Abstract

There is no well-established model to predict the outcomes of patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma (u-HCC) receiving targeted therapy. The goal of this study was to develop and validate a prediction model that accurately predicts outcomes of patients who received targeted therapy for u-HCC. We retrospectively analyzed data from patients with u-HCC who had received targeted therapy (sorafenib or lenvatinib) between 2011 and 2023 across three centers. The clinical data from two centers were divided in a 7:3 ratio to create training and internal validation sets, respectively. While the data from the third center was used as the external validation dataset. In the training set, the variables independently associated with overall survival (OS) or progression-free survival (PFS) in multivariable analysis were alpha-fetoprotein level ≥ 20 ng/mL and macrovascular invasion (MVI). The variables were then used to develop the targeted therapy for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma prognosis (TUHP) model. In the validation set, the TUHP model was tested and compared with other prognostic model. The results showed that the TUHP model was also significantly associated with OS and PFS and exhibited greater discriminative ability than the existing prognostic models. The TUHP model accurately predicted OS and PFS among patients with u-HCC who received targeted therapy in both training and validation cohorts. The TUHP model may help optimize outcomes of patients who receive targeted therapy for u-HCC.

Similar content being viewed by others

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is a liver malignancy that is common throughout the world1,2,3. Patients with HCC are frequently diagnosed at advanced stages, making them ineligible for curative treatments such as surgery, liver transplantation, or ablation, resulting in poor outcomes4,5,6.

The management of HCC is primarily guided by the Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer (BCLC) system. Initial curative options include transplant, resection, and/or ablation for patients with BCLC 0 and A tumors. For patients with BCLC B and C tumors, the progression to palliative locoregional therapy (LRT) with or without embolization is considered7. Systemic therapy is recommended for patients ineligible for LRT or those experiencing tumor progression while on LRT8,9,10.

In 2008, sorafenib became the first tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) approved for first-line treatment11. Studies have shown that compared with placebo, sorafenib prolongs overall survival (OS) by approximately 3 months12,13. In 2018, lenvatinib was approved as an alternative first-line treatment, offering a median OS extension of approximately 3 months and a median progression-free survival (PFS) extension of approximately 5.2 months with respect to sorafenib14,15,16,17. Immunotherapy, particularly immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs), has recently emerged as a promising approach in recent years18. Atezolizumab plus bevacizumab and durvalumab plus tremelimumab remain the treatment of choice among all ICIs containing regimens19. The integration of immunotherapy into HCC treatment has significantly advanced, particularly through combination approaches. However, major challenges, including biomarker discovery, immune resistance, and toxicity management, must be addressed20,21,22. Despite lenvatinib and sorafenib no longer being first line therapies for uHCC, we do still use them and they still have a role. There are patients who do not tolerate immunotherapy or ICIs, patients who are ineligible due to being post-transplant or having autoimmune conditions, etc. Therefore, it is still important for us to understand who will respond best to these targeted therapies. According to research and clinical data, approximately 20–30% of patients with HCC do not experience substantial clinical benefits after receiving systemic therapy23possibly due to insensitivity to treatment or the development of resistance. Thus, identifying this portion of patients prior to the start of targeted therapy and preventing them from experiencing treatment failure would prove clinically beneficial.

The wide range of survival times is inadequately captured by the currently available staging systems (i.e., the BCLC or Chinese Liver Cancer (CNLC) system)24,25,26. Therefore, we need to explore additional systems to stratify patients with intermediate- or advanced-stage HCC. Several scoring systems have been proposed that combine baseline factors, including the Prediction of Survival in Advanced Sorafenib-Treated Hepatocellular Carcinoma-II (PROSASH-II) system for the survival stratification of patients with HCC undergoing targeted therapy and the Hepatoma Arterial Embolization Prognostic system (HAP) system for the survival stratification of patients with HCC undergoing transarterial chemoembolization (TACE)27,28. However, these models are limited by the use of factors that either have a certain degree of subjectivity or are not commonly available, among others29,30.

Therefore, the aim of this study was to (I) create a simplified model for predicting the outcomes of patients with unresectable HCC (u-HCC) undergoing targeted therapy; (II) validate this targeted therapy for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma prognosis (TUHP) model in patients with u-HCC treated with targeted therapy in daily clinical practice; and (III) compare the TUHP and existing prognostic models to determine their utility for clinicians in predicting the survival of patients treated in clinical practice.

