Abstract

Road traffic accidents are one of the leading death causes around the globe, claiming millions of lives every year. Predicting traffic accident severity is essential for road users’ safety and accident prevention. Artificial neural network (ANN), Boosted trees (BRT), Support vector machine (SVM), Naïve Bayes (NVB), and logistic regression (LGR) were employed for predicting fatal accidents in 14 cities in the Eastern Province of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia using accident data from the year 2018–2022. The accident data was classified into fatal and injury accidents. A total of 9,548 accident cases involving 17,100 vehicles resulting in 2,527 fatalities and 8,020 injuries during this period, with 28% of the cases occurring in Al-Ahsa. The ANN model outperformed all five models with an accuracy = 99.91%, sensitivity = 99.94%, specificity = 99.8%, G-mean = 99.87%, and AUC = 99.92%. The ANN could improve the performance of LGR by up to 13.60% in the validation phase. For understanding the impact of each of the input parameters, three different relevance-ranking algorithms (maximum relevance minimum redundancy, Kruskal Wallis and Chi-square) were used prior to the development of the models and the result shows the number of people involved and the number of people injured as the major factors increasing the severity of road traffic accidents.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Road traffic accidents result in the loss of millions of lives annually. As reported by the World Health Organization, these incidents cause approximately 1.35 million deaths worldwide each year and leave around 50 million individuals injured1. Thus, road accidents have become a prevalent determinant of death. About 518 billion dollars are lost annually as a result of such accidents. Consequently, several people become disabled, losing their body parts2. These types of accidents account for the third most significant cause of death in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, through which 4.3% of the country’s GDP is lost3. Kingdom Saudi Arabia has a road traffic accident fatality index 25, higher than other Gulf nations4.

A road traffic accident is a complex problem that is caused by several factors like the road infrastructure (pavement condition, road furniture); road user behavior (speeding, crossing roads at non-crossing roads); traffic conditions (e.g., delays and congestion); vehicle factor (e.g., tire burst, brake failure) and environmental factors (e.g., inclement weather condition). About 90% of fatal accidents are due to drivers’ behavior, such as speeding, traffic rule violations, distractions, and defiance of traffic control devices.

Models designed to predict road traffic accidents play a crucial role in enhancing road safety by uncovering underlying causes and guiding preventive actions. Although various regression-based and empirical approaches have been proposed over time, they often struggle with limited accuracy, largely due to the inherent complexity and variability of traffic accident scenarios5. These models aim to figure out possible reasons for the accidents and the number of times they occur in a given area within some time. Also, models are formulated for surveying the efficacy of the policies enacted to prevent road accidents. Moreover, the outcome from these models is utilized in deciding better alternatives to curving the accidents6.

Recently, machine learning techniques such as Naïve Bayes (NVB), artificial neural network (ANN), support vector machine (SVM), Random Forest (RF), Regression trees (CART), decision trees (DT), K-nearest neighbor (KNN), etc., have gained the attention of scientist in modeling and solving complex problems like traffic accident predictions. For example, Zhu et al. (2018) used the ANN and RF model to investigate driver injury patterns in Washington State. The study found that driver impairment, distractions, truck usage, lack of restraints, swerve driving, and darkness were major factors informing the enormity of the injury sustained.

Literature review

Delen et al.7 the ANN model to determine the accident severity level with causative factors in the United States. The study found the combination of multiple causative factors responsible for accident severity rather than just one factor. The major causative factors found in the study were lack of restraints, drug influence, vehicle type, driver age, and gender. Umar and Gokcekus (2019) compared the performance of the ANN model and classical linear regression in predicting the severity of road traffic accidents in Nigeria. The ANN model outperformed the regression model by 18.7% and 2.5% for fatality and injury models, respectively8. ANN classifiers developed by Alkheder et al. to model the accident severity of 5,973 traffic accidents in Abu Dhabi from 2008 to 2018 showed a reasonable prediction ability9. Kibar et al.10 compared the efficiency of ANN and the negative binomial regression model for analyzing truck accidents on divided roads in Turkey using accident data from 2008–2011. The ANN outperformed negative binomial regression with higher regression values and lower error values.

Chen and Antoniou11 compared the performance of NVB, KNN, SVM, DT, RF, and deep and shallow neural network models in classifying accident severity using the sensitivity, specificity, and area under the curve as performance metrics. The study finds NVB to be the most efficient model. The performance of a deep neural network developed for predicting traffic accidents using accident data of non-urban road sections was compared to that of gene expression programming (GEP) and random effect negative binomial (RENB) models. The deep neural network outperformed the two models with a correlation coefficient of 0.945 and an RMSE value of 5.90812.

