Abstract

Obtaining the temperature and ampacity of high voltage cable joints during operation is crucial for increasing the reliability and flexibility of power systems. Indirect measurement methods based on digital models have gained widespread attention because of their potential for accurate and comprehensive assessment. However, owing to limitations in modelling techniques and measurement capabilities, the digital model of cable joints necessitates the use of parameters that are difficult to obtain, resulting in limited accuracy, high costs, and poor interpretability. Therefore, in this study, a digital model is constructed on the basis of thermal–flow coupling and measurable data, and an ampacity evaluation method is proposed. Based on the installation conditions and heat transfer rules, the external environment model of cable joints has been simplified. The multiscale modelling method is adopted to couple temperature data between a 3-D cable joint with the surrounding air model and a 1-D external environment model. The finite element method (FEM) is used to analyse the thermal performance. Taking a 110 kV, 630 mm2 cable joint as an example, the temperature distribution and flow velocity distribution are simulated. The temperature test results show that the proposed model is consistent with the test results. The influences of the AC current, ambient temperature, and thermal conductivity are simulated to prove that the digital model meets the requirements of complex operation conditions. Considering the external ambient temperature and internal thermal conductivity, an evaluation function is determined through regression analysis to rapidly calculate the ampacity. In summary, the proposed method matches actual measurement capabilities, which has potential for application in the actual field.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

High voltage (HV) power cables are important power equipment widely used in power transmission because of their excellent performance1. With the development of cities and the increase in transmission distances, the use of HV cable joints to connect power cables has become more common. However, the cable joints have always been weak points in the cable system2,3. Owing to current overload, complex environments, heat dissipation, and other factors, cable joints are prone to overheating during operation. This limits the transmission capacity, accelerates insulation deterioration, and increases the fault risk4. Therefore, temperature analysis and ampacity evaluation of HV cable joints are highly important for ensuring the reliability and flexibility of cable systems.

Direct measurement is an accurate and effective method for obtaining the temperature, which requires sensors to be embedded in the cable joint5. However, owing to the high voltage applied to the cable joint, this method has many technical difficulties, such as high cost and maintenance inconvenience. In contrast, indirect measurement has high application value because it is low cost and noninvasive6,7. In recent years, indirect measurement methods have received widespread attention8,9. This method involves constructing a virtual representation of power equipment for more accurate and comprehensive monitoring10. It is considered a technology with engineering value and application prospects.

The indirect measurement method commonly adopts data driven, analytical, and numerical methods to construct calculation models for obtaining the temperature distribution. (1) Data driven methods do not require the consideration of complex factors such as structural design, heat transfer laws, and the operation environment11,12. It can be easier to achieve temperature analysis depending on the training data. However, owing to the difficulty in resolving the contradiction between the limited training data and the enormous complexity13, the validity of the calculation cannot be guaranteed. (2) The analytical method simplifies the heat transfer process into a lumped parameter model14. Owing to the complexity of materials and the diversity of structures15, accurate parameters for models are challenging to obtain. In addition, this method is unable to show an outline representing temperature distribution7. (3) The numerical method can fully reflect the physical field relationship between the ontology structure and the surrounding environment16. It can accurately simulate the temperature distribution by setting the control equation, boundary conditions, and material parameters17. Therefore, numerical methods are widely recommended for the temperature analysis of power equipment in the indirect measurement field.

The existing numerical methods mainly adopt two modelling approaches for the temperature analysis of cables and their joints. (1) The model is based on large scale and enclosed space. This model consists of cables, joints, cabins, soil, solar radiation, etc18. The majority of parameters in the model can be obtained through onsite measurements or sample measurements, such as cable properties19, cable placement20, and cabin size21. However, due to the influences of climate, geology, and human activities, there are significant differences in some parameters15, such as soil and solar radiation, at different locations. Although existing technologies can measure local data for these parameters22, it is difficult to obtain real data distributions in a large scale space. This leads to the need to assume these parameters, which is prone to errors. In addition, owing to the high calculation cost, large scale models are widely used in the temperature analysis of cable groups, but they are rarely used for cable joints. (2) The model is based on the surface heat transfer coefficient. This model only consists of a cable and its joint23. The surface heat transfer coefficients are used to simplify the heat exchange process between the cable joint and the external environment24. Owing to the complex geometric structure and uneven surface temperature distribution of cable joints, it is difficult to estimate them via direct measurement or empirical formulas25. In past research26, the surface heat transfer coefficients were estimated as constants, ignoring the effect of the environment on heat dissipation. In summary, due to their limited modelling capability, digital models rely on parameters that are difficult to obtain. The acquisition of these parameters on site has problems such as insufficient accuracy and high measurement costs. This limits the application of the indirect measurement method to temperature analysis, which leads to poor reliability of the ampacity evaluation results.

