Abstract

Rockfill concrete (RFC) is constructed by initially placing large rocks and then filling the inter-rock voids with high-flow Self-Compacting Concrete (SCC) to ultimately form a complete concrete structure. The use of large-size rocks makes the structure of the interface transition zones and rocks interactions within RFC different from those of conventional concrete. The effect of the new internal structure on the overall mechanical performance of RFC is unclear. Moreover, the size of specimens for physical testing of RFC is much larger than that of conventional concrete, which hinders the test. This paper mainly utilizes numerical methods to carry out the related research. A three-dimensional mesoscopic finite element model (FEM) containing the rock, SCC, ITZ, and aggregate contact unit(ACU) between the rocks is established and validated combined with the experiments. After that, numerical modeling was used to investigate the effects of single changes in ITZ properties, aggregate properties and internal defects of aggregates on the uniaxial compressive properties of RFC. The results demonstrate that RFC’s uniaxial compressive performance increases with enhanced ITZ mechanical properties, although the role of ITZ in RFC differs from that in conventional concrete. RFC’s uniaxial compressive performance also improves with increasing aggregate mechanical properties, showing a strong linear correlation. The influence of aggregate properties on RFC is more significant than that of ITZ, highlighting RFC’s greater dependence on aggregate characteristics. Internal defects within the aggregate weaken its performance, thereby reducing RFC’s uniaxial compressive strength. As porosity increases, the degradation in RFC performance becomes more pronounced.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Rock-filled concrete (RFC) is an innovative concrete material1, constructed by first stacking aggregates with diameters between 300–1000mm and subsequently filling the voids in this rock skeleton with highly flowable self-compacting concrete (SCC)2. Upon SCC solidification, a complete and dense concrete structure is formed. RFC is widely used in large-scale concrete projects(especially dam construction) due to its advantages, including reduced cement usage, low hydration heat, high construction efficiency, and environmental friendliness1,3.

At the mesoscale, concrete is considered a three-phase composite material comprising a mortar matrix, aggregate, and the interfacial transition zone (ITZ) between them4,5,6,7,8. The ITZ, being the weakest link, typically has a thickness of about 50 μm9,10,11,12 and exhibits mechanical properties that are only 0.4–1.0 times those of the mortar13,14,15. Although the ITZ occupies a small volume within concrete, its unique structure and limited strength make it prone to crack initiation and propagation, which can reduce the concrete’s overall mechanical performance16,17. Thus, the influence of the ITZ on concrete’s macroscopic properties cannot be neglected. Sun-Myung Kim et al.5, using a plastic-damage coupling model, demonstrated that increased ITZ thickness enhances the brittleness of concrete. Similarly, studies have shown that increasing ITZ strength improves the uniaxial compressive strength of concrete, but once ITZ strength reaches a threshold (approximately 0.7–0.8 times the mortar matrix strength), it is no longer considered the weakest phase18,19,20,21. Most of this research, however, has focused on conventional concrete.

For RFC, the effect of ITZ properties on overall performance remains underexplored, with existing studies primarily examining the distinct behavior of ITZ within RFC. For instance, experiments by Xie et al.22 demonstrated that the rock framework provides an effective flow channel for SCC, achieving better filling and a denser ITZ structure compared to conventional concrete. He et al.23 investigated type I fracture behavior in ITZ under varying conditions (SCC strength, rock surface roughness, and stone powder content), finding that higher SCC strength and rock roughness increased the cracking load, while rock surface powder weakened ITZ fracture resistance. RFC’s ultra-large aggregates create larger ITZ internally, and, due to direct aggregate-to-aggregate contact in RFC, some regions lack ITZ entirely—characteristics that differ from conventional concrete. Further investigation is required to understand how variations in ITZ properties affect RFC’s overall mechanical performance.

The mechanical properties of concrete are influenced by factors such as aggregate content24,25,26, aggregate type27,28, aggregate gradation, and shape29,30,31. Some researchers have used numerical methods to investigate how variations in aggregate mechanical properties affect concrete performance. For instance, changes in aggregate strength do not alter concrete’s elastic modulus but exhibit a nonlinear positive correlation with compressive strength15,18,20,32; as aggregate strength increases, the proportion of cracks that bypass aggregates also rises19,20. Additionally, internal defects within natural aggregates, such as defects and cracks, impact the mechanical properties of the rock. Increasing defect size reduces the rock’s uniaxial compressive strength, and defect location significantly influences uniaxial compressive strength but has a lesser impact on the elastic modulus33. Under biaxial compression, defect interactions alter stress distribution and fracture behavior34, while variations in defect shapes lead to differing degrees of mechanical degradation, with defects amplifying compressive stress and contributing to collapse35.In conventional concrete, small aggregate sizes reduce the likelihood of internal porosity. However, in RFC, ultra-large aggregates may contain defects of varying sizes and shapes. Since large aggregates are a critical component of RFC, further study is needed to determine whether changes in aggregate mechanical properties and degradation due to internal defects could potentially diminish RFC’s overall macroscopic mechanical performance.

Due to the influence of large aggregates, physical testing conditions for RFC are often constrained, making it challenging to independently analyze the effects of ITZ and aggregate properties on overall performance using large RFC specimens. Mesoscale simulation, validated for accuracy, serves as an effective complementary method to experimentation, enabling further exploration of how material composition influences macroscopic performance36,37,38. Early work by Fang et al.39 introduced a rock compaction algorithm to construct a 3D two-phase RFC model with an aggregate stacking structure, though ITZ was not considered. Liang et al.40 developed a 3D finite element model simulating rock, HSCC, and ITZ, effectively predicting the evolution of RFC’s mechanical behavior over different curing ages. Later, Liang et al.41 proposed a mesoscale modeling method called spatial parameter reconstruction, allowing the placement of random polyhedral aggregates to form a three-phase mesoscale model closely approximating actual RFC structures. Wang et al.42 developed a three-dimensional four-phase finite element model of RFC incorporating porous SCC to investigate the impact of SCC porosity on the uniaxial compressive performance of RFC. Numerical simulation thus proves to be an effective tool for studying large-scale structures like RFC.

