Abstract

Protein aggregation is one of the key challenges in the biopharmaceutical industry as its control is crucial in achieving long-term stability and efficacy of biopharmaceuticals. Attempts have been made to develop regression models for predicting the aggregation of monoclonal antibodies in solution using machine learning methods. These efforts have yielded varying levels of success, with current state-of-the-art AI approaches achieving good prediction accuracies (\(r=0.86\)). Here, we demonstrate the prediction of aggregation rate in monoclonal antibodies with beyond state-of-the-art reliability using a coupled AI-MD-Molecular surface curvature modelling platform. The scientific novelty of this approach lies in using local geometrical surface curvature of proteins as the core element for protein stability analysis. By combining local surface curvature and hydrophobicity, as derived from time-dependent MD simulations, we are able to construct aggregation predictive features that, when coupled with linear regression machine learning techniques, give a high prediction accuracy (\(r=0.91\)) on a dataset of 20 molecules. More generally, this approach shows significant potential for quantitative in silico screening and prediction of protein aggregation, which is of great scientific and industrial relevance, particularly in biopharmaceutics.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Protein aggregation is crucial in the development of biotherapeutic formulations, as it affects the stability and safety of biological drugs1,2,3,4. Especially, understanding protein aggregation at the structural level is vital for selecting the right molecular candidates and for formulating safe and stable biological drugs5. Moreover, protein aggregation also plays a pivotal role in designing drug delivery systems that prioritize the needs of patients. Finally, the biopharmaceutical industry’s shift towards high-concentration antibody formulations for subcutaneous administration also requires strong control and understanding of protein aggregation6,7.

The protein’s three-dimensional structure is linked to its function. Experimental methods such as X-ray crystallography, NMR and cryo-electron microscopy are today strong approaches for obtaining protein structures8,9. In parallel, computational methods for protein structure prediction are being developed with increasing accuracy and are emerging as possible fast and cost effective alternatives10,11,12. Major current computational tools include AlphaFold13, RoseTTAFold14, OmegaFold15 and ESMFold16. Due to the structural fluctuations that naturally occur in proteins, and are commonly responsible for their diverse biological functionality, a single calculated structure of a protein is often insufficient for their understanding. Molecular dynamics simulations offer a profound complementary tool to the AI methodologies17,18 as they enable the study of the complex motion of proteins at the atomic level over time and according to exact dynamic equations19,20. This dynamic perspective allows studying phenomena such as protein folding21, protein-ligand binding22, thermal stability of antibodies23 and more.

An emerging strategy for studying the degradation of biopharmaceuticals involves describing therapeutic protein properties using designated molecular descriptors and surface features24,25,26,27,28 which reduce the dimensionality of structural and physico-chemical variables while retaining essential information. Descriptors can be sequence-based, such as the frequency of distinct motifs of individual amino acids in the chain29, amino-acid charge, secondary structure, etc.30. However, these sequence-based descriptors do not capture various relevant structural-based mechanisms of protein aggregation and thus structure-based molecular descriptors are better suited for predicting aggregation31,32. For example, the solvent-accessible surface area (SASA) is an indicator of interaction surface and spatial aggregation propensity (SAP25) identifies aggregation-prone regions. SAP is often combined with net charge into the Developability Index (DI)26, which is a composite metric that considers solubility to predict aggregation. The spatial charge map (SCM24) is based on the partial charge of solvent-exposed atoms and accounts for electrostatic interactions that underlie viscosity. It has been utilized to accurately rank high-concentration mAb solution viscosities across various industrial pipelines24,33. Another descriptor uses fine-grained points and patches on the solvent accessible surface, on which physico-chemical properties are then projected and optimized against a test dataset34. Finally, recent attempts use multiple descriptors as coupled via machine learning algorithms to predict the aggregation rates of high-concentration mAb solutions35,36.

Here, we develop a predictive experimentally-informed AI and MD modelling platform for aggregation of monoclonal antibodies in biopharmaceutical formulations, of direct relevance for fundamental science and industrial applicability. Specifically, the prediction platform rather uniquely combines a coupled series of state-of-the-art methodologies (AlphaFold \(\rightarrow\) Molecular dynamics \(\rightarrow\) Protein features calculation \(\rightarrow\) Experimentally informed ML) to predict the aggregation rate of mAbs from the amino-acid sequence. The platform is validated on publicly available experimental data of 20 mAb proteins, obtaining excellent prediction accuracy with predicted to experimental correlation coefficient of \(r=0.91\). The core scientific novelty is the recognition of local protein surface curvature, introduced as a special geometrical surface feature (molecular descriptor), which in combination with hydrophobicity we show strongly correlates with the protein aggregation rate. Finally, this work is discussed in the context of its applicability in the biopharmaceutical industry.