To solve these problems, this paper proposes a new calculation model of HV cable joints on the basis of thermal–flow coupling. According to the installation conditions and heat transfer rules, the model consists of a 3-D cable joint with the surrounding air model and a 1-D external environment model. It relies mainly on measurable data, such as geometric structure, load current, and ambient temperature. Then, taking a 110 kV, 630 mm2 cable joint as an example, the proposed model is employed to simulate the temperature distribution and flow velocity distribution. It can achieve the digital reconstruction of the cable joint. A temperature experiment platform is built to verify the accuracy of the model. Finally, the temperature results under different operation conditions are simulated. This indicates that the model can meet complex operation requirements. Considering the influences of the external ambient temperature and internal thermal conductivity, an ampacity evaluation function is proposed through regression analysis.

Thermal flow coupling model

Physical model

In China, owing to factors such as transmission distance, environment constraints, and operation maintenance, cables are often laid in pipes. HV cable joints are typically installed in an underground special power cabin, as shown in Fig. 1. This cabin is generally used for pipe laying projects to achieve turning and connecting, which does not have auxiliary facilities such as ventilation and lighting systems. The cable joints installed in the special power cabin are not affected by forced convection and can be considered to be in a natural convection state26.

The locations of cables and their joints installed in special power cabins are crucial for temperature analysis. According to our previous research27 and relevant literature28, when cables and their joints are located at a certain distance from the cabin wall, their temperatures are less affected by the cabin wall. In addition, as the distance between cables increases, the mutual thermal effect on the temperature gradually decreases29. According to the data provided by the designer and manufacturer, the appropriate space needs to be reserved to ensure sufficient installation space and heat dissipation capacity. This ensures that the surface distance between the cable joint and other facilities is enough that the temperature is no longer sensitive to them.

The cable and its joint are axisymmetric structures, and the actual temperature distribution has 3-D characteristics. To simplify the analysis, this paper adopts the first-order thermal circuit mode to explain the temperature distribution law of cable joints. The simplified radial thermal circuit model of the cable joint is shown in Fig. 2, where \({Q_{con}}\) is the heat source of the conductor. \({T_{ma}}\) represents the thermal resistance of the material between the conductor and surface. \({T_{conv}}\) is the thermal resistance of natural convection, and \({T_{rad}}\) is the thermal resistance of radiation. \({\theta _{am}}\) represents the ambient temperature. According to IEC 60,287 and the research results of relevant improved methods29, the external environment boundary in the thermal circuit model can be combined into a 1-D voltage source via the lumped parameter method. This is due to the limited influence of the external environment on cable joints on site. This is also due to the large heat capacity of the air30, and the fact that the difference in ambient temperature at different locations in the special cable cabin is limited.

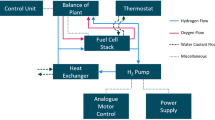

In this work, the cable joint is the main research object, and its heat transfer process needs to be analysed in detail. Based on the actual installation conditions, this paper divides the physical model into two parts: (1) One is a 3-D thermal‒flow coupling model of the cable joint and its surrounding air. (2) Another is a 1-D temperature model of the external environment. The multiscale modelling method is adopted to couple temperature data between the 3-D model and the 1-D model31. The temperature data can be directly measured through sensors32. The heat dissipation process of a cable joint is similar to heat conduction, heat radiation, and heat convection of independent units in free air24. The multiphysical and multiscale coupling relationship is shown in Fig. 3. This is a new temperature analysis model for HV cable joints. Compared with models based on large scale and enclosed spaces15, this approach avoids the dependence on external environmental parameters such as soil and solar radiation. Compared with computational models based on the surface heat transfer coefficient26, this approach considers the thermal–flow coupling relationship and does not rely on the surface heat transfer coefficient.

Mathematical model

To reduce the calculation complexity while ensuring the scientific validity and effectiveness of the calculation model, the basic assumptions should be as follows: (1) Structures without notable effects on the calculation results, such as grounding columns and heat shrinkable pipes, can be ignored. (2) Conductor resistivity is considered a function of temperature. The same is true for the density, dynamic viscosity, and thermal conductivity of the fluid. The other material parameters are constant. (3) The conductor and connection tube are combined into one element. Its resistance is regarded as uniform resistance. (4) The steady state conditions are investigated.

When the AC current flows through the conductor of the cable joint, conductor loss, sheath loss and dielectric loss occur. In general, the sheath loss and dielectric loss account for only a small percentage of the total losses in the cross-connecting cable system under normal operation conditions33. Therefore, this paper only considers conductor loss as the main heat source for cable joints. According to Joule’s laws34, the calculation formula can be expressed as

where \({Q_s}\) is the unit volume heat loss, W/m3; \({R_{ac}}\) is the AC resistance of the conductor, Ω/m; \({S_{{\text{ac}}}}\) is the cross-sectional area of the conductor, m2; and \(I_{{ac}}\) is the RMS value of the AC current, A.

