Abstract

This study examines the impact of puffing drying on the physicochemical and structural properties of apple slices using multispectral imaging (UV-NIR spectroscopy), FTIR spectroscopy, and chemometric analysis. Puffing drying significantly impacted apple slice quality, reducing lightness (L* from 75.00 to 43.62) and moisture content (from 10.34 to 7.41%), while increasing redness (a* from 5.41 to 12.32), acidity (from 0.37 to 0.49%), and hardness (from 422.06 to 2967.06). Despite enhanced texture, total phenolic content decreased from 3650.03 to 3307.28 mg GAE/kg, indicating some loss of nutritional compounds during processing. FTIR analysis revealed structural modifications in carbohydrates and lipids, while total phenolic content decreased, indicating thermal degradation. PCA distinguished control and puffed-dried samples, with the first principal component accounting for 98.5% of total variability. PLS regression effectively predicted lightness, redness, and hardness using FTIR spectral data. Multispectral imaging confirmed notable color and texture differences, with reduced lightness and increased surface heterogeneity. PCA of UV-NIR spectra further separated the sample groups, confirming compositional changes. These findings highlighted the potential of multispectral imaging as a non-destructive tool for monitoring drying-induced transformations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Apple has a wide range of applications in the food industry and remains a strong consumer favorite. In 2020, global apple production reached 86,442,716 tons, harvested from 4,622,366 hectares of orchards1. According to TUIK, Türkiye’s total apple production was 4,817,500 tons in 2022, while this amount decreased to 4,602,517 tons in 20232. Apples can be enjoyed in various forms, including dried fruit, juice, jam, or marmalade3,4. Regular apple consumption helps prevent neurodegenerative diseases and lowers the risk of asthma5,6,7,8.

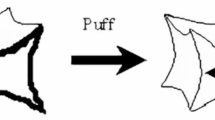

Apples can be consumed fresh or as dried chips. Reducing their moisture content by drying processes can significantly extend their shelf life while maintaining quality9,10,11. While drying offers substantial benefits for processing and storing food products, the use of inappropriate methods—such as excessively high temperatures, prolonged drying durations, or insufficient control of process parameters—can degrade the quality of the final product, lead to excessive energy consumption, and increase production costs12,13. Currently, the main technologies used for drying apple slices include hot air drying, vacuum freeze drying, microwave drying, and infrared drying14,15,16,17. Various processing techniques, including drying, frying, puffing, and cooking, are widely utilized to enhance food shelf stability and develop innovative products18,19. However, each technique has its own advantages and challenges. For instance, conventional hot-air drying is an efficient and cost-effective method but often leads to significant nutrient loss and textural changes due to prolonged exposure to high temperatures. Freeze-drying, on the other hand, is considered a gentle method that preserves heat-sensitive compounds and retains structural integrity, yet it is energy-intensive and costly. Frying enhances flavor and texture but introduces high oil absorption, reducing the overall healthiness of the product. Puffing drying, particularly when combined with pre-treatments like ultrasound, has the potential to improve texture and rehydration properties while minimizing excessive thermal degradation. Understanding these trade-offs is essential for optimizing processing conditions to achieve the best balance between quality retention and process efficiency20. A range of innovative technologies, such as ionizing irradiation21 high hydrostatic pressure22 pulsed electric fields23 and cold plasma24 have been explored primarily as pre-treatments to enhance drying efficiency and improve the quality of dried products. These methods can modify the structural, chemical, or microbial properties of food before drying, thereby influencing drying kinetics and the final product characteristics. However, they are not standalone drying technologies but rather complementary techniques used to optimize conventional drying methods. Apart from these, explosion puffing (EP), also known as instant controlled pressure drop texturing—has emerged as a promising approach for processing various foods25,26. EP has been widely adopted in food processing, with drying being one of its primary applications. Traditional drying methods typically result in slow drying rates and significant energy use, which can cause color deterioration and nutrient depletion due to prolonged heat exposure27. In contrast, EP drying creates a porous structure, providing a crispy texture and improved rehydration properties28,29. In recent years, there have been several attempts to develop a multispectral imaging system to simultaneously estimate several spoilage parameters and determine the quality parameters of some foods30,31. Moreover, investigations on the quality characteristics and microstructures of apples, mangoes, purple sweet potatoes, and potatoes using different tools such as hyperspectral imaging, laser light backscatter imaging during drying have been reported in the literature11,32,33,34. However, existing research lacks comprehensive integration of multispectral imaging with advanced statistical modeling for predicting key quality attributes in dried fruit products. Additionally, while FTIR spectroscopy has been widely used to assess chemical composition, its potential for capturing microstructural and functional changes in dried apples remains underexplored. There is also a need for optimized processing conditions that balance nutritional retention with desirable texture properties. Addressing these gaps, this study aims to combine FTIR spectroscopy and multispectral imaging with chemometric analysis to provide a more precise evaluation of puffing-dried apples, offering novel insights into their physicochemical and bioactive properties. This study provided valuable insights into how puffing drying affects the quality, composition, and structure of apple slices. Integrating multispectral imaging, FTIR spectroscopy, and chemometric analysis demonstrated a comprehensive and non-destructive approach to monitoring drying-induced changes. The findings highlighted significant alterations in color, texture, moisture, and chemical composition, particularly in carbohydrates, lipids, and phenolic compounds, due to different drying techniques. The potential use of PCA and PLS regression to predict quality attributes accurately by using spectral data.

