Abstract

The special features of silver-capped iron nanoparticles, like their excellent ability to conduct heat, adjustable magnetism, and resistance to rust, make them highly sought after for industrial heat transfer uses. The medical and industrial fields are rapidly adopting a new technology that shows promise in areas such as electronics cooling, biomedical heating, solar thermal, and nanofluids. The flow of silver-capped iron nanoparticles through a Forchheimer medium with the CC effect is the subject of this work because of these applications. Additionally, thermal radiation and exponential heat sources are considered. The mixed convective situation improves the boundary. The governing equations of flow are reduced by employing similarity transformations from a PDE to an ODE. Utilizing a set of similar variables, the modeled problem will be converted into a set of ODEs. With RKF-45, the resulting set of ODEs will be solved. Through the graphs, the behaviours of many significant parameters will be examined and discussed in cases when these factors are \(\:Da=0.2\:to\:0.8,\:{K}_{p}=0.2\:to\:0.8,\:\varphi\:=0.01\:to\:0.02,\:\:Pr=40,Q=0.4\:to\:1,\:\:R=0.5\:to\:2\:\)and \(\:\lambda\:=0.2\:to\:0.8\), \(\:\xi\:=\text{0,2}\:to\:0.8.\) Velocity of the fluid is more controllebele in hybrid nanoparticles case then that of nanoparticles case. Rate of heat transfer is more influence by silver capped iron oxide nanoparticle when compared to silver nanoparticles. The temperature profile increases when \(\:Da\) improves. There is an improvement in the thermal boundary layer as well. Convective cooling diminishes with decreasing velocity, and thermal energy tends to build up, increasing the fluid’s temperature. Reduced flow further thickens the thermal boundary layer, which raises the temperature profile even more. For both silver and silver oxide nanoparticles Nusselt number increases when \(\:\lambda\:,\:Q,\:R,\:\varphi\:\) and \(\:Bi\) values grow. However, when \(\:Pr\) values rise, the reverse effect is seen. Silver nanoparticles and silver oxide nanoparticles, skin friction decreases as the \(\:Fr,\:\varphi\:\) and \(\:Da\) parameters increase.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Small particles with at least one dimension inside the nanometre range are called nanoparticles. Materials have unique optical, electrical, chemical, and physical properties at this scale. Due to the viscosity, thermal conductivity and heat transfer coefficient of the base fluid such as water, ethylene glycol, or oil are all improved by nanoparticles. The potential of this research area to improve heat transfer system efficiency in a variety of engineering applications has generated a lot of interest1,2,3,4,5,6,7. Hunt8 first discovered the use of nanoparticles for harnessing solar energy in 1978, concluding that adding nanoparticles to conventional coolants could greatly improve heat transfer efficiency in solar collectors. Choi and Eastman9 proposed a new class of metallic nanoparticles to enhance the heat transfer fluids. Sheikholeslami et al.10 examined the turbulence aluminum nanoparticle flow via a tube with the installation of equipment for creating secondary flow. Recently, researchers have noted substantial effects of these nanoparticles, attributed to their small size and excellent thermal conductivity. Nanoparticles have proven highly effective across various industries and engineering applications, including coolants in automobiles, biological fluids, high-performance electronics and cancer treatment, among others11,12,13,14,15.

Heat transfer happens when two close objects with differing temperatures come into contact with one another. Power production, air coolers, nuclear reactor cooling, heat and conduction in tissues, and many more technical, industrial, and domestic applications are all possible with this material16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27. Khalil et al.28 used the CC model to study how double diffusion and changing fluid parameters affect stretched sheet dissipative non-Newtonian fluid flow. Ali et al.29 explained Oldroyd-B nanofluid’s MHD rotating flow across a stretched sheet using the CC model is investigated using finite elements to examine the effects of Dufour and Soret. Khattak et al.30 looked into how the CC model works in a porous medium over a stretching sheet using numerical modelling. The effect of the CC heat flux model and the generated magnetic field on nanofluid flow across a stretched sheet was studied by Nihaal et al.31. In their work on multi-homogeneous cross-nanofluid flows towards a vertical sheet, Srinivas and Ali32 centred on the CC theory that is boosted by activation energy.

The characteristics of electromagnetic radiation, which a substance releases when heated, are known as thermal radiation, and these characteristics change as the material’s temperature changes. Because thermal radiation causes an increase in thermal diffusivity, heat is emitted. Many areas of human existence may benefit from studying thermal radiation in fluid flow. This is especially true in the areas of nuclear power plants, gas turbines, aeronautical engineering, solar panels, and the heating and cooling of food33,34,35. Megahed et al.36 carried out MHD fluid flow across an unstable stretched sheet is modelled with heat flux, changing fluid characteristics, and thermal radiation. Gouran et al.37 compared numerically how porous media and thermal radiation affected a thin liquid film over a stretched sheet. Khan et al.38 investigated when a porous stretched sheet is subjected to magnetohydrodynamic thin film flow influenced by dissipated radiation. Biswas et al.39 explained MHD effect on Maxwell flow on a sheet, also taking higher chemical reaction into account. Using parametric analysis, Rama et al.40 examined the MHD flow of nanofluid in a stretched sheet subjected to heat radiation and chemical sensitivity. You may see more recent work in this approach in the reference41,42,43,44,45.

