Abstract

This work discusses the fabrication of microelectrode arrays (MEAs) using a type of machining process called Reverse-Micro-Electrical-Discharge Machining (Reverse-µEDM). The main aim here is to forecast and fine-tune the surface roughness because MEAs hold a crucial role in the health field for gathering neural signal fields i.e., highly accurate and in the optimal range. MEAs were made with Reverse-µEDM, known for its better accuracy and precision. Using Taguchi’s L18 test plan, the effect of main factors (voltage, capacitance, and feed rate) was checked carefully. ANOVA showed where variation came from: most of it was from capacitance (86%), then voltage (11%), and feed rate gave a tiny 0.2% contribution to surface roughness. Surface roughness was measured with non-contact profilometer; it took parameters for roughness on surfaces. A Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) was used analyze the topography and microstructure of MEAs. Surface roughness has been predicted using machine learning models such as Artificial Neural Network (ANN), Support Vector Regression (SVR), Random Forest Regression, and Gradient Boosted Trees along with Gaussian Process Regression (GPR). Among them, Random Forest gave the highest accuracy for prediction of surface roughness with maximum value of R² and low error measured by Mean Absolute Error (MAE = 0.18 μm). The Neural Network was almost equally good but took a longer time to train. SVR and GPR provided medium accuracy; Gradient Boosting performed poorly in this small dataset. Leave-One-Out Cross-Validation (LOOCV) yielded strong performance estimates given the small amount of data.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Surface roughness of microelectrodes can have several important implications for their performance and functionality. In terms of electrical performance, the surface roughness of microelectrodes plays a significant role, as it can affect their electrical conductivity1,2. Specifically, a smoother surface typically results in improved electrical conductivity by reducing the resistance and impedance of the electrode. This characteristic is particularly crucial in applications where low impedance and high electrical conductivity are essential, such as in neural probes or microelectrodes for electrophysiological recordings. Surface roughness also influences the electrochemical reactions taking place at the electrode-electrolyte interface. In certain scenarios, a carefully controlled level of roughness can enhance electrochemical performance3,4. This enhancement occurs by increasing the effective surface area, promoting better electrode-electrolyte interaction and heightened sensitivity in various sensing applications. When microelectrodes are utilised in biomedical applications like neural implants or biosensors, their surface roughness can significantly impact biocompatibility. Smoother surfaces are generally considered more biocompatible because they reduce the risk of tissue irritation and inflammation5.

The rough surfaces of microelectrodes encourage biofouling and tissue adhesion, potentially compromising the long-term functionality of the device and also affect microelectrodes’ mechanical stability and durability6,7. It will more susceptible to wear and corrosion, potentially leading to a shorter lifespan for the electrode. However, the optimum roughness can enhance mechanical stability by improving the adhesion between the electrode material and substrate. In sensors and detectors, the surface roughness of microelectrodes can influence sensitivity and selectivity8. Depending on the application, surface roughness is optimize the detection of specific analytes or improve the signal-to-noise ratio, making it a critical consideration. The surface roughness of microelectrodes can affect the adhesion of coatings they may require for various purposes, such as enhancing chemical selectivity or preventing corrosion9. Depending on the nature of the coating, a rough surface may offer better adhesion, while a smoother surface may be more suitable for others10. For producing high-quality microstructures using Reverse-µEDM, it is crucial to consider parameters such as surface roughness, material removal rate, and surface defects (e.g., recast layers, micro-cracks, and debris)11.

It has been evidenced that the fabrication processes influence microelectrode precision and surface quality in Reverse-µEDM. While process parameters can be adjusted to control the shape and size of microelectrodes to some extent, achieving a desired surface smoothness poses a greater challenge through the manipulation of machining parameters. Reverse-µEDM presents an appealing approach for fabricating MEAs on challenging-to-machine materials12. This method capitalises on the absence of physical contact between the tool and workpiece, resulting in approximately zero tool wear, minimal stress imparted to the workpiece, and preserving its structural integrity13. Thus, tools of micron size may be used for the machining of microfeatures on metallic surfaces. Material dissolution takes place at an atomic level, so an excellent surface finish is achievable in any case, irrespective of material hardness. The need for microelectrodes of different shapes and sizes and surface qualities comes in in varied applications14.

