Abstract

With the advancement of the rural revitalization strategy, traditional villages are facing both opportunities and challenges for development. Tourism development is considered an effective means of preserving and utilizing traditional villages, and assessing the potential of village locations is crucial for decision-makers in formulating reasonable tourism development plans. Sichuan Province has 396 national-level traditional villages, but the distribution patterns and location potential across various spatial scales need further exploration. This study uses kernel density and nearest neighbor methods for spatial analysis and discovers for the first time that the traditional villages in Sichuan Province exhibit a “Six Cores and Five Belts” spatial distribution characteristic, with different aggregation patterns observed at the provincial, regional, and city scales. This study selects 25 indicators from five dimensions—natural environment, location and transportation, socio-economics, tourism market, and policy support—to construct a multi-indicator evaluation system for the comprehensive and quantitative assessment of the Location Potential for Tourism Development (LPTD) of traditional village. The research results show that the LPTD of traditional villages in Sichuan can be divided into three levels: high, medium, and low. High-potential villages (LPTD > 0.4047) are located in the Sichuan Basin, with high economic development levels, large population densities, convenient transportation, and favorable location conditions. Medium-potential villages (0.2523 < LPTD ≤ 0.4047) are distributed along the edges of the basin and central Ganzi Prefecture. Low-potential villages (LPTD ≤ 0.2523) are mostly found in the northern part of northwest Sichuan, the northern part of northeast Sichuan, and the Panxi area, with low economic development levels and weak transportation infrastructure. Through spatial autocorrelation and gravity model analysis, the location potential shows significant positive spatial autocorrelation at the provincial (Moran’s I = 0.6721) and regional (Moran’s I = 0.5386) scales, with a “Hot area” in the Sichuan Basin and two “Cold areas” in northwest Sichuan and the Panxi region. Three strong gravity areas are formed in the Chengdu Plain and southern Sichuan. Using spatially constrained multivariate clustering, the traditional villages in Sichuan are classified into four types: tourism-based, resource-based, ecology-based, and transportation-based. These findings fill the gap in the spatial understanding of the LPTD of traditional villages in Sichuan Province for the first time. Based on these findings, this paper proposes tourism development strategies for traditional villages from the perspective of location potential, aiming to promote the preservation, utilization, and sustainable development of traditional villages in Sichuan Province. The methodology of this study can be applied to other traditional village clusters worldwide, and the findings provide valuable insights for the protection and sustainable development of traditional villages globally.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In recent years, traditional villages worldwide have faced numerous challenges. In Spain’s Galicia and Italy’s Alpine regions, many villages have experienced economic and cultural decline, or even abandonment, due to population migration and the impact of modernization. Villages in Provence, France, are grappling with the breakdown of cultural and social structures as they lack a young labor force. In Nepal, high-altitude villages are witnessing the gradual disappearance of traditional agriculture and lifestyles due to climate change. In China, despite receiving policy support under the rural revitalization strategy, traditional villages still struggle with insufficient infrastructure and delayed public services, which hinder economic development.

Traditional Chinese villages, originally referred to as ancient villages, denote rural settlement forms that have been relatively well-preserved from earlier times. They possess significant cultural, social, artistic, aesthetic, and economic value1. Traditional villages encompass a wealth of both tangible and intangible cultural heritage. They serve as crucial repositories of historical culture and regional characteristics and constitute an essential component of urban and rural development as well as cultural transmission. Preserving these villages is vital for sustaining cultural diversity2. In recent years, research on traditional villages has garnered significant attention both domestically and internationally. Key research areas encompass the spatial distribution and evolution of traditional villages3,4,5, their cultural value and preservation6,7, tourism development potential8,9, sustainable development strategies10, and factors influencing these aspects11,12.

As global rural tourism, study tours, and cultural tourism gain popularity, traditional villages are increasingly becoming key tourist destinations. Developing tourism in these villages helps preserve cultural heritage while supporting their sustainable growth13. Conducting a scientific and comprehensive evaluation of their tourism development potential has emerged as a critical research direction both domestically and internationally14. Currently, research on the evaluation of tourism development potential in traditional villages, both domestically and internationally, primarily focuses on areas such as the construction of indicator systems, evaluation models and methods, spatial patterns, and driving factors. The evaluation indicator system generally includes multiple elements such as natural resources, ecological environment, socio-economic conditions, historical and cultural heritage, and infrastructure. However, there are different emphases in terms of resource endowment, intrinsic value, and development conditions15,16,17. Multi-indicator evaluation methods for traditional villages include qualitative SWOT18 and quantitative weighted methods. The determination of indicator weights often uses subjective weighting methods, such as the Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP), Delphi method, and expert scoring, or objective weighting methods, such as the entropy method, CRITIC, and principal component analysis, as well as combined subjective and objective weighting methods19,20. Gherdan et al.21 applied the AHP to determine the priority criteria for sustainable tourism development in Pestera Village, focusing on six essential areas, with Environmental Sustainability emerging as the top priority, closely followed by Economic Benefits. After determining the indicator weights, methods such as weighted sum, TOPSIS, and fuzzy comprehensive evaluation are used to calculate the composite scores of the indicators9,22. The research on the spatial pattern and driving factors of traditional villages often employs methods such as kernel density, nearest neighbor analysis, and spatial autocorrelation to analyze spatial distribution patterns, combined with geographical weighted regression, geographical detectors, and cluster analysis to study the driving factors23,24,25,26.

Tourism development potential includes resource endowment, geographic location, transportation conditions, economy, market, and government support17,27,28. In contrast, the Location Potential for Tourism Development (LPTD) based on location theory, still falls within the scope of tourism development potential. However, it does not include internal resources and values such as history, culture, and art within traditional villages, but rather focuses more on external factors of the villages. Existing literature on the research of the LPTD is limited. On one hand, there is a lack of discussion on the spatial scale of location potential, with assessments typically confined to individual villages. On the other hand, the choice of indicator systems has not sufficiently highlighted the role of policy, despite its significant impact on cultural heritage. Finally, the spatial autocorrelation, cold and hot areas, spatial correlations, and clustering characteristics of location potential need further exploration, which would help with the site selection and mode decisions for tourism development in traditional villages.

For research on the spatial scale of tourism development location potential in traditional villages, a multi-dimensional indicator system should be constructed. In addition to data from literature, questionnaires, and statistical yearbooks, macro-scale remote sensing data should also be considered as a source of indicator data. Sichuan Province boasts a wealth of traditional villages, each characterized by distinct features. These villages are situated across diverse geographical regions and harmoniously integrate unique natural landscapes, architectural styles, historical cultures, and folk customs, making them highly valuable for tourism development. However, their locational potential, spatial distribution, and development patterns remain unclear, creating challenges for effective tourism planning and development. This study focused on the traditional villages in Sichuan Province, aiming to develop a comprehensive assessing indicator system based on five key dimensions: natural environment, location and transportation, social economy, tourism market, and policy support. The entropy weight method was employed to determine the indicator weights, and the weighted summation method was utilized to quantitatively assessing the LPTD of traditional villages. In addition, GIS spatial analysis, the total gravity model, and spatially constrained multivariate clustering were applied to further analyze the LPTD. Ultimately, this study seeks to achieve the following objectives: (1) Clarify the spatial distribution characteristics of traditional villages. (2) Compare the importance of indicators. (3) Classify the LPTD grades. (4) Analyze the spatial autocorrelation and associations of LPTD. (5) Analyze the spatial clustering characteristics of traditional villages. (6) Provide suggestions for the tourism development of traditional villages. The results of this study serve as a reference for developing an indicator system and evaluation methods for LPTD. They also offer guidance for selecting tourism development sites in traditional villages across Sichuan Province and support the integrated regional development of culture and tourism.

Study area and data

Study area

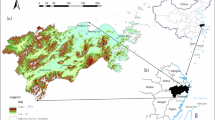

Sichuan Province is situated in the southwest region of China (Fig. 1a) and administers 21 cities (prefectures), among which there are 18 prefecture-level cities and three autonomous prefectures, covering a total of 183 counties (cities and districts). The coordinate range of longitude and latitude is 97°20 ‘50.97 “E to 108°32’ 33.25” E and 26°2 ‘53.55 “N to 34°18’ 54.86” N. Its unique natural geography and diverse multi-ethnic culture have fostered a rich heritage of traditional villages. The assessment and selection of traditional Chinese villages are predicated on their historical and cultural value, the integrity of ecological protection, and the extent of preservation of intangible cultural heritage, offering significant support and potential for rural revitalization and the integrated development of culture and tourism. As of the present, a total of 396 villages in Sichuan Province have been enlisted in the protection list of traditional Chinese villages, ranking among the foremost in the country. The positional distribution of these traditional villages is presented in Fig. 1b.

