Abstract

Dissolved oxygen (DO) is a key variable in water quality management of lakes and reservoirs. The prediction of DO dynamics is challenging due to interactions of ecological, biogeochemical, and physical processes strongly influenced by climate warming. We observed a pronounced metalimnetic oxygen minimum (MOM) in the eutrophied Panjiakou Reservoir, China. In this study, we simulated the vertical DO distribution with a well-established three-dimensional water quality model, combined with multi-point synchronous monitoring data to accurately reproduce the spatial and temporal extent of the MOM and explore the responses of DO stratification structure and the MOM to climate warming. We found that: From the perspective of physical structure, thermal stratification was the initial force driving DO vertical stratification, which showed a certain lag compared with thermal stratification. From the perspective of biochemical processes, oxygen production by photosynthesis, oxygen consumption by respiration, and microbial decomposition of algal biomass affected the vertical distribution of DO; Increases in temperature led to an earlier formation of thermal stratification, as well as increases in duration and the enhancement of stability. The intensification of the vertical density gradient further limited the vertical exchange of DO. In addition, increases in temperature led to earlier outbreaks of algal blooms and increases in concentrations of algae-derived particulate organic matter sinking to the metalimnion, leading to decreases in DO concentrations. The MOM usually occurs from July to September every year. A 2 °C increase in atmospheric temperature advances the MOM onset by 8 days and extends its duration by 12 days. Therefore, climate warming has had a substantial effect on the DO regime in Panjiakou Reservoir. A deeper understanding of the DO dynamics of stratified lakes and reservoirs under the influence of climate change is needed for optimizing reservoir management.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The amount of dissolved oxygen (DO) in surface waters is an essential prerequisite for many aquatic organisms and the loss of oxygen comes along with severe water quality deteriorations, fish-kills and collapse of population of aerobic organisms1,2,3. Furthermore, complete oxygen depletion induces the production of toxic compounds such as H2S and NH3 as well as the release of unfavorable substances from sediments (manganese, iron, nutrients)4. In water resources management, DO concentrations are therefore top level water quality indicators. They are easy to measure and highly sensitive against environmental stressors including organic pollution, global change, nutrient input and eutrophication.

Thermal stratification of a water body is the initial force driving the vertical distribution of DO concentrations. Stable thermal stratification hinders the exchange of warm water in the epilimnion and cold water in the hypolimnion, water in the hypolimnion cannot exchange with atmospheric oxygen and is therefore subject to gradual depletion by respiration and the oxygenation of reduced inorganic compounds. High oxygen depletion rates then lead to anoxic deep waters (metalimnion and hypolimnion) and associated changes in aquatic biogeochemical cycling5,6,7. Accordingly, the prediction of DO dynamics in stratified lakes and reservoirs continues to attract the attention of limnologists. Many lakes and reservoirs around the world suffer from poor oxygen conditions particularly in their deep waters. These conditions may be accelerated by pressures from climate change8,9. DO depletion in the hypolimnion is of utmost relevance for lake management. We have already deep insights into the relevant processes and powerful concepts exist for the prediction of oxygen dynamics. More than 900 papers have been published about this topic (Web of Science search on the keywords: lake or reservoir & oxygen & hypolimnion). Hutchinson10 introduced concepts for volumetric hypolimnetic oxygen demand (VHOD) and areal hypolimnetic oxygen demand (AHOD). A simple but powerful approach to hypolimnetic oxygen dynamics by Livingstone and Imboden11 is based on the separation of pelagic (i.e. a volume-related process) oxygen depletion from sediment-related oxygen consumption (i.e. an area-related process). This simple approach, based on lake morphometry, can explain large parts of oxygen dynamics along the vertical axis in many lakes4,12.

In contrast, little attention has been paid to DO loss within the metalimnion and the occurrence of metalimnetic oxygen minima (MOM) is far less understood, only 171 papers have been published about this topic (Web of Science search on the keywords: lake & oxygen & metalimnion or reservoir & oxygen & metalimnion). Factors contributing to MOM formation include natural and anthropogenic factors. Natural factors can be further divided into biochemical and physical processes. Biochemical processes primarily involve the in-situ consumption of DO13,14,15,16,17,18,19, where organic matter enters the metalimnion in different ways and decomposes under microbial action20,21. In addition to oxygen consumption, the vertical DO transport is equally important for MOM formation and development22. Anthropogenic factors, such as water intake from the metalimnion and the installation of oxygenation equipment (epilimnetic mixing and hypolimnetic oxygenation) in lakes and reservoirs, can also lead to MOM23,24,25. As state above, most of these studies focused on analyzing the mechanisms of DO depletion through experimental methods, simulating the oxygen loss in the metalimnion and predicting its future evolution remains a challenge. Joehnk and Umlauf26 present a one-dimensional physical-biological coupled model to simulate the MOM in Lake Ammer, source and sink terms for surface re-aeration, photosynthetic production, respiration, biochemical oxygen demand and sediment oxygen demand are included. However, ecosystem components like phytoplankton or nutrient dynamics are not considered in the model, so DO dynamics cannot be combined with ecological dynamics. Mi et al.19 simulated the MOM in the Rappbode Reservoir with a two-dimensional water quality model (CE-QUAL-W2) to systematically quantify the chain of events leading to its formation.