Multiple studies have highlighted the significance of surface integrity in fabricating MEAs, particularly for long-term implantable devices15. Our nervous system is made of delicate, soft tissue-imagine it like a fragile network of living wires. Using stiff, rigid microelectrodes here is like trying to fit a square peg into a round hole16. The mismatch in flexibility and density can cause friction, scarring, or even permanent damage to neurons over time17.

Reverse-µEDM presents a streamlined and single-stage fabrication technique for MEAs. Notably, Sun et al.18 pioneered the creation of an 8 × 8 cylindrical array of microelectrodes, boasting a diameter of approximately 185.18 μm and a length spanning 2168.79 μm, employing the self-finishing method. This method’s effectiveness was assessed, evaluating the precision of size, surface morphology, and surface roughness parameters within the machined cylindrical array micro holes. On the other hand, Dharmadhikari et al.,8 harnessed cost-effective sieves as electrodes, successfully producing textured surfaces featuring pillars of varying cross-sectional dimensions. By implementing a bubble flushing technique, they achieved a noteworthy 20–25% enhancement in material removal rate and a 15–18% improvement in contact angle. This advancement successfully created an array of square rods, each measuring 200 μm in side length and 250 μm in length, on a 6 mm brass bulk rod. Suresh et al.19 explored Reverse-µEDM effects on MEAs and uncovered a decrease of 6.75% in diameter and a 3% increase in electrode taper with heightened process parameters. ANOVA analysis highlighted the significant impact of capacitance, voltage, and feed on array microelectrode geometrical attributes. Ashok et al.10 investigated Vibration-assisted µEDM, revealing that adjusting Toff from 25 to 35 µs yielded a substantial 23.23% increase in surface roughness. Similarly, increasing Ton from 140 to 160 µs resulted in a remarkable 25.85% improvement in circularity. Their analysis, utilising FESEM and EDS, provided insights into the microstructure and chemical composition of the machined specimens. A novel flushing approach proposed by Shah et al.20 exhibited the potential to significantly enhance the stability of µEDM dressing processes, surpassing cases without dielectric medium rotation. This advancement was evident through debris evacuation and process stability results, showcasing a potential increase of approximately 17% in normal pulses and a spindle retraction height reduction exceeding 98% with the highest dielectric rotational speed. Kishore et al.‘s21 focus on the Reverse-µEDM variant emphasises producing high-quality products. Grey relation analysis indicated that a duty cycle of 1.25% and a 20% current were optimal for achieving burr-free shallow striation micro-holes with minimal dimensional discrepancies. Delving into EDM’s influence on Inconel 625 superalloy, Deepesh et al.22 employed ANFIS to optimise material removal rate (MRR), surface roughness (SR), and tool wear rate (TWR), yielding high accuracy percentages of 95.55% for MRR, 90.35% for TWR, and 97.82% for SR. Chaki et al.23 uses soft computing for optimising the responses of hybrid CO2 mid-welding. Gangil et al.24 have reviewed modern optimisations like the genetic algorithm, firefly algorithm, and simulated annealing for optimising the EDM process parameters. Antar et al.25 contributed insights into EDM’s influence on surface quality and microstructural alterations across diverse materials. At the same time, Chen et al.26 conducted a comprehensive study, elucidating the intricate relationship between process parameters and resultant surface characteristics in µEDM. Despite substantial research on conventional EDM techniques, a notable gap remains in investigating the surface integrity of MEAs produced through Reverse-µEDM.

Existing literature mainly focuses on conventional EDM and surface integrity for macro-scale applications, while Reverse-µEDM for high-precision MEAs is found to be under critical explored. Additionally, the lack of comprehensive analysis using advanced characterization techniques and Taguchi design hinders a deeper understanding of the effects of process parameters on surface quality in Reverse-µEDM fabricated MEAs. In this study, Leave-One-Out Cross-Validation (LOOCV) approach is used to predict the surface roughness of MEAs with small set of experimental data and a comparative analysis of different machine learning models.

