Abstract

With increased longevity after spinal cord injury (SCI), cardiovascular disease has emerged as a major cause of morbidity and mortality. We evaluate the association of body composition and injury level with cardiometabolic disease (CMD) risk factors. Sixty-two individuals (69% male, 31% female) with chronic SCI (mean duration 7.4, SD ± 5.8 years) were recruited. Mean age of participants was 34.4 ± 12.1 years with BMI of 23.8 ± 5, while 64% had BMI < 25 and 11% >30. Total and percent truncal fat correlated positively (p < 0.05) with serum triglycerides, non-high-density lipid cholesterol, c-reactive protein (CRP), oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT), and measures of insulin resistance. Those with obesity in SCI (defined as BMI ≥ 22) had increased total and trunk mass and fat percentage, unfavorable lipid profiles and evidence of insulin insensitivity. Total fat was associated with CMD risk factors, including insulin resistance (OGTT 60 min r = 0.47, p < 0.05; homeostasis model assessment [HOMA] r = 0.62, p < 0.05), serum triglycerides (r = 0.31, p < 0.05), and inflammation (CRP r = 0.43, p < 0.05). Obesity in SCI related to higher CMD risk, while time since injury and injury level (paraplegia versus tetraplegia) did not. Future studies may evaluate roles of nutrition, exercise, sleep-promotion, and pharmaceuticals to lower neurogenic obesity and chronic CMD risk.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Sequelae of spinal cord injury (SCI) include dramatic changes in body composition and metabolic dysfunction that lead to higher risk of cardiovascular disease and decreased life expectancy1,2,3,4. Within weeks of injury, decreases in muscle cross sectional area and free fat mass as well as increased fat infiltration contribute to neurogenic obesity5,6,7,8,9. A positive energy balance with reduced basal metabolic rate and resting energy expenditure ultimately result in higher visceral adipose tissue5,10. Additionally, the loss of muscle mass coupled with the accumulation of visceral fat are believed to drive a metabolically unhealthy obesity with insulin resistance and unfavorable lipid profiles5,11,12. This trend appears to correspond with level of injury such that individuals with tetraplegia have higher percentages of central and visceral adiposity as well as lipid dysfunction compared with those with paraplegia3,13,14,15. In those with SCI, body mass index (BMI) > 22.0 is considered to define obesity that accounts for the metabolic consequences of increased fat mass percentage and dramatic skeletal muscle atrophy16.

Truncal fat and central obesity have been linked to pro-inflammatory cytokines and increased risk of cardiometabolic disease (CMD) in the general population17. While central or visceral obesity may represent primary sources of inflammation, it is unclear what other factors may play a role in driving or sustaining the inflammatory state in SCI8,18. Further, CMD, a key outcome of body composition dysregulation, is a leading cause of death in SCI and is observed in 72% of those with chronic SCI compared to 34% of able-bodied adults2,3,4,5,12,19. Individuals with SCI experience CMD from insulin insensitivity, dyslipidemia, and vascular disease earlier and with greater incidence and severity1,12,13. Inflammatory changes underlie the difference between metabolically unhealthy versus metabolically healthy obese in the general population20. Specifically, adipokines signal regional pro-inflammatory changes, including macrophage inflammatory protein-1 alpha (MIP-1 α), monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1), interleukin 8 (IL-8), and tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) with infiltration into adipose tissue that dysregulate systemic metabolism and lead to insulin resistance and vascular dysfunction8,20,21. Similarly, levels of pro-inflammatory c-reactive protein (CRP) and IL-6 are associated with chronic SCI and contribute to the milieu of chronic inflammation, lipid metabolism dysregulation, and vascular injury22,23. Ectopic fat stores contribute to systemic inflammation and metabolic syndrome24. Further, gut microbiome changes accompany SCI and lead to bowel dysfunction and resulting gut dysbiosis characterized by decreases in butyrate-producing “healthy gut bacteria”25,26. However, few studies have investigated the relationship between body profile and immune markers or changes to the microbiome, as well as the role certain systemic inflammatory markers may have in duration of SCI.

In the present study, 62 persons with chronic spinal cord injury were recruited and analyzed to assess body composition, level of injury, metabolic profile, inflammation and risk of CMD. Specifically, relationships between body composition, serum inflammatory markers, bowel dysfunction and transit, stratified by BMI and relevant injury severity across individuals with paraplegia and tetraplegia are investigated. The aim of the description study was to assess correlations between inflammatory markers and body composition changes and determine the extent to which level of injury, time since injury, or body composition may influence these changes in inflammation. We hypothesize that greater BMI will relate to higher systemic inflammatory changes and that bowel dysfunction will relate to worse inflammatory changes and body pod metrics.

Methods

Study design

Cross-sectional cohort study design.