By considering accident contributing factors, Obasi and Benson5 used four machine learning models to predict the severity level of road traffic accidents using United Kingdom accident data from 2005–2014. The study found that the Logistic regression model outperformed NVB and ANN with 7% accuracy. RF model beat all three models with an accuracy of 87%. The study also found vehicle engine capacity, vehicle age and make, driver’s age, road class, and daytime as the most significant factors contributing to accident severity. Ahmed et al.6 used New Zealand traffic accident data from 2016 to 2020 to compare the performance of several machine learning techniques (RF, Decision Jungle, Categorical Boosting, Adaptive Boosting, Extreme Gradient Boosting, and Light Gradient Boosting Machine) for the prediction of accident severity. RF was the most robust model, with an accuracy of 81.45% and an F1-score of 81.04%. The study also found that road category and number of vehicles involved significantly affect the accident’s severity. Gatera et al.13 developed a short-term model for predicting road traffic accidents in Rwanda using RF and SVM models. The models were appraised by deploying four performance evaluation metrics: mean absolute error (MAE), root mean square error (RMSE), mean square error (MSE), and coefficient of determination. The RF model predicted the accident more accurately than the SVM model. Sun et al.14 used a hybrid RF model to explore the most significant factors influencing the injury severity of vulnerable road users in the accidents in which they were involved. The study found that the involvement of the older vulnerable group, trucks in crashes, increases fatality risk. The study also found that crashes occurring in autumn and winter, as well as crashes occurring in rural areas and primary and secondary roads, are associated with a higher risk of fatality. Driver impairment, distractions, truck usage, lack of restraints, swerve driving, and darkness were among the significant factors affecting the pattern and severity of injury accidents in Washington state15.

Looking into the literature, it can be seen that several machine-learning techniques have been used for predicting accident severity, but the “no free lunch” theorem states that there is no single model that proved to be best for all situations and, therefore, exploring different comparative models could help get the best outcome. While machine-learning models have been applied to accident severity prediction globally, their application in Saudi Arabia particularly with robust feature selection methods to handle high-dimensional traffic accident data is limited. The study aims to develop several machine-learning models for predicting the severity of road traffic accidents in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia to find an optimum model for the case study area. The study’s primary motive is to employ three different dominant input selection algorithms for selecting the input parameters responsible for accident severity in the study area. Dominant input selection controls the effect of these machine-learning models in increasing the accuracy of accident severity prediction models. This will assist in making decisions on the effectiveness of the single models in improving the accident severity prediction. To the authors’ knowledge, this study is the first to utilize the three feature selection algorithms (Kruskal Wallis, Chi-square and maximum relevance minimum redundancy algorithms) for selecting relevant input parameters prior to machine learning technique models for predicting accident severity.

Materials and method

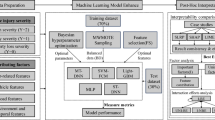

Proposed methodology

The study’s methodology involves two significant steps and is presented in Fig. 1. The first step is selecting dominant parameters and ranking their relevance in the model. The second stage is developing five machine learning-based (BRT, ANN, SVM, NVB, and logistic regression (LGR)) models for predicting traffic accident severity. All the steps are explained in the following sub-sections.

Data

Traffic accident data from the years 2018 to 2022, covering 14 cities in the Eastern Province of Saudi Arabia, were used for this study. A total of 9,548 accident cases involving 17,100 vehicles resulted in 2,527 fatalities and 8,020 injuries during this period. These data were obtained from the General Directorate of Traffic (Ministry of Interior, Saudi Arabia), based on official accident records from police departments in 14 cities in the Eastern Province7. The accidents were categorized into 19 distinct types, and the corresponding figures for cases, injuries, vehicles involved, and fatalities are presented in Table 1.

Grouping the accident types into so many groups aids in a comprehensive and clear understanding of the problem such that prevention measures can be applied easily. The moving vehicle accident was the most recorded accident type (3,665 cases), accounting for 3,272 injuries and 871 fatalities. The second and third most common accident types in the study area are vehicle overturns and run-over accidents, which have killed 640 and 503 people, respectively. The number of people injured from vehicle overturns and runover accidents was 1,809 and 1,794 people, respectively. Waste container accidents, bridge falls, and hit traffic light accidents were the least recorded accident types in the study area. The waste container and hit-traffic light accident recorded zero fatalities, while bridge fall accidents killed two people.

