Abstract

Rain-fed regions have a low quantity of rainfall with an asymmetric distribution. Therefore, by promoting plants like Lathyrus sativus L., as a legume adapted to unfavorable environments, genotypes with high fodder capacity under such conditions would assist food security worldwide. Here, 16 grass pea genotypes were examined in four rain-fed regions during 2016–2017, 2017–2018, and 2018–2019. Dry fodder yield (DY), plant height (PH), days to flowering (DF), and wet fodder yield (WY) were recorded across 12 test environments. Regarding MLM analysis of variance, LRTENV and LRTENV×GEN were significant for all studied traits. Phenotypic variance ranged between 1.42 (DY) to 86.9 (PH). Results showed the possibility of grass pea improvement through selection regarding calculated accuracy of selection (> 0.5). PLS regression emphasized the significant role of rainfall during December, January, February, March and April on DY and WY of grass pea. The DY of 16 genotypes across environments varied between 3.4 t/ha (G12 and G16) to 4.6 t/ha (G11). The WY also varied between 16.9 t/ha (G12) and 22.0 t/ha (G8). AMMI analysis revealed G2, and G6 and BLUP-based indices showed G8, and G11 as climate-resilient genotypes with stable DY and WY in rain-fed regions. In this study, WAASB×DY and WAASB×WY plots with equal weights of 50/50 for stability and performance showed G2, G6 as stable genotypes with high DY and WY values. Simultaneous selection based on overall recorded traits using MTSI index addressed G9 > G2 as promising genotypes. Although the polygon view of genotype by yield*trait depicted G1 and G11 as promising grass pea genotypes but G2, and G9 also had positive intermediate superiority indexes without any weakness considering studied traits. It is concluded WAASB×yield > AMMI > BLUP in terms of comprehensiveness in yield stability analysis of grass pea. Also, superiority index as complementary statistics could be incorporated into simultaneous multi-trait stability approaches for achieving exact selection. The identified grass pea genotypes have promising potential in rain-fed regions and could be good candidates for commercial production.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In rain-fed agriculture that supplies the majority of food resources, especially in undeveloped regions; only rainfall provides the water required for crops and agricultural land. Considering the increasing demand for protein resources from livestock, and the importance of preserving the structure and richness of soil by conducting the correct crop rotation, the need to obtain new plant varieties with promising potential to produce high fodder and adapt well to rain-fed regions is unavoidable1. Cultivation of fodder plants in such regions is mainly based on native and low-yield cultivars, so obtaining cultivars compatible with the aforementioned conditions and replacing them is of great importance. The grass pea (Lathyrus sativus L.) is generally a creeping, and annual plant belonging to the legume family, which is widely cultivated in dry and semi-arid climates due to its high adaptability to unfavorable environments1. It is one of the most important features that distinguishes this plant from other legumes. Properties such as high yield potential, protein content, nitrogen fixation, tolerance to cool weather, drought, salinity and waterlogging, make the grass pea an important choice in crop rotation, soil structure improvement, and reduction of weed and disease populations2. Moreover, in arid conditions, the quantity and distribution of rainfall stand as primary limiting factors and so the introduction of grass pea cultivars adapted to these constraints establishs a substantial potential for enhancing forage yield. Accordingly, the significant impact of climatic and edaphic conditions on grass pea yield and its interaction with the environment has been proved3. So, beyond the compatibility of a specific grass pea cultivar, achieving yield stability across diverse environments is crucial.

The interaction of genotype with the environment is one of the main and most complex issues in plant breeding programs for developing high-yielding, compatible and stable cultivars. To identify cultivars with high and stable yields for different regions with diverse climatic conditions, multiple trials across multi-years and multi-locations have been proposed4. In such experiments, it is necessary to address the degree of stability of cultivars in addition to performance criteria. Several statistical methods have been used to increase awareness of the interaction of genotype in the environment and its relationship with sustainability. One prevalence approach exists to analyze genotype stability is additive main effects and multiplicative interaction (AMMI)5. The AMMI model in combination with ANOVA outputs AMMI1 and AMMI2 biplots, with the first displaying the genotypic means and their relationship to the first PCA and the second showing genotypes’ relationships to the first two PCAs6. Recently, stability analysis approaches based on mixed models (REML/BLUP) are currently in wide use in plant breeding programs7,8. The REML (Restricted Maximum Likelihood) procedure estimates the variance components and genetic parameters, and BLUP (Best Linear Unbiased Prediction) is the ideal selection procedure9. In the context of mixed models, some stability parameters such as the harmonic mean of the genotypic values (HMGV), relative performance of genotypic values (RPGV), and harmonic mean of the relative performance of the genotypic values (HMRPGV) can be calculated to simultaneously evaluate yield stability, and adaptability9. Another new method introduced for analysis of multi-trials in multi-environments is WAASB (weighted average absolute scores of BLUPs) which was described by Olivoto et al.10. This method profits from the advantages of both AMMI and BLUP methods. Briefly, in WAASB, singular value decomposition was applied to the BLUP matrix to analyze genotype × environment interaction generated by a linear mixed model. Then, the biplot of WAASB × dependent variable (Y) which is defined as WAASBY was used to jointly interpret stability and dependent variable productivity.