Materials and methods

Patients and study design

We retrospectively reviewed data on u-HCC patients initially treated with first-line targeted therapy at three centers: the Affiliated Cancer Hospital and Institute of Guangzhou Medical University (ACHIGMU) and the First Affiliated Hospital of Jinan University (FAHJU) and the Hunan Provincial People’s Hospital (HPPH) between January 2011 and March 2023. Patients were included if they met the following inclusion criteria: (I) a diagnosis of intermediate to advanced u-HCC or pathologically confirmed HCC; (II) initial treatment with targeted therapy at the respective hospital without prior antitumor treatment; (III) no history of other malignancies; (IV) no prior systemic antitumor therapy (e.g., chemotherapy, immunotherapy); (V) no previous local treatments (e.g., radiofrequency ablation, interventional therapy); (VI) treatment with targeted therapy for a minimum of 4 weeks, followed by an efficacy assessment; (VII) complete clinical and follow-up data; and (VIII) age at diagnosis > 18 years. TKIs was indicated for patients with unresectable HCC meeting the following criteria: (1) Child-Pugh A/B7 liver function; (2) ECOG PS 0–2; (3) radiologically confirmed intermediate/advanced HCC (BCLC B/C or CNLC IIb/III); (4) no prior systemic therapy; and (5) absence of contraindications to TKIs (e.g., uncontrolled hypertension, bleeding risk). After receiving the targeted therapy (sorafenib or lenvatinib), patients were monitored for disease progression and potential complications. Subsequent treatments, including the use of immunotherapy (e.g., immune checkpoint inhibitors such as pembrolizumab, nivolumab, atezolizumab), were administered based on clinical decisions and the patient’s disease progression. The choice of treatment was guided by the patient’s condition, response to the initial therapy, and available treatment options. Immunotherapy, when used, was incorporated as part of second-line or salvage treatment strategies for patients with advanced disease or progression after targeted therapy. We confirmed that all subjects have obtained informed consent. The research protocols received ethical approval from the Affiliated Cancer Hospital, Guangzhou Medical University (GYZL-ZN039). We guaranteed the privacy of patient information, and the data access procedures conform to the data and privacy regulations of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Demographic information, clinical characteristics, and outcome data were collected from the patients’ electronic medical records. This included sex, age, body mass index (BMI), Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status (ECOG PS), history of hepatitis, family history of tumor, history of cirrhosis of the liver, maximum tumor diameter, number of tumors, imaging data, macrovascular invasion (MVI), organ involvement (It was defined as the presence of HCC metastasis to distant organs, including but not limited to the lungs, bones, adrenal glands, or peritoneum, as confirmed by imaging studies or pathological diagnosis), lymph node invasion, alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) level, and Child-Pugh score. Patients were then classified into different risk levels according to the BCLC, CNLC, HAP, and PROSASH-II results.

Model establishment and validation

Variables identified as significant factors associated with survival in univariable Cox analysis were selected for multivariable Cox proportional hazards regression analysis using the forward stepwise conditional logistic regression (LR) method to identify the independent predictive factors. The screened factors were then introduced into the LR equation to calculate the predictive probability of a particular outcome and draw the corresponding receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve. The TUHP and existing prognostic models with different coefficients for the same factors were obtained through Cox survival analysis, corresponding to the separate analyses for OS and PFS. The discriminatory ability of the new models in the internal validation cohort was compared to four existing HCC staging systems (BCLC, CNLC, HAP, and PROSASH-II) through ROC curve analysis31specifically by calculating and comparing the area under the curve (AUC) and the Harrell concordance index (C-index). The Hosmer-Lemeshow test was used to assess the goodness of fit of the models, and decision curve analysis (DCA) was used to evaluate the net clinical benefits of the model. The external validation cohort was then compared using Kaplan-Meier curves for the TUHP models.

Definitions and follow-up

According to the modified Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (mRECIST)32,33treatment response is categorized into four groups: complete response (CR), partial response (PR), stable disease (SD), and progressive disease (PD)34. OS was defined as the time between when the patient began targeted therapy and the last follow-up or death from any cause. PFS was defined as the time between when the patient started targeted therapy and disease progression, relapse, or death from any cause. OS data were gathered from medical records and follow-up examinations. The treatment response for each patient was evaluated 4–8 weeks after starting treatment. Follow-up visits were scheduled every 3–6 months during treatment until death or loss to follow-up.

Statistical analysis

The Kruskal-Wallis analysis of variance (ANOVA) test or t-test was used to compare continuous data between groups, while the χ2 test was employed for between-group comparisons of discrete data. Survival curves were generated using the Kaplan-Meier method, and differences between the curves were assessed using the log-rank test. Statistical Methods for Time-Dependent ROC Analysis: We employed the Kaplan-Meier method to estimate the survival probabilities and the Inverse Probability of Censoring Weighting (IPCW) approach to adjust for censoring. The IPCW method assigns weights to uncensored observations based on the probability of being censored, ensuring that the AUC calculations are not biased by the presence of censored data. AUC Calculations: The AUC values were calculated using the time ROC package in R software ( https://www.r-project.org/, R-4.4.0 for Windows), which implements the IPCW method for time-dependent ROC analysis. The AUC values at 1-year, 2-year, and 3-year time points were reported along with their corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CI). The Cox proportional hazards model was applied for both univariable and multivariable analyses, with the hazard ratio (HR) and 95% CI calculated. The CI for AUC were determined using the bootstrap method with 1000 resamples to provide a reliable estimate of the model’s performance. Optimal cutoff values were determined using X-tile 3.6.1 software. Statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS version 25.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA), Adobe Illustrator (Adobe, San Jose, CA, USA), GraphPad Prism 9 (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA, USA), and R software. Statistically significances was defined as p < 0.05.

