Abstract

The college environment significantly shapes students’ social development, yet many experience social anxiety that affects their mental health. Trait resilience has been identified as an important psychological resource that may influence how individuals regulate emotions and cope with stress, which could be relevant to understanding social anxiety. Focusing on college students, this study examines the extent to which trait resilience, emotion regulation, and coping strategies contribute to the mitigation of social anxiety, emphasizing their potential roles as mediators in this psychological process. This study surveyed 748 college students using questionnaires to assess their trait resilience, social anxiety, emotion regulation, and coping strategies. The data were obtained via an online questionnaire, employing random sampling of university students from different regions in China during the period from November 2024 to January 2025. The dataset was processed through SPSS, which was applied to carry out statistical descriptions, examine variable correlations, and explore mediating effects. The study found a significant negative correlation between trait resilience and social anxiety (r = − 0.486, p < 0.001). In the mediation analysis, the direct effect of trait resilience on social anxiety remained significant (β = − 0.173, 95% CI − 0.224, − 0.121). Additionally, cognitive reappraisal (β = 0.047, 95% CI 0.001,0.096), expressive suppression (β = − 0.019, 95% CI − 0.037, − 0.002), approach coping strategies (β = − 0.145, 95% CI − 0.185, − 0.107), and avoidance coping strategies (β = − 0.025, 95% CI − 0.045, − 0.006) all played mediating roles between trait resilience and social anxiety. This study shows that higher trait resilience has been linked to lower social anxiety, with emotion regulation and coping strategies playing key mediating roles. These findings provide a basis for designing interventions to reduce social anxiety in college students. Future research should focus on enhancing trait resilience and promoting positive emotion regulation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Modern college life places growing demands on students, exposing them to escalating scholastic workloads and intensified social expectations. In China, the competitive nature of the education system, which emphasizes academic excellence from elementary school through university, has imposed long-term pressure on students1. Prolonged exposure to academic stress not only impairs students’ ability to perform academically but also restricts the cultivation of fundamental interpersonal skills. Upon entering college, students must adapt to complex interpersonal relationships and diverse social contexts, which often leads to heightened experiences of social anxiety2. Defined as a form of emotional strain, social anxiety arises when individuals engage in social interactions while worrying about unfavorable assessments from those around them3, and it can hinder both academic success and psychological well-being4.

Lately, researchers have focused more on inner psychological strengths that might serve as protective factors against the detrimental consequences of social anxiety. Drawing upon the Conservation of Resources (COR) theory5, trait resilience may help individuals preserve emotional balance and reduce stress when faced with social threats, thereby alleviating symptoms of social anxiety.

Moreover, researchers have emphasized the roles of emotion regulation and coping strategies in shaping students’ mental responses to stress and social anxiety6,7,8,9. Adaptive emotion regulation strategies, such as cognitive reappraisal, and approach coping strategies like seeking help and problem-solving, have been found to reduce anxiety levels10,11. Notably, research has indicated that the boundaries between emotion regulation and coping strategies may overlap to some extent, given that they often operate in tandem during real-life stress coping processes and share similar underlying mechanisms12. Thus, integrating these two regulatory mechanisms within a single analytical framework may enhance our understanding of how they function in the emergence of social anxiety among university students.

Although research interest in these underlying psychological factors has grown, how trait resilience interacts with emotion regulation and coping strategies to shape social anxiety has yet to be thoroughly investigated, particularly among college populations in China. In line with this aim, the current research seeks to uncover how trait resilience shapes social anxiety by examining the intermediary roles played by cognitive reappraisal and expressive suppression as emotion regulation approaches, along with approach and avoidance coping strategies.

Theoretical framework

The Process Model of Emotion Regulation (PMER), proposed by Gross13, systematically explains the mechanisms and stages involved in emotion regulation. The model emphasizes that different strategies vary in their adaptability and psychological outcomes. As a strategy employed before emotions are fully formed, cognitive reappraisal works by reframing the meaning of a given event, thereby adjusting the resulting emotional experience. It is generally regarded as more adaptive and beneficial to mental health. Unlike cognitive reappraisal, expressive suppression regulates emotions by restraining visible emotional reactions. When employed persistently, this strategy has been closely tied to heightened emotional strain and elevated anxiety symptoms14,15. From this theoretical perspective, trait resilience can be viewed as a foundational psychological resource for emotion regulation. Research evidence has demonstrated a strong connection between trait resilience and the application of different emotion regulation strategies16,17, which may serve as mediators with different directions and magnitudes in the relationship between trait resilience and social anxiety6,7,10.

According to Lazarus18 Transactional Model of Stress and Coping (TMSC), managing stress is not a one-time event but a fluid and reciprocal process shaped by the interplay between the person and their environmental context. Within the framework of this model, encountering stress prompts individuals to first assess the potential threat of the situation (primary appraisal), and then to consider whether they have the necessary means to handle it effectively (secondary appraisal). These cognitive assessments guide individuals in choosing coping strategies they consider effective in managing the stressor. Coping strategies are generally categorized into approach coping strategies and avoidance coping strategies. The former involves actively addressing the stressor, while the latter is characterized by avoiding or ignoring the problem. TMSC posits that psychological adaptation depends not only on the nature of the stressor but, more importantly, on the coping strategies employed19. Within this theoretical framework, trait resilience can be conceptualized as a crucial internal resource influencing secondary appraisal, namely, an individual’s perceived capacity to manage potential social threats with psychological strength and adaptability. In social contexts typical of university life, such as evaluative situations or unfamiliar interactions, students with greater trait resilience are more inclined to use approach coping strategies, which may in turn help reduce levels of social anxiety.

To sum up, both the PMER and TMSC highlight the importance of internal resources like trait resilience, along with regulatory strategies, in shaping individuals’ psychological responses to emotional and social stressors. TMSC highlights the functional distinctions between coping strategies, suggesting that approach and avoidance strategies yield different psychological outcomes. In contrast, PMER differentiates between the adaptive value of cognitive reappraisal and expressive suppression. The integration of these two models provides a multi-path theoretical foundation for the present study, illustrating how trait resilience may indirectly influence university students’ social anxiety through four distinct regulatory strategies. This integrated perspective advances our understanding of the psychological protective mechanisms underlying social anxiety.