Porous medium flows with Reynolds numbers greater than 1 to 10 follow the Darcy–Forchheimer law, which may also account for inertial effects. Occasionally, the name Forchheimer is used to refer to a term of inertia in the Darcy equation. This term allows for the consideration of the non-linear behaviour of the pressure differential vs. flow data. Mahmood et al.46 examined why stretched sheet Darcy flow analysis requires thermal conductivity models. Das et al.47 did numerical analysis of bioconvection flow in nanofluid across stretched sheet in non-DF medium. For heat and mass transmission, Rasool et al.48 used the DF flow confined by a stretching surface. Heat transfer via DF flow of Casson fluid across stretched sheets was shown by Zhang et al.49. In their numerical analysis, Sahu et al.50 examined the DF flow across a sheet with heat source effect.

Evidence from previous studies suggests that the CC heat flux impact has not been studied in relation to the flow of silver-capped iron nanoparticles through a DF medium. Additionally, thermal radiation and exponential heat sources are considered. The convection condition improves the boundary. This is possible to convert non-linear PDEs into non-linear ODEs by using appropriate similarity transformations. Numerical results are generated using the RKF-45 method. We shall explore the important parameter behaviors via graphical analysis.

Physical questions

After doing extensive research, we have uncovered the key insights necessary to resolve the following critical concerns.

-

1.

How does our research provide light on the intricate relationship between liquid velocity, strontium stannate nanoparticles, and other important implications?

-

2.

How does the change in CC heat flow affect the temperature of the liquid?

-

3.

The Darcy medium changes the velocity of the liquid in what way?

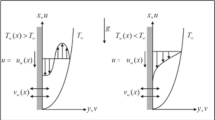

Mathematical formulation

The 2D flow and heat transfer that occurs over a stretched sheet are regarded to be steady relative to the velocity \(\:{u}_{w}\left(x\right)={a}_{0}x\). The flow is assumed to be confined to the region where \(\:y>0\). The flow is produced by two equal and opposing forces acting on the \(\:x\) and \(\:y\) axes, which are perpendicular to the flow. The \(\:x\)-axis shows sheet stretching at a velocity \(\:{u}_{w}\left(x\right)\), whereas the \(\:y\)-axis shows the imposition of a porous medium. As the free stream temperature and a wall temperature is \(\:{T}_{\infty\:}\), \(\:T={T}_{\infty\:}\) remains constant. The physical configuration of the flow model is presented in Fig. 1.

The vector form governing equations are;

Momentum Equation (Vector Form).

Energy Equation (Vector Form);

where \(\:u={\left[u,v,w\right]}^{T}\) is the velocity vector, \(\:p\) is the pressure, \(\:T\) is the temperature, \(\:\rho\:\) is the density, \(\:\mu\:\) is the dynamic viscosity, \(\:g\) is the gravitational acceleration vector, \(\:k\) is the thermal conductivity, \(\:{c}_{p}\) is the specific heat at constant pressure and \(\:\varPhi\:\) is the viscous dissipation (for compressible or high-speed flows).

The fluid flow is compressible, and the Boussinesq approximation is valid for the case of the present problem. Free convection behavior is taken due to buoyancy forces. The momentum equation comprises the buoyancy phenomenon, stagnation point, and free convection phenomenon. Heat transfer is determined in a more precise manner with the utilization of the Cattaneo–Christov heat flux expression instead of classical Fourier law expression in the energy equation. Hybrid nanofluid is considered which is incompressible, and thermal equilibrium holds for both base fluid and hybrid nanoparticles. It is also presumed that the viscous dissipation phenomenon is also contained in the stretching sheet. The sheet is stretched, giving the liquid film a flat surface and preventing the production of waves. The heat flow and viscous shear stress are eliminated by this adiabatic-free surface. Thermophysical properties of the base fluid and nanoparticles (graphene oxide and silver) are given in Table 1.

The governing equations for nanomaterials under standard boundary layer approximations are51,52;

Corresponding boundary conditions are53;

where \(\:l\) is the characteristic length, \(\:{\lambda\:}_{1}\) is the relaxation time, \(\:h\) is the heat transfer co-efficient, \(\:g\) - acceleration due to gravity and \(\:\beta\:\) -thermal expansion coefficient.

The K-K model is applied here, which focuses on the effects of particle-particle interaction potential. The effective \(\:{k}_{nf}\) of nanofluids is expressed as follows:

where, \(\:{k}_{static}\) is the conventional static part,

and \(\:{k}_{Brownian}\) varies over time due to particle Brownian motion.

where the Boltzmann’s physical constant \(\:{k}_{\beta\:}=\:1.38\:\times\:{10}^{-23}{m}^{2}\text{k}\text{g}\:{s}^{-2}{K}^{-1}\), \(\:{r}_{p}\) represents the nanoparticle radius\(\:\:\left({r}_{p}=\:11.8\:nm\right)\).

In particular,

Considering the dependence of viscosity on the particle volume fraction,

were,

\(\:{\mu\:}_{static}={\mu\:}_{f}{\left(1-\varphi\:\right)}^{-0.25}\), \(\:{\mu\:}_{Brownian}=\frac{{k}_{Brownian}}{{k}_{f}}\frac{{\mu\:}_{f}}{{Pr}_{f}}\) and a range of \(\:1\%\) to \(\:4\%\) is selected for the \(\:\varphi\:\).