Table 2 provides the summary of 39 causative factors in the study area. Swerve, distracted driving, pedestrians crossing outside crossing areas, and spacing violations were the four major causes of accidents on the selected roads between 2018–2022. Swerve driving accounts for 28.1% of the accidents, while distracted driving, crossing outside specified areas, and spacing violation accounts for 18.8%, 10.2%, and 9.5% of the accidents, respectively. Swerve driving killed more people (765 people) than any other reason, followed by distracted driving, which claimed 453 lives, and the failure of pedestrians to cross at specified locations, which killed 255 people. The only causative factors with zero fatalities are related to pedestrian behaviors, which include “violation of traffic light by pedestrians and playing in the street. Downhill accidents and short-headway also resulted in zero fatal accidents. Steering failure, overload, and Electrical faults resulted in 1 fatality each. It is worth noting that all the causative factors with the least fatality cases have a lower frequency.

As shown in Table 3, 14 cities in the Kingdom of Saudia Arabia were selected for conducting the study. The results show that 28% (2,664) of the recorded accident cases during these five years occurred in Al-Ahsa. 18% (1,758) in Dammam, 13% (1,196) in Hafar Al-Batin, and 10% (917) in Qatif, and the remaining 32% took place in the remaining ten cities. The fatalities in these cities are also very high, recording 718, 339, 302, 238, and 163 fatalities in Al Ahsa, Hafar Al-Batin, Dammam, AL Jubail, and Dhahran, respectively. Looking at the ratio of accidents to fatalities. It can be seen that the city of Al Jubail has the highest fatality/accident ratio of 0.56, which translates to at least 1 person killed for every 2 accident cases in the recorded data. The Kafji and Buqayp cities also have a high ratio that translates to almost a fatality for every 2 accident cases. The cities of Aladid, Ras Tanura, and Dhahran recorded a fatality in every 3 accident cases. 5. In the cities of Hafar, Al Batin, King Fahad Causeway, Al Ahsa, Qaryat al-Ulya, and Al Nairyah, a fatality is recorded in every four accident cases, while fatality is recorded in every five accident cases reported in the cities of Al Khobar and Dammam. The lowest fatality/ accident ratio (0.16) was reported in Qatif.

The data summary based on the accident year is given in Table 4. There were more accidents, fatalities, and injuries in 2019 than in the remaining years. There was a sharp decline in the number of accidents, injuries, and fatalities in 2020, which may be attributed to restricted movement during the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic. As some restrictions were relaxed in 2022, the number of accidents significantly increased compared to 2020 (Full restrictions) and 2021 (partial restrictions). Even though the number of accidents has increased from 2022 up to 2022, the severity ratio (number of fatality/number of cases) continues to decrease slightly from 2018 (0.27) to 2022 (0.24).

Feature selection and ranking of parameters

The selection of dominant input parameters is crucial in any machine learning modeling. This helps develop a model capable of reaching global minima with the optimum resources of time and money. Including non-relevant parameters in machine learning models increases the complexity of the model, thus decreasing its efficiency16,17. It is important to apply at least two different selection techniques to understand the relevant parameters better. This is because no single model gives the best selection for all scenarios18. In this study, three different algorithms were used for ranking the relevance and importance of all the potential input parameters (No. of vehicle involved in an accident, accident type, cause of the accident, No. of injured people, No. of people involved in the accident, accident city, location of the accident). The algorithms used are maximum relevance, minimum redundancy (MRMR), Chi-square, and the Kruskall Wallis. The MRMR is one of the most powerful filter algorithms developed by (Peng et al. 2005). Its major advantage over other techniques lies in its ability to select only one relevant feature when there are two or more relevant features with the same information, leading to fast computational speed and accurate prediction (Ibrahim Bibi Farouk et al. 2022). Kruskal Wallis on other hand is a non-parametric test that removes some parameters with p-value above the set p-value threshold effectively removing non-relevant parameters hence improved performance of the models. The ranking of the parameters using MRMR, Chi-square, and the Kruskal Wallis is given in Figs. 2, 3, and 4, respectively. No. Of vehicle involved, city, and No. of injured people are the most critical three parameters for predicting accident severity, and accident cause was the least essential parameter using the MRMR algorithm. Ranking with the Chi-square algorithms ranked No. of injured people, No. of vehicle involved and city as the most critical parameters in the following order of importance. Chi-square ranked No. of vehicles involved as the last parameter. Likewise, the number of people involved in an accident, No. of injured people and whether the accidents occurred in or out of the city are the most critical parameters using the Kruskal Wallis algorithm, as shown in Fig. 4. Since the three different algorithms did not rank the seven parameters in the same order, all seven parameters were included to avoid ignoring any critical parameter. The correlation matrix between the parameters is presented in Table 5. The correlation matrix gives the correlation between the parameters. Knowing the correlation between the parameters will help eliminate collinearity issues in the model by removing one of two parameters with a very high correlation in a single model. The correlation matrix shows that no two input parameters have a strong relationship. Therefore, including all seven parameters will not cause any collinearity issues in the model. No. of people involved in accidents is the most critical parameter considering the three ranking algorithms and correlation matrix. The results also show that the relationship between the input parameters and the accident’s severity is not linear, as all parameters have a slight correlation with accident severity except No of people involved in the accident (CC = 0.8782).

