Abstract

This study deals with the problem of consumption of construction waste and shortage of traditional construction materials, offering a technical and environmental basis for the recycling and utilization of construction and demolition waste (CDW). Using waste concrete and waste bricks as recycled aggregates for pavement base materials, and cement, lime and fly ash as stabilizers, this study systematically explores the feasibility of stabilizing recycled aggregate-based materials for road use. The basic physical properties and macro-mechanical properties are analyzed, and the effects of stabilizer dosage (ESR), recycled aggregate dosage (RASR), and brick-concrete ratio (BCR) on the roadability of stabilized recycled aggregate materials are investigated. Revealing the significance and critical effects of multi-factors of strength development. Life cycle assessment (LCA) method is employed to measure the carbon emissions of different materials used as road pavement sub-base and compare them with those of natural aggregates. The results show that stabilized construction waste recycled aggregate is suitable for road subgrade. ESR, RASR and BCR have a significant effect on it with the order of BCR > RASR > ESR. The optimum ratio exists at 30% ~ 45% recycled aggregate blending and 1:2 of BCR. The carbon emission of cement stabilized class can be reduced from 60,789.66 to 48,117.03 kgCO2eq by using recycled construction waste aggregate instead of natural aggregate during construction period based on the base unit (a flow section length of 500 m as the basic unit), which is 19.2% reduction in carbon emission. For the lime fly ash stabilized category, the carbon emission is reduced from 53,246.65 to 41,734.03 kgCO2eq, which is 21.6% reduction in carbon emission. Recycled aggregates alone can achieve carbon emission reductions of 82.27%, 81.23%, and 78.02%, demonstrating a substantial environmental benefit in carbon reduction.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Urbanization and urban renewal projects around the world are giving rise to immense quantities of CDW and carbon emissions. The challenge of effectively handling this solid waste has emerged as one of the most pressing ecological dilemmas and urban safety hazards1. The annual generation of CDW in China is currently up to 1.8 billion tons. And the utilization rate of resource utilization in China is less than 5%, which is far lower than that of Korea, Japan, Germany and other countries2. A significant portion of CDW is still handled by direct outward transportation to landfills, resulting in a serious waste of resources. Amid the grave context of global warming, low-carbon economy has become an important trend of sustainable development in today’s society. A variety of accession to the “Paris Agreement” have formulated a detailed “carbon reduction” program to limit the global temperature rise to within 2 ℃3. And China also strictly abides by the “Paris Agreement”, 2020 proposed to strive to achieve “carbon peak” before 2030, to achieve “carbon neutrality” before 2060.

A consensus among experts and scholars that CDW is a “misplaced resource”4,5. By replacing traditional materials with recycled or discarded materials, the construction industry can capitalize on the circular economy by reducing the need for new resources and reducing the generation of waste. The use of recycled or discarded materials in buildings is an effective way to create a more sustainable and circular economy6. Therefore, if it is classified, recycled and put in the right place, it will eventually build a “waste-free society”. This will bring significant environmental, social and economic benefits. Therefore, under the current double pressure of resources and the environment, the disposal of CDW has become a hot spot. Road infrastructure is a critical component of the transportation sector, requiring substantial quantities of construction materials for both its creation and upkeep. The carbon emission in the field of transportation in China accounts for about 10% of the total national carbon emission, which is the key area of social carbon control7. In recent years, driven by environmental conservation mandates, various authorities have imposed stringent restrictions on the extraction of materials for infrastructure development. Within this context, investigating the recycling of CDW for application in road engineering represents an effective strategy to address the issue of CDW disposal and the scarcity of traditional construction materials.

In recent years, domestic scholars have carried out a large number of studies on the application of recycled CDW in road engineering8. With recycled aggregates, the shortage of conventional fillers in roadbeds can be alleviated, and the environmental pollution caused by littering of CDW can also be solved9,10,11,12. Several researchers have conducted systematic analysis and research on the road performance, engineering application, environmental protection and economy of CDW used for roadbed filling. They have methodically reviewed, summarized, and analyzed the fundamental properties, strength and deformation characteristics, as well as the water retention qualities of the recycled roadbed filler derived from CDW, forming the development of corresponding technical guidelines. The application of these guidelines in the base sections of various regions across China has not only gained widespread adoption but has also yielded substantial economic and social advantages7,13,14. They have been popularized and applied in many areas in China, such as the North Ring Road of Xi’an-Xianyang Expressway, Beijing Capital Ring Road (Daxing-Tongzhou section), and Yueruo section of Shanghai-Chongming Expressway, etc., and have produced remarkable economic and social benefits. Additionally, other researchers are involved in the manual sorting or crushing processing of CDW, where they prepare recycled aggregates in specific proportions and blend them with natural limestone aggregates15,16. Under laboratory conditions, researchers are investigating the use of cement-stabilized gravel for pavement bases layers or sub-bases that incorporate varying quantities of recycled aggregates. They are examining the mix’s strength, stiffness, resistance to erosion, frost resistance, and shrinkage characteristics, leveraging the skeleton effect to understand the performance of these materials. Existing research tends to use CDW for the backfill of road base after rough processing, and focuses on the research and application of CDW recycled aggregate blended with natural high-quality aggregates, such as rock, etc.17. The composition of CDW is inherently complex, with common aggregates including bricks, concrete, and soil. Research on the design and application of recycled aggregates with multiple components is limited, and there is a gap in the study of clay-blended mixtures and the mechanical properties of these recycled mixtures. While the focus remains on achieving desirable mechanical properties in recycled materials, the range of stabilizers used is predominantly confined to cement. The research and application of alternative stabilizers such as lime and fly ash are relatively underexplored. This narrow scope of investigation fails to provide a comprehensive analysis of the influence of the primary components of CDW, thereby constraining the potential applications of recycled aggregates derived from construction debris.

In addition to technical indicators, carbon emission accounting analysis and the corresponding environmental and life cycle evaluation have also become the key indicators of CDW recycled aggregates. In addition to technical indicators, in recent years, foreign research has emphasized that the management of CDW needs to shift from “end-of-life disposal” to “whole-life cycle optimization”, and carbon emission accounting and analysis, as well as the corresponding environmental and whole-life cycle environmental evaluation, have become the key indicators for the recycled aggregates of CDW18,19. Tamanna et al.20 constructed a “carbon-performance dual-threshold model” to provide quantitative criteria for the engineering application of recycled materials, and Muhammed Ulucan et al.21,22 investigated the engineering characteristics of construction and demolition waste from the comprehensive approaches of mechanics, environment and economy. Currently, carbon emission accounting for transportation infrastructure, both domestically and internationally, remains in its preliminary stages23,24. Meanwhile, the carbon emission accounting analysis for the resource utilization of CDW is concentrated in the comparative analysis of direct landfill and resource treatment25. Moreover, the carbon emission accounting system used for the construction period of road infrastructure has not been perfected, which is not conducive to evaluating the carbon reduction benefits of recycled aggregates from CDW. Therefore, it is necessary to carry out the research on the influence law of CDW recycled mix combination design on pavement sub-base; through the comparative analysis of the treatment effect of different stabilizers on CDW, to explore the combined performance of road pavement subgrade with different types of stabilizers in terms of workability, carbon reduction, etc.

