Abstract

It is to develop a predictive model utilizing machine learning techniques to promptly identify patients with diabetic foot ulcers (DFU) who may require major amputation upon their initial admission. A total of 598 DFU patients were admitted to a tertiary hospital in Beijing. We employed synthetic minority oversampling technique to address the class imbalance of the target variable in the original dataset. A Lasso regularization analysis identified 17 feature variables for inclusion in the model: age, diabetes duration, wound size, history of peripheral neuropathy, history of atrial fibrillation, white blood cell count, C-reactive protein (CRP), procalcitonin, glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c), myoglobin (Mb), troponin (Tn), blood urea nitrogen, serum albumin, triglycerides (TG), low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, multidrug-resistant infection, vascular intervention. Subsequently, risk prediction models were independently developed by using these feature variables based on six machine learning algorithms: logistic regression, random forest, support vector machine, K-nearest neighbors, gradient boosting machine (GBM), and extreme gradient boosting (XGBoost). The performance of six models was evaluated to select the best model for predicting the risk of major amputation. GBM was identified as the best predictive model (accuracy 0.9408, precision 0.9855, recall 0.8553, F1-score 0.9158, and AUC 0.9499). This model also highlights the importance ranking of feature variables associated with predicting the risk of major amputation, with the top five variables being the presence of multidrug-resistant infection, CRP, diabetes duration, Tn, age. It is an effective machine learning method that GBM model is used to predict the risk of major amputations in diabetic foot patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Diabetic foot ulcer (DFU) is one of the most life-threatening complications of diabetes mellitus, with an estimated lifetime incidence of approximately 25% among diabetic patients1. Among those affected, 14–24% may progress to severe infection, gangrene, or require lower extremity amputation2. Timely and accurate prediction of amputation risk is therefore of paramount importance for optimizing clinical management, preserving limb function, and improving patient survival3,4. DFU-related amputations are broadly categorized into major and minor types. Major amputations, such as above-knee or below-knee procedures, result in substantial loss of mobility, increased dependence on caregivers, psychological distress, and a markedly elevated five-year mortality rate5.

With the increasing availability of electronic health records and the advancement of computational techniques, machine learning (ML) algorithms have emerged as powerful tools for clinical risk prediction and decision support6. Unlike traditional statistical approaches, ML models can capture complex, nonlinear interactions among high-dimensional clinical variables7,8,9. Currently, commonly employed predictive models for clinical risk assessment include logistic regression, random forest, support vector machine (SVM), K-nearest neighbors (KNN), gradient boosting machine (GBM), and extreme gradient boosting (XGBoost). While these machine learning (ML) algorithms have demonstrated potential in various biomedical applications, their performance is frequently limited by the paucity of high-quality, large-scale datasets8. In practical scenarios, the selection of an appropriate algorithm is highly dependent on the characteristics of the dataset and the specific decision-making objectives. Moreover, the majority of previous studies have relied on a single ML algorithm, thereby limiting their ability to identify the most optimal and robust predictive model for a given clinical task10.

To address these limitations and improve predictive reliability, our study systematically constructed and compared six distinct ML models—logistic regression, random forest, SVM, KNN, GBM, and XGBoost—for the prediction of lower limb major amputation risk in patients with diabetic foot ulcers. This comparative approach aims to identify the most effective algorithm under the current data constraints, thereby providing a comprehensive foundation for clinical decision support and individualized risk stratification.

Methods

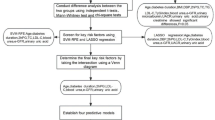

The overall study design and data screening process are illustrated in Fig. 1. The following sections detail the key methodological components of this study, including: Study Design and Population Characteristics, Data Preprocessing, Variable Selection for Model Training, Model Construction, and Model Evaluation.

Study design and population characteristics

This study was conducted in accordance with the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki and the Good Clinical Practice (GCP) guidelines of the International Conference on Harmonisation (ICH). Ethical approval was obtained from the Ethics Committee of Beijing Shijitan Hospital, Capital Medical University (Approval No. IIT2025-049-001). As a retrospective analysis based on anonymized clinical data, the study was granted an exemption from the requirement for informed consent by the Institutional Review Board (Ethics Committee of Beijing Shijitan Hospital, Capital Medical University).

Patients with diabetic foot ulcer (DFU) who were admitted to Beijing Shijitan Hospital, Capital Medical University, between January 2015 and December 2024 were randomly selected for inclusion in this study. Patients were excluded if they died during hospitalization, underwent amputation prior to transfer to Beijing Shijitan Hospital, sought treatment at other medical institutions during their hospital stay, or had incomplete clinical information (cases with missing values identified in the dataset). Clinical data for all eligible participants were extracted from the electronic health records (EHRs) of the hospital. The collected information included demographic characteristics, relevant medical history, initial laboratory test results upon admission, wound assessment parameters, status of multidrug-resistant organism (MDRO) infection, whether vascular intervention was performed, and final clinical outcome (major amputation or not).

Data preprocessing

The original dataset focuses exclusively on structured clinical and laboratory data for diabetic foot ulcer patients, and no text mining or relational information extraction was performed. All data used in this study were pre-defined, structured features such as demographic variables, laboratory indicators, and clinical outcomes, with irrelevant or noisy entries excluded during the initial data cleaning and preprocessing stages. Based on clinical practice, international guidelines from the International Working Group on the Diabetic Foot (IWGDF), and a comprehensive literature review, we initially screened candidate variables for inclusion. Further selection was conducted according to the availability and completeness of data within the EHRs, ensuring data integrity and no missing values to support robust statistical analysis and model performance. The original dataset was confirmed to be complete, with no missing values; hence, input data cleaning for incomplete records was not required.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 27.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Categorical variables were expressed as frequencies and percentages [n (%)], while continuous variables were presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD).

