Abstract

Synechococcus HS-9 is being recognized as one of the potential strains for biodiesel production due to its high levels of fatty acid methyl ester (FAME), which are around 70–78%. The first stage in producing microalgae biodiesel involves the biomass production process through a photobioreactor cultivation process. In addition to microalgae strains, the optimization of the photobioreactor’s performance is essential for producing high biomass. In this case, biotic factors (microalgae inoculum) and abiotic factors (nutrients, temperature, light, pH, carbon dioxide (CO2), fluid flow, hydrodynamic processes, and mass transfer processes) are being regulated and optimized in the photobioreactor, which is influencing the growth rate of microalgae. The main objective of this study is examining the effect of hydrodynamics and mass transfer processes using the Rectangular Airlift Photobioreactor with Baffles (RAPBR-Bs) to increase the growth of Synechococcus HS-9 during the cultivation process. The study is consisting of two main parts: collecting bubble photography and video, and the cultivation process of Synechococcus HS-9. During the cultivation of Synechococcus HS-9, hydrodynamics, mass transfer, optical density (OD), and biomass weight data are being measured. The research results indicate that hydrodynamic parameters, including bubble properties such as bubble velocity (0.0064 m/s), bubble diameter (720 μm), non-dimensional numbers (Re 4.51; Eo 0.0126; Mo 8.87 × 10−12; We 6.85 × 10−5), superficial gas velocity (0.0008 m/s), bubble rise velocity (0.117 m/s), gas holdup (0.0072), and the mass transfer process (kLa O₂ (oxygen) 0.114 s−1; kLa CO₂ 0.099 s−1) in RAPBR-Bs are influencing and contributing to the growth of Synechococcus HS-9 during cultivation. The study found that Synechococcus HS-9 cultivated in RAPBR-Bs exhibited significant growth because the mixing and aeration processes are optimal. An optimal aeration process enhances the mass transfer coefficient, which in turn improves the overall mass transfer capacity of the RAPBR-Bs. The results are showing that the hydrodynamic and mass transfer properties of these RAPBR-Bs are being more efficient than those that are reported for other PBRs. Optimal conditions for Synechococcus HS-9 cultivation are occurring at day 13, as it is reaching the late exponential phase. The weight of the cultivated Synechococcus HS-9 biomass is 3.226 g.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Microalgae is recognized as one of the potential feedstocks for biodiesel production due to its high levels of fatty acid methyl ester (FAME), which are around 40–90%. Microalgae has higher oil content, oil yield, and biodiesel productivity compared to corn, soybean, sunflower, castor, and palm oil1. Microalgae biomass production requires a fairly long process to produce biodiesel. In principle, there are five main processes in producing microalgae biodiesel: cultivation, harvesting, drying, lipid extraction, and biodiesel synthesis. The cultivation process is the first stage in producing microalgae biomass, which includes open-system cultivation (open pond) and closed-system cultivation (closed pond). Microalgae include various strains that can serve as potential biodiesel feedstock, and this study specifically utilized the Synechococcus HS-9 strain sourced from the hot spring area in Banten, Indonesia2. And then, it was selected using a closed-system cultivation method to reduce the risk of higher contamination compared to the open-system cultivation3,4. Synechococcus HS-9 is a potential biodiesel raw material because it has high levels of FAME, 70–78%. Its monoculture is susceptible to contamination if contact with atmospheric air2.

A photobioreactor is a microalgae biomass production technology that uses a closed-system cultivation process. As microalgae cultivation mediums, photobioreactors are important to research. To maximise biomass, the photobioreactor must be optimised beyond microalgae strains. The photobioreactor allows for the management and optimization of biotic (microalgae inoculum) and abiotic (nutrients, temperature, light, pH, CO2, and fluid flow) factors that influence microalgae growth5,6. Microalgae cultivation aims at producing as much biomass as possible by optimizing the photobioreactor design and cultivation process7.

Microalgae carry out photosynthesis in a photobioreactor when the need for light and carbon dioxide (CO2) as an energy source for growth is met. CO2 influences photosynthesis as carbon is the basic element that forms microalgae cells. Microalgae dry biomass is estimated to contain 50% carbon elements8. Microalgae absorb water-soluble CO2 content (medium) during photosynthesis in the photobioreactor through an air distribution process (aeration). CO2 can dissolve in the medium well if the air distribution has micro-sized bubbles. Microbubbles with a 50–200 μm diameter have a higher surface area to volume ratio and a slower rising speed, so more CO2 can dissolve in the medium9,10.

Photobioreactors must be planned, manufactured, and operated to support and control microalgae demands in phototrophic conditions (conditions that support photosynthesis). Photobioreactors, as a biomass production technology, play an important role in research. The photobioreactor design should include key parameters such as mixing, water, medium, CO₂ consumption, O₂ reduction, lighting, nutrition provision, pH, and temperature control. Photobioreactor geometry must be maximized for biomass productivity. During microalgae cultivation, many of the parameters in the photobioreactor interact with each other. These include hydrodynamic parameters, heat/mass transfer, biological kinetics, and light supply. These interactions influence the productivity of microalgae biomass in the photobioreactor11. Research and development of photobioreactors for microalgae cultivation has not been optimal. This is because microalgae are unique microorganisms and have different characteristics. Several studies have been conducted on the influence of hydrodynamic parameters and mass transfer on microalgae growth in photobioreactors.

Reyna et al., (2010) cultivated Spirulina sp. using a flat-plate airlift photobioreactor (FPA-PBR) with a volume of 50 L. The study examined FPA-PBR hydrodynamics and mass transfer in a two-phase (air-water) or three-phase (medium, Spirulina sp., and air) operating system with regulated air velocity under high light intensity. Researchers examined the superficial gas velocity, gas hold-up, mixing time, and volumetric mass transfer coefficient (kLa). The research found that FPA-PBR had better hydrodynamics and mass transfer than tubular and flat-plate PBRs12. Furthermore, Jones et al., (2014) cultivated Scenedesmus sp. in an airlift photobioreactor. The research parameters were net energy ratio (NER), superficial gas velocity, CO2 concentration, mass transfer coefficient, biomass productivity, and lipid production. The gas phase had the highest CO2 content (5,400 − 10,400 ppm) and could reduce surface gas velocity four times from 0.02 m/s without affecting biomass concentration or productivity. Lowering surface gas velocity below 0.005 m/s could reduce biomass. Lower CO2 concentrations (400-1,400 ppm) could reduce productivity and superficial gas velocity13.

Zhao et al. (2018) cultivated Chlorella vulgaris(C. vulgaris) in a crossflow plate photobioreactor (CFP-PBR). CFD simulations were used to improve gas-medium-microalgae mixing, mass transfer, and photosynthetic rate at high culture density. Mixing time, gas hold-up, residence time, mass transfer coefficient, and microalgae culture baffle impact were studied. In the CFD simulation, crossed horizontal baffles increased mixing flow and decreased dead zone flow. According to experiments, crossed horizontal baffles could increase gas hold-up, residence time, mass transfer efficiency, and microalgae growth efficiency14. Furthermore, Singh et al. (2019) cultivated Chlorella pyrenoidosa in a bubble column photobioreactor (BC-PBR). The project aimed to make lipids from CO2. The study compared experimental data to determine the CO2 mass transfer coefficient, microalgae extinction (death) coefficient, growth effect, lipid production, and model validation. The results revealed that biomass productivity was 0.91 mg/L/day with sufficient urea, and lipid productivity was 410 mg/L/day on the last two days of urea deficiency15. Rahman et al. (2021) cultivated Synechococcus HS-9 using a novel rectangular bubble column photobioreactor with a horizontal baffle. The study investigated how baffles affect bubble size, distribution, speed, and coalescence phenomenon, and affect Synechococcus HS-9 growth. This studied the growth curve of Synechococcus HS-9, Weber number, bubble coalescence phenomenon, pH value, and the size, distribution, and velocity of bubbles. Synechococcus HS-9 grew better in photobioreactors with baffles than in those without. The PBR contains baffles that affect bubble size, distribution, velocity, and coalescence phenomena, which increase Synechococcus HS-9 growth16. However, research on the cultivation process of Synechococcus HS-9 using the novel rectangular bubble column photobioreactor with a horizontal bubble was still not optimal, especially the size and shape of the sparger and baffle.