By applying the following similarity-based changes:

Equation (5) led to the following simplification of Eq. (1) to (3);

The modified conditions are as follows:

where,

\(\:R=\frac{16{\sigma\:}^{*}{T}_{\infty\:}^{3}}{3{k}_{nf}{k}^{*}}\), \(\:Da=\frac{{C}_{F}}{\sqrt{k}}\), \(\:\xi\:=\frac{G{r}_{x}}{R{e}_{x}},\) \(\:{Pr}=\frac{{\left(\mu\:{c}_{p}\right)}_{f}}{{k}_{f}}\), \(\:{K}_{p}=\frac{\nu\:}{k{a}_{0}},\) \(\:Bi=\frac{{\nu\:}_{f}^{1/2}h}{{k}_{f}{a}^{1/2}}\), \(\:\lambda\:=a{\lambda\:}_{1},\)

Reduced \(\:\sqrt{{Re}_{x}}{C}_{f}\) and \(\:\frac{Nu}{\sqrt{{Re}_{x}}}\) defined as follows;

Numerical method

The boundary condition Eq. (8) and the non-linear ODEs (6) and (7) are reduced to a system of first-order equations. Using the flexible step-size numerical methodology known as the RKF-45 (Runge-Kutta-Fehlberg-45) method, ordinary differential equations (ODEs) can be solved efficiently. In order to ensure accuracy and maximize computing performance, it integrates fourth- and fifth-order Runge-Kutta techniques to estimate errors and dynamically modify step sizes. The RKF-45th is very helpful in engineering simulations, scientific computing, and real-time dynamic systems modelling because of its error control mechanism, which improves stability and reliability. The schematic diagram of the numerical method and the mathematical demonstration of the model are shown in Figs. 2 and 3 subsequentially.

Calculation of the solution as follows:

Runge-Kutta method of order 4: \({y_{i+1}}={y_i}+\frac{{25}}{{216}}{k_1}+\frac{{1408}}{{2565}}{k_3}+\frac{{2197}}{{4104}}{k_4} - \frac{1}{5}{k_5}\)

Runge-Kutta method of order 5: \({z_{i+1}}={y_i}+\frac{{16}}{{135}}{k_1}+\frac{{6656}}{{12,825}}{k_3}+\frac{{28,561}}{{56,430}}{k_4}\, - \frac{9}{{50}}{k_5}+\frac{2}{{55}}{k_6}\)

and 6 steps size as follows.

Now we’ll introduce some more dependent variables, like:

Corresponding condition

,

Results and discussion

This paper focuses on silver capped iron nanoparticles flow through a Forchheimer medium with CC heat flux effect. Exponential heat source and thermal radiation are also taken into effect. An improved boundary is achieved by using the mixed convection condition. In sophisticated thermal systems, the Koo-Kleinstreuer framework’s integration of silver oxide nanoparticles with the Cattaneo-Christov heat flow model finds important uses. The thermophysical properties of the base fluid and used nanoparticles are shown in Table 2. This method is perfect for compact microfluidic heat exchangers and high-performance electronic cooling systems because it improves thermal conductivity and precisely simulates heat transport with finite propagation speed. Furthermore, solar thermal collectors and energy storage devices gain from the enhanced heat transfer properties, which boost their responsiveness and efficiency under a range of thermal loads. This study relies on a mathematical model that we built and numerically solved with the help of suitable similarity transformations. After that, the modelled issue will be transformed into a series of ODEs by using a set of comparable variables. The resultant set of ODEs will be solved using RKF-45. Table 3 demonstrates the impact of using the \(\:Pr\) parameter in relation to previous discoveries. Clearly, the current findings align well with those. The graphs will be used to analyse and debate the behaviours of several important factors. In cases when these factors are \(\:Da=0.2,\:{K}_{p}=0.2,\:\varphi\:=0.2,\:\:Pr=4,Q=0.4,\:\:R=0.5\:\)and \(\:\lambda\:=0.2\), \(\:\xi\:=\text{0,2}.\)

In Fig. 4, you can see how the Darcy-Forchheimer parameter (\(\:Da\)) changes the \(\:{f}^{{\prime\:}}\left(\eta\:\right)\) profile. Lower values of \(\:{f}^{{\prime\:}}\left(\eta\:\right)\) are seen as \(\:Da\) rises. With a falling velocity comes a correspondingly smaller momentum barrier layer. For physical reasons, this is due to the fact that higher \(\:Da\) values allow a liquid flow to encounter more resistance, leading to a drop in velocity. The fluid experiences increased drag as it passes through the medium as this value increases. A discernible decrease in velocity results from the fluid particles being slowed down by this increased opposition. When flowing through porous or dense materials, these effects are particularly noticeable.

Figure 5 shows how the Darcy-Forchheimer parameter (\(\:Da)\) affects the temperature field \(\:\left(\theta\:\left(\eta\:\right)\right)\). It is seen that \(\:\theta\:\left(\eta\:\right)\) increases when \(\:Da\) improves. There is an improvement in the thermal boundary layer as well. Convective cooling diminishes with decreasing velocity, and thermal energy tends to build up, increasing the fluid’s temperature. Reduced flow further thickens the thermal boundary layer, which raises the temperature profile even more. Silver capped iron nanoparticles are introduced into the base fluid improves thermal conductivity, which in turn increases heat transfer, and makes the flow less linear, with higher velocities resulting in increased resistance.

Visualized in Fig. 6 is the relationship between the porosity parameter (\(\:{K}_{p}\)) and the \(\:{f}^{{\prime\:}}\left(\eta\:\right)\) profile. Based on this particular figure, we have seen that the \(\:f{\prime\:}\:\left(\eta\:\right)\) drops as the \(\:{K}_{p}\) values increase. The medium becomes less permeable and provides greater barrier to fluid flow as the porosity parameter rises. The fluid experiences increased drag forces inside the porous structure as a result, causing the velocity profile to drop. This happens as a consequence of porosity causing resistance in the flow route, which in turn reduces the mobility of the fluid flow. Furthermore, the velocity of the fluid is more controlled in sliver capped iron oxide nanoparticles then that of sliver nanoparticles case.