In this study, 96 groups of mix ratios were designed through indoor tests, using cement, lime and fly ash as stabilizers, controlling variables such as stabilizer dosage (4–16%), aggregate dosage (≥ 15%), and brick concrete ratio (BCR = 0.5–2), and systematically analyzing the influence of synergistic effect of multi-component recycled aggregates on the mechanical properties of pavement subgrade, establishing a gradient influence model based on response surface methodology to elucidate the dynamic threshold law for the performance response of multi-component recycled aggregates. Compared with the existing research (such as single cement stabilization technology or static grading optimization), through the optimization of component suitability and quantification of interaction, compare the design of low-carbon stabilization systems such as lime-fly ash, to reveal the key component interaction mechanism and low-carbon performance regulation path. Based on the full life cycle assessment (LCA), a full life cycle model covering the energy consumption of raw material production, transportation and construction is constructed to quantitatively compare the difference in carbon emission intensity per unit volume between recycled and natural aggregates in road sub-base, which provides a multi-stage linkage and quantitative analytical framework for the low-carbon evaluation of recycled materials in the infrastructure field. This study aims to promote the transformation of recycled materials from “low-value backfill” to “high-value road use” through the synergistic optimization of “performance-carbon emission”, so as to provide a quantitative analysis framework for the construction of green infrastructure under the goal of “dual-carbon”.

Materials and methods

Materials

In this research, soil samples were procured from a construction project in Tianjin. To prepare the samples, the larger soil particles were initially processed through pre-treatment, crushing, and dispersion using a wooden mallet. Subsequently, a sieving test was conducted to determine the mass percentage of particles that are finer than a specified particle size. The soil samples with a particle size of less than 0.075 mm were subjected to further analysis utilizing the densitometer method. This process allowed for the calculation of the content of soil particles below 0.002 mm, as detailed in Table 1. The liquid limit, plastic limit, and plasticity index of the test soil samples were determined and are presented in Table 2. The cement used is 42.5 ordinary Portland cement, manufactured by Tangshan Cement Plant, and its technical specifications are outlined in Table 3. The slaked lime (lime) is supplied by the Tianjin Local Lime Factory and is utilized in its slaked form, with the content of effective oxides exceeding 55%, as indicated in Table 4. Fly ash is sourced from the Tianjin coal-fired power plant, and its technical properties are detailed in Table 5. All materials and testing procedures adhere to the current Chinese specifications (JTJ 034) and (JTG 3430-2020) respectively.

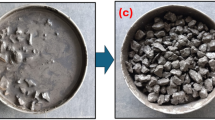

The CDW for this study was procured from a CDW treatment plant in Tianjin. Following a process of manual sorting, pre-crushing and crusher crushing, recycled aggregate from CDW (RACW) was obtained, as depicted in Fig. 1.

It is worth noting that the CDW may have to be crushed twice. After primary crushing, if there are still aggregates with large particle size, they need to be filled into the crusher again for secondary crushing. Additionally, preliminary experiments revealed that the distribution of coarse and fine particles in the aggregates after primary crushing was uneven, with an excess of coarse particles. Conversely, after the secondary crushing stage, the particle size of the CDW aggregate exhibits greater uniformity. Using a 5 mm standard sieve, aggregate particles smaller than 5 mm were removed. The test selected aggregate particles with a particle size range of 5–37.5 mm as recycled aggregate from CDW (RACW). Then, the “spread and take” method was using to homogenize the aggregate, i.e., all the aggregate was spread out (with a thickness of about 5 cm), and samples were taken vertically across the entire cross-section to avoid interlayer segregation.

In this study, mix ratios are designed based on three aspects: brick to concrete block ratio (Brick-Concrete Ratio, BCR), recycled aggregate to soil ratio (Recycled Aggregate-Soil Ratio, RASR) and external stabilizer ratio (ESR). In order to study the reasonable gradation of construction waste in the application of sub-base layer of pavement for secondary and following highways with low and medium traffic, combined with the Technical Specification for the Utilization of CDW in Highway Engineering (JTGT 2321-2021) and the related literature26,27, three BCR values (2:1,1:1,1:2) and four recycled aggregate mixes (15%, 30%, 45%, and 60%) are selected for the study of rational grading of CDW for sub-base application. Furthermore, according to the Technical Rules for Highway Pavement Subgrade Construction (JTG/T F20-2015), external admixture cement dosages of 4% and 6%, lime dosages of 8%, 10% and 12% and lime-fly ash dosage ratios of 5:10, 6:12 and 8:16 are proposed. The quality of the external admixture is calculated using external admixture calculation method. The composition of the test samples is shown in Table 6.

Test methods

Standard compaction test

The standard compaction test is carried out based on the current Chinese specification (JTG E51). Given that the maximum grain size of the specimen is 37.5 mm, the heavy-duty standard compaction method is used, and the sample is compacted according to the 3-layers compaction method. During this process, each layer was subjected to 98 hammer blows, resulting in an average unit compaction energy of 2677 kJ/cm3. The volume of the test cylinder used was 2177 cm3.

As illustrated in Fig. 2, the specimen preparation process is detailed. A preliminary experiment revealed that the uniform distribution of moisture within the test material significantly influences the compaction outcomes. Consequently, water was uniformly sprayed onto soil that had been sieved to a particle size of 5 mm and then mixed with the CDW aggregate. Following thorough blending, the mixture was sealed and left to stand for 24 h to equalize moisture content and to mitigate discrepancies in the test results. Additionally, due to the abundance of angular edges and rough surfaces characteristic of crushed CDW, there is a heightened risk of abrasion to filter paper and soil loss, which can compromise the accuracy of the test results. To address this, a finer mixture was employed for compacting the initial layer. After compaction, the top surface of the specimen was meticulously leveled to guarantee the specimen’s structural integrity.

