Abstract

Barley is one of the basic inputs for the European malting and brewing industry. Fusarium diseases can cause significant losses in grain yield and affect crop and beer quality, leading also to contamination by mycotoxins. The aim of the work was to evaluate efficacy of volume dielectric barrier discharge under different treatment conditions and exposure times and to get benchmarks for decontamination using direct plasma treatment of seeds while preserving seed germinability. Efficacy of low-temperature plasmas impacting on surface of barley seed through short-living (nanosecond) micro-discharges was investigated for seeds artificially inoculated with Fusarium verticillioides, F. culmorum and F. graminearum. Inoculated seeds were exposed to plasma produced in a barrier discharge in synthetic air, humid air, and pure oxygen, at different exposure times. Complete inhibition of spore germination in in vitro conditions was achieved after 30 s (F. verticillioides) or 40 s (F. culmorum and F. graminearum) of plasma exposure. Efficacy of treatments in reducing colony forming units contaminating seeds was obtained after 60 s of exposure (higher than 75%) and up to 99.1% after 4 min of exposure for all three analysed Fusarium species. A reduction > 70% was always obtained under all the tested treatment conditions using different feed gases. This technology could be an environmental-friendly alternative to limit food spoilage by mycotoxigenic fungi, which can compromise the quality and safety of cereals, as this study reports the case study of malting barley.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The growing demand for food poses a huge challenge to the agri-food industry, caused on the one hand by global population growth and on the other hand by the needs to reduce climate changes due to emissions of greenhouse gases. One of the biggest challenges in the agri-food sector are the losses caused by various plant pathogens and pests. To reduce such losses, new non-conventional methods and approaches are needed to replace at least partially the widely used pesticides. As a result, a new field of plasma-assisted farming has emerged that focuses on various forms of low-temperature plasma and its use to treat plants to improve yields and/or quality, safety and shelf life of produce in post-harvest1,2,3,4,5,6,7. Plasma is a physical agent that contains a mixture of atomic/molecular ions, electrons, neutral species, and reactive oxygen and nitrogen species (RONS) that can potentially be involved in biomolecular interactions with plants and pathogens, offering numerous options following the optimization of treatment parameters for each application and purpose6. Treatment with plasma of seeds and other plant propagation materials to enhance germination and growth rate8resistance to biotic and abiotic stresses9 and decrease levels of microbial pathogens and insects10,11 has gained increasing interest in recent years and there have been advancements in various plasma-assisted treatment approaches8,12.

To date, promising results have been obtained using various dielectric barrier discharges (DBDs) as plasma sources used to decontaminate seed surfaces while altering surface properties (e.g., increased wettability) that may affect germination and early plant development13,14,15. DBDs typically produce short-living plasma filaments at room temperature16 which is essential for non-destructive exposure of biological samples. The two basic and most used DBD geometries include volume DBD (VDBD) and surface DBD (SDBD) arrangements17 and, basically, there are three strategies suitable for the exposure of seeds to plasma, the so-called direct, indirect and remote exposure2. While in the case of indirect and remote treatment techniques, biospecimens do not come into direct contact with the active plasma, direct treatment consists of immersing the samples into plasma (i.e., seeds are located in a space where transient plasma filaments may develop along the surface of the seed). The VDBD geometry is particularly suitable for such a direct treatment, where seeds can come into direct contact with a large number of filamentary micro-discharges developing in the space between the electrode surfaces, while SDBD is often used for so-called indirect treatment, where the samples are placed at a defined distance (typically a few millimetres) from the active plasma. In the latter case, seeds interact with the plasma primarily through the diffusion of reactive particles (e.g., ozone) and the impact of photons.

In in vitro studies, indirect treatment with SDBD plasma significantly inhibited spore germination of different fungi and the inhibitory effect of the treatments progressively increased with the extension of the time of exposure to plasma13,18. Different responses to the treatment were recorded among fungal species requiring different exposure time to reach complete inhibition of spore germination, reduction of viability and morphological alterations of cell surface up to spore destruction10,19,20,21,22,23.

Kuzminova et al. 201724 investigated the effect of VDBD on nine different common polymers (mimicking the different structures of more complicated biological systems), bovine serum albumin (chosen as a model protein) and spores of Bacillus subtilis (representing highly resistant bacterial cells) and demonstrated that all tested samples were readily etched by VDBD micro-filaments with reasonable etching rates suitable for the routine bio-decontamination of surfaces.

Barley (Hordeum vulgare L.) is the world’s fourth most important cereal crop after wheat, maize, and rice in terms of production and cultivation area. Barley is mostly used for animal feed but it can also be used for human consumption, as well as in the paper industry and to produce compost bedding. In addition, barley is the most widely used cereal in malt production for breweries and in distilling industries. Some varieties of spring barley, as the cv. Malz used in this work, are largely used for malting in the brewing process. For this use, cereals must have a high grain germination capacity (at least 95%), low protein content, high malt extract, a uniformity of the grain size and the high levels of activity of the degrading enzymes, beta- and alpha amylases, for the natural ethanol fermentation process25. Fungal species of the genus Fusarium and the mycotoxins that they produce (e.g., trichothecenes and zearalenone) are known to be very important contaminants and a major challenge in barley grains and beer production26,27,28. Among seedborne pathogens of cereals, several Fusarium species can reduce seed germination and cause seedling blight as well as seedling foot and stalk rots. Contamination with Fusarium can greatly interfere with the plant metabolism and therefore alter the composition of the grains and brewing-related enzymes, translated into decreased malt yield. Quality issues may arise during malting and brewing with severely infected seeds being associated with the occurrence of gushing and/or changes in colour and flavour of the finished beer. Moreover, several Fusarium species cause contaminations of malt-based feed and food with mycotoxins and toxin derivatives hazardous to humans and animals29. Fungal growth and mycotoxin biosynthesis are strongly influenced by high temperature (optimal range, 25–28 °C) and relative humidity (> 0.90 aw)30. Along with efficient drying and good storage conditions, various postharvest control methods, including chemical, biological and physical treatments, have been proposed to suppress the effects of Fusarium infections on malting barley31. Different studies report methods for treatment of Fusarium-infected burley seeds using hydrogen peroxide and ozone as novel method to control mycotoxins level obtaining a significant reduction of fungal infection, without a decrease of seed germination32,33. They are powerful antioxidant and disinfecting agents in stored products, and the main advantage of this application is certainly that it does not leave chemicals residues or undesirable reaction products throughout malting and brewing. This advantage is in common with low-temperature plasmas technology34 in which the decontamination efficacy of RONS acting as antimicrobial agents20 can be exploited without leaving residues and reducing the germinative energy of seeds.