In Fig. 7, the temperature field \(\:\left(\theta\:\left(\eta\:\right)\right)\:\)is shown in relation to the porosity parameter (\(\:{K}_{p}\)). As \(\:{K}_{p}\) values rise, the \(\:\theta\:\left(\eta\:\right)\) increases. As a result, the thermal boundary layer also booms. The velocity decreases as the porosity parameter rises, suggesting that the medium becomes more restrictive to fluid flow. The temperature profile rises as a result of the slower flow, which gives heat more time to build up. Additionally, sliver capped iron oxide nanoparticles makes it more stable and less oxidized, so it doesn’t degrade even when heated. For lengthy periods of heating, the nanofluid maintains its thermal stability. Fluids with enhanced heat retention are more suited for use in heat transfer applications.

In Fig. 8, the relationship between the nanoparticle nanofriction number (\(\:\varphi\:\)) and the \(\:{f}^{{\prime\:}}(\eta\:\)) profile is shown. After examining this figure, we can see that when ϕ increases, the \(\:{f}^{{\prime\:}}\left(\eta\:\right)\) decreases. As the strength of the interactions between nanofluid particles decreases, the velocity and momentum boundary layer also diminish. When nanoparticles interact with the base fluid, they create additional resistance, which is measured by the nanoparticle nanofriction number. A larger concentration or activity of nanoparticles results in stronger frictional forces, as indicated by an increase in this number. The velocity profile is decreased by these forces, which oppose the fluid motion.

Pictured in Fig. 9 is the relationship between the nanoparticle nanofriction number (\(\:\varphi\:\)) and the thermal field profile (\(\:\theta\:\left(\eta\:\right)\)). As \(\:\varphi\:\) grows, we can see from the illustration that \(\:\theta\:\left(\eta\:\right)\) also increases. More internal heat is produced by the increased friction between the fluid and the nanoparticles. Localized heating results from this friction’s conversion of kinetic energy into thermal energy. Furthermore, the fluid has more time to absorb and hold heat due to the decreased velocity brought on by nanofriction, which raises the temperature even more. As the volume percentage of nanoparticles increases, the thermal field becomes more apparent. The thermal boundary layer thickens as a result.

The behavior of velocity profile \(\:\left({f}^{{\prime\:}}\left(\eta\:\right)\right)\) with mixed convection parameter \(\:\left(\xi\:\right)\) is depicted in Fig. 10. A measure of the impact of buoyancy on heat and fluid flow relative to the inertia of externally induced or free stream flow is the mixed convection parameter. Depending on the temperature, buoyancy effects become more pronounced as this parameter rises, either promoting or hindering the flow. It is crucial for examining situations involving combined (mixed) convection, when heat and fluid flow behavior are greatly influenced by both forced and natural convection. As \(\:\xi\:\) values rises, \(\:{f}^{{\prime\:}}\left(\eta\:\right)\) also enhances. This leads to thicker momentum layer. Figure 11 illustrates the relationship between the temperature profile (θ(η)) and the relaxation time of the heat flow (\(\:\lambda\:)\). The graph demonstrates that \(\:\theta\:\left(\eta\:\right)\) declines as \(\:\lambda\:\) values rise. The result is the heat barrier layer deteriorating.

A look at Fig. 12 reveals the effect of the Prandtl number (\(\:Pr\)) on the thermal field (\(\:\theta\:\left(\eta\:\right)\)). It may be inferred from this graphic that \(\:\theta\:\left(\eta\:\right)\) decreases as \(\:Pr\) increases. As the temperature of the fluid drops, the thermal boundary layer gets thinner. The reason for this is because the rate of heat diffusion of nanoparticles decreases as \(\:Pr\) increases. When \(\:Pr\:\)rises, the fluid’s capacity to dissipate heat is comparatively weaker than its momentum diffusion. Higher \(\:Pr\) values cause slower heat transport in nanoparticles (or nanofluids), which results in a narrower thermal boundary layer and less thermal conductivity impact.

Figure 13 shows the temperature gradient (\(\:\theta\:\left(\eta\:\right)\)) and bigger values for the EHS parameter (\(\:Q\)). Based on this picture, it is evident that the θ(η) improves as the values of \(\:Q\) increase. Thinner layers of the thermal barrier are produced by decreased temperatures. With a \(\:Q\) greater than zero, the fluid’s surface will emit more heat than average. As a result, \(\:\theta\:\left(\eta\:\right)\) increases as \(\:Q\) levels rise.

Figure 14 shows how the thermal distribution \(\:\theta\:\left(\eta\:\right)\) is affected by the radiation parameter (\(\:R\)). Based on this image, it is evident that the \(\:\theta\:\left(\eta\:\right)\) grows as \(\:R\) increases. Furthermore, at higher \(\:R\) parameters values, the thermal boundary layer becomes better as the temperature rises. By raising thermal conductivity and radiative heat flux, increasing enhances heat transfer performance as the fluid moves across the surface. The temperature rises as a result of the fluid’s enhanced energy absorption, where radiative contributions predominate, underscoring the importance of radiation effects in thermal management for hypersonic applications.Within the realm of physics, the thermal energy of moving nanoparticles is enhanced by radiation, leading to a more uniform distribution of temperatures at higher R values.

Figure 14 serves as a visual representation of the impact that the Biot number (\(\:Bi\)) has on the thermal filed (\(\:\theta\:\left(\eta\:\right)\)). Furthermore, it is worth noting that when the value of \(\:Bi\) grows, the \(\:\theta\:\left(\eta\:\right)\) values likewise increase. Stronger surface convection as opposed to internal conduction is indicated by an increasing Biot number, which enables more effective heat transfer between the fluid’s surface and surroundings. Consequently, the thermal field is strengthened, exhibiting greater temperature gradients close to the surface and better heat dissipation in general. This is due to the fact that convection is the primary mechanism of heat transport. A thicker thermal boundary layer develops because of this.