Results and discussion

Physicochemical analysis

Table 1 presents the physicochemical results of the control and PD samples. The puffing-drying method significantly influenced the physicochemical properties of apple slices. The L* (lightness) value of PD (43.62 ± 6.98) was significantly lower than the control samples (75.00 ± 2.76). This indicates that PD apples experienced more browning during processing, likely due to Maillard reactions induced by rapid temperatures and pressure fluctuations, as well as enzymatic browning occurring before inactivation of polyphenol oxidase during drying. Similarly, the a* (redness) value increased significantly in PD apples (12.32 ± 1.75) compared to the control (5.41 ± 1.35), possibly due to the formation of brown pigments via Maillard reactions and caramelization under puffing drying conditions. Conversely, the b* value, associated with yellowness, decreased in PD apples (32.55 ± 3.81) compared to the control (37.73 ± 2.97). This reduction in b* value may be due to the thermal degradation of yellow pigments such as carotenoids, as well as structural changes in the tissue that affect light scattering and color perception.

The moisture content of the PD samples (7.41 ± 1.29%) was significantly lower than the control (10.34 ± 0.07%), suggesting effective moisture removal during puffing. However, the water activity (aw) of PD samples (0.31 ± 0.009) was slightly higher than the control (0.28 ± 0.003), which may indicate differences in water-binding capacity due to structural changes.

The titratable acidity (expressed as malic acid) and pH of PD apples were significantly higher (0.49 ± 0.08% and 4.83 ± 0.25, respectively) compared to the control (0.37 ± 0.01% and 4.52 ± 0.02) (p ≤ 0.05). This increase may be attributed to the concentration effect caused by moisture loss and potential chemical modifications, such as acid release or changes in buffering capacity, during the puffing process.

Similarly, the soluble solid content (°Brix) was slightly higher in the PD samples (12.45 ± 0.16 °Bx) compared to the control (12.20 ± 0.09 °Bx), likely due to the concentration of sugars as a result of water removal. These findings align with previous studies on PD fruits, where moisture reduction led to an increase in titratable acidity and °Brix values28.

The total phenolic content was lower in PD samples (3307.28 ± 180.75 mg GAE/kg) compared to the control (3650.03 ± 85.50 mg GAE/kg), suggesting that thermal and pressure treatments during puffing may degrade phenolic compounds.

Hardness was significantly (7 times) higher in PD samples (2967.06 ± 304.61) compared to the control (422.06 ± 26.98), indicating a more rigid texture likely due to structural modifications during puffing. However, the fracturability values of both treatments were not significantly different, suggesting comparable breakage behavior.