For these reasons, this study adopts a numerical approach to investigate RFC. A four-phase mesoscale finite element model was developed, incorporating large aggregates, SCC, ITZ, and Aggregate Contact Unit(ACU), and validated using experimental data from large-scale RFC specimens to confirm model accuracy and reliability. This model was then used to examine the effects of ITZ and aggregate mechanical properties on RFC’s uniaxial compressive performance, analyzing the macroscopic mechanical response to variations in individual components. Subsequently, a model with internal aggregate defects was created to study changes in RFC’s overall uniaxial performance at porosities of 0%, 1.75%, 3.70%, and 6.68%, with further exploration of underlying material behaviors. Overall, this research advances understanding of the mechanical response differences between RFC and conventional concrete and highlights RFC’s unique structural characteristics.

Test on uniaxial compressive properties of RFC

Test overview

In engineering applications, RFC typically utilizes aggregate sizes exceeding 300mm, making it challenging to replicate the uniaxial compressive performance of full-scale RFC using scaled-down tests. Therefore, a large RFC test chamber was cast, measuring 5000 × 4000 × 2000mm (Fig. 1 (a)). The test chamber comprised C15 self-compacting concrete and rock aggregate over 300mm in diameter, with a 55% rock fill ratio. After a 56-day curing period, twenty prismatic specimens (450 × 450 × 900mm) were cut from the chamber (Fig. 1 (b)) for uniaxial compression testing (Fig. 1 (c)) to obtain data on RFC’s uniaxial compressive strength, elastic modulus, and typical failure modes.

Test methods and results

The experiments of physical–mechanical properties were conducted at the Testing Center of the College of Civil Engineering, Guizhou University. All specimens were loaded using a 1000-ton electro-hydraulic servo press, with uniaxial compression deformation measured via external displacement frames equipped with displacement gauges. The resulting uniaxial compressive strength (ACS) and elastic modulus are presented in Fig. 2.

As shown in Fig. 2, the average elastic modulus of the prismatic specimens is 34.33GPa with a standard deviation of 3.32GPa, while the mean ACS is 23.34 MPa with a standard deviation of 3.8 MPa. The variability in the test results may be attributed to differences in the internal rock fill ratio across the cut specimens.

Figure 3 illustrates the typical failure modes of RFC prismatic specimens under uniaxial compression. The results indicate that RFC specimens exhibit an “X” pattern and diagonal shear failure mode, consistent with conventional concrete. However, close observation reveals that large aggregates alter the crack propagation path in RFC; as cracks reach the rock-filled aggregates, both transgranular and intergranular fractures may occur, which differs from conventional concrete behavior. Additionally, a distinct separation between the aggregates and SCC is often observed, with ITZ damage mainly concentrated around the aggregate sides (parallel to the loading direction). Overall, while the uniaxial compressive failure trend of RFC specimens resembles that of conventional concrete, differences in aggregate and ITZ damage are evident, likely due to the larger aggregate size.

3D mesoscale model and material parameters of RFC

The mesoscopic scale is the state between macroscopic and microscopic, and its scale is generally between micrometers and millimeters. It has been shown that the RFC mesoscale range is in the millimeter level2,22,23. This section introduces a 3D mesoscale model approach for RFC, incorporating nonlinear constitutive models of its constituent materials to simulate the uniaxial compressive performance of RFC. The mesoscale simulation was validated against experimental results, and parametric analyses were conducted to examine the effects of key factors on uniaxial compressive performance.

Aggregate and ITZ Model

Wang et al.43 proposed a 3D random polyhedral modeling method to accurately replicate the morphology of real aggregates. This study adopts this approach for aggregate modeling. Specifically, in a 3D spherical coordinate system, any point P in space can be defined by the radial distance r, azimuth angle θ, and polar angle φ. Based on this framework, setting r as the aggregate radius and sampling points every 45° along the θ and φ directions yields a spatial polyhedron consisting of 26 points (Fig. 4).Each vertex undergoes random fluctuation to capture the characteristic vertices of the 3D random aggregate. Assuming the initial parameters of point n are rn0, θn0, φn0, and the fluctuated parameters are rn, θn, φn, with D representing the control diameter of the aggregate, the fluctuation function of the aggregate vertices is given as follows:

In this equation, γr, γθ, γφ are random numbers generated between −1 and 1, indicating fluctuation directions; dr represents the fluctuation range of the aggregate radius r, where dr ∈ (-D/2,D/2); and dθ, dφ denote the fluctuation ranges along the θ and φ directions, respectively, with dθ, dφ ∈ (−22.5°,22.5°).

After completing the above steps, it is necessary to convert the resulting spherical coordinate parameters into Cartesian coordinates to facilitate modeling. The transformation formulas are as follows:

In this equation, xn, yn, zn represent the three-dimensional Cartesian coordinates of each characteristic point.

As an example of modeling a single irregular aggregate, after the random endpoints are generated, they are connected sequentially in order to form the irregular aggregate frame Fig. 5(a); after that, the irregular aggregate contour is formed by covering the surface on the basis of the frame Fig. 5 (b); finally, the solid is filled in the inside of the contour to form the final irregular aggregate model Fig. 5 (c).

Two primary approaches exist for ITZ modeling: inserting zero-thickness elements between aggregate and mortar units or using a solid ITZ with thickness40,42. Given the advantages of solid ITZ modeling at the mesoscale44, this study adopts a solid ITZ model. The procedure involves using each aggregate’s center as a reference point, extending the surface vertices outward along the radial direction by a fixed distance r´ to obtain the spherical coordinates of each expanded vertex \({P}_{n}^{`}({r}_{n}+{r}^{`},{\theta }_{n},{\varphi }_{n})\); these are then converted via Eqs. (1) and (2) to form the expanded surface. The region enclosed between the original and expanded surfaces represents the ITZ, with a thickness δ (Fig. 6). It is noteworthy that the ITZ thickness in conventional concrete is very small, typically around 0.5 μm, which poses challenges in numerical simulations. Most studies set the ITZ thickness between 0.2–2 mm to ensure computational accuracy while optimizing resource efficiency45,46. For RFC, the ITZ is relatively larger than the conventional concrete scale. Meanwhile, some scholars studying the mesoscopic modeling of RFC have also shown that the size of ITZ can be appropriately enlarged regarding RFC to balance the computational efficiency and accuracy42,47. In this paper, after several modeling tests, the thickness of ITZ was set to 10 mm for modeling.

