Abstract

While the human population is increasing globally, the sustainability of ecosystem services is declining. Okalma Natural Forest Reserve in Sudan hosts high woody plant species richness that support ecosystem services, soil health, and local livelihood. This study aims to assess the relationship between woody plant species richness, carbon stock, dendrometric features, soil chemical properties, recreation services, and income sources. Data were collected from 178 circular sample plots with a radius of 17.84 m (area of 1000 m3 each) along 17 transect lines, complemented by 510 questionnaires and soil analysis. We recorded 30 woody species (tree and shrubs), with species richness positively correlated with carbon stock (R2 = 0.88), tree height (R2 = 0.82) and recreation preferences (R2 = 0.90), but negatively correlated with soil sodium and nitrogen (R2 = - 0.91). Importance value index (IVI), basal area, and seedling density varied significantly (P < 0.05) among sites. Outdoor recreation activities such as enjoying fresh air and forest fruit were preferred over hunting and games. However, the high dependence on non-timber forest products highlights the need for sustainable use and industrialization of these resources. We recommend conserving species with low density, enhancing recreation facilities, and maintaining soil health for sustainable management of the reserve.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Forest ecosystems, including natural forests and plantations, are the prime carbon sinks in the earth with significant contribution to global nutrient cycles1,2, on plant biodiversity and carbon sequestration potential of plant forest3, elements flow4,5, and weather regulation6. They play a vital and indispensable role in the atmosphere by reducing greenhouse gases and CO2 concentration 7,8. However, deforestation, rangeland degradation, and land use changes accelerate the release of CO2 and contribute significantly to the global warming crisis, deterioration of soil health, and species richness decline9,10,11. Such destructive practices disturb the forest tree diversity and distribution as well as reducing their ability to sequestrate and store carbon12,13,14. Several environmental factors too affect the ecosystem services including carbon stock in biomass and soils of tree-based ecosystem15,16. Additionally, these stresses call for informative studies toward a better understanding of the composition and structure of forest tree populations and the change-driving factors. Moreover, soil chemical properties such as organic carbon and nitrogen are strongly influenced by tree species richness and composition17, resulting in limited regeneration and ecosystem resilience. Therefore, understanding the linkages between woody plant species richness, soil health, and ecosystem services is critical for sustainable forest management.

The species diversity can significantly differ among the forests and within a site in the forest. While the description of tree distribution patterns forms a key step for the conceptualization of their responses to the surrounding environment18,19,20, different factors, including site heterogeneity, seed bank, regeneration efficiency, and inter and intra-specific species competition, could interrupt this dynamic and limit its sustainability21,22,23,24,25. Likewise, species richness and abundance can vary from one site to another based on the spatial distribution of the woody species and site characteristics24,26,27,28,29. Therefore, for modeling biodiversity trends over a specific area, it is necessary to understand their spatial distribution and density. This information is important for sustainable forest management and species conservation, especially for the natural forests in Sudan.

Natural forests in Sudan are the major pillars of development and the local community needs satisfaction, particularly in remote areas and marginalized sites30,31. These forest resources benefit both human and animal by providing a variety of goods and services32,33. Meanwhile, for a long time, communities have benefited both ecologically and economically from plantations, biosphere reserves, natural forests and other protected areas34, in the form of food, medicine, livestock fodder, fruits and many others. Overall, forest resources, particularly non-wood forest products contribute over 50% to rural household income in Sudan35. Consequently, forest resources support more than 65% of the rural livelihood in Blue Nile, Sinnar, and Gedaref states26,36,37, and 75% in Darfur and Kordofan regions11,38,39 based on their availability, diversity and type of forest resources collected. Simultaneously, these natural forests not only host diversified plants but animals as well40. To regulate and sustain such utilization in natural forests, up-to-date information on the growing stock, species richness, dendrometric parameter characteristics and variability are urgently needed.

Okalma Natural Forest Reserve (ONFR) is among the largest natural forests in southeastern Sinnar State, with diversified woody plants and grasses41. The forest bordered three villages, which are Hegeir, Lakandi, and Kardous42. It is a main provider of fodder, non-timber forest products, timber, and medicinal products to the villagers near the forest41,43. The local community around this reserve has a huge stock of livestock, particularly goats, cows, and camels. While cows are mainly grazers44,45, goats and camels are by nature browsers46,47,48. Moreover, many families from Lakandi and Hegeir are farming near the reserve, planting sorghum, sesame, millet, sunflower, and cotton42,49. With all these activities within and around the reserve information regarding the status of the species’ richness and distribution is limited. Therefore, this study bridged this gap by analyzing the interlinkages between species richness, locals’ livelihood, and dendrometric features in Okalma natural forest reserve. In contrast, it aims to assess the relationship between woody plant species richness, carbon stock, dendrometric features, soil chemical properties, recreation services, and income sources. To achieve these objectives the following questions were addressed; 1) how many woody species present in the ONFR?, 2) is there variation in basal area, height, volume among woody species?, 3) is there any relationship between species richness and species characteristics as well as carbon stock?, 4) is there relation between species richness and recreational value and forest products?, 5) what is the relation between species richness and soil properties?, 6) what are the respondents perception income generation from forest products?, and 7) is there variation between seedling, sapling and mature tree density in the forest?. We argue that the findings of this study will enrich the country’s database and form a baseline for further detailed studies towards the sustainable management of forest resources in Sudan and similar ecosystems in the continent.

