Abstract

Ocular imaging and fluid protein levels are emerging as biomarkers for neurodegenerative disease. Elevated levels of plasma glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP), a marker of astrogliosis, have been demonstrated early in the course of Alzheimer’s Disease. In this study, we measured GFAP levels in the aqueous and vitreous humors and plasma of 79 participants undergoing vitrectomy surgery for retinal disease and correlated them with subject Mini Mental Status Exam (MMSE) and Trail Making Test part b (TMT-b) scores. Measured GFAP concentrations were higher in vitreous and aqueous than in plasma. Levels of GFAP within the aqueous and vitreous were correlated (r = 0.6; p < 0.0001); however, there was no association between GFAP levels in either ocular fluid and plasma. There was no significant correlation between GFAP levels in any of the measured ocular fluids and cognition as measured by MMSE and TMT-b scores. In plasma, higher GFAP levels were associated with lower TMT-b, but not MMSE, scores. Given that elevated GFAP levels are associated with a variety of vitreoretinal diseases, future studies evaluating its use as a potential biomarker for dementias should concentrate on recruiting subjects without a history of ocular disease.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Alzheimer’s Disease (AD), the most common cause of dementia, is characterized by the accumulation of amyloid beta (Aβ) plaques and neurofibrillary hyperphosphorylated Tau (p-Tau) tangles in the brain. In response to Aβ plaque accumulation, surrounding glial cells including astrocytes are activated, a process known as reactive astrogliosis1. This process is characterized by cellular hypertrophy and upregulation of the expression of glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP), an intermediate filament structural protein found in central nervous system (CNS) astrocytes2,3. In light of evidence that astrogliosis occurs early in the pathogenesis of AD4, measurement of elevated GFAP levels would appear an attractive target for timely disease diagnosis. Indeed, plasma GFAP levels are elevated not only in AD patients5,6, but also in cognitively normal adults considered at high risk for AD development due to high brain Aβ load7.

Since the eye and brain share a common embryologic origin, recent research has focused on the potential measurement of biomarkers in ocular fluids including vitreous and aqueous to assist in the diagnosis of neurodegenerative diseases. Previous publications from our group have quantified levels of Aβ40, Aβ42, p-Tau, total tau (t-Tau), and neurofilament light chain (NfL) in the vitreous humor8,9,10,11. While Fekrat et al. recently reported a correlation between plasma and aqueous p-Tau181 levels as well as an inverse relation of the biomarker with cognitive function12, a previous study by Bai et al. failed to find a correlation between aqueous GFAP levels and cognition13. The goal of this investigation is to assess the relationship of plasma, aqueous, and vitreous GFAP levels and to evaluate for a potential association with cognitive function based on Mini Mental Status Exam (MMSE) and Trail Making Test part b (TMT-b).

Methods

This prospective, cross-sectional cohort study was conducted at Boston University Medical Center (BUMC). The study was carried out in accordance with the ethical standards of the Committee on Human Experimentation of our institution and the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the BUMC Institutional Review Board (study reference number H37370).

Study inclusion criteria included subjects aged 18 years or older with a primary language of English or Spanish requiring pars plana vitrectomy (PPV) for retinal disease including rhegmatogenous retinal detachment (RRD), macular hole (MH), epiretinal membrane (ERM), and complications of diabetic retinopathy (DR). Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects who participated in the study. Cognitive function tests of MMSE and TMT-b were performed within a month from the surgery.

Demographic data including age, sex, self-declared ethnicity, highest educational level completed, athletic and military history were compiled through a patient questionnaire in conjunction with review of patients’ electronic medical records. Clinical information including medical and smoking history, history of head and/or neck injuries, subjective cognitive complaints, individual and family ocular disease history, and family history of cognitive dysfunction were also collected.

Biospecimen collection

Aqueous samples were collected through the limbus prior to initiating a pars plana vitrectomy using a 1 cc syringe and 30-gauge hypodermic needle to aspirate 100–150 µl of undiluted aqueous. Balanced salt solution was used to reform the anterior chamber. Vitreous samples were collected with 0.5–1.0 mL of undiluted vitreous aspirated into an attached sterile 3-mL syringe using the vitrectomy probe. Infusion of balanced salt solution into the vitreous cavity was immediately undertaken to re-pressurize the eye. The syringes containing both eye fluid specimens were capped using sterile technique and directly handed to a member of the research team who labeled them with a predetermined non-identifiable study number and placed the samples on ice. Vitreous and aqueous fluid were centrifuged for 15 min at 12,000 rpm to separate the cellular contents, divided into 100μl aliquots, and frozen at – 80 °C. Aside from the collection of the vitreous and aqueous samples, each study participant’s vitrectomy was completed according to the clinical standard of care for that patient’s ocular condition.