Variable selection for model training

Variable selection was performed using the Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator (LASSO) regression implemented in the glmnet package in R 4.1.2. LASSO introduces an L1 regularization penalty, which effectively shrinks the coefficients of less important predictors toward zero as the penalty parameter (λ) increases. This method enables automatic selection of the most relevant variables for predicting major amputation. The optimal value of λ was determined by cross-validation to achieve a balance between model simplicity and predictive accuracy.

By applying LASSO regularization for variable selection, we identified the most critical predictors associated with major amputation. These selected variables were subsequently utilized for model training and evaluation.

SMOTE for the imbalanced dataset

The original dataset exhibited a substantial class imbalance, with 54 patients (9.1%) having undergone major amputation and 544 patients (90.9%) not. This type of imbalance is a common challenge in clinical datasets and poses difficulties for constructing predictive models. Class imbalance is a common issue in clinical datasets, and the target variable in this study—major amputation—also exhibited significant imbalance. To address this, the Synthetic Minority Over-sampling Technique (SMOTE) was applied to the training data. SMOTE generates synthetic samples between minority class instances, thereby increasing the representation of the minority class and enabling the model to better learn and identify the characteristics of patients who underwent major amputation11.

In addition, all continuous variables were standardized to address differences in scale among features. Standardization was performed using the StandardScaler, which transforms each feature to have a mean of zero and a standard deviation of one. This process improves both the convergence speed and the predictive stability of machine learning models, and is particularly important for models that rely on distance metrics, such as support vector machines (SVM) and K-nearest neighbors (KNN)12.

Model construction

To comprehensively evaluate the performance of various algorithms for the prediction of major amputation, we employed six classical machine learning models: logistic regression, random forest, support vector machine (SVM), K-nearest neighbors (KNN), gradient boosting machine (GBM), and extreme gradient boosting (XGBoost). These models represent a diverse range of methodological approaches, from linear classifiers to ensemble-based nonlinear learners, and are capable of effectively handling different data distributions and feature complexities.

The entire dataset was randomly divided into a training set and validation set in an approximate ratio of 8:2 (specifically, 77.5% for training and 22.5% for validation). The training set was used to construct the predictive models, while the validation set was employed to evaluate the performance. To enhance model stability and generalizability, optimal hyperparameters for each algorithm were determined using grid search combined with tenfold cross-validation during the training phase (Table 1).

Model evaluation

To comprehensively assess the performance of the constructed models, several evaluation metrics were calculated, including accuracy, precision, recall rate, F1-score, and the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC). Higher values of these metrics—approaching 1.0—indicate better model performance13. The receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve was plotted to visually represent the model’s discriminative ability.

In addition, confusion matrices (CMs) were generated to provide a summary of the model’s predictive outcomes compared to actual values, offering further insight into classification accuracy.

Furthermore, decision curve analysis (DCA) was employed to evaluate the net clinical benefit of the models across a range of threshold probabilities. This method helps determine under which circumstances the model’s predictions can provide meaningful clinical value to guide decision-making14.

Major amputation risk prediction algorithm

A systematic machine learning algorithm was employed for major amputation risk prediction in diabetic foot ulcer patients. The development process consisted of several key steps. First, data preprocessing was performed by removing records with missing or incomplete information, standardizing all continuous variables, encoding categorical variables as required, and addressing class imbalance in the training set using the Synthetic Minority Oversampling Technique (SMOTE). Feature selection was then conducted using LASSO regression, and features with nonzero coefficients were retained for subsequent modeling. For model development, six algorithms—including logistic regression, random forest, support vector machine, K-nearest neighbors, gradient boosting machine, and XGBoost—were trained and validated. Each model was optimized through grid search and cross-validation, and performance was evaluated using metrics such as accuracy, area under the ROC curve (AUC), F1-score, precision, recall, calibration curves, confusion matrices, and decision curve analysis. The models were compared based on these metrics, and the best-performing model was selected for further clinical interpretation, including feature importance analysis and visualization of decision curves and confusion matrices. This algorithmic approach ensured a robust, reproducible, and clinically meaningful modeling framework (Table 2).

Results

Patient characteristics

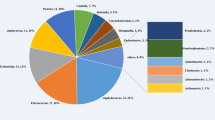

The original dataset consisted of 598 patient samples, each with 31 features, including the target variable “major amputation” (yes or no). All data were preprocessed during extraction, and no missing values were present. The features comprised both categorical variables (e.g., sex, Wagner grade) and continuous variables (e.g., white blood cell count, C-reactive protein), providing a comprehensive representation of the patients’physiological status and pathological characteristics (Table 3).

LASSO variable selection

LASSO regression was applied to visualize the coefficient paths and mean squared error (MSE) across a range of penalty values (λ). As shown in the coefficient path plot, with increasing values of λ, many regression coefficients gradually shrank toward zero. This demonstrates the effect of LASSO regularization, which systematically eliminates less correlated variables by penalizing their coefficients. Only the most influential predictors maintained non-zero coefficients under stronger regularization15.