RFC modeling

A primary characteristic of RFC is the formation of a rock skeleton structure, which also presents the main challenge in mesoscale modeling. Currently, this is typically achieved by applying gravity to the aggregates, using gravity simulation to establish the rock skeleton structure40,42 and subsequently developing a three-dimensional mesoscale model. Notably, the three-dimensional spatial reconstruction methodology proposed by Liang et al.41 provides an efficient approach to implement this process.

In this paper, based on the methodology proposed by the researcher, a large-size numerical model specimen of RFC with dimensions of 2000 × 2000 × 2000 mm was constructed at first. it should be noted that the model was designed to correspond to the control parameters related to the experimental chamber poured for the physical experiments.

The model uses aggregates with grain sizes in the range of 300—1000 mm and a rock filled rate of 55%. And the ITZ modeling of the model uses a dimension thickness of 10 mm. Implementation procedure of the three-dimensional spatial reconstruction methodology follows these essential steps:

-

(1)

Generate a point lattice within a gravity drop box measuring 2000 × 2000 × 10,000 mm48 to enable initial aggregate placement. To simplify the modeling process, a single-point lattice is used for this placement. Next, all aggregates are preliminarily placed within the box, ensuring no overlap to establish the initial parameter space for RFC (Fig. 7(a)).

-

(2)

Constrain all degrees of freedom of the gravity drop box to fix it in place, apply a gravitational load to each aggregate, and define the contact properties between aggregates and between aggregates and the box walls. After the gravity drop simulation completes, a loading plate is applied to the top of the aggregate layer to further compact the rock skeleton, ultimately achieving a rock fill ratio of 55% (Fig. 7(b)).

-

(3)

Using Python, extract the displacement and rotation data of each aggregate following compaction. This data is then used to reconstruct the initial parameter space of RFC, producing a parameter space aligned with the compacted structure (Fig. 7(c)). Subsequently, adjustments are made to the reconstructed RFC parameter space to include the ITZ.

-

(4)

After step (3), overlapping sections may exist between ITZ layers, which need to be removed to ensure non-interfering ITZ regions (Fig. 7(d)).

-

(5)

Finally, the Boolean cut operation is used to create the SCC phase that fills the voids between the rock aggregates (Fig. 7(e)), resulting in a three-dimensional mesoscale RFC model with boundary dimensions of 2000 × 2000 × 2000 mm (Fig. 7(f)).

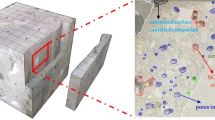

From the internal structure, most of the aggregates in conventional concrete exist in a suspended state, there is no excessive contact between the aggregates, and the mechanical behavior of the aggregates needs to be transferred through the mortar matrix, while for RFC, there is mutual contact between the aggregates, and the mechanical behavior can be transferred directly through the mortar matrix, which is fundamentally different from that of conventional concrete. In the case of RFC, the internal aggregates are in contact with each other, and the mechanical behavior can be directly transferred between the aggregates, which is fundamentally different from that of conventional concrete. The stress skeleton formed by the accumulation of aggregates inside RFC cannot be neglected in modeling41,42. In order to provide a better simulation of the mechanical behavior of the rock stack in RFC, it is necessary to establish the Aggregate Contact Unit (ACU).

It should be noted that, due to computational precision issues, models constructed using the three-dimensional spatial parameter reconstruction method may exhibit minor interpenetration at aggregate contact points after gravity stacking, indicating that strict aggregate contact is not fully achieved. To create a three-dimensional, four-phase model that includes aggregate contact zones, the mapped meshing method offers an effective solution, which will be discussed in detail in subsequent sections. Additionally, to align with experimental conditions, where cut specimens are used for compressive test, the model was segmented accordingly. Each segment measures 450 × 450 × 900 mm, yielding a total of 32 blocks (Fig. 8).

The mapped meshing approach was applied to the cut model specimens, enabling the creation of a model that includes the fourth phase—the aggregate contact zone. The procedure involves first constructing a prismatic model with the same dimensions as the cut specimens and dividing it into hexahedral mesh elements. Each element is then evaluated to determine whether it belongs to the aggregate, ITZ, or SCC region. For the aggregate contact zone, additional assessment is required: if an element is simultaneously located within two or more aggregates, it is classified as an ACU. Finally, each mesh element is assigned the material properties corresponding to its designated region. This approach results in a three-dimensional, four-phase model incorporating aggregates, ITZ, SCC, and ACU (Fig. 9).

It should be noted that only the cut specimens were meshed to establish the four-phase model, rather than the full-scale model, for two main reasons. First, meshing the full-scale model would produce an exceedingly large number of elements, significantly impeding the initial modeling process. Second, as the physical experiments were conducted on RFC cut specimens, a full-scale model analysis is not essential. Therefore, to balance efficiency and relevance, only the cut specimens were meshed to create the four-phase model incorporating the aggregate contact unit (ACU). Improve efficiency while being able to achieve the same results.

Material parameters

To determine the material parameters of the constituent phases in the model, we combined the results of preliminary tests and theoretical studies. The Concrete Damage Plasticity (CDP) model was established by Lubliner49, and has been developed into a more mature constitutive model after continuous optimization and improvement. The CDP model is able to simulate the deformation behavior of quasi-brittle materials (e.g., concrete) subjected to compressive and tensile actions very well38,50. The first thing that needs to be clarified is that SCC, ITZ and rock are all used in the CDP base model in this paper, and specific adjustments are made in each phase. Specifically, we obtained the mechanical property indexes of each phase of vegetal SCC and rock respectively according to the preliminary test, and then determined the parameters related to the ontological curve of SCC and rock in the model according to the current technical index GB50010-2010. The average value of the strength of the vein SCC measured in our previous tests was 17.5 MPa. So we used the intrinsic parameter of strength grade C15 specified in the specifications to determine the model of the SCC ontological curve in the final input model. About rocks, Huang et al.51 suggested that rocks, as quasi-brittle materials similar to concrete, can be modeled as analogous principal constitutive curves for rocks by referring to higher grades of concrete. About ITZ, some scholars derived from physical tests that the ratio of its mechanical properties to the mortar matrix is in the range of 0.4–1.013,14,15. And the model about ITZ is often finalized by a discount factor (the ratio of the mechanical properties between ITZ and SCC).

