Abstract

Pulmonary disease can severely impair respiratory function and be life-threatening. Accurately recognizing pulmonary diseases in chest X-ray images is challenging due to overlapping body structures and the complex anatomy of the chest. We propose an adaptive multiscale feature fusion model for recognizing Chest X-ray images of pneumonia, tuberculosis, and COVID-19, which are common pulmonary diseases. We introduce an Adaptive Multiscale Fusion Network (AMFNet) for pulmonary disease classification in chest X-ray images. AMFNet consists of a lightweight Multiscale Fusion Network (MFNet) and ResNet50 as the secondary feature extraction network. MFNet employs Fusion Blocks with self-calibrated convolution (SCConv) and Attention Feature Fusion (AFF) to capture multiscale semantic features, and integrates a custom activation function, MFReLU, which is employed to reduce the model’s memory access time. A fusion module adaptively combines features from both networks. Experimental results show that AMFNet achieves 97.48% accuracy and an F1 score of 0.9781 on public datasets, outperforming models like ResNet50, DenseNet121, ConvNeXt-Tiny, and Vision Transformer while using fewer parameters.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Pulmonary diseases typified by pneumonia, tuberculosis, and COVID-19 seriously endanger human health. As reported by the Global Child Pneumonia Forum organization in 20201, globally, 800,000 children die each year from pneumonia, more than any other infectious disease affecting children under five years of age. Furthermore, the number of global deaths from tuberculosis increased dramatically during 2019–2021, reversing the previous year-on-year decline, with about 10.6 million people (95% UI: 9.9–11 million) developing tuberculosis in 20212, and about 14.9 million people dying directly or indirectly from COVID-19 (95% UI 13.3–16.6 million) in the same year3. Effective and rapid screening and medical response to people suspected of being infected with pulmonary diseases is urgently needed to curb the toll of pulmonary disease promptly.

There are several common causative factors for pulmonary disease, some of which are controllable, such as smoking, air pollution, and unhealthy lifestyles, while others are due to genetic factors and the work environment. It is essential to accurately recognize pulmonary disease because it is not apparent in its early stages4. To make sure that no one with the disease can be missed and no one without the disease can be misdiagnosed is the primary goal of doctors in screening for pulmonary disease.

Routine blood tests and the collection of respiratory specimens for testing are common clinical methods used to screen for pulmonary disease. These two tests are more accurate but have the disadvantage of requiring laboratory facilities and specialized manual handling5. Chest X-ray (CXR) is rapid, non-invasive, relatively inexpensive, and allows for clinical monitoring of disease progression. Imaging physicians review the film to make a diagnosis, a process that requires professionalism and concentration. When imaging physicians work around the clock, it is easy to miss and misdiagnose diseases.

Manual diagnosis of diseases is a costly, time-consuming, and error-prone process. Detecting abnormalities manually is difficult because symptoms in the early stages are minor and may go undetected due to negligence6. To reduce the burden of imaging physicians, deep learning has become the technology of choice for assisted diagnosis in medical imaging and has a significant impact on medical imaging7.

Given the problems existing in the pulmonary mentioned above medical image recognition, an adaptive weight fusion network model named Adaptive Multiscale Fusion Net (AMFNet) is proposed. The model realizes the precise recognition of pulmonary medical images. The contributions of the study are summarized as follows.

-

1.

The Fusion Basic Block and Multiscale Layer are designed to realize high-precision pulmonary medical image recognition. The Fusion Basic Block realizes wide-area coding, and the Multiscale Layer considers different levels of semantic information. A new network model, MFNet, is proposed based on these two primary units. The advantage of this network is that it is easier to focus on feature information;

-

2.

AMFNet is designed for model fusion to prevent the model from falling into local optimum. The AMFNet reduces the error and uncertainty of individual models and improves the reliability of the overall identification.

Compared with existing methods, the proposed AMFNet introduces several key innovations. It features a lightweight multiscale feature extraction network (MFNet) designed to capture fine-grained details efficiently with low computational cost. To improve feature diversity and robustness, AMFNet adaptively fuses representations from both MFNet and ResNet50, addressing some limitations of approaches relying on a single backbone. Additionally, the use of SCConv, AFF, and MFReLU modules enhances the model’s ability to discriminate features while maintaining computational efficiency. These elements together contribute to AMFNet’s strong performance on public chest radiography datasets, balancing accuracy and parameter efficiency when compared with popular CNN and Transformer-based models.

The remaining sections of the manuscript are structured as follows: Sect. "Related work" provides an overview of the related work. Section "Materials and methods" introduces the Adaptive Multiscale Fusion Net, a deep learning-based approach to recognizing pulmonary diseases accurately. This section outlines the adaptive multiscale feature fusion strategies devised for pulmonary disease recognition. A brief description of the utilized data also is presented in Sect. "Materials and methods". Section “Related work” presents and discusses the experimental results. Section "Experimental condition" discusses why our model in publicly available medical imaging datasets misclassifies cases. Finally, Sect. "Adaptive multiscale fusion net" provides a comprehensive summary of the entire work.

Related work

Deep learning has recently advanced biomedical image processing, particularly in pulmonary disease classification. Computer-aided diagnosis has gained attention, especially in analyzing pulmonary X-ray and CT images, with extensive research by scholars. We have summarized studies on pulmonary disease classification using machine learning and deep learning techniques. Table 1 highlights their contributions and limitations, supporting early diagnosis and treatment.

Deep learning algorithmic models can extract features that are not obvious from the original image. In medical image recognition, deep learning models based on convolutional neural networks with integrated attentional mechanisms are rapidly growing in applications for assisted diagnosis. Ezzat et al.14 used the Gravitational Search Algorithm to optimize DenseNet121 to help identify samples with COVID-19. Tekerek et al.15 designed the Dense-MobileNet network based on the characteristics of classic models to detect COVID-19 from chest X-ray images. The studies mentioned above, and those listed in Table 1 all use single-model algorithms for disease detection in chest X-rays. Single models may be more sensitive to the pathological features of certain diseases due to their structural focus, making them less effective in identifying other types of diseases.