Results

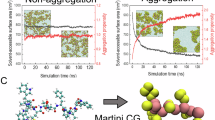

The prediction of monoclonal antibody protein aggregation from molecular structure is based on our developed AI-MD-Molecular surface curvature modelling platform, schematically presented in Fig. 1 (for methodology see also Methods). The modelling platform starts from the amino acid sequence of a given monoclonal antibody. Using this sequence, we then use AlphaFold13 to construct the 3D structure of the variable fragment (Fv) for each monoclonal antibody (note that in principle the approach could also be applied to other protein types). Next, to access the dynamics of proteins and the improved structure in the formulation, we used the AlphaFold-determined structure as input for molecular dynamics (MD) simulations (using the Gromacs package), generating a 100 ns trajectory for each antibody fragment. We then calculated selected surface features for each frame of the molecular dynamics simulation trajectory. Statistically significant surface features were identified and utilized to design machine learning models. We train our learning algorithms using leave-one-out cross-validation analysis on the experimentally measured dataset of 20 mAb aggregation rates (see Methods for details) reported in Ref.35. Specifically, this aggregation rate dataset is focused on high concentration mAb solutions as today used in biopharmaceutical formulations and is distinguished from the more prevalent low concentration datasets (e.g.37).

AI-MD-Molecular surface curvature modelling platform for monoclonal antibody aggregation rate prediction. Using the amino acid sequence, we construct a 3D antibody structure, employ it in a molecular dynamics simulation, calculate surface features for all frames, and then use this data to build a machine learning model for predicting antibody aggregation rates.

Novel features based on molecular surface curvature

We introduce a new protein surface feature, based on the physico-chemical and geometric aspects of the molecular surface, designed to evaluate aggregation propensity. Initially, we establish an equidistant mesh of points on the solvent-accessible surface. For each of these points, we compute the electrostatic potential and a smoothed projection of atom hydrophobicities, as explained in Methods, outlining the surface’s physico-chemical profile. These are further divided into separate positive and negative contributions. We then consider how the relative orientation and accessibility of these points on the interaction surface affect the protein association in a solution. For instance, if a point resides in a highly concave region of a protein, its interaction with an associating protein would be minimal, despite its solvent accessibility. To capture this, we calculate the principal curvatures at each point and employ the framework by Koenderick and Doorn38 (depicted in Fig. 2), utilizing the concept of shape index (s) and curvedness (c) (see Methods for details). Specifically, the shape index characterizes the overall shape of the surface around a point, distinguishing between protrusions, hyperbolic saddles, or cavities, whereas the curvedness gauges the intensity of that particular shape in each point.

Local geometrical surface curvature for protein stability analysis. (A) Shape index - s and (B) curvedness - c, visualized for a test mAb. (C) Heat maps of penalty functions \(P_1\), \(P_2\) and \(P_3\), for different values of s and c (top), and these same penalty functions visualized on a specific tested mAb (bottom).

To define a feature that also accounts for local surface shape, on all surface points, we introduce three distinct phenomenologically motivated penalty functions (\(P_1, P_2, P_3\)):

each corresponding to a distinct protein-protein interaction regime (Fig. 2).

Penalty function \(P_1\) assumes that highly curved areas are more likely to be involved in protein-protein interactions, highlighting the accessibility of these regions. For instance, an atom situated at the end of a long exposed amino acid side-chain, such as Arginine, is prone to contact and interact with other proteins in a solution due to its high curvedness, and, notably, the positive charge of \(C_{\zeta }\) atom at physiological pH.

Penalty function \(P_2\) assumes that flatter, but still outward curved regions, are also prone to interaction, offering a more energetically favorable fit. \(P_2\) assumes that protrusions with high curvedness may come into contact but at the cost of the surrounding atoms which implies a less complementary shape with the surface of other proteins, relying primarily on the strength of the most exposed atom. Differently, flatter regions are more likely to exhibit a cumulative effect of containing atoms, resulting in a stronger interaction.

Penalty function \(P_3\) employs a sigmoid-type function, assuming that positively and outward curved regions, showing a plateau with increasing s and c, are more likely to be involved in protein-protein interactions than negatively curved regions. Similar to \(P_2\), \(P_3\) highlights the importance of a somewhat flat region, with similar penalization for both positive and negative shape index s at \(c=0\). For protrusions, a non-linear rise in the penalization occurs with \(P_3\), reaching a plateau value.