Materials and methods

Study area

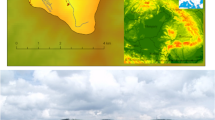

The study was conducted in ONFR, which is located in Sinnar State at latitude 12º 30ʹ 00ʺ N and 12º 40ʹ 00ʺ N, and longitude 34º 16ʹ 00ʺ E and 34º 24ʹ 00ʺ E (Fig. 1). It covers a total area of 17,640 ha with various fauna and flora populations41,43,48. The forest hosts various tree species including, Acacia mellifera, Acacia nilotica, Acacia nubica, Acacia senegal, Acacia seyal var seyal, Anogeissus leiocarpus, Balanites aegyptiaca, Dalbergia melanoxylon, Lannea fruticosa, Sterculia setigera, and Ziziphus spina-christi49,50,51.

Map of Okalma Natural Forest Reserve with sample plot sites where we studied the species richness variability and dendrometric parameters over a year. The map was created using ArcGIS version 10.5 and can be accessed (https://desktop.arcgis.com/en/system-requirements/10.5/arcgis-desktop-system-requirements.htm).

Topographically, the area is flat to semi-flat slowly sloping towards the north with small numbers of valleys and Mayas31,52,53. The soil types are generally cracky clay soils alternate with deeply cracked clay soils in the Mayas and sand soil in mountainous and bare land41,53. The forest lies at an average altitude of ~ 550 m above sea level, with a tropical savanna climate of > 750 mm mean annual rainfall, 28 °C mean minimum monthly temperature, and 41 °C mean maximum monthly temperature ~ . Moreover, the vegetation type includes deciduous woodland and savanna grassland plants.

Data collection

To assess the tree species composition and richness in ONFR, we used a systematic sampling approach with 17 transect lines spaced 200 m apart. In total 178 circular sample plots of 17.84 m radius (plot area = 1000 m2) were placed every 100 m along each transect42,54, starting 30 m from the forest boundary to avoid edge effect. Geotagging of each sample plot was done using a GPS. Within each plot, we classified the woody plant with ≥ 7 cm diameter at breast height (DBH) as mature trees, 3 – 7 cm as sapling48,55,56, and < 3 cm as seedlings. Conversely, DBH at 1.37 m above ground, tree height, crown width, and crown height were measured followed methods described by references 57,58. Diameter tape and caliper were used for measuring tree DBH, while Spiegel Relaskop and Suunto clinometer were used for tree height measurement59. Seedlings and saplings were counted within each plot. Soil samples were collected as composites of three subsamples (center and two opposite boundary points) of plot at 0 – 30 cm depth with an auger following method described by60. Then we analyzed the collected soil samples to explore the status of soil organic carbon (SOC), nitrogen (N), phosphorus (P), potassium (K) and sodium (Na) content. The inductively coupled plasma optimal emission spectrometry with nitric and perchloric acid was utilized for Na, K, and P concentration assessment60,61 Moreover, CN analyzer was used for N and SOC analysis.

The carbon stock was computed by multiplying the dry weight biomass with carbon content percent (Eqs. 1 and 2) as recommended by62,63.

The values of wood density and carbon content (%) were computed based on the World Agroforestry and the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change as adopted by62,63.

For the data of selected ecosystem services and income generation sources, we used the forest national corporation permit records of three years (2021 – 2023), key informants interview, questionnaires, and soil samples. For key informants interviews and questionnaires three villages (Hegeir, Kardous, and Lakandi) and two towns (Senga and Sinnar) were purposively selected. The selection process was based on their geographical position around forest, activities of local communities, and the forest national corporation (FNC) offices. All village leaders and available government officers and NGOs staff were considered as key informants. The key informants interview covered village leaders (n = 30), forest officers (n = 15), rangeland officers (n = 10), agricultural extension officers (n = 10), other government officers (n = 25), and NGOs staff (n = 15). Additionally, questionnaire and interview data were collected from 510 participants, whereas 270 were villagers and 240 were town residents. The questionnaire (supplementary file 1) addressed questions concerned with forest utilization, recreation, income sources, and disturbance. The questionnaire was developed based on a review of relevant literature and consultation with experts to ensure content validity. A pilot test was conducted with a sample of 20 participants to assess its reliability and clarity. In the meantime, the internal consistency of the questionnaire was evaluated using Cronbach’s alpha which yielded a value of 0.85, indicating good reliability. Minor adjustments were made based on the pilot results before administering the final version.

Data analysis

All data on tree species, DBH, height, soil samples, questionnaires were systematically compiled and organized into structured excel and SPSS sheet for subsequent analysis. The species’ richness was calculated as a total number of tree species identified per site48,64,65. Conversely, relative frequency, dominance, abundance, importance value index (IVI), tree basal area, and volume were computed using the equations. 48,66,67 presented in Table 1. Based on the values of IVI, we classified the tree species in ONFR into dominant (IVI ≥ 50), subdominant (IVI = 30–49), vulnerable (IVI = 10–29), and rare (< 10), as recommended by Mohammed et al37. We used analysis of variance in JAMOVI with Tukey’s Post Hoc test (α = 0.05) to compare the richness of species, importance value index (IVI), and dendrometric parameters across the study area, as recommended by authors68,69,70,71. While descriptive statistics were run in JAMOVI, homogeneity and normality tests were performed in Minitab and SPSS (Ver. 29), as reported by Gessesse et al.72, Moges and Taye73 and Mohammed et al.48. The regression equations in Minitab were run for various correlations and interlinkage analysis.

Results

Species diversity, carbon stock, and dendrometric features

Findings show that Okalma natural forest reserve has high species diversity by hosting 30 tree species varying from small-sized trees like A. leata and A. mellifera to large-sized ones such as A. digitata and T. laxiflora (Table 2). The tallest trees belonged to A. leiocarpus and H. thebiaca tree species, while the shortest ones are related to D. cinerea (Table 2). However, a strong positive correlation was observed between carbon stock and the woody plant species richness (R2 = 0.88, Fig. 2 A), and between total tree height and species richness (R2 = 0.82, Fig. 2 C), with significant differences across the forest (P = 0.01). On the other hand, a strong negative correlation was observed between species richness and diameter at breast height (R2 = − 0.77) (Fig. 2 B), and between species richness and crown width (R2 = − 0.82) (Fig. 2 D), while significantly difference at (P = 0.05). Additionally, Ximenia americana, Xeromphis nilotica, and Piliostigma reticulatum illustrated a critical conservation status by having the lowest relative abundance and importance value index values (Table 3). But the density of vulnerable and rare tree species exhibited no significant difference across the reserve (Fig. 3).