Blood samples were collected on separate clinical visits from all study participants within 1–2 months of surgery. For the blood samples, approximately 18 ml of whole blood was drawn from each patient into EDTA-treated purple top tubes. The de-identified blood samples were processed into their serum, plasma, and buffy coat components.

Immunoassay measurements

GFAP concentrations in plasma, aqueous, and vitreous were measured using the combined Neurology 2-Plex B assay (#103520, Quanterix, MA) with a fourfold dilution for vitreous and plasma and an eightfold dilution for aqueous samples. All samples were processed per manufacturer’s instructions in the immunoassay kits.

Statistical analysis

Prior to subject enrollment, a power calculation was performed based on literature review and preliminary data from our group’s Vitreous Biomarkers Study, which provided estimates of biomarker variability. The calculation assumed an effect size of 1 and a significance level of 0.05. The analysis demonstrated that a sample size of at least 60 was sufficient to achieve adequate power to detect differences in correlation of cognition and protein biomarkers, thereby minimizing concerns related to an underpowered study.

The level and spread of GFAP within each biofluid was summarized by reporting means, medians, and interquartile ranges (IQR). To account for the possibility that previous intraocular surgeries might affect protein levels, we conducted a non-parametric Kruskal–Wallis test to evaluate for a potential difference in ocular fluid GFAP levels in phakic versus pseudophakic eyes. Due to the skewness in the distribution, we used nonparametric Spearman’s rank rho correlation coefficient to assess the relationship among the relative concentration of GFAP in plasma, aqueous and vitreous. We used Bland–Altman analysis to quantify the agreement of GFAP levels between plasma and the ocular fluids.

Linear regression analysis was performed to test associations among GFAP levels and continuous MMSE and TMT-b number scores. GFAP levels were log transformed for comparison to fit the skewed distributions for the regression. Additional analysis of MMSE and TMT-b scores was performed by separating subjects into “Normal” and “Abnormal” groups, with “Abnormal” defined as either log transformed MMSE score ≥ 1.5 standard deviations below the mean or as TMT-b z-score < − 1.5 respectively. Analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) was used to assess the correlation between GFAP levels and categorical MMSE and TMT-b scores in these groups. All analyses accounted for the covariates of age, sex, and apolipoprotein E (APOE) ε4 allele number and the Benjamini & Hochberg method14 was applied to control for multiple comparisons. p-values less than or equal to 0.05 were regarded as statistically significant.

Results

We enrolled 79 participants in the initial cohort. Of the 79 participants undergoing vitrectomy surgery, we collected adequate volumes of vitreous, aqueous, and plasma for GFAP testing in 78, 41, and 67, respectively. Various issues including challenges with specimen collection, subject refusal of blood draws, and inadequate sample volumes contributed to missing samples. Demographics of the full 79 subject cohort are displayed in Table 1.

GFAP levels were measurable in all sample types, with mean concentrations higher in vitreous (17,500 ± 21,300 pg/ml) and aqueous (2350 ± 4320 pg/ml) than in plasma (120 ± 74 pg/ml) (Table 2). We found no association between GFAP levels in either ocular fluid and plasma but a significant correlation between measured levels in aqueous and vitreous (r = 0.6; p < 0.0001) (Table 3). We found no significant difference in vitreous (p = 0.10) or aqueous (p = 0.09) GFAP levels when comparing phakic and pseudophakic eyes.

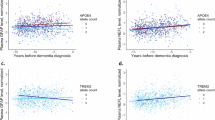

Complete MMSE and TMT-b were performed for 65 of 79 (82.3%) subjects, including 57 of 78 (73.1%) of those with an adequate vitreous sample, 30 of 41 (73.2%) with an aqueous sample, and 56 of 67 (83.4%) with an adequate blood sample. In plasma, we found that higher GFAP levels were significantly associated with lower TMT-b but not MMSE scores. In vitreous or aqueous, we found no significant relationship between GFAP levels and MMSE or TMT-b scores measured as continuous variables after adjustment for age, sex, and APOE ε4 for the total cohort (Fig. 1). We additionally found no significant difference in vitreous or aqueous GFAP levels when comparing the “Normal” and “Abnormal” MMSE or TMT-b score groups, whereas in plasma “Abnormal” TMT-b, but not MMSE, was significantly associated with elevated GFAP levels (Fig. 2).