We finalized this discount factor to be 0.4 after extensive numerical tests and inverse analyses. For the ACU, Wang42 recommends using the Mohr–Coulomb (MC) model, noting that simulation results show minimal variation across different cohesion (c) values. Accordingly, the ACU is also modeled using the MC approach. Table. 1 summarizes the material parameters for each phase.

Model validation

Numerical simulation tests were conducted on the model’s cut specimens, mirroring the physical tests to validate model accuracy. Since the physical tests yielded results from 20 cut specimens, uniaxial compression simulations were performed on the corresponding 20 model specimens. Two support blocks were placed on the top and bottom surfaces of each specimen, with the bottom block fixed and the top block subjected to a downward vertical displacement load, while other degrees of freedom were constrained. The displacement was set to 3 mm. Additionally, factors such as mesh density, loading rate, and friction at the contact surfaces of the support blocks were evaluated to confirm the appropriateness of these parameters. Finally, the simulated results were compared with the physical test results to validate the model.

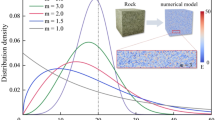

Multi-factor reasonableness analysis

The influence of mesh density on computational accuracy and simulation results is significant. In this study, uniaxial compression simulations were conducted on RFC cut specimens with mesh sizes of 5.0 mm,7.5 mm, 10 mm, 12.5mm and 15.0 mm, corresponding to mesh counts of 1,458,000, 432,000, 182,250, 93,312 and 54,000 elements, respectively. As shown in the stress–strain curves in Fig. 10. The results across different mesh sizes align closely in the elastic phase, with differences appearing in the elastoplastic hardening phase, where larger mesh sizes yield higher stress values. As mesh size decreases, the hardening phase and peak load stabilize, with results from the 7.5 mm and 10 mm meshes nearly identical.

Meanwhile Fig. 11 shows the compressive damage distribution cloud maps with different mesh sizes in order to better reflect the mesh dependence of the local damage behavior. From the results, it can be seen that the damage bands with mesh sizes less than 10.0 mm are more delicate, and on the contrary, the distribution of the damage bands larger than 10.0 mm is rougher. Considering that the difference between each result with a mesh smaller than 10.0 mm is very small, the accuracy can be guaranteed, but the calculation time is very different. In order to save the calculation time, this paper finally chooses the grid density of 10 mm to carry out the simulation calculation. Finally, considering the minimal difference in results and adequate accuracy, a 10 mm mesh size was selected for further simulations to optimize computational efficiency.

In the numerical simulation, it is important to ensure the loading process of the model specimen is quasi-static. The reason is faster loading rates can lead to a larger kinetic energy of the material due to excessive deformation, producing a dynamic effect that significantly affects the calculation results. It is widely recognized that the Kinetic energy of material deformation does not exceed 5–10% of the Internal energy42,44. In order to obtain favorable calculation results, it is necessary to select a suitable loading rate. Simulations were performed with loading rates of 300 mm/s, 100 mm/s, 50 mm/s, and 30 mm/s. Figure 12 presents the resulting stress–strain curves for each rate. The peak load decreases with lower loading rates, with curves at 50 mm/s and 30 mm/s nearly overlapping. Therefore, a loading rate of 50 mm/s, with a total loading time of 0.06 s, was selected for the simulations.

The frictional force at the contact surface between the support block and the specimen affects lateral deformation, inducing a three-dimensional stress state in the specimen and increasing compressive strength52. To determine an appropriate friction coefficient for this interface, simulations were conducted under varying friction conditions. As shown in Fig. 13 when the friction coefficient is below 0.5, noticeable differences appear in both the peak load and post-peak segments of the stress–strain curves. However, with a friction coefficient above 0.5, the stress–strain curves exhibit high consistency. Considering that the frictional force between concrete and support blocks in experiments is generally not excessively high, a friction coefficient of 0.5 was selected for subsequent simulations.

Comparative validation analysis

We carried out simulation tests on 20 model-cut specimens, which was done to keep the number of specimens consistent with the experiment tests and to minimize randomness errors. Figure 14(a) and Fig. 14(b) separately shows the simulated results for the elastic modulus and ACS of the 20 model specimens, with their mean values compared to the experimental averages. The average simulated elastic modulus is 35.01GPa with a standard deviation of 1.24GPa, while the average simulated ACS is 23.03 MPa with a standard deviation of 2.76 MPa. Comparing the simulated and experimental results, the relative error for the mean elastic modulus is 2%, and for the ACS, it is 1%, indicating high accuracy. Furthermore, the significant variation in rock fill ratio across cut specimens contributes to the considerable dispersion in the mesoscale simulation results for RFC’s uniaxial compressive performance40, consistent with experimental findings.

In the simulation, elements with a compressive damage factor greater than 0.9 are considered damaged, and the connected damaged elements represent the fracture pattern. The simulated compressive damage (Fig. 15) was compared with the experimental failure results (Fig. 3). The crack patterns in both demonstrate high similarity, showing"X"-shaped and shear-type fractures. Particularly, the model accurately captures transgranular fracture in the aggregates (Fig. 15(c) and Fig. 3(c)).

This comparative analysis indicates a high level of agreement between the simulated and experimental results, demonstrating that the model effectively replicates RFC’s uniaxial compressive mechanical behavior. This model will be used in subsequent sections to conduct numerical studies exploring the macroscopic response of RFC mechanical properties to variations in constituent phase properties.

Parametric simulation analysis

Using the numerical model, an analysis was conducted to investigate the macroscopic mechanical response of RFC uniaxial compressive performance to variations in ITZ and large aggregate properties. In concrete materials, the ITZ plays a critical role in load transfer; given the unique scale and structure of ITZ in RFC, it is essential to explore its load transfer mechanism and functional role within RFC. Generally, the mechanical properties of ITZ range from 0.4 to 1.0 times those of the mortar matrix13,14,15. This study examines the effects of different ITZ strengths (σITZ/σSCC = 0.4, 0.5, 0.6, 0.7, 0.8, 0.9) on RFC uniaxial compressive performance. It should be pointed out that, in order to eliminate the interference of other factors, we have standardized the ITZ elastic modulus values at different strengths.