Trait resilience and social anxiety

Trait resilience describes a person’s capacity to adjust effectively and flexibly when faced with challenges and difficulties20.Resilience theory suggests that resilience is not merely the ability to recover from difficulties, but is also an active psychological process that involves how individuals leverage both personal strengths and external support to navigate obstacles and grow in the process21. Within this framework, social anxiety can be viewed as a psychological challenge that individuals may face. Studies have demonstrated that greater trait resilience contributes positively to reducing social anxiety22,23,24,25,26. Li et al.22 provided evidence for the protective role of trait resilience in addressing social anxiety in university populations, noting that individuals high in trait resilience are more capable of adjusting to complex social contexts and managing emotions efficiently, which contributes to the reduction of social anxiety -related symptoms. Li et al.26 emphasized that highly resilient individuals are particularly outstanding in self-regulation; when confronted with stressful situations, they are able to efficiently utilize surrounding resources, which helps alleviate social anxiety when dealing with interpersonal challenges. Shuai et al.25 investigated how social exclusion influences social anxiety and found that trait resilience serves as a protective factor in this relationship. Their findings suggest that when facing social exclusion or other situations that may trigger social anxiety, people with high trait resilience are more inclined to adopt constructive ways of thinking about the problem rather than becoming trapped in a cycle of negative self-evaluation24. This cognitive reframing helps reduce fear and anxiety in social situations. In summary, trait resilience, as a crucial psychological resource, not only fosters growth and development when individuals face challenges but also helps them effectively cope with social anxiety.

Trait resilience and emotion regulation

Emotion regulation encompasses the methods individuals employ to regulate their emotions and expressions, allowing them to navigate different contexts or fulfill particular goals13. This process includes both external and internal systems that detect, analyze, and adjust emotional reactions27. According to the PMER, cognitive reappraisal and expressive suppression play distinct roles in managing emotions and their expressions. As a constructive form of emotion regulation, cognitive reappraisal entails shifting one’s perspective on a given event or context in order to change the emotional impact it produces. Conversely, expressive suppression represents a maladaptive approach to emotion regulation, involving the deliberate control or masking of visible emotional responses14,15.

Furthermore, empirical evidence points to a nuanced and strong association between an individual’s level of trait resilience and their emotion regulation processes16,28,29,30. Jiang et al.30 conducted a study on Chinese psychological helpline counselors, revealing that those with greater trait resilience tend to adopt cognitive reappraisal methods more frequently. This strategy allows them to effectively adjust and manage their emotional responses when faced with setbacks or stressful situations, enabling them to bounce back faster from negative feelings and utilize more adaptive coping strategies to maintain emotional balance and stability. On the other hand, individuals who exhibit reduced trait resilience tend to adopt expressive suppression more frequently as their preferred emotion regulation strategy. According to Alismail and Almulla28, individuals with diminished trait resilience show a greater tendency to frequently adopt expressive suppression as their primary means of regulating emotions. While this strategy may temporarily alleviate awkwardness or conflict in certain social situations, over time, suppressing emotional expressions can lead to greater psychological burden and physiological stress responses, weakening the individual’s connection with society and potentially triggering or exacerbating social anxiety6.

Emotion regulation and social anxiety

Previous studies have demonstrated a strong link between emotion regulation and social anxiety6,7,10,31. McBride et al.6 emphasized that cognitive reappraisal can evoke positive emotions, balance the impact of negative emotions, and encourage individuals to view problems from different perspectives, seeking positive meaning or possibilities, which may alleviate symptoms of social anxiety. Additionally, social anxiety is often accompanied by negative self-talk and excessive self-criticism32. Through cognitive reappraisal, individuals are able to detect and dispute maladaptive thought patterns, substituting them with healthier and more optimistic perspectives. This process contributes to better emotional regulation and may help diminish the intensity of social anxiety symptoms10. In contrast, expressive suppression attempts to deliberately conceal or inhibit emotional experiences, which does not effectively alleviate negative emotions. Instead, it may lead to emotional buildup and exacerbation, intensifying negative self-awareness33,34. Kivity et al.7 noted that in social contexts, efforts to inhibit emotional expressions may occur when individuals try to control their outward emotional responses, they may become more self-conscious, concerned about how others perceive them. This excessive self-monitoring can trigger or worsen social anxiety symptoms. Moreover, prolonged use of expressive suppression may result in a lack of emotional expression, which weakens interpersonal connections and heightens feelings of loneliness, intensifying the manifestations of social anxiety even more6.

To summarize, college students with higher trait resilience are likely to alleviate the onset and development of social anxiety through more effective cognitive reappraisal strategies, while those with lower trait resilience may become trapped in social anxiety due to the use of expressive suppression strategies. Understanding the role of emotion regulation as a psychological mechanism connecting trait resilience and social anxiety is essential for gaining insights into, and ultimately alleviating, social anxiety in the university student population.

Trait resilience and coping strategies

Coping strategies is a cognitive approach that reflects how individuals habitually manage various sources of stress35. According to coping theory, coping strategies can be divided into approach coping strategies and avoidance coping strategies. Approach coping strategies involve individuals adopting an optimistic attitude and using effective methods to solve problems and alleviate stress, thereby promoting psychological well-being. Avoidance coping strategies, on the other hand, involve individuals attempting to avoid or resist negative emotions associated with stressful events36.

Furthermore, the tendency to use different coping strategies is closely related to the level of trait resilience37,38,39,40,41. According to Yu et al.38, people with elevated trait resilience, underpinned by positive expectations and firm self-assurance, typically perceive stressors as solvable challenges and trust in their ability to manage setbacks effectively. This predisposes them to actively employ approach coping strategies as a means of managing stress. They are better at managing their emotions, staying calm under pressure, rationally analyzing problems, and seeking solutions, such as proactively gathering information, planning, or seeking external support37,42. Moreover, resilient individuals know how to utilize external resources and social support systems and are more adept at seeking help and support, which enhances their coping capacity26 and makes them more likely to engage in effective approach coping measures. In contrast, Ma et al.41 found that Chinese adolescents with lower trait resilience are more prone to encountering negative feelings like anxiety, depression, and stress when faced with difficulties, and tend to rely on avoidance coping strategies like avoidance, denial, or self-blame. People with lower trait resilience tend to have more frequent negative thought patterns, holding a pessimistic view of the future, lacking self-confidence, and believing that any effort is futile. This mindset leads them to choose avoidance coping strategies when encountering challenges39.