Tables 4 and 5 presents the computational findings of \(\:{Re}_{x}^{\frac{1}{2}}{C}_{f}\) and \(\:{Re}_{x}^{-\frac{1}{2}}N{u}_{x}\) in relation to the important physical parameters for silver and silver oxide nanoparticles. These results are shown together with the relevant physical parameters. The data shown in Table 4 demonstrates that when the parameters \(\:Fr,\:\varphi\:\) and \(\:Da\) increase, there is a gradual drop in the value of \(\:{Re}_{x}^{\frac{1}{2}}{C}_{f}\) for both silver and silver oxide nanoparticles. When the value of \(\:\xi\:\) grows, the value of 〖\(\:{Re}_{x}^{\frac{1}{2}}{C}_{f}\) likewise increases. The results of the relevant parameters on the \(\:{Re}_{x}^{-\frac{1}{2}}N{u}_{x}\) are shown in Table 5. As the values of \(\:\lambda\:,\:Q,\:R,\:\varphi\:\) and \(\:Bi\) increase, the \(\:{Re}_{x}^{-\frac{1}{2}}N{u}_{x}\) increases for both silver and silver oxide nanoparticles. However, when \(\:Pr\) grows, the opposite influence is seen in both situations. This is because the \(\:{Re}_{x}^{-\frac{1}{2}}N{u}_{x}\:\)shows an increase.

Conclusion

The flow of nanoparticles with silver caps through a Forchheimer medium subjected to the CC heat flux effect is the main topic of this work. It also takes into account thermal radiation and EHS. An improved boundary is achieved by using the mixed convection condition. The Koo-Kleinstreuer framework’s incorporation of silver oxide nanoparticles with the Cattaneo-Christov heat flow model has significant applications in complex thermal systems. Compact microfluidic heat exchangers and high-performance electronic cooling systems benefit greatly from this technique since it enhances thermal conductivity and accurately models heat transport with a finite propagation speed. Energy storage devices and solar thermal collectors also benefit from the improved heat transfer characteristics, which increase their responsiveness and efficiency under various thermal loads. We use the RKF-45 technique to numerically solve the equations governing the described flow and then depict the numerical data on graphs. The main findings are summarized as follows:

-

Velocity of the fluid is more controllebele in hybrid nanoparticles case then that of nanoparticles case.

-

Rate of heat transfer is more influence by silver capped iron oxide nanoparticle when compared to Silver Nanoparticles.

-

As the \(\:Da\) parameter is larger, the fluid’s velocity falls, but as the \(\:\xi\:\) parameter gets larger, it starts to rise.

-

As \(\:{K}_{p}\) and \(\:\varphi\:\) reach higher values, the momentum layer becomes thinner.

-

Temperature of the fluid enhances for higher \(\:Da,{K}_{p},\varphi\:,R\),\(\:Q\) and \(\:Bi\) parameters.

-

The thermal boundary layer becomes less stable as \(\:Pr\) and \(\:\lambda\:\) values increase.

-

For both silver nanoparticles and silver oxide nanoparticles, the value of \(\:{Re}_{x}^{\frac{1}{2}}{C}_{f}\) decreases as the \(\:Fr,\:\varphi\:\) and \(\:Da\) parameters increase.

-

As \(\:{Re}_{x}^{\frac{1}{2}}{C}_{f}\) increases for good values of \(\:\xi\:.\).

-

The function \(\:{Re}_{x}^{-\frac{1}{2}}N{u}_{x}\), for both silver and silver oxide nanoparticles, \(\:{Re}_{x}^{-\frac{1}{2}}N{u}_{x}\) increases when \(\:\lambda\:,\:Q,\:R,\:\varphi\:\) and \(\:Bi\) values grow. However, when \(\:Pr\) values rise, the reverse effect is seen.

Data availability

The data used in the present investigation will be provided by the corresponding author on a reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- \(\:{C}_{F}\) :

-

Forchheimer coefficient

- \(u\:\text{a}\text{n}\text{d}\:v\) :

-

Velocity components along \(\:x\) and \(\:y\) direction\(\:\left({ms}^{-1}\right)\)

- \({u}_{w}\) :

-

Velocity of the stretching surface (\({ms}^{-1}\))

- \(\:{T}_{w}:\:\) :

-

Temperature on the wall\(\:(K)\)

- \(k\) :

-

Porous medium

- \(v_w\) :

-

Velocity of mass flux

- \(\:\lambda\:\) :

-

Relaxation time of heat flux

- \(\:{C}_{f}\) :

-

Skin friction

- \(\:T\) :

-

Temperature of fluid\(\:\left(K\right)\)

- \(\:Da\) :

-

Darcy-Forchheimer parameter

- \(\:Pr\) :

-

Prandtl number

- \(\:{Q}_{0}\) :

-

Exponential heat source

- \(\:R\) :

-

Radiation parameter

- \(\:R{e}_{x}\) :

-

Reynolds number

- \(\:{T}_{0}\) :

-

Reference temperature\(\:\left(K\right)\)

- \(\:{q}_{w}\) :

-

Surface heat flux\(\:(W/m^2)\)

- \(\:{T}_{\infty\:}\) :

-

Temperature away from the surface

- \(\:CC\) :

-

Cattaneo-Christov heat flux

- \(\:KK\) :

-

Koo and Kleinstreuer

- \(\:Nu\) :

-

Nusselt number

- \(\:Q\) :

-

Exponential heat source parameter

- \(\:{K}_{p}\) :

-

Porosity parameter

- \(\:{\tau\:}_{w}\) :

-

Surface shear stress\(\:\left(N{m}^{-2}\right)\)