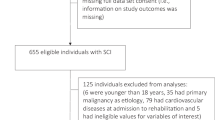

Patient selection

Adult patients > 18 years old with chronic traumatic spinal cord injury (injury duration > 2 years) American Spinal Injury Association (ASIA) grades A-C were included in the study. ASIA A is complete motor and sensory loss below the level of the lesion while ASIA B refers to motor loss but sensation present below the level of the lesion. ASIA C relates to sensation below the level of the lesion with motor strength less than 3/5 in half of key muscle groups below level of the lesion. Exclusion criteria included SCI from non-traumatic etiology (i.e. neoplasm, infection, etc.) or active infection that may confound inflammatory markers. The institutional review board (IRB) approved the present study (IRB# 16.0179). All participants were recruited by phone and medically approved for enrollment in a prospective outpatient, standardized program from 2009 to 2020, as previously described27. Patients with chronic spinal cord injury were recruited to participate in a spinal cord epidural stimulator trial with a rehabilitation regimen 2–3 weeks after implantation. Data was taken from this recruitment study in a retrospective fashion, and the need to obtain additional informed consent was waived by the University of Louisville IRB. All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations of the institution and journal.

Metabolic measures

Body composition was measured by dual energy X-ray absorptiometry (DEXA) scan. Metabolic profile, lipids, high-sensitivity CRP (hsCRP), a battery of inflammatory cytokines were assessed through analysis of serum samples. American Diabetes Association criteria for normal, impaired fasting glucose (IFG), impaired glucose tolerance (IGT), and diabetes mellitus (DM) were used28. Oral Glucose Tolerance Test (OGTT) was performed with 75 gram glucose load and blood samples drawn at 0, 30, 60, 90, and 120 min for measurement of glucose and insulin (Table 1). Insulin Resistance was estimated using the following: Homeostasis Model Assessment 2 (HOMA2); Homeostasis Model Assessment of Insulin Resistance (HOMA-IR); Matsuda Index. Matsuda Index is a measure of peripheral or whole-body insulin sensitivity that is calculated by non-fasting glucose tolerance test. Values greater than 4.0 indicate increased insulin insensitivity29. Insulin Secretion was estimated using Insulinogenic Index and Disposition Index. Diet and calorie breakdown including macronutrients were recorded for groups, as was the neurogenic bowel score.

Because of drastic changes to body composition that accompany SCI due to sarcopenia and neurogenic obesity, standard body mass index (BMI) cutoffs are not accurate in assessing obesity. Specifically, BMI (a standard surrogate measure of body fat percentage using height and weight) underestimates percentage fat mass in patients with SCI30. A more appropriate cutoff, given the associated loss of muscle mass, has been proposed to be 22 kg/m16,19. Thus, an additional subgroup analysis dividing patients with obesity (BMI ≥ 22) and those without obesity (BMI < 22) were analyzed across body composition, metabolic, blood, and serum variables. A second subgroup analysis determined those with paraplegia defined as those with injury below thoracic level 1 (T1) versus those with tetraplegia defined as those with injuries at and above T1.

A subset of 38 individuals underwent OGTT among whom 27 had insulin resistance assessed by HOMA-IR and the Matsuda Index.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables were summarized with median and interquartile range and compared with Wilcoxon Rank Sum test. Categorical variables were summarized with percentage and compared with Fisher’s Exact test. Pearson correlation was used to assess the correlation between different parameters. The significance level for outcomes comparisons was set to the Bonferroni adjusted value of 0.0004 (0.05/116 outcome comparisons). All tests were 2-sided. Statistical analyses were performed in SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina, United States).

Results

Participant demographics and clinical characteristics

A total of 62 individuals (69% male, n = 43; 31% female, n = 19) with chronic traumatic SCI, mean injury duration 7.4 ± 5.8 years, were included in the study, Table 2. The mean age of participants was 34.4 ± 12.1 years. Cervical level of injury was observed in 79% of cases and thoracic in 18%. Severity of injury included ASIA A grade in 61% (n = 49), ASIA B 34% (n = 21), and ASIA C in 2% (n = 1). Approximately 64% had BMI < 25 and 11% > 30.

Body composition

Mean BMI was 23.8 ± 5, Table 3. Several measures of body fat were significantly correlated with cardiometabolic risk factors. Total and percent truncal fat correlated positively with serum triglycerides, non-high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol, hsCRP, glucose at 30, 60, and 120 min during OGTT, and HOMA IR. Total and percent truncal fat correlated negatively with HDL cholesterol and Matsuda Index.

Metabolic profile

Mean hemoglobin A1C (HbA1c) was 5.0 ± 0.6 with 95% of individuals with HbA1c < 5.7, Table 4. Mean HDL was 42.4 ± 12.7 mg/dL and triglycerides were 113.1 ± 71.3 mg/dL. Low HDL (< 40 mg/dL) was noted in 47% and high TG in 22% of individuals, Supplementary Table 1. High fasting glucose was noted in 15% and high 2 h glucose in 32% of individuals, Table 5. HOMA IR was > 2.0 in 37% and Matsuda Index < 4.3 in 59% of individuals.