Another study, Shadpour et al. (2022) cultivated C. vulgaris in a triangular external loop airlift photobioreactor (TELA-PBR). This study examined how geometry and operational parameters affect system performance and how surface gas velocity affects hydrodynamic and mass transfer behaviour. Research indicates that superficial gas velocity and hypotenuse angle (α) significantly impact hydrodynamic and mass transfer processes in the TELA-PBR system17. Zarei et al. (2023) cultivated Anabaena sp. in an internal loop airlift photobioreactor. This study examined hydrodynamic processes for biohydrogen production from Anabaena sp. grown in an airlift photobioreactor at 0.185 and 0.524 cm/s. With increasing inlet gas velocity, oxygen mass transfer coefficient, gas holdup, gas velocity, and liquid circulation velocity increased without shear stress damaging cyanobacteria18.

Previous studies examined various types of photobioreactor designs and configurations. Furthermore, the results of previous studies show that airflow, distribution of nutrients (medium), pH, and light supply are important factors that influence the growth process of microalgae. Photobioreactors with the airlift concept carry out the process of mixing and mass transfer between gas and water with the help of spargers which form micro-sized bubbles. It is known that the airlift photobioreactor has good gas-water mass transfer capabilities. Moreover, the factors influencing increased mixing and mass transfer in airlift photobioreactors were geometric design, aeration process, sparger type, and bubble distribution10. Bubble distribution greatly influences hydrodynamic parameters (bubble diameter and velocity) and non-dimensional numbers, superficial gas velocity, bubble rise velocity, and gas hold-up, which are important parameters for knowing the mass transfer process and performance of the photobioreactor. These parameters can influence the growth rate and productivity of microalgae biomass. However, the optimization of geometric design, hydrodynamic processes, mass transfer, and the influence of light in one type of photobioreactor have not been carried out optimally. More specifically, the use of baffles and spargers in airlift photobioreactors, which can influence hydrodynamic parameters and mass transfer, which can increase microalgae growth, has not been carried out optimally. Therefore, in this study, the researchers are interested in cultivating Synechococcus HS-9 using a rectangular airlift photobioreactor using baffles (RAPBR-Bs) with mushroom sparger.

The main objective of this research is the experimental study to determine the effect of hydrodynamic processes and mass transfer in RAPBR-Bs on increasing the growth of Synechococcus HS-9 during cultivation. Optimally utilizing modifications to the sparger and baffle shape of RAPBR-Bs from previous research is expected to increase the growth rate of Synechococcus HS-9. The mushroom sparger functions for aeration and bubble generation, and the baffle in the RAPBR-Bs functions to inhibit the movement of bubbles, thereby extending the residence time of the bubbles and CO₂ in the RAPBR-Bs. Baffles can also break large bubbles into smaller bubbles due to turbulence. This is really needed by Synechococcus HS-9, whose cell size is very small (0.9–2.5 μm) to absorb CO₂ to carry out the photosynthesis process. With the modification of the sparger and baffle shape in RAPBR-Bs, which is a novelty in this study, it is expected that the aeration process produced by the mushroom sparger and the position of the baffle will be able to produce optimal hydrodynamic and mass transfer parameters compared to other PBRs. In addition, the authors expect that the results reported here will assist other researchers in analysing and understanding the influence of hydrodynamic processes and mass transfer in RAPBR-Bs to increase the growth of Synechococcus HS-9 during cultivation.

Materials and methods

Research flowchart

This study is divided into two main parts: data collection of bubble photos and videos and the cultivation process of the Synechococcus HS-9. During cultivation, data were collected for hydrodynamic analysis, mass transfer, and microalgae cell density or optical density (OD). The research flowchart can be seen in Fig. 1 below. A and B show stages in analyzing photos and videos of bubbles (hydrodynamic processes), while C shows stages in analyzing mass transfer processes. This research involved numerous trials and errors to determine the appropriate physicochemical parameters for cultivating Synechococcus HS-9. This paper presents the results of a single, non-repeated experiment.

Data retrieval process of bubble photo and video

Data were collected by taking photos and recording videos of bubbles in the RAPBR-Bs, as shown in Fig. 2, using a Fastec TS5 high-speed camera. The steps for capturing bubble photo and video data are as follows: 1) Prepare and compile a series of RAPBR-Bs as presented in Figs. 2 and 3) Set the camera and the lighting to obtain focused and clear bubble photo and video; 3) Turn on the compressor and adjust the inlet air speed through the flow meter, i.e., 1–5 LPM; 4) Start capturing bubble photo and video; 5) Bubble photo and video data are stored in the hard disk.

The quality of bubble photos and videos was greatly influenced by camera quality, experimental equipment settings, and lighting. It had to be planned in detail and structured to achieve maximum results.

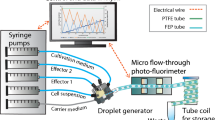

Experimental set up of Synechococcus HS-9 cultivation

The experiment is set up to cultivate Synechococcus HS-9 using RAPBR-Bs, as shown in Fig. 4. The experimental setup consists of (1) outlets; (2) energy meters; (3) 23 W LED light; (4) CPUs; (5) computers; (6) National Instruments (NI), (7) Power supplies; (8) Pressure gauge; (9) Flow meters; (10) Air filters; 11. Compressors; 12. Box panels for pH, DO, and ORP sensors: 13. Sensors for temperature, pH, CO2, DO, ORP, and light intensity; 14. Rectangular Airlift Photobioreactor using Baffles (RAPBR-Bs). All sensors used have been calibrated according to the standards in the research.

Rectangular Airlift Photobioreactor using Baffle (RAPBR-Bs) was modified from previous research, specifically by increasing the baffle width from 30 mm to 50 mm16. This was done so that the baffle functioned optimally to inhibit the movement of bubbles, thereby extending the residence time of the bubbles and CO₂ in the RAPBR-Bs. Baffles also broke large bubbles into smaller bubbles due to turbulence. This had really helped Synechococcus HS-9, which had a small cell size (0.9–2.5 μm) in absorbing CO₂ to carry out the photosynthesis process. Apart from that, the shape of the sparger changed from a tube sparger to a mushroom sparger. This was done because mushroom spargers could produce smaller bubbles compared to tube spargers.

Cultivation of Synechococcus HS-9 procedures

The cultivation procedures for Synechococcus HS-9 included compiling an experimental setup that had already been sterilized. The next stage was the inoculation process, that is, inserting Synechococcus HS-9 inoculum and NPK medium 80 ppm (nitrogen (N), phosphoric acid (P2O5), Potassium (K2O) and other micronutrients) into the RAPBR-Bs at a volume of 25 L and a ratio of 1:3.5 v/v. Thereafter, air flow entering the RAPBR-Bs, which utilized airflow from the compressor (0.04% CO2) was set at 2 LPM using a flowmeter with a measuring instrument accuracy of 0.5 LPM at a pressure of 2 bar. The selection of an inlet air flow of 2 LPM had been based on trial and error as well as the results of previous research, which indicated that the Synechococcus HS-9 cultivation process could not be carried out if the inlet air flow had been too high or too low. This caused cell damage, inhibited growth, and reduced the biomass productivity of Synechococcus HS-9.

Lighting using an LED lamp with a light intensity of 300–450 µmol m− 2s− 1 was then provided. The distance between the lamp and RAPBR-Bs was 30 cm. Optimal light intensity was very important in the growth process of microalgae to carry out the photosynthesis process. The lighting process for cultivating Synechococcus HS-9 involved 12 h of light and 12 h of darkness, utilizing a 23-watt white LED lamp19. White LED lights had a wavelength between 380 and 760 nm20,21. Cyanobacteria, including Synechococcus HS-9, generally absorbed light wavelengths between 380 and 780 nm22,23. The ability of cyanobacteria to absorb light was greatly influenced by the composition of photosynthetic pigments in the cells. Cyanobacteria cells contained chlorophyll a and phycobilin, which were capable of absorbing photon energy at wavelengths of 430–663 nm24.