Experimental methodology

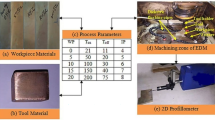

The experiments were conducted using the MIKROTOOLS DT110 hybrid micromachining centre (Mikrotools Pte Ltd, Singapore) as shown in Fig. 1c, specifically designed for precision microfabrication processes, including Reverse-µEDM. The setup comprises a high-precision worktable, a computer-controlled motion system, and a dedicated EDM power supply. A systematic approach was adopted to investigate the influence of key process parameters on the surface integrity of MEAs. The experiment’s L18 orthogonal array Taguchi design was chosen for its efficiency in minimising experimental runs while capturing the variation caused by different input combinations. The selected parameters and their respective levels are in Table 1.

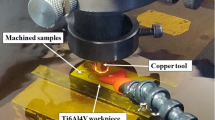

Tungsten (99.95%) workpieces of dimension diameter 3 mm \(\:\times\:\) length of 30 mm were selected for fabricating the MEAs. As the tool, a brass sheet of the size \(\:20\:\times\:20\times\:0.5\:\)mm was utilised. The copper sheet was predrilled as circular array holes of size 260 μm as in Fig. 1a to facilitate the fabrication of multiple MEAs in a single machining operation as in Fig. 1b. Conventional µ-drilling method is used for drilling small size holes on the tool plate. The microelectrode fabrication process involved placing the prepared brass sheet tool and the tungsten carbide workpiece in the specially designed fixture of machine tool setup. The RC pulse generator was used to generate controlled electrical discharges between the tool and the workpiece, leading to removing material from the workpiece to form MEAs. The flushing of ejected debris during machining is facilitated by used dielectric flow continuously at the machining gap. For present work, filtered hydrocarbon based NICUT LL21 E EDM oil has been used which has transparent appearance for better obseration of ejected debris. Based on the L18 orthogonal array, 18 experimental runs were conducted, each corresponding to a unique combination of the selected input parameters (voltage, capacitance, and feed rate). Each run’s machining process was repeated to create MEAs on the workpiece surface.

The fabricated MEAs were subjected to extensive surface integrity analysis using multiple characterisation techniques. An optical microscope was employed to observe the arrays’ macroscopic features and overall quality. This article investigates the microstructure and finer surface details; a Scanning Electron Microscope (FESEM) was utilised, providing high-resolution imaging. Furthermore, a non-contact profilometer, ZYGO NON-VIEW 9000, was used to quantify the MEAs’ surface roughness, as in Table 2. The data obtained from the surface integrity measurements were analysed statistically using ANOVA to evaluate the influence of each input parameter on the microelectrode array’s surface quality. The analysis involved assessing the main effects of the parameters and identifying any potential interactions between them. Noetworthy to mention here that the repeatability of the experiments was ensured by conducting three trials for each experimental run and calculating the average values of the surface integrity parameters.

Results and discussions

Analysis of surface roughness

In analysing the MEAs’ surface roughness data using ANOVA are given in Table 3, the significance of individual parameters was evaluated by calculating p-values. These p-values provide insight into the probability of observing extreme results assuming no actual effect as shown in Fig. 5. A p-value below 0.05 indicates that the parameter significantly influences the response variable, whereas a higher p-value suggests insignificance. Examining the specific parameters: Capacitance: The p-value (< 0.05) underscores the substantial influence of capacitance on the surface roughness of MEAs produced using Reverse-µEDM. Alterations in capacitance lead to discernible changes in surface quality. Voltage: Similarly, the p-value (< 0.05) signifies the noteworthy impact of voltage on MEAs surface roughness. Voltage adjustments directly correlate with the machining process, yielding distinct outcomes in surface quality. Feed Rate: In contrast, the p-value (> 0.05) suggests that variations in feed rate do not exhibit statistical significance within the studied parameters. Adjustments to feed rate have minimal effects on surface quality within this parameter range. Assessing Contribution Percentages and Model Fit: Additionally, contribution percentages were computed for each input parameter, quantifying their respective contributions to the variability in surface roughness:- Voltage: Approximately 11%; Capacitance: Significantly higher, around 86%; Feed rate: Negligible, at approximately 0.2% The goodness of fit of the statistical model was evaluated using R-squared, adjusted R-squared, and predicted R-squared: R-sq: 95.24%, indicating that the model captures about 95.24% of the variability in surface roughness. R-sq(adj): 94.09%, reflecting the adjusted R-squared value considering the model’s complexity. The Table 4 presents the outputs of ANOVA technique depicts the percentage contribution of the input parameters alongwith the evidenced percentage error in the analysis. R-sq(pred): 93.80%, estimating the model’s predictive accuracy for future observations. the Shapiro–Wilk test on the model residuals to formally assess the normality assumption. The test yielded a statistic W = 0.964 and a p-value of 0.68, indicating no significant deviation from normality (p > 0.05). Thus, we fail to reject the null hypothesis that the residuals are normally distributed, supporting the validity of regression assumptions for our dataset.