Inflammatory profile

Inflammatory marker CRP correlated positively with BMI (r = 0.57), total fat (r = 0.42) and truncal fat (r = 0.43), see Supplementary Table 1. Additionally, IL-8 correlated positively with HbA1c (r = 0.69), serum glucose (r = 0.62), BMI (r = 0.34), triglycerides (r = 0.43), total lean mass (r = 0.42) and truncal lean mass (r = 0.38). Interleukin 27 correlated with neurogenic bowel score (r = 0.42).

BMI and level of injury subgroup analyses

Patients were dichotomized into below BMI 22 (n = 13) and BMI ≥ 22 (n = 13). Of those with BMI below 22, 31% were female with median age of 30 years. Of those greater than or equal to 22, 8% were female with median age of 39 years. The population was also dichotomized into those with paraplegia (below T1 injury level) (n = 5) versus tetraplegics (at and above T1 injury level) (n = 22). For those with paraplegia, females made up 18% with median age 31, half were ASIA A and the other half ASIA B. Those with tetraplegia were 20% female and median age of 39, 40% ASIA A, 40% ASIA B, 20% ASIA C.

For those with BMI ≥ 22, body fat % was higher when compared to those with BMI < 22 (42.9 vs. 33.3%, p = 0.0048), as was total mass, total fat, trunk mass, trunk fat, and trunk lean mass. Body composition metrics were not statistically different between injury level groups, for those with paraplegia versus tetraplegia.

Baseline insulin and c-peptide were higher for those with BMI ≥ 22 compared to BMI < 22 (8.5 vs. 5.1 mlU/L, p = 0.0096) and 1.93 versus 1.1 mlU/L, p = 0.009), as was 30-minute insulin on OGTT (89.8 versus 41.5 mmol/L, p = 0.0333). All measures of OGTT were similar for patients above and below T1 injury levels. Matsuda Index was lower for those with BMI ≥ 22 (2.98 versus 6.92, p = 0.0138) and HOMA-IR was higher (2.02 versus 1.09, p = 0.0111) when compared to those with BMI < 22. HOMA2%B was higher for the BMI ≥ 22 group (95.7 versus 75.5, p = 0.0378), lower for HOMA2%S (86.7 versus 151.6, p = 0.0083), and greater for HOMA-IR (1.15 versus 0.66, p = 0.0089). Matsuda and HOMA values were similar between injury level groups.

Those with BMI ≥ 22 HDL had worse lipid profile values with lower HDL (34 versus 45 mg/dL, p = 0.0056), higher triglycerides (107 versus 65 mg/dL, p = 0.0011), higher low-density-lipoproteins (LDL) (112 versus 82 mg/dL, p = 0.0311), and overall non-HDL cholesterol (89 versus 13 mg/dL, p = 0.0255). No differences were observed in lipid profile lab values between injury level groups. Serum values assessing inflammatory profiles and neurogenic bowel score were similar between both BMI and injury level subgroups. All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article [and its supplementary information files].

Discussion

Before 1970, urogenital complications were a leading cause of mortality in SCI31. As urinary and pulmonary infections have been better controlled and greater longevity is seen in those with SCI, cardiovascular disease is now a leading cause of death5,31. Due to the ensuing energy imbalance with less physical exercise, adiposity, and higher risk of cardiometabolic complications, cardiovascular disease is a leading cause of mortality in SCI19. Those with SCI become physically deconditioned following injury, leading to physiologic alterations and reduction in whole-body metabolism19. Cellular, hormonal, tissue, and organ system changes following SCI predispose to greater metabolic risk profiles that lead to premature onset of metabolic syndrome and CMD8,9. Traumatic SCI has a higher 5-year accumulation of CMD risk factors compared with able-bodied adults (56% vs. 36%) and more than tripled risk for heart failure1. There is an elevation of 47% in mortality for those with SCI over 4.5 years in one study and the most common cause of death was circulatory diseases at over 40%4. The present study demonstrates increased risk of CMD in those with chronic SCI in metabolic, body composition domains, particularly for those with BMI > 22. Moreover, the impact of obesity and truncal fat—independent of time since injury and level of injury—appear to have a major role in CMD risk in those with SCI.

Metabolic syndrome has been observed in as many as 55% of those with chronic SCI32. Several sources assert that tetraplegia is associated with greater CMD risk and body composition deterioration than is paraplegia8,15,33. One study showed that patients with tetraplegia tend to have 5% higher fat mass than those with paraplegia33. Other studies have reported no changes in body composition between tetraplegia versus paraplegia or even worse body composition for those with paraplegia34,35. The current study shows that body composition, independent of injury level, is associated with elevated CMD risk. Moussavi and colleagues demonstrated that time since injury was more associated with severity of dyslipidemia36. However, the present study showed that time since injury was not correlated with body composition changes nor CMD profile risk.

Decrements in body composition

Truncal or central obesity has been particularly implicated as a driver for cardiometabolic disease risk in those with SCI19,37. Central or visceral fat is metabolically active with adipokines increasing systemic inflammation5,6,37,38. Additionally, regional fat distribution with higher waist circumference and deposition of visceral fat has been associated with higher risk of dyslipidemia, insulin resistance, and greater than 10% risk of heart attack in 10 years (Framingham risk score) than BMI or other fatty body composition8,37. Given energy expenditure differences after injury, those with SCI are at greatest risk of building central adiposity, especially in the first year following injury19,39.