But the notable clue is that selection based on only one attribute such as yield (as an economic part of the plant), is not the most appropriate strategy; because yield could be influenced by other plant characteristics. Therefore, plant breeders are going to incorporate several traits into an identified stable genotype. To solve this challenge, two approaches, including genotype by yield*trait (GYT)11 and multiple traits stability index (MTSI)12 were proposed to study yield stability considering multi-traits simultaneously. In the GYT method, there are graphical representations which makes it an effective and comprehensive method and also superiority index (SI) value to assess genotypes based on yield*trait combinations. While the MTSI index is calculated based on the distance from the ideal genotype estimated through factor analysis using all measured traits simultaneously. Some researchers11,13,14 emphasized the ability of GYT in recognition of superior genotypes with stable performance. Also, the capability of MTSI in screening several types of plant germplasm regarding some agro-morphological traits simultaneously was proved15,16,17,18. As a novelty, in the present study, several agro-morphological traits of grass pea were measured to apply multi-traits stability as well as calculate newly defined stability parameters. Hence, traits including plant height, days to flowering, wet fodder yield, and dry fodder yield of 16 grass pea genotypes were evaluated in four rain-fed regions of Iran during 3 consecutive years to (i) identify which monthly rainfall could affect grass pea`s forage yield in rain-fed conditions and (ii) explore the climate-resilient grass pea genotype that waswell adapted to test environments using AMMI, BLUP, genotype by yield*trait and MTSI approaches.

Materials and methods

Plant materials, experimental sites, and experiments layout

In the present study, 16 grass pea genotypes (Table 1) kindly provided by the gene bank of Dryland Agriculture Research Institute of Iran (DARI) accompanied by a check genotype (Naghadeh) were used. Among the studied germplasm, Naghadeh is a local variety that was domesticated to warm rain-fed regions. In addition, the improved genotypes (Sel.290, Sel.449, and Sel.587) have been selected among lines which were introduced by the international grass pea nursery of ICARDA and evaluated primarily in rain-fed regions of Iran over several years. The seeds of grass pea genotypes were planted in four rain-fed regions (Fig. 1) with semi-warm weather including Gachsaran (E1, E2, and E3 with longitude 30°18´E and latitude 50°59´N), Koohdasht (E4, E5, and E6 with longitude 47°36´E and latitude 33°31´N), Mehran (E7, E8, and E9 with longitude 46°09´E and latitude 33°07´N), and Shirvan and Chardavol (E10, E11, and E12 with longitude 57°55´E and latitude 37°27´N) over three consecutive years (2016–2017, 2017–2018, and 2018–2019). Precipitation and mean temperature during growing months in each studied environment were presented in Table S1. In each year × location combinations, a randomized complete block design (RCBD) with three replications was utilized. Each plot consisted of four rows, each 4.5 m in length, with a spacing of 25 cm between rows. The seeding rate was maintained at 150 seeds per m^2 across all environments.

Planting was done during the first week of December, and afterward, field practices, including weed control, were executed manually during crop growth and development. During the growing season, days to flowering (DF), and plant height (PH) (cm) were recorded. At the time of harvest (April), wet fodder yield (WY) (ton.ha−1), and dry fodder yield (DY) (ton.ha−1) were measured. At 50% of flowering stage, one of the middle rows in each plot was harvested, and after measuring WY was exposed into the sun to dry and record DY. Then, regarding space between rows and length of each row, records were converted to t ha-1 (tons per hectare).

Analysis of variance

After checking outlier data using the Anderson-Darling test, the homogeneity of variance was examined by the Levene’s test. Firstly, analysis of variance based on randomized complete block design was done for each environment separately. Afterward, mean comparison among genotypes across environments was calculated using the Duncan multiple range test. Linear mixed model implemented by Olivoto and Lucio19 was used to evaluate the genotypes’ differences across environments. Accordingly, the significance of each effect for the studied traits was tested by the likelihood ratio test (LRT) with a two-tailed chi-square test with one degree of freedom. So, for each environment, the traits were initially fitted into a linear mixed-effect model by considering environment and environment-by-genotype interaction as random effects and genotype as a fixed effect10.

Moreover, regarding the importance of rainfall in rain-fed regions, it was taken as covariate beside DY and WY traits in partial least squares (PLS) regression analysis using GEA-R (genotype × environment analysis with R) software20 version 4.1 (https://gea-r.software.informer.com/) for depicting the importance of monthly rainfall affecting grass pea yield. Here in, monthly rainfall from December to April was regarded as a covariate. As shown, the PLS model consists of an independent matrix X (rainfall data), a dependent matrix Y (DY or WY), and the latent variables t as follows:

where matrix T contains X-scores, matrix P contains the X-loadings, matrix Q contains the Y-loadings, and F and E are the residual matrices. Finally, PLS results were presented in the form of a biplot.

Additive multiplicative mean interaction (AMMI)

AMMI analysis was performed with R software using function “performs_ammi” of metan package19. The AMMI model for analyzing yield data in grass pea is considered by the following equation:

where, yij stands for yield response of the ith genotype in the jth environment; µ is the grand mean; \(\:{\alpha\:}_{i}\) and \(\:{\tau\:}_{j}\:\)represents the ith genotypic effect and the jth environment effect, respectively, while \(\:\sum_{k=1}^{p}{\lambda\:}_{k}{\alpha\:}_{ik}{t}_{jk}+{\rho\:}_{ij}+{\epsilon\:}_{ij}\) models the multiplicative genotype × environment interaction effect in which \(\:{\lambda\:}_{k}\)stands for the singular value for kth interaction principal component axis (IPCA), \(\:{\alpha\:}_{ik}\) defined as the ith genotype eigenvector for axis k, tjk is the jth environment eigenvector for axis k, \(\:{\rho\:}_{ij}\)stands for the residual not explained by the IPCAs used in the model, whereas \(\:{\epsilon\:}_{ij}\)is seen as the error relevant to the model19.