- \(\:{k}_{nf}\) :

-

Conductivity of nanomaterial \(\:\left(W{m}^{-1}{k}^{-1}\right)\)

- \(\:{\nu\:}_{nf}\) :

-

Viscosity of the nano fluid\(({m}^{2}{s}^{-1})\)

- \(\:{\rho\:}_{nf}\) :

-

Density of nanomaterial\(\left(kg{m}^{-3}\right)\)

- \(\:{\mu\:}_{nf}\) :

-

Viscosity of nanomaterial\(({m}^{2}{s}^{-1})\)

- \(\:{\mu\:}_{af}\) :

-

Viscosity of nano alloy\(\left(kg{m}^{-3}\right)\)

- \(\:\rho\:{{c}_{p}}_{f}\) :

-

Heat capacitance of fluid\((J{kg}^{-1}{k}^{-1})\)

- \(\:{\nu\:}_{f}\:\) :

-

Viscosity of the fluid\(\:({m}^{2}{s}^{-1})\)

- \(\:\rho\:{{c}_{p}}_{nf}\) :

-

Heat capacitance of nanomaterial\(\:(J{kg}^{-1}{k}^{-1})\)

- \(\:{k}_{f}\) :

-

Thermal conductivity of fluid\(\:(W{m}^{-1}{k}^{-1})\)

- \(\:\sigma\) :

-

Electric conductivity\(\:\left(S{m}^{-1}\right)\)

- \(\:\xi\:\) :

-

Mixed convection parameter

- \(\:Bi\) :

-

Biot number

- \(\:DF\) :

-

Darcy Forchheimer

- \(\:EHS\) :

-

Exponential heat source

References

Sajid, T. et al. Magnetized Cross tetra hybrid nanofluid passed a stenosed artery with nonuniform heat source (sink) and thermal radiation: Novel tetra hybrid Tiwari and Das nanofluid model. Journal of Magnetism and Magnetic Materials, 569, p.170443. (2023).

Sajid, T. et al. Quadratic regression analysis for nonlinear heat source/sink and mathematical Fourier heat law influences on Reiner-Philippoff hybrid nanofluid flow applying Galerkin finite element method. Journal of Magnetism and Magnetic Materials, 568, p.170383. (2023).

Sajid, T., Sagheer, M., Hussain, S. & Bilal, M. Darcy-Forchheimer flow of Maxwell nanofluid flow with nonlinear thermal radiation and activation energy. AIP Advances 8(3), 035102 (2018).

Sajid, T., Tanveer, S., Sabir, Z. & Guirao, J. L. G. Impact of activation energy and temperature-dependent heat source/sink on Maxwell–Sutterby fluid. Mathematical Problems in Engineering, 2020(1), p.5251804. (2020).

Sajid, T., Sabir, Z., Tanveer, S., Arbi, A. & Altamirano, G. C. Upshot of radiative rotating Prandtl fluid flow over a slippery surface embedded with variable species diffusivity and multiple convective boundary conditions. Heat. Transf. 50 (3), 2874–2894 (2021).

Nasir, N. A. A. M. et al. Cubic chemical autocatalysis and oblique magneto dipole effectiveness on cross nanofluid flow via a symmetric stretchable wedge. Symmetry, 15(6), p.1145. (2023).

Fangfang, F. et al. S.M., Thermal transport and characterized flow of trihybridity Tiwari and Das Sisko nanofluid via a stenosis artery: a case study. Case Studies in Thermal Engineering, 47, p.103064. (2023).

Hunt, A. J. Small particle heat exchangers, (1978). https://doi.org/10.2172/6070780

Choi, S. U. & Eastman, J. A. Enhancing thermal conductivity of fluids with nanoparticle in: The Proceedings of the 1995 ASME Int. Mech. Eng. Congr. Expo., San Francisco, USA, ASME, FED 231/MD 66. 99–105. (1995).

Sheikholeslami, M., Farshad, S. A., Shafee, A. & Tlili, I. Modeling of solar system with helical swirl flow device considering nanofluid turbulent forced convection. Phys. A: Stat. Mech. Its Appl. 550, 123952 (2020).

Gamaoun, F. et al. Effects of thermal radiation and variable density of nanofluid heat transfer along a stretching sheet by using Keller Box approach under magnetic field. Thermal Science and Engineering Progress, 41, p.101815. (2023).

Anwar, M. I., Firdous, H., Zubaidi, A. A., Abbas, N. & Nadeem, S. Computational analysis of induced magnetohydrodynamic non-Newtonian nanofluid flow over nonlinear stretching sheet. Progress in Reaction Kinetics and Mechanism, 47, p.14686783211072712. (2022).

Muntazir, R. M., Mushtaq, M., Shahzadi, S. & Jabeen, K. MHD nanofluid flow around a permeable stretching sheet with thermal radiation and viscous dissipation. Proceedings of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers, Part C: Journal of Mechanical Engineering Science, 236(1), pp.137–152. (2022).

Pandey, A. K. & Das, A. Rotationally symmetric hybrid-nanofluid flow over a stretchable rotating disk. Euro. J. Mech. -B/Fluids. 101, 227–245 (2023).

Alahmadi, H. & Nawaz, R. A numerical study on nanoparticles shape effects in modulating heat transfer in silver-water nanofluid over a polished rotating disk. Int. J. Thermofluids 22, 100666 (2024).

Ramasekhar, G. et al. Heat transfer innovation of engine oil conveying SWCNTs-MWCNTs-TiO2 nanoparticles embedded in a porous stretching cylinder. Scientific Reports, 14(1), p.16448. (2024).