The aim of this work was to investigate the potential of VDBD geometry for direct seed treatment with cold plasma against three pathogenic Fusarium species with different biological traits, regarding the production of micro and macroconidia, artificially inoculated on the surface of barley grains. Different treatment conditions were tested to optimize the efficacy against fungal pathogens while preserving seed viability.

Results

Discharge characteristics

The VDBD was continuously monitored by recording voltage-current characteristics, indicating stable performance during the treatment. Registered waveforms were used to calculate the total energy delivered to the discharge during one Alternating Current (AC) burst. Results are shown in Fig. 1 with typical voltage-current waveforms during one high-voltage burst composed of four AC cycles, together with characteristic plasma-induced emission spectra in the UV spectral range. In Fig. 1a, the positive/negative spikes present on the current waveform trace individual micro-discharges (each persisting for tens of nanoseconds in the VDBD gap) that are the source of RONS and photons. Figure 1b shows characteristic emission spectra acquired from the discharge gap (averaged over time and space). The dominant radiation in the UV-A region is given by emission bands of diatomic species, more specifically, in the case of air, it is produced by electronically excited states of the nitrogen molecule N2 and the ion N2+. Analysis of emission spectra recorded at medium resolution (see inset in Fig. 1b) confirms the characteristic rotation temperature of the N2/N2+ bands near 300 K (about 26 °C), which is also an indirect indication of a similar gas temperature35.

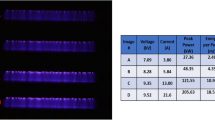

During all the experiments, we never changed the two main parameters of the discharge, namely the amplitude of the AC HV driving waveforms (20 kV peak-to-peak) and the gas flow rate (1 standard litre per minute [slm]), regardless of the working gas. Figure 2 shows the characteristic average VDBD power consumed to produce micro-discharge filaments along with the corresponding O3 and NO2 concentrations measured at the reactor outlet under the three conditions investigated. It turns out that in the case of VDBD produced in all test cases (dry air, humid air, oxygen), ozone is the most important stable product.

Furthermore, we compared O3/NO2 production with and without barley seeds placed in the VDBD gap (Table 1).

Efficacy against Fusarium spp. in in vitro and in vivo experiments

Table 2 reports results of the in vitro experiments showing the efficacy of VDBD to inhibit fungal spore germination. After 10 s of plasma exposure, the inhibition rate was 28.3% in F. verticillioides, 53.3% in F. culmorum, and 62.7% in F. graminearum (always significantly higher compared to shorter treatment times) and increased after 20 s to values ≥ 88.7%. Complete inhibition was achieved after 30 s (F. verticillioides) or 40 s (F. culmorum and F. graminearum) of exposure. These results confirm that VDBD could effectively inhibit these fungi, and the antifungal effects were dependent on the treatment time. It should be noticed that a different composition of the inoculum tested was observed among the three fungal species. F. verticillioides produced abundant microconidia and very few macroconidia (< 2%), while F. culmorum and F. graminearum produced only macroconidia36.

Artificially inoculated barley seeds in the in vivo experiments were individually exposed to VDBD using dry air as working gas and seven different treatment times ranging from 5 s to 4 min. Two-way ANOVA test showed that the efficacy of treatments was significantly affected by fungal species and treatment time (p < 0.0001). Gradual increase in the antifungal efficacy was observed with the increase of the exposure time from 5 s up to 40 s of treatment, reaching a mean value of 78.1%, while a further increase was achieved after 2 min of treatment (95.7%). The highest efficacy of VDBD treatment was recorded against F. graminearum (mean value 80.8%) while F. verticillioides showed the lowest sensitivity to VDBD treatments, with a mean efficacy of 68.4% (Table S1). A significant interaction between the two factors (fungal species and treatment time) was recorded (p = 0.0278). The individual response to treatments in the three fungi is shown in Fig. 3. At the shortest exposure time (5 s) the inhibition was less than 50% for F. verticillioides (39.1%) and F. culmorum (46.8%) and reached 54.7% for F. graminearum. After 40 s of treatment the decontamination efficacy reached 67.1%, 84.2%, and 82.9% for F. verticillioides, F. culmorum, and F. graminearum, in the order, while it was always greater than 97.2% after 4 min of seed exposure to VDBD.

In a further experiment, the efficacy of treatments using three different feeding gases (i.e., dry air, humid air and oxygen) supplied to the plasma system were compared at two different exposure times (10 s and 40 s). The effect of feeding gas on the efficacy of treatments was not significant (p = 0.1887) while significant effects were recorded for the fungal species and exposure time (p < 0.0001). All the interactions between the three factors were significant (p < 0.02). Under the adopted conditions, F. verticillioides was significantly (p = 0.05) more sensitive to treatments compared to F. culmorum and F. graminearum with inhibition rates of 79.3%, 68% and 71.5%, respectively. As expected, antifungal efficacy significantly increased from 10 s (59.3%) to 40 s (86.6%) of VDBD exposure time. A slightly higher mean value of efficacy (75.1%) was obtained using humid air compared to dry air (71.2%) and oxygen (72.5%) (Table S2).