Cultivation was conducted until Synechococcus HS-9 reached the end of the exponential phase or entered the stationary phase. The growth process of Synechococcus HS-9 was identified using dry biomass weight by drying the pellets in an Eppendorf tube using four 5-Watt incandescent lamps for a period of about 4–5 h at 38–40 °C. The growth process of Synechococcus HS-9 can also be known through the growth curve by measuring optical density (OD) for 14 days using a UV-VIS spectrophotometer with a measuring instrument accuracy of 0.001 Å.

The final process involved weighing the biomass produced from Synechococcus HS-9 cultivation. In addition to that, other important parameters were measured during the Synechococcus HS-9 cultivation process, namely temperature (T), light intensity (I), pH, CO2, dissolved oxygen (DO), and oxidation–reduction potential (ORP). These parameters are physico-chemical parameters that influence the growth process of Synechococcus HS-9 during the cultivation process. These parameters were measured using sensors connected to national instruments that recorded data every second during cultivation. The parameters were optimal during the Synechococcus HS-9 cultivation process, ranging between 27 and 32 °C for T, pH 6–8, 439–325 µmol m− 2s− 1 under bright conditions and approximately 190–200 µmol m− 2s− 1 on average under dark conditions for I, 82–84 ppm for CO2, under 7 mg/l for DO, and 145–180 mg/l for ORP. The important parameters (T, I, pH, CO2, DO, and ORP) are fully described in our previous publication19.

Analysis methods

Bubble video data processing

The video data processing to determine bubble speed utilized imageJ and PIVlab (Particle Tracking Velocimetry) applications, which are open-source toolboxes from MATLAB. PIVlab is a computational tool that detects circular image or video-based fluid movements using the Gaussian mask method25,26,27. Setting the video background to black aims reducing noise which interferes with image accuracy in detecting bubbles27.

Hydrodynamics and mass transfer data processing

The flow diagram for processing measurement data for mass transfer process analysis is shown in Fig. 5. The sequence is interconnected to obtain measured values.

The following stages show the processing of measurement data.

-

(a)

Knowing the area and number of bubbles using ImageJ.

-

(b)

Determining the original diameter from the image processing results using the circle area Eq. (1)28.

-

(a)

Determining the speed based on the PIVLab program.

-

(b)

Determining the Reynolds number to examine the character of water flow and bubbles based on Eqs. (2 and 3)29.

-

(c)

Determining the Eotvos number to examine the character of water flow and bubbles as well as predict the shape of the bubbles based on Eq. (4)30.

-

(e)

Determining the Weber number to examine the characteristics of bubble formation. This number can be known based on the value of the Terminal Velocity variable from Eq. (6)28.

Therefore, the Weber equation can be known from Eq. (7)28.

-

(g)

Determining the value of the Schmidt number to examine the mass transfer occurring in RAPBR-Bs, the Schmidt number is known from Eq. (9)28.

Results and discussion

The research data were obtained from three analyses, namely hydrodynamic analysis, mass transfer analysis, and analysis of the relationship between hydrodynamic parameters and mass transfer on the growth of Synechococcus HS-9. This paper presents the results of a single, non-repeated experiment. The respective data are elaborated in the following section.

Analysis of hydrodynamics in the cultivation of Synechococcus HS-9

Hydrodynamic parameters such as dynamic bubble properties (bubble diameter and velocity), gas hold-up, and mass transfer are important parameters that influence microalgae growth in the photobioreactor. These parameters are important in determining the design and development of photobioreactors for the microalgae cultivation process. The hydrodynamic analysis processed the data by analyzing the diameter and speed of bubbles, non-dimensional numbers such as Reynolds (Re), Eotvos (Eo), Morton (Mo), and Weber (We) numbers were used as parameters in determining flow and bubble characteristics. Other non-dimensional numbers, such as the Sherwood number (Sh) and Schmidt number (Sc), were used to determine the characteristics of mass transfer in bubbles. This non-dimensional number analysis was used to determine the effectiveness of mass transfer in the photobioreactor. Other parameters discussed in hydrodynamic analysis included gas hold-up, bubble rise velocity, and gas superficial velocity. The data processing, results, and analysis are discussed in the following section.

Bubble diameter and velocity in RAPBR-Bs

The diameter and speed of the bubbles produced by the mushroom sparger in the RAPBR-Bs can be determined by processing the visual bubble data. Photos and videos were taken using a Fastec TS5 high-speed camera. The results of the bubble photo are presented in Fig. 6. The photos were then processed using ImageJ software to get the average value of the bubble diameter.

Information about the bubble size distribution can be used to determine the average bubble diameter. The average diameter is the main parameter used to investigate the bubble characteristics. The effect of airflow rate on the average bubble diameter is shown in Table S1 and Fig. 7. In general, the diameter of the bubbles produced by the mushroom sparger in the RAPBR-Bs at an inlet air flow rate of 1–5 LPM ranges from 400 to 1000 μm. This data shows that the higher the inlet airflow, the higher the bubble diameter. This is caused by the influence of the forces that work during the bubble formation process.

In general, eight forces influence the bubble formation process, namely momentum force (FM), pressure force (FP), buoyancy force (FB), shear lift force (FD), gravity force (Fg), inertia force (FI), surface tension (Fσ), and tensile force (FD). Among these forces, the dominant forces are surface tension and inertia forces, as shown in Eqs. (13) and (14)9.

Surface tension force(Fσ)28.

Inertia force (FI)28.

The surface tension force causes the resulting bubbles to remain attached to the inlet (sparger). This force is proportional to the surface tension force (σ) and the air inlet diameter of the sparger (DN). The higher the surface tension force, the larger the diameter of the bubbles produced31. Another factor, i.e., the inertia force, influenced by the bubble volume (VB) and the liquid flow rate (\(\:\frac{ds}{dt}\)), triggers the bubbles to leave the inlet area. In the initial bubble formation process, the inertia force is smaller than the surface tension force. This causes the bubbles to remain on the sparger surface walls. The bubble expands until the inertia force is greater than the surface tension force. Increasing the inflow air flow causes the bubbles to expand faster and their volume (VB) to become larger. Apart from this, the presence of a baffle in the middle of the RAPBR-Bs can affect the size and shape of the bubble. This is caused by friction or collision between the bubble and the baffle, which causes the size and shape of the bubble to change, and the bubble tends to get bigger.

Bubble videos were taken using a Fastec TS5 high-speed camera with 1000 fps so the movement of the bubbles could be observed. Bubble video processing took 20 frames to represent the bubble speed in RAPBR-Bs. For every 1 bubble frame, 3 points are taken, namely points X, Y and Z, as in Fig. 6, to analyze the average value of the bubble speed at each point. Figure 8 shows an image of bubble speed processing using PIV Lab-MATLAB.

Based on the bubble speed values obtained from the three points in each video, the average value and standard deviation of the bubble speed were calculated, as presented in Table S2. Meanwhile, the relationship between the inlet air flow rate and the bubble speed is presented in Figure 9. The data shows that the bubble velocity value increases linearly with an increase in inlet air flow rate. In this case, the bubble velocity value is always linear with the bubble size and the inlet airflow [32].

Non-dimensional bubble numbers in RAPBR-Bs

Non-dimensional number analysis was carried out to determine the characteristics of the shape, flow, and movement of bubbles. The results of data processing of the relationship between the numbers Re, Eo, and Mo are presented in Fig. 10.

Figure 10 shows that the values of Re and Eo are directly proportional to the inlet air flow rate and bubble size. This is caused by an increase in the inlet airflow, increasing the size and speed of the bubbles, so the values of the numbers Re and Eo also increase. The relationship with this value is in accordance with Eq. (4) which shows that the Re number uses a function of speed and bubble diameter. The Eo number uses a function of the bubble diameter as presented in Eq. (5). Figure 10 shows the Re number value ranging from 3.94 to 5.54 at an airflow rate of 1–5 LPM. This value shows the Re number < 2000, included in the laminar flow category. The Re number, which is too small, is caused by the relatively small diameter and velocity values of the bubbles, 685.75–774.64 μm and 0.0058–0.0072 m/s respectively. Previous research shows that the value of the Re number obtained is also very small, namely ranging from 0 ≤ Re ≤ 1033, the value of the Re number (6—34)34, the value of the Re number (12—25)35, the value of the Re number (10—135)36, and the value of the Re number (0 < Re < 1500)37.