Artificial intelligence techniques

SVM algorithm

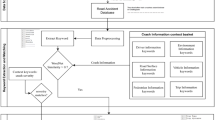

Support Vector Machine (SVM) is widely recognized in the field of machine learning for its effectiveness in managing uncertain and complex data structures19. It is primarily used to construct an optimal separating boundary, known as a hyperplane, that distinguishes between different classes within a dataset. The technique aims to maximize the margin—the distance between the hyperplane and the closest data points from each class, called support vectors—which enhances the model’s generalization ability and reduces classification errors20. In this study, the SVM model is applied using Eq. 2, as illustrated in Fig. 5.

where w is the weight vector of the orthogonal hyperplane, x represents the input in the dataset, and b is the bisector, which ∅ denotes the null set in the dataset. The study’s proposed SVM algorithm is shown in Fig. 5.

Artificial neural networks (ANN)

Artificial neural networks (ANN) are one of the most widely employed machine learning techniques, drawing inspiration from the intricate neural networks in the human brain21. Among the various types of ANNs, feedforward neural networks are ubiquitous. They transmit the processed weight values of each artificial neuron as output to the subsequent layer, relying on inputs from neurons in the preceding layer. Within the category of feedforward neural networks, the Multilayer Perceptron (MLP) holds a significant position22. For training MLP, the backpropagation algorithm stands out as the most frequently employed technique. It operates by adjusting the weights between neurons to minimize errors. This model excels in learning patterns and demonstrates adaptability to new data values. However, it is worth noting that this system may exhibit slow convergence and the potential for reaching local optima compared to EANN23. This research proposed a “Feed-forward neural networks” (FFNN) algorithm consisting of 7 input parameters, 10 neurons in the hidden layer, and one output layer, as shown in Fig. 6.

Boosted regression trees (BRT)

The problem is categorized using Boosted Regression Trees (BRT). The Classification and Regression Trees (CART) have dual decision grading aggregates. Each point (node) shows a kind of dual (binary) on a single framework (parameter); while a branch shows the result, the last points (leaf nodes) represent the data category. CART functions by dividing the data into two categories so that the categories on each point (node) are similar and choosing the most suitable framework (parameter). Then each area is applied successively, as shown in Fig. 7, and so on. If there are examples from n classes in dataset A, \(gini\) index, \(gini \left(A\right)\) is defined as;

where the relative frequency of class \(j\) in A is \(p_{j}\)24. Datasets A is separated into two smaller subsets, A1 and A2, with s sizes N1 and N2; the split data \(gini the\) index contains examples of n groups, then the \(gini\) index,\(gini \left(A\right)\) is defined as:

Boosted Regression Trees (BRT) systematically evaluate single-variable splits, selecting the attribute that minimizes the Gini index \({gini}_{split}\left(A\right)\) to determine the optimal node division. The model grows the tree recursively from the root, and once fully expanded, it undergoes a pruning process to remove unnecessary branches and reduce overfitting. One of the key advantages of decision trees lies in their interpretability—each path from the root to a leaf node can be translated into a clear "if–then" rule, making the decision-making process transparent and easy to follow.

Naïve Bayes

Naive Bayes is a probabilistic classification technique commonly applied to tasks like text categorization. It operates under the simplifying assumption that the features used for prediction are statistically independent, an assumption that often does not hold in practical scenarios. The method is based on Bayes’ theorem, which calculates the likelihood of an outcome based on prior knowledge of related conditions or events25.

Logistic regression

Binary logistic regression is employed to assess the influence of various factors on road accidents when the outcome variable is dichotomous. In logistic regression, the explanatory variables may be either categorical or continuous26. For this study, all independent variables are categorical, while the response variable Y, indicating whether an accident is fatal or not, is binary. This justifies the use of binary logistic regression as an appropriate modeling technique. The formulation of the logistic regression model is presented in Eq. 4.

p is the probability of a fatal accident, b0 is the intercept, bi is the model coefficients of the independent variables, and xi is the independent variable.

Data processing and performance evaluation

Data preparation is one of the most important activities for any black box modeling. Normalization is one of the important activities before the model formulation. The normalization brings all the different data parameters into a similar range. Normalizing the data means no parameter will overshadow another due to higher or lower range variation, in addition to eliminating the overshadowing problem. Normalization reduces the model’s complexity and helps achieve the global minima with fewer resources, time, and cost27. The data was normalized between 0 and 1 using Eq. 5.