In detail (Fig. 4), after 40 s of exposure, when levels of efficacy > 80% were recorded against the three Fusarium species, the humid air condition provided the highest values (95.6% for F. verticillioides, 92.8% for F. culmorum, and 91.6% for F. graminearum) that, however, only in F. culmorum were significantly different (p = 0.05) from the other two conditions tested. Similarly, after 10 s of treatment, humid air showed, although with no statistical significance, the highest values of efficacy (83.7%) against F. verticillioides compared to dry air (60.9%) and oxygen (71.7%). On the opposite, in the low-efficacy range (40%-65%) that was recorded for F. culmorum and F. graminearum after 10 s of treatment, humid air was the worst performing condition.

Mean values of three replicated samples and standard error (represented by bars) of in vivo efficacy of VDBD plasma, in dry air, at different exposure times on barley seeds against Fusarium verticillioides, F. culmorum, F. graminearum. For each Fusarium species, same letters are not statistically different at the probability level p = 0.05 according to the Tukey’s HSD test.

Mean values of three replicated samples and standard error (represented by bars) of in vivo efficacy against F. verticillioides, F. culmorum, F. graminearum of VDBD plasma treatments using different gases and exposure times on barley seeds. Same letters (per each fungal species and treatment time) are not statistically different at p = 0.05 according to the Tukey’s HSD test.

Seed wettability changes and their consequences

The direct contact of plasma filaments and the action of RONS on the seed coat caused an almost immediate change in the wettability of the outer surface layer, which was tested by measuring the contact angle using deionized water droplets (≈ 10 µl), as shown in Fig. 5. In Fig. 5a, the first (T0) frame of the time-lapse video shows the impact of a droplet on treated barley and a stable droplet on the untreated control seed, used as reference. The shape of the droplet on the reference seed and the contact angle with the surface (> 90°) indicate a hydrophobic surface. The second (T1) frame captures the scene a few seconds later. On the reference, the droplet remained unchanged (including the contact angle), and the droplet on the treated surface was spread out and exhibited a very different contact angle (< 90°), a clear indication of the hydrophilicity of the surface. The third (T2) frame shows the situation approximately 20 s later. The droplet on the reference was still holding, while the droplet on the treated surface disappeared because the water has soaked into the entire surface. The fifteen-second treatment did not seem suitable for quantitative measurements, as the droplets disappeared almost immediately. Therefore, in this work, we tested the contact angle for the shortest treatment time. The water contact angle was estimated by analysing the shape of a droplet (volume of 2 µl) on a given surface (the sessile drop method37. A custom-made device (consisting of a syringe for the droplet deposition, a sample holder, and a camera connected to a computer) was used to capture images of the droplets on untreated and treated seeds. Static contact angles were obtained from images taken immediately after the droplet deposition (using build-in three-point fitting routine). All contact angle measurements were performed in laboratory air at room temperature. The results from quantitative measurements of contact angle (mean ± standard error of 9 samples) at the moment of impact are presented in Fig. 5b. The hydrophobic contact angle of ≈ 120° changes very quickly with treatment for all working gases utilized in this study, as after 5 s of treatment, the angle drops to ≈ 35–40° with slight dependence on gas composition.

Wettability tests: (a) three frames selected from registered time-lapse video of approximately 20 s (T0, T1 and T2), evidencing a super-hydrophilic state of barley coat after 15 s of treatment (D = 0.4); (b) contact angles of DI water droplets (mean ± standard error of 9 samples) on the surface of untreated seeds and after 5 s treatment for synthetic air, ambient air, and oxygen as working gases.

Another morphological observation on treated seeds, compared to the untreated ones, is the rupture of the kernel, that should promote and speed up the germination after the treatment.

Some preliminary germinability tests used to check the germination of treated seeds, in dry conditions, showed a complete germination (i.e., 100% of germinated seeds) for all treatment times, with an increase of the seedling growth assessed at 4 and 6 days after seed exposure to treatments compared to the untreated control. The seeds germination was not affected even by longer treatments (4 min) (Fig. 6).