Unconfined compressive strength (UCS) test

The test employs the static compaction method to prepare specimens for each group, with each cylindrical specimen measuring Φ150 mm × 150 mm and a total of 6 specimens per group. After the specimens are made, they are all placed in a standard curing room for curing. The humidity in the curing room is maintained above 98%, and the room temperature is kept at 25 ± 2 °C. On the day before the specimens reach the predetermined curing age, they are removed and soaked in water for 24 h. Afterward, the specimens are taken out, and the water on their surfaces is wiped dry before conducting the compressive strength test. During the test, the deformation of the specimens is maintained at an increasing rate of 1 mm/min. During the test, the peak pressure (P) at specimen failure is recorded. Compressive strengths at ages of 7d, 28d, 90d, and 180d are tested respectively. The compressive strength RG is calculated using the following Eq. (1):

where P is maximum pressure values at which the specimens fail, A is Section area of the specimen.

Splitting strength test

The preparation and curing method for the specimens in this test are the same as those used in the unconfined compressive strength test. Prior to the test, the specimens are soaked in water for 24 h for standard curing. Subsequently, the specimens are removed, and the water on their surfaces is gently wiped dry. The height and mass of the specimens are then measured. In this test, the deformation rate of the specimens is controlled to increase uniformly, at a rate of approximately 1 mm/min. The maximum pressure at which the specimens fail is recorded. The splitting tensile strength Rf is calculated using the following Eq. (2):

where Rf is splitting tensile strength, P is maximum pressure values at which the specimens fail, H is the height of the specimen after immersion.

Compressive resilient modulus test

This test adopts the top surface method to test the compressive resilience modulus of the specimen. The specimens have dimensions of Φ150 mm × 150 mm and their preparation and curing methods are the same as those used in the unconfined compressive strength test. Before testing, the specimens are submerged in water for a 24-h period to achieve standard curing conditions. Following the curing process, the specimens are carefully removed from the water, and any surface moisture is gently dried. The height and mass of each specimen are then recorded. The test begins with two preloading cycles, each applying half of the maximum load that will be used during the test. One minute after the preloading cycles are completed, the dial indicator is reset to zero. The pressure is applied in increments of one-fifth of the predetermined unit pressure. The dial indicator reading is recorded after each increment of pressure has been applied for 1 min, and the applied load is then removed to allow the specimen to recover its deformation. The dial indicator reading is recorded again 0.5 min after unloading. The resilient deformation L of the specimen is the difference between the two deformation readings mentioned above. The compressive resilience modulus E is calculated using the following Eq. (3):

where E is compressive resilient modulus, P is the unit pressure, H is the height of the specimen, L is the specimen rebound deformation.

Multifactor analysis of variance (ANOVA) method

Multifactorial analysis of variance (ANOVA) is employed to examine how independent factors significantly influence experimental outcomes and their potential interaction effects28. In this study, three control variables—BCR (1:1, 1:2, 2:1), ESR (4%, 6%), and RASR (15%, 30%, 45%, 60%)—are statistically evaluated to assess their significant impacts on the dependent variable (UCS values), including factor interactions. Data analysis is conducted using the three-way ANOVA module within OriginPro 2022 (Version 9.9.0.225, OriginLab Corporation). The statistical significance of each factor is determined through F-statistics and p-values (α = 0.05), with the ranking of influence magnitude based on F-values. These findings establish a methodological framework for optimizing recycled aggregate pavement performance through systematic adjustments of BCR, ESR, and RASR parameters.

Life cycle assessment methodology for carbon emissions

To scientifically and comprehensively quantify the carbon reduction benefits of utilizing CDW, we have developed a carbon accounting and mitigation model using the Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) method. This model is designed to measure and evaluate indicators of carbon emission reduction. The accuracy of carbon emission accounting relies on the principle of the full life cycle theory. It necessitates selecting an appropriate accounting method that aligns with the objectives of the evaluation and the channels through which data is collected. For the carbon accounting of transportation infrastructure projects, currently, there are three primary methods that have been adapted based on the whole life cycle theory to accommodate the various types and characteristics of projects both domestically and internationally: the emission factor method, the mass balance method, and the direct measurement method9. This study adopts the emission coefficient method, which is one of the most widely applicable and commonly used carbon accounting methods. The emission factor method involves calculating the total carbon emissions of a project over its lifecycle by multiplying the quantities of various construction materials and energy used during each phase by their respective carbon emission factors, and then summing these products to determine the comprehensive carbon emission level.

Result and discussion

Analysis of basic properties of recycled aggregates from CDW

The basic properties of recycled aggregates from CDW (RACW) mainly include its appearance morphology, particle composition, apparent density, water absorption rate, impurity content, crushing value, etc. Analyzing the basic properties of RACW lays the foundation for further research on its road performance.

Morphology and particle analysis

Appearance analysis evaluates the shape, size, and surface characteristics of aggregates, which have a significant impact on the stability of road structures. Using a digital single-lens reflex camera (Nikon D850, AF-S Micro NIKKOR 60 mm f/2.8G ED lens), photographs of aggregate samples are taken under natural light, with three researchers independently assess the apparent morphological characteristics. Furthermore, it aids in identifying factors that may reduce road lifespan. As shown in Fig. 3, when comparing recycled aggregates produced by a crusher with natural aggregates, the recycled aggregates exhibit poorer particle shapes and have more angular edges. Besides, its surface is line rough due to the cement mortar and some of the aggregates have a large number of microcracks.

For the particle size distribution of CDW recycled aggregates, we plotted the gradation curve based on the “Sieve Analysis Test for Coarse Aggregates and Aggregate Mixtures (T 0302-2005)” specified in the current Chinese standard “Test Methods for Aggregates for Highway Engineering (JTG E42-2005)”. It is shown in Fig. 4 that the coarse and fine particles of the CDW aggregate after primary crushing are not uniform, and the coarse aggregate is on the high side, while the particle size of the CDW aggregate after secondary crushing is more uniform.

To further analyze the particle composition of the recycled aggregates, the coefficient of uniformity (Cu) and coefficient of curvature (Cc) are calculated using Eqs. (4) and (5), respectively. The parameters and indicators are presented in Table 7. A higher value of these coefficients indicates a flatter gradation curve, a broader range of particle size distribution, greater unevenness, and thus easier compaction. When the values fall within the range of 1–3, it suggests continuous gradation. Based on comprehensive analysis, it is concluded that the gradation after secondary crushing is good, resulting in satisfactory compaction effectiveness. Furthermore, as depicted in Fig. 4, the maximum particle size of the recycled aggregates from CDW after secondary crushing does not exceed 37.5 mm. According to the requirements of the Chinese specification (JTJ 034-2000), these aggregates can be utilized in the subbase of highways at all levels.

where d10, d30 and d60 are the grading curves with 10%, 30% and 60% of soil particles smaller than a certain grain size, respectively.