Results

Baseline patient characteristics

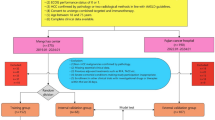

A total of 272 patients initially treated with first-line targeted therapy for u-HCC were included for this study between January 2011 and March 2023. Among them, 171 consecutive patients incenters (ACHIGMU and FAHJU) were included and randomly allocated to a training cohort (n = 120) and an internal validation cohort (n = 51) in a ratio of 7:3. In addition, 101 u-HCC patients initially treated with first-line targeted therapy from another tertiary institutions (HPPH) between October 2011 and September 2020 were enrolled retrospectively and served as the external validation cohort (n = 101). The flow chart of patient selection is presented in Fig. 1. The final cohort distribution was: training cohort 120 patients (44%), internal validation 51 patients (19%), and external validation 101 patients (37%). The baseline characteristics of both the training cohort, the internal and external validation cohort are presented in Table 1. The training cohort and the internal validation cohort demonstrated similar baseline features without statistically significant difference. The median OS was 13.25 months (95% CI 14.88–18.19) in all patients, and the median PFS was 4.75 months (95% CI 7.77–10.42).

Independent prognostic factors in the training cohort

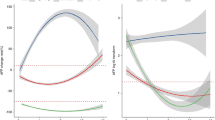

Univariable and multivariable analyses of OS and PFS were performed in the training cohort, as presented in Table 2. All significant factors (p < 0.05) identified in the univariable analysis were included in the multivariable analysis using a Cox regression model. The results indicated that MVI, Child-Pugh score, AFP level, BCLC grade, and CNLC grade were associated with OS in the univariable analyses, while MVI, tumor differentiation, preoperative AFP, albumin, bilirubin, and liver segment invasion were linked to PFS. Subsequent multivariable analysis revealed that MVI and AFP level were independent risk factors for both OS and PFS. Figures 2 and 3 display the 1, 2, 3 years OS and PFS AUC curves, respectively, stratified by the values of these predictive factors.

AUCs at 1, 2, and 3 years of the A TUHP OS model and the B BCLC, C CNLC, D HAP, and E PROSASH-II systems for OS. TUHP targeted therapy for unresectable hepatocellular prognosis, OS overall survival, AUC area under the curve, CI confidence interval, BCLC Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer, CNLC Chinese Liver Cancer, HAP Hepatoma Arterial Embolization Prognostic system, PROSASH-II Prediction of Survival in Advanced Sorafenib-Treated Hepatocellular Carcinoma-II.

AUCs at 1, 2, and 3 years of the A TUHP PFS model and the B BCLC, C CNLC, D HAP, and E PROSASH-II systems for PFS. TUHP targeted therapy for unresectable hepatocellular prognosis, PFS progression-free survival, AUC area under the curve, CI confidence interval, BCLC Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer, CNLC Chinese Liver Cancer, HAP Hepatoma Arterial Embolization Prognostic system, PROSASH-II Prediction of Survival in Advanced Sorafenib-Treated Hepatocellular Carcinoma-II.

Construction of novel outcome prediction models in the training cohort

We subsequently developed two novel prognostic models for OS and PFS, known as the TUHP OS model and the TUHP PFS model, respectively. These models were based on two independent risk factors, MVI and elevated AFP level, and used to calculate the corresponding patient risk scores. Cox proportional hazards regression analysis was performed to evaluate the associations between survival and these independent factors in the training dataset. To calculate the risk score for each patient, we used the following formulas derived from the multivariable Cox regression model:

Risk score of the TUHP OS model = (0.706 × MVI) + (1.183 × elevated AFP), Risk score of the TUHP PFS model = (0.621 × MVI) + (1.073 × elevated AFP). Using X-tile analysis (Fig. 4), we stratified the patients into three risk groups according to their TUHP OS and PFS model risk scores.

X-tile output for the cutoff values of the TUHP OS model and TUHP PFS model. The optimal cutoff values indicated on the x-axis in the upper panels. Specific values are displayed in histograms in the middle panels, and the predictions of the different models are plotted in the bottom panels. A, C, E The data for the TUHP OS model. B, D, F The data for the TUHP PFS model. TUHP targeted therapy for unresectable hepatocellular prognosis, OS overall survival, PFS progression-free survival.