Meanwhile, the MSE curve expressed a characteristic U-shape: it initially decreased as λ increased, indicating reduced overfitting, but it rose again at larger λ values due to underfitting caused by excessive regularization. The optimal penalty parameter was determined to be λ = 0.059, which achieved the best balance between bias and variance. At this optimal point, the model retained only the most predictive features (Figs. 2, 3).

A total of 17 variables were selected, including age, diabetes duration, wound size, history of peripheral neuropathy, and history of atrial fibrillation. Laboratory indicators comprised white blood cell count (WBC), C-reactive protein (CRP), procalcitonin (PCT), glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c), myoglobin (Mb), troponin (Tn), blood urea nitrogen (BUN), serum albumin, triglycerides (TG), and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C). In addition, the presence of multidrug-resistant infection and whether the patient underwent vascular intervention were also included as important predictors. These variables were subsequently used in model training and evaluation.

SMOTE algorithm

To address the class imbalance in the binary outcome variable, the Synthetic Minority Over-sampling Technique (SMOTE) was applied. Oversampling was performed on both the training and validation datasets. The distribution of samples before and after SMOTE processing is summarized in Table 4.

Model establishment and evaluation

Major amputation status was defined as the outcome label, while 17 statistically significant predictors identified by LASSO regression were used as input features. Risk prediction models for major amputation in patients with diabetic foot ulcers (DFU) were developed using six machine learning algorithms: logistic regression, random forest, support vector machine (SVM), K-nearest neighbors (KNN), gradient boosting machine (GBM), and extreme gradient boosting (XGBoost).

To provide a clear comparison of the performance of the six machine learning algorithms combined with the SMOTE technique, evaluation metrics are summarized in Table 5. Among all of the models/Compared with other models, GBM demonstrated the most favorable overall performance, achieving the highest scores across all key evaluation metrics, including accuracy (0.9408), precision (0.9855), recall (0.8553), F1-score (0.9158), and AUC (0.9499). These results indicate that GBM provided both strong discriminative power and a well-balanced trade-off between sensitivity and specificity.

Figure 4 presents the confusion matrices for each of the machine learning models. Each confusion matrix is composed of four quadrants, reflecting the number of true positives, true negatives, false positives, and false negatives. In this study, the class label 0 denotes patients who did not undergo major amputation during the treatment period, whereas 1 indicates patients who did receive major amputation. The distribution of predicted versus actual classifications provides insight into each model’s ability to correctly identify high-risk patients and avoid misclassification16. The GBM model exhibited the most balanced and favorable classification results, with 518 true negatives, 274 true positives, only 8 false positives, and 44 false negatives. This indicates excellent discrimination and high sensitivity for identifying patients at risk of major amputation.

To further assess clinical utility, decision curve analysis (DCA) curves were generated to evaluate the net benefit of each model across a range of threshold probabilities. As shown in Fig. 5, the GBM model consistently provided the highest net benefit, outperforming both the "treat-all" and "treat-none" strategies. XGBoost followed closely, maintaining a similarly high net benefit across clinically relevant thresholds (0.2–0.6). In contrast, SVM and KNN showed limited clinical benefit, with flatter DCA curves and inferior performance across most thresholds. LR and RF offered moderate utility but remained inferior to GBM and XGBoost.

The importance of characteristic variables

Based on the comprehensive evaluation of all algorithms, these findings demonstrate that GBM algorithm not only offers superior predictive accuracy but also provides the highest potential clinical benefit, making it the optimal model for predicting major amputation risk in patients with diabetic foot ulcers. Its robustness and interpretability support its use in clinical decision-making and early intervention strategies.

Accordingly, we further investigated the contribution of individual features within the GBM model. The relative importance of each predictor was quantified to identify the most influential variables in the risk prediction of major amputation. The feature importance ranking results are illustrated in Fig. 6.

The relative importance of variables in the gradient boosting machine (GBM) model was further analyzed to identify key predictors contributing to the risk of major amputation in diabetic foot ulcer (DFU) patients. As shown in Fig. 6, the presence of multidrug-resistant infection emerged as the most influential feature, with an importance score of 0.8289—significantly exceeding that of all other variables. This finding suggests that multidrug-resistant infection plays a pivotal role in clinical deterioration leading to major amputation, likely due to delayed wound healing, systemic infection, and limited antibiotic efficacy17. Other important predictors included C-reactive protein (CRP), an inflammatory marker indicative of systemic infection or severe local tissue damage, and history of diabetes mellitus, reflecting the underlying metabolic disorder associated with poor wound healing and peripheral vascular impairment18. Troponin (Tn) and age also contributed to the results of the model, suggesting that cardiac injury markers and advanced age may be associated with poorer prognosis and higher risk of limb loss.

Overall, the feature importance analysis highlights the clinical relevance of infection control, inflammation, and systemic comorbidities in the risk stratification of DFU patients, and supports their inclusion in predictive modeling for early intervention and limb preservation strategies.

Computational complexity analysis

This study utilized classical machine learning algorithms—including logistic regression, random forest, support vector machine, K-nearest neighbors, gradient boosting machine, and XGBoost—applied to structured clinical and laboratory data for major amputation risk prediction in patients with diabetic foot ulcers. In contrast to deep learning techniques commonly used for image analysis, such as convolutional neural networks, the computational requirements of the models in this study are minimal.

All models were trained and validated on a standard workstation (Intel Core i7 CPU, 16 GB RAM) without GPU acceleration. The number of parameters for each model is limited by the number of input features (17 after Lasso selection) and, in the case of ensemble models, by the number and depth of trees. For example, both GBM and XGBoost used a default of 100 trees, resulting in a total parameter count in the order of 10,000. Logistic regression and support vector machine models require far fewer parameters, generally fewer than 100 (Table 6).