Best linear unbiased predictor (BLUP)

After MLM analysis, it is assumed that genotype and G×E are random effects19 to predict genetic parameters using the argument “genpar” in function gamem_met. By using “blup_indexes” from package “metan”, BLUP based stability indices9 including the estimation of HMGV (to infer both yield and stability), RPGV (to investigate the mean yield and genotypic adaptability), and HMRPGV (to evaluate stability, adaptability, and yield simultaneously).

where n is the number of environment; GVij is the genetic value of ith genotype in jth environment where \(\:{GV}_{ij}={\mu\:}_{j}+{g}_{i}+{ge}_{ij}\), µj is the average of jth environment, gi is the BLUP value of ith genotype, and geij is the BLUP value of the interaction between ith genotype and jth environment; Mj is the mean grain yield in the jth environment.

Weighted average of absolute scores (WAASBi)

After MLM analysis of variance, the genotype and genotype (G) × environment (E) had been assumed as random effects10 to estimate genetic parameters using the argument “genpar” in the function gamem_met in metan package. Then, stability analysis was performed by the calculation of WAASBi using the function “waasb” in the metan. In this process, WASSBi was estimated based on a single value decomposition of the G×E interaction effects from the matrix of the BLUP as follows:

Where WAASBi is the weighted average of absolute scores of the ith genotype or environment, IPCAik is the absolute score of the ith genotype or environment in the kth IPC, and EPk is the magnitude of the variance explained by the kth IPC.

As shown, WAASBYi is the superiority index with different weights between yield and stability for the gth genotype, ƟY and ƟS are the weights for yield and stability, respectively; rGg and rWg are the rescaled values of the gth genotype for yield and WAASB, respectively.

Multiple trait selection index (MTSI) and genotype by yield*trait computation (GYT)

The MTSI was applied to calculate the mean performance and stability of studied traits which having significant G×E interaction comprising DF, PH, WY, and DY. In this way, except of DF, increasing of other measured traits was our desired goal so the vector of trait importance designated as c (l, h, h, h) that was concerned with DF, PH, WY, and DY, respectively.

Then, this data was used for WAASB analysis before the MTSI approach19. Finally, the MTSI analysis was done by the function MTSI in metan package as follows.

Where MTSIi is the multi-trait stability index of the genotype i, γij is the score of the genotype i in the factor j, and γj is the score of the ideal genotype in the factor j. Scores were calculated based on factor analysis for genotypes and traits.

In the following, to conduct GYT, the mean data from three years for each trait of grass pea genotypes were calculated. Then, the DY of each genotype was multiplied or divided by the respective trait value depending upon the breeding objectives11. Hence, for PH, and WY values of DY trait combination were obtained by multiplying the DY with the trait value of each genotype. However, in the case of DF traits for which the lesser value was desirable, the DY trait combinations were computed by dividing the value of DY by this trait. In order to remove the error due to different measuring units of traits, the values of GYT table were standardized according to the following equation suggested by Yan and Fregeau-Reid11:

Where Pij represents the standardized value of ith genotype for jth trait or yield combination in the standardized table, Tij is the original value of genotype i for jth trait or yield combination in the GYT tables, Tj is the mean across genotypes for jth trait or yield combination, and Sj is the standard deviation for jth trait or yield combination. The standardized data of GYT were used to compute the superiority index (SI) (\(\:\frac{DY/DF+DY*PH+DY*WY}{3}\)) and mean SI values to identify the superior genotype based on multiple traits. The same data set was subjected to GYT-biplot analysis to get the graphical view of the tester vector biplot so-called which-won-where biplot, using the GGE-biplot software v.8.2.

Results

MLM analysis of variance and PLS regression

Preliminary inspection of collected raw data showed E9 as an outlier environment and hence it was eliminated from further analysis. The simple ANOVA results pertaining to each environment, correlation between studied traits, as well as the performance of genotypes based on measured traits depicted in Table S2, Table S3 and Table S4. In the following, mixed linear analysis of variance (Table 2) manifested significant differences among the studied environments (LRTENV) as well as genotype × environment interactions (LRTENV×GEN) in terms of all studied traits. The coefficient of variation of GEI (Table 2) as an indicator of trait reaction to the environment was positive for recorded traits as well. The major gene heritability (h2mg) showed a medium heritability for studied traits (Table 2). In the following, the accuracy of genotypic selection (Table 2) showed a maximum value of 0.728 for DY followed by DF (0.709), WY (0.574), and PH (0.552), respectively. In the present study, both genotypic and residual coefficients of variation showed low values. As a result of genotype × environment interaction, both DY and WY (as economical parts) varied across test environments (Fig. 2A and C) and fluctuated (Fig. 2B and D) throughout environments. As illustrated in Fig. 2A and C, the E1 and E11 had minimum values of DY (1.5 t/ha) and WY (8.7 t/ha) respectively. Among test environments (Fig. 2A and C), the E10 possessed the maximum value for both DY (8 t/ha) and WY (36.9 t/ha).