Performance of the model in stratifying patient risk

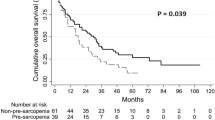

In the training cohort, there were 95 deaths out of 120 patients. In the internal validation cohort, there were 40 deaths out of 51 patients, and in the external validation cohort, there were 45 deaths out of 101 patients. In the training cohort, there were 110 progression events out of 120 patients. In the internal validation cohort, there were 46 progression events out of 51 patients, and in the external validation cohort, there were 85 progression events out of 101 patients (Fig. 5). We determined the cutoff values by evenly grouping the patients in the training cohort into three subgroups based on their total risk scores after sorting. The TUHP OS model effectively stratified patients into low-risk (score 0–0.706), medium-risk (score 1.183), and high-risk (score 1.889) survival groups (p < 0 0.001) (Fig. 5A). Similarly, the TUHP PFS model accurately stratified patients into low-risk (score 0–0.647), medium-risk (score 1.033), and high-risk (score 1.68) disease progression groups (P < 0.001) (Fig. 5B). These findings were consistent in both the internal (Fig. 5C, D) and external validation cohorts (Fig. 5E, F).

The risk of the TUHP OS and PFS models in stratifying patient. Kaplan-Meier curves for the A OS and D PFS of patients in the training set. Kaplan-Meier curves for the B OS and E PFS of patients in the internal validation. Kaplan-Meier curves for the C OS and F PFS of patients in the external validation cohort. OS overall survival, CI confidence interval, PFS progression-free survival.

Comparative performance of the conventional systems

We compared the predictive ability of the TUHP OS and TUHP PFS models with that of four existing HCC staging systems (BCLC, CNLC, HAP, and PROSASH-II) in terms of the AUC and C-index. The proposed models displayed superior discriminatory power in both internal and external validation cohort compared with the competing models.

In the internal validation cohort, for OS, the AUC of the proposed model was 0.813 (95% CI: 0.693–0.932), compared to 0.536 (95% CI: 0.338–0.734) for BCLC, 0.514 (95% CI: 0.322–0.705) for CNLC, 0.673 (95% CI: 0.501–0.845) for HAP, and 0.653 (95% CI: 0.486–0.821) for PROSASH-II (Fig. 6A). The C-index values were 0.759 for the TUHP PFS model, and 0.565, 0.576, 0.633, and 0.681 for the BCLC, CNLC, HAP, and PROSASH-II systems, respectively (Fig. 6B). For PFS, the AUC of the proposed model was 0.783 (95% CI: 0.635–0.932), versus 0.661 (95% CI: 0.406–0.916) for BCLC, 0.687 (95% CI: 0.479–0.896) for CNLC, 0.637 (95% CI: 0.418–0.856) for HAP, and 0.620 (95% CI: 0.392–0.849) for PROSASH-II (Fig. 6C). The C-index values were 0.750 for the TUHP PFS model, and 0.568, 0.578, 0.612, and 0.653 for the BCLC, CNLC, HAP, and PROSASH-II systems, respectively (Fig. 6D).

Predictions of the TUHP OS and PFS models. Comparisons of the A AUCs and B C-indices of the different risk stratification models for OS in internal the validation cohort, as well as comparisons of the C AUCs and D C-indices of the different risk stratification models for PFS in the internal validation cohort. In all figures, the AUC and C-index values of the TUHP models are the highest. ROC receiver operating characteristic, AUC area under the curve, CI confidence interval, TUHP targeted therapy for unresectable hepatocellular prognosis, BCLC Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer, CNLC Chinese Liver Cancer, HAP Hepatoma Arterial Embolization Prognostic system, PROSASH-II Prediction of Survival in Advanced Sorafenib-Treated Hepatocellular Carcinoma-II, C-index concordance index, OS overall survival, PFS progression-free survival.

In the external validation cohort, for OS, the AUC of the proposed model was 0.688 (95% CI: 0.583–0.792), compared to 0.500 (95% CI: 0.386–0.614) for BCLC, 0.500 (95% CI: 0.386–0.614) for CNLC, 0.641 (95% CI: 0.531–0.751) for HAP, and 0.610 (95% CI: 0.500–0.719) for PROSASH-II (Fig. 7A). The C-index values were 0.763 for the TUHP PFS model, and 0.500, 0.500, 0.618, and 0.591 for the BCLC, CNLC, HAP, and PROSASH-II systems, respectively (Fig. 7B). For PFS, the AUC of the proposed model was 0.748 (95% CI: 0.632–0.865), versus 0.500 (95% CI: 0.345–0.655) for BCLC, 0.500 (95% CI: 0.345–0.655) for CNLC, 0.505 (95% CI: 0.353–0.657) for HAP, and 0.538 (95% CI: 0.373–0.702) for PROSASH-II (Fig. 7C). The C-index values were 0.698 for the TUHP PFS model, and 0.500, 0.500, 0.544, and 0.539 for the BCLC, CNLC, HAP, and PROSASH-II systems, respectively (Fig. 7D).

Predictions of the TUHP OS and PFS models. Comparisons of the A AUCs and B C-indices of the different risk stratification models for OS in the external validation cohort, as well as comparisons of the C AUCs and D C-indices of the different risk stratification models for PFS in the external validation cohort. In all figures, the AUC and C-index values of the TUHP models are the highest. ROC receiver operating characteristic, AUC area under the curve, CI confidence interval, TUHP targeted therapy for unresectable hepatocellular prognosis, BCLC Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer, CNLC Chinese Liver Cancer, HAP Hepatoma Arterial Embolization Prognostic system, PROSASH-II Prediction of Survival in Advanced Sorafenib-Treated Hepatocellular Carcinoma-II, C-index concordance index, OS overall survival, PFS progression-free survival.

