Abstract

The solar air heater (SAH) is typically used for drying industrial and agricultural products; however, its application in high-temperature processes is limited due to low thermal efficiency. This study aims to augment the performance of SAH by introducing V-shaped baffles with three different perforation configurations: square, rectangular, and a combination of both. To determine which of the three V-baffle designs had the best perforation, CFD simulations were conducted. The final perforation was selected based on the CFD data, and the system was then constructed for experimental study. CFD results show that using a V-shaped baffle with a square and rectangular perforation combination provides the best output temperature than the other two designs. Using this perforation, study were performed at varying mass flow rates such as 0.0230, 0.0307, and 0.0384 kg/s. The results showed that the average output air temperature of 47, 51 and 52 °C while using the V baffle with combined perforation and the average useful power obtained by the proposed SAH is 244.35 W, 448.17 W, and 585.37 W, respectively, for the given flow rates. The maximum increase in useful power was observed to be 26%, 29%, and 28% higher than conventional SAH. Also, this proposed SAH has 10%, 19%, and 24% less average top surface heat loss than conventional SAH and has 5%, 13%, and 14% higher efficiency than conventional SAH for the given flow rates. The environmental and economic study also reveals that the proposed design has 12.36% less payback time and 12.6% higher production factor than conventional SAH.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Enhancing the performance of renewable energy systems has been the focus of a lot of investigation due to the global trend toward sustainable energy alternatives. Among these, solar energy is a standout option for a number of thermal applications because of its widespread availability and eco-friendliness. SAH is mainly used for agricultural products drying, space & domestic hot water heating and industrial processing applications. Conventional SAH can’t be used for industrial needs due to its deprived transfer of heat among the air and collector through convection mode. Because this poor heat transfer reduces the system efficiency and output temperature1. There are numerous ways to enhance SAH performance, including adding artificial arrangements to rectangular flat plates, employing extended substrates, and using bed absorbers packed with holes. One of the technique to improve system performance is to artificially roughen the rectangular absorber panel of a SAH with a perforated baffle2.

Singh et al.3 assessed the thermal efficiency of a serpentine wavy channel SAH. They determined that an air flow of 0.04 kg/s gives the maximum efficiency. An absorber plate with conductive aluminium tubes has an optimal efficiency of 40.3% at a rate of 0.025 kg/s, according to Abo-Elfadl et al.4 for a double-pass SAH. Hegazy et al.5 claim that, at a rate of 0.02 kg/s, a hybrid PV/T double-pass finned plate SAH may attain the highest thermal efficiency, at 64%. Madhu et al.6 estimated the process of a SAH with staggered ribs covered in CNT. They found a maximum daily efficiency of 41.18% for the device. Varshney et al.7 examined the SAH’s distinctive heat transmission and fluid flow caused by ducts filled with wire mesh. They concluded that heat transfer and friction are crucial factors affecting SAH efficiency. In a study by Kumar et al.8S ribs were used to reduce friction and increase heat transfer in a SAH. Advancements were observed in heat transfer and friction factors. To increase efficiency, Singh et al.9 added transverse ribs to an SAH having an irregular square wave section. They assert that the friction factor (f) and Nusselt number (Nu) are 3.55 and 2.14 times higher than the conventional SAH. The average Nu and f are 4.52 and 3.13 times greater than smooth ducts in an experiment by Ravi and Saini10 that used staggered and separate V-shaped ribs on double-pass SAH ducts. Singh et al.11 reported that SAH exhibits an increase in Nu and f value of 1.55–2.26 and 2.63–3.40 times that of flat SAH. With regard to Nu and f, Kumar et al.12 determined that a SAH with integrated coarseness on the plate outperformed smooth plate air heaters by 2.46 and 1.78 times, respectively. When the roughness pitch is 12, Jain et al.13 demonstrated that a SAH with V geometry exhibits the best thermo-hydraulic results. The Nusselt number for a SAH with an arc gap and V shape is higher than that of a SAH14. As for the coarseness of the collector plate, Kumar et al.15 used a winglet-type vortex generator with arrangements. They concluded that the proposed plate improves the f and Nu. Luan et al.16 reported the maximum effective efficiency to be 63% at a Re value of 24,000, for solar air heaters with ribs inclined between 60 and 1200 degrees. Kumar et al.17 used liquid crystal thermography technology to augment the efficiency of the winglet-style SAH. To increase the thermohydraulic parameters (THP) of SAH, Singh et al.18 employed inclined, transverse, and V ribs on the rectangular plate. They found that, regarding of overall THP, the SAH with inclined ribs surpasses the SAH with transverse ribs. They added that, contrasted to transverse and inclined ribs, V shaped ribs exhibit improved THP. In a study of a SAH, Singh19 tested the thermo-hydraulic and thermal behavior of Model-I (semicircular) and Model-II (triangular) cross-sectioned ducts. The model-I duct’s thermal and thermohydraulic efficiency was 3–5% advanced than the model-II duct’s. To enhance the THP of the SAH, Saravanakumar et al.20 used arc ribs incorporated with various baffles and fins. They demonstrated that the suggested system’s maximal thermal efficiency is 81.9%. Compared to the arc ribs SAH, this efficiency improvement is higher by 28.3%. The hydraulic and thermal efficiency of SAH was increased by Bensaci et al.21 by varying the placement of baffles above the absorber plate. Baffles were utilised in four configurations: 100% on the absorber plate, 50% above, 50% down, and 50% in the middle. According to the authors, baffles increase thermal efficiency.