The conductor resistivity of a cable joint is a function of temperature and AC frequency16. The conductor resistivity can be expressed as

where \({\rho _{{\text{ref}}}}\) is the conductor resistivity at the reference temperature, Ω·m; \({a_{{\text{ref}}}}\) is the temperature coefficient at the reference temperature, K− 1; \(\theta\) is the temperature, K; and \({y_s}\) and \({y_{\text{p}}}\) are the skin effect and proximity effect, respectively.

In recent years, the manufacturing process of connection tubes has improved, as shown in Fig. 4a. An appropriate cable joint increases the parallel path for current transmission, and the equivalent circuit is shown in Fig. 4b. Rc is the conductor resistance. Rct is the connection tube resistance. When the contact resistance has a small impact, it can be considered a calculation error15. When the contact resistance has a significant influence23,25, an appropriate cable joint should be used for replacement to avoid faulty operation. Compared with the old manufacturing process24, overheating problems caused by the manufacturing process of connection tubes have become rare. Therefore, this paper ignores the influence of contact resistance.

Heat is transferred from the conductor to the surface through the insulation layer, the shielding layer, etc. Thermal convection is one of the surface dissipating heat approaches for cable joints. The changes in the ambient temperature around the cable joint affect its density, dynamic viscosity, and thermal conductivity. The buoyancy induced by density changes can lead to airflow. The change in viscosity affects the relative velocity of airflow. Moreover, the thermal conductivity affects the heat dissipation effect. According to the energy conservation law, the thermal field control equation can be expressed as

where \({\rho _{\text{f}}}\) is the density of the fluid, kg/m3; \({C_{\text{f}}}\) is the thermal capacity of the fluid, J/(kg K); \({\lambda _{\text{s}}}\) and \({\lambda _{\text{f}}}\) are the thermal conductivities of the solid and fluid, W/(m·K); and \({{\mathbf{u}}_{\text{f}}}\) is the fluid velocity, m/s.

Since the fluid density is affected mainly by temperature and its compressibility can be ignored, the fluid model is simplified by using the Boussinesq approximation to enhance convergence. The fluid density \({\rho _{\text{f}}}\) at a reference pressure of 1 atm can be expressed as

where \({\rho _{{\text{ref}}}}\) is the fluid density at 293.15 K, kg/m3, and \(\beta\) is the thermal expansion coefficient, K− 1.

The Reynolds–Averaged-Navier–Stokes equation and the standard k–ε turbulence model are used to describe fluid flow21. In addition to the law of energy conservation, the model also obeys the mass conservation and momentum conservation equations, as shown in Eqs. (6) and (7).

where P is the pressure, Pa; \({\mathbf{I}}\) is the density vector;\({\mathbf{g}}\) is the gravity vector, N/kg; \({\mu _{\text{f}}}\) is the fluid dynamic viscosity, Pa s; \({\mu _{\text{T}}}\) is the turbulence dynamic viscosity, Pa s; and k is the turbulence kinetic energy, J.

The control equations of the turbulence kinetic energy k and specific dissipation rate ε are shown as

where \({G_{\text{k}}}\) is the turbulence energy contributed by the average viscous gradient and where \({c_{{1}{\varepsilon}}}\), \({c_{{2}{\varepsilon}}}\), \({\sigma _{\text{k}}}\) and \(\sigma _{\varepsilon}\) are experimental constants, with values of 1.44, 1.92, 1.0, and 1.3, respectively.

Boundary conditions

Boundary conditions are an important part of the multi-physical field coupling model and provide the basis for obtaining a definite solution. The solution domain structure diagram and boundary conditions are shown in Fig. 5. The connection tube is set as the centre. The boundary conditions are constrained by a 1-D ambient temperature.

Cable joint surface (SΩ). The surface transfers heat through radiation and convection, as described by Eq. (10)16. The heat radiation on the cable surface can be described via the Stefan–Boltzmann law33. The heat convection is calculated via the energy conservation equation. It is not necessary to set the convective heat transfer coefficient separately. The fluid velocity at the cable joint surface is zero. The boundary is set as a no-slip boundary condition, which satisfies Eq. (11).

where \({\varepsilon _{\text{k}}}\) is the surface emissivity, 0.914; \(\delta\) is the Stefan–Boltzmann constant, 5.67 × 10− 8 W/(m2·K4); h is the natural convection coefficient, W/(m·K); and \(\theta _{{{\text{surf}}}}^{{}}\) is the surface temperature, K.