Study area and distribution of traditional villages. (a) Supervised by the Ministry of Natural Resources of the People ‘s Republic of China, without any modifications; (b) Source: National Geomatics Center of China; boundaries have not been modified. Map created using ArcGIS Pro version 2.5 (https://www.esri.com/arcgis).

These villages are extensively distributed in regions such as the Western Sichuan Plateau, the Northern Sichuan Mountainous Area, the Southern Sichuan Hilly Region, and the Eastern Sichuan Basin, encompassing areas where the Zang, Qiang, Yi, and Han ethnic groups are concentrated. The villages of Zang and Qiang in western Sichuan are characterized by stone-built watchtowers and strongholds, while in southern Sichuan, they are mainly composed of bamboo and wooden buildings and traditional residences. The villages in northern and eastern Sichuan mostly embody the ancient post-road culture and the architectural style of the Ming and Qing Dynasties. Figure 2 presents photographs of three typical traditional villages, captured in January 2025. Figure 2a and b depicts Moluo Village in Danba County, northwestern Sichuan. There are numerous watchtowers here, which, complementing the surrounding Zang forts, terraced fields, rivers, and other natural landscapes, constitute a succession of beautiful scenes. Figure 2c represents the Jinpen Residences (Xiangjia Courtyard) in Dingxian Village, Yibin City, in the southern part of Sichuan Province. The village originated during the Ming Dynasty and contains 30 sets of buildings from the Ming and Qing Dynasties. These are mostly of the “three-sided courtyard style,” “L-shaped,” “four-sided courtyard style,” and “single-row style,” with mainly gray and black tiled houses. Figure 2d shows the old street community of Luodai in the Chengdu Plain, featuring typical architectural styles of the Ming and Qing Dynasties and serving as a real museum of Hakka culture.

Figure 3a shows the tourism development grade of traditional villages in Sichuan Province. A higher grade indicates a more advanced level of tourism development, including better utilization of tourism resources, improved infrastructure, and enhanced tourist services. The number of villages with high and relatively high degrees of tourism development is scarce, being 8 and 13, respectively. The majority of villages have low or relatively low degrees of tourism development (Fig. 3b), suggesting that there is still considerable potential for the tourism development of traditional villages in Sichuan Province.

Tourism development grade of traditional villages. (a) Source: National Geomatics Center of China; boundaries have not been modified. Map created using ArcGIS Pro version 2.5 (https://www.esri.com/arcgis).

Data sources and preprocessing

Traditional village

The data on traditional villages was obtained from the Traditional Chinese Villages Digital Museum (https://www.dmctv.cn). This platform offers detailed listings, addresses, historical backgrounds, and traditional architectures of traditional Chinese villages. In Sichuan Province, there are altogether 396 traditional Chinese villages. The positional coordinates of the villages were acquired through the conversion of village addresses, i.e., the addresses were transformed into Baidu coordinates (BD09) via the Geocoding API of Baidu Maps, and subsequently the BD09 coordinates were converted to WGS84 coordinates. The data on the tourism development grades of traditional villages (Fig. 3) originated from the official websites of local governments and news websites throughout Sichuan Province and were collected, analyzed, and collated using Doubao AI (https://www.doubao.com).

Administrative division

The map of China (Fig. 1a) was sourced from the Standard Map Service (https://bzdt.ch.mnr.gov.cn), with a scale of 1:60,000,000, a map review number of GS(2019)1652, and an EPS format. The administrative division data for provinces, cities, and counties in Sichuan Province, encompassing regional and boundary details, were derived from Tianditu (https://www.tianditu.gov.cn), with a map review number of GS(2024)0650. The coordinate system is CGCS2000, the file format is GeoJSON and the EPSG code is 4490. It was necessary to utilize ArcGIS Pro to convert the format to ShapeFile. Owing to the scarcity of administrative division data at the village scale, based on the actual area of village-level administrative regions and considering the spatial scale and resolution of the indicator data, this study applied a 5-km buffer analysis around village point data to define the administrative boundaries at the village level.

Regional boundary

The boundaries of the five major regions in Sichuan Province were derived from the “Sichuan Provincial Spatial Planning (2021–2035)” plan. This plan divides Sichuan Province into five major areas from a spatial perspective: the Chengdu Plain, Southern Sichuan, Northeastern Sichuan, Panxi, and Northwestern Sichuan. The boundary of the Sichuan Basin was obtained by extracting the 700-m contour line from the SRTM 90-m DEM.

Indicator data

Evaluating the location potential for tourism development in traditional villages requires the precise identification of assessment indicators (Zhang et al., 2025). This study focuses on the influencing factors of location potential for tourism development in traditional villages22. Based on location theory, taking into account the scientific rigor, rationality, accessibility, and reliability of the evaluation indicators, this study selected 25 indicators based on the characteristics of traditional villages, tourism development, and geographical location. These indicators were categorized into five dimensions—natural environment, location and transportation, socio-economic factors, tourism market, and policy—to construct an evaluation system for assessing the LPTD of traditional villages. The indicator data encompassed natural resources, climate, ecological environment, topography, geographical location, transportation, economy, population, education, infrastructure, tourism market, and policy support. They were primarily sourced from Google Earth Engine (GEE), OpenStreetMap, the “Sichuan Statistical Yearbook,” tourism planning data, basic geographic information, and questionnaire surveys, among others. In the selection of indicators, the variables “Number of Tourists” and “Tourism Revenue” were not adopted under the tourism market dimension. This decision was based on the consideration that some traditional villages have not yet undergone tourism development or lack public recognition, and thus these two indicators may not accurately reflect the actual location potential of the villages. Instead, this study employs “Tourism Network Centrality,” which is calculated based on tourism flow data obtained through questionnaire surveys29. This indicator reflects a village’s position within the tourism network, where higher centrality indicates a greater number of connections as tourist origins or destinations. As such, this represents an innovative approach and extends beyond conventional indicators. Regarding policy factors, while policies such as the Sichuan Traditional Village Protection Ordinance and the designation of national and provincial demonstration counties for clustered conservation and utilization of traditional villages have promoted the development and protection of traditional villages, they do not capture spatial variations in regional culture and ethnic characteristics. Therefore, this study includes the “Bashu Corridor”, “Zang-Qiang-Yi Corridor”, and “ITT Demonstration Zone” as indicators. These reflect government planning and investment in regional culture, ethnic industries, and the integration of transportation and tourism. These selected indicators embody a multidimensional and regional-scale perspective. Additionally, data availability was taken into full account, incorporating sources such as remote sensing, geographic information systems, questionnaire surveys, statistical data, and planning documents. This comprehensive approach ensures the rationality and scientific validity of the location potential assessment for tourism development in traditional villages. Table 1 presents the assessing indicator system, comprising the names of the indicators, data sources, characteristics of the indicators, etc. The spatial references of the indicator data were uniformly processed into the CGCS2000 coordinate system and the Gauss–Kruger projection, with a 6-degree zone, a central meridian of 102°, and a zone number of 17. The spatial distribution of the 25 indicators after initial processing is presented in Fig. 4.

Data preprocessing

First, the indicator values of the traditional villages were extracted. Among the 25 indicators, three indicators, namely the Distance to Hub City, Distance to Airport, and Distance to NTCD, are point data, and their attribute values were directly adopted as the indicator values. The remaining 22 indicators were raster or polygon data. The village area, obtained through a 5-km buffer analysis, was used for conducting spatial overlay analysis, and the average value extracted was taken as the indicator value. Second, positive transformation was conducted. To ensure consistency in the multi-indicator evaluation system, indicators were classified into three types: positive, negative, and normal distribution curve types. Appropriate transformations were applied to standardize their direction, eliminating biases caused by differences in indicator properties. Finally, normalization was performed. The maximum-minimum normalization method was employed to stretch or compress the indicator values into the [0, 1] range with a confidence level of [2%, 98%], eliminating the effects of different dimensions. Since in the subsequent calculation, the value of the indicator cannot be less than or equal to 0, therefore, add 0.00001 to all indicators with a value of 0. Through the aforementioned processing, the normalized data of 25 indicators for 396 traditional villages in Sichuan Province were obtained.

