Abstract

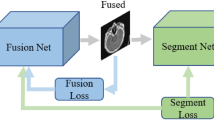

Multi-Modal Medical Image Fusion (MMMIF) has become increasingly important in clinical applications, as it enables the integration of complementary information from different imaging modalities to support more accurate diagnosis and treatment planning. The primary objective of Medical Image Fusion (MIF) is to generate a fused image that retains the most informative features from the Source Images (SI), thereby enhancing the reliability of clinical decision-making systems. However, due to inherent limitations in individual imaging modalities—such as poor spatial resolution in functional images or low contrast in anatomical scans—fused images can suffer from information degradation or distortion. To address these limitations, this study proposes a novel fusion framework that integrates the Non-Subsampled Shearlet Transform (NSST) with a Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) for effective sub-band enhancement and image reconstruction. Initially, each source image is decomposed into Low-Frequency Coefficients (LFC) and multiple High-Frequency Coefficients (HFC) using NSST. The proposed Concurrent Denoising and Enhancement Network (CDEN) is then applied to these sub-bands to suppress noise and enhance critical structural details. The enhanced LFCs are fused using an AlexNet-based activity-level fusion model, while the enhanced HFCs are combined using a Pulse Coupled Neural Network (PCNN) guided by a Novel Sum-Modified Laplacian (NSML) metric. Finally, the fused image is reconstructed via Inverse-NSST (I-NSST). Experimental results prove that the proposed method outperforms existing fusion algorithms, achieving approximately 16.5% higher performance in terms of the QAB/F (edge preservation) metric, along with strong results across both subjective visual assessments and objective quality indices.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Image Fusion (IF) is vital in several image processing tasks such as medical imaging, study, and remote sensing, where images are captured from multiple sources. The main objective of IF is to combine key data from multiple Source Images (SI) into a single image that contains richer data than any individual SI1. These SI may be collected at different epochs or from different sensors. As a result, certain regions may be limited in some images, while others may display different physical features. Therefore, IF is predicted to provide a more accurate view and advantage to human and Computer Vision (CV) applications2,3. Suppose are typically classified into three levels: pixel, feature, and decision. According to4, Feature-Level Fusion (FLF) captures differences in factors such as shape, color, texture, and edges and integrates differences based on feature resemblance. In FLF, each SI contributes distinct features. Decision-Level Fusion (DLF) aggregates high-level results from different algorithms to complete the fusion task. In DLF, each image is processed separately and then combined during the fusion process.

According to Feature Extraction (FE), DLF separates pixels from multiple source images (SIs) and assigns a proper class label to each pixel5. Pixel-Level Fusion (PLF) preserves the spatial features of pixels in the SIs. As a result, several PLF-based Image Fusion Methods (IFM) have been recently introduced. Two main types of PLF are the Transform Domain-Based Image Fusion Method (TDBIFM) and the Spatial Domain-Based Image Fusion Method (SDBIFM), classified based on their operational domain. Both TDBIFM and SDBIFM produce fused images (IF)6,7. Demonstrative SDBIFM such as Principal Component Analysis (PCA), maximum selection, and simple averaging8. While these methods are simple and computationally efficient, they frequently suffer from spectral distortion and reduced contrast in the fused image. Therefore, pure SDBIFM is now rarely used. Unlike SDBIFM, TDBIFM generally follows a three-phase model. First, the source images are transformed into the frequency domain to generate sub-images. These typically include purpose images, signified by Low-Frequency Coefficients (LFC), and detail images, represented by High-Frequency Coefficients (HFC). Second, specific fusion rules are applied to corresponding sub-bands. Finally, the fused image is restored9.

Spatial Domain Fusion Methods (SDFM) frequently result in reduced contrast and distortion of spectral features in the fused images10. Consequently, the transform domain has become the attention of significant IF research. Among the early methods, the Laplacian pyramid and its deviations have been commonly useful for multi-sensor data fusion11,12. However, these methods frequently suffer from blocking objects due to a lack of spatial orientation selectivity during the decomposition process13. The Wavelet Transform (WT) has also been used in IF methods, where it effectively preserves spectral features and produces superior fusion results. While WT captures 1D point singularities, it fails to address more complex features, such as curves and line individualities14.

To overcome this limitation, Multi-Scale Geometric Analysis Methodologies (MAGAM), such as the Shearlet Transform (ST) and Contourlet Transform (CT), have been developed15. These methods show strong directional selectivity and anisotropic selection. Among them, the Non-Subsampled Contourlet Transform (NSCT) proposes translation invariance and is effective in mitigating the Gibbs phenomenon experimental in previous transforms. However, NSCT incurs a high computation cost, has a large data footprint, and lacks real-time performance efficiency. In comparison, the Shearlet Transform (ST)16 achieves better fusion results and computational efficiency due to its more flexible design17. The Non-Subsampled Shearlet Transform (NSST) further improves directional selectivity and maintains shift invariance. Building upon these improvements, several Medical Image Fusion (MIF) have recently incorporated NSST18. Moreover, the integration of Soft Computing-Based Methods (SCBM) in Multi-Modal Medical Image Fusion (MMMIF) has also gained attention alongside SDBIFM + TDBIFM.

Numerous demonstrative models have been successfully applied in MIF, including Dictionary Learning Models (DLM)19,20, Compressed Sensing (CS)21, Total Variation (TV)22, Fuzzy Theory (FT)23, Gray Wolf Optimization (GWO)24, Genetic Algorithm (GA)25, Guided Filter (GF)26, Sparse Representation (SR)27, Pulse Coupled Neural Network (PCNN)28, methods based on local extrema, structure tensor, and Otsu’s29,30,31. These models have each contributed to enhancing the accuracy of IF, noise suppression, and structural preservation in multimodal settings.

Assuming the promising results achieved by TDBIFM and SCBM, recent research has focused on hybrid approaches. For example, the integration of interval Type-2 fuzzy sets with NSST has been proposed for multi-sensor IF32. An IF based on Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) and enhanced Fuzzy Logic (FL) within the NSST domain has also been developed33. In another study, NSST was combined with GWO to hypothesize a novel IF34. The authors in35 utilized NSST to decompose the SI, followed by sub-IF using sparse representation and dictionary learning. For MIF specifically, NSST-based methods employing PCNN have also been proposed26,36. Additionally,37 introduced a hybrid IF that leverages the advantages of the Spatial Domain (SD) and the Transform Domain (TD). The overall trends and advancements in practical IF for medical imaging have been reviewed in38,39.

Deep Learning (DL) has made significant improvements in recent years across a wide range of CV and image processing tasks, including super-resolution, image segmentation, saliency detection, and classification27. Since 2012, several Deep Convolutional Neural Networks (DCNN) have been introduced, such as ResNet40, DenseNet41, AlexNet42, VGG43, ZFNet44, Fully Convolutional Network (FCN)45, GoogLeNet46, and U-Net47. These networks have proved impressive performance in image classification, segmentation, object detection, and tracking while also presenting novel visions for IF tasks.

The success of DL over conventional Machine Learning (ML) can be attributed to four key factors:

-

(a)

First, advancements in Neural Networks (NNs) have enabled DL to learn high-level features directly from data, disregarding the requirement for complex feature engineering and domain-specific knowledge. This allows DL to propose end-to-end solutions.

-

(b)

Second, the development of Graphics Processing Units (GPU) and supporting GPU-computing libraries has significantly accelerated training speeds—up to 10–30 times faster than on traditional Central Processing Units (CPU). Additionally, open-source mold provides practical implementations for efficient GPU utilization.

-

(c)

Third, publicly available benchmark datasets, such as ImageNet, have enabled researchers to train and validate DL models using large-scale datasets.

-

(d)

Lastly, the introduction of effective optimization methods—such as batch normalization, dropout, the Adam optimizer, and Rectified Linear Unit (ReLU) activation functions—has improved training stability and performance, further contributing to DL’s common success.

A unique Multi-Focus Image Fusion Method (MFIFM) based on CNN was proposed in48, where CNN was used to classify focused regions and generate a decision map. This decision map was then combined with the SI to complete the IF process. Although this method proved superior performance, its applicability was limited to MFIFM tasks. Subsequently, CNNs were extended to all-purpose MIF with promising outcomes. For example,49 introduced a CNN-based approach that generated Weight Maps (WM) to fuse pixel activity data from input SIs.

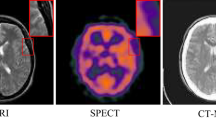

There are numerous types of MIF tasks, including the integration of Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI), Computed Tomography (CT), T1- and T2-weighted MRI (based on specific relaxation times), Positron Emission Tomography (PET), and Single-Photon Emission Computed Tomography (SPECT). However, a significant limitation of the CNN-based method is its difficulty in handling complex fusion tasks, such as multi-focus and infrared–visible IF.

To improve classification accuracy,50 invented a DCNN combined with a Discrete Gravitational Search Algorithm (DGSA). This model was evaluated on 4 distinct datasets (I–IV) consisting of modalities such as CT, SPECT, and MRI. Performance was assessed using metrics including sensitivity, precision, accuracy, specificity, spatial frequency, and fusion factor. Despite its effectiveness, deploying this method in real-time applications remains a significant challenge.