FTIR analysis

FTIR spectra of the samples were shown in Fig. 1. Functional band regions and assigned bands were summarized for dried apple samples in the Table 2. The broadband (3291 cm− 1) in this region represented hydroxyl groups in both the control and puffed dried samples. Puffing drying resulted in a lower peak intensity compared to the control group, indicating a rearrangement of structural bonds due to the effect of the drying method. The bands at 2920 and 2850 cm− 1, typically associated with methyl and methylene groups, suggest structural modifications in lipids and carbohydrates due to the thermal processing35,36. The slight decrease in peak intensities compared to the control group reflects the disruption of carbon chains. The peak at 1736 cm− 1, representing ester or carbonyl groups linked to lipids and pectin-like compounds37decreased in PD samples. The bands at 1598 and 1411 cm− 1, associated with phenolic compounds and acids, showed altered peak intensities, suggesting partial degradation of polyphenols or organic acids due to the rapid temperature and pressure changes of puffing drying. Furthermore, the peaks at 1239 and 1145 cm− 1, related to carbohydrate structures38exhibited changes, supporting the idea that puffing drying alters carbohydrate composition and molecular arrangements. The peak at 1025 cm− 1 serves as further evidence of modifications in the chemical bonds of carbohydrates during puffing drying. The peak at 1025 cm− 1 can be considered as an indication of changes in the chemical bonds associated with carbohydrate structures during puffing drying. These regions (918, 865, 816, and 776 cm− 1) are associated with amorphous structures or crystalline forms. The bands observed between 1200 and 800 cm− 1 come from the combination of stretching vibrations of C–O, C–C, C–O–H, and bending of C–O–H of carbohydrate absorption39. The pressure and temperature during puffing drying could have led to microstructural alterations in the apple slices, as reflected by changes in these bands. Similarly, the bands in the fingerprint region were successfully used to identify carbohydrates and phenolic compounds to determine the effect of the process in fresh and freeze-dried apple samples40.

The PCA score plot shows a clear distinction between the control and puffed-dried apple samples based on their FTIR spectra. The Eigen analysis of the correlation matrix highlights that PC1 accounts for 92.40% of the total variation, and PC2 adds an additional 6.10%, cumulatively explaining 98.50% of the variability in the dataset. This indicates that the primary variance in the spectral data is dominated by differences induced by the drying process. The drying process substantially alters the chemical and structural attributes of the apple slices, with puffing drying resulting in significant microstructural and compositional changes, as observed in the FTIR spectra (Fig. 1). The PCA indicates that FTIR spectra provide robust differentiation and that PC1 primarily represents moisture reduction and associated chemical rearrangements.

The PLS analysis (Table 3) establishes predictive models for key physicochemical properties using FTIR spectral data. The results reveal strong predictive relationships for most properties, particularly lightness (L*), redness (a*), and hardness, with varying degrees of correlation for other parameters. The PCA and PLS analyses corroborate the FTIR-based characterization of apple slices subjected to puffing drying. The PCA results confirm distinct compositional and structural shifts between the control and PD apple slices, emphasizing differences in moisture content, texture, and color attributes (Fig. 2). Additionally, the PLS models effectively predicted key quality parameters such as color (L, a*, b*), texture (firmness), and moisture content, demonstrating the potential of spectral data in monitoring and optimizing drying conditions. Similar leave-one-out PLS models were successfully developed for the prediction of soluble matters, such as sugars, acids, and phenolic compounds, in the different apple samples40. Moreover, PLSR models have been successfully used to quantify titrable acidity, pH, total phenolic content, and antioxidant levels in sun or oven-dried fruit leathers from apples41.

Multispectral imaging

The average spectral data (Fig. 3) indicated noticeable differences in mean intensity between the control and puffing dried apple samples in the UV-NIR region. These differences reflected changes in chemical and physical properties induced by the puffing drying process. In the UV–Vis region (360–700 nm), the control samples exhibited higher mean intensity compared to the PD samples. This could be that puffing drying resulted in the degradation or transformation of light-absorbing compounds such as polyphenols, and other pigments which were known to absorb in the UV-Vis region and sensitive to heat or mechanical stress during drying. In the transition region (650–750 nm), the difference in intensity between the two treatments were less, so structural or chemical changes were minimal. In the NIR region (750–960 nm), PD samples showed slightly higher mean intensity than the control. The NIR region was often associated with combination bands of O–H, C–H, and N–H bonds. The increased reflectance in this region was related to moisture loss, microstructural changes, or alterations in carbohydrate and protein content due to puffing drying. The higher intensity in PD samples could also reflect increased light scattering caused by porous structures formed during puffing drying42. Multispectral imaging (Fig. 4) revealed noticeable differences in color and surface texture of control and PD apple slices, confirming the visual impact of structural and compositional changes induced by the drying process.

The PCA score plot (Fig. 5) of the UV-NIR spectral data further emphasized the clear separation between the two sample groups, suggesting substantial structural and compositional modifications. The strong loadings associated with color-related spectral regions indicate significant pigment alterations, likely due to Maillard reactions and caramelization.