Lateral and upper portion boundaries (S1-S3). The air flows mainly from the lateral boundary and out of the upper boundary. Since the boundary line of the inlet and outlet is not clear, the boundary is treated as an open boundary, where the inflow and outflow directions are determined by the velocity direction. When the fluid flows into the solution domain, the heat flux control equation is shown as Eq. (12), according to the Danckwerts’ boundary condition. For the flow field, the pressure boundary based on the Bernoulli equation is used for analysis, as shown in Eq. (13), considering the effects of gravitational potential energy. When the fluid flows out, the temperature gradient in the normal direction is zero, which satisfies Eq. (14). The flow field boundary is still analysed via Eq. (13).

where \({\mathbf{w}}\) is the relative position and where \({f_{\text{0}}}\) is the normal stress term, Pa.

Lower portion boundary (S4). The air flows from the bottom part to the cable joint during the process of natural convection, so the boundary is regarded as the inlet boundary. The control equation of the boundary conditions is set as Eq. (12) and Eq. (13).

Front and rear portion boundary (S5, S6). The boundary is set as the insulation boundary. The heat flux at the boundary is 0, which satisfies Eq. (14). The fluid flux at the boundary is also 0, which satisfies Eq. (11).

Calculation process

In this paper, the thermal‒flow coupling model uses the FEM for numerical calculations. The calculation process is shown in Fig. 6. To ensure solution accuracy and improve calculation efficiency, a multilevel grid approach is used to divide the solution domain. As the internal temperature distribution of the cable joint is the focus, the cable joint and its boundary layer adopt fine grids. The other regions adopt coarse grids.

Example analysis

Calculation parameters

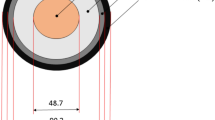

This study considers 110 kV, 630 mm2 XLPE cables and their joints as examples for analysis. The structural diagram is shown in Fig. 7. The structural and thermal parameters are obtained through sample testing from the manufacturer25. The parameters are shown in Tables 1 and 2. Considering the influence of temperature on fluid parameters35, the parameters can be calculated via the fitting function shown in Table 3. The AC current and ambient temperature can be measured in the field via site sensors.

Calculation analysis

This paper takes an AC current of 1000 A and an ambient temperature of 293.15 K as examples for analysis. The physical size of the model with open boundary conditions has a significant effect on the temperature analysis. The influence of model size on the calculation accuracy and calculation cost is analysed via the control variable method19, as shown in Fig. 8. Both the accuracy and the time of the calculation increase with increasing model size. When the width and height of the calculation model (D) are 500 mm and the length of the calculation model (L) is 8000 mm, the calculation error is within 0.1 K, and the calculation time is acceptable. Compared with the large scale and enclosed space model in Fig. 121, the size of the proposed model is smaller, and it takes less calculation time.

The temperature and flow velocity distributions of the cable joint and its surrounding air are shown in Fig. 9. The temperature distribution curve has a concave shape. As the contact resistance is qualified23, the temperature of the connection tube is the lowest. With increasing axial distance from the connection tube, the conductor temperature continues to rise. When the distance is greater than 2.5 m, the temperature tends to be stable. In the area of the cable joint, heat is transmitted by heat conduction, and the temperature decreases linearly with the thermal conductivity of the material. In the surrounding air environment, heat is transmitted by natural convection. The temperature decays rapidly in the radial direction and finally tends towards the air temperature. The cable joint also radiates heat, but the impact on the fluid temperature is limited. This is because the vast majority of the radiation wave energy passes through the gaps between air molecules. According to the simulation results, the maximum flow velocity is above the cable joint section, where the value is less than 0.15 m/s. In other directions, the velocity first increases and then decreases along the radial direction because of the boundary layer effect. The temperature and velocity boundary layer thickness at the surface in the solution domain is less than 0.1 m. Overall, the proposed model can calculate the temperature and flow velocity distributions. Compared with existing temperature analysis methods15,23, this model effectively reduces the dependence of data that are difficult to obtain, such as soil thermal parameters and the surface heat transfer coefficient. Moreover, since the model parameters are all real, the interpretability of the calculation results is guaranteed.

Model verification

Experimental environment

Steady state temperature tests are carried out to verify the feasibility and effectiveness of the proposed model. In these tests, the AC current and ambient temperature are considered for the temperature rise effect of the cable joint. This experiment is designed based on the IEC 60,84036. The experimental site is shown in Fig. 10. The experimental system consists of the test object, the environmental simulation box, the current control system and the temperature measurement system, as shown in Fig. 11.

An air environment simulation box is designed to simulate the environmental conditions of special cable cabins across a range of temperatures. Considering the influence of the axial heat transfer distance and ambient temperature difference, this box has dimensions of 10 m × 2 m × 1.8 m based on the longitudinal section size of the special cable cabin. The box is constructed from heat insulation tarpaulin to stabilize the ambient temperature. Two adjustable heaters (BGP1403-03T) are set in the box to simulate and maintain different ambient temperatures. The environmental simulation box is located in an experimental hall to minimize the impact of external factors such as solar radiation and forced convection.