The absorber plate with twisted rib roughness has the largest increase in exergy, effective, and thermal efficiencies, at 1.79, 1.81, and 1.81 times over the conventional plate, according to a numerical optimization by Kumar et al.22 for SAH’s exergy and energy efficiencies. A novel curved double-pass SAH with asymmetric semicircular and circular ribs was proposed by Kumar et al.23. It was demonstrated that the efficiency was augmented more by the asymmetric semicircular ribs than by the circular ribs. A computational fluid dynamic (CFD) & energy study of a triangular SAH with V-ribs were done by Nidhul et al.24 The effectiveness parameter of this SAH system falls within the range of 1.32 to 2. Jain et al.25 tested the use of V ribs on the collector plate on a SAH. It was found that having the V rib on the SAH with optimized dimensions provides better thermal efficiency and lower frictional characteristics than other shapes. In a research on solar air heaters, Vijayakumar et al.26 used V-up perforated baffles, which produced efficiency gains of 13%, 11.97%, and 3.06% over conventional air heaters for the examined air flow rates. For their investigation, Vijayakumar et al.27 used broken V ribs placed over a collection plate. They discovered that their efficiency was 15.7–20.4% greater than that of the traditional SAH. Singh et al.28 explored multi-V ribs that were perforated in air heaters. The study’s conclusion demonstrates a thermo hydraulic performance parameter that is 9.66 times more than that of multi-V ribs with a plain wall. Rahul Kumar et al.29 tested the efficiency of triangular SAH with irregularity in the form of V shape. According to this study, the efficiency of a triangle SAH with V shaped roughness was 75.31%. Raturi et al.30 tested the performance of Return Flow SAH with V ribs. This study gave 33.70% higher efficiency than the SAH without a baffle.

Previous studies have shown that introducing roughness elements such as ribs, baffles, and dimples on the collector surface can significantly enhance the thermal performance of SAHs compared to smooth duct configurations. Although several studies have investigated solar air heaters with roughness, limited work has been done on the combined effect of square and rectangular perforated V-baffles. Moreover, few studies integrate both experimental and CFD analysis along with energy and enviro-economic evaluation. The present study addresses this gap by examining the thermal and enviro-economic performance of a solar air heater equipped with continuous V-shaped baffles featuring combined square and rectangular perforations. These perforations are intended to increase turbulence and air mixing, thereby extending air residence time and improving convective heat transfer between the absorber plate and the working fluid. This study evaluates the system through both CFD simulations and experimental analysis under various mass flow rates. In addition to assessing thermal efficiency, the environmental and economic implications of the modified SAH are analyzed through emission mitigation metrics (SO₂, NO, and CO₂), offering a complete view of its sustainability potential.

Methodology

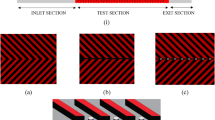

The SAH ‘s suitability was analyzed for the climate conditions of Kovilpatti, Tamilnadu over the last five years. Eight geometries are modelled and analysed in each perforated V rib to determine the apex dimensions for square, rectangular, and a combination of square and rectangular form perforation in V ribs. The V-ribs perforated with square, rectangular and a combination of square and rectangular shapes are denoted as Models I, II, and III. Design representations of all the models are shown in Fig. 1. Specifications of the three different baffles and dimensions used for the system were shown in Table 1. CFD analysis is carried out for the geometries of all the model’s absorber plates using FLOEFD software version 2016. RANS models, especially the k-ε model, are used for the CFD studies because these models were widely used for simulating internal duct flows with heat transfer. It offers a good balance between accuracy and computational effort. Since the main goal of this work is to predict the outlet air temperature and analyzing the internal flow inside the SAH, the standard k-ε model was considered appropriate and sufficient for capturing the overall flow and output temperature.

A CFD examination was conducted to decide the model for better air heater performance. The air heater system is fabricated and tested for the proposed model III absorber plate with CFD as per ASHRAE standard 93. The specifications of the SAH for the model III collector plate are given in Table 2. Input parameters like solar radiation, air flow rate, and air temperatures were used to find the air’s output temperature experimentally. The centrifugal blower delivers air into the duct at a rate of 0.0230, 0.0307 and 0.0384 kg/s. The selected mass flow rates were based on our earlier experimental study26where these values were found to be suitable for testing under typical solar conditions. These rates represent low, medium, and high airflow levels achievable with the same blower system and allow consistent comparison across studies. The blower has a speed of 2800 rpm and a power of 1 HP (750 W). The inlet tube area, density of air, and the intake air velocity provided by the blower were used to compute the air flow rate. The inlet air velocity is controlled using the control valve in the blower to change the flow rate. A thermocouple (K-type) is used to find the output air temperature of the SAH. outlet temperature of air, temperature of absorber at four various points, and glass temperature at two different points of the SAH are recorded using a data acquisition system, every 30 min from 8 a.m. to 6 p.m. during March at the National Engineering College Energy Park. Table 3 provides the specifications and limits of the employed instruments. Output parameters like thermal efficiency, useful power, top loss and heat transfer characteristics are evaluated using the air output temperature of the SAH. The experimentally measured output air temperature of the SAH system with the model III collector plate is compared with the CFD results for the same model. The methodology adopted for the proposed study is shown in Fig. 2.

CFD analysis

Assumptions and boundary conditions

The following assumptions are made in the study (Yadav et al.31):

-

1.

The fluid moves in a constant, two-dimensional, fully formed, turbulent manner.

-

2.

The absorber plates and the baffles’ thermal characteristics are constant.

-

3.

No mass transfer and internal heat generation occur.

-

4.

Radiation heat transfer and additional losses can be neglected.

Limits applied

The temperature of air output for the SAH is determined using CFD analysis using the following limits as inputs:

-

1

Inlet velocity of air is 20 m/s.

-

2

The air inlet temperature is 30 °C.

-

3

The solar radiation intensity is 800 W/m2.

-

4

The pressure at the outlet (considered as atmospheric pressure).

-

5

Heat transmission from other duct walls can be neglected.