Mean population density (stem/ha) of adult trees, saplings, and seedlings of dominant, subdominant, vulnerable and rare tree species assessed in Okalma Natural Forest Reserve. Different letters above the bars illustrate significant differences between classes (dominant, subdominant, vulnerable, and rare) within the various stages of plant development across the reserve based on Tukey’s test (P < 0.05).

Species richness, recreation, and soil health

A significant variation was observed between recreation values among the respondents within the location and across the five locations (Fig. 4). The frequency of fresh air and forest fruits enjoyment as outdoor recreation activities were twice that of games and hunting, with significant differences between services as well as locations (F4, 495 = 72.1 and P < 0.01; F4, 495 = 88.2 and P = 0.01; F4, 495 = 63.7 and P = 0.02; F4, 495 = 58.5 and P = 0.04, respectively, (Fig. 4). Moreover, the correlations between the frequency of respondents preference and species richness, for watching birds, photographing nature, enjoying forest fruits, hunting activities, fresh air, and games, were strongly linked R2 > 0.9; β = 6.4 and P = 0.02; β = 5.4 and P = 0.03; β = 7.2 and P < 0.01; β = 4.7 and P = 0.04; β = 7.5 and P < 0.01; β = 7.1 and P = 0.01; respectively, Fig. 5). The findings of soil chemical properties elucidated negative correlations between soil nitrogen, sodium, and species richness with R2 = − 0.91 and R2 = − 0.77 respectively (Fig. 6 A&C). In contrast, a strong positive correlation was observed between species richness and soil organic carbon (R2 = 0.88, Fig. 6 B), species richness and potassium (R2 = 0.81, Fig. 6 D), and species richness and phosphorus (R2 = 0.83, Fig. 6 E).

Locals’ livelihood and income generation activities

The socio-demographic characteristics showed that 52% and 48% of the study participants were female and male, respectively (Fig. 7 A); and 30% of them were agro-pastoralists followed by non-timber forest products collectors (21%) and firewood producers (16%), (Fig. 7 B). A significant variation was observed in fruits and firewood collection among seasons and sites based on respondents’ perception (Fig. 8). Though the highest amount of collected fruits was observed in season 2020, firewood displayed an inverse trend with significant shift in 2022 (Fig. 8). Conversely, a significant negative correlation was observed between gum production and species richness among the study sites (Fig. 9).

Discussion

Species diversity, carbon stock and dendrometric features

In total 30 tree species was recorded in ONFR, which is strongly correlated with carbon stock and dendrometric features, and consistent with42,70,74,76. The observed woody plant species richness of ONFR is relatively lower compared to that of other reserves in Sudan such as 47 tree species was recorded in Abu Gadaf natural forest reserve37, and 56 tree species in Rashad natural reserved forest77, and 32 woody species in Geili riverine forest reserve78. While it is higher than Elgarrie forest reserve that recorded only 15 woody species79. Although, the number of species seems quite less at ONFR, most forests in Sudan harbor woody species/diversity within the reported ranges. These findings indicate the forests in Sudan are under severe threat from illegal felling and other anthropogenic disturbances. Similar issue has been addressed by several researchers in other natural forest reserve of Sudan too32,80. However, Musa and Sahoo81 argued that participation of local community is crucial in enhancing species diversity and achieving sustainable forest management. The communities involved in forest conservation efforts would ensure their conservation strategies aligned with local needs and priorities, and a sense of ownership82. The most dominant tree species in the reserve was A. senegal while other dominant species include A. seyal var. seyal, B. aegyptiaca, Z. spin-christi and C. hartmannianum (Table 3). These species are vital to Sudan’s culture and ecology and provide essential resources for the local communities. The IVI of a species can indicate its status in the ecosystem and may help in conservation efforts by identifying vulnerable or keystone species that requires special protection37,59. On the other hand, the strong positive relationship between species richness and carbon stock in ONFR illustrates that sites with high tree species abundance, height, and stocking density secure more carbon sink and hence better sequestration capacity. The researchers26,83,84,85,86 reported that biomass carbon stock varies between woody plants, perennials, and grasses; and is significantly influenced by the stand diversity, elevation, geographic location, disturbances, and the dominant plant group. Though trees with large crown width host diversified bird and epiphyte species58,87,88, they cover considerable land which is an area competitive factor to other woody species. Moreover, large crowns with vigorous fruit production usually lead to efficient natural regeneration and remarkable sapling recruitment within specific plant functioning groups60,74. Therefore, forests with mixed stand species, tall trees, and moderate disturbances effectively support the global efforts of biodiversity conservation, carbon sequestration, and climate change mitigation.

Species richness, recreation, and soil health

The results highlighted that recreation value varies within and between locations based on species richness, recreation activity, and visitor preference. Outdoor activities like enjoying the fresh air and forest fruits exhibited higher frequencies compared to games and hunting, which may result from their simplicity and no skill needs. These findings are in line with89,90,91. Sites with high species abundance and water sources attract more visitors and hence more recreation activities, particularly bird watching and nature photographing practices. Studies conducted by8,14,37,90 demonstrate that areas easily accessed and accommodated various fauna and flora species attain high recreation value, resilient ecosystems, and natural restoration. Accordingly, B. aegyptiaca, Z. spina-christi areas represent birds’ nest in Okalma Natural Forest Reserve of which attract tourists for bird watching. However, medium to large birds can play a significant role in seed dispersal and improve natural regeneration of plant species within and around areas.