Climate change has strong impacts on the thermal dynamics of water bodies worldwide27,28,29. Altogether, the influence of temperature changes on thermal stratification characteristics, such as the stratification stability and duration has been intensively researched by limnologists, paying little attention to the vertical DO structure and its subsequent impact on the MOM. Climate change has strong impacts on the thermal dynamics of water bodies worldwide27,28,29. On a global scale, the warming of lakes and reservoirs in the mid-to-high latitudes of the Northern Hemisphere is more pronounced than in tropical regions30,31,32. Many studies have shown that climate warming has intensified the summer thermal stratification in tropical and temperate deepwater lakes and reservoirs but reduced vertical mixing in winter. Kraemer et al.33 used a one-dimensional hydrodynamic model to study the impact of climate warming on the thermal stratification structure of Lake Geneva, finding that an increase in temperature reduced the duration of winter mixing periods. Sahoo and Schladow34 simulated the impact of climate warming on the thermal stratification of Tahoe Lake, and found that the water temperature will increase by 0.15 °C/a, the thermal stability would increase by 0.39 kJ/(m2 a). The thermal characteristics of the world’s second-deepest lake, Lake Tanganyika35,36, as well as Lake Zurich (Livingstone 2003), Lake Victoria37, and Lake Kariba38, show similar response mechanisms. Increases in temperature cause epilimnetic water temperature to rise and the density difference between the bottom and surface layers to increase significantly, hindering vertical mixing and enhancing thermal stability. The solubility of oxygen in water decreases with the increase of temperature, for every 1 °C increase in temperature, the solubility of oxygen decreases by 1.6% to 2.8% (equivalent to 0.1 mg/L to 0.4 mg/L)39, and the decline in DO is more pronounced for polar and temperate lakes40. Additionally, the strengthening of thermal stratification stability caused by increased air temperature makes it more difficult for DO in the epilimnion to be transported to the metalimnion and hypolimnion, resulting in long-term hypoxia and anaerobic in the metalimnion and hypolimnion41,42.

In this publication, we used Panjiakou Reservoir as a test site, and applied the three-dimensional Environmental Fluid Dynamics Code (EFDC) with a spatially explicit representation of hydrodynamics, oxygen, nutrients, and phytoplankton community dynamics to elucidate the response of DO stratification to future climate warming. The reservoir is a drinking deepwater reservoir in North China, it supplies drinking water for more than 20 million people. Between 2016 and 2018, Panjiakou Reservoir experienced severe hypoxia triggering fish kill events, aggravated eutrophication, and severe odor issues in discharged water, resulting in a suspension of water supply lasting 671 days. Based on this model, we were interested in finding out the influence of temperature changes on DO considering both the physical factors (thermal stratification characteristics) and the biochemical factors (algae growth and their decomposition). It is expected that our study will help reservoir operators effectively control DO depletion in the metalimnion so as to mitigate the negative influence caused by the increase in air temperature.

Methods

Study site and measurements

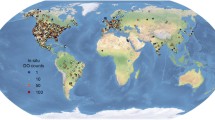

Panjiakou Reservoir (the water source of Water Diversion Project from Luanhe River to Tianjin) is located at the junction of Tangshan City and Chengde City in Hebei Province, supplying drinking water to more than 20 million people (Fig. 1). It is a long and narrow drinking water reservoir in North China with a steep bathymetry, a maximum volume of 29.3 × 108 m3, a catchment area of 33,700 km2, a mean depth of 14 m, and a maximum depth of 80 m. It receives water from three upstream rivers and drains into the Daheiting Reservoir. To promote economic development, aquaculture industry was vigorously developed in the early stage of the reservoir, and the accumulation of bait and fish excreta in the water led to eutrophication. Although fish cage farming was regularized in 2016, the water quality is still in a mesotrophic state, with high concentrations of nitrogen and phosphorus and frequent algal blooms. The Panjiakou Reservoir is a typical warm monomictic water body with strong stratification in summer.

At a location in front of the dam (L1), we conducted routine water quality monitoring once per month, using a multiparameter probe (YSI, EXO-1, USA) with sensors for Chla fluorescence, temperature, electrical conductivity, pressure (for depth), and DO. Simultaneously, at water depths of 1, 3, 6, 9, 12, 14, 16, 17, 18, 20, 25, 30, 35, and 40 m, we collected 2 L water samples from each layer for the determination of total carbon (TC), particulate organic carbon (POC), dissolved organic carbon (DOC), and dissolved inorganic carbon (DIC).

Numerical model

A three-dimensional water quality model of the Panjiakou Reservoir was established using EFDC, a general-purpose modeling package to simulate flow, transport, and biogeochemical processes in surface water systems, including rivers, lakes, estuaries, reservoirs, wetlands, and near-shore regions43,44. EFDC was originally developed at the Virginia Institute of Marine Science (VIMS) and the School of Marine Science in the College of William and Mary by Dr. John M. Hamrick in 1988. The code of EFDC is open, and it is recommended by the USEPA as a standard three-dimensional hydro-environmental simulation tool45,46. Oxygen is produced by photosynthesis of the phytoplankton group, whose photosynthetic rates depend on available light and nutrients (phosphate, nitrate, ammonium for the group). Oxygen consumption in the model depends on phytoplankton respiration, decaying dissolved and particulate organic matter (which are imported by inflows and produced through phytoplankton mortality), through nitrification of ammonia, and through sediment consumption. For more detailed information about the EFDC, readers are referred to the user manual (https://www.eemodelingsystem.com/).

The standard sigma grid used for the transformation of the vertical coordinate introduces a well-known error in the horizontal gradient terms, including concentration, velocity, and pressure47. In general, this error is significant only in regions with highly variable bathymetry. EFDC uses the sigma-zed (SGZ) coordinate, which means the vertical layering scheme has been modified to allow the number of layers to vary over the model domain based on the water depth. Consequently, each cell can have a different number of layers.

Model setup and input data

The boundary conditions for running the model included time series of meteorological data, hydrological data for inflows and outflows, water quality data, as well as the reservoir bathymetry describing the elevation–area–volume relationship. Meteorological data included daily atmospheric pressure, temperature, precipitation, evaporation, relative humidity, cloud cover, shortwave radiation, wind speed, and wind direction, obtained from the Panjiakou Meteorological Station (Longitude: 118°16′, Latitude: 40° 23′). Topography, daily inflow and outflow volumes, monthly water temperature, and water quality (including DO, total nitrogen, total phosphorus, ammonia–nitrogen, nitrate-nitrogen, nitrite-nitrogen, etc.) data were provided by the Panjiakou Reservoir Administration.