Many researchers are committed to exploring the application of model fusion strategy in lung disease recognition. Karar et al.16 used the VGG16, ResNet121, and VGG16 algorithms to optimize DenseNet121 to help identify samples with COVID-19. VGG16, ResNet50V2, and DenseNet169 form a cascade classifier to improve the detection accuracy of computer-aided diagnostic systems for diseases. Adnane et al.17 propose a novel two-step approach for chest disease classification. The strategy is based on ensembling deep convolutional neural networks and transformer models. The proposed model uses the features extracted by the classical model to use the additive fusion strategy. Using multiple models to extract different types of features from images has achieved better results than using a single model.

In addition, deep learning models based on the Transformer module are popular in computer vision and have some applications in medical images. Park et al.18 proposed a new model for Vision Transformer for COVID-19 for the features of CXR, which is not limited to the classification task. It can also achieve disease recognition by quantifying disease severity based on patient images. Zheng et al.19 constructed a graph convolutional network by embedding image patches in feature vectors using contrast learning and then applied Vision Transformer to predict the whole-slice image analysis. Sun et al.20 evaluated the performance of the Swin Transformer model in the classification and segmentation of lung cancer. Transformer models used in the medical field often have a large number of parameters and require substantial memory space, making them less suitable for deployment on smart devices in clinical settings21. Although convolutional neural networks remain the foundation of medical image modeling, the emergence of vision Transformers has introduced new research directions in the field. Shamshad et al. conducted a comprehensive review of these developments, summarizing both the potential applications and current limitations of Transformers in medical image analysis22.

The above research status shows that the research on medical image recognition based on deep learning has achieved some results, but there are still some shortcomings. For example, some classification models do not consider the interference of the tissues around the pulmonarys. There are also some network models with complex structures, large numbers of parameters and computation amount, and average classification performance. Many researchers still rely on using numerous classic models to identify diseases without further exploring the potential of multi-model fusion strategies.

Additionally, the following issues need to be considered when using deep learning models for common pulmonary disease recognition:

-

1.

Most COVID-19 cases have similar imaging features, including bilateral, multi-focal, ground-glass opacities with a peripheral or posterior distribution, predominantly located in the lower lobes in the early stages and pulmonary consolidation in the late stage. Although typical CXR images may be helpful for early screening of suspected cases, images of various types of pneumonia are similar23. The lesion area overlaps with other infectious and inflammatory pulmonary diseases, making it difficult for the model to better learn the difference between other causes of pneumonia and COVID-19.

-

2.

Pulmonary tuberculosis is specifically manifested as hollow cavities in the pulmonary formed by bacterial infection. Besides cavities, tuberculosis can be in the form of dense cloudiness in the middle and lower middle lobe, patchy opacity in the upper lobe, the density of coarse reticular nodules, nodules with unclear edges, a large amount of fluid in the pulmonary, miliary changes, discrete nodules with polymorphic changes such as volume loss or retraction, and many others. Therefore, recognizing TB with high accuracy from input chest X-ray images is a challenging task24.

-

3.

The standard chest X-ray image is a projection of the various tissues and organs inside and outside the chest cavity, including the soft tissues of the chest wall, bones, large blood vessels of the heart, and the lungs, superimposed on each other. Such projections in the lung field make it easy to misdiagnose a lesion. Similarly, an X-ray examination is easy to miss the diagnosis of subtle lung lesions, and it is difficult for any qualitative diagnosis.

In this study, we propose a high-precision pulmonary disease recognition system with a reduced parameter count by integrating two novel network models, MFNet and ResNet50, employing the adaptive multiscale feature fusion strategy. The MFNet considers diverse multiscale semantic information levels and surpasses conventional recognition and detection models across various metrics. Notably, MFNet adopts a dense connection structure akin to DenseNet, achieving pulmonary disease recognition with fewer parameters and heightened accuracy, particularly excelling in leakage rate, a significant improvement over models in existing systems. The adaptive multiscale feature fusion strategy is implemented to mitigate the risk of the model converging to local optima, reduce errors introduced by individual models, and enhance overall recognition reliability. Additionally, the proposed MFReLU activation function in MFNet is employed to focus more effectively on feature information within the deep network. Addressing category imbalance, we utilize a focal loss function that assigns weights to each category for equilibrium.

Materials and methods

Data processing of pulmonary medical images

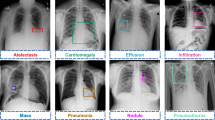

This experimental dataset is derived from four publicly available medical imaging datasets of the pulmonarys. The pneumonia images25 from pediatric patients aged 1 to 5 years at Guangzhou Women’s and Children’s Medical Center. The tuberculosis images26 from Qatar University in Doha, Qatar, and the University of Dhaka, Bangladesh. The COVID-19 image data collection from the COVID-19 dataset27 and the Vision and Image Processing Research Group at the University of Waterloo.

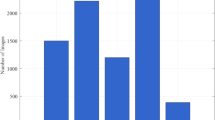

We use image data covering X-ray images of three common pulmonary diseases and normal human lungs. A total of 7,132 original images are selected, including 576 cases of COVID-19 pneumonia, 1,583 cases of normal, 4,273 cases of other pneumonia, and 700 cases of tuberculosis.

Since the normal undiseased and pulmonary disease lobe septal structures, pulmonary field edge features, dendritic shadow features, and pulmonary translucency are different, the corresponding X-ray images have different grayscale features, and representative samples of the four images and their three-dimensional grayscale maps are given here as shown in Fig. 1.

We divide the training set and test set according to the ratio of 4:1, obtain 5704 cases in the training set and 1428 cases in the test set, and construct the corresponding labels with them. The distribution of the samples is shown in Table 2. In the model training, COVID-19 samples are labeled as 0, pulmonary health samples are labeled as 1, pneumonia samples caused by reasons other than COVID-19 are labeled as 2, and tuberculosis samples are labeled as 3.

We select 300 images, each with a resolution of 224 × 224 pixels, from each of the four types of chest X-ray images. Each image is averaged with the other three to calculate the average SSIM28, and the results are presented in Fig. 2. The calculation results show that the SSIM value of the dataset is low, and it is expected that better results will be achieved using deep learning.

In data preprocessing, to prevent the network model from overfitting, the original digital X-ray images of the pulmonarys are processed by random horizontal flipping, and the processed images are used as network inputs. The images are not cropped considering the following factors: 1. The position of pulmonary texture, pulmonary nodules, and rib diaphragm relative to the pulmonary is one of the spatial features. 2. The complex information in the X-ray image can validate the model’s ability to focus on the focal region of the pulmonary.