Furthermore, with increases in tree species richness the density of nitrogen-fixing trees A. senegal and A. seyal decrease, which consistently affects the soil nitrogen content and increases the soil organic carbon in Okalma reserve. Studies illustrated that the amounts of soil nutrients in natural forests vary between sites based on the leaf litter-fall, litter-layer, site disturbance, and tree species60,92,93. Accordingly, maintaining sufficient nutrient contents for natural regeneration and seedling growth is directly associated with tree species, site richness, soil health, and stand density94,95,96,97. Though selective logging (a human disturbance) with low and medium intensity promotes the growth of some deciduous tree species like Scots pine98, other species like B. aegyptiaca is sensitive to such practice particularly at juvenile stage74. Thus, the variation between the pure stands of A. senegal and the mixed ones in Okalma forest calls for a detailed soil-species richness study for a deeper understanding of this relationship and comprehensive planning for sustainable management of the reserve and low soil sodicity levels. Additionally, such findings could positively contribute to ecosystem resilience and agroforestry practices in silvi-pastoral systems.

Locals’ livelihood and income generation activities

Non-timber forest products (NTFPs) form a vital source of household income in rural areas of Sudan. This study outcomes displayed that most people neighboring to the Okalma forest practice agriculture, livestock rearing, and NTFPs collection. The collected amount of NTFPs showed significant differences between seasons and across the locations, which can directly be attributed to the variations in collectors’ experience, market type, market price, and season length. Similarly, review by Musa et al35 reported that NTFPs contribute over 50% to Sudanese household with significant variation based on species diversity. On the other hand, a study by Musa et al.80 reported that the amount of NTFPs collection per household depends on family size and the number of family members engaged in collection. The big and populated cities like Senga and Sinnar host the largest NTFPs markets, hence high demand, and better prices compared to smaller villages like Hegeir and Kardous. Nevertheless, people with experience and indigenous knowledge are more in village and remote areas than urban and civilized ones99,100,101. This result highlights the significance of industrialization in NTFPs trade to enhance the income of local people through value-chain and product diversification. Such practice can make an evolution in NTFPs market and reduce the pressure on forest resources and species diversity. Moreover, the high proportion of NTFPs traders documents the importance of forest products in enhancing the local community’s livelihoods and the households’ welfare.

Conclusions

Our findings demonstrate that woody plant species richness in Okalma Natural Forest Reserve positively influence carbon sequestration, recreation value, and soil organic carbon, while reducing soil sodium and nitrogen level. Sites with higher diversity hosted more visitors and secured more ecosystem services. However, dependence on non-timber forest products remains high, underscoring the need for understanding harvesting and value chain development. We recommended conserving rare and over-exploited species, enhancing visitor facilities, and promoting agropastoralism to improve livelihoods and resilience of the Okalma Natural Forest Reserve.

Data availability

The dataset used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding authors on reasonable request.

References

Janssen, B. H. & Oenema, O. Global economics of nutrient cycling. Turk. J. Agric. For. 32, 165–176 (2008).

Lindenmayer, D. B. & Laurance, W. F. The ecology, distribution, conservation and management of large old trees. Biol. Rev. 92, 1434–1458. https://doi.org/10.1111/brv.12290 (2017).

Gogoi, A., Ahirwal, J. & Sahoo, U. K. Plant biodiversity and carbon sequestration potential of planted forests in Brahmaputra flood plains. J. Environ. Manag. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envman.2020.111671 (2020).

Ihwagi, F. W., Chira, R. M., Kironchi, G., Vollrath, F. & Douglas-Hamilton, I. Rainfall pattern and nutrient content influences on African elephants’ debarking behaviour in Samburu and Buffalo Springs National Reserves. Kenya. African Journal of Ecology 50, 152–159. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2028.2011.01305.x (2012).

Yang, H., Zhang, P., Zhu, T., Li, Q. & Cao, J. The characteristics of soil C, N, and P stoichiometric ratios as affected by geological background in a karst graben area. Southwest China. Forests 10, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.3390/f10070601 (2019).

Dai, Z. et al. Modeling carbon stocks in a secondary tropical dry forest in the Yucatan Peninsula, Mexico. Water Air Soil Pollut. 225, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11270-014-1925-x (2014).

Ibrahim, E., Paity, B., Hassan, T., Idris, E. & Yousif, T. Effect of tree species, tree variables and topography on CO2 concentration in Badous riverine forest reserve—Blue Nile. Sudan 5, 1–12 (2018).

Neya, T., Neya, O. & Abunyewa, A. A. Agroforestry parkland profiles in three climatic zones of Burkina Faso. Int. J. Biol. Chem. Sci. 12, 2119. https://doi.org/10.4314/ijbcs.v12i5.14 (2019).

Ibrahim, E. M. & Hassan, T. T. Factors affecting natural regeneration and distribution of trees species in El-Nour natural forest reserve. J. Nat. Res. Environ. Stud. 3, 16–21 (2015).

Romijn, E. et al. Assessing change in national forest monitoring capacities of 99 tropical countries. For. Ecol. Manag. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2015.06.003 (2015).

Yousif, T. A., Mohamed, A. R. A., Ibrahim, E. M. & Ahmed, F. E. Causes of bank erosion of Wadi Kaja Basin—West Darfur State, Sudan. J. Natl. Res. Environ. Stud. 3, 1–8 (2015).

Chaturvedi, R. K., Raghubanshi, A. S. & Singh, J. S. Effect of grazing and harvesting on diversity, recruitment and carbon accumulation of juvenile trees in tropical dry forests. For. Ecol. Manag. 284, 152–162. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2012.07.053 (2012).