The current control system generates an induced current for the test object. The control platform adjusts the induced current by controlling the current raising system (SLB-50/0.01/0.4). The current transformer (HL-5000) is used for real time current acquisition to monitor the experimental current. During the experiment, a clamp metre (fluke 381) and a flexible current probe (iflex i2500-18) were used for the reference test of the experimental current.

The temperature measurement system is composed of thermocouples and a temperature acquisition module, which has the ability to prevent electromagnetic interference. T-type thermocouples that are 200 mm long and 2 mm in diameter are inserted to measure the conductor temperature distribution of the cable joint accurately. The thermocouples are also placed around the cable joint to measure the ambient temperature. The accuracy of the temperature measurement system was verified via a thermometer (fluke 62 max+), with a measurement error within ± 0.5 K.

Experimental scheme and verification

The experiment was conducted in several steps to simulate operation conditions with AC currents of 500 A, 750 A and 1000 A and ambient temperatures of 293.15 K and 303.15 K. First, the recent temperature of the experimental site needed to be investigated. A time period with minimal diurnal temperature variation was chosen to make it easier to maintain a constant temperature in the environment simulation box. Before the experiment, the heater was started to ensure that the ambient temperature was consistent with the simulated ambient temperature. The status can be considered steady state when the change in measuring temperature is less than 1 K per hour31. Then, the induced current was set to start the temperature rise experiment. The temperature data were measured automatically at intervals of 6 min. When the conductor and ambient temperature reached dynamic stability, the experiment was stopped, and the data were recorded.

The temperature distributions of the simulation and the experiment are shown in Figs. 12 and 13. The maximum error is less than 4.0 K and remains unchanged under different operation conditions. This finding shows that the proposed model can accurately calculate the temperature distribution of the cable joint with AC current and ambient temperature. Compared with existing temperature analysis methods21,26, this model requires fewer sensors and helps reduce the difficulty of indirect measurement technology application.

The main sources of error include the following: (1) The physical structure and material properties in the calculation model are simplified, resulting in errors in the simulation results. (2) The temperature measurement accuracy of thermocouples is easily affected by operation conditions and installation level, resulting in errors in the measurement results. (3) The heater in the environmental simulation box leads to an uneven distribution of temperature and velocity, which has a certain impact on the heat dissipation of cable joints.

Verification with previous studies

The calculation cost of the model based on large scale and enclosed spaces is high, and the soil thermal coefficient and solar radiation in the model are not easy to obtain. In the past, the heat transfer coefficient model was usually used for temperature analysis23,26. The conductor temperature distributions of the thermal–flow coupling model and the heat transfer coefficient model are compared when the current is 1000 A and the ambient temperature is 293.15 K (Fig. 14). Under natural convection conditions, the convective heat transfer coefficient of the cable joint surface is usually within 10 W/(m2·K). The results show that the calculation results of the heat flow model are reasonable. Moreover, for a cable joint with an irregular structure, it is difficult to determine the value of the surface heat transfer coefficient in the existing research, so it is impossible to accurately determine the temperature distribution of the cable joint. The proposed method successfully avoids the dependence on the heat transfer coefficient.

Influence analysis and ampacity calculation

To validate the ability of the proposed model to meet the temperature reconstruction requirements under various operation conditions, this paper investigated the impact of typical factors such as the AC current, ambient temperature, and thermal conductivity on the operating temperature. Furthermore, considering the influence of the external ambient temperature and internal thermal conductivity, a rapid calculation function for real time current loading has been proposed.

Influence of current

The simulation results of the conductor temperature affected by the AC current are shown in Fig. 15. The ambient temperature of 293.15 K is taken as an example. When the AC current increases from 500 A to 700 A, the temperature of the connection tube increases by 7.0 K. When the AC current increases from 700 A to 900 A, the temperature of the connection tube increases by 9.6 K. This finding demonstrates that the conductor temperature increases as the AC current increases. The rate at which the temperature increases is greater at higher AC currents. This is because the main heat source comes from conductor loss, as described by Eq. (1). When the AC current increases from 500 A to 1000 A, the temperature of the connection tube increases by 22.5 K, and the temperature of the cable conductor increases by 28.6 K. The temperature rise at the connection tube is smaller than that at other positions. The results indicate that the temperature variation trend of the conductor in the cable joint with increasing AC current is in line with the actual situation.

Influence of ambient temperature

The simulation results of the conductor temperature affected by the ambient temperature are shown in Fig. 16. The cable joint temperature under an AC current of 900 A is taken as an example. When the ambient temperature increases from 278.15 K to 308.15 K, the temperature of the connection tube increases from 301.8 K to 332.1 K, and the temperature of the cable conductor increases from 308.7 K to 338.3 K. For every 1 K increase in ambient temperature, the conductor temperature increases by approximately 1 K. The conductor temperature increases linearly with changes in ambient temperature. The results indicate that the influence of the ambient temperature has been effectively simulated.