The average prediction time for a single sample was less than 2 ms for all algorithms. Furthermore, GPU resources were not required or utilized, as all calculations were handled efficiently by the CPU. This is a marked contrast to deep learning methods used for wound image recognition, segmentation, or automatic classification, which involve millions of parameters, complex architectures, and typically demand dedicated GPU hardware for both training and inference.

Discussion

Based on a comprehensive comparison of six machine learning algorithms, the gradient boosting machine (GBM) model demonstrated the most favorable performance in predicting the risk of major amputation in diabetic foot ulcer patients. It achieved the highest recall (0.8553) and F1-score (0.9158), with excellent overall accuracy (0.9408) and discrimination (AUC = 0.9499). These metrics reflect GBM’s robust ability to correctly identify high-risk patients while maintaining precision and minimizing false positives. Although XGBoost exhibited the highest AUC (0.9674) and precision, its relatively lower recall rate (0.8019) suggests a potential trade-off in sensitivity, making GBM more suitable for early clinical risk screening where the avoidance of missed cases is critical. Random forest and logistic regression performed moderately well, while support vector machine (SVM) and K-nearest neighbors (KNN) were inferior in terms of recall rate and F1-score, limiting their clinical applicability. These results support the GBM model as the most clinically effective and reliable tool among those tested, offering superior balance between predictive accuracy and clinical decision-making utility. Integration of such models into diabetic foot management protocols may enhance early intervention strategies and improve limb salvage outcomes19.

This outperformed traditional approaches like logistic regression in our cohort, consistent with other reports that boosting algorithms offer superior discrimination in DFU outcomes. Notably, a recent multi-center study by Tao et al.20 developed a similar risk model using the XGBoost algorithm and 17 clinical features, achieving an internal validation AUC of 0.93 and accuracy of 0.94. Their model’s strong performance, even after external validation (AUC 0.83 on an independent cohort), underscores the high potential of gradient-boosting methods for DFU amputation prediction. Another group21 adopted an explainable LightGBM model to predict in-hospital DFU outcomes, reporting respectable multi-class AUCs of 0.85–0.90 for non-amputation, minor, and major amputation endpoints.These studies and our own results indicate that gradient-boosted ensemble models (including GBM, XGBoost, and LightGBM) consistently surpass more conventional models in accuracy for amputation risk, likely due to their ability to capture nonlinear interactions and complex feature relationships. In some DFU risk models, SVM has matched or outperformed other classifiers. For instance, a study of elderly diabetic patients tested multiple algorithms for DFU recurrence prediction—SVM, XGBoost, k-NN, random forest, and decision tree—and SVM achieved the highest accuracy (≈93%), significantly above the others (~ 79 to 82%)22. This suggests that classical SVM, with appropriate features (e.g. age, wound size, etc.), can be highly effective in structured clinical datasets. Another recent review noted that in DFU-related tasks, SVM often performed strongly, sometimes surpassing deep neural networks in classification accuracy23. Our study confirmed GBM’s top performance in a balanced dataset and by using decision-curve analysis to demonstrate its clinical value (a perspective often lacking in prior reports).These findings validate that “classical” ML models (SVM, GBM, XGBoost) remain powerful for DFU risk prediction. They leverage tabular clinical predictors (demographics, lab values, wound characteristics, etc.) and have delivered robust predictive accuracy in both retrospective modeling and prospective risk stratification. Notably, XGBoost and similar gradient-boosted tree ensembles excel at capturing non-linear interactions in structured data, while SVM can perform well with appropriate kernel choices and feature preprocessing. Indeed, some studies have observed diminishing returns from ensemble stacking on clinical tabular data. A recent analysis of hospital readmission prediction noted that a stacking ensemble (with XGBoost as meta-learner) achieved performance roughly on par with the single best model (XGBoost alone), indicating no significant advantage to the more complex ensemble. This aligns with the understanding that when base predictors are highly accurate and correlated, a voting or stacking ensemble will “not necessarily” outperform the strongest individual classifier24.

The GBM model’s feature selection and importance rankings highlighted several clinically pertinent predictors of major amputation in DFU patients. Foremost among these was the presence of a multidrug-resistant organism (MDRO) infection, which was dramatically more frequent in patients who underwent major amputation in our cohort. This finding is clinically intuitive—infections with MDROs are more difficult to eradicate, often signifying severe, prolonged infection that can precipitate limb-threatening conditions. Indeed, DFU patients with MDRO infections have been shown to experience higher rates of adverse outcomes, including a nearly 1 in 5 chance of requiring major amputation25. Elevated inflammatory markers, especially C-reactive protein (CRP), also emerged as strong risk factors. CRP is a well-known inflammation response mediator, and our results align with extensive evidence linking heightened systemic inflammation to worse DFU prognosis26.Prior studies have identified high CRP level as an independent predictor of amputation in diabetic foot cases. This makes clinical sense: an elevated CRP reflects severe or spreading infection and tissue injury, correlating with a greater likelihood that conservative measures will fail and amputation become necessary27.