For each surface point, we explore three distinct cut-offs, corresponding to effective surface patch sizes, over which the average shape index and curvedness are computed. We consider values of 1 Å, 5 Å and 10 Å, where 1 Å captures the effect of about one atom, 5 Å describes the impact of a single amino acid, while 10 Å describes that amino acid and its closest neighboring amino acids.

Features are calculated from the evolution of the protein structure in time, as captured by MD simulations. Specifically, when calculating a quantity, we use its average value, i.e. the ensemble or time average of the instantaneous value across all potential states. Also, we consider the maximum, minimum, and the overall variance of the considered quantity, as we later show also determines whether a protein is likely to aggregate, capturing the reaction limiting effects of extreme states.

Finally, we define the distinct feature F as a combination of all described factors:

where A is the protein region we calculate the feature over, such as complementarity-determining region (CDR) and Fv, \(\phi\) is the physico-chemical property (such as hydrophobicity and electrostatic potential) and P is the penalty function (\(P_1, P_2, P_3\)) at a given cut-off. The overview of constructing the features is outlined in Fig. 3. Given that the Fv region is the most variable part in our dataset samples, we compute the features independently for the entire Fv region and each of the CDRs (L1, L2, L3 in the light chain and H1, H2, H3 in the heavy chain), as well as the whole CDR region. Fv region with one of the features is visualized for all mAbs in Fig. 4, where we name the curvature-dependent features ECM (Electrostatic Curvature Map) and HCM (Hydrophobic Curvature Map), respectively.

Spatial visualization of a selected feature for aggregation prediction. Specifically, we show LogP hydrophobicity combined with \(P_3\) penalty function (selected from the best performing ML model in Table 1), visualized for all considered monoclonal antibodies.

Prediction of aggregation rate

We apply regression-based machine learning models on the computed final features F to predict the aggregation rate for 20 monoclonal antibodies in the considered database. We consider only features that correlate strongly with the aggregation rate (Pearson’s r \(>0.4\); c. \(\simeq 40\) best features are identified). We train the machine learning models on all possible combinations of three features, which proves to improve the accuracy of prediction in comparison to using just one or two features. To verify the approach we use leave-one-out cross-validation (LOOCV) to assure no overfitting occurs (see Methods).

The best performing machine learning models according to Pearson’s correlation factor r are shown in Fig. 5 and listed in Table 1. The highest correlation factor is \(r=0.91\), which to the best of our knowledge is better than any existing state-of-the-art35,36. The highest coefficient of determination \(R^2=0.82\), and lowest mean squared error \(\text {MSE}=0.03\) are achieved by using a linear regression model based on three features. All three features are based on the positive part of the hydrophobicity (MLP, see Methods) with atomic based Wildman-Crippen scale. Feature 1 includes \(P_3\) penalty function, 10 Å cut-off, and is computed as a MD time average on the CDRH1 region. Feature 2 includes \(P_2\) penalty function, 5 Å cut-off, and is computed on the CDRH1 region as a maximum value during the MD simulation. Feature 3 includes \(P_3\) penalty function, 1 Å cut-off, and is computed on the CDRH1 region as a minimum value during the MD simulation. Other feature combinations and regression models also achieve correlation values above 0.78 (Table 1) with notably the best feature combinations including different hydrophobicity based metrics and only one feature in Table 1 describing the electrostatic potential. Visual inspection of Fig. 5 suggests that four data points with high experimental aggregation rates deviate significantly from the mean. To assess the robustness of our results, we recalculated the relevant performance metrics after excluding these points and observed an equivalent relative ranking of the models.

Prediction of monoclonal antibodies aggregation with our AI-MD-Molecular surface curvature modelling platform. Experimental vs predicted aggregation rates for: (A) best performing ML model - Linear regression and the corresponding residuals plot, (B) K-nearest neighbours, (C) Support vector machine, (D) Random forest and (E) Gradient boosting. All aggregation rates are given in units of ml/mg per week. Residuals in (A) are calculated as difference between experimental and predicted aggregation rate.

Permutation analysis is performed to show that overfitting in our ML model performance is minimal (see Table 2). Here we randomly permute the order of aggregation rates for all antibodies and see how the models perform after training. As the degree of permutation (correlation between the original and permuted aggregation rate vector) decreases, goodness-of-fit should decrease as well, and indeed, as shown in Fig. 6, the models perform consistently worse for lower degrees of permutation compared to the high ones. The calculated metrics for both the entire dataset (in-sample) and the leave-one-out cross-validation (LOOCV) dataset (out-of-sample) are given in Table 2. Finally, these results confirm that our approach avoids overfitting and appropriately captures a meaningful amount of variation in the original dataset, also in line with the PCA analysis (see Supplementary Fig. S1).