The model calculation range was from the area in front of the dam to the confluence of the Liu River and Luan River (Fig. 1). Considering the simulation requirements for floodplain hydrology and hydrodynamics and the calculation efficiency, a horizontal grid of 200 m × 200 m was used, with a total of 1911 grid cells. To determine the vertical layering, factors such as temperature stratification and reservoir characteristics need to be considered. Further, the model must be able to accurately simulate the DO changes in the metalimnion while also taking the model’s running time and simulation efficiency into account. The vertical discretization employing a 38-layer SGZ coordinate system (with 2 layers below the surface at 2.5 m spacing, and the remaining 36 layers at 1.5 m spacing) represents an optimized scheme determined through comprehensive consideration of reservoir thermal stratification characteristics, the requirement for accurately simulating dissolved oxygen (DO) dynamics within the metalimnion, model computational efficiency, and numerical stability, following multiple layer density sensitivity tests. Testing confirmed that this non-uniform spacing design (featuring relatively coarser spacing near the surface and finer spacing (1.5 m) within and below the metalimnion) provides sufficient resolution to accurately capture critical DO variation processes in the metalimnion while maintaining computational efficiency. The grid cross-section and longitudinal section are shown in Fig. 2. The simulation time step was 10 s, and the output frequency was daily. Since the initial simulation time is during the winter mixing period, a single value was used for initialization on the vertical cross-section.

Model calibration

The simulation period ranged from March 30, 2017, to December 31, 2017. This period was chosen because it had a significant MOM during the thermal stratification period, and high-quality thermal stratification and water quality monitoring data were available. The data used for model calibration were from a cross-section near the dam and included: daily water levels provided by the reservoir management; monthly temperature, DO, and Chlorophyll-a (Chla) from the surface to the bottom layer, measured with a multiparameter water quality monitor (YSI, EXO-1, USA). Model calibration was implemented in three steps. (1) Water balance: Deviations in the water budget could always be attributed to inaccurate input data of bathymetry, inflow, and outflow discharge. According to the water balance formula, an additional inflow was added to achieve water balance. (2) Temperature calibration: Thermal radiation processes, including solar shortwave radiation and atmospheric and water surface long-wave radiation are the primary components of a lake’s surface heat budget. Therefore, temperature calibration parameters included the background extinction coefficient and surface absorption of solar radiation minimum coefficient. (3) Water quality calibration: Since there are close to 200 water quality parameters in EFDC, instead of assessing uncertainty/sensitivity of all parameters, we selected parameters based on important ecological processes for this particular reservoir: (a) the dominant algal group in Panjiakou Reservoir during the early thermal stratification period was diatoms, (b) during the thermal stratification period, diatoms were mainly distributed in the epilimnion, (c) TC and total inorganic carbon (TIC) gradually increased with time in the metalimnion, and (d) bacteria were widespread in the metalimnion. After the death and sedimentation of diatoms in the epilimnion, they accumulated in the metalimnion, leading to increased TC concentrations, while bacterial degradation of algal-derived organic matter caused an increase in TIC concentrations in the metalimnion, consuming a significant amount of oxygen. Considering the dominance of diatoms in the epilimnion of the Panjiakou Reservoir, the parameterization of diatoms aggregating in the epilimnion was performed. Based on relevant literature, calibration was conducted for parameters such as growth rate, sedimentation rate, basal metabolic rate, predation rate, suitable temperature, and light conditions (Table 1).

The Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE), coefficient of determination (R2), and Nash–Sutcliffe efficiency (NSE) were used to evaluate the model performance. These coefficients are widely used to evaluate model performance48, and a smaller RMSE value indicates that the simulated values are closer to the measured values. The closer \({R}^{2}\) is to 1, the better the simulation effect. According to literature statistics49,50, when \({R}^{2}\ge 0.85\), the simulation effect is considered very good. When 0.85 > \({R}^{2}\) ≥ 0.60, the simulation effect is considered average; and when \({R}^{2}\)< 0.60, the simulation effect is considered poor. The closer the NSE is to 1, the higher the simulation accuracy. Based on previous experience, when NSE > 0.75, the simulation effect was considered very good. When 0.50 ≤ NSE ≤ 0.75, the simulation effect was considered satisfactory, and when NSE < 0.50, the simulation effect was considered poor.

Scenarios

Climate warming affects the thermal stratification structure of lakes and reservoirs, influencing biological processes and ecosystem structure, consequently affecting DO stratification and the MOM. Due to the intensification of the greenhouse effect, the global warming rate in the past 50 years has been twice that of the past 100 years. By the end of the twenty-first century, the temperature is expected to rise between 1.7 °C and 6.3 °C51. Between 2005 and 2017, the temperature in the Panjiakou Reservoir region increased at a rate of 0.07 °C /a (Fig. 3). Precipitation and wind speed, as key climate change factors with inherent significant regional uncertainties, will be evaluated for their impacts on dissolved oxygen (DO) in deep-water reservoirs in subsequent research.

To systematically analyze the impact of temperature rise on the reservoir’s DO, four scenarios were set up based on the temperatures from April to December 2017: a 2 °C decrease (Scenario S1), no change (Scenario S2), a 2 °C increase (Scenario S3), and a 4 °C increase (Scenario S4). In each scenario, all other model boundaries and parameters were kept unchanged except for the temperature.

First, we analyzed the impact of temperature increase on the thermal stratification structure using three indicators: thermal stratification stability, start and end times of thermal stratification, and metalimnion thickness. Next, we examine the effect of temperature increase on algal growth time and algal concentration based on Chla concentration. Finally, we explored the changes in metalimnion hypoxia with increasing temperature using two indicators, the start and end times of the MOM and MOM duration. The potential energy index (APE, Eq. 1) was chosen to evaluate the thermal stratification stability of the reservoir52, and the buoyancy frequency squared (N2, Eq. 2) was used as the criterion for identifying the metalimnion.

where APE is the potential energy index, J/m4; D is the total water depth, m; \(\rho\) is the water density at the corresponding depth, kg/m3; \({\rho }^{*}\) is the average water density, kg/m3; and g is the gravitational acceleration, m/s2.

where \(N^{2}\) is the buoyancy frequency squared, 1/s2; and \(\rho_{0}\) is the average water density, kg/m3. We defined the metalimnion as the depth range where \(N^{2}\) < -10–3/s2 (Kreling et al. 2017), and defined the epilimnion and hypolimnion and the layers above and below.