Experimental condition

The experiments are based on Windows 11 64-bit system, Deep Learning Pytorch 1.13.0 framework, using Python version 3.8 on a computer configured with a CPU of 12th Gen Intel(R) Core(TM) i7-12700 K (20 CPUs) and a GPU of NVIDIA GeForce RTX 3090 graphics card and 32 GB RAM for training and testing. For more stable convergence, to solve the problem of dataset category imbalance, improve the model’s learning effect on a few sample size categories, and enhance the model robustness, focal loss29 is used as the model loss function. The loss function is defined as:

where \(c\) is the category of the current sample,\(\upalpha _{c}\) denotes the weight corresponding to category c, and \(p_{c}\) denotes the probability value of the output probability distribution for the category \(c\). The specific parameter settings are shown in Table 3.

Adaptive multiscale fusion net

Self-calibrated convolution

The Self-calibrated Convolution (SCConv) structure30 is shown in Fig. 3. SCConv consists of a global average pooling layer, the set of conventional 2D convolutional layers at \(\mathcal{F}\), and \(\mathcal{F}\) is associated with a group of filter sets \({\text{K}} = [{\text{k}}_{1} ,{\text{k}}_{2} , \ldots ,{\text{k}}_{i} ]\), where \({\text{k}}_{i}\) denotes the set of \(i\) the filters with the number of channels \(C\) and notates the inputs as \({\text{X}} = [{\text{x}}_{1} ,{\text{x}}_{2} , \ldots ,{\text{x}}_{C} ] \in {\mathbb{R}}^{C \times H \times W}\) and the outputs after the filters as \({\text{Y}} = [y_{1} ,y_{2} , \ldots ,y_{{\widehat{C}}} ] \in {\mathbb{R}}^{{\widehat{C} \times \widehat{H} \times \widehat{W}}}\). Given the above notation, the output feature map at channel i can be written as.

where \(*\) denotes convolution and \({\text{k}}_{i} = [{\text{k}}_{i}^{1} ,{\text{k}}_{i}^{2} , \ldots ,{\text{k}}_{i}^{C} ]\). As can be seen above, each output feature map is computed by summing over all channels, and all output feature maps are generated by repeating Eq. 2. Given the input \({\text{X}}_{1}\), using average pooling with filter size r×r and stride r, based on \(K_{1}\) performs the pooled feature transform, as follows.

Up is the bilinear interpolation operator that maps the intermediate reference from the small-scale space to the original feature space. The final output after calibration can be written as follows:

where \({\mathcal{F}}_{3} ({\text{X}}_{1} ) = {\text{X}}_{1} * {\text{K}}_{3}\), \(\sigma\) denote sigmoid functions and “\(\cdot\)” denotes element-by-element multiplication. As shown in Eq. 4, \(X^{\prime}_{1}\) is used as the residuals to form the weights for calibration. The pseudocode of SCConv is shown in Table 4.

Multiscale channel attention module

We consider the specificity of X-ray images, local attention and efficient channel attention31 are embedded in the Multiscale Channel Attention Module (MS-CAM)32. The structure of the MS-CAM is shown in Fig. 4.

Local Attention can be written as follows:

Efficient Channel Attention can be written as follows.

where \(X\) denotes the input feature tensor,\(\mathcal{B}\) denotes the batch normalization (BN) layer,\(\delta\) denotes the linear rectifier function (ReLU),\({\mathcal{V}}\) denotes the view function, and \(\sigma\) denotes the sigmoid function. Given a global channel context \({\text{E}} (X)\) and a local channel context \({\text{L}} (X)\), it can be written in the following form by MS-CAM:

where \({\text{M}} ({\text{X}} ) \in {\mathbb{R}}^{C \times H \times W}\) denotes the attentional weights generated by MS-CAM, \(\oplus\) denotes the additive function, and \(\otimes\) denotes the multiplicative function. The pseudocode of MS-CAM is shown in Table 5.

Attention feature fusion

Based on the MS-CAM, Attention Feature Fusion (AFF)33 is shown in Fig. 5. Add is the abbreviation of addition, and Mul is the abbreviation of multiplication. AFF can be expressed as:

where \({\text{Z}} \in {\mathbb{R}}^{C \times H \times W}\) is the fusion feature and \({ \uplus }\) denotes the initial feature integration. In this subsection, we choose element-by-element summation as the initial integration for simplicity. The dashed line is denoted \(1 - M(X{ \uplus }Y)\) in Fig. 5. It should be noted that the fusion weights \(M(X{ \uplus }Y)\) consist of true ones between 0 and 1, as does \(1 - M(X{ \uplus }Y)\), which allows the network to perform soft selection or weighted averaging between \(X\) and \(Y\).

Structure of adaptive multiscale fusion net

The pulmonary digital X-ray image recognition task can be implemented as a deep learning image classification task. To address the problems of pulmonary common disease recognition mentioned in the introduction, we propose an Adaptive Multiscale Fusion Net (AMFNet), an adaptive weight model fusion network.

The proposed Adaptive Multiscale Fusion Net consists of three parts: Multiscale Fusion Net (MFNet) as the primary feature extraction network, ResNet50 as the secondary feature extraction network, and finally, the extracted features from both models are input into an Adaptive Model Fusion Block. The MFNet architecture comprises two key components, Fusion Basic Block and Multiscale Layer. It selects the network model that performs well in the comparison experiments as the secondary feature extraction network. The optimizer trains the adaptive fusion network on the weights \(w_{1}\) and \(w_{2}\) occupied by the two feature extraction networks. The structure of the AMFNet model construction is shown in Fig. 6, where Cat is an abbreviation for Concatenate.

Fusion block

The Fusion Block consists of FusionBasicBlock, and the three Fusion Block units are stacked by 2, 6, and 12 layers of Fusion Basic Block modules in sequence. The modules are connected using a dense structure, enabling the later layers to access the low-level feature representations of the earlier layers more efficiently, thus improving the network’s ability to utilize different layers of features33. The Fusion Basic Block module network on the weights and introduces a fusion local attention and channel attention mechanism based on the bottleneck structure. Each convolutional layer is followed by a BN layer and a ReLU activation function structure, as shown in Fig. 7. The module extracts features from the input feature mapping X by 1 × 1 convolution at the head and tail of the block. The feature maps are fed into the fusion attention unit after 1 × 1 convolutional upscaling. There are three layers constituting the first and third layers, 1 × 1 convolutional upscaling and 1×1 convolutional downscaling, respectively, to capture richer and more abstract feature representations, which helps improve the model’s expressive power. The second layer is the feature fusion attention machine. The feature attention machine is divided into three parts. The first part is self-calibrated grouped convolution, and the structure is shown in Fig. 4. To distinguish it from other ReLU layers that follow convolution, the MFReLU layer, which comes after the self-calibrated grouped convolution, is illustrated in Fig. 7. The second part uses Channel Group channel grouping. The third part combines Local Attention and Channel Attention to realize feature fusion, and the fusion structure is shown in Figs. 4 and 5. The overall structure of the Fusion Basic Block is shown in Fig. 7, where Cat is the abbreviation of Concatenate.