The Pulse Coupled Neural Network (PCNN), a biologically inspired neural model developed in recent years51, has been effectively applied to several image-processing tasks. In IF, PCNN is often combined with transformation methods to form a hybrid IF. Although these methods yield reliable results, they share common limitations, such as contrast reduction and the occasional loss of subtle yet critical feature data52,53. In PCNN-based IF, neurons are predominantly activated by single-pixel coefficients derived from either the SD or TD.

To address these problems, the proposed Medical Image Fusion Method (MIFM) incorporates regional energy in the LFC fusion process using the NSST domain. The fusion of HFC within NSST is achieved using PCNN, where the neuron activation is focused by the Novel Sum Modified Laplacian (NSML)54 as the input stimulus.

Among the available transforms, the Shearlet Transform (ST) and its hybrid variants have emerged in the literature as strong candidates for solving MIF problems. However, TDBIFM methods may still introduce frequency bias in the fused image. In contrast, DL has proved superior performance in a standard range of ML and signal processing tasks, especially when trained on large datasets. The representational power of Deep Neural Networks (DNN) has driven recent progress in denoising and FE55, and DL is gradually being accepted to address problems involving unknown or highly nonlinear input–output mappings56.

Recent advancements in MIF have increasingly employed FL to manage uncertainty and preserve structural details across modalities. In57, the authors proposed a lightweight IFM that combines Laplacian pyramid decomposition with a novel similarity measure based on intuitionistic Fuzzy Set Theory (FST), achieving superior detail retention with low computational complexity. Extending FL to quality evaluation,58 introduced a multiscale fuzzy assessment model for multi-focus IF, emphasizing sharpness-aware performance metrics. In59, FST was combined with compensation dictionary learning to improve cross-modal consistency and enhance edge fidelity in complex anatomical regions. Further,60 developed an intuitionistic fuzzy cross-correlation mechanism to optimize non-membership relations during fusion, while their subsequent FFSWOAF61 employed Fermatean fuzzy sets integrated with whale optimization to refine fusion rule selection adaptively. Complementing these algorithmic advances,62 presented a comprehensive survey of fuzzy-driven fusion methods, underscoring the growing impact of fuzzy set extensions—such as intuitionistic and Fermatean models—in enhancing the interpretability and diagnostic relevance of fused outputs.

While several DL and TD methods have been proposed for MIF, existing methods often employ uniform IFM across all decomposed sub-bands or overlook sub-band-specific restoration, resulting in degraded structural preservation and loss of modality-specific detail. In contrast, this work introduces a novel IFM that integrates the NSST with a deep, sub-band-specific enhancement architecture termed the Concurrent Denoising and Enhancement Network (CDEN). The core novelty lies in applying dedicated learning-based enhancement operations separately to Low-Frequency Sub-Bands (LFSB) and High-Frequency Sub-Bands (HFSB) before fusion, rather than performing direct fusion over unprocessed decomposed coefficients as seen in prior NSSTs such as NSST-SNN and FFST-SR-PCNN.

Specifically, the proposed model employs a dual-branch CDEN, where the DNSN branch suppresses sub-band-specific degradations (e.g., Gaussian or sensor noise), and the ENSN branch enhances discriminative details required for modality complementarity. This network is trained with a composite loss that combines mean squared reconstruction error and Softmax-based cross-entropy to optimize perceptual fidelity and semantic separation jointly. For LFSB, the model introduces a novel activity map generation process using AlexNet’s early convolutional layers, effectively guiding the fusion based on salient anatomical networks. Unlike entropy- or gradient-based activity measures, this feature-level weighting captures global semantic relevance with minimal computational overhead.

For HFSB, a biologically inspired Pulse Coupled Neural Network (PCNN) fusion method is deployed, where neuron firing is modulated by a Novel Sum-Modified Laplacian (NSML) to enhance edge saliency and suppress irrelevant high-frequency distortions. This combination ensures that sharp anatomical boundaries are retained while suppressing the fusion of objects. Crucially, the entire enhancement-fusion process is applied within the transform domain, preserving directional and scale-specific data extracted by NSST.

Moreover, the proposed method is the first to apply a joint denoising-enhancement network tailored to frequency-separated sub-bands within an NSST, presenting a principled and learnable alternative to hand-crafted or static fusion rules. Quantitative results across multiple medical image modalities demonstrate significant improvements over recent baselines, with a 9.64% gain in QAB/F and a 3.67% increase in SSIM, affirming the architectural advantage of sub-band restoration before fusion.

This integrated model, comprising NSST-based decomposition, frequency-specific enhancement via CDEN, semantic activity weighting from AlexNet, and biologically grounded PCNN fusion, represents a significant advancement in MMIF by addressing noise resilience and feature complementarity within a unified, end-to-end trainable pipeline.

This research aims to develop an IFM by integrating CNN and the NSST, addressing the significance and complexity of the MMIF problem. Initially, the input MMIF images are decomposed into LFSB and HFSB using NSST. The proposed Concurrent De-noising and Enhancement Network (CDEN-NN) is then applied to these sub-bands to perform noise reduction and enhance frequency detail35.

The fused image is subsequently reconstructed using the inverse NSST. For fusing the enhanced LFSBs from both images, an AlexNet-based IFM is employed, while the HFSBs are fused using the Novel Sum Modified Laplacian (NSML) and a PCNN-based IFM. A comprehensive comparison was conducted between the proposed method and several State-Of-The-Art IFMs. The results validate that the proposed model outperforms existing methods in terms of fusion quality and performance metrics63.

The remainder of this article is organized as follows: Section “Materials and methods” presents the materials and methods used; Section “Proposed CNN-shearlet fusion model” details the proposed methodology; Section “Experimental analysis” provides the experimental results and analysis; Section “Discussion” discusses the contributions and limitations; and Section “Conclusion and future work” concludes the study.

Materials and methods

Non-subsampled shearlet transform

The composite framework of Wavelet Theory (WT), which integrates multiscale analysis with classical geometric selections, includes the Shearlet Transform (ST) as a significant advancement64. The Shearlet transform provides an optimally sparse representation of images with distributed discontinuities and achieves near-optimal performance in Nonlinear Approximation (ONA) tasks50. Due to its strong directional sensitivity and localized time–frequency features, the ST has been widely applied in image processing tasks such as texture FE, image denoising, and IF.

The Discrete Shearlet Transform (DST) is constructed within the model of composite wavelet theory, incorporating multiscale decomposition and directional sensitivity. The DST system, as \(\mathcal{S}\mathcal{H}(\psi )\) is generated from a mother shearlet function \(\psi \in {L}^{2}\left({\mathbb{R}}^{2}\right)\) as Eq. (1)

where: \(j\) → The scale index, governing resolution refinement, \(l\) → the shear index, controlling directional selectivity, \(k\in {\mathbb{Z}}^{2}\) → the translation index, determining spatial location, \(\psi\) → the mother shearlet function, localized in space and frequency.

The matrices \(S\) and \(G\) are defined as Eq. (2):

where, \(S\)→ The anisotropic scaling matrix responsible for frequency refinement and redundancy. \(\text{G}\)→ The shear matrix that introduces directional selectivity by controlling the orientation angle in the transform domain.

Furthermore, distributed discontinuities in the SD are captured using the shift parameter ‘k’. When applying the Fourier transform to the SD Shearlet atom \({\psi }_{j,l,k}(x)\), the following expression is attained Eq. (3):

where: \(\omega = \left( {\omega_{1} ,\omega_{2} } \right) \in {\mathbb{R}}^{2}\) →The frequency vector, \(\hat{\psi }\) →The Fourier transform of the mother Shearlet ‘ψ’, \(S^{ - j}\), \(G^{ - l}\) →The inverse anisotropic scaling and shear matrices, \(\left\langle { \cdot , \cdot } \right\rangle\)→ The standard inner product.

The frequency support of \(\hat{\psi }_{j,l,k}\), which symbolizes its directional localization, is bounded as follows Eq. (4):

This support region forms a trapezoidal segment in the frequency domain, centered along the slope \(l{2}^{-j}\)with the angle controlled by the shear parameter ‘l’. These anisotropic and directional properties enable the shearlet system to represent edges and curves more effectively than traditional transforms, providing a sparse computation of images with distributed singularities (Fig. 1a,b).

Furthermore, distributed discontinuities in the SD are captured using the shift parameter ‘k’. When applying the Fourier transform to the SD Shearlet atom as \({\psi }_{j,l,k}(x)\), Eq. (5):

where: \(\omega =\left({\omega }_{1},{\omega }_{2}\right)\in {\mathbb{R}}^{2}\) →The frequency vector, \(\widehat{\psi }\) →The Fourier transform of the mother Shearlet \(\psi\), \({S}^{-j}\), \({G}^{-l}\) →The inverse anisotropic scaling and shear matrices, \(\langle \cdot ,\cdot \rangle\)→ The standard inner product.