In this context, xnorm refers to the normalized value, calculated using the observed minimum and maximum values x, xmax, and xmin, respectively. To evaluate the performance of the developed models, five key metrics were applied: accuracy, sensitivity, specificity, precision, and geometric mean (G-mean), as outlined in Equations 6-10. Collectively, these measures provide a comprehensive understanding of each model’s effectiveness.

Accuracy reflects the overall correctness of the model’s predictions; however, it may present a misleading picture, particularly when the dataset is imbalanced. In such cases, the majority class may dominate the accuracy score, masking poor performance on the minority class28. Sensitivity, or recall, quantifies the model’s ability to correctly identify true positives—typically the minority class—while specificity gauges its accuracy in recognizing true negatives, which often represent the majority class. These two metrics are often in tension, requiring careful balancing in evaluation.

Precision indicates the proportion of correct positive predictions among all predicted positives and is particularly important when false positives carry significant cost. A model with high precision is more reliable in its positive classifications.

The G-mean serves as a balanced indicator by taking the square root of the product of sensitivity and specificity. A high G-mean value suggests that the model performs well across both classes, whereas a low G-mean indicates disproportionate classification performance. This metric is especially valuable in imbalanced datasets, helping to detect and avoid tendencies toward overfitting to the dominant class or underfitting to the minority. The G-mean parameter is the best metric for comparing the performance of different models. The evaluation was achieved by using additional statistical measures, namely, True positive (TP), true negative (TN), false positive (FP), and false negative (FN). A true positive (TP) occurs when the model accurately predicts a fatal accident as fatal. A false positive (FP) arises when the model mistakenly labels a non-fatal accident as fatal. Conversely, a false negative (FN) happens when a fatal accident is wrongly classified as non-fatal. Lastly, a true negative (TN) is recorded when the model correctly identifies a non-fatal accident as non-fatal.

Results of the AI models

Four Intelligent machine-learning models, namely ANN, SVM, NVB, and boosted ensemble trees, were used to model the accident severity in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, and for analogy, LGR was additionally employed to model the accident severity. The models were developed using the MATLAB (2023a) classification learner toolbox. A hyperparameter tuning process was performed for each advanced machine learning model using Bayesian optimization to identify the most effective model configuration. This study reports only the performance outcomes of these optimized models. The range of hyperparameters explored during the optimization is detailed in Table 6. The optimum ANN model was developed using a one-layer neural network with 10 neurons in the hidden layer using a rectified linear unit (ReLU) activation function and lamda value of 0.1 at 500 epoch. The optimum SVM model was obtained using a Gaussian kernel and kernel scale of 0.66 at box constraint 1. The NVB model was also optimized using a Gaussian kernel with a positive support. In contrast, the best boosted ensemble trees model was found using a random under-sampling (RUS) ensemble method with a maximum of 20 splits and 30 learners at a 0.1 learning rate. The performance of the models in the validation phase stages was evaluated using the five statistical evaluation metrics, and the result is presented in Table 7. The confusion matrix of all the models is also shown in Fig. 8. A k-fold validation technique was used for the model’s validation. The 90% data was utilized for training and validation by diving the data into 10-folds while the remaining 10% that was used neither in training nor in validation of the model was used for testing the developed model. The evaluation metrics evaluate the overall accuracy of each classifier, efficacy in classifying negative values using specificity measure, effectiveness in classifying positive values using sensitivity metric, and the overall precision of the models. In addition, the G-mean was employed in the models’ evaluation to ensure that the models do not experience overfitting of negative cases and underfitting of positive cases.

Discussions

All the intelligent machine-learning models demonstrated very high accuracy in modeling the severity of the traffic accident with accuracy and precision values > 0.9. This is due to the robustness of the intelligent machine learning models in learning and mapping patterns in the data. The ANN model classifies the accident severity with higher accuracy in comparison to the other models in terms of its overall accuracy (accuracy = 99.91%), ability to correctly classify fatal accidents (sensitivity = 99.94%), proficiency to correctly classify non-fatal (injury) accidents (specificity = 99.8%). The high G-mean value of the ANN model shows that the model could reliably predict accident severity without overfitting or underfitting problems. The ANN model outperformed BRT, NVB, and SVM models by 5.3%, 6.45%, and 0.66%, respectively, concerning the model’s collective precision. The ANN model also has higher stability than the other models as its performance in sensitivity and specificity is almost the same, with a difference of only 0.14%. It has demonstrated a high precision in classifying Fatal and non-fatal accident cases. The models have shown their suitability in modeling the severity of road accidents in the following order: ANN > SVM > NVB > BRT > LGR. The high classification accuracy of fatal accidents by the ANN model is corroborated by a study conducted by Sarkar and Sarkar29 where ANN predicted a fatality rate of 96.15% accuracy. The nonlinearity and complexity of the data gives the ANN model higher performance ability over the SVM and NVB due its adaptability and flexibility in handling nonlinear data and ability to learn complex patterns faster. However, BRT has a higher accuracy (94.69%) than NVB (93.54%). The NVB was considered a better model, considering its stability based on the G-mean and precision values.