Coping strategies and social anxiety

Empirical findings suggest that the use of distinct coping strategies is linked to the experience and severity of social anxiety8,9,11. Yang et al.11 found that approach coping strategies serve as protective factors for social anxiety, while frequent use of avoidance coping strategies predicts higher levels of social anxiety. Approach coping strategies typically include problem-solving, seeking help, and cognitive restructuring43. These strategies help individuals better adapt to social environments by enhancing self-efficacy, improving negative thought patterns, and providing necessary social support44,45, thus effectively reducing social anxiety and promoting personal growth and development8. In contrast, avoidance coping strategies, which are less mature, include self-blame, avoidance, and fantasizing43. Shukla and Chouhan46 noted that although avoidance coping strategies might provide short-term relief from discomfort, its prolonged use can hinder the cultivation of social competencies, elevate feelings of loneliness and isolation, and ultimately intensify social anxiety9,11. Thus, coping strategies may mediate the effect of trait resilience on social anxiety, and fostering approach coping could be a practical focus for interventions targeting students’ well-being.

Research hypotheses

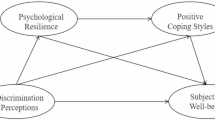

This research explores how emotion regulation and coping strategies function as mediators in the association between trait resilience and social anxiety. Grounded in both the TMSC and PMER frameworks, a theoretical model is constructed and presented in Fig. 1, and propose the following hypotheses:

H1

Trait resilience is negatively correlated with social anxiety.

H2

Trait resilience is significantly positively associated with the use of cognitive reappraisal strategies.

H3

Trait resilience is significantly negatively associated with the use of expressive suppression strategies.

H4

Trait resilience is significantly positively associated with approach coping strategies.

H5

Trait resilience is significantly positively associated with avoidance coping strategies.

H6

Cognitive reappraisal is significantly negatively associated with the level of social anxiety.

H7

Expressive suppression is significantly positively associated with the level of social anxiety.

H8

Approach coping strategies are significantly negatively associated with the level of social anxiety.

H9

Avoidance coping strategies are significantly positively associated with the level of social anxiety.

H10

Cognitive reappraisal mediates the relationship between trait resilience and social anxiety.

H11

Expressive suppression mediates the relationship between trait resilience and social anxiety.

H12

Approach coping strategies mediates the relationship between trait resilience and social anxiety.

H13

Avoidance coping strategiesmediates the relationship between trait resilience and social anxiety.

Research methods

Sample and data collection procedure

Between November 2024 and January 2025, data collection was conducted via the web-based platform (https://www.wjx.cn/), utilizing a digital questionnaire format. Participants were randomly selected from several universities, including Guilin University of Technology, Chongqing Three Gorges University, Kashi University, Yuzhang Normal University, Heilongjiang University, and Harbin Institute of Technology. The survey was introduced to students by counselors during class meetings, who explained its purpose and significance. Participants were randomly selected from class rosters using computer-generated random numbers, ensuring a representative sample. Counselors then shared the survey link, emphasizing voluntary participation and privacy protection. For participants under the age of 18, informed consent was additionally obtained from their parents or legal guardians in accordance with ethical guidelines.

The sample size calculation, based on Kline47, required at least 10 respondents per survey item. Considering 62 items and accounting for a 20% attrition rate, the minimum required sample size was calculated as 744 participants (62 × 10 + 20% additional buffer). All 767 distributed surveys were completed and retrieved, resulting in a 100% response rate. Following the data screening process, 19 questionnaires were excluded due to missing responses or extreme answers (either completely agree or completely disagree), leaving 748 valid questionnaires for analysis.

Detailed demographic information is presented in Table 1: there were 247 male participants (33.021%) and 501 female participants (66.979%); the majority of the participants were aged between 18 and 22 years, with 581 participants (77.674%); the grade level was predominantly second-year students, with 272 participants (36.364%). To examine whether demographic variables were associated with differences in social anxiety levels, independent-sample t-tests were conducted for binary variables (e.g., gender), and one-way ANOVAs were used for multi-category variables (e.g., age and grade level). The corresponding p values were reported in Table 1. Gender (p < 0.05) showed a significant difference in social anxiety, while age (p > 0.05) and grade level (p > 0.05) did not show significant differences in social anxiety. This representative sample provided a solid foundation for analyzing adolescent classroom participation. The variety and scale of the sample contributed to the applicability of the study results to a wider adolescent group in this specific context.

Measurement tools

The translation task was handled by two researchers with distinct expertise: one, a bilingual educational psychology expert, and the other, a linguist with a deeper understanding of Chinese. Each translated the English questionnaire into Chinese. After completing the draft translations, both versions were carefully compared and reviewed, leading to a consolidated version. A pilot test was conducted on this version using 20 students from Chinese universities. Based on feedback, adjustments were made to parts of the questionnaire that differed from the original English version or that were awkward in phrasing, leading to the final Chinese version.

The Resilience Scale was developed by Dong et al.48. The scale contains 14 items, such as “I feel proud of the achievements I have made in my life”. It uses a 7-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). A higher total score indicated better resilience. In the study by Dong et al.48, the Cronbach’s alpha for this scale was 0.925. In the present study, the Cronbach’s alpha for the Resilience Scale was 0.898, demonstrating high reliability. The scale’s Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) value was 0.942, and the Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity yielded significant results (p < 0.001).

The Social Anxiety Scale was revised by Xu and Li3. This scale includes 15 items, including “I often feel nervous even in informal gatherings”. Reverse scoring is applied to items 3, 6, 10, and 15. The scale uses a 5-point Likert scale. In the study by Xu and Li3, the Cronbach’s alpha for this scale was 0.86. In the present study, the Cronbach’s alpha for the Social Anxiety Scale was 0.817, demonstrating good reliability. The scale’s KMO value was 0.859, and Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity yielded significant results (p < 0.001).

The Emotion Regulation Questionnaire was adapted from Sheng et al.49. The questionnaire includes two dimensions, cognitive reappraisal and expressive suppression, comprising a total of 10 items. The cognitive reappraisal dimension includes 6 items, such as “I control my emotions by changing my thinking about the current situation”. The expressive suppression dimension includes 4 items, such as “I hide my emotions”. The scale uses a 7-point Likert scale. In the study by Sheng et al.49, the Cronbach’s alpha for the cognitive reappraisal and expressive suppression dimensions were 0.85 and 0.77, respectively. In the present study, the Cronbach’s alpha for the cognitive reappraisal dimension was 0.848, indicating good reliability. The scale’s KMO value was 0.862, and Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity yielded significant results (p < 0.001). The Cronbach’s alpha for the expressive suppression dimension was 0.796, also showing good reliability. The KMO value was 0.787, and Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity was significant (p < 0.001).