Multiscale layer

The output dimension of each Fusion Block module is large, and the number of channels dramatically increases by stacking the modules, making the model too complex. To address this issue, a Multiscale Layer is designed to connect two neighboring Fusion Blocks, facilitating feature map size reduction. The Multiscale Layer layer consists of two 1 × 1 convolutional layers, 2 × 2 pooling, and Concatenate functions. The feature matrix is reduced by the first 1 × 1 convolution to reduce the feature map size, then through the pooling layer, and 1 × 1 size reduced feature matrix stitching, and the end of the 1 × 1 convolution to reduce the dimensionality. The Multiscale Layer layer fuses the features of different scales to capture the various levels of semantic information. The structure is shown in Fig. 8.

MFReLU

The problem of neuronal “necrosis” caused by the ReLU function34 can be avoided by replacing part of the negative half-axis with a sinusoidal function. The function expression we designed is as follows:

Considering the design of the activation function to be used in the deep network for extracting the complex abstract features of the digital X-ray images of the pulmonarys so that -2 to 1 is the domain of definition, the use of trigonometric functions, which have lower bounds in this domain of definition, can produce better regularization effect. The definition domain from 1 to positive infinity, the function without upper boundary is used as the positive semi-axis. In practice, the segmented function reduces the number of memory accesses and lowers the delay cost time35. The mathematical formula for the final combined activation function is:

The graph of the corresponding segmented activation function curve is shown in Fig. 9.

Adaptive model fusion block

Integrating feature information from different models can improve the expressiveness and performance of the overall model. In feature fusion, splicing fusion and summation fusion are commonly used strategies36. Splice fusion splices the primary and secondary model feature matrices while considering different dimensional features to form a richer composite feature representation that can capture more information and relevance. Summation fusion performs pixel-level summing operation of two features to achieve the function of complementary primary and secondary model feature matrices. Splice fusion and additive fusion are used to utilize their respective advantages fully.

The model fusion structure is shown in Fig. 10. The features extracted by the primary and secondary feature extraction networks are combined using concat and add operations, resulting in more enriched feature information. Then, mimicking the attention mechanism, a Softmax function is applied to weigh the input features, allowing this process to be trainable through backpropagation. Next, weight coefficients are assigned to the features processed by the multiple operation, which the optimizer will optimize as the training progresses. Finally, the final classification result is obtained through a linear layer after the add operation.

Evaluation indicators

Performance and complexity metrics are used to evaluate the model. The performance metrics include Accuracy (Acc), Precision (P), Recall (R), F1 Score (F1), and Area Under Curve (AUC)37. In practical applications, missed disease detection can delay the patient’s optimal treatment, so we focus on the recall metric. The complexity index includes the number of parameters \(Params_{conv}\). The specific formula of each model indicator is defined as follows:

Accuracy is the proportion of outcomes that the model predicts correctly. The formula is as follows:

Precision is the percentage of samples predicted to be in the positive category that are actually in the positive category. The formula is as follows.

Recall, also known as check all rate, is the proportion of all positive category samples that are correctly recognized as positive categories. The formula is as follows.

F1 Score is a weighted reconciled average of Precision and Recall. In Eq. 14, “P” and “R” are abbreviations for Precision and Recall, respectively. The equation is as follows.

Area Under Curve is a metric for evaluating the performance of a classification model, which is calculated based on the area under the Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve, with values ranging from 0 to 1, with larger values indicating better model performance. The formula is as follows.

The number of parameters is used as a common measure of model complexity. The formula is as follows.

Results

For the pulmonary X-ray image recognition network we proposed, three sets of experiments are designed to verify its effectiveness. The first set of experiments set up ablation experiments to explore the optimal location of the MFReLU to be used and the results are shown in Table 6. After that, the results of the experiments, compared with the other five common activation functions, are shown in Table 7, Figs. 11 and 12. The MFNet, with the addition of the designed activation function, is compared with the mainstream model, and the results are shown in Table 8. To verify the significance of MFNet’s advantages, we conducted a significance analysis based on the p-values obtained from five repeated experiments of F1 scores, and the results are shown in Table 9. The second set of experiments compares the proposed fusion method with other common fusion methods; the results are shown in Table 10, Figs. 15, 16. The third set of experiments does ablation experiments on the innovations we proposed, and the results are shown in Table 11. To further verify the performance of the proposed model, the comparison with other models is shown in Table 12.

Comparison with different activation functions

Pulmonary radiographic images include multiple structures of pulmonary tissue, airways, and bones. These structures cross and overlap, making it difficult for existing models to focus on effective feature information. As the network continues to deepen, the size of the feature map decreases, and the abstract information within the feature map increases as the network deepens. To better capture the semantic information on the feature maps of the deeper network, an activation function MFReLU is designed to provide more substantial expressive power in the deeper layers of the MFNet network.

Seven schemes are proposed based on the designed activation function for self-calibrated groupwise convolution in the Fusion Block of our proposed model, with results on the testing set shown in Table 6. In the table, “√” indicates that the corresponding strategy is used in the grouped self-calibration convolution in all Fusion Block layers of that part of the model, while “ × ” indicates that the strategy is not used in the grouped self-calibration convolution in that layer of the model. By comparing Scheme 1–4 and Scheme 7, it can be seen that adding only one layer or all of the designed activation functions does not improve the modeling effect significantly. By comparing Scheme 5 and Scheme 6, it can be seen that the activation function designed is more effective when added to the deeper layers of the network than to the shallower layers. The above comparison shows that Scheme 6 achieves the best effect, and we choose Scheme 6 to do the comparison experiment of replacing other activation functions in the same position. The table indicates the best results in bold, while the second-best results are underlined.