The modeling results were further compared with the classical model (LGR) and it can be seen that all the intelligent machine-learning models performed better than the LGR model. In the validation phase, the BRT, ANN, NVB, and SVM outperformed the LGR by 8.38%, 13.68%, 7.23%, and 13.02%, respectively. The LGR recorded high sensitivity but low specificity, making it unsuitable for predicting accident severity.

The receiver operating characteristics (ROC) curve was also used to visualize the performance of the models graphically. ROC curve plots actual positive rates (Y-axis) against false positive rates (X-axis). The Area Under the Curve (AUC) for classification models typically falls between 0.5 and 1. An ideal model achieves an AUC of 1, indicating flawless distinction between classes, while an AUC below 0.5 suggests the model performs worse than random guessing. The closer the AUC is to 1, the better the model is at distinguishing between true and false outcomes30. It is observable from Fig. 9 that all the intelligent machine learning methods have an AUC value > 0.9, which shows their robustness in classifying fatal and fatal accidents. The LGR, on the other hand, also classifies fatal and non-fatal accidents with reasonable accuracy (AUC = 0.8921).

Shapley additive explanation (SHAP) was used for the interpretability of the best classification model (ANN). The Shapley values are based on game theory, which considers every parameter as a player and the prediction as the prize in machine learning. Given that each parameter aided the final prediction, the Shapley values denote each parameter’s contribution. The SHAP values help to understand how each parameter contributes to predicting the accident severity. It also enables researchers to understand the direction of the parameter’s influence on the accident severity (positive/negative), which cannot be seen in the traditional feature relevance importance techniques. A feature with a positive Shapley value contributes positively to the final prediction, while a negative value indicates a downward influence on the outcome. The greater the Shapley value, the more significant the feature’s impact. In SHAP analysis, each feature’s importance is determined based on its individual marginal contribution to the prediction result31. The Shapley value plots in Fig. 10 represent the average impact of each parameter on the output magnitude. The Figure shows the number of people involved, Injury, place where the accident occurred (in or out of the city), the city where the accident occurred, and accident type as the most critical parameters with higher average impact and magnitude. The number of people involved has mean absolute Shapley values of 0.34, the Injury has 0.13, the in/out of the city has 0.06, city has 0.03, the accident type, the accident reason, and the vehicle count has 0.002.

The findings of this study were supported by other studies in the literature6,32.The comparison was based on the accuracy metric of the classification models. The random forest model performed better than decision jungle, DT, AdaBoost, extreme gradient boosting (XGBoost), and L-GBM in predicting accident severity with an accuracy of 81.45%6. A hybrid model integrating the Boruta Algorithm with four machine learning models (K-NN, XGBoost, NVB, and binary logistic regression) for analysis of injury accidents was evaluated using four evaluation metrics. The XGBoost classified the injury accident with the highest accuracy of 82%33. RF model outperformed the NVB and ANN models in predicting the severity of injury accidents with an overall accuracy of 87%5. SVR, BRT, and NVB predicted the severity of injury accidents with 92–98% accuracy. RF, decision tree, and Instance-Based learning with parameter k model the severity of injury in a motorcycle crash with an accuracy of 73.91%, 73.64%, and 73.71%, respectively34. The severity of road traffic injury modeled using three deep learning approaches provided the highest accuracy of 73.5% in 3.4535. Comparing the performance accuracy of four machine learning techniques (FNN, SVM, FNN-FCM, and SVM-FCM) for the prediction of crash injury severity revealed higher accuracy of the SVM-FCM model with an accuracy rating of 74.6%36. Comparing the performance accuracy of the previous studies with the current research. It can be seen that the proposed ANN model predicted the accident with higher prediction accuracy (99.91%). The careful selection of the present study’s input parameters helps obtain high prediction accuracy.