Analysis of basic physical properties

The apparent density and water absorption rate of the aggregates were calculated based on the “Coarse aggregate density and water absorption test (basket method) (T 0304-2005)”. As shown in Fig. 5, the apparent density of recycled aggregates is significantly lower than that of natural aggregates, with a difference of 30% and 37.4% between the apparent densities of coarse aggregates and soil, respectively. It is analyzed that the recycled aggregate contains more needle-flake crushed brick pieces with more cement mortar wrapped around the surface. Compared with natural aggregates, there are a large number of closed pores in the mineralized entities of the aggregates, and their apparent densities are significantly smaller than those of natural aggregates. Moreover, the water absorption of RACW as a whole are significantly higher than that of natural aggregates. This high water absorption rate can be attributed to the rough surface, numerous angular edges, and the presence of cement mortar and bricks with high water absorption capacity in the recycled aggregates. During the crushing process, many cracks are generated in the aggregates, which also contributes to the increase in water absorption rate.

The crushing value of the CDW recycled aggregate was obtained based on the “Coarse aggregate crushing value test (T0316-2005)”. As seen in Table 8, the crushing value of recycled CDW aggregates is 80% higher compared to the crushing value of natural aggregates. It is analyzed that, due to the complexity of the components of the CDW aggregate, it not only contains high strength waste concrete, but also contains a large number of waste bricks with low density and high void ratio. Also, the recycled aggregate itself has a large number of cracks after crushing and is slightly looser than the natural aggregate, i.e. its resistance to crushing is inferior to that of the natural aggregate. Nevertheless, the average value of crushing of recycled aggregates is 15.8%, which still meets the corresponding specification requirements.

Analysis on road performance

The analysis of the basic characteristics of RACW indicates that it is suitable for use as a subbase layer in road construction. The subbase, as a component of the pavement structure, transfers loads from the subbase to the cushion layer or soil. Therefore, studying the pavement performance of these aggregates is of crucial importance. This study examines the feasibility of using cement-, lime-, and lime-fly ash-stabilized RACW mixtures as subbase materials, based on multi-dimensional mechanical indicators and various mixing ratios.

Standard compaction test analysis

As depicted in Fig. 6, the maximum dry density of the mixtures varies with different brick-to-concrete ratios (Brick-Concrete Ratio, BCR) and is influenced by the dosage of external admixture. The trend observed is an increase followed by a decrease as the dosage of aggregate increases, resembling a parabolic pattern. The peak maximum dry density is observed within the range of 30–45% aggregate dosage. The stabilized RACW mixtures with different external additives show a similar pattern. The incorporation of soil fills the voids between the aggregate particles, leading to a reduction in porosity. As the soil content decreases, for this type of discontinuously graded coarse-grained soil, with the relative increase in coarse aggregate content, the mixture transforms from a “dense-suspended” structure to a “skeleton-dense” structure, and ultimately reaches a “skeleton-void” structural state29. During this transition, there exists an optimal fine material content that maximizes the dry density30. However, the optimum water content shows a linearly decreasing pattern with increasing aggregate dosage. The analysis suggests that the mixture is a porous material. Among them, the soil material has a strong water absorption, the higher the content of soil, its fine particles and complex pore network make the specific surface area of the mixture larger, the water absorption capacity is stronger, and the optimum water content is higher. Conversely, it is lower.

The maximum dry density of the mixtures varies with the BCR, whereas the optimum moisture content tends to decrease progressively. The variation in the incorporation ratio of RACW does not alter this pattern. Furthermore, the trends observed are similar across different types of externally added stabilizers. Regarding the impact of BCR variations, it is analyzed that the internal structure of waste brick aggregates contains numerous pores, resulting in a high water absorption capacity. A reduction in their incorporation ratio leads to a decrease in the relative proportion of free water within the mixture, thereby increasing the dry density of the mixture and decreasing the optimum moisture content.

For RACW mixtures stabilized by different external admixtures, the effect pattern of different external admixture dosage is significantly different when BCR is changed at the same coarse aggregate dosage. As shown in Fig. 6a, when the external admixture is cement, the optimum water content decreases with the increase of cement admixture, while the maximum dry density does not change significantly. As in Fig. 6b, when the external admixture is lime, the optimum water content increases with the increase of lime admixture, while the maximum dry density has a significant decreasing trend. As in Fig. 6c, the external admixture lime-fly ash showed a similar pattern as when lime was the admixture, but its rate of change with admixture decreased slightly. Furthermore, there are significant differences in the ranges of optimum moisture content and maximum dry density among the RACW mixtures stabilized by the three types of admixtures. As shown in Fig. 6a, the maximum dry density of cement stabilized mixes ranged from 1.805 to 2.147 g/cm3 and the optimum water content ranged from 10.9 to 12.8%. As in Fig. 6b, the maximum dry density of lime stabilized mix ranges from 1.711 to 1.930 g/cm3 and the optimum water content ranges from 11.7 to 15.3%. As shown in Fig. 6c, the maximum dry density range of second ash stabilized mix is 1.627 ~ 1.933 g/cm3 and the optimum water content range is 13.9 ~ 17%. Thus, under the action of the same compaction work, the compaction performance of cement stabilized mix is optimal, followed by lime-fly ash stabilized mix, and lime stabilized mix is slightly inferior to the first two. Similar conclusions were found for the optimum moisture content and its range, which exhibited differences of 1.9%, 3.6% and 3.1%, respectively. The smaller the range, the less sensitive the mix is to moisture content, which in turn simplifies quality control during the construction process.

Unconfined compressive strength (UCS) test analysis

As shown in Fig. 7, all the three externally doped stabilized RACW mixtures can meet the requirements of the specification (JTG D50-2017) for the road pavement subgrade for secondary and lower secondary highways when the traffic load class is medium and light traffic load.

With different BCRs and at the same external dopant dosage, the UCS of the mixtures increased and then decreased with the increase of RACW dosage, showing a parabolic-like law. The peak value exists in the interval of 30% to 45% RACW doping. The same trend is shown in the results of the study on cement stabilized recycled aggregates by Wu et al.31. It indicates that an appropriate increase in the proportion of RACW can improve the “skeleton effect” of the mixture, while an excessive amount of RACW is not conducive to the compaction of the mixture, and on the contrary, reduces the UCS value. Combining with the results of particle analysis, it can be seen that a reasonable particle size distribution can help to form a good grading effect, and improve the physical and mechanical indexes such as compactness and strength of the mixture.