Results pertaining to PLS regression by considering monthly rainfall as a covariate (Fig. 3) showed that rainfall from planting until harvesting has a significant role in the interaction of both DY and WY with test environments in rain-fed regions. The first and second factors in the PLS biplot explained 71.21% and 69.96% of the GEI variance (Fig. 3) relevant to DY and WY, respectively. Among the test environments, E3, E6, and E12 had the highest value of monthly rainfall (Fig. 3). It is resulted that all month’s rainfall in rain-fed conditions had a key role in the interaction of G2, G4, G6, G7, G8, G9, and G10 (Fig. 3) with the environment considering DY trait. In contrast, WY of genotypes G2, G3, G4, G6, G7, G8, and G16 (Fig. 3) showed significant interaction with rainfall during the above-mentioned months.

Additive main effects and multiplicative interaction analysis (AMMI)

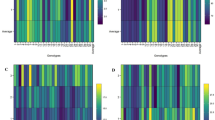

The AMMI analysis recorded significant variation (p < 0.01) among the studied genotypes, environments, and also GEI regarding DY and WY (Table 3). The GEI effect of both DY and WY was significantly explained by the first three PCs. Among them, the first PC contributed 44% and 50% towards the total GEI of DY and WY respectively. Whilst second and third PCs contributed 23.40% and 11.60% for DY and 19.10% and 14.90% for WY respectively. The AMMI1 bi-plot (Fig. 4A and C) projects genotypes onto the ordinate and the abscissa representing the additive main effect of genotypes and the effects of interplay between genotype and environment, respectively. As illustrated (Fig. 4A and C), the abscissa represented the yield means of the studied grass pea genotypes while the ordinate stood for the scores of the IPCA1 of each grass pea genotypes. The origin of both the abscissa and the ordinate axes signified the average yield and zero effects of genotype and environmental interaction. Unlike AMMI1, regarding the AMMI2 bi-plot (Fig. 4B and D), genotypes located closer to the origin of the AMMI2 bi-plot have lower influences of genotype by environmental interaction and thus higher stability across environments.

In this study, DY means on the right side of the abscissa axis were greater than those on the left side (Fig. 4A). On the other hand, deviations from the origin along the ordinate axis meant environmental influences on DY means. Locations of genotypes farther away from the abscissa axis demonstrated the greater environmental effects on dry fodder yield means, and thus less stability (Fig. 4A). Consequently, G1, G2, G3, G5, G6, G7, G8, G9, and G11 had DY above the average yield of all grass pea genotypes (Fig. 4A). As for stability, G2 was relatively close to the abscissa on the bi-plot, indicating its stability (Fig. 4B). The genotype G2, also got first rank of AMMI stability value (ASV) (Table 4) and promising DY value. In regard to WY (Fig. 4C), genotypes G1, G2, G3, G5, G6, G8, G10, G11, and G13 possessed WY values higher than the grand mean. From a point of view of stability (Fig. 4D), G14 with a relatively close distance to bi-plot origin could be calculated as WY stable genotypes. Although the ASV index (Table 4) also manifested genotype G14 as the first rank of a stable genotype but detailed focusing showed G6 is most acceptable considering its WY performance, acceptable ASV`s rank, as well as being nearing theAMMI1 biplot origin (Fig. 4D).

Best linear unbiased prediction (BLUP)

Comparison of predicted DY performance (Fig. 5A) using the BLUP method revealed that G1, G2, G3, G5, G6, G7, G8 G9, G11, and G13 have predicted means higher than the grand mean. In return, G1, G2, G3, G5, G6, G8, G10, G11, and G13 have predicted WY (Fig. 5B) more than the total mean (mean across all environments). Overall, G11 and G8 stood out for having the highest predicted means among the tested genotypes for DY and WY, respectively (Fig. 5A and B). In the following, the BLUP-based stability indices such as HMGV, RPGV, and HMRPGV (Table 4), were estimated using BLUP-derived values for both DY and WY to check which method can be a better choice for selecting stable and high-yielding genotypes. The genotypes G8 and G11 were identified as highly stable with high WY and DY according to the ranks of BLUP-based stability parameters (Table 4).

WAASB × yield stability analysis

In the present study, the WAASB stability parameter accompanied by both DY and WY was applied for screening grass pea genotypes in the studied rain-fed regions. Results showed that four classes of grass pea genotypes including I, II, III, and IV (Fig. 6A and B) could be identified considering both types of yield. According to DY×WAASB plot (Fig. 6A), in class I as an indicator of unstable as well as low yield genotypes, G4, G8, G13, G15, and G16 were recognized. In class II (Fig. 6A), the genotype G5 with higher DY values than the overall DY performance and also high WAASB values (as unstable genotypes) was located. In this regard, environments E3, E5, E10, and E11 (Fig. 6A) were recognized as good discriminators for genotypes like those located in class II. Although some of the studied grass pea genotypes such as those in class III (G10, G12, and G14) possessed weak DY (Fig. 6A) but had remarkable stability over studied environments. Among the studied grass pea genotypes, G1, G2, G3, G6, G7, G9, G11 have been inferred as superior genotypes with acceptable DY across rain-fed regions, which also had low values for the WAASB stability parameter (Fig. 6A).

About the WY trait (Fig. 6C), the distribution of the genotypes and test environments in the two-dimensional space of the WY×WAASB plot was varied compared with the DY×WAASB. In the WY×WAASB biplot (Fig. 6A), G1, G2, G3, G6, G10, and G11 (in quarter four) possessed low WAASB values and also performed better than the overall mean. The genotypes G4, G7, G9, and G14 were detected as stable but with low yield genotypes. Considering Fig. 6C, G5, G8, and G13 were unstable genotypes with WY greater than the overall mean performance.