In the general population, a ratio of 0.4 subcutaneous adipose tissue (SAT) to visceral adipose tissue (VAT) ratio is associated with higher risk of developing CMD; whereas, those with SCI are reported to have a SAT to VAT ratio of 0.75,38. The present study demonstrates that BMI ≥ 22 kg/m was related to higher risk of CMD with higher truncal fat, worsened lipid profile, greater insulin insensitivity when compared with those without obesity. When the sample was dichotomized by level of injury, no changes were observed in CMD risk. Clinical significance of BMI 22 appears to indicate an appropriate cutoff to demonstrate CMD risk16. Our findings are inconsistent with prior literature regarding increased risk of poor body composition and subsequent CMD risk in those with tetraplegia. Spungen et al. demonstrate that those with tetraplegia had greater total and regional obesity than those with paraplegia34. Additionally, we showed that time of injury was not associated with worsening body composition and CMD profile, inconsistent with prior literature.

Significant loss in muscle mass from atrophic wasting is associated with both decreased strength and ectopic fatty deposits in skeletal muscle5,40. Also intramuscular fat (IMF) or intermuscular adipose tissue (IMAT) deposition and muscle loss perhaps represent a driver for loss of insulin sensitivity, and it increases over time in chronic SCI41,42. These changes in muscle composition and whole body composition that result from inactivity may underlie alterations in carbohydrate and lipid metabolism that contribute to fat accumulation and insulin resistance5,43. Moreover, visceral adipocytes and adipokines secrete and recruit non-esterified fatty acids that systemically contribute to elevated LDL, lower HDL, and ultimately infiltrate skeletal muscle that may perpetuate insulin resistance8,44.

Greater insulin resistance

Insulin resistance is believed to precede diagnosis of DM, ischemic heart disease, stroke by 10–15 years, representing an insidious form of metabolic change that underlies non-communicable disease of aging and cardiovascular dysfunction29. Those with BMI ≥ 22 had Matsuda value near 7 while those with BMI < 22 had value of 2.98. Additionally, HOMA Index estimates hepatic influence of insulin resistance where values greater than 2.0 indicate insulin resistance45. Those with BMI ≥ 22 had Matsuda greater than 2.0, whereas those with BMI < 22 did not. Baseline insulin levels and c-peptide were also significantly higher in those with obesity.

Skeletal muscle represents 70% of the reservoir for circulating glucose46. Physical exercise is also known to recruit translocation of GLUT4 receptors and increased glucose uptake47. Those with SCI have greater risk of developing insulin resistance largely due to significantly decreased skeletal muscle mass (shown to have nearly 50% cross-sectional area of muscle loss below level injury within 6 weeks)48. Given this higher risk of insulin resistance following SCI, future studies may evaluate the need for different cutoffs in patients with SCI regarding HOMA or Matsuda.

Increased inflammation

Inflammation has been implicated in metabolic dysfunction in obesity. Increases in fat mass induce inflammatory biomarkers that interfere with insulin signaling and trigger metabolic syndrome5,49. SCI is associated with higher systemic inflammatory profile even in absence of acute infection39. CRP is associated with CMD in SCI and has been specifically associated with higher risk of cardiac events19,50. CRP was positively correlated with BMI, total, and truncal fat in the present study, consistent with prior literature that obesity relates to chronic inflammatory state. However, IL-6 and CRP were not observed to correlate with time of injury or body composition, or group analysis of BMI or time of injury.

Serum IL-8 and MCP-1 are chemokines that are increased in relation to obesity and diabetes, and known to contribute to insulin resistance, chronic inflammation and metabolic dysfunction11,51,52. Exercise regimens have been shown to reduce serum MCP-1 and IL-8 over time53. They have both been implicated in atherosclerosis and trigger adhesion to vascular endothelium as potential active roles in atherogenesis54. In the correlational analysis, total and truncal fat correlated with HbA1c and glucose OGTT. HbA1C was significantly positively correlated with IL-8. This correlation is consistent with prior literature in the able-bodied population that DM has an association with systemic IL-8 elevation55. The role of IL-8 in insulin sensitivity is unclear.

We also demonstrate an increase in MCP-1 with lean muscle mass. IMAT secretes MCP-1 that directly mediates insulin resistance and inflammatory cascades in obesity56,57,58. DEXA has been shown to be less accurate in determining truncal lean muscle mass as it has been proven to be difficult to separate from viscera and fluids in the trunk region5,59. Higher abdominal adiposity correlates with higher lean muscle mass in older adults60. DEXA overestimates truncal lean mass and may include VAT or trunk central adiposity61. Moreover, DEXA has not been able to isolate or differentiate IMAT from lean muscle mass and has been incorrectly calculated in the lean muscle mass estimates62. The higher the IMAT, the higher the lean muscle mass estimate. IMAT is thought to be metabolically active, and our study demonstrates the likely candidate adipokines that lead to insulin resistance, all correlating positively with lean muscle mass and therefore IMAT.