Large aggregates are fundamental to RFC construction, as direct contact between them allows aggregate properties to contribute more significantly, distinguishing RFC from conventional concrete. The mechanical properties of natural rock aggregates are highly variable, often containing complex internal defects such as fissures and voids, which significantly impact mechanical performance33,34,35. Therefore, it is essential to examine the influence of aggregate mechanical properties and internal defects on RFC performance. In the first place, the effects of varying aggregate strength (σRock/σ0 = 0.8,0.9,1.0,1.1,1.2, where σ0 represents the initial parameters in Table. 1) on RFC macroscopic uniaxial compressive performance were analyzed. In order to exclude the influence of other factors on the results, we decoupled the nonlinear relationship between aggregate strength and elastic modulus to unify the elastic modulus at different aggregate strengths. Next, internal aggregate defects were simulated by introducing square-shaped defects within the aggregates to study their effects on RFC performance, with different porosity levels used to characterize defect severity. Porosity is defined as the ratio of defect volume to aggregate volume (Porosity = Porosity = VDefect/VAggregate), with simulated porosity conditions of 0%, 1.75%, 3.70%, and 6.68%. The specific simulation groups are outlined in Table 2

Results and discussion

Effect of ITZ

Figure 16(a) presents the stress–strain curves of RFC under varying ITZ properties. In the linear elastic phase (stress below 10 MPa), the curves overlap closely. However, upon entering the elastoplastic phase (10 MPa to peak load), notable distinctions emerge. Specimens with lower ITZ properties transition into the elastoplastic phase earlier, with instantaneous stress values lower than those of specimens with higher ITZ properties, the trend continues until peak load.

Figure 16(b) shows the trends in elastic modulus and uniaxial compressive strength of RFC under varying ITZ conditions. As ITZ strength increases, both E and ACS exhibit moderate improvements, with gains of 1.32GPa and 1.53MPa, respectively. On average, a 10% increase in ITZ strength results in a 0.177GPa increase in E and a 0.219 MPa increase in ACS, corresponding to growth rates of 0.52% and 1.13%. It should be noted that the respective increases in E and ACS values are 0.069% and 0.517% for the σITZ/σSCC > 0.7 and 0.844% and 1.375% for the σITZ/σSCC < 0.7 stage. σITZ/σSCC > 0.7 shows a smaller increase, and the performance enhancement is mainly seen in the σITZ/σSCC < 0.7 stage.

For conventional concrete, improvements in ITZ have minimal effect on the elastic modulus but significantly enhance compressive strength, with a 10% increase in ITZ properties resulting in a 4.87% increase in strength20. This marked improvement is less evident in RFC, likely due to structural differences between the aggregate-ITZ interface in RFC and that in conventional concrete.

Figure 17 presents a simplified schematic of the spatial arrangement of aggregates, ITZ, and SCC in RFC compared to conventional concrete. In conventional concrete (Fig. 17 (a)), aggregates are typically suspended within the mortar matrix, with minimal aggregate-to-aggregate contact. Load transfer between aggregates relies heavily on the ITZ, which serves as a critical"bridge."In conventional concrete, ITZ at the upper and lower parts of aggregates usually fails first, with cracks propagating around this ITZ region. In RFC (Fig. 17 (b)), however, direct contact between aggregates eliminates the ITZ in those regions, resulting in load transfer between aggregates without ITZ involvement. This reduces the ITZ’s bridging role, explaining why ITZ improvements have a limited effect on enhancing RFC performance. However, this does not imply that the ITZ is unimportant; rather, it plays a critical role in maintaining other performance aspects of RFC.

Under uniaxial compressive loading, the material deforms in compression along the direction of the force. However, in cross sections perpendicular to the loaded direction, the material will stretch laterally as there is no force constraint. For concrete, the aggregate is typically stressed under uniaxial loading and the mortar is more susceptible to tensile deformation, and this stress-deformation difference can lead to spalling damage between the mortar and the aggregate. The transitional interfacial zone (ITZ) between aggregate and mortar has more fragile tensile mechanical properties than mortar, and microcracking of concrete often occurs here. In order to compare the effects of compressive and tensile damage in the ITZ on the RFC, respectively, we need to compare the two types of damage.

DAMAGEC and DAMAGET represent the damage variables of a mesh element under compressive and tensile loading, respectively, with a value of 0.9 indicating complete damage of the element. Figure 18 presents the simulation results for DAMAGEC and DAMAGET in the ITZ phase. As shown, the levels of DAMAGEC and DAMAGET near aggregate contact points are relatively low, with DAMAGEC factors below 0.7 and DAMAGET factors approaching zero, further supporting the observed weakening effect of the ITZ in these regions. In stark contrast, the ITZ along the lateral sections exhibits nearly complete damage, with damage factors exceeding 0.9, which negatively impacts the bonding between aggregates and SCC.

Maintaining strong interfacial bonding between constituent phases is crucial for the functionality of composite materials. In RFC, the ITZ serves as the connecting interface between aggregates and SCC. The results indicate that the weaker ITZ along the aggregate sides undergoes significant damage, leading to separation between the aggregates and SCC. This compromises the structural integrity of RFC, adversely affecting other properties such as impermeability, crack resistance, and stability.

Figure 19 illustrates the evolution of ITZ DAMAGET under three different conditions as strain increases. The results indicate that in the low-to-moderate strain phase (ε < 0.967 × 10–3), the area of DAMAGET in the ITZ is significantly reduced with higher ITZ performance, suggesting that DAMAGET initiation is delayed, thereby enhancing the integrity of RFC for a longer period, which is beneficial for its mechanical performance. At higher strains (ε = 0.967 × 10–3), ITZ damage is similar across conditions, as the RFC is fully compromised and the ITZ has failed.

Although the load-transfer role of the ITZ in RFC differs from that in conventional concrete, it remains crucial for maintaining the overall integrity of RFC. Ensuring sufficient ITZ strength is essential in engineering applications to preserve the structural coherence of RFC.