Influence of thermal conductivity

The influence of the external air environment on heat dissipation capacity can be determined according to the thermal‒flow coupling calculation model of HV cable joints. In this way, the thermal conductivity of the internal material between the conductor and the surface becomes the main factor affecting the heat dissipation capacity. However, there are certain differences between internal materials from different manufacturers. The actual thermal conductivity capacity of internal materials may differ from that of the calculation model.

According to Fig. 2, when analysing the conductor temperature of cable joints, the internal material can be treated as a whole unit based on the lumped parameter method. To study the effects of changes in the thermal conductivity, the deviation ratio \({k_{\uplambda}}\) was set as the ratio of the actual thermal conductivity to the model thermal conductivity. Taking the conductor temperature distribution under an AC current of 1000 A and an ambient temperature of 293.15 K as an example, simulation results with different deviation ratios of thermal conductivity were obtained in Fig. 17. When \({k_{\uplambda}}\) was 110%, the average temperature was 326.7 K. When \({k_{\uplambda}}\) was 100%, the average temperature was 328.5 K. When \({k_{\uplambda}}\) was 90%, the average temperature was 330.8 K. The conductor temperature decreased with increasing internal material thermal conductivity. When the thermal conductivity increased, the heat dissipation capacity increased. Improving the thermal conductivity of internal materials can effectively improve the heat dissipation capacity of cable joints. Considering that the deviation ratio is limited in practice, its impact on temperature can be approximated as linear. The results indicated that the proposed model fully simulates the temperature variation trend under different internal material thermal conductivities.

Ampacity calculation

According to the thermal‒flow coupling field model based on the open boundary, the temperature distribution of a cable joint is determined by the AC current, ambient temperature, and thermal conductivity. The load current and ambient temperature can be obtained via direct measurement. The thermal conductivity can be obtained via sample measurement. Compared with the thermal‒flow coupling field model, which is based on a closed space37, this model is easier to realize in practical applications without difficulty in measuring parameters such as soil thermal parameters and surface environmental parameters. In addition, compared with the temperature calculation model with a surface heat transfer coefficient26, this model does not consider the surface heat transfer coefficient as a constant, which can better handle the influence of the operating environment.

The ampacity is important for the operation of power transmission. When the ampacity estimation result is less than the actual value, it will reduce the transmission ability and cause resource waste and economic loss. When the ampacity estimation result is greater than the actual value, it leads to a higher operation temperature and affects operation safety. In this work, the temperature limit condition of the cable joint is set as the maximum allowable temperature of the insulation material14. The external ambient temperature is obtained through real time measurement by sensors. The deviation of the internal thermal conductivity can be estimated and set as the management margin. According to the temperature distribution of the cable joint, this paper takes the maximum conductor temperature as the evaluation standard to calculate the ampacity via the iterative method shown in Fig. 18.

The ampacity of cable joints at an ambient temperature \({\theta _{{\text{am}}}}\)of 278.15–313.15 K and a thermal conductivity deviation ratio \({k_{\uplambda}}\) of 90%-110% is analysed. The ampacity calculation results are shown in Fig. 19. As the ambient temperature increased by 5 K, the average value of the ampacity decreased by 42.9 A. As the deviation ratio of the thermal conductivity decreased by 5%, the average value of the ampacity decreased by 17.6 A. The fitting function of the ampacity \({I_{\text{a}}}\) is expressed in Eq. (15) according to the relationship between the operation conditions and the temperature distribution. The correlation coefficient was near 0.99. The error was within 15 A. Compared with existing methods22,26, the proposed method requires less measurement data and is easier to implement in practical applications.

Conclusion

This paper establishes a new research idea of a temperature calculation model for HV cable joints on the basis of thermal–flow coupling and measurable data. Additionally, an evaluation function for ampacity has been proposed. Through example analysis and experimental verification, the following conclusions are obtained:

-

1.

Based on the installation environment in the special cable cabin, a numerical model of the cable joint and its surrounding air has been developed, utilizing methods such as thermal–flow coupling and multiscale modelling. The calculation model can fully simulate the heat transfer process by considering the effects of heat conduction, heat radiation, and heat convection. Compared with existing methods, it avoids the dependence on data that are difficult to obtain, such as the heat transfer coefficient, soil thermal coefficient, and solar radiation. This research reduces the difficulties associated with numerical modelling and parameter measurement.

-

2.

The proposed model can achieve digital reconstruction of the operation temperature for HV cable joints, using measurement data of the AC current and ambient temperature. It matches actual measurement capabilities on site and has a limited calculation cost, reducing the application difficulty of indirect measurement technology. The experimental results show that the temperature deviation between the simulation and experimental results is less than 4.0 K, which verifies the accuracy of the proposed model.

-

3.