Results

Model performance and goodness of fit

The parameters used in the calibrated model are shown in Table 2. An additional distributed inflow with a small discharge (approximately 10% of the actual inflow on a yearly basis) was incorporated into the simulation to close the water budget. The RMSE was 0.3 m, R2 0.99, and NSE 0.99, indicating a high degree of agreement between the simulated and measured water levels. The comparison of simulated and measured water temperature results (RMSE < 1.6 °C, R2 > 0.97, NSE > 0.85) is shown in Figs. 4 and 5. The model adequately captured the dynamic changes of diatoms (as represented by Chla concentration; Fig. 6), with R2 and NSE both greater than 0.6 (Table 3). Although the simulated concentration was slightly higher than the measured one, it effectively reproduced the distribution of diatoms mainly in the epilimnion (1–10 m water depth) during the thermal stratification period. Under reduced-light conditions, there was less Chla with increasing depth. The model accurately predicted the DO dynamics (R2 and NSE both greater than 0.6), particularly the spatial and temporal distribution of MOM, which was consistent with the observed values (Figs. 7 and 8). The MOM formed in early July and disappeared in October as the DO stratification gradually receded. The location of MOM shifted downward following the metalimnion, with the minimum DO value dropping to 1 mg/L.

In summary, the error analysis results showed that the three-dimensional hydrodynamic and water quality model of the Panjiakou Reservoir constructed could accurately predict physical variables such as water level and water temperature, biological state variables such as diatoms, and chemical variables such as DO. Therefore, this model could be used to study the impact of increasing air temperature on the development of the MOM.

Impact of climate warming on thermal stratification structure

The vertical water temperature simulation results under different air temperatures are shown in Fig. 9. To compare the impact of air temperature increase on the water temperature of different layers, the water temperature results in the epilimnion, metalimnion, and hypolimnion were extracted separately, as shown in Fig. 10.

The water temperature in the epilimnion gradually increased with increasing air temperature. The water temperature trends were consistent in all scenarios, showing a pattern of first increasing and then decreasing over time. In April, the water temperature gradually increased from 4 °C, reaching its maximum by the end of July, and then gradually decreased. From April to May, the water temperature differences were relatively small between scenarios, with average differences of 1.07, 1.05, and 1.10 °C between S1 and S2, S2 and S3, S3 and S4, respectively. From June to December, the water temperature differences between scenarios were larger, with average differences of 1.43, 1.44, and 1.34 °C between scenarios S1 and S2, S2 and S3, S3 and S4, respectively.

The water temperature in the metalimnion also gradually increased with increasing air temperature. The water temperature trends were consistent among all scenarios, showing a pattern of first increasing and then decreasing over time. From April to July, the water temperature remained around 4 °C, while from August to October, the water temperature gradually increased and began to decrease from the end of October. From April to July, there was no significant difference in water temperature between scenarios. From August to October, the water temperature differences between scenarios were larger, with average differences of 1.16, 1.22, and 1.37 °C between scenarios S1 and S2, S2 and S3, S3 and S4, respectively.

The water temperature in the hypolimnion also gradually increased with increasing air temperature. The water temperature in S1 remained between 4 and 6 °C throughout the year, while in the other scenarios, the water temperature remained at 4 °C from April to August and gradually increased from September to December. The average temperature differences between S1 and S2, S2 and S3, S3 and S4 were 0.44, 1.01, and 1.75 °C, respectively.

The above results indicated that during the thermal stratification period, the impacts of air temperature increase on the water temperature of each layer in the reservoir differed. The epilimnetic water temperature increased with a relatively stable difference as air temperature rose, while the temperature differences between scenarios in the meta- and hypolimnion increased significantly with increasing air temperature. For example, for every 2 °C increase in air temperature, the epilimnion water temperature increased by about 1.1 °C from April to May and by about 1.4 °C from June to December, while the meta- and hypolimnetic water temperature difference increased from 1.16 to 1.37 °C and from 0.44 to 1.75 °C, respectively.

The impact of climate warming on DO

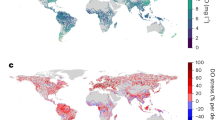

The vertical DO simulation results under different air temperatures are shown in Fig. 11. To quantitatively analyze the changes in DO concentration under different scenarios, DO concentrations were extracted from the epilimnion, metalimnion, and hypolimnion.

As shown in Fig. 12a, from April to May, the DO concentration in the epilimnion increased with increasing air temperature, while the DO concentration decreased with increasing air temperature in the remaining periods. The trends in DO concentration were consistent among all scenarios. From June to July, the DO concentration decreased rapidly and then remained between 8 and 10 mg/L. As the air temperature increased, the epilimnetic water temperature rose, and the solubility decreased, causing a decrease in DO concentration. The average DO concentration differences between S1 and S2, S2 and S3, S3 and S4 were 0.18, 0.20, and 0.23 mg/L, respectively.

As shown in Fig. 12b, the DO concentration in the metalimnion gradually decreased with increasing air temperature, and the trends were consistent among all scenarios. From April to September, the DO concentration decreased rapidly from 12 to 1 mg/L. From October to December, the DO concentration gradually increased as the thermal stratification structure receded and returned to 10 mg/L. The average DO concentration differences between S1 and S2, S2 and S3, S3 and S4 were 0.28, 0.22, and 0.21 mg/L, respectively.

As shown in Fig. 12c, the DO concentration in the hypolimnion gradually decreased with increasing air temperature, and the trends were the same among all scenarios. The DO concentration gradually decreased from 12 mg/L and approached 0 mg/L until the stratification ended, the water body mixed vertically, and the DO concentration recovered quickly. The differences in DO concentration between scenarios were larger in the later stage of stratification. The average DO concentration differences between S1 and S2, S2 and S3, S3 and S4 were 0.40, 0.35, and 0.25 mg/L, respectively.