In contrast to other methods of yield stability analysis, a plant breeder could benefit a lot by plotting values of WAASB against dependent variables (WY and DY) regarding different weights for each of them (Fig. 6B and D). The WAASB/DY (Fig. 6B) and WAASB/WY (Fig. 6D) heatmaps showed that depending on the researcher’s preference as to which dependent variables or WAASB parameter have had a higher weight (Fig. 6B and D), the ranking of the grass pea genotypes could be different. Here, with a weighting of 0/100 as well as 100/0 (DY/WAASB), genotypes G16, and G11 could be chosen, respectively. Likewise, with equal weights for each DY and WAASB index (50/50) (Fig. 6B) as equivalent to a simple DY/WAASB plot, genotype G2 could be considered as the winner genotype. Results showed that G6 had the highest rank regarding weights of 0/100 and 50/50 for each WY and WAASB (WY/WAASB) (Fig. 6D) respectively. Analysis of the WY/WAASB heatmap (Fig. 6D) revealed G8 as the best one in 100/0 weighting.

Ranking studied grass pea genotypes correspondence to DY and WAASB values without any weighting (A) and with weighting regarding desired goal (B). Green and blue diamonds (A) showed environments and genotypes respectively. The color column in right hand (B) showed genotypes ranks which ranged between 1 to 16.

Multi-trait stability (MTSI) approaches

In the present study, factor analysis based on measured traits showed that the first two factors explained 82.3% of the data variation. After factor analysis, traits PH, and DF showed the highest impact in the first factor while traits WY, and DY showed in the second factor (Table 5). Regarding the desired selection sense for grass pea under rain-fed region (Table 5), the goals were successfully achieved for all studied traits except of WY, which had a positive sign but zero value. Results showed that genotype`s rank is varied regarding MTSI value (Fig. 7) and the genotype with the highest value of the MTSI is in the center, and the genotype with the lowest value of the MTSI is located in the outermost circle. It is concluded from MTSI analysis that G9 (Fig. 7) is in the first rank followed by G2, as the most ideal stable genotype.

Further analysis of genotype × environment was done through GYT analysis which ranked grass pea genotypes based on their levels in combining DY as a dependent variable with PH, DF, and WY. Hence, after construction of genotype by trait table (Table 6A) regarding breeding objective of grass pea specifically in rain-fed region, the GYT table (Table 6B) was produced by multiplying (PH, and WY) or dividing (DF) of DY into studied agro-morphological traits. Thus, in the GYT table (Table 6, B) a larger value is always more desirable. Results showed that the first three ranks of grass pea genotypes based on DY/DF are as follows: G11 > G1 > G2 (Table 6B). The order of the first three ranks of studied genotypes regarding DY*PH was G1 > G11 > G7 (Table 6B). As a result, the order of G1 > G11 > G3 was detected for studied genotypes based on DY*WY (Table 6B). As a benefit of GYT analysis, it is possible to identify the strengths and weaknesses of the selected genotypes. So, after standardization of yield*trait combinations (Table 7), the polygon view of GYT biplot (Fig. 8) and superiority indices (Table 7) were computed.

The polygon view of GYT biplot represents the trait profile of 16 grass pea genotypes (Fig. 8). As illustrated in Fig. 8, the GYT biplot explained the 98.6% of the total variation (PC1 = 95.5% and PC2 = 3.1%). The GYT biplot (Fig. 8) showed strong correlation between all DY*trait combinations. The biplot depicted that five radiation lines perpendicular to the polygon sides divided the polygon into five sectors, out of which only one sector possessed the DY*trait combinations. This sector involved all DY*trait combinations and two grass pea genotypes (G1, and G5) for which G1 was the winner genotype. It implies that G1 is the best genotype for PH, DF, and WY in connection with DY (Fig. 8). In GYT analysis, superiority indices (Table 7) which were calculated by integrating all the standardized DY*trait combination values ranked genotypes by the mean of all traits, where high values of SI indicate the best genotypes. Considering SI values relevant to studied grass pea genotypes (Table 7), genotypes G4, G12, G14, G15, and G16 with minus SI values were not superior at all. In this study, some genotypes such as G8, G10, and G13 had positive SI values that were near zero. As a result (Table 7), genotypes G2, G3, G5, G6, G7, and G9 with positive SI values around 0.5 could be calculated as intermediate superior genotypes, whereas just genotypes G1, and G11 (with SI values higher than 1) were detected as superior genotype. The field performance of G1 (IFLA-1707) and G9 (IFLA-1547) as examples of other stable genotypes inclusing G2 (IFLA-1864), and G11 (IFLA-2025) has been illustrated in Figure 9.