Physical model

Solar air heaters using different collector plates (one with a flat surface and the other with a V perforated baffle fixed to the absorber) are modelled using Solid Works – version 2017. At the typical bulk temperature, it is assumed that the characteristics of the absorber plate’s aluminium content and the incoming fluid (air) conditions remain constant. The domain’s meshing is produced with the software FloEFD - Version 2016. A uniform mesh with the ideal mesh size resolves the laminar sub-layer near the wall surface. ANSYS Meshing was used to generate a structured hexahedral mesh for the computational domain. The total number of cells was approximately 1.2 million, with an average cell size of 5 mm. Local mesh refinement was applied near the absorber plate, baffle surfaces, and duct walls to accurately capture thermal and flow gradients. The continuity, energy, and momentum equations govern the flow phenomenon in the duct of the SAHs. To ensure solution accuracy, a mesh independence study was conducted by comparing outlet air temperatures using three mesh densities: coarse (0.75 million cells), medium (1.2 million cells), and fine (2.1 million cells). The outlet temperature difference between the medium and fine meshes was found to be less than 1%, confirming mesh independence. As a result, all simulations used the medium mesh.

For the proposed Model I, Model II, and Model III SAHs, CFD is performed using FLOEFD 2016 to find the optimal design. Figure 3 displays the CFD findings for standard smooth plate air heaters. The air’s maximum exit temperature is measured to be 48.01 °C. Figures 4 and 5, and 6 display the CFD findings for Models 1, II, and III, respectively. Models I, II and III provide maximum air outlet temperatures of 52.50, 53 and 53.49 °C. The SAH with a combination of square & rectangular perforated baffles exhibits the highest air outlet temperature (53.49 °C) among the three proposed models.

Governing equations for CFD

The continuity equation ensures that mass is conserved in the air flow.

ρ is the fluid density (kg/m³), v is the velocity vector (m/s), and t is time (s),

The Navier-Stokes equations describe the motion of air substances and are the fundamental equations for fluid flow.

p is the pressure (Pa), µ is the dynamic viscosity (Pa·s), f represents body forces.

The energy equation governs the transfer of thermal energy in the system. In CFD, it is typically expressed as:

T is the temperature (K or °C), cp is the specific heat capacity at constant pressure (J/kg·K), k is the thermal conductivity (W/m·K), Q represents any internal heat sources (W/m³).

CFD simulations model turbulence via Reynolds-averaged Navier-Stokes (RANS) equations. The k-ε turbulence model is commonly used and can be represented as:

k is the turbulent kinetic energy (m²/s²), ϵ is the turbulence dissipation rate (m²/s³), Pk is the generation of turbulence kinetic energy due to mean velocity gradients, µt is the turbulent viscosity (calculated from the turbulence model).

These equations help model the turbulent flow characteristics within the system, which are critical in accurately predicting airflow and heat transfer in the solar air heater.

According to the CFD findings, the flat-plate SAH system has a smaller temperature gain than other perforated baffles, which shows that the establishment of a laminar sub-layer limits the enhancement of heat transfer in the SAH chamber. The flat surface SAH outlet temperature was 48.0 °C, which was followed by a rectangular perforation with an outlet temperature of 52.5 °C and succeeded by a square perforation with 53.0 °C, and finally, the combined profile obtained the highest temperature of 53.4 °C. Figures 3 and 4, and 5 illustrate the temperature delivery of the SAH setup for the proposed shapes of perforated baffles. The increases in outlet air temperature relative to inlet temperature for the Model III, II, and I cases, respectively, are 5.4 °C, 4.9 °C, and 4.4 °C. It is shown that the combined square and rectangular perforation in baffles yields higher air outlet temperatures. Based on the CFD results, the experimental setup is fabricated for the Model III absorber plate SAH. Experimental studies were conducted for the specified flow rate with model III absorber plate, as detailed in the Results and Discussion section, and the average outlet temperature obtained from the experiments was compared with CFD simulation results to validate the model in the following section. The experimental setup and the square and rectangular perforation baffle are presented in Figs. 7(a) and 7(b), respectively. Line diagram of the proposed SAH is shown in Fig. 8.

Energy matrix and Enviro-Economic study

Energy matrix and enviro-economic studies were carried out for the proposed Model III solar air heater (R. Naveenkumar et al.32 (A. Chakraborty et al.33. In this study, a thorough environmental and economic analysis using a range of monetary values was carried out for a number of solar air heating systems over a predetermined time period (n). The results are determined for the system’s lifetime, which is assumed to be 20 years. The system’s maintenance costs are assumed to be negligible. The SAH’s total embodied energy is estimated.

The energy payback period (EPT) can be expressed as follows:

where Ein denotes embodied energy of the SAH (kWh) and Eout annual energy output (kWh/yr) of the air system. EPT should be decreased for the whole installation service cycle for renewable energy applications. That is, EPT ⩽ nsys. EPT measures the air heater system’s efficiency throughout its service life.

The energy production factor (EPF) expressed as:

where \(\:{T}_{L}\) denotes lifetime of the system, while the life cycle conversion efficiency (LCCE) can be expressed as:

where \(\:{E}_{sol}\) denotes life-long solar radiation (in kWh).

Enviro-economic study

The environmental study focuses on emissions of contaminants, particularly CO2, NO and SO2. In general, 0.98 kg, 0.003 kg and 0.008 kg of CO2, NO and SO2, respectively, are to be released into the atmosphere from India’s coal power plants unit of electrical energy generated (in kWh). Annual CO2, NO and SO2 emissions for the plant lifetime are calculated using Eqs. 4, 5 and 6. by considering the 20% distribution losses and 40% transmission losses in India (Vijayakumar et al.34,35. Hence,

The annual CO2 mitigation (kg of CO2) is Eout× 1.58, where Eout is the annual energy accessible from the SAH. Therefore,

It is possible to exchange the net CO2 mitigation sum into the international market based on the EUR 11.09 international carbon price per tonne of CO2 or 9.99 US dollars per tonne of CO2 as per the date of 5.4.2020.