The AUCs of the different predictive risk models at 1, 2, and 3 years for OS and PFS in the internal validation cohort were compared (Fig. 8A, B). Additionally, the AUCs of each prognostic risk model in the validation cohort for OS and PFS at 1, 2, and 3 years are displayed in Tables 3 and 4, as well as Figs. 2 and 3. Furthermore, the Hosmer-Lemeshow test demonstrated that the model outputs demonstrated good fits (TUHP OS model: p = 0.44; TUHP PFS model: p = 0.57), and DCA showed that the proposed predictive models conferred significant net benefits for the entire cohort (Fig. 8C, D).

Comparisons of the AUCs of the different predictive models at 1, 2, and 3 years for A OS and B PFS in the validation cohort. DCA of the models in predicting C OS and D PFS in the entire cohort. TUHP targeted therapy for unresectable hepatocellular prognosis, OS overall survival, PFS progression-free survival; BCLC Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer, CNLC Chinese Liver Cancer, HAP Hepatoma Arterial Embolization Prognostic system, PROSASH-II Prediction of Survival in Advanced Sorafenib-Treated Hepatocellular Carcinoma-II, AUC area under the curve, PFS progression-free survival, DCA decision curve analysis.

Discussion

HCC, accounting for over 80% of primary liver cancers, is a major global health concern. In recent years, significant advancements have been made in the management of advanced liver cancer, resulting in improved patient outcomes. These improvements can be attributed to the approval of posttreatment drugs such as sorafenib and the emergence of ICIs35. Currently, the combination of the programmed cell death-Ligand 1 inhibitor atezolizumab with bevacizumab is also considered the first-line treatment for advanced HCC36. Despite technological advancements that have revolutionized HCC treatment, the long-term outcomes for patients, particularly those with u-HCC, are still unsatisfactory37.

The BCLC and CNLC staging systems are commonly used as prognostic models for HCC. However, these models have limitations and offer limited value for patients undergoing targeted therapy. Studies have shown that the HAP, SAP, and PROSASH-II scores outperform the BCLC and CNLC scores for patients receiving targeted therapy29. The HAP score was initially developed to stratify HCC patients undergoing TACE treatment, considering factors like albumin, bilirubin, AFP levels, and tumor size38,39. On the other hand, the SAP system predicts the outcomes for advanced HCC patients treated with sorafenib and includes an additional ECOG PS score criterion. Previous studies have shown that the HAP system provides better predictive performance than the SAP system for patients treated with sorafenib, leading to its inclusion for comparison in our study31,40. The PROSASH-II score involves complex calculations incorporating albumin level, bilirubin level, MVI, extrahepatic spread, maximum tumor size, and AFP level29. However, due to a lack of consensus, limited applicability, and minimal external validation, the practical use of these prognostic scores in clinical settings remains challenging. In this study, our risk stratification models were found to have superior predictive accuracy compared to those of the BCLC, CNLC, HAP, and PROSASH-II systems, as demonstrated in the comparisons of the C-indices and AUCs. These models were internally validated in the training cohort for survival prediction and risk stratification, showing strong performance and practicality. Additionally, the models demonstrated better risk stratification performance than conventional models in the external validation cohort.

One advantage of this study was the inclusion of a homogeneous population of patients with u-HCC who received targeted therapy without prior surgical procedures, TACE, radiofrequency ablation, or other local treatments. This significantly reduced potential confounding factors affecting the survival analysis. Another advantage of this study was the development of a simplified, cost-effective, and non-invasive approach to stratifying patients based on their risk levels before starting targeted therapy. The AFP level and MVI were identified through multivariate analysis as independent risk factors associated with OS and PFS. These factors are well-known risk factors associated with long-term survival and recurrence in HCC41,42,43,44. Both the AFP level and MVI are clinical laboratory indicators that can be obtained before treatment, making them more cost-effective and feasible in clinical practice compared to genetic sequencing, immune environment monitoring, and other tests. AFP is a widely used serum biomarker in the management of HCC and is the only biomarker currently used for guiding treatment decisions for the disease45,46. In addition to promoting tumor growth, AFP may hinder antitumor immunity by inhibiting T-lymphocyte proliferation, suppressing natural-killer-cell activity and dendritic cell differentiation, and increasing T-regulatory-cell activity. Another key prognostic factor for HCC is MVI, a condition observed in 15–57.1% of patients with this disease47,48. Several studies have reported a positive correlation between tumor diameter and the likelihood of MVI49. Therefore, due to the high rate of MVI positivity, patients with HCC may have a greater risk of recurrence and poorer outcomes50. These factors are risk factors associated with long-term survival and recurrence in HCC41,42,43. Unlike many existing prognostic models, which rely on complex genetic testing or expensive diagnostic methods, the TUHP model uses clinical markers such as AFP and MVI, which are easily obtained in routine clinical practice. This accessibility makes the TUHP model particularly valuable, especially in regions with limited healthcare resources.