Other prominent predictors included history of diabetes mellitus, troponin (Tn), and age. A longer diabetic history is associated with cumulative microvascular and macrovascular damage, impaired immunity, and higher rates of neuropathy and ischemia, all of which predispose to non-healing ulcers28,29. Elevated troponin levels, typically associated with cardiac injury, may reflect systemic atherosclerosis and generalized vascular insufficiency, indicating a higher likelihood of poor perfusion and impaired wound healing30. Older age further compounds these risks, as elderly patients often have frailty, comorbidities, and reduced regenerative capacity. Wound range was also a significant factor in the model. Larger ulcers are more likely to involve deeper structures, carry higher bacterial loads, and are more difficult to revascularize, thereby increasing the chance of amputation31. This aligns with clinical observations that wound extent is a critical determinant in limb salvage prognosis. Among laboratory indicators, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), albumin, blood urea nitrogen (BUN), triglycerides (TG), and white blood cell count (WBC) ranked highly. Dyslipidemia, particularly elevated LDL-C and TG, may reflect poor metabolic control and contribute to vascular damage32. Hypoalbuminemia is a well-established marker of malnutrition and catabolic stress, both of which impair wound healing and immunity33. Elevated BUN reflects renal dysfunction or dehydration, which have been linked to poor DFU outcomes. Lastly, WBC count is a traditional marker of infection severity, and its elevation underscores the role of systemic infection in the pathophysiology of limb loss34. Taken together, these features paint a coherent clinical picture: DFU patients at highest risk of major amputation tend to present with severe infection (MDRO, WBC, CRP), poor metabolic and nutritional status (TG, LDL-C, albumin, BUN), larger and more chronic wounds, and systemic deterioration (advanced age, cardiac markers). Recognizing and responding to these factors in a timely manner may allow for earlier interventions—such as targeted antibiotics, nutritional support, or expedited vascular consultation—to improve limb salvage outcomes.

In addition to statistical superiority, the GBM model demonstrated clear advantages in clinical decision-making utility. It achieved the highest sensitivity and specificity among the tested models, meaning it successfully identified the majority of patients who ultimately required major amputation while minimizing false alarms. The confusion matrix for GBM showed a markedly higher true positive rate and lower false negative count compared to other algorithms, reflecting its high recall (0.8553) without sacrificing precision. In practical terms, this balance is crucial: a model that misses few actual at-risk patients (high sensitivity) can serve as an effective early warning system on which clinicians can rely to trigger interventions, whereas a high precision ensures we are not over-treating large numbers of low-risk patients35. For example, our GBM’s precision (0.9885) translates to very few false positives–most patients it flagged as high-risk truly needed an amputation or were on that trajectory. Such performance instills confidence that implementing the model in clinic could meaningfully stratify DFU patients: those predicted high-risk might be funneled to more aggressive therapies (urgent revascularization, advanced wound care, or closer monitoring), whereas low-risk predictions could support conservative management, thereby allocating resources more efficiently.

The original dataset was highly imbalanced, with only 54 major amputation cases versus 544 non-amputation cases—a positive-to-negative ratio of approximately 1:10. This level of imbalance can severely bias standard classification algorithms toward the majority class. To address this, we employed the Synthetic Minority Oversampling Technique (SMOTE) to increase the number of minority class samples before model training36. After applying SMOTE, the training set included 253 major amputation cases and 421 non-amputation cases. The validation set included 73 major amputation cases and 123 non-amputation cases. This resulted in a positive class proportion of ~ 38%, substantially alleviating the class imbalance. We acknowledge that the data remained somewhat imbalanced after SMOTE. However, we intentionally avoided overcompensating to achieve a 1:1 balance. Oversampling the minority class to match the majority (e.g., generating over 350 synthetic cases from only 42 real ones) could introduce synthetic noise and reduce the model’s generalizability, particularly given the small absolute number of positive cases. Literature supports the notion that moderate oversampling can yield better model performance and reduce overfitting compared to aggressive balancing strategies. Our approach aligns with this evidence37,38.

Beyond traditional metrics, we used decision curve analysis (DCA) to appraise the net benefit of the GBM model across various threshold probabilities. The DCA curves illustrated that our GBM model yielded a greater net benefit than either the "treat-all" or "treat-none" extremes over a broad range of clinically relevant risk thresholds39. In other words, using the GBM model to guide intervention decisions (e.g. Choosing which patients should undergo early surgical consultation or intensive limb salvage measures) would lead to better outcomes on average than intervening on every DFU patient or only reacting to unavoidable amputation. This suggests that the model can improve clinical decision-making by identifying those who are most likely to benefit from escalated care. Notably, none of the other machine learning models provided comparable net benefit on DCA—the GBM consistently had the highest net benefit curve, underscoring its potential clinical advantage. From a clinician’s perspective, this means that if one were to act on the GBM model’s predictions, one could achieve more limb-preserving interventions (true positives treated) while avoiding unnecessary procedures in patients unlikely to require amputation (reducing false positives), thus improving the overall efficiency of care40. Ultimately, the combination of superior accuracy and proven net benefit indicates that our GBM model is not only statistically robust but also meaningfully useful in the clinical context. This is a critical distinction, as other predictive models perform well in theory yet offer trivial gains in practice–our analysis suggests the GBM model crosses that threshold and could positively impact patient management.