Discussion

In this paper, we established a three-dimensional hydrodynamic water quality model of the Panjiakou Reservoir using EFDC and, for the first time, explored the impact of temperature rise on thermal stratification structure, DO stratification, and the MOM. The simulation results of various variables were in good agreement with the measured, and the RMSE of water temperature was lower than that of other recent studies53,54. In a meta-analysis, Arhonditsis and Brett55, compared the performance of different models, and the water temperature simulation accuracy in this study can be considered as high. In addition, the model accurately captured the dynamic changes of DO and diatoms, especially the spatiotemporal distribution of the MOM. The average R2 of DO was 0.7, which was close to the median R2 of 0.7 calculated for 569 oxygen simulations. Studies have shown that with the intensification of thermal stratification caused by climate warming, the concentration of organic matter in the hypolimnion is higher, leading to accelerated oxygen consumption and the formation of anaerobic conditions27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57. Research by Breitburg et al. shows that the global area of oxygen-depleted zones exceeds 245,000 km2, and the area of waters with dissolved oxygen concentrations below 0.5 mg/L exceeds 1.14 million km2, causing adverse effects on the ecological environment56.

At the beginning of thermal stratification, algae proliferate in large quantities in the epilimnion and then gradually die off. The decomposition of algal-derived particulate organic matter by microorganisms inevitably changes the vertical distribution of DO. The water quality monitoring data in front of the Panjiakou Reservoir dam showed that DO was positively correlated with water temperature, algae, and other aquatic variables in different periods (Table 4). To explore the impact of climate warming on DO dynamic structure, this paper first briefly analyzes the influence of physical structure and algal biochemical reactions on DO.

In general, the water temperature of the epilimnion in the Panjiakou Reservoir ranged from 4 to 30 °C, while the hypolimnetic water temperature ranged from 4 to 8 °C. The thermal stratification structure of the reservoir presented a pattern of mixing, formation, stabilization, and decline throughout the year. Mixing period: in April, the vertical water temperature distribution was uniform, ranging from 4 to 5 °C, with a small temperature gradient between the upper and lower layers. Formation period: as the air temperature rose, the bottom water temperature changed slightly due to a time lag and unevenness of heat transfer, and the thermal stratification of the reservoir gradually formed. The surface water temperature gradually increased due to solar radiation, with the epilimnion water temperature ranging from 8 to 22 °C during this period. The hypolimnion water temperature slightly increased, ranging from 4 to 6 °C. The metalimnion was 3 to 10 m water depth. Stabilization period: from July to September, the epilimnetic water temperature ranged from 22 to 30 °C, reaching its maximum of 30 °C in August. The hypolimnetic water temperature gradually increased, ranging from 4 to 8 °C. The metalimnion gradually moved downward, starting at 5 to 12 m water surface depth in early July and moving down to 12 to 22 m by the end of September. Decline period: beginning in October, the epilimnetic water temperature gradually decreased with the decline of air temperature, dropping to 12 °C by the end of November, while the hypolimnetic water temperature remained at 8 °C. The sinking of cold surface water intensified the vertical convection mixing, reducing the temperature difference between the upper and lower layers of the reservoir, and the thermal stratification gradually disappeared. By the end of December, the vertical water temperature was uniformly mixed at 6 °C.

Similar to the thermal stratification structure, the DO stratification also presented a pattern of mixing, formation, stabilization, and decline. Mixing period: from April to May, the DO concentration was greater than 10 mg/L, and water was DO saturated. Below a water depth of 10 m, the DO concentration is higher than 12 mg/L, showing a metalimnion DO maximum phenomenon. In May, the thermal stratification structure had already formed, indicating that the vertical DO stratification lagged behind the thermal stratification. Formation period: in June, the vertical DO stratification structure formed, with an epilimnetic DO concentration of 12 mg/L and a hypolimnetic DO concentration of 9–10 mg/L. The metalimnion DO gradually decreased with depth, ranging from 12 to 9 mg/L. Stabilization period: from July to September, the epilimnetic DO concentration was uniformly distributed at approximately 10 mg/L. Under the influence of sediment oxygen consumption, the DO concentration in the hypolimnion continuously and slowly decreased over time, ranging from 4 to 9 mg/L. In July, the metalimnetic DO concentration decreased and then increased with depth, dropping from 8 to 4 mg/L and then rising to 7 mg/L, presenting a minimum oxygen (MOM). The minimum DO value gradually decreased over time, reaching 1 mg/L during some periods in August and September. The location of the MOM was similar to that of the metalimnion and gradually declined over time. In early July, the MOM depth was 7.68 m, dropping to 19.75 m by the end of September. Decline period: from October to December, as the thermal stratification structure declined, the water body re-entered a vertical mixing state, and the vertical DO stratification gradually disappeared, with the MOM also gradually disappearing. Except for the lower DO concentration at the bottom of the reservoir, the DO concentration in other parts gradually recovered to 10 mg/L.

In summary, the high correlation between DO and water temperature in each month indicated that the formation of thermal stratification provided conditions for vertical DO stratification in terms of physical structure. The vertical temperature stratification caused changes in water density, and the density gradient in the metalimnion hindered the vertical transport of DO, leading to the formation of DO concentration gradients. At the beginning of thermal stratification, the correlation coefficient between DO and water temperature was lower than that during the stable stratification period, which was due to a lag in the oxygen stratification process compared to the evolution of thermal stratification. The stability of thermal stratification increased with rising temperature, and the increased vertical density gradient further restricted the vertical exchange of DO, leading to a decrease in metalimnetic DO and a decrease in MOM values.

The correlation between DO and Chla concentration was moderate in May and high from July to October (Table 4), indicating that the vertical distribution of DO was related to algae. Algal photosynthesis produces oxygen, respiration consumes oxygen, and oxygen consumption due to microbial decomposition after algal death affects the vertical distribution of DO. According to the vertical distribution of DO and Chla, algae were concentrated within 10 m water depth during the thermal stratification period. However, due to the gradual downward migration of the metalimnion over time, the algal distribution changed from the epilimnion and metalimnion in May to the epilimnion in September (Fig. 13). During the formation of thermal stratification in May, there was no stratification of DO. At this time, the metalimnion was located within the euphotic zone (within 11 m water depth), and algal photosynthesis produced more oxygen than was consumed by respiration, resulting in a maximum DO concentration in the metalimnion. The maximum Chla concentration corresponded to the location of the maximum DO concentration in the metalimnion. In July, algae were distributed in the epilimnion and metalimnion, and the Chla concentration increased compared to May. At this time, the metalimnion gradually moved below the euphotic zone (7.3 m), resulting in algal photosynthesis being lower than respiration in the metalimnion. The stable thermal stratification structure prevented timely replenishment of DO, leading to anoxic conditions in the metalimnion and the formation of the MOM. In September, algae were concentrated in the epilimnion, and the algal content in the metalimnion decreased (< 3 μg/L). This indicated that algal biological processes had changed the vertical distribution of DO to some extent.