Discussion and conclusion

Low-temperature plasma (LTP) has a great potential to be used in agriculture and food industry sector. More advances (i.e., low operating temperature, short processing time, effective antimicrobial activity) allow the development of this new technology in the actual agricultural context, in which there is an urgent need to reduce the pesticide use and excess fertilisation, promote organic farming, and guarantee food safety and security although responding to a constant increase of food demand. LTP could contribute to achieving these objectives. Beneficial effects of low temperature plasma applications are reported by several studies that describe this technology as an innovative decontamination tool effective against different microbial pathogens, including both bacteria and fungi contaminating seeds10,18,23 reducing mycotoxin level38,39,40 and with positive effects on seed germination, seedling growth and vigour, that have been also herein confirmed on barley seeds22,34,41. Regarding decontamination activity, possible mechanisms for microbial inactivation are related to damages to cellular structure, causing membrane disruption, morphology changes, oxidation of macromolecules, peroxidation of lipids, and DNA damage. The RONS produced by plasma certainly contribute to the cell death of fungi42,43. This work demonstrates the effectiveness of VDBD treatment against three different species of Fusarium contaminating barley seeds, with different antifungal efficacy achieved depending on the plasma treatment parameters and conditions used. Preliminary evaluation on the inhibition of conidial germination on agarized medium confirms, for all three Fusarium species, a strong positive correlation between the increase of inhibition rate and the exposure time, reaching levels of efficacy > 88% just after 20 s and the complete inhibition after 40 s of exposure. The potentiality of the VDBD treatment in dry air was proved also on artificially inoculated barley seeds, with a reduction of the Fusarium contamination ranging from 74% (F. verticillioides) to 89–92% (F. culmorum and F. graminearum) after 1 min, and more than 90% for all the three species after 2 min of exposure. It is important to emphasize that due to the amplitude modulation of the excitation AC voltage (discharge duty cycle 0.4), the discharge is generated only for a part of a selected exposure time (e.g., an exposure time of 60 s means a net discharge ON interval of 24 s). This point must be considered when comparing the present results with other decontamination experiments performed using continuous AC DBD systems. The low discharge duty cycle allows the gas temperature of the micro-discharges to be kept below the required limit so that seed viability is not compromised. To this point, monitoring the gas temperature through the rotational temperature of the diatomic species is very important in the context of this work, as it allows to rule out decontamination caused by excessive gas temperature inside the plasma filaments, which could also negatively affect seed viability. In other words, when demonstrating a low gas temperature inside radiating plasma filaments, decontamination must be caused by other agents such as RONS, ions, electrons, and VUV-UV photons. Ozone-induced processes are likely to be dominant because transient reactive particles (e.g., electrons, ions, atomic particles, UV photons) only act during the formation of discharge filaments, with the lifetime of each single filament being only a few tens of nanoseconds. The highest levels of ozone are observed in pure oxygen44, where most of the atomic oxygen produced by the electron impact dissociation of the oxygen molecule is consumed to form O3. In synthetic air, both oxygen and nitrogen atoms are created simultaneously during the discharge from the parent molecules. The mixture of atomic and diatomic oxygen and nitrogen then triggers a chain of reactions leading to the formation of nitrogen oxides such as NO2 and N2O45 and consequently significantly reducing the concentration of O3 compared to the pure oxygen case. Post-discharge chemistry becomes even more complex in the presence of hydrogen, i.e., in humid air. Atomic oxygen is now consumed not only in the formation of NxOy, but also in reactions forming hydrogen peroxide H2O2, hydroperoxyl HO2, nitroxyl HNO46,47 which leads to a further decrease in the observable O3 levels. Due to the above, Fusarium conidia inoculated on the surface of barley is almost constantly exposed to discharge products (O3, NO2, H2O2, HNO), while it is periodically attacked by highly transient reactive particles (UV photons, electrons, ions, oxygen atoms, OH radical from plasma filaments) during the whole treatment time.

Under these conditions, additional effects were also detected on the seed surface, in our preliminary observation, with an increase of seed wettability of treated seeds (Fig. 5a, b) and a slight increase of germinability at shorter treatment times (1 min) without compromising seed germination at longer treatment times (up to 4 min). These features show important potential to be studied for further application, in upscale, exploiting at the same time, different advances of plasma treatment related to seed viability and decontamination efficacy8,20,48.

In this study, we explored the role of different factors, including treatment parameters like exposure time and feed gases supplied to the plasma system, on antifungal decontamination efficacy. The main factor affecting the efficacy is certainly the time of exposure to plasma (p < 0.0001), with an improved decontamination efficacy with longer exposure times. This confirms previous results using SDBD and VDBD plasma against various fungal species13,49. Regarding the working gas composition, three different conditions (dry air, humid air and oxygen) were compared for seed treatment. In the range of high efficacy (> 70%), plasma treatments conducted in humid air showed the best results with the highest efficacy compared to dry air and oxygen, likely due to the production of reactive species and the occurrence of other more complex chemical reaction forming hydrogen peroxide H2O2, hydroperoxyl HO2, and nitroxyl HNO.

Some differences in the response to treatment among the three Fusarium species were observed but with various results in different experiments. The macroconidia of the three fungi are multicellular, very similar in shape and in number of cells per spore, and hard to devitalize50. However, different ratios between macroconidia and microconidia, consisting of only one or two cells per spore, among the three species were observed. F. verticillioides produces many microconidia and few macroconidia, while F. culmorum and F. graminearum produce only macroconidia36. In in vitro experiments on agar medium, F. verticillioides showed a higher sensitivity than the other two species to treatments longer than 10 s. Similarly, in in vivo experiments on seeds, in which different feeder gases were tested, F. verticillioides was significantly (p = 0.01) more sensitive than F. culmorum and F. graminearum. This behaviour of F. verticillioides can be due to the abundance of microconidia, easier to devitalize, compared to the macroconidia prevalently produced by F culmorum and F. graminearum.

In conclusion it is noticeable that the VDBD technology has a great potential for decontamination of seeds; the reactive species produced during the treatment directly reached the seed and can inactivate almost completely the fungal inoculum, even at short treatment times, preserving seed germinability.

Besides these results, it is necessary to improve knowledge for the standardization of treatment parameters on seeds to obtain a successful decontamination process of fungi51 without compromising the germinability and the quality of seeds39. There are many factors (seed type, shape or structure, plasma devices and treatment parameters, biochemical and molecular features, post/treatment procedures on treated seeds)8,12 that can influence the efficacy of the treatment, and all of them must be analyzed to successfully propose the low-temperature plasma technology as a tool for seed decontamination in agriculture practice. Promising results obtained in this work using barley seeds of the malting variety Maltz, provide an opportunity to improve yield, safety and quality of barley, malt and beer, frequently compromised by pathogenic Fusarium species.

We must point out that our experiments were conducted on single seeds to best check the discharge system and standardize all treatment parameters and variables. Further studies and different plasma configurations need to be tested for upscaling the technology and allow to handle large quantities of seeds before proposing this technology to the food industry.