The activation function positions of the previously identified scheme 6 are sequentially replaced with different activation functions for comparison, including Hardswish38, FreLU39, SELU40, GELU41, and Leaky ReLU42. Figs. 11a shows the training loss curve of the model we designed by adding the activation function and different activation functions for 200 epochs on the datasets. Figs. 11b shows the 200 epochs testing loss curve of the model we designed by adding the activation function we designed and different activation functions on the datasets. The activation function we proposed achieves fast convergence and lower loss values.

The results of the comparison experiments of the activation functions on the testing set are shown in Table 7 and Fig. 12. Class 0 represents the COVID-19 class, Class 1 represents the Normal class, Class 2 represents the Pneumonia class, and Class 3 represents the Tuberculosis class. It can be seen that the activation function MFReLU we proposed has the best model boosting effect on the pulmonary disease dataset on the MFNet we proposed compared to the other five advanced activation functions. The table indicates the best results in bold, while the second-best results are underlined.

Based on the categorization of the dataset, the loss function is split into training loss and testing loss. The training and testing curves are shown in Fig. 13a, where the training loss and testing loss decrease rapidly when the number of iterations is between 0 and 50 during the training of the constructed model. When the number of iterations reaches 100 or more, the loss of the prediction model starts to stabilize gradually. As can be seen from the accuracy, precision, recall, and F1 score curves on the testing set in Fig. 13b, the model does not show any overfitting. Moreover, each accuracy index of the model ends up at 0.95 or above. It can be seen that MFNet, with the addition of the MFReLU activation function we designed, has high recognition accuracy for digital X-ray images of the pulmonarys.

The designed MFNet is compared with different network models, including ResNet5043, DenseNet12144, ConvNeXt-Tiny45, EfficientNetV2-Small46, Multi-layer perceptrons mixer-Base (MLP-Mixer-B)47, Vision Transformer-Base (Vit-B)48, Swin Transformer-Base (Swin-B)49, and Pyramid Vision Transformer-Tiny (Pvit-T)50. To highlight the parameter efficiency of our method, Table 8 presents comparison results for a subset of representative models with relatively small parameter sizes. The results of the testing set are shown in Table 8. The table shows that the mainstream network accuracy is better, but the number of parameters is higher, and the space complexity is larger. However, the MFNet outperforms the other comparative models with fewer parameters and fewer network layers. Comparing the MFNet with the mainstream convolutional neural network recognition model, the number of parameters of the MFNet is less than one-third of that of the ResNet50, but the MFNet achieves much better performance, especially in the Recall index, which is significantly better than the ResNet50. In particular, MFNet significantly outperforms ResNet in the Recall metric, and the number of MFNet parameters is less than one-tenth of that of ResNet50 when comparing MFNet with mainstream transformer structure recognition models. The table indicates the best results in bold, while the second-best results are underlined.

We conducted a significance analysis based on the p-values51 obtained from five repeated experiments of F1 scores. The smaller the p-value, the more significant the difference between the two methods on the same dataset. When the p-value falls within the range [0.01, 0.05], the difference is considered significant; when p < 0.01, the difference is considered highly significant. To better demonstrate the effectiveness of MFNet, Table 9 presents the p-values comparing MFNet with other baseline methods across different datasets and evaluation metrics. As shown in Table 9, MFNet exhibits a clear and significant advantage over the other compared methods.

To compare the difference between our model and other mainstream networks more visually, we use Grad-CAM52 as a visualization tool. The colors in Fig. 14 represent the attention of the network, which gradually increases from blue to red.

As shown in Fig. 14, For the COVID-19 category of chest radiographs, our model focuses on the lower lobes of the lungs and the edge of the septum, which can be seen as a dense band of transparent shadows in the original image. ResNet50 also focuses on the lower lobes of the lungs but to a lesser extent and also incorrectly focuses on the mid-mediastinal region. DenseNet121 focuses on the lower lobes of the right lung but ignores the left lung’s soft tissue and bony structures. ConvNeXt-T incorrectly focuses on the soft tissue and bony structures of the chest wall. ConvNeXt-T incorrectly focused on chest wall soft tissue and bone structures. For chest radiographs in the Normal category, the model focuses on both lung fields compared with the other comparative models. For the chest radiographs in the Pneumonia category, the model focuses on the area of increased lung markings and blurred edges in the middle band of both lungs, which can be seen in the original images, with increased lung markings and decreased lung transparency, which is a symptom of the congestive stage of pneumonia. ResNet50 and DenseNet121 focus on the right lung field. ConvNeXt-T incorrectly focuses on the chest wall’s soft tissues and bone structures. For the tuberculosis category of chest radiographs, our models focus on irregular striated shadows in the left lung, which appear to extend from the primary lesion towards the hilum.

In contrast, other models focus on bone structures that are unrelated to the lesion. Our model can mine more useful feature information and focus on the pulmonary parenchyma region more accurately than the models with the top three rankings of metric AUC score in the comparison experiments.

Five groups of mainstream models are selected above for comparison. The experimental results show that our designed network achieves better results in both F1 and AUC scores. Compared to the second-place ResNet50 model, our model has only one-third of its parameters, yet it shows slight improvements in performance. Additionally, the F1 Score of our model is 0.0634 higher than that of the least effective Vision Transformer model, demonstrating better recognition performance.

As shown in Fig. 14, among the four models with the highest recognition accuracy, ResNet50 performs second only to the model proposed in this study. In addition, its residual structure helps mitigate performance degradation during deep feature extraction and forms a good complement to the multiscale feature representations learned by the primary feature extraction network, MFNet. Therefore, ResNet50 is selected as the secondary backbone network.

Comparison with different convergence strategies

Table 10 demonstrates the results of the fusion method we proposed with Arithmetic Averaging53 and Weight Averaging54 results of the comparison experiments. The fusion network’s predominant and secondary feature extraction models are adopted from the two network models performing best on the datasets. AMFNet improves on all the metrics compared to the fusion networks that use other common deep-learning fusion strategies. Compared with the Arithmetic Averaging Fusion strategy, the Accuracy, Precision, Recall, and F1 Score are mainly improved by 0.7%, 0.0137, 0.0097, and 0.0118; compared with the Weight Averaging Fusion strategy, the Accuracy, Precision, Recall, and F1 Score are mainly improved by 0.35%, 0.0115, 0.0005, and 0.0061; and the AUC score exceeds that of the two models using other fusion strategies. The table indicates the best results in bold, while the second-best results are underlined.