Moreover, Fig. 10 shows the constant Mo number value at an air inflow rate of 1–5 LPM. The Mo number is a constant, as it is only influenced by fluid properties, such as dynamic water viscosity, water density, and air density38. R Clift (1978) shows that the value of the Mo number is relatively the same (constant) with different working conditions39. The Mo number can also affect the size and shape of the bubble because the higher the Mo number, the greater the lifting force and inertia force required, which can affect the size and shape of the bubble.

Non-dimensional number values such as Re, Eo, and Mo obtained from the bubble diameter were used to determine the characteristics of the bubble shape. Based on the Re number value, bubble shapes can be grouped into 3 categories, namely spherical (Re < 300), ellipsoidal (300 < Re < 4000), and spherical cap (Re > 4000). In this case, the shape of the bubble obtained from the research corresponds to the value of the Re number, i.e., spherical. The bubble shapes can also be seen through the Clift diagram, as shown in Fig. 11. The spherical region is dominated by surface tension and viscosity and has a small bubble size, usually less than 1300 μm34. High surface tension tends to push bubbles towards a spherical shape, while bubbles in liquids with a high viscosity value can maintain their spherical shape with a larger size. Figure 11 shows the yellow dot, which is a sign of the bubble shape value based on the Re, Eo, and Mo number values from the inlet air flow rate of 1 to 5 LPM. The Clift diagram image shows that in the same fluid flow, increasing inlet airflow will affect the size and shape of the bubbles produced. The size and shape of the bubbles can also influence the growth of microalgae. The smaller and round shape of the bubbles is very suitable for the growth process of Synechococcus HS-9. This is due to the very small size of Synechococcus HS-9 (0.9–2.5 μm), making it easier for Synechococcus HS-9 to absorb evenly distributed CO2 through the aeration process with small, round-shaped bubbles. CO2 is really needed by Synechococcus HS-9 to carry out the photosynthesis process.

Clift diagram to determine the bubble shape point based on the Re, Eo, and Mo numbers39.

Figure 12 shows the relationship between bubble size, terminal velocity, and Weber number. In this case, the value of the We number increases along with the increase in the inlet air discharge value. The value of the We number was obtained by comparing the bubble inertia force and the water surface force. The larger the bubble’s diameter, the greater the value of the inertial force generated against the surface tension of the water. This is caused by the higher terminal velocity (UT) value due to the increase in bubble size as a function of UT.

Gas hold-up

Figure 13 shows the relationship between the inlet air discharge and gas hold-up (Ɛg), bubble rise velocity (Ub), and superficial gas velocity (Ugr). This data shows that the higher the inlet airflow, the higher the gas hold-up and bubble rise velocity. In this case, with an increase of inlet airflow ranging from 1 to 5 LPM, the gas hold-up and bubble rise velocity values increase linearly from 0.0048 to 0.0143 (non-dimensional) and from 0.0875 to 0.1472 m/s. Aziz Sadeg (2017) identified that with increasing inlet airflow, the gas hold-up and bubble rise velocity increase, and the bubble rise time decreases40. David Kuan (2013) shows that gas hold-up increases linearly with airflow rate41. The higher the gas hold-up value, the higher the driving force for the fluid circulation process, so the driving force of mass transfer increases. Figure 13 shows that the higher the gas hold-up value, the higher the gas superficial velocity value. The gas hold-up value is linearly proportional to the superficial gas velocity and has been widely summarized in several literature sources42,43,44,45.

Mass transfer analysis of Synechococcus HS-9 cultivation process

Data processing of non-dimensional numbers such as the Sherwood number (Sh) and Schmidt number (Sc) was used to determine mass transfer characteristics in bubbles. Analysis of Sh and Sc numbers was also used to determine the effectiveness of mass transfer in RAPBR-Bs. The mass transfer process is closely related to the diffusivity process. The mass transfer coefficient value can be known by determining the diffusivity value. The equation for the diffusivity value of oxygen (O2) and CO2 gases (Wilke Chang Equation) is shown in Eq. (15).

From this equation, the average values of the diffusivity of O2 and CO2 gas were 0.002 m2/s and 0.005 m2/s, respectively.

Equations of the values of Re, Sc, and Sh numbers are presented in Eqs. (3), (16), and (17)

.

The relationship between the bubble diameter and the Re, Sc, and Sh numbers is shown in Fig. 14. The figure shows that the value of the Sh number increases as the Re number increases. This is caused by an increase in bubble size along with an increase in inlet airflow. Based on Eq. (18), the Re number is a function of the Sh number, it is expressed as the ratio of the speed of mass transfer by convection to the diffusivity of mass transfer. The value of the Sh number, namely 2.00024–2.00032, corresponds to an increase in the intake airflow of 1–5 LPM. Even though the changes are small, the influence of the bubble’s movement can affect the bubble’s ability to transfer mass. Meanwhile, the Sc number value is constant at 0.00022 at an inlet air flow rate of 1–5 LPM, as presented in Fig. 14. The Sc number is only influenced by fluid properties such as dynamic water viscosity, water density, and air diffusivity values. R Clift (1978) shows that the value of the Sc number is constant at 0.7 when the Re number increases by 20 and 10039.

After obtaining the CO2, O2 diffusivity values, Sh and Sc numbers, then the mass transfer coefficient (kL) and mass transfer rate (J) values are calculated. The mass transfer coefficient equation (kL) is presented in Eq. (18).

\(\:{D}_{{O}_{2}}\) is the diffusivity of O2 gas, Ub is the bubble rise velocity, and dB is the bubble diameter. Table 1 and Figure S1 show the relationship between bubble diameter and mass transfer coefficient (kL). The larger the dB size, the higher the kL value. This is because the increasing bubble rise velocity (Ub) will increase the gas superficial velocity (Ugr) at an inlet airflow of 1–5 LPM. The higher Ugr value causes the stirring process in RAPBR-Bs to be better and the mass transfer process from the gas to the liquid phase to be higher. Apart from this, the increase in Ugr causes the aeration air pressure inside the RAPBR-Bs to become higher. This causes the resistance between the gas and liquid interface to become smaller, so the mass transfer process from the gas phase to the liquid phase becomes easier. Therefore, the value of the mass transfer coefficient (kL) will increase along with increasing gas superficial velocity (Ugr). This is in line with Ce Wei, et al., (2014), stating that the higher the superficial gas velocity value, the higher the mass transfer coefficient value. Meanwhile, Aastha Ozha., et al., (2016) and Basar Uyar, et al., (2024) show that the higher the superficial gas velocity, the higher the mass transfer and mass transfer coefficient46,47. Hydrodynamic analysis up to this part (mass transfer coefficient values) has not used microalgae culture.

Another important parameter is the volumetric mass transfer coefficient (kLa). Determination of the volumetric mass transfer coefficient value in the photobioreactor is presented in Eq. (19).

The volumetric mass transfer coefficient uses a function of time to change, so the kLa value for oxygen can be determined using Eq. (20)47.

Where C* is the DO saturation concentration at an average temperature of 30 °C, C0 is the DO concentration at time t0, and CL is the DO concentration at time t. Meanwhile, the value of the volumetric mass transfer coefficient (kLa) is determined for carbon dioxide, as presented in Eq. (21) using a relativity approach48,49.

Research on Synechococcus HS-9 cultivation was carried out for 14 days. The intake airflow used was 2 LPM and the average temperature was 30℃. Table 2 shows the volumetric mass transfer coefficient (kLa) values of O2 and CO2 recorded during the cultivation process of Synechococcus HS-9, with the standard deviation of kLa O2 and CO2 being 0.0049 and 0.0042. It shows that the DO(CL) concentration was quite high from the first day (t1) to the sixth day (t6) of the cultivation process. This causes the kLa O2 and CO2 values to be undefined on days t1 to t6 because the CL value is higher than the DO saturation concentration value (C*). The kLa values of O2 and CO2 begun to be detected on the seventh day (t7) and the graphic trend continued to decrease from the eighth day (t8) to the last day of the cultivation process (t14). This is because the DO concentration continues to decrease from t1 to t14, which shows that the mass transfer process in RAPBR-Bs during the Synechococcus HS-9 cultivation process is going well. The kLa values can also decrease due to an increase in the optical density (OD) value of microalgae, a decrease in interfacial area caused by a decrease in the number and size of bubbles, and a decrease in gas holdup during microalgae growth46. Other research indicates that the decrease in kLa values is due to high biomass content during the cultivation process, which reduces light penetration into the microalgae culture and photosynthetic CO2 fixation50. This is in accordance with the results of this research, which show that the OD and dry biomass values increased until the end of the cultivation process, paralleling the continued decrease in light intensity values19.