Spatial distribution of indicators. Source: National Geomatics Center of China; boundaries have not been modified. Map created using ArcGIS Pro version 2.5 (https://www.esri.com/arcgis).

Methods

Research framework

Figure 5 presents the research framework. First, data such as those related to traditional villages, administrative divisions, and indicators from remote sensing, geography, and statistical yearbooks were collected, and the data were unified into the same coordinate system and projection. Subsequently, the indicator data were extracted, and the indicator weights were calculated using the entropy weight method, while the comprehensive LPTD score was computed using the weighted summation method. The spatial distribution characteristics of traditional villages were analyzed by employing the kernel density method and the nearest neighbor index. The significance of all indicators with respect to LPTD was compared, and a heat map analysis was conducted on the indicator scores. The LPTD grades of traditional villages were categorized, and the spatial pattern of LPTD was examined. Global spatial autocorrelation was analyzed through Moran’s I, while local spatial autocorrelation was analyzed using Anselin Local Moran’s I and Getis-Ord Gi*. The spatial associations of LPTD were analyzed using the total gravity model. The spatial clustering characteristics of traditional villages were analyzed using the spatially constrained multivariate clustering method. Finally, based on the analysis results, strategic recommendations are proposed for selecting optimal locations for traditional village tourism development in Sichuan Province.

Entropy weight method

The entropy weight method is an objective weighting approach based on the theory of information entropy and is widely utilized in the domain of multi-index comprehensive evaluation33. The basic concept is to gauge the degree of dispersion of each index by computing its information entropy, thereby ascertaining the significance of each index. The entropy weight method can evade the interference of subjective weighting and possesses high objectivity and extensive applicability.

Positive transformation of the indicators

Since the original data have different dimensions, it is necessary to carry out standardization processing on the data to eliminate incomparability among the indicators. The range method was employed for standardization, and the formula is as follows:

Positive type indicators (the larger the value, the better):

Negative type indicators (the smaller the value, the better):

Normal distribution curve type indicators (the middle value is the best):

In Eqs. (1)–(3): \(\:{z}_{ij}\) denotes the value of the \(\:i\)-th traditional village under the \(\:j\)-th indicator; \(\:{x}_{ij}\) represents the original data value; \(\:{C}_{j}\) stands for the optimal value of the \(\:j\)-th indicator (the peak of the normal distribution curve or the ideal value); \(\:\text{max}\left(\right|{x}_{ij}-{C}_{j}\left|\right)\) implies the maximum distance by which the \(\:j\)-th indicator deviates from the optimal value.

Normalization processing

After all the indicators were made positive, they were subjected to normalization processing. To eliminate the interference of outliers, the 2% confidence interval of the minimum and maximum values of the dataset was utilized, thereby enhancing the accuracy and stability of the normalization.

In the equation, \(\:{R}_{ij}\) denotes the normalized value of the \(\:i\)-th traditional village under the \(\:j\)-th indicator; \(\:{z}_{ij}\) represents the positive-transformed value of the \(\:i\)-th traditional village under the \(\:j\)-th indicator; \(\:\text{min}\left({z}_{j}\right)\) represents the minimum positive-transformed value of the \(\:j\)-th indicator; \(\:\text{max}\left({z}_{j}\right)\) represents the maximum positive-transformed value of the \(\:j\)-th indicator.

Calculating the proportion of indicators

The formula for calculating the indicator proportion of the normalized data is:

In the formula, \(\:{p}_{ij}\) represents the proportion of the \(\:i\)-th traditional village under the \(\:j\)-th indicator.

Information entropy calculation

Information entropy reflects the degree of variation of an indicator, and the formula is:

In the formula, \(\:{H}_{j}\) represents the information entropy of the \(\:j\)-th indicator; \(\:k=\frac{1}{\text{ln}\left(n\right)}\) is a constant to ensure that the entropy value is non-negative; \(\:n\) is the number of traditional villages; \(\:{p}_{ij}\) is the proportion of the \(\:i\)-th village under the \(\:j\)-th indicator, and its value cannot be 0. If the information entropy of a certain indicator is smaller, it indicates that the variation degree of its indicator value is greater, and the amount of information it provides is also greater. It can be considered that the role of this indicator in the comprehensive evaluation is also greater.

Weights calculation

The weights of each indicator were calculated based on the entropy value, and the formula is as follows:

In the formula, \(\:{w}_{j}\) represents the weight of the \(\:j\)-th indicator, \(\:{H}_{j}\) is the information entropy of the \(\:j\)-th indicator, and \(\:m\) is the number of indicators.

Weighted summation method

The weighted summation method is a comprehensive evaluation approach based on the weights of indicators. It has been extensively utilized in multi-dimensional data analysis and decision support34. The method entails multiplying the standardized data by their corresponding weights and subsequently summing all the products to acquire a comprehensive score. The formula is presented as follows:

In the formula, \(\:S\) represents the comprehensive score; \(\:{w}_{i}\) is the weight of the \(\:i\)-th indicator; \(\:{x}_{i}\) is the score of the \(\:i\)-th indicator; and \(\:n\) is the total number of indicators.

Kernel density Estimation

Kernel density analysis is a method to assess the distribution of spatial data. It is widely applied in Geographic Information Systems (GIS) to analyze the density distribution patterns and trends of point data35. Kernel density analysis converts discrete point data into a continuous distribution, visually presenting the density characteristics of the data, thereby identifying hotspots within the data, that is, areas with higher density. The formula for kernel density analysis is as follows:

In the formula, \(\:\widehat{f}\left(x\right)\) represents the density estimation value at point \(\:x\); \(\:n\) is the number of traditional villages; \(\:h\) is the kernel bandwidth, which controls the degree of smoothing; \(\:K\) is the kernel function, and commonly used kernel functions include the Gaussian kernel and the Uniform kernel; \(\:{x}_{i}\) is the coordinate of the traditional village.

Nearest neighbor index analysis

The nearest neighbor index method is a statistical tool used to analyze the spatial distribution of geographic point data. It assesses whether point features are randomly distributed, clustered, or dispersed by measuring the distance from each point to its nearest neighbor. This distance is then compared with the expected average distance under a random distribution assumption, allowing for the identification of underlying spatial patterns36. The formula is:

In the formula, \(\:NNI\) represents the nearest neighbor index, \(\:{R}_{i}\) is the actual nearest distance, \(\:{R}_{E}\) is the theoretical nearest distance, \(\:m\) is the number of traditional villages, \(\:A\) is the area of the study region, and \(\:D\) indicates the number of villages per unit area.

When \(\:NNI\) ≈ 1, it indicates that traditional villages are randomly distributed in space. When \(\:NNI\) < 1, it indicates an aggregated distribution, and when \(\:NNI\) > 1, it indicates a dispersed distribution. Generally, the \(\:Z\) value is used to determine the significance of the nearest neighbor index results. If \(\:\left|Z\right|\) > 1.96 (at a 95% confidence level), the result is significant.

Spatial autocorrelation analysis

Global Spatial autocorrelation analysis

Global spatial autocorrelation is a commonly used analytical method in spatial statistics. It quantitatively describes the degree of aggregation or distribution pattern of a certain variable in space, thereby determining whether the distribution of the variable is random, clustered, or uniform37. Global spatial autocorrelation is typically measured by Moran’s I index, whose mathematical expression is as follows:

In the formula, \(\:I\) represents Moran’s \(\:I\) indicating the degree of spatial autocorrelation; \(\:n\) is the number of traditional villages; \(\:{x}_{i}\) and \(\:{x}_{j}\) denote the location potential values of the \(\:i\)-th and \(\:j\)-th traditional village, respectively; \(\:\stackrel{̄}{x}\) is the mean of the location potential; \(\:{w}_{ij}\) is the spatial weight matrix, reflecting the spatial adjacency relationship between traditional villages \(\:i\) and \(\:j\).