Association between log transformed GFAP levels and continuous MMSE (top) and TMT-b (bottom) scores in plasma, aqueous, and vitreous. Analyses are adjusted for age, sex, and APOE ε4 allele genotype. (MMSE: Mini Mental Status Exam; TMT-b: Train Making Test part b; GFAP: Glial Fibrillary Acidic Protein;* statistically significant p value).

Comparison of log transformed GFAP levels and categorical cognitive scores: (A) MMSE scores (B) TMT-b z-scores in plasma, aqueous, and vitreous. Analyses are adjusted for age, sex, and APOE ε4 allele genotype. (MMSE: Mini Mental Status Exam; TMT-b: Train Making Test part b; GFAP: Glial Fibrillary Acidic Protein;* statistically significant p value).

Discussion

In this study we detected a significant correlation between aqueous and vitreous humor GFAP concentrations in individuals undergoing vitrectomy surgery for retinal disease. We did not find, however, a significant association between ocular fluid and plasma GFAP levels nor did we find significant associations between GFAP levels in any of the tested biofluids and cognitive status as measured by MMSE. Notably, we found that lower or abnormal TMT-b scores were associated with elevated GFAP levels in plasma but not in any of the ocular fluids.

A wealth of recent research has focused on the use of ocular biomarkers for the potential detection of neurodegenerative disease. Imaging studies using fundus photography have investigated associations between retinal vascular parameters such as vessel caliber and branching density and AD15, and deep learning models capable of detecting AD and other forms of cognitive impairment from fundus photographs have been developed16,17. High resolution optical coherence tomography (OCT) images have identified thinning of the inner retinal layers18 and choroid19 in individuals with AD, and OCT angiography devices have further elucidated retinal vascular changes such as enlargement of the foveal avascular zone in preclinical AD20. Testing of ocular fluids has revealed measurable levels of multiple potential biomarkers including Aβ40, Aβ42, Aβ1-40, t-Tau, p-Tau, and NFL with potential associations with cognitive function11,21,22.

Since approved monoclonal antibody treatments for AD potentially slow the progression of symptoms but do not reverse the disease process, it is important that new diagnostic strategies identify the disease early in its course prior to significant cognitive decline. Measurement of plasma GFAP levels offers the potential for early diagnosis including in preclinical AD and mild cognitive impairment (MCI)23,24. Plasma GFAP levels have also been shown to correlate with degree of cognitive impairment, supporting a potential role as a measure of disease severity25. However, while GFAP levels were detectable in ocular fluids in both our and Bai et al.’s studies, neither group found a correlation with levels of cognition. One potential explanation for this discrepancy is GFAP’s role as a nonspecific marker of astrogliosis, a process that occurs in a variety of nervous system diseases including CNS tumors, infectious meningitis, ischemic stroke, multiple sclerosis, and various forms of dementia26. The retina, as an extension of the central nervous system, contains astrocytes capable of astrogliosis, and elevated GFAP levels have been found in a variety of retinal diseases including retinal detachment, epiretinal membrane27, and diabetic retinopathy28,29,30. All participants in our study had surgical retinal disease and 38 of 55 participants (69%) in Bai et al.’s study had neovascular AMD, a condition that similarly is associated with elevated vitreous GFAP levels31. Thus, the levels of intraocular GFAP detected in each of these studies may be confounded by participants’ associated retinal diseases, potentially preventing any accurate comparison to cognitive testing. Future studies should consider measuring GFAP levels in the ocular fluids of subjects without a history of previous retinal disease or attempt to recruit large, balanced cohorts to quantify and account for ocular disease-specific variability in GFAP expression.