The simulation results of the digital model are consistent with the actual law under different operation conditions. The conductor temperature of the cable joint increases with increasing AC current and ambient temperature. The conductor temperature of the cable joint increases with decreasing thermal conductivity. The proposed model meets the complex and varied operation requirements.

-

4.

The evaluation function can provide the ampacity of the HV cable joint in a timely manner, with an error within 15 A. This approach can provide technical support for the online management of the temperature of cable joints in the actual field.

Data availability

Data is provided within the manuscript.

References

Li, Y., Zhu, G. Y., Zhou, K., Meng, P. F. & Wang, G. D. Evaluation of graphene/crosslinked polyethylene for potential high voltage direct current cable insulation applications. Sci. Rep. 11, 1. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-97328-x (2021).

Pompili, M. et al. Joints defectiveness of MV underground cable and the effects on the distribution system. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 192, 1. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.epsr.2020.107004 (2021).

Raymond, W. J. K., Illias, H. A. & Abu Bakar, A. Classification of partial discharge measured under different levels of noise contamination. Plos One, 12, 1. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0170111 (2017).

Soleimani, M., Faiz, J., Nasab, P. S. & Moallem, M. Temperature Measuring-Based Decision-Making prognostic approach in electric power Transformers winding failures. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 69, pp. (9). https://doi.org/10.1109/TIM.2020.2975386 (2020).

Zhao, L., Li, Y., Xu, Z., Yang, Z. & Lu, A. On-line monitoring system of 110 kV submarine cable based on BOTDR. Sens. Actuators. 216, 1. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sna.2014.04.045 (2014).

Singh, R. S., Cobben, S. & Cuk, V. PMU-Based cable temperature monitoring and thermal assessment for dynamic line rating. IEEE Trans. Power Deliv. 36(3), 1. https://doi.org/10.1109/TPWRD.2020.3016717 (2021).

Tang, L., Ruan, J., Qiu, Z., Liu, C. & Tang, K. Strongly robust approach for temperature monitoring of power cable joint. IET Gener Transm Distrib. 13 (8), 1324–1331. https://doi.org/10.1049/iet-gtd.2018.5924 (2019).

Kabugo, J. C., Jämsä-Jounela, S. L., Schiemann, R. & Binder, C. Industry 4.0 based process data analytics platform: A waste-to-energy plant case study. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 115, pp. (1). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijepes.2019.105508 (2020).

Rasheed, A., San, O. & Kvamsdal, T. Digital twin: values, challenges and enablers from a modeling perspective. IEEE Access. 8, 1. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2020.2970143 (2020).

Zhu, X., Wang, Y., Meng, R., Long, S. & Wu, S. Fast electrothermal coupling calculation method for supporting digital twin construction of electrical equipment. High. Voltage. 8 (2), 1. https://doi.org/10.1049/hve2.12260 (2023).

Ruan, J., Zhan, Q., Tang, L. & Tang, K. Real-Time temperature Estimation of Three-Core Medium-Voltage cable joint based on support vector regression. Energies 11, 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/en11061405 (2018).

Zhan, Q., Ruan, J., Zhu, H. & Wang, Y. A robustness temperature inversion method for cable straight joints based on improved sparrow search algorithm optimized BPNN. IEEE Access. 10, 1. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2022.3207564 (2022).

Zhao, H., Zhang, Z. L., Yang, Y., Xiao, J. Y. & Chen, J. X. A dynamic monitoring method of temperature distribution for cable joints based on thermal knowledge and conditional generative adversarial network. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 1, 1. https://doi.org/10.1109/TIM.2023.3317485 (2023).

IEC 60287-2-1. Electric cables, Calculation of the Current Rating – Part 2–2: Current Rating Equations (100% Load Factor) and Calculation of Losses – Thermal Resistance, 2nd ed., (2006).

Bragatto, T. et al. A 3-D nonlinear thermal circuit model of underground MV power cables and their joints. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 173, 1. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.epsr.2019.04.024 (2019).

Jamali-Abnavi, A., Hashemi-Dezaki, H., Ahmadi, A., Mahdavimanesh, E. & Tavakoli, M. J. Harmonic-based thermal analysis of electric Arc furnace’s power cables considering even current harmonics, forced convection, operational scheduling, and environmental conditions. Int. J. Therm. Sci. 170, 1. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijthermalsci.2021.107135 (2021).

Hamdan, M. A., Pilgrim, J. A. & Lewin, P. L. Analysis of thermo-mechanical stress in three core submarine power cables. IEEE Trans. Dielectr. Electr. Insul. 27 (4), 1. https://doi.org/10.1109/TDEI.2020.008750 (2020).

Gouda, O. E., Osman, G. F. A., Salem, W. A. A. & Arafa, S. H. Load cycling of underground distribution cables including thermal soil resistivity variation with soil temperature and moisture content. IET Gener Transm Distrib. 12 (18), 1. https://doi.org/10.1049/iet-gtd.2018.5589 (2018).