The surface integrity analysis using the non-contact profilometer ZYGO NON-VIEW 9000 results in Fig. 2a provides a comprehensive understanding of the surface roughness characteristics of the MEAs produced through Reverse-µEDM. The standard deviation plot to analyze the recoded experimental uncertainity is given in Fig. 2b for each measured surface roughness values.

Figure 3 illustrates the assessment of surface roughness data via an extensive residual analysis. This analysis encompassed various diagnostic plots designed to appraise both the model fit and underlying assumptions of the experimental outcomes. The normal probability plot in the evaluation displayed a prominent alignment of data points along a linear trajectory. Notably, over 90% of residuals fell within the bounds of quantiles representative of a normal distribution. This alignment corroborated the substantial fulfilment of the normality assumption concerning the residuals. The verses plot demonstrated a stochastic dispersion of residuals around the zero mark, indicating a satisfactory concordance between model prognostications and empirical observations. This dispersion pattern suggested the residual variance’s consistent maintenance across the spectrum of fitted values.

The main effect plot, as in Fig. 4, provides a comprehensive visual representation of the influence of capacitance, voltage, and feed rate on the surface roughness of MEAs fabricated using Reverse-µEDM. The plot underscores the substantial impacts of capacitance and voltage on surface roughness, indicating that feed rate has a comparatively minor effect. The main effect line corresponding to capacitance demonstrates a clear positive trend. As capacitance increases, there is a noticeable rise in surface roughness. It indicates that higher capacitance settings result in more aggressive material removal during the Reverse-µEDM process, increasing surface irregularities and roughness. The main effect line for voltage depicts an upward trajectory. As voltage increases, there is a corresponding increase in surface roughness. This analysis reinforces the critical importance of precise parameter control in achieving the desired surface quality for MEAs in various microfabrication applications.

The contour plot in Fig. 5 visually explains the complex connection between surface roughness and two vital input factors: voltage and capacitance. The plot displayed surface roughness values on its contours, unveiling the impact of changes in these parameters. Voltage ranged from 90 to 130 V, while capacitance varied from 10 to 100 nF. The resulting plot depicted their combined effect on roughness. Increasing voltage (90–130 V) and capacitance (10–100 nF) caused surface roughness to consistently increase. Contour lines on the plot showed a slight upward slope, indicating higher roughness with elevated voltage and capacitance. At 130 V and 100 nF, contour lines converged, marking the peak roughness at 11.1 μm. This visualisation effectively conveyed how voltage and capacitance influence surface roughness, emphasising the rising trend with higher values. The convergence of lines highlighted their critical role in microelectrode array quality in Reverse-µEDM fabrication, aiding parameter optimisation for desired results.

Figure 6 depicts a comprehensive microscopic illustration capturing the surface of MEAs that have been manufactured under specific process conditions, featuring a capacitance of 100 nF, a voltage of 130 V, and a feed rate of 15 μm/s at 5000 magnification and the observation has been done at the centre of the MEAs surface. Substant craters are evident upon the surface, indicating significant material elimination during the Reverse-µEDM process. These distinctive depressions most likely originate from localised material disintegration induced by high-energy discharges between the tool and workpiece. The accrual and decomposition of material can be attributed to the re-solidification of molten material expelled during these discharges. This accumulation can induce surface irregularities and, conceivably, compromise the electrical performance of the MEAs.