The significance of Moran’s \(\:I\) is evaluated through the \(\:Z\)-test. If the \(\:p\)-value corresponding to the \(\:Z\)-value is smaller than the significance level (0.05 or 0.01), it suggests the presence of significant global spatial autocorrelation. The range of Moran’s \(\:I\) typically lies within [− 1, 1]: when \(\:I\) > 0, it indicates that the variable exhibits positive spatial autocorrelation, meaning similar values are clustered spatially, presenting as either high-value clustering or low-value clustering; when \(\:I\) < 0, it implies that the variable has negative spatial autocorrelation, indicating that similar values are dispersed spatially, manifesting as an alternating distribution of high and low values; when \(\:I\) = 0, it indicates that the distribution of the variable in space is random.

Local Spatial autocorrelation

Local spatial autocorrelation is used to analyze the spatial distribution and variability of regional variables within a specific area. It helps identify spatial patterns, such as hotspots (clusters of high values) and coldspots (clusters of low values). This paper employs Anselin Local Moran’s \(\:I\)38 and Getis-Ord Gi*39 statistics for local spatial autocorrelation analysis. The formula for Anselin Local Moran’s \(\:I\) is as follows:

In the formula, \(\:{I}_{i}\) represents the local Moran’s \(\:I\) value of the \(\:i\)-th traditional village; \(\:{x}_{i}\) is the location potential value of the \(\:i\)-th traditional village; \(\:\stackrel{-}{x}\) is the average value of the location potential of all traditional villages; \(\:{w}_{ij}\) is the spatial weight matrix, reflecting the adjacency relationship or distance between units \(\:i\) and \(\:j\); \(\:{W}_{i}\) represents the total weight of the \(\:i\)-th traditional village, that is, the sum of the weights of this village and all adjacent villages. When \(\:{I}_{i}\) > 0 and significant, it indicates that the village has similar values to its neighboring villages, showing a clustering of similar values (either high- or low-value clustering); when \(\:{I}_{i}\) < 0 and significant, it indicates that the value of this village is different from that of its neighboring villages, showing a clustering of different values (alternation of high and low values); If \(\:{I}_{i}\) is not significant, it indicates that there is no obvious local spatial autocorrelation at that position. The Getis-Ord Gi* formula is as follows:

In the formula, \(\:{G}_{i}^{*}\) represents the Getis-Ord Gi* statistic of the \(\:i\)-th traditional village; \(\:{x}_{i}\) represents the location potential value of the adjacent village \(\:j\); \(\:{w}_{ij}\) is the spatial weight between villages \(\:i\) and \(\:j\); \(\:{\stackrel{-}{W}}_{i}\) represents the average weight of the adjacent villages of village \(\:i\); \(\:{\sum\:}_{j}{w}_{ij}\) represents the sum of the weights of all adjacent units of village \(\:i\). When \(\:{G}_{i}^{*}\) is significantly positive, it indicates that high-value aggregation in this area and its adjacent areas has formed a significant hotspot; when \(\:{G}_{i}^{*}\) is significantly negative, it indicates that low-value areas in this area and its adjacent areas have formed a cold spot.

Total gravity model

The total gravity model is an extension of the single gravity model, used to calculate the total interaction strength between a certain geographical element (such as a city and region) and all other elements around it. It comprehensively considers the gravitational effects among multiple elements and can more comprehensively reflect the status and role of a geographical entity in the entire system. The formula is as follows:

In the formula, \(\:{F}_{i}\) represents the total interaction strength between the \(\:i\)-th traditional village and all other villages. The larger the value, the greater the influence of the village in the entire system; \(\:{M}_{i}\) and \(\:{M}_{j}\), respectively, denote the location potential of villages \(\:i\) and \(\:j\); \(\:{D}_{ij}\) represents the distance between villages \(\:i\) and \(\:j\); \(\:G\) is the gravitational constant, usually set to 1; \(\:b\) is the distance attenuation index, typically set to 2, indicating that the interaction strength is inversely proportional to the square of the distance.

Spatially constrained multivariate clustering

The Spatially Constrained Multivariate Clustering (SCMC) method identifies spatial clustering patterns of multiple variables within a region. Unlike traditional multivariate clustering, SCMC integrates spatial adjacency constraints during the clustering process, ensuring that clusters are not only similar in attributes but also spatially continuous40,41.

The basic idea of the SCMC algorithm is as follows42: when performing clustering, spatial constraints are introduced. Besides considering the similarity between samples, the proximity of samples in space is also taken into account. The SCMC method uses the SKATER (Spatial Kluster Analysis by Tree Edge Removal) algorithm of the Minimum Spanning Tree for spatial clustering. First, a connected graph representing the neighborhood relationship between objects is constructed. The minimum spanning tree of the connected graph summarizes the spatial relationship and feature similarity of the objects. Each object is a node in the minimum spanning tree, and the weight of the edge is proportional to the similarity of the objects it connects. The branches (edges) of the minimum spanning tree are pruned to ensure that the sum of the edge weights is minimized, thereby minimizing the feature differences within clusters and generating two minimum spanning trees. This process is repeated multiple times until the desired number of clusters is obtained.

Results

Spatial distribution characteristics of traditional villages

According to the theory of scale effects, the variation of geographic phenomena exhibits different patterns across spatial scales. This study investigates the spatial distribution patterns of traditional villages at the provincial, regional, and city scales. The provincial scale focuses on macro-level trends, the regional scale emphasizes variations within specific subregions, and the city scale reflects the influence of differing levels of urban development. Kernel density estimation and nearest neighbor index analysis were conducted on traditional villages, and the results are shown in Fig. 6. The traditional villages are unevenly distributed in terms of number and density throughout the province. The nearest neighbor index is 0.60, and the overall distribution is clustered. At the regional scale, the number of traditional villages in the northwest of Sichuan (147) is the highest, followed by the northeast (91), the Chengdu Plain (75), and the south (61), while the Panxi region (22) has the fewest (Fig. 6c and e). The kernel density of traditional villages is highest in the northeast of Sichuan, followed by the south, the Chengdu Plain, and the northwest of Sichuan, with the lowest occurring in the Panxi region. The nearest neighbor index of all five regions in the province is less than 0.86, presenting a clustered distribution (Fig. 6b). At the city scale, the number of traditional villages is highest in Ganzi (94), followed by Aba (53), Luzhou (32), Guangyuan (31), Bazhong (29), Panzhihua (3), and Ziyang (3), with Suining having the fewest (2) (Fig. 6d and f). The nearest neighbor index of traditional villages in Ya’an is 1.04, in Guangyuan is 1.05, and in Bazhong is 0.95, all of which are close to a random distribution. Meanwhile, Ganzi, Aba, Liangshan, Yibin, and Luzhou show a clustered distribution, while the rest of the cities show a dispersed distribution (Fig. 6b).

Spatial distribution of traditional villages. (a), (b), (c) and (d) Source: National Geomatics Center of China; boundaries have not been modified. (a), (c) and (d) Map created using ArcGIS Pro version 2.5 (https://www.esri.com/arcgis). (b) Map created using Surfer version 12.2.705 (https://www.goldensoftware.com).

The spatial distribution of traditional villages in Sichuan Province exhibits distinct patterns: they are numerous and scattered in the northwest, numerous and concentrated in the northeast, relatively numerous and clustered in the Chengdu Plain, fewer but concentrated in the south, and sparse and scattered in the Panxi region. In terms of density, the spatial pattern mainly presents a “Six Cores and Five Belts” configuration (Fig. 6a). The “Six Cores” are composed of the Guangyuan-Bazhong core area in the northeastern part of Sichuan, the Ya’an-Meishan-Chengdu-Leshan core area in the Chengdu Plain, the Zigong-Luzhou core area in the southern part of Sichuan, the core area of Danba County, the core area of Litang County in Garze Prefecture in the northwestern part of Sichuan, and the core area of Wenchuan County in Aba Prefecture. The “Five Belts” are composed of the belt encompassing Chengdu, Deyang, Mianyang, Guangyuan, Bazhong, and Dazhou; the belt encompassing Chengdu, Ya’an, Meishan, Leshan, Neijiang, Zigong, Yibin, and Luzhou; the belt encompassing Danba County, Wenchuan County, and Jiuzhaigou County; the belt encompassing Litang County, Daocheng County, and Yanyuan County; and the belt encompassing Dege County, Ganzi County, Seda County, Luhuo County, and Rangtang County.