The SAH system used to reduce the carbon footprint that contributes to overall global warming occurs due to the CO2 emission in the environment.

Theoretical analysis

The given equations helped to derive the system energy gain, losses over the collector plate and other thermal performance of SAH as stated by Vijayakumar et al.36N. Lakshmaiya et al.37. The Hottel-Whillier-Bliss is applicable to estimate a SAH’s thermal efficiency.

where \(\:I\) intensity of radiation, \(\:{F}_{R}\) collector heat removal factor (in W/m2), \(\:{A}_{s}\) denotes absorber area (in m2, \(\:{\left(\tau\:\alpha\:\right)}_{e}\) effective absorbance and transmittance product, \(\:{U}_{L}\) overall heat transfer coefficient (in W/m2/K), \(\:{T}_{i}\) inlet temperature (in K) and \(\:{T}_{a}\) ambient temperature (in K).

The heat removal of absorber can be found using

where F’ is the factor of absorber efficiency.

The air flow rate is expressible as

This expression can be used to determine the working fluid’s mass flow rate.

The collector efficiency factor can be calculated as

or

and the overall loss coefficient as

Here, \(\:{U}_{t}\) is the top loss coefficient (in W/m2K), \(\:{U}_{b}\) is the bottom loss coefficient (in W/m2K), and \(\:{U}_{s}\) is the side loss coefficient (in W/m2K). Also,

where \(\:{T}_{g}\) denotes average glass surface temperature, \(\:{h}_{r}\) top surface radiation heat transfer coefficient (in W/m2K) and \(\:{h}_{w}\) wind heat transfer coefficient (in W/m2K).

The coefficient of radiation heat transfer can be computed using the following formula.

where

and εg is the emissivity of glass, σ is the Stefan Boltzmann constant (5.667*10−8 W/m2.K4), and Ts is effective sky temperature. Also, Ta is the ambient temperature (in K).

The wind heat transfer coefficient at the top cover (hw) has the following empirical relation:

where Vw is the velocity of the wind in m/s.

The rate of energy gain in the solar air heater duct by flowing air can also be determined as follows:

where \(\:{Q}_{u}\) is the energy gain from the absorber (W), \(\:{T}_{o}\) is outlet temperature (K), and \(\:{T}_{i}\) is the air inlet temperature (K).

Furthermore, the thermal efficiency of a SAH can be written as follows:

where \(\:I\) is the intensity of solar radiation (W/m2), and \(\:{A}_{c}\) is the collector surface area.

The convective heat transfer coefficient (h) can be enhanced by using a variety of both passive and active augmentation strategies. This parameter will be represented in a non-dimensional form as the Nusselt number:

The value of the Nusselt number can be determined from the following correlation:

and the Reynolds number stated as

where

If the turbulent flow through a conduit is fully formed and the Reynolds number (Re) is defined as less than 50,000, which gives the following equation for \(\:\varDelta\:P\)

where

Equation 27 can be used to determine the friction factor for the SAH.

Uncertainty analysis is used to confirm the validity and dependability of the experimental values (Holman38. The experimental and anticipated value uncertainties are displayed in Table 4. The analysis findings demonstrate that the expected values fall within the permitted range.

Uncertainty in the mass flow rate is evaluated using

The above equation decreases as follows when one considers that uncertainty only arises in measurements of temperature and pressure differences:

When evaluating the thermal performance, uncertainty arises and is computed using

Results and discussion

From 9:00 a.m. to 5:00 p.m., various parameters are measured while conducting the test. The experimentation occurred over three days: 4/3/2020, 5/3/2020 and 6/3/2020 on sunny days. Experiments took place on March 4th using a flow rate of 0.0230 kg/s, on March 5th 2020, using 0.0307 kg/s, and on March 6th 2020, using 0.0384 kg/s. Solar radiation is important in assessing the thermal behaviour of the SAH. The solar intensity is recorded using the solar meter for the month of March 2020. Figure 9 shows the average solar radiation for three successive days. It is observed that almost equal solar radiation is observed for all three experimentation days. The value starts to rise from the start of the measurement and reaches its maximum in the afternoon at 1.30 p.m. and again starts to fall toward the evening. The solar radiation values vary from a minimum of 293 W/m2 to a maximum of 846 W/m2 during the measuring days. The solar intensity level at the selected experimental site is ideal for conducting solar thermal system experiments, particularly for the solar air heater.

Figures 10, 11 and 12 show the measured input, output, glass cover, and absorber plate temperatures at flow rates of 0.0230, 0.0307, and 0.0384 kg/s, respectively. The temperatures obtained for the SAH exhibit a similar pattern as solar radiation intensity. Temperatures are recorded using a thermocouple (k type) and data logger. Findings show that the SAH temperatures have a comparable solar radiation propensity, which rises with time until around 1 p.m. to 2 p.m., and falls steadily the remaining time. The supreme temperature is observed at the absorber plate in both conventional (FSAH) and V baffle (VSAH) SAHs. The plate transfers heat to the air, raising the outlet temperature of the air. Due to the high transmissivity of the transparent glass and its proximity to the incident solar radiation, the glass temperature is consistently higher than that of the surrounding air. This occurs because the glass absorbs and transmits solar radiation efficiently, while the surrounding air, which is in contact with the plate, heats up more gradually. Additionally, the thermal conductivity of the glass allows it to retain and conduct heat, further elevating its temperature compared to the air.