The PLS regression results (Table 4) demonstrated high predictive accuracy for L* (RCV = 0.90448) and a* (RCV = 0.86380), supporting the effectiveness of multispectral imaging in assessing color changes. Hardness exhibited one of the highest predictive correlations (RCV = 0.95382), confirming the structural transformations induced by puffing drying. Moisture content and water activity were also well predicted (RCV = 0.83057 and RCV = 0.87611, respectively), reflecting the drying efficiency. However, parameters such as pH and titratable acidity showed relatively lower predictive power (RCV < 0.52), likely due to their weaker spectral signatures in the measured range. These attributes may not exhibit strong absorbance in the spectral regions analyzed, leading to limited model accuracy. Despite these limitations, the integration of spectral analysis with multivariate modeling remains a valuable approach for non-destructive quality assessment in food processing. While it performs well for predicting parameters strongly associated with structural and compositional changes (e.g., color, texture, and moisture content), its accuracy for pH and acidity measurements may require complementary techniques such as direct chemical analysis or extended spectral range coverage to enhance predictive performance.

Conclusion

The study demonstrated that the puffing drying method significantly influences the physicochemical, structural, and compositional properties of apple slices. Puffing drying resulted in increased textural attributes such as hardness and color properties such as redness, along with reduced moisture content, compared to the control samples. However, it also led to the browning and degradation of phenolic compounds, likely due to thermal and pressure effects during processing. FTIR spectroscopy revealed clear structural modifications, particularly in carbohydrates and lipids, and a decline in total phenolic content, indicating thermal degradation. PCA analysis further confirmed the marked differences between control and puffed-dried samples, with PC1 capturing most of the variability. PLS models effectively predicted key quality parameters, emphasizing the utility of FTIR data for monitoring drying-induced changes. Collectively, these findings underscore the potential of puffing drying to enhance certain textural and color properties of apple slices while also highlighting the importance of optimizing process conditions to mitigate nutrient losses and maintain desirable product quality. Multispectral imaging and UV-NIR spectroscopy, combined with chemometric techniques, effectively captured the physicochemical changes, confirming reduced lightness and increased heterogeneity in apple slices subjected to puffing drying. PCA successfully differentiated control and puffed samples, while PLS regression provided robust predictive models for key quality attributes such as color, moisture content, and hardness. Chemometric analysis, including PCA and PLS regression, successfully distinguished between control and treated samples and accurately predicted the quality parameters from spectral data. To the best of our knowledge, this was the first report to integrate FTIR spectroscopy and multispectral imaging with chemometric analysis to comprehensively assess microstructural and functional changes in puffed-dried apple slices. However, this study showed that spectral imaging, such as FTIR without any imaging techniques, did not always provide sufficient information to fully determine various quality parameters in puffed-dried apples. These results highlighted the use of multispectral imaging, supported by chemometric tools, as a powerful, non-invasive method for evaluating quality in dried fruit processing. This methodology could be further developed for real-time, in-line quality control during food processing. With proper optimization, such spectral and imaging technologies may enable faster, more efficient monitoring across various dried fruit products, contributing to improved consistency, safety, and consumer acceptance in industrial applications. Future studies should focus on combined use of imaging and spectral techniques to further improve the predictive accuracy of chemical parameters and textural properties.

Materials and methods

Materials

In this study, apples, commonly produced in the Niğde region and cultivated in various areas, have been used as the drying material. The Red Chief (Malus domestica Borkh.) variety, which is widely grown in Niğde, has been sourced from the Faculty of Agricultural Sciences and Technologies at Niğde Ömer Halisdemir University and stored at + 4 °C in the Food Engineering Laboratories of the university.

Methods

Drying

Apples were washed with tap water to remove surface contaminants, then sliced into 3 mm-thick pieces. The sliced apples were then placed in an ultrasonic bath (Kudos, China) operating at 37 kHz frequency and 100% ultrasonic power in pure water at room temperature for 30 min to preserve color, increase dehydration rate, increase hardness, and crispness. The samples were filtered using a food strainer, gently dried with a paper towel, and then subjected to a preliminary drying step. In this step, apple slices were dried in a hot air oven (Isotex, Türkiye) at 70 °C until their moisture content was reduced to 40%, which took approximately 6–7 h. Afterward, the pre-dried apple slices were puffed using the puffing drying method at 50 °C for 10 min under a pressure of 5 bar. The parameters used in puffing drying were optimized before (data not shown). Finally, the puffed apples underwent a second drying step in a hot air oven at 70 °C until the moisture content reached 10%, which took approximately 1–2 h. Apples that were dried solely in a hot air oven at 70 °C up to 12 h, without any prior treatment, served as the control group.