MIP-1b is implicated as an adipokine of visceral adipose tissue and correlates with BMI, insulin resistance, and dyslipidemia63,64. It is possible that lean muscle mass on DEXA may erroneously include ectopic intermuscular adipose tissue—or intramuscular adipose tissue—that is observed to positively correlate with MCP-1, IL-8, and MIP-1b and therefore contribute to inflammatory pathogenesis of metabolically unhealthy IMAT.

IL-27 has recently been implicated in gut barrier health65,66. Constipation and bowel dysfunction may contribute to a pathogenic imbalance in the gut microbiome67,68. Bowel dysfunction may increase leaky gut and bacterial translocation from the gut68. Neurogenic bowel dysfunction score (NBDS) represents a validated assessment of bowel dysfunction in SCI such that the higher the score, the more dysfunction67. Further, it may act as a proxy of gut motility that has been shown to predict the negatively affected quality of life67. Positive correlation of IL-27 and NBDS indicates a potential relationship with inflammation. IL-27 has been associated with the role of upholding gut intestinal wall lining integrity and repair and pathogen defense65. SCI induces gut dysmotility with impairment of the enteric nervous system prolonging bowel transit time and increasing constipation8,26. It is unclear if this correlates with alterations in gut microbiome. Further investigation of the gut microbiome in assessing microbiome profiles in those with SCI may elucidate influence and risk of systemic inflammation and body composition profiles that increase risk of CMD.

Strengths and limitations

The current work is based on a single-institution cross-sectional study on chronic SCI, evaluating multiple aspects of physiological function. Small sample size, particularly in those with paraplegia is a limitation of the subgroup analysis related to injury level. Another limitation of the present study is its correlational arm design, which decreases generalizability. Demographic homogeneity also limits generalizability of findings. A prospective study including an able-bodied control group may enhance significance of findings and delineate differences between patients with SCI and able-bodied matches. To identify key variables that initiate or play larger or initial roles in metabolic dysregulation, future studies may implement randomized groups to evaluate the effects of diet and exercise independently. Additionally, lack of detailed information regarding patient sleep, pain, medication use, and diet are limitations of the present study that may have influenced measured variables on body composition and inflammation. Interventions to improve body composition with efforts related to nutrition, sleep, pharmacy, and rehabilitation that improve voluntary movement with technological aids including spinal cord epidural stimulation may improve metabolic profiles and stave off CMD risk in this particularly vulnerable population27,69,70.

Conclusion

Following SCI, total and truncal fat appear to be associated with cardiometabolic risk factors, including dyslipidemia, obesity, and elevated inflammatory markers, including IL-8 and CRP. BMI ≥ 22, more than level of injury or time since injury, is linked to greater central obesity/VAT (% truncal fat, trunk mass), dyslipidemia (CMD risk factor), insulin resistance and sensitivity and other CMD risk factors. Level of injury does not appear to drive inflammation in peripheral blood or gut dysfunction. Given our findings, the impact of nutrition, exercise, sleep, and neuromodulation technologies targeting body composition changes could be explored to improve CMD risk profiles.

Transparency, rigor and reproducibility statement

The institutional review board (IRB) approved the present study with IRB# 16.0179. All participants were medically approved for enrollment in an outpatient, standardized program at the University of Louisville, Frazier Rehab Institute. Sixty-two individuals with chronic spinal cord injury were recruited and the following metrics were analyzed: body composition measured by DEXA scan, metabolic profile, lipids, hsCRP, a battery of inflammatory cytokines through serum sample. Dichotomized groups separated by BMI ≥ 22 and those with BMI < 22 as well as those with injury level above T1 and below T1 were analyzed. Continuous variables were summarized with median and interquartile range and compared with Wilcoxon Rank Sum test. Categorical variables were summarized with percentage and compared with Fisher’s Exact test. The significance level for outcomes comparisons was set to the Bonferroni adjusted value of 0.0004 (0.05/116 outcome comparisons). All tests were 2-sided. Statistical analyses were performed in SAS 9.4. All results are available upon request from readers.

Data availability

All data and statistics are available upon request. Correlational analyses are available as supplementary data in the manuscript submission. Data can be requested from Nicholas Dietz, nkd25@georgetown.edu.

References

Peterson, M. D. et al. Cardiovascular and metabolic morbidity following spinal cord injury. Spine J. 21 (9), 1520–1527. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.spinee.2021.05.014 (2021).

Zeilig, G. et al. Long-term morbidity and mortality after spinal cord injury: 50 years of follow-up. Spinal Cord. 38 (9), 563–566. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.sc.3101043 (2000).

Myers, J., Lee, M. & Kiratli, J. Cardiovascular disease in spinal cord injury: an overview of prevalence, risk, evaluation, and management. Am. J. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 86 (2), 142–152. https://doi.org/10.1097/PHM.0b013e31802f0247 (2007).

Garshick, E. et al. A prospective assessment of mortality in chronic spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord. 43 (7), 408–416. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.sc.3101729 (2005).