Permutation analysis of aggregation rate prediction. (A) In-sample and (B) out-of-sample coefficients of determination - \(\hbox{$\mathit{R}^2$}\) for linear regression models are plotted for different permuted vector correlations. We use the three features combination from the best performing linear regression model in Table 1. Degree of permutation equal to 1 corresponds to the original experimental data, shown in red, while values approaching 0 or becoming negative indicate increasing levels of randomization (see Methods).

Discussion

Use of protein structure surface features is emerging as a potent approach for designing targeted drugs with fewer side effects and improved stability. In this work, we present an experimentally informed prediction of the aggregation rate of monoclonal antibodies, with prediction accuracy of 91% for a dataset of 20 mAbs under standard platform formulation conditions. Especially, we demonstrate the importance of local protein surface curvature in the surface feature construction, which in combination with hydrophobicity we show strongly correlates with the aggregation rate. Using molecular dynamics modelling, following AlphaFold structure prediction, is also shown to be important for achieving high prediction accuracy by providing core structural dynamics information into the surface feature construction. The prediction performance is further validated with leave-one-out cross-validation.

More specifically, our analysis of the top-performing ML models (Table 1) reveals interesting insights into the effects influencing protein aggregation. While electrostatic potential, incorporated in our work by the ECM feature, has been previously associated with solution behavior, mutual orientation, and viscosity24,39,40, our findings suggest may have less direct role in the aggregation than initially thought. It is believed that the aggregation process is primarily driven by the partial or complete unfolding of certain protein states41, which subsequently leads to non-specific associations due to exposed hydrophobic regions. Although pH-induced charge imbalances can potentially destabilize protein structures, such occurrences are statistically uncommon under the formulation conditions present in our dataset. Our results indicate that hydrophobic interactions, quantified through the HCM feature, play a more significant role in protein-protein interactions and subsequent aggregation. To further corroborate this, we performed ridge regression (L2 regularization) using the full set of input features. The resulting model highlighted the same key contributors (see Supplementary Fig. S2), all of which are either hydrophobicity based or related to surface area properties. Together, this suggests that the close proximity of two proteins, primarily mediated by hydrophobic regions, is -for the studied protein formulations- a key factor in initiating the destabilization process.

We have observed that the best machine learning algorithm we used was linear regression, as compared to other more complex algorithms (Table 1). In the training process, we use composite features that primarily describe charge and hydrophobicity, both effects which significantly influence a protein’s local geometry. For example, highly hydrophobic regions on a protein’s surface tend to avoid water, often burying themselves within the protein’s interior while still being partially exposed. These regions might not play a crucial role in protein-protein interactions, suggesting that an increase in surface hydrophobicity does not necessarily correlate linearly with a higher aggregation propensity. In contrast, our penalty functions account for this by selectively including only specific hydrophobic surfaces in the feature calculation. This selective approach enables us to detect a more accurate linear relationship between aggregation rates and spatially exposed hydrophobic surfaces, thereby enhancing the fit of our linear regression model.

The weak unfolding during our 100 ns MD simulation indicates we mainly describe native aggregation - the reversible association of native monomers42 which also aligns with the experimental temperatures (\(45^{\circ }\)C)35 and typical mAb melting (\(T_{\text {m}}\)) and aggregation onset (\(T_{\text {agg}}\)) temperatures, usually above \(75^{\circ }\)C43. While rare unfolding occurs at storage temperatures (\(5^{\circ }\)C), many aggregates can be reversible oligomers, supporting our algorithm’s predictions. Our conformational sampling is limited by computational constraints, as 100 ns mAb simulations take about a day on standard GPU clusters, while characteristic backbone fluctuations occur in microseconds44. Nevertheless, this proves to be a long enough time for the correlation between the relevant calculated features and the aggregation rate to converge and provide meaningful insight (see Supplementary Fig. S3). Future work could employ enhanced sampling techniques like metadynamics45 or parallel tempering46 to improve modeling.

Finally, this work is fully inline with the challenge of developing general in-silico aggregation prediction models of proteins, as of direct relevance for the industrial biopharmaceutical drug and formulation development processes. The ability to predict aggregation facilitates precise molecule design, enabling targeted drug development with reduced side effects47. In formulation development, it also guides the creation of stable formulations with optimized delivery systems, extending shelf life and allowing for higher drug concentrations at low viscosity. More generally, the ability to predict protein aggregation with high precision contributes to the patient-friendly administration of biopharmaceutical drugs by reducing injection volumes, enhancing convenience, and supporting home use48.