Gebeyehu, G., Soromessa, T., Bekele, T. & Teketay, D. Carbon stocks and factors affecting their storage in dry Afromontane forests of Awi Zone, northwestern Ethiopia. J. Ecol. Environ. 43, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41610-019-0105-8 (2019).

Gorgens, E. B. et al. Resource availability and disturbance shape maximum tree height across the Amazon. Glob. Change Biol. 27, 177–189. https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.15423 (2021).

Ahirwal, J. et al. Patterns and driving factors of biomass carbon and soil organic carbon stock in the Indian Himalayan region. Sci. Total Environ. 770, 145292. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv2021.145292 (2021).

Sahoo, U. K., Singh, S. L., Gogoi, A., Kenye, A. & Sahoo, S. S. Active and passive soil organic carbon pools as affected by different land use types in Mizoram. Northeast India. PloS one 14(7), e0219969 (2019).

Mawblei, B., Sahoo, U. K. & Musa, F. I. Comparative study of physiochemical properties and microbial population in forest and shifting cultivation soil in Mizoram India. J. Sylva Indonesiana 8(01), 59–70 (2025).

Assogbadjo, A. E., Kakaï, R. L. G., Sinsin, B. & Pelz, D. Structure of Anogeissus leiocarpa Guill., Perr. natural stands in relation to anthropogenic pressure within Wari-Maro Forest Reserve in Benin. African J. Ecol. 48, 644–653. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2028.2009.01160.x (2010).

Kacholi, D. S. Analysis of structure and diversity of the Kilengwe forest in the Morogoro Region Tanzania. Int. J. Biodivers. https://doi.org/10.1155/2014/516840 (2014).

Simons, N. K. et al. National forest inventories capture the multifunctionality of managed forests in Germany. Forest Ecosyst. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40663-021-00280-5 (2021).

Anderson, T. M., Dong, Y. & Mcnaughton, S. J. Nutrient acquisition and physiological responses of dominant Serengeti grasses to variation in soil texture and grazing. J. Ecol. 94, 1164–1175. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2745.2006.01148.x (2006).

Blackham, G. V., Andri, T., Webb, E. L. & Corlett, R. T. Seed rain into a degraded tropical peatland in Central Kalimantan Indonesia. Biol. Conserv. 167, 215–223. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2013.08.015 (2013).

Hanief, M., Bidalia, A., Meena, A. & Rao, K. S. Natural regeneration dynamics of dominant tree species along an altitudinal gradient in three different forest covers of Darhal watershed in north western Himalaya ( Kashmir) India. Tropic. Plant Res. 3, 253–262 (2016).

Liu, J. et al. Spatial patterns and associations of tree species at different developmental stages in a montane secondary temperate forest of northeastern China. PeerJ 9, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.11517 (2021).

Zhang, P., Cui, Z., Liu, X. & Xu, D. Above-ground biomass and nutrient accumulation in ten eucalyptus clones in Leizhou Peninsula Southern China. Forests https://doi.org/10.3390/f13040530 (2022).

Alzubair, M. A. H. & Hamdan, S. A. M. Deterioration of Blue Nile forests and its ecological effects in the Gezira State Sudan. MOJ Ecol. Environ. Sci. 5, 34–40 (2020).

Erdenebileg, E. et al. Multiple abiotic and biotic drivers of long-term wood decomposition within and among species in the semi-arid inland dunes: a dual role for stem diameter. Funct. Ecol. 34, 1472–1484. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2435.13559 (2020).

Heym, M. et al. Utilising forest inventory data for biodiversity assessment. Ecol. Ind. 121, 107196. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2020.107196 (2021).

Sahoo, U. K. et al. Quantifying tree diversity, carbon stocks and sequestration potential for diverse land uses in Northeast India. Front. Environ. Sci. 9, 724950. https://doi.org/10.3389/fenvs.2021.724950 (2021).

FAO. Sudan’s Country Report contributing to The State of the World’s Biodiversity for Food and Agriculture. State of the world biodiversity for food and agriculture. Khartoum, (2015).

Hassan; Tag. In-depth analysis of Drivers of Deforestation & Forest Degradation. Sudan REDD+ Programme, Final Report (Vol. II). Khartoum, (2017)

Mohammed, E. M., Hamid, E. A., Ndakidemi, P. A. & Treydte, A. C. The stocking density and regeneration status of Balanites aegyptiaca in Dinder Biosphere Reserve, Sudan. Trees Forests People 8, 100259. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tfp.2022.100259 (2022).

Ghanbari, S., Sefidi, K., Kern, C. C. & Álvarez-Álvarez, P. Population structure and regeneration status of woody plants in relation to the human interventions, Arasbaran Biosphere Reserve. Iran. Forests 12(2), 191. https://doi.org/10.3390/f12020191 (2021).

Maua, J. O., MugatsiaTsingalia, H., Cheboiwo, J. & Odee, D. Population structure and regeneration status of woody species in a remnant tropical forest: A case study of South Nandi Forest Kenya. Global Ecol. Conserv. 21, e00820. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gecco.2019.e00820 (2020).

Musa, F. I. et al. Contribution of non-wood forest products for household income in rural area of Sudan—a review. J. Agri. Food Res. 14, 100801. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jafr.2023.100801 (2023).

Ahmed, A. T. & Desougi, M. A. The ecology of some gum tree species and their uses at Tozi natural forest, Sinnar State, Sudan. J. Natl. Res. Eviron. Stud. 6456, 29–35 (2014).

Mohammed, E. M. I., Hassan, T. T., Idris, E. A. & Abdel-Magid, T. D. Tree population structure, diversity, regeneration status, and potential disturbances in Abu Gadaf natural reserved forest Sudan. Environ. Challenges https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envc.2021.100366 (2021).