Distribution Pattern: At the provincial and regional scales, they exhibit a clustered distribution. At the city scale, cities in the west and south mainly present a clustered distribution, while those in the central and east mainly show a discrete distribution. Notably, Ya’an in the central region and Bazhong and Dazhou in the northeastern region are close to a random distribution. This spatial analysis clarifies the overall distribution patterns, clustering tendencies, and regional disparities of traditional villages in Sichuan Province.

LPTD evaluation of traditional villages

Indicator weights

The entropy weight method was employed to compute the proportions, information entropies, and weights of the 25 normalized indicators. Based on the concept of information entropy, the degree of dispersion and information content of the indicators were gauged. The smaller the information entropy, the greater the degree of dispersion of the indicator, the higher its information content, and, accordingly, the greater the weight. Figure 7 shows the histograms and weights of the indicators. Figure 7a presents the frequency distribution of the indicator values, whose characteristics such as central tendency, dispersion degree, and skewness determine the magnitude of the indicator weights. A higher indicator weight signifies a greater influence on the evaluation objective, making the indicator more critical in the assessment. Conversely, a lower weight value indicates a smaller impact on the evaluation objective, making the indicator less significant. The indicator weight comparison (Fig. 7b) yielded the following results: Bashu Corridor has the highest weight (0.0810), making it the most influential factor in evaluating the LPTD of traditional villages. It is followed by Terrain Relief (0.0664), Population Density (0.0637), and Tourism Network Centrality (0.0600). Indicators with lower weights include Air Temperature, Tertiary Industry, NDVI, and Precipitation, with Precipitation (0.0041) having the least impact. At the dimension level, the weight ranking is Natural Environment (0.2828) > Social Economy (0.2290) > Location and Transportation (0.2200) > Policy Support (0.1638) > Tourism Market (0.1044).

Indicator score

According to the weighted summation method, the score of a single indicator for a single sample can be obtained by multiplying the indicator value by the indicator weight. Figure 8 shows the heat map of the scores of the 25 indicators for 396 traditional villages. As shown in Fig. 8a, for individual indicators, the contribution of the Bashu Corridor is the largest, followed by the Railway Station, the Zang-Qiang-Yi Corridor, and Total AOD. The contributions of Air Temperature, Tertiary Industry, NDVI, and Precipitation are relatively low. At the city scale, Aba, Ganzi, Liangshan, and Panzhihua have significant differences in scores compared with other cities, while among the other cities, Bazhong, Dazhou, Guangyuan, and Ya’an also show considerable differences. In terms of indicator dimensions (Fig. 8b), the Natural Environment score is relatively high within the Sichuan Basin. The scores for Location and Transportation are higher in the Chengdu Plain, Northeastern Sichuan, and Southern Sichuan. The Social and Economic scores are higher in Chengdu, Deyang, Mianyang, Dazhou, Zigong, and Luzhou. The Tourism Market score is higher in Chengdu, Deyang, Leshan, and Zigong. The Policy Support score is higher in the Chengdu Plain, Southern Sichuan, and Northwestern Sichuan. Overall, among the five dimensions, the Chengdu Plain and Southern Sichuan have higher scores, followed by Northeastern Sichuan, while Northwestern Sichuan and Panxi have the lowest scores.

Indicator heat map and spatial distribution of dimensions. (b) Source: National Geomatics Center of China; boundaries have not been modified. Map created using ArcGIS Pro version 2.5 (https://www.esri.com/arcgis).

LPTD grade classification

The comprehensive scores of the 25 indicators of the traditional villages were computed using the weighted summation method. The results are presented in Fig. 9. The LPTD score is relatively high within the Sichuan Basin, while it is relatively low in the northwest, northeast, and southwest. The highest score is 0.6803, the lowest is 0.1315, the median is 0.2686, and the mean is 0.2930. The histogram shape is right-skewed, with the majority of the values being relatively low. There are 248 villages with scores lower than the mean (0.2930), accounting for 62.63%. Overall, the LPTD of traditional villages in Sichuan Province is mostly low in general. The high values are situated within the Sichuan Basin, while the LPTD in the northwest plateau of Sichuan and the mountainous areas surrounding the basin is relatively low.

Spatial distribution and histogram of LPTD. (a) Source: National Geomatics Center of China; boundaries have not been modified. Map created using ArcGIS Pro version 2.5 (https://www.esri.com/arcgis).

Based on the comprehensive scores, the LPTD of the 396 traditional villages was classified into three grades using the natural breaks method (Fig. 10a): low potential (LPTD ≤ 0.2523), medium potential (0.2523 < LPTD ≤ 0.4047), and high potential (LPTD > 0.4047). The spatial distribution is shown in Fig. 10b. There are 179 villages with low potential, accounting for 45.20%, with a median of 0.1895 and an average of 0.1959, mainly distributed in the northwest, northeast of Sichuan Province, and the Panxi region. There are 147 villages with medium potential, accounting for 37.12%, with a median of 0.2999 and an average of 0.3103, mainly distributed on the edges of the Sichuan Basin and the central part of Ganzi Prefecture. There are 70 villages with high potential, accounting for 17.68%, with a median of 0.4865 and an average of 0.5007, mainly located in the interior of the Sichuan Basin.

Grade and spatial distribution of LPTD. (b) Source: National Geomatics Center of China; boundaries have not been modified. Map created using ArcGIS Pro version 2.5 (https://www.esri.com/arcgis).

A comprehensive evaluation of the LPTD of traditional villages in Sichuan Province revealed its spatial distribution patterns. Villages with high grades have higher comprehensive scores and better location potential and are more suitable for tourism development. Although villages with medium potential have a lower comprehensive location value than those with high grades, they also have advantages in certain indicators.

LPTD Spatial pattern

The inverse distance interpolation method was used to spatially interpolate the LPTD of traditional villages, generating a continuous distribution map of LPTD across Sichuan Province. Then, the grades were classified according to the standard for traditional villages. The spatial pattern of the LPTD of the entire Sichuan Province is shown in Fig. 11a. The LPTD in the province is divided into three grades, namely low potential, medium potential, and high potential. The high potential area is located in the interior of the Sichuan Basin, including most of the regions of Chengdu, Deyang, Meishan, Zigong, Neijiang, and Ziyang, as well as parts of Mianyang, Leshan, Yibin, Luzhou, Suining, Nanchong, and Guang’an, accounting for 13.54% of the total area. The medium potential area is mainly distributed at the edges of the Sichuan Basin, the eastern Sichuan hills, and the central part of Ganzi Prefecture, accounting for 27.86% of the total area. The low potential area is distributed in the northern and southern parts of the northwest Sichuan Basin, the Panxi area, and the northeastern part of northeast Sichuan, accounting for 56.60% of the total area. The area ratio of high, medium, and low potential regions is approximately 1:2:4, and more than half of the province’s area belongs to the low potential region.

LPTD spatial pattern. (a), (b) and (c) Source: National Geomatics Center of China; boundaries have not been modified. Map created using ArcGIS Pro version 2.5 (https://www.esri.com/arcgis).

The regional average LPTD analysis (Fig. 11b) shows that the Chengdu Plain and southern Sichuan have the highest LPTD, followed by northeastern Sichuan, while northwestern Sichuan and the Panxi region have the lowest LPTD. At the city scale (Fig. 11c and d), Chengdu, Deyang, Zigong, and Neijiang have the highest LPTD, followed by 11 cities in the Chengdu Plain, southern Sichuan, and the southeastern part of northeastern Sichuan, while Ganzi, Aba, Liangshan, Panzhihua, Guangyuan, and Bazhong have the lowest LPTD.