With different recycled aggregate dosage and at the same external dopant dosage, the UCS of the mixture changes with BCR, i.e., as the content of waste bricks decreases, the UCS increases significantly. Specifically, UCS increased significantly with the reduction of brick content, which is consistent with the previous findings of Sheng et al.32. This phenomenon can be attributed to the fact that the analysis suggests that recycled aggregates from crushed concrete have higher strengths and better particle shapes compared to impurities such as waste bricks, and are better able to form a skeletal structure in the mix, thus increasing the UCS.

With different BCRs, at the same RACW admixture, the effect of different admixture of external admixtures follows a similar pattern and UCS is positively correlated with the admixture of external admixtures. It can be seen that cement, lime and fly ash can significantly improve the physic-mechanical properties of the mixtures33,34. Cement hydrolysis and hydration reaction physicochemical effect and hydration products of the skeleton of the joint action to improve the physical and mechanical properties of the mixture34. The physicochemical action of the hydrolysis product (Ca(OH)2) and the skeleton of the cement hydration product work together to make the soil microparticles and microagglomerates form a stable agglomerate structure. The hydration products further encapsulate these agglomerates to form and connect them into a strong whole. The lime, on the other hand, stimulates the potential activity in the RACW and promotes the volcanic ash reaction of the mineral admixtures, further enhancing the strength of the mix34,35. The fly ash, as a filler and active admixture, can improve the mix’s compatibility and late strength36,37 However, it is worth noting that too high dosing may lead to unfavorable phenomena such as increased mixture shrinkage and increased drying cracks. With different BCRs, the percentage intervals of UCS increase due to changes in cement dosage of external admixtures were 0.64% to 2.45%, 0.53% to 2.91% and 4.05% to 14.08%, respectively. The proportional intervals of UCS growth due to change in external admixture dosage of lime stabilized mixes were 1.59% to 6.56%, 3.28% to 11.59% and 1.25% to 4.76% respectively. The proportional intervals of UCS growth due to change in external admixture of lime-fly ash stabilized mixes were 3.08% to 6.45%, 1.35% to 5.71% and 2.27% to 9.20%, respectively.

Using Multifactor analysis of variance (ANOVA) method28, BCR, RASR and external stabilizer ratio (ESR) are found to have significant effect on UCS values as shown in Table 9. Furthermore, the influences of BCR and RASR are more prominent than that of ESR, and their interactive effects are more significant compared to the interactions between BCR and ESR, as well as between ESR and RASR. For instance, when the BCR is high, increasing the dosage of external admixtures can effectively enhance UCS; however, when the BCR is low, the effectiveness of external admixtures is limited. In conclusion, the significance hierarchy for UCS is determined as BCR > RASR > ESR, with congruent results observed between p-values and F-statistics, confirming the statistical coherence of the factor ranking.

Curing age is critical for the strength of the specimens, and the resolution of its evolutionary pattern facilitates the determination of the design strength, and the respective adapted curing age can be determined for the material properties38. The evolution of stabilized RACW mix with UCS at various ages was analyzed as shown in Fig. 8. The three external admixtures (cement, lime, lime-fly ash) ratios are 4%, 8%, and 5%:10%, respectively. The RACW admixture is 30%, and the BCR is 1:1. As shown in Fig. 8, the UCS of RACW mixtures increases with the age of maintenance, the early strength increases faster and faster, while the late strength increases relatively slowly. The primary chemical compositions of RACW are SiO2, CaO, MgO, Al2O3, and Fe2O339,40. When the RACW mixture is exposed to water, the gelling substance produced by the hydration of the active ingredients in it is wrapped around the surface of soil particles and RACW, which enhances the adhesion between them41. However, due to its low reactivity, the internal chemical reactions within the mixture require a sustained period to complete, necessitating measures to activate its reactivity42. Furthermore, different admixtures exhibit distinct UCS growth rates at various stages. The cement stabilized mixture demonstrates the highest growth rate during the rapid period, followed by the lime-fly ash stabilized mixture, and the lime stabilized mixture shows the slowest rate. During the slow period, the cement stabilized mixture maintains the highest UCS growth rate, while the lime stabilized and lime-fly ash stabilized mixtures exhibit similar rates. Throughout the entire curing phase, the UCS values of the cement-stabilized mixture are consistently significantly higher than those of the lime-stabilized and lime-fly ash stabilized mixtures. This variability is attributed to the composition and properties of the materials. Cement exhibits rapid hardening and high strength, whereas lime and fly ash have slower hardening rates and slower strength development. Additionally, the relationship between UCS and curing age can be well analyzed using a power function, which is of great significance for research aimed at reducing construction duration.

Splitting strength test analysis

As shown in Fig. 9, under conditions of constant admixture dosage and uniform aggregate BCR ratio, the splitting strength (Rf) of the mixture initially increases and then decreases with the increase in the amount of RACW. Specifically, when the RACW content is approximately 30 to 45%, the Rf value is relatively high. Analysis indicates that when the RACW content is excessive, fewer bonding interfaces can be formed among soil particles, RACW, and stabilizing binders within the mixture, leading to a decrease in the interfacial bonding strength among these three components. Consequently, the Rf decreases as the interfacial bonding strength diminishes. Therefore, an excessively high incorporation of CDW aggregates can reduce the overall reactivity of the mixture, resulting in a decrease in Rf. Under constant dosages of external stabilizer and RACW, the Rf of the mixture increases as the BCR decreases. When the concrete content is doubled, the Rf of the mixture can increase by 15 to 20%. With the same BCR and the same RACW content, the tensile strength of a mixture with a 6% cement dosage is approximately 1.2 to 1.5 times that of a mixture with a 4% cement dosage. The tensile strength of a mixture with a 12% lime dosage is roughly 1.1 to 1.2 times that of a mixture with an 8% lime dosage. Additionally, the tensile strength of a mixture with 8% lime and 16% fly ash is approximately 1.3 to 1.4 times that of a mixture with 5% lime and 10% fly ash.

Compressive resilient modulus test analysis

Figure 10 illustrates that, at consistent dosages of admixture and BCR, the resilient modulus (E) of the mixture first rises and subsequently falls as the RACW content is increased. The E value reaches a higher level when the content of CDW aggregates is approximately 30 to 45%. With the same dosages of admixture and RACW content, the values of E increase as the proportion of concrete increases. When the concrete content is doubled, the values of E can increase by 10% to 20%. Under the same BCR and RACW content, the tensile strength of a mixture with a 6% cement dosage is approximately 1.15 to 1.20 times that of a mixture with a 4% cement dosage. The tensile strength of a mixture with a 12% lime dosage is roughly 1.12 to 1.17 times that of a mixture with an 8% lime dosage. Additionally, the tensile strength of a mixture with 8% lime and 16% fly ash is approximately 1.05 to 1.12 times that of a mixture with 5% lime and 10% fly ash.