The frequency support of \({\widehat{\psi }}_{j,l,k}\), which symbolizes its directional localization, is bounded as follows Eq. (6):

This support region forms a trapezoidal segment in the frequency domain, centered along the slope \(l{2}^{-j}\), with the angle controlled by the shear parameter ‘l’. These anisotropic and directional features enable the Shearlet to represent edges and curves more effectively than traditional transforms, providing a sparse computation of images with distributed singularities.

As the number of coefficients \(N\to \infty\), the asymptotic error of the Shearlet Transform (ST) approaches \({N}^{-2}(\text{Log}N{)}^{3}\) 67, enabling highly accurate selection of interferometric borders. In the frequency domain, the Shearlet also forms a Parseval frame65. The vital frequency support is defined by trapezoidal regions of size \({2}^{j}\times {2}^{2j}\), oriented along zero-crossing lines with slopes of \(-{2}^{-j}\). In the SD, the orientation corresponds to the slopes of \({2}^{-j}\). Shearlet elements can be uniquely distinguished based on their scale, location, and directional orientation. However, the transform exhibits rapid degradation in the spatial domain66.

The Shearlet Transform is particularly effective in interferogram filtering due to its high directional selectivity. Nevertheless, its implementation involves subsampling operations, which introduce spectral aliasing in the frequency domain and make the transform shift-variant in practice67. Directional filtering is achieved via shifted window functions, but the resulting subsampling often leads to reform objects such as Gibbs distortion68. To address these limitations, the NSST was developed, inspired by the Non-Subsampled Contourlet Transform. NSST replaces subsampling with convolution-based directional filtering, thereby eliminating spectral aliasing and ensuring shift-invariance. This improvement significantly reduces pseudo-Gibbs phenomena, resulting in more visually intuitive and diagnostically useful fused images. The NSST decomposition process consists of two main stages, as shown in Fig. 269.

Step 1: Multiscale Decomposition | The image is decomposed into HFC and LFC using a Non-Subsampled Pyramid (NSP). Do this step iteratively until the image is decomposed into j scales |

Step 2: Direction Localization | Non-subsampled shearing Filter Banks (NSSFB), which apply the shearing filter’s 2-D convolution and the HFC on the cartesian domain, are the foundation of direction localization. The NSST is shift-invariant because the convolution operation prevents subsampling |

Due to several specific advantages, NSST was selected over alternative multi-scale transforms such as DWT and NSCT. Unlike DWT, NSST provides shift-invariance, which prevents pseudo-Gibbs phenomena at tissue boundaries in medical images. Compared to NSCT, NSST proposals have comparable directional selectivity with lower computational complexity (approximately 40% faster processing time in typical implementations)70. Most importantly, NSST achieves superior sparse representation of curvilinear structures (with asymptotic approximation error of O(N−2) (Log N)3) compared to O(N−1) for wavelets, making it particularly effective for preserving anatomical boundaries in medical images71. These advantages make NSST an optimal transform basis for the proposed neural development method.

AlexNet

The 2012 ImageNet Large Scale Visual Recognition Challenge (ILSVRC) marked a significant breakthrough in visual object recognition, as the winning model introduced a deeper and wider CNN compared to the earlier LeNet72.

AlexNet significantly outperformed all traditional ML and CV in the ILSVRC, achieving unprecedented recognition accuracy (Fig. 3). The architecture consists of 8 learned layers, including 5-convolutional layers, 3-max-pooling layers, 2-local Response Normalization (LRN) layers, 2-Fully Connected (FC) layers, and a final SoftMax output layer. In the 1st convolutional layer, 64 large kernels are used to extract low-level features from the input image. This is followed by overlapping max-pooling layers applied after the 2nd and 3rd convolutional layers to reduce spatial dimensions while preserving feature integrity.

The 3rd convolutional layer uses a standard kernel size with 192 filters, followed by the 4th and 5th convolutional layers with 384 filters each, enabling deeper FE. These layers are connected directly without intermediate pooling. Another overlapping max-pooling layer follows the 5th convolutional layer. The output of this pooling layer is passed to the 1st-FC layer, while the 2nd-FC layer connects to a 1000-way SoftMax classifier corresponding to the 1000 class labels in the ILSVRC dataset.

AlexNet was selected for the LFSB fusion task over new models based on several domain-specific considerations73. While more recent networks propose superior depth, experimental evaluations presented that AlexNet provides an optimal balance between performance and efficiency for MIF. The key advantage in this context is AlexNet’s larger kernels in early layers (11 × 11, 5 × 5), which effectively capture the global network data predominant in low-frequency components74.

The five distinct convolutional layers also provide an ideal multi-level FE for generating the WM labelled in the IF process. The relatively simple model also facilitates faster training and testing, making it more suitable for clinical deployment where computational resources may be limited75.

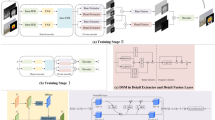

Proposed concurrent de-noising and enhancement network (CDEN)

The input to the proposed CDEN is a noisy decomposed frequency as \(\tilde{x}=x+n\), where ‘x’ → the clean signal; ‘n’ the noise component or signal perturbations introduced during decomposition76. It is essential to note that this configuration is employed exclusively during the training phase, enabling the model to learn the effective separation of clean and noisy components.

Targeted enhancement of each frequency sub-band is vital, as it specifies the distinct challenges associated with different spectral components in medical images. The LFSB preserves the primary structural information but frequently suffers from contrast degradation during multiscale decomposition. In contrast, the HFSB contains fine edge and texture features that are vital for clinical interpretation but are more vulnerable to noise contamination and structural distortion77,78,79.

De-noising sub-network (DNSN)

The first component of the proposed CDEN-NN is the De-noising Sub-Network (Fig. 4)), which aims to learn a mapping function as \(g_{{{\Theta }_{1} }} \left( {\tilde{x}} \right) = \overline{x}\), where \(\tilde{x}\) → the noisy input; \(\overline{x}\) → the predicted clean signal; \({\Theta }_{1}\) → the set of trainable parameters within the DNSN80. The training objective is to minimize the discrepancy between the predicted clean signal \(^{\prime}\overline{x}^{\prime}\) and the ground-truth clean signal ‘x’, thereby optimizing ‘θ1’ to accurately reconstruct the latent clean representation from noisy decomposed sub-band inputs. To achieve this, the network minimizes the Average Mean Squared Error (AMSE) loss defined as Eq. (7)

where: \({\Theta }_{1}\) →The parameter set of the DNSN, \(x_{i}\) →The ground truth (clean signal) for the \(i\)-th input, \(\overline{x}_{i}\) →The network-predicted denoised signal, \(N\) →The sum of training samples, \(\left\| \cdot \right\|_{2}\) →The Euclidean norm, \(\left\| \cdot \right\|_{F}\)→ The Frobenius norm.

The Frobenius norm formulation provides a compact method for expressing the overall discrepancy between the predicted and true signal matrices. These matrices are defined as Eq. (8):

where, Each Column \({\text{x}}_{\text{i}}\in {\mathbb{R}}^{\text{d}}\) → a single input signal sample. \(\text{d}\) →The feature measurement.

The proposed DNSN comprises a sequence of convolutional layers as \(D_{1}\) (Conv + ReLU blocks), followed by a final convolutional layer without activation. Each Conv + ReLU block contains 64 filters of size \(3\times 3\times c\), followed by a Rectified Linear Unit (ReLU) to introduce nonlinearity. In the 1st layer, the number of input channels ‘c’ may vary (1, 2, or 3) depending on the number of input polarizations used81, whereas all subsequent layers are standardized with \(c=64\). Since the target clean signal may include negative values, the final convolutional layer omits the ReLU activation to preserve the signal’s full range. Zero padding is applied throughout the subnetwork to ensure that the predicted output as ‘\(\bar{X}\)’ has the exact spatial dimensions as the ground-truth signal as ‘X’.

EnhanceNet sub-network (ENSN)

The ENSN generates a probability vector \({\mathbf{y}} = h_{{{\Theta }_{2} }} \left( {{\overline{\mathbf{x}}}} \right)\), from each input, \(`\overline{{\mathbf{X}}} ^{\prime}\). The predicted probability, which indicates that the original signal belongs to the matching class individually, is exposed by82 each element in ‘y’. ‘y’, the output vector is compelled to be near \(`{\hat{\mathbf{y}}}^{\prime},\) the one-hot vector, which stands for the input signal’s real label, to maximize performance83.

The objective function of the second network, known as the ENSN, is designed to optimize classification accuracy by minimizing the cross-entropy between the predicted and true label distributions Eq. (9):

where \({\Theta }_{2}\)→ The set of trainable parameters in the ENSN, \(\hat{y}_{i}\in \{{0,1}{\}}^{C}\) →The one-hot ground truth label vector for the \(i\)-th sample, \({y}_{i}\in [0,1]^{C}\)→The predicted probability distribution output from the network for the \(i\)-th sample, \(C\) is the number of classes, \(H\left( {\hat{y}_{i} ,y_{i} } \right)\) →The Cross-Entropy Function (CEF), defined as Eq. (10):

This loss penalizes deviations between the predicted class probabilities and the ground truth, encouraging the network to produce highly confident and correct classifications.