Conclusion

The study evaluates the severity of road traffic accidents in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia using five years of data from 14 cities. Distracted driving was found to be the primary cause of accidents, while accidents involving moving vehicles were the primary accident type recorded during the study period. 28% (2,664) of the documented accident cases during these five years occurred in Al-Ahsa. 18% (1,758) in Dammam, 13% (1,196) in Hafar Al-Batin, and 10% (917) in Qatif, and the remaining 32% took place in the remaining ten cities. Trends in the accident data show that the accident rate has dropped during the coronavirus pandemic and has increased since 2020. Ranking the relevance and importance of the potential input parameters using the three algorithms (MRMR, Chi2, and Kruskal Wallis) shows the number of people involved in an accident, the number of people injured, and the city where the accident took place in the major factors contributing to accident severity. The machine learning techniques predict the accident severity in the order of ANN > SVM > NVB > BRT > LGR. The ANN model predicts fatal accidents more accurately than NVB, BRT, SVM, and LGR regarding accuracy, precision, specificity, G-mean, and AUC metrics. SHAP analysis helped overcome the black box nature of machine learning techniques by showing how each parameter influences accident prediction. The machine learning models proved to be more reliable in predicting fatal accidents in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia and could be utilized by the relevant authorities. However, developing a hybrid model that combines different models’ meticulous and unique features could be employed in feature studies for improved modeling performance. The major constraint of the proposed methodology is the data quality, as poor data quality might lead to poor results.

Data availability

Data sets generated during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

World Health Organization. Global Status Report on Road Safety (2019).

Sohail, A., Cheema, M. A., Ali, M. E., Toosi, A. N. & Rakha, H. A. Data-driven approaches for road safety: A comprehensive systematic literature review. Saf. Sci. 158, 105949. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssci.2022.105949 (2023).

Mohamed, H. A. Estimation of Socio-Economic Cost of Road Accidents in Saudi Arabia: Willingness-To-Pay Approach (WTP) (Scienpress Ltd, 2015).

Al-Ahmadi, H. M. Analysis of traffic accidents in Saudi Arabia: Safety effectiveness evaluation of SAHER enforcement system. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 48(4), 5493–5506. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13369-022-07473-2 (2023).

Obasi, I. C. & Benson, C. Evaluating the effectiveness of machine learning techniques in forecasting the severity of traffic accidents. Heliyon 9, e18812. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e18812 (2023).

Ahmed, S., Hossain, M. A., Ray, S. K., Bhuiyan, M. M. I. & Sabuj, S. R. A study on road accident prediction and contributing factors using explainable machine learning models: analysis and performance. Transp. Res. Interdiscip. Perspect. 19, 100814. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trip.2023.100814 (2023).

General Directorate of Traffic. Traffic accident records for 14 cities in the Eastern Province (2018–2022) [Unpublished raw data]. Ministry of Interior, Saudi Arabia (2023).

Umar, I. K. & Gokcekus, H. Modeling severity of road traffic accident in Nigeria using artificial neural network. J. Kejuruter. 32(2), 221–227. https://doi.org/10.17576/jkukm-2019-31(2)-06 (2019).

Alkheder, S., Taamneh, M. & Taamneh, S. Severity prediction of traffic accident using an artificial neural network. J. Forecast. 36(1), 100–108. https://doi.org/10.1002/for.2425 (2016).

Ture Kibar, F., Celik, F. & Wegman, F. Analyzing truck accident data on the interurban road Ankara–Aksaray–Eregli in Turkey: Comparing the performances of negative binomial regression and the artificial neural networks models. J. Transp. Saf. Secur. 11, 129–149. https://doi.org/10.1080/19439962.2017.1363841 (2019).

Theofilatos, A., Chen, C. & Antoniou, C. Comparing machine learning and deep learning methods for real-time crash prediction. Transp. Res. Rec. 2673(8), 169–178 (2019).

Singh, G., Pal, M., Yadav, Y. & Singla, T. Deep neural network-based predictive modeling of road accidents. Neural Comput. Appl. 32(16), 12417–12426. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00521-019-04695-8 (2020).

Gatera, A., Kuradusenge, M., Bajpai, G., Mikeka, C. & Shrivastava, S. Comparison of random forest and support vector machine regression models for forecasting road accidents. Sci. Afr. 21, e01739. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sciaf.2023.e01739 (2023).

Sun, Z. et al. A hybrid approach of random forest and random parameters logit model of injury severity modeling of vulnerable road users involved crashes. Accid. Anal. Prev. 192, 107235. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aap.2023.107235 (2023).

Zhu, M., Li, Y. & Wang, Y. Design and experiment verification of a novel analysis framework for recognition of driver injury patterns: From a multi-class classification perspective. Accid. Anal. Prev. 120, 152–164 (2018).

Umar, I. K., Gökçekuş, H. & Nourani, V. An intelligent soft computing technique for prediction of vehicular traffic noise. Arab. J. Geosci. 15, 1571. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12517-022-10858-0 (2022).

Umar, I. K., Nourani, V. & Gokcekus, H. A novel multi-model data-driven ensemble approach for the prediction of particulate matter concentration. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 28, 49663–49677 (2021).