Another parameter analyzed is the volumetric mass transfer rate (J). The value of the volumetric mass transfer rate (J) can be determined using Eq. (22)28. The volumetric mass transfer coefficient value is obtained from the average value during the cultivation process. The average value of the volumetric mass transfer coefficient (kLa) of O2 is 0.114/s.

Table S3 shows data on the volumetric mass transfer rate during the cultivation of Synechococcus HS-9. These data show that the volumetric mass transfer rate experienced a positive trend, which is continuing to increase during the cultivation process. The higher the rate of volumetric mass transfer in RAPBR-Bs during the cultivation of Synechococcus HS-9, the higher the contribution to the process of distributing CO2 into cells, this is effective in reducing or even eliminating O2 from RAPBR-Bs.

Relationship between hydrodynamic parameters and mass transfer on the growth of Synechococcus HS-9

The characteristics of hydrodynamic parameters and mass transfer which include bubble diameter and velocity, bubble rise velocity, gas hold-up, and volumetric mass transfer coefficient are important parameters in the cultivation of Synechococcus HS-9. These parameters can influence the growth rate and productivity of Synechococcus HS-9 biomass during cultivation. Research on cultivating Synechococcus HS-9 to produce biomass used Rectangular Airlift Photobioreactor using Baffle (RAPBR-Bs). RAPBR-Bs has a content volume (medium and Synechococcus HS-9) of 25 L and is equipped with a mushroom sparger which functions as an aeration and bubble generator. In addition, RAPBR-Bs have a baffle that inhibits the movement of bubbles, thereby extending the residence time of the bubbles and CO2 in the RAPBR-Bs. Baffles can also break up large bubbles into smaller ones due to turbulence. The cultivation process was carried out for 14 days with a constant intake airflow of 2 LPM, air pressure of 2 bar, and room temperature of 27–32℃.

The cultivation of Synechococcus HS-9 is relatively new, carried out on a large scale and using RAPBR-Bs. Previous studies have shown that Synechococcus HS-9 cannot be cultivated under conditions with too high or too low intake airflow. Too high intake airflow increases superficial gas velocity, causing high turbulence in the RAPBR-Bs and increasing the shear stress on Synechococcus HS-9 cells. This can potentially damage cells and inhibit the growth of Synechococcus HS-932. Meanwhile, too low airflow can cause a decrease in bubble rise velocity and gas hold-up which results in a decrease in the mass transfer process. This causes the distribution of CO2, nutrients, and light in RAPBR-Bs which are important parameters in the Synechococcus HS-9 photosynthesis to decrease, thereby reducing the growth rate and biomass productivity of Synechococcus HS-9. Therefore, the intake airflow (aeration process) as a mixing process parameter in RAPBR-Bs is an important component in the growth of Synechococcus HS-9. The aeration process can increase productivity, control the frequency of cell light/dark rotation, maintain a uniform temperature, avoid cell settling, supply CO2 into the medium (nutrients), and remove O2 from the medium by increasing the mass transfer rate51. Another thing that must be considered is the increase in Synechococcus HS-9 cell density, which can affect the mixing (aeration) and mass transfer processes. The higher density of Synechococcus HS-9 cells in RAPBR-Bs can affect the uneven distribution of light/dark cell rotation and the uneven supply of nutrients and CO2, which can inhibit the rate of mass transfer. Therefore, this research must use an optimal aeration process.

Another factor that can influence the mixing process that occurs in RAPBR-Bs is the increasing density of microalgae cells, which is directly proportional to the increasing viscosity of the culture medium. High media viscosity can make it more difficult for liquids to mix homogeneously. This is because the internal friction force in the fluid increases, so it requires greater energy to produce turbulent flow. This condition can affect the hydrodynamic processes that occur in RAPBR-Bs, causing the mixing process to be not optimal, namely inhibiting the movement of air bubbles so that the distribution of nutrients, CO2, and light to carry out photosynthetic and metabolic activities is uneven, which can cause the growth of Synechococcus HS-9 to be not optimal. High viscosity can also reduce the mass transfer coefficient between the medium and Synechococcus HS-9 cells, which can inhibit the rate of absorption of nutrients and gases by the cells.

The results of this study show that the cultivation of Synechococcus HS-9 using RAPBR-Bs experienced significant growth because the aeration process (mixing process) was optimal, as shown in Fig. 16. The mixing process is very important to ensure homogeneous growth in all areas within the RAPBR-Bs. An optimal aeration process can increase the mass transfer coefficient, so the mass transfer capacity in the RAPBR-Bs increased. This causes more CO2 to dissolve in the medium to increase biomass productivity. Installation of baffles in the middle of RAPBR-Bs affected the mass transfer process. The turbulence process with baffles caused the bubbles to burst and increased the number of bubbles. This caused the turbulence intensity to increase, reduced the bubble size, and increased the amount of gas in the bubble. This phenomenon holds the potential to improve the mass transfer properties of RAPBR-Bs. Table S4 shows the hydrodynamic parameters and mass transfer during the cultivation process of Synechococcus HS-9 compared with other studies. The volumetric mass transfer coefficient value in the cultivation of Synechococcus HS-9 using RAPBR-Bs was higher compared to photobioreactors from other studies. The results show that the hydrodynamic and mass transfer properties of these RAPBR-Bs are more efficient than those reported for other PBRs. This finding suggests the potential for using RAPBR-Bs with larger volumes than previously proposed.

Cultivation of Synechococcus HS-9

The cultivation of Synechococcus HS-9 used RAPBR-Bs with a volume of 25 L to produce biomass. The cultivation was carried out for 14 days using 80 ppm NPK medium and a 2-LPM aeration speed at a bar pressure of 2, room temperature of 27–32 °C, culture pH of 8–6, and light intensity of 300–450 µmol m− 2s− 1. Cultivation was conducted at the Plant Taxonomy Laboratory, Department of Biology and Makara Energy Labeling Laboratory (Integrated Laboratory Research Center/ILRC) at the University of Indonesia.

Cultivation ended when the growth of Synechococcus HS-9 reached the end of the exponential phase towards the stationary phase. During the exponential phase, Synechococcus HS-9 rapidly increases the number of cells, which is characterized by cell division, rapid biomass growth, and balanced growth between the increased biomass and nutrient supply in RAPBR-Bs52. During the stationary phase, the growth rate of Synechococcus HS-9 was greatly influenced by the medium, pH, nutrient content, humidity, and temperature. Synechococcus HS-9 was harvested at the end of the exponential growth phase, which was marked by a decrease in the growth curve. This phase showed that the cell structure was still in a normal condition, and there was a balance between the nutrient content in the cells and that in the medium53. In addition, Synechococcus HS-9 was under optimum conditions, with high fat and protein contents; therefore, they can be used as raw materials for biodiesel and as inoculum for the subsequent cultivation process54.

During cultivation, macroscopic observations of the starter and culture of Synechococcus HS-9 were performed by comparing the color with that of the Fable-Castell color standard. Figure 15 shows the macroscopic appearance of the Synechococcus HS-9 starter culture in moss green. Figure S2 shows the macroscopic appearance of the Synechococcus HS-9 culture during the cultivation process from the first day (t0) to days (t14) of the cultivation.