The training procedure for the feature improvement problem could be split into two parts. The DNSN is individually trained in the first part. For ENSN, the 1st sub-network generates training samples after training. \(\overline{\mathbf{X} } ,\) the hidden new signals are used to train the 2nd sub-network. First, x + n, a noisy feed, is fed into the DNSN during the test process. The extraction subnetwork is then fed with the predicted new signal \(\overline{\mathbf{X} }\) to produce the predicted label. Both sub-networks are trained simultaneously by integrating their Loss Functions (LF)84.

The total loss for the CDEN is defined as Eq. (11):

where:\(\bar{X}\), \(\text{X}\)→ The denoised prediction matrix and ground truth matrix respectively, Eq. (8), \(\text{H}\left({ \hat{y} }_{\text{i}},{\text{y}}_{\text{i}}\right)\) →The cross-entropy loss between the predicted class probability vector and the one-hot ground truth label (Eq. 10), \({\Theta }_{1}\), \({\Theta }_{2}\)→ The trainable parameters of DNSN and ENSN. \(\upgamma \in {\mathbb{R}}^{+}\)→’R'egularization coefficient that balances the contribution of the enhancement loss relative ‘t’ the denoising loss.

To achieve simultaneous signal denoising and enhancement, this study introduces an enhancement subnetwork, EnhanceNet56, whose network (Fig. 5). EnhanceNet is primarily composed of a pointwise \(1\times 1\) convolutional layer followed by a modified Inception Module (IM) variant. At the base of this network lies a squeeze convolutional block, which includes a \(1\times 1\) convolution layer, a Batch Normalization (BN) layer, and a ReLU6 activation function. This module is measured to reduce channel dimensionality and efficiently extract essential features. The modified IM implementation supports only asymmetric kernels of sizes \(1\times 1, 1\times 2,\text{ and }1\times 3,\text{ which significantly reduces}\) computational overhead between successive convolutional layers. EnhanceNet further integrates two convolution methods86: (1) a standard convolution block composed of a \(1\times 3\) Conv2D layer, followed by BN and ReLU6 activation, and (2) a depthwise separable convolution block that includes a \(1\times 3\) depthwise Conv2D layer, BN, and ReLU6. These components collectively improve FE while maintaining computational efficiency.

Following the depthwise convolution block, a channel attention mechanism is introduced to the network to enhance the extraction of salient feature data across channels. This module is fundamental as the output features at this stage consist of multiple channels with enriched contextual information. Drawing inspiration from the inverted residual network87, the attention block is strategically placed after the \(1\times 3\) depthwise convolutional layer to recalibrate channel-wise responses selectively. The input to the channel attention module is the feature map generated by the second \(1\times 3\) depthwise convolution layer, enabling the model to emphasize informative channels while suppressing less relevant ones88.

The Global Average Pooling Operation (GAPO) is employed in the channel attention module in Fig. 5 for compressing the FM with the size H × W in each channel into 11.

The GAPO’s output represents the corresponding channel’s global data. The output of the GAPO for the \({c}^{\text{th}}\) channel is computed as follows Eq. (12):

where: \({y}_{c}(i,j)\) →The activation value at spatial position, \((i,j)\) →The feature map (FM) corresponding to the \({c}^{\text{th}}\) channel, \(H\), \(W\)→ The height and width of the feature map.

This operation condenses spatial data from each feature map into a single scalar value, ‘xc’, representing the global descriptor for the \({c}^{\text{th}}\) channel. The resulting vector \(\mathbf{x}=\left[{x}_{1},{x}_{2},\dots ,{x}_{c}\right]\) is then passed through two FC layers. The 1st FC layer reduces the dimensionality from ‘c’ to ‘c/r’, where ‘r’ is a channel reduction ratio (tunable hyperparameter) to limit overfitting and computational complexity. This compressed extraction is subsequently activated by a ReLU function and passed to a 2nd FC layer, followed by a sigmoid activation to generate the channel attention weights.

The ReLU-AF covers the first FC layer 89, while the sigmoid AF covers the final one. The channel attention module processes the global descriptor vector \(\mathbf{x}\in {\mathbb{R}}^{c}\) (attained via GAPO) using two FC layers, a ReLU activation, and a sigmoid function to generate a channel-wise attention weight vector \(\mathbf{z}\in [\text{0,1}{]}^{c}\), as follows Eq. (13):

where: \({\mathbf{W}}_{1}\in {\mathbb{R}}^{\frac{c}{r}\times c}\)→ The weight matrix of the 1st FC layer, \(\delta (\cdot )\) →The ReLU activation function, \({\mathbf{W}}_{2}\in {\mathbb{R}}^{c\times \frac{c}{r}}\) →The weight matrix of the 2nd FC layer, \(\sigma (\cdot )\) →the sigmoid activation function that outputs the attention weights \({z}_{c}\in (\text{0,1})\) for each channel ‘c’.

Each attention weight as ‘zc’, then used to scale the corresponding feature map ‘yc’ from the previous convolutional layer, resulting in the reweighted output Eq. (14):

where: \({y}_{c}\)→The feature map of the \({c}^{\text{th}}\) channel, \({z}_{c}\) →The scalar attention weight for that channel, \({o}_{c}\) →The reweighted feature map emphasizes more informative channels.

This mechanism allows the model to selectively enhance discriminative feature maps while suppressing less relevant ones, thereby improving representation quality for downstream classification tasks.

The channel attention mechanism further improves FE by amplifying the channels that carry more discriminative information. It is followed by a pointwise convolutional block comprising a \(1\times\) 3 Conv2D layer and a Batch Normalization (BN) layer, with the output passed by a ReLU6 activation function ‘oc’90. To preserve gradient flow and support deeper network training, EnhanceNet includes an optional residual connection, which helps mitigate the vanishing gradient problem in deep architectures91. EnhanceNet is designed to be parameter-efficient by employing squeezed convolutions and depthwise separable convolutions, which significantly reduce the model’s computational complexity. Additionally, a 1 × 1 standard convolutional layer is employed to refine feature map clusters and enhance local FS. By delaying spatial down-sampling, the network maintains large activation maps that contribute to improved representational accuracy. The use of heterogeneous kernel sizes further enables multi-scale FE, enhancing the model’s capacity for robust and fine-grained feature learning.

LFC fusion method using AlexNet

LFSB and HFSB components primarily differ in content and fusion challenges, necessitating specialized mechanisms for addressing these differences. LFCs primarily contain structural and intensity data with higher Signal-to-Noise Ratios (SNR), making them suitable for deep FE by convolutional models92, such as AlexNet, which captures multi-scale structural relationships. Conversely, HFCs contain edge and texture details with lower SNR, making them particularly susceptible to noise amplification during fusion93. The PCN with NSML input is designed to address this challenge through its bioinspired temporal linking mechanism, which effectively decides between meaningful edges and noise in HFCs. This specialized treatment of each component type enables optimal balance between structural integrity and detail preservation, which is particularly crucial for multimodal medical images where complementary data appear in different frequency bands94.

In general, the LFC of a source image retains the principal structural components, while the HFC preserves finer details such as edges and textures. The traditional IMF frequently applies simple weighted averaging or maximum-value selection methods to the LFC, which neglects the contextual relationships among pixels and may result in suboptimal integration. To address these limitations, this study employs AlexNet for multi-layer FE from the source images. Subsequently, an Adaptive Selection Algorithm (ASA) is employed to generate optimized Weight Maps (WM), resulting in more effective and context-aware fusion compared to classical IFM95.

The LFC fusion process involves FE maps from AlexNet at multiple layers and computes activity-level maps that guide the generation of WM. This method is ruled by Eqs. (15) to (17) as follows Eq. (15):

where: \({I}_{k}\)→ \({k}^{\text{th}}\) source image, \({F}_{n}(\cdot )\)→ The transformation (Convolution + Activation) applied by the \({n}^{\text{th}}\) layer of AlexNet, \({f}_{k}^{(n,m)}\in {\mathbb{R}}^{H\times W\times m}\)→ The resulting feature map of spatial dimensions \(H\times W\) with \(m=64\cdot {2}^{n-1}\) channels.

The activity level map \({A}_{k}^{n}(x,y)\) for each spatial location \((x,y)\) is computed by applying the \({L}_{1}\)-norm across the depth dimension of the feature map Eq. (16):

To improve robustness to local variation and ensure spatial smoothness, the activity level map is smoothed using a block-wise average filter of radius ‘r’ as Eq. (17):

where: \(r\in {\mathbb{Z}}^{+}\)→ Controls the neighborhood size (set to \(r=1\) in proposed test results). \(\hat{A} _{k}^{n}(i,j)\) →The smoothed activity level map, which reflects the intensity of FE in the neighborhood around \((i,j)\).

These refined activity level maps are later used to construct adaptive WM that guide the fusion of LFSB.