Physicochemical analysis

The dried apple samples were finely ground (Lavion, Türkiye), and 0.5 g of the resulting powder was mixed with 20 mL of distilled water. The mixtures were allowed to equilibrate at 20 °C for one hour to ensure uniform temperature distribution and stabilization before analysis. For titratable acidity determination, the solutions were titrated with 0.1 M NaOH until the pH reached 8.1, using a pH meter (Hanna Instruments, Italy). The acidity was expressed as grams of malic acid per 100 g of dry sample. After sample preparation, the pH values of the samples were measured with a pH meter (Hanna Instruments, Italy). The water-soluble dry basis content of the samples was determined by ABBE refractometer (A.Krüssoptronic Gmbh AR4, Germany) at room temperature. The results were expressed in degrees brix (°Bx). The moisture content of the samples was determined using the standard gravimetric method by drying in an oven at 105 °C for 24 h. The results were expressed on a dry basis43. Water activities (aw) of control and dried apple samples were determined at room temperature using a water activity analyzer (AXIS, Türkiye). The color values of the control and puffing-dried (PD) samples were determined with a colorimeter (Konica Minolta CR400, Japan) according to the CIELab color scale and 3 measurements were taken from different regions of each sample. Total phenolic content (TPC) was determined according to the Folin-Ciocaltaeu method44. Phenolic compounds were extracted from the samples using an 80% methanol solution containing 1% HCl. The mixture was shaken at 40 rpm for 4 h and then centrifuged (Nüve NR 800R model, Türkiye) at 9000 g at 4 °C for 15 min to separate the clear fraction. For analysis, 0.75 mL of Folin-Ciocalteu reagent (10% in water) was added to 100 µL of the sample and left at room temperature for 5 min. Subsequently, 0.75 mL of Na₂CO₃ solution (75 g/L in water) was added and mixed thoroughly. The mixture was kept at room temperature in the dark for 1 h, followed by measurement of the absorbance at 725 nm. The same protocol was followed for gallic acid solutions of varying concentrations to construct a calibration curve. The absorbance values of the extracts were compared against the calibration curve, and the TPC was expressed as gallic acid equivalent (mg GAE/kg)45. Texture analysis was conducted using a TA-XT Texture Analyzer (Stable Micro Systems, UK) equipped with a P/0.25 spherical tip designed for dry fruits. The pre-test speed, post-test speed, test speed, and strain were set at 3 mm/s, 10 mm/s, 3 mm/s, and 40%, respectively. Hardness and fracturability values were measured during the penetration test46.

FTIR spectroscopy

Both control and PD samples were freeze-dried in a freeze dryer (Scanvac Coolsafe 95–15 Pro, Denmark) to prevent the functional bands from being closed by the water band remaining in the samples or absorbed by the samples after drying, and then powdered. The absorption spectra of the samples were obtained in the 400–4000 cm− 1 region using FTIR spectroscopy (Bruker, Germany) with an ATR cell and 128 scans at 2 cm− 1 resolution. Raw spectra were vector normalized for further analysis using the appropriate program (OPUS, v.8.1, Bruker Optics, Germany).

Multispectral imaging

Multispectral imaging (MSI) of the samples was conducted using a VideometerLab system (Videometer A/S, Hørsholm, Denmark). This system operates across 18 discrete wavelengths (375, 405, 435, 450, 470, 505, 525, 570, 590, 630, 645, 660, 700, 850, 870, 890, 940, and 970 nm), covering the visible to near-infrared (NIR) spectrum. The samples were placed inside a custom-designed integrating sphere coated with matte titanium paint to ensure uniform light distribution. A digital camera equipped with a monochrome charge-coupled device (CCD) sensor was positioned above the sphere to capture surface reflectance data. Light-emitting diodes (LEDs) arranged along the sphere’s rim provided narrowband spectral illumination, optimizing dynamic range while minimizing gloss artifacts, shadows, and specular reflections. Each LED strobe generated a monochromatic image with 32-bit floating-point precision and a spatial resolution of 2056 × 2056 pixels.