The results of macroscopic observations, as shown in Figure. S2, indicated a color change of the Synechococcus HS-9 culture in the RAPBR-Bs during cultivation. The color changes observed at t0 and t1 were light green, t2 was true green, t3 was grass green, t4–t9 were apple green, t10 was moss green, t11 and t14 were leaf green, and t12 and t13 were moss green. The culture results during cultivation showed a significant color change from predominantly light green with a fainter green color to moss green with a more intense green color. The color changes from fainter green at t1 to darker green at t10, t12, and t13 indicated a higher density of Synechococcus HS-9 cells. However, the Synechococcus HS-9 cells at t10 were still in the exponential growth phase. The Synechococcus HS-9 culture showed a slight decrease in the green color from moss green to leaf green at t11 and t14. This showed a decrease in the density of the Synechococcus HS-9 cells and a stationary growth phase towards the death phase. Other important parameters used to determine growth during the cultivation process of Synechococcus HS-9 included dry biomass weight. It was measured to determine the density of Synechococcus HS-9 cells in the RAPBR-Bs. The biomass weight was used as an indicator of harvesting time, as shown in the growth curve of Synechococcus HS-9 (Fig. 16). Dry biomass weight was obtained by drying the pellets in an Eppendorf tube using four 5-Watt incandescent lamps for 4–5 h at 38–40 °C. The higher the dry biomass weight, the higher the Synechococcus HS-9 cell density. This showed that Synechococcus HS-9 was growing well.

Figure 16 shows the dry biomass weight on the growth curve of Synechococcus HS-9 during cultivation. The first and second days (t0–t2) comprised of the lag phase, and the third to tenth days (t3–t10) comprised of the exponential phase. The growth curve showed that the dry biomass weight values continued to increase from the beginning of cultivation (t0) to the tenth day (t10), with values of 4.17 × 10− 5 and 4.83 × 10− 4 gr/mL, respectively. The higher the dry biomass weight, the higher the cell density in the RAPBR-Bs. This indicates the important parameters affecting the growth of Synechococcus HS-9 under both fulfilled and adequate conditions. These parameters included room temperature, which was stable at 27–32 °C; pH 7–8 which was the optimum value for the cultivation of Synechococcus HS-9; and aeration for the even distribution of nutrients and CO2 in the RAPBR-Bs. Another important factor was the correct ratio of inoculum to medium during inoculation, so that the availability of nutrients and the number of Synechococcus HS-9 cells during cultivation were sufficient. The ratio of inoculum to medium used was 1:3.5.

The degree of acidity (pH) greatly influences cell structure and metabolic processes. Low pH changes the solubility of nutrients in the medium, disrupting the absorption of nutrients by metabolic processes55,56. One factor affecting the pH is the formation of bicarbonate compounds (HCO3−) and carbonic acid, which originate from the reaction between the CO2 dissolved in the medium and water. HCO3− is absorbed by cells for growth activity and causes the pH value to decrease. Synechococcus HS-9 cultivation resulted in relatively stable pH values ranging from 7 to 8 to. This was due to the increased number of Synechococcus HS-9 cells in the RAPBR-Bs, which tended to increase the pH value and was relatively stable during cultivation. Stable pH facilitates the absorption of CO2 in the form of HCO3− for photosynthesis and cell growth (Fig. 17).

During the cultivation of Synechococcus HS-9, there were two exponential phases: the first phase (t0–t10) and the second (t13). Cultivation at t13 was optimum for the growth process (the second exponential phase) of Synechococcus HS-9, with the dry biomass weight of 5.1 × 10−4 g/ml. This is because the growth curve decreased twice, at t11 and t14. The dry biomass weight at t11 and t14 was 4.58 × 10− 4 g/ml and 4.72 × 10−4 g/ml, respectively. Therefore, t14 was the right time for harvesting because the death phase began, and the exponential phase had just ended. The death phase was marked by an increase in the rate of cell death, which was higher than the rate of cell growth. Therefore, the weight of the dry biomass also decreased. This was influenced by the reduced availability of nutrients, resulting in competition among Synechococcus HS-9 cells for nutrients. Other influencing factors included reduced CO2 availability, changes in the media pH, decreased Synechococcus HS-9 cell metabolism due to old age, and low light penetration into the RAPBR-Bs due to a high cell density52. The Synechococcus HS-9 biomass weight obtained during cultivation was 3.226 g as shown in Figure. 17.

CO2 fixation of Synechococcus HS-9 cultivation

CO₂ fixation is an estimate from the perspective of CO₂ consumption by microalgae during the cultivation process. Microalgae absorb CO2 to carry out the photosynthesis process with the help of light and water, which can produce oxygen and organic compounds to increase growth and biomass production. CO₂ consumption rate (RCO₂, mg/L/day) can be calculated using Eq. (23)57,58,59:

PB is biomass productivity (mg/L/day), which is calculated using Eq. 24; Xn is the biomass concentration (mg/L) during the cultivation time, and X₀ is the biomass concentration at the initial stage of cultivation42:

The research results indicated that the average RCO2 carried out by Synechococcus HS-9 during the cultivation process, which utilized airflow from the compressor (0.04% CO2), was 76 mg/L/day. These results exceeded the research conducted by Chen et al., (2021), which reported an average RCO₂ of 55 mg/L/day for 0.04% CO₂, 67 mg/L/day for 6% CO₂, and 16 mg/L/day for 20% CO₂58. Other research showed high average RCO₂ values using 0.04% CO₂, namely 239 mg/L/day57 and 141.1 mg/L/day59. These findings show that Synechococcus HS-9 and other strain could be used for CO2 fixation as an alternative way to capture and reduce CO2, which is becoming more and more of a problem every year. However, this related research must continue to be improved and developed in the future.

CO₂ fixation greatly influenced the growth process of microalgae; among other things, it increased the efficiency of utilization of nutrients such as phosphorus and nitrogen. Sufficient CO₂ availability helped microalgae in forming organic compounds such as lipids, carbohydrates, and proteins. Apart from that, CO₂ fixation affected the pH conditions of the medium because CO₂ reacted with water to form carbonic acid, which lowered the pH. Lowering the pH proved to be beneficial under certain conditions, but if it became too drastic, it inhibited the growth of microalgae19,60. Therefore, it was very important to regulate optimal CO₂ levels according to the characteristics of the microalgae strain.

Challenges and recommendation for biomass production of Synechococcus HS-9

Synechococcus HS-9 is a type of monoculture microalgae strain that is very sensitive to direct contact with outside air. This can cause Synechococcus HS-9 to be contaminated. Therefore, one of the challenges in this research is that everything needed to support this research, such as researchers, rooms, experimental setup equipment, and other supporting materials, must be kept in a sterile condition to avoid contamination. This requires a lot of time and effort. In addition, Synechococcus HS-9 is also very sensitive to changes in temperature, pH, salinity, and nutrient concentration. Therefore, another challenge is preparing a photobioreactor design that pays attention to and considers physicochemical parameters, hydrodynamic parameters, and mass transfer, which can influence the growth and productivity of Synechococcus HS-9 biomass. This research uses RAPBR-Bs, which are capable of producing better hydrodynamic parameters and mass transfer so that the growth and productivity of Synechococcus HS-9 biomass is also better compared to other photobioreactors. However, the results of this research are still not perfect and optimal if the cultivation process is carried out with a larger capacity. Therefore, this research must continue to be carried out and developed in the future.

Based on the challenges that have been described, research and development on the Synechococcus HS-9 strain must continue to be carried out so that it can be resistant to contaminants so that cultivation processes can be carried out with greater capacity using both closed and open systems. Apart from that, it is necessary to carry out a simulation process using computational fluid dynamics (CFD) with three phases (microalgae, medium, and air) with various types of baffles and sparger configuration during the cultivation process using RAPBR-Bs. This can help reduce the experimental process of trial and error, which takes a long time, and can also help determine the optimum parameters that influence the growth and productivity of Synechococcus HS-9 biomass using various cultivation methods both on a small and large scale.