Aggregate strength

Figure 20(a) shows the stress–strain curves of RFC under varying aggregate properties. Results indicate that peak stress increases with improved aggregate strength, while the instantaneous strain in the elastoplastic phase decreases, leading to enhanced brittleness and reduced deformation capacity. Additionally, Fig. 20(b) demonstrates that both the elastic modulus and uniaxial compressive strength of RFC improve with higher aggregate performance. On average, a 10% increase in aggregate results in approximately a 0.5GPa increase in elastic modulus and a 0.483 MPa increase in uniaxial compressive strength, representing growth rates of 1.52% and 2.58%, respectively—substantially greater than the improvements achieved through ITZ enhancement.

In conventional concrete, improving aggregate properties within a certain range can significantly enhance compressive strength; however, beyond a threshold, the rate of improvement plateaus, offering limited gains18,20, indicating that aggregate potential is not fully utilized. In RFC, however, the direct interaction between aggregates significantly enhances their effectiveness, as shown in Fig. 20(b), where both properties exhibit a linear positive correlation with aggregate strength.

To further investigate the effect of enhanced aggregate properties on RFC, Fig. 21 presents the final compressive damage results for aggregates under various conditions and the evolution of SCC compressive damage before peak stress. The overall damage to aggregates shows minimal variation across conditions, with only minor differences; the primary distinctions lie in the damage to SCC. The figure reveals that lower-strength aggregates result in more pronounced cracking in SCC compared to higher-strength aggregates. Notably, the marked crack in the figure initiates and propagates at a lower strain (ε = 0.133 × 10–2) under low aggregate strength, while this crack diminishes with increasing aggregate strength. It does not reappear until peak strain, at which point aggregate damage leads to RFC failure.

Internal defects in the aggregate

Natural rocks inevitably have internal porosity. It has been shown that different shapes and porosities affect the mechanical properties of rocks33,34,35.RFC is strongly dependent on aggregates, and it is worthwhile to further investigate whether the internal porosity of aggregates affects the overall performance of RFC by affecting the performance of aggregates themselves. To investigate the effect of internal aggregate defects on the uniaxial compressive performance of RFC, this section proposes a method for generating porosity within aggregates based on a defect-free RFC model, resulting in a numerical model of RFC with internal aggregate defects. In the full-scale model, a square-shaped void is introduced at the center of each aggregate to simulate internal defects. During mesh generation, elements within the defect region are removed to achieve the defect simulation. As with previous models, meshing was applied only to the cut specimens (Fig. 22). Here, porosity is defined as the ratio of defect volume to aggregate volume (Porosity = VDefect/VAggregate).

Figure 23(a) presents the compressive stress–strain curves of RFC under varying porosity levels. As shown, with increasing porosity, the length of the linear elastic phase decreases from 0–12 MPa at 0% porosity to 0–7.5 MPa at 6.68% porosity, indicating that higher porosity shortens the elastic phase and accelerates entry into the elastoplastic stage, resulting in earlier plastic deformation. Peak load also decreases significantly with increasing porosity. Additionally, Fig. 23(b) reveals that the overall reductions in RFC’s elastic modulus (E) and uniaxial compressive strength (ACS) are 0.58 GPa and 0.78 MPa, respectively, with reduction rates of 1.72% and 3.93%. Comparing the reduction rates of EEE and ACS suggests that porosity has a relatively minor effect on the elastic modulus but has a more pronounced negative impact on the ultimate uniaxial compressive strength of RFC.

To further understand the internal factors affecting the uniaxial compressive performance of RFC due to aggregate porosity, Fig. 24 compares the evolution of DAMAGEC distributions in RFC models with varying porosity levels. The presence of defects alters the original crack propagation path, causing cracks to extend more closely around the defects. Damage within the aggregates becomes more pronounced, with a noticeable increase in damaged areas. Cracks that initially bypassed aggregates more readily penetrate the interior, concentrating damage around or directly through the defects. This behavior suggests that the presence of defects concentrates internal stress, making aggregates more susceptible to localized failure, thereby weakening aggregate strength and reducing the overall uniaxial compressive strength of RFC.

Conclusions

In this study, a 3D mesoscale RFC model incorporating large aggregates, SCC, ITZ, and ACU was developed and validated through experimental comparison. A method for generating internal porosity within aggregates was also introduced. Using this validated model, a numerical analysis was conducted to evaluate the effects of ITZ property, aggregate property, and internal aggregate defects on the uniaxial compressive performance of RFC, aiming to understand RFC macroscopic response to its constituent phases. The main conclusions are as follows:

-

(1)

The 10% change in ITZ mechanical properties results in a 0.52% and 1.13% increase in RFC’s elastic modulus and uniaxial compressive strength, respectively, which is significantly lower than the 4.87% observed in conventional concrete. This is attributed to the reduced role of ITZ in RFC, where it does not directly contribute to load transfer as it does in conventional concrete.

-

(2)

Changes in the mechanical properties of the aggregate have a direct impact on RFC’s overall uniaxial compressive performance. The 10% change in aggregate mechanical properties results in a 1.52% and 2.58% change in RFC’s elastic modulus and uniaxial compressive strength, respectively, with a clear linear positive correlation.

-

(3)

The ratios of the degree of influence of aggregate and ITZ on the axial compressive properties of RFC are 2.92 and 2.28, respectively, indicating a strong dependency of RFC on aggregates. This is due to the direct contact between aggregates in RFC, which facilitates load transfer between aggregates and fully utilizes their mechanical properties, unlike the nearly non-contact nature of aggregates in conventional concrete.

-

(4)

As aggregate porosity increases, RFC’s uniaxial compressive strength decreases, with reductions of 1.72% in elastic modulus and 3.93% in uniaxial compressive strength. This is primarily due to internal defects in the aggregate, which cause stress concentration, leading to earlier and more extensive damage within the aggregate, weakening its strength and subsequently reducing RFC’s overall uniaxial compressive performance.

The unique internal structure of RFC results in a different role for aggregates and ITZ compared to conventional concrete. While enhancing ITZ properties does not directly impact RFC’s uniaxial compressive performance, it contributes positively to maintaining structural integrity. Given RFC’s high dependency on aggregate performance, factors influencing aggregate mechanical properties are likely to affect RFC as well.