Regions of interest (ROI) segmentation was performed by exploiting the spectral differences between the various components of the sample. Following the segmentation process, spectral data were extracted through computer processing, which involved identifying and isolating spectral features from the segmented images. During segmentation, the sample was transformed into a segmented image, with a single, flat section of the apple selected as the primary ROI for spectral data collection. This approach ensured accurate and focused analysis of the sample’s key characteristics.

Chemometric analysis

Principal component analysis (PCA) and partial least squares (PLS) regression analyses were performed using Minitab 18 (Minitab Inc.). PCA was used to differentiate control and PD samples, and the results were presented as score plots. Total acidity, pH, water-soluble dry basis content, moisture content, color, and TPC of PD samples were estimated by PLS regression using FTIR spectral data and multispectral data. The spectral data were used as predictor variables (X), while the measured (color, moisture, water activity, titratable acidity, pH, °Brix, total phenolic content, hardness) served as the response variables (Y) in the development of Partial Least Squares (PLS) models. The PLS models were constructed to establish predictive relationships between spectral data and the analytical results, following the methodology outlined in previous studies47. Model performance was evaluated using cross-validation and statistical parameters such as the coefficient of determination (R²) and root mean square error (RMSE). Cross-validation (leave-one-out) was applied in all analyses to evaluate the calibration models, ensuring their robustness and ability to generalize effectively.

Statistical analysis

The statistical evaluation of the data obtained from the PD samples was obtained by comparing the differences between the means of the analysis results according to the treatments. The analysis was conducted using the Minitab Statistical Program (version 17, Minitab Inc., State College, PA, USA), and the Tukey multiple comparison test was performed to assess statistical differences between the means (p ≤ 0.05).

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

FAO. Crops and livestock products. https://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data/QCL (2022).

TUIK. TurkStat, Crop Production Statistics, 2023. https://data.tuik.gov.tr/Bulten/Index?p=Bitkisel-Uretim-Istatistikleri-2023-49535 (2024).

Pinheiro, M. N. C. & Castro, L. M. M. N. Effective moisture diffusivity prediction in two Portuguese fruit cultivars (Bravo de Esmolfe Apple and Madeira banana) using drying kinetics data. Heliyon 9, e17741 (2023).

EL-Mesery, H. S., Kamel, R. M. & Emara, R. Z. Influence of infrared intensity and air temperature on energy consumption and physical quality of dried apple using hybrid dryer. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 27, 101365 (2021).

Khudyakov, D., Sosnin, M., Shorstkii, I. & Okpala, C. O. R. Cold filamentary microplasma pretreatment combined with infrared dryer: Effects on drying efficiency and quality attributes of apple slices. J. Food Eng. 329, 111049 (2022).

Kukull, W. A. An apple a day to prevent Parkinson disease. Neurology 78, 1112 (2012).

Costa, J. M., Ampese, L. C., Ziero, H. D. D., Sganzerla, W. G. & Forster-Carneiro, T. Apple pomace biorefinery: Integrated approaches for the production of bioenergy, biochemicals, and value-added products—An updated review. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 10, 108358 (2022).

Shaheen, S. O. et al. Dietary antioxidants and asthma in adults. Am. J. Respirat. Crit. Care Med. 164, 1823–1828 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1164/ajrccm.164.10.

Pandiselvam, R. et al. Advanced osmotic dehydration techniques combined with emerging drying methods for sustainable food production: Impact on bioactive components, texture, color, and sensory properties of food. J. Texture Stud. 53, 737–762 (2022).

Mohammadi, I., Tabatabaekoloor, R. & Motevali, A. Effect of air recirculation and heat pump on mass transfer and energy parameters in drying of Kiwifruit slices. Energy 170, 149–158 (2019).

Bai, J. W. et al. Effects of different pretreatment methods on drying kinetics, three-dimensional deformation, quality characteristics and microstructure of dried apple slices. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 83, 103216 (2023).

Delfiya, D. S. A. et al. Drying kinetics of food materials in infrared radiation drying: A review. J. Food Process. Eng. 45, e13810 (2022).

Beigi, M. & Torki, M. Experimental and ANN modeling study on microwave dried onion slices. Heat. Mass. Transf./Waerme- Und Stoffuebertragung. 57, 787–796 (2021).