Materials and methods

Discharge system

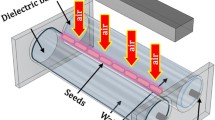

Plasma treatments were performed using the modular 3D-printed flow-through DBD reactor shown in Fig. 7a. The VDBD discharge was generated between two parallel alumina discs. Each disc contained a circular silver electrode deposited on its backside and was sealed in a polyamide holder. The chamber was equipped with gas feed input/output ports and diagnostic windows. The modular concept of this reactor, designed at the Institute of Plasma Physics (IPP) labs (Prague, Czech Republic), allows for the quick sample insertion for treatment and a very straightforward replacement of the discharge electrode(s) to use alternative discharge and/or treatment geometries14,15,52. The multiple streamer micro-discharges were initiated by an electric field formed by the HV waveforms applied to silver electrodes (DBD gap of 3 mm). The reactor was powered by an amplitude-modulated AC HV power supply composed of the TG1010A Function Generator (Aim-TTi, Ltd., Huntingdon, Cambridgeshire, UK), Powertron Model 250 A RF amplifier (Industrial Test Equipment Co., Inc., Port Washington, NY, USA), and an HV step-up transformer. The micro-discharges were produced during a burst of four sine-waves (U = ∼20.7 kV peak-to-peak, fAC = 5 kHz) applied at a fixed repetition frequency of fM = 500 Hz, which implies a discharge duty cycle D = 0.4 (i.e., a fraction of the exposure time, during which the discharge is energized).

The seeds were placed on the alumina surface of the grounded electrode (as shown in Fig. 7b) and exposed (one after another) to the shower of micro-discharges (Fig. 7c) for a selected exposure time. Soon after the treatment, the barley seeds were stored in sterile vials for further processing.

Simplified sketch of the volume dielectric barrier discharge (VDBD) reactor with 3D-printed body equipped with diagnostics windows and input/output gas ports and fitted with replaceable DBD electrodes, according to Fujera et al. 202553; the grounded (bottom) electrode served as a sample holder for treated seeds (a). Barley seed placed on the sample holder (grounded electrode) (b). Barley seed exposed to VDBD micro-discharges (c).

A Tektronix oscilloscope DPO5204 (2 GHz, 10 GS/s, Tektronix, Inc., Beaverton, OR, USA) was used to record the VDBD characteristics, specifically the HV, current, and plasma-induced emission (PIE) waveforms. The discharge HV waveforms were sampled using a Tektronix P6015 HV probe. The current pulses produced by individual micro-discharges were monitored via the voltage drop across a non-inductive shunt resistor inserted between the grounded electrode and the grounding lead and were measured by a Tektronix TPP1000 HV probe. The transferred charge was determined via a non-inductive measuring capacitor (C = 0.47 µF) inserted into the grounding lead and analysing the charge-voltage characteristics (Lissajous figures). The reactor was fed with working gas through a Bronkhorst HI-TEC model mass-flow controller (Ruurlo, Netherlands). The discharge was generated in dry air (99.999%; containing H2O < 2 ppm, CO + CO2 < 0.4 ppm), humid air (relative humidity of 60%), and oxygen (99.999%; containing N2 < 5 ppm, H2O < 2 ppm, CO + CO2 < 0.4 ppm) with flows of 1 slm. Optical emission produced by micro-discharges was registered by a UV-vis grating spectrometer iHR-320 (Jobin-Yvon, Horiba Instruments Inc., Edison, NJ, USA). The principal gaseous discharge products (ozone and NOx species) were detected at the output port of the DBD reactor. A non-dispersive UV absorption ozone monitor (Advanced Pollution Instrumentation Model 450, Teledyne Instruments, San Diego, CA, USA) and a chemiluminescence NOx analyser (Model 200EM, Teledyne Instruments, San Diego, CA, USA) were used to quantify the discharge products with or without seeds placed in the gap.

Efficacy against Fusarium spp. in in vitro and in vivo experiments

An evaluation of the efficacy of VDBD plasma treatment against Fusarium spp. was conducted both in vitro by conidial germination test on agarized medium and in vivo on barley seeds. F. verticillioides strain 232 F, F. culmorum strain 7FC, and F. graminearum strain 206 F, stored at 4 ± 1 °C, were revitalized on potato dextrose agar [PDA: infusion from 200 g peeled and sliced potatoes kept at 60 °C for 1 h, 10 g D-(+)-glucose, adjusted at pH 6.5, 20 g agar Oxoid No. 3; per litre] to obtain fresh cultures. To improve conidia production, cultures were grown at 25 ± 1 °C in the darkness for 3 days and then exposed for 7 days to a combination of two daylight (Osram, L36W/640) and two near-UV (Osram, L36/73) lamps with a 12 h light/dark photoperiod. Conidia suspensions were obtained in sterile distilled water by scraping the colonies with a sterilized loop, filtered through glass wool to remove mycelium fragments, and concentration adjusted to 1 × 105 conidia mL− 1 by using a hemocytometer.

For the in vitro test, aliquots (10 µL) of conidial suspension were spotted on Water Agar (WA: 20 g L− 1 agar Oxoid No. 3) disks of 6 mm of diameter, placed on the sample holder of the reactor and submitted to the plasma treatment using different exposure time (1, 2, 5, 10, 20, 30, 40 and 60 s). Untreated disks inoculated with untreated conidia were used as negative controls. After the treatment, the disks were incubated in a moist chamber at 25 ± 1 °C in the dark. After 18 h, microscopic observations were conducted at ×200 magnification on random samples of 100 conidia from three replicated spots per each condition. The inhibition rate (Ir %) caused by plasma treatment was calculated by the formula: Ir % = (1 - average number of conidia germinated on treated disks/average number of conidia germinated on unexposed control disks) × 100%.

For the in vivo test, seeds of spring barley (Hordeum vulgare L., cv. Malz) were artificially inoculated with the three Fusarium species. For inoculation, 1 mL of conidial suspension (1 × 105 conidia mL− 1) was sprayed on 100 barley seeds to obtain a final concentration of 1 × 103 conidia seed− 1. To achieve a uniform distribution of fungal spores on their surface, seeds were continuously mixed during inoculation using an electric rotor. The seeds were then placed on sterile paper disks, air dried at room temperature under aseptic conditions in a laminar flow cabinet and maintained in sterilized glass tubes.