Abdelrahim, M. Contribution of non-wood forest products in support of livelihoods of rural people living in the area South of Blue Nile State, Sudan. Int. J. Agri. Forestry Fisheries 3, 189–194 (2015).

Ibrahim, G. A., Abdalla, N. I. & Fangama, I. M. Contributions of non-wood forest products to household food security and income generation in South Kordofan State, Sudan. Int. J. Curr. Microbiol. Appl. Sci. 4, 828–832 (2015).

Kutnar, L., Nagel, T. A. & Kermavnar, J. Effects of disturbance on understory vegetation across Slovenian forest ecosystems. Forests 10(11), 1048. https://doi.org/10.3390/f10111048 (2019).

Mohammed, E.M.I. Impact of land use practices on the natural forest in Dinder Biosphere Reserve and it’s surrounding areas—Sudan. University of Bahri (2019).

Hassan, T. T., Mohammed, E. M. I. & Magid, T. D. A. Exploring the current status of forest stock in the areas bordering Dinder Biosphere Reserve, Sudan. J. Forestry Natl. Res. 1, 11–24 (2022).

Hassan, T.T. The use of non-timber forest products as potential adaptation measures in the Sudan’s forestry sector. University of Bahri (2019).

Dunne, T., Western, D. & Dietrich, W. E. Effects of cattle trampling on vegetation, infiltration, and erosion in a tropical rangeland. J. Arid Environ. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaridenv.2010.09.001 (2011).

Kochare, T., Tamir, B. & Kechero, Y. Palatability and animal preferences of plants in small and fragmented land holdings the case of Wolayta Zone Southern Ethiopia. Agri. Res. Technol. Open Access J. https://doi.org/10.19080/artoaj.2018.14.555922 (2018).

Ball, L. & Tzanopoulos, J. Livestock browsing affects the species composition and structure of cloud forest in the Dhofar Mountains of Oman. Appl. Veg. Sci. 23, 363–376. https://doi.org/10.1111/avsc.12493 (2020).

Derebe, Y. & Girma, Z. Diet composition and preferences of Bohor reedbuck (Redunca redunca) in the compound of Alage College, Central Rift Valley of Ethiopia. Ecol. Evol. https://doi.org/10.1002/ece3.6939 (2020).

Mohammed, E. M. I., Elhag, A. M. H., Ndakidemi, P. A. & Treydte, A. C. Anthropogenic pressure on tree species diversity, composition, and growth of Balanites aegyptiaca in Dinder biosphere reserve Sudan. Plants 10, 1–18 (2021).

Hassan, T.T. Forest resource assessment for Transition Zone of Dinder Biosphere Reserve (DBR)—Sudan. Final report, August (2015). Khartoum, 2015

Elmekki, A.A. Towrds community’s involvement in integerated management in Dinder Biosphere Reserve, Sudan. University of Khartoum, 2008

Mahgoub, A.A.M. Changes in Vegetation Cover and Impacts of Human Population in Dinder National Park , Sudan During the Period from 1972 to 2013. A Thesis submitted to the Sudan Academy of Sciences in fulfillment of the requirements for Doctor of Philosophy in Wildlife sciences. Sudan Academy of Science (SAS), (2014).

Mohammed, E. M. I., Hamed, A. M. E., Ndakidemi, P. A. & Treydte, A. C. Illegal harvesting threatens fruit production and seedling recruitment of Balanites aegyptiaca in Dinder Biosphere Reserve Sudan. Global Ecol. Conserv. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gecco.2021.e01732 (2021).

Hassaballah, K., Mohamed, Y.A. & Uhlenbrook, S. The Mayas wetlands of the Dinder and Rahad: tributaries of the Blue Nile Basin (Sudan). The Wetland Book 1–13 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-6173-5

Ali, O. B., Ibrahim, E. M. & Abdelmagid, T. D. Detection of tree species dynamic changes on Savannah ecology through diameter at breast height, Case study Heglieg area, Sudan. J. Natl. Res. Environ. Stud. 3, 24–30 (2015).

Kikoti, I., Mligo, C. & Kilemo, D. The Impact of Grazing on Plant Natural Regeneration in Northern Slopes of Mount Kilimanjaro Tanzania. Open J. Ecol. 5, 266–273. https://doi.org/10.4236/oje.2015.56021 (2015).

Ligate, E. J., Wu, C. & Chen, C. Investigation of tropical coastal forest regeneration after farming and livestock grazing exclusion. J. Forestry Res. 30, 1873–1884. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11676-018-0792-5 (2019).

Ibrahim, E., Osman, E. & Idris, E. Modelling the relationship between crown width and diameter at breast height for naturally grown Terminalia tree species. Journal of Natural Resources and Environmental Studies 42–49 (2014).

Tetemke, B. A., Birhane, E., Rannestad, M. M. & Eid, T. Allometric models for predicting aboveground biomass of trees in the dry afromontane forests of Northern Ethiopia. Forests 10, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.3390/F10121114 (2019).

Musa, F. I., Mohammed, M. H., Fragallah, S. D., Adam, H. E. & Sahoo, U. K. Current status of tree species diversity at Abu Gadaf Natural Forest Reserve Blue Nile Region-Sudan. Vegetos 37(5), 1760–1771. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42535-024-00931-2 (2024).

Mohammed, E. M. I., Hammed, A. M. E., Minnick, T. J., Ndakidemi, P. A. & Treydte, A. C. Livestock browsing threatens the survival of Balanites aegyptiaca seedlings and saplings in Dinder Biosphere Reserve Sudan. J. Sustain. Forestry https://doi.org/10.1080/10549811.2021.1935279 (2021).