Despite the promising results, there are significant knowledge gaps that need to be addressed. It should be noted that while the TUHP model was primarily developed for patients with unresectable HCC receiving targeted therapy (sorafenib or lenvatinib), the risk factors employed in the model (AFP levels and MVI) are established prognostic indicators for HCC that may also have predictive value for patients undergoing other treatment modalities, including best supportive care. The targeted therapy regimens included in this study did exhibit some heterogeneity (sorafenib vs. lenvatinib), which may introduce variability in the prediction outcomes. Although both drugs are multi-kinase inhibitors with similar mechanisms of action, future studies should develop prediction models specifically tailored to individual targeted therapies to enhance precision. Therefore, molecular profiling and the discovery of new biomarkers will be critical in refining this model and increasing its precision. Due to the retrospective nature and relatively small sample size of this study, especially in external validation cohorts, a high proportion of organ involvement may reflect the nature of the cohort, including late stage disease patients who are more likely to have extensive organ involvement. This potential selection bias may affect the validation results and limit the generalizability of the model. The second-line treatment strategies showed significant variations across cohorts. This may partially explain the improved survival outcomes observed in the external cohort. Future studies should further evaluate the modifying effects of second-line treatments on the prognostic model. In further clinical validation, we will provide a more thorough examination of how the potential selection bias in both the internal and external validation cohorts may affect the generalizability of our findings. We will discuss how our model may perform differently in populations with less advanced disease or those without organ involvement. Meanwhile, to enhance the robustness and applicability of the TUHP model, prospective, multicenter studies involving larger and more diverse patient populations are necessary. Furthermore, incorporating emerging treatment modalities such as ICIs into future studies will be crucial for determining how well the TUHP model works alongside these therapies.

Looking ahead, the next five years could bring about significant developments in the field of HCC prognosis and treatment. The future of precision oncology will depend on the integration of multiple biomarkers, clinical data, and real-time patient monitoring. Understanding how to combine models like TUHP with newer treatments will be essential to improving survival and quality of life for patients with liver cancer. We can expect prognostic models like TUHP to evolve into dynamic systems that adjust predictions in real time based on new patient data, such as treatment response or genetic profiles. This could lead to even more personalized treatment decisions. Additionally, artificial intelligence and big data analysis are expected to play a critical role in enhancing the accuracy of predictive models.

In conclusions, the TUHP model represents a valuable advancement in predicting outcomes for u-HCC patients undergoing targeted therapy. By utilizing commonly available clinical markers such as AFP and MVI, the model offers an easy-to-implement, cost-effective tool for predicting the OS and PFS of patients with u-HCC receiving targeted therapy. The next steps involve validating this model in larger-scale studies and integrating it with emerging therapies, particularly immune checkpoint inhibitors, to further enhance its predictive power.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to proprietary restrictions, but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Yang, C. et al. Evolving therapeutic landscape of advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. NAT. REV. GASTRO HEPAT. 20, 203–222. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41575-022-00704-9 (2022).

Sung, H. et al. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA-CANCER J. CLIN. 71, 209–249. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21660 (2021).

Vitale, E., Rizzo, A., Santa, K. & Jirillo, E. Associations between cancer risk. Inflamm. Metabolic Syndrome: Scoping Rev. Biology (Basel). 13, 352. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology13050352 (2024).

Brown, Z. J. et al. Management of hepatocellular carcinoma: A review. JAMA SURG. 158, 410–420. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamasurg.2022.7989 (2023).

Llovet, J. M. et al. Finn, RS. Hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers. 7, 6. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41572-020-00240-3 (2021).

Bas, O., Sahin, T. K., Karahan, L., Rizzo, A. & Guven, D. C. Prognostic significance of the cachexia index (CXI) in patients with cancer: A systematic review and Meta-Analysis. Clin. Nutr. ESPEN. 83, e852–e865. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clnesp (2025).

Rizzo, A., Ricci, A. D. & Brandi, G. Trans-Arterial chemoembolization plus systemic treatments for hepatocellular carcinoma: an update. J. Pers. Med. 12 https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm12111788 (2022).

Fong, K. Y. et al. First-Line systemic therapies for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: A systematic review and Patient-Level network Meta-Analysis. LIVER CANCER. 12, 7–18. https://doi.org/10.1159/000526639 (2022).

Lim, H. et al. Optimizing survival and the changing landscape of targeted therapy for intermediate and advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: A systematic review. JNCI-J NATL. CANCER I. 113, 123–136. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/djaa119 (2021).

Gordan, J. D. et al. Rose, MG. Systemic therapy for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: ASCO guideline. J. CLIN. ONCOL. 38, 4317–4345. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.20.02672 (2020).

Meyers, B. M. et al. The evolution of immune checkpoint inhibitor combinations in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma - A systematic review. CANCER TREAT. REV. 118, 102584. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ctrv.2023.102584 (2023).