Methods

Structure calculation with AlphaFold and molecular dynamics

The amino acid sequences of the 20 monoclonal antibodies were used to construct the 3D structure of the Fv region of each antibody using AlphaFold13. The obtained Fv structure was used as the inintial condition for molecular dynamics simulation, which was performed using GROMACS molecular dynamics package49 with the OPLS-AA force field50. The antibody fragment was placed in a simulation box extending at least 2 nm beyond the antibody in all directions and the box was filled with explicit solvent molecules using the SPC/E water model51. The system pH was set at 6.0 using PROPKA352 and ions were added to the simulation box to ensure a neutral environment. Energy minimization of the system was done with the steepest descent algorithm. The system was first equilibrated through successive NVT and NPT ensemble simulation runs for a joint duration of 10 ns. This was followed by a 100 ns production run which was performed in the NPT ensemble at 298 K and the pressure of 1 bar. The integration time step was set at 2 fs, resulting in 5000 frames for each antibody fragment.

Surface features

We calculate the introduced novel surface features using an in-house developed scrypt in Python 3.10. The electrostatic potential on the surface is calculated with Delphi software53, using the OPLS-AA forcefield, which provides a framework for solving the Poisson-Boltzmann equation

where \(\epsilon\) is the dielectric constant (80 for bulk water and 4 for protein interiors54, \(\phi\) the electrostatic potential, \(k_B\) the Boltzmann constant, T the temperature and \(\rho ({\textbf {r}})\) the spatial charge density. \(c_i\) and \(q_i\) denote the concentration and charge of ions, respectively, and \(Q_j\) represents the charge of protein atoms.

We project normalized atom hydrophobicities onto the surface points using the concept of Molecular Lipophilicity Potential (MLP)55, defined as

where MLP is the sum of nearby atoms’ normalized hydrophobicities \(f_i\), with \(p_i\) representing the weights of the contributions and g being a Fermi type distance function, with parameters defined by the range of the hydrophobic effect. We assign the hydrophobicity using two top contending hydrophobicity scales, based on their correlation to HIC (hydrophobic interaction chromatography) measurements56. These are the amino acid based Wimley-White scale57 and the atomic based Wildman-Crippen scale58.

The definition and triangulation of surface points are performed using MSMS software59. For each point, we extract coordinates, normal vector components, and information about nearest neighbors based on triangulation. Principal curvatures \(\kappa _1\) and \(\kappa _2\) at each point are then computed using the algorithm proposed by Hamann60. Subsequently, shape index (s) and curvedness (c)38 are calculated using these principal curvatures as

and averaged over nearby surface points, employing different cutoffs based on Euclidean distance. The whole feature building procedure is shown in Fig. 3.

Also, we calculate different known classification features used in literature35,36 to allow for comparison. For example, our implementation of SASA involves evenly distributing points on the surface using the Fibonacci sphere and counting solvent-accessible points, according to the Shrake-Rupley (“rolling probe”) algorithm61. Partial charges for SCM calculation are assigned and extracted through GROMACS as part of the MD simulation process. In our SAP implementation, we use the Wimley-White and the Wildman-Crippen scale, same as mentioned earlier.

Dataset of relevant mAbs and aggregation rates

We train our learning algorithms on the experimentally measured dataset of 20 mAb aggregation rates, as selected also in Ref.35 (Bevacizumab was excluded due to its aggregation rate value beyond 3 standard deviations from the mean and therefore outside the data behaviour ML models can effectively capture62). The aggregation rate was measured at pharmaceutically relevant high mAb concentration of \(\text {c} = 150\,\text {mg/mL}\) at \(40^\circ \text {C}\) and at pH 6.0. Out of the 20 mAbs considered, 4 show aggregation rate higher than \(0.8\cdot 10^{-4}\,\frac{\text {mL}}{\text {mg week}}\), which makes them less suitable for long-term storage and distribution typically required in biopharmaceutical applications. Each of the considered mAbs is FDA approved and has a published amino acid sequence.

Machine learning prediction of aggregation rate

The aggregation rate dataset is used to train the algorithm and validate its results. We test several regression models including Linear regression, K-nearest neighbours, Support vector machine, Random forest and Gradient boosting. Note, that Neural networks are not used due to a small size of the available dataset.

We employ the leave-one-out cross-validation (LOOCV) technique which enables us to systematically test and identify the most effective model. Note, that LOOCV approach addresses dataset imbalances more effectively than the conventional train-test split, where certain classes may be underrepresented in the training set, impacting optimal predictions in the test set. LOOCV also allows the entire dataset to be used as the test set.