For treatment, seeds were individually exposed to VDBD. In a first experiment, the three species of Fusarium were exposed to plasma in dry air and seven different exposure times were compared (i.e., 5 s, 10 s, 20 s, 40 s, 1 min, 2 min and 4 min). In a second experiment, three different treatments conditions (i.e. VDBD in dry air, humid air and oxygen) were compared, with an exposure time of 10 s and 40 s.

To detect and count viable spores after VDBD treatment, two days after treatment, three replicated samples of ten seeds per each treatment were placed in 1 mL of sterile distilled water, added with 0.05% Tween 20 and stirred by vigorous vortexing for 1 min to detach fungal spores from seed surface. Aliquots (100 µL) of the washing suspensions and ten-fold serial dilutions were spread on the surface of a Fusarium selective culture medium [15 g peptone, 1 g KH2PO4, 0.5 g MgSO4·7H2O, 20 g agar Oxoid No. 3, 0.75 g pentachloronitrobenzene (PCNB), 0.3 g streptomycin and 0.12 g neomycin, per litre of distilled water]. Plates were incubated at 25 ± 1 °C in the dark to allow fungal colonies growth and, after four days of incubation, single colonies were counted, the number of colony-forming units (CFUs) seed− 1 were determined to estimate the decontaminant antifungal effect of treatments. Untreated inoculated and mock seeds inoculated with sterile water served as control checks. Decontamination efficacy (%) of treatments was calculated on the basis of the percentage of CFUs on the untreated seeds.

In the experimental conditions adopted, the level of viable inoculum detected on the seeds used for treatments was similar for the three pathogens and equal to 0.9 × 102 for F. verticillioides and F. culmorum, and 1.4 × 102 CFUs seed− 1 for F. graminearum. It should be noticed that, after prolonged storage periods of seeds inoculated with F. graminearum, the number of CFUs seed− 1 was drastically reduced, hence plasma treatment for this species was carried out after a shorter incubation time, i.e., at 2 days after inoculation (DAI), compared to the other two species (7 DAI).

Effects of treatments on wettability and germinability of seeds

Changes in surface wettability in response to the DBD treatment were explored by placing a drop (2 µl) of distilled water on the seed surface and time-lapse video recording using a USB microscope immediately after treatment. First, a water droplet was placed on the control seed sample, and then immediately, the second droplet was placed on the plasma-treated sample (exposure time of 15 s). Three selected frames showed the dynamics from a time-lapse video used to register the behaviour of small water droplets located on the surface of treated barley and untreated control seed used as reference. One reference seed was placed on the USB microscope stage before registration began, the exposed seed was placed next to the reference seed immediately after treatment (VDBD in synthetic air, 15 s of exposure time). Then, a small droplet of water was placed first on the reference seed and immediately after another droplet of similar volume on the treated seed.

Additionally, the seven different exposure times (i.e., 5 s, 10 s, 20 s, 40 s, 1 min, 2 min and 4 min), tested in the decontamination experiment, in dry conditions, were used to assess the germinability of treated seeds. So, the seeds were exposed to the VDBD treatment and the day after placed on water agar medium and incubated at 21 ± 1 °C in darkness. Then, the germination was checked daily. All observations were made on three replicated samples, each consisting of 30 seeds, for each treatment.

Statistical analysis

All data were statistically analysed by ANOVA (Analysis of Variance) using OriginPro software version 2024b, (OriginLab Corporation, Northampton, MA, USA). Normal distribution and homogeneity of variance were preliminarily checked, and a completely randomized design was applied to investigate the effect of exposure time, feed gas, and fungal species on the efficacy of plasma treatments. Multiple-way ANOVA tests were conducted to evaluate the contribution of each factor (treatment times, fungal species and feeder gases) and the interaction between them, on the inhibition rate. Tukey’s HSD (Honestly Significant Difference) test was used to identify differences at confidence intervals (p) of 0.05.

Data availability

Data supporting this study are included within the article.

References

Weltmann, K. D. et al. The future for plasma science and technology. Plasma Processes Polym. 16, 1. https://doi.org/10.1002/ppap.201800118 (2019).

Šimek, M. & Homola, T. Plasma-assisted agriculture: history, presence, and prospects—a review. Eur. Phys. J. D. 75, 7. https://doi.org/10.1140/epjd/s10053-021-00206-4 (2021).

Ucar, Y., Ceylan, Z., Durmus, M., Tomar, O. & Cetinkaya, T. Application of cold plasma technology in the food industry and its combination with other emerging technologies. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 114, 355–371. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tifs.2021.06.004 (2021).

Katsigiannis, A. S., Bayliss, D. L. & Walsh, J. L. Cold plasma for the disinfection of industrial food-contact surfaces: an overview of current status and opportunities. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 21 (2), 1086–1124. https://doi.org/10.1111/1541-4337.12885 (2022).

Susmita, C. et al. Non-thermal plasmas for disease control and abiotic stress management in plants. Environ. Chem. Lett. 20 (3), 2135–2164. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10311-022-01399-9 (2022).

Pańka, D. et al. Can cold plasma be used for boosting plant growth and plant protection in sustainable plant production?? Agronomy 12, 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy12040841 (2022).

Adamovich, I. et al. The 2022 plasma roadmap: low temperature plasma science and technology. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 55, 37. https://doi.org/10.1088/1361-6463/ac5e1c (2022).

Waskow, A., Howling, A. & Furno, I. Mechanisms of Plasma-Seed treatments as a potential seed processing technology. Front. Phys. 9, 1456. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphy.2021.617345 (2021).