Villanueva, A. & Llovet, J. M. Targeted therapies for hepatocellular carcinoma. GASTROENTEROLOGY 140, 1410–1426. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2011.03.006 (2011).

Kodama, K. et al. Correlation between early tumor marker response and imaging response in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma treated with lenvatinib. ONCOLOGY-BASEL 97, 75–81. https://doi.org/10.1159/000499715 (2019).

Kudo, M. et al. Overall survival and objective response in advanced unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: a subanalysis of the REFLECT study SSRN. J. Hepatol. 78(1), 133–141. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3523871 (2020).

Shimose, S. et al. Torimura, T. Clinical significance of adverse events for patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma treated with lenvatinib: a multicenter retrospective study. Cancers (Basel). 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers12071867 (2020).

Nair, A. et al. FDA supplemental approval summary: lenvatinib for the treatment of unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. ONCOLOGIST 26, e484–e491. https://doi.org/10.1002/onco.13566 (2020).

Zhao, Y., Zhang, Y. N., Wang, K. T. & Chen, L. Lenvatinib for hepatocellular carcinoma: from preclinical mechanisms to anti-cancer therapy. BBA-REV CANCER. 1874, 188391. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbcan.2020.188391 (2020).

Rizzo, A. et al. Predictive biomarkers for checkpoint Inhibitor-based immunotherapy in hepatocellular carcinoma: where do we stand?? Front. Oncol. 11, 803133 https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2021.803133 (2021).

Sho, T. et al. Efficacy and safety of durvalumab/tremelimumab in unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma as immune checkpoint inhibitor Rechallenge following atezolizumab/bevacizumab treatment. TARGET. ONCOL. 19, 769–778. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11523-024-01092-7 (2024).

Rizzo, A. & Ricci, A. D. Challenges and future trends of hepatocellular carcinoma immunotherapy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms231911363 (2022). 23.

Guven, D. C. et al. Immune checkpoint inhibitor-related hearing loss: a systematic review and analysis of individual patient data. SUPPORT CARE CANCER. 31, 624. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-023-08083-w (2023).

Sahin, T. K., Ayasun, R., Rizzo, A. & Guven, D. C. Prognostic value of Neutrophil-to-Eosinophil ratio (NER) in cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancers (Basel). 16(21), 3689. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers16213689 (2024).

Kobayashi, K. et al. Evolution of survival impact of molecular target agents in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. LIVER CANCER. 11, 48–60. https://doi.org/10.1159/000519868 (2021).

Li, X. et al. Development of a multivariate prognostic model for lenvatinib treatment in hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncologist 28, e942–e949 https://doi.org/10.1093/oncolo/oyad107 (2023).

Bolondi, L. et al. Heterogeneity of patients with intermediate (BCLC B) hepatocellular carcinoma: proposal for a subclassification to facilitate treatment decisions. SEMIN LIVER DIS. 32, 348–359. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0032-1329906 (2013).

Weinmann, A. et al. Survival analysis of proposed BCLC-B subgroups in hepatocellular carcinoma patients. LIVER INT. 35, 591–600. https://doi.org/10.1111/liv.12696 (2014).

Wang, Z. et al. Exploratory analysis to identify candidates benefitting from combination therapy of transarterial chemoembolization and Sorafenib for First-Line treatment of unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: A multicenter retrospective observational study. LIVER CANCER. 9, 308–325. https://doi.org/10.1159/000505692 (2020).

Berhane, S., Fox, R., García-Fiñana, M., Cucchetti, A. & Johnson, P. Using prognostic and predictive clinical features to make personalised survival prediction in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma patients undergoing Sorafenib treatment. BRIT J. CANCER. 121, 117–124. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41416-019-0488-4 (2019).

Labeur, T. A. et al. Improved survival prediction and comparison of prognostic models for patients with hepatocellular carcinoma treated with Sorafenib. LIVER INT. 40, 215–228. https://doi.org/10.1111/liv.14270 (2019).

Guo, D. Z. et al. Prognostic model for predicting outcome and guiding treatment decision for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma treated with lenvatinib monotherapy or lenvatinib plus immunotherapy. Front. Immunol. 14, 1141199. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2023.1141199 (2023).

Edeline, J. et al. Prognostic scores for sorafenib-treated hepatocellular carcinoma patients: A new application for the hepatoma arterial embolisation prognostic score. EUR. J. CANCER. 86, 135–142. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejca.2017.08.036 (2017).

Lencioni, R., Llovet, J. M. & Modified RECIST (mRECIST) assessment for hepatocellular carcinoma. SEMIN LIVER DIS. 30, 52–60. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0030-1247132 (2010).

Lencioni, R. et al. Objective response by mRECIST as a predictor and potential surrogate end-point of overall survival in advanced HCC. J. HEPATOL. 66, 1166–1172. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2017.01.012 (2017).