To streamline our analysis, we initially narrow down the feature space by selecting only those features exhibiting a significant correlation with the aggregation rate (Pearson’s r \(\ge\) 0.4 and p-value < 0.05). As an additional filter, we exclude all features where values for any of the mAbs deviate by more than 3 standard deviations from the mean. Subsequently, we explore all possible three feature combinations, training separate models for each combination. The top combinations are determined based on their correlation between predicted and experimental aggregation rates (Pearson’s r), coefficient of determination (\(\hbox{$\mathit{R}^2$}\)), and mean square error (MSE).

In permutation analysis we take the experimental aggregation rate vector of all 20 monoclonal antibodies and generate 100 aggregation rate vectors with randomly permuted values. The degree of permutation is defined as the correlation coefficient (Pearson’s r) between the original and the permuted aggregation rate vector. For each of the generated aggregation rate vectors, we train the model independently using the same features as with the unpermuted aggregation rate vector. We then record the in-sample coefficient of determination (\(\hbox{$\mathit{R}^2$}\)), calculated using a model trained on the full dataset, as well as the out-of-sample \(\hbox{$\mathit{R}^2$}\), obtained via LOOCV by evaluating the model on the held-out and predicted values. This allows us to assess both the fit and generalization accuracy of the model.

Data availability

Data are available from the authors upon reasonable request.

References

Pham, N. B. & Meng, W. S. Protein aggregation and immunogenicity of biotherapeutics. Int. J. Pharmaceutics 585, 119523 (2020).

Schmidt, T., Bergner, A. & Schwede, T. Modelling three-dimensional protein structures for applications in drug design. Drug Discov. Today 19, 890–897 (2014).

Kumar, S., Plotnikov, N. V., Rouse, J. C. & Singh, S. K. Biopharmaceutical informatics: Supporting biologic drug development via molecular modelling and informatics. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 70, 595–608 (2018).

Hebditch, M. Computational Modelling Approaches for Studying Protein-Protein and Protein-Solvent Interactions in Biopharmaceuticals (The University of Manchester, 2018).

Houben, B., Rousseau, F. & Schymkowitz, J. Protein structure and aggregation: A marriage of necessity ruled by aggregation gatekeepers. Trends Biochem. Sci. 47, 194–205 (2022).

Fathallah, A. M. et al. The effect of small oligomeric protein aggregates on the immunogenicity of intravenous and subcutaneous administered antibodies. J. Pharmaceutical Sci. 104, 3691–3702 (2015).

Turner, M. R. & Balu-Iyer, S. V. Challenges and opportunities for the subcutaneous delivery of therapeutic proteins. J. Pharmaceutical Sci. 107, 1247–1260 (2018).

Pakhrin, S. C., Shrestha, B., Adhikari, B. & KC, D. B. Deep learning-based advances in protein structure prediction. Int. J. Mol. Sci. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms22115553 (2021).

Jisna, V. A. & Jayaraj, P. B. Protein structure prediction: Conventional and deep learning perspectives. Protein J. 40, 522–544. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10930-021-10003-y (2021).

Pearce, R. & Zhang, Y. Toward the solution of the protein structure prediction problem. J. Biol. Chem. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbc.2021.100870 (2021).

Bongirwar, V. & Mokhade, A. S. Different methods, techniques and their limitations in protein structure prediction: A review. Progress Biophys. Mol. Biol. 173, 72–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pbiomolbio.2022.05.002 (2022).

Bertoline, L. M. F., Lima, A. N., Krieger, J. E. & Teixeira, S. K. Before and after alphafold2: An overview of protein structure prediction. Front. Bioinform. https://doi.org/10.3389/fbinf.2023.1120370 (2023).

Jumper, J. et al. Highly accurate protein structure prediction with alphafold. Nature 596, 583–589. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-021-03819-2 (2021).

Baek, M. et al. Accurate prediction of protein structures and interactions using a three-track neural network. Science 373, 871–876. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abj8754 (2021).

Wu, R. et al. High-resolution de novo structure prediction from primary sequence. bioRxiv. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.07.21.500999 (2022).

Lin, Z. et al. Evolutionary-scale prediction of atomic-level protein structure with a language model. Science 379, 1123–1130. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.ade2574 (2023).

Garrido-Rodríguez, P. et al. Analysis of alphafold and molecular dynamics structure predictions of mutations in serpins. bioRxiv. 2023–01 (2023).

Guo, H.-B. et al. Alphafold2 modeling and molecular dynamics simulations of an intrinsically disordered protein. Plos One 19, e0301866 (2024).