The Simple Coping Styles Scale was adapted from Wang et al.50. This scale includes two dimensions: approach coping strategies and avoidance coping strategies, with a total of 20 items. The approach coping strategies dimension consists of 12 items, such as “When faced with setbacks, I relieve stress by working, studying, or engaging in other activities”. The avoidance coping strategies dimension consists of 8 items, such as “When faced with setbacks, I cope by smoking, drinking, using drugs, or eating to relieve my distress”. The scale uses a 4-point Likert scale. In the study by Wang et al.50, the Cronbach’s alpha for this scale was 0.951. In the present study, the Cronbach’s alpha for the approach coping strategies dimension was 0.779, indicating good reliability. The KMO value was 0.775, and Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity yielded significant results (p < 0.001). The Cronbach’s alpha for the avoidance coping strategies dimension was 0.715, also demonstrating good reliability. The KMO value was 0.785, and Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity was significant (p < 0.001).

Statistical analysis

The statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS 26.0. The first stage of analysis involved testing the measurement instruments for potential common method variance. Following this, the study utilized Spearman’s correlation to assess the interrelations between trait resilience, social anxiety, emotion regulation, and coping strategies. In the third step, the study employed the SPSS PROCESS macro with Model 4 to carry out a mediation analysis using the bootstrap method. Trait resilience was entered as the predictor variable (X), while four mediators were tested: cognitive reappraisal (M1), expressive suppression (M2), approach coping strategies (M3), and avoidance coping strategies (M4). Social anxiety functioned as the outcome variable (Y), and demographic variables such as age, gender, and grade were controlled. Significance was determined based on 5000 bootstrap samples, with mediation effects deemed statistically meaningful if the bias-corrected 95% confidence interval excluded zero, following the guidelines of Preacher and Hayes51 and Hayes and Rockwood52.

Results

Common method bias test

The participants provided all the self-reported data, which could have introduced bias due to the method employed. Harman’s single-factor test was used to assess the potential existence of common method bias. The exploratory factor analysis indicated 12 factors with eigenvalues above 1, and the first factor explained 21.429% of the variance, falling short of the 40% threshold. This finding confirmed that common method bias is not a major issue.

Collinearity test

To ensure the stability of the model and the validity of the interpretations, this study conducted a detailed diagnosis of collinearity among the independent variables. Tolerance and Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) values were calculated using SPSS to assess potential multicollinearity issues. The data in Table 2 showed that all tolerance values were greater than 0.1, and the VIF values ranged from 1.174 to 2.504. Tolerance values greater than 0.1 indicated that there are no severe collinearity issues, and VIF values below 3.3 were considered ideal53. This suggested that multicollinearity has an acceptable level of impact on the study.

Correlation between research variables

The correlation analysis in Table 3 provided the means (M), standard deviations (SD), and correlations of the study variables. Trait resilience was significantly positively correlated with cognitive reappraisal (r = 0.746, p < 0.001) and approach coping strategies (r = 0.542, p < 0.001), and significantly negatively correlated with social anxiety (r = − 0.486, p < 0.001), expressive suppression (r = − 0.314, p < 0.001), and avoidance coping strategies (r = − 0.110, p < 0.001). Therefore, H1, H2, H3, H4, H5 was supported. Approach coping strategies (r = − 0.552, p < 0.001) and cognitive reappraisal (r = − 0.361, p < 0.001) were significantly negatively correlated with social anxiety, while expressive suppression (r = 0.445, p < 0.001) and avoidance coping strategies (r = 0.418, p < 0.001) were significantly positively correlated with social anxiety. Therefore, H6,H7,H8,H9 was supported.

Mediation effect analysis

After adjusting for demographic variables such as gender, age, and grade, the regression analysis results were presented in Table 4. Trait resilience significantly positively influenced cognitive reappraisal (β = 0.780, p < 0.001) and approach coping strategies (β = 0.246, p < 0.001), and significantly negatively influenced expressive suppression (β = − 0.449, p < 0.001) and avoidance coping strategies (β = − 0.061, p < 0.001). Trait resilience (β = − 0.173, p < 0.001) and approach coping strategies (β = − 0.589, p < 0.001) had significant negative effects on social anxiety. In contrast, cognitive reappraisal (β = 0.060, p < 0.05) expressive suppression (β = 0.041, p < 0.01), and avoidance coping strategies (β = 0.401, p < 0.001) showed significant positive effects on social anxiety.

The mediation effects indicated (as shown in Table 5 and Fig. 2) that, in terms of the total effect, trait resilience significantly negatively influenced social anxiety (β = − 0.314, p < 0.001). Regarding the direct effect, trait resilience also had a significant direct negative effect on social anxiety (β = − 0.173, p < 0.001). Trait resilience exerted an indirect positive effect on social anxiety through cognitive reappraisal (β = 0.047, 95% CI 0.001,0.096). Trait resilience had an indirect negative effect on social anxiety through expressive suppression (β = − 0.019, 95% CI − 0.037, − 0.002). Trait resilience exerted an indirect negative effect on social anxiety through approach coping strategies (β = − 0.145, 95% CI − 0.185, − 0.107). Finally, trait resilience had an indirect negative effect on social anxiety through avoidance coping strategies (β = − 0.025, 95% CI − 0.045, − 0.006). Therefore, H10, H11, H12, and H13 were supported.

Discussion

Focusing on college students, this study investigates the primary contributors to social anxiety, emphasizing how emotion regulation and coping strategies function as intermediaries in the association between trait resilience and social anxiety. The study hypothesized that trait resilience is a key predictor of social anxiety in college students and that emotion regulation and coping strategies mediate this relationship. Using SPSS, the study found that trait resilience, emotion regulation, and coping strategies all significantly predict social anxiety. The findings reveal a negative relationship between trait resilience and social anxiety, with cognitive reappraisal and expressive suppression, as well as approach and avoidance coping strategies, serving as mediators. Contrary to expectations, cognitive reappraisal was shown to indirectly increase social anxiety in the context of its relationship with trait resilience. The following sections discuss these findings in detail.