LPTD Spatial autocorrelation

Global Spatial autocorrelation

The global Moran’s \(\:I\) of the LPTD of traditional villages in Sichuan Province is 0.6721, \(\:p\) = 0.0000 (\(\:p\) < 0.01), \(\:z\) = 35.0839, and the result is significant. This indicates that at the provincial scale, the spatial distribution of LPTD has a significant positive spatial autocorrelation, and the LPTD of adjacent areas shows an agglomeration phenomenon. To further investigate the global spatial autocorrelation at different scales, the global Moran’s \(\:I\) was analyzed at the regional and city scales. At the regional scale (Fig. 12a), the global Moran’s \(\:I\) of all five regions is greater than 0, and \(\:p\) < 0.01, all showing significant positive spatial autocorrelation. At the city scale (Fig. 12b), due to the small number of villages, the global Moran’s \(\:I\) could not be calculated for Suining, Ziyang, and Panzhihua. Moran’s \(\:I\) of Deyang and Nanchong was less than 0, with \(\:p\) < 0.01, indicating significant negative spatial autocorrelation. The global Moran’s \(\:I\) of Neijiang and Zigong was close to 0, with \(\:p\) < 0.01, suggesting weak spatial autocorrelation and a nearly random distribution of LPTD in space. For all other cities, Moran’s \(\:I\) was greater than 0, with \(\:p\) < 0.01, indicating significant positive spatial autocorrelation.

Global spatial autocorrelation of LPTD. (a) and (b) Source: National Geomatics Center of China; boundaries have not been modified. Map created using ArcGIS Pro version 2.5 (https://www.esri.com/arcgis).

Overall, at the provincial and regional scales, the spatial distribution of the location potential of traditional villages exhibits positive autocorrelation, that is, the potential values of adjacent villages are similar. At the city scale, with the exception of three cities with insufficient data, two cities with negative autocorrelation, and two cities with a random distribution, the other 14 cities all present a positive autocorrelation distribution.

Local spatial autocorrelation

The results of the global spatial autocorrelation analysis show that the distribution of the LPTD of traditional villages at the provincial scale presents a significant positive spatial autocorrelation. To further explore the spatial aggregation patterns in local areas, this study employs Anselin Local Moran’s I and Getis-Ord Gi* for local spatial autocorrelation analysis. The results are shown in Fig. 13. The location potential of traditional villages in Sichuan Province mainly presents a spatial distribution pattern of high–high clustering and low–low clustering in local areas (Fig. 13a), with significant hotspots and coldspots (Fig. 13b). High–high clustering is distributed in the Sichuan Basin, while low–low clustering is distributed in the northwest, northeast, and southwest of Sichuan. By grouping spatially adjacent villages with the same clustering pattern, one “hot area” and two “cold areas” were identified. The “hot area” is located in the Sichuan Basin, including the Chengdu Plain, southern Sichuan, and the southern part of Northeast Sichuan. The “cold areas” are located in the northwest of Sichuan and the Panxi area.

Local spatial autocorrelation of LPTD. (a) and (b) Source: National Geomatics Center of China; boundaries have not been modified. Map created using ArcGIS Pro version 2.5 (https://www.esri.com/arcgis).

LPTD Spatial associations

To analyze the spatial interaction of LPTD among traditional villages, this study applied the total gravity model to calculate the interaction intensity for each village. The Kriging method was then used for spatial interpolation, followed by classification into three intensity levels—low, medium, and high—using the natural break method. A higher interaction intensity indicates a stronger spatial connection between a village and others in terms of location potential, reflecting greater spatial correlation, status, and influence. Figure 14 shows the total interaction intensity of the LPTD of traditional villages. Villages with high intensity are located in the Sichuan Basin, mainly distributed in the Chengdu Plain and the southern part of Sichuan Province, and are spatially clustered into three regions: (1) Chengdu, Deyang, and Mianyang, (2) Zigong, Luzhou, Yibin, and Neijiang, and (3) Ya’an, Meishan, Leshan, and Chengdu. Villages with medium intensity are located in the Chengdu Plain, southern Sichuan, northeastern Sichuan, and parts of northwestern Sichuan. Villages with low intensity are widely distributed, including over the entire Panxi region, most of northwestern Sichuan, and parts of northeastern Sichuan.

Source: National Geomatics Center of China; boundaries have not been modified. Map created using ArcGIS Pro version 2.5 (https://www.esri.com/arcgis).

Spatial associations of LPTD.

Spatial clustering analysis

To uncover the underlying spatial clustering patterns of traditional villages, this study applied a spatially constrained multivariate clustering analysis to the normalized village indicators. As a result, the traditional villages in Sichuan Province were classified into four distinct types, each exhibiting clear regional agglomeration characteristics (Fig. 15a). Type I is located in the southwest of the Chengdu Plain, including parts of Chengdu, Ya’an, Meishan, and Leshan, with 37 villages, accounting for 9.34%. Type II is located in the northwest of Sichuan and the Panxi area, covering the entire regions of Ganzi, Aba, Liangshan, and Panzhihua, with 178 villages, accounting for 44.95%. Type III is located in the northern part of northeastern Sichuan, including parts of Guangyuan, Bazhong, Nanchong, and Dazhou, with 74 villages, accounting for 18.69%. Type IV is located in the interior of the Sichuan Basin, including the Chengdu Plain, southern Sichuan, and northeastern Sichuan, with 107 villages, accounting for 27.02%.

Spatial clustering characteristics of LPTD. (a) Source: National Geomatics Center of China; boundaries have not been modified. Map created using ArcGIS Pro version 2.5 (https://www.esri.com/arcgis).

Figure 15b shows the average scores of the four types for each indicator. Type I villages are spatially concentrated and exhibit a relatively balanced potential across all five indicator dimensions. They are located near major national tourist destinations and benefit from proximity to high-level scenic attractions such as Leshan and Emei Mountain, which draw a significant number of visitors. Given these advantages, their development is primarily tourism-oriented. Type II villages have rich natural reserves, scenic spots, and forest parks with abundant tourism resources. Their development orientation is primarily resource-oriented. Type III villages have high vegetation coverage, and their development orientation is primarily ecological villages. Type IV villages have obvious overall advantages and a developed transportation network, and their development orientation is transportation-oriented villages. Table 2 presents an analysis of the advantages, disadvantages, and potential enhancement strategies for the five village types.

Discussion

Research work

This study established a multidimensional indicator system for evaluating location potential and, for the first time, assessed the LPTD of traditional villages in Sichuan Province from a regional perspective. It conducted classification, spatial analysis, and clustering analysis to reveal the spatial pattern, aggregation modes, interaction intensity, and spatial clustering characteristics of LPTD of traditional villages. Academically, the research provides a methodological reference for the construction of indicator systems and evaluation approaches, offering new insights into the spatial understanding of LPTD in Sichuan’s traditional villages. These include the spatial structure of the “Six Cores and Five Belts” pattern, the classification and spatial distribution of location potential levels, the clustering pattern of one “Hot area” and two “Cold area” the classification and spatial structure of interaction intensity, and the spatial clustering characteristics. In terms of socio-economic value, understanding the spatial autocorrelation, distribution of cold and hot area, spatial connectivity, and clustering characteristics of location potential is essential for effectively promoting the integrated conservation and utilization of traditional villages.

Indicator selection

Compared with existing studies, this study expands the selection of evaluation indicators beyond the commonly considered factors—natural environment, location and transportation, social economy, and tourism market16,19. It also incorporates policy factors, such as government development plans, including the “Construction Plan for the Bashu Cultural Tourism Corridor,” the “Overall Plan for the Cultural Industry Corridor of Zang, Qiang, and Yi Ethnic Groups,” and the “Cultural and Tourism Development Plan of Sichuan Province for the 14th Five-Year Plan.” In terms of the tourism market, given that many traditional villages have not yet been developed for tourism, this study does not select indicators such as the number of tourists, tourism revenue, and tourist satisfaction43,44, but instead opts for two indicators that better reflect the locational potential—Tourism Network Centrality and Distance to NTCD. The analysis of indicator importance reveals that while the natural environment, social economy, and location and transportation dimensions have high overall scores, the policy support and tourism market dimensions also play a crucial role. Notably, the Bashu Corridor and Tourism Network Centrality rank first and fourth, respectively. This is because the implementation of tourism policies has promoted the transmission of regional traditional culture and strengthened the integration of characteristic industries, thereby fostering the growth of the tourism market and the local economy, which in turn has enhanced the location potential of traditional villages.