Divya, A., Jawad, M., Abdelfattah, W. & Kamangar, S. Case Studies in Thermal Engineering Entropy generation of Engine Oil-based two phase tri-hybrid nanofluid due to Riga plate: Modified Magnetic field and Cattaneo-Christov heat Perceptions. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 73, 106603 (2025).

Ali, A. B. M., Riaz, M. B., Singh, N. S. S., Abdelfattah, W. & Jawad, M. Bioconvective MHD flow of Williamson nanofluid with swimming microorganisms and cross-diffusion effects induced by nonlinear stretching surface in porous media. Results Eng. 27, 105660 (2025).

Thenmozhi, D. et al. Analysis of Ti-Alloy nanoparticles in paraffin oil for 3D MHD Darcy‐Forchheimer flow over a Bi‐Directional stretching surface. Eng. Rep. 7 (5), e70136 (2025).

Jawad, M., Saidani, T., Alsaydi, H. A., Abdallah, S. A. O. & Alhushaybari, A. Dynamics of bioconvection on darcy–forchheimer flow of electromagnetic Reiner–Philippoff Nanofluid with characteristics of nonlinear thermal radiation and activation energy. Mathematical Methods in the Applied Sciences. (2025).

Jawad, M. et al. Dynamics of activation energy and gyrotactic microorganisms on radiative Williamson nanofluid with Soret and Dufour bounded by porous nonlinearly stretching surface. Journal of Radiation Research and Applied Sciences, 18(3), p.101595. (2025).

Kumar, M. D. et al. Forecasting heat and mass transfer enhancement in magnetized non-Newtonian nanofluids using Levenberg-Marquardt algorithm: influence of activation energy and bioconvection. Mechanics of Time-Dependent Materials, 29(1), p.14. (2025).

Waseem, M. et al. Non-similar analysis of suction/injection and Cattaneo-Christov model in 3D viscoelastic non-Newtonian fluids flow due to Riga plate: a biological application. Alexandria Eng. J. 103, 121–136 (2024).

Waseem, M. et al. Regression analysis of Cattaneo–Christov heat and thermal radiation on 3D Darcy flow of non-Newtonian fluids induced by stretchable sheet. Case Studies in Thermal Engineering, 61, p.104959. (2024).

Ramasekhar, G. et al. Novel heat exploration investigation for bioconvected Oldroyd-B nanofluid with variable thermal conductivity and arrhenius energy induced by nailed boundary. Numerical Heat. Transf. Part. B: Fundamentals 22, 1–18 (2024).

Jawad, M., Alam, M., Hameed, M. K. & Akgül, A. Numerical simulation of buongiorno’s model on Maxwell nanofluid with heat and mass transfer using arrhenius energy: a thermal engineering implementation. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 149 (11), 5809–5822 (2024).

Waseem, M. et al. Thermal analysis of 3D viscoelastic micropolar nanofluid with cattaneo-christov heat via exponentially stretchable sheet: Darcy-forchheimer flow exploration. Case Studies in Thermal Engineering, 56, p.104206. (2024).

Khalil, K. M., Soleiman, A., Megahed, A. M. & Abbas, W. Impact of variable fluid properties and double diffusive Cattaneo–Christov model on dissipative non-Newtonian fluid flow due to a stretching sheet. Mathematics, 10(7), p.1179. (2022).

Ali, B., Hussain, S., Nie, Y., Hussein, A. K. & Habib, D. Finite element investigation of dufour and Soret impacts on MHD rotating flow of Oldroyd-B nanofluid over a stretching sheet with double diffusion Cattaneo Christov heat flux model. Powder Technol. 377, 439–452 (2021).

Khattak, S. et al. M., Numerical simulation of Cattaneo–Christov heat flux model in a porous media past a stretching sheet. Waves in Random and Complex Media, pp.1–20. (2022).

Nihaal, K. M., Mahabaleshwar, U. S., Pérez, L. M. & Cattani, P. An impact of induced magnetic and Cattaneo-Christov heat flux model on nanofluid flow across a stretching sheet. Journal Appl. Comput. Mechanics 10(3), (2024).

Srinivas Reddy, C. & Ali, F. Cattaneo–Christov double diffusion theory for MHD cross nanofluid flow towards a vertical stretching sheet with activation energy. Int. J. Ambient Energy. 43 (1), 3924–3933 (2022).

Mehmood, Y. et al. Numerical investigation of MWCNT and SWCNT fluid flow along with the activation energy effects over quartic auto catalytic endothermic and exothermic chemical reactions. Mathematics, 10(24), p.4636. (2022).

Mehmood, Y. et al. Numerical investigation of the finite thin film flow for hybrid nanofluid with kerosene oil as base fluid over a stretching surface along with the viscous dissipation and variable thermal conductivity effects. J. Math. 2023 (1), 3763147 (2023).

Mehmood, Y., Alsinai, A., Bilal, M. & Summan, I. Numerical study of unsteady thin film flow and heat transfer of power-law tetra hybrid nanofluid with velocity slip over a stretching sheet using engine oil. Discover Applied Sciences, 7(1), p.28. (2024).

Megahed, A. M., Reddy, M. G. & Abbas, W. Modeling of MHD fluid flow over an unsteady stretching sheet with thermal radiation, variable fluid properties and heat flux. Math. Comput. Simul. 185, 583–593 (2021).

Gouran, S., Vahidi, J., Akbari, H. & Ghasemi, S. E. Thermal radiation and porous medium effects on a thin liquid film over a stretching sheet: a numerical comparative study. Case Studies in Thermal Engineering, 52, p.103753. (2023).

Khan, Z., Jawad, M., Bonyah, E., Khan, N. & Jan, R. Magnetohydrodynamic thin film flow through a porous stretching sheet with the impact of thermal radiation and viscous dissipation. Mathematical Problems in Engineering, 2022(1), p.1086847. (2022).