Predictive analysis of surface roughness

This study aims to predict the surface roughness (µm) of a material from three input features (capacitance (nF)), voltage (V), and feed rate (µm/s)) using five machine learning models: an Artificial Neural Network (ANN), Support Vector Regression (SVR), Random Forest (RF), Gradient Boosted Trees (GBT), and Gaussian Process Regression (GPR). The data consist of 18 experimental observations (two capacitance levels \(\:\times\:\:\)three voltage levels \(\:\times\:\) three feed rates). Due to the small sample size, we use leave-one-out cross-validation (LOOCV) to estimate predictive performance. LOOCV is a special case of k-fold cross-validation with k equal to the number of data points; it yields an almost unbiased estimate of model accuracy when data are limited27,28,29. The Methodology that we adopted to pridict the surface roughness is shown in Fig. 7.

Methodology adopted for prediction of of surface roughness

For the Data and Preprocessing, We first prepared the features and target. The input features are Capacitance, Voltage, and Feed, and the target is Surface roughness. We standardized (Z-score normalized) the features for models sensitive to scaling (ANN, SVR, GPR). Z-score normalization subtracts the mean and divides by the standard deviation so each feature has mean 0 and variance 1. This is important for indegeneous developed algorithms like SVR and neural networks that assume features on similar scales. (Tree-based models RF and GBT are scale-invariant, so we did not scale their inputs.) In this study, not any polynomial or interaction features has been included, to avoid overfitting given the small dataset.

Cross-Validation: We used LOOCV for model evaluation. In LOOCV, each of the 18 samples is held out in turn as the test set while training on the remaining 17. This yields 18 fitted models per algorithm, with predictions aggregated across folds. LOOCV is computationally expensive but appropriate for small datasets. It ensures each point is tested exactly once, providing a nearly unbiased performance estimate for each mode30,31. For Models and Hyperparameters, Each model’s key settings and tuning strategy as shown in Table 5.

-

ANN (MLPRegressor): A feedforward multi-layer perceptron regressor. We used one hidden layer (with 5, 10, or 20 neurons) and varied the L2 regularization term (alpha) via grid search. Training used the L-BFGS optimizer for convergence on small data.

-

SVR: Support Vector Regression with an RBF (Gaussian) kernel. We tuned the penalty parameter C, the epsilon-insensitive margin ε, and the kernel scale parameter (gamma) using grid search. SVR fits a regression hyperplane by maximizing the margin around an ε-tube.

-

RF: Random Forest regressor. We tuned the number of trees (n_estimators), maximum tree depth, and minimum samples per leaf. Random forests build an ensemble of decision trees on bootstrapped subsets and average their outputs to reduce variance.

-

GBT: Gradient Boosted Trees (GradientBoostingRegressor). We tuned the number of boosting stages (n_estimators), learning rate, and tree depth. GBT builds trees sequentially, each fitted to the residuals of the previous model (a stage-wise additive procedure).

-

GPR: Gaussian Process Regression. We used a standard RBF kernel (with automatic length-scale optimization) and enabled output normalization. GPR is a non-parametric Bayesian method that models the output as a Gaussian process; it provides a predictive mean and uncertainty (standard deviation) for each prediction.

Each model was wrapped in a pipeline (including scaling for ANN/SVR/GPR) and optimized via grid search with LOOCV (using scikit-learn’s GridSearchCV with cv = LeaveOneOut) through in-house developed python code. The best hyperparameters (selected by LOOCV performance) are reported in the results Table 6.

To evaluate each model’s performance on the held-out observations (aggregated across the LOOCV folds) using:

Coefficient of determination (R2): the proportion of variance in surface roughness explained by the model. R2 ranges from 0 to 1 (higher is better) and represents the fraction of outcome variability accounted for by the predictor.

Mean Absolute Error (MAE): the average absolute difference between predicted and true roughness. Lower MAE indicates better accuracy.

Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE): the square root of the mean squared prediction error, which penalizes larger errors more strongly. Lower RMSE is better.

Training time: the wall-clock time to perform hyperparameter tuning and LOOCV training (on our hardware). This reflects computational cost; faster models may be preferred in practice even if accuracy is similar.