Data availability

The authors declare that the datasets used and analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

An, X. et al. Rock-filled concrete, the new norm of SCC in hydraulic engineering in China. Cement Concr. Compos. 54, 89–99. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cemconcomp.2014.08.001 (2014).

Xie, Y., Corr, D. J., Chaouche, M., Jin, F. & Shah, S. P. Experimental study of filling capacity of self-compacting concrete and its influence on the properties of rock-filled concrete. Cem. Concr. Res. 56, 121–128. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cemconres.2013.11.010 (2014).

Jin, F., Huang, D., Lino, M. & Zhou, H. A Brief Review of Rock-Filled Concrete Dams and Prospects for Next-Generation Concrete Dam Construction Technology. Engineering 32, 99–105. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eng.2023.09.020 (2024).

Chen, X., Yuan, J., Dong, Q. & Zhao, X. Meso-scale cracking behavior of Cement Treated Base material. Constr. Build. Mater. 239, 117823. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2019.117823 (2020).

Kim, S.-M. & Abu Al-Rub, R. K. Meso-scale computational modeling of the plastic-damage response of cementitious composites. Cem. Concr. Res. 41, 339–358. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cemconres.2010.12.002 (2011).

Prokopski, G. & Halbiniak, J. Interfacial transition zone in cementitious materials. Cem. Concr. Res. 30, 579–583. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0008-8846(00)00210-6 (2000).

Kishore, K. & Tomar, R. Understanding the role of interfacial transition zone in cement paste and concrete. Mater. Today: Proc. 80, 877–881. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matpr.2022.11.322 (2023).

Simeonov, P. & Ahmad, S. Effect of transition zone on the elastic behavior of cement-based composites. Cem. Concr. Res. 25, 165–176. https://doi.org/10.1016/0008-8846(94)00124-H (1995).

Asbridge, A. H., Page, C. L. & Page, M. M. Effects of metakaolin, water/binder ratio and interfacial transition zones on the microhardness of cement mortars. Cem. Concr. Res. 32, 1365–1369. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0008-8846(02)00798-6 (2002).

Li, Y. et al. Multi-scale creep analysis of river sand and manufactured sand concrete considering the influence of ITZ. Constr. Build. Mater. 344, 128175. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2022.128175 (2022).

Ren, Q., Pacheco, J. & de Brito, J. Methods for the modelling of concrete mesostructures: A critical review. Constr. Build. Mater. 408, 133570. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2023.133570 (2023).

Chen, Q., Zhang, J., Wang, Z., Zhao, T. & Wang, Z. A review of the interfacial transition zones in concrete: Identification, physical characteristics, and mechanical properties. Eng. Fract. Mech. 300, 109979. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engfracmech.2024.109979 (2024).

Yang, C. C. Effect of the Transition Zone on the Elastic Moduli of Mortar. Cem. Concr. Res. 28, 727–736. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0008-8846(98)00035-0 (1998).

Xiao, J., Li, W., Corr, D. J. & Shah, S. P. Effects of interfacial transition zones on the stress–strain behavior of modeled recycled aggregate concrete. Cem. Concr. Res. 52, 82–99. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cemconres.2013.05.004 (2013).

Xiao, J., Li, W., Sun, Z., Lange, D. A. & Shah, S. P. Properties of interfacial transition zones in recycled aggregate concrete tested by nanoindentation. Cement Concr. Compos. 37, 276–292. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cemconcomp.2013.01.006 (2013).

Zhang, Y. et al. Experimental study on the fracture behavior of a novel multi-scale fiber reinforced ultra-high performance concrete with hollow microspheres after high temperatures. Eng. Fract. Mech. 318, 110979. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engfracmech.2025.110979 (2025).

Zhang, Y. et al. Insights into the fracture behavior of multi-scale fiber reinforced ultra-high performance cementitious composites after exposure to high temperatures. Theoret. Appl. Fract. Mech. 138, 104896. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tafmec.2025.104896 (2025).

Ren, X. et al. 3D mesoscale study on the effect of ITZ and aggregate properties on the fracture behaviors of concrete based on discrete element method. J. Build. Eng. 83, 108450. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jobe.2024.108450 (2024).

Zhang, S., Zhang, C., Liao, L. & Wang, C. Numerical study of the effect of ITZ on the failure behaviour of concrete by using particle element modelling. Constr. Build. Mater. 170, 776–789. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2018.03.040 (2018).

Zhao, H., Wu, Z., Liu, A. & Zhang, L. Numerical insights into the effect of ITZ and aggregate strength on concrete properties. Theoret. Appl. Fract. Mech. 120, 103415. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tafmec.2022.103415 (2022).

Zhou, X. et al. DEM analysis of the effect of interface transition zone on dynamic splitting tensile behavior of high-strength concrete based on multi-phase model. Cem. Concr. Res. 149, 106577. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cemconres.2021.106577 (2021).

Xie, Y., Corr, D. J., Jin, F., Zhou, H. & Shah, S. P. Experimental study of the interfacial transition zone (ITZ) of model rock-filled concrete (RFC). Cement Concr. Compos. 55, 223–231. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cemconcomp.2014.09.002 (2015).

He, J. et al. Experimental investigation into mode-I interfacial fracture behavior between rock and self-compacting concrete in rock-filled concrete. Eng. Fract. Mech. 258, 108047. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engfracmech.2021.108047 (2021).

Akcay, B. et al. Interpretation of aggregate volume fraction effects on fracture behavior of concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 28, 437–443. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2011.08.080 (2012).

Meddah, M. S., Zitouni, S. & Belâabes, S. Effect of content and particle size distribution of coarse aggregate on the compressive strength of concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 24, 505–512. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2009.10.009 (2010).

Nikbin, I. M. et al. Effect of coarse aggregate volume on fracture behavior of self compacting concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 52, 137–145. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2013.11.041 (2014).

Beushausen, H. & Dittmer, T. The influence of aggregate type on the strength and elastic modulus of high strength concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 74, 132–139. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2014.08.055 (2015).

Kılıç, A. et al. The influence of aggregate type on the strength and abrasion resistance of high strength concrete. Cement Concr. Compos. 30, 290–296. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cemconcomp.2007.05.011 (2008).