In this study, Diabetic foot ulcer (DFU) risk prediction relies on structured clinical variables (e.g., lab results, comorbidities) rather than unstructured data like images. Classical ML models excel here. We selected six classical machine learning algorithms—including logistic regression, random forest, support vector machine, K-nearest neighbors, gradient boosting machine, and XGBoost—were constructed using structured clinical and laboratory data, rather than medical images. These algorithms are considered classical machine learning models, characterized by relatively simple mathematical formulations and modest computational demands. LR provides interpretability and captures linear relationships clearly, facilitating clinical interpretation. RF effectively manages complex nonlinear relationships and reduces overfitting through ensemble averaging, enhancing model robustness and interpretability. SVM, with its kernel functions, excels in identifying nonlinear relationships even in high-dimensional spaces, making it highly effective for classification tasks with limited data. KNN captures subtle local patterns through instance-based similarity measures, beneficial in clinical contexts where local data structures are predictive. GBM’s iterative approach progressively corrects prediction errors, efficiently modeling complex interactions among clinical predictors. Finally, XGBoost further enhances predictive performance and computational efficiency through advanced regularization and optimization techniques, effectively capturing subtle yet clinically relevant patterns within structured medical data. Collectively, these models ensure comprehensive and robust predictions, addressing various complexities inherent in clinical data. In contrast to deep learning methods such as eXplainable Artificial Intelligence (XAI) algorithms—SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations), Local Interpretable Model-agnostic Explanations (LIME), and Siamese Neural Network (SNN), which are widely used for diabetic foot ulcer image recognition, segmentation, or other image-based diagnostic tasks, classical machine learning approaches do not require millions of trainable parameters or computationally intensive operations (such as multiple convolutional layers or complex backpropagation procedures)41,42. Recent advances in deep learning (DL) have shown impressive results in the field of diabetic foot ulcer (DFU) detection, particularly for image-based tasks. For instance, Biswas et al. proposed the DFU_XAI framework, which integrates multiple convolutional neural network (CNN) architectures—such as ResNet50, DenseNet121, and InceptionV3—with explainability techniques like SHAP, LIME, and Grad-CAM to detect and localize ulcers from foot images with near-perfect performance (e.g., ResNet50 achieved 98.75% accuracy and 98.5% AUC)43. However, despite their high predictive power, DL models remain computationally intensive, often requiring high-performance graphical processing units (GPUs), large-scale labeled datasets, and complex post hoc interpretability techniques. These limitations hinder their real-time applicability and accessibility in resource-limited or routine clinical settings.In contrast, the current study adopts a suite of well-established, classical machine learning algorithms—including logistic regression (LR), random forest (RF), support vector machine (SVM), K-nearest neighbors (KNN), gradient boosting machine (GBM), and extreme gradient boosting (XGBoost)—which are particularly well-suited for structured clinical and laboratory data. These models offer significant advantages in terms of computational efficiency, interpretability, and deployment feasibility. For example, LR provides odds ratios that can be directly interpreted by clinicians, while tree-based models (e.g., RF and XGBoost) yield feature importance rankings that facilitate clinical insight. Moreover, these models can be trained and executed rapidly on standard CPUs without the need for specialized hardware, enabling real-time risk prediction and integration into hospital information systems. As a result, all algorithms in this study can be efficiently trained and executed on standard central processing units (CPUs), without the need for dedicated graphical processing unit (GPU) acceleration. In practice, this confers several advantages: model training and inference can be completed within seconds to minutes on conventional desktop computers or hospital information systems; the number of model parameters is generally proportional to the number of input features and model complexity (such as tree depth in ensembles), typically reaching only hundreds or thousands—orders of magnitude less than deep learning models; and the prediction time per new sample is nearly instantaneous (less than a few milliseconds), enabling these models to be deployed in real-time clinical decision support settings. By comparison, deep learning approaches, while powerful for complex data types such as wound images, histopathology, or multimodal inputs, are computationally intensive and require substantial hardware resources, particularly GPUs, for both training and inference due to their intricate architectures and large parameter spaces.

Despite encouraging results, our study has several limitations. First, this was a retrospective, single-center study at a tertiary care hospital. The retrospective design carries inherent biases (e.g. reliance on the accuracy of recorded data) and precludes us from proving any causal relationships. Being single-center, our patient population and treatment patterns may not fully represent other settings; for instance, as a referral center we saw many advanced DFU cases, which could limit generalizability to patients with milder disease. Second, the sample of patients who underwent major amputation was relatively small (n = 54, 9.1%), reflecting the low event rate of this outcome. Although we addressed class imbalance with SMOTE and cross-validation, the limited number of events raises the risk of overfitting and may overstate performance metrics. We acknowledge that the overall sample size in our study is relatively limited, a challenge often encountered in clinical machine learning studies due to strict inclusion criteria and single-center data collection. However, small datasets do not necessarily preclude meaningful modeling if the data quality is high and the methodology is rigorous. Previous studies, such as Thotad et al.44, have effectively utilized limited datasets—e.g., 844 wound images—to achieve high prediction performance in diabetic foot ulcer (DFU) detection using machine learning techniques, yielding F1 scores above 98%. In our study, the dataset consists of well-curated, clinically verified cases, and we applied multiple strategies including cross-validation and robust feature selection to enhance model generalizability. These approaches help to mitigate overfitting and ensure reliable predictions even in small datasets. Third, the set of features we analyzed, while comprehensive in terms of clinical and laboratory variables, was not exhaustive. We did not include certain potentially important predictors such as detailed vascular imaging findings, neuropathy severity beyond clinical history, or wound characteristics (e.g. ulcer depth, perfusion status) beyond the Wagner grade. Lastly, we lacked an independent external validation cohort. All model development and testing were done on data from the same institution (split into training and internal validation sets). This may inflate our reported performance, as models often face a drop in accuracy when applied to external data due to population differences.