Conclusion

This paper presents the results of a single, non-repeated experiment. The research results show that hydrodynamic parameters such as bubble properties, namely bubble velocity, bubble diameter, non-dimensional number (Re, Eo, Mo, We), superficial gas velocity, bubble rise velocity, gas hold-up, and mass transfer process (kLa O2; kLa CO2) in RAPBR-Bs, were influential and can increase the growth of Synechococcus HS-9 during cultivation. The hydrodynamic and mass transfer processes were optimal in RAPBR-Bs during the cultivation process. The mixing step is critical to ensuring homogenous growth in all areas of the RAPBR-Bs. An appropriate aeration method can increase the mass transfer coefficient, hence increasing the mass transfer capacity in the RAPBR-Bs. This can cause more CO2 to dissolve in the medium, increasing biomass production. The installation of baffles in the center of RAPBR-Bs influences the mass transfer process. The turbulence generated by the baffles caused the bubbles to break, increasing the quantity of bubbles. This raised the turbulence severity, decreased the bubble size, and increased the volume of gas in the bubble. This effect could improve the mass transfer capabilities of RAPBR-Bs. The data obtained can be used as a reference for further research. The results show that the hydrodynamic and mass transfer properties of these RAPBR-Bs are more efficient than those reported for other PBRs. This finding suggests the potential for using RAPBR-Bs with larger volumes than previously proposed.

The optimum condition for the growth process of Synechococcus HS-9 during cultivation was at day 13, which reached the late exponential phase. The higher the dry biomass weight, the higher the cell density in the RAPBR-Bs. This indicated the important parameters affecting the growth of Synechococcus HS-9 under both fulfilled and adequate conditions. These parameters included room temperature, which was stable at 27–32 °C; pH 7–8, which was the optimum value for the cultivation of Synechococcus HS-9; and aeration for the even distribution of nutrients and CO2 in the RAPBR-Bs. The Synechococcus HS-9 biomass weight obtained during cultivation was 3.226 g.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- A:

-

Bubble diameter (µm)

- dB :

-

Bubble diameter (µm)

- dBS :

-

Sauter mean bubble diameter (µm)

- di :

-

Bubble diameter i (µm)

- dp :

-

Bubble diameter (µm)

- de :

-

Bubble equivalent diameter (µm)

- C*:

-

Saturation concentration (mg/m3)

- CL :

-

Concentration of liquid (mg/m3)

- C0 :

-

Initial concentration (mg/m3)

- D:

-

gas diffusivity (m2/s)

- Dg :

-

Gas diffusivity (m2/s)

- Eo :

-

Eotvos number (non-dimensional numbers)

- FB :

-

Buoyancy force (N)

- FM :

-

Momentum Flux (N)

- Fσ :

-

Surface tension (N)

- FI :

-

Inertial force (N)

- FD:

-

Lift force (N)

- g:

-

Gravitational force (m/s2)

- J:

-

Mass transfer rate (mg/m2s)

- KL :

-

Mass transfer coefficient (m/s)

- \(K_{L}{\alpha }\) :

-

Volumetric mass transfer coefficient (s−1)

- Mo :

-

Morton number (non-dimensional numbers)

- Ml :

-

Molecule weight of liquid (m3/mol)

- ni :

-

Number of bubble sizes i (non-dimensional numbers)

- Re :

-

Reynolds number (non-dimensional numbers)

- r:

-

Bubble radius (m)

- Sc:

-

Schmidt number (non-dimensional numbers)

- Sh:

-

Sherwood number (non-dimensional numbers)

- UT :

-

Terminal Velocity (m/s)

- Ub :

-

Bubble rise velocity (m/s)

- Ugr :

-

Gas superficial velocity m/s ()

- t:

-

Time (day)

- t0 :

-

initial time (day)

- T:

-

Temperature (°C)

- V:

-

Flow rate (m/s)

- \({\stackrel{\sim}{V}}_{g}\) :

-

Molar volume of gas (m3/mol)

- V:

-

Average velocity (m/s)

- We :

-

Weber number (non-dimensional numbers)

- ρl :

-

Liquid density (kg/m3)

- ρg :

-

Gas density (kg/m3)

- µ:

-

Liquid viscosity (Pa s)

- σ:

-

Water surface tension (N/m)

- Φ:

-

Solubility parameters

References

Rahman, A. & Prihantini, N. B. & Nasruddin. Fatty acid of microalgae as a potential feedstock for biodiesel production in Indonesia. in AIP Conference Proceedings(AIP Publishing LLC, 2019).

Rahman, A., Prihantini, N. B. & Nasruddin Biomass production and synthesis of biodiesel from microalgae Synechococcus HS-9 (Cyanobacteria) cultivated using bubble column photobioreactors. Evergr. Jt. J. Nov Carbon Resour. Green. Asia Strateg. 7(4), 564–570 (2020).

Rastogi, R. P. et al. Algal green Energy–R&D and technological perspectives for biodiesel production. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 82, 2946–2969 (2018).

Muhammad, H. I. et al. The application of poly-dispersed flow on rectangular airlift photobioreactor mixing performance. Evergreen 7(4), 571–579 (2020).

Acién, F. et al. Photobioreactors for the Production of Microalgae, in Microalgae-based Biofuels and Bioproducts 1–44 (Elsevier, 2017).

Orlando, A. M. et al. Effects of aeration intensity as agitation in simple photobioreactors on leptolyngbya (cyanobacteria) growth as biofuel feedstock. in E3S Web of Conferences(EDP Sciences, 2018).

Rahman, A. et al. Life cycle engineering (LCE) study for Synechococcus HS-9 biomass production as potential Raw material for a third generation biodiesel production. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 60, 103484 (2023).

Zheng, Q. et al. Critical review of strategies for CO2 delivery to large-scale microalgae cultures. Chin. J. Chem. Eng. 26(11), 2219–2228 (2018).

Juwana, W. E. et al. Hydrodynamic characteristics of the microbubble dissolution in liquid using orifice type microbubble generator. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 141, 436–448 (2019).

Deendarlianto, D. et al. The implementation of a developed microbubble generator on the aerobic wastewater treatment. Int. J. Technol. 6(6), 924–930 (2015).

Pires, J. C., Alvim-Ferraz, M. C. & Martins, F. G. Photobioreactor design for microalgae production through computational fluid dynamics: a review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 79, 248–254 (2017).

Reyna-Velarde, R. et al. Hydrodynamic and mass transfer characterization of a flat-panel airlift photobioreactor with high light path. Chem. Eng. Process. 49(1), 97–103 (2010).

Jones, S. M. & Harrison, S. T. Aeration energy requirements for lipid production by scenedesmus sin airlift bioreactors. Algal Res. 5, 249–257 (2014).

Zhao, L. et al. Investigate the cross-flow flat‐plate photobioreactor for high‐density culture of microalgae. Asia-Pacific J. Chem. Eng. 13(5), e2247 (2018).

Singh, N. K., Naira, V. R. & Maiti, S. K. Production of biodiesel by autotrophic chlorella pyrenoidosa in a sintered disc lab scale bubble column photobioreactor under natural sunlight. Prep. Biochem. Biotechnol. 49(3), 255–269 (2019).

Rahman, A. et al. Cultivation of Synechococcus HS-9 in a novel rectangular bubble column photobioreactor with horizontal baffle. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 27, 101264 (2021).

Shadpour, S. et al. Chlorella vulgaris cultivation using triangular external loop airlift photobioreactor: hydrodynamic and mass transfer studies. J. Renew. Energy Environ. 9(1), 93–105 (2022).

Zarei, Z. et al. Effect of hydrodynamic parameters on hydrogen production by Anabaena sp. in an internal-loop airlift photobioreactor. Braz. J. Chem. Eng. 40(2), 379–388 (2023).

Rahman, A. et al. Multi-objective genetic algorithm optimization of energy efficiency and biomass concentration of Synechococcus HS-9 cultivation for third-generation biodiesel feedstock. Case Stud. Chem. Environ. Eng. 9, 100614 (2024).

Baidya, A. et al. Effect of different wavelengths of LED light on the growth, chlorophyll, β-carotene content and proximate composition of chlorella ellipsoidea. Heliyon 7(12) (2021).

Sena, S. et al. Light emitting diode (LED) lights for the improvement of plant performance and production: A comprehensive review. Curr. Res. Biotechnol. 7, 100184 (2024).

Hopkins, W. G. Introduction To Plant Physiology (Wiley, 2009).

Kupriyanova, E. V. et al. The freshwater Cyanobacterium Synechococcus elongatus PCC 7942 does not require an active external carbonic anhydrase. Plants 13(16), 2323 (2024).

Matsuo, T. et al. Archaean green-light environments drove the evolution of cyanobacteria’s light-harvesting system. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 1–14 (2025).