Trait resilience is significantly negatively correlated with social anxiety, a finding supports the conclusions drawn by Li et al.22. Their study, which explored the factors influencing social anxiety among college students, confirmed a marked negative connection between trait resilience and social anxiety. Resilience theory emphasizes that, when facing adversity, individuals not only regain their previous state but also accomplish psychological growth and enhanced self-efficacy54. Those with higher trait resilience tend to have stronger belief in their skills to manage adversity, which enables them to navigate difficult social situations more calmly and reduces social anxiety caused by concerns over negative evaluation24,26. Furthermore, resilient individuals are able to quickly adjust their mindset after setbacks, learning from failures rather than becoming trapped in negative emotional cycles25. When encountering awkward or unpleasant situations in social settings, they view these moments as opportunities for learning rather than signs of personal flaws. Such mindset adjustments help reduce future social anxiety22. This finding suggests that enhancing individual trait resilience may be an important avenue for alleviating social anxiety. By boosting trait resilience, individuals can better cope with various challenges in social settings, thereby gaining stronger psychological adaptability and confidence.

Cognitive reappraisal was found to mediate the relationship between trait resilience and social anxiety. However, the direction of this effect differs from the findings of McBride et al.6, who reported a strong inverse relationship between cognitive reappraisal and social anxiety, emphasizing that cognitive reappraisal encourages individuals to view situations from alternative perspectives, thereby potentially alleviating social anxiety. Similarly, Cutajar and Bates10 highlighted that cognitive reappraisal helps reduce negative automatic thoughts and serves as an important means of enhancing emotional regulation. Opposing earlier assumptions, the current research found that trait resilience indirectly contributed to heightened social anxiety through the mechanism of cognitive reappraisal. Despite the positive link between elevated trait resilience and increased use of cognitive reappraisal, this regulatory approach failed to mitigate social anxiety and was even linked to heightened symptoms in some cases. One possible explanation is the occurrence of a “paradoxical effect” when cognitive reappraisal is overused or applied inappropriately. Under such circumstances, individuals may exhibit evaluative biases and become excessively self-focused on their performance in social situations, thereby intensifying anxiety55. Moreover, Dryman and Heimberg56 observed that people with elevated levels of social anxiety frequently doubt their capacity to manage negative emotions effectively. As a result, even when employing cognitive reappraisal, they may experience reduced efficacy or even emotional frustration, which could further reinforce their anxiety.

Expressive suppression mediates the relationship between trait resilience and social anxiety. This outcome supports the conclusions of existing research by Alismail and Almulla28, which revealed that individuals with lower trait resilience tend to rely more on expressive suppression, potentially leading to the emergence of anxiety. Individuals exhibiting reduced trait resilience are particularly prone to holding back their emotions in socially challenging or distressing contexts, aiming to avoid adverse judgments or potential interpersonal disputes7,16. However, the use of expressive suppression did not effectively alleviate internal discomfort; rather, it may have led to emotional buildup and accumulation, intensifying anxiety and tension33. Furthermore, individuals with lower trait resilience often harbor doubts about their ability to handle interpersonal relationships, and this lack of confidence makes them more likely to use expressive suppression strategies28. High levels of expressive suppression mean that these individuals are more inclined to hide their true feelings during social interactions, which not only limits their opportunities to receive social support but also may lead to misunderstandings and feelings of isolation, further exacerbating social anxiety6. Prolonged reliance on expressive suppression may contribute to the formation of negative self-perceptions, fostering self-denigrating emotions33,34. This negative self-evaluation tendency can intensify social anxiety, especially in social situations where individuals may excessively worry about exposing their flaws and mistakes7.

Approach coping strategies serve as an intermediary in the link between trait resilience and social anxiety. These results echo the conclusions drawn by Yu et al.38, which demonstrated that people with greater trait resilience tend to adopt approach coping strategies, helping them effectively manage their emotional states and reduce anxiety levels. Those with elevated levels of trait resilience often engage in encouraging and adaptive internal dialogue to cope with stressful encounters or anticipated social interactions41. They believe in their ability to cope with difficulties and maintain a positive mindset, which enhances their sense of self-efficacy and effectively reduces the occurrence of social anxiety8,40. Furthermore, approach coping strategies also involve seeking and effectively utilizing social support. Those demonstrating strong trait resilience often exhibit a greater tendency to proactively seek help from others when faced with difficulties, obtaining emotional comfort and solutions through communication and support. This seeking of support not only alleviates immediate stress but also strengthens social connections and a sense of belonging26. By establishing and maintaining support networks, individuals can gain a stronger sense of security, reduce feelings of loneliness and helplessness, and thus lower the level of social anxiety8.

Avoidance coping strategiesmediate the relationship between trait resilience and social anxiety. These results are consistent with the conclusions drawn by Yu et al.38, which showed that trait resilience levels influence the way individuals choose coping strategies, thus impacting their anxiety levels. Avoidance coping strategies often manifest as avoiding or ignoring problems43. When trait resilience is low, individuals are less likely to possess the necessary skills for proactive problem-solving and are more inclined to respond with evasion or delay41. This coping strategy not only fails to resolve the issues but also leads to the accumulation of problems, increasing stress and uncertainty, which in turn exacerbates social anxiety46. Those with weaker trait resilience tend to adopt negative cognitive habits, such as overgeneralization and catastrophizing, which drive them to adopt avoidance coping strategies and reinforce a pessimistic view of their abilities and future prospects, further intensifying social anxiety39. Consistent dependence on avoidance coping strategies over time may undermine individuals’ confidence in handling challenges, leading to a decline in perceived self-efficacy9,11. A diminished belief in one’s capacity to manage difficulties can give rise to fears of failure and apprehension about others’ evaluations, frequently manifesting as intensified nervousness and social anxiety9,39.

Impact

Theoretical implications

To begin with, this research draws upon resilience theory alongside the PMER to examine, in an integrated manner, the interactive effects of trait resilience, emotion regulation processes, and coping mechanisms on social anxiety within a university student population. This research constructs and tests a structural framework to explore the intermediary roles played by cognitive reappraisal, expressive suppression, and both approach- and avoidance-oriented coping strategies. The findings shed light on a more profound comprehension of the protective mechanisms of trait resilience in social anxiety and offer novel theoretical directions to guide subsequent studies within the field of educational psychology.