Priatama, R. A., Pervitasari, A. N., Park, S., Park, S. J. & Lee, Y. K. Current advancements in the molecular mechanism of plasma treatment for seed germination and plant growth. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23, 9. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms23094609 (2022).

Mravlje, J., Regvar, M. & Vogel-Mikuš, K. Development of cold plasma technologies for surface decontamination of seed fungal pathogens: present status and perspectives. J. Fungi. 7, 8. https://doi.org/10.3390/jof7080650 (2021).

Recek, N. et al. Germination and growth of Plasma-Treated maize seeds planted in fields and exposed to realistic environmental conditions. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24, 7. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms24076868 (2023).

Waskow, A., Avino, F., Howling, A. & Furno, I. Entering the plasma agriculture field: an attempt to standardize protocols for plasma treatment of seeds. Plasma Processes Polym. 19, 1. https://doi.org/10.1002/ppap.202100152 (2022).

Ambrico, P. F. et al. Surface dielectric barrier discharge plasma: a suitable measure against fungal plant pathogens. Sci. Rep. 10, 1. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-60461-0 (2020).

Ambrico, P. F. et al. On the air atmospheric pressure plasma treatment effect on the physiology, germination and seedlings of Basil seeds. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 53, 10. https://doi.org/10.1088/1361-6463/ab5b1b (2020).

Homola, T. et al. Direct treatment of pepper (Capsicum annuum L.) and melon (Cucumis melo) seeds by amplitude-modulated dielectric barrier discharge in air. J. Appl. Phys. 129, 19). https://doi.org/10.1063/5.0039165 (2021).

Kogelschatz, U., Eliasson, B. & Egli, W. From Ozone Generators to Flat Television Screens: History and Future Potential of Dielectric-Barrier Discharges (Springer, 1999).

Brandenburg, R. Dielectric barrier discharges: progress on plasma sources and on the understanding of regimes and single filaments. Plasma Sources Sci. Technol. 26, 5. https://doi.org/10.1088/1361-6595/aa6426 (2017).

Veerana, M., Yu, N., Ketya, W. & Park, G. Application of Non-Thermal plasma to fungal resources. J. Fungi. 8, 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/jof8020102 (2022).

Ambrico, P. F. et al. Reduction of microbial contamination and improvement of germination of sweet Basil (Ocimum Basilicum L.) seeds via surface dielectric barrier discharge. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 50, 30. https://doi.org/10.1088/1361-6463/aa77c8 (2017).

Adhikari, B., Pangomm, K., Veerana, M., Mitra, S. & Park, G. Plant disease control by Non-Thermal Atmospheric-Pressure plasma. Front. Plant. Sci. 11, 523. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2020.00077 (2020).

Taheri, S., Brodie, G. I., Gupta, D. & Jacob, M. V. Afterglow of atmospheric non-thermal plasma for disinfection of lentil seeds from botrytis grey mould. Innovative Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 66, 452. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ifset.2020.102488 (2020).

Mildaziene, V., Ivankov, A., Sera, B. & Baniulis, D. Biochemical and physiological plant processes affected by seed treatment with Non-Thermal plasma. Plants 11, 7. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants11070856 (2022).

Mravlje, J. et al. Decontamination and germination of buckwheat grains upon treatment with oxygen plasma glow and afterglow. Plants 11, 10. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants11101366 (2022).

Kuzminova, A. et al. Etching of polymers, proteins and bacterial spores by atmospheric pressure DBD plasma in air. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 50, 13. https://doi.org/10.1088/1361-6463/aa5c21 (2017).

Rani, H. & Bhardwaj, R. D. Quality attributes for barley malt: the backbone of beer. J. Food Sci. 86 (8), 3322–3340. https://doi.org/10.1111/1750-3841.15858 (2021).

Malachova, A. et al. Fusarium Mycotoxins in various barley cultivars and their transfer into malt. J. Sci. Food Agric. 90 (14), 2495–2505. https://doi.org/10.1002/jsfa.4112 (2010).

Běláková, S., Benešová, K., Čáslavský, J., Svoboda, Z. & Mikulíková, R. The occurrence of the selected fusarium Mycotoxins in Czech malting barley. Food Control. 37 (1), 93–98. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodcont.2013.09.033 (2014).

Vaclavikova, M. et al. Emerging Mycotoxins in cereals processing chains: changes of enniatins during beer and bread making. Food Chem. 136 (2), 750–757. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2012.08.031 (2013).

Nielsen, L. K., Cook, D. J., Edwards, S. G. & Ray, R. V. The prevalence and impact of fusarium head blight pathogens and Mycotoxins on malting barley quality in UK. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 179, 38–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2014.03.023 (2014).

Homdork, S., Fehrmann, H. & Beck, R. Influence of different storage conditions on the Mycotoxin production and quality of Fusarium-infected wheat grain. J. Phytopathol. 148 (1), 7–15. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1439-0434.2000.00461.x (2000).

Ng, C. A. et al. Methods for suppressing fusarium infection during malting and their effect on malt quality. Czech J. Food Sci. 39 (5), 340–359. https://doi.org/10.17221/221/2020-CJFS (2021).

Kottapalli, B., Wolf-Hall, C. E. & Schwarz, P. Evaluation of gaseous Ozone and hydrogen peroxide treatments for reducing fusarium survival in malting barley. J. Food Prot. 68 (6), 1236–1240. https://doi.org/10.4315/0362-028X-68.6.1236 (2005).

Conte, G. et al. Mycotoxins in feed and food and the role of Ozone in their detoxification and degradation: an update. Toxins (Basel). 12, 8. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins12080486 (2020).

Perea-Brenes, A. et al. Comparative analysis of the germination of barley seeds subjected to drying, hydrogen peroxide, or oxidative air plasma treatments. Plasma Processes Polym. 19, 9. https://doi.org/10.1002/ppap.202200035 (2022).