The temperatures of the glass and collector are higher for the FSAH than for the VSAH, as shown in Figs. 10, 11 and 12. They further show that the air between the baffles in the VSAH (V-shaped Solar Air Heater) has a longer holding time, which allows for more effective heat transfer between the absorber plate and the air. As the air spends more time in contact with the heated surfaces, it absorbs more thermal energy, resulting in a higher output temperature compared to the FSAH (Flat Solar Air Heater), where the airflow is more streamlined and has less interaction with the heated surfaces. Due to the high air exposure time to the absorber layer, the transfer of heat to the air is greater in the case of VSAH than in the FSAH. The average temperature of the SAH output rises with air flow rate. For 0.0230, 0.0307, and 0.0384 kg/s, the highest outlet temperatures of the FSAH are 48.0 °C, 53.0 °C, and 57.0 °C, whereas the highest output temperatures of the VSAH are 55 °C, 59 °C, and 63 °C. The average output temperature of FSAH is 45.0, 47.0 and 49.00 C, whereas the average output temperature of VSAH is 47.0 °C, 51.0 °C and 52.0 °C. For flow rates of 0.0230, 0.0307, and 0.0384 kg/s, an air heater with V baffles has a 2.0 °C, 4.0 °C, and 3.0 °C higher average exit temperature range than the FSAH. It shows that increasing the air flow rate within the SAH enhances the air exit temperature and raises the coefficient of heat transfer among the absorber and the air. In this study, it was observed that increasing the airflow rate led to a rise in outlet air temperature. This behaviour is attributed to enhanced convective heat transfer between the absorber surface and the flowing air, as well as reduced thermal losses due to lower temperature gradients with the surroundings. Additionally, higher flow rates help the system reach steady-state conditions more quickly, allowing for more efficient heat extraction.

An important parameter for calculating the SAH thermal efficiency is useful power. Figure 13 depicts the useful power of both the FSAH and VSAH systems. Like solar radiation, useful power increases with time, peaks around 1.30 to 2.00 p.m., and then falls until the day’s end. This is because useful power mainly depends on the output working fluid temperature (air), as shown in Eq. 20. It shows that useful power also rises as the heat transfer coefficient in the SAH improves with increased air flow rate. During the study period, the useful power ranged for the FSAH from 37.90 W to 753.31 W, and for the VSAH from 57.78 W to 890.70 W. The maximum useful power values of 292.63 W, 545.48 W, and 753.31 W for the conventional air heater are observed at 14.00 in the afternoon for flow rates of 0.0230, 0.0307, and 0.0384 kg/s, respectively. For the same investigated parameters, the useful power values for the VSAH are 386.25 W, 733.38 W, and 890.70 W. SAH with roughness is likely to gain more power than a flat plate SAH. The increase in useful power for the VSAH is owing to the air temperature. It is also demonstrated that the higher flow rate of 0.0384 kg/s of air leads to the highest useful power values in the experiment contrasted to the other two flow rates. On the studied days, the average useful power values for the FSAH are 190.67 W, 317.70 W, and 457.29 W, respectively. For the same days, the average useful power values for the VSAH are 244.35 W, 448.17 W, and 585.37 W, respectively. It is found that the VSAH attains 26%, 29% and 28% improvements in useful power than the conventional system while using the same mass flow rate. Note that the uncertainty in useful power values is ± 1.086 W.

Solar air heater performance is strongly affected by top surface heat loss. The top losses for the FSAH and VSAH are shown in Fig. 14. The curves follow the similar trend as those for radiation and the useful power of the system: top loss values start increasing with time and attain their top range in the afternoon at 2 p.m. and then fall to the day’s end. The highest heat loss values of the conventional air heater are higher than those of the baffled VSAH. The conventional heater has a lower temperature range for various flow rates, resulting in higher heat losses on the top than the baffle air heater. Due to decreased outlet temperature, a flat plate SAH wastes more heat than a VSAH. The top loss ranges from 160 W to 764 W for the FSAH and 138 W to 612 W for the VSAH. For 0.0230, 0.0307, and 0.0384 kg/s, average heat losses in the top surface for the FSAH on examined days are 405 W, 498 W, and 500 W, respectively. The average top surface heat losses for the VSAH are 363 W, 424 W, and 434 W, respectively. This result demonstrates that, for the investigated flow rates, the VSAH has a 10%, 19%, and 24% lower average heat loss than the FSAH, for the respective examined days. As a result, the system efficiency is increased for the proposed design relative to the conventional one.

Thermal efficiency (Eq. 21) is an important parameter for determining the SAH system’s performance and for improving it. The fluctuation in efficiency over time for several flow rates is shown in Fig. 15. The system’s efficiency rises marginally as the day progresses. Because of the rise in solar radiation, efficiency begins to rise from morning to afternoon. The system recovers the solar energy already stored in the collector plate and other SAH bodies due to the Moore effect as the sun sets in the afternoon. As a result, the collector aids in improving the SAH’s efficiency.

Due to the increased retention period of air within the system, adding baffles to the absorber region enhances the output temperature and contact between the air and the plate. Consequently, the FSAH has a lower efficiency for various flow rates than the VSAH. The minimum efficiency in a day for the analyzed parameters is 8%, and the maximum efficiency is 58%, for the FSAH. The minimum efficiency in a day for the VSAH is 12%, with a maximum efficiency of 78%. For flow rates of 0.0230, 0.0307, and 0.0384 kg/s, respectively, the daily maximum efficiency values for the FSAH are 29%, 40%, and 55%, and for the VSAH are 34%, 62%, and 78%. The VSAH efficiency for the investigated day is much higher than the FSAH for the same parameters. For the tested day, the FSAH average thermal efficiencies are 19%, 31%, and 47%. In comparison, the VSAH has average efficiency values of 24%, 44%, and 61% for 0.0230, 0.0307, and 0.0384 kg/s, respectively. The VSAH has a 5%, 13%, and 14% greater average thermal efficiency for the flow rates studied. The results indicate that increasing the air flow elevates the coefficient of heat transfer, hence improving thermal efficiency. The uncertainty value for thermal efficiency is ± 0.003%.