Discussion

As a consequence of climate change phenomena such as fluctuating rainfall, low water availability, and increasing temperature, crop yield losses are expected. In this state, introducing alternative varieties or new crops has priority to guarantee a stable food supply. In this term, grass pea (Lathyrus sativus L.) is a novel annual forage crop that isaccommodated to difficult conditions21. Hence, by evaluating grass pea germplasm and developing new cultivars compatible with such conditions especially rain-fed regions which are dominant in many climatic territories, it is expected to improve crop rotation as well as fodder yield in drylands22,23. Accordingly, in the present research, agro-morphological response of diverse grass pea germplasm including 16 promising genotypes from North Africa, South Asia, and West Asia has been evaluated in rain-fed regions of Iran over three consecutive years. In this study, significant differences were seen among studied grass pea genotypes based on all studied traits (DF, PH, WY, and DY), which implies the existence of vast genetic variability. Likewise, G×E effect was significant for all recorded traits, indicating the varied response of each genotype across test environments. Hence, it results that the selection of any grass pea genotypes just considering its yield potential is not applicable and it needs to do stability analysis24,25. Similarly, Ahmadi et al.26 and Vaezi et al.27 using non-parametric and GGE-biplot analyses represented the existence of a significant G×E effect for DY of grass pea. In this study, variability of DY of genotypes (G12 and G16 with 3.4 t/ha and G11 with 4.6 t/ha) was not in accordance with what happened for WY and genotypes with the highest value of WY (G8 with 22.0 t/ha) did not have necessarily the highest value of DY. This phenomenon implies that measuring dry fodder weight is more important than wet weight because it provides a more accurate assessment of the nutritional value of forage crops28. In addition, the stability of forage performance can depend on various factors, including whether the forage is wet (fresh) or dry. However, the consensus in agricultural practices often emphasizes the importance of dry forage stability as it is crucial for long-term storage and feed efficiency. Fresh forage may be important for immediate feeding, but dry forage is vital for consistent nutrition over time. Stability in both forms is relevant, but dry forage tends to be prioritized for its economic and practical benefits.

The clue is that water is the determinant agent in rain-fed agriculture29and therefore, for practical inference it will be more beneficial to consider rainfall accompanied by stability subject simultaneously in such a state. Herein, both WY and DY of studied grass pea genotypes were inspected beside monthly rainfall as a covariate and clarified that rainfall from planting time (December) until forage harvest (April) had a critical role in grass pea`s wet fodder yield and dry fodder yield. Hence, it is concluded that each month’s rainfall in rain-fed regions has a significant portion in explaining G×E interaction which was detected for grass pea. The reliability of PLS regression for identifying monthly rainfall influencing crop yield was addressed in several crops such as barley30and chickpea31. Similar to our findings, AbdelMoneim1 has also proved the significant role of spring rainfall on DY of grass pea in rain-fed regions. To sum up, water resource limitations as a consequence of climate change could threaten imperative regions of grass pea production in Asia32 and so the feasibility of regions considering the suitability of precipitation during grass pea growth is unavoidable.

Pleasing the above in consideration, grass pea`s forage yield and its stability are the main objectives of grass pea breeders25. Therefore, by applying the AMMI model as one of the powerful statistical tools for the analysis of G×E interaction33 the GEI effects were partitioned into 10 multiplicative terms (IPCAs) that the first three of them had significant effects. It is suggested that the interaction between the 16 grass pea genotypes and the four locations in three consecutive growing seasons was predicted by the IPCA1 and the IPCA2 which accounted for 67.4% and 69.1% of the total variation for DY and WY respectively. The two significant IPCAs detected in the present study are sufficient for the identification of superior genotypes, because Gauch and Zobel (1996) validated the sufficient accuracy of projecting the AMMI model with the first two significant IPCAs. In the present study, AMMI analysis identified G2 as the stable genotype for DY while G6 was the superior stable genotypes regarding WY. For further evaluation of the studied grass pea genotypes and also for doing comparable analysis, the BLUP values related to each genotype in each environment were calculated. Our results showed that G11 and G8 had the highest predicted means as well as lower ranks of BLUP indices among the tested genotypes for DY and WY, respectively. Although discrepancies were found between the results of BLUP and AMMI, detailed focusing on BLUP indices showed that AMMI based identified genotypes (G2, G6) also had desirable ranks (third rank) regarding BLUP indices (Table 4). In contrast, genotypes recognized through BLUP-based indices (G8, G11) despite having high performance did not possess high stability (Fig. 4B and D). This finding showed the comprehensiveness of AMMI compared to BLUP in grass pea. In the following, WAASB/DY and WAASB/WY analysis as complementary methods that implement statistical aspects of both AMMI and BLUP showed G2 and G6 as stable genotypes with promising performance. The advantage of WAASB × yield is discrimination according to the breeder`s desired goal10 by assuming varied weights for responsible variables (DY or WY) and stability parameters (WAASB). Regarding this item, in rain-fed regions with several limitations and production obstacles, it is proposed to select weights of 50/50 for stability index (WAASB) and yield or lower weights such as 40/60.