Given the aforementioned limitations, several avenues for future work are recommended. External validation of our GBM model is a top priority—testing it on datasets from other hospitals or regions will verify its generalizability and calibration in diverse patient populations. Ideally, this would be followed by prospective studies or impact assessments: for example, implementing the model in a clinical workflow to determine if its use can actually reduce amputation rates or improve intervention timely. Collaboration with multiple centers to assemble a larger, heterogeneous cohort would strengthen the model and potentially allow subgroup analyses (such as separate prediction models for minor vs. major amputations). Additionally, expanding the feature set could further enhance predictive power. Incorporating variables like infection severity scores, advanced imaging (for perfusion or osteomyelitis), or novel biomarkers (e.g. inflammatory or proteomic markers) has been suggested to improve risk stratification. Another important future step is integrating the model into clinical information systems. By deploying our algorithm as a decision-support tool within electronic health records, clinicians could receive real-time risk scores for incoming DFU patients. Such integration would enable dynamic risk updates and prompt alerts—for instance, flagging a high-risk patient on admission so that a multidisciplinary foot care team can be mobilized promptly. Ultimately, we envision that with further validation and refinement, this GBM-based model (and others like it) can be incorporated into routine care to guide personalized management of DFU patients. By identifying those at greatest risk for limb loss, healthcare providers can target aggressive preventive strategies to the right patients at the right time, which holds promise for improving limb salvage rates and reducing the overall burden of diabetic foot amputations. The continued evolution of such predictive models–combined with user-friendly clinical deployment and rigorous prospective evaluation–will be crucial steps toward translating machine learning advances into tangible improvements in patient outcomes45.

Conclusion

Gradient Boosting Machine (GBM) is a powerful and effective machine learning technique that has been utilized with great success in the medical field, particularly for predicting the likelihood of significant complications in patients suffering from diabetic foot conditions. This method is instrumental in forecasting the risk of major amputations, which is a critical concern for individuals with diabetes who are at risk of developing severe foot ulcers and infections. By leveraging the GBM model, healthcare professionals can gain valuable insights and make informed decisions to potentially reduce the incidence of such serious outcomes, thereby improving patient care and outcomes.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Armstrong, D. G., Boulton, A. J. M. & Bus, S. A. Diabetic foot ulcers and their recurrence. N. Engl. J. Med. 376(24), 2367–2375 (2017).

Liao, X. et al. Surgical amputation for patients with diabetic foot ulcers: A Chinese expert panel consensus treatment guide. Front Surg. 9, 1003339 (2022).

Meloni, M. et al. Foot Revascularization avoids major amputation in persons with diabetes and ischaemic foot ulcers. J. Clin. Med. 10(17), 3977 (2021).

Apelqvist, J. et al. International consensus and practical guidelines on the management and the prevention of the diabetic foot. J. Diabetes Metab Res. Rev. 16(Suppl 1), S84–S92 (2000).

Nazri, M. Y. et al. Quality of life of diabetes amputees following major and minor lower limb amputations. Med. J. Malaysia 74(1), 25–29 (2019).

Haug, C. J. & Drazen, J. M. Artificial intelligence and machine learning in clinical medicine. N. Engl. J. Med. 388(13), 1201–1208 (2023).

Hunter, B., Hindocha, S. & Lee, R. W. The role of artificial intelligence in early cancer diagnosis. Cancers (Basel) 14(6), 1524 (2022).

Swanson, K. et al. From patterns to patients: advances in clinical machine learning for cancer diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment. Cell 186(8), 1772–1791 (2023).

Obermeyer, Z. & Emanuel, E. J. Predicting the future-big data, machine learning, and clinical medicine. N. Engl. J. Med. 375(13), 1216–1219 (2016).

Hickman, S. E. et al. Machine learning for workflow applications in screening mammography: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Radiology 302(1), 88–104 (2022).

Ren, Y. et al. Issue of data imbalance on low birthweight baby outcomes prediction and associated risk factors identification: establishment of benchmarking key machine learning models with data rebalancing strategies. J. Med Internet Res. 25, e44081 (2023).

Yue, S. et al. Machine learning for the prediction of acute kidney injury in patients with sepsis. J. Transl Med. 20(1), 215 (2022).

Minami, T. et al. Machine learning for individualized prediction of hepatocellular carcinoma development after the eradication of hepatitis C virus with antivirals. J. Hepatol S0168–8278(23), 00424–00425 (2023).

Hozo, I. & Djulbegovic, B. Generalised decision curve analysis for explicit comparison of treatment effects. J. Eval. Clin. Pract. 29(8), 1271–1278 (2023).

Oh, H. S. et al. Organ aging signatures in the plasma proteome track health and disease. Nature 624(7990), 164–172 (2023).

Valero-Carreras, D., Alcaraz, J. & Landete, M. Comparing two SVM models through different metrics based on the confusion matrix. Comput. Oper. Res. 152(1), 106131 (2023).

Zubair, M. Prevalence and interrelationships of foot ulcer, risk-factors and antibiotic resistance in foot ulcers in diabetic populations: a systematic review and meta-analysis. World J. Diabetes 11(3), 78–89 (2020).

Cervantes-García, E. & Salazar-Schettino, P. Clinical and surgical characteristics of infected diabetic foot ulcers in a tertiary hospital of Mexico. Diabet Foot Ankle 8(1), 1367210 (2017).

Stefanopoulos, S. et al. Machine learning prediction of diabetic foot ulcers in the inpatient population. Vascular 30(6), 1115–1123 (2022).

Tao, H. et al. An interpreting machine learning models to predict amputation risk in patients with diabetic foot ulcers: A multi-center study. Front Endocrinol. (Lausanne) 16, 1526098 (2025).