Figs. 15a,b show the comparison between AMFNet and different fusion strategies on the testing set, and the blue triangular arrow curve represents the AMFNet method proposed. AMFNet outperforms the other two model fusion strategies in P and R metrics.

Figs. 16a,b,c show the comparison of the confusion matrices of the Arithmetic Averaging Fusion strategy, Weighted Averaging Fusion strategy, and AMFNet on the test set in turn. The 0, 1, 2, and 3 of these figures represent COVID-19, Normal, Pneumonia, and Tuberculosis in that order. In the specialized field of medical imaging, the high-risk disease category is often designated as the positive category. Omitting a positive diagnosis is extremely costly, as it may lead to delayed treatment for the patient. Therefore, it is crucial to minimize the rate of missed diagnoses, with misdiagnoses being significantly less critical compared to missed diagnoses.

Comparing the confusion matrices in Fig. 16a,b,c with medical image specificity, it can be observed that the Arithmetic Averaging Fusion strategy identifies 14 pneumonia samples as healthy, while the Weighted Averaging Fusion strategy identifies 17 pneumonia samples as healthy. AMFNet recognizes better on the pneumonia images and is less likely to recognize the pneumonia samples as normal compared to the other strategies. Moreover, AMFNet did 100% recognition of COVID-19 disease, which has been popular in recent years. Therefore, AMFNet is more suitable in the field of medical auxiliary diagnosis.

In Table 11, Model A is the MFNet without focal loss; Model B is the MFNet with focal loss; Model C replaces the activation function in MFNet with MFReLU; Model D uses the Adaptive Fusion strategy based on Model B; and Model E uses the Adaptive Fusion strategy based on Model C. The details are as follows. In the table, the best results are indicated in bold, while the second-best results are underlined.

MFReLU: The original activation function ReLU in the network is replaced with MFReLU to enable the model to acquire more complex image contexts. Model C achieves Acc and AUC of 0.9720 and 0.9981. R and F1 are as high as 0.9759 and 0.9731, which are 0.4% and 0.5% higher than the MFNet network. The experimental results show improved recognition accuracy for most of the pulmonary X-ray images, proving the effectiveness of the MFReLU activation function for network optimization.

Adaptive Fusion: By comparing Model E using the Adaptive Fusion strategy with Model C, which does not use the Adaptive Fusion strategy, R and F1 are improved by 0.2% and 0.5%, respectively. This shows that the added model fusion network can significantly reduce missed detection due to individual model feature learning errors on X-ray medical image recognition. However, the model size increases due to the added model fusion structure.

To further validate the performance of the proposed model AMFNet, we compared it with ResNet50, InceptionV455, DenseNet121, ConvNeXt-T, Vision Transformer-Base (Vit-B), Swin Transformer-Base (Swin-B), Pyramid Vision Transformer-Tiny (Pvit-T), and ResNeXt5056, a variant of the ResNet50-based network that improves recognition performance. The results of the testing set are shown in Table 12. In the table, the best results are indicated in bold, while the second-best results are underlined.

Compared to other networks, our proposed model is optimal in Acc, P, R, F1, and AUC. Compared with other mainstream image recognition networks, our proposed model has a significant advantage in terms of miss detection rate. The maximum recall and maximum F1 Score are improved by 8.0% and 7.5%, respectively. The experimental results show that the fusion network AMFNet we proposed improves in all the indexes compared to MFNet + MFReLU and ResNet50 before fusion.

Compared to ResNet50, the Accuracy, Precision, Recall, and F1 scores are mainly improved by 0.63%, 0.0151, 0.0139, and 0.0123. Compared to MFNet + MFReLU, the Accuracy, Precision, Recall, and F1 scores are mainly improved by 0.28%, 0.0082, 0.0017, and 0.005. The model’s AUC scores exceed those of the two models before fusion. In summary, the overall performance of the proposed model is better than that of the comparison model.

The experimental results in Table 12. Demonstrate that MFNet exhibits high accuracy and low parameter requirements in recognizing lung diseases from X-ray images. This is attributed to MFNet being constructed using the Fusion Basic Block, which employs feature fusion concepts, and the Multiscale Layer, which incorporates multi-scale ideas. In the Fusion Basic Block, MFReLU is used in place of the original ReLU activation function, enabling the model to capture more complex image contextual information and further improve MFNet’s performance in recognizing lung diseases from X-ray images. Finally, by adopting a multi-model strategy that combines features extracted by both MFNet and a suboptimal model, accurate recognition of common lung diseases in X-ray images is achieved.

Discussion

The above shows eight cases where the improved model AMFNet incorrectly identified lung X-ray images. Since the recognition accuracy for tuberculosis and normal lungs is already high, we select typical cases where the model misclassified images from pneumonia and normal categories for error analysis to highlight the model’s shortcomings. In Fig. 17, we name the eight images in sequence from top to bottom and left to right as the first to the eighth image. Because increased and intensified lung markings can occur in young adults, long-term smokers, or individuals after intense physical activity in high temperatures, it is necessary to consider medical history and pathological conditions for accurate diagnosis. Accurate identification can only be made if clinical symptoms such as high fever, cough, and shortness of breath are present.

The first to fourth chest X-rays show increased and coarser lung markings without obvious exudative lesions. These images require clinical and contextual analysis; if there are no clinical symptoms, the increased markings on the X-ray might be normal. Such images make it difficult for the model to accurately identify issues based solely on pathological features without clinical evidence. The fifth image shows increased, blurred lung markings with widespread reticular and small nodular shadows in the lower right lung and hilum. The sixth and seventh images display increased, coarser lung markings, with dense strip-like and nodular shadows distributed along the bronchi in the middle and inner lung zones, with blurred edges. In the eighth image, the right lung field shows a significant exudative lesion, presenting as a patchy dense shadow close to the heart border. The model may have misclassified images labeled as pneumonia due to the exudate’s proximity to the heart border.

Finally, due to the lack of specific medical history and other patient information, it is difficult to determine whether the abnormal locations identified by our proposed model are accurate when using heatmaps to display areas of interest. This makes comparing these findings with the actual conditions challenging, limiting our ability to refine the model based on visual results. Therefore, more accurate datasets containing lesion locations and detailed case information should be constructed to improve AMFNet’s performance further.