During the thermal stratification period, TC and TIC tended to increase with the decrease of algal concentration in the metalimnion (Fig. 14). From July to September, the Chla concentration in the metalimnion decreased from 6 to below 3 μg/L, while the TC concentration increased by 9 mg/L and the TIC concentration increased by 8 mg/L. This indicated that dead algae from the epilimnion settled and accumulated in the metalimnion, leading to an increase in TC concentration. At the same time, the microbial degradation of algal-derived organic matter caused an increase in TIC concentration in the metalimnion, and the accompanying oxygen consumption resulted in anoxic conditions in the metalimnion and the appearance of the MOM. Kalff39, showed that the density of algal particles is close to that of freshwater, e.g., Microcystis particles with a diameter of about 100 μm having a density of 1010 kg/m3, the settling rate is relatively slow, which were 0.4 m/d and 0.2 m/d in the epilimnion and metalimnion, respectively. These rates depend on amongst others on particle size and water temperature, but if assume these rates are similar in Panjiakou Reservoir, it would take 40–50 days for algal particles to settle 10 m, and the rapid decomposition of algae can last about 20 days. During the formation of MOM in the Panjiakou Reservoir, the thickness of the metalimnion was generally about 10 m, providing sufficient time for algal-derived particulate organic matter to decompose and mineralize in the metalimnion. This process is accompanied by considerable oxygen consumption, leading to the formation of the MOM.

The above analysis discussed the effects of physical structure and algal biochemical reactions on the DO structure. Under the background of global warming, the physical structure and algae change, thereby altering the DO structure. Both the upper and lower interfaces of the metalimnion (Fig. 15) migrated downward in various scenarios in the Panjiakou Reservoir. The positions of the upper interface did not differ much between different scenarios. From May to June, the upper interface of the metalimnion was located at 3–5 m water depth, from July to August at 5–8 m, and in September, when the thermal stratification was about to enter the recession period, the upper interface varied greatly, ranging from 8 to 13 m water depth. The increase in air temperature affected the depth of the reservoir, causing the lower interface position to drop. With little difference in the upper interface position, the thickness of the metalimnion gradually increased.

The stability of thermal stratification gradually increased with rising air temperature (Fig. 16 and Table 5), in the order S4 > S3 > S2 > S1, with corresponding maximum APE index values of 2.39, 2.22, 2.01, and 1.82 J/m3, respectively. The trends of thermal stratification stability over time were consistent across all scenarios, reaching their maximum at the end of July and then gradually decreasing, which was in line with the annual cycle of mixing, formation, stabilization, and recession. Using an APE index value of 0.05 J/m3 as an indicator for the start and end of thermal stratification, the order of stratification onset was S4, S3, S2, and S1, with a difference of 5, 4, and 10 days between scenarios. The order of stratification end was S1, S2, S3, and S4, with differences of 1, 1, and 2 days between scenarios. The rise in air temperature led to an earlier formation of thermal stratification and an increase in the duration of stratification.

Changes in air temperature affect the community structure and primary productivity of phytoplankton in lakes and reservoirs. Under the background of global warming, the community structure of phytoplankton in freshwater lakes develops towards cyanobacteria dominance. Simulations have shown that an increase in air temperature leads to a rise in the temperature of the epilimnion, which can directly enhance the photosynthesis and respiration of algae, thereby increasing their growth rate and reproduction58. This shortens the time for algae to reach their peak, resulting in an earlier outbreak and increased severity of algal blooms. Compared to S1, the time for S4 to reach the same Chla concentration at 1-m depth underwater is about 10 days shorter (Fig. 17). The increase in algal concentration led to a higher concentration of algal-derived particulate organic matter sinking into the metalimnion, which in turn increased the oxygen consumption in the metalimnion.

Rising air temperatures increased water temperatures throughout the epilimnion, metalimnion, and hypolimnion, directly reducing dissolved oxygen (DO) levels. Concurrently, enhanced thermal stratification strengthened water column stability, and the resulting increase in vertical density gradient further restricted vertical DO exchange—both processes collectively depleting oxygen in the metalimnion. Due to the lack of oxygen exchange with the atmosphere in the metalimnion and hypolimnion, continuous respiration and the oxidation and decomposition of nutrients cause DO consumption to be greater than production, leading to the occurrence of hypoxia (DO ≤ 2 mg/L), and this phenomenon worsens with increasing air temperature. Hypoxia in the metalimnion can lead to the formation of a MOM. The value and location of the MOM in different scenarios are shown in the Figs. 18 and 19. In different scenarios, the DO concentration ranged between 6.5 and 8 mg/L in early June, and it dropped to below 1 mg/L from July to October. Increasing air temperatures cause the metalimnion to deepen, consequently resulting in the descent of the MOM, the minimum DO value showed a decreasing trend, the MOM occurred earlier, and its duration increased (Table 6).