Shukla, R. & Tripathi, T. Molecular Dynamics Simulation of Protein and Protein–Ligand Complexes, 133–161 (Springer Singapore, 2020).

Lazim, R., Suh, D. & Choi, S. Advances in molecular dynamics simulations and enhanced sampling methods for the study of protein systems. Int. J. Mol. Sci. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms21176339 (2020).

Miao, Y., Feixas, F., Eun, C. & McCammon, J. A. Accelerated molecular dynamics simulations of protein folding. J. Comput. Chem. 36, 1536–1549. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcc.23964 (2015).

Guterres, H. & Im, W. Improving protein-ligand docking results with high-throughput molecular dynamics simulations. J. Chem. Inform. Model. 60, 2189–2198. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jcim.0c00057 (2020).

Bekker, G., Ma, B. & Kamiya, N. Thermal stability of single-domain antibodies estimated by molecular dynamics simulations. Protein Sci. 28, 429–438. https://doi.org/10.1002/pro.3546 (2019).

Agrawal, N. J. et al. Computational tool for the early screening of monoclonal antibodies for their viscosities.. mAbs 8, 43–48. https://doi.org/10.1080/19420862.2015.1099773 (2016).

Chennamsetty, N., Voynov, V., Kayser, V., Helk, B. & Trout, B. L. Prediction of aggregation prone regions of therapeutic proteins. J. Phys. Chem. B 114, 6614–6624. https://doi.org/10.1021/jp911706q (2010).

Lai, P. K. et al. Differences in human igg1 and igg4 s228p monoclonal antibodies viscosity and self-interactions: Experimental assessment and computational predictions of domain interactions. mAbs. https://doi.org/10.1080/19420862.2021.1991256 (2021).

Zambrano, R. et al. Aggrescan3d (a3d): Server for prediction of aggregation properties of protein structures. Nucleic Acids Res. 43, W306–W313. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkv359 (2015).

Sormanni, P., Aprile, F. A. & Vendruscolo, M. The camsol method of rational design of protein mutants with enhanced solubility. J. Mol. Biol. 427, 478–490 (2015).

Conchillo-Solé, O. et al. Aggrescan: A server for the prediction and evaluation of“ hot spots’’ of aggregation in polypeptides. BMC Bioinform. 8, 1–17 (2007).

Família, C., Dennison, S. R., Quintas, A. & Phoenix, D. A. Prediction of peptide and protein propensity for amyloid formation. PloS One 10, e0134679 (2015).

Fang, Y., Gao, S., Tai, D., Middaugh, C. R. & Fang, J. Identification of properties important to protein aggregation using feature selection. BMC Bioinform. 14, 1–9 (2013).

Tanaka, M. & Komi, Y. Layers of structure and function in protein aggregation. Nat. Chem. Biol. 11, 373–377 (2015).

Lai, P.-K. et al. Differences in human igg1 and igg4 s228p monoclonal antibodies viscosity and self-interactions: Experimental assessment and computational predictions of domain interactions. MAbs 13, 1991256 (2021) (Taylor & Francis).

Sankar, K., Krystek, S. R., Carl, S. M., Day, T. & Maier, J. K. Aggscore: Prediction of aggregation-prone regions in proteins based on the distribution of surface patches. Proteins Struct. Function Bioinform. 86, 1147–1156. https://doi.org/10.1002/prot.25594 (2018).

Lai, P. K. et al. Machine learning feature selection for predicting high concentration therapeutic antibody aggregation. J. Pharmaceutical Sci. 110, 1583–1591. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.xphs.2020.12.014 (2021).

Lai, P. K., Gallegos, A., Mody, N., Sathish, H. A. & Trout, B. L. Machine learning prediction of antibody aggregation and viscosity for high concentration formulation development of protein therapeutics. mAbs. https://doi.org/10.1080/19420862.2022.2026208 (2022).

Zarzar, J. et al. High concentration formulation developability approaches and considerations. MAbs 15, 2211185 (2023) (Taylor & Francis).

Koenderink, J. J. & van Doorn, A. J. Surface shape and curvature scales. Image Vision Computing 10, 557–564. https://doi.org/10.1016/0262-8856(92)90076-F (1992).

Zidar, M., Rozman, P., Belko-Parkel, K. & Ravnik, M. Control of viscosity in biopharmaceutical protein formulations. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 580, 308–317 (2020).

Nichols, P. et al. Rational design of viscosity reducing mutants of a monoclonal antibody: Hydrophobic versus electrostatic inter-molecular interactions. MAbs 7, 212–230 (2015) (Taylor & Francis).