Carbon emission accounting and analysis

This study conducts a comparative analysis of the carbon emissions from road pavement subgrades stabilized with different inorganic binding materials. It focuses on a two-way, two-lane secondary highway as the research subject, with the operational section lengthened to 500 m as the functional unit. The road’s full width is 8.5 m, and the subgrade thickness is set at 15 cm. The construction process adopts the specification recommendation of centralized plant mixing and paver paving machine, and the form of the required energy consumption adopts the energy consumed in the subgrade of the basic unit.

Based on domestic and international research findings, various carbon accounting models have been established according to the life cycle assessment method. Generally, the life cycle of road pavement projects is divided into three stages: materialization, construction, and operation and maintenance43. However, due to the complexity of transportation infrastructure’s operation and maintenance management, which is influenced by numerous factors, and in the whole life cycle carbon emission of ordinary highway, the operation and maintenance stage accounts for 15 to 25%44, which is relatively small, therefore, this study solely focuses on the carbon emission accounting for the materialization and construction phases. The system boundaries for carbon emissions at different stages are defined as follows: during the materialization stage, carbon emissions generated from the extraction, processing, and transportation of primary materials used in road construction are considered; whereas during the construction stage, the primary focus is on carbon emissions arising from mechanical operations such as mixing, transportation, and actual construction processes. The total carbon emissions during the total life-cycle are calculated according to Eqs. (6)–(8):

where \(E_{LCA}\) represents the total life-cycle carbon emissions; \(E_{{{\text{emb}}}}\) represents the embodied carbon emissions in the materialization phase, \(M_{i}\) denotes the consumption of the i-th type of construction material (e.g., mass of cement in tonnes), \(F_{i}\) represents the carbon emission factor of the i-th type of construction material (carbon emissions per unit of activity, sourced from Table 10); \(E_{{{\text{con}}}}\) represents the carbon emissions during the construction Phase, \(E_{{{\text{con}},i}}\) denotes the consumption of the i-th type of energy(e.g., mass of diesel fuel in tonnes), \(EF_{i}\) represents the carbon emission factor of the i-th type of energy (carbon emissions per unit of activity, sourced from Table 10).

The carbon emission factors are determined based on the carbon emission factors published by national or local authorities and published industry research results as a basis, as shown in Table 10. The material or energy consumption data in this study are mainly based on the quota volume of engineering construction. Among them, fly ash is considered a low-value waste material, and its upstream carbon emissions can be neglected. Soil sourced from the construction site does not require consideration of its upstream carbon emissions. Recycled bricks and recycled concrete, used as coarse aggregates to replace crushed stone, are calculated at 50% of the carbon emissions of crushed stone according to relevant regulations46.

This study performs a comparative analysis of carbon emissions for sub-bases stabilized with crushed stone and recycled aggregate, using basic units as the reference for comparison. For sub-bases stabilized with crushed stone, the quantities of primary construction materials per basic unit, along with the energy consumption for mixing, transportation, and construction machinery operations, can be determined according to the Chinese standard (JTG/T 3832-2018) by referring to a quota list. The mix proportions are recommended according to the quota, with the lime-fly ash stabilized type recommended at a mix ratio of 5:15:80, converted using the admixture method. For stabilized recycled aggregate sub-bases, the quantities of machinery energy consumption for mixing, transportation, and construction are calculated based on the maximum dry density and optimum moisture content obtained from compaction tests conducted in this study, along with the requirement that the compaction degree of sub-bases for secondary and lower-level highways should be ≥ 95%. Considering a constant transportation distance of 30 km and similar mixing and construction techniques, these quantities are converted based on the weight ratio corresponding to stabilized crushed stone. According to the analysis above, when the RACW content is 45% and the BCR is 1:2, the UCS at 7 days reaches its peak and meets road usage requirements. Under this premise, a low-dosage stabilizer is selected for carbon emission analysis from a carbon reduction perspective.

The primary building material consumption and construction machinery energy consumption for basic units are presented in Tables 11, 12, and 13. It is noteworthy that the construction machinery energy consumption encompasses the total energy consumed by machinery during mixing, transportation, and the construction process. The study calculates three types of stabilized crushed stone sub-bases: Cement Stabilized Gravel (CSG), Lime Stabilized Gravel (LSG), and Lime-Fly Ash Stabilized Gravel (LFASG). Additionally, it calculates three types of stabilized recycled aggregate sub-bases: Cement Stabilized Recycled Material (CSRM), Lime Stabilized Recycled Material (LSRM), and Lime-Fly Ash Stabilized Recycled Material (LFARM).

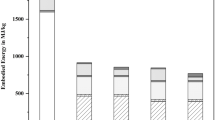

Carbon accounting and comparative analysis

The total carbon emissions of different mixes under the 1 basic unit are calculated in Fig. 11 using Eq. (6) according to the total life cycle carbon emission calculation model for highways given in the study. As shown in Fig. 11: During the construction period, the total carbon emission of the basic unit LSRM > CSG > LSG > LFASG > CSRM > LFARM. overall, the carbon emission of stabilized recycled material category is smaller than stabilized crushed stone category, among which the carbon emission of cement stabilized category is reduced by 19.2%, and the carbon emission of lime-fly ash stabilized category is reduced by 21.6%. The recycling of CDW can effectively reduce the carbon emissions during the construction period of sub-base for highway projects. The lime stabilized category needs to meet the requirements of seven-day UCS values, and the stabilized recycled aggregate needs to increase the external mixing amount of lime from 5 to 8%, which leads to an increase in the total amount of carbon emissions during the construction period.

Analyzing the proportion of carbon emissions in different stages, it can be concluded that during the construction period, the proportion of carbon emissions in the material materialization stage and the construction stage are 81% to 89% and 11% to 19%, respectively. The main source of carbon emissions in the construction period is material materialization. Analyzing the carbon emission structure of the materialization phase, high carbon emission materials such as cement and lime account for a large proportion, stabilized crushed stone category accounts for 94.4% to 95.54%, and stabilized recycled aggregate category 98.68% to 99.19%. Moreover, when the seven-day UCS values of LSRM and LFARM are comparable, substituting fly ash for lime in the stabilization of recycled aggregates can result in a carbon emission reduction of up to 41.45%. In the case of meeting the road performance, the aggregate part of the mix is compared separately, the carbon emissions of cement stabilized, lime stabilized and lime-fly ash stabilized recycled aggregates can be reduced by 82.27%, 81.23% and 78.02% compared with crushed stone aggregates, which is a significant carbon reduction.