Conclusions

In this study, we used EFDC to accurately simulate the evolution of thermal stratification and spatiotemporal distribution of DO in the Panjiakou Reservoir, an important urban water source in China. We analyzed the effects of physical structure and algal biochemical reactions on DO and explored the characteristics of DO changes under global warming. (1) The vertical distribution of water temperature in the Panjiakou Reservoir exhibited distinct seasonal characteristics, manifested as an annual cycle of mixing, formation, stabilization, and decline. The vertical stratification of DO presented a similar cycle but with a certain lag relative to thermal stratification. The MOM occurred during the stable period of thermal stratification. (2) During the metalimnetic period, dead algae from the epilimnion accumulated in the metalimnion, causing an increase in TC concentration. At the same time, the decomposition of algal-derived organic matter leads to an increase in TIC concentration in the metalimnion. The accompanying oxygen consumption is one of the reasons for hypoxia in the metalimnion. (3) An increase in air temperature made the reservoir stratification more stable to some extent. The formation of thermal stratification occurred earlier, the duration of stratification increased, and the thickness of the metalimnion increased. This caused a decrease in DO concentration in the epilimnion and hypolimnion, and the MOM formed earlier, lasted longer, its scale increased with increasing water temperature and algal concentration, and its position moved downward. The position of the MOM moved downward. By simulating and analyzing the Panjiakou Reservoir’s thermal stratification and DO dynamics, this study provided valuable insights into the effects of climate change on water quality. Future efforts could mitigate hypoxia risks in deep-water reservoirs through targeted measures such as stratified aeration and ecological operations to enhance oxygen flux.

Data availability

The data of this paper are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

References

Thomann, R. V. & Mueller, J. A. Principles of Surface Water Quality Modeling and Control 1st edn. (Prentice Hall, 1987).

Wetzel, R. G. Limnology, Lake and River Ecosystem 3rd edn. (Academic Press, 2001).

Arend, K. K. et al. Seasonal and interannual effects of hypoxia on fish habitat quality in central Lake Erie. Freshw. Biol. 56(2), 366–383 (2011).

Boehrer, B. & Schultze, M. Stratification of lakes. Rev. Geophys. 46(2), 1–27 (2008).

Rhodes, J. H. et al. Long-term development of hypolimnetic oxygen depletion rates in the large Lake Constance. Ambio 46(5), 554–565 (2017).

Terry, J. A. & Sadeghian, K. E. Modelling dissolved oxygen/sediment oxygen demand under ice in a shallow eutrophic prairie reservoir. Water 9(2), 131 (2017).

Zhang, Y. et al. Dissolved oxygen stratification and response to thermal structure and long-term climate change in a large and deep subtropical reservoir (Lake Qiandaohu, China). Water Res. 75, 249–258 (2015).

North, R. P. et al. Long-term changes in hypoxia and soluble reactive phosphorus in the hypolimnion of a large temperate lake: Consequences of a climate regime shift. Glob. Change Biol. 20(3), 811–823 (2014).

Jansen, J. et al. Climate-driven deoxygenation of northern lakes. Nat. Clim. Chang. 14, 832–838 (2025).

Hutchinson, G. On the relation between the oxygen deficit and the productivity and typology of lakes. Int. Rev. Gesamten Hydrobiologie Hydrographie 36, 336–355 (1938).

Livingstone, D. M. & Imboden, D. M. The prediction of hypolimnetic oxygen profiles: A plea for a deductive approach. Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 53, 924–932 (1996).

Weber, M. et al. Optimizing withdrawal from drinking water reservoirs to reduce downstream temperature pollution and reservoir hypoxia. J. Environ. Manage. 197, 96–105 (2017).

Shapiro, J. The cause of a metalimnetic minimum of dissolved oxygen. Limnol. Oceanogr. 5(2), 216–227 (1960).

Burke, T. A. The Limnetic Zooplankton Community of Boulder Basin, Lake Mead in Relation to the Metalimnetic Oxygen Minimum (University of Nevada, Las Vegas, 1977).

Bolke E. L. Dissolved oxygen depletion and other effects of storing water in Flaming Gorge Reservoir, Wyoming and Utah. US Dept. of the Interior, Geological Survey: for sale by the Supt. of Docs (1979).

Nix, J. Contribution of hypolimnetic water on metalimnetic dissolved oxygen minima in a reservoir. Water Resour. Res. 17(2), 329–332 (1981).

Schram, M. D. & Marzolf, G. R. Metalimnetic oxygen depletion: Organic-carbon flux and crustacean zooplankton distribution in a quarry embayment. Trans. Am. Microsc. Soc. 113(2), 105–116 (1994).

Wentzky, V. C. et al. Metalimnetic oxygen minimum and the presence of Planktothrix rubescens in a low-nutrient drinking water reservoir. Water Res. 148(2019), 208–218 (2019).

Mi, C. X. et al. The formation of a metalimnetic oxygen minimum exemplifies how ecosystem dynamics shape biogeochemical processes: A modelling study. Water Res. 175(15), 1–14 (2020).

Wang, R. et al. The apoptosis of Chlorella vulgaris and the release of intracellular organic matter under metalimnetic oxygen minimum conditions. Sci. Total Environ. 907(000), 1–10 (2024).

Han, J. et al. Change of algal organic matter under different dissolved oxygen and pressure conditions and its related disinfection by-products formation potential in metalimnetic oxygen minimum. Water Res. 226, 119216 (2022).

Kreling, J. et al. The importance of physical transport and oxygen consumption for the development of a metalimnetic oxygen minimum in a lake. Limnol. Oceanogr. 62(1), 1–16 (2017).

Gerling, A. B. et al. First report of the successful operation of a side stream supersaturation hypolimnetic oxygenation system in a eutrophic, shallow reservoir. Water Res. 67, 129–143 (2014).

Chen, S. Y. et al. A coupled three-dimensional hydrodynamic model for predicting hypolimnetic oxygenation and epilimnetic mixing in a shallow eutrophic reservoir. Water Resour. Res. 53(1), 470–484 (2017).

Chen, S. Y. et al. Three-dimensional effects of artificial mixing in a shallow drinking-water reservoir. Water Resour. Res. 54(1), 425–441 (2018).

Joehnk, K. D. & Umlauf, L. Modelling the metalimnetic oxygen minimum in a medium sized alpine lake. Ecol. Model. 136(1), 67–80 (2001).

Livingstone, D. M. Impact of secular climate change on the thermal structure of a large temperate central European lake. Clim. Change 57(1/2), 205–225 (2003).

You, G. et al. Observed air /soil temperature trends in open land and understory of a subtropical mountain forest, SW China. Int. J. Climatol. 33(5), 1308–1316 (2013).