Gorgey, A. S. et al. Effects of spinal cord injury on body composition and metabolic profile - part I. J. Spinal Cord Med. 37 (6), 693–702. https://doi.org/10.1179/2045772314Y.0000000245 (2014).

Gorgey, A. S. & Dudley, G. A. Skeletal muscle atrophy and increased intramuscular fat after incomplete spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord. 45 (4), 304–309. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.sc.3101968 (2007).

Castro, M. J. et al. Influence of complete spinal cord injury on skeletal muscle cross-sectional area within the first 6 months of injury. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. Occup. Physiol. 80 (4), 373–378. https://doi.org/10.1007/s004210050606 (1999).

Farkas, G. J. & Gater, D. R. Neurogenic obesity and systemic inflammation following spinal cord injury: A review. J. Spinal Cord Med. 41 (4), 378–387. https://doi.org/10.1080/10790268.2017.1357104 (2018).

Farkas, G. J. & Gater, D. R. Energy expenditure and nutrition in neurogenic obesity following spinal cord injury. J. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2 (1), 11–13 (2020).

Buchholz, A. C. & Pencharz, P. B. Energy expenditure in chronic spinal cord injury. Curr. Opin. Clin. Nutr. Metab. Care. 7 (6), 635–639. https://doi.org/10.1097/00075197-200411000-00008 (2004).

Singh, R. et al. Longitudinal study of body composition in spinal cord injury patients. Indian J. Orthop. 48 (2), 168–177. https://doi.org/10.4103/0019-5413.128760 (2014).

Phillips, A. A. & Krassioukov, A. V. Contemporary cardiovascular concerns after spinal cord injury: mechanisms, maladaptations, and management. J. Neurotrauma. 32 (24), 1927–1942. https://doi.org/10.1089/neu.2015.3903 (2015).

Raguindin, P. F. et al. Cardiometabolic risk profiling during spinal cord injury rehabilitation: A longitudinal analysis from the Swiss spinal cord injury (SwiSCI) cohort. PM R. 15 (6), 715–730. https://doi.org/10.1002/pmrj.12857 (2023).

Bauman, W. A. et al. The effect of residual neurological deficit on oral glucose tolerance in persons with chronic spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord. 37 (11), 765–771. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.sc.3100893 (1999).

Raguindin, P. F. et al. Body composition according to spinal cord injury level: A systematic review and Meta-Analysis. J. Clin. Med. 10 (17). https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm10173911 (2021).

Laughton, G. E. et al. Lowering body mass index cutoffs better identifies obese persons with spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord. 47 (10), 757–762. https://doi.org/10.1038/sc.2009.33 (2009).

Schmidt, F. M. et al. Inflammatory cytokines in general and central obesity and modulating effects of physical activity. PLoS One. 10 (3), e0121971. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0121971 (2015).

Sun, X. et al. Multiple organ dysfunction and systemic inflammation after spinal cord injury: a complex relationship. J. Neuroinflammation. 13 (1), 260. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12974-016-0736-y (2016).

Nash, M. S. et al. Identification and management of cardiometabolic risk after spinal cord injury: clinical practice guideline for health care providers. Top. Spinal Cord Inj Rehabil. 24 (4), 379–423. https://doi.org/10.1310/sci2404-379 (2018).

Alam, I., Ng, T. P. & Larbi, A. Does inflammation determine whether obesity is metabolically healthy or unhealthy? The aging perspective. Mediators Inflamm. 2012 (456456). https://doi.org/10.1155/2012/456456 (2012).

Popa, C. et al. The role of TNF-alpha in chronic inflammatory conditions, intermediary metabolism, and cardiovascular risk. J. Lipid Res. 48 (4), 751–762. https://doi.org/10.1194/jlr.R600021-JLR200 (2007).

van Hall, G. et al. Interleukin-6 stimulates lipolysis and fat oxidation in humans. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 88 (7), 3005–3010. https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2002-021687 (2003).

Lee, M. Y. et al. C-reactive protein, metabolic syndrome, and insulin resistance in individuals with spinal cord injury. J. Spinal Cord Med. 28 (1), 20–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/10790268.2005.11753794 (2005).

Hardy, O. T. et al. Body mass index-independent inflammation in omental adipose tissue associated with insulin resistance in morbid obesity. Surg. Obes. Relat. Dis. 7 (1), 60–67. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soard.2010.05.013 (2011).

Bannerman, C. A. et al. The gut-brain axis and beyond: Microbiome control of spinal cord injury pain in humans and rodents. Neurobiol. Pain. 9 (100059). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ynpai.2020.100059 (2021).

Dietz, N. et al. Longitudinal trends and prevalence of bowel management in individuals with spinal cord injury. Top. Spinal Cord Inj Rehabil. 27 (4), 53–67. https://doi.org/10.46292/sci21-00008 (2021).

Boakye, M. et al. Spinal cord epidural stimulation for motor and autonomic function recovery after chronic spinal cord injury: A case series and technical note. Surg. Neurol. Int. 14 (87). https://doi.org/10.25259/SNI_1074_2022 (2023).