Ullah, F. et al. An approach to evaluate dehydration of apples (Malus domestica L) with the effect of temperature and time interval under the response surface method. Int. J. Fruit Sci. 21, 657–669 (2021).

Teymori-Omran, M. et al. Enhancing energy efficiency and retention of bioactive compounds in apple drying: Comparative analysis of combined hot air–Infrared drying strategies. Appl. Sci. 13, 7612 (2023).

Bao, X. et al. Effects of vacuum drying assisted with condensation on drying characteristics and quality of apple slices. J. Food Eng. 340, 111286 (2023).

Aradwad, P. P., Venkatesh, T. & Mani, I. Infrared drying of apple (Malus domestica) slices: Effect on drying and color kinetics, texture, rehydration, and microstructure. J. Food Process. Eng. 46, e14218 (2023).

Yu, L., Turner, M. S., Fitzgerald, M., Stokes, J. R. & Witt, T. Review of the effects of different processing technologies on cooked and convenience rice quality. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 59, 124–138 (2017).

Thamkaew, G., Sjöholm, I. & Galindo, F. G. A review of drying methods for improving the quality of dried herbs. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 61, 1763–1786 (2021).

Barrett, D. M., Beaulieu, J. C., Shewfelt, R. & Color Flavor, texture, and nutritional quality of Fresh-Cut fruits and vegetables: desirable levels, instrumental and sensory measurement, and the effects of processing. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 50, 369–389 (2010).

Yang, J. et al. Food irradiation: an emerging processing technology to improve the quality and safety of foods. Food Rev. Int. 40, 2321–2343 (2024).

Dehnad, D. et al. The influence of high hydrostatic pressure on different properties of legume proteins with an emphasis on soy proteins; a comprehensive review. Food Hydrocoll. 146, 109188 (2024).

Yan, B. et al. From laboratory to industry: The evolution and impact of pulsed electric field technology in food processing. Food Rev. Int. 41, 373–398 (2025).

Bayati, M., Lund, M. N., Tiwari, B. K. & Poojary, M. M. Chemical and physical changes induced by cold plasma treatment of foods: A critical review. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 23, e13376 (2024).

Yuan, Y. et al. Process optimization of CO2 high-pressure and low-temperature explosion puffing drying for apple chips using response surface methodology. Dry. Technol. 40, 100–115 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1080/07373937.2020.1771361

Waghmare, R. B., Choudhary, P., Moses, J. A., Anandharamakrishnan, C. & Stapley, A. G. F. Trends in approaches to assist freeze-drying of food: A cohort study on innovations. Food Rev. Int. 38, 552–573 (2022).

Deng, L. Z. et al. Chemical and physical pretreatments of fruits and vegetables: Effects on drying characteristics and quality attributes—a comprehensive review. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 59, 1408–1432 (2019).

Abul-Fadl, M. M., Ghanem, T. H., EL-Badry, N. & Nasr, A. Effect of puff drying on seedless grape fruits quality criteria compared to convective air drying. Al-Azhar J. Agric. Res. 45, 75–91 (2020).

La Fuente, C. I. A. & Lopes, C. C. HTST puffing in order to produce crispy banana - The effect of the step-down treatment prior to air-drying. LWT 92, 324–329 (2018).

Li, Y., Feng, X., Liu, Y. & Han, X. Apple quality identification and classification by image processing based on convolutional neural networks. Sci. Rep. 11, 1–15 (2021).

Khoshnoudi-Nia, S. & Moosavi-Nasab, M. Prediction of various freshness indicators in fish fillets by one multispectral imaging system. Sci. Rep. 9, 1–11 (2019).

Bai, J. W. et al. Potato slices drying: Pretreatment affects the three-dimensional appearance and quality attributes. Agriculture 12(12), 1841 (2022).

Tian, X. Y. et al. Quantitative analysis and visualization of moisture and anthocyanins content in purple sweet potato by Vis–NIR hyperspectral imaging. J. Food Process. Preserv. 45, e15128 (2021).

Bai, J. W., Zhang, L., Cai, J. R., Wang, Y. C. & Tian, X. Y. Laser light backscattering image to predict moisture content of Mango slices with different ripeness during drying process. J. Food Process. Eng. 44, e13900 (2021).

