contaminated environment: applications and practical evaluations. Sci. Total Environ. 806, 150531 (2022).

Ahmad, M. et al. Biochar as a sorbent for contaminant management in soil and water: a review. Chemosphere 99, 19–33 (2014).

Tan, X. et al. Application of Biochar for the removal of pollutants from aqueous solutions. Chemosphere 125, 70–85 (2015).

Karunanayake, A. G. et al. Lead and cadmium remediation using magnetized and nonmagnetized Biochar from Douglas Fir. Chem. Eng. J. 331, 480–491 (2018).

Brar, J. S., Sikka, R., Singh, D. & Kalia, A. Effect of nanoparticles of rice husk Ash on the bioavailability of lead to Indian mustard (Brassica juncea) in lead spiked soil. Agric. Res. J. 55, 478–484 (2018).

Qian, L., Chen, M. & Chen, B. Competitive adsorption of cadmium and aluminum onto fresh and oxidized biochars during aging processes. J. Soils Sediments. 15, 1130–1138 (2015).

Inyang, M., Gao, B., Zimmerman, A., Zhang, M. & Chen, H. Synthesis, characterization, and dye sorption ability of carbon nanotube–biochar nanocomposites. Chem. Eng. J. 236, 39–46 (2014).

Li, H. et al. Mechanisms of metal sorption by biochars: Biochar characteristics and modifications. Chemosphere 178, 466–478 (2017).

Arora, R. Adsorption of heavy metals–a review. Mater. Today: Proc. 18, 4745–4750 (2019).

Li, C., Zhang, L., Gao, Y. & Li, A. Facile synthesis of nano zno/zns modified Biochar by directly pyrolyzing of zinc contaminated corn Stover for Pb (II), Cu (II) and cr (VI) removals. Waste Manage. 79, 625–637 (2018).

Thi Luyen, N. et al. Facile one-step pyrolysis of zno/biochar nanocomposite for highly efficient removal of methylene blue dye from aqueous solution. ACS Omega. 8, 26816–26827 (2023).

Gu, M. et al. The selective heavy metal ions adsorption of zinc oxide nanoparticles from dental wastewater. Chem. Phys. 534, 110750 (2020).

Saad, A. H. A., Azzam, A. M., El-Wakeel, S. T. & Mostafa, B. B. Abd El-latif, M. B. Removal of toxic metal ions from wastewater using zno@ Chitosan core-shell nanocomposite. Environ. Nanatechnol. Monit. Manage. 9, 67–75 (2018).

Sharma, M. et al. Green synthesis of silver–soil nanocomposite from two different sources and its application for the removal of dye solution. Environ. Pollut Prot. 1, 55–68 (2016).

Cooney, D. O. Adsorption Design for Wastewater Treatment (CRC, 1998).

Gupta, V. et al. Study on the removal of heavy metal ions from industry waste by carbon nanotubes: effect of the surface modification: a review. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 46, 93–118 (2016).

Zhang, T. et al. Efficient removal of lead from solution by celery-derived biochars rich in alkaline minerals. Bioresour. Technol. 235, 185–192 (2017).

SenthilKumar, P. et al. Adsorption equilibrium, thermodynamics, kinetics, mechanism and process design of zinc (II) ions onto cashew nut shell. Can. J. Chem. Eng. 90, 973–982 (2012).

Guo, J. et al. Preparation and characterization of nanoporous activated carbon derived from Prawn shell and its application for removal of heavy metal ions. Materials 12, 241 (2019).

Huang, Y., Li, S., Chen, J., Zhang, X. & Chen, Y. Adsorption of Pb (II) on mesoporous activated carbons fabricated from water hyacinth using H3PO4 activation: adsorption capacity, kinetic and isotherm studies. Appl. Surf. Sci. 293, 160–168 (2014).

Moreira, S. A., Sousa, F. W., Oliveira, A. G., Nascimento, R. F. & Brito, E. S. d. Remoção de metais de Solução Aquosa Usando Bagaço de Caju. Quím. Nova. 32, 1717–1722 (2009).