Evaluation method selection

The calculation methods of index weights are divided into subjective weighting methods, objective weighting methods, and combined weighting methods. This study adopts the entropy weight method, an objective weighting method, to calculate the index weights. This method has been widely applied in research on the tourism development of traditional villages22,45. To mitigate the influence of extreme and abnormal values on the entropy weight method, a [2%, 98%] confidence interval was applied during the min–max normalization of the indicators, thereby ensuring the robustness and rationality of the entropy weight calculation. From the results, it is observed that the weights of the Bashu Corridor, Terrain Relief, and Population Density are relatively significant, while those of the Tertiary Industry, NDVI, and Precipitation are relatively small. The entropy weight method determines the weights based on the degree of dispersion of the indicator data, which can effectively circumvent the interference of subjective factors; however, it might also overlook the inherent significance of the indicators. To balance the impact of subjective factors and objective data on the weighting results, a combined weighting approach can be employed, for instance, by combining expert scoring and the entropy weight method to calculate the combined weights46.

Findings of the spatial distribution characteristics

The spatial distribution of traditional villages is generally analyzed using kernel density and the nearest neighbor index4,13. Hua et al.47 found that traditional villages in Sichuan Province are clustered. This study reached the same conclusion and the spatial distribution characteristics are consistent with Hua et al.’s results. However, this study also performed analyses at the regional and city scales and found that the traditional villages are clustered at the regional scale, but at the city scale, the western and southern cities mainly present a clustered distribution, while the central and eastern cities mainly present a dispersed distribution. It can be seen that the clustering patterns of traditional villages vary at different scales, which also verifies the sensitivity of the spatio-temporal distribution of traditional villages to scale3. Furthermore, based on kernel density analysis, this study proposes a spatial pattern of “Six Cores and Five Belts,” which summarizes the spatial distribution characteristics of traditional villages in Sichuan Province. This finding suggests that, in the planning of traditional village tourism development, both provincial and city scale governments should adopt a clustered and contiguous development model, while also accounting for the effects of spatial scale.

Findings of the LPTD grade and spatial pattern

During the computation of the comprehensive LPTD score, a heatmap analysis was performed on the indicator scores for all villages. The results revealed that four cities, Aba, Ganzi, Liangshan, and Panzhihua, exhibited nearly opposite trends in the scores of all indicators compared with other cities. This is primarily attributed to substantial disparities in aspects such as the natural environment, geographical location, transportation, and social economy between the northwest of Sichuan and the Panxi region. Literature on the LPTD evaluation of traditional villages is scarce, and among them, studies at the regional scale are even rarer. Although Tao et al.22 evaluated the location of rural tourism investment across the entire Zhejiang Province, it focused on temporal evolution and did not include spatial analysis. Based on the comprehensive evaluation of LPTD, this study classifies traditional villages into three grades: low potential, medium potential, and high potential. In terms of spatial distribution, all high-potential villages are located within the Sichuan Basin, which is closely related to the basin’s superior natural environment, transportation network, and socio-economic conditions. Medium-potential villages are mainly distributed along the edges of the Sichuan Basin, in the eastern Sichuan hills, and in the central part of Ganzi Prefecture. Most of them are in hilly terrain, while the central part of Ganzi Prefecture has a higher potential compared with other areas in the northwest of Sichuan, mainly due to the popularity of the Sichuan-Xizang section of National Road 318 as a tourist route and the ongoing construction of the Sichuan-Xizang Railway, which has enhanced its location potential. Low-potential villages are mainly distributed in the northwest plateau of Sichuan, the mountainous areas of northeastern Sichuan, and the Panxi mountainous areas. They are located in remote areas with inconvenient transportation facilities and backward socio-economic conditions.

Spatial autocorrelation and association findings

Through spatial autocorrelation analysis, we found that at the provincial, regional, and city scales, the LPTD mainly shows significant positive spatial autocorrelation, with high–high and low–low clustering phenomena, forming one “hot area” and two “cold areas.” The “hot area” is located in the Sichuan Basin, including the Chengdu Plain, the southern part of South Sichuan, and the southern part of Northeast Sichuan. The “cold areas” are located in the northwest of Sichuan and the Panxi area. In combination with the classification results of LPTD grades, the “hot area” is basically consistent with the range of high-potential villages, and the “cold areas” roughly coincide with the range of low-potential villages. However, villages with medium potential generally do not have a significant aggregation trend, or the aggregation of high- and low-potential villages is not obvious. Analysis of the total gravity model reveals that the spatial interaction intensity classifications of traditional villages generally align with their LPTD classifications. That is, villages with high intensity have high potential, those with medium intensity have medium potential, and those with low intensity have low potential. This indicates that the greater the potential value and the more concentrated the spatial distribution of a village, the greater its regional influence, and the more it can drive the development of surrounding villages.

Results of the traditional village clustering

The formation and distribution of traditional village types are affected by a multitude factors, including nature, humanity, and history. Wu et al.3 investigated the influence of topography and climate in the Sichuan Basin on traditional village types. Fan et al.48 conducted a comparison of three types of traditional villages from the perspective of landscape space. Classifying traditional villages supports the preservation of traditional culture14. In this study, spatial clustering analysis was used to group the villages into four types based on spatial proximity and indicator attributes. Villages within the same category are geographically adjacent and share similar LPTD and indicator characteristics, while significant differences exist between categories. The LPTD advantages of Type I and IV villages are pronounced, followed by Type III villages, Type II villages have the worst LPTD. This offers a novel perspective for the regionalized management of traditional village tourism development.

Strategies for location selection in tourism development

Based on the analysis of locational conditions, this study proposes strategies for the tourism development location selection of traditional villages in Sichuan Province from the following five aspects:

(1) Clustered and contiguous development model: The development model should take into account the “Six Cores and Five Belts” spatial distribution pattern of traditional villages, as well as their distribution at regional and city scales. Priority should be given to strengthening the development of key clusters, including Guangyuan–Bazhong, Ya’an–Meishan–Chengdu–Leshan, Zigong–Luzhou, Danba and Litang counties in Ganzi Prefecture, and the core area of Wenchuan County in Aba Prefecture, while promoting spillover effects to surrounding contiguous areas.

(2) Zoning by development potential level: The location potential of traditional villages in Sichuan Province is classified into three levels. Villages with high-level potential possess favorable locational conditions and should be prioritized for tourism development. Villages with medium-level potential may have deficiencies in certain indicators and can be considered selectively. At the provincial scale, priority areas include the Chengdu Plain, northern southern Sichuan, and southern northeastern Sichuan. At the regional scale, the Chengdu Plain and southern Sichuan are preferred; at the city scale, Chengdu, Deyang, Zigong, and Neijiang are recommended as focal areas.

(3) Priority to “Hot areas”: The clustering pattern of location potential should also be considered. “Hot areas” represent regions with a high concentration of potential, mainly distributed in the Sichuan Basin, whereas most of the northwestern region of Sichuan is classified as a “Cold area,” indicating low potential clusters.

(4) Priority to areas with strong influence: The gravitational pull of location potential reflects a village’s regional influence, particularly its strong connectivity with neighboring villages. Prioritizing such villages can promote broader regional development. Three zones of strong gravitational influence are identified: Chengdu–Deyang–Mianyang, Ya’an–Meishan–Leshan, and Zigong–Yibin–Luzhou–Neijiang, which should be emphasized in government planning and investment.

(5) Type-based development strategies: Traditional villages in Sichuan Province can be categorized into four types. Type I (Tourism-oriented villages) should focus on improving air quality and constructing new civil airports. Type II (Resource-based villages) require accelerated economic development, enhanced transportation infrastructure, and the development of high-grade tourist attractions; increased government policy support is essential. Type III (Ecology-oriented villages) should improve air quality, develop high-grade scenic areas, and seek targeted policy support. Type IV (Transportation-oriented villages) should prioritize the protection of natural landscapes, improve air quality, and enhance vegetation coverage.

Conclusion

This study analyzes the spatial distribution patterns, location potential, and spatial structures of 396 National-level recognized traditional villages in Sichuan Province, emphasizing the critical role of locational potential in tourism development. The findings offer valuable guidance for investment decisions and policy formulation related to the tourism development of traditional villages.