ElSayed, N. A. et al. 2. Classification and diagnosis of diabetes: standards of care in Diabetes-2023. Diabetes Care. 46 (Suppl 1), S19–S40. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc23-S002 (2023).

Malagon-Soriano, V. A. et al. Surrogate indices of insulin resistance using the Matsuda index as reference in adult men-a computational approach. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne). 15 (1343641). https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2024.1343641 (2024).

Jones, L. M., Legge, M. & Goulding, A. Healthy body mass index values often underestimate body fat in men with spinal cord injury. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 84 (7), 1068–1071. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0003-9993(03)00045-5 (2003).

Savic, G. et al. Causes of death after traumatic spinal cord injury-a 70-year British study. Spinal Cord. 55 (10), 891–897. https://doi.org/10.1038/sc.2017.64 (2017).

Nelson, M. D. et al. Metabolic syndrome in adolescents with spinal cord dysfunction. J. Spinal Cord Med. 30 (Suppl 1), S127–S139. https://doi.org/10.1080/10790268.2007.11754591 (2007).

Nuhlicek, D. N. et al. Body composition of patients with spinal cord injury. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 42 (9), 765–773 (1988).

Spungen, A. M. et al. Factors influencing body composition in persons with spinal cord injury: a cross-sectional study. J. Appl. Physiol. (1985). 95 (6), 2398–2407. https://doi.org/10.1152/japplphysiol.00729.2002 (2003).

Gupta, N., White, K. T. & Sandford, P. R. Body mass index in spinal cord injury -- a retrospective study. Spinal Cord. 44 (2), 92–94. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.sc.3101790 (2006).

Moussavi, R. M. et al. Dietary and serum lipids in individuals with spinal cord injury living in the community. J. Rehabil Res. Dev. 38 (2), 225–233 (2001).

Cirnigliaro, C. M. et al. Predicting cardiometabolic risk from visceral abdominal adiposity in persons with chronic spinal cord injury. J. Clin. Densitom. 24 (3), 442–452. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jocd.2021.03.010 (2021).

Gorgey, A. S. et al. Influence of motor complete spinal cord injury on visceral and subcutaneous adipose tissue measured by multi-axial magnetic resonance imaging. J. Spinal Cord Med. 34 (1), 99–109. https://doi.org/10.1179/107902610X12911165975106 (2011).

Liang, H. et al. Different risk factor patterns for metabolic syndrome in men with spinal cord injury compared with able-bodied men despite similar prevalence rates. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 88 (9), 1198–1204. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmr.2007.05.023 (2007).

Snel, M. et al. Ectopic fat and insulin resistance: pathophysiology and effect of diet and lifestyle interventions. Int. J. Endocrinol. 2012 (983814). https://doi.org/10.1155/2012/983814 (2012).

Bauman, W. A. & Spungen, A. M. Disorders of carbohydrate and lipid metabolism in veterans with paraplegia or quadriplegia: a model of premature aging. Metabolism 43 (6), 749–756. https://doi.org/10.1016/0026-0495(94)90126-0 (1994).

Elder, C. P. et al. Intramuscular fat and glucose tolerance after spinal cord injury–a cross-sectional study. Spinal Cord. 42 (12), 711–716. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.sc.3101652 (2004).

Raal, F. J. Pathogenesis and management of the dyslipidemia of the metabolic syndrome. Metab. Syndr. Relat. Disord. 7 (2), 83–88. https://doi.org/10.1089/met.2008.0079 (2009).

Shulman, G. I. Cellular mechanisms of insulin resistance. J. Clin. Invest. 106 (2), 171–176. https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI10583 (2000).

Khalili, D. et al. Are HOMA-IR and HOMA-B good predictors for diabetes and pre-diabetes subtypes? BMC Endocr. Disord. 23 (1), 39. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12902-023-01291-9 (2023).

Freeman, A. M., Acevedo, L. A. & Pennings, N. Insulin Resistance (In: StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL), (2024).

Bird, S. R. & Hawley, J. A. Update on the effects of physical activity on insulin sensitivity in humans. BMJ Open. Sport Exerc. Med. 2 (1), e000143. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjsem-2016-000143 (2016).

Castro, M. J. et al. Influence of complete spinal cord injury on skeletal muscle within 6 mo of injury. J. Appl. Physiol. (1985). 86 (1), 350–358. https://doi.org/10.1152/jappl.1999.86.1.350 (1999).

Manns, P. J., McCubbin, J. A. & Williams, D. P. Fitness, inflammation, and the metabolic syndrome in men with paraplegia. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 86 (6), 1176–1181. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmr.2004.11.020 (2005).

Ridker, P. M. et al. C-reactive protein and other markers of inflammation in the prediction of cardiovascular disease in women. N Engl. J. Med. 342 (12), 836–843. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM200003233421202 (2000).

Duarte, G. V. et al. Osteopontin, CCL5 and CXCL9 are independently associated with psoriasis, regardless of the presence of obesity. Cytokine 74 (2), 287–292. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cyto.2015.04.015 (2015).