Therefore, decreasing the use of high-carbon emission materials, replacing them with low-carbon alternatives, and recycling solid waste are key strategies for reducing carbon emissions during the construction phase. Considering that on-site recycling of CDW mitigates environmental impacts from transportation, landfilling, and land use, the substitution of recycled aggregates for natural aggregates offers substantial carbon reduction advantages.

Conclusions

This study explores the application of recycled aggregate from CDW (RACW) in road subbase layers. Through physical and mechanical property tests, the influence of stabilizers, aggregate content, and the brick-to-concrete ratio (BCR) on performance is investigated. Additionally, a Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) is conducted to compare the carbon emissions during the construction phase with those of natural aggregates. The following conclusions are drawn:

In spite of the fact that the recycled RACW shows poorer morphological characteristics, particle size distribution and physical properties compared to natural aggregates. There is, for example, a significantly lower apparent density of recycled aggregates than natural aggregates, with a difference of 30% and 37.4% between the apparent densities of coarse aggregates and soil, respectively. The stabilized recycled RACW showed feasible potential for application in pavement subgrade (including but not limited to UCS to meet the requirements of subgrade for secondary roads in the current Chinese specification JTG D50-2017).

At a fixed dosage of admixture, the performance of the mixture of recycled aggregates and soil varies significantly with the aggregate content: the maximum dry density exhibits a parabolic trend, peaking at an aggregate content of 30% to 45%; the optimum water content decreases as the coarse aggregate content increases. Increasing the admixture dosage or decreasing the BCR (i.e., reducing the content of waste bricks) can effectively enhance these performance indicators. Besides, based on Multifactor analysis of variance (ANOVA), ESR, RASR and BCR had significant effects, and the order of their effects is BCR > RASR > ESR. At 30% to 45% of recycled aggregate dosage and 1:2 BCR, the optimal ratio existed.

The substitution of natural aggregates with recycled aggregates from waste reduces the carbon footprint of sub-base construction, while road performance properties are realized. Using recycled aggregates from CDW can reduce carbon emissions in subbase construction by 19.2% for cement-stabilized and 21.6% for lime-fly ash-stabilized materials. During construction, material physicochemical emissions, mainly from cement and lime, account for 81%–89% of carbon emissions. Recycled aggregates alone reduce emissions by 78.02%–82.27% compared to crushed stone.

The feasibility of using RACW as a sub-base layer for pavement structure has been demonstrated based on its basic characteristics and pavement performance, and the optimal range of RACW admixture content for road applications has been preliminarily determined. Furthermore, based on LCA analysis, RACW mixtures under stabilizing conditions exhibit significant carbon reduction benefits. However, this research did not explore the stabilization mechanisms of different admixtures, which complicates the identification of the ideal admixture dosage for each respective type. Future research will further analyze the stabilizing mechanisms based on microscopic physicochemical studies to determine the optimal admixture ratios. Furthermore, further research will be conducted on activating the reactivity of RACW.

Data availability

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Khan, A. H. et al. Current solid waste management strategies and energy recovery in developing countries-state of art review. Chemosphere 291, 133088 (2022).

Weber Consulting Environmental Industry Research Expert Team. China construcuction waste disposal industry thematic research and in-depth analysis report. Preprint at http://en.qianzhan.com/report/detail (2024).

Rogelj, J. et al. Paris agreement climate proposals need a boost to keep warming well below 2 °C. Nature 534, 631–639 (2016).

Zhou, X. Resources overview of solid waste. In: Proceedings of the 2016 6th International Conference on Machinery, Materials, Environment, Biotechnology and Computer, (Atlantis Press, Tianjin, China, 2016). https://doi.org/10.2991/mmebc-16.2016.171.

Du, X., Liu, X., Ge, Q., Jiang, L. & Cui, L. A preliminary study on the strategy of construction a “no-waste society” by piloting ‘no-waste city’ to promote the resource utilization of solid waste. Strateg. Study CAE 19, 119–123 (2017).

Shukla, B. K. et al. Sustainable construction practices with recycled and waste materials for a circular economy. Asian J. Civ. Eng. 25, 5255–5276 (2024).

Liu, J., Zhu, Y. & Tian, Z. Research on the path of transportation decarbonization under the vision of carbon neutrality in china. Energy China 43, 6–12+37 (2021).

Sangiorgi, C., Lantieri, C. & Dondi, G. Construction and demolition waste recycling: An application for road construction. Int. J. Pavement Eng. 16, 530–537 (2015).

Poon, C. S. & Chan, D. Feasible use of recycled concrete aggregates and crushed clay brick as unbound road sub-base. Constr. Build. Mater. 20, 578–585 (2006).

Adegoke, D. D., Ogundairo, T. O., Olukanni, D. O. & Olofinnade, O. M. Application of recycled waste materials for highway construction: prospect and challenges. In: Journal of Physics: Conference Series, 1378, 022058 (2019).

Park, T. Application of construction and building debris as base and subbase materials in rigid pavement. J. Transp. Eng. 129, 558–563 (2003).

Poon, C.-S., Qiao, X. C. & Chan, D. The cause and influence of self-cementing properties of fine recycled concrete aggregates on the properties of unbound sub-base. Waste Manage. 26, 1166–1172 (2006).

Zhang, J., Ding, L. & Zhang, A. Application of recycled aggregates from construction and demoliton waste in subgrade engineering: A review. Zhongguo Gonglu Xuebao/China J. Highw. Transp. 34, 135–154 (2021).

Yin, C. Construction waste as subgrade filler feasibility and economic analysis of using recycled aggregate from construction waste as subgrade filler. Eng. Technol. Res. 8, 93–96 (2023).

Zeng, M., Tian, Z., Xiao, J. & Wu, C. Performance of cement stabilized crushed stone pavement base materials containing construction waste. J. Wuhan Univ. Technol. 38, 34–38 (2016).

Su, W., Wei, H., Wang, Z., Li, Y. & Feng, X. Pavement performance of a regenerated cement stabilized mixture on construction waste. J. Chang’an Univ. (Nat. Sci. Ed.) 39, 52–61 (2019).