Umar, İK. & Yahya, M. N. Modelling the PM2.5 concentration with artificial intelligence-based ensemble approach. Trak. Univ. J. Nat. Sci. 23(2), 153–165. https://doi.org/10.23902/trkjnat.1062091 (2022).

Wang, W., Xu, D., Chau, K. & Chen, S. Improved annual rainfall-runoff forecasting using PSO–SVM model based on EEMD. J. Hydroinf. 15(4), 1377–1390. https://doi.org/10.2166/hydro.2013.134 (2015).

Fan, J. et al. Evaluation of SVM, ELM and four tree-based ensemble models for predicting daily reference evapotranspiration using limited meteorological data in different climates of China. Agric. For. Meteorol. 263, 225–241. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agrformet.2018.08.019 (2018).

Genaro, N., Torija, A. J., Requena, I. & Ruiz, D. P. A neural network based model for urban noise prediction. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 128(4), 1738–1746. https://doi.org/10.1121/1.3473692 (2010).

Ghaffari, A. et al. Performance comparison of neural network training algorithms in modeling of bimodal drug delivery. Int. J. Pharm. 327, 126–138. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpharm.2006.07.056 (2006).

Khouban, L. et al. Combination of artificial neural networks and genetic algorithm-gamma test method in prediction of road traffic noise. Environ. Eng. Manag. J. 14(4), 801–808. https://doi.org/10.30638/eemj.2015.089 (2015).

Elith, J., Leathwick, J. R. & Hastie, T. A working guide to boosted regression trees. J. Anim. Ecol. 77(4), 802–813. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2656.2008.01390.x (2008).

Gao, H., Zeng, X. & Yao, C. Application of improved distributed naive Bayesian algorithms in text classification. J. Supercomput. 75(9), 5831–5847. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11227-019-02862-1 (2019).

Umar, I. K. & Bashir, S. Investigation of the factors contributing to truck driver’s involvement in an injury accident. Pamukkale Univ. J. Eng. Sci. 1–7. https://doi.org/10.5505/pajes.2019.65391 (2019).

Nourani, V., Gökçekus, H., Umar, I. K. & Najafi, H. An emotional artificial neural network for prediction of vehicular traffic noise. Sci. Total Environ. 707, 136134. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.136134 (2020).

Parikh, R., Mathai, A., Parikh, S., Sekhar, G. C. & Thomas, R. Understanding and using sensitivity, specificity and predictive values. Indian J. Ophthalmol. 56(1), 45 (2008).

Sarkar, A. & Sarkar, S. Comparative assessment between statistical and soft computing methods for accident severity classification. J. Inst. Eng. India Ser. A 101, 27–40. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40030-019-00422-7 (2020).

Kaur, H. & Kumari, V. Predictive modelling and analytics for diabetes using a machine learning approach. Appl. Comput. Inform. 18(1–2), 90–100. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aci.2018.12.004 (2022).

Lundberg, S. & Lee, S.-I. A unified approach to interpreting model predictions. Available: http://arxiv.org/abs/1705.07874 (2017).

Zhang, Y., Zhao, H., Li, Y., Long, Y. & Liang, W. Predicting highly dynamic traffic noise using rotating mobile monitoring and machine learning method. Environ. Res. 229, 115896. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2023.115896 (2023).

Zhang, S., Khattak, A., Matara, C. M., Hussain, A. & Farooq, A. Hybrid feature selection-based machine learning Classification system for the prediction of injury severity in single and multiple-vehicle accidents. PLoS ONE 17, e0262941. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0262941 (2022).

Wahab, L. & Jiang, H. A comparative study on machine learning based algorithms for prediction of motorcycle crash severity. PLoS ONE 14, e0214966. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0214966 (2019).

Sattar, K. et al. Transparent deep machine learning framework for predicting traffic crash severity. Neural Comput. Appl. 35, 1535–1547. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00521-022-07769-2 (2023).

Assi, K., Rahman, S. M., Mansoor, U. & Ratrout, N. Predicting crash injury severity with machine learning algorithm synergized with clustering technique: A promising protocol. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 17(15), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17155497 (2020).

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by the Deanship of Graduate Studies and Scientific Research at JOUF University under grant No. (DGSSR-2024-02-02041).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

F.A., M.A.O., and I.K.U. conceptualized the study and designed the methodology. I.K.U. conducted data collection, preprocessing, and analysis. F.A., A.M.Y., and M.A.O. provided expertise in machine learning modeling and result interpretation. All authors contributed to manuscript writing, review, and approval of the final version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Alanazi, F., Umar, I.K., Yosri, A.M. et al. Comparative evaluation of deep learning and traditional models for predicting traffic accident severity in Saudi Arabia. Sci Rep 15, 32568 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-13484-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-13484-4