First, through spatial analysis methods such as kernel density estimation and nearest neighbor analysis, the study reveals for the first time that traditional villages in Sichuan Province exhibit a “Six Cores and Five Belts” spatial distribution pattern. Furthermore, different clustering modes are observed at the provincial, regional, and city scales. This finding underscores the necessity of adopting a “clustered and contiguous” development model while also accounting for spatial scale effects in planning. Second, drawing upon tourism geography, economic geography, and geographic information science, the study explores locational factors influencing traditional villages and constructs a multidimensional evaluation indicator system from five dimensions: natural environment, location and transportation, socio-economic conditions, tourism market, and policy support. The inclusion and demonstrated importance of policy indicators reflect their advantages and provide a methodological reference for constructing multi-criteria evaluation frameworks. Subsequently, a comprehensive quantitative assessment of LPTD for traditional villages in Sichuan was conducted. The results categorize the villages into three potential levels: high, medium, and low. High-potential villages are primarily concentrated in the Sichuan Basin, characterized by plains and hills, well-developed economies, high population density, and good transportation—indicating highly favorable location conditions. Medium-potential villages are mainly located along the edges of the Sichuan Basin and in central Ganzi Prefecture. Low-potential villages are distributed in northern Sichuan and the southwestern region, which are predominantly ethnic, plateau, and mountainous areas with limited economic development and poor accessibility. Third, spatial autocorrelation analysis was employed to explore clustering patterns of location potential. One “hot area” was identified in the Sichuan Basin, while two “cold areas” were found in northwestern Sichuan and the Panxi region. This highlights the spatial interdependence of location potential among traditional villages and suggests that surrounding villages’ potential should be considered in tourism planning. In addition, a gravity model was applied to examine the regional influence of traditional villages. Three major gravity centers were identified in the Chengdu Plain and southern Sichuan. Prioritizing the tourism development of villages within these zones could enhance regional location potential advantages. Finally, by integrating spatial constraints with cluster analysis, traditional villages in Sichuan were classified into four types, each with clearly defined strengths, weaknesses, and development paths. Compared with previous studies, this research offers several key innovations. Methodologically, it constructs a multidimensional indicator system that emphasizes policy factors. Theoretically, it expands the understanding of spatial patterns across multiple scales—provincial, regional, and city. Technically, it applies the gravity model from regional economics to the analysis of location potential and integrates spatial constraints with cluster analysis.

The conclusions derived from this study fill existing gaps and deepen the understanding of the spatial distribution and location potential patterns of traditional villages in Sichuan Province. The location selection strategies proposed based on these findings provide practical guidance for the tourism development of traditional villages in the region. The data used in this study are publicly available, the methods are widely applicable, and the results are reproducible, making them suitable for traditional village clusters worldwide. This study is particularly important for understanding the spatial characteristics of the LPTD of traditional villages of Sichuan Province. It also provides a framework for assessing and developing traditional villages in other regions of the world and offers guidance to local policymakers and researchers in the protection and revitalization of traditional villages.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study will be available in the Figshare upon publication, and can be accessed at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.29379089.

References

Li, B. H., Liu, P., Dou, Y. D., Zeng, C. & Chen, C. Research progress on transformation development of traditional villages’ human settlement in China. Geographical Res. 36 (10), 1886–1900 (2017). [CrossRef].

Timothy, D. J. & Nyaupane, G. P. (eds) Cultural Heritage and Tourism in the Developing World (Routledge, 2009).

Wu, C., Chen, M. & Zhou, L. Identifying the Spatiotemporal patterns of traditional villages in china: a multiscale perspective. Land 9 (11), 449 (2020). [CrossRef].

Bi, S., Du, J., Tian, Z. & Zhang, Y. Investigating the Spatial distribution mechanisms of traditional villages from the human geography region: A case study of jiangnan, China. Ecol. Inf. 81, 102649 (2024). [CrossRef].

Li, B., Lu, Y., Li, Y., Zuo, H. & Ding, Z. Research on the Spatiotemporal distribution characteristics and accessibility of traditional villages based on geographic information Systems—A case study of Shandong Province. China Land. 13 (7), 1049 (2024). [CrossRef].

Fu, J., Zhou, J. & Deng, Y. Heritage values of ancient vernacular residences in traditional villages in Western hunan, china: Spatial patterns and influencing factors. Build. Environ. 188, 107473 (2021). [CrossRef].

Zeng, J., Ge, J., Bai, M., Yao, M. & He, L. Toward classification-based sustainable revitalization: assessing the vitality of traditional villages. Land. Use Policy. 110, 105575 (2022). [CrossRef].

Gao, J. & Wu, B. Revitalizing traditional villages through rural tourism: A case study of Yuanjia village, Shaanxi province, China. Tour. Manag. 63, 223–233 (2017). [CrossRef].

Tang, C., Yang, Y., Liu, Y. & Xiao, X. Comprehensive evaluation of the cultural inheritance level of tourism-oriented traditional villages: the example of Beijing. Tourism Manage. Perspect. 48, 101166 (2023). [CrossRef].

Xu, Q. & Wang, J. Recognition of values of traditional villages in Southwest China for sustainable development: A case study of Liufang village. Sustainability 13 (14), 7569 (2021). [CrossRef].

Su, H., Wang, Y., Zhang, Z. & Dong, W. Characteristics and influencing factors of traditional village distribution in China. Land 11 (10), 1631 (2022). [CrossRef].

Prayitno, G. et al. Social capital for sustainable tourism development in Indonesia. Cogent Social Sci. 10 (1), 2293310 (2024). [CrossRef].

Li, Y., Ismail, A. & Aminuddin, A. M. A., How has rural tourism influenced the sustainable development of traditional villages? A systematic literature review. Heliyon, 10(4), e25627 (2024). [CrossRef].

Hua, Z. Z., Jamaludin, O. & Ing, D. S. A review on traditional villages protection and development in China. Construction 4 (2), 140–149 (2024). [CrossRef].

Adawiyah, W. R., Praptapa, A., Kusuma, P. D. I. & Sholikhah, Z. Promoting local potential as a strategy to develop tourism village. Geo J. Tourism Geosites. 31 (3), 1113–1118 (2020). [CrossRef].

Nugraha, Y. E. & Lema, E. C. Development strategy of Matalafang traditional village as a cultural tourism destination. Development, 4(1), 61–74 (2021). [CrossRef].

Zhang, S., Li, Z. & Liu, S. Exploring the tourism development potential and distinctive features of traditional wooden architecture in central hunan: A case study of 18 villages. Sustainability 17 (6), 2573 (2025). [CrossRef].

Arintoko, A., Ahmad, A. A., Gunawan, D. S. & Supadi, S. Community-based tourism village development strategies: A case of Borobudur tourism village area, Indonesia. Geo J. Tourism Geosites. 29 (2), 398–413 (2020). [CrossRef].

Meng, Q., Wang, C., Xu, T., Pi, H. & Wei, Y. Evaluation of the sustainable development of traditional ethnic village tourist destinations: a case study of Jiaju Tibetan village in Danba county, China. Land 11 (7), 1008 (2022). [CrossRef].

Liu, H., Zhang, Y., Wang, S. & Zhao, H. Comprehensive evaluation of digital village development in the context of rural revitalization: A case study from Jiangxi Province of China. Plos One. 19 (5), e0303847 (2024). [CrossRef].

Gherdan, A. E. M. et al. Sustainable Tourism Development in Mountain Regions: A Case Study of Peștera Village, Brasov County, Applying the Analytic Hierarchy Process. Sustainability (2071 – 1050), 17(4). [CrossRef] (2025).

Tao, L., Lei, W. & Qiushi, G. Evolution pattern of rural tourism investment location choice from the perspective of Human-Land relationship system: based on a case study of Zhejiang province, China. J. Resour. Ecol. 15 (3), 576–586 (2024). [CrossRef].

Kpeebi, Y. & Evans, K. Understanding the Spatial distribution of tiny house villages for the homeless and the contextual factors underlying their establishment in the united States. GeoJournal 90 (1), 20 (2025). [CrossRef].

Chen, H., Xiao, D., Li, J. & Liu, Y. Study on the distribution characteristics and formation mechanism of traditional village names in Southeast Guizhou. Npj Herit. Sci. 13 (1), 1–25 (2025). [CrossRef].

Bao, W. & Liu, Y. Spatial characteristics and influencing factors of traditional villages distribution in the yellow river basin. Sustainability 17 (11), 4834 (2025). [CrossRef].