The IFM employs multi-layer FE from AlexNet to compute activity-level maps that guide low-frequency fusion. The k-SI’s FM at the n layer is \({f}_{k}^{n,m}\), and the FM’s dimension is m, \(m =64\times {2}^{n - 1}\), \(k =2\), where \({F}_{n}\) specifies the layer in the AlexNet, and \(n\in \{1, 2, \text{3,4},5\}\), and [ReLU1, ReLU2,…,ReLU5] activation layer are represented by \(n\in \left\{1, 2, \text{3,4},5\right\}\). To make the IFM resilient to misregistration, \({l}_{1}\)-norm generates the activity level map known as \({A}_{k}^{n}(x,y)\) at position \((i, j)\). The final activity level map \({A}_{k}^{n}(x,y)\) is computed using the block-based average operator, where ‘r’ specifies the block size and is set to 1 to preserve more data96.

To construct the adaptive WM used for fusing the LFC, an Adaptive Selection Algorithm (ASA) is employed. The method begins by computing the ratio of the smoothed activity level maps between the two source images EQU (16):

This ratio \({t}_{n}(i,j)\) is used to compute the WM as \({W}_{1}^{n}(i,j)\) and \({W}_{2}^{n}(i,j)\) for each image as follows: Eqs. (19) and (20):

These formulations ensure that if \({t}_{n}(i,j)\to 0\), more weight is assumed to the second source image, and vice versa.

Since the feature maps from AlexNet are downsampled due to pooling operations, the weight maps must be upsampled to match the original spatial resolution of the source images97.

This is done using nearest-neighbor upsampling Eqs. (21) and (22):

where: \(\hat{W} _{k}^{n}\)→ The upsampled weight map, \(k\in \{\text{1,2}\}\)→ The image index, The upsampling factor \({2}^{n-1}\) aligns with the receptive field size of the AlexNet layer ‘n’

Using these upsampled WM98, the fused LFC at each layer is computed by weighted averaging Eq. (23):

Finally, across the multiple layers \(n\in \{\text{1,2},\text{3,4},5\}\), the fused coefficient at each spatial location is selected using a maximum activity rule Eq. (24):

This step ensures that all layers’ most salient fused features contribute to the final low-frequency fusion result.

HFC-fusion method using pulse-coupled neural network (PCNN)

The PCNN is a biologically inspired Feedback Neural Network (FNN) on the visual cortex of mammals99. It consists of a single-layer, 2-D array of neurons, where each neuron corresponds 1-to-1 with a pixel in the input image. In this network, spatially adjacent neurons interact within a defined local neighborhood, enabling localized feature improvement. From Fig. 6, each PCNN neuron comprises three core components: the receptive field, which receives external stimuli; the linking or modulation field, which facilitates inter-neuronal communication; and the pulse generator, which directs the neuron’s firing behavior based on internal dynamics and external input. Also, according to100, there is a split of the feed signal into the input and \({F}_{i,j}\) and linking \({L}_{i,j}\) Inputs.

The PCNN for IF is formulated as follows, where each neuron corresponds to a pixel at a spatial location \((i,j)\), and the PCNN evolves over discrete time steps \(n\in \left\{\text{1,2},\dots ,{n}_{\text{max}}\right\}\) as implicit in Eqs. (25) to (29).

where, \({F}_{i,j}[n]\) →Feeding input at position \((i,j)\) at iteration ‘n’, composed of the static input \({S}_{i,j}\), its decayed past value, and the effect from neighboring neuron firings via synaptic weights \({M}_{i,j,k,l}\). \({L}_{i,j}[n]\) →Linking input, decayed over time and influenced by neighboring outputs via weights \({W}_{i,j,k,l}\). \({U}_{i,j}[n]\) →Internal activity (modulated signal) combining feeding and linking with a linking strength co-efficient \(\beta\). \({T}_{i,j}[n]\) →Dynamic threshold, decays over time and increases upon firing. \({Y}_{i,j}[n]\) →Output pulse; a binary indicator of neuron firing at time ‘n’. \({\alpha }_{F},{\alpha }_{L},{\alpha }_{T}\) →Decay coefficients for feeding, linking, and threshold signals. \({V}_{F},{V}_{L},{V}_{T}\) →Normalization constants scaling the influence of previous outputs. ( \(k,l\) )→Indices of neighboring pixels in the spatial neighborhood. \({n}_{\text{Max}}\) →Maximum number of iterations.

Six parameters, including three degeneration factors \(\left({\alpha }_{F},{\alpha }_{L},{\alpha }_{T}\right)\) and three normalizing constants \(\left({V}_{F},{V}_{L},{V}_{T}\right)\) for the feeding (\({F}_{i,j}\)), linking (\({L}_{i,j}\)), and threshold (\({T}_{i,j}\)) inputs are acquired using the PCNN, which consists of a feeding and linking field. \({U}_{i,j}\) stands for the neuron’s internal activity (linking modulation) in Eqs. (26) to (28) (Tij, Yij) for the dynamic threshold and the neurons’ pulse output. An important factor that alters the linking field’s weight is the linking parameter ‘β’. The HFC’s Novel Sum-Modified LAPLACIAN (NSML) measures and assesses contrast levels to satisfy the HVS requirement.

Compute the NSML for the HFSB as follows: Eqs. (30) and (31):

where:\(H{F}_{Z}^{NSST}(i,j)\) →HFC from modality \(Z\) (e.g., CT or MRI) at pixel location \((i,j)\), attained by NSST. \(F(i,j)\) →Local contrast magnitude at pixel \((i,j)\) computed using modified Laplacian operators. \(w(a,b)\) →Normalized window function used in local contrast aggregation, has the following Eq. (32):

To activate the PCNN, use the following Eq. (33) and set up the neuron’s pulse with the help of each HFSB’s NSML:

where: \(Z\) →Source modality (e.g., CT or MRI). \((i,j)\) →Pixel coordinates. \({F}_{i,j}^{Z}[n]\) →Feeding input derived from NSML for modality \(Z\). \({L}_{i,j}^{Z}[n]\) →Linking input aggregating neighborhood activity. \({U}_{i,j}^{Z}[n]\) →Internal activity (modulated product of feeding and linking inputs). \({T}_{i,j}^{Z}[n]\) →Dynamic threshold for neuron firing. \({Y}_{i,j}^{Z}[n]\) →Binary neuron output (firing decision). \({\alpha }_{L},{\alpha }_{T}\) →Decay rates for linking input and threshold. \({V}_{L},{V}_{T}\) →Normalization constants. \(\beta\) →Linking modulation coefficient. \({W}_{i,j,k,l}^{Z}\) →Synaptic weights connecting neighboring neurons.

In the iterative process of the PCNN, a neuron’s firing is found by whether its internal activity \({U}_{i,j}^{Z}[n]\) exceeds the dynamic threshold \({T}_{i,j}^{Z}[n]\).

This condition generates the binary firing output \({Y}_{i,j}^{Z}[n]\in \{\text{0,1}\}\) as defined in Eq. (29). Over \({n}_{\text{Max}}\) iterations, the total firing time map is computed by collecting the number of times each neuron fires, Eq. (34):

where: \({t}_{i,j}^{Z}[n]\) →The cumulative firing count at pixel \((i,j)\) up to iteration ‘n’, \({Y}_{i,j}^{Z}[n]=1\) if \({U}_{i,j}^{Z}[n]>{T}_{i,j}^{Z}[n]\), and 0 otherwise, This summation reflects the number of times a neuron at location \((i,j)\) was activated across the PCNN evolution.

At the decision of the iterations (i.e., when \(n={n}_{\text{Max}}\)), the final firing times \({t}_{i,j}^{X}\left[{n}_{\text{Max}}\right]\) and \({t}_{i,j}^{Y}\left[{n}_{\text{Max}}\right]\) are used as a decision measure to select the most salient co-efficient from the HFSB of the input images101.

The fusion rule is defined in Eq. (35):

This decision rule ensures that for each pixel ( \(i,j\) ), the fused HFC is taken from the source image whose PCNN neuron exhibits robust and more reliable firing behavior, indicating higher local saliency, such as edges or texture elements102.

Proposed CNN-shearlet fusion model

The proposed IMM (Fig. 7) is written as follows for MMIFM and for implementing the abovementioned concept: Let’s use ‘X’ as the first image and ‘Y’ as the second.