Hofhansl, F. et al. Climatic and edaphic controls over tropical forest diversity and vegetation carbon storage. Sci. Rep. 10, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-61868-5 (2020).

Yasin, E. H. E. & Mulyana, B. Spatial distribution of tree species composition and carbon stock in Tozi tropical dry forest, Sinnar State Sudan. Biodiversitas 23, 2359–2368 (2022).

Djomo, A. N. et al. Tree allometry for estimation of carbon stocks in African tropical forests. Forestry 89, 446–455. https://doi.org/10.1093/forestry/cpw025 (2016).

Chen, J. & Tang, H. Effect of grazing exclusion on vegetation characteristics and soil organic carbon of Leymus chinensis grassland in northern China. Sustainability (Switzerland) 8, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.3390/su8010056 (2016).

Hammond, M. E., Pokorný, R., Okae-Anti, D., Gyedu, A. & Obeng, I. O. The composition and diversity of natural regeneration of tree species in gaps under different intensities of forest disturbance. J. Forestry Res. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11676-020-01269-6 (2021).

Gebeyehu, G., Soromessa, T., Bekele, T. & Teketay, D. Species composition, stand structure, and regeneration status of tree species in dry Afromontane forests of Awi Zone, northwestern Ethiopia. Ecosyst. Health Sustain. 5, 199–215 (2019).

Maua, J. O., Tsingalia, H. M., Cheboiwo, J. & Odee, D. Population structure and regeneration status of woody species in a remnant tropical forest: a case study of South Nandi forest Kenya. Global Ecol. Conserv. 21, e00820. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gecco.2019.e00820 (2020).

Hasoba, A. M. M., Siddig, A. A. H. & Yagoub, Y. E. Exploring tree diversity and stand structure of savanna woodlands in southeastern Sudan. J. Arid. Land 12, 609–617. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40333-020-0076-8 (2020).

Idrissa, B. et al. Trend and structure of populations of balanites aegyptiaca in Parkland Agroforestsin Western Niger. Ann. Res. Rev. Biol. 22, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.9734/arrb/2018/38650 (2018).

Jayakumar, R. & Nair, K. K. N. Species diversity and tree regeneration patterns in Tropical Forests of the Western Ghats India. ISRN Ecol. https://doi.org/10.1155/2013/890862 (2013).

Ssegawa, P. & Kasenene, J. M. Medicinal plant diversity and uses in the Sango bay area, Southern Uganda. J. Ethnopharmacol. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jep.2007.07.014 (2007).

Gessesse, B., Bewket, W. & Bräuning, A. Determinants of farmers’ tree-planting investment decisions as a degraded landscape management strategy in the central highlands of Ethiopia. Solid Earth 7, 639–650. https://doi.org/10.5194/se-7-639-2016 (2016).

Moges, D. M. & Taye, A. A. Determinants of farmers’ perception to invest in soil and water conservation technologies in the North-Western Highlands of Ethiopia. Int. Soil Water Conserv. Res. 5, 56–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iswcr.2017.02.003 (2017).

Mohammed, E. M. I., Hamid, E. A. M., Ndakidemi, P. A. & Treydte, A. C. The stocking density and regeneration status of Balanites aegyptiaca in Dinder Biosphere Reserve Sudan. Trees, Forests People. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tfp.2022.100259 (2022).

Ibrahim, E. & Osman, E. Diameter at breast height-crown width prediction models for Anogeissus leiocarpus (DC) Guill & Perr and Combretum hartmannianum Schweinf. J. Forest Products Industries 3, 191–197 (2014).

Abdelkarim, H. A., Ahmed, D. A. M. D., Yagoub, Y. E. & Siddig, A. A. H. Composition, structure and regeneration status of Hyphaene thebaica (L.) Mart natural forests in dry lands of Sudan. Agric. Forestry J. 5, 75–81 (2021).

Eisawi, K. A., He, H., Shaheen, T. & Yasin, E. H. Assessment of tree diversity and abundance in rashad natural reserved forest, South Kordofan. Sudan. Open Journal of Forestry 11(01), 37. https://doi.org/10.4236/ojf.2021.111003 (2021).

Gurashi, N. A., Yasin, E. H. E. & Czimber, K. Changes in structure, tree species composition, and diversity of the Abu Geili Riverine forest reserve, Sinnar State, Sudan. Acta Silvatica Et Lignaria Hungarica Int. J. Forest Wood Environ. Sci. 20(2), 55–70 (2024).

Dafa-Alla, D. A. M. et al. Assessing trees diversity in Jebel Elgarrie Forest Reserve in the Blue Nile State, Sudan. J. forest Environ. Sci. 38(3), 174–183. https://doi.org/10.7747/JFES.2022.38.3.174 (2022).

Musa, F. I. et al. Value chain of Balanites aegyptiaca in North Kordofan State in Sudan. Afr. Crop Sci. J. 30(s1), 77–83. https://doi.org/10.4314/acsj.v30is1.7S (2022).

Musa, F. I. UK role of sustainable forest management in poverty reduction and livelihood improvement in Sudan. Rev. Int. J. Ecol. Environ. Sci. 49, 449–456 (2023).

Deb, D. et al. Evaluating the role of community-managed forests in carbon sequestration and climate change mitigation of Tripura, India. Water Air Soil Pollut. 232, 166. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11270-021-05133-z (2021).

Alemu, B. The role of forest and soil carbon sequestrations on climate change mitigation. Res. J. Agric. Environ. Manage 3, 492–505 (2014).

He, G. et al. Estimating carbon sequestration potential of forest and its influencing factors at fine spatial-scales: a case study of Lushan City in Southern China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19159184 (2022).

Matthew, N. K. et al. Carbon stock and sequestration valuation in a mixed dipterocarp forest of Malaysia. Sains Malaysiana 47, 447–455 (2018).