Xie, P. et al. An explainable machine learning model for predicting in-hospital amputation rate of patients with diabetic foot ulcer. Int. Wound J. 19(4), 910–918 (2022).

Hong, S. et al. Personalized prediction of diabetic foot ulcer recurrence in elderly individuals using machine learning paradigms. Technol. Health Care 32(S1), 265–276 (2024).

Alkhalefah, S., AlTuraiki, I. & Altwaijry, N. Advancing diabetic foot ulcer care: AI and generative AI approaches for classification, prediction, segmentation, and detection. Healthcare 13(6), 648 (2025).

Ning, Y. et al. A novel interpretable machine learning system to generate clinical risk scores: An application for predicting early mortality or unplanned readmission in a retrospective cohort study. PLOS Digit Health 1(6), e0000062 (2022).

Gupta, S. et al. Outcome in patients of diabetic foot infection with multidrug resistant organisms. J. Foot Ankle Surg. 5(2), 51–55 (2018).

Wang, S., Wang, J., Zhu, M. X. & Tan, Q. Machine learning for the prediction of minor amputation in University of Texas grade 3 diabetic foot ulcers. PLoS ONE 17(12), e0278445 (2022).

Stefanopoulos, S. et al. A machine learning model for prediction of amputation in diabetics. J. Diabetes Sci Technol 18(4), 874–881 (2024).

Xu, J. et al. The risk factors in diabetic foot ulcers and predictive value of prognosis of wound tissue vascular endothelium growth factor. Sci. Rep. 14(1), 14120 (2024).

Coşkun, B. et al. Relationship between prognostic nutritional index and amputation in patients with diabetic foot ulcer. Diagnostics 14(7), 738 (2024).

Yan, H. et al. Inflammation mediates the relationship between cardiometabolic index and vulnerable plaque in patients with acute coronary syndrome. Lipids Health Dis. 24(1), 194 (2025).

Meloni, M. et al. Predictive factors of major amputation in patients with diabetic foot ulcers treated by peripheral blood mononuclear cells. Acta Diabetol. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00592-025-02522-2 (2025).

Ahmadi, S. A. Y. et al. Designing a logistic regression model for a dataset to predict diabetic foot ulcer in diabetic patients: high-density lipoprotein(HDL) cholesterol was the negative predictor. J. Diabetes Res. 2021, 5521493 (2021).

Husers, J. et al. Predicting the amputation risk for patients with diabetic foot ulceration-a Bayesian decision support tool. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 20(1), 200 (2020).

Ammar, A. S. et al. Predictors of lower limb amputations in patients with diabetic foot ulcers presenting to a tertiary care hospital of Pakistan. J. Pak Med. Assoc. 71(9), 2163–2166 (2021).

Gaber, F. et al. Evaluating large language model workflows in clinical decision support for triage and referral and diagnosis. NPJ Digit Med. 8(1), 263 (2025).

Thotad, P. N., Bharamagoudar, G. R. & Anami, B. S. Diabetic foot ulcer detection using deep learning approaches. Sens. Int. 4, 100210 (2023).

López-Martínez, F., Núñez-Valdez, E. R., Crespo, R. G. & García-Díaz, V. An artificial neural network approach for predicting hypertension using NHANES data. Sci. Rep. 10(1), 10620 (2020).

Wongvorachan, T., He, S. & Bulut, O. A comparison of undersampling, oversampling, and SMOTE methods for dealing with imbalanced classification in educational data mining. Information 14(1), 54 (2023).

Wu, B., Niu, Z. & Hu, F. Study on risk factors of peripheral neuropathy in type 2 diabetes mellitus and establishment of prediction model. J. Diabetes Metab. 45(4), 526–538 (2021).

Stefanopoulos, S. et al. Machine learning prediction of diabetic foot ulcers in the inpatient population. J. Vasc. 30(6), 1115–1123 (2022).

Rathore, P. S. et al. A feature explainability-based deep learning technique for diabetic foot ulcer identification. Sci. Rep. 15(1), 67589 (2025).

Biswas, S., Mostafiz, R., Uddin, M. S. & Paul, B. K. XAI-FusionNet: Diabetic foot ulcer detection based on multi-scale feature fusion with explainable artificial intelligence. Heliyon 10(10), e31228 (2024).

Biswas, S. et al. DFU_XAI: A deep learning-based approach to diabetic foot ulcer detection using feature explainability. Biomed. Mater. Devices 2, 1225–1245 (2024).

Thotad, P. N., Bharamagoudar, G. R. & Anami, B. S. Diabetes disease detection and classification on Indian demographic and health survey data using machine learning methods. Diabetes Metabolic Syndrome 17(1), 102690 (2023).

Hou, F. et al. Development and validation of an interpretable machine learning model for predicting the risk of distant metastasis in papillary thyroid cancer: A multicenter study. J. EClinicalMedicine 77, 102913 (2024).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Z.L. contributed to data curation, formal analysis, machine learning model development, and original draft preparation. D.W. was responsible for clinical investigation, supervision, and critical revision of the manuscript. J.W. contributed to methodology design, model validation, statistical analysis, and project administration. L.G. led the study conceptualization, overall project supervision, and manuscript writing and editing. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, Z., Wei, D., Wang, J. et al. Predicting major amputation risk in diabetic foot ulcers using comparative machine learning models for enhanced clinical decision-making. Sci Rep 15, 28103 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-13534-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-13534-x