Step 1: | Decompose the CT and MRI images (\({\varvec{X}}={{\varvec{X}}}_{{\varvec{i}}{\varvec{j}}}\) and \({\varvec{Y}}={{\varvec{Y}}}_{{\varvec{i}}{\varvec{j}}}\)) to produce LFC {\({{\varvec{L}}}_{{\varvec{x}}},{{\varvec{L}}}_{{\varvec{y}}}\)} and a series of HFC {\({\varvec{c}},{{\varvec{H}}}_{{\varvec{y}}}\}\) for each K-scale and l-direction, where 1 ≤ k ≤ K |

Step 2: | Input the LFC and HFC using the loss function in EQU (5) to the denoising network for obtaining noise-free {\({L}_{\overline{x} },{L}_{\overline{y} }\)} and noise-free HFC {\({H}_{\overline{x} },{H}_{\overline{y} }\)} |

Step 3: | Improve features with EnhanceNet, and the EnhanceNet generates a probability vector {\(L_{{x}} ,L_{{y}}\)} and {\(H_{{x}} ,H_{{y}}\) for each noise-free input, {\({L}_{\overline{x} },{L}_{\overline{y} }\)} and {\({H}_{\overline{x} }^{l,k},{H}_{\overline{y} }^{l,k}\}\). The predicted probability that each part of \({{x}}, {{y}}\) is the original signal belongs to the parallel region of interest. Each element in \({{x}}, {{y}}\) is the original signal’s predictable probability that belongs to the corresponding region of interest. Using objective function 6, the output vectors must be near the one-hot vectors that indicate the input signal’s accurate label to maximize performance103 |

Step 4: | Assuming the FE from both images, the DL fuses the LFC. The AlexNet that could select the LFC adaptively generates the WM \({L}_{\text{Fused }}(i,j)=Max\left[{L}_{\text{fised }}^{n}(i,j),n\in \{\text{1,2},\text{3,4},5\}\right]\) (34) |

Step 5: | Compute the NSML for the HFSB. To activate the PCNN, increase the neuron pulse and compute the NSML of each HFSB |

If n = nMax, the iteration ends, and the firing timings based on the next fusion rule are used to fuse the HFSB image coefficients. Using EQU (35), the firing times \({t}_{i,j}^{Z}[n]\) in 'n' iteration is evaluated \({H}_{Fused}=\left\{\begin{array}{c}{H}_{x};\hspace{0.25em}\hspace{0.25em}\hspace{0.25em}\hspace{0.25em} \, {\text{i}}{\text{f}} \, {t}_{i,j}^{X}\left[{n}_{max}\right]\ge {t}_{i,j}^{Y}\left[{n}_{max}\right]\\ {H}_{y};\hspace{0.25em}\hspace{0.25em}\hspace{0.25em}\hspace{0.25em} \, {\text{i}}{\text{f}} \, {t}_{i,j}^{X}\left[{n}_{max}\right]<{t}_{i,j}^{Y}\left[{n}_{max}\right]\end{array}\right.\) (35) | |

Step 6: | To generate the IF, perform INSST to combine the LFC and HFC, EQU (36) \({Image}_{Fused}=NSS{T}^{-1}\left({L}_{Fused},{H}_{Fused}\right)\) (36) |

Experimental analysis

The experimental study used a simulation tool of MATLAB R2022a and Python 3.11 software on a 64-bit Windows 10 operating system. The system was specified with a GTX 1080 GPU with 2560 CUDA cores and 8 GB of GDDR5X GPU memory. Moreover, the system has a 3.70 GHz Core i7 CPU and 32 GB of RAM. To assess the effectiveness of the proposed NSST + CNN for MMIF, its performance was compared with five different ultramodern IFS, including:

-

A.

Method 1: The Singular Value Decomposition (SVD) on the ST domain was used in SVD-Shearlet, a novel MIF104, to enhance the information content of an image using IF. The proposed method uses ST first to transform the SI into a Shearlet image. Subsequently, using the SVD in the LFSB, the changed sub-bands are selected by local features. SVD is used to process the composition of different HFSB coefficients. The LFSB and HFSB are then fused. Lastly, the Inverse Shearlet Transform reconstructs the IF (IST).

-

B.

Method 2: A new IMF for MR and CT medical images is proposed by NSST-SNN105, which uses NSST and spiking neural network features. The NSST is used to effectively create image coefficients, such as a new image with distinct features. First, the NSST decomposes the SI of MR and CT images into some sub-images. The LFC is fused using regional energy. Moreover, HFC that used a pulse-coupled NN, a type of NN with bioinspiration, is fused. Moreover, it maintains the SI’s edges and detailed information. The INSST is finally used to generate IF.

-

C.

Method 3: An IMF relying upon sparse representation and Fast Finite Shearlet Transform (FFST) is presented in FFST-SR-PCNN to address the problem of poor edge clarity, which makes it difficult for current algorithms to maintain the details of the SI. Initially, FFST decomposes the SI into LFC and HFC. Secondly, the LFC is trained using the K-SVD to generate the overcomplete dictionary D, and then the LFC is sparsely encoded using the OMP algorithm to complete the LFC fusion. The fusion coefficient of the HFC is then selected based on the number of ignitions, and an HFC is then used to excite a PCNN. The FFST inverse transform is then used to reconstruct the fused LFC and HFC into the MIF.

-

D.

Method 4: A novel IMF to CT and MRI medical imaging called CNN + DCSCM is based on CNNs and a Dual-Channel Spiking Cortical Model (DCSCM). Initially, the SI gets decomposed into an LFC and a series of HFCs using NSST. Second, the HFC gets fused through DCSCM, in which the modified average gradient of an HFC is used as the input stimulus. Third, the LFC gets fused by CNN, wherein WM is generated by a series of FM and an adaptive selection rule. In the end, inverse NSST is used to recreate the IF.

-

E.

Method 5: RBM-EMBO is a novel IMF built upon concepts from DL and best thresholding. The best threshold for fusion rules in ST is decided using an Enhanced Monarch Butterfly Optimization (EMBO). Then, using FM and the data specified by the DL method’s extraction part, LFSB and HFSB are fused. Therefore, the IFM was shown using the Restricted Boltzmann Machine (RBM).

Applying 180 pairs of SI, the effectiveness of the proposed model is tested. The Harvard Medical School’s Whole Brain Atlas was used to compile the complete SI sample. A sample image set comprising CT, MRI, SPECT, and PET images was used in this study. Each SI’s gray and color scale spatial resolution is 512 × 512 pixels. The predictable 6 pairs of multimodal brain images, including CT, MRI, SPECT, and PET images, serve as a sample set for the experimental study results. The images in Pair I and Pair II are MR-T1 and MR-T2, MRI and PET are the images in Pair II, MR-T2, and SPECT are the images in Pair III, CT and MR-T2 are the images in Pair IV, MR-T2 is the image in Pair V, and MR-T1 and MR-T2 are the images in Pair VI.

Assessment metrics

Throughout this paper, four metrics, Margin Information Retention (QAB/F) and Spatial Frequency (SF), Mutual Information (MI), Image Quality Index (IQI), and Image Entropy (IE), and each is drawn from one of the five types selected for performing analysis on the combined results in an objective method.

A. Image Entropy (IE): IE is a tool that measures the volume of data in a SI. If a fused image’s entropy increases better than the SI, the fused images have more data.

The entropy is said by Shannon information as Eq. (37),

where, p (i)→ The gray level’s probability ranging between [0,…, L − 1].

B. Spatial Frequency: One more index that assesses an image’s overall activity and level of clarity is called Spatial Frequency (SF)106.

It is defined as Eq. (38)

where, RF→ The row frequency. CF→ The column frequency

These are assessed as Eqs. (39) and (40)

where, I(i, j)→The fused image’s gray level value. {M, N}→The image’s size. The better the fusion quality, the higher the spatial frequency.

C. Mutual Information (MI): A fused image’s quality is measured as Eqs. (41) to (42).

Where

where \({h}_{R}\left(u\right),{h}_{F}(v)\) stand as the normalized gray-level histograms for (\({x}_{R}\),\({x}_{F}\)). \({x}_{R}\), \({x}_{F}\) →Joint gray-level histogram is known as \({h}_{R,F}\). The reference image→ \({x}_{R}\), The fused image→ \({x}_{F}\).

If the fused image’s MI value is higher, it has more texture and detailed data.

D. Image Quality Index: The reference image (R) and fused image (F)'s Quality Index (IQI) is defined as Eq. (42)

where, \({\mu }_{F},{\mu }_{R}\) →The mean \(({\sigma }_{F}^{2}\), \({\sigma }_{R}^{2}\))→ The fused and reference images’ variance. (X, Y)→The two reference images. I→one-fused image, is employed in this study.

In order to evaluate the quality metric (\({Q}_{0}\)), \(IQI(X, F)\) and \(IQI(Y, F)\) are averaged, Eq. (44).

E. Margin Information Retention: How effectively the IFM performs in aspects of edge strength is provided as Eq. (45)

where, \({Q}^{AF}(i,j)={Q}_{g}^{AF}(i,j)+{Q}_{\alpha }^{AF}(i,j)\) →The values for edge strength and positioning preservation are exposed by \({Q}_{g}^{AF}\left(i,j\right)\) and \({Q}_{\alpha }^{AF}\left(i,j\right)\). \({Q}^{BF}\left(i,j\right)\) →likewise assessed.

To ensure statistical validity and robust performance evaluation, fivefold cross-validation was implemented on the dataset of 180 image pairs. The dataset was randomly partitioned into five equal subsets, with four subsets used for training and one for testing in each fold. The reported performance metrics represent the average across all five folds, ensuring the evaluation is not biased by any particular training–testing split. This cross-validation method confirms the generalizability of the proposed model across different image combinations within the neuroimaging domain107.