A new subject recently applied for long-term field studies is simultaneous evaluation of multi-traits across multi-trials12. Such studies will show more realistic results because crop yield is a multi-dimensional trait that is influenced by several related traits. Considering the properties of rain-fed regions, grass pea genotypes with a short growth period and high fodder yield are desired34 and therefore, MTSI index was calculated regarding the mentioned desired goals. In line with the findings of Lee et al.35 and Dudhe et al.36 in other crops, both MTSI index and WAASB/DY plot resulted in the same genotypes and G2, and G09 were selected as multi-trait stable genotypes as well. In detail, the selected genotype through MTSI (G2, and G9) will achieve all desired goals except for wet fodder yield (WY). Indeed, failure to improve WY through MTSI could not decrease the importance of MTSI index because grass pea is planted for its DY, not for WY. In this study, GYT polygon view showed genotype G1 out of studied grass pea genotypes as the superior genotype and this result was controversial with results of MTSI. This finding is obvious because the nature of GYT analysis11,37 is differed from MTSI index12. By detail focusing on G1, it is revealed that this genotype is located in class IV (high yielding with to some extent stability) according to DY × WAASB plot. As shown in the WAASB/DY plot, genotype G1 had good ranks regarding high weight score for DY and therefore, it is concluded that GYT aimed to select genotypes with promising yields in the first step. Although, genotypes G2, and G9 were not selected via GYT biplot, regarding superiority index (SI) as a differentiative aspect of GYT analysis from other ones11these genotypes do not have any weaknesses in rain-fed regions regarding recorded traits. Moreover, in line with reports of Mohammadi38Faheem et al.13and Welderufael et al.14all the identified promising stable grass pea genotypes through stability analysis methods had positive values of SI which indicates the segregation power of SI as criteria for detecting stable grass pea genotypes. According to SI values38all of the selected genotypes have no weakness (minus values for studied traits), and there are also some intermediate superior genotypes (SI values around 0.5 and 1), which were also selected by means of stability methods. Parallel to a previous study11 superiority index is a rigorous complementary index for recognition of promising stable grass pea genotypes in rain-fed regions.

Conclusion

Significant G×E interaction was detected for all studied agro-morphological traits of grass pea in rain-fed regions. In this way, rainfall during grass pea field establishment until the end of the growth phase has a critical role in its production and affects its interaction with the rain-fed environment. Regarding grass pea yield stability analysis, our findings showed the efficiency of studied methods as follows: WAASB/yield = AMMI > BLUP. Accordingly, both AMMI and WAASB/yield showed G2 (IFLA-1864), and G6 (IFLA-1553) as stable genotypes with promising performance for DY and WY in rain-fed regions of Iran. While BLUP-based indices introduced G8 (IFLA-1812), and G11 (IFLA-2025) as stable genotypes. Since DY and WY are multidimensional attributes that are directly or indirectly affected by other agronomic traits, multiple-trait stability approaches such as MTSI and genotype by yield*trait have been found to be more appropriate and could be recommended. Here, the aforementioned methods clarified G1 (IFLA-1707), G2 (IFLA-1864), G9 (IFLA-1547), and G11 (IFLA-2025) as superior genotypes.

Finally, by cultivating identified grass pea cultivars adapted to rain-fed conditions it is possible to produce a significant amount of suitable fodder by replacing it in the crop rotation of these lands while benefiting from its many advantages in line with the goals of sustainable agriculture (improving soil texture, increasing fertility and preventing erosion). All stability criteria, had approved the un-stability of Iranian local varieties (Naghadeh) and ICARDA`s lines compared with external materials (Morocco, Pakistan, and Bangladesh) which emphasizeson the necessity of considering external germplasm to achieve resilient grass pea genotypes in rain-fed regions.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

AbdElMoneim, A. M., Khair, M. A. & Cocks, P. S. Growth analysis, herbage and seed yield of certain forage legume species under rainfed conditions. J Agron. Crop Sci 164, (1990).

Vaz Patto, M. C. et al. Lathyrus improvement for resistance against biotic and abiotic stresses: from classical breeding to marker assisted selection. Euphytica 147, (2006).

Fikre, A., Negwo, T., Kuo, Y. H., Lambein, F. & Ahmed, S. Climatic, edaphic and altitudinal factors affecting yield and toxicity of Lathyrus sativus grown at five locations in Ethiopia. Food Chem. Toxicol 49, (2011).

Reckling, M. et al. Methods of yield stability analysis in long-term field experiments. A review. Agronomy for Sustainable Development vol. 41 at (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13593-021-00681-4

Gauch, H. G. Model selection and validation for yield trials with interaction. Biometrics 44, (1988).

Bocianowski, J., Warzecha, T., Nowosad, K. & Bathelt, R. Genotype by environment interaction using AMMI model and Estimation of additive and epistasis gene effects for 1000-kernel weight in spring barley (Hordeum vulgare L). J Appl. Genet 60, (2019).

Torres Filho, J. et al. Genotype by environment interaction in green Cowpea analyzed via mixed models. Rev Caatinga 30, (2017).

de Sousa, A. M. et al. R. L. F. C. B. Prediction of grain yield, adaptability, anstability in landrace varieties of Lima bea(Phaseolus lunatus L). Crop Breed. Appl. Biotechnol 20, (2020).

de Resende, M. D. V. Software Selegen-REML/BLUP: A useful tool for plant breeding. Crop Breed. Appl. Biotechnol 16, (2016).

Olivoto, T. et al. Mean performance and stability in multi-environment trials i: combining features of AMMI and BLUP techniques. Agron J 111, (2019).

Yan, W. & Frégeau-Reid, J. Genotype by yield∗trait (GYT) biplot: A novel approach for genotype selection based on multiple traits. Sci Rep 8, (2018).

Olivoto, T., Lúcio, A. D. C., da Silva, J. A. G. & Sari, B. G. & Diel, M. I. Mean performance and stability in multi-environment trials II: selection based on multiple traits. Agron J 111, (2019).

Faheem, M., Arain, S. M., Sial, M. A., Laghari, K. A. & Qayyum, A. Genotype by yield*trait (GYT) biplot analysis: a novel approach for evaluating advance lines of durum wheat. Cereal Res. Commun 51, (2023).