Conclusion

Respiratory system diseases are common and diverse; X-ray examination is crucial in respiratory diagnosis. The close anatomical relationship between the lungs and the mediastinum means that some lung lesions can involve the mediastinum, complicating X-ray examination. To improve the accuracy of pulmonary X-ray image recognition, we introduce the Fusion Basic Block and the Multiscale Layer. The new network model, MFNet, which incorporates these two basic blocks, enables a more accurate focus on feature information with fewer parameters, making it better suited for deployment on edge devices for computer-aided diagnosis. Additionally, AMFNet is designed for model fusion to effectively prevent the model from falling into local optima. This fusion strategy reduces errors and uncertainties associated with single models and improves recognition reliability.

Experiments with the pulmonary chest radiography dataset demonstrate that the proposed MFNet outperforms other classification network models in nearly all evaluation metrics. Compared to classical networks, AMFNet achieves an accuracy of 97.48% in recognizing common pulmonary diseases on a public dataset, with an F1 score of 0.9781 and an AUC score of 0.9985.

The proposed AMFNet also shows significant advantages, particularly in achieving a low misdiagnosis rate. In addition, the model has relatively few parameters, making it easier to deploy on smart devices in hospital emergency rooms and public healthcare facilities. Since AMFNet is composed of a multi-model structure, the time required to train the optimal weights is relatively longer than training a single model.

However, the method we presented has some limitations. Future work will explore fusion strategies for feature information across different modalities and consider the severity of pulmonary diseases more comprehensively to provide doctors with a more reliable basis for judgment.

Data availability

Medical pulmonary imaging for training and testing is available from this website: https://www.kaggle.com/paultimothymooney/chest-xray-pneumonia,https://www.kaggle.com/tawsifurrahman/tuberculosis-tb-chest-xray-dataset,https://github.com/ieee8023/tablecovid-chestxray-dataset,https://github.com/agchung/Figure1-COVID-chestxray-dataset.

Code availability

The Python code can be provided upon request to the corresponding author. The access link is as follows: https://github.com/glp199898/Adaptive-Multiscale-Fusion-Net. The password to unzip the file is 20240830SR.

References

Golshaie, A. The first global forum on childhood pneumonia. Lancet Respir. Med. 8(3), 237 (2020).

Bagcchi, S. WHO’s global tuberculosis report 2022. Lancet Microbe 4(1), e20 (2023).

Taylor, L. Covid-19: True global death toll from pandemic is almost 15 million, says WHO. BMJ Br. Med. J. (Online) 377, o1144 (2022).

Ma, J. et al. Survey on deep learning for pulmonary medical imaging. Front. Med. 14(4), 450–469 (2020).

Feldman, C. & Shaddock, E. Epidemiology of lower respiratory tract infections in adults. Expert Rev. Respir. Med. 13(1), 63–77 (2019).

Sahu, A., Das, P. K. & Meher, S. An efficient deep learning scheme to detect breast cancer using mammogram and ultrasound breast images. Biomed. Signal Process. Control 87, 105377 (2024).

Litjens, G. et al. A survey on deep learning in medical image analysis. Med. Image Anal. 42, 60–88 (2017).

Brunese, L., Mercaldo, F., Reginelli, A. & Santone, A. Explainable deep learning for pulmonary disease and coronavirus COVID-19 detection from X-rays. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. 196, 105608 (2020).

Vieira, P., Sousa, O., Magalhães, D., Rabêlo, R. & Silva, R. Detecting pulmonary diseases using deep features in X-ray images. Pattern Recognit. 119, 108081 (2021).

Karar, M. E., Hemdan, E.E.-D. & Shouman, M. A. Cascaded deep learning classifiers for computer-aided diagnosis of COVID-19 and pneumonia diseases in X-ray scans. Complex Intell. Syst. 7, 235–247 (2021).

Dianat, B. et al. Classification of pulmonary sounds through deep learning for the diagnosis of interstitial lung diseases secondary to connective tissue diseases. Comput. Biol. Med. 160, 106928 (2023).

Chen, R. J. et al. Pan-cancer integrative histology-genomic analysis via multimodal deep learning. Cancer Cell 40, 865-878.e6 (2022).

Farhan, A. M. Q. & Yang, S. Automatic lung disease classification from the chest X-ray images using hybrid deep learning algorithm. Multimedia Tools Appl. 82(25), 38561–38587 (2023).

Ezzat, D., Hassanien, A. E. & Ella, H. A. An optimized deep learning architecture for the diagnosis of COVID-19 disease based on gravitational search optimization. Appl. Soft Comput. 98, 106742 (2021).

Tekerek, A. & Al-Rawe, I. A. M. A novel approach for prediction of lung disease using chest x-ray images based on DenseNet and MobileNet. Wirel. Personal Commun. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11277-023-10489-y (2023).

Karar, M. E., Hemdan, E. E. D. & Shouman, M. A. Cascaded deep learning classifiers for computer-aided diagnosis of COVID-19 and pneumonia diseases in X-ray scans. Complex Intell. Syst. 7(1), 235–247 (2021).

Nasser, A. A. & Akhloufi, M. A. Deep learning methods for chest disease detection using radiography images. SN Comput. Sci. 4(4), 388 (2023).

Park, S. et al. Multi-task vision transformer using low-level chest X-ray feature corpus for COVID-19 diagnosis and severity quantification. Med. Image Anal. 75, 102299 (2022).

Zheng, Y. et al. A graph-transformer for whole slide image classification. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 41(11), 3003–3015 (2022).

Sun, R., Pang, Y. & Li, W. Efficient lung cancer image classification and segmentation algorithm based on an improved swin transformer. Electronics 12(4), 1024 (2023).

Shamshad, F. et al. Transformers in medical imaging: A survey. Med. Image Anal. 88, 102802 (2023).

Shamshad, F. et al. Transformers in medical imaging: A survey. Med. Image Anal. 88, 102802 (2023).

Chowdhury, M. E. H. et al. Can AI help in screening viral and COVID-19 pneumonia?. IEEE Access 8, 132665–132676 (2020).

Zaidi, S. Z. Y., Akram, M. U., Jameel, A. & Alghamdi, N. S. A deep learning approach for the classification of TB from NIH CXR dataset. IET Image Process 16, 787–796 (2022).