Table 1 and Fig. 8 present the comparative performance of the proposed CNN + Shearlet fusion model against existing approaches. The proposed model proves superior performance across multiple evaluation metrics, particularly in preserving detailed features while maintaining overall image quality.

-

Image Entropy (IE), the proposed method, achieves consistently higher values, indicating enhanced data content in the fused images. This is particularly evident in Pair IV (CT and MR-T2 images), where the proposed method achieves an IE of 5.67, compared to 5.64 for the best alternative method.

-

Spatial Frequency (SF), which measures an image’s overall activity level and clarity, significantly improves with the proposed approach. The proposed model achieves an SF value of 44.26 for Pair IV, signifying superior preservation of high-frequency components, which are critical for diagnostic detail. The higher SF values across all image pairs confirm the method’s effectiveness in maintaining spatial detail distribution—a crucial factor for clinical reading.

-

For edge data preservation, as measured by QAB/F, the proposed model achieves an average development of 16.5% compared to other algorithms. This substantial enhancement can be attributed to the directional FE capabilities of the EnhanceNet component, which effectively preserves boundary data between different tissue types, as highlighted in the red regions of Fig. 8.

-

Image Quality Index (IQI) values, which measure the similarity between source and IF, are consistently higher for the proposed model across all image pairs. With IQI values approaching unity (ranging from 0.47 to 0.58), the proposed model maintains better fidelity to the source images while effectively combining complementary data.

-

Mutual Information (MI) metrics further confirm the superior data transfer achieved by the proposed model, with consistently higher values indicating better preservation of source image content in the fusion result.

A graphical comparison in Fig. 8 reveals the precise advantages of the proposed model. Method 1 (SVD-Shearlet) displays blocking objects and fails to preserve detailed feature information, particularly in the highlighted regions. Method 2 (NSST + SNN) proves inadequate edge definition, particularly in Pairs I, III, IV, V, and VI, where acceptable anatomical boundaries appear blurred. Methods 3 (FFST + SR + PCNN) and Methods 4 (CNN + DCSCM) validate improved performance but still display insufficient edge clarity, as quantitatively confirmed by their lower QAB/F scores in Table 1. Method 5 (RBM + EMBO), despite presenting competitive performance in some metrics, generates images with low contrast in key regions, particularly noticeable in the upper proper portions of the IF.

In contrast, the proposed CNN + Shearlet model maintains optimal contrast levels, preserves fine structural details, and avoids introducing objects such as dark lines or blocking effects. The superior performance is particularly evident in the highlighted regions of Fig. 8, where the proposed method maintains clear tissue boundaries while preserving textural details in adjacent areas.

The comprehensive quantitative and qualitative analysis confirms that the proposed CNN + Shearlet fusion model outperforms existing methods across all evaluation metrics, significantly improving edge preservation (QAB/F) and feature detail retention (SF and IE).

Figure 9 presents the graphical analysis of the Average Running Time (ART) for the proposed method compared to several existing IFMs. Experimental results indicate that the proposed model achieved an ART of approximately 0.53 Sec. While this is slightly higher than Method 5, which reported an ART of 0.34 Sec., it remains significantly faster than the other evaluated methods.

Beyond execution speed, the proposed method proved superior fusion performance across a range of input images. The consistency and quality of the fused outputs underscore the model’s robustness and adaptability in handling diverse medical imaging modalities. In contrast, other approaches exhibited variability and instability, particularly when confronted with heterogeneous inputs. The proposed model achieved optimal thresholding performance, highlighting its potential for deployment in advanced medical imaging applications and intelligent diagnostic systems.

Comparison with recent fuzzy-based fusion methods

To further validate the effectiveness and generalizability of the proposed CNN + Shearlet fusion model, this section presents a comparative analysis against recent state-of-the-art fuzzy-based methods published after 2020. The following advanced fuzzy-based IMF were implemented and evaluated using identical test conditions and assessment metrics:

-

(a)

Intuitionistic Fuzzy Sets and Joint Laplacian Pyramid (IFSJLP): Jiang et al. (2023) proposed a lightweight multimodal medical IF that integrates a newly defined similarity measure from intuitionistic FST with Laplacian pyramid decomposition. Their method effectively captures and merges fuzzy features within HFSB and LFSB, achieving high fidelity and edge preservation.

-

(b)

Multiscale Fuzzy Quality Assessment (MFQA): The Authors developed a multi-focus IF based on a sophisticated multiscale quality evaluation mechanism. Their method utilizes FL to determine optimal fusion weights across various decomposition levels, with a focus on preserving edges and enhancing contrast.

-

(c)

Fuzzy Compensation Dictionary Learning (FCDL): Researchers presented an IF combining FST with compensation dictionary learning. This method addresses the limitations of traditional dictionary learning by incorporating fuzzy membership functions that adaptively manage local feature differences, particularly at boundaries between different tissues in medical images.

The quantitative comparison in Table 2 and Fig. 10 reveals several key insights regarding the performance of the proposed CNN + Shearlet method compared to recent fuzzy-based methods. Regarding structural preservation metrics, the proposed method consistently outperforms the fuzzy models. The SSIM values, which measure the structural similarity between the fused and reference images, average 0.925 for the proposed method, compared to 0.912, 0.903, and 0.903 for the FCDL, MFQA, and IFSJLP. This 1.3%-2.2% improvement in SSIM is particularly significant for MIF applications, where preserving anatomical structures is critical for accurate diagnosis. The superior structural preservation can be attributed to the directional selectivity of the Shearlet transform combined with the FE sizes of the proposed CDEN + NN. The feature preservation capability, measured by FSIM, follows a similar trend, with the proposed method achieving an average of 0.888 compared to 0.877 for the FCDL. This improvement is most pronounced in Pair II (CT and MRI) and Pair V (MR-T2), which contain complex tissue boundaries and fine anatomical details. The fuzzy-based methods, particularly IFSJLP and MFQA, have problems with FS in these challenging cases due to their limited directional sensitivity. All methods perform comparably for information transfer metrics (MI and IE), but the proposed method maintains a slight edge with an average MI of 3.58 compared to 3.40 for FCDL, the next best performer. The MFQA proves competitive performance in MI for specific image pairs (notably Pair II and Pair V), likely due to its multiscale quality assessment method that optimizes information retention across different scales. However, it fails to maintain this advantage consistently across all test cases. The edge selection capability, measured by QAB/F and SF, shows the proposed method’s significant advantage in handling directional features. The average QAB/F of 0.70 for the proposed method represents a 1.4% improvement over FCDL (0.69) and 4.5% over IFSJLP and MFQA (0.67). This advantage is most evident in Pair I and IV, which contain numerous fine-edge structures in brain ventricles and tissue boundaries. Signal fidelity, measured by PSNR, determines that the proposed method achieves an average of 36.78 dB, compared to 36.18 dB for FCDL, 35.84 dB for MFQA, and 35.84 dB for IFSJLP. The 0.6–0.94 dB improvement indicates better noise suppression while maintaining signal integrity. This is particularly important for clinical applications where noise objects could mask subtle pathological features. Interestingly, the performance patterns across different methods vary by image pair. For Pair III (MR-T2 and SPECT), the FCDL proves competitive performance in IE (5.02 vs. 5.01) and maintains close performance in SSIM (0.904 vs. 0.916). This proposes that the fuzzy compensation dictionary learning approach has particular strengths in handling the significant intensity differences characteristic of functional–anatomical image pairs. However, it still falls behind in edge preservation (SF and QAB/F) and overall signal fidelity (PSNR). The IFSJLP proves relatively robust performance in IE across several image pairs, reflecting its ability to preserve the overall information content. However, its performance in structural and feature preservation metrics (SSIM and FSIM) reliably lags behind that of the other methods, indicating limitations in maintaining the spatial integrity of important anatomical structures. The MFQA method validates competitive performance in Spatial Frequency (SF) for Pair II and Pair IV, indicating good detail preservation in specific cases. However, its inconsistent performance across other metrics and image pairs recommends that its quality assessment mechanism may not be adequately adaptive to the varied challenges of different modality combinations. Overall, the proposed CNN + Shearlet method proves consistent superiority across all evaluation metrics, with an average improvement of 3.67% over the baseline IFSJLP, compared to 1.96% and 0.57% improvements for FCDL and MFQA, respectively. This comprehensive performance advantage stems from the synergistic combination of precise directional decomposition provided by NSST and adaptive FS presented by the DL components, which addresses global and local features of the fusion challenge.

Ablation study

A comprehensive ablation study was conducted to systematically evaluate the contribution of each component in the proposed CNN + Shearlet fusion model. Based on the model, four model variants were implemented and compared:

-

A.

Baseline (NSST only): This variant uses only the NSST for the decomposition of input images into LFSB and HFSB components, followed by conventional fusion rules (maximum selection for HFSB coefficients and weighted averaging for LFSB coefficients) without any CNN-based processing. The fused components are then reconstructed using inverse.

-

B.