Welderufael, S., Abay, F., Ayana, A. & Amede, T. Genetic diversity, correlation and genotype × yield × trait (GYT) analysis of grain yield and nutritional quality traits in sorghum (Sorghum bicolor [L.] Moench) genotypes in tigray, Northern Ethiopia. Discov Agric 2, (2024).

Benakanahalli, N. K. et al. A framework for identification of stable genotypes basedon mtsi and mgdii indexes: An example in guar (cymopsis tetragonoloba l.). Agronomy 11, (2021).

Singamsetti, A. et al. Genetic gains in tropical maize hybrids across moisture regimes with multi-trait-based index selection. Front Plant. Sci 14, (2023).

Taleghani, D., Rajabi, A., Saremirad, A. & Fasahat, P. Stability analysis and selection of sugar beet (Beta vulgaris L.) genotypes using AMMI, BLUP, GGE biplot and MTSI. Sci Rep 13, (2023).

Sellami, M. H., Pulvento, C. & Lavini, A. Selection of suitable genotypes of lentil (Lens culinarismedik.) under rainfed conditions in south italy usingmulti-trait stability index (mtsi). Agronomy 11, (2021).

Olivoto, T. & Lúcio, A. D. C. Metan: an R package for multi-environment trial analysis. Methods Ecol. Evol 11, (2020).

Pacheco, A. et al. GEA-R (Genotype x Environment Analysis with R for windows) version 4.0. Cimmyt at (2016).

Lambein, F., Travella, S., Kuo, Y. H., Van Montagu, M. & Heijde, M. Grass pea (Lathyrus sativus L.): orphan crop, nutraceutical or just plain food? Planta vol. 250 at (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00425-018-03084-0

Alizadeh, K., Pooryousef, M. & Kumar, S. Bi-culturing of grass pea and barley in the semi-arid regions of Iran. Legum Res 37, (2014).

Rubiales, D., Annicchiarico, P., Vaz Patto, M. C. & Julier, B. Legume breeding for the agroecological transition of global Agri-Food systems: A European perspective. Front Plant. Sci 12, (2021).

Polignano, G. B. et al. Genotype Environment Interaction in Grass Pea (Lathyrus sativus L.) Lines. Int. J. Agron. (2009). (2009).

Chatterjee, C., Debnath, M., Karmakar, N. & Sadhukhan, R. Stability of grass pea (Lathyrus sativus L.) genotypes in different agroclimatic zone in Eastern part of India with special reference to West Bengal. Genet Resour. Crop Evol 66, (2019).

Ahmadi, J. et al. Non-parametric measures for yield stability in grass pea (Lathyrus sativus L.) advanced lines in semi warm regions. J Agric. Sci. Technol 17, (2015).

Vaezi, B. et al. Graphical analysis of forage yield stability under high and low potential circumstances in 16 grass pea (Lathyrus sativus L.) genotype. Acta Agric. Slov 119, (2023).

Garcia, S. C., Fulkerson, W. J. & Brookes, S. U. Dry matter production, nutritive value and efficiency of nutrient utilization of a complementary forage rotation compared to a grass pasture system. Grass Forage Sci 63, (2008).

Gonçalves, L., Rubiales, D., Bronze, M. R. & Vaz Patto, M. C. Grass Pea (Lathyrus sativus L.)—A Sustainable and Resilient Answer to Climate Challenges. Agronomy 12, (2022).

Ahakpaz, F. et al. Genotype-by-environment interaction analysis for grain yield of barley genotypes under dryland conditions and the role of monthly rainfall. Agric Water Manag 245, (2021).

Karimizadeh, R. et al. Identification of stable Chickpeas under dryland conditions by mixed models. Legum Sci 5, (2023).

Vinke, K. et al. Climatic risks and impacts in South asia: extremes of water scarcity and excess. Reg Environ. Chang 17, (2017).

Rodrigues, P. C., Monteiro, A. & Lourenço, V. M. A robust AMMI model for the analysis of genotype-by-environment data. Bioinformatics 32, (2016).

Dixit, G. P., Parihar, A. K., Bohra, A. & Singh, N. P. Achievements and prospects of grass pea (Lathyrus sativus L.) improvement for sustainable food production. Crop J 4, (2016).

Lee, S. Y. et al. Multi-Environment trials and stability analysis for Yield-Related traits of commercial rice cultivars. Agric 13, (2023).

Dudhe, M. Y. et al. WAASB-based stability analysis and validation of sources resistant to Plasmopara halstedii race-100 from the sunflower working germplasm for the semiarid regions of India. Genet Resour. Crop Evol 71, (2024).

Yan, W. Two types of biplots to integrate multi-trial and multi-trait information for genotype selection. Crop Sci 64, (2024).

Mohammadi, R. Genotype by yield*trait biplot for genotype evaluation and trait profiles in durum wheat. Cereal Res. Commun 47, (2019).

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully thank cooperators of the Iran grass pea performance trials.

Funding

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

B.V., and R.P., defined the experimental methodology and established the experiments, B.V., R.P. and H.H.M. collect the data, H.H.M. analyzed data and wrote the draft manuscript, R.D., G.N., S.D. and M.M. reviewed and edited the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Maleki, H.H., Vaezi, B., Pirooz, R. et al. Uncovering rain-fed resilience power of grass pea in Iran using AMMI, BLUP, and multi-trait stability parameters. Sci Rep 15, 27379 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-13756-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-13756-z