Ahirwal, J., Sahoo, U. K., Thangjam, U. & Thong, P. Oil palm agroforestry enhances crop yield and ecosystem carbon sink in northeast India: Implications for the United Nations sustainable development goals. Sustain. Produc. Consum. 30, 478–487. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.spc.2021.12.022 (2022).

Gebrehiwot, K. & Hundera, K. Species composition, plant community structure and natural regeneration status of Belete moist evergreen montane forest, Oromia regional state, Southwestern Ethiopia. Momona Ethiopian J. Sci. 6, 97. https://doi.org/10.4314/mejs.v6i1.102417 (2014).

Singh, S., Malik, Z. A. & Sharma, C. M. Tree species richness, diversity, and regeneration status in different oak (Quercus spp.) dominated forests of Garhwal Himalaya India. J. Asia-Pacific Biodiversity 9, 293–300. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.japb.2016.06.002 (2016).

Aksoy, Y., Çankaya, S. & Taşmektepligil, M. Y. The effects of participating in recreational activities on quality of life and job satisfaction. Univ. J. Edu. Res. 5, 1051–1058 (2017).

Franceschinis, C., Swait, J., Vij, A. & Thiene, M. Determinants of recreational activities choice in protected areas. Sustain. (Switzerland) 14, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14010412 (2022).

Regidor, S. C. G., Arroyo, R. A., Aclan, Q. A. J. E. & Azuelo, A. P. L. Preference and constraints on outdoor recreational activities: insights from hospitality management students. Int. J. Acad. Industry Res. 3, 145–164 (2022).

Treydte, A. C., Heitkönig, I. M. A., Prins, H. H. T. & Ludwig, F. Trees improve grass quality for herbivores in African savannas. Perspect. Plant Ecol. Evol. Syst. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ppees.2007.03.001 (2007).

Villela, D. M., Nascimento, M. T., Araga, L. E. O. C. & De, G. D. M. Effect of selective logging on forest structure and nutrient cycling in a seasonally dry Brazilian Atlantic forest. J. Biogeogr. 33, 506–516. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2699.2005.01453.x (2006).

Arosa, M. L. et al. Long-term sustainability of cork oak agro-forests in the Iberian Peninsula: a model-based approach aimed at supporting the best management options for the montado conservation. Ecol. Model. 343, 68–79. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolmodel.2016.10.008 (2017).

Gaisberger, H. et al. Diversity under threat: Connecting genetic diversity and threat mapping to set conservation priorities for Juglans regia L populations in Central Asia. Front. Ecol. Evol. https://doi.org/10.3389/fevo.2020.00171 (2020).

Kingazi, N., Petro, R., Mbwambo, J. R. & Munishi, L. K. Performance of Pinus patula in areas invaded by Acacia mearnsii in Sao Hill forest plantation, Southern Tanzania. J. Sustain. Forestry https://doi.org/10.1080/10549811.2020.1788952 (2020).

Mohammed, E. M. I., Harouna, D. V., Osman, E. H., Mohammed, E. M. I. & Fadlelmola, S. A. A. Causes and consequences of mother tree population decline in Fazara natural forest reserve, Sudan. J. Biodivers. Environ. Sci. 23, 189–209 (2023).

Sukhbaatar, G. et al. Which selective logging intensity is most suitable for the maintenance of soil properties and the promotion of natural regeneration in highly continental scots pine forests?—Results 19 years after harvest operations in Mongolia. Forests 10, 1–21. https://doi.org/10.3390/f10020141 (2019).

Beche, D., Gebeyehu, G. & Feyisa, K. Indigenous utilization and management of useful plants in and around Awash National Park Ethiopia. J. Plant Biol. Soil Health 3, 1–12 (2016).

Gebru, B. M., Wang, S. W., Kim, S. J. & Lee, W. K. Socio-ecological niche and factors affecting agroforestry practice adoption in different agroecologies of southern Tigray Ethiopia. Sustain. (Switzerland) 11, 1–19. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11133729 (2019).

John, E. et al. Modelling the impact of climate change on Tanzanian forests. Divers. Distrib. 26, 1663–1686. https://doi.org/10.1111/ddi.1315 (2020).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the staff of Forest National Corporation (FNC) in Sinnar State for their support and help during the fieldwork activities, the local communities in the study area for their collaboration and help during questionnaires and interviews, the soil department in the Faculty of Agricultural Sciences at the University of Gezira for soil analysis, and the Faculty of Forest Science and Technology for research permits.

Funding

This research received no specific funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

E. M. I. M.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Data curation, Formal analysis, Visualization, Writing- Original draft preparation; E. M. Mohammed: Data Curation, Analysis, Writing-Original draft, U.K. S: Supervision, Visualization, Validation, Writing- review and editing; F. I. M: Methodology, Visualization, Writing—review and editing. All authors reviewed the manuscript and agreed to submit it for publication.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval and consent to publish

This study was conducted in accordance with ethical research standards involving human participants. All respondents, including non-timber forest products collector participated voluntarily after being fully informed about the purpose and nature of the research. Informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to data collection. The confidentiality and anonymity of all respondents have been strictly maintained, and no personal identifiable information has been disclosed in this manuscript. However, as per the University of Gezira guidelines this kind of research is usually approved (which does not involve indigenous rights, knowledge and perspectives, collection of any specific traditional knowledge, potential harms to both humans and environment), is approved by the ethical committee without mandatory registration.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Mohammed, E.M.I., Mohammed, E.M.I., Sahoo, U.K. et al. Linking woody plant species richness with selected ecosystem services and dendrometric features in Okalma natural forest reserve. Sci Rep 15, 28751 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-13640-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-13640-w

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Influence of climatic variability on tree diversity and smallholders' income in the savanna ecosystem of Sudan

Discover Environment (2025)