Kermany, D. S. et al. Identifying medical diagnoses and treatable diseases by image-based deep learning. Cell 172, 1122-1131.e9 (2018).

Rahman, T. et al. Reliable tuberculosis detection using chest X-Ray with deep learning, segment and visualization. IEEE Access 8, 191586–191601 (2020).

Cohen, J. P. et al. COVID-19 image data collection: Prospective predictions are the future. Mach. Learn. Biomed. Imaging 1, 1–38 (2020).

Palubinskas, G. Image similarity/distance measures: what is really behind MSE and SSIM?. Int. J. Image Data Fusion 8(1), 32–53 (2017).

Romdhane, T. F. & Pr, M. A. Electrocardiogram heartbeat classification based on a deep convolutional neural network and focal loss. Comput. Biol. Med. 123, 103866 (2020).

Liu J J, Hou Q, Cheng M M, et al. Improving convolutional networks with self-calibrated convolutions. In: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition. 10096–10105. (2020).

Wang Q, Wu B, Zhu P, et al. ECA-Net: Efficient channel attention for deep convolutional neural networks. In: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference On Computer Vision And Pattern Recognition. 11534–11542. (2020).

Dai Y, Gieseke F, Oehmcke S, et al. Attentional feature fusion. In: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision. 3560–3569. (2021).

Huang G, Liu S, Van der Maaten L, et al. Condensenet: An efficient densenet using learned group convolutions. In: Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition. 2752–2761. (2018).

Cheridito, P., Jentzen, A. & Rossmannek, F. Landscape analysis for shallow neural networks: complete classification of critical points for affine target functions. J. Nonlinear Sci. 32(5), 64 (2022).

Wang, P. et al. Identification of apple leaf diseases by improved deep convolutional neural networks with an attention mechanism. Front. Plant Sci. 12, 723294 (2021).

Yang, G. & Zou, W. Deep learning network model based on fusion of spatiotemporal features for action recognition. Multimedia Tools Appl. 81(7), 9875–9896 (2022).

Liu, Q. et al. Semi-supervised medical image classification with relation-driven self-ensembling model. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 39(11), 3429–3440 (2020).

Howard A, Sandler M, Chu G, et al. Searching for mobilenetv3. In: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision. 1314–1324. (2019).

Ma N, Zhang X, Sun J. Funnel activation for visual recognition. In: Computer Vision–ECCV 2020: 16th European Conference, Glasgow, UK, August 23–28, 2020, Proceedings, Part XI 16. 351-368. (Springer International Publishing, 2020).

Klambauer, G. et al. Self-normalizing neural networks. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 30, 972–981 (2017).

Hendrycks D, Gimpel K. Bridging nonlinearities and stochastic regularizers with Gaussian error linear units. https://arXiv.org/abs/1606.08415. (2016).

Maas, A. L., Hannun, A. Y. & Ng, A. Y. Rectifier nonlinearities improve neural network acoustic models. Proc. ICML 30(1), 3 (2013).

He K, Zhang X, Ren S, et al. Deep residual learning for image recognition. In: Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition. 770–778. (2016).

Huang G, Liu Z, Van Der Maaten L, et al. Densely connected convolutional networks. In: Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition. 4700–4708. (2017).

Liu Z, Mao H, Wu C Y, et al. A convnet for the 2020s. In: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition. 11976–11986. (2022).

Tan M, Le Q. Efficientnetv2: Smaller models and faster training. In: International Conference on Machine Learning. 10096–10106. (PMLR, 2021).

Tolstikhin, I. O. et al. Mlp-mixer: An all-mlp architecture for vision. Adv. Neural. Inf. Process. Syst. 34, 24261–24272 (2021).

Alexey D. An image is worth 16x16 words: Transformers for image recognition at scale. https://arXiv.org/abs/2010.11929, (2020).

Liu Z, Lin Y, Cao Y, et al. Swin transformer: Hierarchical vision transformer using shifted windows. In: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision. 10012–10022. (2021).

Wang W, Xie E, Li X, et al. Pyramid vision transformer: A versatile backbone for dense prediction without convolutions. In: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision. 568–578. (2021).

Tang, S. & Tsui, K. W. Distributional properties for the generalized p-value for the Behrens-Fisher problem. Statist. Probab. Lett. 77(1), 1–8 (2007).

Selvaraju R R, Cogswell M, Das A, et al. Grad-cam: Visual explanations from deep networks via gradient-based localization. In: Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision. 618–626. (2017).

Sun, N. et al. Deep spatial-temporal feature fusion for facial expression recognition in static images. Pattern Recogn. Lett. 119, 49–61 (2019).

Rajaraman, S. et al. Iteratively pruned deep learning ensembles for COVID-19 detection in chest X-rays. IEEE Access 8, 115041–115050 (2020).

Szegedy C, Ioffe S, Vanhoucke V, et al. Inception-v4, inception-resnet and the impact of residual connections on learning. In: Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence. 31(1). (2017).

Xie S, Girshick R, Dollár P, et al. Aggregated residual transformations for deep neural networks. In: Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition. 1492–1500. (2017).

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge Kaggle and Github for providing their platforms and contributors for uploading their meaningful datasets. We would like to highly thank Cohen et al., Kermany et al., Rahman et al., DarwinAI Canada, and the Vision and Image Processing Research Group at the University of Waterloo for the data.

Funding

This work was supported by Research Anhui Provincial Major Science and Technology Project (Grant No. 201903a07020013), New Generation of Information Technology Innovation Project (Grant No. 2019ITA01010), National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 52374177), Medical Special Cultivation Project of Anhui University of Science and Technology (Grant No. YZ2023H2C004), the Scientific Research Foundation for High-level Talents of Anhui University of Science and Technology (Grant No. 2022yjrc43), and the Graduate Innovation Fund Project of Anhui University of Science and Technology (Grant No.2022CX1007).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MZ and LG conceived the study. LG and MZ developed the method. LG and KB built the hardware platform and software platform. LG implemented the algorithms. LG, NW, and HW validated and analyzed the results. MZ supervised the study. LG wrote the original draft. MZ reviewed and edited the manuscript. LG, KB, YC, and SL saved the data. All authors read and approved the final manuscript and content of the work.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhou, M., Gao, L., Bian, K. et al. Pulmonary diseases accurate recognition using adaptive multiscale feature fusion in chest radiography. Sci Rep 15, 29243 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-13479-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-13479-1