Each metric was computed on the full set of LOOCV predictions against true values. For example, MAE = (1/N)∑|y_true – y_pred|, and RMSE is the square root of average squared error. R2 and MAE formulas can be found in standard references31.

Results and discussions

The optimized hyperparameters and LOOCV performance for each model are summarized below. Sequentially, the predicted results for minimum mean absolute error (\(\:MAE\)), root mean square error (\(\:RMSE\)), the coefficient of determination (\(\:{R}^{2}\)) for comprehensive assessment of model accuracy and robustness. The statistical formulation of \(\:MSE\), \(\:RMSE\), and \(\:{R}^{2}\) are provided in Eqs. (1–3

):

The table reports each model’s key tuned settings, cross-validated R2, MAE, RMSE, and total training time (seconds) as shown in Table 6.

The Random Forest model achieved the highest accuracy (R2 = 0.975) and lowest errors (MAE = 0.178, RMSE = 0.287 μm), indicating that RF model gives best prediction to the true surface roughness of MEAs as shown in Fig. 8. The ANN was a close second (R2 = 0.971). In contrast, GBT performed poorly (R2 = 0.482, very high error), likely due to underfitting with shallow trees in this small dataset. SVR and GPR gave moderate performance (R2 = 0.743 and 0.787). Training time varied: RF was slowest (65 s) due to many trees in CV, while GPR was fastest (< 0.01 s) because it had essentially no grid search.

The results show clear differences between models. Random Forest (RF) performed best, likely because averaging many trees reduced variance and captured nonlinear interactions without overfitting. The high R2 (0.975) suggests RF fitted the pattern of roughness well despite the small sample. ANN (MLP) also captured the trend well, benefiting from feature scaling; however, its cross-validated training was computationally intensive (tens of seconds). The SVR model was slower to train than GPR but less accurate; SVR often requires careful kernel tuning and can underperform if not properly regularized. Gaussian Process Regression (GPR) delivered a probabilistic prediction (with uncertainty), but its point estimates were less accurate than RF/ANN. GPR’s moderate R2 (0.787) may reflect mismatch of the assumed smooth kernel with the data or limited data for kernel learning.

The poor GBT performance may be due to the small dataset and limited tree depth; boosting often requires tuning of both learning rate and depth. In our grid search, the best GBT used very shallow trees and a low learning rate, which likely underfit the relationship. This highlights that more complex models do not guarantee better fit on limited data.

Across models, scaling proved important: ANN, SVR, and GPR used Z-score normalization to ensure numeric stability and convergence (as recommended for gradient-based and distance-based methods). For example, feature scales differed by orders of magnitude (Capacitance 10–100 vs. Feed 5–15), so normalization helped the ANN training. Tree-based methods (RF, GBT) do not require scaling and indeed perform implicit feature selection.

All models were evaluated with R2, MAE, and RMSE on the same held-out data so comparisons are fair. These metrics are standard for regression: R2 measures explained variance, while MAE and RMSE quantify average prediction error (RMSE penalizing large errors). In our results, models with higher R2 consistently had lower MAE/RMSE, as expected.

The substantially higher training time for RF (65 s) reflects exhaustive grid search and many trees in LOOCV; in practice one might use fewer combinations or parallel computation to speed this. Conversely, GPR’s near-zero time is deceptive: GPR fitting per LOOCV fold is fast here because N = 17 training points, but GPR scales poorly for larger datasets.

The feature importance plots as shown in Fig. 9 for the Random Forest model using both Gini importance and permutation importance. As shown below, capacitance is by far the most influential feature for predicting surface roughness, followed by voltage, with feed rate having minimal impact. This finding is consistent with our ANOVA results, where capacitance contributed 86% to surface roughness variation, confirming the physical relevance of the model’s predictions.

Conclusion

This study presents a comprehensive investigation into the fabrication of MEAs using the Reverse micro-electrical-discharge machining (Reverse-µEDM) method, coupled with various ML models for predicting the surface roughness. The results highlight the promising capabilities of Reverse-µEDM as a manufacturing technique for producing high-performance MEAs with exceptional precision and accuracy.

-

The ANOVA analysis reveal that capacitance and voltage significantly impact the surface roughness, underscoring their role in determining the quality of the fabricated MEAs. Conversely, the feed rate exhibits minimal effects on surface roughness.