Xu, Z. et al. Application of temperature field modeling in monitoring of optic-electric composite submarine cable with insulation degradation. Meas. J. Int. Meas. Confed. 133, 1. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.measurement.2018.10.028 (2019).

Xu, X. et al. Simulation analysis of carrying capacity of tunnel cable in different laying ways. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 130, 1. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijheatmasstransfer.2018.10.059 (2019).

Wang, J., Liu, X., Chen, S., Jiang, H., Fang, G., Chen, W., & Deng, S. Reduced-scale model study on cable heat dissipation and airflow distribution of power cabins. Appl. Therm. Eng. 160, 1. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2019.114068 (2019).

Chatzipanagiotou, P., Chatziathanasiou, V., De Mey, G., & Więcek, B. Influence of soil humidity on the thermal impedance, time constant and structure function of underground cables: A laboratory experiment. Appl. Therm. Eng. 113, 1. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2016.11.117 (2017).

Yang, F. et al. 3-D thermal analysis and contact resistance evaluation of power cable joint. Appl. Therm. Eng. 93, 1. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2015.10.076 (2016).

Jamali-Abnavi, A. & Hashemi-Dezaki, H. Harmonic-based 3D thermal analysis of thyristor-controlled reactor’s power cable joints considering external electromagnetic fields. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 205, 107727. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.epsr.2021.107727 (2022).

Zhao, H., Zhang, Z., Yang, Y., Gan, P. & Liu, X. Real-time reconstruction of temperature field for cable joints based on inverse analysis. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 144, 1. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijepes.2022.108573 (2022).

Wang, P., Liu, G., Ma, H., Liu, Y. & Xu, T. Investigation of the ampacity of a prefabricated straight-through joint of high voltage cable. Energies 10, 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/en10122050 (2017).

Zhao, H., Zhang, Z., Wu, Y., Yang, Y. & Dong, Z. Thermal analysis of power cable in tunnel considering difffferent laying conditions. In 6th Int. Conf. Power Energy Eng. (ICPEE). 2022. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICPEE56418.2022.10050315 (2022).

Terracciano, M., Purushothaman, S., De León, F. & Farahani, A. V. Thermal analysis of cables in unfilled troughs: investigation of the IEC standard and a methodical approach for cable rating. IEEE Trans. Power Deliv. 27, 3. https://doi.org/10.1109/TPWRD.2012.2192138 (2012).

Sedaghat, A. & De Leon, F. Thermal analysis of power cables in free air: evaluation and improvement of the IEC standard ampacity calculations. IEEE Trans. Power Deliv. 29, 5. https://doi.org/10.1109/TPWRD.2013.2296912 (2014).

Chang, H., Tan, T. T., Ruan, J. J., Gao, Y. P. & Liu, K. Research on temperature retrieval and fault diagnosis of the cable joint. In 39th Annual Conference of the IEEE Industrial Electronics Society(IECON), Vienna, Austria. https://doi.org/10.1109/IECON.2013.6700362 (2013).

Chi, C., Yang, F., Xu, C., Cheng, L. & Yang, C. A multi-scale thermal-fluid coupling model for ONAN transformer considering entire Circulating oil systems. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. Vol. 135, 1. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijepes.2021.107614 (2022).

Bao, H., Deng, Z., Zhang, R., Hu & Liu, G. Heat transfer enhancement method for high-voltage cable joints in tunnels. Int. J. Therm. Sci. 183, 1. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijthermalsci.2022.107872 (2023).

Liu, G. et al. An improved analytical thermal rating method for cables installed in short-conduits. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 123, 1. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijepes.2020.106223 (2020).

Doukas, D. I., Papadopoulos, T. A., Chrysochos, A. I., Labridis, D. P. & Papagiannis, G. K. Multiphysics modeling for transient analysis of Gas-Insulated lines. IEEE Trans. Power Delivery. 33 (6), 2786–2793. https://doi.org/10.1109/TPWRD.2018.2820022 (2018).

Bergman, T. L. et al. Fundamentals of Heat and Mass Transfer, 8th Edition, pp.911.

IEC 60840. Power cables with extruded insulation and their accessories for rated voltages above 30 kV (Um = 36 kV) up to 150 kV (Um = 170 kV) – Test methods and requirements, 4th ed., (2011).

Fan, Y., Peng, C. & Jun, C. Investigation of heat dissipation of power cable laied in the tunnel with ventilation [C]. In 2012 Asia-Pacific Power and Energy Engineering Conference (APPEEC). (2012).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Zhang and Zhao wrote the main manuscript text. Zhao,Yang and Liu prepared the main figures. Xiao assisted in experiments. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, Z., Zhao, H., Yang, Y. et al. Temperature analysis and ampacity evaluation of HV cable joints based on thermal flow coupling and measurable data. Sci Rep 15, 27942 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-13265-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-13265-z