Šimek, M. Optical diagnostics of streamer discharges in atmospheric gases. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 47, 46. https://doi.org/10.1088/0022-3727/47/46/463001 (2014).

Leslie, J. F. & Summerell, B. A. The Fusarium Laboratory Manual (Wiley, 2006).

Neumann, A. W. & Good, R. J. Techniques of measuring contact angles. Surface Colloid Sci.. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4615-7969-4_2 (1979).

Doshi, P. & Šerá, B. Role of Non-Thermal plasma in fusarium inactivation and Mycotoxin decontamination. Plants 12, 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants12030627 (2023).

Feizollahi, E., Iqdiam, B., Vasanthan, T., Thilakarathna, M. S. & Roopesh, M. S. Effects of atmospheric-pressure cold plasma treatment on Deoxynivalenol degradation, quality parameters, and germination of barley grains. Appl. Sci. (Switzerland). 10, 10. https://doi.org/10.3390/app10103530 (2020).

Wang, Y. et al. Effective Inhibition of fungal growth, Deoxynivalenol biosynthesis and pathogenicity in cereal pathogen fusarium spp. By cold atmospheric plasma. Chem. Eng. J. 437, 856. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2022.135307 (2022).

Mazandarani, A., Goudarzi, S., Ghafoorifard, H. & Eskandari, A. Evaluation of DBD plasma effects on barley seed germination and seedling growth. IEEE Trans. Plasma Sci. 48 (9), 3115–3121. https://doi.org/10.1109/TPS.2020.3012909 (2020).

Hoppanová, L. & Kryštofová, S. Nonthermal plasma effects on fungi: applications, fungal responses, and future perspectives. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 11592. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms231911592 (2022).

Rotondo, P. R. et al. Physicochemical properties of plasma-activated water and associated antimicrobial activity against fungi and bacteria. Sci. Rep. 15 (1), 5536. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-88369-7 (2025).

Homola, T., Prukner, V., Hoffer, P. & Šimek, M. Multi-hollow surface dielectric barrier discharge: an Ozone generator with flexible performance and supreme efficiency. Plasma Sources Sci. Technol. 29, 9. https://doi.org/10.1088/1361-6595/aba987 (2020).

Herron, J. T. Modeling studies of the formation and destruction of no NO in pulsed barrier discharges in nitrogen and air. Plasma Chem. Plasma Process. 21, 581–609. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1012003218939 (2001).

Sieck, L. W., Herron, J. T. & Green, D. S.Chemical kinetics database and predictive schemes for humid air plasma chemistry. Part I: positive ion–molecule reactions. Plasma Chem. Plasma Process. 20, 235–258. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1007021207704 (2000).

Herron, J. T. & Green, D. S. Chemical kinetics database and predictive schemes for nonthermal humid air plasma chemistry. Part II. Neutral species reactions. Plasma Chemi. Plasma Process. 21, 459–481. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1011082611822 (2001).

Adhikari, B., Adhikari, M. & Park, G. The effects of plasma on plant growth, development, and sustainability. Appl. Sci. (Switzerland). 10, 17. https://doi.org/10.3390/app10176045 (2020).

Rotondo, P. R. et al. Exploring factors influencing the inhibitory effect of volume dielectric barrier discharge on phytopathogenic fungi. Plasma Chem. Plasma Process. 43 (6), 1819–1842. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11090-023-10394-z (2023).

Mravlje, J. et al. The sensitivity of fungi colonising buckwheat grains to cold plasma is species specific. J. Fungi. 9, 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/jof9060609 (2023).

de Oliveira, A. C. D. et al. Application of cold atmospheric plasma for decontamination of toxigenic fungi and mycotoxins: a systematic review. Front. Microbiol. 15, 14. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2024.1502915 (2024).

Doležalová, E., Prukner, V., Kuzminova, A. & Šimek, M. On the inactivation of Bacillus subtilis spores by surface streamer discharge in humid air caused by reactive species. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 53, 24. https://doi.org/10.1088/1361-6463/ab7cf7 (2020).

Fujera, J., Hoffer, P., Prukner, V. & Šimek, M. Quantifying plasma dose for barley seed treatment by volume dielectric barrier discharges in Atmospheric-Pressure synthetic air. Plasma 8, 1. https://doi.org/10.3390/plasma8010011 (2025).

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge: MUR-Fondo Promozione e Sviluppo – DM 737/2021 CUP H99J21017820005 funded by European Union – Next Generation EU PlaTEC; European Cooperation in Science and Technology, CA19110; Ministero dell’Istruzione, dell’Università e della Ricerca, PNRR Missione 4, Partenariati estesi PE0000003 ONFOODS; and Ministero delle Imprese e del Made in Italy, Dipartimento per le politiche per le imprese, Progetto PATENT, Prog n. F/350301/04/X60 CUP B99J24000540005 and ERC Seeds UNIBA-2023-UNBACLE-0244251.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

P.R.R. and C.R. performed the experiments and data analyses and wrote the original draft of the manuscript for the sections related to the biological experiments. M.Š., P.H., J.F., and V.P. performed the plasma experiment, analyzed the spectral emission and wrote the original draft of the manuscript for the physics sections. R.M.D.A. and M.Š. designed the experiments and provided funding for experimental activities. F.F. contributed to the experiment design and critically revised the paper. R.M.D.A. supervised the experiments and data analysis, supervised and complemented the writing of the manuscript. M.Š. designed the plasma reactor and optical setup and supervised and complemented the writing of the manuscript. All the authors equally contributed to the critical review and editing of the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Rotondo, P.R., Rotolo, C., Hoffer, P. et al. Decontaminant activity of volume dielectric barrier discharge against Fusarium spp. on barley seeds. Sci Rep 15, 28106 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-13401-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-13401-9