-

Within the parameter space ranging from 10 nF, 90 V, and 5 μm/s to 100 nF, 130 V, and 15 μm/s, the variation in surface roughness spans from 6 to 12 μm. This observation underscores the sensitivity of the fabrication process to parameter adjustments and highlights the need for meticulous parameter tuning to achieve desired surface characteristics.

-

In this comparative analysis, Random Forest Regression gave the best predictions of surface roughness, with near-perfect R2 and low error (MAE = 0.18 μm). The Neural Network was nearly as good but slower to train. SVR and GPR offered moderate accuracy; Gradient Boosting performed worst on this small dataset. LOOCV provided robust performance estimates despite limited data. Our results suggest that ensemble trees or neural nets are effective for this task, whereas boosting may require larger data.

-

All models should be retrained on any new data to confirm generalization. Future work could explore adding more data or features, but care must be taken to avoid overfitting given the small sample size.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Obien, M. E. J. et al. Revealing neuronal function through microelectrode array recordings. Front. Neurosci. 8 https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2014.00423 (2015).

Singh, G., Pandey, P., Mohan & Singh, N. Surface roughness study in cryogenic EDM of tool steel using novel copper electrode with channels fabricated by additive manufacturing. Mater. Manuf. Process. 40, 639–652. https://doi.org/10.1080/10426914.2025.2462833 (2025).

Soni, H. Experimental investigation on effects of wire electro discharge machining of Ti50Ni45Co5 shape memory alloys. Silicon. 10, 2483–2490. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12633-018-9780-9 (2018).

Chanie, S. E., Bogale, T. M. & Siyoum, Y. B. Optimization of wire-cut EDM parameters using artificial neural network and genetic algorithm for enhancing surface finish and material removal rate of charging handlebar machining from mild steel AISI 1020. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 136, 3505–3523. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00170-025-15034-8 (2025).

Pratap, P. S, Datta, S. & Sharma, V. Controlling recast layer and material removal in reverse µEDM for sustainable fabrication of microelectrode arrays. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part. E J. Process. Mech. Eng. https://doi.org/10.1177/09544089241234499 (2024).

Pratap, S., Datta, S. & Sharma, V. Determination of surface roughness of micro rods fabricated by reverse µEDM using dimensional analysis. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 128, 3649–3659. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00170-023-12131-4 (2023).

Ravasio, C. & Pellegrini, G. Effects of the dielectric flow rate of internal washing on micro-EDM drilling performance. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 136, 5257–5270. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00170-025-15185-8 (2025).

Cao, H-T. et al. Characterization of machined surface in semi-conductive SiC wafer subjected to micro-EDM drilling. Mater. Sci. Semiconduct. Process. 187, 109118. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mssp.2024.109118 (2025).

Shukla, S., Sisodiya, M. S. & Bajpai, V. Analytical modelling of material removal rate and surface finish in Maglev EDM on Ti-6Al-4 V. Microsyst. Technol. 31, 659–673. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00542-025-05853-w (2025).

Manoj, I. V. et al. Examination of machining parameters and prediction of cutting velocity and surface roughness using RSM and ANN using WEDM of altemp HX. Adv. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2022, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1155/2022/5192981 (2022).

Pratap, S. & Datta, S. Surface integrity of tungsten carbide microelectrodes fabricated using reverse micro-EDM by varying electrode materials. Mater. Today Proc. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matpr.2023.08.352 (2023).

Ferguson, M., Sharma, D., Ross, D. & Zhao, F. A critical review of microelectrode arrays and strategies for improving neural interfaces. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 8, 1900558. https://doi.org/10.1002/adhm.201900558 (2019).

Kim, B. H., Park, B. J. & Chu, C. N. Fabrication of multiple electrodes by reverse EDM and their application in micro ECM. J. Micromech. Microeng. 16, 843–850. https://doi.org/10.1088/0960-1317/16/4/022 (2006).

Mastud, S. A., Garg, M., Singh, R. & Joshi, S. S. Recent developments in the reverse micro-electrical discharge machining in the fabrication of arrayed micro-features. In Proceedings of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers, Part C: Journal of Mechanical Engineering Science, vol. 226, 367–384. https://doi.org/10.1177/0954406211424672 (2012).