Famm, K., Hansen, L., Christ, D. & Winter, G. Thermodynamically stable aggregation-resistant antibody domains through directed evolution. J. Mol. Biol. 376, 926–931 (2008).

Philo, J. S. & Arakawa, T. Mechanisms of protein aggregation. Curr. Pharmaceutical Biotechnol. 10, 348–351 (2009).

Sert, F. et al. Temperature and ph-dependent behaviors of mab drugs: A case study for trastuzumab. Scientia Pharmaceutica. https://doi.org/10.3390/scipharm90010021 (2022).

Shaw, D. E. et al. Atomic-level characterization of the structural dynamics of proteins. Science 330, 341–346 (2010).

Laio, A. & Parrinello, M. Escaping free-energy minima. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 99, 12562–12566 (2002).

Sugita, Y. & Okamoto, Y. Replica-exchange molecular dynamics method for protein folding. Chem. Phys. Lett. 314, 141–151 (1999).

Astier, A. Importance of the determination of the higher order structure in the in-use stability studies of biopharmaceuticals. Generics Biosimilars Initiative J. 9, 49–51 (2020).

Narayanan, H. et al. Machine learning for biologics: Opportunities for protein engineering, developability, and formulation. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 42, 151–165 (2021).

Abraham, M. J. et al. Gromacs: High performance molecular simulations through multi-level parallelism from laptops to supercomputers. SoftwareX 1–2, 19–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.softx.2015.06.001 (2015).

Jorgensen, W. L., Maxwell, D. S. & Tirado-Rives, J. Development and testing of the opls all-atom force field on conformational energetics and properties of organic liquids. J. Am. Chem. Society 118, 11225–11236. https://doi.org/10.1021/ja9621760 (1996).

Berendsen, H. J. C., Grigera, J. R. & Straatsma, T. P. The missing term in effective pair potentials. J. Phys. Chem. 91, 6269–6271. https://doi.org/10.1021/j100308a038 (1987).

Olsson, M. H. M., Søndergaard, C. R., Rostkowski, M. & Jensen, J. H. Propka3: Consistent treatment of internal and surface residues in empirical p<i>k</i><sub>a</sub> predictions. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 7, 525–537. https://doi.org/10.1021/ct100578z (2011).

Li, C. et al. Delphi suite: New developments and review of functionalities. J. Comput. Chem. 40, 2502–2508. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcc.26006 (2019).

Li, L., Li, C., Zhang, Z. & Alexov, E. On the dielectric “constant’’ of proteins: Smooth dielectric function for macromolecular modeling and its implementation in delphi. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 9, 2126–2136 (2013).

Heiden, W., Moeckel, G. & Brickmann, J. A new approach to analysis and display of local lipophilicity/hydrophilicity mapped on molecular surfaces. J. Computer-Aided Mol. Design 7, 503–514. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00124359 (1993).

Waibl, F. et al. Comparison of hydrophobicity scales for predicting biophysical properties of antibodies. Front. Mol. Biosci. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmolb.2022.960194 (2022).

Wimley, W. C. & White, S. H. Experimentally determined hydrophobicity scale for proteins at membrane interfaces. Nat. Struct. Biol. 3, 842–848 (1996).

Wildman, S. A. & Crippen, G. M. Prediction of physicochemical parameters by atomic contributions. J. Chem. Inform. Computer Sci. 39, 868–873 (1999).

Sanner, M. F., Olson, A. J. & Spehner, J.-C. Reduced surface: an efficient way to compute molecular surfaces. Biopolymers 38, 305–320 (1996).

Hamann, B. Curvature Approximation for Triangulated Surfaces (1993).

Shrake, A. & Rupley, J. A. Environment and exposure to solvent of protein atoms, lysozyme and insulin. J. Mol. Biol. 79, 351–371 (1973).

Brownlee, J. Data Preparation for Machine Learning: Data Cleaning, Feature Selection, and Data Transforms in Python (Machine Learning Mastery, 2020).

Acknowledgements

This work has been supported by the Slovenian Research and Innovation Agency (Grants P1-0099 and J1-50006) and the European Research Council under the Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Program of the European Union (Program agreement 884928-LOGOS). B.K and M.R. acknowledge funding from Novarits LLC under contract MA-7683-2022.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

B.K. and L.E. performed numerical simulations. B.K., L.E. and Z.K. analysed the results. B.K. developed the curvature based surface features. M.R. and D.K. supervised and led the research. All authors contributed to the preparation of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Knez, B., Erzin, L., Kos, Ž. et al. Prediction of aggregation in monoclonal antibodies from molecular surface curvature. Sci Rep 15, 28266 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-13527-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-13527-w