Our study has several other potential weaknesses. There was a wide range of GFAP levels in both of ocular fluids. Such variability may impact the strength of measured correlations, and while one can speculate on factors contributing to this variability, including differences in blood-retinal barrier integrity, localized retinal stress responses, and disease pathology, our sample size limits our ability for further stratification. In addition, we also recognize that our study may have introduced some inconsistency by measuring GFAP levels from ocular fluid and serum specimens drawn on different days. Serum GFAP levels have been shown to rise gradually over years in subjects with AD32 and to vary over as little as 72 h in subjects with acute traumatic brain injury33. Thus, it is possible that the up to 2 month delay between ocular fluid and serum sampling in our study may have impacted our serum protein measurements. Finally, while both vitreous and aqueous can be collected in an in-office procedure, vitreous tap does not always collect an adequate sample34 and is likely associated with more potential complications than aqueous sampling. The correlation of vitreous and aqueous GFAP levels found in our study suggests that future studies can potentially use aqueous sampling alone as a representative ocular biofluid, although even aqueous sampling is an invasive procedure, the risks of which would require justification if there are non-invasive diagnostic alternatives.

Conclusion

GFAP levels can be measured in both the aqueous and vitreous as well as plasma. Although our study found no significant association between intraocular fluid GFAP levels and cognitive function, the presence of retinal disease in our subject cohort complicates interpretation and limits the generalizability of our findings. Future studies of ocular fluid biomarkers for neurodegenerative disease should seek to clarify the relationship of these markers to eye disease in order to establish the potential generalizability of results.

Data availability

The data used and/or analyzed during this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Serrano-Pozo, A. et al. Differential relationships of reactive astrocytes and microglia to fibrillar amyloid deposits in alzheimer disease. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 72, 462–471 (2013).

Yang, Z. & Wang, K. K. Glial fibrillary acidic protein: from intermediate filament assembly and gliosis to neurobiomarker. Trends Neurosci. 38(6), 364–374 (2015).

Sofroniew, M. V. Astrogliosis. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 7(2), a020420 (2014).

Carter, S. F. et al. Evidence for astrocytosis in prodromal Alzheimer disease provided by 11C-deuterium-L-deprenyl: a multitracer PET paradigm combining 11C-Pittsburgh compound B and 18F-FDG. J. Nucl. Med. 53(1), 37–46 (2012).

Elahi, F. M. et al. Plasma biomarkers of astrocytic and neuronal dysfunction in early- and late-onset Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 16, 681–695 (2020).

Oeckl, P. et al. Glial fibrillary acidic protein in serum is increased in alzheimer’s disease and correlates with cognitive impairment. J. Alzheimers Dis. 67, 481–488 (2019).

Chatterjee, P. et al. Plasma glial fibrillary acidic protein is elevated in cognitively normal older adults at risk of Alzheimer’s disease. Transl. Psychiatry 11(1), 27 (2021).

Fereshetian, S. et al. Protein and imaging biomarkers in the eye for early detection of alzheimer’s disease. J. Alzheimers Dis. Rep. 5(1), 375–387 (2021).

Vig, V. et al. Vitreous humor biomarkers reflect pathological changes in the brain for alzheimer’s disease and chronic traumatic encephalopathy. J. Alzheimers Dis. 93(3), 1181–1193 (2023).

Subramanian, M. L. et al. Neurofilament light chain in the vitreous humor of the eye. Alzheimers Res. Ther. 12(1), 111 (2020).

Wright, L. M. et al. Association of cognitive function with amyloid-beta and tau proteins in the vitreous humor. J. Alzheimers Dis. 68(4), 1429–1438 (2019).

Patel, H. et al. Aqueous and plasma levels of phosphorylated tau 181 in individuals with normal cognition. J. Alzheimers Dis. 100, 239–245 (2024).

Bai, J. et al. Association of cognitive function with neurofilament light chain in the aqueous humor of human eye. Front. Aging Neurosci. 14, 1027705 (2022).

Benjamini, Y. & Hochberg, Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: A practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B (Methodol.) 57(1), 289–300 (1995).

McGrory, S. et al. The application of retinal fundus camera imaging in dementia: A systematic review. Alzheimers Dement. (Amst). 2(6), 91–107 (2016).

Cheung, C. Y. et al. A deep learning model for detection of Alzheimer’s disease based on retinal photographs: A retrospective, multicentre case-control study. Lancet Digit. Health 4(11), e806–e815 (2022).

Shi, X. H. et al. Deep learning models for the screening of cognitive impairment using multimodal fundus images. Ophthalmol. Retina S2468–6530(24), 00045–00049 (2024).

Mutlu, U. et al. Association of retinal neurodegeneration on optical coherence tomography with dementia: A population-based study. JAMA Neurol. 75(10), 1256–1263 (2018).