Meacham, K. W., Guo, L., DeWeerth, S. P. & Hochman, S. Selective stimulation of the spinal cord surface using a stretchable microelectrode array. Front. Neuroeng. https://doi.org/10.3389/fneng.2011.00005 (2011).

Kaushik, A. et al. Experimental investigation on cladding with metal cored wire using GMAW process and parametric optimization. Eng. Res. Express. 3, 045025 (2021).

Soni, H. et al. Development of Ti50Ni50 – XCox (X = 1 and 5 at. %) shape memory alloy and investigation of input process parameters of wire spark discharge machining. In Intelligent Manufacturing (ed Pathak, S.) 77–97 (Springer International Publishing, 2021).

Sun, Y. et al. Evaluation of dimensional accuracy and surface integrity of cylindrical array microelectrodes and cylindrical array microholes machined by EDM. Arch. Civ. Mech. Eng. 22, 46 (2022).

Pratap, S. & Datta, S. Fabrication of array microelectrodes: achieving geometrical characteristics using reverse micro-EDM process. Phys. Scr. 98, 085003 (2023).

Shah, M. S. et al. A novel Flushing technique to improve micro-EDM dressing process stability: assessment through analyzing debris evacuation. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 1–20 (2023).

Kishore, H., Nadda, R., Nirala, C. K. & Agrawal, A. Modelling and simulation based surface characterization of Reverse- µEDM fabricated micro Pin-fins. Proc. CIRP. 81, 1230–1235. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.procir.2019.03.299 (2019).

Sharma, D., Bhowmick, A. & Goyal, A. Enhancing EDM performance characteristics of inconel 625 Superalloy using response surface methodology and ANFIS integrated approach. CIRP J. Manuf. Sci. Technol. 37, 155–173 (2022).

Chaki, S., Shanmugarajan, B., Ghosal, S. & Padmanabham, G. Application of integrated soft computing techniques for optimisation of hybrid CO2 laser–MIG welding process. Appl. Soft Comput. 30, 365–374. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asoc.2015.01.045 (2015).

Gangil, M., Pradhan, M. K. & Purohit, R. Review on modelling and optimization of electrical discharge machining process using modern. Tech. Mater. Today Proc. 4, 2048–2057. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matpr.2017.02.050 (2017).

Antar, M., Hayward, P., Dunleavey, J. & Butler-Smith, P. Surface integrity evaluation of modified EDM surface structure. Proc. Cirp. 68, 308–312 (2018).

Chen, Q. & Thouas, G. A. Metallic implant biomaterials. Mater. Sci. Eng. R: Rep. 87, 1–57 (2015).

Singh, R. K. et al. Study on temperature and hardness behaviors of Al-6060 alloy during magnetic abrasive finishing process using artificial neural networks. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 30, 6092–6107. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmrt.2024.05.039 (2024).

Sharma, P. et al. Surface characterization of SAE 304 after WED cutting: an experimental investigation and optimization. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 23, 5723–5732. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmrt.2023.02.183 (2023).

Montgomery, D. C., Peck, E. A. & Vining, G. G. Introduction To Linear Regression Analysis (Wiley, 2021).

Manoj, I. V. et al. Artificial neural network-based prediction assessment of wire electric discharge machining parameters for smart manufacturing. Paladyn. J. Behav. Rob. 14 https://doi.org/10.1515/pjbr-2022-0118 (2023).

Hastie, T., Tibshirani, R., Friedman, J. H. & Friedman, J. H. The Elements of Statistical Learning: Data Mining, Inference, and Prediction (Springer, 2009).

Funding

There is no funding received for carrying out this project work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.P.: Conceptualization, methodology, writing, original draft, review and editing, data curation. P.K.: Review and editing, H.K.: Writing, review and editing, data curation, S.D.: Review and project administration, A.B.H.: Final decision, review, data curation.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Pratap, S., Kumar, P., Kishore, H. et al. Predictive modeling and optimization of surface roughness in Reverse-µEDM fabricated microeletrode arrays using ML models. Sci Rep 16, 490 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-13269-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-13269-9