Secondly, the present investigation delves deeply into the pathways through which trait resilience affects social anxiety, innovatively combining the PMER with TMSC. This research investigates the indirect pathways through which emotion regulation and coping strategies link trait resilience to social anxiety. The study’s outcomes highlight an inverse relationship between trait resilience and social anxiety, indicating that trait resilience may impact social anxiety indirectly through the mediating roles of cognitive reappraisal, expressive suppression, approach coping strategies, and avoidance coping strategies. This result underscores the complex role of emotion regulation and coping strategies in individuals’ responses to social anxiety, emphasizing trait resilience as a vital psychological resource for alleviating social anxiety.

Practical implications

First, in terms of practical significance for college students, the results of this study emphasize the vital influence of trait resilience, emotion regulation, and coping strategies in the effective management of social anxiety. College students need to understand that cultivating trait resilience can enhance their ability to manage the stresses associated with academics, daily life, and social interactions. Therefore, trait resilience can be enhanced through regular exercise, cultivating a positive mindset, and strengthening self-efficacy57,58. To cope with social challenges, students should be guided to apply cognitive reappraisal and approach coping strategies in practical ways, including fostering constructive internal dialogue, utilizing calming exercises, establishing personal objectives, and proactively seeking assistance from others. However, students should also be mindful of avoiding excessive or inappropriate use of cognitive reappraisal, as this may potentially exacerbate social anxiety.

Secondly, with respect to the practical significance for educators, teachers can provide students with effective mental health counseling programs to help them manage social anxiety through emotion regulation techniques, enhancing their self-awareness and social adaptability. Additionally, schools can incorporate emotion regulation techniques and coping strategy usage into mental health curricula to help students better manage stress and anxiety through approach coping strategies, thus increasing their sense of self-efficacy when facing challenges. Furthermore, schools can organize group counseling sessions, workshops, and other activities to enhance students’ emotion regulation skills and coping strategies, thereby improving their overall mental well-being.

Limitations and suggestions for future research

Despite offering valuable insights into the links among trait resilience, emotion regulation, coping strategies, and social anxiety, this research is not without limitations, which warrant further examination in subsequent studies. First, the study employed a self-report questionnaire method, which, while effective for collecting subjective data from large samples, carries the risk of bias. Future research could incorporate a combination of experimental methods, longitudinal studies, and both qualitative and quantitative approaches to provide more comprehensive and multi-dimensional data. Secondly, the reliance on cross-sectional data constrains the interpretation of cause-and-effect dynamics and prevents clear identification of the temporal sequencing between the variables under investigation. To uncover the timing and progression of these effects, subsequent research may benefit from employing experimental methods or longitudinal tracking. Third, some of the assessment tools utilized in this research were originally designed in the English language. The translation process was carried out by bilingual researchers with a background in psychology and involved multiple rounds of review and cultural adaptation to ensure linguistic accuracy and contextual appropriateness. Although the translation procedure was rigorous, a formal back-translation process was not employed, which may have limited the equivalence of the scales in cross-linguistic applications to some extent. To strengthen measurement accuracy and facilitate cross-cultural consistency, upcoming research may consider employing back-translation techniques in the adaptation process. Lastly, this research involved a gender-imbalanced sample, as females represented 66.979% of all respondents, indicating a notable overrepresentation. The observed gender skew in the sample may stem from differing levels of participation between male and female students, which could limit the applicability of the study’s conclusions to broader populations. To strengthen the broader applicability of future findings, upcoming research should prioritize obtaining a more proportionate gender distribution within the sample. Despite these limitations, the study has notable strengths. The inclusion of a heterogeneous participant group improves the study’s external validity, while employing rigorously validated scales ensures consistency and dependability in the results. Additionally, the research design effectively addresses the complex relationships between key psychological constructs, providing valuable insights for future studies in this area.

Conclusion

Grounded in TMSC and coping and PMER, this research systematically examined how trait resilience influences social anxiety in college students, confirming the mediating roles of cognitive reappraisal, expressive suppression, approach coping strategies, and avoidance coping strategies. The study found a notable inverse connection between trait resilience and social anxiety, with expressive suppression, approach coping strategies, and avoidance coping strategies acting as negative mediators between trait resilience and social anxiety, while cognitive reappraisal played a positive mediating role. This study not only broadens the conceptual model of resilience theory and social anxiety but also provides practical guidance for educators in optimizing teaching strategies and formulating educational policies. To conclude, the present study contributes fresh theoretical and practical implications for comprehending and managing social anxiety in university students, and it outlines meaningful paths for subsequent scholarly exploration.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Abbreviations

- TMSC:

-

Transactional model of stress and coping

- PMER:

-

Process model of emotion regulation

- COR:

-

Conservation of resources

- TR:

-

Trait resilience

- ER:

-

Emotion regulation

- CS:

-

Coping strategies

- APC:

-

Approach coping

- AVC:

-

Avoidance coping

- CR:

-

Cognitive reappraisal

- ES:

-

Expressive suppression

- SA:

-

Social anxiety

- KMO:

-

Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- VIF:

-

Variance inflation factor

- SD:

-

Standard deviations

References

Zhao, C. et al. The roles of classmate support, smartphone addiction, and leisure time in the longitudinal relationship between academic pressure and social anxiety among Chinese adolescents in the context of the “double reduction” policy. Child Youth Serv. Rev. 160, 107542. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2024.107542 (2024).

Luan, Y. S. et al. The Experience among college students with social anxiety disorder in social situations: A qualitative study. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 18, 1729–1737. https://doi.org/10.2147/ndt.S371402 (2022).

Xu, L. J. & Li, L. Upward social comparison and social anxiety among Chinese college students: A chain-mediation model of relative deprivation and rumination. Front. Psycho. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2024.1430539 (2024).

Awadalla, S., Davies, E. B. & Glazebrook, C. A longitudinal cohort study to explore the relationship between depression, anxiety and academic performance among Emirati university students. BMC Psychiatry https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-020-02854-z (2020).

Hobfoll, S. E. Conservation of resources—A new attempt at conceptualizing stress. Am. Psychol. 44, 513–524. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066x.44.3.513 (1989).

McBride, N. L., Bates, G. W., Elphinstone, B. & Whitehead, R. Self-compassion and social anxiety: The mediating effect of emotion regulation strategies and the influence of depressed mood. Psychol. Psychother. Theory Res. Pract. 95, 1036–1055. https://doi.org/10.1111/papt.12417 (2022).