A comparison of the maximum efficiency of previous shape SAH models with the proposed VSAH is shown in Table 5. It is clearly seen that the proposed model achieves a significantly improved SAH efficiency with increasing air flow rate.

Pressure drop due to air flow resistance is an significant factor in the evaluation of SAH output. The system’s net useful energy decreases as the pressure drop rises. Figure 16 shows the pressure drop of the investigated systems for several flow rates. Pressure drop is more significant for the VSAH than the FSAH, according to the results. The pressure drop in FSAH is lower than in a VSAH design because it has a smoother flow path with minimal obstructions, leading to less airflow resistance and lower friction losses. It is also seen that increasing the air flow rate reduces the system pressure drop. As the flow rate rises from 0.0230 to 0.0307 and 0.0384 kg/s, the pressure drops declines. Although pressure drop typically increases with airflow rate, in this setup, a higher drop was observed at lower flow rates. This behaviour may be due to flow instability or transitional flow effects that increase resistance at low speeds. At higher flow rates, improved flow uniformity and stable conditions likely reduced localized resistance, resulting in a lower measured pressure drop. At 0.0230 kg/s, the pressure drop for VSAH is around 41 Pa, significantly higher than for the FSAH, which has a lower pressure drop at this flow rate. At higher mass flow rates, 0.0307 kg/s and 0.0384 kg/s, the VSAH still shows higher pressure drops than the FSAH but demonstrates a slight decrease in pressure drop at 0.0384 kg/s compared to 0.0307 kg/s. The pressure drop for the VSAH is 32 and 19 Pa while using a mass flow rate of 0.0307 and 0.0384 kg/s. Figure 16 shows that the air flow has a minimal effect on the system’s pressure drop and consequently has a low influence on the useful power output because the SAH’s useful energy range is much higher than the pressure drop.

The environmental and economic characteristics of the SAHs are aspects of system effectiveness for various applications. An energy metrix analysis determines the system’s economic and ecological behaviour. It is mostly determined by the embodied energy (\(\:{E}_{in}\)) of each SAH component. The total embodied energy values obtained for the individual components are 1123.12 kWh for the FSAH and 1263.57 kWh for the VSAH. These characteristics, including energy production factor, life cycle conversion efficiency, energy payback period, lifetime CO2, NO, SO2 emissions, net lifetime mitigation, and carbon credit earned using SAH, are all evaluated using the embodied energy value. The obtained values are plotted in Table 6, based on the results of the energy matrices study for the FSAH and VSAH. With numerous upgraded parameters, the payback period of the SAH system is only 2.09 years, according to the economic analysis. As a result, this system can be used in a variety of sectors for enhanced performance.

The outlet air temperature was obtained from both experimental measurements and CFD simulations for validation purposes. The experimental results were recorded under real-time climatic conditions, while the CFD simulations were performed using the given boundary conditions to predict thermal behaviour. Figure 17 shows the discrepancy between CFD and experimental testing. The CFD’s outlet temperature for the day (Model III ribs) is nearly equivalent to the same input parameter’s experimental values. The CFD and experimental study’s average outlet temperature values are 53.4 °C and 51.4 °C, respectively. It is clearly observed that only 3.8% of the deviation occurs between the CFD and the experimental study; this range is reasonable for the SAH.

Conclusions

SAH with V shape and square and rectangular perforated baffles for various flow rates is investigated experimentally and its performance is contrasted with that of a traditional SAH. Energy gain, top losses, thermal efficiency, and friction factor all play a role. Key findings of the analysis, and conclusions drawn from them, follow:

-

For the VSAH, relative to the FSAH, the high flow rate value of 0.0384 kg/s leads to the greatest heat transfer.

-

Increasing the inlet flow rates enhances the SAH thermal performance. The greatest improvements are seen in outlet temperature, useful power, top losses, and thermal efficiency.

-

The VSAH exhibits a useful power gain of 26%, 29% and 28% over a flat surface SAH for flow rates of 0.0230, 0.0307, and 0.0384 kg/s, respectively. The VSAH also has lower corresponding average top losses of 10.35%, 18.79%, and 24.42%, relative to the FSAH.

-

The thermal efficiency is higher for the VSAH than the FSAH for all the parameters investigated. The VSAH attains the superior value of 61% for the higher air flow rate of 0.0384 kg/s.

-

For 0.0230, 0.0307, and 0.0384 kg/s, the VSAH exhibits average efficiency values of 24%, 44%, and 61%, respectively. The tested flow rate shows that the average efficiency of the VSAH is higher by 5%, 13%, and 14% compared to the FSAH.

Future investigations are merited for the proposed setup by employing various nano-coatings that enhance the absorptivity of the collector plate. In addition, integrating different thermal energy storage systems can increase operating time and overall system efficiency. Further studies may also consider transient operating conditions and alternative baffle geometries, as well as the application of multi-objective optimization techniques to balance thermal performance and pressure loss for practical and scalable solar air heating solutions.

Data availability

Data is provided within the manuscript file.