Borges, M. D. et al. Relationship between Proinflammatory cytokines/chemokines and adipokines in serum of young adults with obesity. Endocr. Metab. Immune Disord Drug Targets. 18 (3), 260–267. https://doi.org/10.2174/1871530318666180131094733 (2018).

Troseid, M. et al. Exercise reduces plasma levels of the chemokines MCP-1 and IL-8 in subjects with the metabolic syndrome. Eur. Heart J. 25 (4), 349–355. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ehj.2003.12.006 (2004).

Gerszten, R. E. et al. MCP-1 and IL-8 trigger firm adhesion of monocytes to vascular endothelium under flow conditions. Nature 398 (6729), 718–723. https://doi.org/10.1038/19546 (1999).

Cimini, F. A. et al. Circulating IL-8 levels are increased in patients with type 2 diabetes and associated with worse inflammatory and cardiometabolic profile. Acta Diabetol. 54 (10), 961–967. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00592-017-1039-1 (2017).

Suka Aryana, I. G. P. et al. The important role of intermuscular adipose tissue on metabolic changes interconnecting obesity, ageing and exercise: A systematic review. TouchREV Endocrinol. 19 (1), 54–59. https://doi.org/10.17925/EE.2023.19.1.54 (2023).

Dietze, D. et al. Inhibitor kappab kinase is involved in the paracrine crosstalk between human fat and muscle cells. Int. J. Obes. Relat. Metab. Disord. 28 (8), 985–992. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ijo.0802701 (2004).

Lim, J. P. et al. Inter-muscular adipose tissue is associated with adipose tissue inflammation and poorer functional performance in central adiposity. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 81 (1–7). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.archger.2018.11.006 (2019).

Chaves, L. et al. Assessment of body composition by whole-body densitometry: what radiologists should know. Radiol. Bras. 55 (5), 305–311. https://doi.org/10.1590/0100-3984.2021.0155-en (2022).

Raghupathy, R. et al. Higher abdominal adiposity is associated with higher lean muscle mass but lower muscle quality in middle-aged and older men and women: the Framingham heart study. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 35 (7), 1477–1485. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40520-023-02427-6 (2023).

Rankin, K. C., O’Brien, L. C. & Gorgey, A. S. Quantification of trunk and android lean mass using dual energy x-ray absorptiometry compared to magnetic resonance imaging after spinal cord injury. J. Spinal Cord Med. 42 (4), 508–516. https://doi.org/10.1080/10790268.2018.1438879 (2019).

Villedon de Naide, M. et al. Assessment of intramuscular fat and correlation with body composition in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and spondyloarthritis: A pilot study. Nutrients 13 (12). https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13124533 (2021).

Maury, E. et al. Effect of obesity on growth-related oncogene factor-alpha, thrombopoietin, and tissue inhibitor metalloproteinase-1 serum levels. Obes. (Silver Spring). 18 (8), 1503–1509. https://doi.org/10.1038/oby.2009.464 (2010).

Maury, E. et al. Adipokines oversecreted by omental adipose tissue in human obesity. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 293 (3), E656–E665. https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpendo.00127.2007 (2007).

Lin, C. H. et al. Gut epithelial IL-27 confers intestinal immunity through the induction of intraepithelial lymphocytes. J. Exp. Med. 218 (11). https://doi.org/10.1084/jem.20210021 (2021).

Andrews, C. et al. IL-27 induces an IFN-like signature in murine macrophages which in turn modulate colonic epithelium. Front. Immunol. 14 (1021824). https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2023.1021824 (2023).

Krogh, K. et al. Neurogenic bowel dysfunction score. Spinal Cord. 44 (10), 625–631. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.sc.3101887 (2006).

Camilleri, M. Leaky gut: mechanisms, measurement and clinical implications in humans. Gut 68 (8), 1516–1526. https://doi.org/10.1136/gutjnl-2019-318427 (2019).

Mesbah, S. et al. Predictors of volitional motor recovery with epidural stimulation in individuals with chronic spinal cord injury. Brain 144 (2), 420–433. https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/awaa423 (2021).

Harkema, S. J. et al. Epidural spinal cord stimulation training and sustained recovery of cardiovascular function in individuals with chronic cervical spinal cord injury. JAMA Neurol. 75 (12), 1569–1571. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaneurol.2018.2617 (2018).

Funding

Open access funding provided by Uppsala University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

ND contributed in idea origination, manuscript drafting, and final draft modifications. MBo: contributed to idea origination, resource contribution to study organization and staff, statistics, overseeing. MBj: drafting of manuscript, resource contribution to study organization and staff, statisticsSB: drafting of manuscript, resource contribution to study organization and staff, statisticsBU: was lead on statistics, including drating methods section, drafting of manuscript, and creation of tables. SM: oversaw the team and contributed to initial drafting and final draft of manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Dietz, N., Boakye, M., Bjurström, M.F. et al. Obesity in chronic spinal cord injury is associated with poorer body composition and increased risk of cardiometabolic disease. Sci Rep 15, 29073 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-13593-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-13593-0