Wu, T. et al. Recent ground surface warming and its effects on permafrost on the central Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. Int. J. Climatol. 33(4), 920–930 (2013).

Arhonditsis, G. B. et al. Effects of climatic variability on the thermal properties of Lake Washington. Limnol. Oceanogr. 49(1), 256–270 (2004).

Zhang, Y. L. et al. Monitoring and analysis of thermodynamics in Tianmuhu Lake. Adv. Water Sci. 15(1), 61–67 (2004).

Wu, Z. X. et al. Vertical distribution of phytoplankton and physico-chemical characteristics in the lacustrine zone of Xin’anjiang Reservoir (Lake Qiandao) in subtropic China during summer stratification. J. Lake Sci. 24(3), 460–465 (2012).

Kraemer, B. M. et al. Morphometry and average temperature affect lake stratification responses to climate change. Geophys. Res. Lett. 42(12), 4981–4988 (2015).

Sahoo, G. & Schladow, S. Impacts of climate change on lakes and reservoirs dynamics and restoration policies. Sustain. Sci. 3(2), 189–199 (2008).

O’Reilly, C. M. et al. Climate change decreases aquatic ecosystem productivity in Lake Tanganyika. Afr. Nat. 424(6950), 766–768 (2003).

Verburg, P., Hecky, R. E. & Kling, H. Ecological consequences of a century of warming in Lake Tanganyika. Science 301(5632), 505–507 (2003).

Marshall, B. et al. Has climate change disrupted stratification patterns in Lake Victoria. Afr. J. Aquat. Sci. 38(3), 249–253 (2013).

Mahere, T. et al. Climate change impact on the limnology of Lake Kariba, Zambia-Zimbabwe. Afr. J. Aquat. Sci. 39(2), 215–221 (2014).

Kalff, J. Limnology: Inland Water Ecosystems (Prentice Hall, 2002).

Jane, S. F. et al. Widespread deoxygenation of temperate lakes. Nature 594(7861), 66–70 (2021).

Jankowski, T. et al. Consequences of the 2003 European heat wave for lake temperature Profiles, thermal stability, and hypolimnetic oxygen depletion: Implications for a warmer world. Limnol. Oceanogr. 51(2), 815–819 (2006).

Wilhelm, S. & Adrian, R. Impact of summer warming on the thermal characteristics of a polymictic lake and consequences for oxygen, nutrients and phytoplankton. Freshw. Biol. 53(2), 226–237 (2008).

Chen, F. et al. The importance of the wind-drag coefficient parameterization for hydrodynamic modeling of a large shallow lake. Ecol. Inform. 59, 101106 (2020).

Huang, A. P. et al. Spatiotemporal characteristics, influencing factors and evolution laws of water exchange capacity of Poyang Lake. J. Hydrol. 609, 1–11 (2022).

Kim, J., Lee, T. & Seo, D. Algal bloom prediction of the lower Han River, Korea using the EFDC hydrodynamic and water quality model. Ecol. Modell. 366, 27–36 (2017).

Luo, X. & Li, X. Y. Using the EFDC model to evaluate the risks of eutrophication in an urban constructed pond from different water supply strategies. Ecol. Modell. 372, 1–11 (2018).

Mellor, G. L. & Blumberg, A. F. Modeling vertical and horizontal diffusivities with the sigma coordinate system. Mly. Weather Rev. 20, 851–875 (1985).

Carraro, E. N., Guyennon, D., Hamilton, L., et al. Coupling high-resolution measurements to a three-dimensional lake model to assess the spatial and temporal dynamics of the cyanobacterium Planktothrix rubescens in a medium-sized lake Hydrobiologia. Springer, 77–95 (2012).

Parajuli, P. B., Jayakody, P. & Ouyang, Y. Evaluation of using remote sensing evapotranspiration data in SWAT. Water Resour. Manag. 32(3), 985–996 (2018).

Ma, B. et al. Simulating the water environmental capacity of a seasonal river using a combined watershed-water quality model. Earth Space Sci. 7(11), 1–17 (2020).

IPCC. Working Group I Contribution to the IPCC Fifth Assessment report, Climate Change 2013: the Physicalsciencebasis: Summary for Policymakers (Cambridge University Press, 2013).

Kumagai, M. et al. Effect of cyanobacterial blooms on thermal stratification. Limnology 1(3), 191–195 (2000).

Chong, S. C., Park, K. & Lee, A.-G. Modeling summer hypoxia spatial distribution and fish habitat volume in artificial estuarine waterway. Water 10(11), 1695 (2018).

Lee, R. M., Biggs, T. W. & Fang, X. Thermal and hydrodynamic changes under a warmer climate in a variably stratified hypereutrophic reservoir. Water 10(9), 1284 (2018).

Arhonditsis, G. B. & Brett, M. T. Evaluation of the current state of mechanistic aquatic biogeochemical modeling. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 271, 13–26 (2004).

Breitburg, D. et al. Declining oxygen in the global ocean and coastal waters. Science 359(6371), eaam7240 (2018).

Komatsu, E., Fukushima, T. & Harasawa, H. A modeling approach to forecast the effect of long-term climate change on lake water quality. Ecol. Model. 209(2/3/4), 351–366 (2007).

Patrick, R. The effects of increasing light and temperature on the structure of diatom communities. Limnol. Oceanogr. 16(2), 405–421 (1971).

Funding

The authors acknowledge the support from the National Key R&D Program of China (No. 2022YFC3204000);. National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 52309108). The Basic Scientific Research Expense Project of IWHR (No.WE110145B0052025)

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M wrote the main manuscript text; D,P, and L conceived and designed the framework ; H conducted data analysis ; All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Consent to participate

All authors agreed with the content and all gave explicit consent to submit before the paper is submitted.

Consent to publish

Upon acceptance, all authors agreed to publish the paper under the journal publishing agreements.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ma, B., Dong, F., Peng, W. et al. Dynamics of oxygen evolution in a thermally stratified reservoir under climate warming. Sci Rep 15, 40419 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-13432-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-13432-2