Gautam, B. P., Panesar, D. K., Sheikh, S. A. & Vecchio, F. J. Effect of coarse aggregate grading on the ASR expansion and damage of concrete. Cem. Concr. Res. 95, 75–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cemconres.2017.02.022 (2017).

Piotrowska, E., Malecot, Y. & Ke, Y. Experimental investigation of the effect of coarse aggregate shape and composition on concrete triaxial behavior. Mech. Mater. 79, 45–57. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mechmat.2014.08.002 (2014).

Rocco, C. G. & Elices, M. Effect of aggregate shape on the mechanical properties of a simple concrete. Eng. Fract. Mech. 76, 286–298. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engfracmech.2008.10.010 (2009).

Yu, Q., Liu, H., Yang, T. & Liu, H. 3D numerical study on fracture process of concrete with different ITZ properties using X-ray computerized tomography. Int. J. Solids Struct. 147, 204–222. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijsolstr.2018.05.026 (2018).

Ma, W., Cui, C. & Li, X. Mechanical responses and stress distribution of rock-like specimen containing a spherical defect under uniaxial compression. Theoret. Appl. Fract. Mech. 130, 104251. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tafmec.2023.104251 (2024).

Ji, P. X., Viegas, G. & Zhang, Q. B. Mechanical and fracturing characteristics of defected rock-like materials under biaxial compression. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 176, 105692. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrmms.2024.105692 (2024).

Cai, X. et al. Effects of hole shape on mechanical behavior and fracturing mechanism of rock: Implications for instability of underground openings. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 141, 105361. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tust.2023.105361 (2023).

Yılmaz, O. & Molinari, J. F. A mesoscale fracture model for concrete. Cem. Concr. Res. 97, 84–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cemconres.2017.03.014 (2017).

Xu, Y. & Chen, S. A method for modeling the damage behavior of concrete with a three-phase mesostructure. Constr. Build. Mater. 102, 26–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2015.10.151 (2016).

Maleki, M., Rasoolan, I., Khajehdezfuly, A. & Jivkov, A. P. On the effect of ITZ thickness in meso-scale models of concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 258, 119639. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2020.119639 (2020).

Fang, Q., Yan, P., Zhang, J. H., Zhao, P. S. & Chen, Z. Methodology to Develop 3D Mechanical Model of the Rock-filled Cocnrete. J. Build. Mater 20, 55–60. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1007-9629.2017.01.010.[inChinese] (2017).

Liang, T., Jin, F., Huang, D. & Wang, G. On the elastic modulus of rock-filled concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 340, 127819. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2022.127819 (2022).

Liang, Y., Zou, S. & Xie, C. A method to rapidly build complex three-dimensional models of rock-filled concrete. Comput. Struct. 281, 107020. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compstruc.2023.107020 (2023).

Wang, Y., Liang, T. & Jin, F. Void effect study on the compressive behavior of RFC based on the 3D four-phase mesoscopic finite element model. Constr. Build. Mater. 417, 135145. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2024.135145 (2024).

Wang, B., Wang, H., Zhang, Z. & Zhou, M. A study on three-dimensional stochastic concave-convex concrete aggregate fine view modeling approach. Chin. J. Appl. Mech. 35, 1072–1076. https://doi.org/10.11776/cjam.35.05.B062 (2018).

Zhou, G. & Xu, Z. 3D mesoscale investigation on the compressive fracture of concrete with different aggregate shapes and interface transition zones. Constr. Build. Mater. 393, 132111. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2023.132111 (2023).

Huang, Y. J., Yang, Z. J., Chen, X. W. & Liu, G. H. Monte Carlo simulations of meso-scale dynamic compressive behavior of concrete based on X-ray computed tomography images. Int. J. Impact Eng. 97, 102–115. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijimpeng.2016.06.009 (2016).

Zhou, X. Q. & Hao, H. Mesoscale modelling of concrete tensile failure mechanism at high strain rates. Comput. Struct. 86, 2013–2026. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compstruc.2008.04.013 (2008).

Yu, L. et al. Study on compressive size effect of rock-filled concrete considering initial pores. Structures 71, 108030. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.istruc.2024.108030 (2025).

Xu, L., Jiang, L., Zhou, C. & Ren, Q. Efficient Generation of 3D Fine Structure of Fully Graded Concrete Based on Multi-focused Cloud with Hierarchical Aggregation. J. Hydraul. Eng. 53, 188–199. https://doi.org/10.13243/j.cnki.slxb.20210708 (2022).

Lubliner, J., Oliver, J., Oller, S. & Oñate, E. A plastic-damage model for concrete. Int. J. Solids Struct. 25, 299–326. https://doi.org/10.1016/0020-7683(89)90050-4 (1989).

Jin, L., Yu, W., Du, X. & Yang, W. Mesoscopic numerical simulation of dynamic size effect on the splitting-tensile strength of concrete. Eng. Fract. Mech. 209, 317–332. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engfracmech.2019.01.035 (2019).

Huang H., Study on the fracture properties of type I fracture of stacked concrete rock block-SCC interface, master’s thesis (M.A.), Tsinghua University, https://doi.org/10.27266/d.cnki.gqhau.2019.000398. (2021).

Zheng, Z., Zeng, C., Tian, C. & Wei, X. Mesoscale numerical investigation on the size effect of concrete uniaxial compressive strength under different contact friction. Constr. Build. Mater. 346, 128416. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2022.128416 (2022).

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the support from the projects funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (52168056), Guizhou Province Science and Technology Support Plan Project ([2024] general 134, [2024]general123).

Funding

National Natural Science Foundation of China, 52168056, Guizhou Province Science and Technology Support Plan Project, [2024] general 134, [2024] general123.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Peng Chen: Investigation, Software, Formal analysis, Data curation, Writing – original draft. Youbin Li: Conceptualization, Resources, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. Xiaoling Tang: Conceptualization, Resources, Methodology, Project administration, Writing – review & editing, Supervision,. Ning Liu: Methodology, Resources, Funding acquisition.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, P., Li, Y., Tang, X. et al. 3D mesoscopic numerical investigation on the uniaxial compressive behavior of rock-filled concrete with different ITZ and aggregate properties. Sci Rep 15, 28588 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-13668-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-13668-y