Lin, D., Grundmann, J. & Eltner, A. Evaluating image tracking approaches for surface velocimetry with thermal tracers. Water Resour. Res. 55(4), 3122–3136 (2019).

Thielicke, W. & Stamhuis, E. PIVlab–towards user-friendly, affordable and accurate digital particle image velocimetry in MATLAB. J. Open. Res. Softw., 2(1) (2014).

Patalano, A., García, C. M. & Rodríguez, A. Rectification of image velocity results (RIVeR): A simple and user-friendly toolbox for large scale water surface particle image velocimetry (PIV) and particle tracking velocimetry (PTV). Comput. Geosci. 109, 323–330 (2017).

Kadic, E. & Heindel, T. J. An Introduction To Bioreactor Hydrodynamics and gas-liquid Mass Transfer (Wiley, 2014).

Saldana, M. et al. The Reynolds number: A journey from its origin to modern applications.Fluids 9, 299 (2024).

Neviani, M., Bagnerini & Paladino, O. Gas bubble dynamics in airlift photo-bioreactors for microalgae cultivation by level set methods. Fuel 292, 120402 (2021).

Zahedi, P. et al. Influence of fluid properties on bubble formation, detachment, rising and collapse; investigation using volume of fluid method. Korean J. Chem. Eng. 31(8), 1349–1361 (2014).

Dhar, L. et al. Bubble characteristics from injected air sheet through slots in a water cross-flow. Int. J. Multiph. Flow. 142, 103693 (2021).

Besagni, G. et al. The dual effect of viscosity on bubble column hydrodynamics. Chem. Eng. Sci. 158, 509–538 (2017).

Amaya-Bower, L. & Lee, T. Single bubble rising dynamics for moderate Reynolds number using lattice Boltzmann method. Comput. Fluids. 39(7), 1191–1207 (2010).

Duque, J. L. R. & Lucumi, M. A. R. Hydrodynamic computational evaluation in solar tubular photobioreactors bends with different cross sections. CT&F-Ciencia, tecnología y futuro 4(4), 59–72 (2011).

Shu, S. et al. Multiscale multiphase phenomena in bubble column reactors: A review. Renew. Energy. 141, 613–631 (2019).

Haas, T. et al. A review of bubble dynamics in liquid metals. Metals 11(4), 664 (2021).

Besagni, G. & Inzoli, F. Comprehensive experimental investigation of counter-current bubble column hydrodynamics: holdup, flow regime transition, bubble size distributions and local flow properties. Chem. Eng. Sci. 146, 259–290 (2016).

Clift, R., Grace, J. R. & Weber, M. E. Bubbles, Drops, and Particles (Academic press, 1978).

Sadeghizadeh, A., Moghaddasi, L. & Rahimi, R. CO2 capture from air by chlorella vulgaris microalgae in an airlift photobioreactor. Bioresour. Technol. 243, 441–447 (2017).

Kuan, D. Growth Optimization of Synechococcus Elongatus PCC 7942 in Lab Flask and 2D Photobioreactor (University of British Columbia, 2013).

Fernandes, B. D. et al. Characterization of split cylinder airlift photobioreactors for efficient microalgae cultivation. Chem. Eng. Sci. 117, 445–454 (2014).

Esmaeili, A., Guy, C. & Chaouki, J. Local hydrodynamic parameters of bubble column reactors operating with non-Newtonian liquids: experiments and models development. AIChE J. 62(4), 1382–1396 (2016).

Ojha, A. & Al-Dahhan, M. Local gas holdup and bubble dynamics investigation during microalgae culturing in a split airlift photobioreactor. Chem. Eng. Sci. 175, 185–198 (2018).

Feng, D. et al. Bubble characterization and gas–liquid interfacial area in two phase gas–liquid system in bubble column at low Reynolds number and high temperature and pressure. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 144, 95–106 (2019).

Ojha, A. Advancing microalgae culturing via bubble dynamics, mass transfer, and dynamic growth investigations (2016).

Uyar, B., Ali, M. D. & Uyar, G. E. O. Design parameters comparison of bubble column, airlift and stirred tank photobioreactors for microalgae production. Bioprocess Biosyst. Eng. 1–15 (2024).

Jones, S. M., Louw, T. M. & Harrison, S. T. Energy consumption due to mixing and mass transfer in a wave photobioreactor. Algal Res. 24, 317–324 (2017).

Ndiaye, M., Gadoin, E. & Gentric, C. CO2 gas–liquid mass transfer and kLa estimation: numerical investigation in the context of airlift photobioreactor scale-up. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 133, 90–102 (2018).

Hoyos, E. G. et al. Innovative design and operational strategies to improve CO2 mass transfer during photosynthetic biogas upgrading. Bioresour. Technol. 391, 129955 (2024).

Katuwal, S. Designing and Development of a Photobioreactor for Optimizing the Growth of Micro Algae and Studying its Growth Parameters (South Dakota State University, 2017).

Madigan et al. Brock Biology of Microorganisms 13th edn 268–269 (Pearson Education, 2012).

Gozai-Alghamdi, S. A. et al. Photobiota of the tropical red sea: fatty acid profile analysis and nutritional quality assessments. Molecules 30(3), 621 (2025).

Ugurlu, A. & Oztuna, S. A comparative analysis study of alternative energy sources for automobiles. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy. 40(34), 11178–11188 (2015).

Magder, S., Magder, A. & Samoukovic, G. Intracellular pH regulation and the acid delusion. Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 99(6), 561–576 (2021).

Nurafifah, I. et al. The effect of acidic pH on growth kinetics, biomass productivity, and Prima-ry metabolite contents of Euglena Sp. Makara J. Sci. 27(2), 3 (2023).

Nayak, M., Karemore, A. & Sen, R. Performance evaluation of microalgae for concomitant wastewater bioremediation, CO2 biofixation and lipid biosynthesis for biodiesel application. Algal Res. 16, 216–223 (2016).

Chen, Y. & Xu, C. How to narrow the CO 2 gap from growth-optimal to flue gas levels by using microalgae for carbon capture and sustainable biomass production. J. Clean. Prod. 280, 124448 (2021).

Padhi, D. et al. Enhanced carbon dioxide biofixation and lipid production of chlorella sp. Using alkali absorber and strategic carbon dioxide supply. Bioenergy Res. 18(1), 1–14 (2025).

Padhi, D. et al. Microalgae-based flue gas CO2 sequestration for cleaner environment and biofuel feedstock production: A review. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 1–27 (2025).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Hibah Publikasi Terindeks Internasional (PUTI) Q1 from Directorates of Research and Development Universitas Indonesia to Nasruddin [grant number NKB-525/UN2.RST/HKP.05.00/2024] and supported by the Postdoctoral Scheme at Research Center for Sustainable Production System and Life Cycle Assessment, National Research and Innovation Agency (BRIN), Indonesia 2024- 2025.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Universitas Indonesia. This work was supported by the Hibah Publikasi Terindeks Internasional (PUTI) Q1 from Directorates of Research and Development Universitas Indonesia to Nasruddin [grant number NKB-525/UN2.RST/HKP.05.00/2024].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Arif Rahman: Investigation, Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing original draft preparation, Writing-review & editing. Nining Betawati Prihantini: Supervision, Methodology, Writing original draft preparation. M.A.M. Oktaufik: Supervision, Methodology, Writing original draft preparation. Ridho Irwansyah: Methodology, Writing original draft preparation. Muhammad Abdul Kholiq: Methodology, Writing original draft preparation. Alfred Kampira Levison: Writing original draft preparation. Lubi Rahadiyan: Writing original draft preparation. Muhammad Aziz: Methodology, Writing original draft preparation. Yoyon Wahyono: Writing original draft preparation, Writing-review & editing. Dita Ariyanti: Writing original draft preparation, Writing-review & editing. N Nasruddin: Conceptualization, Supervision, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Writing original draft preparation.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Rahman, A., Prihantini, N.B., Oktaufik, M.A.M. et al. Effect of hydrodynamics and mass transfer processes on biomass production of Synechococcus HS-9 cultivated using rectangular airlift photobioreactors with baffles. Sci Rep 15, 32070 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-13711-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-13711-y