Kivity, Y., Cohen, L., Weiss, M., Elizur, J. & Huppert, J. D. The role of expressive suppression and cognitive reappraisal in cognitive behavioral therapy for social anxiety disorder: A study of self-report, subjective, and electrocortical measures. J. Affect. Disord. 279, 334–342. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2020.10.021 (2021).

Liu, F., Wang, N. X. & Chen, L. Neuroticism and positive coping style as mediators of the association between childhood psychological maltreatment and social anxiety. Curr. Psychol. 42, 10935–10944. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-021-02360-9 (2023).

Li, D. M. Influence of the youth’s psychological capital on social anxiety during the covid-19 pandemic outbreak: The mediating role of coping style. Iran. J. Public Health 49, 2060–2068. https://doi.org/10.18502/ijph.v49i11.4721 (2020).

Cutajar, K. & Bates, G. W. Australian women in the perinatal period during COVID-19: The influence of self-compassion and emotional regulation on anxiety, depression, and social anxiety. Healthcare https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13020120 (2025).

Yang, T. Y. et al. Coping style predicts sense of security and mediates the relationship between autistic traits and social anxiety: Moderation by a polymorphism of the FKBP5 gene. Behav. Brain Res. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbr.2021.113142 (2021).

Trudel-Fitzgerald, C. et al. Coping and emotion regulation: A conceptual and measurement scoping review. Can. Psychol. Psychol. Can. 65, 149–162. https://doi.org/10.1037/cap0000377 (2024).

Gross, J. J. The emerging field of emotion regulation: An integrative review. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 2, 271–299. https://doi.org/10.1037/1089-2680.2.3.271 (1998).

Gross, J. J. & John, O. P. Individual differences in two emotion regulation processes: Implications for affect, relationships, and well-being. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 85, 348–362. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.85.2.348 (2003).

Gross, J. J. Emotion regulation in adulthood: Timing is everything. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 10, 214–219 (2001).

Renati, R., Bonfiglio, N. S. & Rollo, D. Italian university students’ resilience during the covid-19 lockdown-a structural equation model about the relationship between resilience, emotion regulation and well-being. Eur. J. Investig. Health Psychol. Educ. 13, 259–270. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe13020020 (2023).

San Román-Mata, S., Puertas-Molero, P., Ubago-Jiménez, J. L. & González-Valero, G. Benefits of physical activity and its associations with resilience, emotional intelligence, and psychological distress in university students from Southern Spain. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17124474 (2020).

Lazarus, R. S. Stress, Appraisal, and Coping Vol. 464 (Springer, 1984).

Folkman, S., Lazarus, R. S., Dunkel-Schetter, C., DeLongis, A. & Gruen, R. J. Dynamics of a stressful encounter: Cognitive appraisal, coping, and encounter outcomes. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 50, 992 (1986).

Lazarus, R. S. From psychological stress to the emotions—A history of changing outlooks. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 44, 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.ps.44.020193.000245 (1993).

Ko, C. Y. A. & Chang, Y. S. Investigating the relationships among resilience, social anxiety, and procrastination in a sample of college students. Psychol. Rep. 122, 231–245. https://doi.org/10.1177/0033294118755111 (2019).

Li, X. et al. Physical activity and social anxiety symptoms among Chinese college students: a serial mediation model of psychological resilience and sleep problems. BMC Psychol. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-024-01937-w (2024).

Wan, Z. D., Chen, Y. F., Wang, L. J. & Cheng, M. F. The relationship between interparental conflict and social anxiety among Chinese college students: A moderated mediation model. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 17, 3965–3977. https://doi.org/10.2147/prbm.S481086 (2024).

Yu, Y., Liu, S., Song, M. H., Fan, H. & Zhang, L. Effect of parent-child attachment on college students’ social anxiety: A moderated mediation model. Psychol. Rep. 123, 2196–2214. https://doi.org/10.1177/0033294119862981 (2020).

Shuai, J., Cai, G. Y. & Wei, X. A. Social exclusion and social anxiety among Chinese undergraduate students: Fear of negative evaluation and resilience as mediators. J. Psychol. Afr. 34, 44–51. https://doi.org/10.1080/14330237.2023.2290432 (2024).

Li, X. et al. Effects of empathy on loneliness among rural left-behind children in China: The chain-mediated roles of social anxiety and psychological resilience. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 17, 3369–3379. https://doi.org/10.2147/prbm.S477556 (2024).

Wen, X. L. et al. A cross-sectional association between screen-based sedentary behavior and anxiety in academic college students: Mediating role of negative emotions and moderating role of emotion regulation. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 16, 4221–4235. https://doi.org/10.2147/prbm.S430928 (2023).

Alismail, A. M. & Almulla, M. O. Role of psychological resilience in predicting emotional regulation among students of King Faisal University in Al-Ahsa governorate. Eurasian J. Educ. Res. https://doi.org/10.14689/ejer.2023.105.008 (2023).

Surzykiewicz, J., Skalski, S. B., Solbut, A., Rutkowski, S. & Konaszewski, K. Resilience and regulation of emotions in adolescents: Serial mediation analysis through self-esteem and the perceived social support. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19138007 (2022).

Jiang, Y. F., Qiao, T. T., Zhang, Y., Wu, Y. L. & Gong, Y. Social support and vicarious posttraumatic growth among psychological hotline counselors during COVID-19: The role of resilience and cognitive reappraisal. Health Psychol. Behav. Med. https://doi.org/10.1080/21642850.2023.2274550 (2023).

Tsarpalis-Fragkoulidis, A. & Zemp, M. Associations between fears of evaluation, emotion regulation, and social anxiety in adolescents: A structural equation model. Psychol. Erziehung Und Unterricht https://doi.org/10.2378/peu2024.art11d (2024).

Warnock-Parkes, E. et al. ‘I’m unlikeable, boring, weird, foolish, inferior, inadequate’: How to address the persistent negative self-evaluations that are central to social anxiety disorder with cognitive therapy. Cognit. Behav. Ther. https://doi.org/10.1017/s1754470x22000496 (2022).

Qu, T. T., Gu, Q. W., Yang, H., Wang, C. N. & Cao, Y. P. The association between expressive suppression and anxiety in Chinese left-behind children in middle school: Serial mediation roles of psychological resilience and self-esteem. BMC Psychiatry https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-024-05997-5 (2024).