Abbreviations

- As :

-

Surface area (m2)

- Cp :

-

Specific heat (J/kgK)

- Ein :

-

Embodied energy of SAH (kWh)

- Eout :

-

Energy output for annual period (kWh/yr)

- EPF:

-

Energy production factor

- EPT:

-

Time to recover energy

- Esol :

-

Annual radiation (kWh)

- FSAH:

-

Flat Plate Solar Air Heater

- F´ :

-

Factor of absorber efficiency

- FR :

-

Factor of absorber heat removal

- g:

-

Emissivity of glass

- hr :

-

Coefficient of heat transfer through radiation on top (W/m2K)

- hw :

-

Heat transfer coefficient of wind (W/m2K)

- I:

-

Radiation (W/m2)

- LCCE:

-

Life cycle conversion efficiency

- m:

-

Air mass flow rate (kg/s)

- Qu :

-

Energy gain rate from plate (W)

- Ta :

-

Atmosphere temperature (K)

- Tg :

-

Average glass temperature (K)

- Ti :

-

Air input temperature (K)

- TL :

-

Lifetime of SAH

- To :

-

Air outlet temperature (K)

- Tsky :

-

Effective temperature of the sky (K)

- UL :

-

Coefficient of overall heat loss (W/m2/K)

- VSAH:

-

V baffle solar air heater

- Vw :

-

Wind velocity (m/s)

- (τα)e :

-

Effective absorptance and transmittance of collector

References

Matheswaran, M. M. et al. C. A case study on thermo-hydraulic performance of jet plate solar air heater using response surface methodology. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 34, 1019834. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.csite.2022.101983 (2022).

Subramaniam, B. S. K., Leong, W. Y. & Athikesavan, M. M. ESG in innovative and experimental approach for small-scale renewable energy generations. In ESG innovation for sustainable manufacturing technology: applications, designs and standards. Institution Eng. Technol. 257–304. https://doi.org/10.1049/PBME027E_ch17 (2024).

Singh, S., Singh, A. & Chander, S. Thermal performance of a fully developed serpentine wavy channel solar air heater. J. Energy Storage ; 25:100896. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.est.2019.100896. (2019).

Abo-Elfadl, S., Hassan, H. & El-Dosoky, M. F. Study of the performance of double pass solar air heater of a new designed absorber: an experimental work. Sol Energy ; 198:479–489. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.solener.2020.01.091. (2020).

Hegazy, M. M., El-Sebaii, A. & Ramadan, M. R. Comparative study of three different designs of a hybrid PV/T double-pass finned plate solar air heater. Environ. Sci. Pollut Res. ; 27:32270–32282. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-019-07487-8. (2020).

Madhu, B., Kabeel, A. E., Sathyamurthy, R. & Sharshir, S. W. Investigation on heat transfer enhancement of conventional and staggered fin solar air heater coated with CNT-black paint — an experimental approach. Environ. Sci. Pollut Res. ; 27: 32251–32269. (2020).

Varshney, L. & Saini, J. S. Heat transfer and friction factor correlations for rectangular solar air heater duct packed with wire mesh screen matrices. Sol Energy ; 62:255–262. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0038-092X(98)00017-6. (1998).

Kumar, K., Prajapati, D. R. & Samir, S. Heat transfer and friction factor correlations development for solar air heater duct artificially roughened with ‘S’ shape ribs. Exp. Therm. Fluid Sci. ; 82: 249–261. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.expthermflusci.2016.11.012. (2016).

Singh, I. & Singh, S. CFD analysis of solar air heater duct having square wave profiled transverse ribs as roughness elements. Sol Energy ; 162:442–453. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.solener.2018.01.019. (2018).

Ravi, R. K. & Saini, R. P. Nusselt number and friction factor correlations for forced convective type counter flow solar air heater having discrete multi V shaped and staggered rib roughness on both sides of the absorber plate. Appl. Therm. Eng. ; 129:735–746. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2017.10.080. (2018).

Singh Patel, S. & Lanjewar, A. Experimental and numerical investigation of solar air heater with novel V-rib geometry. J. Energy Storage ; 21:750–764. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.est.2019.01.016. (2019).

Kumar, A. & Layek, A. Nusselt number and friction factor correlation of solar air heater having twisted-rib roughness on absorber plate. Renew. Energy ; 130:687–699. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.renene.2018.06.076. (2019).

Jain, P. K. & Lanjewar, A. Overview of V-RIB geometries in solar air heater and performance evaluation of a new V-RIB geometry. Renew. Energy ; 133:77–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.renene.2018.10.001. (2019).

Srivastava, A., Chhaparwal, G. K. & Sharma, R. K. Numerical and experimental investigation of different rib roughness in a solar air heater. Therm. Sci. Eng. Prog ; 19:100576. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tsep.2020.100576. (2020).

Kumar, A. & Layek, A. Nusselt number and friction factor correlation of solar air heater having winglet type vortex generator over absorber plate. Sol Energy ; 205:334–348. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.solener.2020.05.047. (2020).

Luan, N. T. & Phu, N. M. Thermohydraulic correlations and exergy analysis of a solar air heater duct with inclined baffles. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. ; 21:100672. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.csite.2020.100672. (2020).

Kumar, A. & Layek, A. Nusselt number and friction characteristics of a solar air heater that has a winglet type vortex generator in the absorber surface. Exp. Therm. Fluid Sci. ; 110204. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.expthermflusci.2020.110204 (2020).

Singh, I. & Singh, S. A review of artificial roughness geometries employed in solar air heaters. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. ; 92:405–425. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2018.04.108 (2018).

Singh, S. Thermal performance analysis of semicircular and triangular cross-sectioned duct solar air heaters under external recycle. J. Energy Storage ; 20:316–336. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.est.2018.10.003 (2018).

Saravanakumar, P. T., Somasundaram, D. & Matheswaran, M. M. Thermal and thermo-hydraulic analysis of Arc shaped rib roughened solar air heater integrated with fins and baffles. Sol Energy ; 180:360–371. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.solener.2019.01.036 (2019).

Bensaci, C. E., Moummi, A. & de la Sanchez, F. J. Numerical and experimental study of the heat transfer and hydraulic performance of solar air heaters with different baffle positions. Renew. Energy ; 155:1231–1244. (2020).

Kumar, A. & Layek, A. Energetic and exergetic performance evaluation of solar air heater with twisted rib roughness on absorber plate. J. Clean. Prod. ; 232:617–628. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.05.363. (2019).