NSST. 2. NSST + DNSN: This variant incorporates the Denoising Subnet, as shown in Fig. 4 with NSST, but removes the EnhanceNet components from the model. LFSB and HFSB components from each source image undergo denoising in this configuration, but no FS is performed. The denoised components are then fused using AlexNet for low frequencies and NSML + PCNN for high frequencies.

-

C.

NSST + ENSN: This variant incorporates the EnhanceNet exposed in Fig. 5 with NSST but removes the Denoising Subnet components. The decomposed frequency components are directly fed to the EnhanceNet without prior denoising, followed by the same fusion method as the complete model. This configuration tests the importance of FS independent of denoising.

-

D.

Full Model (NSST + CDEN): The complete proposed method, as depicted in Fig. 6, incorporates NSST decomposition, followed by sequential Denoising and Enhancement of both frequency bands from both source images, and finally fusion using AlexNet for LFSB and NSML + PCNN for HFSB.

Table 3 presents the quantitative performance metrics for all four variants across the 6 test image pairs.

The ablation study results reveal several dynamic insights into the proposed model. The baseline NSST achieves acceptable performance due to the directional selectivity of the Shearlet transform; however, it has limitations in handling noise and preserving fine details. This is evident in its lower performance across all metrics, particularly in PSNR (33.42 dB) and structural similarity (SSIM: 0.864).

The NSST + DNSN difference proves significant improvement over the baseline in signal fidelity metrics (PSNR: + 1.85 dB on average), confirming the effectiveness of the denoising subnet in reducing noise objects while preserving the underlying signal model. The denoising process, governed by the loss function defined in EQU (5), effectively learns the mapping from noisy decomposed frequencies to their new counterparts. However, this variant still shows limited feature emphasis and contrast improvement capability without the enhancement stage.

The NSST + ENSN optional proves notable improvements in structural preservation (SSIM: 0.904) and feature similarity (FSIM: 0.871) compared to the baseline. This confirms that the channel attention mechanism of EnhanceNet effectively highlights diagnostically relevant features and enhances feature difference through its adaptive weighting, EQU (10) to EQU (12). However, without prior denoising, its performance in noise-sensitive metrics, such as PSNR (34.77 dB), remains suboptimal, as it must operate on potentially noisy inputs.

The complete model (NSST + CDEN) consistently outperforms all other variants across all evaluation metrics, with particularly significant improvements in PSNR (+ 3.36 dB over the baseline), SSIM (+ 0.061 over the baseline), and FSIM (+ 0.056 over the baseline).

Discussion

Comparative analysis with existing methods

The proposed IFM distinguishes itself from existing CNN + PCNN using the synergistic integration of NSST, a CDEN, and a bio-inspired PCNN guided by the Novel Sum Modified Laplacian (NSML). While previous studies, such as48, have verified notable success using CNNs for MFIFM, their utility was constrained to focus classification and binary decision maps, limiting generalizability across broader imaging modalities. Similarly, the CNN-based pixel activity computation for WM generation in49 presented improved saliency encoding yet required robustness in infrared–visible fusion tasks.

In contrast, the proposed model displays versatility across varied imaging domains, including medical modalities such as MRI, CT, SPECT, and PET. The integration of NSST ensures superior frequency localization and directional sensitivity, overcoming the limitations of the TDBIFM, which challenges directional aliasing and frequency bias. Moreover, adopting NSML for HFSB fusion preserves intricate structural data, surpassing conventional statistical measures in PCNN-driven fusion.

Furthermore, unlike50, which integrated Deep CNNs with a Discrete Gravitational Search Algorithm (DGSA) but faced barriers in real-time applicability due to its computational burden, the proposed model retains computational tractability via channel attention mechanisms and lightweight dual-branch training. Including bio-inspired dynamics using PCNN improves edge preservation while mitigating the common problem of contrast degradation obtained in existing research models51,52,53.

Recent innovations in fuzzy-logic-based fusion, including intuitionistic57,59 and Fermatean fuzzy systems61, proposal interpretability, and structural fidelity. However, they frequently face challenges due to overdependence on rule-based heuristic parameters. This model addresses this by embedding uncertainty handling within a data-driven, End-To-End that dynamically learns spatial and frequency-domain fusion cues.

Implications for medical and multimodal image fusion

This model substantially improves the integration of MIF modalities, where preserving texture granularity and diagnostic features is essential. The dual-branch denoising and improvement model ensures signal reconstruction integrity, especially in noisy or compressed attainment environments such as low-dose CT and thermal-visible fusion. The channel-wise attention modulation adapts fusion weights in real-time, supporting clinical applicability across anatomy-specific variations.

Using NSST and PCNN augments visual interpretability and modality consistency, a long-standing challenge in anatomical alignment during fusion. The consistent spatial feature activation across networks enhances the robustness of decision-making in applications such as tumor detection, organ delineation, and pathology mapping.

Methodological limitations

Despite the performance gains, the proposed model has several limitations. First, the reliance on a dual-network model increases the training time and parameter load, which may constrain deployment in low-resource or edge-computing environments. Second, although NSST proposes high directional selectivity, it introduces redundancy that may not be optimal for all fusion scenarios, particularly when real-time constraints dominate.

Additionally, while PCNN-based fusion enhances perceptual quality, its neuron firing threshold and iterative nature introduces sensitivity to initial parameters, which can potentially affect convergence stability. The NSML’s performance depends on accurate high-frequency FE, which may degrade under extreme noise or motion blur conditions not seen in training datasets.

Future work

To overcome these limitations, future research will optimize the model using pruning and quantization methods to reduce model complexity without compromising fusion quality. Adaptive NSST parameter tuning via meta-learning will be investigated to improve cross-domain generalizability. Also, this work plans to explore hybrid models that combine fuzzy-set-based interpretability with DL adaptability, potentially enabling rule-guided yet data-driven fusion control.

Incorporating real-time performance benchmarking and edge-device deployment approaches will also be vital to translating the model into clinical and field use cases. Finally, user-interpretable quality evaluation metrics, particularly those tailored for medical diagnosis, will be integrated to validate fusion efficacy beyond conventional metrics.

Conclusion and future work

Image Fusion remains a challenging domain, particularly for preserving critical details from Source Images in multi-modal medical applications. To address this, the present study proposed a CNN and Shearlet-based fusion model tailored for MMMI. The model incorporates a frequency-level denoising and enhancement network to mitigate quality degradation introduced during NSST decomposition. Enhanced fusion methods were applied to LFSB and HFSB, resulting in improved overall fusion quality.

Extensive experiments were tested using standard benchmark datasets to evaluate the proposed model across multiple performance metrics, including edge information preservation (QAB/F), Image Quality Index (IQI), Spatial Frequency (SF), Mutual Information (MI), and Image Entropy (IE). Comparative analysis demonstrated that the proposed model consistently outperformed existing state-of-the-art methods, producing fused images with superior structural detail and diagnostic relevance. These findings recommend that the proposed method has a robust probability of integration into clinical imaging workflows that require accurate MMIF.

Limitations of the work

One limitation of the current study is the relatively small dataset comprising 180 multimodal image pairs, which, while diverse in modality and structure, may not comprehensively reflect the variability encountered in larger clinical imaging repositories.

Although the proposed CNN + NSST-based fusion model proved superior performance across all evaluation metrics within this dataset, future work will validate the method on larger and more diverse datasets, potentially involving cross-institutional medical imaging archives, to measure scalability and clinical generalizability. The recommended method must be used with real-time applications and other types of MMIF in the future.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

James, A. P. & Dasarathy, B. V. Medical image fusion: A survey of the state of the art. Inf. Fusion 19, 4–19 (2014).

Wang, Z., Ziou, D., Armenakis, C., Li, D. & Li, Q. A comparative analysis of image fusion methods. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens 43(6), 1391–1402 (2005).

Biswas, B. et al. Medical image fusion by combining SVD and shearlet transform. In: 2015 2nd International Conference on Signal Processing and Integrated Networks (SPIN), Noida, India 148–153 (2015).

Ullah, H. et al. Multimodality medical images fusion based on local-features fuzzy sets and novel sum-modified-Laplacian in non-subsampled shearlet transform domain. Biomed. Signal Process. Control 57, 101724 (2020).

Fu, J., Li, W., Du, J. & Xiao, B. Multimodal medical image fusion via laplacian pyramid and convolutional neural network reconstruction with local gradient energy strategy. Comput. Biol. Med. 126, 104048 (2020).

Li, X. & Zhao, J. A novel Multi-Modal Medical Image Fusion algorithm. J. Ambient Intell. Humaniz. Comput. 12, 1995–2002 (2021).

Almasri, M. M. & Alajlan, A. M. Artificial intelligence-based multimodal medical image fusion using hybrid S2 optimal CNN. Electronics 11(14), 2124 (2022).

He, H. A deep research in classic classification network. MS E 740(11), 012152 (2020).

Kong, W., Li, C. & Lei, Y. Multimodal medical image fusion using convolutional neural network and extreme learning machine. Front. Neurorobot. 16(16), 1050981 (2022).