Bruix, J., Reig, M. & Sangro, B. Assessment of treatment efficacy in hepatocellular carcinoma: response rate, delay in progression or none of them. J. HEPATOL. 66, 1114–1117. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2017.02.032 (2017).

Rimassa, L., Finn, R. S. & Sangro, B. Combination immunotherapy for hepatocellular carcinoma. J. HEPATOL. 79, 506–515. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2023.03.003 (2023).

Yu, S. J. Immunotherapy for hepatocellular carcinoma: recent advances and future targets. PHARMACOL. THERAPEUT. 244, 108387. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pharmthera.2023.108387 (2023).

EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines. Management of hepatocellular carcinoma. J. HEPATOL. 69, 182–236. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2018.03.019 (2018).

Kadalayil, L. et al. Meyer, T. A simple prognostic scoring system for patients receiving transarterial embolisation for hepatocellular cancer. ANN. ONCOL. 24, 2565–2570. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdt247 (2013).

Pinato, D. J. et al. Validation of the hepatoma arterial embolization prognostic score in European and Asian populations and proposed modification. CLIN. GASTROENTEROL. H. 13, 1204–8e2. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cgh.2014.11.037 (2014).

Pinato, D. J., Howell, J., Ramaswami, R. & Sharma, R. Review article: delivering precision oncology in intermediate-stage liver cancer. ALIMENT. PHARM. Th. 45, 1514–1523. https://doi.org/10.1111/apt.14066 (2017).

Bruix, J. et al. Prognostic factors and predictors of Sorafenib benefit in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma: analysis of two phase III studies. J. HEPATOL. 67, 999–1008. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2017.06.026 (2017).

Giannini, E. G. et al. Trevisani, F. Patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma need a personalized management: A lesson from clinical practice. HEPATOLOGY 67, 1784–1796. https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.29668 (2018).

Hsu, W. F. et al. Alpha-fetoprotein response predicts treatment outcomes in patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma receiving immune checkpoint inhibitors with or without tyrosine kinase inhibitors or locoregional therapies. Am. J. Cancer Res. 11, 6173–6187 (2021).

Chou, W. C. et al. Chia-Hsun hsieh, J. Changes in serum α-fetoprotein level predicts treatment response and survival in hepatocellular carcinoma patients and literature review. J. FORMOS. MED. ASSOC. 117, 153–163. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfma.2017.03.010 (2017).

Yau, T. et al. The significance of early alpha-fetoprotein level changes in predicting clinical and survival benefits in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma patients receiving Sorafenib. ONCOLOGIST 16, 1270–1279. https://doi.org/10.1634/theoncologist.2011-0105 (2011).

Welland, S. et al. Vogel, A. Real-World data for lenvatinib in hepatocellular carcinoma (ELEVATOR): A retrospective multicenter study. LIVER CANCER. 11, 219–232. https://doi.org/10.1159/000521746 (2022).

Lyu, N. et al. Arterial chemotherapy of oxaliplatin plus fluorouracil versus Sorafenib in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: A biomolecular exploratory, randomized, phase III trial (FOHAIC-1). J. CLIN. ONCOL. 40, 468–480. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.21.01963 (2021).

Chen, W. et al. Cancer statistics in china, 2015. CA-CANCER J. CLIN. 66, 115–132. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21338 (2016).

Sohn, W. et al. Sorafenib therapy for hepatocellular carcinoma with extrahepatic spread: treatment outcome and prognostic factors. J. HEPATOL. 62, 1112–1121. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2014.12.009 (2014).

Krishnan, M. S. et al. Dhanasekaran, R. Genomic analysis of vascular invasion in HCC reveals molecular drivers and predictive biomarkers. HEPATOLOGY 73, 2342–2360. https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.31614 (2021).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank reviewers for the insightful comments on the manuscript. Technical support provided by the imaging team is gratefully acknowledged.

Funding

The research activities described in this study were primarily supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 82203844, 82203213, and 81911530169), the CQMU Program for Youth Innovation in Future Medicine (No. W0202), the Talent Program of Chongqing Health Commission, Chongqing Science and Technology Bureau (Nos. CSTB2022NSCQ-MSX0227 and cstc2022jxjl120022), the Basic and Applied Basic Research Project of Guangdong Province (No. 2020A1515111201), the Science and Technology Research Program of Chongqing Municipal Education Commission (No. KJZD-K202300408), the Municipal and University (Hospital) Joint Funding Project of Guangzhou Municipal Science and Technology Bureau (No. 2023A03J0796), and the Guangdong Yiyang Healthcare Charity Foundation (No. JZ2024028).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Q.R. and Y.C. Writing-original draft; X.W. and Q.L. Software; Y.T. and Y.X. Investigation ; H.Y. Formal analysis; H.Z. Methodology; J.L. Validation; D.Y. Project administration; Q.R. and L.W. Funding acquisition; All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ruan, Q., Wang, X., Li, Q. et al. Outcome prediction model for patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma treated with targeted therapy. Sci Rep 15, 29608 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-13799-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-13799-2