Kumar, A., Akshayveer, Singh, A. P. & Singh, O. P. Efficient designs of double-pass curved solar air heaters. Renew. Energy ; 160:1105–1118. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.renene.2020.06.115. (2020).

Nidhul, K., Kumar, S., Yadav, A. K. & Anish, S. Enhanced thermo-hydraulic performance in a V-ribbed triangular duct solar air heater: CFD and exergy analysis. Energy ; 200:117448. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2020.117448. (2020).

Chhaparwal, G. K., Srivastava, A. & Dayal, R. Artificial repeated-rib roughness in a solar air heater – A review. Sol Energy ; 194:329–359. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.solener.2019.10.011. (2019).

Rajendran, V., Ramasubbu, H., Alagar, K. & Ramalingam, V. K. Performance analysis of domestic solar air heating system using V-shaped baffles – an experimental study. J. Process. Mech. Eng. ; 235: 1705–1717. (2021).

Rajendran, V. et al. Enhancing the performance of a solar air heater by employing the broken V–shaped ribs. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. ; 30: 77807–77818. (2023).

Singh, V. P. et al. Salah kamel. Heat transfer and friction factor correlations development for double pass solar air heater artificially roughened with perforated multi-V ribs. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. ; 39:102461. (2022).

Kumar, R. et al. Eldin. Experimental assessment and modeling of solar air heater with V shape roughness on absorber plate. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. ; 43: 102784. (2023).

Prashant Raturi, H., Deolal, S. & Kimothi Numerical analysis of the return flow solar air heater (RF-SAH) with assimilation of V-type artificial roughness. Energy Built Environ. ; 5:184–193. (2024).

Yadav, A. S. & Bhagoria, J. L. Heat transfer and fluid flow analysis of solar air heater: A review of CFD approach. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. ; 23:60–79. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2013.02.035. (2013).

Naveenkumar, R. et al. Thermal performance analysis of a parabolic trough collector based solar water heater using revolving absorber tube. Results Eng., p. 104270, (2025).

Chakraborty, A., Khan, U., Elrashidi, A., Alsubaie, B. M. T. & Abdalla, M. Entropy and back-propagation analysis of Ag – MgO/water hybrid nanofluid flow over a radially stretching disk: response optimization and sensitivity analysis. Alexandria Eng. J. 117, 116–135 (2025).

Vijayakumar, R., Kumar, R. V. & Madhu, P. Investigation on energy, economic, and environmental aspects of double-pass solar air heater. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 31, 39406–39420. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-024-33786-w (2024).

Vijayakumar Rajendran, K. & Singaraj Jayavenkatesh rajarathinam. Environmental, economic, and performance assessment of solar air heater with inclined and winglet baffle. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 30, 14337–14352. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-022-23213-3 (2022).

Vijayakumar, R., Harichandran, R., Jaya Venkatesh, R. & Ramanan, P. Experimental study on the thermal performance of a solar air heater integrated with multigeometry arrangements over the absorber plate. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. ; 29:38331–38345. (2022).

Lakshmaiya, N. et al. Optimization of thermal efficiency in double pass solar air heating systems with emphasis on collector design parameters and operating conditions. Results Eng. 26, 104948 (2025).

Holman, J. Experimental Methods for Engineers (McGraw-Hill, 1966).

Abdullah, A. S., Abou Al-sood, M. M. & Omara, Z. M. Performance evaluation of a new counter flow double pass solar air heater with turbulators. Sol Energy ; 173:398–406. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.solener.2018.07.073 (2018).

Jia, B., Liu, F. & Wang, D. Experimental study on the performance of spiral solar air heater. Sol Energy ; 182:16–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.solener.2019.02.033. (2019).

Abdullah, A. S., El-Samadony, Y. A. F. & Omara, Z. M. Performance evaluation of plastic solar air heater with different cross sectional configuration. Appl. Therm. Eng. ; 121:218–223. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2017.04.067. (2017).

Hassan, H. & Abo-Elfadl, S. Experimental study on the performance of double pass and two Inlet ports solar air heater (SAH) at different configurations of the absorber plate. Renew. Energy ; 116:728–740. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.renene.2017.09.047 (2018).

Nowzari, R., Aldabbagh, L. B. Y. & Egelioglu, F. Single and double pass solar air heaters with partially perforated cover and packed mesh. Energy ; 73:694–702. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2014.06.069. (2014).

Kabeel, A. E., Hamed, M. H., Omara, Z. M. & Kandeal, A. W. Influence of fin height on the performance of a glazed and bladed entrance single-pass solar air heater. Sol Energy ; 162:410–419. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.solener.2018.01.037 (2018).

Murali, G., Sundari, A. T. M. & Raviteja, S. Experimental study of thermal performance of solar aluminium cane air heater with and without fins. Mater. Today Proc. ; 21:223–230. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matpr.2019.04.224 (2020).

Alzahrani, H. A. H. et al. Enhancing solar air heater efficiency with 3D cylinder shaped roughness elements. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. ; 51:103617. (2023).

Acknowledgements

The authors extend their appreciation to the Researchers Supporting Project number (RSPD2025R999), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Vijayakumar Rajendran: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Writing – original draft. Alagar Karthick: Software, Formal analysis, Validation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. Ganesh Bhausaheb Shinde: Resources, Data curation, Project administration. Kamal Sharma: Supervision, Methodology, Writing – review & editing.Marc A. Rosen: Writing – review & editing, Funding acquisition, Supervision. Md. Irfanul Haque Siddiqui: Investigation, Data curation, Visualization. Choon Kit Chan: Software, Validation, Writing – review & editing. Ghanshyam P. Tejani: Resources, Formal analysis, Project administration.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Rajendran, V., Karthick, A., Shinde, G.B. et al. Performance enhancement of solar air heater using V baffles. Sci Rep 15, 34867 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-13333-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-13333-4