More, P. R. & Arya, S. S. Intensification of bio-actives extraction from pomegranate peel via microwave irradiation: Effect of factors, optimization, kinetics, and bioactive profiling. Chem. Eng. Process. Process Intensif. 202, 109839 (2024).

Tai, K. et al. The effect of sterol derivatives on properties of soybean and egg yolk lecithin liposomes: Stability, structure and membrane characteristics. Food Res. Int. 109, 24–34 (2018).

Merino, D., Simonutti, R., Perotto, G. & Athanassiou, A. Direct transformation of industrial vegetable waste into bioplastic composites intended for agricultural mulch films. Green Chem. 23, 5956–5971 (2021).

Jahanbakhsh Oskouei, M., Alizadeh Khaledabad, M., Almasi, H., Hamishekar, H. & Amiri, S. Preparation and characterization of kafirin/pla electrospun nanofibers activated by syzygium aromaticum essential oil. Polym. Bull. 81, 10061–10079 (2024).

TEPE, T. K. Convective drying of golden delicious Apple enhancement: drying characteristics, artificial neural network modeling, chemical and ATR-FTIR analysis of quality parameters. Biomass Convers. Biorefin. 14, 13513–13531 (2024).

Lan, W., Renard, C. M. G. C., Jaillais, B., Leca, A. & Bureau, S. Fresh, freeze-dried or cell wall samples: Which is the most appropriate to determine chemical, structural and rheological variations during apple processing using ATR-FTIR spectroscopy? Food Chem. 330, 127357 (2020).

Nizamlioglu, N. M., Yasar, S. & Bulut, Y. Chemical versus infrared spectroscopic measurements of quality attributes of sun or oven dried fruit leathers from apple, plum and apple-plum mixture. LWT 153, 112420 (2022).

Grabska, J., Beć, K. B., Ueno, N. & Huck, C. W. Analyzing the quality parameters of apples by spectroscopy from Vis/NIR to NIR region: A comprehensive review. Foods 12, 1946 (2023).

AOAC. Total, soluble, and insoluble dietary fiber in foods, V: Official methods of analysis of AOAC international. In 16th ed. (ed. P. Cunniff) vol 32 7–9 (Gaithersburg, 1999).

Singleton, V. L. & Rossi, J. A. Colorimetry of total phenolics with phosphomolybdic–phosphotungstic acid reagents. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 16, 144–158 (1965).

Baltacıoğlu, C., Baltacıoğlu, H., Okur, İ., Yetişen, M. & Alpas, H. Recovery of phenolic compounds from peach pomace using conventional solvent extraction and different emerging techniques. J. Food Sci. 89, 1672–1683 (2024).

Huang, L., lue, Zhang, M., Wang, L., ping, Mujumdar, A. S. & Sun, D. feng. Influence of combination drying methods on composition, texture, aroma and microstructure of apple slices. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 47, 183–188 (2012).

Urbas, S. et al. Predicting milk traits from spectral data using Bayesian probabilistic partial least squares regression. Ann. Appl. Stat. 18, 3486–3506 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1214/24.

Acknowledgements

This investigation of the third co-author was supported by the Turkish Council of Higher Education (YÖK) for fellowships of Visiting Scientists on Sabbatical to the Technical University of Denmark.

Funding

This research has been supported by the Scientific Research Projects Coordination Unit of Niğde Ömer Halisdemir University. Project No: TGT 2022/18-BAGEP.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Resources, data validation, funding acquisition, data curation, and supervision: Hande Baltacioglu, Cem Baltacioglu. Formal analysis, investigations, reviewing, and editing: Mehmet Yetisen. Conceptualization, original draft writing, reviewing, and editing: Aberham Hailu Feyissa.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Baltacıoğlu, C., Yetişen, M., Baltacıoğlu, H. et al. Determination of physicochemical properties and bioactive compounds of dried apples by FTIR spectroscopy and multispectral imaging. Sci Rep 15, 28086 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-13464-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-13464-8

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Enhancing Quality in Ultrasound-Assisted Puffing Drying of Apples: Optimization of Process Parameters and Phenolic Retention Modeling

Food and Bioprocess Technology (2026)

-

Ultrasound-assisted osmotic dehydration pretreatment enhances drying kinetics, quality attributes, bioactive compounds, microstructure, FTIR profiles, and sensory properties of Litchi

Scientific Reports (2025)