Chan, V. T. T. et al. Spectral-domain OCT measurements in alzheimer’s disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ophthalmology 126(4), 497–510 (2019).

O’Bryhim, B. E., Lin, J. B., Van Stavern, G. P. & Apte, R. S. OCT Angiography findings in preclinical Alzheimer’s disease: 3-year follow-up. Ophthalmology 128(10), 1489–1491 (2021).

Goldstein, L. E. et al. Cytosolic beta-amyloid deposition and supranuclear cataracts in lenses from people with Alzheimer’s disease. Lancet 361(9365), 1258–1265 (2003).

Inada, K. et al. Increase of aqueous humor proteins with aging. Jpn. J. Ophthalmol. 32(2), 126–131 (1988).

Benedet, A. L. et al. Differences between plasma and cerebrospinal fluid glial fibrillary acidic protein levels across the Alzheimer disease continuum. JAMA Neurol. 78, 1471–1483 (2021).

Cicognola, C. et al. Plasma glial fibrillary acidic protein detects Alzheimer pathology and predicts future conversion to Alzheimer dementia in patients with mild cognitive impairment. Alzheimers Res. Ther. 13, 68 (2021).

Oeckl, P. et al. Glial fibrillary acidic protein in serum is increased in Alzheimer’s disease and correlates with cognitive impairment. J. Alzheimers Dis. 67, 481–488 (2019).

Zheng, X., Yang, J., Hou, Y., Shi, X. & Liu, K. Prediction of clinical progression in nervous system diseases: plasma glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP). Eur. J. Med. Res. 29(1), 51 (2024).

Jünemann, A. G. et al. Elevated vitreous body glial fibrillary acidic protein in retinal diseases. Graefes Arch. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 253(12), 2181–2186 (2015).

Rungger-Brändle, E., Dosso, A. A. & Leuenberger, P. M. Glial reactivity, an early feature of diabetic retinopathy. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 41(7), 1971-80 (2000).

Yu, Y., Chen, H. & Su, S. B. Neuroinflammatory responses in diabetic retinopathy. J. Neuroinflamm. 12, 141 (2015).

Hernández, C., Simó-Servat, O., Porta, M., Grauslund, J., Harding, S. P., Frydkjaer-Olsen, U., García-Arumí, J., Ribeiro, L., Scanlon, P., Cunha-Vaz, J. & Simó, R; European Consortium for the Early Treatment of Diabetic Retinopathy (EUROCONDOR). Serum glial fibrillary acidic protein and neurofilament light chain as biomarkers of retinal neurodysfunction in early diabetic retinopathy: results of the EUROCONDOR study. Acta Diabetol. 60(6), 837–844 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00592-023-02076-1

Wu, K. H. C. et al. Differential expression of GFAP in early v late AMD: A quantitative analysisBritish. J. Ophthalmol. 87, 1159–1166 (2003).

Rajan, K. B. et al. Longitudinal changes in blood biomarkers of clinical Alzheimer disease in a biracial population sample. Neurology 100(8), e874–e883 (2023).

Robertson, C. S. et al. Serial measurements of serum glial fibrillary acidic protein in moderate-severe traumatic brain injury: Potential utility in providing insights into secondary insults and long-term outcome. J Neurotrauma. 41(1–2), 73–90 (2024).

Giovinazzo, J. V., Jansen, M., Iacob, C., Rosen, R. B. & Deobhakta, A. Obtaining vitreous samples in acute endophthalmitis: Comparing the rate of dry taps using a needle vs trocar cannula. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 59(9), 3673 (2018).

Funding

This research was funded by NIH/NIA/ERP: 1R03AG063255-01, PI Manju Subramanian; P30AG072978, the United States Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration, BLRD Merit Award (I01BX005933), PI Thor Stein.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Study conception and design: M.L.S., M.L.A., T.D.S., W.X., Y.T., M.G.F. Data acquisition: S.N., X.C., N.H.S., A.S., M.F. Data Analysis: F.T-Z., K.S. Writing of Manuscript: S.N. Editing of Manuscript: All authors reviewed and approved of manuscript prior to submission.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ness, S., Sampani, K., Tuz-Zahra, F. et al. Glial fibrillary acidic protein in plasma and intraocular fluids and the correlation with cognitive function in patients with vitreoretinal disease. Sci Rep 15, 28720 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-13260-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-13260-4