Cardoso, R., Silva, R. V., Brito, J. D. & Dhir, R. Use of recycled aggregates from construction and demolition waste in geotechnical applications: A literature review. Waste Manage. 49, 131–145 (2016).

Cai, J., Shuai, Z., Chen, Y., Hu, W. & Zhang, H. Review of application research on construction waste in road engineering based on bibliometrics analysis of citespace. J. Munic. Technol. 42, 30–34 (2024).

Stephan, A. & Athanassiadis, A. Quantifying and mapping embodied environmental requirements of urban building stocks. Build. Environ. 114, 187–202 (2017).

Tamanna, K., Raman, S. N., Jamil, M. & Hamid, R. Utilization of wood waste ash in construction technology: A review. Constr. Build. Mater. 237, 117654 (2020).

Ulucan, M. & Ulas, M. A. From waste to circular economy: Exploring the sustainable potential and engineering properties of self-compacting mortars. Sustain. Chem. Pharm. 42, 101781 (2024).

Ulucan, M. From waste to sustainable production: Experimental design and optimization of sustainable concrete using response surface methodology and life cycle assessment. Microelectron. J. 42, 101770 (2024).

Ding, T., Xiao, J. & Tam, V. W. Y. A closed-loop life cycle assessment of recycled aggregate concrete utilization in China. Waste Manage. 56, 367–375 (2016).

Liu, J. & Gao, J. Key problems and countermeasures of carbon emission accounting of transportation infrastructure. Transp. Energy Conserv. Environ. Prot. 17, 4–9 (2021).

Jiang, J., Li, F., Zhang, Z. & Zhou, L. Analysis of carbon reduction benefits from construction waste resource utilization. New Build. Mater. 50, 6–10+43 (2023).

Wu, L., Sun, Z. & Cao, Y. Modification of recycled aggregate and conservation and application of recycled aggregate concrete: A review. Constr. Build. Mater. 431, 136567 (2024).

Sun, J., Liu, L., Xue, D. & Chen, Y. Performance impact of construction waste recycled materials based on multi source heterogeneity. Bull. Chin. Ceram. Soc. 44, 1091–1101 (2025).

Chen, W. et al. Experimental research on mix ratio of construction waste cemented filling material based on response surface methodology. Adv. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2022, 1–15 (2022).

Li, Z., Liu, L., Yan, S., Zhang, M. & Xie, Y. Properties of microscopic particle morphology and particle contact of renewable construction waste mixtures. Constr. Build. Mater. 207, 190–205 (2019).

Yu, J., Liu, S., Wang, T. & Wei, H. Experimental research on compaction characteristics of gap-graded coarse-grained soils. Yantu Gongcheng Xuebao/Chin. J. Geotech. Eng. 41, 2142–2148 (2019).

Wu, J. et al. Experimental study on the application of bick concrete recyced aggregate in water stabilized base. Technol. Highw. Transp. 39, 68–74 (2023).

Sheng, S. & Li, C. Study on anti-fatigue performance of recycled aggregate used in cement stabilized macadam base. J. China Foreign Highw. 41, 350–356.

Panesar, D. K. & Zhang, R. Performance comparison of cement replacing materials in concrete: Limestone fillers and supplementary cementing materials–a review. Constr. Build. Mater. 251, 118866 (2020).

Shi, B.-H., Ning, W.-P., Xu, W. & Dai, S.-R. Application of con-aid soil stabilizer in expedient airfield pavement. Jiaotong Yunshu Gongcheng Xuebao 13, 25–33 (2013).

Dhar, S. & Hussain, M. The strength and microstructural behavior of lime stabilized subgrade soil in road construction. Int. J. Geotech. Eng. 15(471), 483 (2021).

Papadakis, V. G. Effect of supplementary cementing materials on concrete resistance against carbonation and chloride ingress. Cem. Concr. Res. 30, 291–299 (2000).

Ren, Q., Wu, Y., Zhang, X. & Wang, Y. Effects of fly ash on the mechanical and impact properties of recycled aggregate concrete after exposure to high temperature. Eur. J. Environ. Civ. Eng. 26, 683–699 (2022).

Anburuvel, A. The engineering behind soil stabilization with additives: A state of the art review. Geotech. Geol. Eng. 42, 1–42 (2024).

Wang, J., Zhang, J., Cao, D., Dang, H. & Ding, B. Comparison of recycled aggregate treatment methods on the performance for recycled concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 234, 117366 (2020).

Ma, K. et al. Advances in research of performance activation of recycled powders and relevant applications. Cailiao Daobao/Mater. Rep. 38, 100–112 (2024).

Liu, D. et al. Material properties characterization and the excitation of potential activityon construction waste recycled powder. Bull. Chin. Ceram. Soc. 35, 2635–2641 (2016).

Zhang, D., Zhang, S., Huang, B., Yang, Q. & Li, J. Comparison of mechanical, chemical, and thermal activation methods on the utilisation of recycled concrete powder from construction and demolition waste. J. Build. Eng. 61, 105295 (2022).

Fang, H., Cao, Z., Feng, Z. & Chen, S. Carbon emission accounting method and empirical research of high way construction period based on full life cycle theory. Highw. Eng. 46, 92–97+124 (2021).

Research Institute of Highway Ministry of Transport. The concept definition of green low-carbon highway series and the realization path of energy saving and carbon reduction. https://m.chinahighway.com/article/65409378.html (2025).

Gong, Z. & Zhang, Z. A study on embodied environmental profile during the lifecycle of cement. Chin. Civil Eng. J. 37, 86–91 (2004).

Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development of the People’s Republic of China. Carbon emission calculation standard for buildings. https://www.mohurd.gov.cn/gongkai/zhengce/zhengcefilelib/202407/20240719_779260.html (2019).

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. 2006 IPCC Guidelines for National Greenhouse Gas Inventories. https://www.ipcc.ch/report (2006).

National Development and Reform commission. Provincial greenhouse gas inventory guidelines. http://www.edcmep.org.cn (2011).

Acknowledgements

The work described in this paper was supported by the Science and Technology Project of Tianjin Municipal Construction Committee (2016-34); and the Science and Technology Program of Guangdong Province (2017A050501005).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

X.D. conceptualized the concept, methodology, and wrote the original manuscript; Y.W. completed the data visualization, survey, and writing instructions; D.Y. completed the data analysis and editing; W.Z. carried out the data compilation and validation; Y. D. completed the writing and review of the article; N.L. completed the review and revision. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Duan, X., Wang, Y., Yang, D. et al. Evaluation of road performance and carbon emission accounting analysis of recycled aggregates from construction and demolition waste. Sci Rep 15, 29395 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-13354-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-13354-z