Ofomaja, A. E. & Ho, Y. S. Effect of pH on cadmium biosorption by coconut Copra meal. J. Hazard. Mater. 139, 356–362 (2007).

Zafar, M. N. et al. Characterization of chemically modified biosorbents from rice Bran for biosorption of Ni (II). J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. Eng. 46, 82–88 (2015).

Alawa, B., Srivstava, J., Srivastava, A. & Palsania, J. Adsorption of heavy metal Pb (II) from synthetic waste water by polypyrrole composites. Int. J. Chem. Stud. 3, 04–08 (2015).

Taty-Costodes, V. C., Fauduet, H., Porte, C. & Delacroix, A. Removal of cd (II) and Pb (II) ions, from aqueous solutions, by adsorption onto sawdust of Pinus sylvestris. J. Hazard. Mater. 105, 121–142 (2003).

Chauhan, A. K., Kataria, N. & Garg, V. Green fabrication of ZnO nanoparticles using Eucalyptus spp. Leaves extract and their application in wastewater remediation. Chemosphere 247, 125803 (2020).

Li, Y. et al. Removal of lead from aqueous solution by activated carbon prepared from enteromorpha prolifera by zinc chloride activation. J. Hazard. Mater. 183, 583–589 (2010).

Gupta, V. & Rastogi, A. Biosorption of lead from aqueous solutions by green algae spirogyra species: kinetics and equilibrium studies. J. Hazard. Mater. 152, 407–414 (2008).

Smičiklas, I., Onjia, A., Raičević, S., Janaćković, Đ. & Mitrić, M. Factors influencing the removal of divalent cations by hydroxyapatite. J. Hazard. Mater. 152, 876–884 (2008).

Saeed, M. et al. Calotropis gigantea leaves assisted biosynthesis of ZnO and ag@ ZnO catalysts for degradation of Rhodamine B dye in aqueous medium. Environ. Prog. Sustain. Energy. 39, e13408 (2020).

Dhiman, V., Kondal, N. Z. O. & Nanoadsorbents A potent material for removal of heavy metal ions from wastewater. Colloid Interface Sci. Commun. 41, 100380 (2021).

Langmuir, I. The adsorption of gases on plane surfaces of glass, mica and platinum. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 40, 1361–1403 (1918).

Freundlich, H. Über die adsorption in lösungen. Z. Für Phys. Chem. 57, 385–470 (1907).

Temkin, M. J. & Pyzhev, V. Recent modifications to Langmuir isotherms. (1940).

Hameed, B. & Rahman, A. Removal of phenol from aqueous solutions by adsorption onto activated carbon prepared from biomass material. J. Hazard. Mater. 160, 576–581 (2008).

Fierro, V., Torné-Fernández, V., Montané, D. & Celzard, A. Adsorption of phenol onto activated carbons having different textural and surface properties. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 111, 276–284 (2008).

Tran, H. N., You, S. J., Hosseini-Bandegharaei, A. & Chao, H. P. Mistakes and inconsistencies regarding adsorption of contaminants from aqueous solutions: a critical review. Water Res. 120, 88–116 (2017).

Febrianto, J. et al. Equilibrium and kinetic studies in adsorption of heavy metals using biosorbent: a summary of recent studies. J. Hazard. Mater. 162, 616–645 (2009).

Acknowledgements

The authors extend their appreciation to Ongoing Research Funding program - Research Chairs (ORF-RC-2025-5506), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Funding

This research article was funded by Ongoing Research Funding program - Research Chairs (ORF-RC-2025-5506), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

HM; Experimentation and Methodology, KH; Supervision and Validation, UG & QA; writing-original draft preparation and Statistical analysis, AAS & SS; Data curation and Formal analysis and SU & HOE; Resource acquisition and Investigation. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

We declare that the manuscript reporting studies do not involve any human participants, human data or human tissues. So, it is not applicable.

Our experiment follows with the relevant institutional, national, and international guidelines and legislation.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Mudassar, H., Hina, K., Ghani, U. et al. Adsorptive removal of Pb2+ from wastewater using ZnO-Biochar nanocomposite. Sci Rep 15, 29517 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-13228-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-13228-4