Fu, W. Q., Zhang, W. D., Dong, Y. H. & Chen, G. Y. Parental control and adolescent social anxiety: A focus on emotional regulation strategies and socioeconomic influences in China. Br. J. Dev. Psychol. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjdp.12525 (2024).

Pearlin, L. I. & Schooler, C. The structure of coping. J. Health Soc. Behav. 19, 2–21. https://doi.org/10.2307/2136319 (1978).

Roth, S. & Cohen, L. J. Approach, avoidance, and coping with stress. Am. Psychol. 41, 813–819. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.41.7.813 (1986).

Qi, L., Zhang, H. L., Nie, R. & Du, Y. Resilience promotes self-esteem in children and adolescents with hearing impairment: The mediating role of positive coping strategy. Front. Psychol. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2024.1341215 (2024).

Yu, X. M., Yang, Y. & He, B. The effect of athletes’ training satisfaction on competitive state anxiety-a chain-mediated effect based on psychological resilience and coping strategies. Front. Psychol. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2024.1409757 (2024).

Macía, P., Barranco, M., Gorbeña, S., Alvarez-Fuentes, E. & Iraurgi, I. Resilience and coping strategies in relation to mental health outcomes in people with cancer. PLoS ONE https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0252075 (2021).

de la Fuente, J. et al. Cross-sectional study of resilience, positivity and coping strategies as predictors of engagement-burnout in undergraduate students: Implications for prevention and treatment in mental well-Being. Front. Psychiatry https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2021.596453 (2021).

Ma, A. N. et al. The impact of adolescent resilience on mobile phone addiction during COVID-19 normalization and flooding in China: A chain mediating. Front. Psychol. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.865306 (2022).

Zheng, Y., Wang, X., Deng, Y. & Wang, J. Effect of psychological resilience on posttraumatic growth among midwives: The mediating roles of perceived stress and positive coping strategies. Nurs. Open https://doi.org/10.1002/nop2.70076 (2024).

Wang, T., Jiang, L. W., Li, T. T., Zhang, X. H. & Xiao, S. R. The relationship between intolerance of uncertainty, coping style, resilience, and anxiety during the COVID-19 relapse in freshmen: A moderated mediation model. Front. Psychiatry https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2023.1136084 (2023).

Bradson, M. L. & Strober, L. B. Coping and psychological well-being among persons with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis: The role of perceived self-efficacy. Mult. Scler. Relat. Disord. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.msard.2024.105495 (2024).

Li, Y. & Peng, J. Does social support matter? The mediating links with coping strategy and anxiety among Chinese college students in a cross-sectional study of COVID-19 pandemic. BMC Public Health https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-021-11332-4 (2021).

Shukla, A. & Chouhan, V. S. Association between cyberbullying victimization and loneliness among adolescents: The role of coping strategies and emotional intelligence. Int. J. Cyber Behav. Psychol. Learn. https://doi.org/10.4018/ijcbpl.330586 (2023).

Kline, R. B. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling 4th edn. (The Guilford Press, 2016).

Dong, S. H. et al. Enhancing psychological well-being in college students: The mediating role of perceived social support and resilience in coping styles. BMC Psychol. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-024-01902-7 (2024).

Sheng, X. X., Wen, X. L., Liu, J. S., Zhou, X. X. & Li, K. Effects of physical activity on anxiety levels in college students: Mediating role of emotion regulation. PeerJ https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.17961 (2024).

Wang, Y. W., Fu, T. T., Wang, J., Chen, S. F. & Sun, G. X. The relationship between self-compassion, coping style, sleep quality, and depression among college students. Front. Psychol. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2024.1378181 (2024).

Preacher, K. J. & Hayes, A. F. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behav. Res. Methods 40, 879–891. https://doi.org/10.3758/brm.40.3.879 (2008).

Hayes, A. F. & Rockwood, N. J. Regression-based statistical mediation and moderation analysis in clinical research: Observations, recommendations, and implementation. Behav. Res. Ther. 98, 39–57. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2016.11.001 (2017).

Hair, J. F., Sarstedt, M. & Ringle, C. M. Rethinking some of the rethinking of partial least squares. Eur. J. Mark. 53, 566–584. https://doi.org/10.1108/ejm-10-2018-0665 (2019).

Xu, Y. H., Yang, G., Yan, C. S., Li, J. T. & Zhang, J. W. Predictive effect of resilience on self-efficacy during the COVID-19 pandemic: The moderating role of creativity. Front. Psychiatry https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2022.1066759 (2022).

Scherer, K. R. Emotion regulation via reappraisal—Mechanisms and strategies. Cogn. Emot. 37, 353–356. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699931.2023.2209712 (2023).

Dryman, M. T. & Heimberg, R. G. Emotion regulation in social anxiety and depression: A systematic review of expressive suppression and cognitive reappraisal. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 65, 17–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2018.07.004 (2018).

Cao, L. G., Ao, X. R., Zheng, Z. R., Ran, Z. B. & Lang, J. Exploring the impact of physical exercise on mental health among female college students: The chain mediating role of coping styles and psychological resilience. Front. Psychol. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2024.1466327 (2024).

Jiang, R. C. The mediating role of emotional intelligence between self-efficacy and resilience in Chinese secondary vocational students. Front Psychiatry https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2024.1382881 (2024).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: Yonghan Li; Methodology: Yonghan Li; Formal analysis and investigation: Yonghan Li; Writing—original draft preparation: Yonghan Li; Writing—review and editing: Yonghan Li; Supervision: Pinglian Zheng. The corresponding author is Yonghan Li. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The researchers confirms that all research was performed in accordance with relevant guidelines/regulations applicable when human participants are involved (e.g., Declaration of Helsinki or similar). This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of University of Chongqing Three Gorges University. For participants under the age of 18, informed consent was additionally obtained from their parents or legal guardians in accordance with ethical guidelines.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, Y., Zheng, P. Trait resilience protects against social anxiety in college students through emotion regulation and coping strategies. Sci Rep 15, 28143 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-13674-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-13674-0

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Social Anxiety and Self-control Desire for Social Media Users: The Mediating Roles of Resilience and Social Media Usage

Journal of Rational-Emotive & Cognitive-Behavior Therapy (2026)