Biswas, R. et al. Computational treatment of MHD Maxwell nanofluid flow across a stretching sheet considering higher-order chemical reaction and thermal radiation. Journal of Computational Mathematics and Data Science, 4, p.100048. (2022).

Rama Devi, S. V. V. & Gnaneswara Reddy, M. Parametric analysis of MHD flow of nanofluid in stretching sheet under chemical sensitivity and thermal radiation. Heat. Transf. 51 (1), 948–975 (2022).

Alharbi, K. A. M. et al. S.M. and Numerical solution of Maxwell-Sutterby nanofluid flow inside a stretching sheet with thermal radiation, exponential heat source/sink, and bioconvection. International Journal of Thermofluids, 18, p.100339. (2023).

Mishra, S., Mahanthesh, B., Mackolil, J. & Pattnaik, P. K. Nonlinear radiation and cross-diffusion effects on the micropolar nanoliquid flow past a stretching sheet with an exponential heat source. Heat. Transf. 50 (4), 3530–3546 (2021).

Awan, A. U., Shah, S. A. A. & Ali, B. Bio-convection effects on williamson nanofluid flow with exponential heat source and motile microorganism over a stretching sheet. Chin. J. Phys. 77, 2795–2810 (2022).

Swain, K., Animasaun, I. L. & Ibrahim, S. M. Influence of exponential space-based heat source and joule heating on nanofluid flow over an elongating/shrinking sheet with an inclined magnetic field. Int. J. Ambient Energy. 43 (1), 4045–4057 (2022).

Rawat, S. K., Yaseen, M., Shafiq, A., Kumar, M. & Al-Mdallal, Q. M. Nanoparticle aggregation effect on nonlinear convective nanofluid flow over a stretched surface with linear and exponential heat source/sink. International Journal of Thermofluids, 19, p.100355. (2023).

Mahmood, Z., Rafique, K., Khan, U., Muhammad, T. & Hassan, A. M. Importance of thermal conductivity models in analyzing heat transfer of radiative hybrid nanofluid across a stretching sheet using Darcy-Forchheimer flow. Journal Porous Media, 27(7), 1–24 (2024).

Das, B., Hussain, M. A. & Ahmed, S. Numerical computation of bioconvection flow in nanofluid over stretching sheet in non-Darcy medium with Forchheimer correction. In: Reshu Gupta, Mukesh Kumar Awasthi, Dhananjay Yadav, Yashvir Singh (Eds), Nanofluid Dynamics and Transport Phenomenon (209–223). CRC. (2024).

Rasool, G. et al. Numerical scrutinization of Darcy-Forchheimer relation in convective magnetohydrodynamic nanofluid flow bounded by nonlinear stretching surface in the perspective of heat and mass transfer. Micromachines, 12(4), p.374. (2021).

Zhang, X., Yang, D., Israr Ur Rehman, M. & Hamid, A. Heat transport phenomena for the Darcy–Forchheimer flow of Casson fluid over stretching sheets with electro-osmosis forces and Newtonian heating. Mathematics, 9(19), p.2525. (2021).

Sahu, S., Thatoi, D. N. & Swain, K. Darcy-Forchheimer Flow Over a Stretching Sheet with Heat Source Effect: A Numerical Study. In Recent Advances in Mechanical Engineering: Select Proceedings of ICRAMERD 2021 (pp. 615–622). Singapore: Springer Nature Singapore. (2022).

Rasool, G., Shafiq, A., Khalique, C. M. & Zhang, T. Magnetohydrodynamic Darcy–Forchheimer nanofluid flow over a nonlinear stretching sheet. Physica Scripta, 94(10), p.105221. (2019).

Nasir, S., Shah, Z., Islam, S., Bonyah, E. & Gul, T. Darcy Forchheimer nanofluid thin film flow of SWCNTs and heat transfer analysis over an unsteady stretching sheet. AIP Advances, 9(1), 015223 (2019).

Shahzad, A. et al. Thin film flow and heat transfer of Cu-nanofluids with slip and convective boundary condition over a stretching sheet. Scientific Reports, 12(1), p.14254. (2022).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Deanship of Scientific Research, Vice Presidency for Graduate Studies and Scientific Research, King Faisal University, Saudi Arabia (Grant No. 252617). The authors would like to express their sincere gratitude to Manipal University Jaipur and Birla Institute of Technology and Science, Pilani, for their support in the successful execution of this work.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Manipal University Jaipur.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Huda Alfannakh: H.A. Basma Souayeh: B.S. Suvanjan Bhattacharyya: S.B. Devendra Kumar Vishwakarma: D.K.V. Conceptualization, H.A., B.S., S.B. and D.K.V.; methodology, H.A., B.S., S.B. and D.K.V.; software, H.A. and B.S.; validation, H.A., B.S., S.B. and D.K.V.; formal analysis, H.A., B.S., S.B. and D.K.V.; investigation, B.S., S.B. and D.K.V.; resources, S.B.; data curation, H.A., B.S., S.B. and D.K.V.; writing—original draft preparation, H.A.; writing—review and editing, H.A., B.S., S.B. and D.K.V.; visualization, H.A., B.S., S.B. and D.K.V.; supervision, B.S.; project administration, B.S.; funding acquisition, B.S. and D.K.V. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Alfannakh, H., Souayeh, B., Bhattacharyya, S. et al. Computational insights into silver oxide nanoparticles on flow and Cattaneo-Christov heat flux through a Koo and Kleinstreuer model: A heat transfer application. Sci Rep 15, 28427 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-13753-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-13753-2